Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material And Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and DNA Extraction

| Lab code | Samples | GPS / Field Tag | Sampling location |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | CA90 positive control | M111111,2 P222973,9 | Sta Comba |

| B | CA90 positive control | M110916,0 P2225509 | Sta Comba |

| C | CA90 positive control | M110932,6 P222509,7 | Sta Comba |

| D | C. Sativa | TD | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 1 | CA90 | T1 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 2 | CA90 | T2 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 3 | CA90 | T3 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 4 | CA90 | T4 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 5 | CA90 | T5 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 6 | CA90 | T6 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 7 | CA90 | T7 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 8 | CA90 | T8 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 9 | CA90 | T9 | Vila-Boa de Serapicos |

| 10 | C. mollissima 60907 | T10 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 11 | C. mollissima E2604 | T11 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 12 | C. mollissima Y0204 | T12 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 13 | C. mollissima Z1408 | T13 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 14 | CA90 | T14 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 15 | Martaínha 2 | T15 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 16 | Bouche de Betizac 1 | T16 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 17 | Bouche de Betizac 2 | T17 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 18 | Martaínha 1 | T18 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 19 | Cota | T19 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 20 | Judia | T20 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 21 | Marsol | T21 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 22 | Précoce Migoule | T22 | Deifil Green Biotechnology |

| 23 | Putative CA90 | M111478,8 P223081,2 | Sta Comba |

| 24 | Putative CA90 | M11609,9 P222967,4 | Sta Comba |

| 25 | Putative CA90 | M111649,4 P222888,7 | Sta Comba |

| 26 | Putative CA90 | M111494,7 P222815,0 | Sta Comba |

| 27 | Putative CA90 | M111497,6 P223077,5 | Sta Comba |

| 28 | Putative CA90 | M111191,6 P222934,5 | Sta Comba |

| 29 | Putative CA90 | M111512,1 P222808,6 | Sta Comba |

| 30 | Putative CA90 | M111486,4 P222934,5 | Sta Comba |

| 31 | Putative CA90 | M111477,6 P222821,3 | Sta Comba |

2.2. SSR Amplification

2.3. Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects on Primer Locus Modification

