Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a field of fluid mechanics that employs numerical methods and algorithms to analyze and solve problems involving fluid flow, heat transfer, and related physical phenomena. CFD is governed by the Navier-Stokes equations, which represent the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy. These equations are discretized using methods such as the finite difference, finite volume, or finite element methods, converting them into solvable numerical models. The computational domain is divided into a mesh or grid, with the accuracy of simulations relying on the mesh’s quality and resolution. Boundary conditions, such as velocity, pressure, or temperature, are applied to solve the equations iteratively, and the results are visualized and analyzed through post-processing tools. CFD finds extensive applications across industries, including optimizing designs in aerospace, automotive, and energy systems, improving HVAC performance, studying environmental phenomena like pollutant dispersion, and modeling biomedical processes such as blood flow or drug delivery. By providing a cost-effective and versatile approach, CFD has transformed how engineers and scientists tackle complex fluid flow problems.

In Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), validation is the process of assessing the accuracy and reliability of a numerical model by comparing its results with experimental data, analytical solutions, or high-fidelity numerical results. This critical step ensures the model accurately represents real-world physical phenomena and can be trusted for predictive simulations. Validation typically involves comparing simulation outputs, such as velocity profiles, temperature distributions, or pressure fields, with experimental measurements, which are considered the gold standard. For simpler cases, analytical solutions like Poiseuille or Couette flow serve as benchmarks, while high-fidelity numerical results, such as those from Direct Numerical Simulations, are used for more complex scenarios. The validation process includes both quantitative measures, such as error norms and deviation percentages, and qualitative assessments like visual comparisons of flow patterns or temperature fields. Discrepancies revealed during validation help identify limitations in the model, guiding refinements such as improved mesh quality or adjustments to turbulence models. Validation is distinct from verification, which focuses on ensuring the accuracy and consistency of the numerical implementation. Together, validation and verification establish the foundation for credible and reliable CFD simulations in engineering and scientific applications.

In the following, we will present different types of validation results found in different studies:

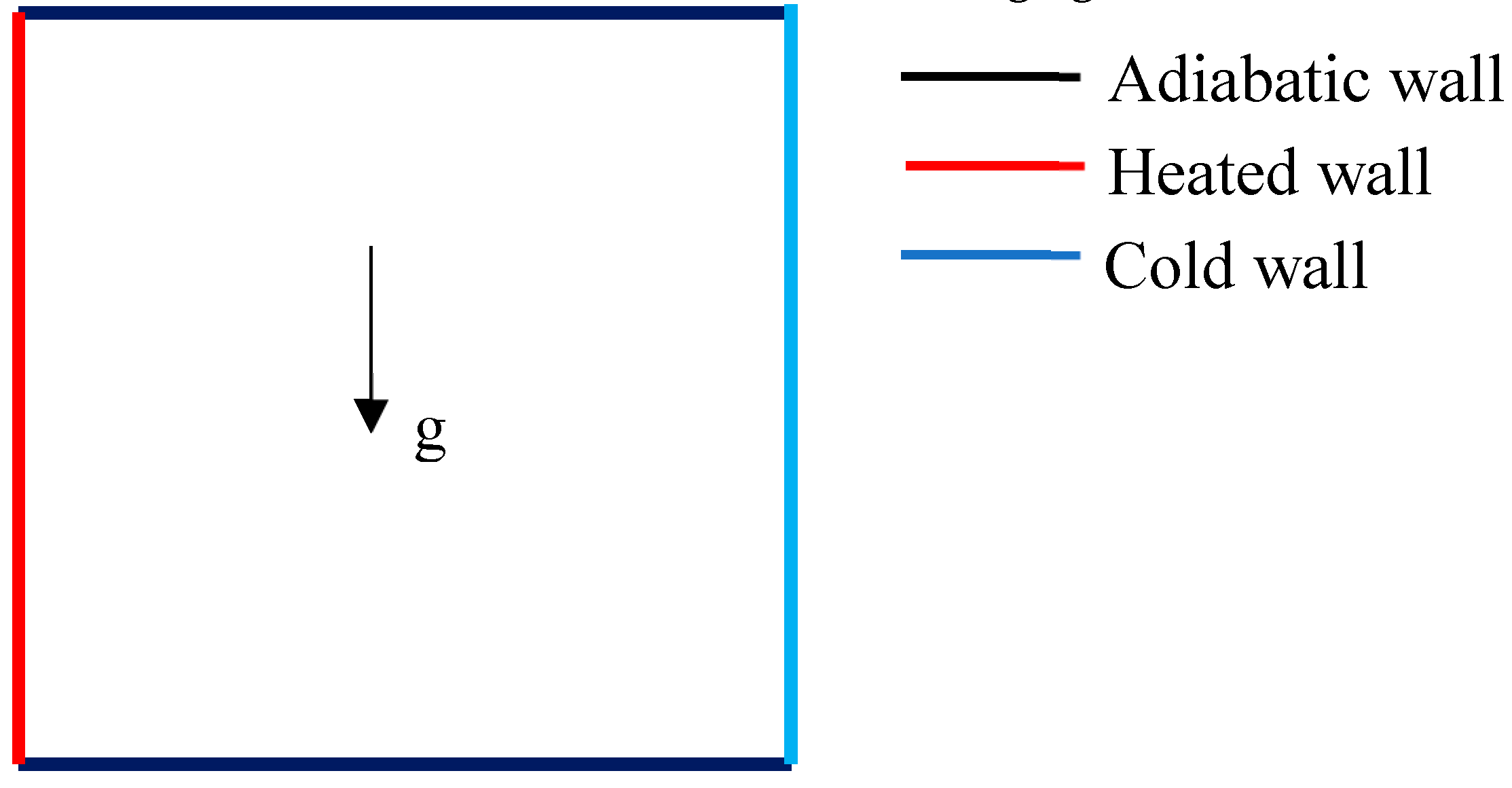

Square Cavity with heated right vertical wall, cold left vertical wall and adiabatic top and bottom walls:

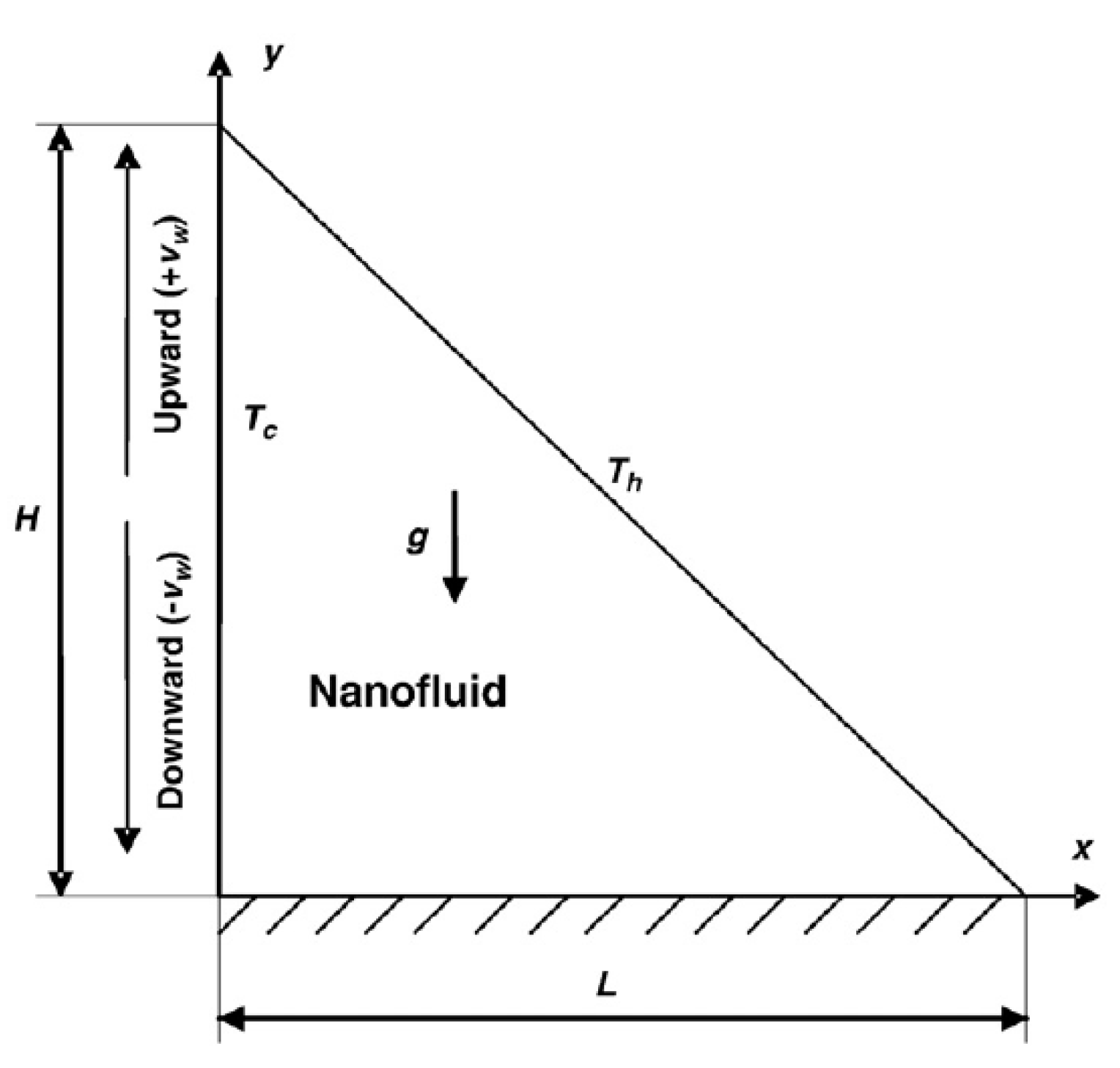

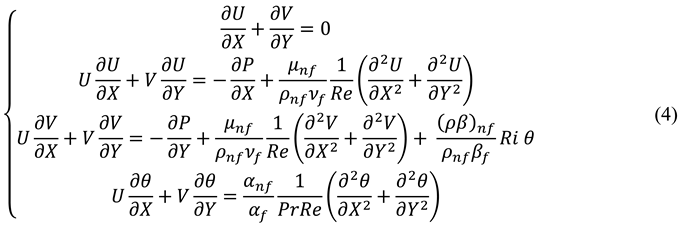

Ilis et al. (2008) considered a cavity with a length L and height H, as shown in

Figure 1. The fluid inside the cavity was assumed to be air (Pr = 0.70). The flow was considered laminar and driven by natural convection, with the effects of radiation deemed negligible.

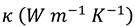

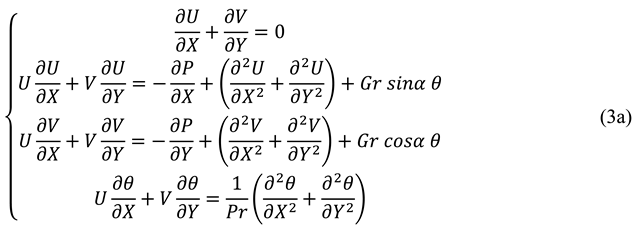

Considering this physical domain, Ilis et al. (2008) conducted a numerical study using the Finite Difference Method. Mathematical model for this study is presented below.

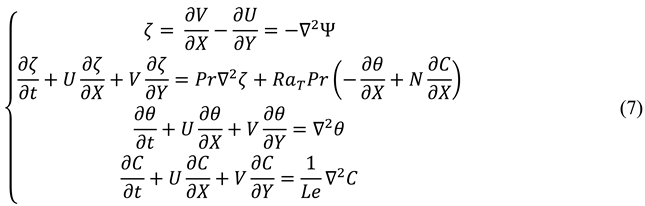

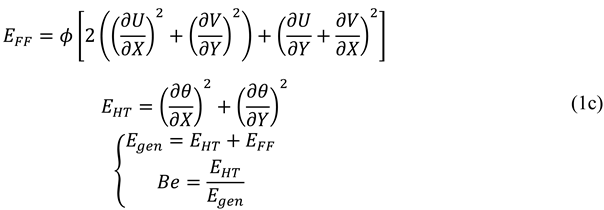

Non-dimensional Governing Equations:

Non-dimensional parameters:

Also, Entropy generation due to fluid friction, entropy generation due to heat transfer, total entropy generation and Bejan number are defined as follows:

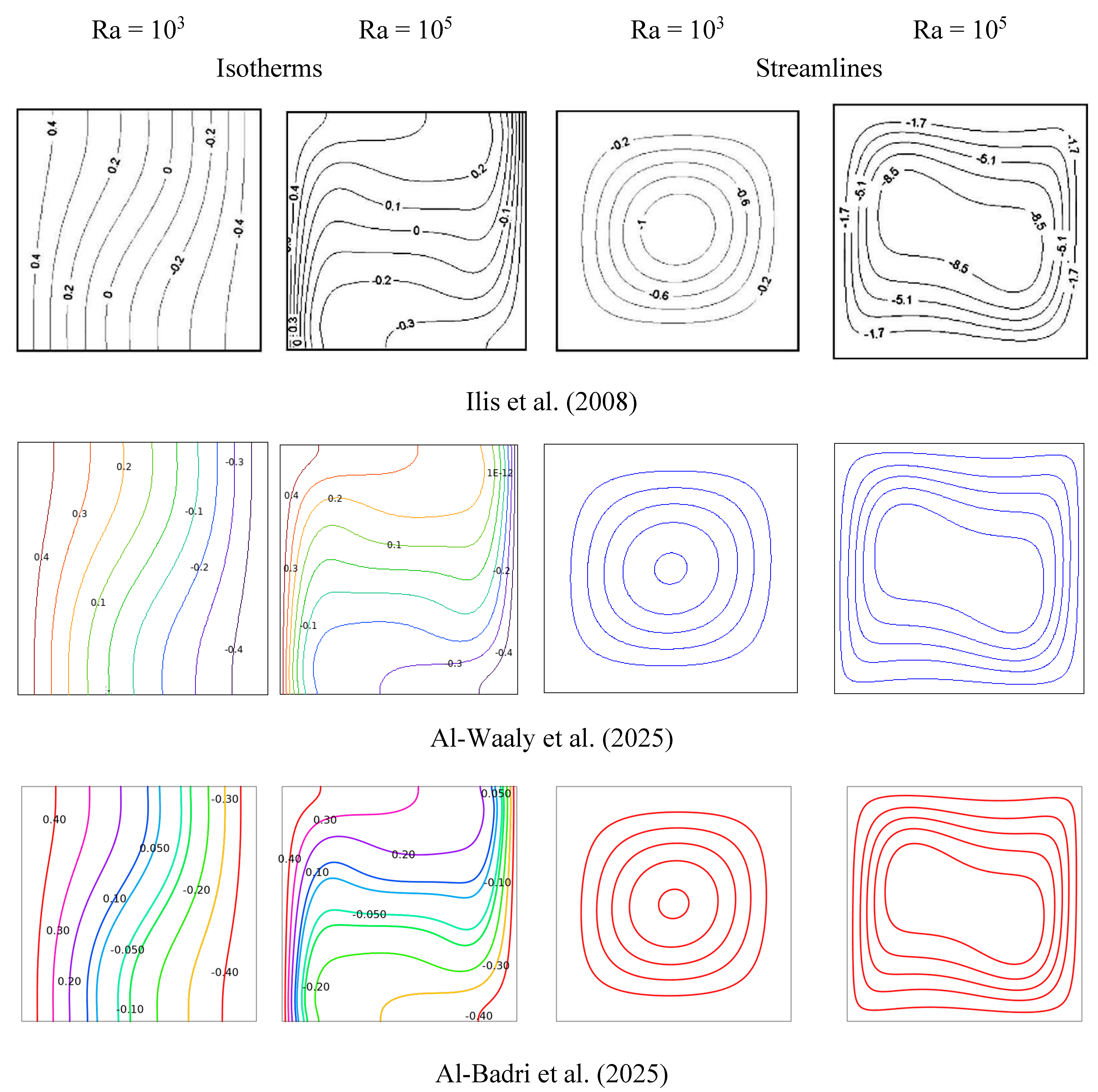

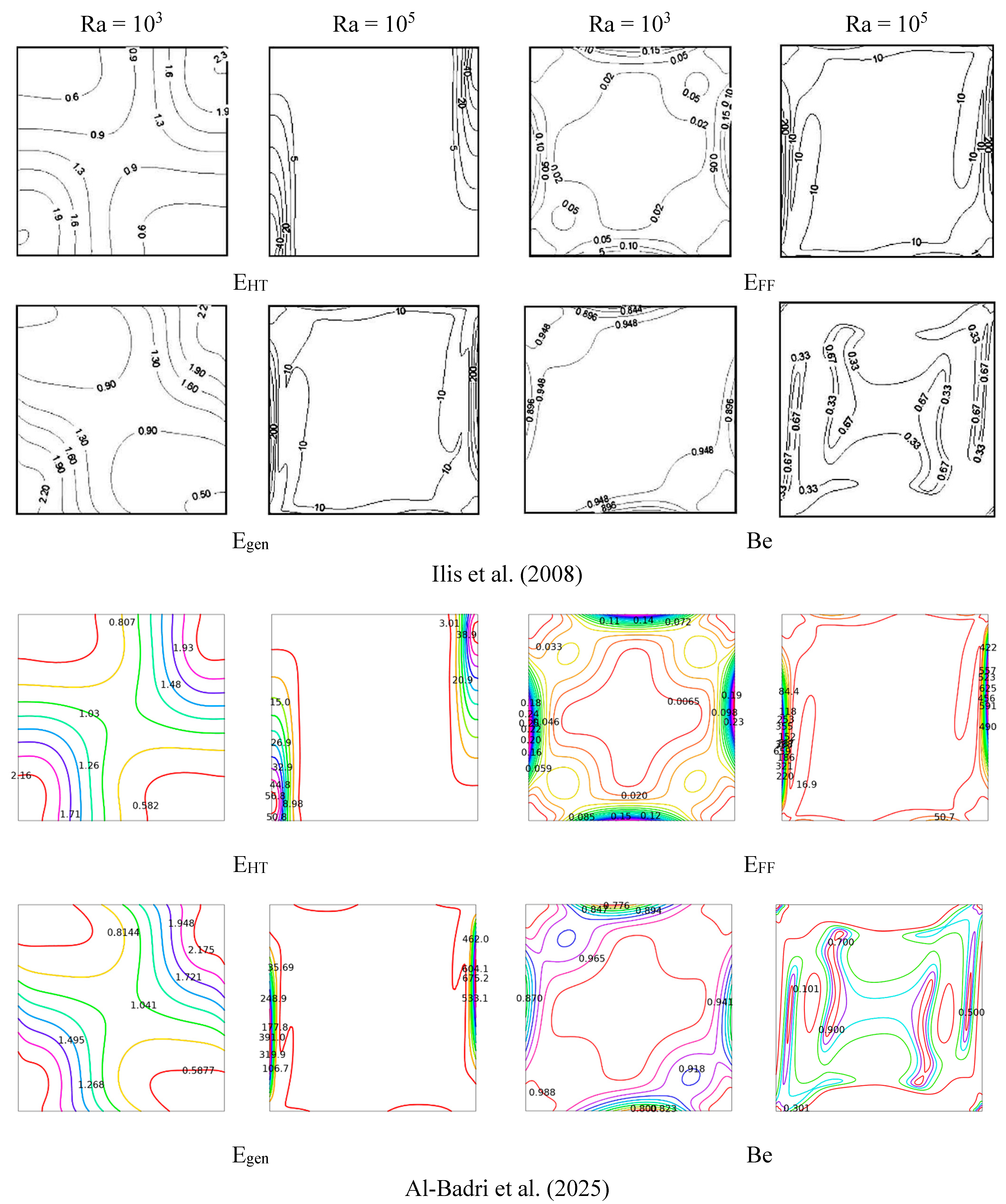

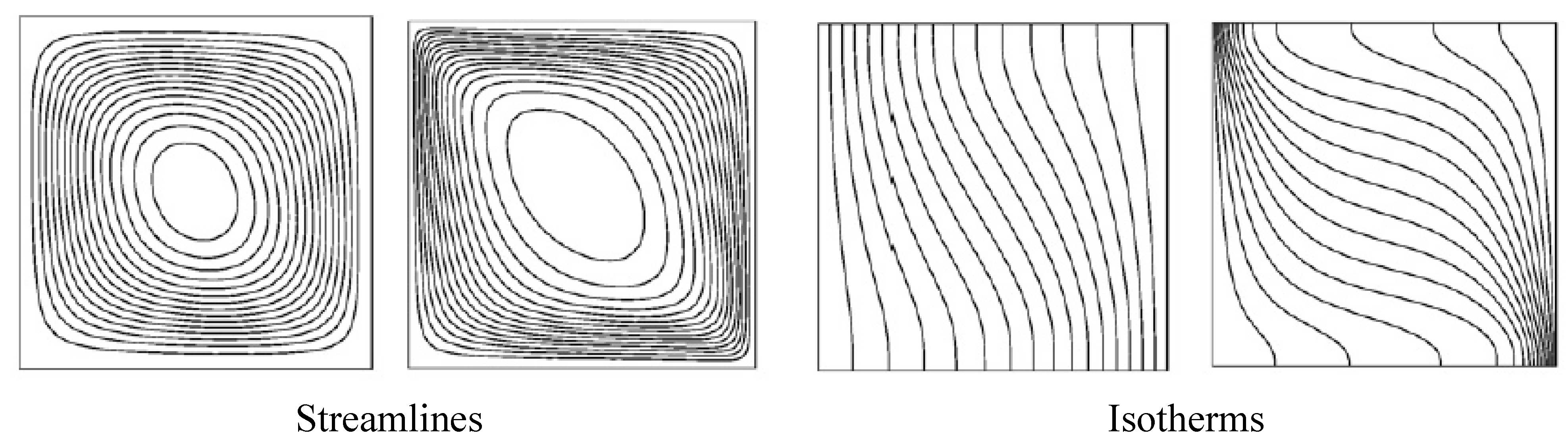

The results were presented in terms of isotherm and streamline profiles for different Rayleigh numbers (Ra). Similar results were later generated by other researchers, such as Al-Waaly et al. (2025), Al-Badri et al. (2025). Details are presented in

Figure 2. Moreover, results of entropy generation due to fluid friction, entropy generation due to heat transfer, total entropy generation and Bejan number are presented in

Figure 3 for different Ra. Similar results were later generated by other researchers, such as Al-Badri et al. (2025).

Square cavity with cold vertical walls, top adiabatic wall and discrete bottom heating:

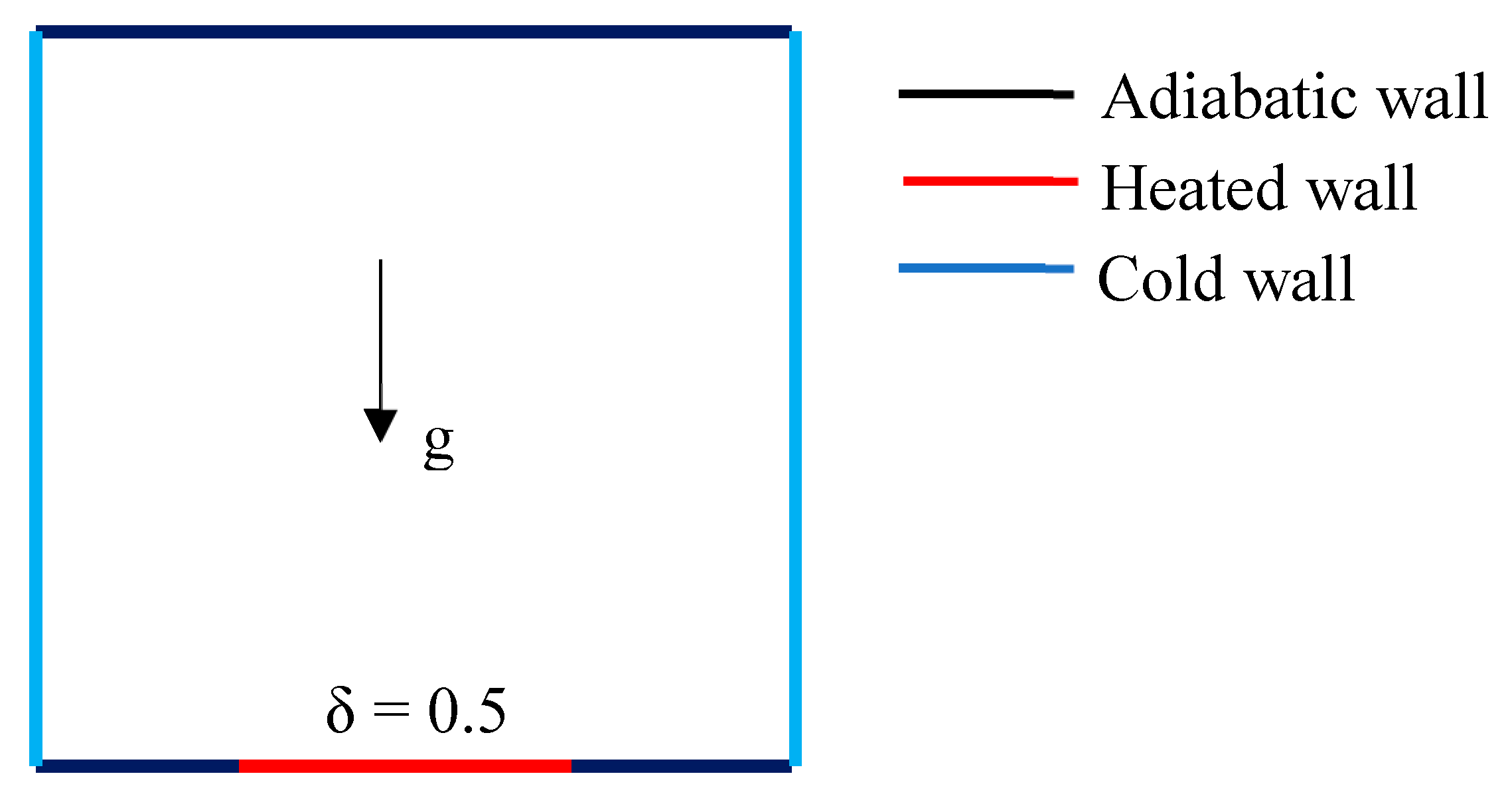

Corvaro & Paroncini (2008) considered an experimental and numerical study on square cavity filled with air with a height H, as shown in

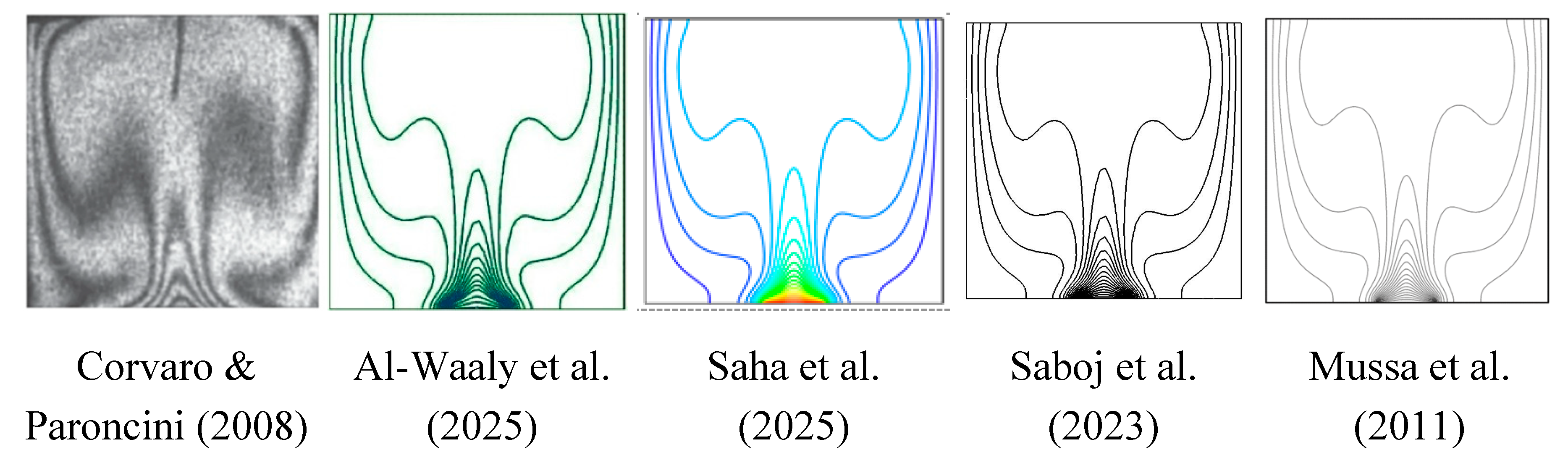

Figure 4. A heated strip is placed at the bottom wall. The flow was considered laminar and driven by natural convection. Considering this physical domain, they conducted a numerical study using the Finite Volume Code Fluent 6.2.16. The following result were presented in terms of isotherm profiles (

Figure 5) for Rayleigh numbers (Ra) = 2.02

× 10

5. Similar results were later generated by other researchers, such as Al-Waaly et al. (2025), Saha et al. (2025).

Corvaro & Paroncini (2008) defined local and average Nusselt numbers in the following ways (Eqs. (1 d, e)) and then they presented the average Nusselt number results and later Saha et al. (2010) used these results for comparison as presented in

Table 1.

Square Cavity with heated right vertical wall, cold left vertical wall and adiabatic top and bottom walls:

de Vahl Davis (1983) presented a benchmark solution under natural convection, laminar flow in a square cavity filled with air (Pr = 0.71) as shown in

Figure 1. They presented average Nusselt number (Nu

avg) for different Ra ranges from 10

4 to 10

6 and presented in

Table 2. Similar results generated by other researchers such as Fusegi et al. (1991), Ho and Lin (1997), Wan et al. (2001), Choi (2005), Kahveci (2007), Lo et al. (2007), Tiwari and Das (2007), Oliveski et al. (2009), Al-Waaly et al. (2025).

Regular octagonal cavity with vertical heated walls, horizontal cold walls, inclined adiabatic walls:

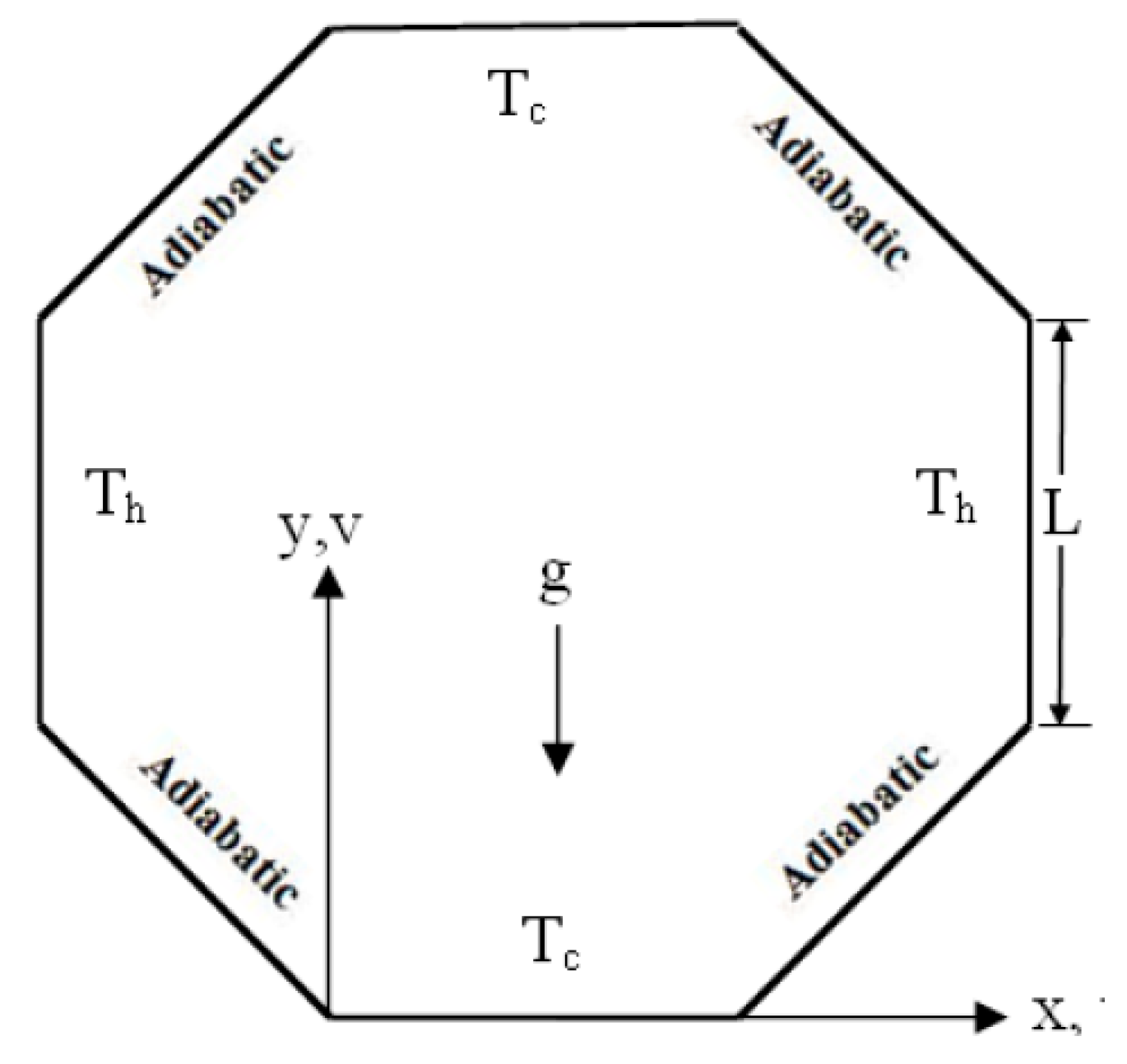

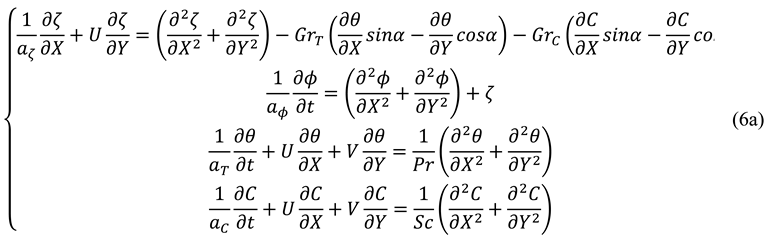

Saha et al. (2010) investigated a regular octagonal cavity with length L, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The fluid inside the cavity was assumed to be air (Pr = 0.71). The flow was considered laminar and driven by natural convection, with viscous dissipation effects considered negligible. The mathematical model is presented in Eqs. 1(a, b). The results were depicted in terms of isotherm and streamline profiles for different Rayleigh numbers (Ra). Similar results were later produced by other researchers, such as Saha et al. (2024), as shown in

Figure 7.

Regular octagonal cavity with vertical heated walls, horizontal cold walls, inclined adiabatic walls with circular cylinder inserts:

Saboj et al. (2023) conducted a numerical study on a regular octagonal cavity of length L with inner cold cylinder inserts filled with air, water, and nanofluids, as shown in

Figure 8. The mathematical model equations are provided in Eq. (1a). They also performed simulations for fluids such as air and presented their results in terms of streamlines and isotherms. These results were later validated by Saha et al. (2025) and are illustrated in

Figure 9.

