1. Introduction

The world's most widely consumed alcoholic beverage is beer [

1]. Mycotoxins present in beer pose a significant public health concern, especially for those who consume it in large amounts. [

2]. Beer production involves a range of processes that can either increase or decrease the initial levels of mycotoxins. The intricate nature of these processes does not provide brewers with absolute control over the chemical and biochemical reactions occurring in each batch [

3]. However, it's important to note that the most effective measure to prevent mycotoxin accumulation remains the prevention of mold growth in raw materials.

The production of secondary metabolites by filamentous fungi, which have no biochemical significance for fungal development, produces naturally occurring compounds with a low molecular weight known as mycotoxins. When subjected to favorable conditions for mycotoxin synthesis, they generate a toxic environment capable of causing diseases in both animals and humans [

4]. The mycotoxins that have the greatest effect on both agro-economics and public health are aflatoxins (AFs), Ochratoxin A (OTA), Patulin (PAT), Trichothecenes (Deoxynivalenol DON, Nivalenol NIV, HT-2 toxin, T-2 toxin), Zearalenone (ZEN), Fumonisins (FUM), tremorgenic toxins, and ergot alkaloids [

3]. Genera like

Aspergillus (AFs, OTA, PAT),

Penicillium (OTA and PAT), and

Fusarium (DON, NIV, HT-2, T-2, ZEN) produce most of these mycotoxins [

5].

The contamination of food and feed industries with mycotoxin-producing fungi can result in the formation of mycotoxin. All of these commodities, including cereals, peanuts, milk, and dairy products, coffee, wine, beer, cottonseeds, fresh and dried fruits, vegetables, and nuts, are frequently contaminated [

6].

Along with water, hops, and yeast, barley is an essential ingredient when making beer. The quality of barley has a significant impact on the beer's overall quality and market acceptability. [

7]. Mycotoxin contamination can occur in beer, which is also prone to being affected by infected raw materials such as barley, malt, hops, or adjuncts [

8].

Alternaria,

Aspergillus,

Penicillium, and

Fusarium are the most common fungal genera in malting barley that produce a wide range of mycotoxins at the same time, fusarium fungi isolated from barley grains were able to generate Alternaria toxins, aflatoxins, ochratoxin A, deoxynivalenol, and zearalenone, with almost 30% of

Alternaria being the most capable, as well as 88% of

Fusarium fungi [

9].

Numerous studies on beer have primarily focused their research on deoxynivalenol (DON), as it is the most prevalent mycotoxin and poses the most significant public health concern related to beer consumption [

3,

10,

11,

12,

13].

In beer production, barley is the primary ingredient, alongside water, hops, and yeast, all of which can be susceptible to fungal contamination. The presence of fungi on barley grains during malting, which involves soaking, germination, and kilning, is a critical point where mycotoxins can be introduced into the brewing process [

14]. Throughout the brewing process, the stability and solubility of mycotoxins allow them to persist, and in some cases, even concentrate. During the mashing and boiling stages, where barley malt is converted into fermentable sugars and hops are added for flavor, thermal stability enables toxins like DON and FUM to survive [

15]. The subsequent fermentation stage, in which yeast converts sugars into alcohol, does not significantly reduce mycotoxin levels. Although certain yeast strains can bind small amounts of these toxins, this effect is not sufficient to eliminate them entirely. Filtration and clarification steps, which remove suspended solids, also do little to reduce mycotoxin levels [

15]. In the final stages of packaging and storage, mycotoxins remain chemically stable, requiring strict control of environmental conditions to prevent further fungal contamination [

15]. The persistence of mycotoxins in beer highlights the importance of adhering to stringent regulatory standards to ensure product safety [

15].

