1. Introduction

Changes in lifestyle and dietary consumption, in developed and developing countries have highlighted the importance of dietary fibre (DF). The widely accepted definition of DF refers to all polysaccharides and lignin that cannot be digested by endogenous human digestive enzymes. DF can be divided into soluble DF (SDF) and insoluble DF (IDF) based on solubility, and fermentable DF (FF) and non-fermentable DF (NFF) based on fermentation of the gut microbiota. SDF primarily include pectin, tree gum, and some hemicellulose [

1]. SDF has a high-water retention capacity and viscosity, and thus can delay the emptying rate of the gastrointestinal tract. In addition, SDF produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) after fermentation by intestinal microorganisms. IDF primarily includes cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and chitin. IDF can increase the transportation rate and water retention capacity of the intestinal contents, shorten the fermentation time of indigestible foods in the colon, and increase faecal volume [

2]. Desai

et al. [

3] reported that long-term or indirect deprivation of DF in the diet of mice resulted in the use of host-secreted mucin as a nutrient source by the gut microbiota, which caused thinning of the intestinal mucus layer and damage to the intestinal barrier. Infection with

Citrobacter rodentium led to entry of the bacteria into the intestinal epithelium of mice deprived of DF, which in turn led to fatal colitis. These results suggest that the gut microbiota caused by insufficient DF degrades the colonic mucosal barrier and increases pathogen sensitivity. Mice rich in DF have complete barrier function and reduced susceptibility to intestinal pathogens, indicating that DF can protect intestinal health. The gut microbiota colonises after birth, when the newborn comes into contact with maternal and environmental microbes [

4]. The effects of maternal microbes on offspring gut microbiota have been studied. The results indicate that a maternal high-fat diet can cause intestinal microbiota disorders and metabolic disorder in offspring, leading to the programmed development of various diseases, and such negative effects may persist into offspring adulthood [

5,

6]. A recent study found that the proportion of Firmicutes in mice fed a high-fat diet was higher, the proportion of beneficial microbiota was lower, and the changes in intestinal microbes among offspring groups were similar to those in the maternal group[

6].

The pea plant (

Pisum sativum L.) is a leguminous plant that is rich in protein, starch, minerals, and DF. Pea plants have high nutritional value. Its IDF is approximately 10% to 15% and its SDF is approximately 2%–9% [

7]. Pea fibre has a balanced proportion of SDF and IDF, and a good adsorption capacity for cholesterol and glucose. It can regulate the glucose response, lipid metabolism and intestinal motility [8-10]. Adding high concentrations of yellow pea flour can decrease insulin and glucose levels in golden Syrian hamsters [

11]. Using methods that include quantitative proteomics and macroproteomics, targeted screening was conducted on 34 types of DFs. The analysis indicated that feeding mice pea fibres selectively affected Bacteroides, leading to a significant expansion of

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. This finding indicates that pea fibre is a potential nutritional source for multiple species of gut microbiota and microbiota-accessible carbohydrates, which play important roles in shaping the gut microbiota ecosystem [

12]. In addition, studies have found that a low-DF or DF-deprived diet increases the likelihood of chronic diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease and diarrhoea, in the body [

13]. A recent study demonstrated that by-products of peas alter glucose metabolism in humans [

8], which may have relevance elsewhere [

14].

Previous studies have focused on the effects of processing technology and different genetic varieties of peas on health. Whether dietary fibre supplementation to the diet can improve the health of mice and their offspring is unclear. This study explored the rational use of DF and the impact of parental DF deprivation on offspring health, enriching maternal DF nutrition.

