1. Introduction

The "One Health" approach is an integrative strategy proposed by the Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations Environment Programme, World Health Organization, and World Organisation for Animal Health, aimed at balancing and optimizing the well-being of people, animals, and ecosystems. It promotes environmental health by preventing water contamination, air pollution, climate change, and other factors that cause disease. The commitment outlined in the joint "One Health" action plan, driven by these four entities, focuses on collectively promoting and supporting the implementation of this initiative. This is achieved by strengthening the capacities of governments, organizations, and communities to address complex, multidimensional health risks with more sustainable healthcare systems at global, regional, national, and local levels [

1].

The One Health methodology differs from traditional interdisciplinary approaches by offering an integrative perspective that recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, rather than addressing each aspect in isolation. This approach advocates for a holistic vision to tackle complex health and environmental issues, fostering collaboration among various disciplines to develop solutions tailored to current social contexts. The essence of this methodology lies in ensuring that disciplines and communities do not operate independently, placing a strong emphasis on prevention and early disease surveillance within their socio-economic and environmental context. Early detection and prompt action can avert public health problems. Consequently, One Health can be regarded as an innovative and essential method for addressing public health challenges, as it treats human, animal, and environmental health as an interconnected system. This interconnectedness enables the proposal and implementation of more effective and sustainable solutions to health problems arising from polluted environments or unmet needs at both local and global levels [

1].

Environmental health is a fundamental pillar for the well-being of humans, animals, and plants. Preserving ecosystem balance helps protect biodiversity and reduces the incidence and spread of diseases. Polluted water, inadequate sanitation, and lack of hygiene contribute significantly to mortality and morbidity in both humans and animals, especially among the most vulnerable populations in developing countries. Therefore, the "One Health" approach is based on a comprehensive understanding of the interconnections between the health of living beings and the natural environment, as well as how these connections manifest as health threats. Through this approach, it is possible to lay the foundations necessary to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including those related to eradicating poverty, hunger, health and well-being, reducing inequality, access to clean water and sanitation, economic growth, decent work, sustainable consumption and production, as well as global partnerships [

1].

"One Health" is a strategic approach that fosters the health of all living beings, as well as water security and water sanitation, given that the most prevalent and crucial element on Earth is water, a determining factor for the survival of all forms of life on the planet [

1]. Throughout human history, social nuclei and settlements have always been established in areas with sufficient access to freshwater [

2]. With the increase in population, the natural availability of water became limited, leading major civilizations to develop advanced techniques and systems to access new water sources, such as well drilling and aqueduct construction. These measures were essential for crop irrigation, animal feeding, hygiene, health, and the sustenance of the community itself, establishing water as a fundamental right [

3].

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the practice of capturing and utilizing water resources, specifically rainwater, has been used for over five thousand years to meet the needs of civilization [

4]. Throughout the centuries, humanity has relied on surface water as its primary source for supply, consumption, and transportation. With the demographic increase of societies, some communities settled in arid, semi-arid, and humid regions of the planet, which prompted the development of systems to collect rainwater. This technique became an alternative for irrigating crops and for domestic use [

5].

Therefore, the utilization of rainwater is a viable and effective option, as its collection only requires a capture and distribution system. This method presents several advantages, such as energy savings by not relying on the complete processes of extraction, distribution, and pumping needed to transport it to the supply area. Moreover, it is a relatively economical alternative [

6]. However, a significant disadvantage is that the availability of water is limited to rainy seasons and varies by region. It also depends on the size of the catchment area, the capacity of the storage tank, and while its physicochemical quality is acceptable, it is important to note that microbiologically it is not suitable for human consumption, which makes treatment necessary to ensure it is safe [

7].

Various studies in different public health programs in developing countries have identified deficiencies related to water resource management, which are linked to inadequate management, staff instability, lack of political commitment, reduction of financial resources, disconnection among stakeholders, and inefficient administrative management. All of this contributes to the consumed water failing to meet the physicochemical and microbiological standards necessary to prevent diseases among consumers [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Therefore, collaboration across sectors and disciplines through the "One Health" approach is a viable solution to address the complex challenges of environmental health that society faces [

1].

Traditionally, two approaches have been applied in settlements to ensure the right to water for consumption: the first involves seeking new supply alternatives, while the second focuses on efficiently using available resources in the territories. However, efforts have mainly concentrated on the first option, leaving the second lagging, which has negatively impacted the overall well-being of individuals, particularly regarding public health [

7,

12]. It is important to highlight that the World Health Organization defines health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of infections or diseases. Thus, the right to water plays a fundamental role in ensuring the right to health [

13].

Consequently, ensuring safe access to water resources is essential for improving the health conditions of the population and preventing the spread of diseases. All initiatives aimed at optimizing water quality significantly impact public health [

14]. Public health seeks to enhance quality of life and collective well-being by securing the right to a healthy environment and housing through the positive transformation of social, health, and environmental factors [

11,

15] The necessity to preserve water resources and treat water intended for human consumption became evident when establishing the relationship between the presence of microorganisms in water and the deterioration of public health. Thus, the lack of security in the provision of potable water exposes the community to the risk of experiencing outbreaks of waterborne diseases. Preventing such outbreaks is especially crucial, as water, being a transmission vehicle, has the potential to affect a wide proportion of the population simultaneously [

3].

Through a study conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean, an inverse relationship was identified between the infant mortality rate and the availability of drinking water, suggesting that implementing water supply infrastructure in countries with sanitation deficiencies could reduce mortality in children under five years old, thus improving child health and quality of life [

11]. Various studies have demonstrated the association between sanitary conditions, including access to drinking water, and diarrheal diseases, particularly in children under five. Consequently, ensuring access to safe drinking water is essential for improving health conditions in populations and preventing the spread of diseases [

11,

14,

15].

Therefore, through the geographical and social configuration of territories, various treatments have been proposed to enhance water quality for human consumption. Proper water treatment is one of the determinants for improving public health, as it prevents infectious diseases, especially digestive and respiratory ones, caused by pathogens present in water [

16,

17,

18]. Additionally, the conditions of water contamination, due to the presence of certain chemical components and industrial or domestic waste, affect ecosystems and, consequently, the health of settlements adjacent to discharges with such characteristics [

19,

20].

At the domestic level, various treatment methods have been recorded to eliminate turbidity, color, and pathogenic microorganisms causing diseases. These methods can be classified into i) systems that employ heat or ultraviolet light (such as boiling water, solar radiation, solar disinfection, UV lamps), ii) chemical treatments (coagulation, flocculation, and precipitation; adsorption; ion exchange; chemical disinfection), and iii) physical removal procedures (sedimentation or clarification; filtration using membranes, ceramic filters; filters with granular media or sand; aeration). [

21,

22]. Regarding the use of filtration systems at the household level, international studies have examined the viability of various technologies for rural communities. These technologies include slow sand filters [

23,

24], ceramic candle filters [

25,

26], membrane filter [

27] and ceramic pots [

28,

29]. In Colombia, some studies have documented the implementation of candle and ceramic pot filters, although these have only been in place for short periods [

30,

31].

Finally, treatments based on slow sand filtration remove between 93% and 100% of Giardia; with Cryptosporidium, removals have reached between 99.99% and 99.997% [

32]. It is discussed, based on epidemiological evidence, that the levels of Giardia cysts that persist in drinking water (0.11 cysts/L) after slow sand filtration processes are insufficient to cause infections [

33].

Therefore, to achieve the objective of implementing a rainwater harvesting and treatment system under the One Health approach, with the support of the Altos del Cabo by Fondacio Foundation, efforts were made to improve access to water resources for the population involved in the foundation’s development education programs, as well as to optimize health conditions in a community lacking access to potable water. To advance the One Health approach, the team relied on Service Learning (SL) as a socio-technical methodology designed as a teaching-learning strategy that promotes community participation in social initiatives [

34]. In these activities, it is essential for the community to be organized and clearly aware of its needs so that, through multidisciplinary projects supported by a structured curriculum, a solidarity-based service is provided within the territory. This approach seeks to avoid dependency and instead foster empathy and social commitment skills among students [

35].

Projects framed within the SL methodology are seen as curricular proposals oriented toward active student and faculty participation in a pedagogical framework that guides the experience from classroom work to communities in need [

36]. This allows the student to acquire disciplinary and community work competencies while developing skills in dialogue, empathy, understanding, and a comprehensive view of a physical and social territory [

37].

This experiential approach expands the academic setting into communities, enabling students and faculty to collaborate based on identified needs within the region [

37]. It fosters spaces for open dialogue where ideas are freely shared within networks of trust, consolidated under faculty supervision. In this context, the faculty's role is to guide students in systematizing information and transforming it into knowledge [

36].

This educational approach provides students with an opportunity to acquire competencies in value formation, cooperative and supportive work, while strengthening their disciplinary knowledge through practical experience and the application of learned concepts to the populations in need [

34]. Thus, SL allows for serving society through well-structured community projects with a clear pedagogical orientation in training. SL projects must consider unique characteristics under this participatory approach, such as inclusivity, replicability, collaboration, transferability, and the promotion of partnerships and community-level improvements [

38].

SL facilitates the development of both human and disciplinary skills through education and community work, resulting in significant achievements and positive impacts. Moreover, it boosts community self-esteem by involving them from the project's inception to its completion, strengthening territorial confidence and improving the community's capacity to address local challenges and enhance quality of life [

39,

40]. The knowledge transfer in SL is inherently social, as learning is derived from interaction with others, and the knowledge acquired is socially constructed by previous individuals. This is supported by a constructivist approach to education, where learning arises from the student's surrounding reality, using mechanisms that link concepts with problems and solutions. In social contexts, people act as agents of learning who, through specific teaching strategies, build knowledge based on an instructional design [

41]. This design is described as a systematic approach that translates learning and instructional principles into educational activities and materials [

42] pedagogical design is crucial in the educational domain, providing the guidance every mentor needs to deliver a course, regardless of its format [

43], serving as a roadmap based on learning theories selected by the responsible educators [

44].

Consequently, this work adopts a participatory approach based on the One Health framework and grounded in Service Learning (SL) to identify and prioritize the issues perceived by local residents, using territorial recognition in relation to urban sustainability indicators. Through a participatory process, a project was developed that focused on designing a prototype for rainwater harvesting and treatment, along with an instructional design consolidated into a course aimed at facilitating knowledge transfer to the involved community. This effort was conducted at the Altos del Cabo by Fondacio Foundation in the San Isidro Patios area of Bogotá, Colombia, where water scarcity affects part of the population, exposing them to diseases, social exclusion, and unsanitary living conditions.

The project, framed within the One Health approach, which promotes the health of all living beings and the environment, as well as food and water security, food safety, and water sanitation, encourages collaboration among professionals from various disciplines. This collaboration operates at all levels, from community to global, bridging gaps between sectors and institutions [

1].

1.1. Background

TECHO Colombia operates in 19 Latin American countries with the goal of overcoming the poverty experienced by millions living in informal settlements. This is achieved through the coordinated efforts of residents, young volunteers, and strategic partners. TECHO has developed rainwater treatment systems that capture and direct water to a storage tank, from which it is pumped through a chlorination mechanism designed to remove pathogenic microorganisms. The system includes a flow equalization structure to clarify the water and a contingency system to handle excess runoff from heavy rainfall events [

45].