The European regulations currently in force regulate the maximum levels of mycotoxins permitted in food products, as specified in the Commission Recommendation 2023/915/EU [

16]. These limits are established for specific contaminants present in cereal-based products, including beer. In particular, the limit values set are 3 µg/kg for ochratoxin A (OTA), 2 µg/kg for aflatoxin B1 and 4 µg/kg for the sum of aflatoxins B1, B2, G1 and G2. These parameters apply to cereals and their derivatives. For other mycotoxins, however, the limits refer exclusively to unprocessed cereals and not to derived products. For example, for deoxynivalenol (DON), the maximum limit is 750 µg/kg for unprocessed cereals other than durum wheat, oats and corn. For Fumonisins (B1 and B2), the limit is set at 4,000 µg/kg for unprocessed corn. For T-2 and HT-2 toxins, European Commission Regulation 2024/1038 establishes specific limits depending on the different raw materials used in the food chain, with particular reference to cereals such as maize, barley, oats and durum wheat [

17]. The limits vary greatly depending on the type of raw material, with values ranging from 50 µg/kg to 1,250 µg/kg. Although these limits do not apply directly to beer, it is essential that producers carefully monitor raw materials to ensure that mycotoxin concentrations are always safe. Careful monitoring is essential to ensure the quality of the final product and protect the health of consumers.

So, it's clear that researchers are consistently striving to develop quick and dependable methods for identifying mycotoxins in both raw materials, like cereals, and final products [

18]. To identify the new analytical procedures that evaluate their presence in food products and, in particular, in beer, was fundamental. A new method based on liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC/ESI-MS/MS) for simultaneous qualitative and quantitative determination of 9 mycotoxins was developed. A new multianalyte IAC (AOFZDT2TM column), containing antibodies for aflatoxins (AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, AFG2), Ochratoxin A (OTA), Fumonisins (FB1, FB2), Deoxynivalenol (DON) and HT-2 was used as single extraction and clean up step.

LC-MS is the dominant technique applied for the separation and characterization of mycotoxins due to its ability to quantify and identify analytes at low concentrations in the presence of interferences [

19], of which beer has many. In this respect, LC-MS may be a more appropriate alternative to the standard fluorimetric or UV detection methods currently used in order to understand the presence of specific mycotoxins [

20]. Using LC-QQQ-mass analyzer allows for higher accuracy ion mass measurements and introduces the potential for predicting the compounds that may be responsible to evaluate the potential toxicity of beer [

21]. The usage of advanced analytical techniques in the brewing industry could potentially assist to improve quality control practices or provide brewers with a better understanding of how the ingredients and processes affect their finished product [

21]. Of course, LC-MS represents a much larger capital investment than a classic HPLC-UV-RF instrument, and it is more complicated to operate. However, if one desires to parse the vast degree of chemical variation in the products produced by today’s craft brewing industry, instrumentation with much higher specificity is needed, and LC-MS is one obvious choice for this task [

21]. High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) are essential tools for detecting and quantifying these toxins at trace levels. These methods offer high sensitivity and specificity, making them indispensable for monitoring compliance with regulatory limits [

22].

Recent innovations have further enhanced the ability to detect and manage mycotoxins in beer. The introduction of Vicam 6-in-1 immunoaffinity columns allows for the simultaneous extraction and purification of multiple mycotoxins, including aflatoxins, OTA, DON, ZEN, and fumonisins, from complex brewing matrices [

23]. The Vicam 6-in-1 immunoaffinity columns represent a novel approach to overcoming these challenges. These columns are designed for the simultaneous extraction and purification of multiple mycotoxins from complex matrices, such as beer, in a single step. Their use reduces labor, minimizes matrix interferences, and optimizes analytical workflows. The Vicam 6-in-1 immunoaffinity columns offer a robust and innovative solution for detecting multiple mycotoxins in beer. Their high specificity streamlined work-flows, and multiplex capabilities address the challenges associated with complex brewing matrices. This study demonstrates their utility in ensuring the safety and quality of beer, providing valuable insights for risk assessment and quality control. The integration of these columns into routine testing supports compliance with regulatory requirements while safeguarding consumer health.

