Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.2. Methodology

-

The inverse of the operation can be generalized as for all natural numbers n. This step accounts for the fact that the operation in Equation 1 yields both even and odd integers.

- For example, in Equation 1, if , the next number in the sequence is 5 and if , the next number in the sequence is 4. This demonstrates that the operation can yield both odd and even numbers.

- In the inverse transformation, both even and odd numbers must be multiplied by 2 to account for this behavior. For instance, if , the next number in the sequence under the inverse transformation is 10. Likewise, if , the next number is 8.

-

The inverse of the operation can be expressed as for all even integers n where is divisible by 3.

- –

- For example, 5 maps to 16 under the operation (since ), and conversely, 16 maps to 5 using .

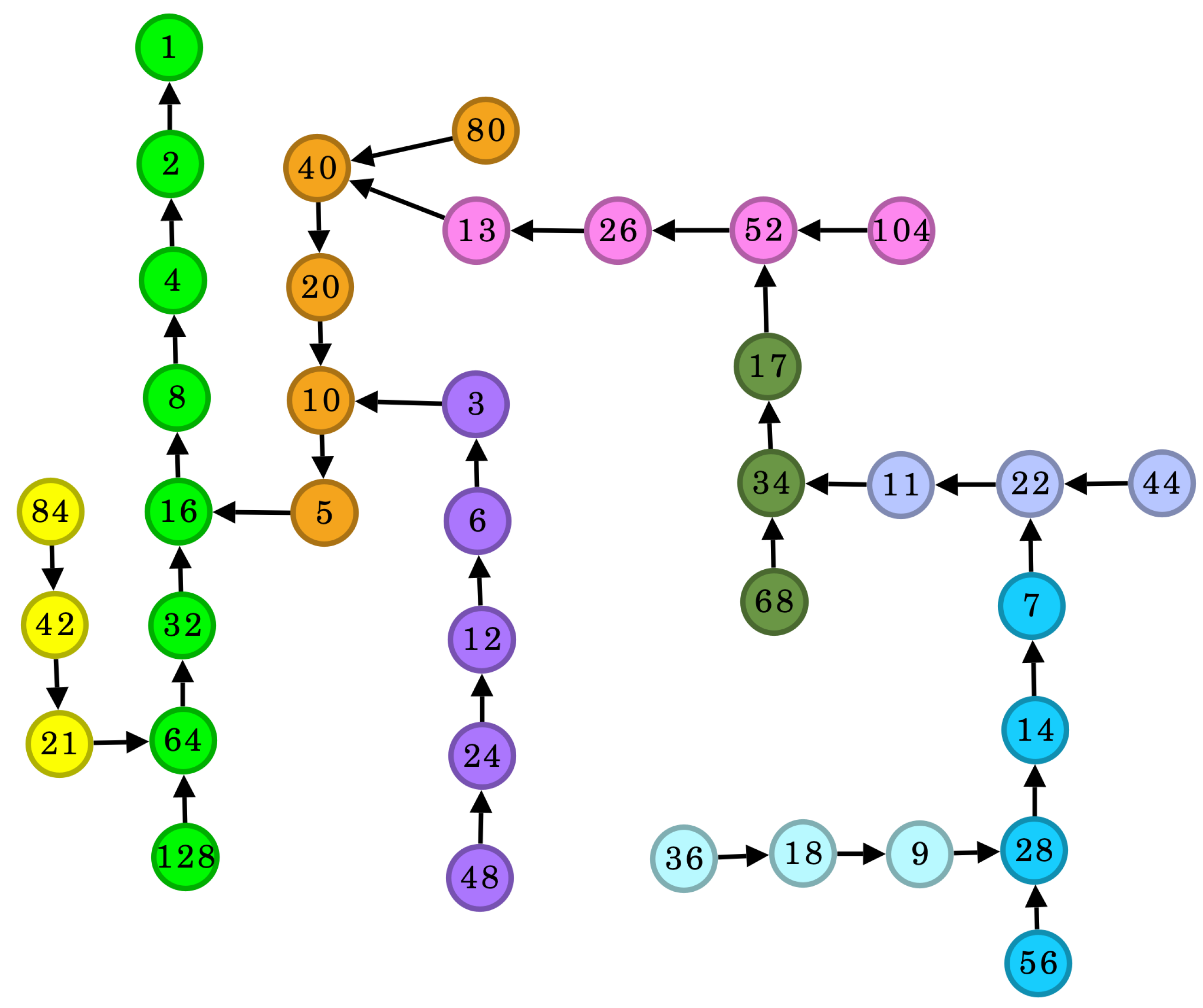

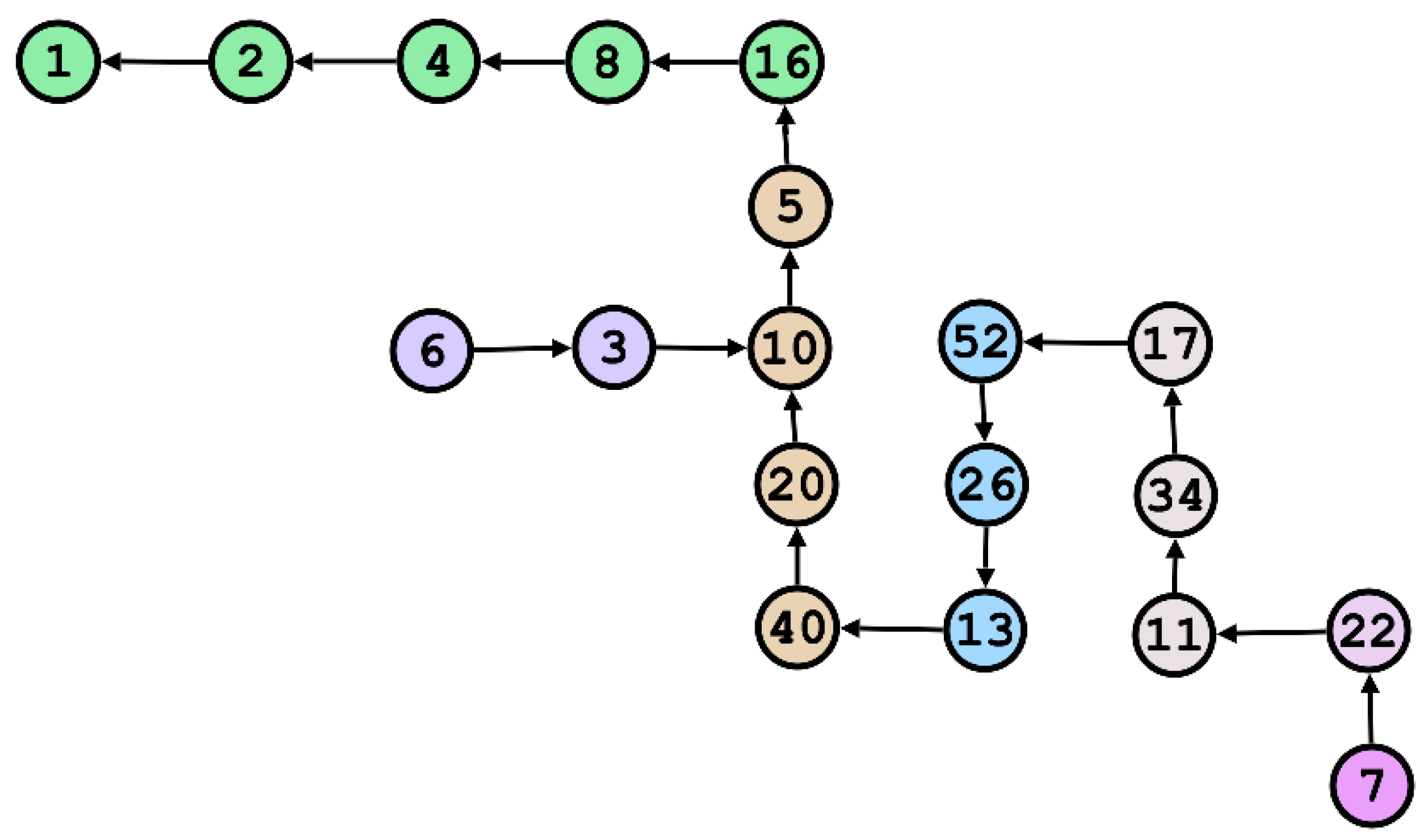

- Backbone of the Tree: The sequence starting with the integer 1 serves as the backbone of the Collatz tree. This backbone corresponds to the powers of 2, , which forms the central structure from which all branches emerge.

- Branches: All other sequences that do not start with 1 are referred to as branches. These branches either originate directly from the backbone or from other branches, as illustrated in Figure 1. Each branch begins with an odd natural number of the form , where , and subsequent numbers are generated by repeatedly doubling the predecessor. This represents the inverse of the operation in Equation 1, producing an infinite sequence of even numbers except for the initial odd number . Thus, the tree is inherently infinite.