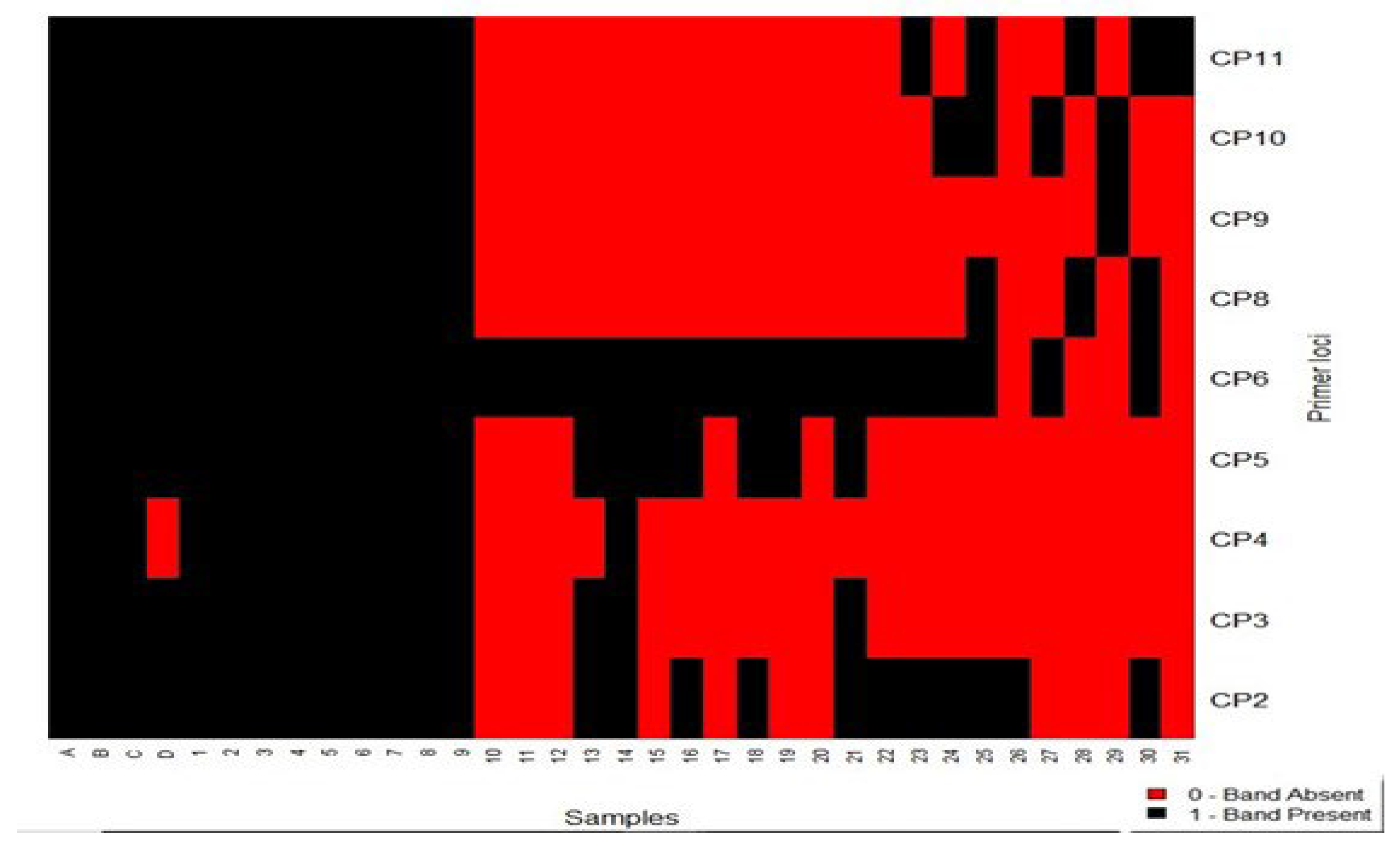

3.2. Locus Amplifications and Band Pattern Representation

3.3. Sequencing Results

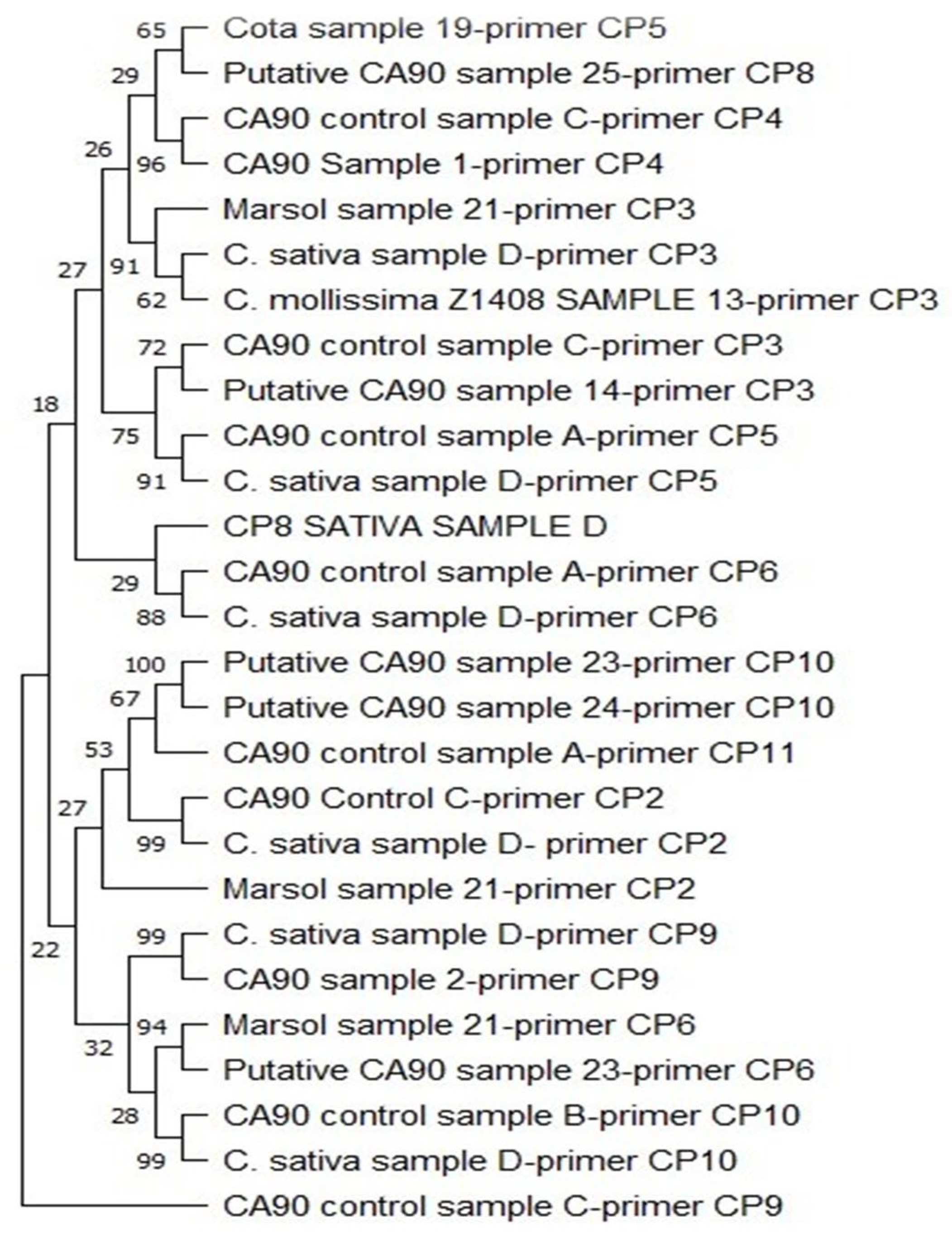

3.4. Phylogenetic Tree Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data availability

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, S.L.; Marcolin, E.; Patrício, M.S.; Loewe-Muñoz, V. A Silvicultural Synthesis of Sweet (Castanea sativa) and American (C. dentata) Chestnuts. For Ecol Manag. 2023, 539, 121041. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.; Freitas, M.; Domínguez-Perles, R.; Barros, A.I.R.N.A.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Igrejas, G. Nutriproteomics Survey of Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Miller) Genetic Resources in Portugal. Food Biosci. 2020, 36, 100622. [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.; Araújo, S. de S.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Portuguese Castanea sativa Genetic Resources: Characterization, Productive Challenges and Breeding Efforts. Agriculture (Switzerland). 2023, 13, 1629.

- Costa, Rita.; Valdiviesso, Teresa.; Marum, Liliana.; Borges, Olga.; Soeiro, José.; Assunção, Augusto.; Soares, F.Matos.; Sequeira, José. Characterisation of Traditional Portuguese Chestnut Cultivars by Nuclear SSRs. Acta Horticulturae. 2005, 693, 437–440. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, T.R.; Santos, J.A.; Silva, A.P.; Fraga, H. Influence of Climate Change on Chestnut Trees: A Review. Plants. 2021, 10, 1463. [CrossRef]