Similarly, the use of slow sand filtration technology as a sustainable and effective method for decentralized water purification was demonstrated in the Guayabal de Síquima Project, led by Ingenieros Sin Fronteras Colombia. This project focused on improving water quality in a community in Cundinamarca, Colombia, and involved participatory action workshops for implementing slow sand filters. Fourteen units were provided, benefiting sixteen families. Results showed that this filtration system removed 90% of total and fecal coliforms during the maturation period of the filter bed. Furthermore, the organoleptic quality of the water was improved, confirming the reduction of suspended solids and enabling access to potable water for the community [

46].

In Kuychiro-Cusco, Peru, slow sand filters were used to purify river water for human consumption. Studies on the system’s implementation and water analysis showed that samples met the required technical specifications for safe drinking water. Additionally, this technology proved to be accessible, easy to use, and maintainable for low-income individuals, with an average flow rate of approximately 2 liters per hour [

47].

The organization Acción Contra el Hambre (ACF) operates in the Colombian departments of Nariño, Córdoba, and Putumayo with the mission of improving and ensuring adequate nutrition in vulnerable communities, as well as addressing water sanitation, quality, and infrastructure issues. ACF's contribution in the water and sanitation sector focuses on training, resource management, and the application of tools for water resource management. As part of this initiative, ACF has employed the large-scale distribution of water-purifying candle filters, storage tanks, and collaboration in research processes in partnership with the Universidad de Boyacá [

48].

In addition, research on technological alternatives for basic rainwater treatment for domestic use in the community council of Los Lagos, Buenaventura, Colombia, highlights the relevance of rainwater harvesting in high-precipitation areas. As part of this effort, channel and storage tank systems were installed to collect rainwater, which was then filtered using ceramic candle filters. This technology comprises two ceramic candles and two 20-liters polyethylene containers, arranged one above the other. The upper container houses the ceramic candles, which act as the filtration medium, while the lower container stores the treated water, ready for direct consumption. The community also received training on the use and maintenance of these systems [

5].

Given this context, the objective of the present work was to propose a solution to the shortage of drinking water through accessible and sustainable techniques. This proposal centers on a rainwater collection and treatment system that incorporates an initial pre-treatment phase and a slow sand filtration process for water decontamination.

1.2. Problem

Water and foodborne diseases emerge when harmful levels of pathogenic microorganisms, chemical contaminants, and other toxins are ingested through these sources. It is estimated that, globally, foodborne illnesses are responsible for 600 million cases and over 400,000 deaths annually. Similarly, waterborne diseases lead to more than four billion cases of diarrhea and nearly two million deaths each year worldwide [

1].

A fundamental aspect of water, environmental, and food contamination is the multi-sectoral management of waste, which includes a wide range of materials such as human and animal fecal matter, remains of animals that have died from disease or accidents, and domestic, industrial, and hospital waste. This issue is exacerbated by the lack of integration inherent to the “One Health” approach in water, sanitation, and hygiene management efforts [

1].

The 2022 National Water Study [

49] determined that in Colombia’s rural areas, 51% of municipalities face risks in water quality, while this figure rises to 40% in urban areas. Furthermore, in 77 Colombian municipalities, water is unsuitable for human consumption. According to the 2023 Sector Report on Public Household Services for Water Supply and Sewerage, the Water Quality Risk Index for Human Consumption (IRCA) links water quality with the risk level to which a specific population is exposed due to non-compliance with chemical and microbiological standards. Of the 1,103 municipalities analyzed, water quality was deemed suitable for consumption in 619 municipalities. In addition, 218 municipalities had low-risk levels, 154 medium-risk, 85 high-risk, and eight municipalities faced an unsustainable health risk. Notably, 19 municipalities reported no information on water quality in urban areas [

50].

The 2022 National Report on Water Quality for Human Consumption identified 207 affected municipalities across 16 departments in Colombia. Departments such as Bolívar, Córdoba, La Guajira, and Sucre reported water service issues in at least 50% of their municipalities. Seven departmental capitals—Cartagena de Indias, Tunja, Valledupar, Montería, Riohacha, Santa Marta, and Sincelejo—also faced notable disruptions. Additionally, Bolívar, Cesar, Córdoba, and Santander exhibited high recurrence categories, meaning that some municipalities reported water scarcity situations lasting more than two years. In Cundinamarca, of the department’s 116 municipalities, 67 had safe drinking water, 39 had low-risk levels, 10 had medium-risk levels, and none were classified in high or unsustainable health risk levels. The prolonged crises experienced by various cities and municipalities are largely due to unplanned urban growth that does not account for water and sewer infrastructure capacity, underscoring the need for urban planning centered around water [

51].

In 2023, the Ombudsman’s Office of Colombia reported that in 2022, at least 1.5 million people consumed water with high health risks, potentially impacting their health. Preliminary figures from health authorities in 2022 reveal concerning trends: in urban areas, water quality indices were classified as dangerous in eight municipalities and high-risk in 64 municipalities, affecting approximately 17 departments. In rural areas, the situation is even more alarming, as water was deemed unsuitable for consumption in 32 municipalities and high-risk in another 84.

Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, is divided into 20 localities, with Chapinero being the second. Located in the central-eastern part of the city, Chapinero is bordered to the north by Calle 100 and the road to La Calera, to the west by the North Highway-Avenida Caracas, to the east by the slopes of the Sierra de Cruz Verde, and to the south by the Arzobispo River. The Zonal Planning Unit 89 (UPZ 89) is located in Chapinero’s rural area and comprises four neighborhoods, including San Luis and San Isidro Patios (see

Figure 1). San Isidro Patios lies in the Eastern Hills, accessible only via the road to La Calera. San Isidro territory is divided into six sectors, none of which are legalized due to their location in a protected area adjacent to the Páramo de las Moyas. The development of this area is attributed to the presence of old stone and sand quarries, which attracted population groups working in this activity to meet the growing demand for construction materials during Bogotá’s rapid urban expansion between the 1940s and 1970s [

52].

This sector, which developed informally and without planning, is home to approximately 22,000 inhabitants and is not officially recognized as part of the city’s urban area. It faces significant urban, environmental, and socioeconomic deficiencies. The degradation and loss of the soil’s water absorption capacity, due to urban infrastructure development in an environmental reserve area, along with the pollution and depletion of existing water sources caused by direct consumption and inadequate management by residents, severely impact biodiversity [

52,

53,

54]. Additionally, residents experience socio-spatial segregation due to the lack of essential service infrastructure, limited public transportation, underdeveloped public service networks, and the absence of job opportunities, vocational training, and sustainable productive processes [

55]. Despite these challenges, this area holds valuable potential because of its location near Bogotá's financial center and the environmental richness of the surrounding reserve.

Approximately 2,500 families in this area face various challenges regarding access to and quality of public services, including illegal connections or a complete lack of electricity, sewage, and water supply. According to community leaders, around 200 households lack a water supply system and must rely on rainwater collection, wells, or, as a last resort, purchase bottled water to meet their basic consumption needs. The area has several surface water sources, including the Teusacá River and the La Amarilla and Morací streams. Although the community can access water sources for consumption, inadequate management of household waste, debris, and untreated wastewater discharges have led these sources to exhibit high levels of physicochemical and microbiological contamination, limiting their direct use. In some areas, individual wells supply certain homes, although these are not commonly found in the area.

For technical reasons associated with the water service provided by Acualcos, families not formally connected to the network often make illegal connections to the main pipeline. This affects homes located in the lower areas of the territory, as water supply reaches them with insufficient pressure, exacerbating the shortage in the sector. It can be concluded that the current rural aqueduct network is insufficient to serve all homes, which have grown exponentially due to unsustainable and unplanned land occupation.

Finally, due to the water supply problem, families store as much water as possible in tanks. However, this storage method, whether for aqueduct or rainwater, is inadequate; containers lack covers, are poorly maintained, and are dirty, creating reservoirs that foster mosquito and fly larvae. These vectors negatively affect the area’s residents, causing skin conditions, cross-contamination in food, gastrointestinal diseases, and general discomfort regarding housing and public space habitability.

2. Materials and Methods

Developing an open socio-technical work methodology that fosters participation from both the interdisciplinary student group and the communities involved is a goal of AS (Service Learning). This approach encourages students, professors, and social collectives to learn how to respond cooperatively and creatively to water resource scarcity issues in the Altos del Cabo by Fondacio area in San Isidro Patios [

56]. This is achieved by participating in the design and implementation of projects framed around ethics, social and environmental responsibility, and the integrative "One Health" approach.

The following outlines the six-phase AS methodology proposed by [

56] designed to promote participation and dialogue among students, faculty, and the community to transfer a rainwater harvesting and treatment system with a "One Health" focus.

Phase 1: Participatory Territory Identification

The first phase involves territory diagnosis and planning by implementing tools to gather primary data. This is crucial to establishing a realistic scenario that reflects the behavior of the sector based on the needs expressed by residents, using quality-of-life indicators. Action research related to qualitative research supports this process, aiming to provide information for community-based decision-making, encourage social change, and enable individuals to recognize their role in shaping their territory [

57]. This phase unfolded through:

Contextualization: Understanding the problem’s setting through analyzing social, economic, environmental, and cultural factors in collaboration with teachers and students.

Observation: Collecting data through direct observation from three site visits and indirect methods, such as reviewing literature.

Document Analysis: Reviewing relevant documents, reports, statistics, and other records regarding water resource access issues faced by a segment of the community.

Focus Group Identification: With support from staff at Altos del Cabo by Fondacio, the project participants were identified as individuals engaged in community processes promoted by this organization within the territory. The research convened 50 community members from San Luis Altos del Cabo de San Isidro Patios, located in the Chapinero locality of Bogotá, Colombia. Additionally, the group included six civil engineering students and three professors; three architecture students and one professor from the Universidad Católica de Colombia; two civil engineering students and two bioengineering students from the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium; one professor from the Film and Television program at Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano; one professor from the Ecology program at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; and one civil engineering professor from the Universidad Federal de Integración Latinoamericana in Brazil. This sample was established from a methodological perspective that employs non-probabilistic sampling.

Non-probabilistic sampling, a strategy in which study participants are not selected randomly but rather intentionally or for convenience, was employed in this project. This approach considered the project's objectives, research characteristics, the investigators' interests, and the specific traits of the accessible population. In this research project, which engaged students, faculty, and community members, the approach was applied as follows:

First, an intentional selection process was carried out using convenience sampling. Students and faculty members were chosen because they belonged to the educational institutions involved in the project, while community members were selected based on their active participation in initiatives led by the Altos del Cabo by Fondacio Foundation in the area. Second, a criterion-based sampling method was implemented. Students from disciplines such as civil engineering, bioengineering, and architecture who expressed interest in participating were included, as these profiles were essential for addressing issues related to basic sanitation, housing infrastructure, and public spaces. Faculty members were selected based on their experience in community projects and expertise in basic sanitation, habitability, and community education. Community members who faced challenges with water scarcity for consumption and water-related diseases were included in the sample [

57].