Their integration with HPLC-MS has proven effective in ensuring accurate detection and supporting brewers in meeting international safety standards. Studies indicate that deoxynivalenol (DON) is the most prevalent mycotoxin in beer, particularly in wheat-based beers, where its levels are higher compared to barley-based varieties [

24]. This disparity arises from the differing susceptibility of wheat and barley to fungal contamination. Other mycotoxins, such as Fumonisins and OTA, are also frequently detected in beer, underscoring the need for comprehensive monitoring across different styles and production methods [

25]. Advanced tools like LC-MS empower brewers to better understand how raw materials and production processes influence mycotoxin levels, enabling them to refine their practices and ensure product safety. Despite these efforts, mycotoxins remain a persistent challenge due to their chemical stability and ability to carry over through the brewing process. By focusing on the quality of raw materials, employing advanced analytical techniques, and maintaining stringent production controls, brewers can minimize risks and meet regulatory requirements. These measures ensure the production of safe, high-quality beer while protecting consumer health and supporting the industry’s reputation for safety and excellence. The described analytical method, involving the use of Vicam 6-in-1 immunoaffinity columns coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS), has also been applied to both craft beers and freeze-dried beer samples.

This extension aimed to enhance the analytical performance of the method while minimizing the occurrence of false positives or negatives that may arise from improper sample handling. Freeze-drying beer offers the advantage of preserving the sample's integrity over time and reducing potential matrix effects that can interfere with mycotoxin detection [

26]. By converting the beer into a stable powdered form, the likelihood of degradation or contamination during storage is significantly reduced, ensuring consistency in sample preparation and analysis [

26]. This approach also facilitates the reconstitution of samples under controlled conditions, allowing for more accurate comparisons across different brewing styles and production processes.

The application of this method to freeze-dried beer demonstrated its robustness and adaptability, confirming that the use of immunoaffinity columns effectively isolates multiple mycotoxins from complex matrices. This, combined with the precision of HPLC-MS, supports the reliable identification and quantification of mycotoxins in both liquid and freeze-dried beer samples. By reducing the risks associated with sample variability and handling errors, the method offers a reliable solution for routine testing, ensuring accurate results that contribute to improved quality control and safety in beer production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Reagent

Acetonitrile, methanol, toluene (all HPLC grade) and glacial acetic acid were purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker (Milan, Italy). Ultrapure water was produced by a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Ammonium acetate (for mass spectrometry), AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, AFG2, FB1, FB2, OTA, DON, and HT-2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Whatman GF/A glass microfiber filter papers were obtained from Whatman International (Maidstone, UK). DONtestTM HPLC, T-2testTM HPLC and AOFZDT2TM immunoaffinity columns were obtained from VICAM (Watertown, MA, USA). Phosphate-buffered solution at pH 7.4 (PBS) was prepared by dissolving commercial phosphate-buffered saline tablets (Sigma-Aldrich) in distilled water.

2.1.1. Samples

The sample extraction and purification procedure was based on the work carried out by Lattanzio VM.T. et al. 2007 [

27]. Three lager beers produced in a pilot plant were used to develop the method. Beer sample stored at +4°C were degassed (3 cycles of 10 minutes each at +10°C to avoid excessive sample heating). The same lager beer was also converted to a powder using freeze-drying processes (Alpha 1-2LDplus).

2.2. Sample Preparation

The beer samples degassed (10 ml) were first extracted with 50 mL PBS, by shaking for 60 min. After centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 min, 35 mL of PBS extract (extract A) were collected and filtered through a glass microfiber filter. Then 35 mL methanol was added to the remaining solid material, containing 15 mL PBS, and the sample was extracted again by shaking for 60 min. After centrifugation (3000 g, 10 min), 10 mL of methanol/PBS extract were diluted with 90 mL PBS to reduce the organic fraction and filtered through a glass microfiber filter (extract B). Aliquots of the two extracts were separately submitted to cleanup through the same multianalyte IAC. 50 mL of extract B were passed through the AOFZDT2TM column at 1–2 drops per second; the column was then washed with 20 mL PBS to completely remove methanol residues. After passing 5 mL of extract A that was eluted at 1–2 drops per second, the column was washed with 10 mL distilled water to remove PBS residue and matrix interfering compounds. Toxins were eluted from the column with 3 mL methanol in two steps of 1.5 mL each at 1 drop per second. After the first step, a 5 min interval was allowed to favor methanol-antibody contact; complete elution of all toxins was obtained with the second elution step followed by air flushing through the column. The methanolic eluate was dried under an air stream at 50°C and reconstituted with 250 µL of mobile phase. The sample was stored at -18° in the dark until analysis. 100 µL were injected to be analyzed by LC/MS/MS. The same extraction procedure was carried out on the freeze-dried beer (500 mg of lyophilized sample was made up to volume with 5 ml of water). As control, the same beer doped with known standard concentrations of mycotoxins (Ochratoxin A, Afla B1, Afla B2, Afla G1, Afla G2, Fumonisin B1, Fumonisin B2 and Deoxynivalenol) according with legal limit, was also extracted. For HT-2, the spiking amount was chosen arbitrarily to 500 µg/L because this mycotoxin level was not regulated.

