1. Introduction

Energy Efficiency (EE) investments are central to advancing energy transition, abating greenhouse gases emissions, and fostering sustainability. Improvement in energy use in buildings and industry can lead to significant reduction in energy consumption and general costs, contributing, then, to decarbonization efforts. However, despite their potential, EE investments remain limited due to financial barriers, lack of awareness, and limited access to appropriate financing mechanisms

Among the possibilities of EE funding, one is Energy Performance Contracting (EPC). EPC is a method to implement structural improvements and upgrades in buildings through financing that is repaid using the savings generated from the improvements themselves. This approach allows energy upgrades to be carried out without requiring the initial financing costs to be borne by home, apartment, or building owners [

1,

2]. As an ally in the energy transition, the fight against greenhouse gas emissions and electricity saving, this model is currently popular in the public sector (intracting) but faces challenges in expanding to the private market [

2,

3,

4]. Barriers include insufficient information available to Energy Service Companies (ESCOs) about potential projects and skepticism regarding the ease of gaining benefits without upfront investment from property owners [

4]. Legal bureaucratic barriers and the ESCOs’ inability to control user behavior regarding energy efficiency further limit acceptance of the model [

4].

The most common contracting models for EPCs are guaranteed savings and shared savings. The primary difference between these two models is the payment structure for the ESCO and which party assumes the credit risk. In the guaranteed savings EPC structure, the customer finances the project and therefore assumes the credit risk. The ESCO guarantees a predetermined level of energy savings, which provides an income stream in the form of avoided costs to repay the project investment. In the EPC shared savings structure, the project is fully financed by the ESCO and the cost savings are shared between the customer and the ESCO for a predetermined period of time [

5]. EPC or ESPC are very useful financial models for energy contracting because they connect interested customers with ESCOs that have the technical expertise to implement EE or RE projects [

6]. An EPC or ESPC also provides a favorable cost structure for clients, as they repay project costs based on energy savings/profits rather than large initial investment burdens, which is typically a major barrier [

4,

6].

Regardless of the simple principle behind energy contracting, the uptake of EE retrofit projects, particularly in the building sector, has been slow [

7,

8]. Access to capital is a primary barrier for many interested buildings or facility owner. An EE project may require a large up-front investment to cover equipment, renovations, technology, expertise, labor, and other factors [

9,

10]. Many stakeholders interested in undertaking an EE project lack the capital to support a large-scale project. This may discourage many individuals from committing to an EE project because they cannot or will not take on the risk of debt [

11,

12]. Instead, they may cherry-pick a few short-term measures that result in small EE improvements instead of larger projects that have the potential to significantly reduce their energy demand [

6,

13]. An ESCO can help overcome this barrier by providing financing for the project, but they also have limitations. Only large ESCOs can financially support multiple projects simultaneously. Smaller ESCOs, on the other hand, must be more selective about the projects they take on because they do not have the capital backing of a larger company to continually launch projects. As a result, EE projects are often hampered by financing issues, even though their business case would be profitable. Against this background, the EPC and ESPC sector is in need of innovative financing solutions [

6,

11].

On the other hand, there are barriers that prevent users from using it. One of the most important barriers is a lack of awareness or information. Because the energy contracting and ESCO industries are still developing, many people, such as building owners, bankers, or lawyers, are not familiar with energy performance contracting and its financing method [

4,

14]. Therefore, it is not easy to convince clients to undertake a project as it is a foreign concept, and they may be reluctant to proceed. Also, the intuitions that support the project or the procurement process may not have the necessary information or awareness [

15]. This circumstance greatly hinders project development. If parties are not properly informed about the EPC, or if access to information is associated with high barriers to entry due to the complexity of the topic, it creates unclear processes for all stakeholders. As a result, EPC models have a diminished potential to be used in practice, despite the unique idea for the ongoing decarbonization trend. Complex legal and contractual issues are another barrier that needs to be addressed to increase the uptake of EPCs, as the legal documentation for EPCs is complex and novel The ESCO and potential customers often struggle to navigate the contractual landscape with its associated obligations, benefits and risks. In addition, the lack of standardization of the energy performance process adds to the legal uncertainty [

15].

The engagement, or lack thereof, of consumers in the energy transition is also significantly influenced by their perceived "ownership" of emerging energy systems. This ownership extends beyond legal definitions to include societal responsibility, behavioral change, and equitable distribution of benefits and burdens. Despite these broader implications, active participation in energy efficiency, prosumership, and energy system governance remains limited to a minority of financially capable early adopters and environmental activists [

16,

17]. Most citizens are excluded from these activities, highlighting the need for inclusive strategies that facilitate broader engagement.

An examination of green investment opportunities highlights the disparity in participation. Only a few can afford to invest in photovoltaic systems for their roofs, while tenants who cannot modify their rented properties face even greater challenges [

18]. This results in a renovation rate in Germany that is significantly lower than its potential [

6,

19,

20]. The commercial sector, despite the potential for high energy ROI, struggles with external financing constraints and limited resources for design and procurement [

6,

20,

21]. Energy Service Companies (ESCOs) and Energy Performance Contracting Companies (EPCos) play a critical role in bridging this gap by providing expertise in design, implementation, and financing. However, these entities require a high ROI to cover the risks, adding another layer of complexity.

Digital platforms through fintech initiatives could be viewed as an alternative to facilitate investment in energy efficiency measures. The new fintech solutions, including mobile payments, blockchain, and crowdfunding, reduce the costs of financial service delivery and improve access, especially to underserved areas, since fintech investments have shown to improve environmental efficiency and promote sustainable development goals [

22]. Digital platforms afford unique opportunities to surmount the barriers present in traditional investment methods, such as access to capital and long decision-making processes, by lowering costs of delivering financial services and expanding their accessibility [

23]. In addition, the introduction of ECF platforms further illustrates how disruptive technologies with social and environmental value propositions can attract investors to support sustainable initiatives [

24]. Their digital nature, added to the focus on sustainability and innovation, is expected to drive significant differences in how investments are made compared to traditional financial mechanisms, fostering quicker adoption and greater inclusiveness in EE measures.