This sampling strategy was chosen due to the limited access the research team had to the entire population of San Isidro Patios. Conducting a probabilistic sampling of all members was unfeasible due to security conditions in the area and the resources available for the project. Non-probabilistic sampling was more cost-effective, given economic, personnel, and logistical constraints that hindered the team's periodic access to the sector. Moreover, most key community stakeholders affected by water scarcity were already organized through community education processes led by the Altos del Cabo by Fondacio Foundation, which facilitated the technical, participatory, and educational aspects of the project's implementation.

- 5.

Approvals and Permissions in the Territory: A consent form was presented to the community to secure ethical approval from participants for the study, following prior authorization from the ethics committee of the Universidad Católica de Colombia and the management and leadership of Altos del Cabo by Fondacio. Regarding ethical considerations, it was ensured that individuals involved in the project faced issues with water supply for human consumption. Participants were informed through written consent that the information gathered during the project would be handled confidentially and anonymously, as the data would be used exclusively for academic purposes. They were also reminded of their right to withdraw from the process at any time without penalties or the need to provide an explanation for their withdrawal. Furthermore, in collaboration with the staff of the Altos del Cabo by Fondacio Foundation, efforts were made to promote the participation of vulnerable groups, such as women, children, and the elderly, in the project.

- 6.

Territorial Analysis: Assessing sociocultural, socioeconomic, regulatory, environmental, and spatial variables for a comprehensive project context.

- 7.

Use of Tools for Primary Data Collection: These sessions were supported by the methodology proposed by [

58], whose main objective is to collect field data, taking into account a series of variables organized to characterize urban territories. This method guided field observations in collaboration with the community.

- 8.

Identifying Territorial Issues: Characterizing and engaging with community leaders, networks, and organizations to understand quality-of-life conditions.

- 9.

Comprehensive Problem Definition: Addressing neighborhood informality and its impact on urban livability and residents' quality of life.

Phase 2: Problem Scenario Recognition and Analysis

This phase focuses on identifying and understanding problematic situations to prioritize them through participatory techniques like focus groups. Aligned with action research principles [

57], this phase entails creating a solution to improve access to potable water, based on territory characterization:

Interpretation of Results: A situational framework for the territory was established based on urban habitability indicators that characterize informal urban environments.

Identification of Patterns or Themes: Patterns were identified by prioritizing indicators and their relationship to the territory’s informality, aligning with residents' perceptions. Indicators were voted on and ranked as high, medium, or low priority to enhance habitability conditions and thus improve the quality of life through a "One Health" perspective. This prioritization highlighted several thematic areas requiring attention within the territory.

Clear Communication of Field Data Collection Results: An analysis report on the indicators was created and delivered to Altos del Cabo by Fondacio, which detailed the causes, consequences, effects, and conclusions derived from the findings in the territory, supporting the project’s focus on water quality for human consumption under the "One Health" framework.

Phase 3: Characterization and Enhancement of Skills and Resources

Students, professors, and community members engaged in an atmosphere fostering idea exchange, which led to adaptive designs and actions aimed at providing creative solutions to the identified issues. Based on the three phases of action research, the CDIO methodology was applied as proposed by [

59]. The community-selected priority issue, chosen for its relevance, was the supply and quality of water for human consumption, particularly in terms of rainwater harvesting. A rainwater collection and treatment system was conceptualized, addressing water scarcity issues that impact habitability through the availability of basic services, hygiene, and vital consumption, reducing health risks. The following activities were conducted:

Definition of Technical Requirements for Rainwater Collection and Treatment: This was tailored to the community's situational framework by reviewing treatment system proposals from TECHO Colombia [

60]

Establishment of Raw Materials and Supplies for Technology Transfer: Based on reviewed rainwater collection and filtration technologies, a list of materials was created in collaboration with involved students and professors.

Modeling of a Rainwater Collection and Treatment System Design: The design was based on collected information and adapted to community needs.

Presentation of the Proposed Design to the Community: Altos del Cabo by Fondacio was chosen as the site for the pilot construction, allowing community members to monitor, adjust, and later replicate the system in their homes.

Phase 4: Project Design

This phase involved planning a project proposal that ensures community service activities linked to mutual learning among students and community members. The design phase was articulated with the CDIO methodology of [

59] and the professors and student teams completed the following activities:

Modeling Habitability Characteristics for Altos del Cabo by Fondacio: This included analyzing spatial distribution, roofing conditions, gutters, and rainwater storage tanks.

Design Plans for the Rainwater Collection and Treatment System: These detailed plans allowed for the system’s appropriate placement within the foundation’s headquarters.

Budget Development for the Rainwater Collection and Treatment System: A detailed budget was created for system construction at the foundation site.

Construction Planning in Collaboration with the Community: A collaborative plan for building the rainwater system at the foundation site was developed.

Phase 5: Model Implementation

This phase aimed to transform ideas into tangible realities and was crucial for developing the AS methodology and project implementation, with consistent support and oversight during execution. Using the third phase of action research and the CDIO methodology, the rainwater collection and treatment system was implemented at Altos del Cabo by Fondacio, designed to enable replicability within the community.

Formation of Work Teams: Professors, students, and community members formed teams to construct the system at the foundation’s facilities.

Preparation of the Foundation’s Physical Space: The foundation’s space was adapted, materials were acquired, and these were prepared and stored with community support.

Delegation of Construction Roles: Roles were assigned according to pre-defined models, ensuring structured and collaborative system assembly.

Participatory System Construction: The community actively participated in constructing the system.

System Adjustments: Additional accessories were adjusted to optimize functionality.

Official System Presentation in the Territory: Altos del Cabo by Fondacio led an event showcasing the system, attended by community organizations, foundation volunteers, students, and faculty members.

Phase 6: Project Closure and Knowledge Multiplication

The final phase evaluated the project's completion according to the scope agreed upon with the community, with knowledge transfer being essential to enable replication. Recognizing the need for participatory educational spaces aligned with a constructivist approach, an educational model was proposed, designed to work in collaboration with the community and linked to the community processes of Altos del Cabo by Fondacio. This methodological approach underscores education as fundamental to transferring the rainwater collection and treatment system knowledge within a region facing frequent potable water shortages. The instructional model was structured following [

42] and included the following steps:

Step 1: Analysis. This step focused on identifying and understanding a specific issue and exploring potential solutions, guided by the needs assessment from Phase 1. The result was a list of instructional objectives that directed the knowledge transfer proposal's design and implementation.

Step 2: Design. In this stage, a detailed outline was created to achieve the instructional objectives, specifying key elements such as the target audience and context. The final plan included clear goals, instructional strategies, and a sequence of activities.

Step 3: Development. Educational transfer plans and materials were created, producing instructional resources and preparing materials for the teaching-learning process.

Step 4: Implementation. The instructional design was executed within the community, focusing on content comprehension, skills acquisition, and knowledge transfer.

Step 5: Evaluation. The process concluded with an evaluation to determine the effectiveness of instruction. A formative evaluation was conducted throughout the educational model’s development to improve knowledge transfer. Each teaching strategy was evaluated to ensure alignment with the constructivist approach, emphasizing learning grounded in the student’s reality.

3. Results

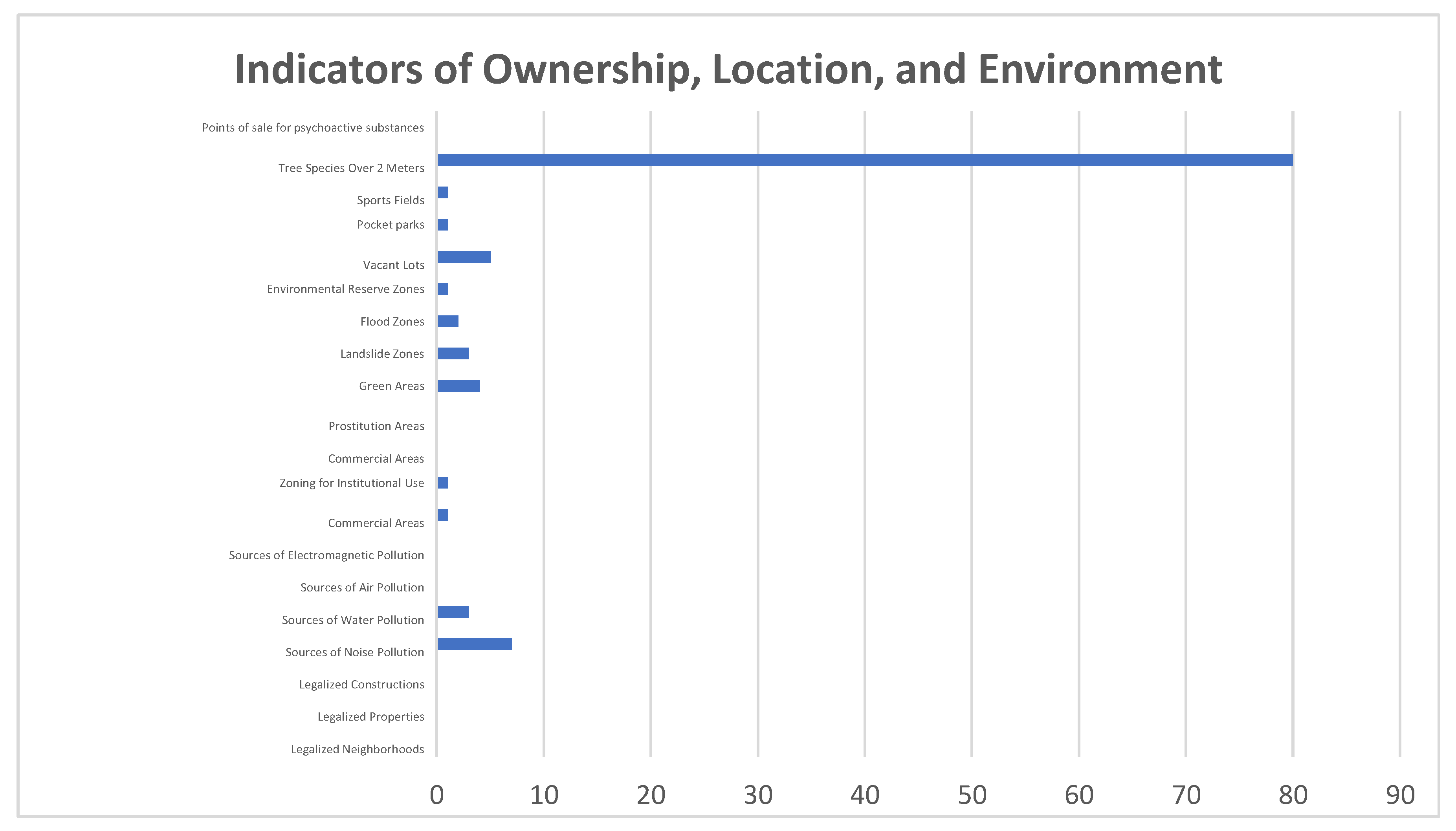

This research involved a participatory territorial assessment based on the “One Health” approach. This process analyzed 20 indicators related to land tenure, location, and the environment of the settlements (

Figure 2). The purpose of this evaluation was to determine the ability of these settlements to meet basic housing needs while minimizing adverse impacts on residents' well-being at the urban level. Additionally, the study examined land use and distribution, considering the housing dynamics inherent to the informality of the area.