3. Results

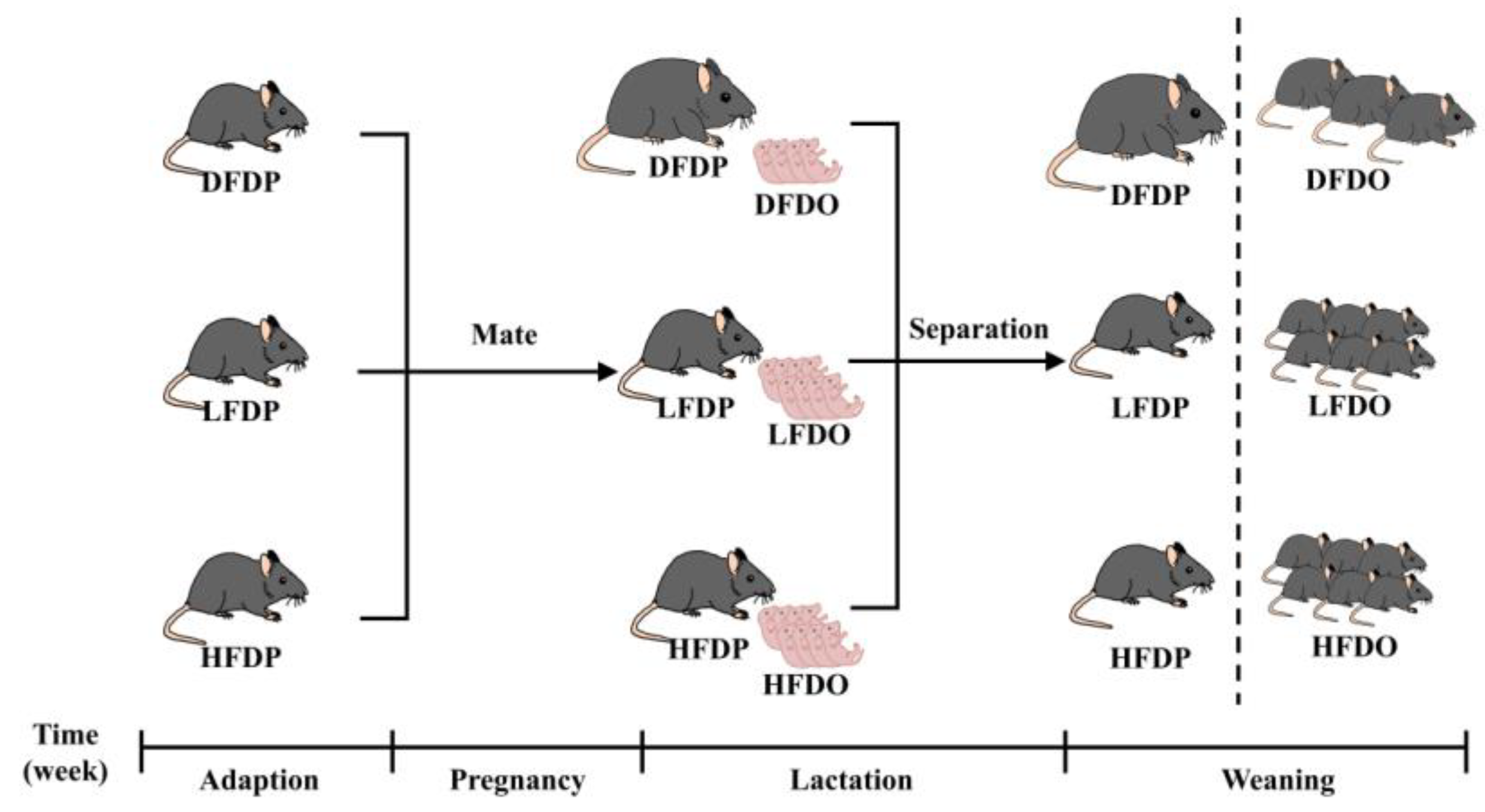

3.1. Effects of pea fibre on growth and development in maternal and offspring mice

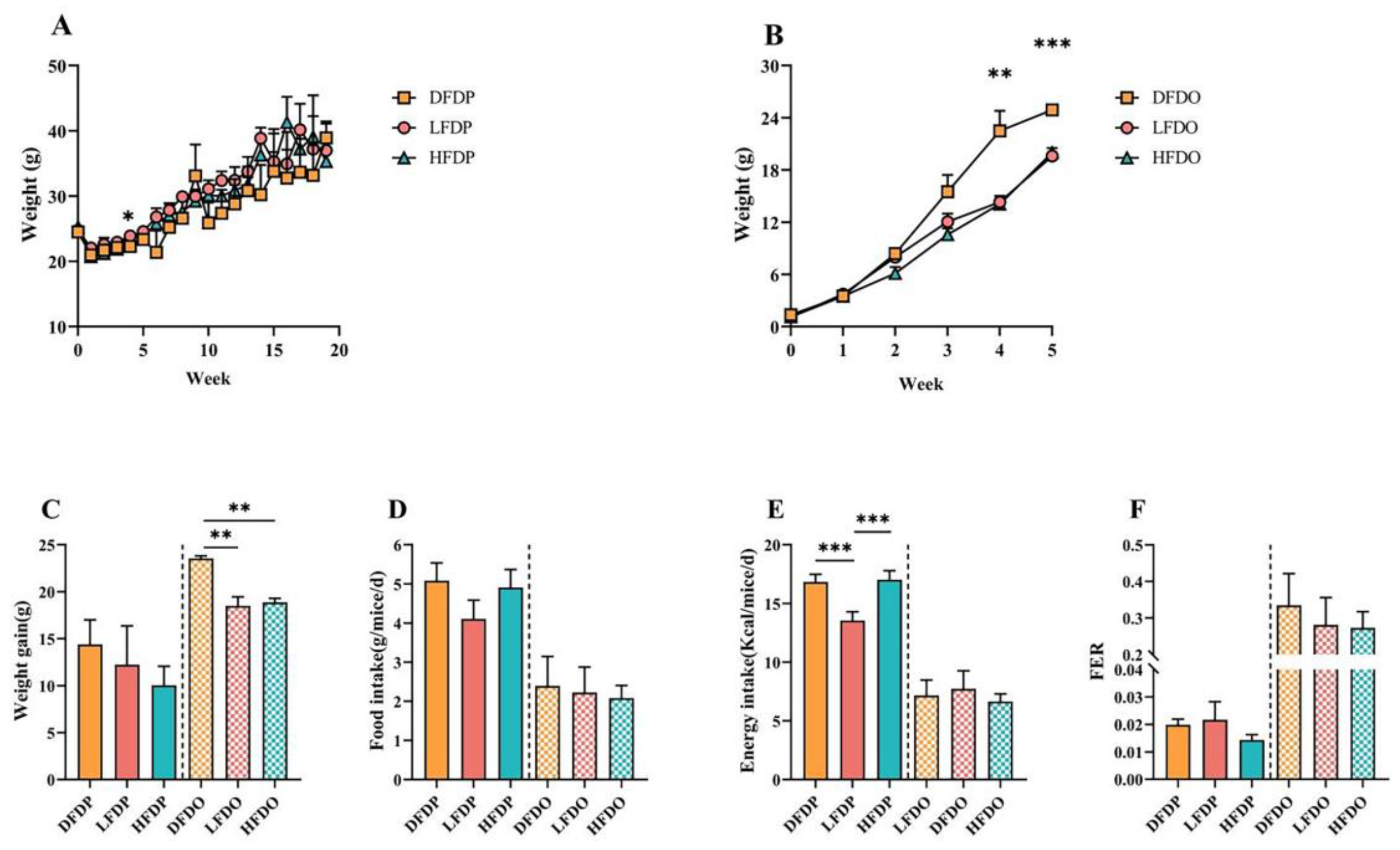

The effects of pea fibres on the growth performance of maternal and offspring mice are shown in Figure 2. The initial body weights of the maternal mice were similar among the groups. During the 20 weeks of feeding, maternal mice in the three groups showed different increases in body weight (Figure 2A). Weight gain was higher in the DFDP group than in the HFDP and LFDP groups (Figure 2C). The food intake of the DFDP group was higher than the intake of the HFDP and LFDP groups (Figure 2D). Additionally, compared to LFDP, energy intake in DFDP and HFDP was significantly high (p < 0.001) (Figure 2E), whereas the food efficiency ratio (FER) in LFDP was higher than the FER in the HFDP and DFDP groups (Figure 2F).

Compared to the maternal group, the indicators of growth performance among the offspring improved. During the period of weaning (4–5 weeks of age), the body weight of the DFDO group was significantly higher than the body weight of mice in the LFDO and HFDO groups after fibre deprivation (4 weeks of age, p < 0.01; 5 weeks of age, p < 0.001) (Figure 2B). There were significant differences in weight gain (p < 0.01) among the DFDO, LFDO, and HFDO groups (Figure 2C). The FER in the HFDO group was higher than the FER in the DFDO and LFDO groups (Figure 2F). Our research indicates that DF deprivation in parents may induce obesity in offspring.

Figure 2.