The FinSESCo - Fintech Platform Solution for Sustainable Energy System Intracting and Contracting, funded by the Era-Net 2020 joint call, aims to address these issues by streamlining investment processes, reducing transaction costs, and leveraging economies of scale to expand the pool of profitable investments. The mission of the project is to enable a wave of decarbonization projects by facilitating the establishment of Energy Performance and Energy Savings Performance Contracting EPCo/ESPCo through the end-to-end digitization of energy contracting (and the contracting process for public entities and larger companies) and enabling EE projects to take into place by crowdfunding investment. Using pre-existing data from building passports and energy audits, platform modules offer a gamified investment process with diversification options in an investor dashboard, smart contracts, a digitally encrypted meter-based repayment process, and machine learning-based fault detection during operation. A guidance tool allows potential portal developers to steer their projects in the right direction.

Potentially, the fintech environment will be able to reach a larger number of investors, democratizing and diversifying the field of energy efficiency and overcoming the above-mentioned barriers. The research therefore aims to outline a profile of key stakeholders interested in the platform, identify gaps in investment and interest, and link overlooked groups to the use of the platform, as we expect that the digital environment of investments can significantly change the profile of EE investments.

Considering only the research for traditional EE investment, we see a complex interplay between a variety of motivational drivers, what we call in this paper controllers and socioeconomic factors, that seem to present a vast possibility of combinations that influence energy efficiency investments and behavioral changes. Previous research shows that investment in EE appliances, as well as the willingness to change behavior, is associated with environmental behaviors and the motivation to limit individual environmental impact [

25,

26,

27,

28], although it can be constrained by costs. That is, low-cost investments are more strongly associated with environmental consciousness, while high-cost investments are not primarily driven by it [

29]. Knowledge about the methods also positively influences and serves as a driver for investment [

30]. In some contexts, however, financial considerations appear to be the major factor leading to EE spending [

31]. This driver also varies according to the income group an individual belongs to, as financial savings do not act as the main motivator for high-income households but are a key factor for low-income ones [

30].

In what we call in this paper controllers may also redirect the willingness of investment in EE. There is a positive association between Renewable Energy (co-)Ownership and the willingness to invest in EE [

32] although it can vary depending on the type of prosumership (the ones that produce energy for self-consumption, just to sell excess and the fully fledged – the ones that do both) [

32]. Homeownership (combined with higher income) also seem to play a role in increasing the willingness to invest [

30,

33,

34]. Considering the equity crowdfunding functionality of the platform, we must consider what can lead to the investment. Past research shows that willingness to undertake crowdfunding investments in green energy is increased by past experiences utilizing the concept while moderated by the knowledge of environmental questions [

35]. Stronger markets where the concept of crowdfunding is more consolidated, and therefore more spread in the society increasing the possibility of users have past experiences, also increase the willingness to support projects [

36,

37]. At the same time, past EE investment can boost the willingness of future EE investments [

38], showing that knowledge of different EE investment models can lead to a cycle of what triggers more EE investment.

Regarding the socioeconomic profiles, previous research has shown that age plays a positive role in increasing the willingness to invest in energy efficiency measures [

34], with older and middle-aged individuals more likely to invest than younger ones. Gender does not appear to significantly influence energy efficiency investments [

33,

34], while education level may vary in its influence, sometimes affecting certain types of energy efficiency investments. The level and complexity of investments tend to increase with higher education levels [

33].

However, we assume that the order of importance and the interaction of these drivers, controllers and socioeconomic factors and their influence on the willingness to invest may shift or be differently impacted by the digital factor. Aiming to fill this research gap, compare both models and guide the FinSESCo consortium to understand the profile of investors of EE measures via fintech while compared to the ones in traditional environment, a survey with German households were conducted in 2023. The resulting dataset allows us to correlate interest in the platform, knowledge of energy efficiency contracting models, and previous experience with crowdfunding investments in energy efficiency behavior. We translated our interests into four main research questions, trying to predict which groups would be interested in using the platform by interacting with the different groups of variables (controllers and drivers), socioeconomic factors and the willingness to invest in EE and to invest in the FinSESCo platform:

What are the main drivers for investment in Energy Efficiency measures?

What are the main barriers for investment in Energy Efficiency measures?

Given the availability of options such as the FinSESCo platform, is it a determining factor for investing in Energy Efficiency?

Which groups are most likely to use the platform based on different socioeconomic demographics, real estate ownership, and experience in Renewables?

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces the material and methods underlying our analysis.

Section 3 presents the results of the analysis and

Section 4 delivers the corresponding discussion. Finally,

Section 5 concludes and considers the policy implications of our results.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the methods applied in this paper, discussing the process of data collection, the sample and the measurement, describing the models used.

2.1. Deliberations on the Data Collection

The data collection process is based on previous collections by Roth et al. [

32,

39] structuring the database with a focus on measuring the energy efficiency behavior and demand-side flexibility of renewable energy prosumers. The questionnaire was designed to enhance the existing database, this time targeting a broader range of prosumers and ensuring a better distribution of gender and income ranges, reaching a larger number of low-income prosumers and non-prosumers, as well as female prosumers.

It was conducted by the survey company Norstat between 28th of August 2023 and 23rd of November 2023, utilizing its pool of respondents and filters established by its team to target prosumers within it. Thus, the questionnaire may not be representative of the demographics of German prosumers – how they are distributed across different societal strata, the main sectors they represent, or infer the percentage of prosumers in the country - data still unknown [

40]. The questionnaire initially aimed to be representative of German society, aligning with the distributions in relation to the population of the states, age groups, and gender. Small adjustments were made during the data collection, with invitations sent to groups where a higher concentration of prosumers was observed without the use of filters. In the final phase of the collection, to achieve the expected numbers, internal questionnaire filters were used to exclude non-prosumers, and at the last moment, all those who were not female prosumers were excluded.

