Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

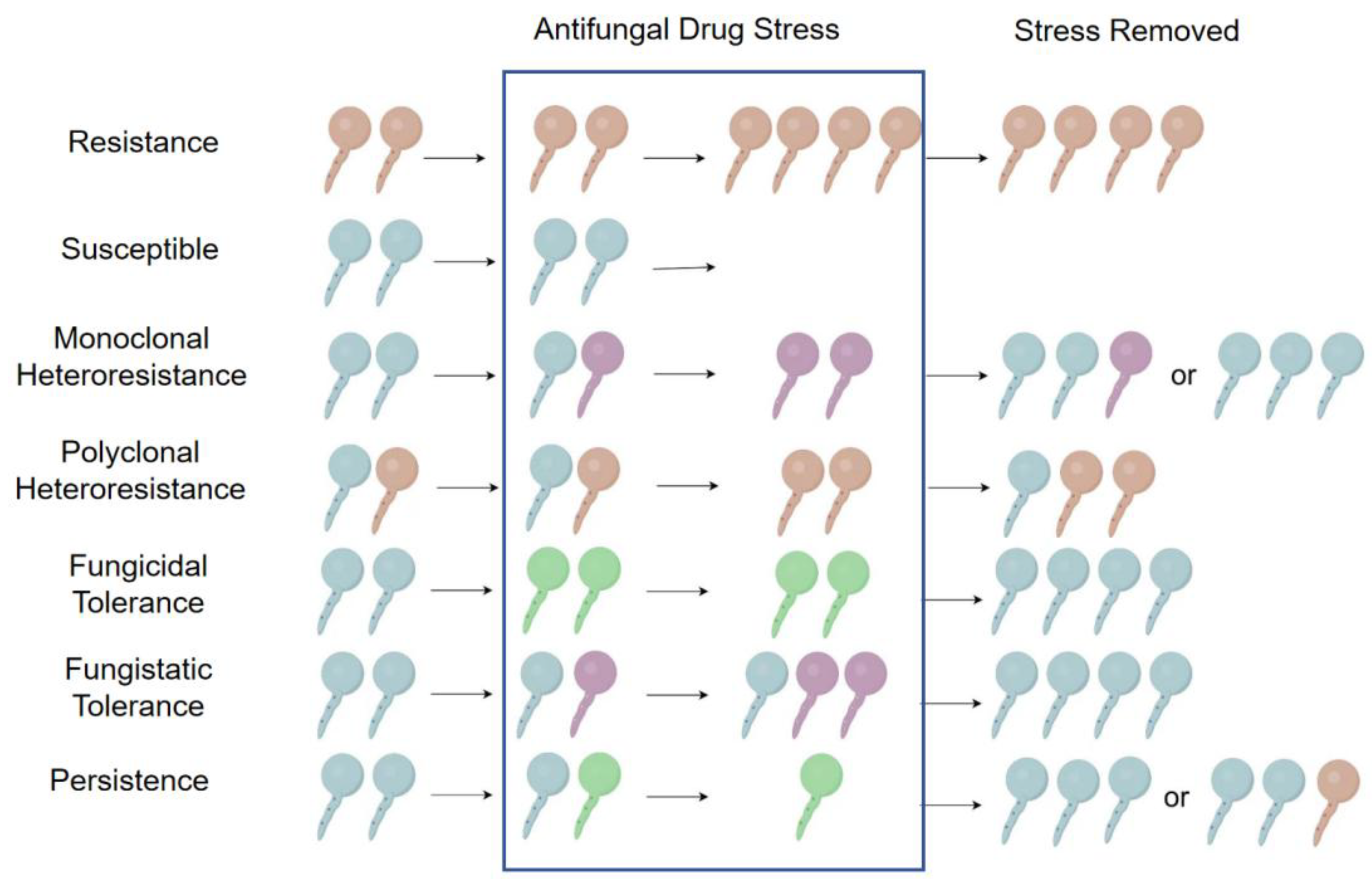

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Antifungal Drugs

3. Heteroresistance, Tolerance and Persistence of Antifungal Drugs

4. Mechanisms of Antifungal Tolerance

5. Mechanisms of Antifungal Persistence

6. Mechanisms of Antifungal Heteroresistance

5.1. Aneuploidy and Copy Number Variations (CNVs)

6.1.1. C. albicans

6.1.2. C. glabrata

6.1.3. C. parapsilosis

6.1.4. C. auris

6.1.5. C. neoformans and C. gattii

6.2. Alterations in Gene Expression

6.3. Environmental Stress Induction

| Types | Species | Antifungals | Mechanisms | Related Components | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aneuploidy and CNVs | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Chr5 disomy | ERG11 and TAC1 | [104,110] |