Effects of pea fibre on growth and development of maternal and offspring mice. (A) body weight of maternal mice; (B) body weight of offspring mice; (C) weight gain; (D) food intake; (E) energy intake; (F) food efficiency ratio (FER) = [weight gain (g/day)]/ [food intake (g/day)]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Effects of pea fibre on growth and development of maternal and offspring mice. (A) body weight of maternal mice; (B) body weight of offspring mice; (C) weight gain; (D) food intake; (E) energy intake; (F) food efficiency ratio (FER) = [weight gain (g/day)]/ [food intake (g/day)]. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

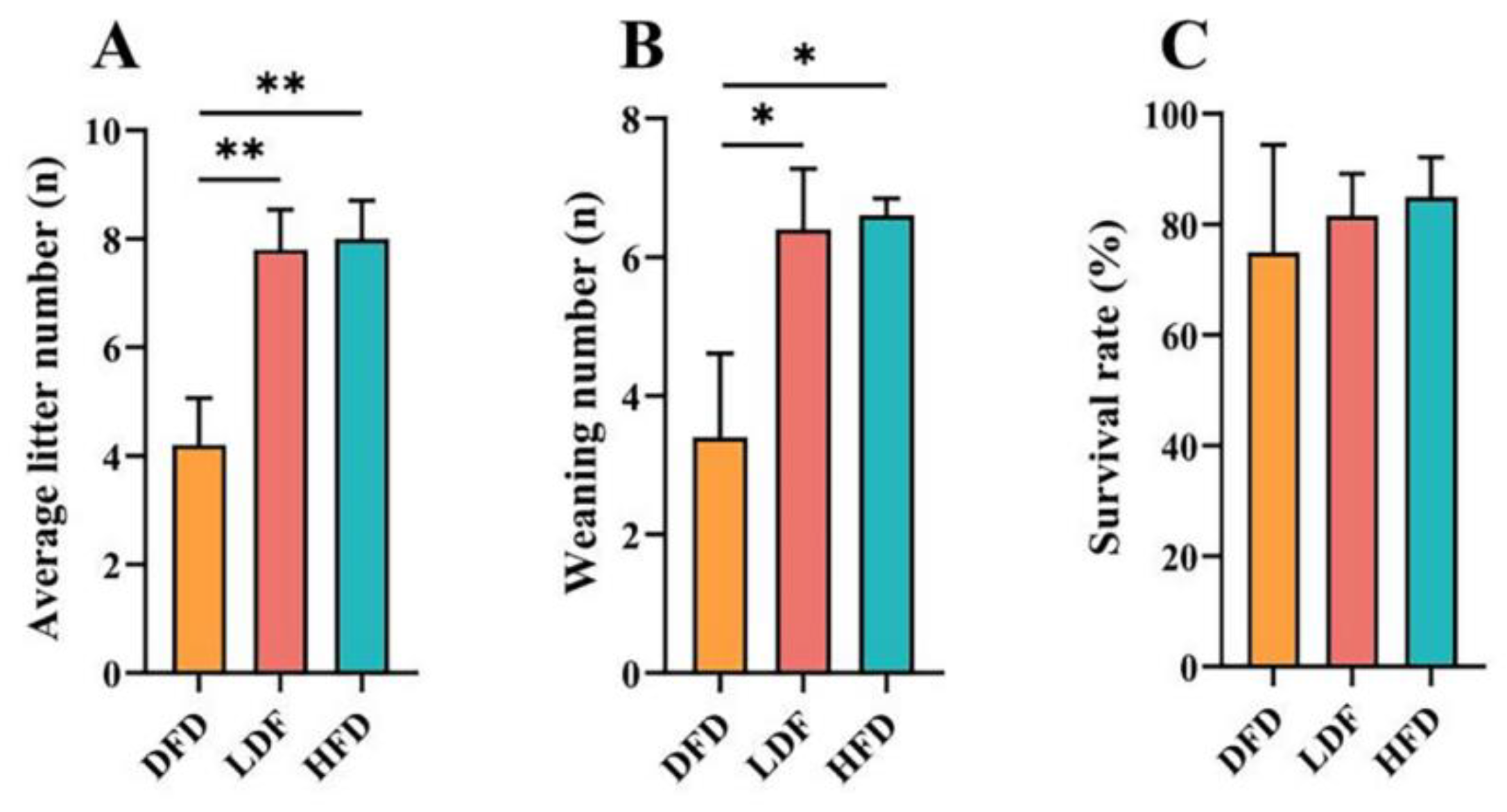

3.2. Effects of pea fibre on maternal reproductive performance

The effects of pea fibre on maternal reproductive performance are shown in Figure 3. The fertility rate of 67% was higher than the rate in the LFD and DFD groups. In addition, compared with the DFD group, offspring in the LFD and HFD groups had significantly higher average litter numbers at birth (p < 0.01) (Figure 3A) and weaning numbers at 21 days of age (p < 0.05) (Figure 3B). There was no significant difference in the survival rates among the three groups, and the survival rates of the offspring in the LFD and HFD groups were higher than the rate in the DFD group (Figure 3C). The findings indicate that DF deprivation can decrease the reproductive performance of female mice, especially the average litter size and number of weaned mice.

Figure 3.

Effects of pea fibre on maternal reproductive performance parental mice. (A) average litter number; (B) weaning number; (C) survival rate. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Effects of pea fibre on maternal reproductive performance parental mice. (A) average litter number; (B) weaning number; (C) survival rate. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