The data was collected to address the interests of FinSESCo, aiming to outline a profile of the main stakeholders interested in the platform, identify investment and interest gaps, and match overlooked groups with the platform’s usage. Possible relationships between potential platform usage and prosumership were translated into questions on the platform to utilize the data as broadly as possible. The data allows for the correlation of interest in the platform, knowledge of energy efficiency contracting models, and past experiences in crowdfunding investing in energy efficiency behavior, enabling a series of possible analyses for consumption habits to be tested.

1

2.2. Deliberation on the Sample

The total sample of the database consists of 2585 complete questionnaires. We have selected the main demographic and control variables for prosumership to briefly summarize the data characteristics. It is important to note that our database includes a high number of prosumers - a total of 925, with 464 of them being females. This is a robust database for understanding prosumer behavior, comparing it with non-prosumers, and conducting internal comparisons between genders and types of prosumership.

Our database initially aimed to be representative of the German demographic. Therefore, we sought to mirror the distribution by age groups according to the country data. However, as we tried to boost the number (co-)owners of the data, the invitations for the questionnaire focused on groups with a higher likelihood of encountering prosumers. Therefore, the data cannot be used to infer the number of prosumers in Germany.

To ensure the quality of the dataset, we conducted outliers test, t-test, and Wilcoxon test to examine differences in the samples of regular respondents and those who completed the survey after an interruption; syntax analysis searching for unusual values and characters. Additionally, we investigated the cooperation required to respond properly to matrix questions and the estimated time to complete the questionnaire. From the 2585 initial sample, we removed 31 questionnaires due to potential issues regarding their quality.

Income levels are defined based on thresholds derived from the median income. Specifically, incomes below 60% of the median are classified as low, those between 60% and 150% of the median as medium, and incomes above 150% of the median as high, using the main thresholds used for countries in the European Union [

41]

2.3. Deliberation on the Measurement

In our questionnaire, we have designed specific questions to understand the level of understanding of German households about energy efficiency contracting, their willingness to invest in models like FinSESCo and their willingness to invest in energy efficiency in general.

To calculate their willingness to invest in EE measures, we have asked if they have already invested in energy efficiency measures to reduce electricity consumption or investment in measures to reduce requirements for heating. The respondents could also select which types of investments they have made:

v_33_1: Replacing lighting with energy-efficient LED lamps

v_33_2: Replacing household appliances

v_33_3: Replacement of other electronic entertainment devices

v_33_4: Other

v_39_1: Replacement of windows

v_39_2: Renovation of the insulation of the house

v_39_3: Technical devices for heating management purchased

v_39_4: Replacing the circulation pump

v_39_5: Installation of a heat pump

v_39_6: Other

They were also asked if they are planning on performing these measures:

v_36_1: Replacing lighting with energy-efficient LED lamps

v_36_2: Replacing household appliances

v_36_3 Replacement of other electronic entertainment devices

v_36_4: Other

v_44_3: Technical devices for heating management purchased

v_44_4: Replacing the circulation pump

v_44_5: Installation of a heat pump

v_44_6: Other

For each question, the respondent could opt for 0 – no, or 1 – yes, meaning that they that they had invested or are planning to invest for each specific measure. Afterwards, after being briefly introduced to the models and how the platform will work, we asked the following questions:

v_63_1: Are you familiar with “Energy Savings Performance Contracting” or “Energy Savings Contracting”?

v_64_1: Would you use an Energy Savings Performance Contracting Service via FinSESCo?

v_65_1: Have you ever used crowdfunding to fund your own project?

v_66_1: Have you ever invested money through crowdfunding to finance a third-party project?

Afterward, respondents were asked to rate on a scale from -3 to +3, representing "Not familiar at all" to "Very familiar" for the first question, and "I wouldn’t use it under any circumstances" to "I would definitely use it" for the second. We transformed the scale from -3 to 0 as 0, meaning individuals who were not familiar and/or "people who would not use the FinSESCo model", and from +1 to +3 as individuals who were familiar and would use the FinSESCo platform.

Respondents were are also asked what were their main drivers to invest or plan to invest in EE measures:

v_40_1: Financial motivation

v_40_2: Environmental protection motivation

v_40_3: Previous knowledge motivation

v_40_4: Climate change motivation

v_40_5: Energy autonomy motivation

v_40_6: To sell excess energy motivation

For each answer, respondents could opt on a Likert scale from 1 - strongly disagree up to 5 – strongly disagree.

2 2.4. Deliberations on the Model Specification

Our analysis is based on backward stepwise regressions. Backward stepwise regression is a statistical method used for building regression models. In this approach, all independent variables are initially included in the model, and then, step by step, variables are removed based on their statistical significance until only the most significant variables remain [

42]. The backward stepwise regression starts with a full model containing all independent variables and gradually removes variables that contribute the least to the model’s predictive power [

43,

44]. This process continues until no further variables can be removed without significantly affecting the model’s fit. Overall, backward stepwise regression is a valuable tool for identifying the most influential variables and building a predictive [

45] model that accurately captures the relationship between independent and dependent variables in our analysis. In our analysis, the significance level of

is < 0.05, as per [

45] and [

46].

For this, we have created four different models. The models have as independent variables either an index to calculate the willingness to invest in EE measures using the FinSESCo platform (index_finsesco) or the willingness to invest in EE measures in general (index_ee).

The "index_finsesco" quantifies the willingness of respondents to use the FinSESCo platform, converting responses to the question "Are you familiar with ’Energy Savings Performance Contracting’ or ’Energy Savings Contracting’?" (v_63_1) from a scale of -3 to +3, representing "Not familiar at all" to "Very familiar" for the first question, and "I wouldn’t use it under any circumstances" to "I would definitely use it" for the second. a. The value of the variable v_63_1, here named y1, contains values on scale of 1 to 6; b. subsequently, we perform a log transformation. Log transformation is used to normalize skewed data, reduce the impact of extreme values, and make the data more normally distributed [

47] as many behaviors and perceptions follow a skewed distribution, where a few individuals exhibit extreme behaviors or attitudes [

48], Log transformation helps in stabilizing the variance and making the data [

47]; c. to this value, we add a constant of 1. Adding a constant (in this case, 1) before applying log transformation is a common practice to handle zero or negative values, since the log of zero is undefined; adding a constant ensures that all values are positive and hence, their logarithms can be computed; d. we normalize the value by dividing it by the mean of the values. e. finally, we take the square root of the total. Normalizing by the mean value of the transformed variables helps in standardizing the scores and making them comparable. This step ensures that the index is not biased by the scale of the original variables and is interpreted on a common scale.