| C. albicans | 5-Flucytosine | Loss of chr5, due to the location of negative regulator (s) of anti 5-FC | None. | [110] | |

| C. albicans | Fluconazole | “Trimeras,” three connected cells composed of a mother, daughter, and granddaughter bud | None | [112] | |

| C. albicans | Echinocandins | Chr2 trisomy | RNR1, RNR21 | [113] | |

| C. albicans | Echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin and anidulafungin) | Chr5 aneuploidy after caspofungin exposure can obtain cross-resistance | Three negative regulators CHT2, PGA4 and CSU51, and two positive regulators, CNB1 and MID1. | [88,114] | |

| C. glabrata | Echinocandins (anidulafungin) |

ChrE aneuploidy contributes to heteroresistance after exposing clinical isolates to anidulafungin. | None | [116] | |

| C. glabrata | Azoles | Incremental effects of these multiple binary genetic switches | CDR1, PDH1, PDR1 and SNQ1 | [67] | |

| C. glabrata | Azoles | Formation of “trimeras” | None | [112] | |

| C. parapsilosis | Azoles | Formation of “trimeras” | None | [112] | |

| C. auris | Azoles (fluconazole) |

Genome changes mainly composed of SNP, with a minority of aneuploidy. But due to its haploid genome, SNPs may have immediate phenotypic impact. | SNPs | [109,117,118] | |

| C. neoformans | Cross-resistance to 5-FC and Fluconazole | Chr1 disomy | ERG11, AFR1 | [106] | |

| C. neoformans | Fluconazole | Overexpression of AFR1 on chr1 and GEA2 on chr3 | AFR1, GEA2 | [106] | |

| C. neoformans | Azoles (fluconazole) |

Titan cells that produce multiple types of aneuploid daughter cells | None | [123,124,125] | |

| C. neoformans | Azoles (fluconazole) |

Chr1 disomy | ERG11, AFR1 | [126] | |

| C. neoformans | Azoles (fluconazole) |

Chr4 disomy | SEY1, GCS2, GLO3 | [128] | |

| C. neoformans | Azoles (fluconazole) |

Chr3 disomy caused by gene relocation | ERG11, SEY1, GCS2, GLO3 | [128,129] | |

| Alterations in Gene Expression | C. albicans | Azoles | Elevation of mRNA | ATP Binding Cassette superfamily CDR genes | [107] |

| C. neoformans | Azoles (fluconazole) |

Up-regulated activity of efflux pumps | AFR1 | [126] | |

| Environmental Stress | C. neoformans | Polyene (AMB) and Azoles (fluconazole) | Nitrogen limitation | None | [70] |

| C. neoformans | Azoles | Temperature, media type, growth phase, and the age of cells | None | [122] |

7. Clinical Relevance of Antifungal Heteroresistance

7.1. Outcomes of Antifungal Heteroresistance

7.2. Diagnosis of Antifungal Heteroresistance

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| CNVs | Copy Number Variations |

| AmB | Amphotericin B |

| 5-FC | 5-fluorocytosine |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| MDK99 | Minimum Duration of Killing 99% |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutases |

| chr | Chromosome |

| GPI | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol |

| PAP | Population Analysis Profile |

| scRNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polyphorism |

| ABC | ATP-Binding Cassette |

References

- Spallone, A. and I.S. Schwartz, Emerging Fungal Infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2021. 35(2): p. 261-277. [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, S.R. and J. Guarner, Emerging and reemerging fungal infections. Semin Diagn Pathol, 2019. 36(3): p. 177-181. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C., et al., Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science, 2018. 360(6390): p. 739-742. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, H.E. and G. Leidy, Mode of action of streptomycin on type b Hemophilus influenzae: II. Nature of resistant variants. The Journal of experimental medicine, 1947. 85(6): p. 607. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C., et al., Mixed Infections and Rifampin Heteroresistance among Mycobacterium tuberculosis Clinical Isolates. J Clin Microbiol, 2015. 53(7): p. 2138-47. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., et al., Within patient microevolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis correlates with heterogeneous responses to treatment. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 17507. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, D.I., H. Nicoloff, and K. Hjort, Mechanisms and clinical relevance of bacterial heteroresistance. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2019. 17(8): p. 479-496. [CrossRef]

- Kon, H., et al., Prevalence and Clinical Consequences of Colistin Heteroresistance and Evolution into Full Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbiol Spectr, 2023. 11(3): p. e0509322. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., et al., Mechanisms of Heteroresistance and Resistance to Imipenem in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Drug Resist, 2020. 13: p. 1419-1428. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.R., et al., Pseudomonas aeruginosa heteroresistance to levofloxacin caused by upregulated expression of essential genes for DNA replication and repair. Front Microbiol, 2022. 13: p. 1105921. [CrossRef]

- Cherkaoui, A., et al., Imipenem heteroresistance in nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae is linked to a combination of altered PBP3, slow drug influx and direct efflux regulation. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2017. 23(2): p. 118.e9-118.e19. [CrossRef]

- Adams-Sapper, S., A. Gayoso, and L.W. Riley, Stress-Adaptive Responses Associated with High-Level Carbapenem Resistance in KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Pathog, 2018. 2018: p. 3028290. [CrossRef]

- Fukuzawa, S., et al., High prevalence of colistin heteroresistance in specific species and lineages of Enterobacter cloacae complex derived from human clinical specimens. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2023. 22(1): p. 60. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y., et al., Impact of Carbapenem Heteroresistance Among Multidrug-Resistant ESBL/AmpC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates on Antibiotic Treatment in Experimentally Infected Mice. Infect Drug Resist, 2021. 14: p. 5639-5650. [CrossRef]

- Kotilea, K., et al., Antibiotic resistance, heteroresistance, and eradication success of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Helicobacter, 2023. 28(5): p. e13006. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., et al., Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae exhibiting clinically undetected amikacin and meropenem heteroresistance leads to treatment failure in a murine model of infection. Microb Pathog, 2021. 160: p. 105162. [CrossRef]

- Kargarpour Kamakoli, M., et al., Evaluation of the impact of polyclonal infection and heteroresistance on treatment of tuberculosis patients. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 41410. [CrossRef]

- Gautier, C., E.I. Maciel, and I.V. Ene, Approaches for identifying and measuring heteroresistance in azole-susceptible Candida isolates. Microbiol Spectr, 2024. 12(4): p. e0404123. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B., et al., Antifungal heteroresistance causes prophylaxis failure and facilitates breakthrough Candida parapsilosis infections. Nat Med, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ponde, N.O., et al., Candida albicans biofilms and polymicrobial interactions. Crit Rev Microbiol, 2021. 47(1): p. 91-111. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S., et al., Candida auris and Nosocomial Infection. Curr Drug Targets, 2020. 21(4): p. 365-373. [CrossRef]

- Geremia, N., et al., Candida auris as an Emergent Public Health Problem: A Current Update on European Outbreaks and Cases. Healthcare (Basel), 2023. 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Lyman, M., et al., Worsening Spread of Candida auris in the United States, 2019 to 2021. Ann Intern Med, 2023. 176(4): p. 489-495. [CrossRef]

- Bing, J., et al., Candida auris-associated hospitalizations and outbreaks, China, 2018-2023. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2024. 13(1): p. 2302843. [CrossRef]

- Devrim, İ., et al., Outcome of Candida Parapsilosis Complex Infections Treated with Caspofungin in Children. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 2016. 8(1): p. e2016042. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C. and K.J. Kwon-Chung, Complementation of a capsule-deficient mutation of Cryptococcus neoformans restores its virulence. Mol Cell Biol, 1994. 14(7): p. 4912-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, O.W., et al., Systematic genetic analysis of virulence in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell, 2008. 135(1): p. 174-88. [CrossRef]