Trapezoidal cavity with bottom heating, inclined cold sidewalls, adiabatic top wall:

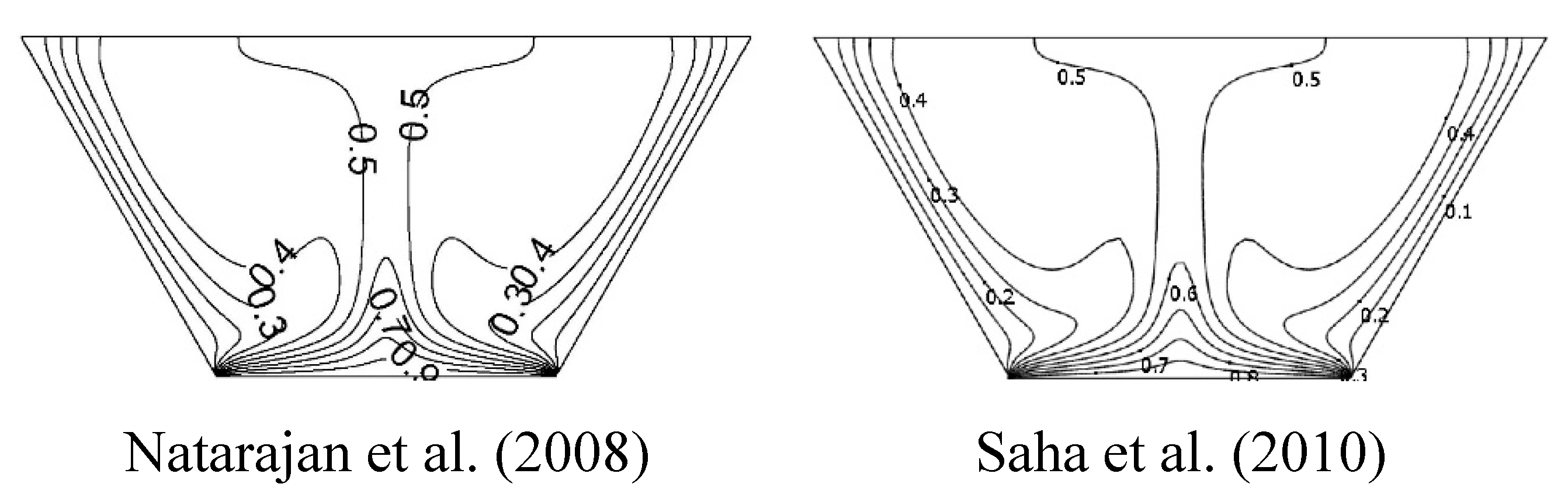

Natarajan et al. (2008) numerically studied natural convection flow inside a trapezoidal enclosure with a heated bottom wall (

Figure 10) and Prandtl number (Pr) values ranging from 0.07 to 100. The mathematical model used in this study is presented in Eq. 1a. They provided isotherm profiles for different Pr values, which were later validated by Saha et al. (2010) for the uniform heating case with Pr = 0.7 and Ra = 10

5, as shown in

Figure 11.

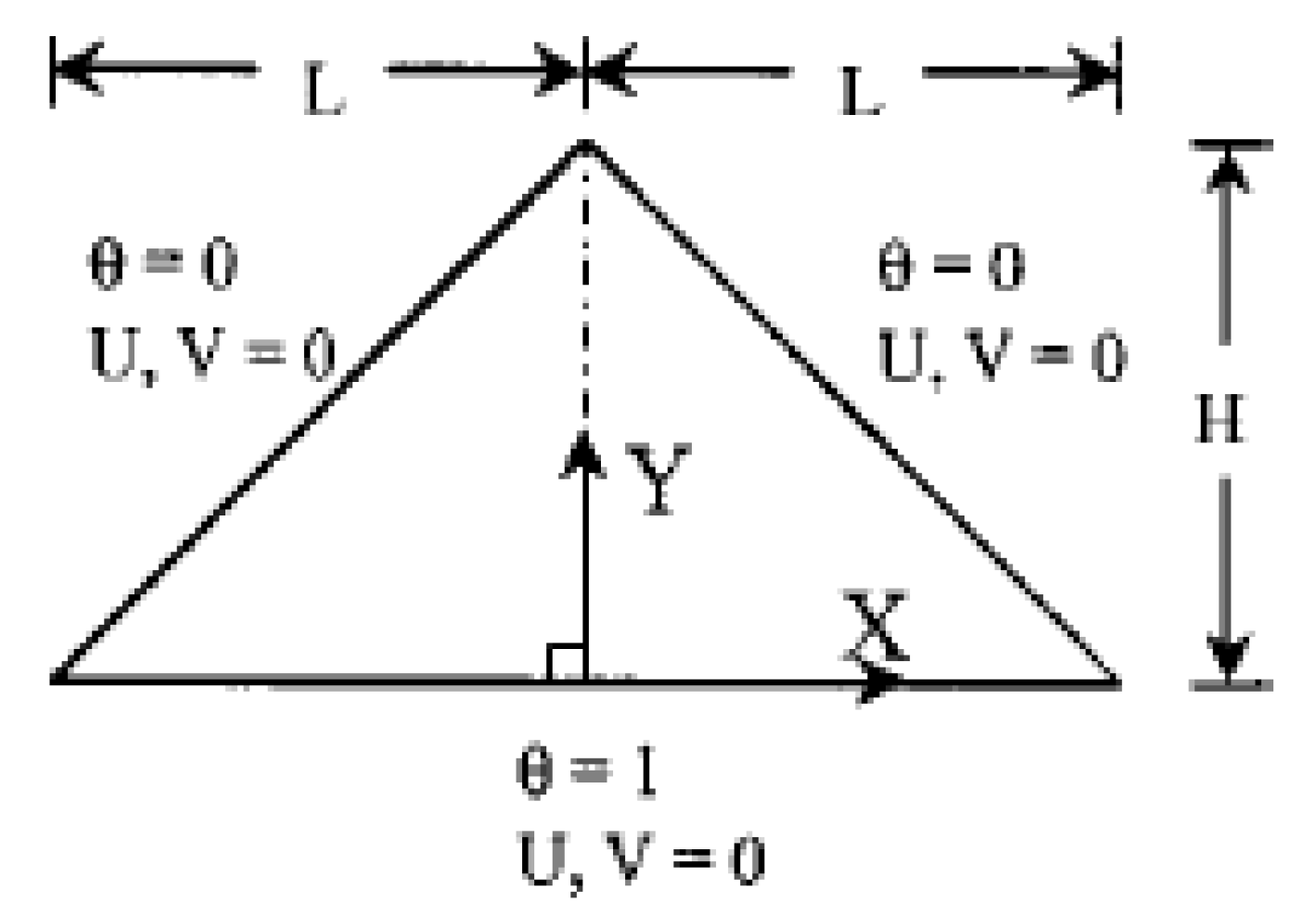

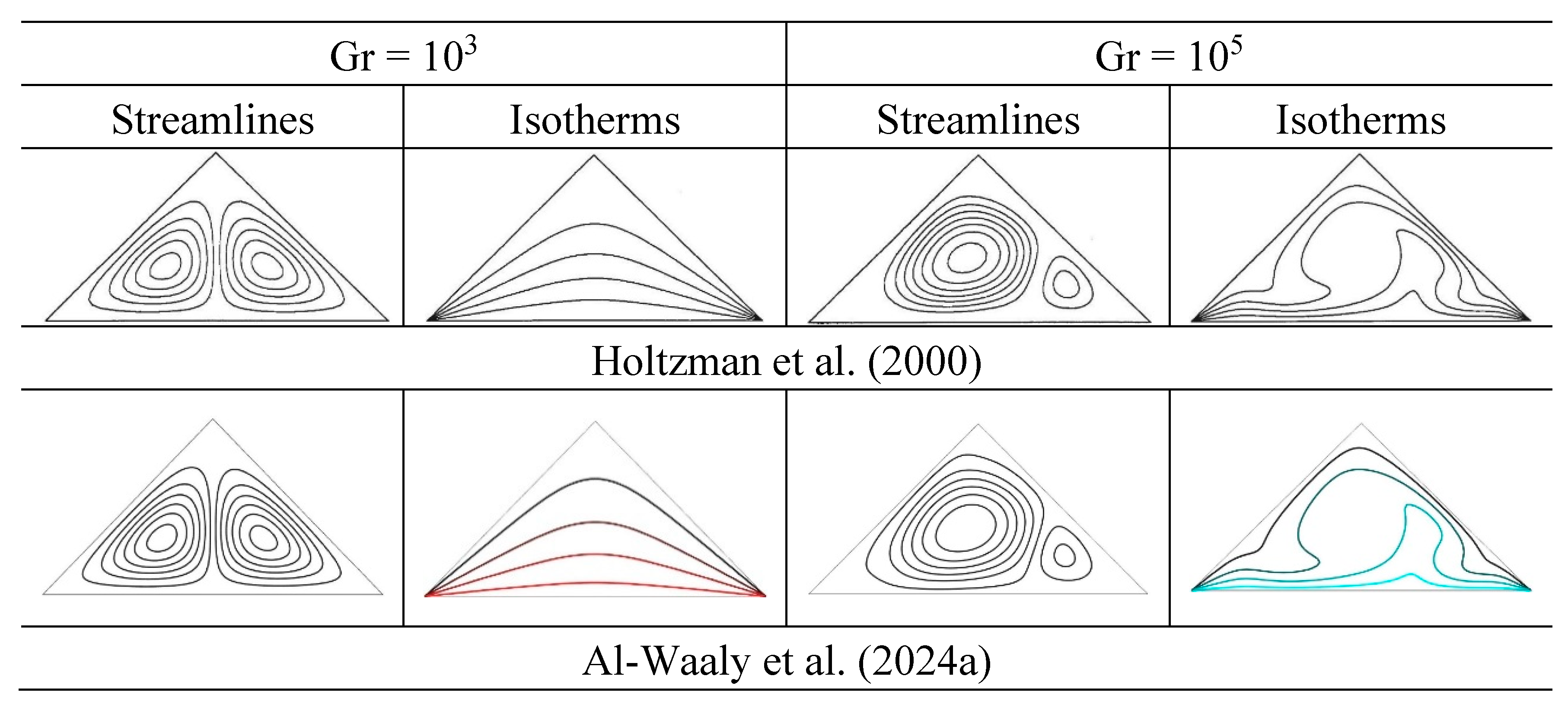

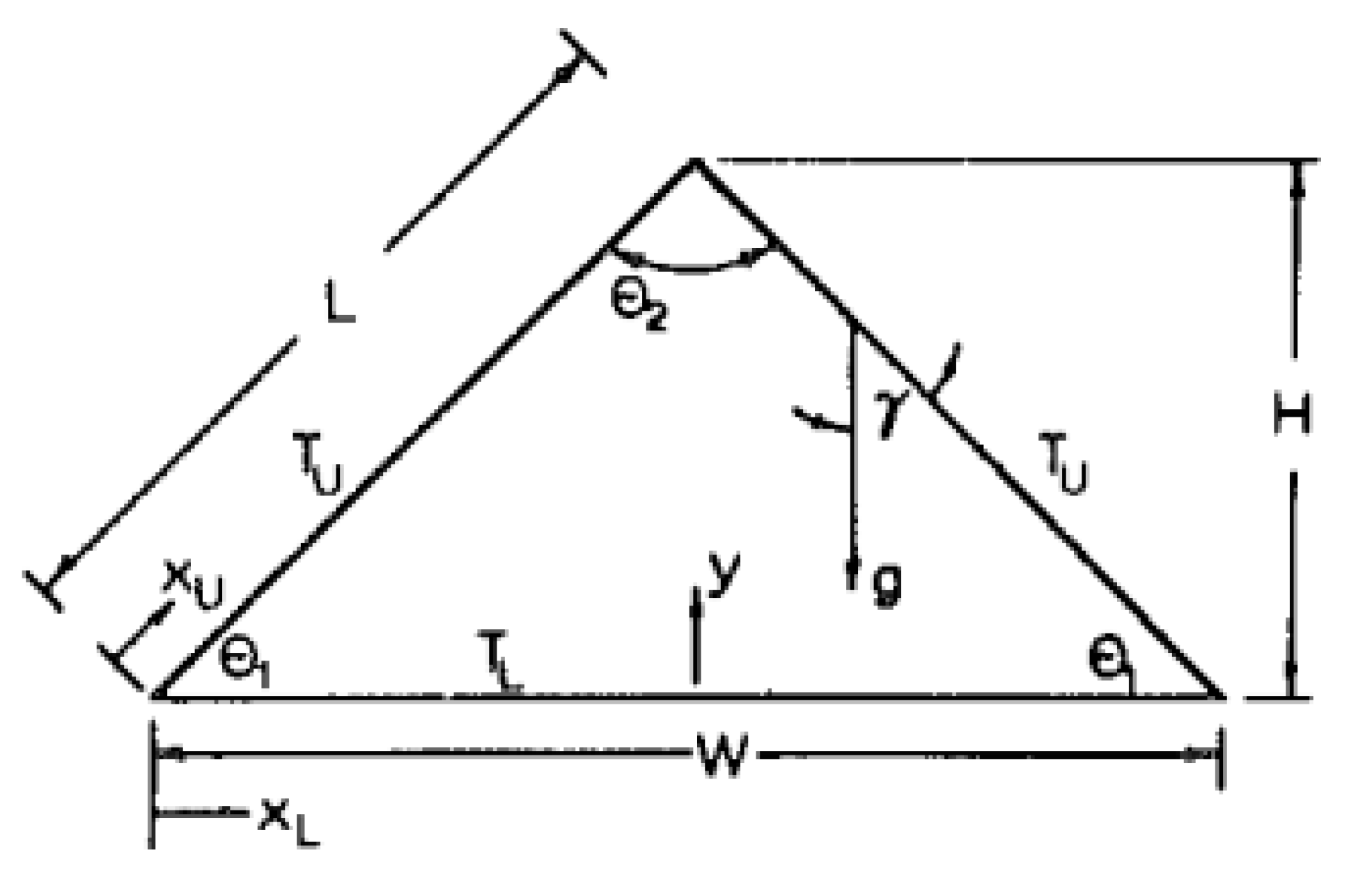

Isosceles Triangular cavity with bottom heating and inclined cold walls:

Holtzman et al. (2000) conducted both numerical and experimental research on an air-filled isosceles triangular cavity with a heated bottom wall and cooled side walls. The physical domain is depicted in

Figure 12. They presented their results in terms of streamlines and isotherms for various Grashof numbers, as shown in

Figure 13. Later, these results were revisited by other researchers, such as Al-Waaly et al. (2024a). Furthermore, the results of Nu

avg were also presented for different Grashof numbers, with a subsequent comparison made by Al-Waaly et al. (2024b) as shown in

Table 3a. Another results of Nu

avg is also presented in

Table 3b.

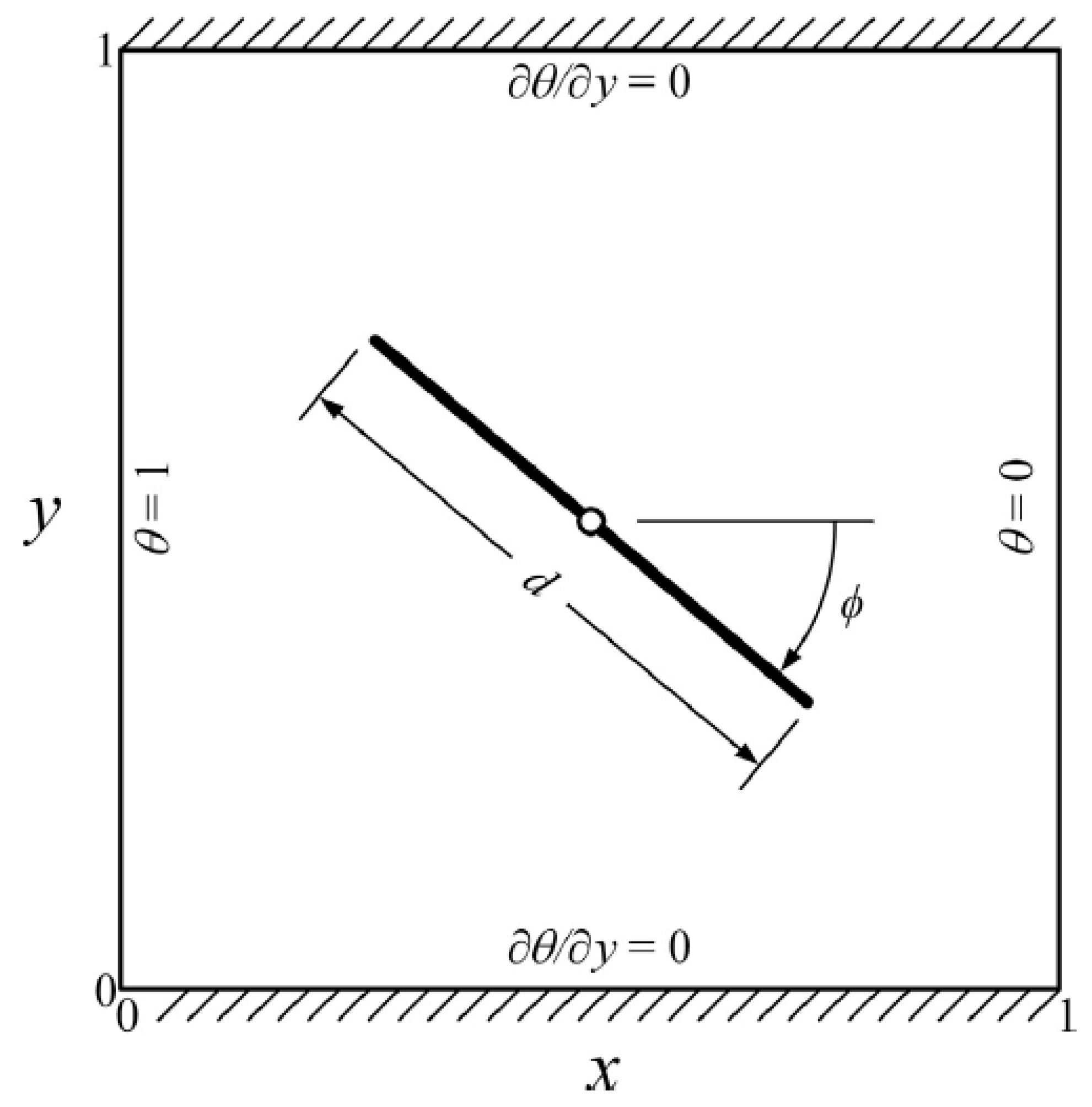

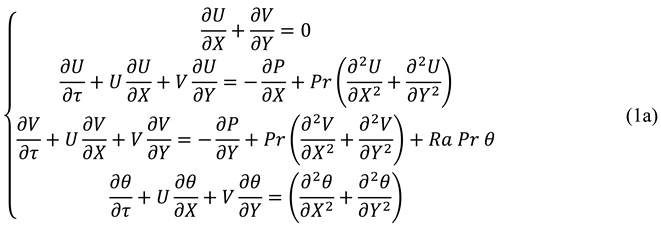

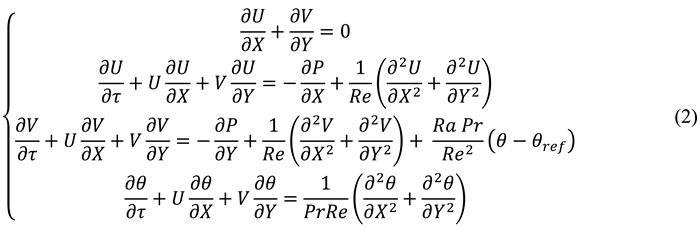

Square cavity with rotating blade inside:

Lee et al. (2019) investigated mixed convection in an air-filled square cavity with a rotating flat plate placed of the centerline position. They used the following governing equations (Eqs. 2). And the physical model is presented in

Figure 14.