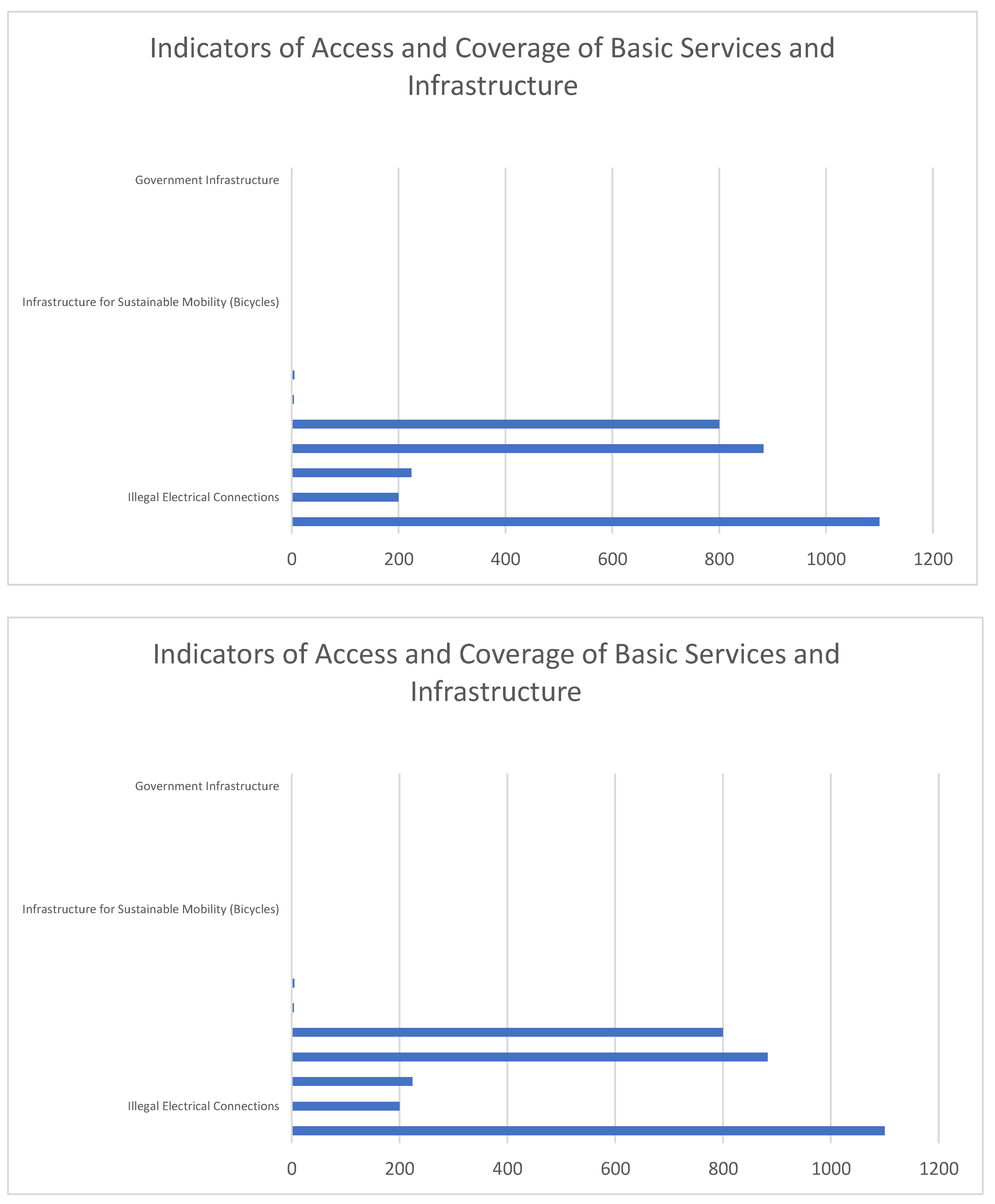

Secondly, 15 indicators related to access and coverage of basic services and infrastructure were identified (

Figure 3). These indicators are essential for ensuring the infrastructure meets the hygiene, comfort, and public utility needs of the city's inhabitants, with the aim of improving their quality of life and health.

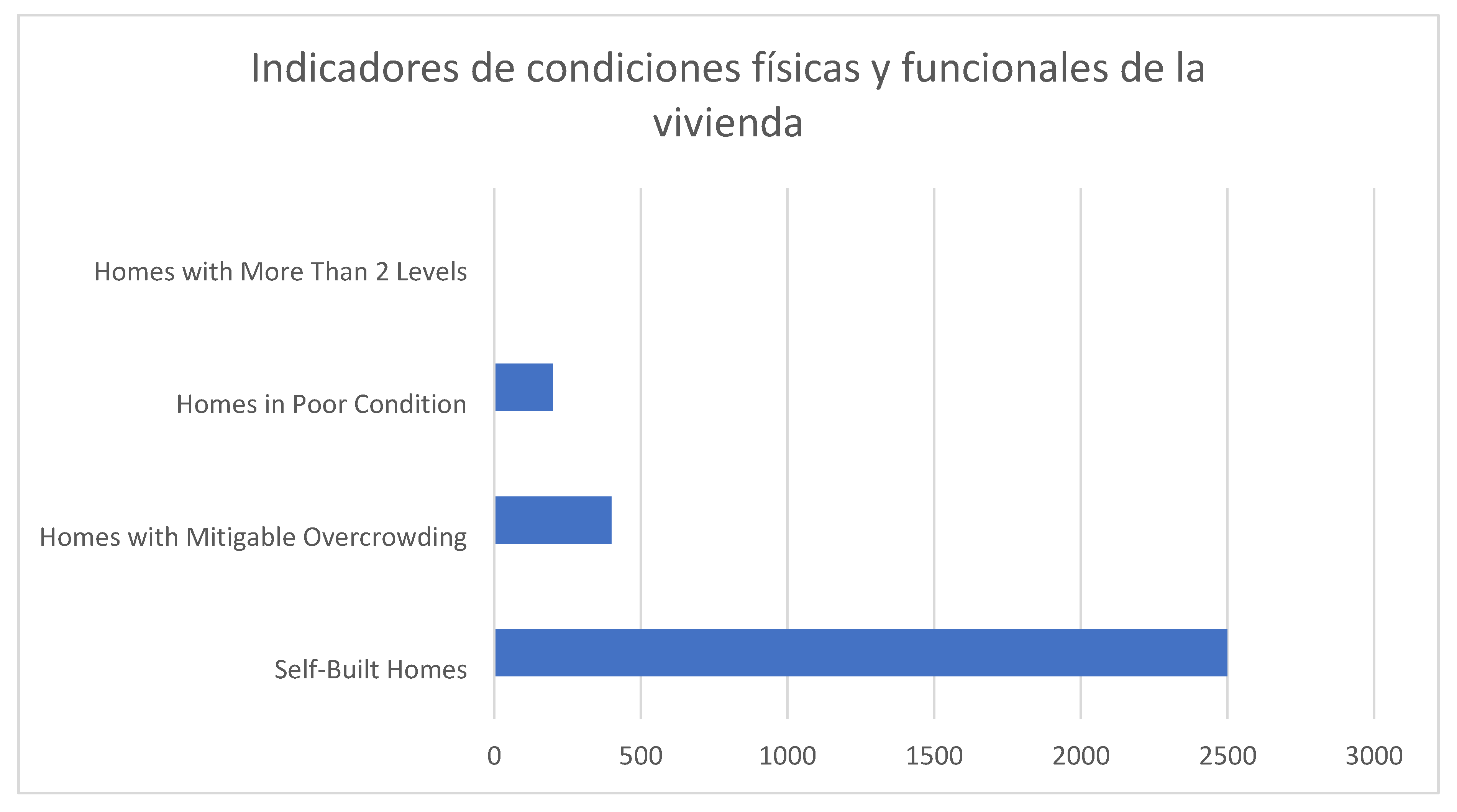

Finally, four indicators related to the physical and functional conditions of housing were analyzed (

Figure 4). These indicators facilitate interactions among inhabitants, both within their families and with their neighbors, promote privacy, and help prevent or mitigate physical and mental health issues among residents.

Considering this situational framework, a participatory process was conducted to prioritize the areas where the community requires support to improve their living conditions and quality of life. This prioritization is detailed below:

High Priority:

Water Supply and Quality for Human Consumption: Focus on rainwater collection in the territory.

Improve the Color Quality of Drinking Water.

Control Pollution in Surface Water Bodies.

Legalization of Neighborhoods, Properties, and Housing in the Area.

Expand the Sewage Network to Homes Lacking This Service.

Address Localized Mass Movement and Flooding Issues in Collaboration with District Entities.

Regulate Open Disposal of Solid Waste and Debris.

Address Homes in Poor Condition, Tackling Issues Related to Construction Materials and Overcrowding.

Improve Access to Preventive Health Programs in the Community.

Legalize Informal Connections to the Water Supply and Electricity Networks in Homes.

Medium Priority:

- 11.

Enhance the Road Infrastructure of Secondary Roads and Sidewalks in the Area.

- 12.

Establish Cleaning Brigades in Protected Areas and Surface Water Sources.

- 13.

Include Commercial Areas in Environmental Education Programs Related to Waste and Noise.

- 14.

Promote Public Space Recovery Processes in Vacant Lots.

- 15.

Create Partnerships for the Construction of Pocket Parks and Multi-Sport Fields.

Low Priority:

- 16.

Review the Use of Propane Gas in Homes and Its Possible Impacts.

- 17.

Classify Tree Species Over Two Meters in Height and Assess Their Risk Levels.

Following the prioritization of these topics, the primary focus of the project developed jointly with the community was determined to be rainwater harvesting and treatment. This need was identified as urgent by residents, who emphasized the importance of academic support to propose a solution adapted to the territory's living conditions, aligned with the integrative "One Health" approach.

