1. Background

There is extensive scientific literature supporting that insulin resistance (IR) with consequent hyperinsulinemia (Hyperins) is strictly associated with the development of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cellular senescence and cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. All these pathologies are, in turn, associated with an increased number of hospitalizations and deaths. Over the centuries there has been a progressive change in the lifestyle of human beings. In fact, in the past there was a more correct relationship between the intake of calories from food and the calories burned to obtain it. Today, particularly in Western countries, food is bought on supermarket counters, often ready-made and ultra-processed, so very few calories are burned to get it. Furthermore, given the work commitment of men and women, there is an ever-decreasing consumption of vegetables which require a lot of time because they have to be bought, selected, washed and cooked before being eaten and, on the contrary, the consumption of carbohydrates has significantly increased already from the young age. Furthermore, with the invention of elevators, escalators, scooters and cars, we move less and less on foot. Furthermore, the stress and competition of modern life produce an increase in diabetogenic hormones such as cortisol and growth hormone. This has led to a progressive increase in the prevalence of IR and type 2 diabetes in the general population, particularly in developed and developing countries, notably its onset is earlier even in childhood, so much so that IR now exceeds the value of 50% [

7,

8] and

global prevalence of type 2 diabetes is expected to increase to 7079 individuals per 100,000 by 2030, reflecting a continued rise [

9]

. Therefore, the spread of IR with associated Hyperins is progressively and rapidly growing worldwide with all the consequences we know well in terms of public health and healthcare spending.

This descriptive literature review aims to verify whether there is a direct relationship between IR with associated hyperinsulinemia (Hyperins) and increased mortality. For this reason, publications on this topic were searched on the major scientific databases such as Pubmed, Scopus, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, etc, using the following keywords: Insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, all cause deaths, cardiovascular deaths, cancer deaths, hospitalization, cellular senescence, cancer. Studies published in English in high-impact medical journals, from 1980 to 2024, with the most impeccable design, were selected.

2. Insulin Resistance and Hyperinsulinemia

IR is a widespread condition, in which a certain quantity of insulin secreted by the pancreas produces a lower-than-expected metabolic effect on glycemic control. Therefore, to maintain blood sugar within the normal range, the pancreas is stimulated to secrete a greater amount of insulin. Consequently, a chronic Hyperins is a constant and important feature of IR [

10,

11,

12]. It is not the purpose of this article to go into detail about the mechanisms of action that cause the condition of IR/Hyperins nor the mechanisms by which it determines the relevant alterations at the level of our body, because this has been widely explained elsewhere [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Although the mechanisms that determine this condition are not yet fully clarified, it is clear that defects are observed both at the insulin receptor level and the post-receptor downstream cascade. It is now recognized that the binding of insulin with its receptor in the target tissues activates two important post receptor signaling pathways, namely phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3k) and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK). In IR conditions, the first is altered in its functioning, while the second is little or not altered at all [

10,

11,

12].

The PI3K pathway predominantly regulates glucose metabolism and the synthesis and secretion of nitric oxide (NO) by endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, while the MAPK pathway mainly regulates cell growth and the synthesis of endothelin-1 (ET -1) by endothelial cells. As it is well known, NO has a vasodilating action and protects the vascular wall from atherosclerotic damage, vice versa ET-1 has a potent vasoconstrictor action and stimulates the development of the atherosclerotic process. This imbalance between NO and ET-1 in IR conditions determines an alteration of vascular homeostasis which creates the prodromes for the development and progression of atherosclerosis [

13]. Furthermore, excess insulin stimulates sympathetic activity, increases tubular sodium reabsorption in the kidney and acts as growth factor on the endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes, causing arterial hypertension and concentric remodeling of the left ventricle, which in turn, over time, can cause heart failure [

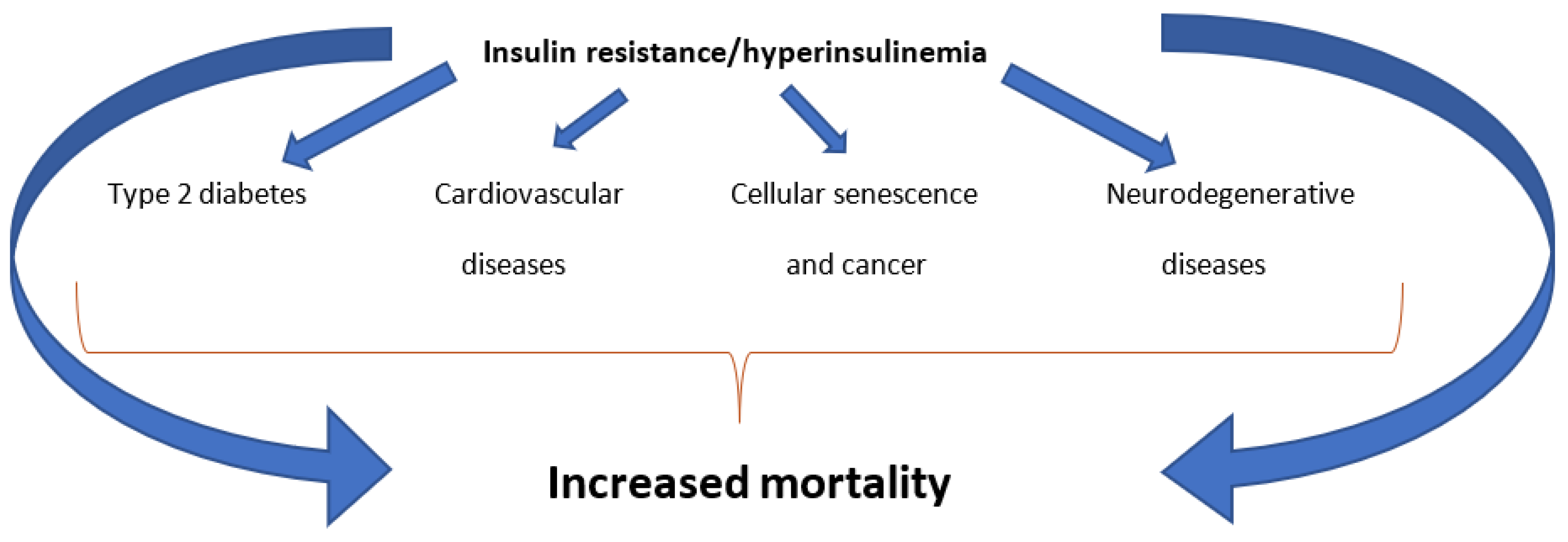

13]. In addition, the chronically increased levels of circulating insulin act by numerous other mechanisms that determine, over time, important alterations in various district of the body. Among these, the best known are: the onset of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular damage, the development of cellular senescence and tumors, and brain damage [

1]. As a consequence of the above, it is obvious to think that IR/Hyperins could lead to an increase in hospitalizations and, therefore, in healthcare spending and, above all, in mortality (

Figure 1).

3. Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia and Mortality Risk

There is a fair amount of scientific literature to support the fact that IR/Hyperins can cause an increase in mortality. Some studies have been conducted in diabetic subjects, considering IR as the main cause of the development of type 2 diabetes. An interesting study from 2016, carried out on a population of 55,292 individuals, of which 15.6% diabetics, clearly demonstrated how diabetes was associated with premature death from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and non-cardiovascular and non-cancer causes, during a 10-year follow-up [

14]. A more recent study, published in 2023, showed how diabetic subjects can die, on average, 6 years earlier than non-diabetics, and that the risk of death was higher the earlier in life diabetes was established [

15]. Another very interesting study, published in Diabetes Care in 2010, aimed to verify whether IR itself, evaluated by calculating HOMA-IR, was associated with an increase in all-cause mortality or disease-specific mortality in non-diabetic subjects in the USA. For this reason, 5511 non-diabetic adults, participants in the third US Nutrition Examination Survey (1988-1994) were evaluated during a 12-year follow-up, and the results were corrected for a series of confounding factors, such as age, sex, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, alcohol consumption, race/ethnicity, cultural level, smoking, physical activity, C-reactive protein levels, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides. The results of the study highlighted with absolute clarity that HOMA-IR was associated with all-cause mortality in the US population [

16]. Although the gold standard method for the diagnosis of IR is the hyper insulinemic euglycemic clamp, we have many simple surrogate index of IR, and HOMA-IR is one of them, obtained by taking into account the simultaneous fasting levels of glucose and insulin in the blood [HOMA-IR = (glucose mmol/L × insulin mU/L)/22.5] [

13]. Another study on a large number of subjects (22,837) was conducted on a subsample of women aged between 50 and 79 who participated in the Women's Health Initiative between 1993 and 1998, and had their baseline fasting insulin and glucose values recorded. In this group, baseline HOMA-IR was calculated and women were followed during a median of 18.9 years for the onset of cancer-related and all-cause deaths, assessed by medical record and NDI. During this time, a total of 7415 deaths and 1820 cancer related deaths occurred. It was observed that women in the highest quartile of HOMA-IR were associated with significantly higher cancer and all-cause mortality (P trend=0.003 and P trend<0.001 respectively). Therefore, the authors concluded that an early intervention in postmenopausal women with high HOMA-IR could be beneficial to reduce the risk for cancer-specific and all-cause mortality [

17].

A meta-analysis study, carried out with the aim of evaluating the association of elevated fasting insulin levels or IR, as assessed by calculating the HOMA-IR, with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in non-diabetic adults has confirmed that HOMA-IR is independently associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality [

18]. Two other recent articles have demonstrated that IR, assessed using surrogate indices, is associated with increases in mortality. A Korean cohort study, with an average follow-up of approximately 10 years, found that IR, assessed using surrogate indices, increases the risk of all-cause mortality by 87%, cardiovascular mortality by 133% and adverse cardiovascular events by 267% in patients with cardiovascular disease [

19]. Therefore, the authors suggest that prompt lifestyle modification intervention in individuals with increased HOMA-IR could be a good strategy to prevent increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and adverse cardiovascular events [

19]. A very recent study, published in 2024 in Cardiovascular Diabetology, further explored the relationship between different surrogate indices of IR and all-cause mortality, and sought to identify valid predictors of survival in patients with coronary heart disease and hypertension. Data were derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 2001-2018) and the National Death Index (NDI) on 1126 participants. During a median follow-up of 76 months, 455 patients died. Analysis of the results demonstrated that there is a U-shaped relationship between HOMA-IR and all-cause mortality in these patients, with an inflection point at a value of 3.59. For this reason, the authors conclude that HOMA-IR can be considered a reliable predictor of all-cause mortality in these patients [

20].

An observational cohort study, carried out by analyzing the NHANES data of 5301 adult patients (≥20 years) with IR from 2005 to 2018 and calculating the Life's Essential 8 framework to establish cardiovascular health (CVH) status, has highlighted evidence that in patients with IR and bad CVH there was an increase in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality compared to groups with IR and good CVH [

21,

22].

An article published in the International Journal of Obesity in 2022 aimed to determine the independent associations between BMI, fasting circulating insulin level, C-Reactive Protein and mortality from any cause in a general population sample. The study in question was a prospective cohort study in adult subjects, carried out with data obtained from the NHANES and the NDI on 12,563 participants. Statistical analysis of the data produced the following results: high fasting insulin and C-reactive protein levels, but not BMI values, were associated with an increased risk of mortality. Therefore, authors concluded that the increased mortality, previously attributed to a higher BMI, is much more likely due to Hyperins and inflammation rather than obesity [

23].

In another recent study, 14,653 participants were screened from the NAHNES (2001-2018) to verify the predictive values of IR replacement indexes for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Over a median follow-up period of 116 months, A total of 2085 (10.23%) all-cause deaths and 549 (2.61%) cardiovascular disease (CVD) related deaths were recorded during a median follow-up period of 116 months. Interestingly, the

metabolic score for insulin resistance (METS-IR) resulted significantly associated with both all-cause and CVD mortality, and both showed an approximate “U-shape” relation. In particular, baseline METS-IR lower than the inflection point (41.33) was negatively associated with mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.972, 95% CI 0.950–0.997 for all-cause mortality]. In contrast, as expected, baseline METS-IR values higher than the inflection point (41.33) were positively associated with mortality (HR 1.019, 95% CI 1.011–1.026 for all-cause mortality and even higher for cardiovascular disease mortality, HR 1.028, 95% CI 1.014–1.043). Furthermore, significant associations between METS-IR values and any-cause and cardiovascular mortality were predominantly present in the population aged < 65 years [

24]

. Another large study confirmed these results. In fact, a cohort of 19 204 participants was recruited, yet from the NAHNES 1999-2018, to determine the relationships of METS-IR with all-cause and CVD-specific mortality. During a median follow-up of 9.17 years, 2818 deaths were observed, and 875 of which were CVD-deaths. The results showed that higher METS-IR values were associated with increased all-cause (hazard ratio [HR] 1.38, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.14-1.67) and CVD mortality (HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.10-2.12) compared with the lower METS-IR values. The restricted cubic splines showed a nonlinear relationship between METS-IR and all-cause mortality. Only METS-IR values above the threshold (41.02 μg/L) were positively correlated with all-cause death, while METS-IR had a linear positive relationship with CVD mortality [

25]

. It has also been verified that a rather close relationship between high values of the immune–inflammation index (SII) and high values of insulin resistance and in turn between higher SII values with both increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality mah be found [

26]. SII is a

new inflammatory biomarker based on platelet count × Neutrophil count/lymphocyte count calculation,

which was proved to reflect the degree of systemic inflammation [

27]

. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is another simple and inexpensive surrogate new marker of insulin resistance [

28]

. In a study of 10,734 participants with metabolic syndrome, (5,570 females and 5,164 males), with a median age of 59 years from the NAHNES 1999–2018, was shown that high levels of TyG-related indices were significantly associated with the all-cause mortality [

29]

.

An interesting study, recently published in Diabetes Care, shows, through a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 19,960 patients with type 1 diabetes, that IR may be an additional risk factor for both cardiovascular disease deaths and all-cause mortality also in patients with type 1 diabetes [

30]. It was also demonstrated, after a median follow-up of 6.6 years, in 121 consecutive patients with chronic heart failure (cHF), that IR, assessed by the fasting insulin resistance index (FIRI≥2.7), was correlated with a higher number of deaths from all causes in patients with cHF, and also that patients with cHF and IR were at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes [

31]. A meta-analysis study, carried out on data obtained from 6156 men and 5351 women aged between 30 and 89 years, highlighted how, during a follow-up of 8.8 years, even directly the highest fasting insulin levels, defined by the highest quartile, were significantly associated with increased cardiovascular mortality, in both men and women and independently of other risk factors [

32]. Other major evidences emerge thanks to the Women's Health Initiative investigators staff and trial participants. Through the analysis of data obtained from 22,837 postmenopausal women, followed for a median follow-up of 19.8 years, it was demonstrated how the highest levels of IR, measured by HOMA-IR, were associated with a higher incidence of breast cancer and all-cause mortality after breast cancer diagnosis [

33]. It is known that obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes are associated with an increase in cancer mortality. A population-based observational study aimed to verify whether hyperinsulinemia per se is a risk factor for cancer death in a non-obese population without diabetes. This prospective cohort study used data collected from the NAHNES between 1999 and 2010, followed through December 31, 2011. The study included 9,778 subjects aged 20 years or older without diabetes or a history of cancer: 6718 non-obese subjects, of which 2057 had hyperinsulinemia and 3060 obese subjects of which 2303 had hyperinsulinemia.

The results of this study are doubly very interesting: Firstly, because they showed that overall cancer mortality was significantly higher (p=0.005) in subjects with hyperinsulinemia than in those without, and, even considering only non-obese subjects, cancer mortality was significantly (p=0.02) higher in those with hyperinsulinemia. For these reasons, the authors concluded that a reduction in circulating insulin levels should be considered an important approach to prevent cancer and cancer mortality [

34];

secondly, because from these data we can deduce the prevalence of hyperinsulinemia in the general population of the USA over 20 years of age. It was 44.6% in the whole group, 75% in the obese population and 30 % in normal weight people [

34]. It has been also shown that insulin

response to diet can predict the risk of mortality. In a study that included 22,246 participants from the NAHNES 1999-2010 (mean age = 47.8 years; 48.9% men) was shown a significant increased risk of mortality across the quartiles of dietary hyperinsulinemia index (DHI), i.e., subjects with a highest DHI (Q4) had an increased risk of all-cause (HR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.17-1.26), CVD (HR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.07-1.29), and cancer (HR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.08-1.23) mortality in comparison to the first quartile (Q1; p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Similarly, subjects with the highest dietary insulin resistance indices (DIRI–Q4) had 23% and 31% higher risk of all-cause and CVD mortality, respectively, as compared with Q1, while the HR for cancer mortality was non-significant (HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.35-2.61) [

35]

. In addition, in a large meta-analysis study on 23,990 participants, a subgroup analysis based on gender showed a significant association between fasting insulin level and cancer mortality in men (pooled HR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.23-3.01) [

36]

. Also very interesting are the results of a study carried out to verify the relationship between insulin therapy and clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes stratified by level of IR. Through a cross sectional analysis of the NAHNES database from 2001 to 2010, a sample of 3124 subjects with diabetes was selected, representing a US population of 16,713,593. The doses of insulin used were reported by patients. Fasting blood glucose and insulin levels were used to verify the presence of IR through the calculation of the HOMA-IR. Subjects were then placed into a high or low HOMA-IR group based on the sample median. The outcomes considered in this study were mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and diabetic nephropathy. The study results, after adjusting for covariates that included glycemic control and the presence of comorbidities, demonstrated that insulin use was significantly associated with an elevated risk of mortality (OR: 2.39, 95% CI: 1.136–5.010), as well as an increased number of MACEs and a greater possibility of developing diabetic nephropathy in the high IR group, demonstrated by high HOMA-IR values. Therefore, the therapeutic use of insulin in diabetics with insulin resistance is associated with an increased risk of mortality, meaning that the administration of insulin in insulin resistant subjects without having corrected the IR can become very dangerous over time [

37].

It has also been demonstrated that Hyperins is associated with increased long-term mortality in non-diabetic patients after an acute myocardial infarction [

38]. IR/Hyperins has also been found independently associated with an increased risk of infection-related death, indicating a possible role of impaired glucose metabolism in increased mortality following infections [

39].

4. Concluding Remark

IR with associated Hyperins should be considered an independent and important risk factor for different multiple pathologies, which, if neglected, determines a huge increase in deaths and healthcare spending. Increased circulating levels of fasting insulin, a condition characterizing IR, are related to increased mortality. From the analysis of the literature on the topic, it is clear that IR is associated with increased mortality not only from cardiovascular causes and cancer but also, more importantly, from all-cause mortality. In previous articles we have highlighted how IR/Hyperins is an independent cause of type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, cellular senescence and cancers, and neurodegenerative diseases [

1]. All these pathologies are recognized causes of frequent hospitalizations and increased mortality, with enormous social and healthcare costs. However, this review clearly shows that IR/Hyperins is per se associated with increased mortality.

Irrespective of all the emerging therapy and the goals to treat it, cardiovascular diseases remain the first cause of death in the western world. The heated debate about the residual cardiovascular risk does not take into consideration that it could also be due to other ignored risk factor such as IR with associated Hyperins. Recognize and intervene to treat all possible neglected causes of cardiovascular risk may also prevent an excessive increase in the doses of cholesterol-lowering drugs to control the residual risk, avoiding the high-dose side effects without reaching the mortality goals. Using substances to reduce the IR and circulating insulin levels, the residual cardiovascular risk could be reduced resulting in better outcomes.

Therefore, we expect that the scientific community and national health authorities promptly implement mass screening of the general population to identify and became aware the affected young individuals to lifestyle changes. An insulin sensitizing treatment will be started in affected patients, who do not normalize IR/Hyperins by lifestyles changes, to avoid the development of medical complications with all that entail for public health and economic burden.