Considering

the as the variable

v_64_1, the value of

index_finsesco can be seen in the following operation:

Subsequently the

index_ee is calculated. Considering V the group of variables, V={v33,1,v33,2,…,v44,6}, with 18 variables in total, Xi is the sum of valid (non-NA) values for row i and variable j:

Then, a log transformation is applied to the sum of valid values for row i, adding 1 to avoid log of 0, with a square root transformation to the log-transformed sum:

Finally, the value is normalized by computing the average of the square root transformed values for all rows I, and dividing the square root value by the mean

:

The value for index_ee is then:

After creating the independent variables, we divide the independent variables into three groups: drivers, controllers and demographics. Following is the list of the variables used in the four models calculated in this analysis.

Table 1.

Variables of the models.

Table 1.

Variables of the models.

| Variable |

Description |

| |

Indexes: |

|

index willingness to invest in energy efficiency |

|

index willingness to invest via FinSESCo |

| |

Drivers: |

|

v_40_1: Financial motivation |

|

v_40_2: environmental protection motivation |

|

v_40_3: previous knowledge motivation |

|

v_40_4: climate change motivation |

|

v_40_5: energy autonomy motivation |

|

v_40_6: to sell excess energy motivation |

| |

Controllers: |

|

Home Ownership |

|

Previous experience in crowdfunding |

|

Previous knowledge in energy-efficiency contracting |

|

Prosumer |

| |

Demographics: |

|

Income: Low |

|

Income: Medium |

|

Income: High |

|

Age |

|

Gender |

|

Education |

In our analysis, we employed bootstrapping to enhance the robustness and reliability of our regression models’ coefficients [

49]. Bootstrapping involves repeatedly resampling the original dataset with replacement and estimating the model on each resampled dataset. This process mitigates the influence of outliers, providing more accurate confidence intervals [

50,

51]. Specifically, the data was resampled 10,000 times to ensure a comprehensive and reliable estimation of the model parameters, where each sample had the same size as the original dataset.