- Rigling, D.; Prospero, S. Cryphonectria Parasitica, the Causal Agent of Chestnut Blight: Invasion History, Population Biology and Disease Control. Mol Plant Pathol 2018, 19, 7–20. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakis, S.L. Chestnut Breeding in the United States for Disease Insect Resistance. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1392–1403. [CrossRef]

- Vannini, A.; Vettraino, A.M. Ink Disease in Chestnuts: Impact on the European Chestnut. For Snow Landsc. 2001, 76, 345-350.

- Burgess, T.I.; Scott, J.K.; Mcdougall, K.L.; Stukely, M.J.C.; Crane, C.; Dunstan, W.A.; Brigg, F.; Andjic, V.; White, D.; Rudman, T.; et al. Current and Projected Global Distribution of Phytophthora cinnamomi, One of the World’s Worst Plant Pathogens. Glob Chang Biol. 2017, 23, 1661–1674.

- Anagnostakis, S.L. Chestnut Blight: The Classical Problem of an Introduced Pathogen1. Mycologia 1987, 79, 23.

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Lourenço Costa, R.; Serdar Ondokuz, U.; Üniversitesi, M.; Ramos-Cabrer, A. Interspecific Hybridization of Chestnut. Polyploidy and Hybridization for Crop Improvement, 1st ed; Annaliese S. M, CRC press, 2016, pp.379-408.

- Santos, C.; Nelson, C.D.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Machado, H.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Costa, R.L. First Interspecific Genetic Linkage Map for Castanea sativa x Castanea crenata Revealed QTLs for Resistance to Phytophthora cinnamomi. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0184381. [CrossRef]

- Serrazina, S.; Santos, C.; Machado, H.; Pesquita, C.; Vicentini, R.; Pais, M.S.; Sebastiana, M.; Costa, R. Castanea Root Transcriptome in Response to Phytophthora cinnamomi Challenge. Tree Genet Genomes. 2015, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hardham, A.R. Phytophthora cinnamomi. Mol Plant Pathol 2005, 6,589-604.