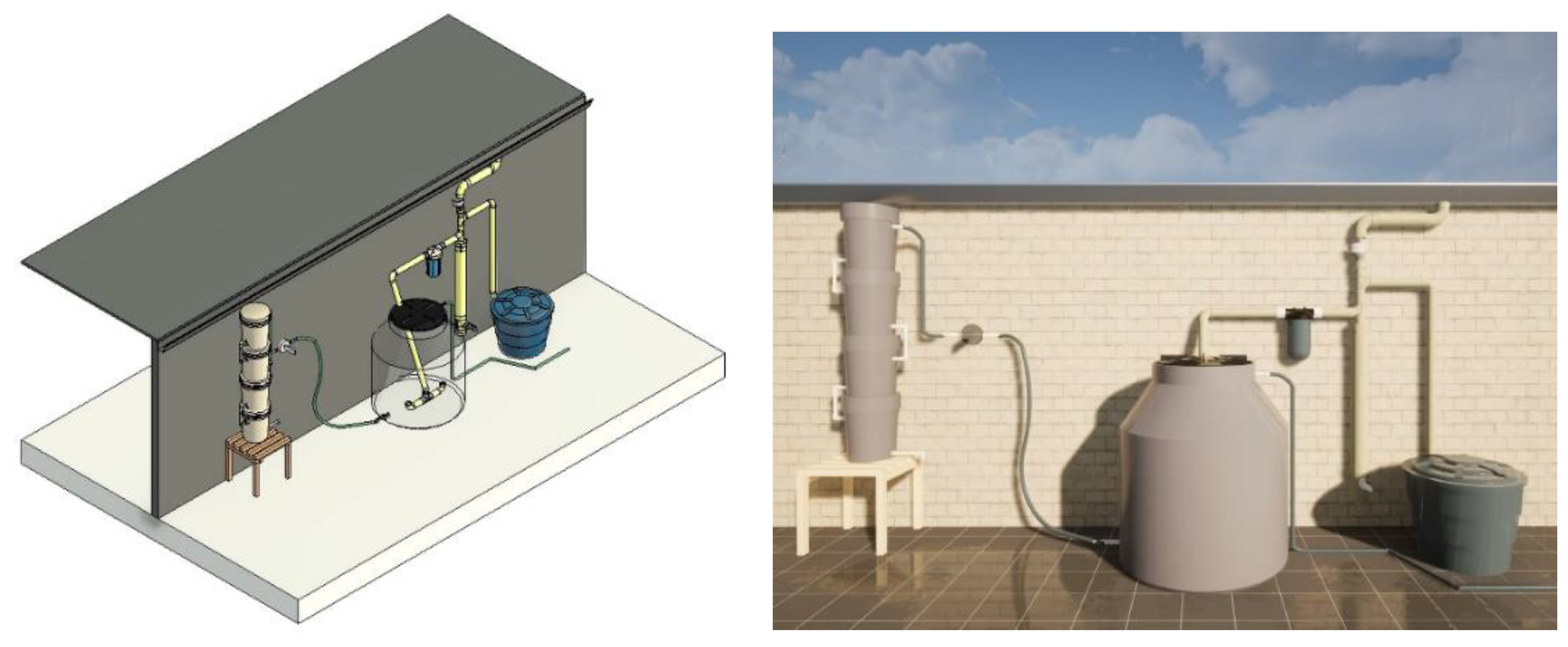

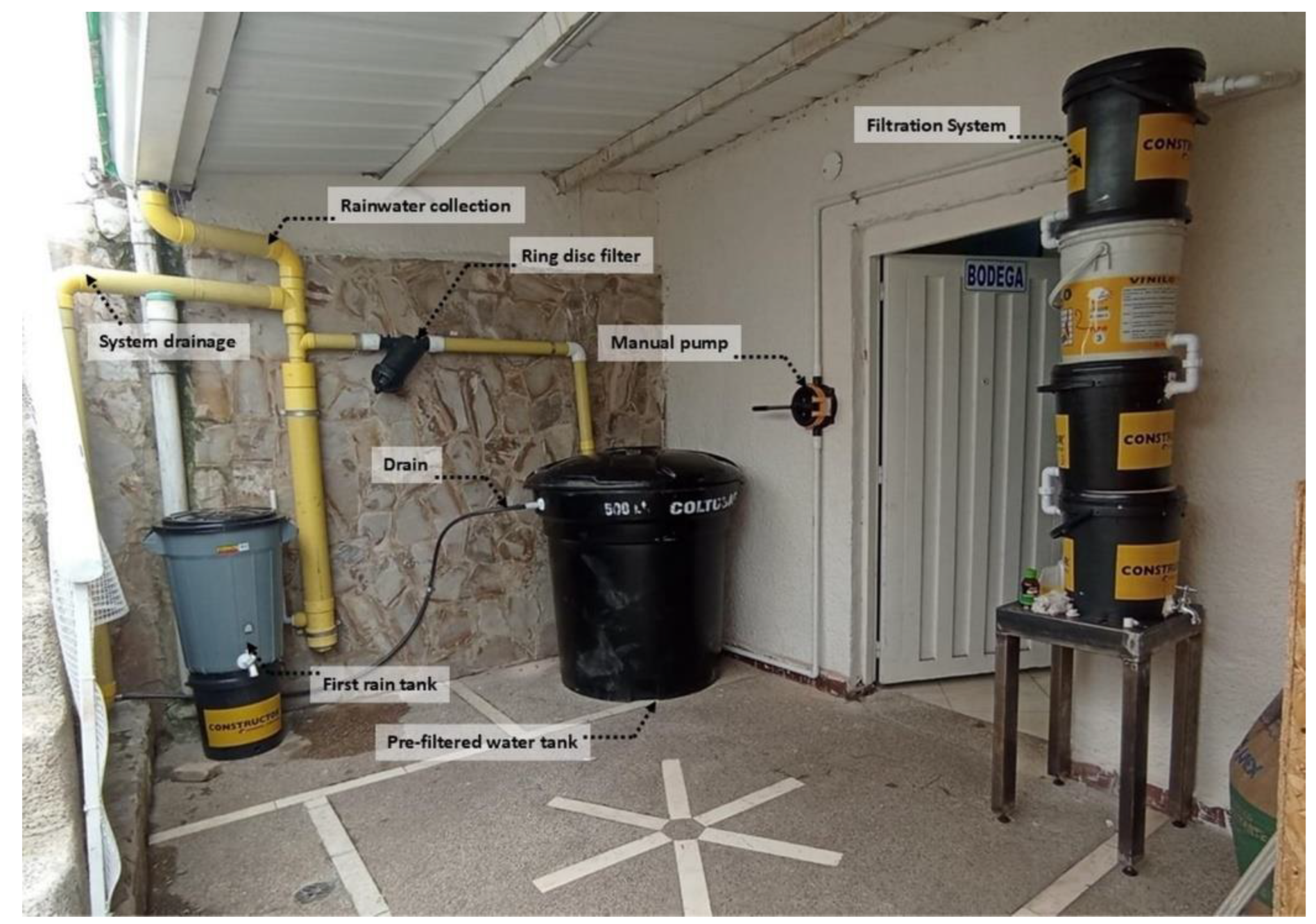

As a result, within the methodological framework, a rainwater collection and treatment system was designed, comprising four phases.

Phase 1 Initial Rainwater Collection and Purification: Focused on removing large organic materials like leaves, branches, and other particles from rooftops, which contain high levels of contaminants. A gutter and pipe system channels the first rainwater into a tank for purification.

Phase 2 Pre-Filtration: This phase removes smaller suspended solids from the water and regulates flow during heavy rainfall. A drainage system acts as a contingency to manage overflow in the first rainwater and prefiltered water tanks.

Phase 3 Prefiltered Water Storage: Water is stored in an equalization tank where, through gravity, remaining suspended solids settle at the bottom.

Phase 4 Filtration: The water undergoes a filtration process using a system proposed by [

60], capable of removing approximately 98% of dissolved solids affecting the water's organoleptic and microbiological characteristics.

With the treatment phases defined, a list of raw materials and supplies was prepared, enabling the modeling of the system's design (see

Figure 5).

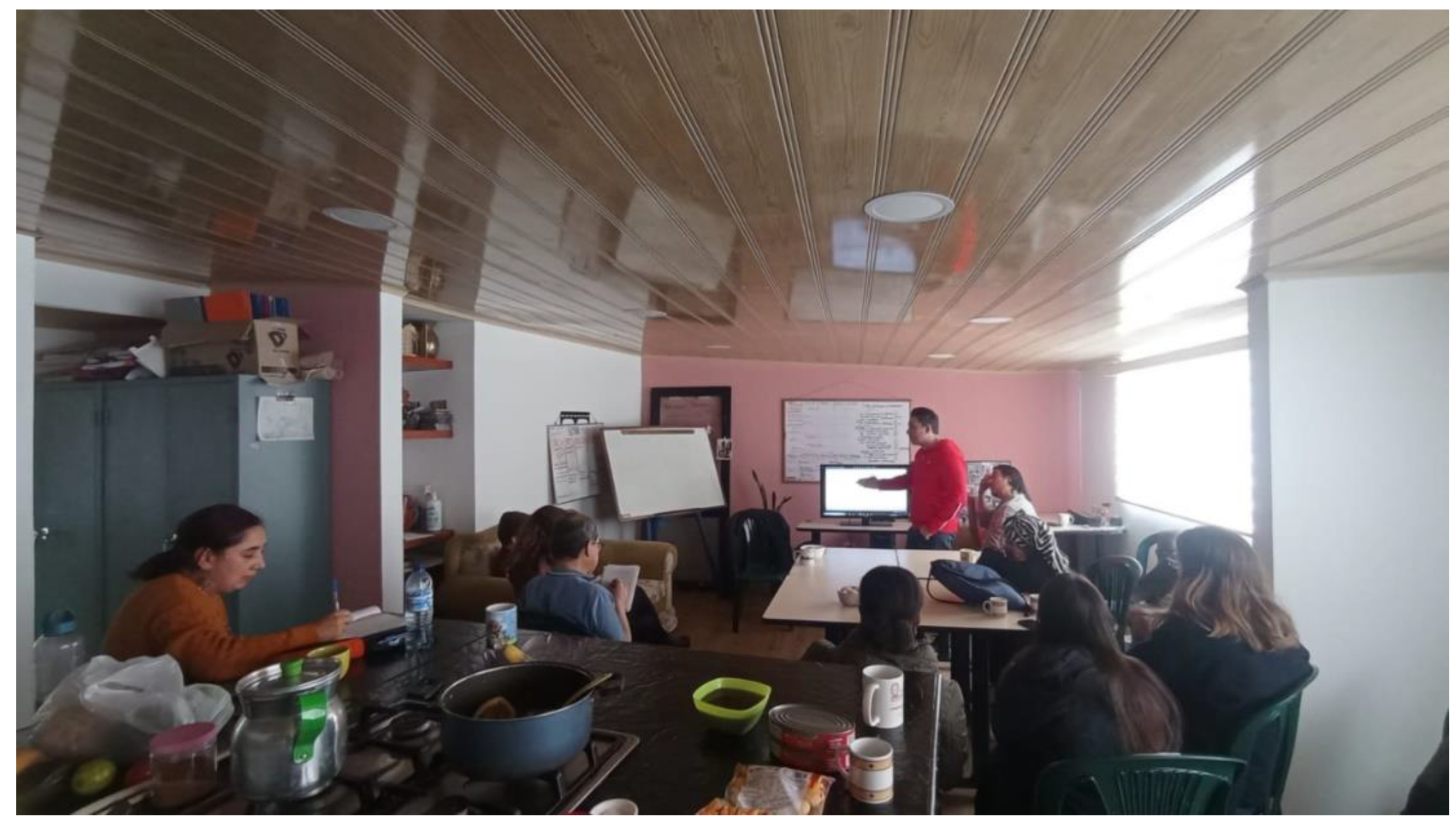

With the proposed system model in hand, it was presented to the community to address concerns, gather feedback, and determine its construction site within the facilities of Altos del Cabo by Fondacio, which is responsible for scaling up the pilot plan in the area (see

Figure 6).