- General Formula for Branches: The backbone, branches, and their corresponding sequences can be compactly expressed using the following formula:where n identifies the branch, and m determines the even numbers within that branch.

-

Branch-Creating Numbers: The even numbers that give rise to additional branches can be expressed in the form:For example, when , . Since , this corresponds to a branch originating at:The derivation of Equation 4 is given in later sections.

-

Special Branches: Certain branches, such as those starting with odd multiples of 3, do not produce additional branches. This occurs because these branches lack any numbers of the form . Assuming that such a number exists in these branches leads to contradictions. For instance, assume there exists a number in these branches that satisfies . Hence,Simplifying further:Now, if is an odd multiple of 3 (e.g., ), then is a natural number. Let , where . Substituting, we have:Since is not an integer, k cannot be a whole number. Thus, there is no for which belongs to a branch starting with an odd multiple of 3. Therefore, these branches terminate and do not lead to further subbranches.

2. Inclusion of All Natural Numbers in the Collatz Tree

2.1. Existence of All Natural Numbers in the Collatz Tree Branches

2.2. Proof of the Formula Using Mathematical Induction

2.3. Constructing a Subtree Containing All Natural Numbers Up to N

- The operation in the Collatz formula generates all even numbers represented by , which correspond to the branching points in the Collatz tree.

- These branching points generate all odd numbers greater than or equal to 3 as roots. Including the backbone starting with 1, the Collatz tree encompasses all odd numbers.

-

Branch starting at 3: The branching point is . Since 10 is not part of the selected branches, its origin must be determined. Using the formula for any branch as shown in Equation 3:For , the calculation is:Dividing both sides by :The largest power of two dividing 10 is 2, so . Substituting:This identifies the odd number , meaning that 10 originates from the branch starting at 5. Since 5 is already part of the selected branches, it is extended to include 10.

- Branch starting at 5: The branching point is . For 16, , so . This indicates that 16 belongs to the backbone starting at 1. The backbone is extended to include 16.

- Branch starting at 7: The branching point is . For 22, , so . Since 11 is not part of the selected branches, a new branch starting at 11 is created and extended to include 22: .

-

Continuing the process for further branching points:

- –

- The branching point for 11 is , which belongs to the branch .

- –

- The branching point for 17 is , which belongs to .

- –

- The branching point for 13 is , which belongs to .