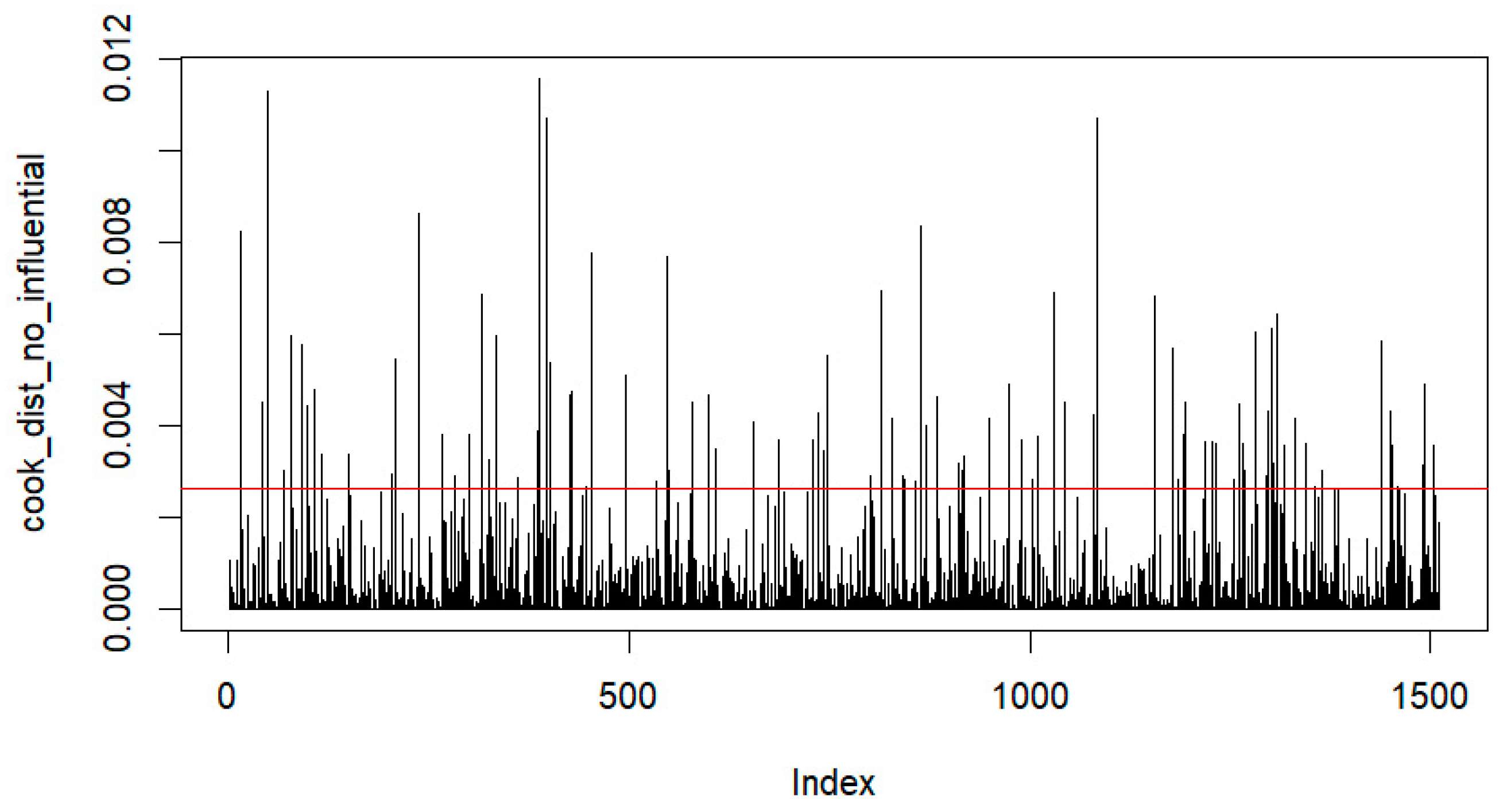

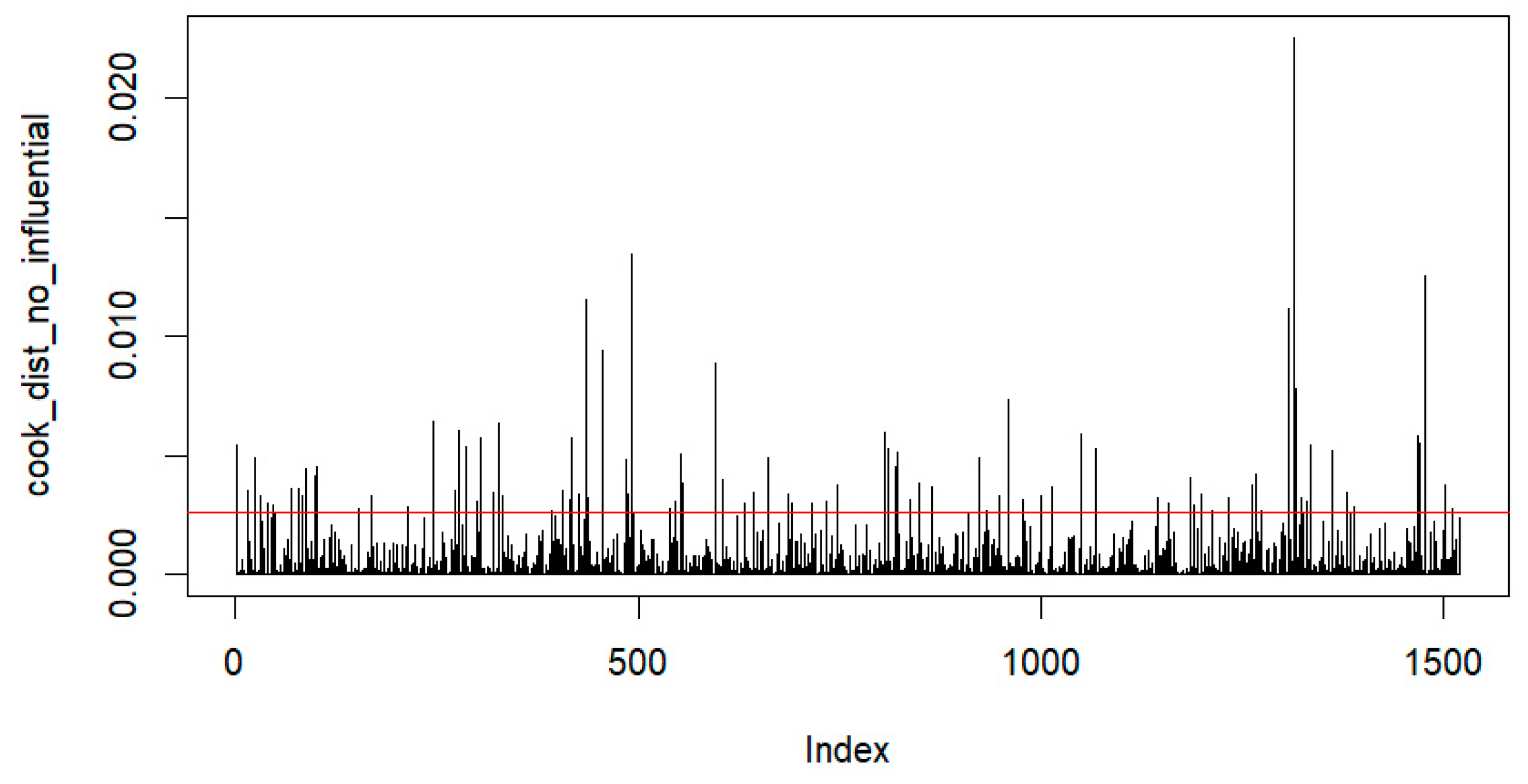

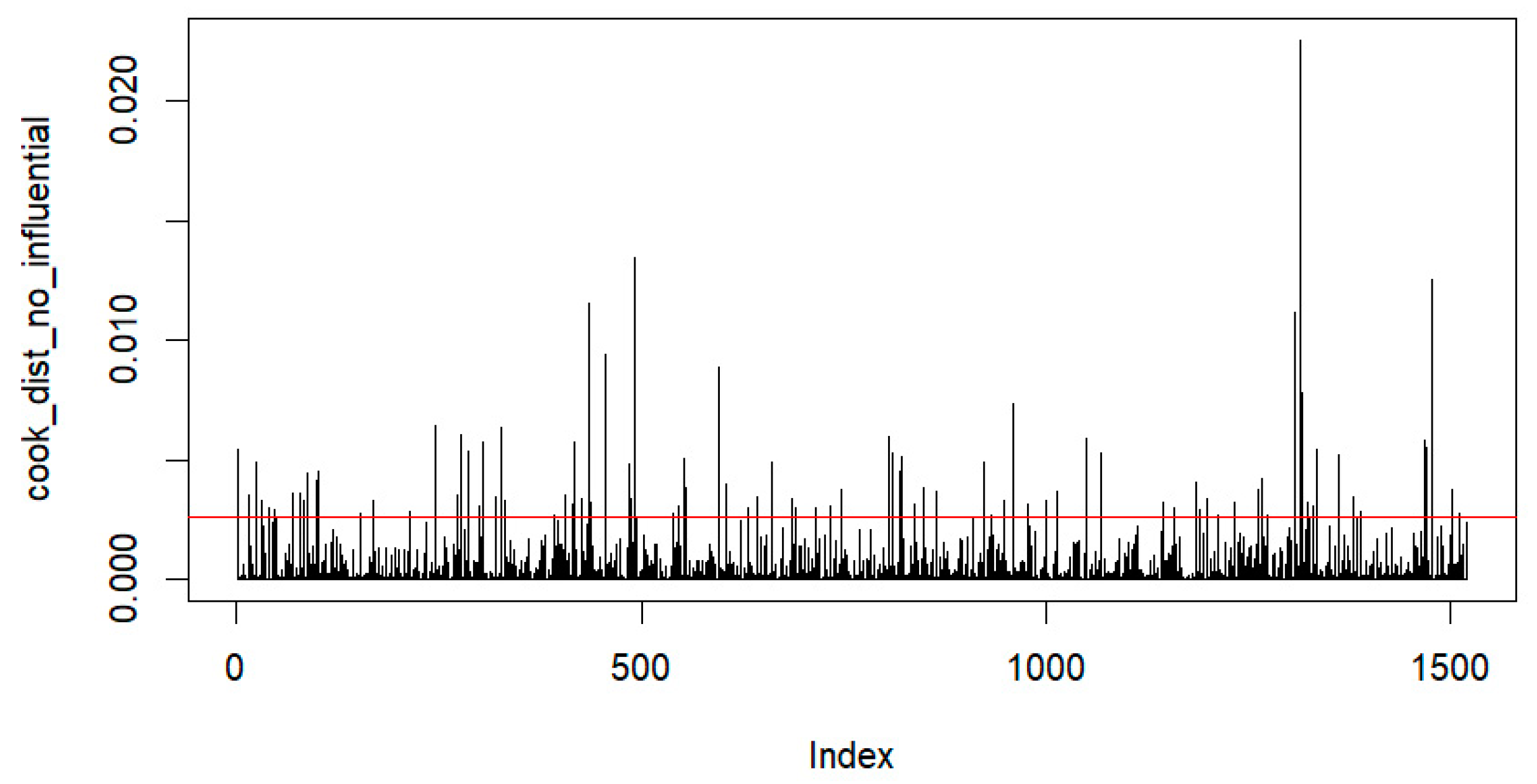

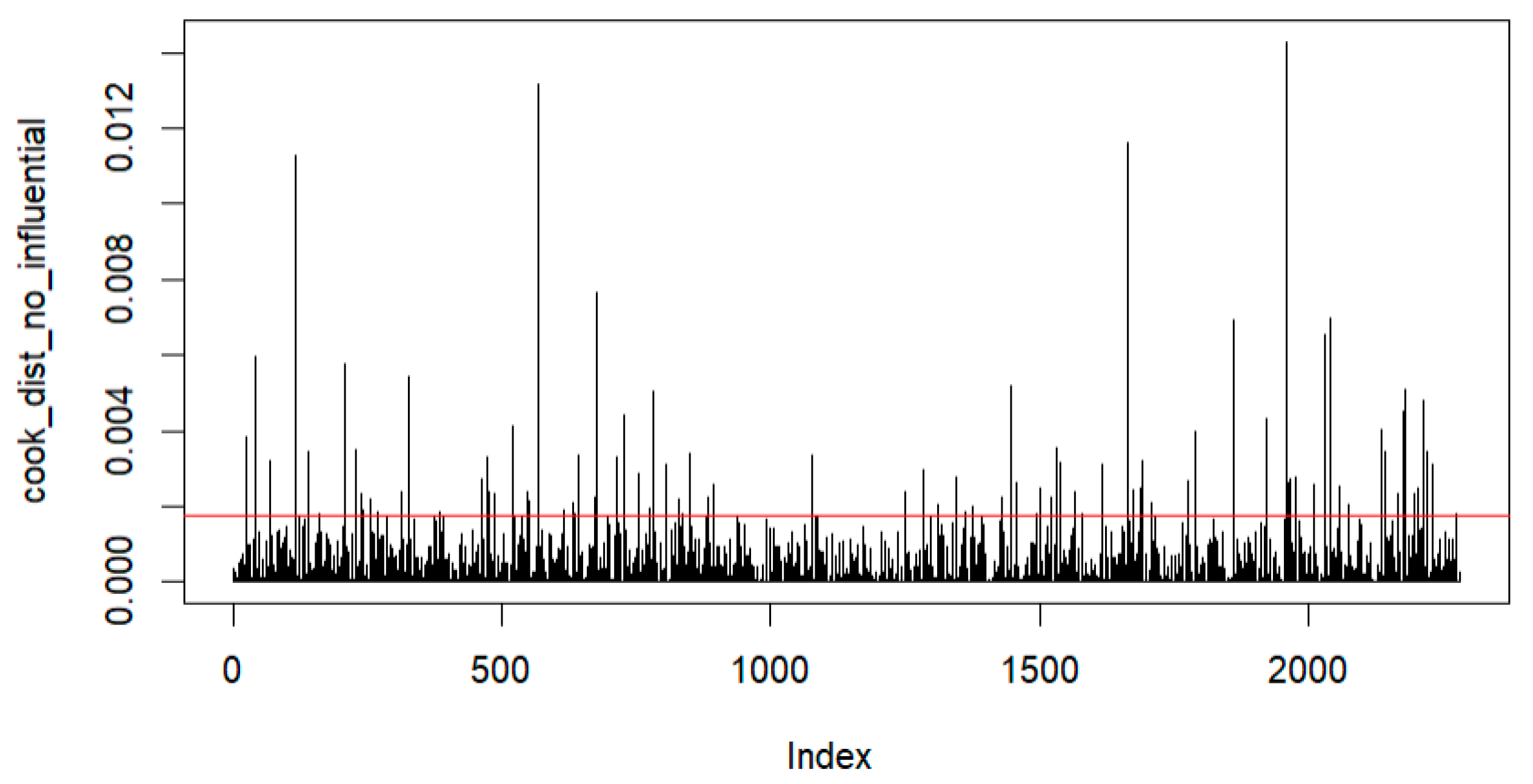

We then calculated the Cook’s Distance to identify influential points in the dataset [

52] and remove the ones exceeding 4/n, where n is the number of observations. A new regression model was fitted to the dataset without the influential points, again, performing a backward stepwise regression

3.