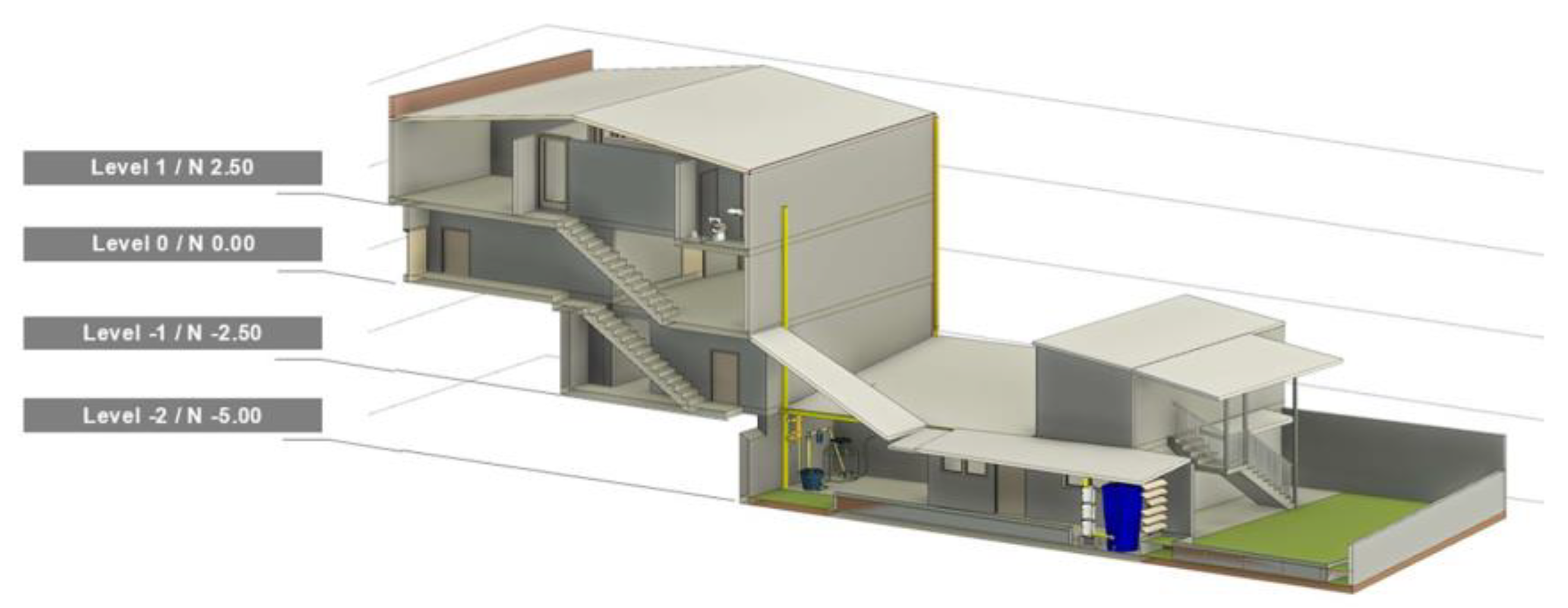

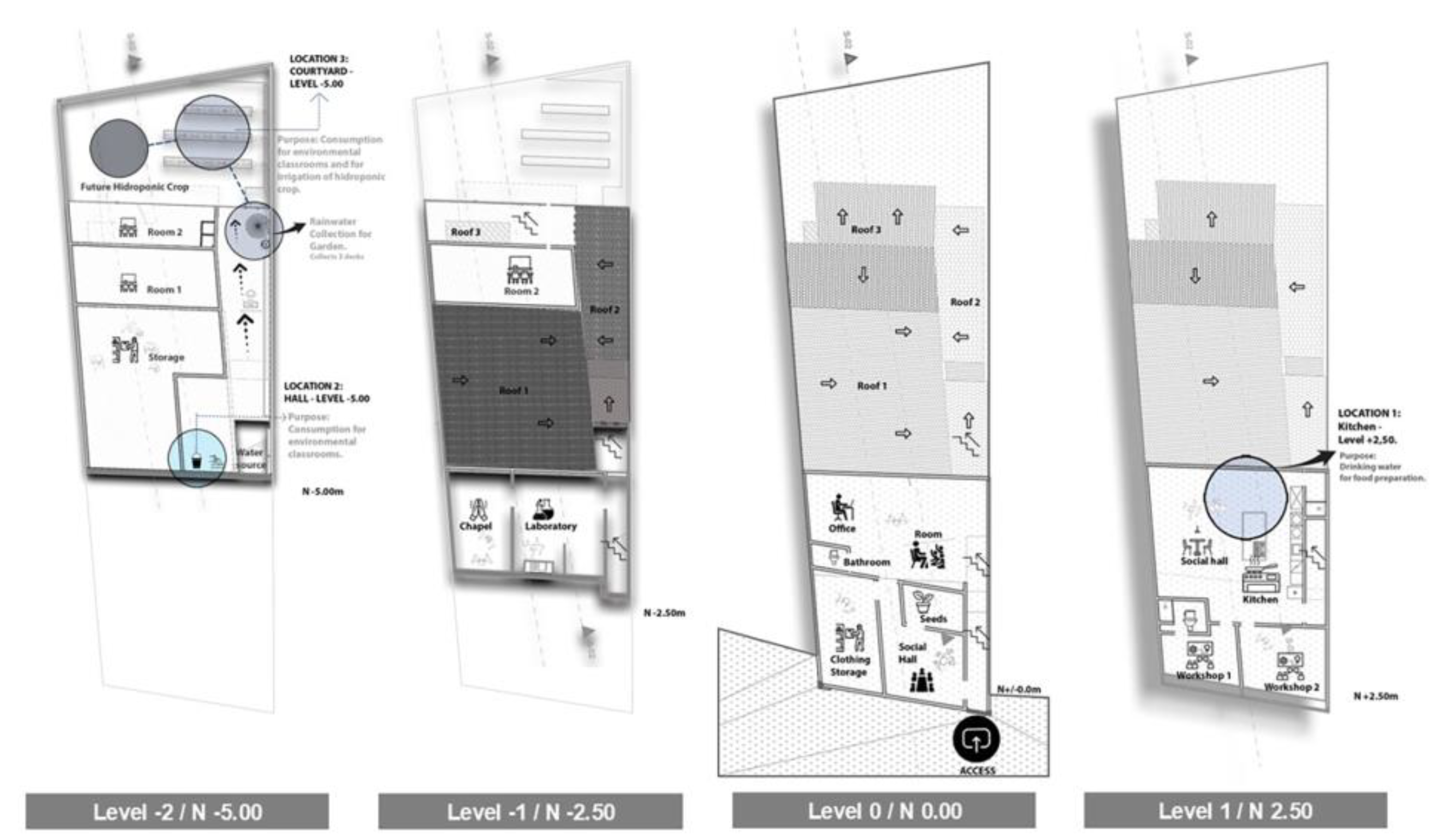

After conceiving the model for the rainwater collection and treatment system among team members and the community, the system's design was developed and implemented within the foundation's facilities. This involved modeling the habitability conditions in relation to the spatial distribution of the infrastructure, establishing various locations for the system to capture the maximum amount of precipitation per area on the roof, along with factors related to habitability and safety in the housing (see

Figure 7).

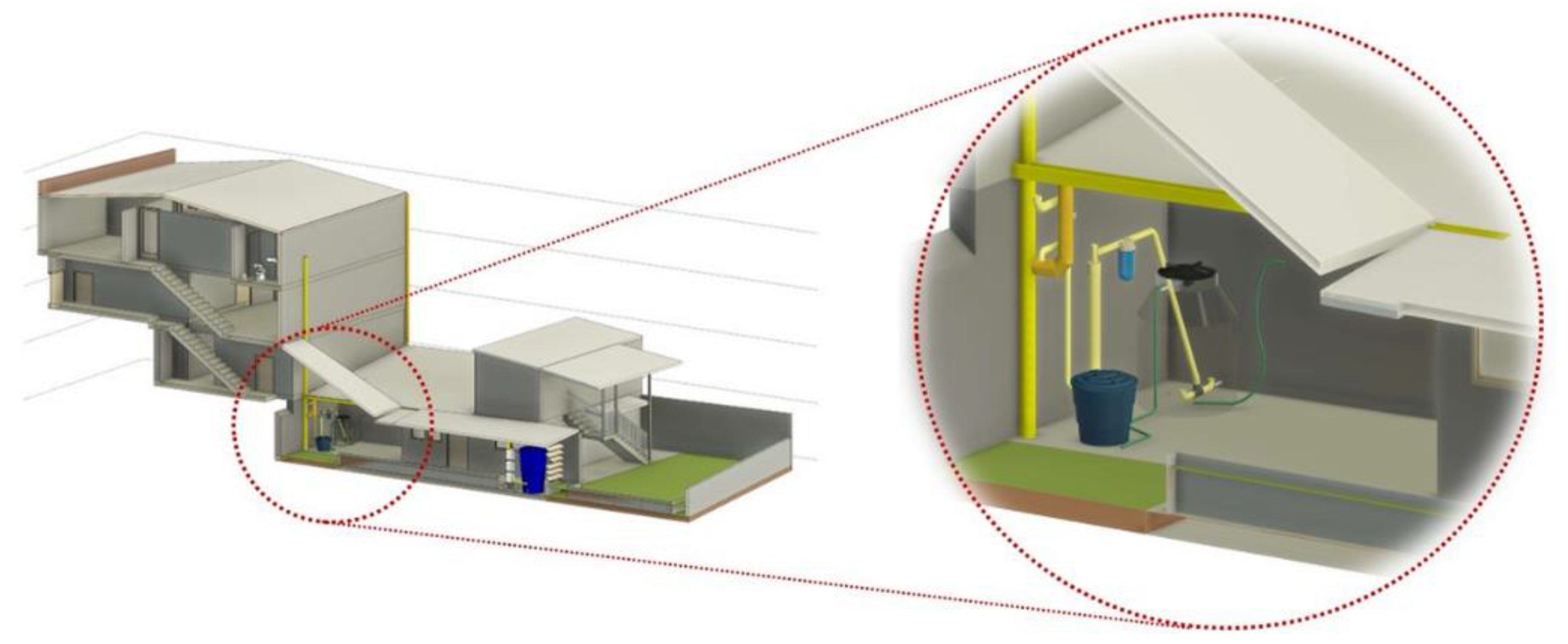

After presenting the modeling conducted for the foundation's facilities, the best location for the system installation was collaboratively determined, taking into account several parameters: live loads on the structure, roof area, ease of collection and transportation of treated water, available space for constructing the system, and the proximity of the overflow contingency mechanism to a drainage system in case of heavy rainfall. Based on these considerations, it was concluded that the system should be placed on the first floor at the rear near the nursery (see

Figure 8). This allowed for measurements to be taken within the foundation's physical plant to define the schematic plans for the system to be constructed (see

Figure 9).

From the preparation of the plans, the required quantities of supplies, resources, and raw materials were calculated, enabling the analysis of unit prices and the definition of the system's budget, estimated at approximately $1,400,000 Colombian Pesos, equivalent to 350 US dollars. Subsequently, the necessary materials were procured from local commercial areas, promoting support for local businesses and reducing transportation costs. The construction of the system was collaboratively planned with the community, dividing participants into three teams. The first group was responsible for preparing materials and supplies; the second handled the construction of the collection and pretreatment system; and the third group undertook the task of building the filter for the final treatment of rainwater, following the proposed system design.

