1. Introduction

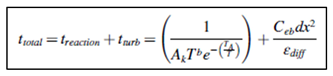

Gas flaring refers to the controlled combustion of natural gas that cannot be processed for sale or use due to technical or economic constraints. It is also the process of using specially designed combustion devices to safely and efficiently dispose of waste gases produced during regular plant operations. These waste gases come from various sources, such as associated gas, gas processing plants, well testing, and other facilities. The waste gas is typically collected in piping headers and directed to a flare system for safe disposal. A flare system usually consists of multiple flares to manage waste gases from different sources [

1,

2]. Flaring typically takes place at the top of a stack, where the gases are ignited, creating a visible flame. The height of the flame is directly related to the volume of gas being released, while its brightness and color are influenced by the specific composition of the gas. A complete flare system consists of the flare stack or boom, along with the pipes that collect and channel the gases to be flared [

3], as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The flare tip at the top of the stack is engineered to promote the entrainment of air into the flare, thereby improving combustion efficiency. Seals are installed along the stack to prevent the flame from flashing back into the system. At the base of the stack, a vessel collects and conserves any liquids that may result from the gas flow to the flare. Depending on the specific design and requirements of the process, one or more flares may be needed at a given location to manage the waste gases effectively. A flare is usually visible and produces not only light but also noise and heat. During the flaring process, the combustion of the gas primarily results in the formation of water vapor and CO

2. For efficient combustion to occur, it is crucial to ensure proper mixing of the fuel gas with air (or steam), which facilitates complete combustion and minimizes the emission of unburned hydrocarbons and other pollutants [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Flaring processes can be classified into three main types: emergency flaring, process flaring, and production flaring [

9]. Emergency flaring occurs in response to situations like fires, valve failures, or compressor breakdowns, where a large volume of gas is burned at high velocity over a short duration. Process flaring generally involves a lower rate of flaring, such as during the removal of waste gases from the production stream in petrochemical processes. The volume of gas flared in process flaring can range from a few cubic meters per hour during normal operations to thousands of cubic meters per hour during plant failures [

10]. Production flaring, on the other hand, occurs within the exploration and production sector of the oil and gas industry. It involves burning large volumes of gas during gas-oil potential tests, which are performed to assess the production capacity of a well [

3].

Gas flaring serves as both a method of waste disposal and a safety mechanism to relieve pressure by burning excess gas from wells, hydrocarbon processing facilities, or refineries [

11]. On a global scale, gas flaring represents a significant environmental and energy challenge, with millions of tonnes of CO₂ and other greenhouse gases (GHG) released into the atmosphere each year, contributing to global warming. In 2023, approximately 148 billion cubic meters of gas were burned worldwide through gas flaring in oilfields, resulting in the emission of around 400 million tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere [

12,

13].

Flaring is generally regarded as the largest source of loss in several industrial sectors, including oil and gas production, chemical plants, refineries, coal industries, and landfills. This practice results in the waste of various gases, including process gases, fuel gas, steam, nitrogen, and natural gas. Flaring systems are widely used across different locations, such as onshore and offshore production fields, transport ships, port facilities, storage tank farms, and distribution pipelines. Furthermore, gas flaring is considered a cleaner energy source compared to many commercial fossil fuels, as the composition of flared gas closely resembles that of natural gas [

14].

Recently, the significance of flare gas has grown, with increasing attention on the quantities of gas being wasted. This concern has risen due to the continuous increase in gas prices since 2005, alongside growing worries about the limited availability of oil and gas resources. Studies have shown that the amount of gas flared, if utilized as an energy source, could potentially meet 50% of Africa's electricity needs [

15]. In fact, saving energy and reducing emissions have become global priorities. Additionally, minimizing flaring and maximizing the use of fuel gas contribute significantly to energy efficiency and climate change mitigation [

16].

Gas flaring represents one of the most significant energy and environmental challenges facing the world today. Its environmental impacts are far-reaching, particularly for local communities, where it often leads to serious health issues. Gas flaring is typically visible and produces both noise and heat [

11]. The release of greenhouse gases (GHGs) like CO

2 and CH

4 directly into the atmosphere traps heat, contributing significantly to climate change. These gases have a clear and substantial impact on the environment, making them major contributors to global GHG emissions [

17]. Gas flaring has been a driving factor in rising global temperatures and has rendered large areas uninhabitable due to its environmental consequences. CO

2 emissions from flaring have a high global warming potential, playing a major role in climate change. Around 75% of CO

2 emissions stem from the combustion of fossil fuels [

18]. CH

4, a gas commonly found in flares with lower combustion efficiency, is even more harmful than CO

2, with a global warming potential roughly 25 times greater than CO

2 on a mass basis. This has raised concerns regarding the release of CH

4 and other volatile organic compounds from various industrial operations [

19,

20].

Other pollutants, such as sulfur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), are also released during the flaring process [

11,

18,

21,

22,

23]. A study by Ezersky and Lips in 2003 [

22] on emissions from oil refinery flare systems in the Bay Area Management District (California) found that emissions ranged from 2.5 to 55 tons per day of total organic compounds and from 6 to 55 tons per day of SOx. As a result, flare emissions can contribute significantly to overall SO

2 and VOC emissions. Once emitted, gaseous pollutants like SO

2 have no boundaries, becoming uncontrollable and contributing to acid deposition. Numerous toxicological and epidemiological studies have revealed the severe effects of these gases [

24]. SOx and NOx are key contributors to acid rain and fog, which damage the natural environment and harm human health. Additionally, ozone, produced by the photochemical reaction of VOCs and NOx, exacerbates the damage by accelerating the oxidation of SO

2 and NOx into toxic sulfuric and nitric acids, respectively. Therefore, reducing VOC and NOx emissions is essential for lowering ozone concentrations [

25].

On the other hand, a smoking flare can significantly contribute to overall particulate emissions. Most flared gas is untreated or unprocessed, leading to challenging service conditions. This can result in issues such as condensation, fouling (e.g., from the buildup of paraffin wax and asphaltine deposits), corrosion (e.g., due to the presence of H

2S, moisture, or air), and possibly abrasion (e.g., from debris, dust, and corrosion products in the piping and high flow velocities) [

26].

The quantity of emissions generated from flaring is largely determined by the combustion efficiency [

4]. Several factors influence this efficiency, such as the heating value, velocity of gases entering the flare, meteorological conditions, and their impact on flame size. When flares are properly operated, they can achieve combustion efficiency levels of at least 98%, meaning that hydrocarbon and CO emissions represent less than 2% of the species in the gas stream [

10]. This highlights the high efficiency of well-designed and well-operated industrial flares. However, flare efficiencies can vary significantly, ranging from 62% to 99% [

27,

28]. Gas flaring can have a considerable environmental impact, particularly due to the potential presence of harmful compounds, with the extent of the impact depending on the composition of the flared gas [

4].

The aim of this paper is to evaluate a utility flare (55 m in height and 0.61 m in diameter) operation in one of the oilfield sites in Iraq during two gas firing rates low with 9 t/hr and high 45 t/hr under different operational conditions using CFD code C3d version (5-20-24). This includes the environmental and safety aspects of the flare operation under different operational conditions by studying the effect of stack height and crosswind on the amount of thermal radiation and pollution released from the burning flare gas during both firing rates. Moreover, this work evaluates the amount of pollutants in the plume generated during both gas firing rates.

2. Methodology

This paper uses CFD code C3D based on LES approach version (5-20-24) to analyze the operation of a routine utility flare during low and high firing rates in the summer in Iraq. The analysis focuses on both safety and environmental reviews of the flare operation under different gas firing conditions: a low rate of 9 t/hr and a high rate of 45 t/hr. The study also examines the impact of three different crosswind speeds (4 m/s, 8 m/s, and 14 m/s) and three different stack heights (35 m, 45 m, and 55 m) to understand how these factors affect radiation rates to the ground and pollution dispersion.

The chosen flow rates reflect practical and safety considerations for routine operations. The low gas firing rate represents the typical operational rate during routine flare activities. The high gas firing rate, while below the maximum allowable rate of

250 t/hr, was selected because it is more likely to occur under routine conditions compared to the maximum rate, which is typically associated with emergency flare operations. The flare height and diameter used in this study were 55 m and 0.61 m (24″), respectively.

Table 1 shows flare gas composition used in this study.

Additionally, ParaView software 5.12.1 was used to visually represent the flare operation at both gas firing rates. The software enables visualization of ground radiation and allows for the extraction of combustion products, which are essential for evaluating the pollution rate from burning flare gas. This integrated approach helps to assess the environmental impact of flare operation under various conditions and provides a clear representation of the flare’s behavior during routine and maximum operation scenarios.

2.1. CFD Code C3d

C3d is a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and heat transfer software developed by the USDOE Sandia National Laboratory, designed to tackle a wide range of fluid mechanics and heat transfer problems, including flare and fire analysis. It uses the Large Eddy Simulation (LES) methodology to perform transient analyses of flare operations. In flare studies, C3d is commonly applied to estimate flame shapes and the associated emissions. The software includes several optional sub-models that simulate various processes, such as deposition, radiation heat transfer, aerosol transport, chemical reactions, combustion, and material decomposition.

For fire and flare scenarios, C3d models important phenomena such as fuel vapor transport, liquid fuel evaporation, combustion products, heat release, and chemical reactions. It also accounts for soot and intermediate species formation and destruction, diffusion radiation within the fire, and radiation view factors from the fire's edge to nearby objects. The software selects soot radiation and reaction rates based on comparisons with experimental data from flare and fire studies. To model fluid flow around solid objects, C3d employs a body-fitted geometry method, combined with a structural orthogonal Cartesian grid. This approach allows for both fine and coarse discretization while accurately representing the curvature of objects within the flow domain.

The C3d code has been widely used in various studies [

29,

30], including those evaluating flare performance and fire safety. Originally developed as a CFD tool called ISIS-3D, it was validated for simulating pool fires and assessing the thermal performance of nuclear transport packages [

31,

32,

33]. The C3d code has been applied in multiple studies to analyze different types of flares, such as utility flares, air-assisted flares, and large multipoint ground flares [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Its combustion model has been enhanced and validated for a variety of flare gases like propane, methane, ethylene, ethane, propylene, and xylene. The code helps estimate flame size, shape, and the impact of smoking tendencies, as well as heat flux to the ground [

38].

C3d has also been employed in studies involving multipoint ground flares to assess the effect of surrounding wind fences on flame height and shape under high firing conditions [

36]. It has proven useful in determining the optimal spacing between flare tips to ensure sufficient airflow during operation, thus preventing smoke under maximum firing conditions. Moreover, the code has been used to investigate the impact of discrete and continuous ignition systems on flare operation [

35].

2.2. Physical Model

In all simulations, the LES turbulence model was employed to simulate fluid flow, while radiation effects were incorporated into the energy equation. To monitor the distribution and concentration of the fuel, soot, intermediate species, and combustion products (such as H2O and CO2), individual species equations were solved. The combustion model provided the sink and source terms for these species equations, based on local gas temperature, species concentrations, and turbulent diffusivity.

The code predicted flame emissivity using various models that considered factors such as soot volume fraction, molecular gas composition, flame size, shape, and the temperature profile of the combustion effluent. These factors were derived from the solutions to the momentum, mass, species, and energy equations. Additionally, a radiation transport model was used to predict the radiation flux from the flame to the ground and to provide the sink and source terms for the energy equation, allowing for the prediction of the flame's temperature distribution.

2.3. Chemical and Soot Model

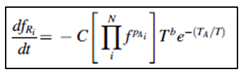

A combination of Arrhenius and Eddy breakup reaction time scales have been used to define the rate of combustion equations.

(T) = a local gas temperature, (A

k) = a pre-exponential coefficient, (b) = a global exponent, (C

eb) = the eddy breakup scaling factor, (T

A) = activation temperature, (dx) = the characteristic cell size, (t

turb) = the turbulence time scale, and (ε

diff) = the eddy diffusivity from LES module [

34].

Combustion chemistry consists of several critical reactions. Initially, primary fuel breakdown reactions generate intermediate combustion products such as C₂H₂, H₂, CH₄, soot, and CO. These intermediate products undergo secondary reactions that further combust, contributing to soot formation. Additionally, reforming reactions that involve hydroxyl (OH) radicals play a significant role in the process. In this scenario, oxidizing species are simplified to water vapor. To promote soot formation, equilibrium reactions involving acetylene, methane, hydrogen, sulfur, and hydrogen sulfide are also included in the model [

34].

The primary fuel breakdown, secondary and reforming reactions of the flared gas mixture are shown below:

| The primary fuel breakdown reactions |

| CH4 + O2 → 0.33C2H2 + 0.33CO + 1.67H2O |

CH4 Breakdown |

| C2H6 + 1.5O2 → C2H2 + 2H2O + CO |

C2H6 Breakdown |

| C3H8 + 2O2 → C2H2 + 3H2O + CO |

C3H8 Breakdown |

| C4H10 + 3O2 → C2H2 + 4H2O + 2CO |

C4H10 Breakdown |

| C5H12 + 2.5O2 → 2C2H2 + 4H2O + CO |

C5H12 Breakdown |

| H2S + O2 → SO2 +H2 |

H2S Breakdown |

| N2 + O2 → 2NO |

N2 Breakdown |

| The secondary reactions |

| H2 + 0.5O2 → H2O |

H2 Combustion |

| C2H2 + 0.8O2 → 1.6CO + H2 + 0.02C20

|

Soot nucleation soot formation |

| C2H2 + 0.01C20 → H2 + 0.11C20

|

Soot growth by acetylene addition |

| CO + 0.5O2 → CO2 |

CO combustion |

| C20 + 10O2 → 20CO |

Soot combustion |

| C2H2 + 3H2 → 2CH4 |

Acetylene decomposition |

| CH4 + CH4 → C2H2 + 3H2

|

Acetylene formation |

| 0.5S2 + H2 → H2S |

Sulfur reduction to hydrogen sulfide |

| H2S → 1.5S2 + H2 |

Hydrogen sulfide decomposition |

| H2S + 0.5SO2 → 0.75S2 + H2O |

Elemental sulfur formation |

| The reforming reactions |

| C20 + 20H2O → 20CO + 20H2

|

Soot steam reforming |

| 0.75S2 + H2O → H2S + 0.5SO2

|

Sulfur steam reforming |

A global Arrhenius rate mode is used for these reactions. The consumption of fuel, soot, and intermediate species are evaluated by:

(

N) = number of reactants, (

TA) = effective activation temperature, (

fRi) = moles of each reactant, (

i) and (c) = pre-exponential coefficient, and (

b) = temperature exponent.