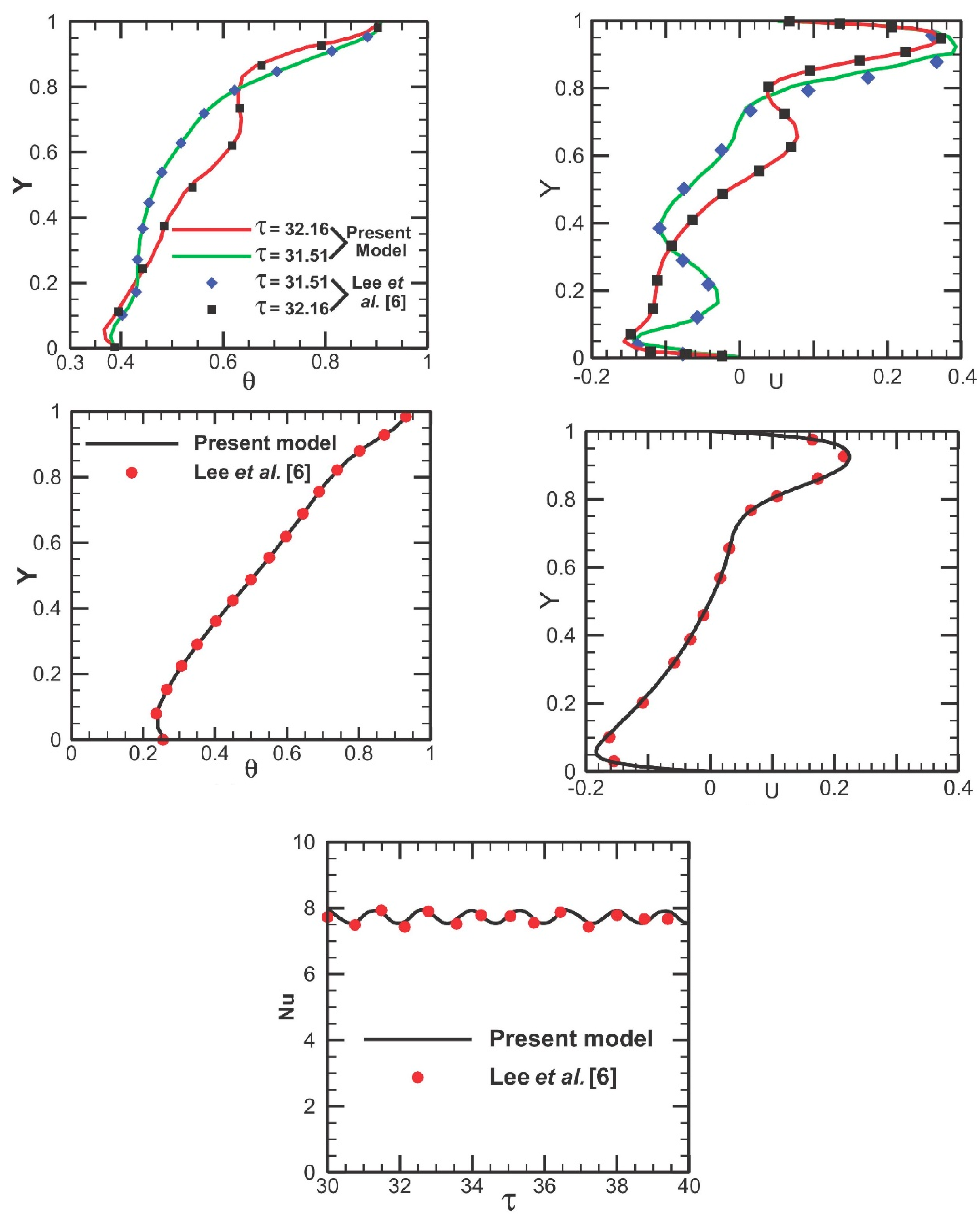

Lee et al. (2019) presented different types of results and these results were regenerated by Ikram et al. (2021) later. Details of these results were presented in

Figure 15.

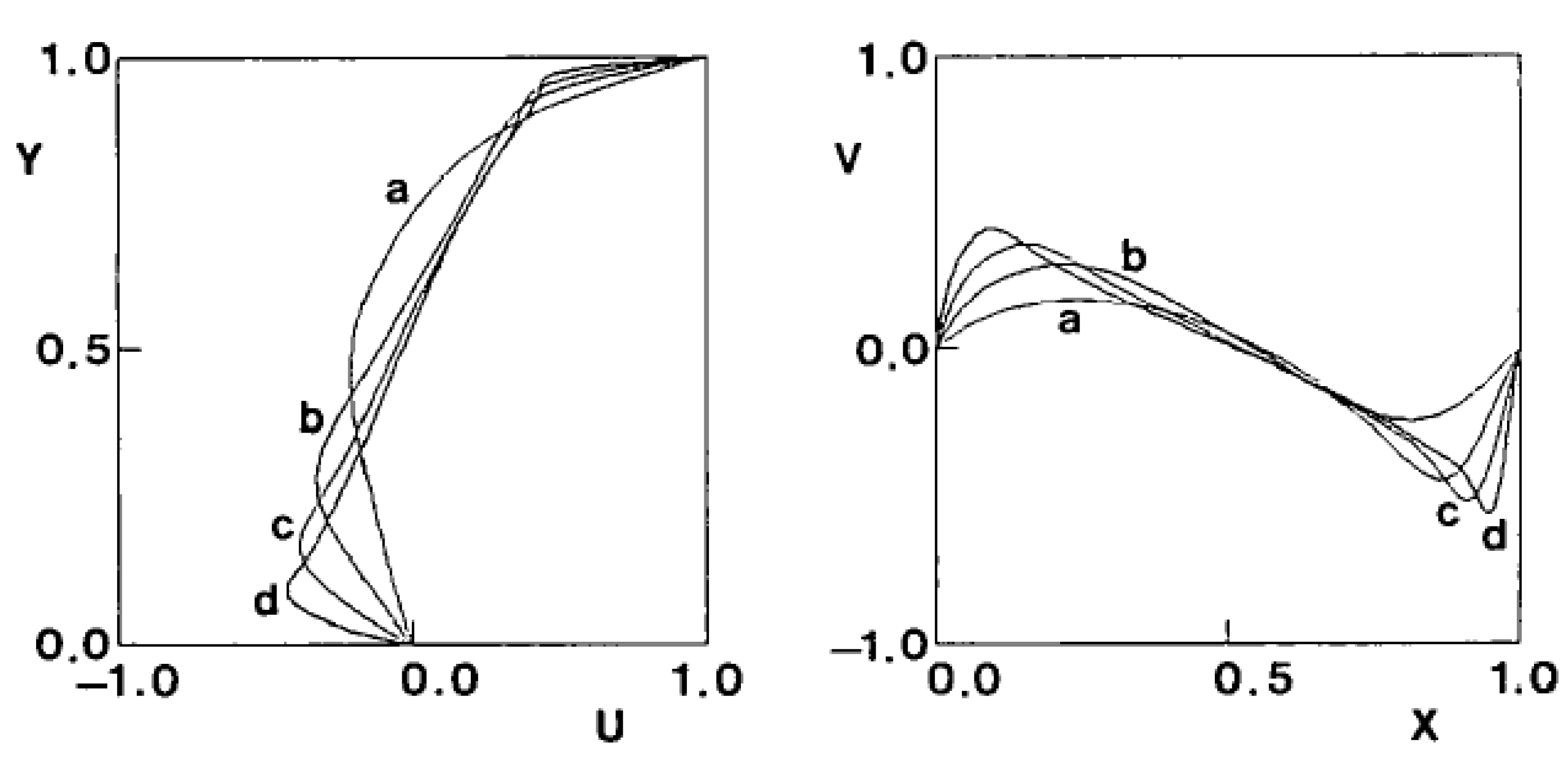

Square cavity with moving heated top wall, vertical adiabatic walls and cold bottom wall:

Iwatsu et al. (1993) studied mixed convection flow and heat transfer behavior in a square cavity with moving top wall. Their chosen physical domain is presented in

Figure 16 and governing equations are presented in Eq. (2).

They presented some results in terms of horizontal and vertical velocity for different Reynolds numbers and these are presented below (

Figure 17):

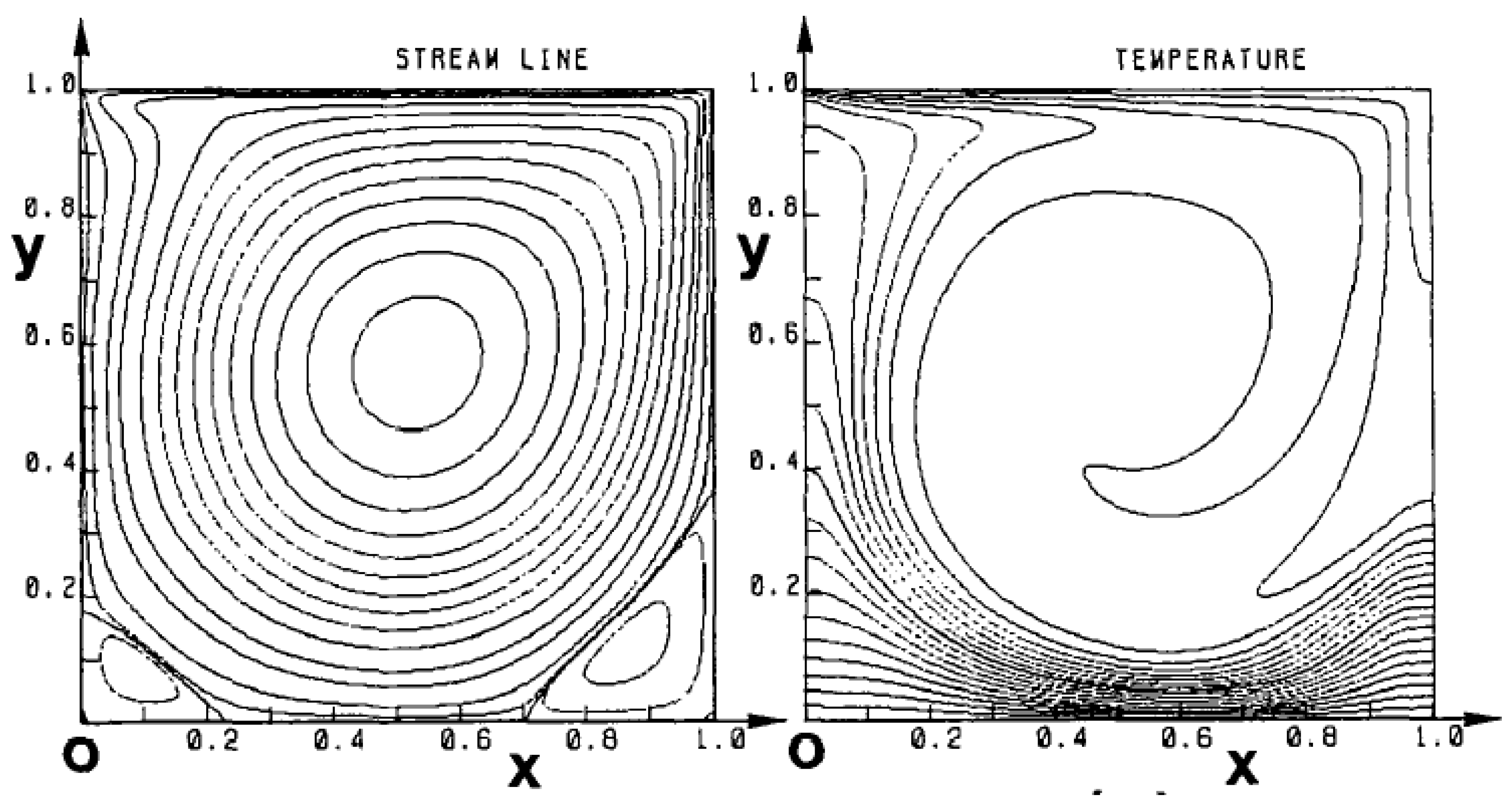

They also presented streamlines and isotherms plots for Re = 10

3, Gr = 10

2 as shown in

Figure 18. Finally, they presented the variation of average Nusselt number for different Re and Gr as shown in

Table 4.