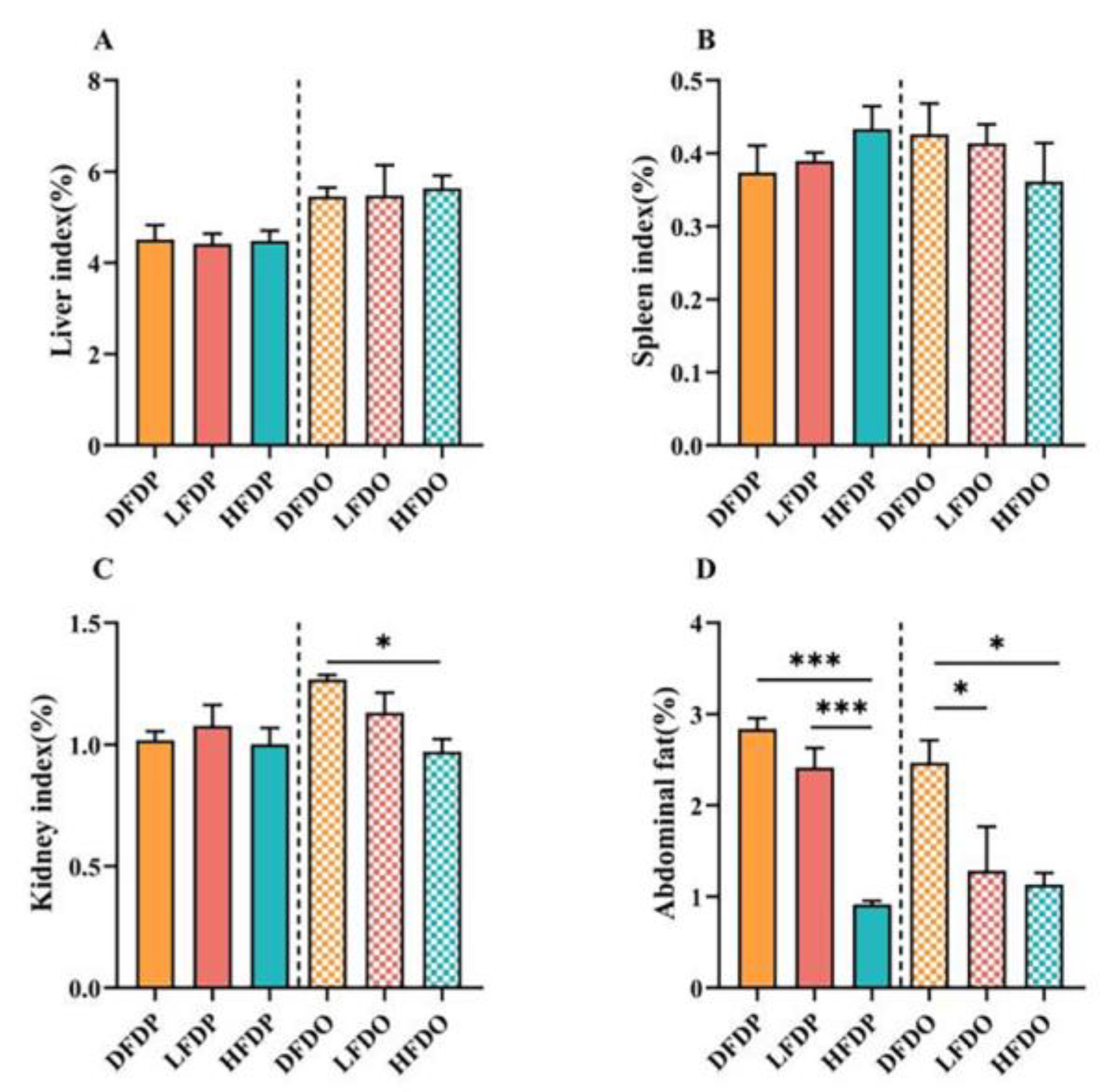

3.3. Effects of pea fibre on organ and intestinal indices in mice

Relative organ and intestinal indices of the mice are shown in Figure 4. There were no significant differences in the liver and spleen indices between the parental and offspring mice (Figure 4A, B). The kidney index was significantly lower in the HFDO group than the value in the DFDO group (Figure 4C). In addition, the abdominal tissue of HFDP mice was significantly lower compared to the DFDP and LFDP groups (p < 0.001) in parental mice. In the offspring mice, the abdominal tissue in LFDO and HFDO groups were significantly lower compared to DFDO (p < 0.05) (Figure 4D). These findings indicate that pea DF can significantly reduce the amount of abdominal fat in parental and offspring mice.

Figure 4.

Effects of pea fibre on relative organ indexes of parental and offspring mice. (A) liver index; (B) spleen index; (C) kidney index; (D) abdominal fat index. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Effects of pea fibre on relative organ indexes of parental and offspring mice. (A) liver index; (B) spleen index; (C) kidney index; (D) abdominal fat index. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The effect of pea fibre on intestinal length and weight in maternal and offspring mice is depicted in Figure 5. There was no significant difference in the lengths of the duodenum, ileum, or colon between maternal and offspring mice (p > 0.05) (Figure 5A, E, J). The jejunum of maternal mice in the HFDP group was significantly shorter than the length in maternal mice in the DFDP and LFDP groups (p < 0.05). In offspring, jejunum length was not significantly different between the groups (Figure 5C). The weights of the duodenum and colon were not significantly different between the maternal and offspring groups (p > 0.05) (Figure 5B, H). Jejunum weight in LFDO mice was significantly higher than that in DFDO mice (p < 0.05) (Figure 5D). The ileum weights of HFDO and LFDO mice were significantly higher than those of DFDO mice (p < 0.001) (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Effects of pea fibre on index of different intestinal segments among maternal and offspring mice. (A) duodenum length to body weight ratio; (B) duodenum weight to body weight ratio; (C) jejunum length to body weight ratio; (D) jejunum weight to body weight ratio; (E) ileum length to body weight ratio; (F) ileum weight to body weight ratio; (G) colon length to body weight ratio; (H) colon weight to body weight ratio. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Effects of pea fibre on index of different intestinal segments among maternal and offspring mice. (A) duodenum length to body weight ratio; (B) duodenum weight to body weight ratio; (C) jejunum length to body weight ratio; (D) jejunum weight to body weight ratio; (E) ileum length to body weight ratio; (F) ileum weight to body weight ratio; (G) colon length to body weight ratio; (H) colon weight to body weight ratio. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.4. Effects of pea fibre on histopathology in maternal and offspring mice

The effects of pea fibre on liver histopathology are presented in Figure 6. Compared to LFDP, DFDP hepatocytes contained a large number of lipid droplet vacuoles (blue arrows) and increased lymphocyte numbers (red arrows). In contrast, HFDP hepatocytes showed improved hepatic cords, a small amount of cell degeneration, and occasional lipid droplet vacuoles. Compared with the maternal groups, the structure of hepatic lobule was relatively clear, the hepatocyte lipid droplet vacuoles and inflammatory cell of the offspring mice were significantly reduced, while the hepatocytes of DFDO still showed obvious inflammatory cell and lymphocyte infiltration compared with the LFDO and HFDO groups. In the LFDO and HFDO groups, the cell cytoplasm was arranged in an orderly manner. However, liver injury was apparent in the DFDO group, as evidenced by infiltration, cell balloon-like appearance of hepatocytes, and hepatocellular necrosis. The findings indicate that DF deprivation caused fatty liver-like lesions and inflammatory infiltration in maternal and offspring mice.

Figure 6.

Effects of pea fibre on liver histopathological of maternal and offspring mice. Representative micrographs of HE staining of liver (original magnification 200×, scale bar 100 μm).

Figure 6.