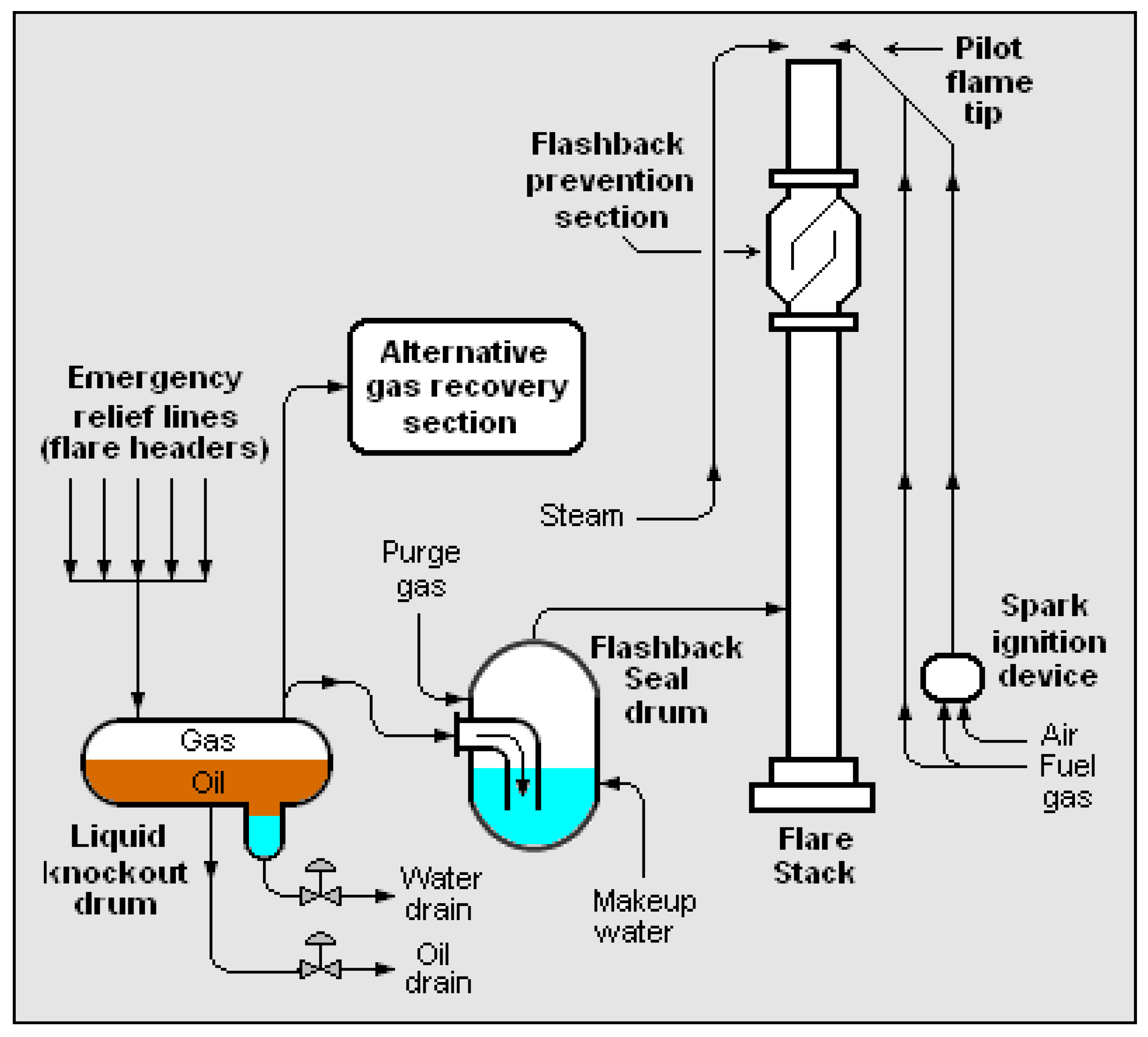

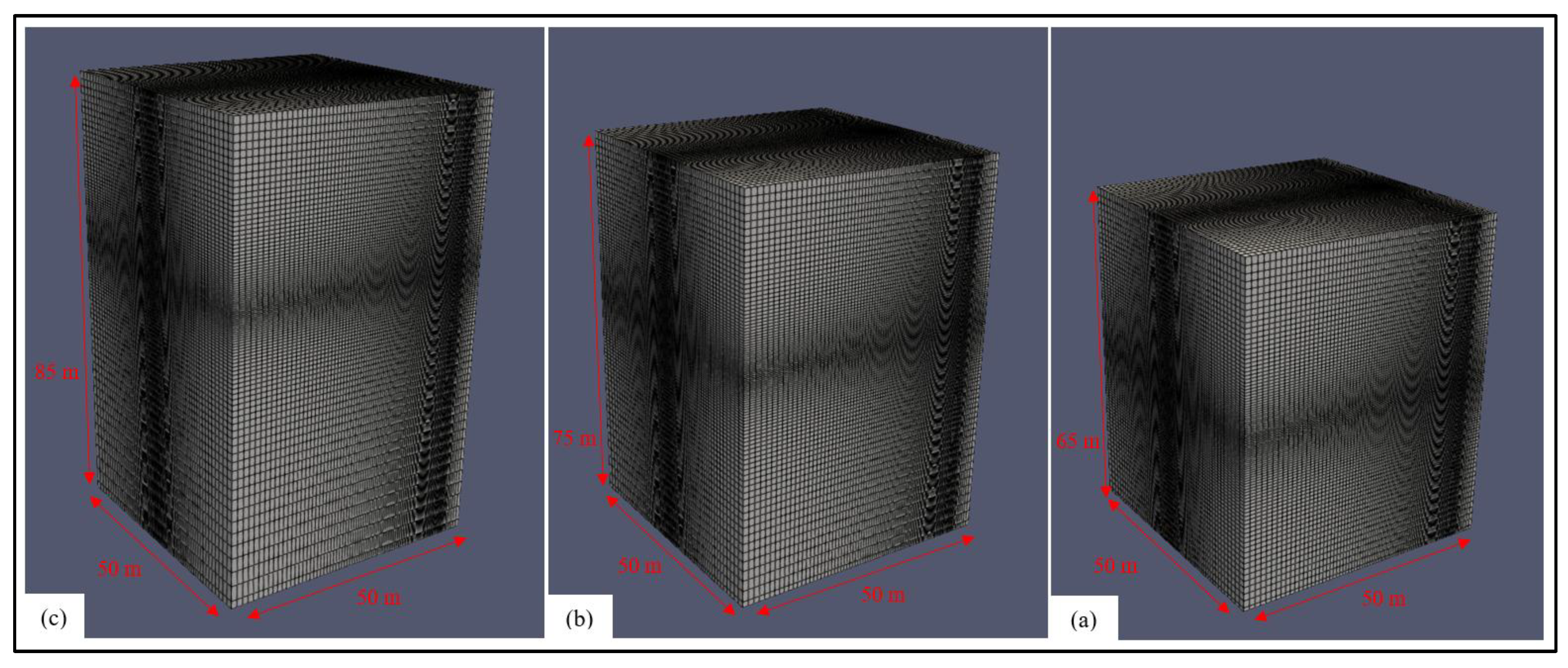

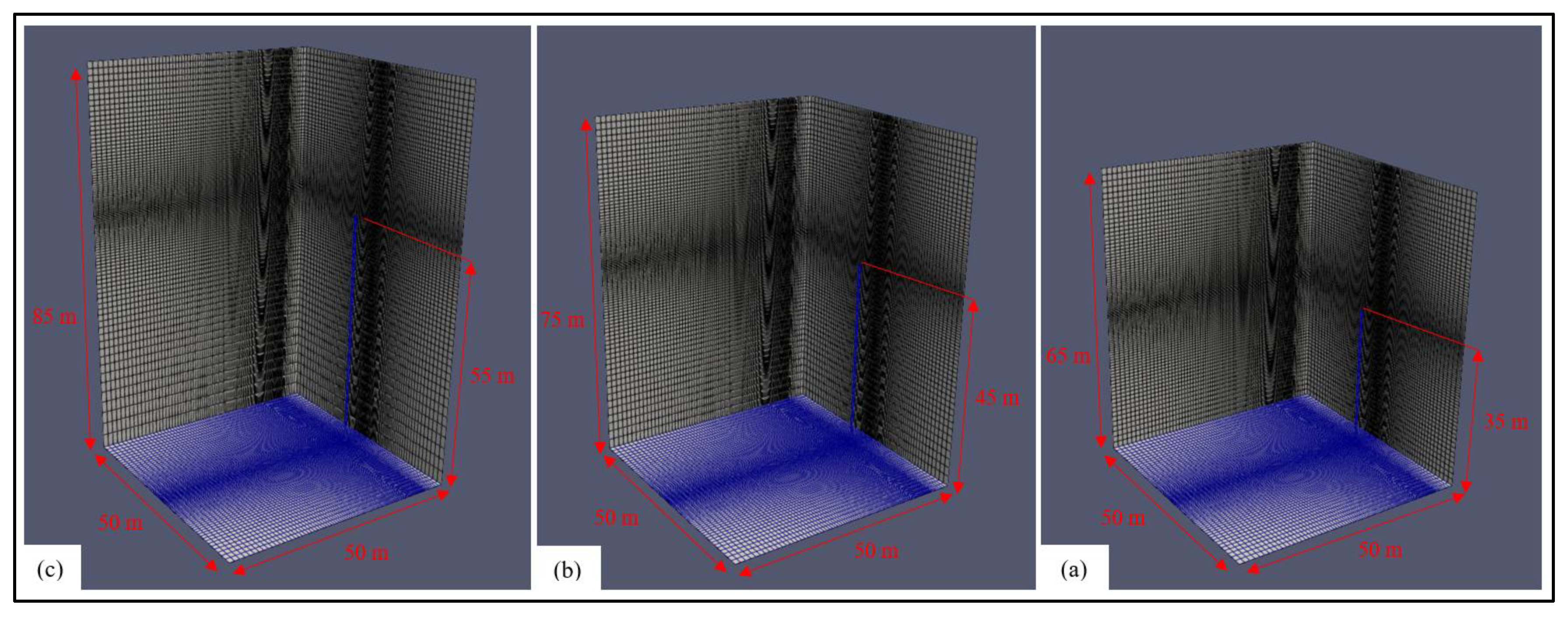

2.4. Computational Domain and Flare Model

Three different computational domain sizes were used to simulate various cases with different stack heights at both low and high gas firing rates. The first domain size had dimensions of 65 m in height, 50 m in length, and 50 m in width, and was used for a stack with a height of 35 m and a diameter of 0.61 m. The second domain size was 75 m in height, 50 m in length, and 50 m in width, corresponding to a stack height of 45 m and the same stack diameter of 0.61 m. The third domain size was 85 m in height, 50 m in length, and 50 m in width, with a stack height of 55 m and a diameter of 0.61 m.

In all three cases, the computational domain's height (z-axis) extended from -0.1 m to 0 m, defining the ground level (dry sand) for the flare, and then from 0 m to the top of the domain. The domain's length (x-axis) ranged from -5 m to 45 m, and its width (y-axis) spanned from -25 m to 25 m. By positioning the x and y domains at -5 m and -25 m, the flare's center was strategically placed to ensure that the crosswind would blow from the x-axis. The flare model was constructed from carbon steel using a dedicated flare modeler.

This approach allowed for the simulation of various stack configurations and operational scenarios.

Figure 2 shows three computational domain sizes with corresponding mesh configurations used for the different simulation cases in this study. These domain sizes were selected to represent various operational scenarios, allowing for a detailed analysis of flare. Moreover,

Figure 3 illustrates the three flare stack heights within the domain, along with the mesh for both the stack and the ground. This figure provides a clear representation of the stack configurations and their relationship to the computational domain, highlighting the precision of the mesh distribution around key components to ensure accurate simulation results. The total number of hexahedral cells for the simulations varied depending on the stack height. In the case of the 35 m tall stack, there were

1,335,288 cells (138 × 118 × 82). For the 45 m tall stack, the number of cells increased to

1,498,128 (138 × 118 × 92), and for the 55 m tall stack, there were

1,660,968 cells (138 × 118 × 102). In all cases, the mesh was refined near the flare tip to accurately capture the flame shape and the transient nature of the flow. This finer mesh ensured that the complex interactions in the flame region were simulated with a high level of detail, improving the accuracy of the results.