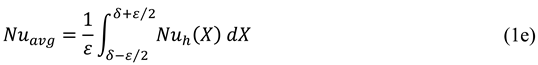

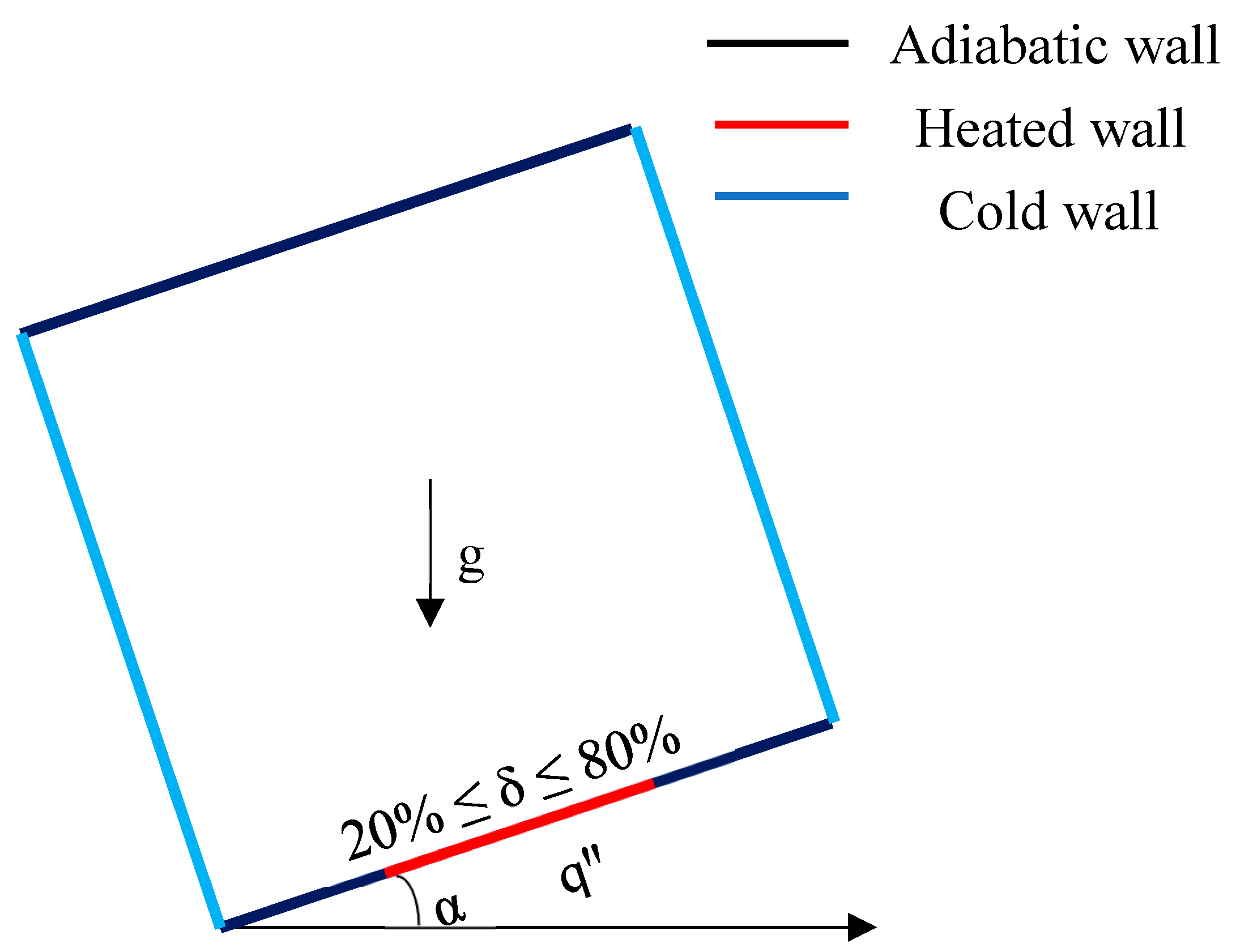

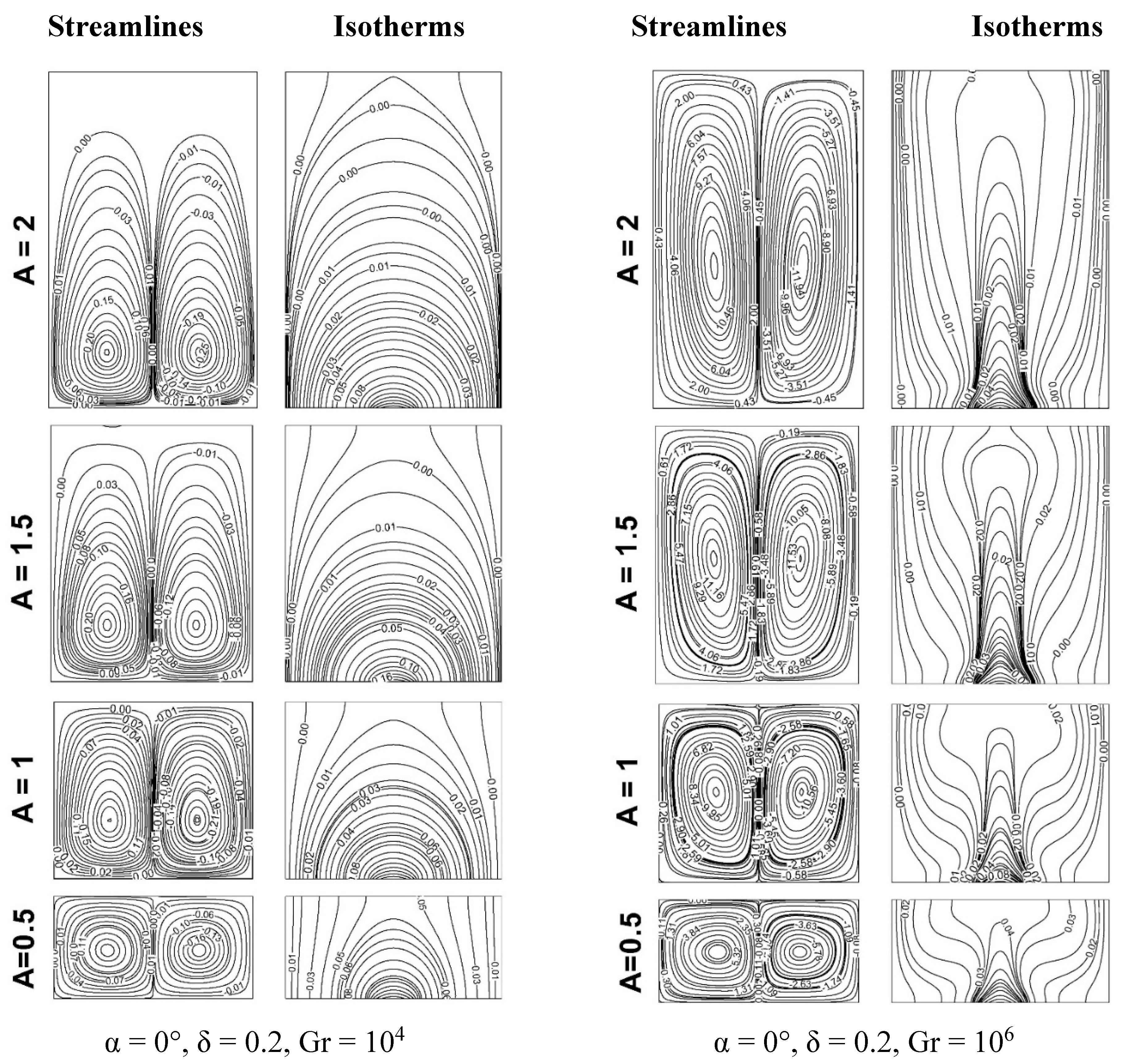

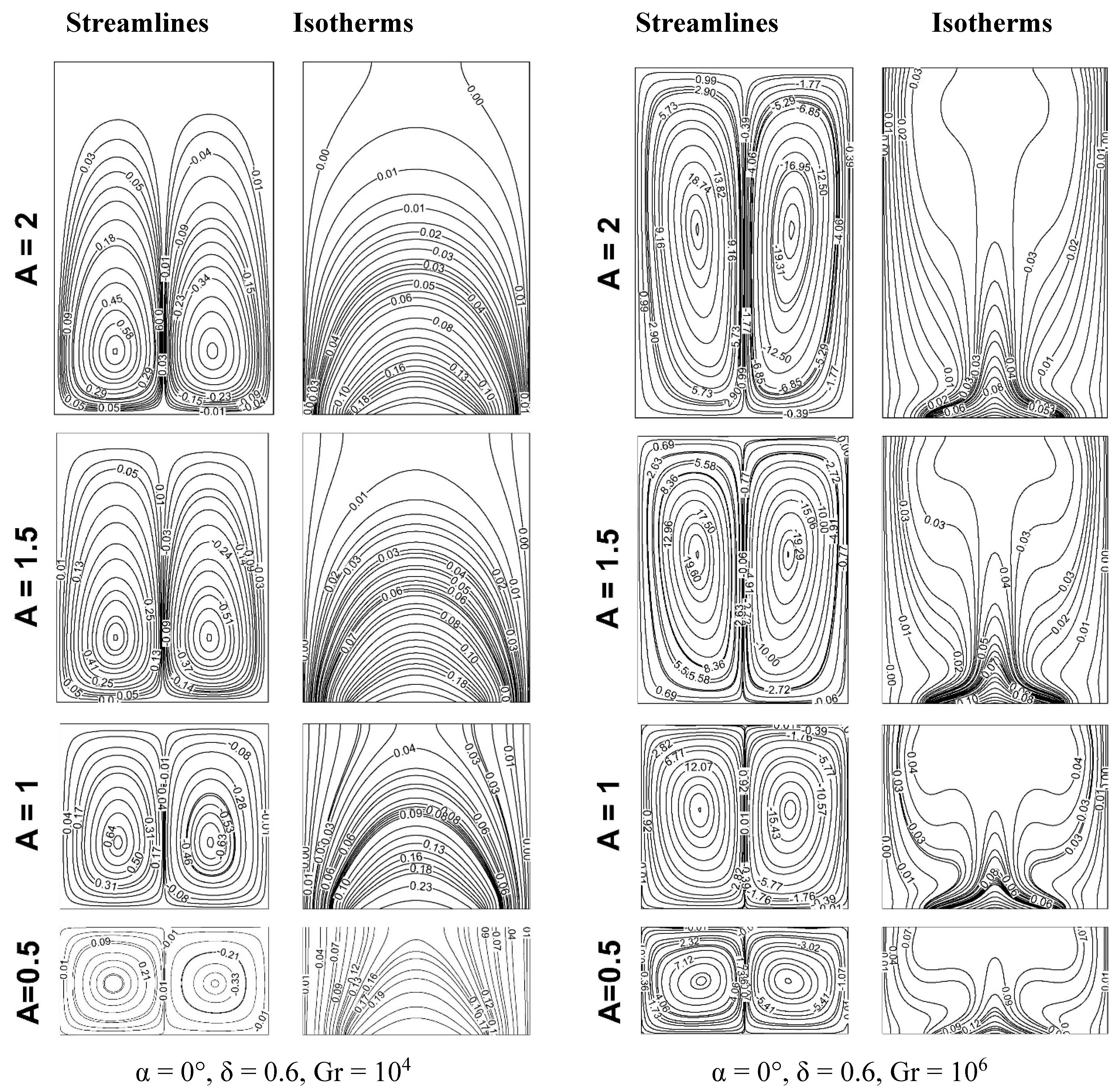

Square cavity with discrete bottom heating, vertical cold walls, adiabatic top wall:

Sharif and Mohammad (2005) investigated natural convection flow in cavities with different aspect ratios with constant flux heating at the bottom wall and isothermal cooling from the sidewalls and adiabatic top wall. The length of the heat source is varied from 20 to 80% of the total length of the bottom wall and the non-heated parts of the bottom wall are considered adiabatic. Physical domain is presented in

Figure 19 and governing equations are presented in Eqs. 3.

Figure 19.

Physical domain with discrete heating from below.

Figure 19.

Physical domain with discrete heating from below.

Figure 20.

(a): Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different aspect ratios for α = 0°, δ = 0.2, Gr = 104, 106.

Figure 20.

(a): Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different aspect ratios for α = 0°, δ = 0.2, Gr = 104, 106.

Figure 20.

(b): Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different aspect ratios for α = 0°, δ = 0.6, Gr = 104, 106

Figure 20.

(b): Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different aspect ratios for α = 0°, δ = 0.6, Gr = 104, 106

where, is the inclination angle.

They presented following results for different heat source sizes and Grashof numbers with variation of aspect ratios for inclination angle = 0°.

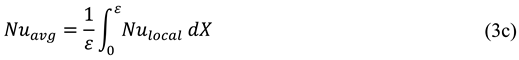

Sharif and Mohammad (2005) defined local and average Nusselt numbers in the following ways:

Average Nusselt number results of Sharif and Mohammad (2005) and Saha et al. (2007) are presented below:

Table 5.

variation of average Nusselt number with different Gr.

Table 5.

variation of average Nusselt number with different Gr.

| Average Nusselt number |

| Gr |

Sharif and Mohammad (2005) |

Saha et al. (2007) |

| 103

|

5.927 |

5.939 |

| 104

|

5.946 |

5.954 |

| 105

|

7.124 |

7.117 |

| 106

|

11.342 |

11.226 |

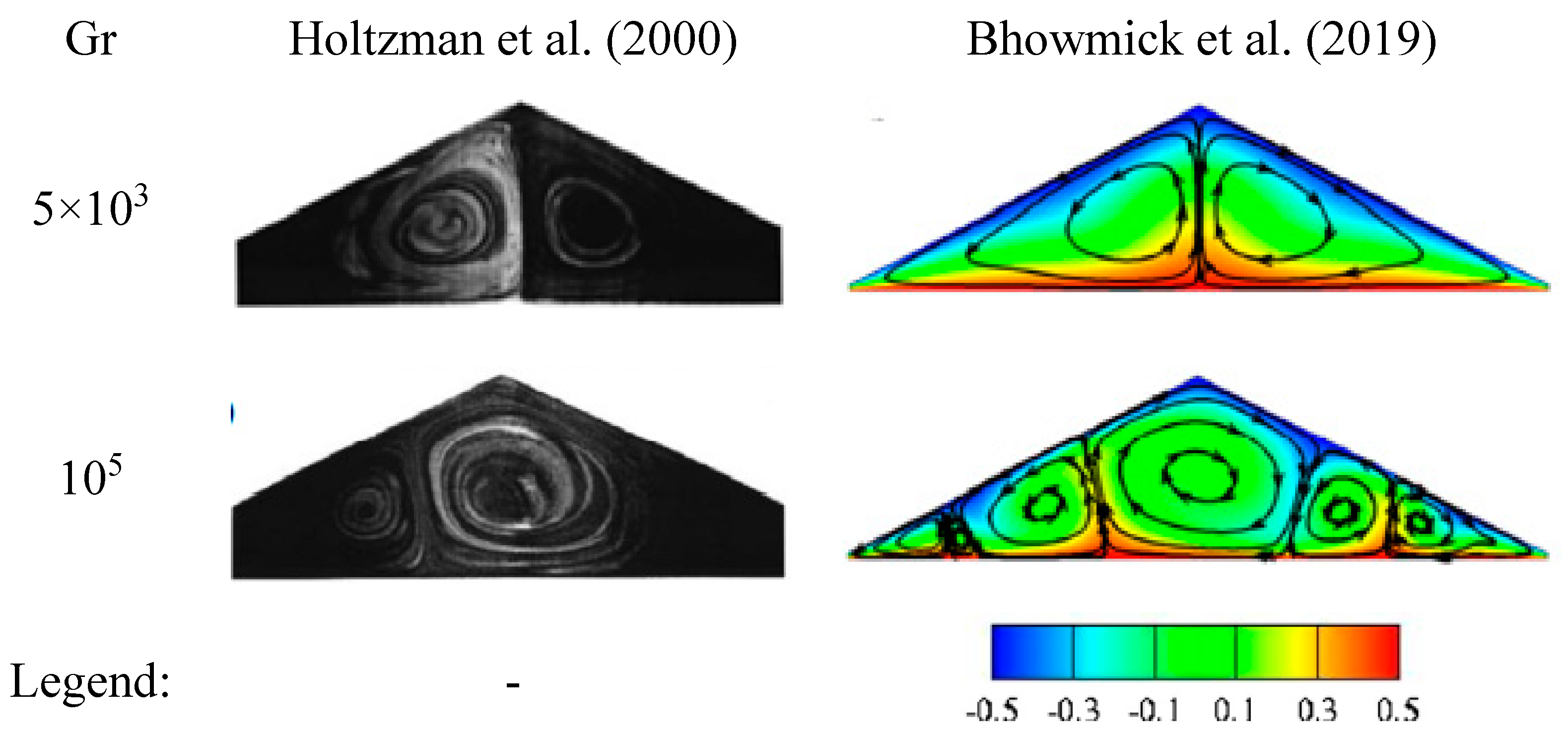

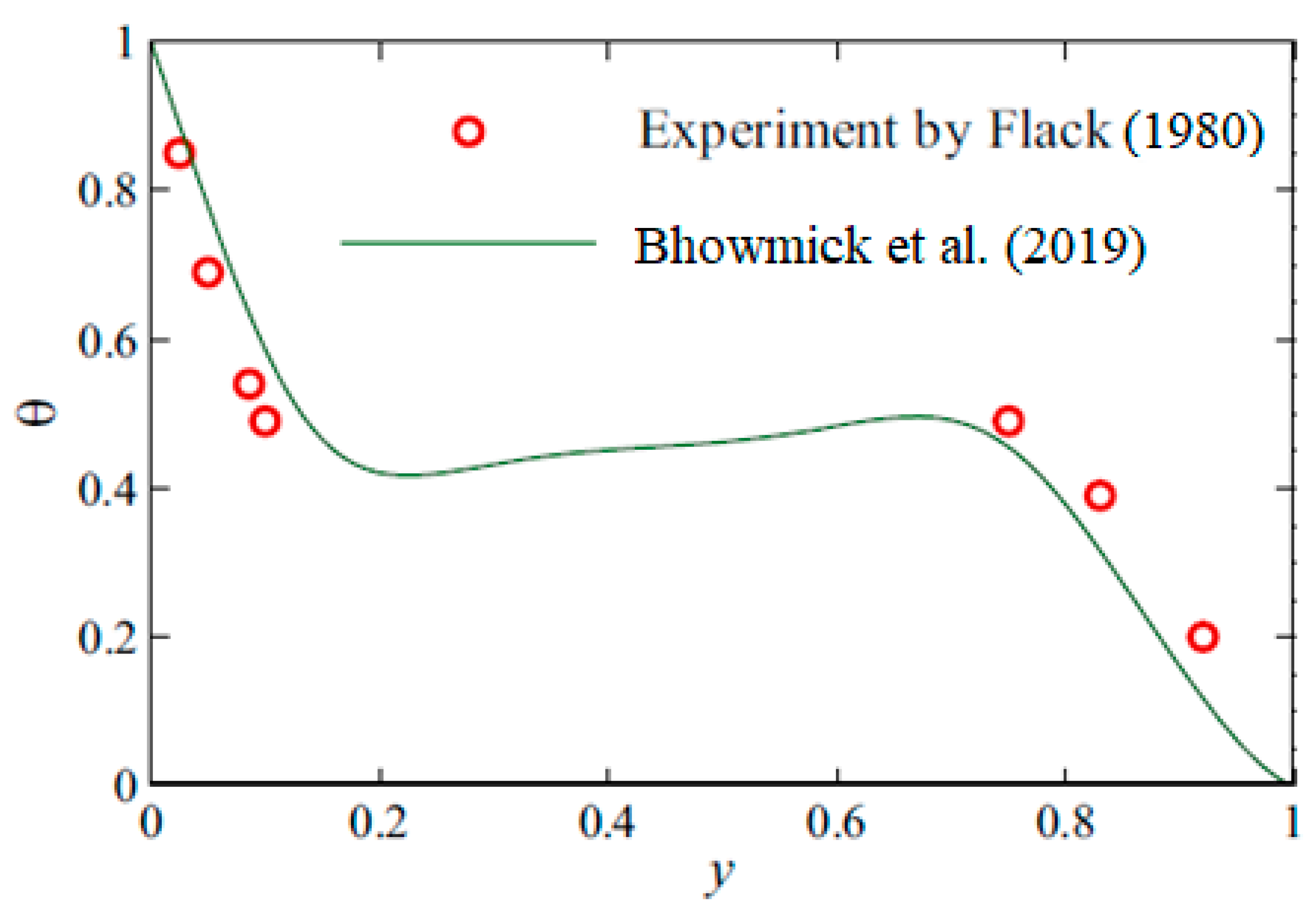

Flack (1980) investigated experimentally the natural convection heat transfer in triangular cavities heated or cooled from below as presented in

Figure 21.

Later, Bhowmick et al. (2019) conducted a validation study against the results of Flack (1980) and results are presented in

Figure 22.

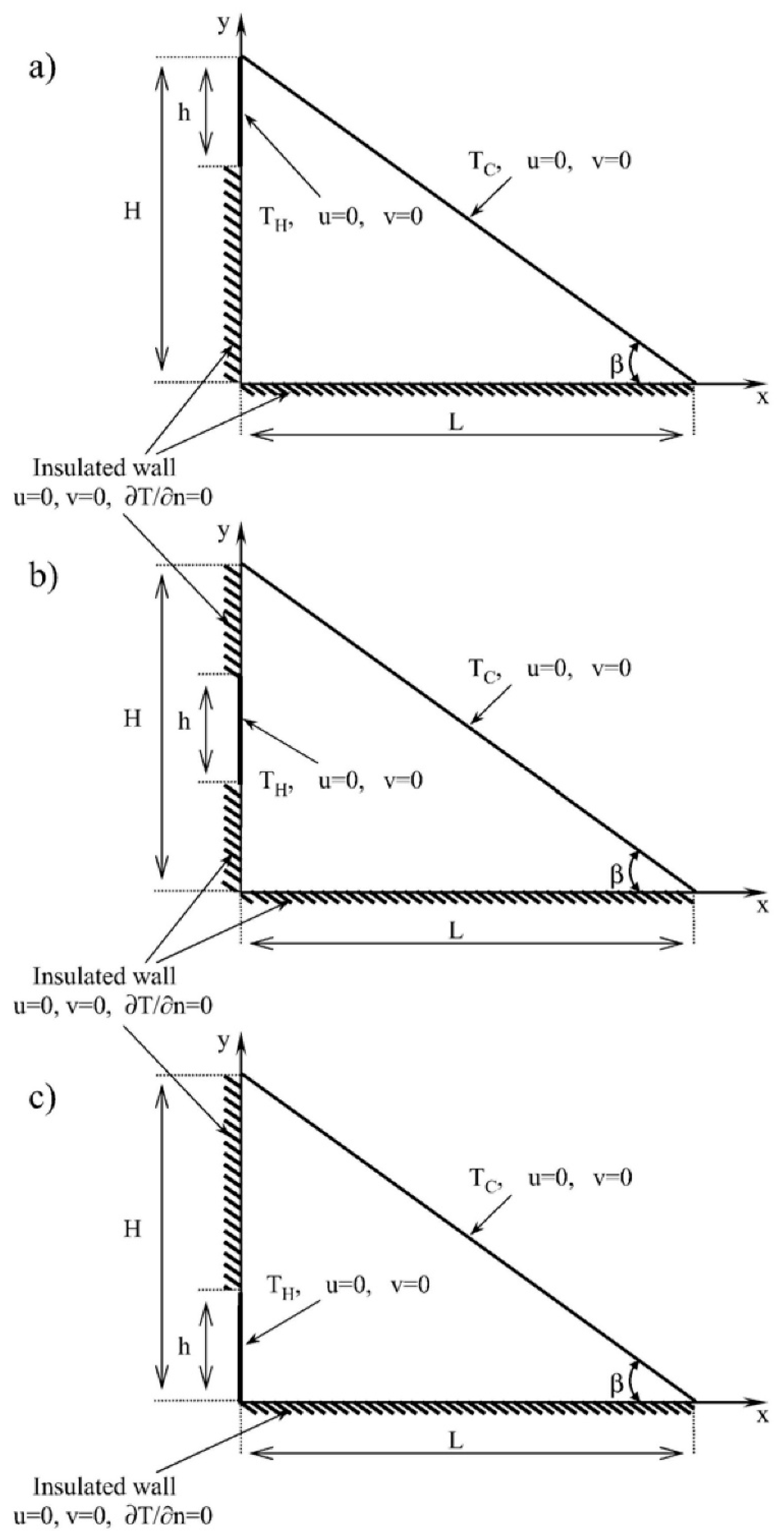

Right-angled triangular cavity:

Varol et al. (2006) conducted a numerical study considering a air-filled right triangular cavity with different heating positions as shown in

Figure 23. They assumed that flow was laminar, steady, incompressible, and Newtonian fluid with the Boussinesq approximation. Radiation effect was negligible and gravity acts in downward vertical direction.