- Janbon, G., et al., Cas1p is a membrane protein necessary for the O-acetylation of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Mol Microbiol, 2001. 42(2): p. 453-67. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.F., et al., Clinical and pathological characterization of Central Nervous System cryptococcosis in an experimental mouse model of stereotaxic intracerebral infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2023. 17(1): p. e0011068. [CrossRef]

- Imanishi-Shimizu, Y., et al., A capsule-associated gene of Cryptococcus neoformans, CAP64, is involved in pH homeostasis. Microbiology (Reading), 2021. 167(6). [CrossRef]

- Araújo, G.R.S., et al., Ultrastructural Study of Cryptococcus neoformans Surface During Budding Events. Front Microbiol, 2021. 12: p. 609244. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, H.R., et al., Faster Cryptococcus Melanization Increases Virulence in Experimental and Human Cryptococcosis. J Fungi (Basel), 2022. 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Erives, V.H., et al., Methamphetamine Enhances Cryptococcus neoformans Melanization, Antifungal Resistance, and Pathogenesis in a Murine Model of Drug Administration and Systemic Infection. Infect Immun, 2022. 90(4): p. e0009122. [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.P. and A. Casadevall, Reciprocal modulation of ammonia and melanin production has implications for cryptococcal virulence. Nat Commun, 2023. 14(1): p. 849. [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.J., et al., Cryptococcal phospholipase B1 is required for intracellular proliferation and control of titan cell morphology during macrophage infection. Infect Immun, 2015. 83(4): p. 1296-304. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.F., et al., Phospholipase B Is Critical for Cryptococcus neoformans Survival in the Central Nervous System. mBio, 2023. 14(2): p. e0264022. [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, R., et al., Role of extracellular phospholipases and mononuclear phagocytes in dissemination of cryptococcosis in a murine model. Infect Immun, 2004. 72(4): p. 2229-39. [CrossRef]

- Goich, D., et al., Gcn2 rescues reprogramming in the absence of Hog1/p38 signaling in C. neoformans during thermal stress. bioRxiv, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, B.J., et al., Discovery of CO(2) tolerance genes associated with virulence in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat Microbiol, 2024. [CrossRef]

- van de Veerdonk, F.L., et al., Aspergillus fumigatus morphology and dynamic host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2017. 15(11): p. 661-674. [CrossRef]

- Odds, F.C., S.L. Cheesman, and A.B. Abbott, Suppression of ATP in Candida albicans by imidazole and derivative antifungal agents. Sabouraudia, 1985. 23(6): p. 415-24.

- Saag, M.S. and W.E. Dismukes, Azole antifungal agents: emphasis on new triazoles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1988. 32(1): p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Patil, A. and S. Majumdar, Echinocandins in antifungal pharmacotherapy. J Pharm Pharmacol, 2017. 69(12): p. 1635-1660. [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Arango, A.C., L. Scorzoni, and O. Zaragoza, It only takes one to do many jobs: Amphotericin B as antifungal and immunomodulatory drug. Front Microbiol, 2012. 3: p. 286. [CrossRef]

- Shivarathri, R., et al., Comparative Transcriptomics Reveal Possible Mechanisms of Amphotericin B Resistance in Candida auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2022. 66(6): p. e0227621. [CrossRef]

- Perlin, D.S., R. Rautemaa-Richardson, and A. Alastruey-Izquierdo, The global problem of antifungal resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect Dis, 2017. 17(12): p. e383-e392. [CrossRef]

- Polak, A. and H.J. Scholer, Mode of action of 5-fluorocytosine and mechanisms of resistance. Chemotherapy, 1975. 21(3-4): p. 113-30. [CrossRef]