2.3. Standard and Matrix-Matched Calibration

Stock solutions of each mycotoxin were prepared at different concentrations by diluting the solutions in the appropriate solvent. DON, HT-2 were dissolved in acetonitrile, AFs in toluene/acetonitrile 99:1, OTA in toluene/acetic acid 99:1, and FBs in acetonitrile/water 1:1. Subsequently, a mix containing all the mycotoxins to be analyzed at the maximum concentration allowed by legal limits was prepared. This mix was then diluted differently and used to prepare calibration solutions and the spiking solution. Calibration solutions for the standard calibration curves (at 5 points) were prepared in the LC mobile phase (methanol/water 40:60, containing 1 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1% acetic acid) by dissolving appropriate amounts of the starting mix solution.

2.4. LC-ESI MS/MS Method

The Shimadzu Nexera X2 chromatograph coupled with LCMS-8050 Triple Quad LC/MS detector (Shimadzu Corporation, Milan, Italy) was used for separation of mycotoxins. The UHPLC system consisted of a binary pump, automatic degasser, column heater and autosampler. The MS/MS system was equipped with an ESI source operating in the positive ion mode according to the parameters shown in

Table 1.

The optimization of ionization source and MS parameters, individually for each analyte, was operated using the direct standard infusion of the standard solutions.

The chromatographic elution was conducted using a LUNA 3µm C18 (100 Å- size 150 X 3 mm) preceded by a Gemini C18 guard column (4 mm x 2 mm, 5 µm particles) as stationary phase and a gradient MeOH:H20 (40:60 containing 1 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1% acetic acid) as mobile phase (

Table 2).

2.5. LOD e LOQ

The method's detectability was confirmed through the established limits of detection (LOD) and limits of quantification (LOQ) for each mycotoxin. LOD and LOQ were defined as the lowest concentrations of each mycotoxin that produced signal to noise ratios of 3:1 and 10:1, respectively.

2.6. Selectivity

The method's selectivity was evaluated by analyzing blank samples and blank samples spiked with the target mycotoxins. This assessment was based on monitoring the characteristic multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions for each mycotoxin at their specific retention times and verifying the relative response ratio between quantification and confirmation channels.

3. Results and Discussions

A new technique has been created to determine multiresidual analyses of mycotoxins using just one sample preparation. The method was applied to craft beer and freeze-dried craft beer and the method performance characteristics were determined after spiking the beers with mycotoxins as model matrix at multiple concentration levels according to legal limit.

The investigation of the spiked model matrix confirmed linearity and precision of the method. The limits of detection were below the regulated values of mycotoxins in beer.