To answer our research questions, we created four different regression models: i) considering as the independent variable the index to calculate the willingness to invest in EE and the interactions of the drivers and the demographic variables; ii) the index to calculate the willingness to invest in EE and the interactions of the controllers and the demographic variables; iii) considering as the independent variable the index to calculate the willingness to invest via FinSESCo and the interactions of the drivers and the demographic variables; and iv) the willingness to invest via FinSESCo and the interactions of the controllers and the demographic variables. Following are the models.

For all models, coefficients are estimated using resampled datasets from 10,000 bootstrap iterations. Each model includes the interaction terms between demographic variables and either drivers or controllers, and accounts for the unexplained variance or error in the models. Each model is used to answer the four different research questions proposed after the analysis present in the previous section. All calculations were performed using RStudio with R version 4.4.0.

3. Results

The following paragraphs outline the results of the stepwise regression models that were developed to answer the research questions. The regression tables highlight the significance and impact of the most relevant predictors on the dependent variables. In a stepwise approach, only the most influential variables are kept, enhancing interpretability.

Table 2.

Interaction of Drivers and Demographics on the willingness to invest in EE.

Table 2.

Interaction of Drivers and Demographics on the willingness to invest in EE.

| term |

estimate |

std.error |

p.value |

|

| (Intercept) |

1.038972 |

0.06088 |

< 2e-16 |

* |

| Income: Low |

-0.08131 |

0.030025 |

0.006845 |

* |

| Income: Medium |

0.002593 |

0.0413 |

0.949952 |

|

| Income: High |

0.103556 |

0.04175 |

0.013233 |

* |

| Age |

0.001921 |

0.00099 |

0.052436 |

|

| Academic |

-0.03643 |

0.027474 |

0.185067 |

|

| v_40_2 |

0.029971 |

0.007847 |

0.000139 |

* |

| v_40_3 |

0.007181 |

0.004154 |

0.084071 |

|

| v_40_4 |

-0.01126 |

0.007328 |

0.1246 |

|

| v_40_5 |

0.051021 |

0.014993 |

0.000684 |

* |

| v_40_6 |

-0.02234 |

0.00717 |

0.001871 |

* |

| Income: Low:v_40_3 |

0.01879 |

0.009117 |

0.039489 |

* |

| Income: Medium:v_40_5 |

-0.02027 |

0.009041 |

0.02509 |

* |

| Income: Medium:v_40_6 |

0.028237 |

0.009232 |

0.002263 |

* |

| Income: High:v_40_4 |

0.024179 |

0.012454 |

0.052399 |

|

| Income: High:v_40_5 |

-0.01504 |

0.009223 |

0.103066 |

|

| Age:v_40_5 |

-0.00049 |

0.000272 |

0.071738 |

|

| Academic:v_40_6 |

0.015923 |

0.008699 |

0.067391 |

|

Residual standard error: 0.1712 on 1510 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.06525, Adjusted R-squared: 0.05906

F-statistic: 10.54 on 10 and 1510 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

For our model I, we see that environmental protection motivation (v_40_2) and the motivation to energy autonomous (v_40_5) as the main drivers to increase the willingness to invest in EE. The increase of the variable Age combined seems to play a positive effect, although on the border of being a statistically significant predictor. The low-income variable has a negative direction of the estimate, while the high-income one a positive, although the interaction of low-income with previous knowledge driver (v_40_3) results in a positive direction.

Table 3.

Interaction of Controllers and Demographics on the willingness to invest in EE.

Table 3.

Interaction of Controllers and Demographics on the willingness to invest in EE.

| Term |

estimate |

std.error |

p.value |

|

| (Intercept) |

1.235 |

0.02028 |

< 2e-16 |

* |

| Income: Low |

-0.04087 |

0.01309 |

0.001824 |

* |

| Income: High |

0.01623 |

0.0102 |

0.111989 |

|

| Age |

-0.000079 |

0.000381 |

0.836263 |

|

| Academic |

-0.003209 |

0.01036 |

0.756673 |

|

| Home-Ownership |

0.04979 |

0.00972 |

3.41e-07 |

* |

| Crowdfunding Experience |

0.03687 |

0.01116 |

0.000977 |

* |

| EPCo Experience |

-0.136 |

0.05655 |

0.01629 |

* |

| Income: Low: EPCo Knowledge |

0.1222 |

0.0422 |

0.003841 |

* |

| Age:EPCo Knowledge |

0.002372 |

0.00119 |

0.046356 |

* |

| Academic: EPCo Knowledge |

0.08161 |

0.02842 |

0.004142 |

* |

Residual standard error: 0.1712 on 1510 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.06525, Adjusted R-squared: 0.05906

F-statistic: 10.54 on 10 and 1510 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

In our model II, only low-income households appear to have a statistic significant coefficient to predict the willingness to invest in EE, playing a negative factor, although the interaction with familiarity with energy efficiency contracting inverts the direction. Previous experience with crowdfunding and especially home-ownership seems to statistically significant impact on the increase of index_ee Prior knowledge about energy efficiency contracting have a negative coefficient, however its interaction with academic (people with high education degree) and Age have both a positive effect.

Table 4.

Interaction of Drivers and Demographics on the willingness to invest using the FinSESCo platform.

Table 4.