2.5. Mesh Independence Study

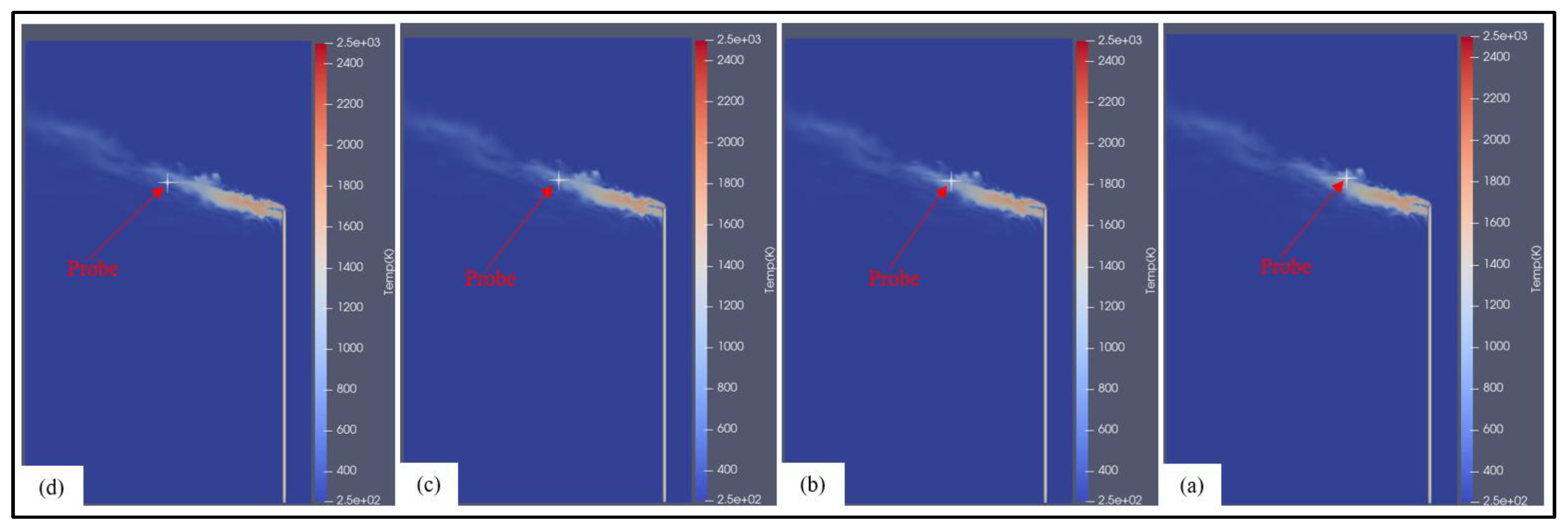

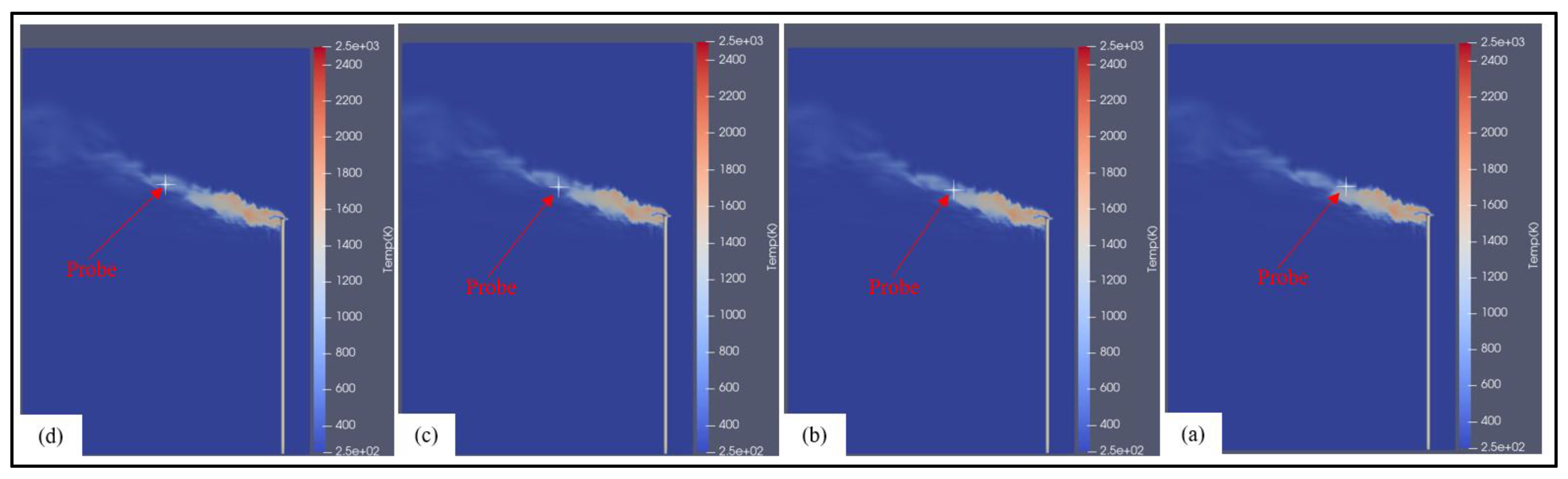

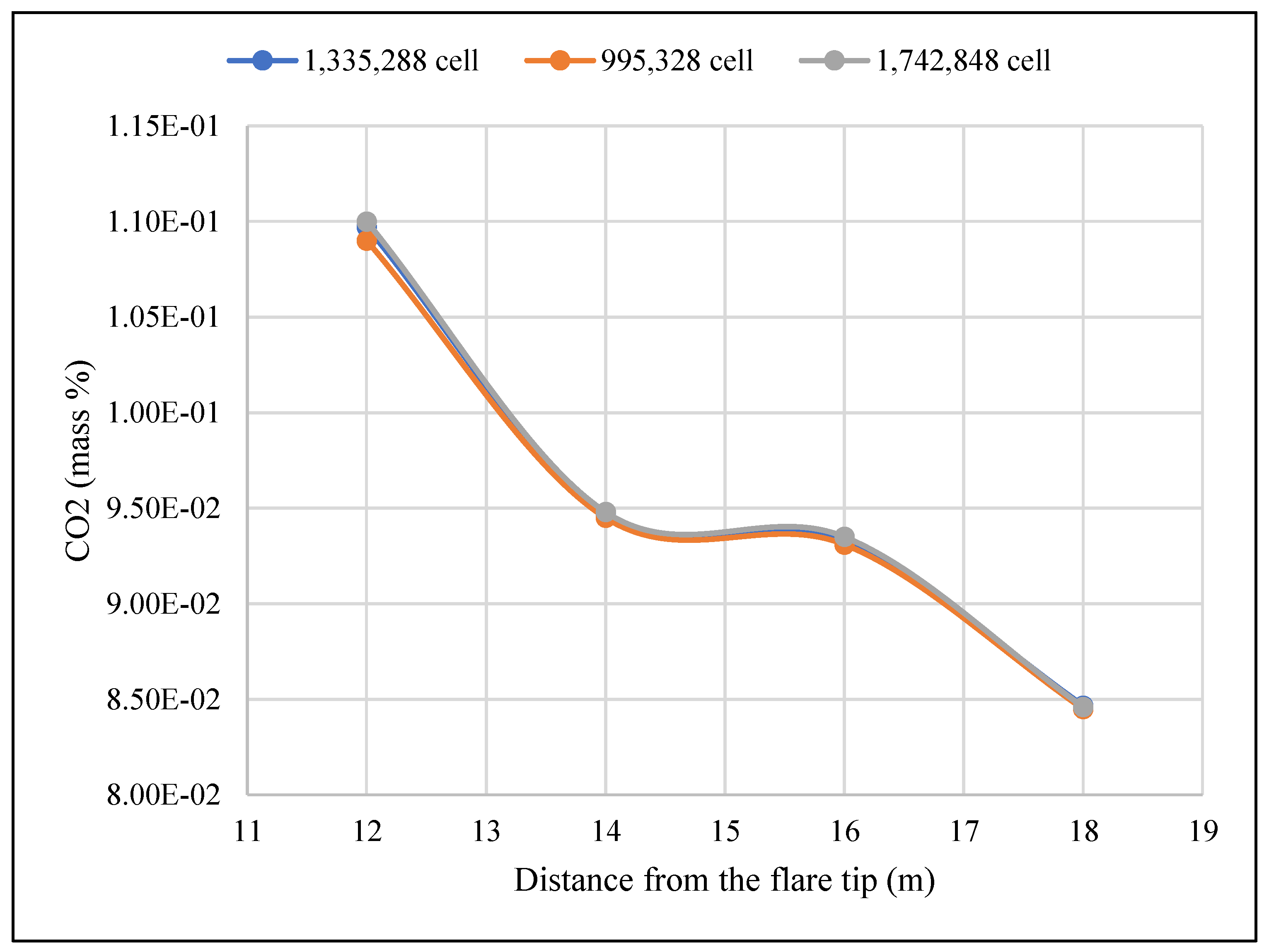

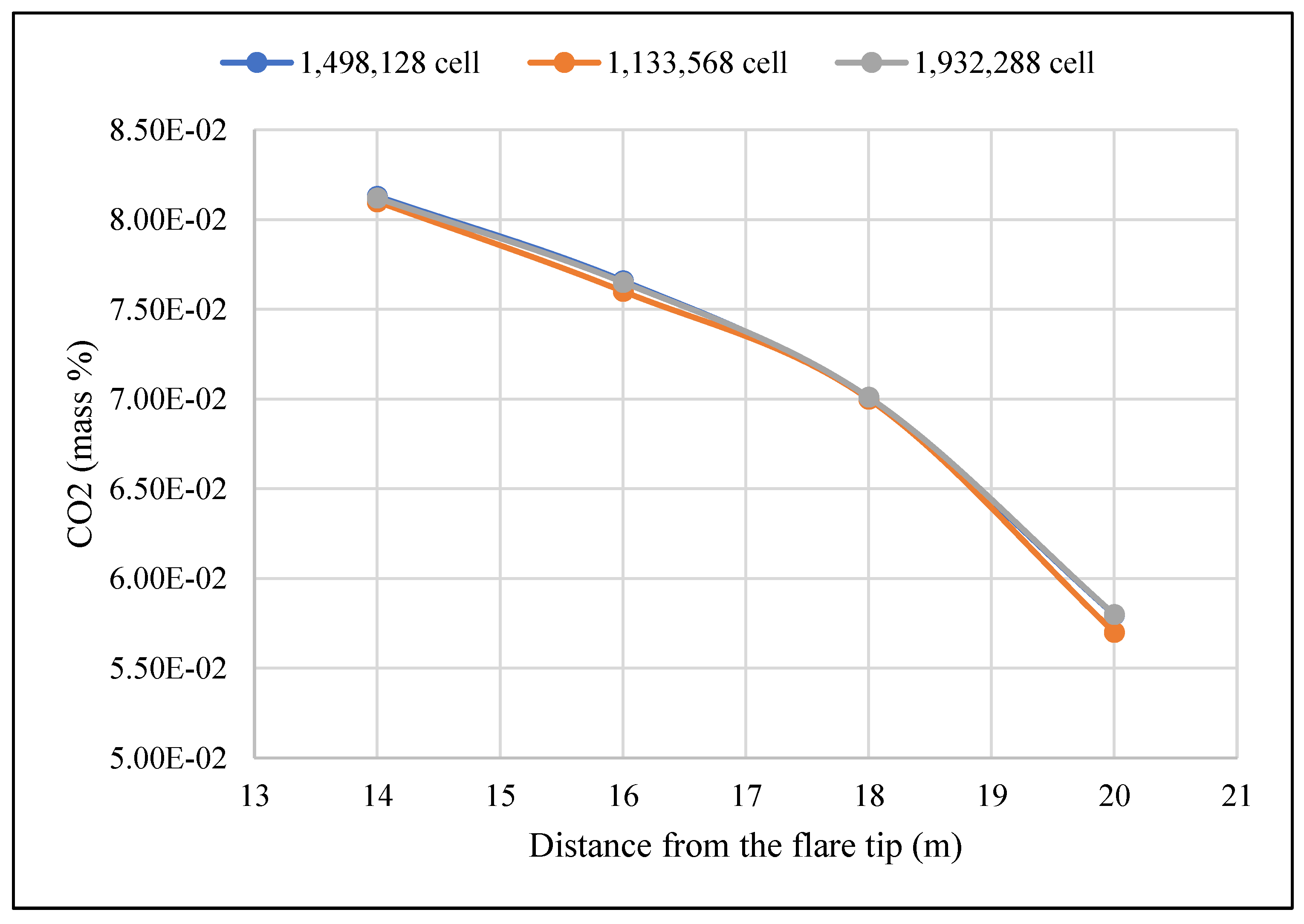

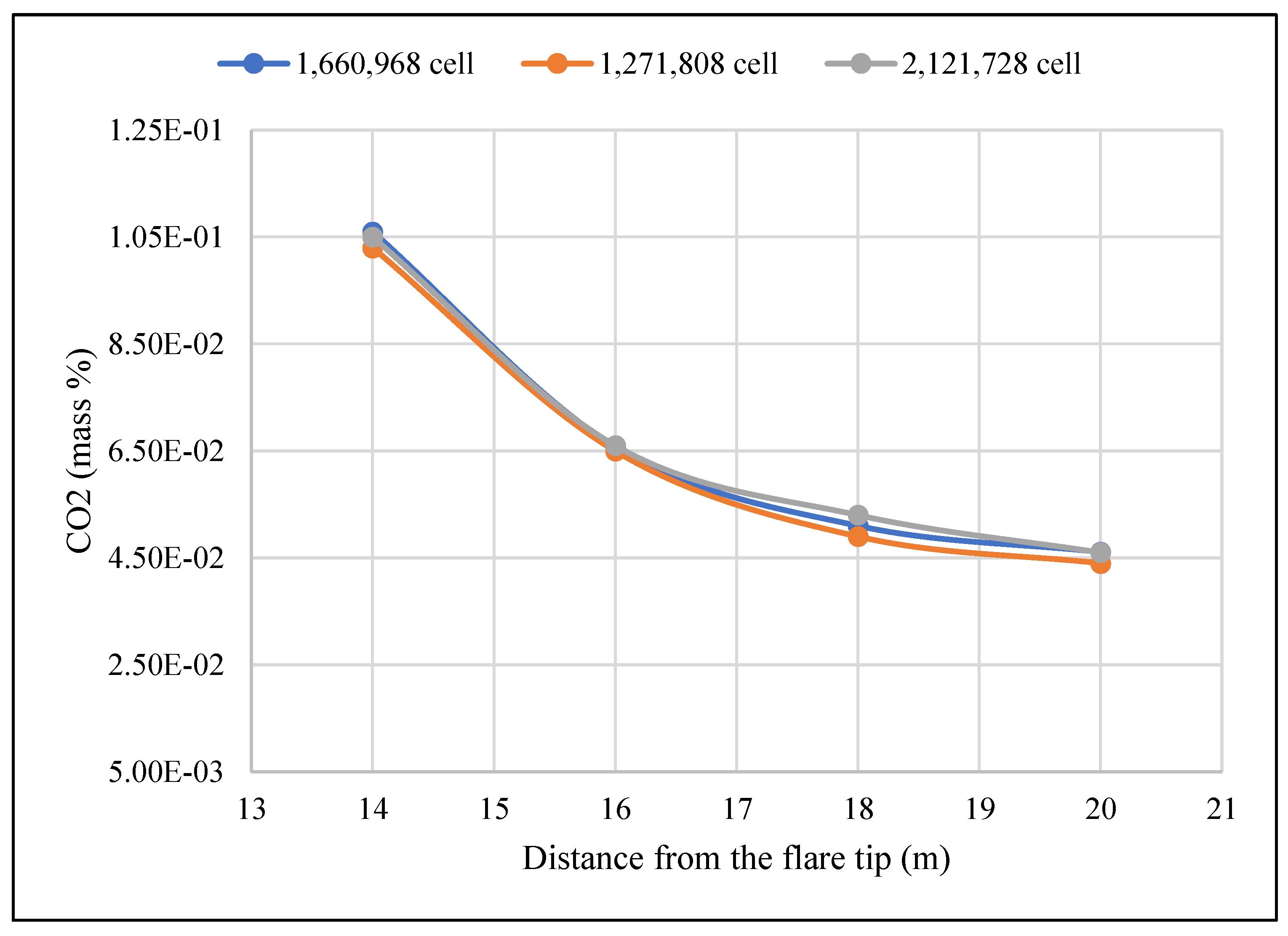

A mesh independence study was conducted by monitoring the change in carbon dioxide emissions during a 9 t/hr gas firing operation. Since three different stack heights (35 m, 45 m, and 55 m) with corresponding domain sizes were applied in this study, a separate mesh independence analysis was performed for each case. For each stack height, two different mesh configurations were tested: one with a lower cell number and another with a higher cell number.