- Gleason, M.K. and H. Fraenkel-Conrat, Biological consequences of incorporation of 5-fluorocytidine in the RNA of 5-fluorouracil-treated eukaryotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1976. 73(5): p. 1528-31. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.E., et al., Candida auris Pan-Drug-Resistant to Four Classes of Antifungal Agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2022. 66(7): p. e0005322. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.K., et al., Novel ABC Transporter Associated with Fluconazole Resistance in Aging of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Fungi (Basel), 2022. 8(7). [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.R., et al., Molecular mechanisms of acquired antifungal drug resistance in principal fungal pathogens and EUCAST guidance for their laboratory detection and clinical implications. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2022. 77(8): p. 2053-2073. [CrossRef]

- Štefánek, M., et al., Comparative Analysis of Two Candida parapsilosis Isolates Originating from the Same Patient Harbouring the Y132F and R398I Mutations in the ERG11 Gene. Cells, 2023. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Pristov, K.E. and M.A. Ghannoum, Resistance of Candida to azoles and echinocandins worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2019. 25(7): p. 792-798. [CrossRef]

- Fattouh, N., et al., Molecular mechanism of fluconazole resistance and pathogenicity attributes of Lebanese Candida albicans hospital isolates. Fungal Genet Biol, 2021. 153: p. 103575. [CrossRef]

- Bosco-Borgeat, M.E., et al., Amino acid substitution in Cryptococcus neoformans lanosterol 14-α-demethylase involved in fluconazole resistance in clinical isolates. Rev Argent Microbiol, 2016. 48(2): p. 137-42. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Guerra, T.M., et al., A point mutation in the 14alpha-sterol demethylase gene cyp51A contributes to itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2003. 47(3): p. 1120-4. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Effron, G., et al., A naturally occurring proline-to-alanine amino acid change in Fks1p in Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis accounts for reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2008. 52(7): p. 2305-12. [CrossRef]

- Healey, K.R. and D.S. Perlin, Fungal Resistance to Echinocandins and the MDR Phenomenon in Candida glabrata. J Fungi (Basel), 2018. 4(3). [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.J., Y.L. Chang, and Y.L. Chen, Deletion of ADA2 Increases Antifungal Drug Susceptibility and Virulence in Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2018. 62(3). [CrossRef]

- Singh-Babak, S.D., et al., Global analysis of the evolution and mechanism of echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata. PLoS Pathog, 2012. 8(5): p. e1002718. [CrossRef]

- Delma, F.Z., et al., Molecular Mechanisms of 5-Fluorocytosine Resistance in Yeasts and Filamentous Fungi. J Fungi (Basel), 2021. 7(11). [CrossRef]

- Kannan, A., et al., Comparative Genomics for the Elucidation of Multidrug Resistance in Candida lusitaniae. mBio, 2019. 10(6). [CrossRef]

- Billmyre, R.B., et al., 5-fluorocytosine resistance is associated with hypermutation and alterations in capsule biosynthesis in Cryptococcus. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 127. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.N., et al., Unmasking the Amphotericin B Resistance Mechanisms in Candida haemulonii Species Complex. ACS Infect Dis, 2020. 6(5): p. 1273-1282. [CrossRef]

- Schatzman, S.S., et al., Copper-only superoxide dismutase enzymes and iron starvation stress in Candida fungal pathogens. J Biol Chem, 2020. 295(2): p. 570-583. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., et al., Insight into Virulence and Mechanisms of Amphotericin B Resistance in the Candida haemulonii Complex. J Fungi (Basel), 2024. 10(9). [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ami, R., et al., Heteroresistance to Fluconazole Is a Continuously Distributed Phenotype among Candida glabrata Clinical Strains Associated with In Vivo Persistence. mBio, 2016. 7(4). [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.F., N. Ziv, and M.L. Siegal, Bet hedging in yeast by heterogeneous, age-correlated expression of a stress protectant. PLoS Biol, 2012. 10(5): p. e1001325. [CrossRef]

- Claudino, A.L., et al., Mutants with heteroresistance to amphotericin B and fluconazole in Candida. Braz J Microbiol, 2009. 40(4): p. 943-51. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, C., et al., Nitrogen concentration affects amphotericin B and fluconazole tolerance of pathogenic cryptococci. FEMS Yeast Res, 2020. 20(2). [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.F., et al., Heteroresistance to Itraconazole Alters the Morphology and Increases the Virulence of Cryptococcus gattii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2015. 59(8): p. 4600-9. [CrossRef]