Effects of pea fibre on liver histopathological of maternal and offspring mice. Representative micrographs of HE staining of liver (original magnification 200×, scale bar 100 μm).

Morphology data of the colonic tissue are presented in Figure 7. There were fewer goblet cells in the colon in the DFDP group compared to the number in the HFDP group. Moreover, among the offspring, there were significantly more goblet cells in mice in the HFDO group than DFDO group (p < 0.05) (Figure 7C). The villus length in HDFO group was significantly longer than the villus length in mice in the DFDO group (p < 0.001) (Figure D). The crypt depth in HDFP group was significantly greater than the depth in DFDP group (p < 0.001) (Figure 7E). the V/C in the HDFO group was significantly greater than the value in the DFDO group (p < 0.001) (Figure 7F). The findings demonstrate that DF deprivation reduced goblet cells and their secreted mucus barrier in the intestines of maternal and offspring mice, as well as more pronounced intestinal villi structural dysplasia in the offspring.

Figure 7.

Effects of pea fibre on global cell among colon of maternal and offspring mice. (A) PAS staining of mice colon (original magnification 100×, scale bar 200 μm); (B) HE staining of mice colon (original magnification 100× (scale bar 200 μm); (C) number of goblet cells in maternal and offspring mice; (D) villus length of maternal and offspring mice; (E) crypt depth ratio of maternal and offspring mice; (F) villus length to crypt depth ratio (V/C) of maternal and offspring mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

Effects of pea fibre on global cell among colon of maternal and offspring mice. (A) PAS staining of mice colon (original magnification 100×, scale bar 200 μm); (B) HE staining of mice colon (original magnification 100× (scale bar 200 μm); (C) number of goblet cells in maternal and offspring mice; (D) villus length of maternal and offspring mice; (E) crypt depth ratio of maternal and offspring mice; (F) villus length to crypt depth ratio (V/C) of maternal and offspring mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.5. Effects of pea fibre on differences in microbiota composition in maternal and offspring mice

The α-diversity measured by the indicator revealed no differences of species diversity among the groups for the maternal mice. The Chao1 index was lower in the LFDP and HFDP groups than in the DFDP group (Figure 8A). The Shannon index was higher in the DFDP group compared the values in the LFDP and HFDP groups (Figure 8C). In contrast, the Chao1 and Shannon indices indicated that the microbiome diversities of mice in the HFDO group were significantly greater than mice in the DFDO group (p < 0.05). In addition, the Chao1 index of the LFDO group was significantly lower than the value of the HFDO group (p < 0.05) (Figure 8B). The Shannon index values of the HFDO and LFDO groups were significantly higher than the DFDO value (p < 0.05) (Figure 8D). The findings indicate that the diversity of the gut microbiota in parental mice decreased after DF deprivation, while the diversity of microbiota in offspring further decreased. Supplementation with DF increased the diversity of parental and offspring mice, and the gut microbiota diversity of the offspring mice was significantly higher than the diversity of maternal mice.

Figure 8.

Effects of pea fibre on α diversity of gut microbiota. (A) Chao1 index in maternal mice; (B) Shannon index in maternal mice; (C) Chao1 index in offspring mice; (D) Shannon index in offspring mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 8.

Effects of pea fibre on α diversity of gut microbiota. (A) Chao1 index in maternal mice; (B) Shannon index in maternal mice; (C) Chao1 index in offspring mice; (D) Shannon index in offspring mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

ANOSIM analysis revealed significant differences in the operational taxonomic units in samples from the DFDP and LFDP groups (R = 0.19, p = 0.03) (Figure 9A, C). Significant differences were observed among the offspring in the HFDO and DFDO groups (R = 0.33 p = 0.01) and the LFDO and DFDO groups (R = 0.52, p = 0.01) (Figure 9B, D).

Figure 9.

Effects of pea fibre on β diversity of gut microbiota. (A) PCoA plot based on unweighted UniFrac in maternal mice; (B) NMDS plot based on weighted UniFrac in maternal mice; (C) PCoA plot based on unweighted UniFrac in offspring mice; (D) NMDS plot based on weighted UniFrac in offspring mice.

Figure 9.

Effects of pea fibre on β diversity of gut microbiota. (A) PCoA plot based on unweighted UniFrac in maternal mice; (B) NMDS plot based on weighted UniFrac in maternal mice; (C) PCoA plot based on unweighted UniFrac in offspring mice; (D) NMDS plot based on weighted UniFrac in offspring mice.