During the implementation phase, the site was adapted according to previous models, and construction was carried out in collaboration with the community, adhering to the proposed design and following the participatory planning process (see

Figure 10). Adjustments were made to the prototype's polyvinyl chloride (PVC) fittings based on real-time monitoring of its performance, effectively capturing and treating rainwater.

Regarding the location of the system, it was built considering key factors such as the available space, accessibility for collecting treated water, a 9 m² roof surface, and the structure of the walls for anchoring the system. The community's ease of access for training on the construction, use, and maintenance of the prototype was also taken into account. The results showed that the system is functional in terms of both location and operation, successfully decontaminating rainwater for everyday hygiene and consumption activities, thereby minimizing exposure to pathogens that cause waterborne diseases. The community was emphasized that the treated water is safe, as long as additional household disinfection methods, such as boiling or adding chlorine, are applied.

Regarding the improvements in the quality of the treated rainwater, the system managed to adjust the color values, reducing platinum-cobalt units from 25 to 3, while also improving the water's odor and taste. Turbidity decreased from 25 nephelometric units to 2, and the pH level increased from 6 to 7.2. Although no microbiological analyses were performed, the achieved turbidity and pH parameters ensure the safe application of household disinfection methods. These results suggest that the proposed system can significantly contribute to improving public health conditions by preventing water-related diseases, as addressed in the educational proposal.

Once the pilot system was implemented at the Foundation, a knowledge transfer strategy was designed for the community through a course titled Healthy Housing and Safe Water. After applying the closure and multiplication method of the AS approach, the following results were obtained:

The main identified issues were presented, as well as the proposed educational objectives. The difficulties observed by team members regarding the project's scope included:

The residences have serious problems with potable water supply and lack adequate systems for rainwater collection. This is due to the absence of technical assistance in the design and construction of the houses, the overload of the local aqueduct from the high number of users, and the community's lack of awareness regarding proper hygiene practices, leading to unsanitary conditions in the homes.

There was disorder and a lack of cleanliness in the wet areas of the homes (kitchen and bathroom), resulting from the residents' low interest in applying hygiene and food handling practices.

Some homes utilize rudimentary systems for rainwater collection, which are deteriorated and do not include any treatment for the collected water.

Water storage for human consumption occurs in poorly maintained containers, without protection against external contaminants.

These issues are prone to generate diseases among residents, such as gastroenteritis, respiratory illnesses, skin infections, and vector-borne and pest-related pathologies [

61]. Therefore, the learning goals established to address these difficulties were:

Integrate the risk factors present in the homes into an educational program that materialized in a participatory course. This course aimed to identify the elements that directly impact the health of residents and contribute to the unsanitary conditions arising from a lack of potable water.

Raise community awareness about the risks present in their homes, helping them to grasp and understand the negative effects these factors have on individual and family health.

Build a rainwater collection and treatment system that guarantees a safe water supply to communities facing resource scarcity.

Additionally, the characteristics of the participants were described. 60% were women, aged between 20 and 40 years. Given the youth of the group, it was deemed essential to implement pedagogical strategies that maintained their interest and motivation, suggesting flexible hours to facilitate attendance. The remaining 40% were adults aged 41 to 75, of whom 10% had not completed basic education, and 12% lacked any formal educational level. Moreover, 57% of the participants were unemployed, while 43% worked in the informal economy.

Based on the aforementioned information,

Table 1 outlines the learning units, their objectives, duration, and the topics covered to transfer knowledge about the system.

Based on the established learning units, the following instructional objectives were defined to communicate to the participants:

Identify the risks associated with water supply in housing that may lead to diseases for residents.

Encourage collaborative work in applying acquired knowledge, promoting good practices in the realm of healthy housing.

Understand the magnitude of water-related problems, linking housing and its environment to factors that directly impact health and negatively affect quality of life.

Strengthen cooperation and trust networks within the community.

Promote alternative water supply systems that contribute to improved health, especially among vulnerable groups.

Encourage processes that foster autonomy, empowerment, and community organization.

Incentivize the creation of easily constructible and replicable technological solutions for rainwater harvesting in the area.

Improve unhealthy habits at the household and individual levels through the implementation of good practices.

Highlight the importance of avoiding dependency on aid, valuing the efforts and resources contributed by community members.

Subsequently, a logical structuring of the contents was carried out for each teaching unit.

Table 2 details the topics developed during fieldwork.

Finally, the didactic strategies implemented for the community transfer course were determined.

Table 3 breaks down the didactic strategies carried out.

Finally,

Table 4 details the evaluation criteria used for each didactic unit of the course, with the aim of implementing formative assessment.

4. Discussion

Among the validated indicators of land tenure, location, and environment in the area, it was observed that the region consists of six neighborhoods, none of which have been legalized. Seven fixed sources of noise pollution were recorded, including six bars and a school. Additionally, three polluted surface water bodies were identified, including a river and two streams, which receive domestic wastewater. Over 80 tree species were counted in the area, primarily non-endemic pines that exceed two meters in height. This territory is located within an environmental reserve, the Páramo de las Moyas. Furthermore, a commercial area was identified, comprising ten establishments, including two hardware stores, two bakeries, an auto repair shop, and five stores selling food and cleaning products. A designated area for public facilities was also identified, which includes 13 properties such as a school, four daycare centers, four community halls, a health center, and three churches. Five vacant lots, designated for construction, were noted, along with a pocket park, a football field, and four green spaces considered unsafe by the community. Additionally, three landslides were recorded due to mass movements, and two settlements face flooding due to the region's high precipitation.

Regarding non-existent indicators, no sources of air pollution or electromagnetic waves were found. Similarly, there were no prostitution zones, industrial areas, or drug-selling points. No narrow alleys were observed, and none of the properties or buildings are legalized.

As for the indicators of access to and coverage of basic services and infrastructure, it was found that, of approximately 2,500 households, about 1,100 are illegally connected to the water supply system, with 224 of them lacking access to potable water. The water service provided by Acualcos frequently faces discoloration issues, especially during the winter months. Furthermore, around 883 households lack access to the public sewage system and instead use septic tanks. Four open waste disposal points were recorded, three of which are located in surface water bodies and one in a green space. Additionally, 800 households lack access to natural gas and rely on gas cylinders for cooking, while 200 households are illegally connected to the electricity service. The area has five access roads, three of which are primary and two secondary, all in poor condition. Only one basic medical center serves the community, along with a space dedicated to promoting music and the arts, located in Altos del Cabo by Fondacio. On the other hand, the territory lacks essential infrastructure such as bike lanes, sports centers, police stations, an emergency and disaster management system, libraries, and local government service centers.

Regarding the physical and functional conditions of housing, it was observed that the homes have a portico structure made of block and reinforced concrete, with self-construction being the norm for the 2,500 housing units. Approximately 400 of these homes experience overcrowding, housing more than seven people in spaces without proper separation. Moreover, 200 homes show deterioration in walls, roofs, and facades, and the buildings are no taller than two stories.

The participatory exercise revealed that the water-related issues in the area, particularly regarding human consumption, encompass various aspects that extend beyond housing, including the environment and the unsustainable relationship between the inhabitants and the land. This participatory process enabled the identification of the necessary conditions for the sustainable development of daily life. Thus, addressing water quality as an issue involves interconnected factors related to the territory, such as mobility, land use, urban services, availability and quality of public space, economic, social, and cultural dynamics, safety, the environmental context, the stability of structures, and the landscape, among others. This systemic approach, which promotes the One Health framework, highlighted the need to address a priority issue for the community, which, although focused on water quality, has a direct and indirect impact on other challenges within the territory, reinforcing the relevance of the One Health approach for this project.

By approaching water quality through the One Health framework, a clear, participatory, and structured approach was implemented, allowing the identification of critical conditions that affect the sustainability of the territory, especially in communities where land occupation and appropriation have occurred informally. This approach not only facilitated understanding the neighborhood's urban configuration from an integrative perspective but also allowed participants to connect their knowledge to local issues. At the same time, the community realized that many of their difficulties stemmed from poor housing conditions and the informality of the territory. Thus, the prototype for improving rainwater quality became not only a technical solution but also a knowledge transfer tool, demonstrating that quality of life depends on a set of territorial factors that must be managed to ensure sustainability and improve public health, preventing water-related diseases. This outcome can be considered a best practice related to the integrative One Health approach and distinguishes this project from others that aim to improve water quality but focus solely on treatment technology as an end, rather than as a means to educate the community.

The One Health approach, combined with a constructivist educational strategy, allowed for a deeper evaluation of the critical situations within the territory, avoiding paternalistic perspectives and imposed solutions that do not fit the local socioeconomic context. This approach facilitated knowledge transfer and community processes framed within water resource management, aiming to improve living conditions from a public health perspective. Determining a baseline of the project's context to prioritize issues arising from the community's felt needs must be considered a differentiating factor from other projects with similar goals, as none of the consulted projects incorporated the intersection of housing issues with water resources, which allowed for the design, construction, and understanding of the importance of the proposed treatment system for quality of life.

Another differentiating aspect of this project compared to the consulted projects is the implementation of the constructivist educational proposal, emphasizing the importance of knowledge transfer as part of the integral processes carried out under the One Health framework. This differentiating factor engaged both the residents and the work team in solving real problems. The practical approach linked theoretical learning with experience, facilitating a better understanding of the issue and the proposed solution. Thus, the One Health framework not only aimed to address the immediate water need but also encouraged participants to engage in an educational process aimed at generating sustainable and replicable solutions that recognize the territory's characteristics and the impact of habitability on health. This should be considered a best practice compared to other projects that seek to improve water quality with efficient technical solutions but end up being imposed on communities, as they often do not explain the importance of the technology in quality of life, nor do they teach how to build or monitor it, viewing the project purely from a technical perspective, without considering the educational and public health aspects.

In relation to the consulted projects, the importance of having a research construct, such as public health, to raise participants' awareness through association processes, is one of the strengths of the One Health approach. When housing issues are linked to water and their impacts on residents' health, participants connect their reality with the significance of rainwater treatment technology for their quality of life, facilitating an understanding of water resource management and recognizing that the relationship between health and housing is essential. The lack of proper access to water increases residents' vulnerability to various diseases. Pathologies such as bronchitis, pneumonia, gastrointestinal infections, diarrhea, and cholera are related to poor access to potable water. Educating the community on these issues and providing tools to address them avoids paternalism, promoting structural change in the territory. This approach is one of the most valuable contributions of the One Health framework, as it allowed the community to participate in all stages of the project, providing the necessary knowledge to improve water quality, prevent diseases, and improve living conditions and hygiene in homes.

The proposal of an instructional design based on the integrative One Health approach demonstrates the work team's interest in helping the community truly understand the risk they face by living in environments that are making them sick due to the lack of water. The choice to work within a constructivist educational framework, based on participants' current reality and supported by the didactic strategies proposed in the course, is aimed at gradually changing their habits as they realize that water, habitability, housing, and health are intrinsically interconnected. A balance between these factors leads to an improvement in quality of life.