- Sionov, E., et al., Heteroresistance to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans is intrinsic and associated with virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2009. 53(7): p. 2804-15. [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.Q., et al., Publisher Correction: Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2019. 17(7): p. 460. [CrossRef]

- Kester, J.C. and S.M. Fortune, Persisters and beyond: mechanisms of phenotypic drug resistance and drug tolerance in bacteria. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 2014. 49(2): p. 91-101. [CrossRef]

- Berman, J. and D.J. Krysan, Drug resistance and tolerance in fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2020. 18(6): p. 319-331. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., et al., Confronting antifungal resistance, tolerance, and persistence: Advances in drug target discovery and delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2023. 200: p. 115007. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, N. and J. Berman, Protocols for Measuring Tolerant and Heteroresistant Drug Responses of Pathogenic Yeasts. Methods Mol Biol, 2023. 2658: p. 67-79. [CrossRef]

- Rasouli Koohi, S., et al., Identification and Elimination of Antifungal Tolerance in Candida auris. Biomedicines, 2023. 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A., et al., Antifungal tolerance is a subpopulation effect distinct from resistance and is associated with persistent candidemia. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 2470. [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, A.L., J.A. Rycroft, and S. Helaine, Impact of bacterial persisters on their host. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2021. 59: p. 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Arastehfar, A., et al., Macrophage internalization creates a multidrug-tolerant fungal persister reservoir and facilitates the emergence of drug resistance. Nat Commun, 2023. 14(1): p. 1183. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K., Persister cells. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2010. 64: p. 357-72. [CrossRef]

- Ke, W., et al., Fungicide-tolerant persister formation during cryptococcal pulmonary infection. Cell Host Microbe, 2024. 32(2): p. 276-289.e7. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al., Antifungal Tolerance and Resistance Emerge at Distinct Drug Concentrations and Rely upon Different Aneuploid Chromosomes. mBio, 2023. 14(2): p. e0022723. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al., Tunicamycin Potentiates Antifungal Drug Tolerance via Aneuploidy in Candida albicans. mBio, 2021. 12(4): p. e0227221. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., et al., Brain glucose induces tolerance of Cryptococcus neoformans to amphotericin B during meningitis. Nat Microbiol, 2024. 9(2): p. 346-358. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K., et al., With age comes resilience: how mitochondrial modulation drives age-associated fluconazole tolerance in Cryptococcus neoformans. mBio, 2024. 15(9): p. e0184724. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al., Tolerance to Caspofungin in Candida albicans Is Associated with at Least Three Distinctive Mechanisms That Govern Expression of FKS Genes and Cell Wall Remodeling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017. 61(5). [CrossRef]

- Prasetyoputri, A., et al., The Eagle Effect and Antibiotic-Induced Persistence: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Trends Microbiol, 2019. 27(4): p. 339-354. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.D., et al., Hsp90 governs echinocandin resistance in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans via calcineurin. PLoS Pathog, 2009. 5(7): p. e1000532. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, K.R., N. Robbins, and L.E. Cowen, The role of Candida albicans stress response pathways in antifungal tolerance and resistance. iScience, 2022. 25(3): p. 103953. [CrossRef]

- Dumeaux, V., et al., Candida albicans exhibits heterogeneous and adaptive cytoprotective responses to antifungal compounds. Elife, 2023. 12. [CrossRef]

- Defraine, V., M. Fauvart, and J. Michiels, Fighting bacterial persistence: Current and emerging anti-persister strategies and therapeutics. Drug Resist Updat, 2018. 38: p. 12-26. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K., Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2007. 5(1): p. 48-56. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.A., et al., Oxidative Imbalance in Candida tropicalis Biofilms and Its Relation With Persister Cells. Front Microbiol, 2020. 11: p. 598834. [CrossRef]

- Dasilva, M.A., et al., Synergistic activity of gold nanoparticles with amphotericin B on persister cells of Candida tropicalis biofilms. J Nanobiotechnology, 2024. 22(1): p. 254. [CrossRef]

- El Meouche, I., et al., Drug tolerance and persistence in bacteria, fungi and cancer cells: Role of non-genetic heterogeneity. Transl Oncol, 2024. 49: p. 102069. [CrossRef]