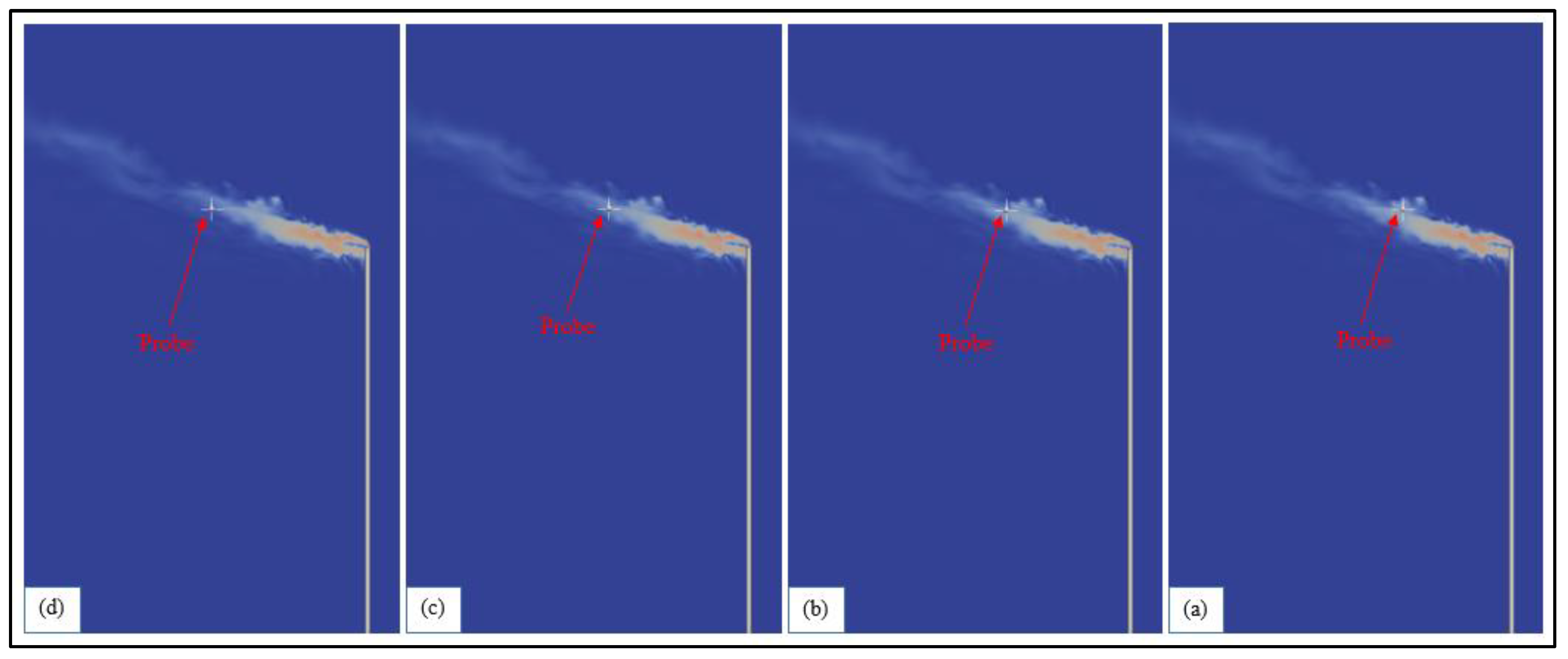

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the specified probe locations used to monitor the carbon dioxide

emissions in the plume during the mesh independence study. The probe used in this study had a radius of

0.3 m and was employed to record

10 datasets for each monitoring location. The average of these datasets was then calculated and used in the analysis.

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the results of the mesh independence study for the

35 m stack height,

45 m stack height, and

55 m stack height cases, respectively. According to these figures, there is a slight difference in the carbon dioxide mass fraction between the lower and higher cell numbers for each case. This indicates that the mesh refinement has a minimal effect on the results, demonstrating mesh independence. Therefore, the chosen mesh configurations

1,335,288 cells for the

35 m stack height,

1,498,128 cells for the

45 m stack height, and

1,660,968 cells for the

55 m stack height were deemed appropriate for the simulations, as they provide reliable and consistent results.

2.6. Boundary Conditions

The boundary conditions implemented in this work included three crosswind cases with speeds of 4 m/s, 8 m/s, and 14 m/s at a temperature of 300 K, flowing from the x-axis toward the flare. Hydrostatic pressure was defined throughout the computational domain to ensure accurate simulation of pressure variations. To model the specific components of the flare system, three one-dimensional subgrids were established: one for the ground, one for the flare wall, and one for the flare tip. In the ground subgrid, dry sand was selected as the material, representing the ground beneath the flare. In the flare wall subgrid, carbon steel was chosen as the material for the flare stack, reflecting the typical construction material for such systems.

For the flare tip subgrid, the mass flux and temperature of the gas were specified for both low and high gas firing rates. The mass flux values were 8.4 kg/m².s (equivalent to 9 t/hr or 2.5 kg/s) at the low gas firing rate, and 42 kg/m².s (equivalent to 45 t/hr or 12.5 kg/s) at the high gas firing rate, with the gas temperature maintained at 300 K. Finally, the flare exit was defined as a three-dimensional pressure outlet, ensuring proper representation of gas flow and pressure conditions at the flare tip.

2.7. Post Processing and Transient Calculation

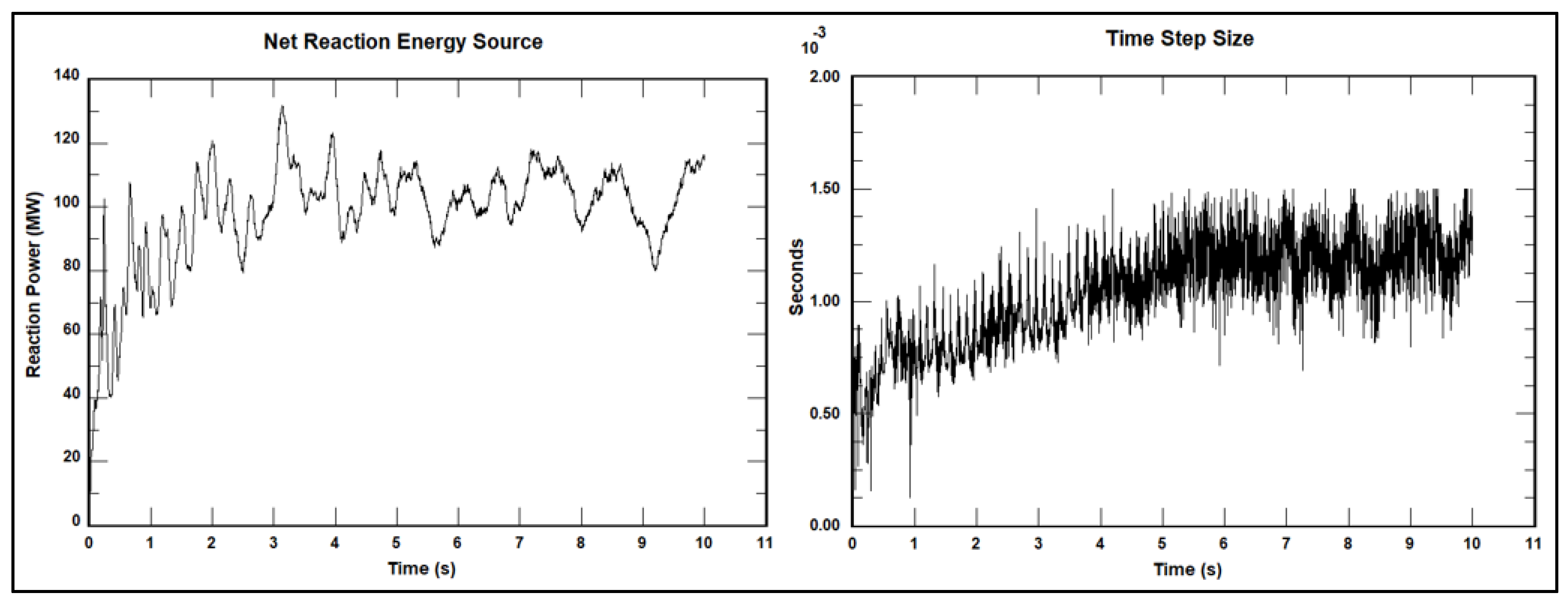

Initially, the simulation ran for 100 timesteps to calibrate the gas mass flow rate injected through the flare in all cases, which was set to 2.5 kg/s and 12.5 kg/s. This initial phase allowed the system to adjust and ensure accurate gas flow representation. Following the calibration, the simulation parameters were adjusted, with the timestep set to 1,000,000 and the total simulation time extended to 10 seconds. This longer duration was necessary to allow the system to stabilize and accurately reflect the operational characteristics of the flare under the specified conditions.

To check the simulation stability and validate the gas firing rate, the

net reaction energy source was used in all simulation cases. The net reaction energy source consists of reaction power (MW), which changes with time. This power can be calculated for each case by multiplying the gas flow rate (kg/s) by the

LHV of the gas (MJ/kg). For instance, in the case of a

2.5 kg/s gas firing rate, the reaction power is approximately

113 MW, calculated as 2.5 kg/s times 45 MJ/kg. Similarly, for the

12.5 kg/s gas firing rate, the reaction power is approximately

563 MW, calculated as 12.5 kg/s times 45 MJ/kg. At the start of the simulation, the initial combustion of a significant amount of gas causes a small peak in the reaction power curve. However, after a few seconds, this value drops and stabilizes, indicating that the simulation has reached a steady state.

Figure 10 shows net reaction energy source and time step size for 2.5 gas firing rate cases, while

Figure 11 displays the net reaction energy source and simulation time step size for 12.5 kg/s gas firing cases.

Figure 1.

Typical gas flare system [

3].

Figure 1.

Typical gas flare system [

3].

Figure 2.

Computational size and mesh; (a) 65 m (z-axis), 50 m (x-axis) and 50 (y-axis), (b) 75 m (z-axis), 50 m (x-axis) and 50 (y-axis), (c) 85 m (z-axis), 50 m (x-axis) and 50 (y-axis). .

Figure 2.

Computational size and mesh; (a) 65 m (z-axis), 50 m (x-axis) and 50 (y-axis), (b) 75 m (z-axis), 50 m (x-axis) and 50 (y-axis), (c) 85 m (z-axis), 50 m (x-axis) and 50 (y-axis). .

Figure 3.

Flare model and ground mesh; (a) 35 m stack height, (b) 45 m stack height, (c) 55 m stack height.

Figure 3.

Flare model and ground mesh; (a) 35 m stack height, (b) 45 m stack height, (c) 55 m stack height.

Figure 4.

Data sampling locations for mesh independence study at 9 t/hr firing rate using stack height 55 m; (a) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (b) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (c) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (d) 20 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis).

Figure 4.

Data sampling locations for mesh independence study at 9 t/hr firing rate using stack height 55 m; (a) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (b) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (c) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (d) 20 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis).

Figure 5.

Data sampling locations for mesh independence study at 9 t/hr firing rate using stack height 45 m; (a) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 50 m (z-axis), (b) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 50 m (z-axis), (c) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 50 m (z-axis), (d) 20 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 51 m (z-axis).

Figure 5.

Data sampling locations for mesh independence study at 9 t/hr firing rate using stack height 45 m; (a) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 50 m (z-axis), (b) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 50 m (z-axis), (c) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 50 m (z-axis), (d) 20 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 51 m (z-axis).

Figure 6.

Data sampling locations for mesh independence study at 9 t/hr firing rate using stack height 35 m; (a) 12 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis), (b) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis), (c) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis), (d) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis).

Figure 6.

Data sampling locations for mesh independence study at 9 t/hr firing rate using stack height 35 m; (a) 12 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis), (b) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis), (c) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis), (d) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 40 m (z-axis).

Figure 7.

Mesh independence study for 35 m tall stack case at 9 t/hr firing rate and 8 m/s crosswind.

Figure 7.

Mesh independence study for 35 m tall stack case at 9 t/hr firing rate and 8 m/s crosswind.

Figure 8.

Mesh independence study for 45 m tall stack case at 9 t/hr firing rate and 8 m/s crosswind.

Figure 8.

Mesh independence study for 45 m tall stack case at 9 t/hr firing rate and 8 m/s crosswind.

Figure 9.

Mesh independence study for 55 m tall stack case at 9 t/hr firing rate and 8 m/s crosswind.

Figure 9.

Mesh independence study for 55 m tall stack case at 9 t/hr firing rate and 8 m/s crosswind.

Figure 10.

Net reaction energy source and simulation time step size for 2.5 kg/s gas firing rate cases.

Figure 10.

Net reaction energy source and simulation time step size for 2.5 kg/s gas firing rate cases.

Figure 11.

Net reaction energy source and simulation time step size for 12.5 kg/s gas firing rate cases.

Figure 11.

Net reaction energy source and simulation time step size for 12.5 kg/s gas firing rate cases.