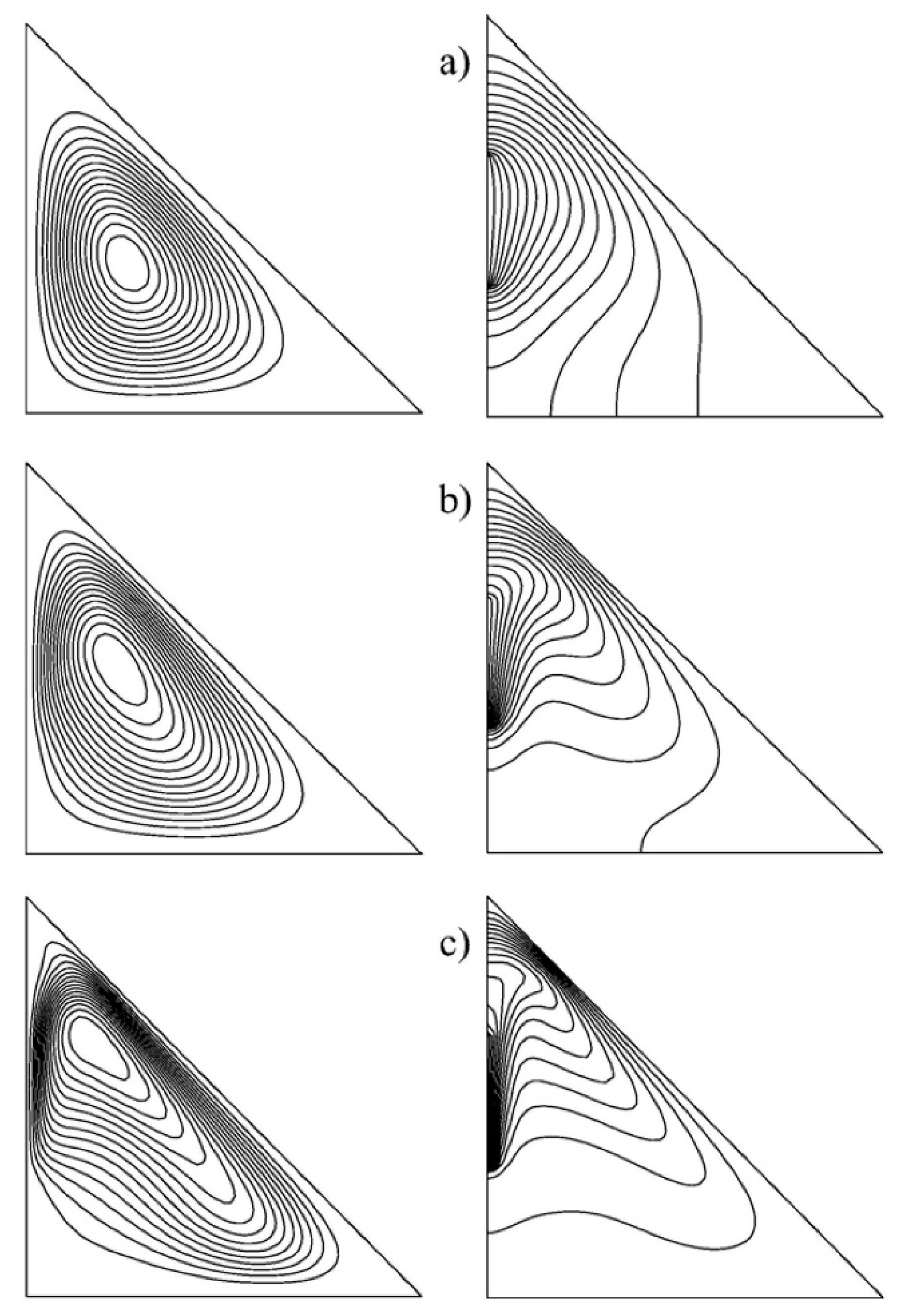

They presented streamlines and isotherms for different heating positions and in

Figure 24, results for P2 are presented below:

Right-angled triangular domain:

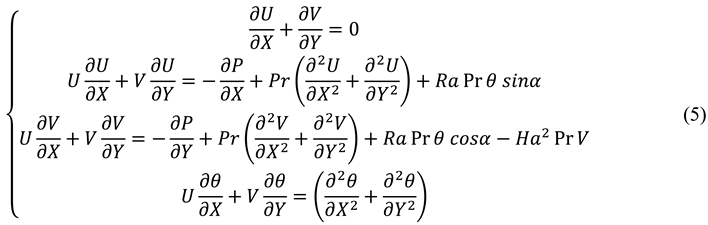

Ghasemi & Aminossadati studied mixed convection in a lid-driven triangular enclosure filled with Al

2O

3-H

2O nanofluids and physical domain is presented in

Figure 25. And the governing equations are presented in Eqs. (4). Thermophysical properties of Al

2O

3-H

2O nanofluids are presented in

Table 6.

where

Also, local and average Nusselt numbers are defined as

They presented average Nusselt number results for different Ri with the following assumptions:

Th = 303 K, Tc = 293 K, Pr = 6.2, Gr = 105, 0.01 ≤ Ri ≤ 100, 0 ≤ ϕ ≤ 0.05, 38 nm diameter of Al2O3 nanoparticles.

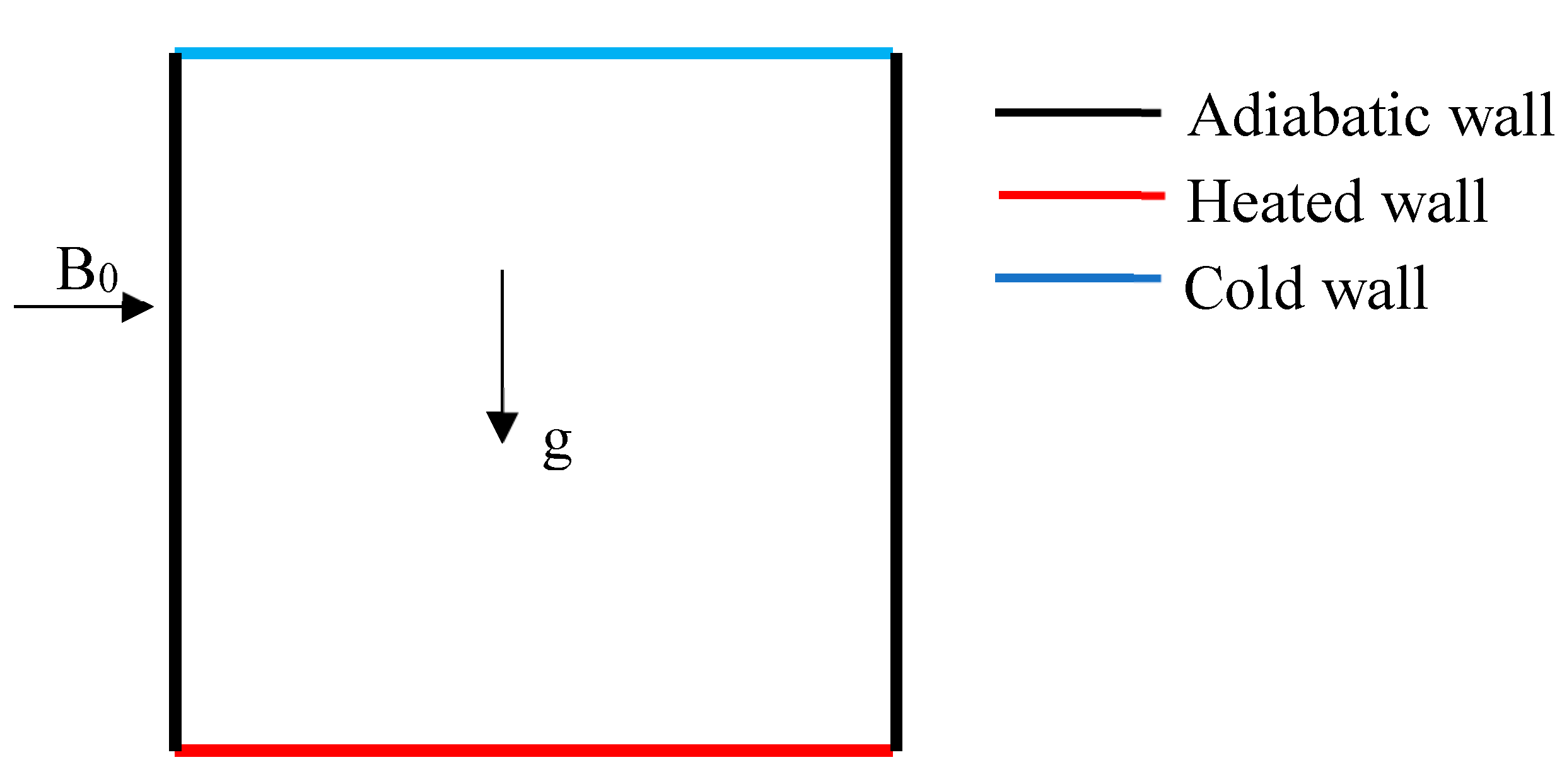

Square cavity with magnetic effect:

Pirmohammadi & Ghassemi (2009) studied the effect of magnetic field on convection heat transfer inside a tilted square enclosure as shown in

Figure 25. Governing equations are also presented in Eqs. (5).

Figure 25.

A square cavity filled with liquid gallium (Pr = 0.02) with magnetic effect.

Figure 25.

A square cavity filled with liquid gallium (Pr = 0.02) with magnetic effect.

They presented streamlines and isotherms for different Ra and Ha as shown in

Figure 26.

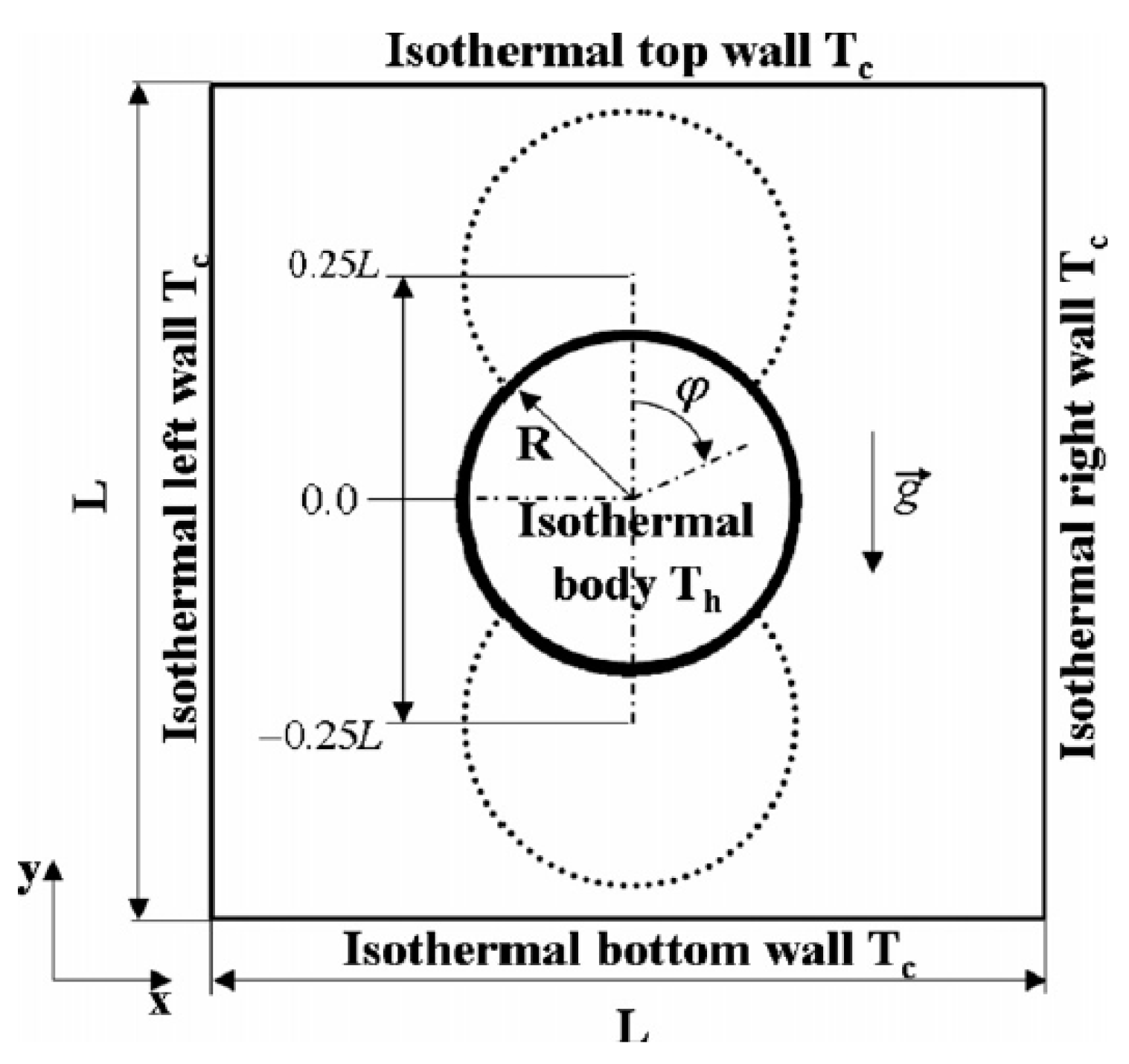

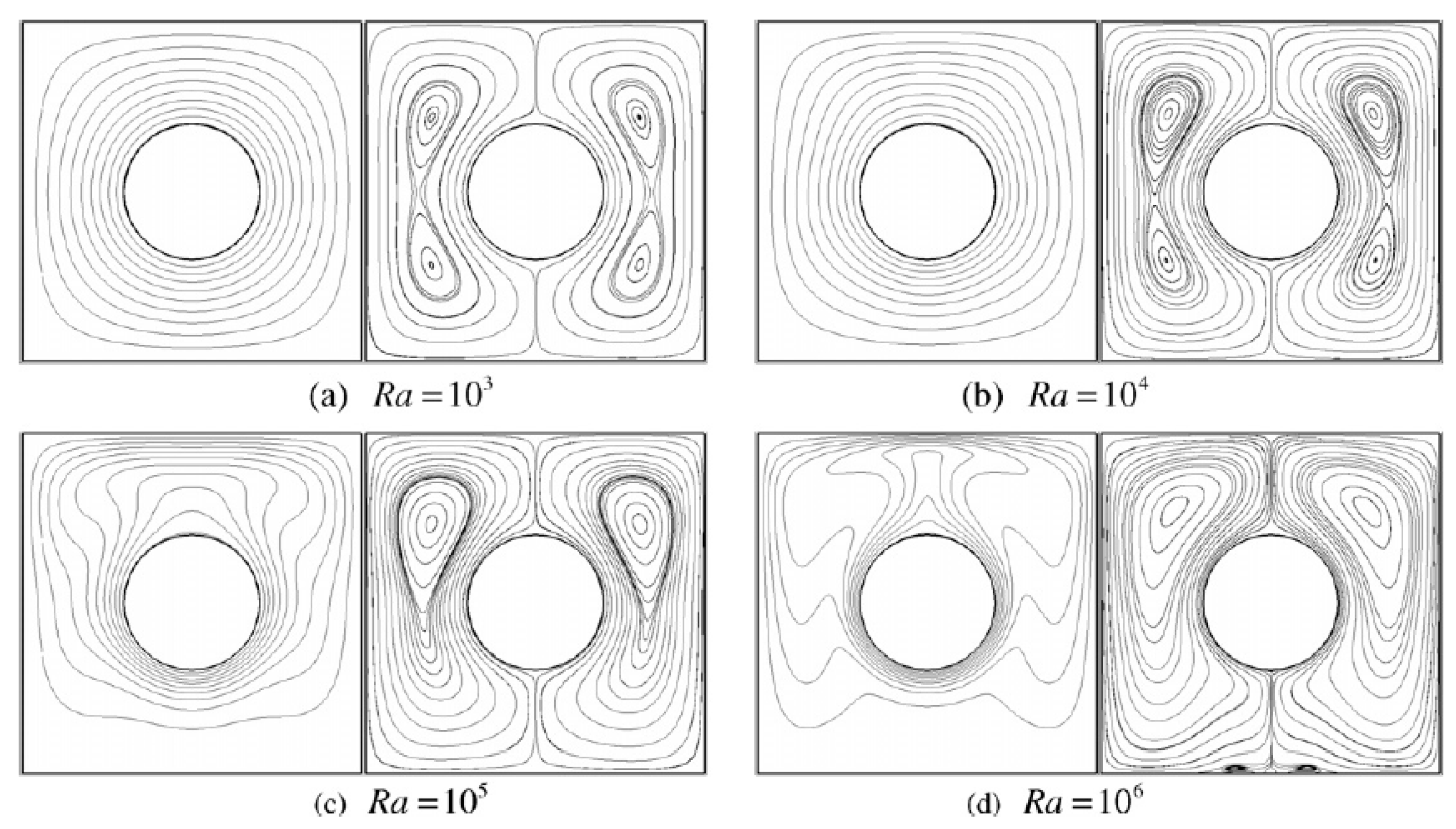

Kim et al. (2008) conducted a numerical study of natural convection in a square enclosure with a circular cylinder at different vertical locations as presented in

Figure 27. Governing equations are also presented in Eqs. 1a. Fluid is considered as air (Pr = 0.7) and radius of the circle is 0.2.