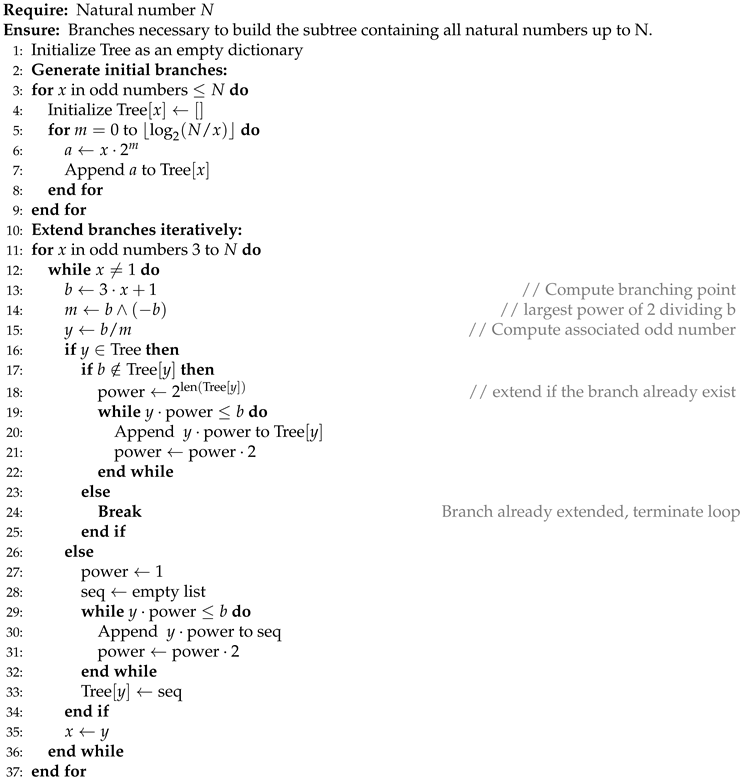

| Algorithm 1 GenerateBranches |

|

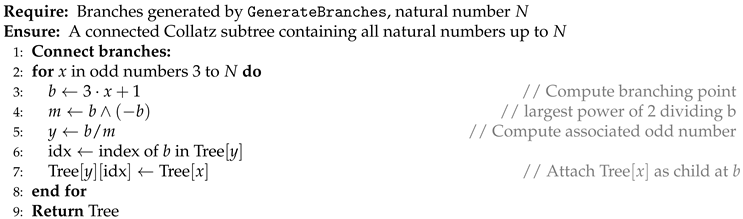

| Algorithm 2 BuildSubtree |

|

3. Nonexistence of Cycles Other Than the Cycle

- As , the term approaches:

- For , the value is:

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Jeffrey C Lagarias. The Ultimate Challenge: The 3x + 1 Problem. American Mathematical Society, 2023.

- Wei Ren, Simin Li, Ruiyang Xiao, and Wei Bi. Collatz conjecture for 2100000 − 1 is true-algorithms for verifying extremely large numbers. In 2018 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation (SmartWorld/SCALCOM/UIC/ATC/CBDCom/IOP/SCI), pages 411–416. IEEE, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Guillermo Wells Abascal. Bottom-up approach to the collatz conjecture. ESS Open Archive eprints, 205:20510515, 2024.

- Eyob Solomon Getachew and Beakal Gizachew Assefa. Efficient computation of collatz sequence stopping times: A novel algorithmic approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.04032, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ali Ebnenasir. Specifying and verifying the convergence stairs of the collatz program. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.04777, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Naouel Boulkaboul. 3n + 3k: new perspective on collatz conjecture. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.00073, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Takehiko Mori. Application of operator theory for the collatz conjecture. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.08084, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Weicheng Fu and Yisen Wang. The structure of the route to the period-three orbit in the collatz map. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.08097, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fabiano Nicola, Mirkov Nikola, and Radenović Stojan. Some considerations on the total stopping time for the collatz problem. Vojnotehnički glasnik, 72(3):1019–1028, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Michael R Schwob, Peter Shiue, and Rama Venkat. Novel theorems and algorithms relating to the collatz conjecture. International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences, 2021(1):5754439, 2021. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Chatgpt: Language model for text generation and assistance. Version 4, released in March 2024, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).