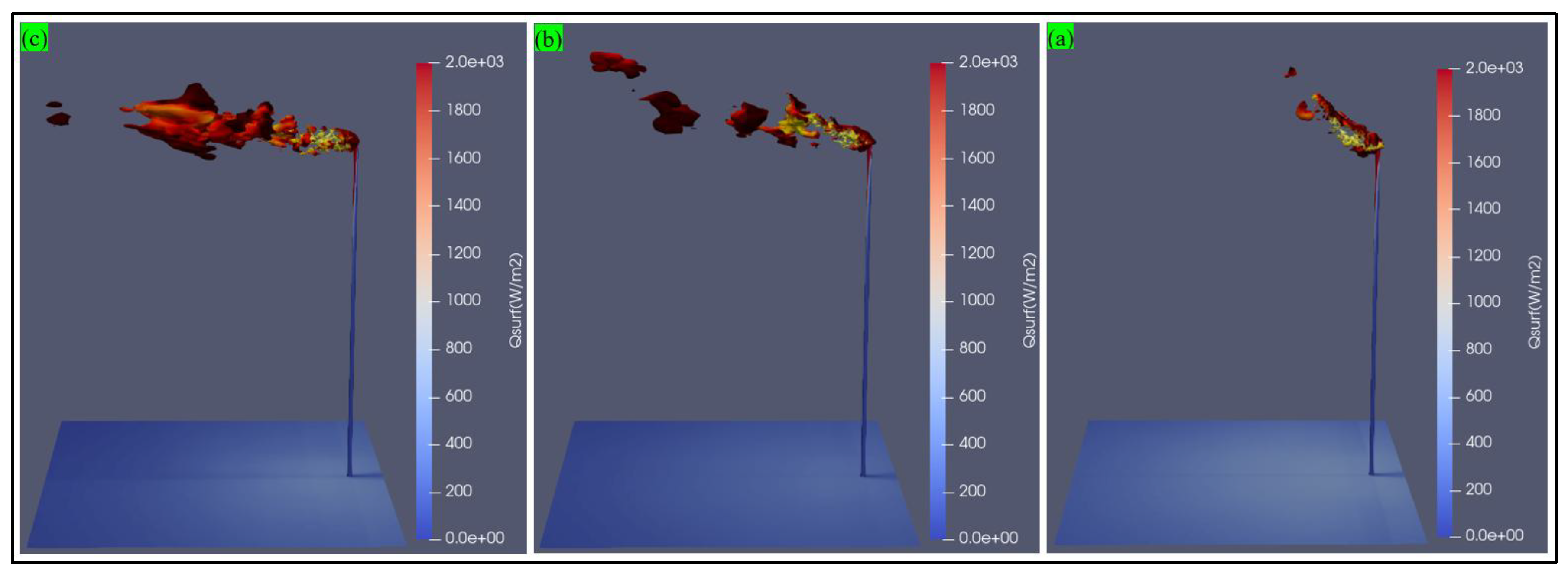

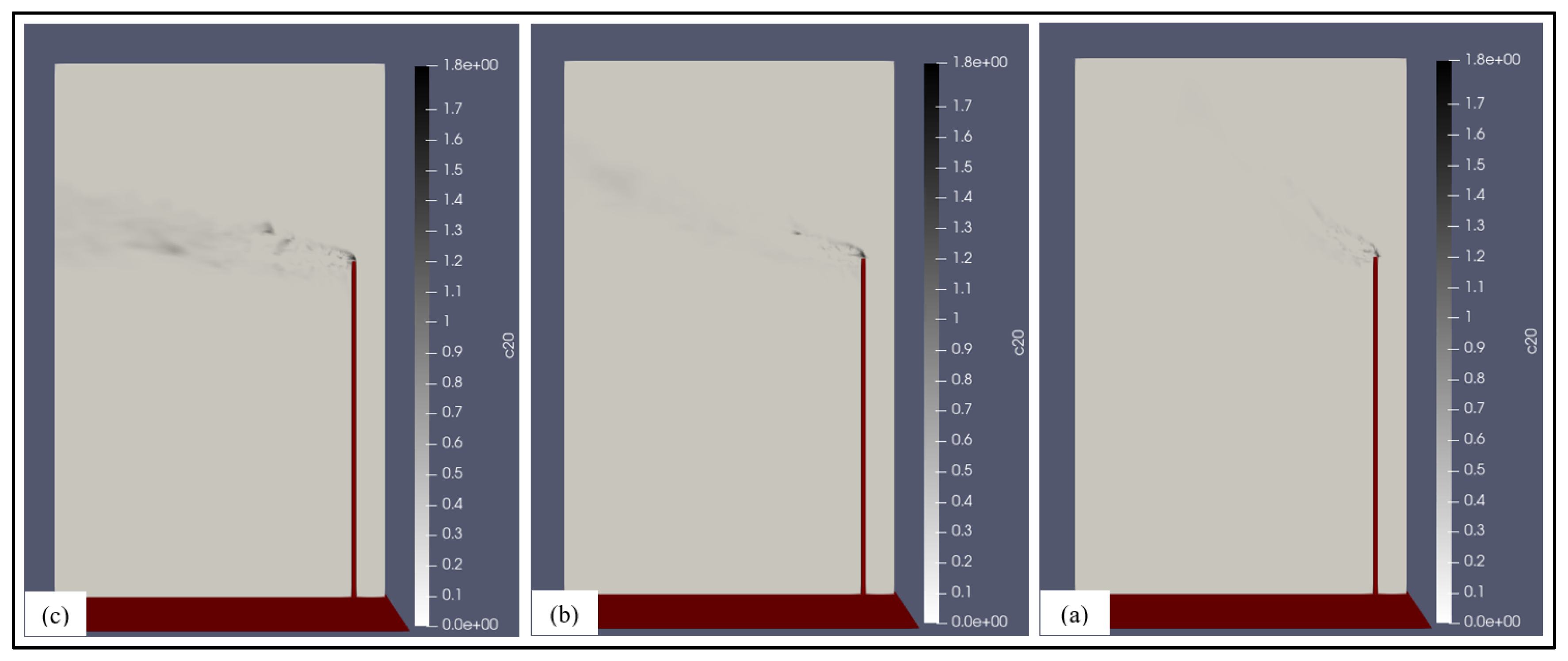

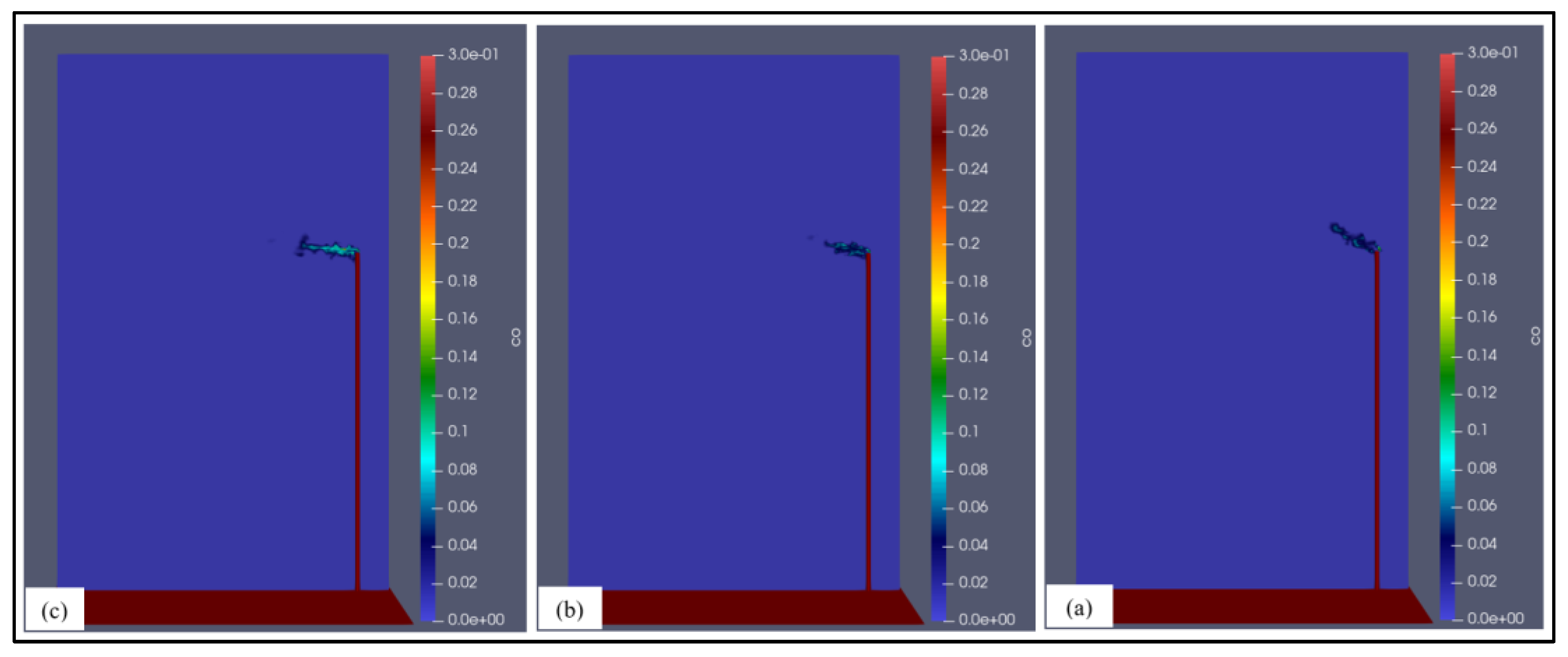

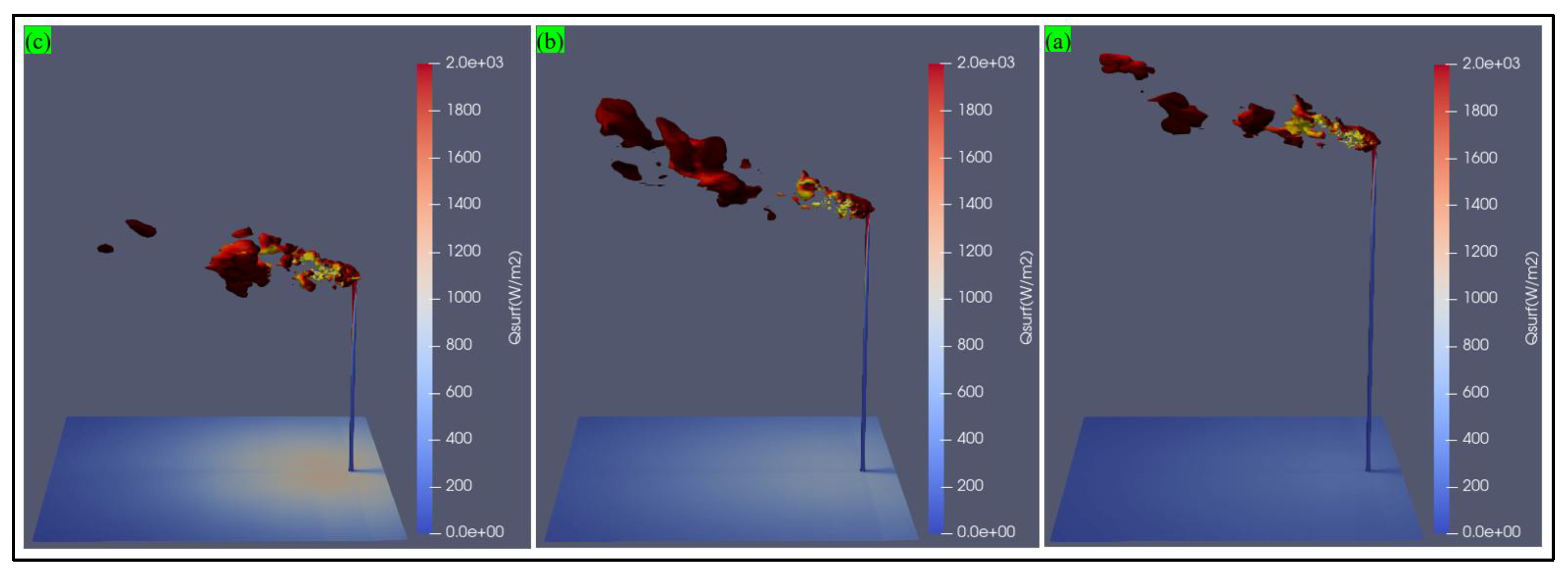

Figure 12.

Low gas firing rate flare operation under three different crosswind speeds: (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 12.

Low gas firing rate flare operation under three different crosswind speeds: (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

