Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

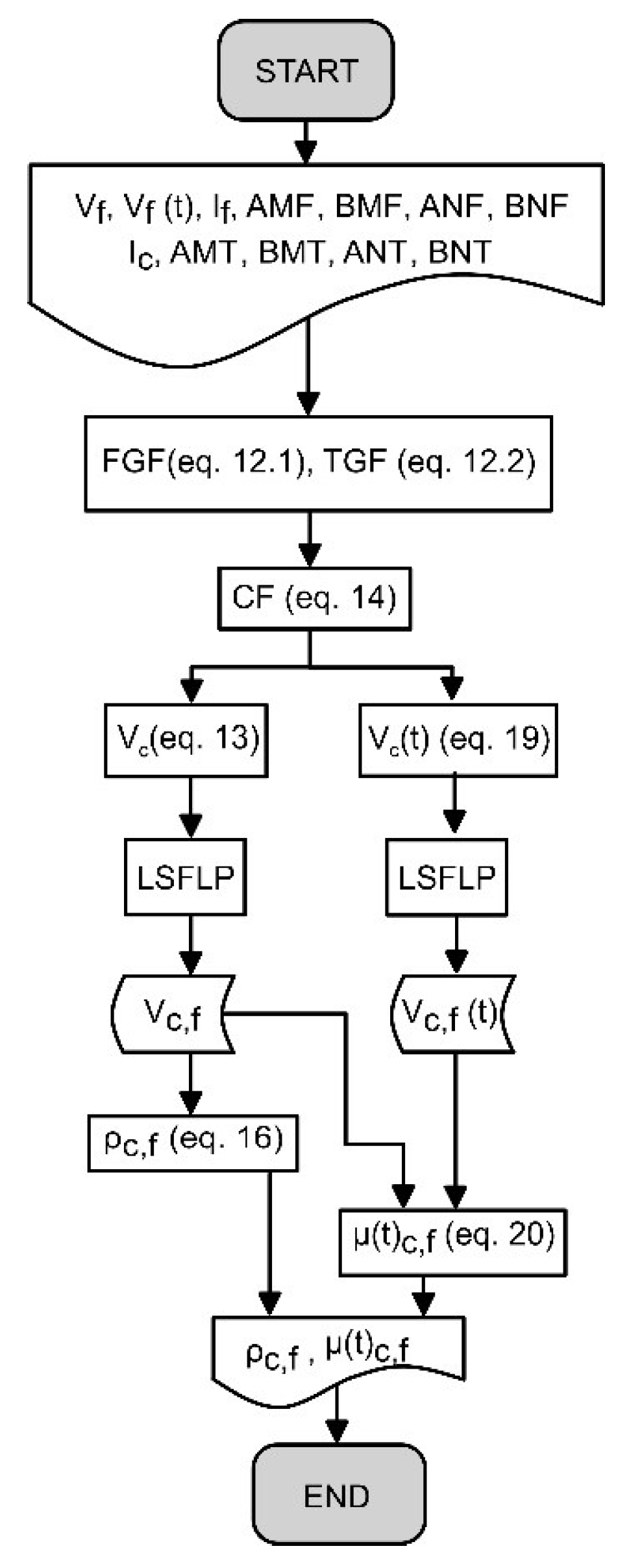

2.1. Smoothing Filter

Least Square Filter with Legendre Polynomial Basis Function

- Filtering process: A computing output response from a linear filter due to an input signal and generating an estimation error by comparing this output with a desire or reference signal.

- An adaptive process: Involve the automatic adjustment of the parameters of the filter in accordance with error estimation.

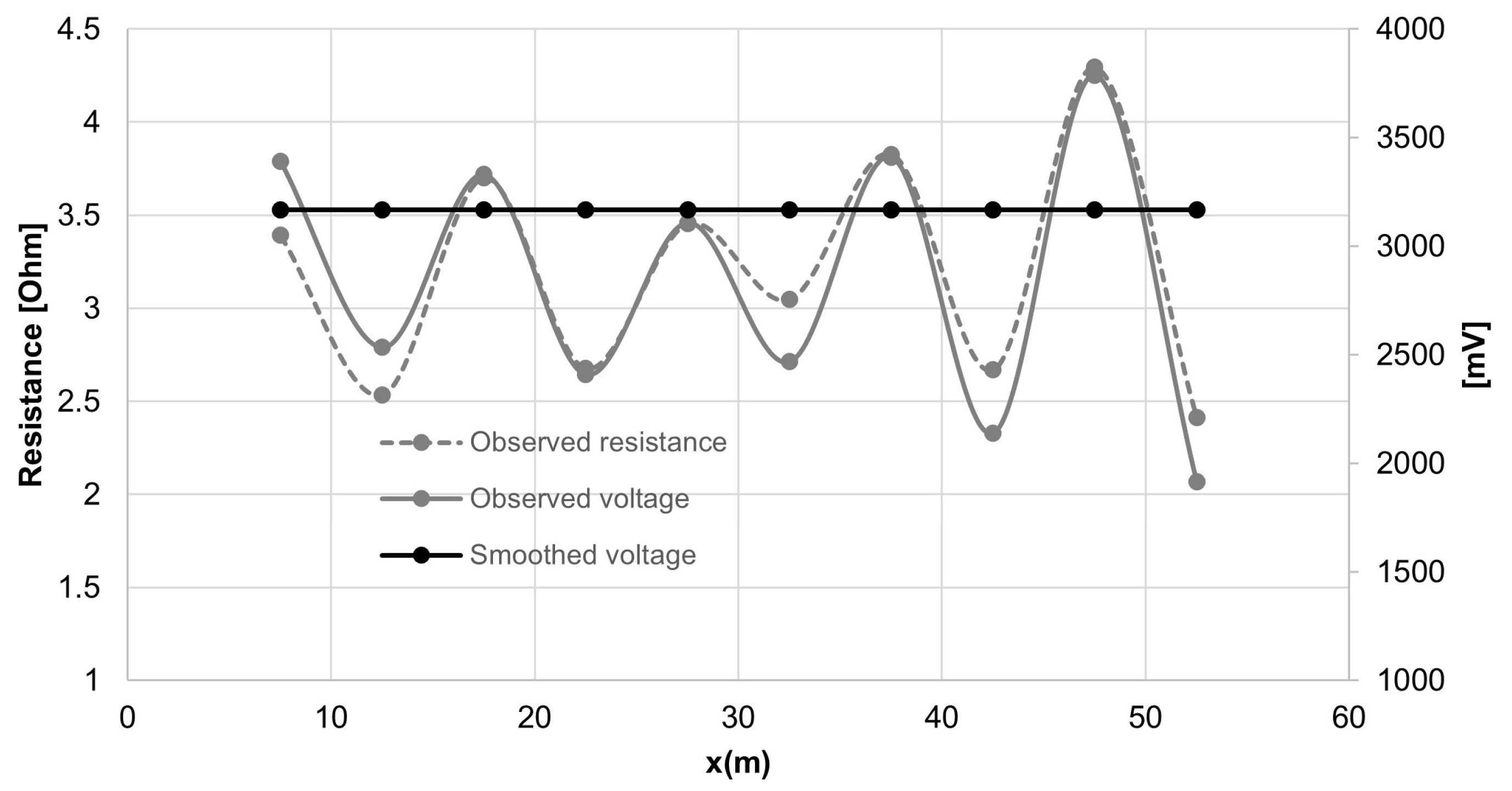

2.2. Smoothing Process and Correction Factor Proposal

Stationary Voltage Smoothing and Apparent Resistivity

Transient Voltage Smoothing and Chargeability

3. Results

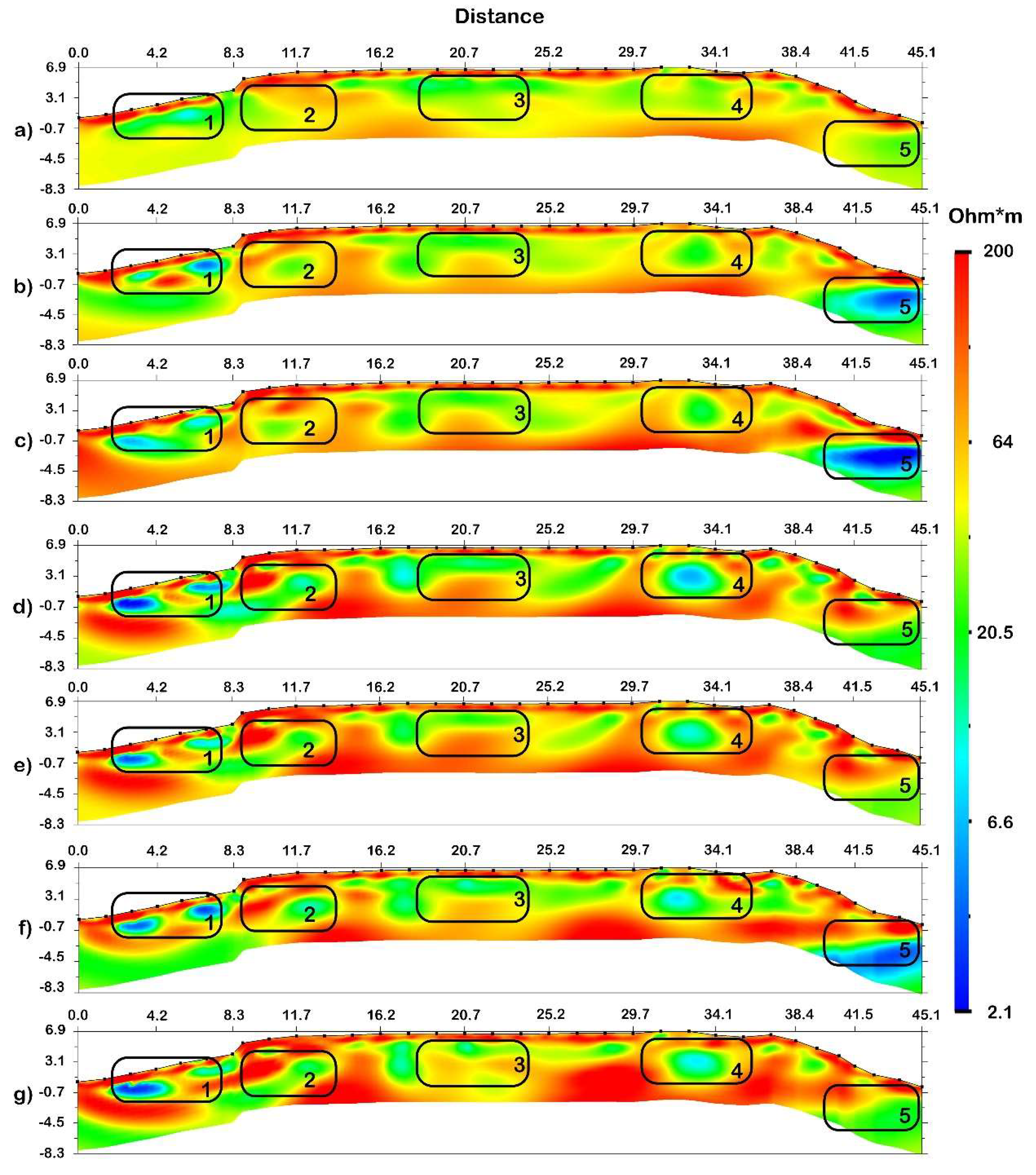

3.1. Archaeological Site of Mitla

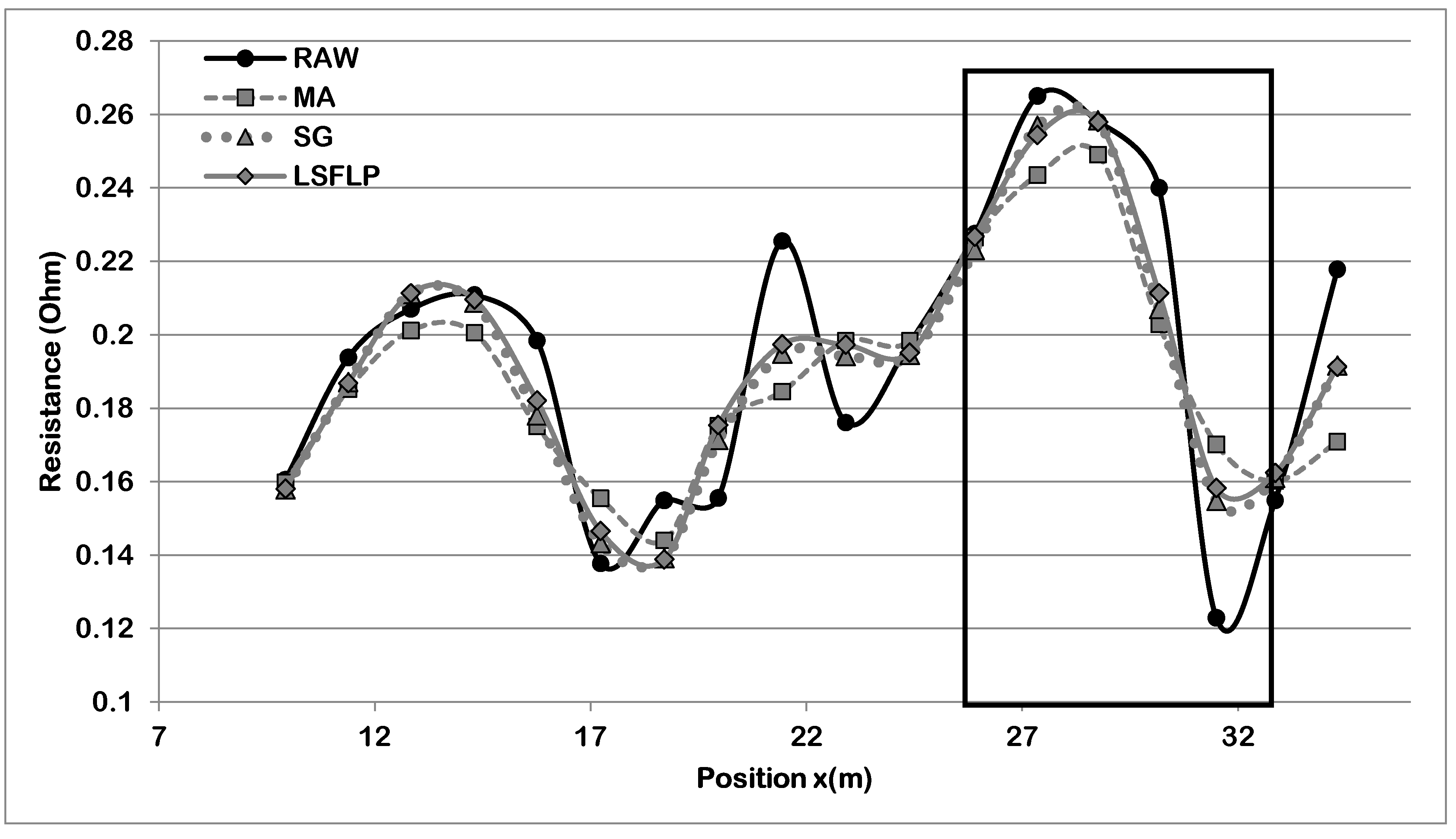

3.2. Hydrocarbon Contaminated Site (North of Mexico City)

4. Discussion

El Calvario (The Calvary), Mitla Archaeological Zone

Hydrocarbon Contaminated Site (North of Mexico City)

5. Conclusions

References

- Alfy, M.E.; Lashin, A.; Faraj, T.; Alataway, A.; Tarawneh, Q.; Al-Bassam, A. Quantitative hydro-geophysical analysis of a complex structural karst aquifer in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allred, B.; Reza, E.M.; Saraswat, D. Comparison of electromagnetic induction, capacitively-coupled resistivity, and galvanic contact resistivity methods for soil electrical conductivity measurement. Applied Engineering in Agriculture, 2006, 22, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, K.; Bahi, L.; Ouadif, L. Enhancing geophysical signals through the use of Savitzky-Golay filtering method. Geofísica Internacional, 2014, 53, 399–409. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0016-71692014000400003&lng=es&tlng=en (accessed on 21 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, S. Using Savitzky-Golay filtering method to optimize surface phosphate deposit disturbances. Ingenierías, 2007, 10, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Binley, A.; Cassiani, G.; Middleton, R.; Winship, P. Vadose zone flow model parameterization using cross-borehole radar and resistivity imaging. Journal od Hydrology, 2002, 267, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, E.; Eswara Rao, V. Wavelet Analysis of Geophysical Well-log Data of Bombay Offshore Basin, India. Mathematical Geosciences, 2012, 44, 901–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, T.; Leroux, V.; Nissen, J. Measuring techniques in induced polarization imaging. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2002, 50, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydycheva, S.; Rykhlinski, N.; Legeido, P. Electrical-prospecting method for hydrocarbon search using the induced-polarization effect. Geophysics, 2006, 71, G179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, R.N.; Cull, J.P. Denoising time-domain induced polarization data using wavelet techniques. Exploration Geophysics, 2016, 47, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Orozco-Esquivel, T.; Navarro, M.; López-Quiroz, P.; Luna, L. Digital Geologic Cartography and Geochronologic Database of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and Adjoining Area. Terra Digitalis, 2018, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Tagami, T.; Eguchi, M.; Orozco-Esquivel, M.T.; Petrone, C.M.; Jacobo Albarrán, J.; LópezMartínez, M. Geology, geochronology and tectonic setting of late Cenozoic volcanism along the south-western Gulf of Mexico: The Eastern Alkaline Province revisited. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2005, 146, 284–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandaca, G.; Auken, E.; Christiansen, A.V.; Gazoty, A. Time domain induced polarization: full-decay forward modelling and 1D laterally constrained inversion of Cole-Cole parameters. GEOPHYSICS, 2012, 77, E213–E225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.; Kemna, A.; Zimmermann, E. Data error quantification in spectral induced polarization imaging. GEOPHYSICS, 2012, 77, E227–E237. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, R.C.; Hohmann, G.W.; Killpack, T.J.; y Rijo, L. Topographyc effects in resistivity and induced polarization surveys. Geophysics, 1980, 45, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.O.; Sekii, T. On the effect of error correlation on linear inversions. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2002, 335, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S.; Adaptive Filter Theory, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2002.