They presented flow and thermal fields for different Ra when heated cylinder is placed at the centerline position of the cavity. Results are presented in

Figure 28.

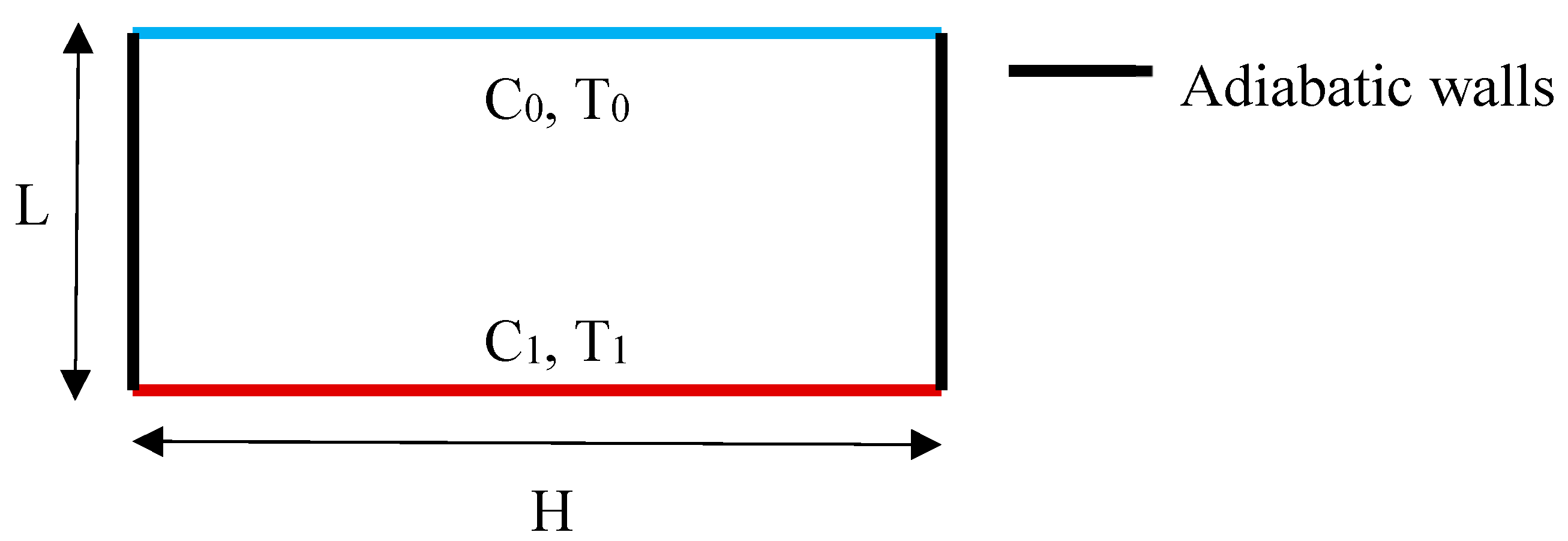

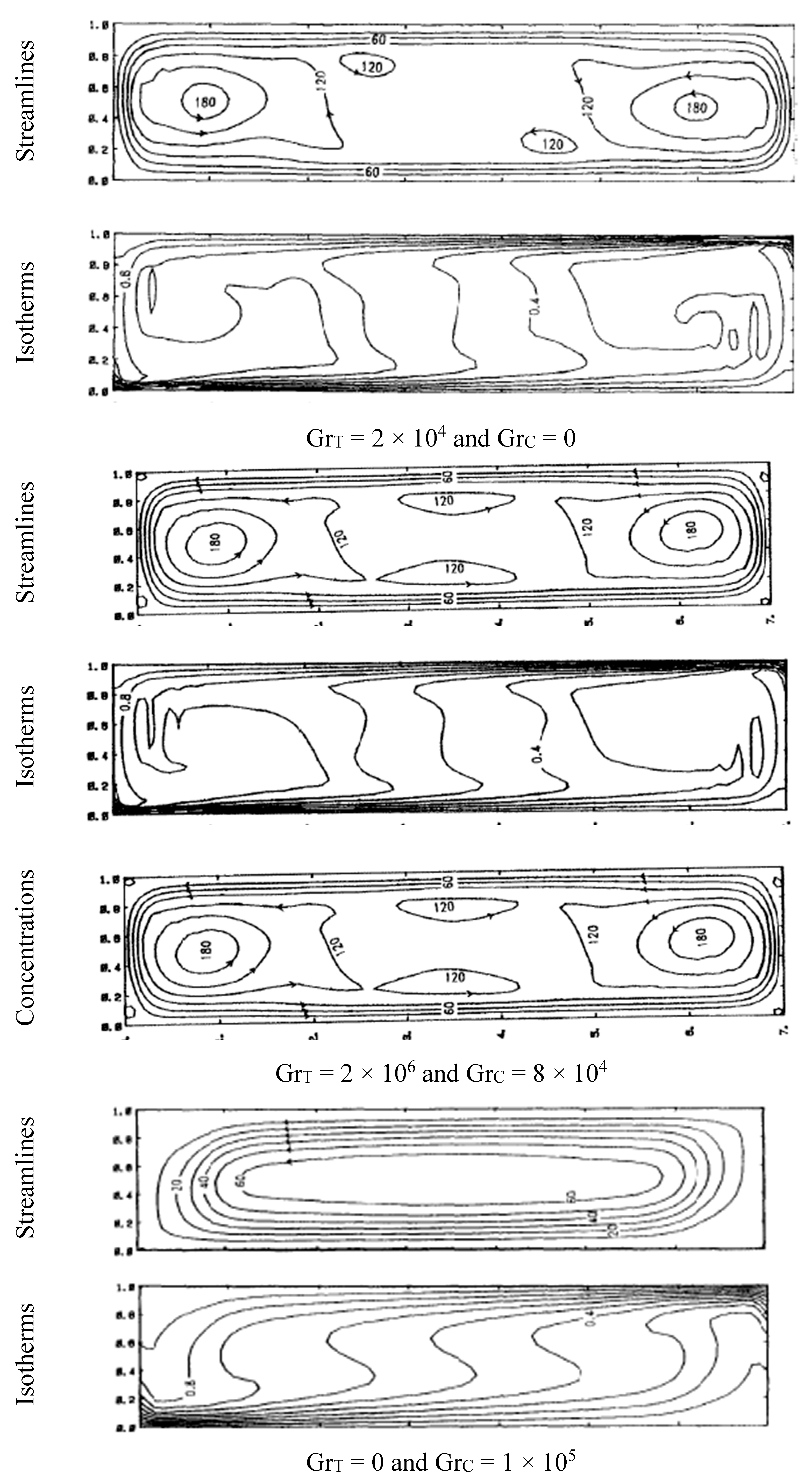

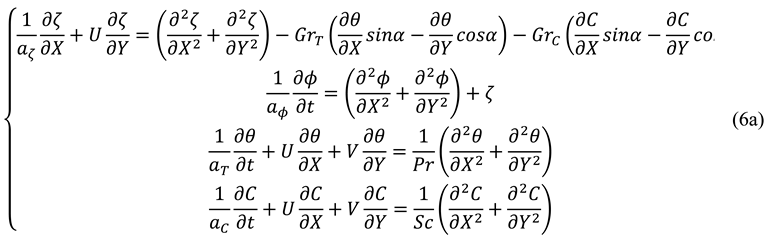

Wee et al. (1989) studied experimentally the heat and moisture transfer by natural convection in a rectangular cavity filled with air. Aspect ratio (H / L), Prandtl number and Schmidt numbers are considered as 7.0, 0.7, and 0.6 respectively and physical model is presented in

Figure 29. Ranges of thermal and concentration Grashof numbers were

The Boussinesq approximation and the assumptions of negligible viscous dissipation and compressibility effects, no internal heat/moisture source or sink being present and the fluid being Newtonian have been used in deriving equations. The non-dimensional governing equations such as vorticity and stream functions, conservation of energy and concentrations are presented below (Eqs. 6):

where

Streamlines and isotherms contours:

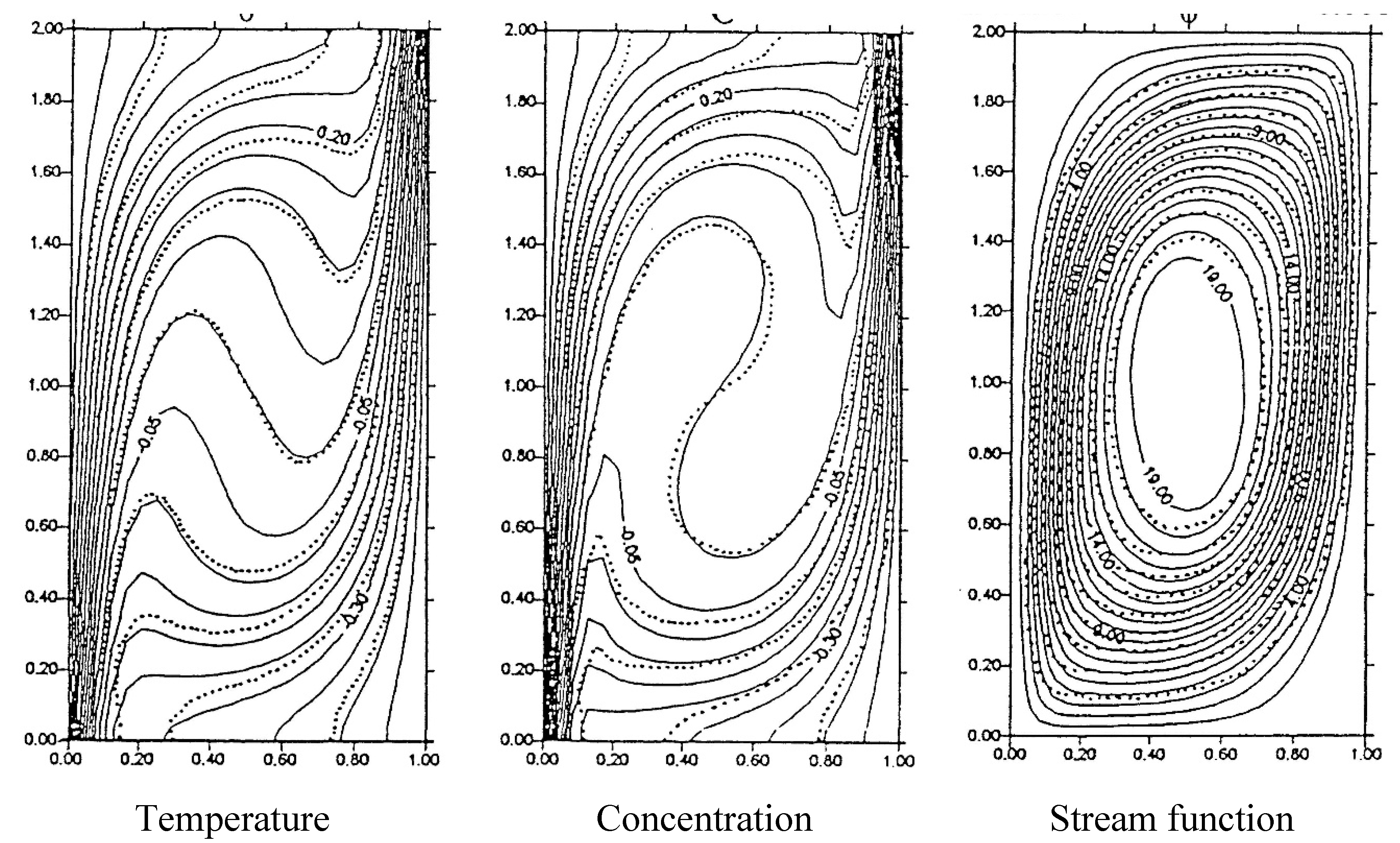

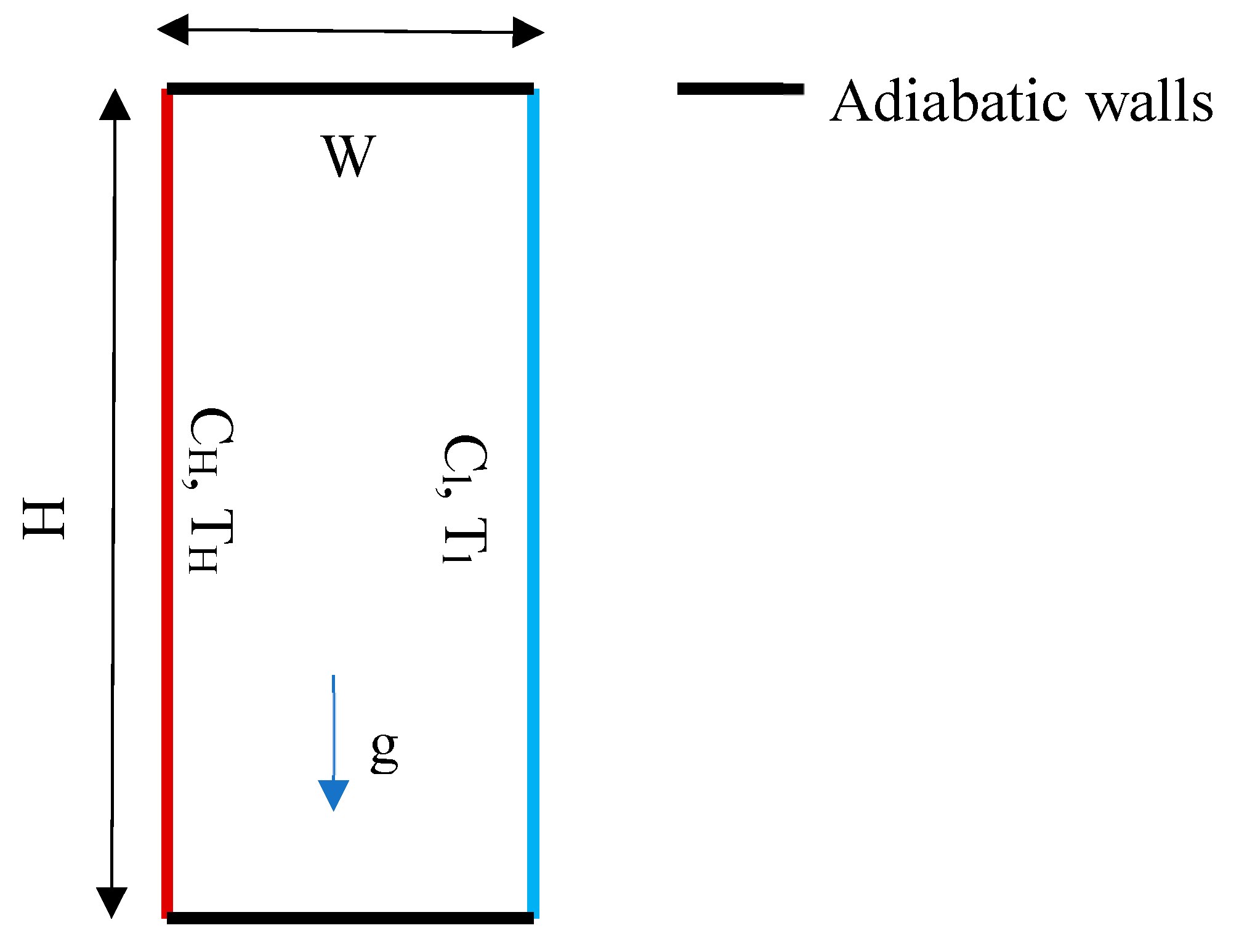

Nishimura et al. (1998) studied double diffusive natural convection inside a vertically oriented rectangular cavity as shown in

Figure 31 and parameters used in this study were thermal Rayleigh number (Ra

T) = 10

5, Prandtl number (Pr) = 1.0, Lewis number (Le) = 2, buoyancy ratio (N) = 0 - 2.0, Aspect ratio (A) = 2. The non-dimensional governing equations such as vorticity and stream functions, conservation of energy and concentrations are presented below (Eqs. 7):

Following results of temperature, concentration, and stream function are presented and later Chamkha & Al-Naser (2002) also regenerated their results.

Figure 31.

Results of temperature, concentration and stream function for Le = 2.0, N = 0.8, Pr = 1.0, RaT = 105. Here straight line represents the work of Chamkha & Al-Naser (2002) and dotted line represents the work of Nishimura et al. (1998).

Figure 31.

Results of temperature, concentration and stream function for Le = 2.0, N = 0.8, Pr = 1.0, RaT = 105. Here straight line represents the work of Chamkha & Al-Naser (2002) and dotted line represents the work of Nishimura et al. (1998).

Additional validation results can be found in Saha et al. (2023).

This document provides a comprehensive overview of validation studies conducted by various researchers and subsequently utilized by others to ensure the reliability of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations. The validation results presented cover a range of cavity configurations, flow conditions, and thermal behaviors, serving as benchmarks for assessing the accuracy of numerical models. The repeated use of these validation benchmarks by other researchers highlights their robustness and importance in advancing our understanding of natural convection, entropy generation, and heat transfer.