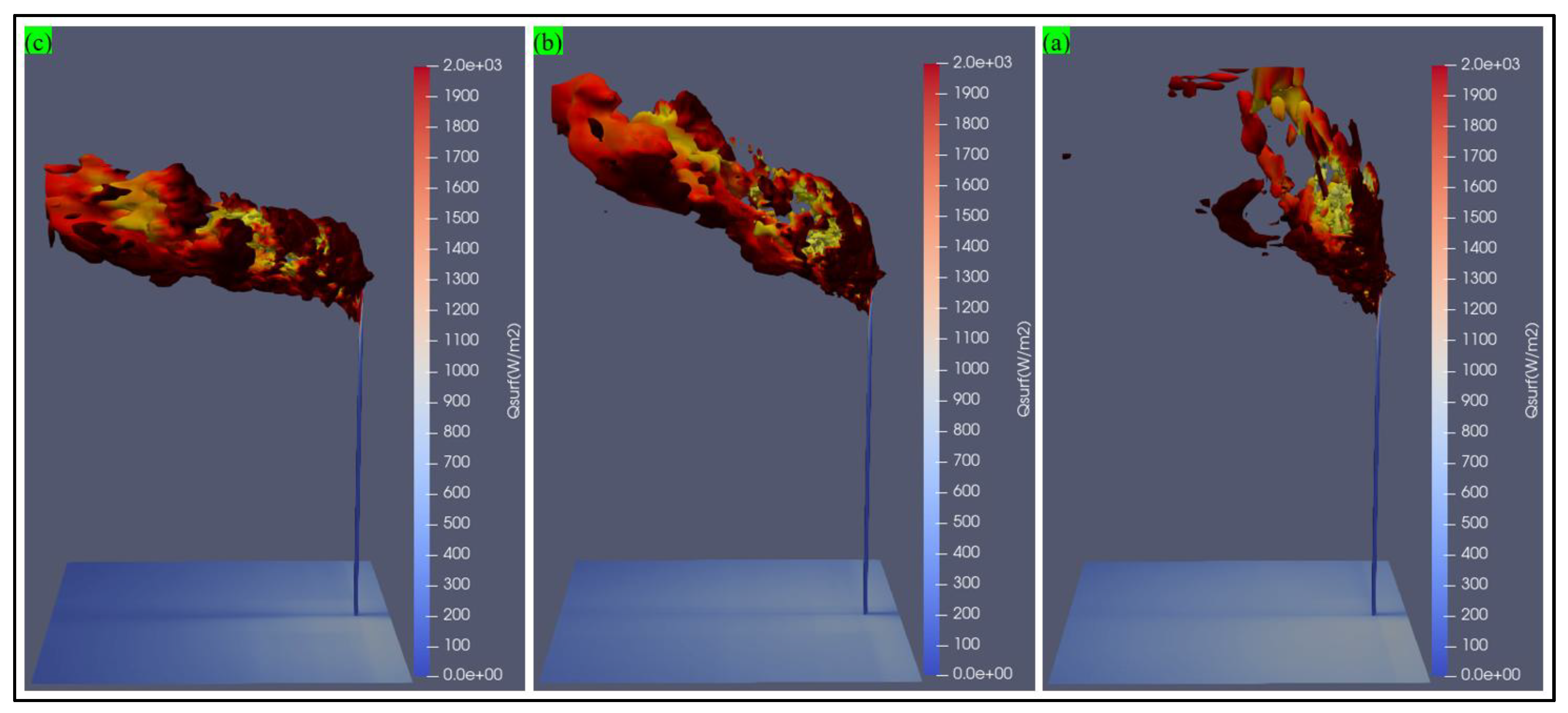

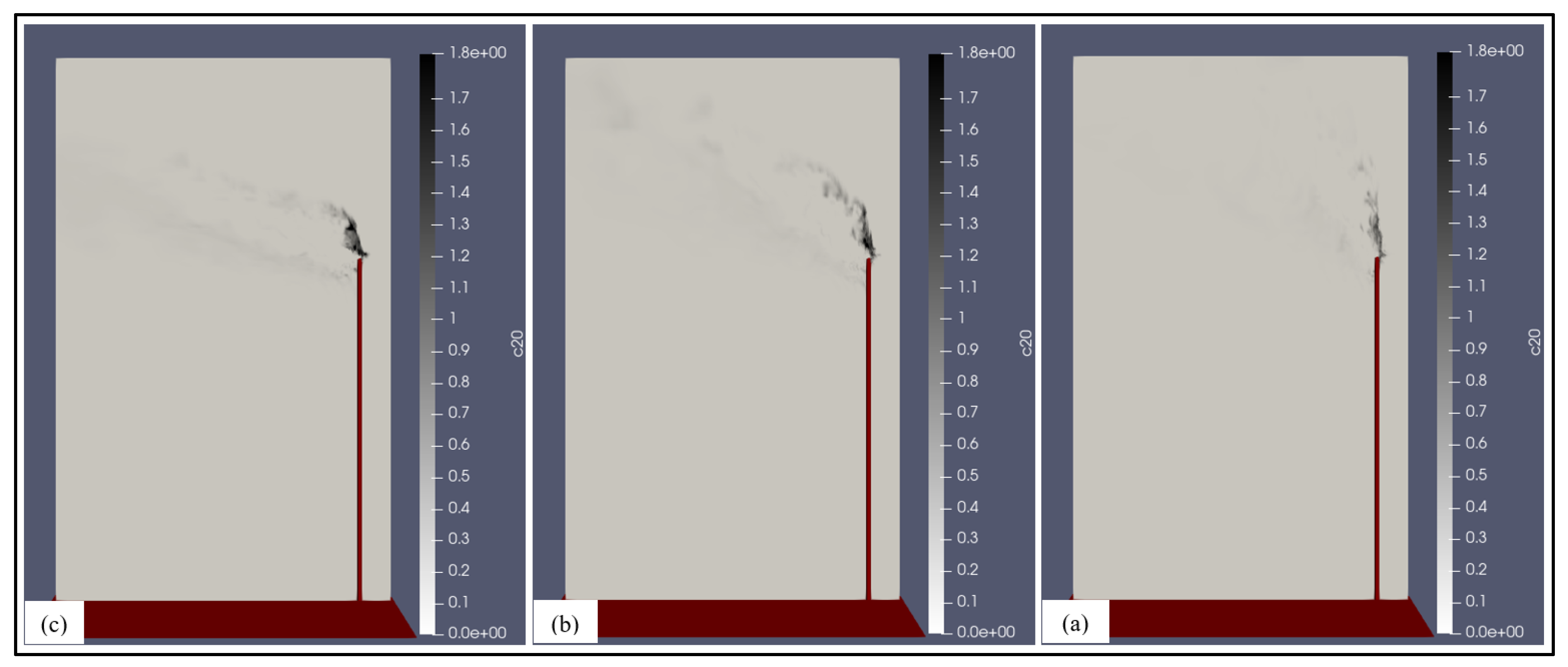

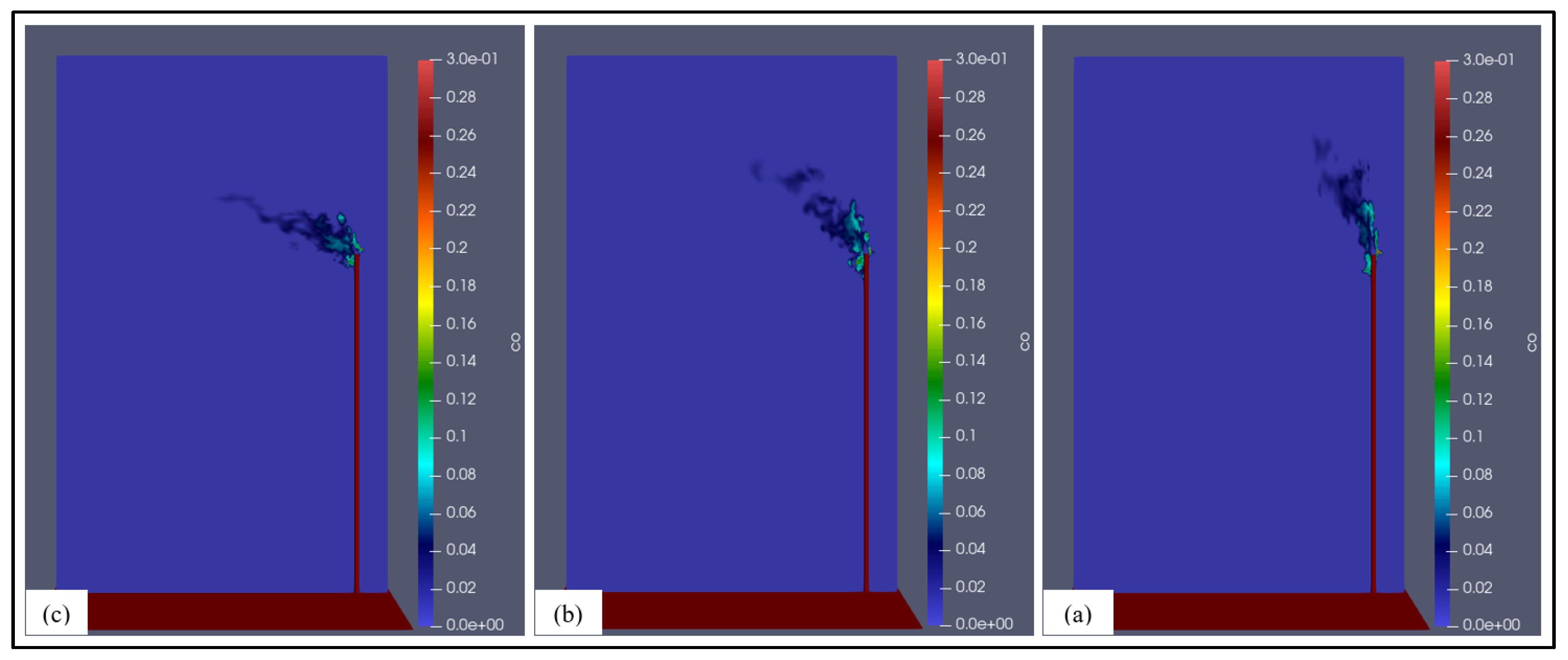

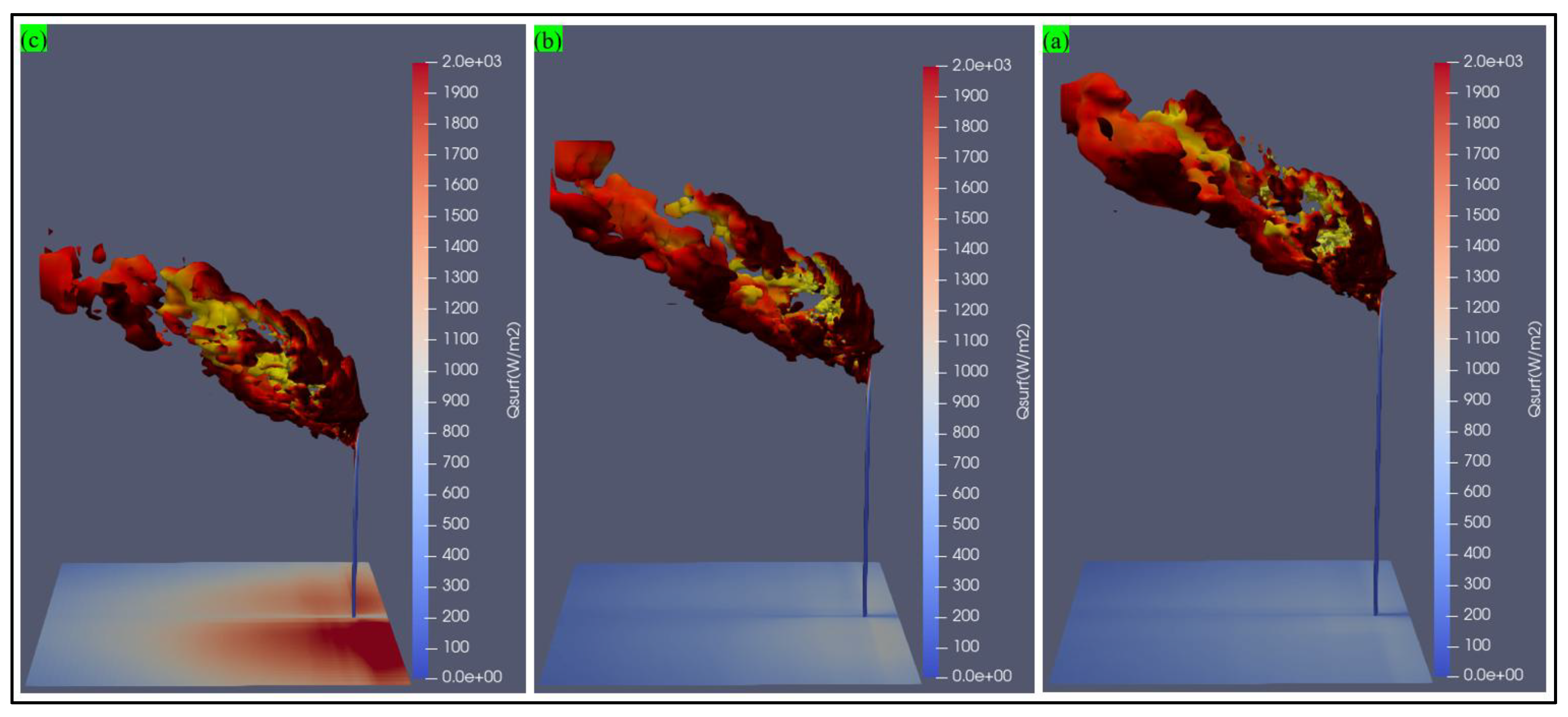

Figure 13.

High gas firing rate flare operation under three different crosswind speeds: (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 13.

High gas firing rate flare operation under three different crosswind speeds: (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

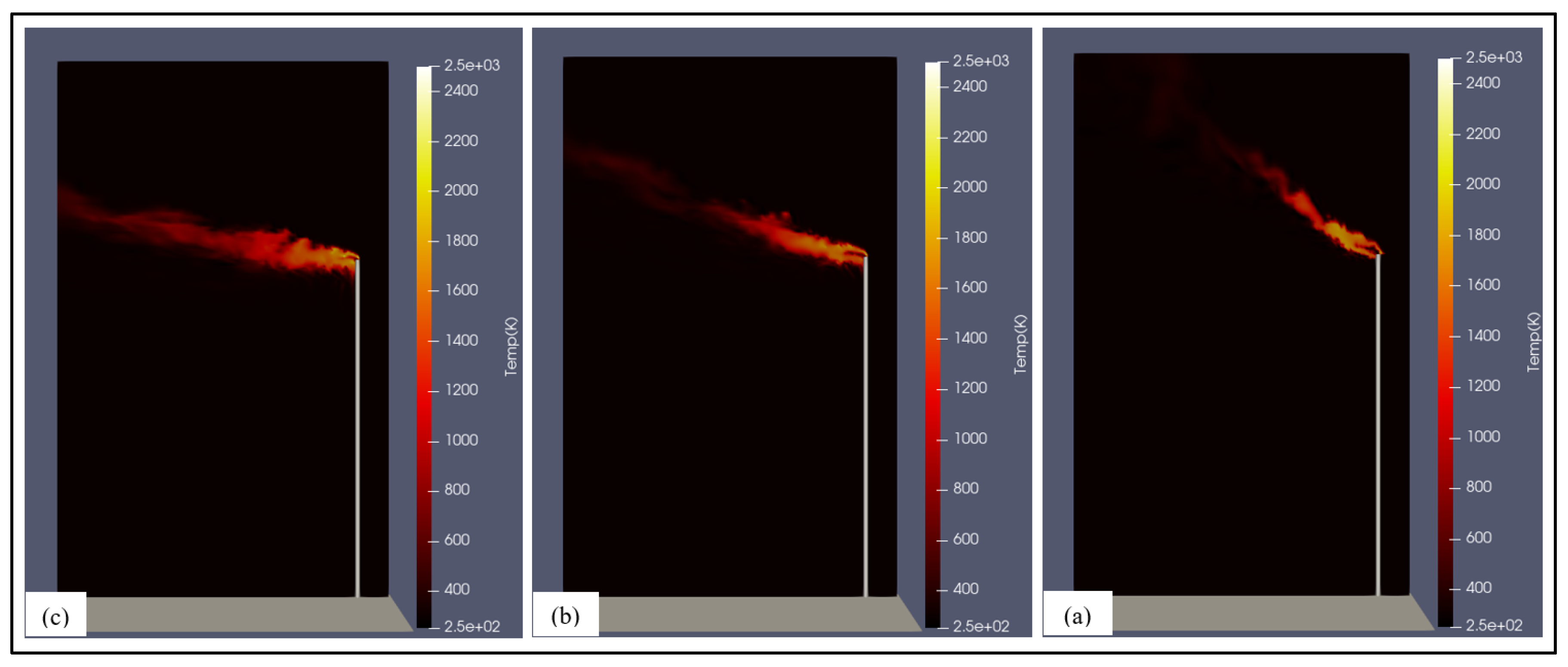

Figure 14.

Flame temperature at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 14.

Flame temperature at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

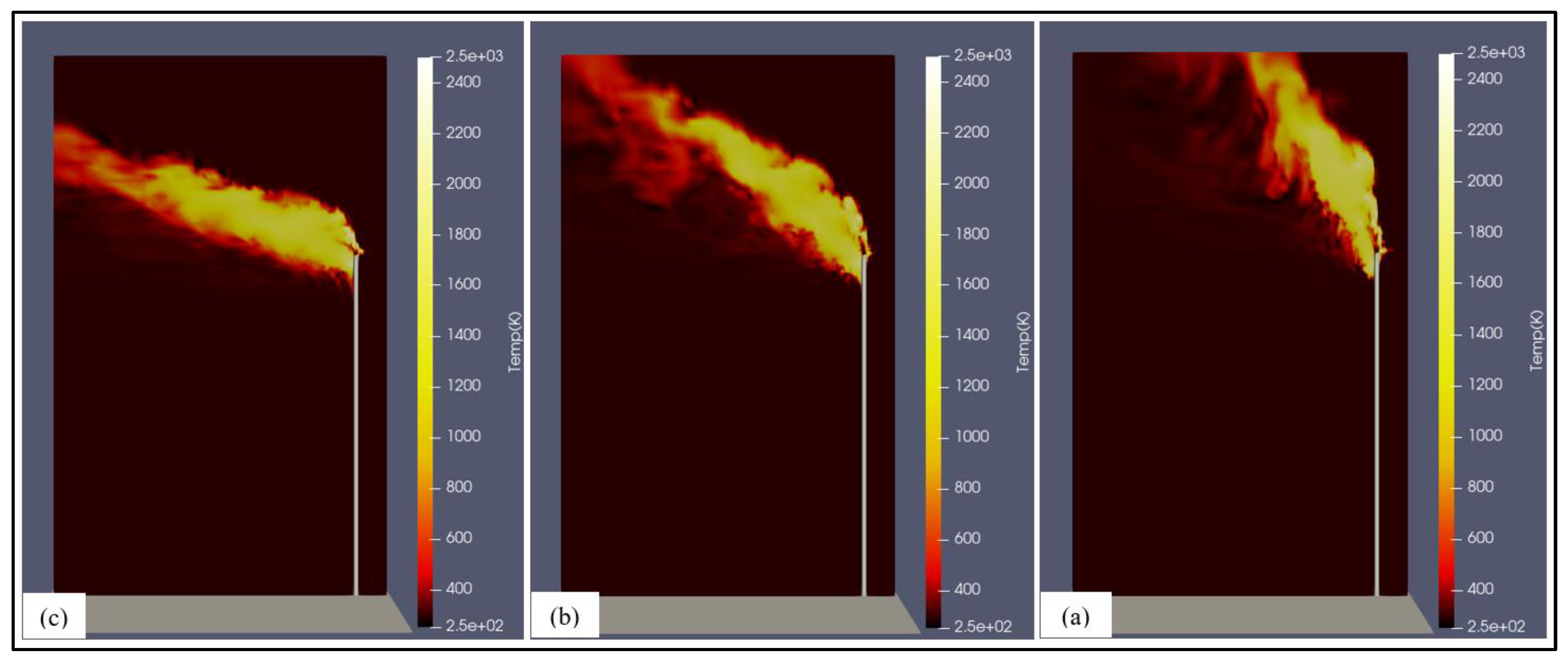

Figure 15.

Flame temperature at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 15.

Flame temperature at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 16.