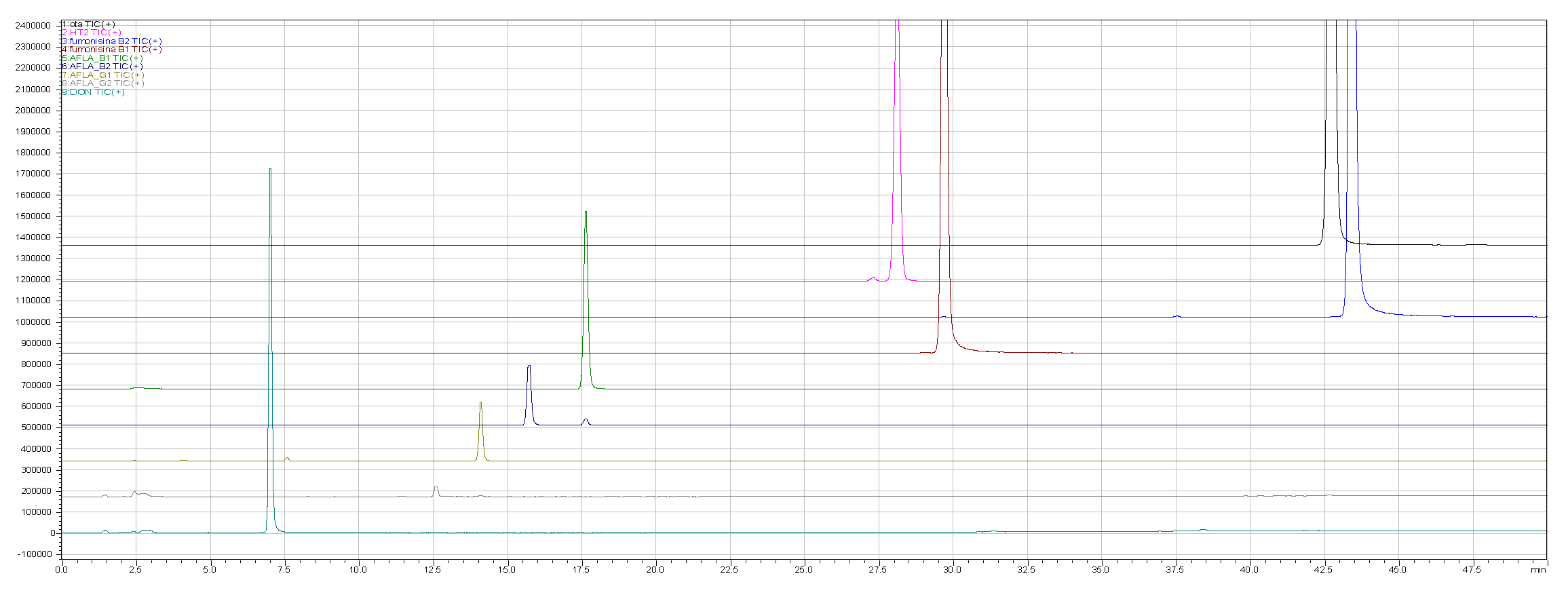

Figure 1 shows the different profiles related to the doped beer (obtained by adding the standard mixes) used as a reference against the same beer (not doped).

The developed methodology enabled the detection of the “co-occurrence” of various mycotoxins while at the same time determining the quantity of each mycotoxin in a single analysis.

The development of the method involved the extraction and purification of the mycotoxins, the optimization of the mass parameters followed by the chromatographic optimization.

The MS detection was carried out in MRM mode, in order to obtain a high sensitivity and selectivity for each analyte, based on the generation of protonsified molecular ions from the source of the mycotoxins, as well as on the collision-induced production of fragments of specific ions of the mycotoxin. The specific MRM mycotoxins transition as well as their corresponding fragment voltages, collision energies and dwell were determined individually for each analyte (

Table 3).

The chromatographic method for simultaneous identification of mycotoxins has been refined by optimizing various analytical parameters, including the choice of columns, the mobile phase, flow rate, and oven temperature. Following this, parameters such as flow rate, oven temperature, and injection volume were fine tuned.

Chromatographic separation was further enhanced by adjusting the mobile phase composition, resulting in a gradient mode.

Our method achieved elution times of approximately 45 minutes for 9 mycotoxins.

The assessment of potential interferences in compound quantification, arising from the direct injection of beer, was conducted through the evaluation of matrix effects (ME).

Five levels were utilized to create matrix calibration curves. ME was computed leveraging the slopes of the calibration curves in both solvent and matrix. The matrix effect remains well within the acceptable range of 80% to 120%.

Regarding the development of the multi-mycotoxin method in beer, in figs. 1a, 1b and 2 the chromatographic results are shown.