Interaction of Drivers and Demographics on the willingness to invest using the FinSESCo platform.

| Term |

estimate |

std.error |

p.value |

|

| (Intercept) |

1.384391 |

0.108056 |

< 2e-16 |

* |

| Income: Low |

0.077879 |

0.100578 |

0.438824 |

|

| Income: Medium |

-0.07522 |

0.085317 |

0.378087 |

|

| Income: High |

-0.02557 |

0.082289 |

0.756056 |

|

| Gender |

0.169004 |

0.084368 |

0.045276 |

* |

| Age |

-0.00136 |

0.000811 |

0.09443 |

|

| Academic |

-0.09107 |

0.063354 |

0.150698 |

|

| v_40_1 |

-0.04571 |

0.011734 |

0.000101 |

* |

| v_40_3 |

0.003849 |

0.013521 |

0.775919 |

|

| v_40_4 |

0.026997 |

0.017248 |

0.117676 |

|

| v_40_5 |

-0.07627 |

0.013109 |

6.78e-09 |

* |

| v_40_6 |

-0.01456 |

0.016307 |

0.372144 |

|

| Income: Low:v_40_1 |

-0.03836 |

0.025142 |

0.127252 |

|

| Income: Medium:v_40_6 |

0.050084 |

0.026072 |

0.054855 |

|

| Income: High:v_40_5 |

0.054662 |

0.020287 |

0.007101 |

* |

| Gender:v_40_4 |

-0.05572 |

0.021245 |

0.008783 |

* |

| Academic:v_40_3 |

0.047107 |

0.02005 |

0.018885 |

* |

Residual standard error: 0.4988 on 2275 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.07522, Adjusted R-squared: 0.06871

F-statistic: 11.56 on 16 and 2275 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

In our model III, although not statistically significant, we see for the first time the low-income variable being associated with a positive effect in the dependent variable. The variable gender has a positive and statistically significant effect on the willingness to invest in EE via the FinSESCo platform. This index also increases with the interaction of the high-income variable and the driver for energy autonomy.

Table 5.

Interaction of Controllers and Demographics on the willingness to invest using the FinSESCo platform.

Table 5.

Interaction of Controllers and Demographics on the willingness to invest using the FinSESCo platform.

| Term |

estimate |

std.error |

p.value |

|

| (Intercept) |

4.127004 |

0.168481 |

< 2e-16 |

* |

| Income: Low |

0.292901 |

0.116232 |

0.01181 |

* |

| Income: Medium |

0.206155 |

0.095596 |

0.03115 |

* |

| Income: High |

0.37052 |

0.113093 |

0.00107 |

* |

| Gender |

-0.015558 |

0.06387 |

0.80758 |

|

| Age |

-0.01805 |

0.003026 |

2.83e-09 |

* |

| Academic |

0.119923 |

0.061975 |

0.05311 |

|

| Home-Ownership |

-0.248104 |

0.2126 |

0.24334 |

|

| Crowdfunding Experience |

0.133435 |

0.109454 |

0.22293 |

|

| Prosumership Experience |

0.207034 |

0.080738 |

0.0104 |

* |

| EPCo Knowledge |

0.866511 |

0.141527 |

1.08e-09 |

* |

| Income: Low: Home-Ownership |

-0.320667 |

0.164468 |

0.05133 |

|

| Income: High:Prosumership Experience |

-0.178546 |

0.125641 |

0.15543 |

|

| Gender: Crowdfunding Experience |

0.269898 |

0.146185 |

0.06498 |

|

| Gender: EPCo Knowledge |

-0.306526 |

0.190073 |

0.10695 |

|

| Age: Home-Ownership |

0.006661 |

0.004337 |

0.12477 |

|

Residual standard error: 1.322 on 2265 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.09531, Adjusted R-squared: 0.08932

F-statistic: 15.91 on 15 and 2265 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Finally, in our model IV, although the high-income variable play a positive effect in the willingness to invest in EE via the FinSESCo platform, the low-income variable seems to have a higher effect than the medium-income one. In this model, the increase in the age variable is associated with a negative effect on the dependent variable and its value is highly statistically significant, as is the previous knowledge of EPC, but this time, positively. Past experiences with prosumership also have a positive effect on the index finsesco.

5. Conclusion

This paper conducts an analysis of the most important engagement-determining factors in the Energy Efficiency investment platform FinSESCo, particularly demographic characteristics, previous experience with EEC, and Renewables co-ownership-related dynamics. The built and tested models shed light on diverse factors that shape interest in EE investment via a Fintech platform. The findings revealed a complex interplay among socioeconomic and demographic factors and household dynamics that influence attitudes toward energy efficiency investments. The positive associations between lower income levels and platform engagement do confirm that the FinSECCo model attracts a public that is economically heterogeneous, those looking for cost-efficient energy solutions. Gender dynamics and RE ownership continue to condition engagement, emphasizing the importance of inclusivity integrating these variables. The characteristics of the platform could potentially widen participation in energy-efficiency projects by attracting non-homeowners, particularly renters, who have shown interest on the platform, which could help wider involvement and overcome the traditionally strong barriers of financing. Among the most important factors is the strong relationship between experience with RE installations and a much higher likelihood of engagement within the platform. Surely, this suggests that those with the experience do realize the benefit attached to the reinvestment in renewable energy.

We identified several key differences and similarities between engagement with the FinSESCo platform and more traditional forms of energy efficiency investment. The FinSECo platform makes the market more accessible to lower-income groups and renters, mostly excluding from traditional energy-efficiency investments, lowering the barriers to participation. Regarding motivational drivers, a wider scope comes with this platform, appealing to people who seek positive environmental impact opposed to traditional investments with an individual financial focus, especially those in the medium- and high-income households.

Both models, however, attract those with experience or knowledge relating to energy efficiency investments. Familiarity with crowdfunding or renewable energy systems is one of the most critical drivers of engagement in both models. Financial savings are a key driver for both the platform and traditional methods, particularly among lower-income participants. The economic incentives to invest in energy efficiency are fairly well accepted across a wide demographic base. These findings underline the potential of the FinSESCo platform for increasing energy efficiency participation and filling in some of the gaps from traditional approaches that cannot easily reach economically or socially disadvantaged groups.

Finally, further research is needed to identify precisely which strategies will enhance initial engagement, and to consider the longer-term effects of knowledge and information in EE investment via fintech platforms. Our findings point out that the FinSESCo platform can be scaled up with great potential for investment in energy efficiency measures; still, it has to tackle the informational and motivational barriers by capitalizing on its strengths while navigating in the fintech sector. By fostering inclusivity and accessibility, the fintech environment can tackle traditional barriers associated with EE investment, creating a more inclusive and accessible scenario, hence driving wider participation in the transition toward energy efficiency.