The validation results compiled in this document provide a valuable foundation for beginners in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) research. By presenting validated benchmarks for various cavity configurations and flow conditions, this work offers newcomers a reliable reference for assessing the accuracy of their simulations. These studies help beginners understand the importance of comparing numerical results with experimental data or analytical solutions to identify and address potential discrepancies in their models. Additionally, the documented results serve as practical examples of how to apply validation techniques, such as evaluating Nusselt numbers, entropy generation, and flow patterns. For beginners, replicating these validated scenarios can improve their grasp of CFD concepts, numerical methods, and the role of boundary conditions in simulation accuracy.

References

- Al-Badri, A. R., Al-Waaly, A. A. Y., Saha, G., Saha, T., & Saha, S. C. (2025). Improving thermal performance in building heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems: A study of natural convection and entropy in plus-shaped cavity. Heat Transfer (Hoboken, N.J. Print). [CrossRef]

- Al-Waaly, A.A.Y., Paul, A.R., Saha, G., & Saha, S.C. (2025). Exploring heat transfer and entropy generation in a dual cavity system, Heat Transfer. [CrossRef]

- Al-Waaly, A. A. Y., Paul, A. R., Saha, G., & Saha, S. C. (2024a). Entropy generation analysis of natural convection flow in porous diamond-shaped cavity. International Journal of Thermofluids, 23, 100801. [CrossRef]

- Al-Waaly, A. A. Y., Tumpa, S. A., Nag, P., Paul, A. R., Saha, G., & Saha, S. C. (2024b). Entropy generation associated with natural convection within a triangular porous cavity containing equidistant cold domains. Frontiers in Energy Research, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, S., Saha, S. C., Qiao, M., & Xu, F. (2019). Transition to a chaotic flow in a V-shaped triangular cavity heated from below. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 128, 76–86. [CrossRef]

- Chamkha, A. J., & Al-Naser, H. (2002). Hydromagnetic double-diffusive convection in a rectangular enclosure with uniform side heat and mass fluxes and opposing temperature and concentration gradients. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 41(10), 936–948. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. J. (2005). A numerical study on a lumped-parameter model and a CFD code coupling for the analysis of the loss of coolant accident in a reactor containment (No. FRCEA-TH--2308). Universite Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallee.

- Corvaro, F., & Paroncini, M. (2008). A numerical and experimental analysis on the natural convective heat transfer of a small heating strip located on the floor of a square cavity. Applied Thermal Engineering, 28(1), 25–35. [CrossRef]

- De Vahl Davis, G. (1983). Natural convection of air in a square cavity: A bench mark numerical solution. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids, 3(3), 249–264. [CrossRef]

- Flack, R. D. (1980). The experimental measurement of natural convection heat transfer in triangular enclosures heated or cooled from below. Journal of Heat Transfer, 102(4), 770–772. [CrossRef]

- Fusegi, T., Hyun, J. M., Kuwahara, K., & Farouk, B. (1991). A numerical study of three-dimensional natural convection in a differentially heated cubical enclosure. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 34(6), 1543–1557. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, B., & Aminossadati, S. M. (2010). Mixed convection in a lid-driven triangular enclosure filled with nanofluids. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 37(8), 1142–1148. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C. J., & Lin, F. H. (1997). Simulation of natural convection in a vertical enclosure by using a new incompressible flow formulation-pseudo-vorticity-velocity formulation. Numerical Heat Transfer. Part A, Applications, 31(8), 881–896. [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, G. A., Hill, R. W., & Ball, K. S. (2000). Laminar natural convection in isosceles triangular enclosures heated from below and symmetrically cooled from above. Journal of Heat Transfer, 122(3), 485–491. [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M. M., Saha, G., & Saha, S. C. (2021). Conjugate forced convection transient flow and heat transfer analysis in a hexagonal, partitioned, air filled cavity with dynamic modulator. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 167, 120786. [CrossRef]

- Ilis, G. G., Mobedi, M., & Sunden, B. (2008). Effect of aspect ratio on entropy generation in a rectangular cavity with differentially heated vertical walls. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 35(6), 696–703. [CrossRef]

- Iwatsu, R., Hyun, J. M., & Kuwahara, K. (1993). Mixed convection in a driven cavity with a stable vertical temperature gradient. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 36(6), 1601–1608. [CrossRef]

- Jihan, J. I., Saha, B. K., Nag, P., Moon, N. J., Saha, G., & Saha, S. C. (2024). Advancing thermal efficiency and entropy management inside decagonal enclosure with and without hot cylindrical insertions. International Journal of Thermofluids, 23, 100785. [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, K. (2007). A differential quadrature solution of natural convection in an enclosure with a finite-thickness partition. Numerical Heat Transfer. Part A, Applications, 51(10), 979–1002. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. S., Lee, D. S., Ha, M. Y., & Yoon, H. S. (2008). A numerical study of natural convection in a square enclosure with a circular cylinder at different vertical locations. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 51(7–8), 1888–1906. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-L., Chiou, J.-B., & Cyue, G.-S. (2019). Mixed convection in a square enclosure with a rotating flat plate. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 131, 807–814. [CrossRef]

- Lo, D. C., Young, D. L., Murugesan, K., Tsai, C. C., & Gou, M. H. (2007). Velocity–vorticity formulation for 3D natural convection in an inclined cavity by DQ method. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 50(3), 479–491. [CrossRef]

- Mussa, M. A., Abdullah, S., Nor Azwadi, C. S., & Muhamad, N. (2011). Simulation of natural convection heat transfer in an enclosure by the lattice-Boltzmann method. Computers & Fluids, 44(1), 162–168. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, E., Basak, T., & Roy, S. (2008). Natural convection flows in a trapezoidal enclosure with uniform and non-uniform heating of bottom wall. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 51(3), 747–756. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T., Wakamatsu, M., & Morega, A. M. (1998). Oscillatory double-diffusive convection in a rectangular enclosure with combined horizontal temperature and concentration gradients. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 41(11), 1601–1611. [CrossRef]

- Oliveski, R. D. C., Macagnan, M. H., & Copetti, J. B. (2009). Review: Entropy generation and natural convection in rectangular cavities. Applied Thermal Engineering, 29(8–9), 1417–1425. [CrossRef]

- Pirmohammadi, M., & Ghassemi, M. (2009). Effect of magnetic field on convection heat transfer inside a tilted square enclosure. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 36(7), 776–780. [CrossRef]

- Saboj, J. H., Nag, P., Saha, G., & Saha, S. C. (2023). Entropy production analysis in an octagonal cavity with an inner cold cylinder: A thermodynamic aspect. Energies (Basel), 16(14), 5487. [CrossRef]

- Saha, G., Saha, S., Islam, M. Q., & Akhanda, M. A. R. (2007). Natural convection in enclosure with discrete isothermal heating from below. Journal of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, 4(1), 1–13.

- Saha, G., Saha, S., Hasan, M. N., & Islam, M. Q. (2010). Natural convection heat transfer within octagonal enclosure. International Journal of Engineering, Transactions A: Basics, 23(1), 1–10.

- Saha, G., Al-Waaly, A. A. Y., Paul, M. C., & Saha, S. C. (2023). Heat Transfer in Cavities: Configurative Systematic Review. Energies (Basel), 16(5), 2338. [CrossRef]

- Saha, T., Saha, G., Parveen, N., & Islam, T. (2024). Unsteady magneto-hydrodynamic behavior of TiO2-kerosene nanofluid flow in wavy octagonal cavity. International Journal of Thermofluids, 21, 100530. [CrossRef]

- Saha, B. K., Jihan, J. I., Barai, G., Moon, N. J., Saha, G., & Saha, S. C. (2025). Exploring natural convection and heat transfer dynamics of Al2O3-H2O nanofluid in a modified tooth-shaped cavity configuration. International Journal of Thermofluids, 25, 101005. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M. A. R., & Mohammad, T. R. (2005). Natural convection in cavities with constant flux heating at the bottom wall and isothermal cooling from the sidewalls. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 44(9), 865–878. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R. K., & Das, M. K. (2007). Heat transfer augmentation in a two-sided lid-driven differentially heated square cavity utilizing nanofluids. International Journal of heat and Mass transfer, 50(9-10), 2002-2018.

- Varol, Y., Koca, A., & Oztop, H. F. (2006). Natural convection in a triangle enclosure with flush mounted heater on the wall. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 33(8), 951–958. [CrossRef]

- Wan, D. C., Patnaik, B. S. V., & Wei, G. W. (2001). A new benchmark quality solution for the buoyancy-driven cavity by discrete singular convolution. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part B: Fundamentals, 40(3), 199-228. [CrossRef]

- Wee, H. K., Keey, R. B., & Cunningham, M. J. (1989). Heat and moisture transfer by natural convection in a rectangular cavity. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 32(9), 1765–1778. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A square cavity filled with Air.

Figure 1.

A square cavity filled with Air.

Figure 2.

Variation of Isotherms and Streamlines profiles for different Ra.

Figure 2.

Variation of Isotherms and Streamlines profiles for different Ra.

Figure 3.

Variation of entropy generation due to fluid friction, entropy generation due to heat transfer, total entropy generation and Bejan number with Ra.

Figure 3.

Variation of entropy generation due to fluid friction, entropy generation due to heat transfer, total entropy generation and Bejan number with Ra.

Figure 4.

A square cavity filled with Air.

Figure 4.

A square cavity filled with Air.

Figure 5.

Variation of Isotherms for Ra = 2.02 × 105.

Figure 5.

Variation of Isotherms for Ra = 2.02 × 105.

Figure 6.

Regular Octagonal domain filled with Air.

Figure 6.

Regular Octagonal domain filled with Air.

Figure 7.

Variation of isotherms and streamlines for different Ra.

Figure 7.

Variation of isotherms and streamlines for different Ra.

Figure 8.

Octagonal cavity with circular cold cylinder inserts.

Figure 8.

Octagonal cavity with circular cold cylinder inserts.

Figure 9.

Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different Ra for Pr = 0.71.

Figure 9.

Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different Ra for Pr = 0.71.

Figure 10.

Trapezoidal enclosure with uniform/non-uniform heating from bottom.

Figure 10.

Trapezoidal enclosure with uniform/non-uniform heating from bottom.

Figure 11.

variation of isotherms for Pr = 0.7, Ra = 105.

Figure 11.

variation of isotherms for Pr = 0.7, Ra = 105.

Figure 12.

Isosceles triangular cavity with Pr = 0.71.

Figure 12.

Isosceles triangular cavity with Pr = 0.71.

Figure 13.

a: Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different Gr for Pr = 0.71, A = 1.0.

Figure 13.

a: Variation of streamlines and isotherms with different Gr for Pr = 0.71, A = 1.0.

Figure 13.

b: Streamlines and isotherms profiles with different Gr for Pr = 0.71, A = 0.5.

Figure 13.

b: Streamlines and isotherms profiles with different Gr for Pr = 0.71, A = 0.5.

Figure 14.

Square cavity with rotating blade.

Figure 14.

Square cavity with rotating blade.

Figure 15.

Variation of temperature profile, velocity profile and spatially average Nusselt number at X = 0.08 (Present study indicates the results of Ikram et al. 2021).

Figure 15.

Variation of temperature profile, velocity profile and spatially average Nusselt number at X = 0.08 (Present study indicates the results of Ikram et al. 2021).

Figure 16.

Lid-driven square cavity.

Figure 16.

Lid-driven square cavity.

Figure 17.

Profiles of horizontal (X = 0.5) and vertical (Y = 0.5) velocities at Gr = 102 when a. Re = 100, b. Re = 400, c. Re = 1000, d. Re = 3000

Figure 17.

Profiles of horizontal (X = 0.5) and vertical (Y = 0.5) velocities at Gr = 102 when a. Re = 100, b. Re = 400, c. Re = 1000, d. Re = 3000

Figure 18.

Streamlines and isotherms profiles for Re = 103, Gr = 102.

Figure 18.

Streamlines and isotherms profiles for Re = 103, Gr = 102.

Figure 21.

Idealized triangular cavity.

Figure 21.

Idealized triangular cavity.

Figure 22.

Temperature profile at the midline, x = 0 for Gr = 6.25 × 105.

Figure 22.

Temperature profile at the midline, x = 0 for Gr = 6.25 × 105.

Figure 23.

Right-angle triangular cavity with different heated positions. [ a. Position 1 (P1), b. Position 2 (P2), c. Position 3 (P3) ]

Figure 23.

Right-angle triangular cavity with different heated positions. [ a. Position 1 (P1), b. Position 2 (P2), c. Position 3 (P3) ]

Figure 24.

Streamlines (on the left) and isotherms (on the right) for different Ra at h = H/3, AR = 1, Pr = 0.71 at the position of P2, a) Ra = 104, b) Ra = 105, c) Ra = 106.

Figure 24.

Streamlines (on the left) and isotherms (on the right) for different Ra at h = H/3, AR = 1, Pr = 0.71 at the position of P2, a) Ra = 104, b) Ra = 105, c) Ra = 106.

Figure 25.

Right triangular domain with moving vertical wall (L /H = 1).

Figure 25.

Right triangular domain with moving vertical wall (L /H = 1).

Figure 26.

Variation of streamlines and isotherms at

Figure 26.

Variation of streamlines and isotherms at

Figure 27.

Physical domain with heated circular cylinder insert.

Figure 27.

Physical domain with heated circular cylinder insert.

Figure 28.

Flow and thermal fields for different Ra.

Figure 28.

Flow and thermal fields for different Ra.

Figure 29.

Rectangular cavity filled with air.

Figure 29.

Rectangular cavity filled with air.

Figure 30.

Variation of streamlines, isotherms, concentrations for different GrT and GrC.

Figure 30.

Variation of streamlines, isotherms, concentrations for different GrT and GrC.

Figure 31.

Vertical rectangular cavity.

Figure 31.

Vertical rectangular cavity.

Table 1.

Variation of average Nusselt number (Nuavg) for different Ra.

Table 1.

Variation of average Nusselt number (Nuavg) for different Ra.

| Ra |

Average Nusselt number (Nuavg) |

| Corvaro & Paroncini (2008) |

Saha et al. (2010) |

| 7.56 × 104

|

4.80 |

5.31 |

| 1.38 × 105

|

5.86 |

6.07 |

| 1.71 × 105

|

6.30 |

6.37 |

| 1.98 × 105

|

6.45 |

6.58 |

| 2.32 × 105

|

6.65 |

6.82 |

| 2.50 × 105

|

6.81 |

6.94 |

Table 2.

Variation of average Nusselt number (Nuavg) for different Ra.

Table 2.

Variation of average Nusselt number (Nuavg) for different Ra.

| Pr = 0.71 |

Nuavg

|

| Ra |

104

|

105

|

106

|

| De Vahl Davis (1983) |

2.243 |

4.519 |

8.799 |

| Fusegi et al. (1991) |

2.302 |

4.646 |

9.012 |

| Ho and Lin (1997) |

2.248 |

4.528 |

8.824 |

| Wan et al. (2001) |

2.254 |

4.598 |

8.976 |

| Choi (2005) |

2.243 |

4.519 |

8.820 |

| Kahveci (2007) |

2.240 |

4.520 |

8.820 |

| Lo et al. (2007) |

2.054 |

4.333 |

8.668 |

| Tiwari and Das (2007) |

2.195 |

4.450 |

8.803 |

| Oliveski et al. (2009) |

2.239 |

4.551 |

8.726 |

| Al-Waaly et al. (2025) |

2.235 |

4.577 |

8.552 |

Table 3.

a: Variation of average Nusselt number for different Gr.

Table 3.

a: Variation of average Nusselt number for different Gr.

| Average Nusselt number for A = 1.0, Pr = 0.71 |

| Gr |

Holtzman et al. (2000) |

Al-Waaly et al. (2024b) |

| 103

|

1.00 |

1.00 |

| 104

|

1.07 |

1.09 |

| 105

|

1.80 |

1.90 |

Table 3.

b: Variation of average Nusselt number for different Aspect ratio, A.

Table 3.

b: Variation of average Nusselt number for different Aspect ratio, A.

| Average Nusselt number for Gr = 105, Pr = 0.71 |

| A |

Holtzman et al. (2000) |

| 1.0 |

1.80 |

| 0.5 |

2.19 |

| 2.0 |

2.48 |

Table 4.

Variation of average Nusselt number at the top moving wall with different Re and Gr for Pr = 0.71.

Table 4.

Variation of average Nusselt number at the top moving wall with different Re and Gr for Pr = 0.71.

| Re |

Gr = 102

|

Gr = 104

|

Gr = 106

|

| 100 |

1.94 |

1.34 |

1.02 |

| 400 |

3.84 |

3.62 |

1.22 |

| 1000 |

6.33 |

6.29 |

1.77 |

Table 6.

Thermophysical properties of water and Al2O3.

Table 7.

Variation of average Nusselt number with different Ri values.

Table 7.

Variation of average Nusselt number with different Ri values.

| Ri |

ϕ = 0 |

ϕ = 0.01 |

ϕ = 0.02 |

ϕ = 0.03 |

ϕ = 0.04 |

ϕ = 0.05 |

| 0.01 (Up) |

33.275 |

34.470 |

35.679 |

36.904 |

38.145 |

39.405 |

| 0.01 (Down) |

44.029 |

45.522 |

47.010 |

48.493 |

49.972 |

51.447 |

| 0.1 (Up) |

29.356 |

30.326 |

31.298 |

32.274 |

33.253 |

34.236 |

| 0.1 (Down) |

29.330 |

30.119 |

30.907 |

31.695 |

32.483 |

33.273 |

| 1.0 (Up) |

11.073 |

11.463 |

11.858 |

12.258 |

12.663 |

13.074 |

| 1.0 (Down) |

21.381 |

21.912 |

22.442 |

22.974 |

23.507 |

24.043 |

| 10 (Up) |

11.073 |

11.463 |

11.858 |

12.250 |

12.663 |

13.074 |

| 10 (Down) |

16.808 |

17.270 |

17.734 |

18.201 |

18.671 |

19.145 |

| 100 (Up) |

11.318 |

11.726 |

12.138 |

12.552 |

12.970 |

13.392 |

| 100 (Down) |

14.187 |

14.627 |

15.069 |

15.514 |

15.962 |

16.413 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

where

where