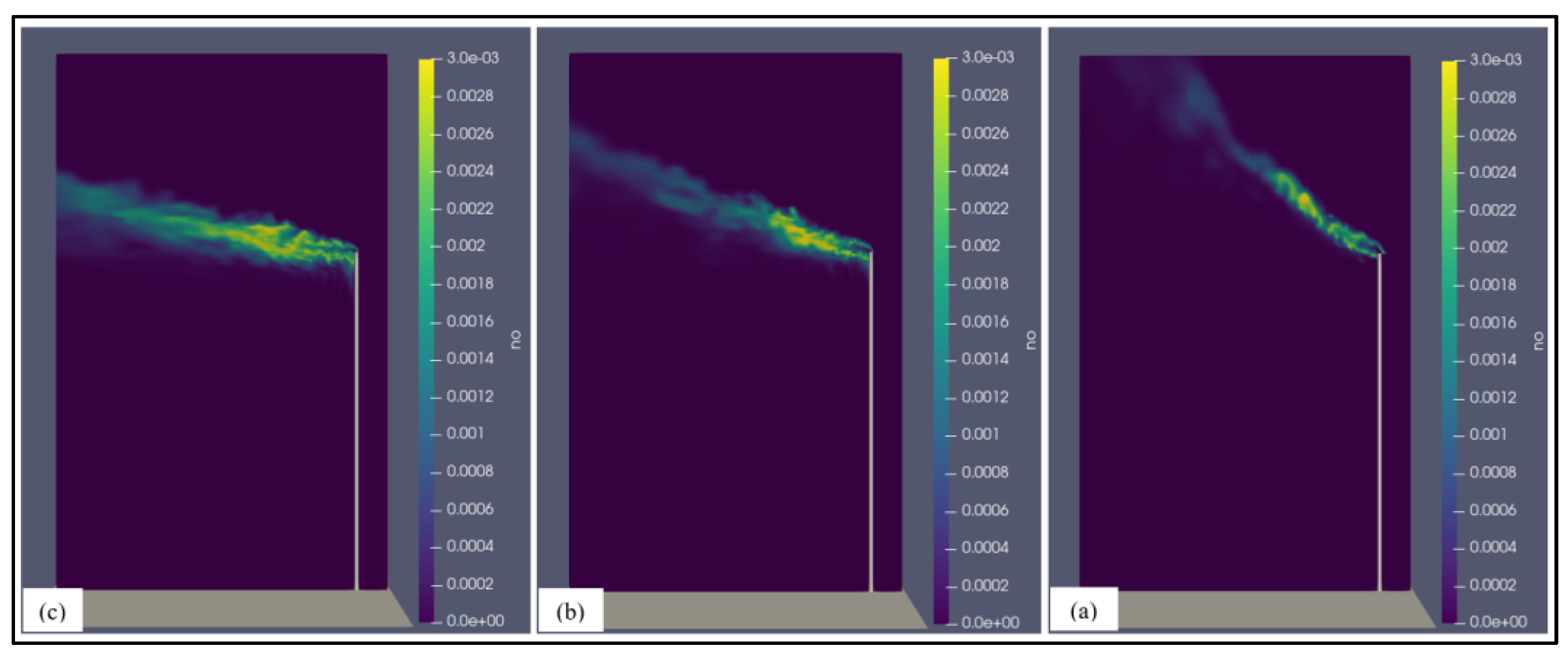

Soot formation at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 16.

Soot formation at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 17.

Soot formation at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 17.

Soot formation at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

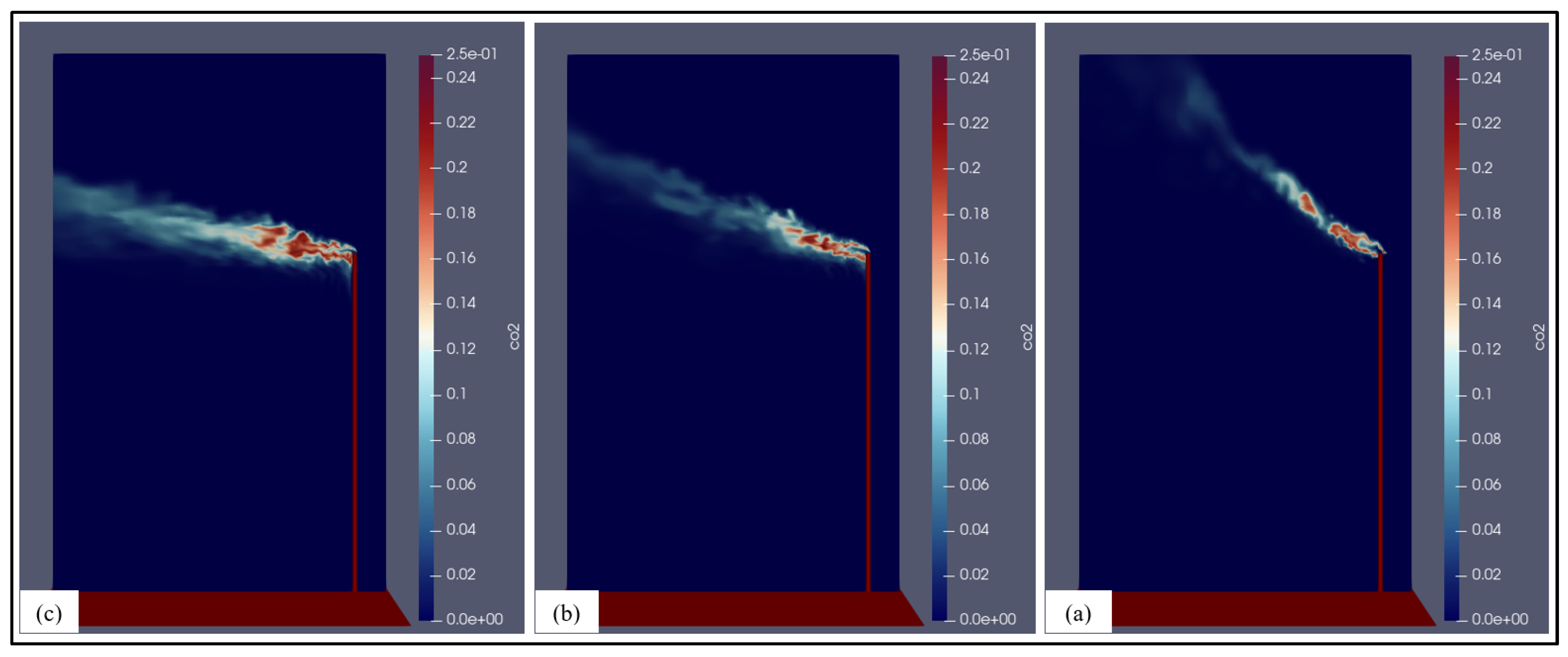

Figure 18.

Carbon dioxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 18.

Carbon dioxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

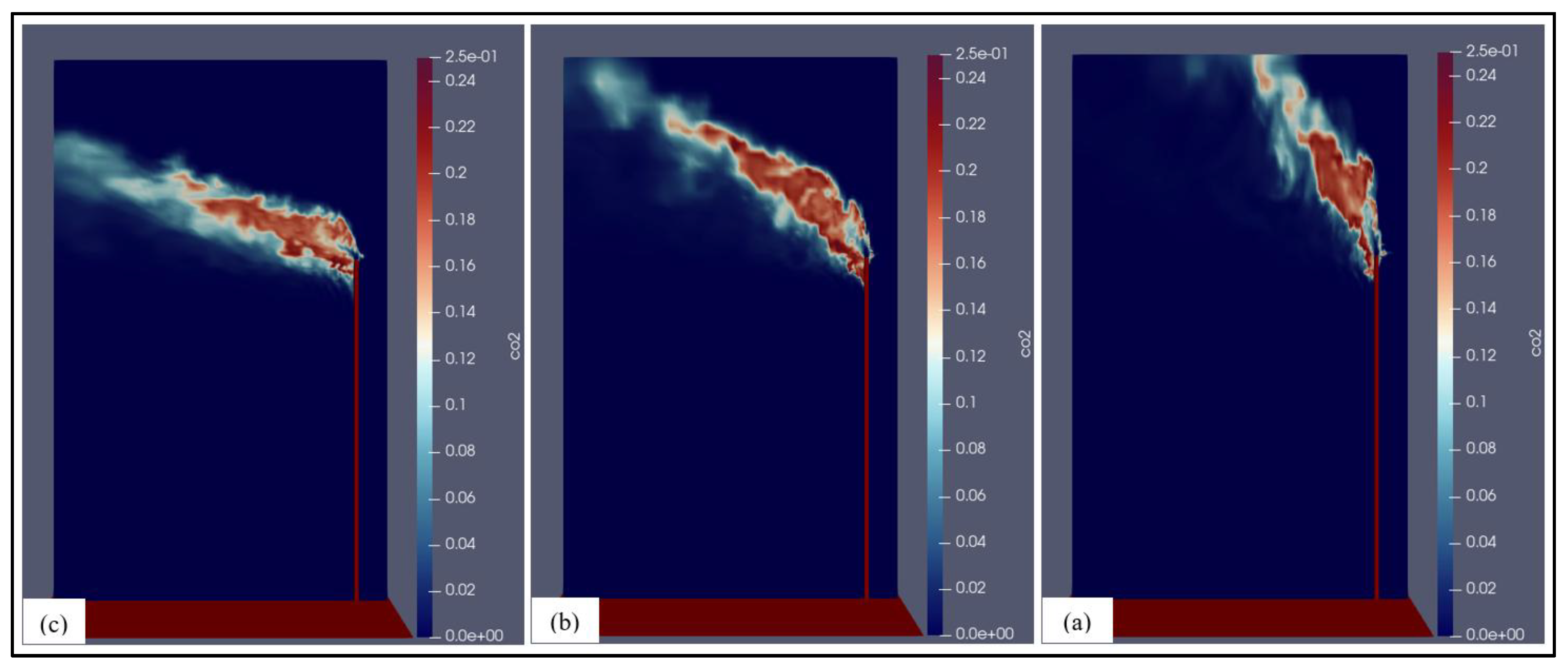

Figure 19.

Carbon dioxide emissions at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 19.

Carbon dioxide emissions at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 20.

Carbon monoxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 20.

Carbon monoxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 21.

Carbon monoxide emissions at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 21.

Carbon monoxide emissions at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

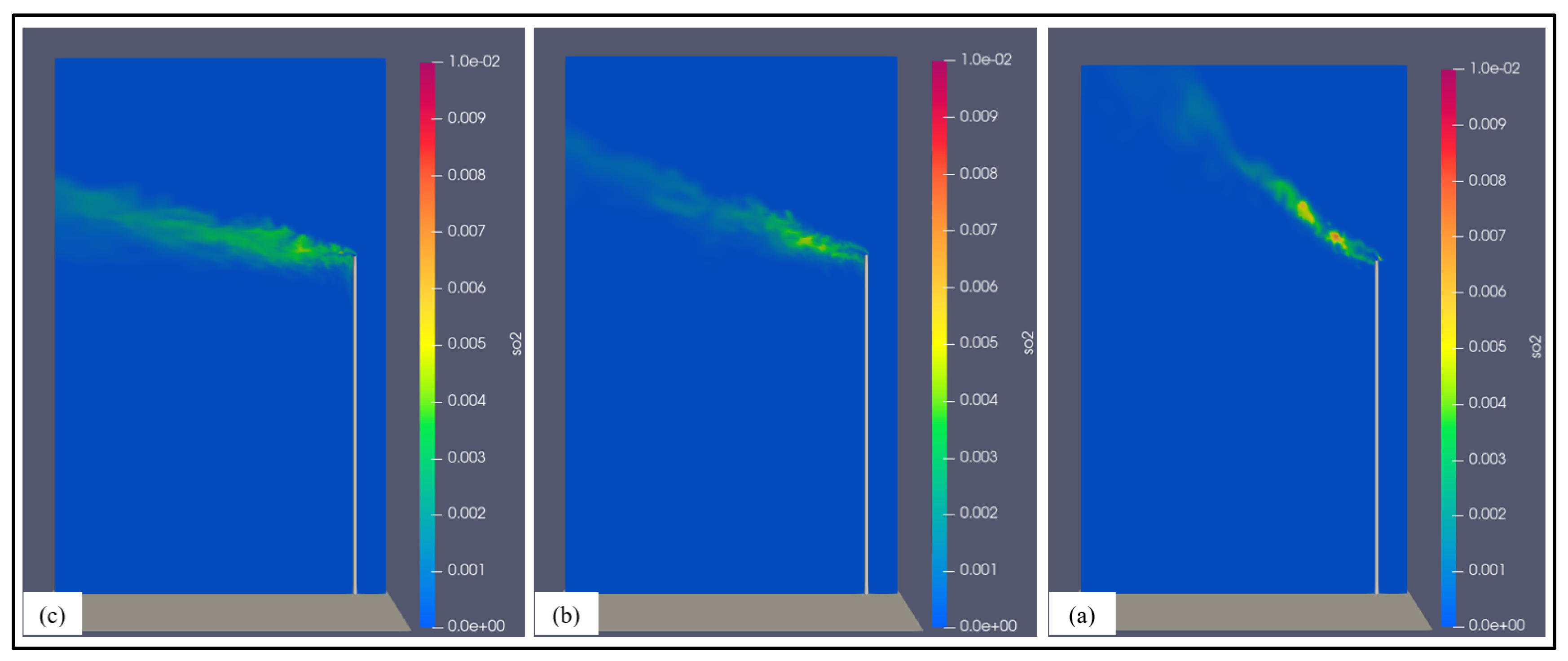

Figure 22.

Sulphur dioxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 22.

Sulphur dioxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

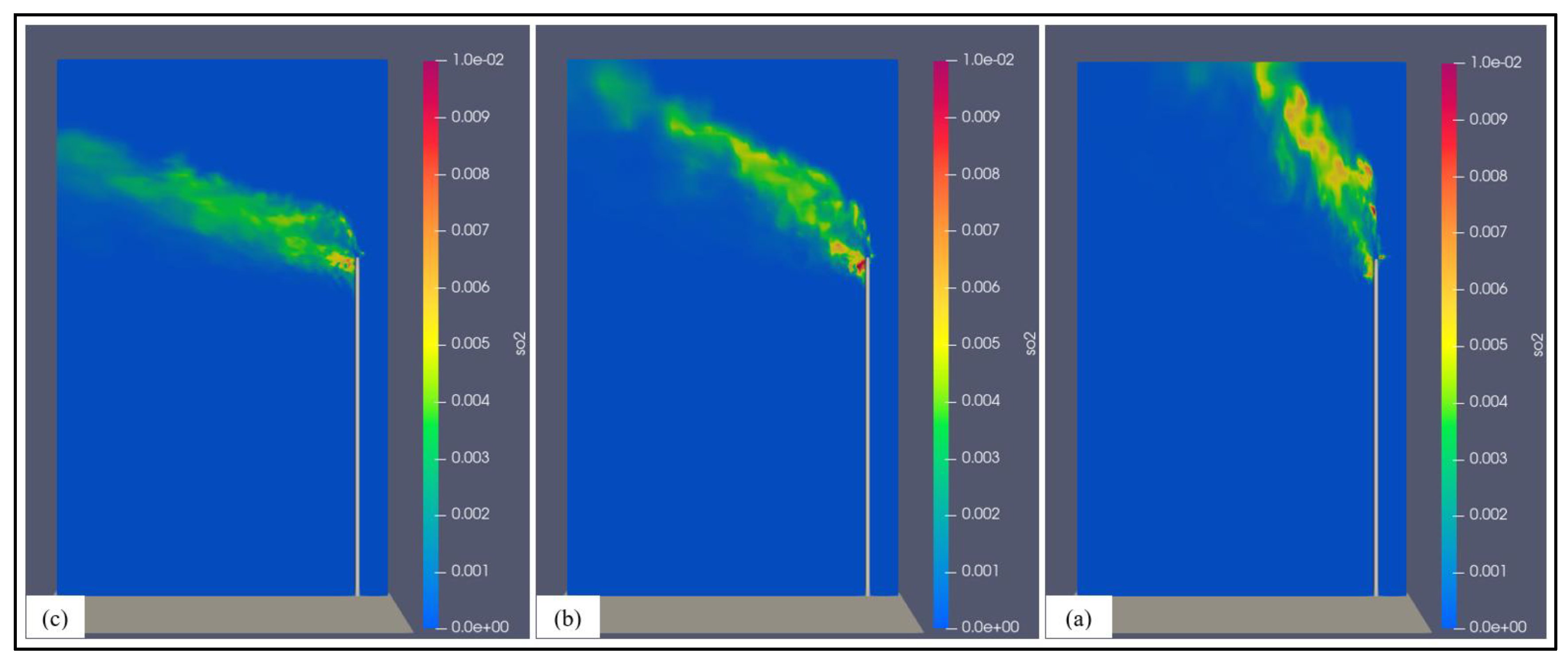

Figure 23.