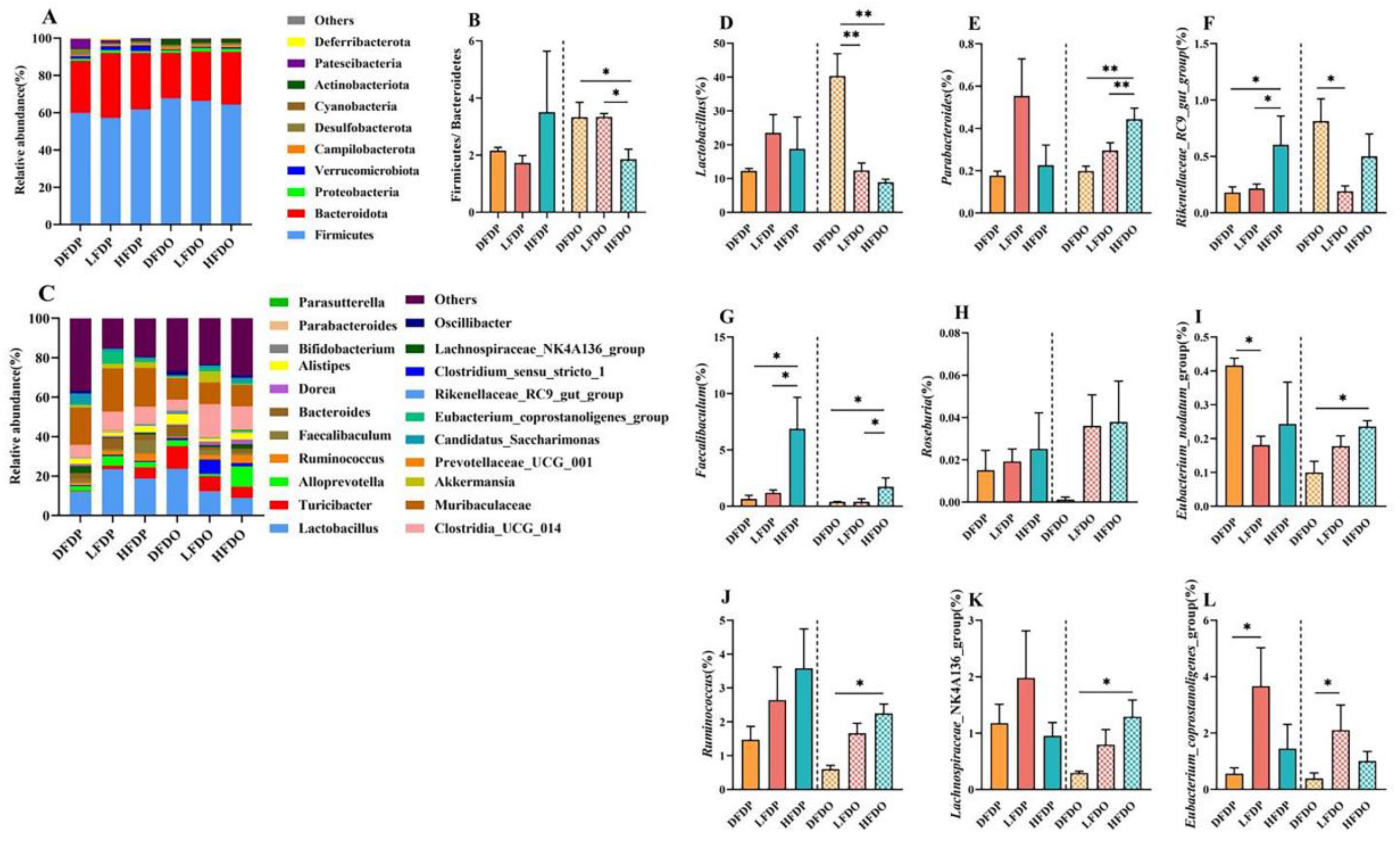

The effect of pea fibre on the abundance of colonic microflora is shown in Figure 10. The dominant phyla in all groups were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobiota. The ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes in the HFDP group was higher than the ratio in the DFDP and LFDP groups. However, the abundance in the HFDO group was significantly lower than the abundance in the DFDO and LFDO groups (p < 0.05). At the genus level, Lactobacillus, Bacteroides and Clostridia_UCG_014 were the most prevalent genera in every group, with Lactobacillus being more prevalent in the LFDP and HFDP groups than in the DFDP group. However, in the offspring group, Lactobacillus in the DFDO group was significantly higher than the prevalence in the LFDO and HFDO groups (p < 0.01). Alloprevotella was more prevalent in the LFDP group was higher than in the HFDP and DFDP groups, and significantly more prevalent in the HFDO group than in the DFDO and LFDO groups (p < 0.05). The abundance of Parasutterella showed the same trend in the maternal group. By comparing the different species of intestinal microflora among the groups, the changes in the intestinal microflora were analysed at the genus level. Faecalibaculum, Roseburia, and Ruminococcus in the HFDP and HFDO groups were higher than in other maternal and offspring groups. Faecalibaculum in the HFDP group was significantly higher than in the DFDP and LFDP groups (p < 0.05). Faecalibaculum and Ruminococcus in the HFDO group were significantly higher than in the DFDO group (p < 0.05). Parabacteroides and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group in maternal mice not significantly different. Among the offspring group, Parabacteroides in the HFDO group was significantly more abundant than in the DFDO group (p < 0.01), and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group was significantly more abundant in the HFDO group compared to the DFDO group (p < 0.05). Lactobacillus in the DFDO group was significantly more abundant than in the LFDO and HFDO groups (p < 0.01), Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group was more prevalent in maternal mice in the HFDP group than in the DFDP and LFDP groups (p < 0.05). However, in offspring mice, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group was more abundant in the DFDO group than in the LFDO and HFDO groups. The Eubacterium_coprostanoligenes_group was significantly more abundant in the LFDP and LFDO groups compared to the DFDP and DFDO groups, respectively (p < 0.05). Finally, the Eubacterium_nodatum_group was more abundant in offspring mice in the LFDP group than in the DFDP group (p < 0.05), and in the LFDO groups than in the DFDO group (p < 0.05).

Figure 10.

Effects of pea fibre on relative abundance of bacteria. (A) colonic microflora structure at phylum level; (B) rate of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes ;(C) colonic microflora structure at genus level; (D-L) significant differential bacteria at genus level in mice between generations of each group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 10.

Effects of pea fibre on relative abundance of bacteria. (A) colonic microflora structure at phylum level; (B) rate of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes ;(C) colonic microflora structure at genus level; (D-L) significant differential bacteria at genus level in mice between generations of each group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