During the teamwork and educational proposal, it was confirmed that education is the key for participants to understand their reality and work to change it. A constructivist educational approach revealed that course attendees developed specific capacities, skills, and potential related to water resource issues, but also opened the possibility of building knowledge as a community, weaving collaborative ties that allowed the community to address its reality from new perspectives related to healthy environments and housing. The proposed educational model was conceived as a bridge between theory and practice, taking participants as active subjects and considering their behavioral patterns, values, social skills, and prior knowledge. In fact, the course aimed not for the student to memorize data but to develop their knowledge and capabilities in a group setting, acquiring the necessary understanding to meet the educational objective of forming individuals with awareness of water resource management and the various factors that compose it.

5. Conclusions

The teaching-learning model applied and aligned with the One Health approach fostered non-assistance-based processes at the community level. By directly involving beneficiaries in decision-making, design, and implementation of the project, a higher degree of ownership, interest, and participation was observed, in contrast to other projects where participants had pointed out their lack of inclusion. This participatory approach ensures that the proposed solutions are not only more relevant but also more sustainable in the long term.

The proposal of an instructional design based on the integrative One Health approach reflects the team's interest in ensuring that the community truly understands the risk they face by living in environments that are making them sick due to the lack of water resources. Therefore, the decision was made to work within a constructivist education framework, where, based on the participant's current reality and supported by the teaching strategies proposed in the course, a gradual change in habits is expected as they understand that water, habitability, housing, and health are intrinsically interconnected, and a balance between these factors signifies an improvement in quality of life.

The rainwater quality improvement project yielded significant conclusions regarding the themes, variables, and scope that can be addressed from an academic perspective to improve habitability conditions in areas with spatial and functional deficiencies. This type of intervention directly contributes to the well-being of the inhabitants from a public health perspective. Through One Health, a model was consolidated that guides the planning and implementation of projects aimed at improving sanitation conditions in housing within informal contexts, thereby complementing the holistic and systemic vision proposed by the One Health approach, which aims to prevent diseases through an integrated understanding of living environments and their effects on living beings.

Addressing the issue of water availability and quality for human consumption from a habitability perspective in urban and informal housing environments, using the "One Health" approach and supported by the AS method, provided both students and the community with a collaborative workspace. This approach integrated academic learning with social commitment and public health promotion, encouraging a fluid and respectful dialogue that allowed for the exchange of both codified and tacit knowledge between students and community members. As a result, not only was the water issue addressed, but other problems affecting the quality of life of the inhabitants were also identified, providing a broader perspective on well-being and public health in these contexts.

It is crucial for projects based on the One Health approach, which address issues from multiple disciplines and generate strategic alliances, to receive the necessary support from institutions. These projects should be viewed as opportunities for communities to adopt decentralized solutions that improve living conditions in informal settlements. In doing so, they ensure that the health of living beings is treated as the central focus, rather than as an externality, in the technical, social, and educational processes aimed at territorial development. Therefore, educating populations about the health risks they face is essential. Only by doing so can a community be motivated to care about its quality of life. The relationship between health and disease highlights the importance of training individuals who can truly grasp the dangers of living in a home or environment that threatens their well-being and that of their family. Equipped with this understanding, they can develop a participatory educational proposal.

Regarding the limitations of the One Health approach, as it is an integrative method, coordinating the involvement of all those from different disciplines in the territory was time-consuming due to the time constraints of the technical team members. Additionally, traveling to the project's epicenter presented difficulties regarding access and public transport coverage, requiring the use of private transportation. On the other hand, the approach does not always provide clear metrics for evaluating the impact in terms of water management or community education. Therefore, it is necessary for the second phase of the work to address this gap.

Regarding future theoretical developments related to the project, it is essential to explore how constructivist education can integrate knowledge about human, animal, and environmental health, promoting sustainable behaviors in water management. Moreover, it is important to analyze how rainwater management can reduce zoonotic diseases by improving interactions between humans, animals, and the environment. Furthermore, developing models that explain how communities can actively participate in the monitoring and maintenance of rainwater treatment systems, linking them to public health indicators, and proposing a social entrepreneurship model that contributes sustainability to the project, ensuring it does not depend on external international cooperation resources for implementation in the homes in the territory lacking water for human consumption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., J.J.C.P., and A.A.T. Methodology, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., M.G.M., and N.V.F. Software, C.A.T.P., J.J.C.P., and A.A.T. Validation, C.A.T.P., J.J.C.P., C.J.M., and N.V.F. Formal analysis, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., J.J.C.P., C.J.M., and M.G.M. Investigation, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., and M.G.M. Resources, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., J.J.C.P., M.G.M., A.A.T., and N.V.F. Data curation, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., C.J.M., A.A.T., and N.V.F. Writing—original draft preparation, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., and J.J.C.P. Writing—review and editing, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., J.J.C.P., C.J.M., M.G.M., and N.V.F. Visualization, C.A.T.P., and A.A.T. Supervision, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., J.J.C.P., C.J.M., M.G.M., A.A.T., and N.V.F. Project administration, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., and A.A.T. Funding acquisition, C.A.T.P., Y.N.S.M., J.J.C.P., A.A.T., and N.V.F All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The resources for the development of the research come from the call for proposals from the Catholic University of Colombia, grant number: 00000000760. The research units are: Catholic University of Colombia - UCC, Group: Infrastructure and sustainable development (Colombia) and Group: Sustainable habitat, integrative design and complexity (Colombia); Pontificia Universidad Javeriana - PUJ, Group: Ecology and Territory (Colombia); Jorge Tadeo Lozano University of Bogotá - UTadeo, Group: Communication - Culture - Mediation (Colombia); and Federal University of Latin American Integration - UNILA, Group: Mobility and energy matrix (Brazil).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all the staff of Altos del Cabo by Fondacio and its three French volunteers. To the community leaders and the community of San Luis, San Isidro Patios. To the 4 students from the Catholic University of Louvain: Arthur Hamoir, Stephanei Tamraz, Adrien Léonard and Norah Habets. To the staff of the community infrastructure area of the TECHO-Colombia organization for their support in the training workshops. To the 3 architecture students from the Catholic University of Colombia who provided images of the project to complement the information in this article: Lina Marcela Ramírez León, Melissa María Rubiano Cortes and Leidy Daniela Tacuma Cañón. To the members of the SIGESCO research groups and the Social Design Workshop of the Catholic University of Colombia; as well as to the members of the CinemaLab group of the Jorge Tadeo Lozano University of Bogotá. To Mauricio Facundo for his support in building the filter and to UTadeo professor Octavio Rodríguez for his audiovisual support in the various activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura, O.; de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente, P.; de la Salud, O.M.; de Sanidad Animal, O.M.; de acción conjunto, P. Una sola salud” (2022–2026). Roma: FAO; WHO; World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (founded as OIE); UNEP: 2024. [CrossRef]

- Signor, R.S.; Ashbolt, N.J. Comparing probabilistic microbial risk assessments for drinking water against daily rather than annualised infection probability targets. J Water Health 2009, 7, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Tobón, S.; Agudelo-Cadavid, R.M.; Gutiérrez-Builes, L.A. Patógenos e indicadores microbiológicos de calidad del agua para consumo humano. Rev. Fac. Nac. De Salud Pública 2017, 35, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO). CAPTACIÓN Y ALMACENAMIENTO DE AGUA DE LLUVIA. Opciones técnicas para la agricultura familiar en América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago, 2013.

- Montañoz, N.A. Evaluación de alternativas tecnológicas para el tratamiento básico del agua lluvia de uso doméstico en el consejo comunitario de la comunidad negra de los lagos, Buenaventura. Sci. Tech. 2016, 21, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, I.; Carmona, G.; Bojalil, J. MANUAL DE CAPTACIÓN DE AGUAS DE LLUVIA PARA CENTROS URBANOS. 2008.

- Rojas-Valencia, M.N.; Gallardo-Bolaños, J.R.; Martínez-Coto, A. Implementación Y Caracterización DE UN sistema de captación y aprovechamiento de agua de lluvia. Tip Rev. Espec. En Cienc. Químico-Biológicas 2012, 15, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- López, Y.L.; González, C.; Gallego, B.N.; Moreno, A.L. Rectoría de la vigilancia en salud pública en el sistema de seguridad social en salud de Colombia: Estudio de casos. Biomédica 2009, 29, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.-N.; Molina-Marín, G. Rectoría y gobernanza en salud pública en el contexto del sistema de salud colombiano, 2012–2013. Rev. De Salud Pública 2013, 15, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez, L.C.; Quintero, J.; García-Betancourt, T.; González-Uribe, C.; Fuentes-Vallejo, M. Funcionamiento de las políticas gubernamentales para la prevención y el control del dengue: El caso de Arauca y Armenia en Colombia. Biomédica 2015, 35, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán B, B.L.; Nava T, G.; Bevilacqua, P.D. Vigilancia de la calidad del agua para consumo humano en Colombia: Desafíos para la salud ambiental. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública 2016, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.M.; Spash, C.L.; Measham, T.G. Socio-economic and psychological predictors of domestic greywater and rainwater collection: Evidence from Australia. J. Hydrol. (Amst.) 2009, 379, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Motta, W.P. Sobre el derecho humano al agua. In Quórum. Revista de pensamiento iberoamericano; 2006; pp. 133–150. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=52001612.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, PLAN DECENAL DE SALUD PÚBLICA PDSP 2022—2031. El espíritu que actúa. Bogotá, 2022.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Indicadores básicos de salud 2023. Situación de salud en Colombia. Bogotá, 2023.

- de la Salud, O.P.; de la Salud, O.P.; McJunkin, F.E. Agua y salud humana. Serie PALTEX para ejecutores de programas 1988, 12. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/3099.

- de la Salud, O.P.; de la Salud, O.P. La agenda 2030 para el abastecimiento de agua, el saneamiento y la higiene en América Latina y el Caribe: Una mirada a partir de los derechos humanos. 2019. Available Online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51836.

- Figueroa, H.N.L.; Salazar, E.M.G. Prevalencia de enfermedades asociadas al uso de agua contaminada en el Valle del Mezquital. Entreciencias: Diálogos en la Sociedad del Conocimiento 2019, 7, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ubaque, C.A.; García-Ubaque, J.C.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J.P.; Pacheco-García, R.; García-Vaca, M.C. Limitaciones del IRCA como estimador de calidad del agua para consumo humano. Revista de Salud Pública 2018, 20, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobsey, M.D.; Water, H.T.W.H.O. Managing water in the home: Accelerated health gains from improved water supply/prepared by Mark D. Sobsey; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/67319.

- Yan, X.; Ward, S.; Butler, D.; Daly, B. Performance assessment and life cycle analysis of potable water production from harvested rainwater by a decentralized system. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 172, 2167–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.A.; DiGiano, F.A.; Sobsey, M.D. Virus attenuation by microbial mechanisms during the idle time of a household slow sand filter. Water Res. 2011, 45, 4092–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdiyev, K.; Azat, S.; Kuldeyev, E.; Ybyraiymkul, D.; Kabdrakhmanova, S.; Berndtsson, R.; Khalkhabai, B.; Kabdrakhmanova, A.; Sultakhan, S. Review of Slow Sand Filtration for Raw Water Treatment with Potential Application in Less-Developed Countries. Water 2023, 15, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagwuike, I.M.; Chibundo, N.P. Design and development of ceramic candle filter from ohiya clay. Sci. Res. J. 2021, 9, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glade, S.; Ray, I. Safe drinking water for small low-income communities: The long road from violation to remediation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]