- Boccacci, P.; Akkak, A.; Torello, D.; Bounous, G.; Botta, R. Typing European Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Cultivars Using Oak Simple Sequence Repeat Markers. HortSci. 2004, 39, 1212-1216. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Pereira-Lorenzo, S. Genetic Relationship between Castanea sativa Mill. Trees from North-Western to South Spain Based on Morphological Traits and Isoenzymes. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2005, 52, 879–890. [CrossRef]

- Goulao, L.; Valdiviesso, T.; Santana, C.; Oliveira, C.M. Comparison between Phenetic Characterisation Using RAPD and ISSR Markers and Phenotypic Data of Cultivated Chestnut (Castanea Sativa Mill). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2001, 48, 329-338. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Machado, H.; Serrazina, S.; Gomes, F.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Correia, I.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Duarte, S.; Bragança, H.; Fevereiro, P.; et al. Comprehension of Resistance to Diseases in Chestnut. Revista de Ciências Agrárias. 2016, 39, 189–193. [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Santos, C.; Tavares, F.; Machado, H.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Kubisiak, T.; Nelson, C.D. Mapping and Transcriptomic Approches Implemented for Understanding Disease Resistance to Phytophthora cinammomi in Castanea Sp. BMC Proc. 2011, 5. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.; Tedesco, S.; da Silva, I.V.; Santos, C.; Machado, H.; Costa, R.L. A New Clonal Propagation Protocol Develops Quality Root Systems in Chestnut. Forests. 2020, 11, 826. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Serrazina, S.; Nelson, C.D.; Costa, R. Development and Characterization of EST-SSR Markers for Mapping Reaction to Phytophthora cinnamomi in Castanea spp. Sci Hortic. 2015, 194. [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.A.; Alvarez, J.B.; Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Villani, F.; Martin, L.M. Identification and Characterisation of Traditional Chestnut Varieties of Southern Spain Using Morphological and Simple Sequence Repeat (SSRs) Markers. Annals of Applied Biology .2009, 154, 389–398. [CrossRef]

- Rasoarahona, R.; Wattanadilokchatkun, P.; Panthum, T.; Thong, T.; Singchat, W.; Ahmad, S.F.; Chaiyes, A.; Han, K.; Kraichak, E.; Muangmai, N.; et al. Optimizing Microsatellite Marker Panels for Genetic Diversity and Population Genetic Studies: An Ant Colony Algorithm Approach with Polymorphic Information Content. Biology (Basel). 2023, 12, 1280. [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, D.; Akkak, A.; Bounous, G.; Edwards, K.J.; Botta, R. Development and Characterization of Microsatellite Markers in Castanea sativa (Mill.). Molecular Breeding. 2003, 11, 127-136. [CrossRef]

- Botta, R.; Marinoni, D.; Beccaro, G.; Akkak, A.; Bounous, G.; Development of a DNA Typing Technique for the Genetic Certification of Chestnut Cultivars. For snow Landsc. 2001, 76, 425-428.

- Beier, S.; Thiel, T.; Münch, T.; Scholz, U.; Mascher, M. MISA-Web: A Web Server for Microsatellite Prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017, 33, 2583–2585. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.C.; Lin, H.C.; Huang, M.C.; Li, L.H.; Pan, W.H.; Wu, J.Y.; Chen, Y.T. A New Analysis Tool for Individual-Level Allele Frequency for Genomic Studies. BMC Genomics. 2010, 11, 415. [CrossRef]

- Dinis, L.-T.J.; Peixoto, F.; Costa, R.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Molecular Characterization of “Judia” (Castanea sativa Mill.) from Several Trás-Os-Montes Regions by Nuclear Microsatellite Markers. Acta Horticul. 2010, 866, 225-232.

- Bodénès, C.; Chancerel, E.; Gailing, O.; Vendramin, G. G.; Bagnoli, F.; Durand, J. Comparative mapping in the Fagaceae and beyond with EST-SSRs. BMC plant biology. 2012, 12, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Barreneche, T.; Casasoli, M.; Russell, K.; Akkak, A.; Meddour, H.; Plomion, C.; Villani, F.; Kremer, A. Comparative Mapping between Quercus and Castanea Using Simple-Sequence Repeats (SSRs). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2004, 108, 558–566. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the Number of Nucleotide Substitutions in the Control Region of Mitochondrial DNA in Humans and Chimpanzees. 1993, Molecular Bio and Evol. [CrossRef]