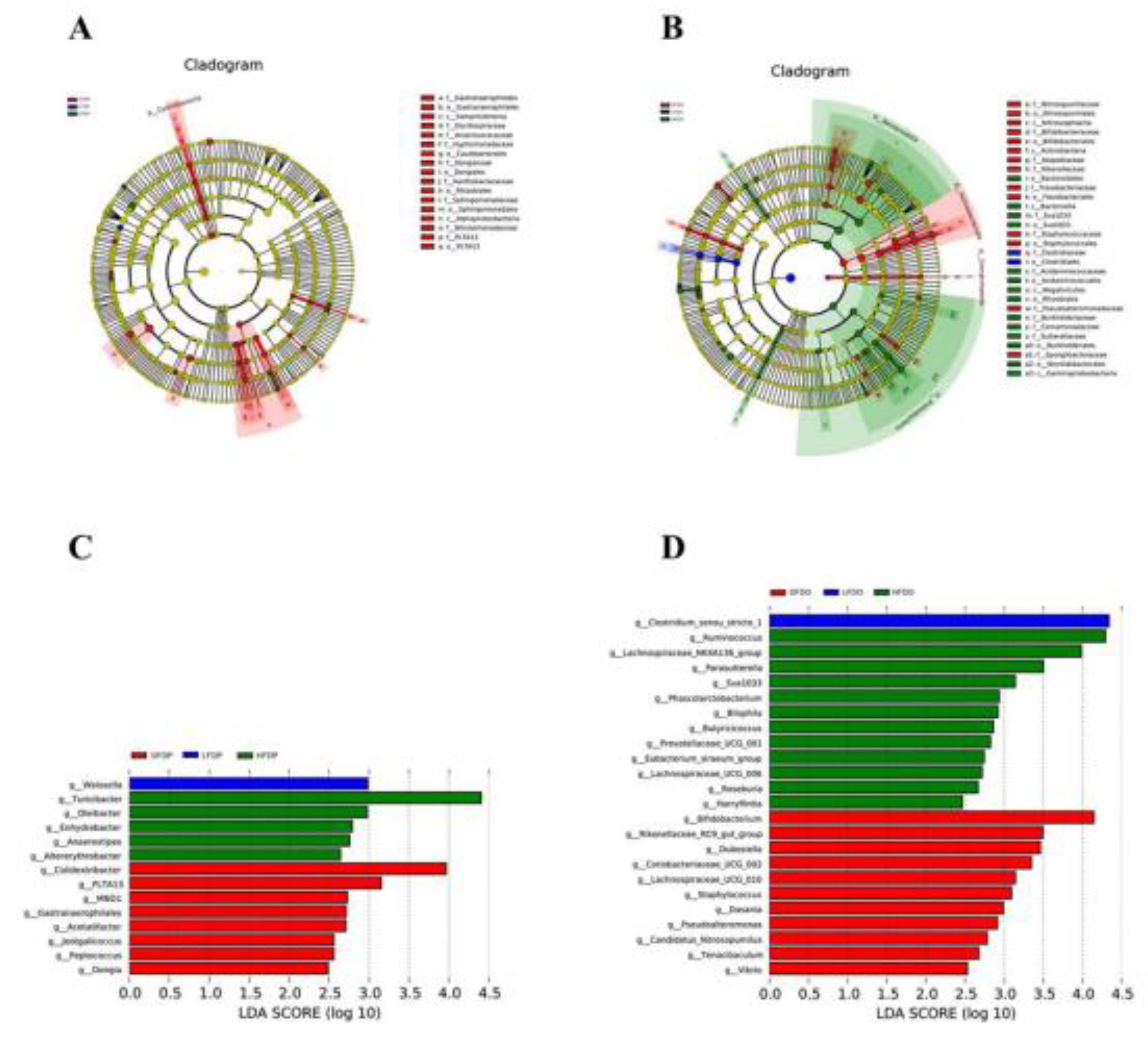

Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) and linear discriminant analysis at the genus level showed the enrichment of Weissella in HFDP mice, Turicibacter in HFDP mice, and Colidextribacter in DFDP mice. Among offspring, some species of fibre-degrading microflora were enhanced in mice fed pea fibre; Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 was enriched in LFDO mice, Ruminococcus in HFDO mice, and Bifidobacterium in DFDO mice

Figure 11.

Effects of pea fibre on LEfSe. (A) evolutionary branching diagram in maternal mice; (B) evolutionary branching diagram in offspring mice; (C) LDA analysis in maternal mice with LDA>2; (D) LDA analysis in offspring mice with LDA>2.

Figure 11.

Effects of pea fibre on LEfSe. (A) evolutionary branching diagram in maternal mice; (B) evolutionary branching diagram in offspring mice; (C) LDA analysis in maternal mice with LDA>2; (D) LDA analysis in offspring mice with LDA>2.

4. Discussion

Peas are a legume that are preferred by consumers because of their nutritional ingredients that include protein, starch, fibre, minerals, and vitamins. These ingredients are considered beneficial to intestinal health owing to their nutritional characteristics, such as improved glycaemic index and plasma lipids [

16,

17]. DF is an important nutrient that regulates intestinal health. Different types of DF have potential impacts on individual indicators, such as body weight [

18,

19]. In this study, pea fibre influenced offspring body weight, especially during weaning. The body weight of fibre-deprived mice was significantly higher than that of high-fibre-fed mice. Our research findings also support the finding that DF deprivation can lead to obesity in offspring. Supplemental DF affected individual body weight and longevity. Yu

et al. [

20] found that fibre deprivation can significantly increase the body weight of naturally aged mice. In our study, the same trend was observed in fibre-deprived mice. In addition, increased abdominal fat and injured liver tissue seem to illustrate the effect of fibre deprivation on obesity. We also observed that in mice fed a diet supplemented with pea fibre, especially offspring mice, in addition to the changes in weight, the accumulation of abdominal fat in the body and lipids in the liver were significantly reduced. These findings reveal that pea fibre can prevent and alleviate obesity. Therefore, pea fibre intake may be conducive to longevity and fibre deprivation may affect individual longevity during the late stages of growth. In a recent study involving a mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the diet was supplemented with pea hulls. The results of multi-omics analyses showed NAFLD was improved by the serine hydroxy methyltransferase 2/glycine/mammalian target of rapamycin/ peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma (SHMT2/glycine/mTOR/PPAR-γ) signalling pathway, with the increasing contents of glutathione, total antioxidant capacity, and adiponectin, which may improve oxidative stress, inhibit lipid peroxidation, and reduce the risk of obesity metabolic abnormalities. In addition, the level of total glyceride, total cholesterol, interleukin-lβ (IL-1β), and IL-6 decreased in liver tissue, which may improve the insulin related reaction [

21]. The findings reveal that pea fibre may prevent obesity through the SHMT2/glycine/mTOR/PPAR-γ signal pathway. The mechanism remains unresolved.

With the emergence of the concept of “mother-offspring-integration” and “One Health”, researchers have become concerned about mother–offspring nutrition. This concern has spurred the recognition of the importance of fibre, which can effectively improve host and offspring gut microorganisms [

22]. In practice, maternal nutrition during pregnancy affects the growth and health of the offspring, which is specifically manifest in growth, development, and reproduction of the offspring. Imbalanced nutrition in the parental generation can induce some diseases in offspring [

23,

24]. In our study, the addition of pea fibre to the diet significantly increased the average litter number at birth and weaning number at 21 days of age. DF has been shown to have a significant influence on reproductive performance. However, the effects of DF on reproductive performance in mice are unclear. Li

et al. [

25] found that sows fed diets containing inulin and cellulose displayed significantly influenced reproductive performance during three successive cycles; the average weight of pigs and litters during the birth and weaning phases was significantly higher than in the control group. Furthermore, Loisel

et al.[

26] described the mortality of offspring before weaning was significantly increased in the gestation group fed feed containing 23.4% total DF compared with the low-fibre group (13.3% total DF). Deprivation of DF and high DF can reduce reproductive performance in mice. Further research is needed to determine the amount of pea fibre required for mice to achieve optimal reproductive performance, and how pea fibres regulate reproductive performance.