- Iris Instruments. Processing software. Available online: https://www.iris-instruments.com/syscal-prosw.html (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Jervis, R.; Pringle, J.K.; Tuckwell, G.W. Time-lapse resistivity surveys over simulated clandestine graves. Forensic Science International, 2009, 192, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrecque, D.J.; Morelli, G.; Daily, W.; Ramirez, A.; Lundegard, P.; 1999, Occam’s inversion of 3-D electrical resistivity tomography. Three-Dimensional Electromagnetics. January 1999, 575-590.

- LaBrecque, D.; Daily, W.; Adkins, P. Systematic errors in resistivity measurement systems: Presented at the 20th EEGS Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems, European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Tianqi, G.; Ji, Z.; Shijun, J.; Qingzhou, S.; Ming, H. An adaptive moving least squares method for curve fitting. Measurement 2014, 49, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhanxiang, H.; Liu, Q.H. Higher-order statistics correlation stacking for DC electrical data in the wavelet domain. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2013, 99, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, A.E.; Tejero-Andrade, A.; Hernández-Martínez, J.L.; Prado, B.; Chávez, R.E. Induced Polarization and Resistivity of Second Potential Differences (SDP) with Focused Sources Applied to Environmental Problems. Journal of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, 2019, 24, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexican Geological Service, 2002, Carta Geológico-Minera Ciudad de México E14-2, Estado de México, Tlaxcala, Distrito Federal, Puebla, Hidalgo y Morelos., escala 1:250000: Pachuca, Hidalgo., Primera Edición.

- Newmark, R.; Aines, R.; Hudson, G.; Lif, R.; Chiarappa, M.; Carrigan, C.; Nitao, J.; Elsholz, A.; Eaker, C. An integrated approach to monitoring a field test of in situ contaminant destruction. Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems. 1999, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, D.; Li, Y. Inversion of induced polarization data. Geophysics 1994, 59, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, J.; Copeland, A. Reduction of noise in induced polarization data using full time-series data. Exploration Geophysics, 2003, 34, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.; Daily, W.; LaBrecque, D.; Owen, E.; Chestnut, D. Monitoring an underground steam injection process using electrical resistance tomography, Water Resource. Res., 1993, 29, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ritz, M.; Robain, H.; Pervago, E.; Albouy, Y. ; Camerlynck. C.; Descloitres, M.; Mariko, A. Improvement to resistivity pseudosection modelling by removal of near-surface inhomogeneity effects: application to a soil system in south Cameroon. Geophysical Prospecting, 1999, 47, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M.; Dahlin, T.; Olsson, P.-I.; Günther, T. Data acquisition, processing and filtering for reliable 3D resistivity and time-domain induced polarization tomography in an urban area: field example of Vinsta, Stockholm. Near Surface Geophysics, 2018, 16, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, B. Searching for graves using geophysical technology: field Tests with ground penetrating radar, magnetometry, and electrical resistivity. Journal of Forensic Science, 2003, 48, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Santarato, G.; Ranieri, G.; Occhi, M.; Morelli, G.; Fischanger, F.; Gualerzi, D. Three-dimensional Electrical Resistivity Tomography to control the injection of expanding resins for the treatment and stabilization of foundation soils: Engineering Geology, 119, Issues 1-2, 18-30. Three-dimensional electrical resistivity tomography to control the injection of expanding resins for the treatment and stabilization of foundation soils. Engineering Geology, 2011, 119, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and differentiations of data by simplified least squares procedures. Analytical chemistry, 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, R.E. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Applied Geophysics: Society of Exploration Geophysicist, Fourth Edition. 2002. ISBN: 978-1-56080-118-4.

- . [CrossRef]

- Slater, L.; Binley, A.; Brown, D. Electrical Imaging of Fractures Using Ground-Water Salinity Change. Ground Water, 1997, 35, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogade, J.A.; Scira-Scarppuzzo, F.; Vichabian, Y.; Shi, W.; Rodi, W.; Lesmes, D.P.; Morgan, F.D. Induced-polarization and mapping of contaminant plumes. GEOPHYSICS, 2006, 71, B75–B84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trogu, A.; Rainiere, G.; and Fischanger, F. 3D Electrical Resistivity Tomography to Improve the Knowledge of the subsoil below Existing Buildings. Environmental Semeiotics, 2011, 4, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokas, G.N.; Diamanti, N.; Tsourlos, P.I.; Vargemezis, G.; Stampolidis, A.; Raptis, K.T. Geophysical prospection at Hamza bey (Alkazar) monument, Thessaloniki, Greece. Mediterranean Archaeology Archaeometry, 2013, 13, 9e20. [Google Scholar]

| x(m) | FGF | Current (A) | Voltage (V) | (V/A) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.54 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 12.56 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 17.58 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 22.61 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 27.63 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 32.66 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 37.68 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 42.70 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 47.73 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| 52.75 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3167.56 | 3.17 | 100 |

| Geometric factor | Field data | Corrected data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field | Teoretical | (A) | (V) | (V/A) | V | (V/A) | ||

| 29.49 | 31.57 | 1000 | 3390.979 | 3.390979 | 107.0532 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 39.46 | 31.57 | 1000 | 2534.211 | 2.534211 | 80.00506 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 27.03 | 31.57 | 900 | 3329.633 | 3.699593 | 116.7961 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 37.36 | 31.57 | 900 | 2408.993 | 2.676659 | 84.50214 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 28.95 | 31.57 | 900 | 3108.808 | 3.454231 | 109.0500 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 32.82 | 31.57 | 810 | 2468.007 | 3.046922 | 96.19134 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 26.13 | 31.57 | 891 | 3409.873 | 3.827018 | 120.8189 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 37.47 | 31.57 | 801.9 | 2140.112 | 2.668801 | 84.25406 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 23.29 | 31.57 | 882.09 | 3787.419 | 4.293688 | 135.5517 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| 41.43 | 31.57 | 793.881 | 1916.198 | 2.413709 | 76.20082 | 3167.56414 | 3.167564 | 100 |

| Initial data |

Final data |

Discarded data | RMS % | L2-Norm | Damping factor |

Smoothing factor |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw data | 247 | 227 | 20 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| MA Filtered | 247 | 227 | 20 | 0.97 | 0.10 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| MA Filtered and Corrected | 247 | 236 | 11 | 0.98 | 0.11 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| SG Filtered | 247 | 235 | 12 | 2.05 | 0.47 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| SG Filtered and Corrected | 247 | 235 | 12 | 2.05 | 0.47 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| LSQFLP Filtered | 247 | 238 | 9 | 2.05 | 0.47 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| LSQFLP Filtered and Corrected | 247 | 236 | 11 | 2.43 | 0.66 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

|

Depth (m) |

21 (mg/L) |

25 (mg/L) |

MF21 (mg/kg) |

A11 (mg/kg) |

| 1.2 | 0.78 | 0.80 | ||

| 2.4 | 3.46 | 0.82 | ||

| 3.6 | 57.77 | 19.17 | ||

| 4.8 | 362.79 | 21.90 | ||

| 6.0 | 860.55 | 157.06 | ||

| 7.2 | 40.891 | 399.753 | 265.85 | 507.23 |

| 8.4 | 3329.74 | 896.92 |

| Initial data |

Final data |

Discarded data | RMS % | L2-Norm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw data | Resistivity Chargeability |

189 | 171 | 18 | 16.27 37.87 |

0.25 |

| MA filtered | Resistivity Chargeability |

189 | 176 | 13 | 6.99 18.92 |

0.52 |

| MA filtered and corrected | Resistivity Chargeability |

189 | 168 | 21 | 4.78 6.83 |

2.53 |

| SG filtered | Resistivity Chargeability |

189 | 166 | 23 | 7.59 15.21 |

0.60 |

| SG filtered and corrected | Resistivity Chargeability |

189 | 171 | 17 | 4.74 10.74 |

0.53 |

| LSFLP filtered | Resistivity Chargeability |

189 | 164 | 25 | 10.85 14.75 |

0.57 |

| LSFLP filtered and corrected | Resistivity Chargeability |

189 | 174 | 15 | 10.84 11.32 |

0.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).