| NO | loci | Forward (5’-3’) | Reverse (5’-3’) | Size (bp) | Annealing Tm (℃) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CP2 | AGTTCTCCACGAGGCTCAAA | TCCAAGCTGGAGAATCATCA | 220 | 55.3 |

| 2 | CP3 | GGTGCCCAGATTTACGAGAA | ATCGCTTGGAGTCACAGCTT | 240 | 57.3 |

| 3 | CP4 | GCTGCTTCACAACCTTCCTC | GCAAGAGATTCCCTTTGCTG | 220 | 57.3 |

| 4 | CP5 | ACACATGGGGGTGTGAACTT | TTATGGGAAACGGCATCTTC | 125 | 55.3 |

| 5 | CP6 | CCTGTGAGGCTAAGAGAGCG | ACCACGTCGGTGCTTCTAGT | 200 | 59.4 |

| 6 | CP8 | TCGTCCCCTTCTTCATCATC | ATATGGCCAAAAACCCATCA | 250 | 53.2 |

| 7 | CP9 | TTCCACCCAATTGTTACCAC | GATGAAGAAGGGGACGA | 200 | 55.3 |

| 8 | CP10 | ATCCATGAGTGAAAGCCACC | TGGAACAAGAAGCCTCGATT | 250 | 55.6 |

| 9 | CP11 | TCATCCAAGAAGCCCTCAAC | TTCTGCCTCTTTTGTTGCCT | 230 | 55.3 |

| Loci | Sample | Na | Motif | Reference | Loci | Na | Motif | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cp2 | Marsol | 1 | (GTG)9 | This study | CcPT 0002 | 1 | (GTG)9 | [21]. |

| Cp2 | CA90 | * | This study | |||||

| Cp2 | C. sativa | * | This study | |||||

| Cp3 | Marsol | 3 | (ATC)6 | This study | CcPT 0003 | 7 | (ATC)8 | [21]. |

| Cp3 | C. sativa | (ATC)6 | This study | |||||

| Cp3 | C. mollissima. Z1408 | (ATC)6 | This study | |||||

| Cp3 | CA90 | (TGA)5tcatgatgaccacaaggattgaagttagtcacagcatctcggccaccaacgcgttgggccgcgatgtcgtacgcttttgca (TCT)5 | This study | |||||

| Cp3 | Martainha | (TGA)8tcatcagtaccacccggcgggttgaagttcacaacatcttctccaccacaaaagcggggggccatgatgtcatattttgttg (CTT)5 | This study | |||||

| Cp4 | CA90 | 2 | (GA)10 | This study | CcPT 0004 | 6 | (CT)10 | [21]. |

| Cp4 | CA90 | (GA)11 | This study | |||||

| Cp5 | CA90 | 3 | (CT)8 | This study | CcPT 0005 | 7 | (CT)1 | [21]. |

| Cp5 | C. sativa | (CT)12 | This study | |||||

| Cp5 | COTA | (AG)7 | This study | |||||

| Cp6 | Marsol | 2 | (GAA)5 | This study | CcPT 0006 | 4 | (TTC) | [21]. |

| Cp6 | CA90 | (GAA)5 gaggaagaagaac(A)12 | This study | |||||

| Cp6 | CA90 | * | This study | |||||

| Cp6 | C. sativa | * | This study | |||||

| Cp8 | C. sativa | 2 | (CTCAGA)5 gtacaacaaccgacagca (AAG)11 | This study | CcPT 0008 | 5 | (TCT)1 | [21]. |

| Cp8 | CA90 | (A)12 (TCT)8 | This study | |||||

| Cp9 | CA90 | 2 | (AG)10 | This study | CcPT 0009 | 8 | (TC) | [21]. |

| Cp9 | C. sativa | (TC)8 | This study | |||||

| Cp9 | CA90 | * | This study | |||||

| Cp10 | CA90 | 2 | (CAC)6 (AAG)5 | This study | CcPT 0010 | 5 | (GGT) | [21]. |

| Cp10 | C. sativa | (CAC)6 (AAG)5 | This study | |||||

| Cp10 | CA90 | (GGT)5 gggggagccttc (TCT)6 | This study | |||||

| Cp10 | CA90 | (GGT)5 gggggagccttc (TCT)6 | This study | |||||

| Cp11 | CA90 | 1 | (GGT)7 | This study | CcPT 0011 | 5 | (CAC) | [21]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).