Villus length influences the capability to absorb nutrients, which rely on the absorptive area and crypt depth, which in turn indicate the maturation rate of cells. Therefore, the ratio of villus length to crypt depth is considered to be related to digestion and absorption capacity [

27]. We found that pea fibre improved the ratio of villus length to crypt depth, which showed that the villus length increased significantly among offspring mice supplemented with pea fibre, but the crypt depth was higher than that in offspring mice fed a fibre-deprived diet. Maternal mice fed a high-fibre diet displayed the shortest villus length. However, the reason remains unknown. Goblet cells secrete mucus into the intestinal epithelium and play an important role in maintaining intestinal integrity after injury [

28]. During this period, there was no significant difference in the number of goblet cells in the colon. However, after DF deprivation, offspring showed a significant decrease in goblet cells compared to high-fibre diet offspring. Knapp et al. [

29] reported that soluble fibre dextrin and soluble corn fibre can significantly increase the total number of goblet cells per crypt in rats compared to the control group. We speculate that the increased number of cells reflects the acidification of colonic contents and the production of a series of metabolites arising from the synthesis of mucus [

30]. The benefits of pea fibre for intestinal health have been studied previously in piglets. In the study, pea fibre significantly increased goblet cells compared to control group, even though the villus length and crypt depth did not differ from the control group [

31]. However, pea fibre can improve crypt depth and goblet cells in the colon. Moreover, in the present study, piglets fed with pea fibre displayed significantly increased contents of SCFAs in colon compared to the other groups. This change may influence the later growth period.

Aside from its role in nutrient digestion and absorption, the intestine is also an important immune organ for humans and animals. The intestine is considered the second brain of the body, with reports of the bidirectional communication between the intestinal microflora and the brain via the gut–brain axis [

32,

33]. Microbial communities colonise the microflora as a function of self-regulation through mutual interaction [

34]. The intestinal microflora are important in maintaining host health, enhancing the body’s immunity, providing conducive metabolites to the host, and resisting colonisation by pathogenic bacteria [35-37]. In the present study, the relative abundance of the colonic microflora in each group differed. At the phylum level, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the maternal mice showed no significant differences among the groups. However, among the offspring, this ratio was significantly lower in the HFDO group compared to the DFDO and LFDO groups. This trend was also reported in a study on the effects of peas on the rat microflora. The authors described that raw or cooked pea fibre fed to rats increased the relative abundance of Firmicutes and decreased the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes compared to the group fed a high-fat diet [

38]. As the key microflora in the host intestine, Bacteroides and Firmicutes are related to the energy acquisition process. Thus, changes in these microorganisms will affect the host’s glucose homeostasis, anti-inflammatory activity, and other reactions.

DF can help optimise the structure and increase the diversity of the gut microbiota. A diverse gut microbiota can resist infection by exogenous pathogenic microorganisms, promoting intestinal health [

3,

22,

37]. Our research also confirmed that supplementation with pea fibre can increase the diversity of the gut microbiota in both parental and offspring mice. Other studies have reported that DF can improve the host gut microflora, and most microflora can produce SCFAs. These SCFAs include acetate, butyrate, and lactate, among others, which is profoundly important in the gut; the fluctuating content of SCFAs reflects their production by the particular bacteria [

39,

40]. In the present study, at the genus level, significant changes in

Lactobacillus,

Parabacteroides, and

Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group were observed in both maternal and offspring mice. With increasing focus the relationship between intestinal microflora and neuropsychiatric diseases, researchers have found that intestinal microflora can regulate the development and behaviour of the brain through the brain–gut–microbiota axis, which influences some diseases, such as autism, spectrum disorders, depression, Parkinson's disease, and other psychiatric diseases [

41,

42]. In the present study, we found that under the influence of maternal potential, the genera

Parabacteroides,

Akkermansia and

Prevotellaceae_

UCG_ 001 decreased, and

Lactobacillus and

Alistipes increased after DF deprivation, with the same tendencies evident in the offspring. The findings are similar to those of previous studies on neuropsychiatric diseases [43-45]. Furthermore, the early period of growth in autism may be related to early feeding methods; infants who were weaned early showed increased concentrations of propionate and butyrate in faeces, and changes in SCFAs may induce neuropsychiatric diseases [

46]. Butyrate can activate G protein-coupled receptors and can affect neuropsychiatric diseases [

47]. The tendency for DF deprivation in offspring mice may lead to psychiatric diseases later in life. Studies on inflammatory bowel diseases, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, have found that the microflora may affect the occurrence of these diseases through the brain–gut–microbiota axis [

48,

49]. We found that some SCFA-producing bacteria were lower under DF deprivation in maternal and offspring mice. The observation that

Roseburia and

Ruminococcus were lower than in the other groups, indicates that pea fibre deprivation reduced SCFAs production in mice. Li

et al. [

50] reported the decreased abundance of

Roseburia and

Ruminococcus in patients with ulcerative colitis. Li

et al.[

25] reported that

Lachnospiraceae was negatively correlated with the inflammation status. Available evidence suggests that disordered microflora is related to homeostasis in the gut. We observed no significant difference in

Lachnospiraceae_

NK4A136_ group among maternal mice. However, a significant difference was evident in offspring mice fed a diet including high pea fibre compared to dietary fibre-deprived offspring mice. These findings indicate that deprivation of fibre changed the intestinal microflora. The characteristic change was similar to that of intestinal microflora in patients with neuropsychiatric diseases and inflammatory bowel diseases. However, more research is needed for clarification. Pea fibre can improve the composition of the intestinal microflora, with increased contents of SCFA-producing bacteria and cellulose-degrading bacteria. Additionally, some studies have shown that SCFAs can regulate the central nervous system via gastrointestinal hormones, such as leptin and peptide YY, and influence neuropsychiatric and inflammatory diseases through interactions with free fatty acid receptors [

51]. Therefore, nutrients, microflora, and hormones can affect homeostasis.

A recent study indicated that offspring reflect the maternal microbiota via vertical transmission during the perinatal period [

52]. In our study, the gut microbiota among maternal mice was transferred during pregnancy to their offspring. The latter mice in the HDFO and DFDO groups displayed altered gut microbiota. This tendency was similar with the maternal groups, which may have resulted from the consumption of pea fibre. We also observed that dysbacteriosis delivered to offspring of fibre-deprived mice profoundly contributed to neuropsychiatric diseases, consistent with previous studies [

53]. Lin

et al. [

54] reported that supplying tributyrin in late pregnancy and during lactation can improve the faecal microbiota and relative abundance of

Lactobacillus in sows and offspring, and that the

Eubacterium_fissicatena_group decreased in piglets in the tributyrin group. In addition, the maternal gut microbiota can have more lasting effects on the gut microbiota than other sources [

2].