In detail, a method that allows, through a single analysis, the determination of 9 mycotoxins: Ochratoxin A, Aflatoxins (B1, B2, G1 and G2), Fumonisins (B1 and B2), Deoxynivalenol and HT-2 has been developed.

Five concentration levels of mycotoxins standards were prepared from a stock solution at different concentration ranges (

Table 4). Five analyzes were performed for each concentration level with the LC-MS 8050 system under optimized chromatographic conditions. By obtaining the equations for the regression line, five calibration curves were constructed using the least squares method. Mandel's test proved that all calibration curves within the considered range were linear. The limits of quantification (LoQs) and limits of detection (LoDs) (

Table 4) were calculated by multiplying the standard deviation (SD) of the lowest level of the calibration curve (n = 7) ten and three times, respectively, and dividing the result for the slope of the calibration curve.

The repeatability and reproducibility values (

Table 4) were expressed as percentage coefficient of variation (CV%) and calculated using the average of the areas of the lowest level of the calibration curve (n=5) divided by the corresponding standard deviations. Finally, the fourth level (n=4) of each calibration curve (

Table 5) was used to determine the retention time, instrumental recovery, and percentage relative standard deviation (RSD%).

Figure 1 (1a and 1b) shows the different profiles related to the doped beer (obtained by adding the standard mixture to the model beer) used as a reference with respect to the same beer (undoped).