- Zou, P., et al., Antifungal Activity, Synergism with Fluconazole or Amphotericin B and Potential Mechanism of Direct Current against Candida albicans Biofilms and Persisters. Antibiotics (Basel), 2024. 13(6). [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y., et al., Copy number variants of ERG11: mechanism of azole resistance in Candida parapsilosis. Lancet Microbe, 2024. 5(1): p. e10. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X., et al., Tandem gene duplications contributed to high-level azole resistance in a rapidly expanding Candida tropicalis population. Nat Commun, 2023. 14(1): p. 8369. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.J. and A. Nelliat, A Double-Edged Sword: Aneuploidy is a Prevalent Strategy in Fungal Adaptation. Genes (Basel), 2019. 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Vande Zande, P., X. Zhou, and A. Selmecki, The Dynamic Fungal Genome: Polyploidy, Aneuploidy and Copy Number Variation in Response to Stress. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2023. 77: p. 341-361. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al., Adaptation to Fluconazole via Aneuploidy Enables Cross-Adaptation to Amphotericin B and Flucytosine in Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiol Spectr, 2021. 9(2): p. e0072321. [CrossRef]

- Selmecki, A., A. Forche, and J. Berman, Aneuploidy and isochromosome formation in drug-resistant Candida albicans. Science, 2006. 313(5785): p. 367-70. [CrossRef]

- Gohar, A.A., et al., Expression Patterns of ABC Transporter Genes in Fluconazole-Resistant Candida glabrata. Mycopathologia, 2017. 182(3-4): p. 273-284. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H., et al., Aneuploidy underlies brefeldin A-induced antifungal drug resistance in Cryptococcus neoformans. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2024. 14: p. 1397724. [CrossRef]

- Marr, K.A., et al., Rapid, transient fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans is associated with increased mRNA levels of CDR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1998. 42(10): p. 2584-9. [CrossRef]

- Beach, R.R., et al., Aneuploidy Causes Non-genetic Individuality. Cell, 2017. 169(2): p. 229-242.e21. [CrossRef]

- Todd, R.T. and A. Selmecki, Expandable and reversible copy number amplification drives rapid adaptation to antifungal drugs. Elife, 2020. 9. [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.K., J.J. Hayes, and E. Rustchenko, The role of aneuploidy in the emergence of echinocandin resistance in human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog, 2021. 17(5): p. e1009564. [CrossRef]

- Coste, A.T., et al., TAC1, transcriptional activator of CDR genes, is a new transcription factor involved in the regulation of Candida albicans ABC transporters CDR1 and CDR2. Eukaryot Cell, 2004. 3(6): p. 1639-52. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B.D., et al., A tetraploid intermediate precedes aneuploid formation in yeasts exposed to fluconazole. PLoS Biol, 2014. 12(3): p. e1001815. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al., Aneuploidy Enables Cross-Adaptation to Unrelated Drugs. Mol Biol Evol, 2019. 36(8): p. 1768-1782. [CrossRef]

- Husain, F., et al., Candida albicans Strains Adapted to Caspofungin Due to Aneuploidy Become Highly Tolerant under Continued Drug Pressure. Microorganisms, 2022. 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q., et al., Ploidy Variation and Spontaneous Haploid-Diploid Switching of Candida glabrata Clinical Isolates. mSphere, 2022. 7(4): p. e0026022. [CrossRef]

- Ksiezopolska, E., et al., Long-term stability of acquired drug resistance and resistance associated mutations in the fungal pathogen Nakaseomyces glabratus (Candida glabrata). Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2024. 14: p. 1416509. [CrossRef]

- Burrack, L.S., et al., Genomic Diversity across Candida auris Clinical Isolates Shapes Rapid Development of Antifungal Resistance In Vitro and In Vivo. mBio, 2022. 13(4): p. e0084222. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.B., C. Sirjusingh, and N. Ricker, Haploidy, diploidy and evolution of antifungal drug resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 2004. 168(4): p. 1915-23. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, I.M.B., et al., Investigation of fluconazole heteroresistance in clinical and environmental isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans complex and Cryptococcus gattii complex in the state of Amazonas, Brazil. Med Mycol, 2022. 60(3). [CrossRef]

- Yamazumi, T., et al., Characterization of heteroresistance to fluconazole among clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Clin Microbiol, 2003. 41(1): p. 267-72. [CrossRef]

- Varma, A. and K.J. Kwon-Chung, Heteroresistance of Cryptococcus gattii to fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2010. 54(6): p. 2303-11. [CrossRef]

- Altamirano, S., C. Simmons, and L. Kozubowski, Colony and Single Cell Level Analysis of the Heterogeneous Response of Cryptococcus neoformans to Fluconazole. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2018. 8: p. 203. [CrossRef]

- Cao, C., et al., Ubiquitin proteolysis of a CDK-related kinase regulates titan cell formation and virulence in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 6397. [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, A.C., et al., Polyploid titan cells produce haploid and aneuploid progeny to promote stress adaptation. mBio, 2015. 6(5): p. e01340-15. [CrossRef]

- García-Barbazán, I., et al., Accumulation of endogenous free radicals is required to induce titan-like cell formation in Cryptococcus neoformans. mBio, 2024. 15(1): p. e0254923. [CrossRef]

- Stone, N.R., et al., Dynamic ploidy changes drive fluconazole resistance in human cryptococcal meningitis. J Clin Invest, 2019. 129(3): p. 999-1014. [CrossRef]

- Sionov, E., Y.C. Chang, and K.J. Kwon-Chung, Azole heteroresistance in Cryptococcus neoformans: emergence of resistant clones with chromosomal disomy in the mouse brain during fluconazole treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2013. 57(10): p. 5127-30. [CrossRef]

- Ngamskulrungroj, P., et al., Characterization of the chromosome 4 genes that affect fluconazole-induced disomy formation in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS One, 2012. 7(3): p. e33022. [CrossRef]

- Sionov, E., et al., Cryptococcus neoformans overcomes stress of azole drugs by formation of disomy in specific multiple chromosomes. PLoS Pathog, 2010. 6(4): p. e1000848. [CrossRef]

- Altamirano, S., et al., Fluconazole-Induced Ploidy Change in Cryptococcus neoformans Results from the Uncoupling of Cell Growth and Nuclear Division. mSphere, 2017. 2(3). [CrossRef]

- Escribano, P., et al., In vitro acquisition of secondary azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates after prolonged exposure to itraconazole: presence of heteroresistant populations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2012. 56(1): p. 174-8. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., et al., Lesion Heterogeneity and Long-Term Heteroresistance in Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. J Infect Dis, 2021. 224(5): p. 889-893. [CrossRef]

- Hope, W., et al., Fluconazole Monotherapy Is a Suboptimal Option for Initial Treatment of Cryptococcal Meningitis Because of Emergence of Resistance. mBio, 2019. 10(6). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T., et al., Comparative evaluation of colistin broth disc elution (CBDE) and broth microdilution (BMD) in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with special reference to heteroresistance. Indian J Med Microbiol, 2024. 47: p. 100494. [CrossRef]

- El-Halfawy, O.M. and M.A. Valvano, Antimicrobial heteroresistance: an emerging field in need of clarity. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2015. 28(1): p. 191-207. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., et al., Single-Cell Phenotypic Analysis and Digital Molecular Detection Linkable by a Hydrogel Bead-Based Platform. ACS Appl Bio Mater, 2021. 4(3): p. 2664-2674. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., et al., Plasmonic Colloidosome-Coupled MALDI-TOF MS for Bacterial Heteroresistance Study at Single-Cell Level. Anal Chem, 2020. 92(12): p. 8051-8057. [CrossRef]

- Mezcord, V., et al., Induced Heteroresistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) via Exposure to Human Pleural Fluid (HPF) and Its Impact on Cefiderocol Susceptibility. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(14). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Heteroresistance Is Associated With in vitro Regrowth During Colistin Treatment in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol, 2022. 13: p. 868991. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., et al., Combined effect of Polymyxin B and Tigecycline to overcome Heteroresistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol Spectr, 2021. 9(2): p. e0015221. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).