Sulphur dioxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 23.

Sulphur dioxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 24.

Nitric oxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 24.

Nitric oxide emissions at a normal gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

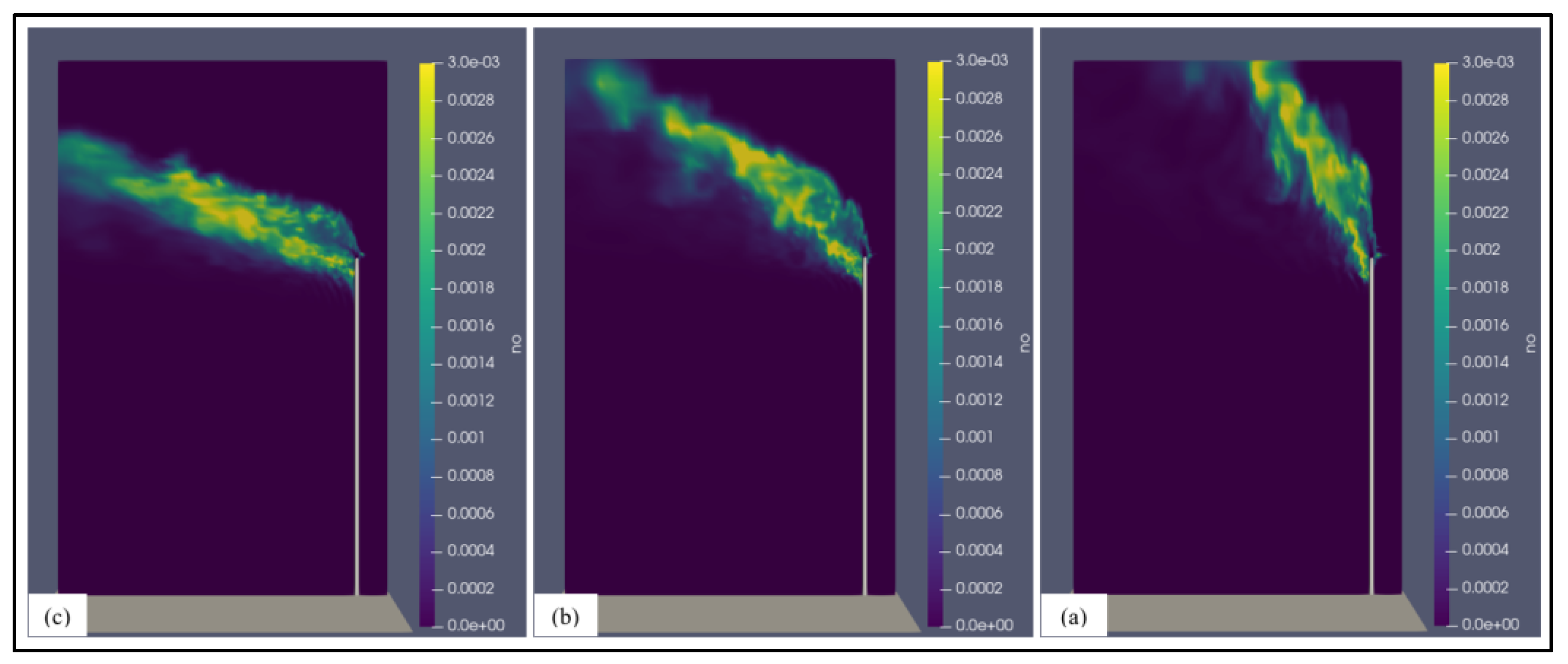

Figure 25.

Nitric oxide emissions at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 25.

Nitric oxide emissions at a high gas firing rate under different crosswind speed; (a) 4 m/s, (b) 8 m/s and (c) 14 m/s.

Figure 26.

Low gas firing rate flare operation using three different stack heights: (a) 55 m, (b) 45 m and (c) 35 m.

Figure 26.

Low gas firing rate flare operation using three different stack heights: (a) 55 m, (b) 45 m and (c) 35 m.

Figure 27.

High gas firing rate flare operation using three different stack heights: (a) 55 m, (b) 45 m and (c) 35 m.

Figure 27.

High gas firing rate flare operation using three different stack heights: (a) 55 m, (b) 45 m and (c) 35 m.

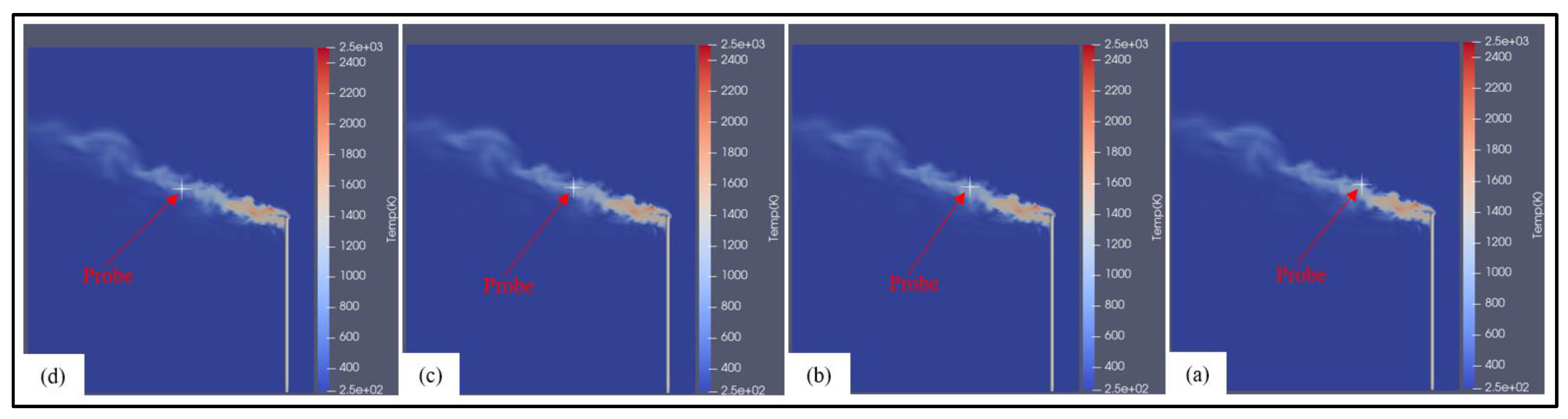

Figure 28.

Probe locations at normal gas firing rate of the flare using stack height of 55 m; (a) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (b) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (c) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (d) 20 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis)..

Figure 28.

Probe locations at normal gas firing rate of the flare using stack height of 55 m; (a) 14 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (b) 16 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (c) 18 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis), (d) 20 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 60 m (z-axis)..

Figure 29.

Probe locations at high gas firing rate of the flare using stack height 55 m; ; (a) 25 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 74 m (z-axis), (b) 27 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 74 m (z-axis), (c) 29 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 74 m (z-axis), (d) 30 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 75 m (z-axis)..

Figure 29.

Probe locations at high gas firing rate of the flare using stack height 55 m; ; (a) 25 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 74 m (z-axis), (b) 27 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 74 m (z-axis), (c) 29 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 74 m (z-axis), (d) 30 m (x-axis), 0 m (y-axis), 75 m (z-axis)..

Table 1.

Case study flared gas composition.

Table 1.

Case study flared gas composition.

| Basis = 100 kg mole |

|---|

| Components |

Mole (%) |

Mole (kg mole) |

MWt (kg/kg mole) |

Mass (kg) |

Mass (%) |

| CH4

|

16.44 |

16.44 |

16 |

263.0 |

0.074 |

| C2H6

|

8.80 |

8.80 |

30 |

264.0 |

0.074 |

| C3H8

|

12.5 |

12.5 |

44 |

550.0 |

0.155 |

| C4H10

|

20.35 |

20.35 |

58 |

1180.3 |

0.333 |

| C5H12

|

14.37 |

14.37 |

72 |

1034.6 |

0.292 |

| H2S |

2.96 |

2.96 |

34 |

100.6 |

0.028 |

| H2

|

20.58 |

20.58 |

2 |

41.2 |

0.012 |

| N2

|

4.00 |

4.00 |

28 |

112.0 |

0.032 |

| Total |

100 |

100.0 |

|

3545.8 |

1.00 |

Table 2.

Main combustion products at normal gas firing rate.

Table 2.

Main combustion products at normal gas firing rate.

| Probe Location |

CO (Mass%) |

CO2 (Mass%) |

Soot (Mass%) |

SO2 (Mass%) |

NO (Mass%) |

| x-axis (m) |

y-axis (m) |

z-axis (m) |

Radius (m) |

| 14 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

6.31E-09 |

1.06E-01 |

1.90E-04 |

2.49E-03 |

2.33E-03 |

| 16 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

3.26E-07 |

6.58E-02 |

9.90E-05 |

1.60E-03 |

1.47E-03 |

| 18 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

4.52E-09 |

5.10E-02 |

1.42E-04 |

1.22E-03 |

1.14E-03 |

| 20 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

1.28E-06 |

4.61E-02 |

2.51E-04 |

1.11E-03 |

1.02E-03 |

Table 3.

Main fuel compounds in the plume during normal gas firing rate.

Table 3.

Main fuel compounds in the plume during normal gas firing rate.

| Probe Location |

CH4 (Mass%) |

C2H6 (Mass%) |

C3H8 (Mass%) |

C4H10 (Mass%) |

C5H12 (Mass%) |

| x-axis (m) |

y-axis (m) |

z-axis (m) |

Radius (m) |

| 14 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

8.43E-09 |

7.42E-09 |

7.51E-09 |

7.63E-09 |

7.59E-09 |

| 16 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

7.83E-09 |

6.04E-09 |

6.14E-09 |

6.32E-09 |

6.31E-09 |

| 18 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

7.80E-09 |

5.30E-09 |

5.41E-09 |

5.62E-09 |

5.62E-09 |

| 20 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

6.96E-09 |

4.72E-09 |

4.83E-09 |

5.01E-09 |

5.00E-09 |

Table 4.

Main combustion products at high gas firing rate.

Table 4.

Main combustion products at high gas firing rate.

| Probe Location |

CO (Mass%) |

CO2 (Mass%) |

Soot (Mass%) |

SO2 (Mass%) |

NO (Mass%) |

| x-axis (m) |

y-axis (m) |

z-axis (m) |

Radius (m) |

| 25 |

0 |

74 |

0.3 |

1.45E-05 |

1.24E-01 |

1.76E-05 |

3.39E-03 |

2.39E-03 |

| 27 |

0 |

74 |

0.3 |

1.16E-08 |

1.38E-01 |

7.06E-05 |

3.91E-03 |

2.76E-03 |

| 29 |

0 |

74 |

0.3 |

2.66E-08 |

1.27E-01 |

3.82E-05 |

3.82E-03 |

2.67E-03 |

| 30 |

0 |

75 |

0.3 |

2.83E-07 |

7.78E-02 |

1.05E-04 |

2.27E-03 |

1.67E-03 |

Table 5.

Main fuel compounds in the plume during high gas firing rate.

Table 5.

Main fuel compounds in the plume during high gas firing rate.

| Probe Location |

CH4 (Mass%) |

C2H6 (Mass%) |

C3H8 (Mass%) |

C4H10 (Mass%) |

C5H12 (Mass%) |

| x-axis (m) |

y-axis (m) |

z-axis (m) |

Radius (m) |

| 25 |

0 |

74 |

0.3 |

7.59E-08 |

1.04E-06 |

1.61E-06 |

4.93E-06 |

4.38E-06 |

| 27 |

0 |

74 |

0.3 |

9.47E-09 |

9.60E-09 |

9.52E-09 |

9.83E-09 |

9.69E-09 |

| 29 |

0 |

74 |

0.3 |

9.06E-09 |

8.39E-09 |

8.44E-09 |

8.59E-09 |

8.68E-09 |

| 30 |

0 |

75 |

0.3 |

8.69E-09 |

6.29E-09 |

6.40E-09 |

6.60E-09 |

6.59E-09 |

Table 6.

Main flare gas compounds in the fuel and the plume during normal gas firing rate.

Table 6.

Main flare gas compounds in the fuel and the plume during normal gas firing rate.

| Plume |

|

|

|

|

|

| Probe Location |

CH4 (Mass%) |

C2H6 (Mass%) |

C3H8 (Mass%) |

C4H10 (Mass%) |

C5H12 (Mass%) |

| x-axis (m) |

y-axis (m) |

z-axis (m) |

Radius (m) |

| 14 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

8.43E-09 |

7.42E-09 |

7.51E-09 |

7.63E-09 |

7.59E-09 |

| 16 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

7.83E-09 |

6.04E-09 |

6.14E-09 |

6.32E-09 |

6.31E-09 |

| 18 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

7.80E-09 |

5.30E-09 |

5.41E-09 |

5.62E-09 |

5.62E-09 |

| 20 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

6.96E-09 |

4.72E-09 |

4.83E-09 |

5.01E-09 |

5.00E-09 |

| Fuel |

7.40E-02 |

7.40E-02 |

1.55E-01 |

3.33E-01 |

2.92E-01 |

Table 7.

Main flare gas compounds in the fuel and the plume during high gas firing rate.

Table 7.

Main flare gas compounds in the fuel and the plume during high gas firing rate.

| Plume |

|

|

|

|

|

| Probe Location |

CH4 (Mass%) |

C2H6 (Mass%) |

C3H8 (Mass%) |

C4H10 (Mass%) |

C5H12 (Mass%) |

| x-axis (m) |

y-axis (m) |

z-axis (m) |

Radius (m) |

| 14 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

7.59E-08 |

1.04E-06 |

1.61E-06 |

4.93E-06 |

4.38E-06 |

| 16 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

9.47E-09 |

9.60E-09 |

9.52E-09 |

9.83E-09 |

9.69E-09 |

| 18 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

9.06E-09 |

8.39E-09 |

8.44E-09 |

8.59E-09 |

8.68E-09 |

| 20 |

0 |

60 |

0.3 |

8.69E-09 |

6.29E-09 |

6.40E-09 |

6.60E-09 |

6.59E-09 |

| Fuel |

7.40E-02 |

7.40E-02 |

1.55E-01 |

3.33E-01 |

2.92E-01 |