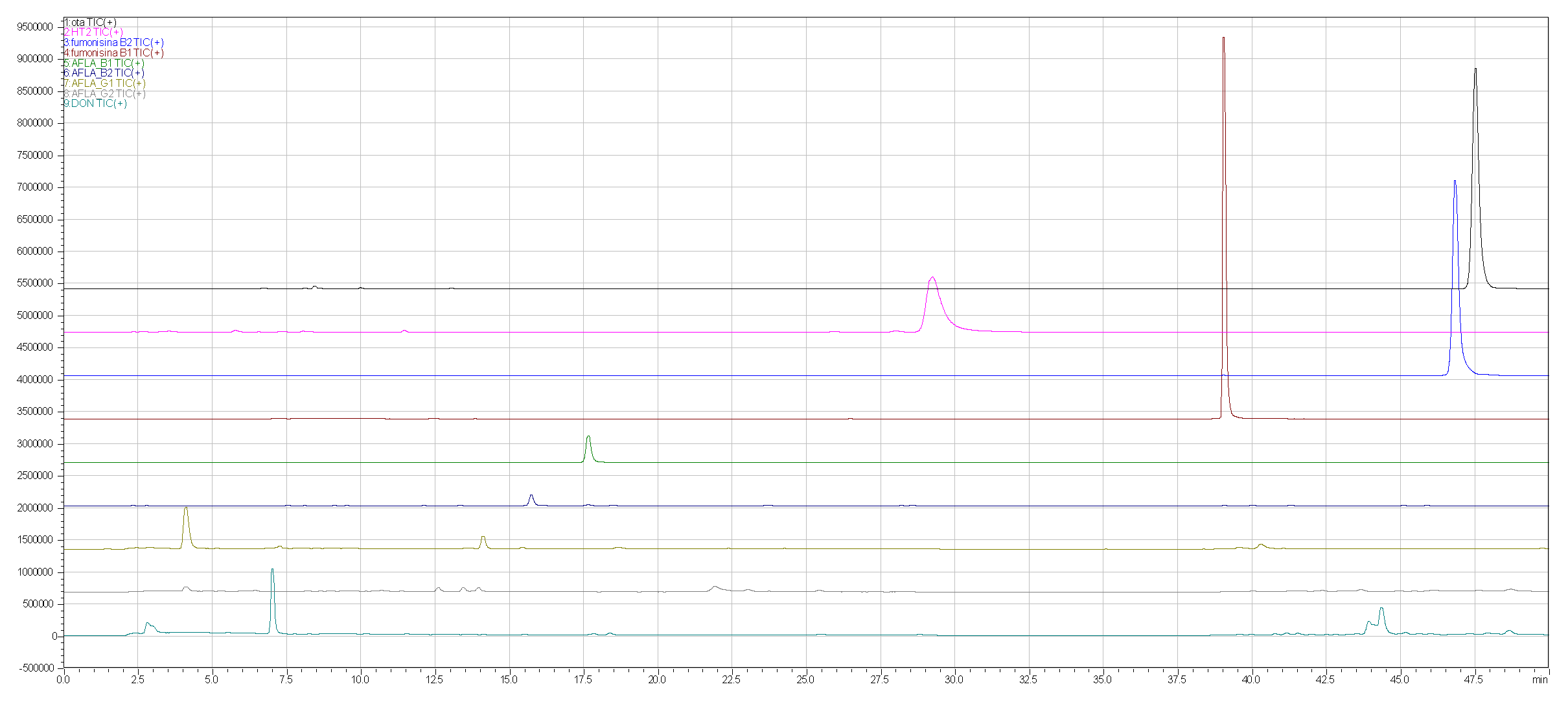

Figure 2 shows the profile for freeze-dried and doped beer (obtained by adding the standard blend to the freeze-dried model beer).

Figure 1.

a: SCAN freeze-dried doped beer with standards mix

Figure 1.

a: SCAN freeze-dried doped beer with standards mix

Figure 1.

b: SCAN undoped beer

Figure 1.

b: SCAN undoped beer

Figure 2.

SCAN doped beer with standards mix.

Figure 2.

SCAN doped beer with standards mix.

Using freeze-dried beer instead of traditional liquid beer in mycotoxin analyses significantly enhances the efficiency of the extraction and purification process when utilizing VICAM columns. The freeze-drying process concentrates the analytes, reducing the sample's water content and simplifying matrix handling. This results in improved recovery rates and cleaner extracts, allowing the VICAM columns to operate more effectively. Moreover, the reduced sample volume minimizes potential interferences, further optimizing the analytical workflow and ensuring more accurate and reliable detection of mycotoxins.

4. Conclusion

Mycotoxin contamination poses a significant concern for food safety, to ensure consumer health and comply with international regulatory standards, it is essential to implement rigorous control measures. Managing mycotoxins in beer production relies on a combination of preventive strategies and advanced analytical approaches. The use of high quality raw materials, sourced from reliable suppliers who adhere to strict safety standards, is fundamental. Good manufacturing practices, rigorous hygiene protocols, and proper post-harvest treatments such as drying and controlled storage further mitigate contamination risks [

15].

During the study, a new, rapid, and straightforward analytical method was developed and validated for the simultaneous determination of nine mycotoxins in beer.

This method, based on liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), represents an innovative approach to multi-mycotoxin analysis, enabling comprehensive screening of potentially co-occurring mycotoxins in craft beer. In this context, VICAM 6-in-1 columns provide an invaluable tool for the simultaneous detection of multiple mycotoxins with precision and efficiency. These columns offer significant advantages in terms of operational cost reduction, as they require less labor, minimize reagent consumption, and provide faster turnaround times. Such features optimize laboratory resources and enhance operational efficiency, making the analytical process more sustainable and cost-effective. Although this is a preliminary study requiring further investigation, the results obtained thus far indicate that the developed LC-MS/MS method is a promising tool for effective screening.

It not only allows the identification of a broad spectrum of mycotoxins but also enhances risk management capabilities and promotes greater transparency and safety throughout the production chain. Looking ahead, the adoption of advanced analytical methods such as this could significantly contribute to improving the quality of the final product, strengthening consumer trust in craft beers, and supporting producers in meeting stringent regulatory requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.R., S.C., R.d.S. P.A.; methodology, S.C, R.d.S. and M.R.; formal analysis: P.A, F.I., S.C., R.d.S; investigation: P.A, F.I, S.C., R.d.S..; resources: M.R.; data curation: P.A, M.G, M.R., S.C., R.d.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A, F.L., S.A., S.C., R.d.S., M.R.; writing—review and editing: P.A, M.R., S.C., R.d.S.; visualization: R.d.S., S.C., P.A., F.L., S.A.,; supervision: M.R.; project administration: M.R.; funding acquisition: M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript