1. Introduction

Humanizing the energy transition is increasingly considered a fundamental dimension for achieving the European Union’s (EU) ambitious objectives of carbon neutrality by 2050 [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Anchoring renewable energy technologies in society is essential to build trust, disseminate knowledge and foster their adoption [

5]. Simultaneously, managing the energy transition requires the adoption of new energy practices to optimize or reduce current consumption [

6,

7]. This evolving perspective has given rise to a new breed: energy citizens. According to this view, people equipped with the knowledge, motivation and agency to engage with energy in meaningful ways are willing to drive positive change in the energy sector transition [

8,

9,

10,

11].

In response to this evolving paradigm, energy communities have emerged as a powerful mechanism of collective action, closely linked to the concept of energy citizenship. These communities enable citizens to collectively own renewable energy projects, empowering them to exercise their sovereignty and actively engage in democratic processes of control and decision making [

5]. People engaged in energy communities are considered particularly inclined to assert their rights and fulfil their responsibilities concerning the energy transition and, more broadly, climate change [

8,

12]. Many (e.g. [

13]) see energy communities not only as contributing to the transition towards sustainable energy systems but also nurturing the development of active and empowered energy citizens.

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the current lack of empirical research comprehensively examining the engagement practices of energy community shareholders. Different forms of citizens’ involvement have already been observed, highlighting the need to recognize and understand the potential diversity within these organizations [

14].

Another critical aspect regarding the idea of energy citizens pertains to its inclusive potential [

17]. In this sense, according to some [

18,

19], energy communities can help overcome certain barriers that hinder the participation of specific social groups. However, so far, data suggest that in collective action initiatives, too, there is considerable homogeneity with regard to members’ gender and socioeconomic background [

20]. Often the conventional notion of energy citizenship carries behavioural expectations, which can present difficulties for some individuals, who may perceive it as restrictive rather than empowering. In particular, certain barriers related to energy literacy and socioeconomic characteristics risk undermining individuals’ participation and capacity to act as energy citizens [

21,

22]. Energy communities may be less appealing to those with the greatest needs and instead favour an elitist approach to energy democracy [

22,

23,

24].

Accordingly, this study aims to answer the following research questions:

In order to answer these questions, the paper is structured as follows. In the following section, we question the link between energy communities and energy citizenship (

Section 2), before explaining the methodology used to answer the research questions, i.e. a mixed-methods analysis combining a survey and qualitative interviews (Section 3). We then report (

Section 4) and discuss (

Section 5) the results, before concluding with some policy recommendations (Section 6).

2. Energy Communities and Energy Citizenship: Understanding the Nexus

Decentralized energy technologies offer the opportunity as well as the need for increased citizen engagement in the energy transition [

25,

26]. To underline this shift, the concept of energy citizenship has been increasingly used especially by EU institutions, as a core aspect of a new energy market model based on collectivist and participatory values [

27,

28].

Initially conceived by Devine-Wright [

8,

29], energy citizenship frames the

energy public as active, enthusiastic citizens, interested in new renewable technologies through their participation in collective action like energy communities. More recently, energy citizenship has been defined as

people’s rights (i.e. entitlement to energy services and participation opportunities in the energy transition) and responsibilities (i.e. commitment to promote and participate in the energy transition) for a fair, just and sustainable energy transition [

30]. In this context, energy citizenship encompasses both a public dimension, referring to active participation in collective actions, and a private dimension, involving the adoption of sustainable behaviours in daily life. These dimensions are closely intertwined with the concepts of empowerment, accessibility and inclusivity.

The former dimension, public engagement, stresses the role of energy communities in offering energy consumers an opportunity for active involvement through a deliberative democratic process [

31,

32,

33]. By engaging in energy communities, consumers are motivated to participate both politically and socially in the public arena of energy management. This active engagement allows individuals to exercise their rights and assume responsibilities as proactive participants and advocates for a sustainable transition [

30,

34,

35,

36].

Such emphasis on the public dimension of energy citizenship has since been extended with the inclusion of private consumption. In this sense, energy citizenship additionally includes a material perspective [

22,

37,

38]. Energy citizenship pertains not only to members’ public involvement in the community but also to engage members in modifying their daily practices. By promoting awareness and encouraging responsible behaviours at the personal level, energy citizenship fosters a holistic approach to sustainable energy practices [

39,

40]. In this regard, energy communities appear to provide a promising institutional context in which members develop interpersonal connections, moral norms and identification [

41,

42,

43]. Indeed, previous studies have found that the more people identify with their energy community, the more likely they are to have strong pro-environmental attitudes conforming to the expectations of their organization [

44,

45,

46].

Furthermore, we can add to these two dimensions of energy citizenship a third one related to empowerment processes. Wuebben et al. [

47] have underlined the potential of energy communities to act as capacity builders for their participants, who become more able not only to make their own decisions but also to change their behaviours, through training them on energy savings or efficiency [

48,

49]. Owing to this process of empowerment, energy communities can be considered highly conducive to the development of the concept of energy citizenship [

49,

50].

Finally, more recently, the concept of justice has also been integrated into the understanding of energy citizenship, adding a crucial dimension to its framework. De facto the literature on energy citizenship underscores the importance of social inclusion and the imperative to ensure universal access to energy resources [

48,

51]. Again, energy communities can be a way to ensure this objective, paying special attention to the fact that each citizen can fully take part in these initiatives independently of gender, socioeconomic or age inequalities [

52]. In this sense, energy communities can address energy citizenship’s socioeconomic barriers, by setting for example low entrance fees and trying to avoid power distortions among their shareholders [

53].

The nexus between energy communities and energy citizenship in relation to these four key dimensions – namely public engagement, private engagement, empowerment and justice – has mostly been taken for granted in the literature and, in particular, there is a lack of quantitative data critically investigating it. As will emerge in the following sections, the main objective of our research is thus to question this nexus, in its four dimensions, in order to offer a critical evaluation of the actual contribution of energy communities to fostering energy citizenship.

Methodology

3.1. The Case Studies

We chose to focus our research on energy cooperatives, these being among the most diffused forms of energy community in the EU. We selected two energy cooperatives: è nostra in Italy and Ecopower in Belgium. These are two of the most important energy communities in Europe belonging to the European Energy Cooperatives organization (REScoop.eu), which we chose because they have similar organizational structures and are the biggest organizations in their respective countries. È nostra is a national cooperative, even if most of its shareholders are based in Piedmont and Lombardy, while Ecopower operates across the whole territory of Flanders. However, they present contrasting levels of size and financial attractiveness, which may shape the concept of energy citizenship in different ways. È nostra was established in 2015 and Ecopower in 1991. In 2021, è nostra comprised 9,664 shareholders and Ecopower 64,000. Moreover, in 2021, è nostra produced only 14% of its own consumption, making it highly dependent on market prices [

54]. By contrast, Ecopower was able to provide energy for all its shareholders and was also the least expensive energy supplier in Flanders [

55].

3.2. Mixed-Methods Analysis

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the concept of energy citizenship and its inherent complexity, we employed a mixed-methods analysis, combining survey data with interviews. This approach served as an indispensable framework for examining various facets and dimensions of energy citizenship, helping us interpret our quantitative data by delving deeper into the nuances, contexts and subjective experiences surrounding the quantitative findings [

56].

As regards the quantitative data, we launched the survey at the beginning of 2021 and it remained available for one month on the European survey platform (

https://ec.europa.eu/eusurvey). We collected 5,402 responses, 288 of which came from è nostra and 5,114 from Ecopower concerning their current practices in their communities. Our sample comprised 22.14% females and 77.86% males. People with a university degree in a humanities field were best represented (50.37%), while people in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) made up 24.47% of the sample and those with a high school diploma or below represented 21.84%. People with an income above the national median represented the majority: 81.49%. As regards age, 35% were 50 or younger.

Concerning the qualitative data, we conducted 20 semi-structured interviews, which we then transcribed and coded using NVivo software (

Table A1 in

Appendix A). We interviewed 11 people in è nostra and nine in Ecopower, including both members and cooperative staff. For the members of the cooperative, the interview participants were recruited through snowballing via personal contacts. The first objective of the interviews was to deepen our understanding of how the shareholders perceived and related themselves to the concept of energy citizenship. The second objective was to understand how energy citizenship was being promoted by their energy communities and how far this strategy was working, through asking the shareholders whether they had sensed any changes regarding their current consumption practices since first participating in their energy communities. Finally, with the staff members of these organizations we tried to better understand their views on energy citizenship and the possible barriers they encounter to achieving greater awareness and equality in their organizations.

3.3. Operationalization of Variables

Our first objective was to determine whether citizens taking part in energy communities were characterized by a strong level of public engagement, such as active participation in collective action initiatives. We also sought to examine the extent of private engagement, specifically focusing on pro-environmental behaviours aligned with these initiatives.

To operationalize the level of public and private engagement, we first adopted a quantitative approach using the following questions to build two variables to assess whether a variety of forms of participation were emerging in both energy communities:

The first set of questions pertained to participation in the community, whereby the participants could choose between a set of propositions concerning the activities they were doing for their cooperative: (1) reading emails and/or the newsletter; (2) participating in meetings, information sessions, or events; (3) participating in general assemblies; (4) volunteering; (5) promoting the cooperative (e.g. distributing flyers, contacting potential new members); (6): taking on leadership activities; (0) no activity. The responses were then summed to build a scale ranging from 0 (no involvement) to 6 (strong involvement).

The dimension of private behaviours was measured using an index assessing the adoption of low-energy consumption and sustainable behaviours in general (nine items), e.g. (1) turning off electronic devices instead of putting them on standby; (2) sorting waste; (3) avoiding plastic bags; (4) using refillable water bottles instead of plastic bottles; (5) buying organic products; (6) walking or cycling short distances instead of using a car or motorcycle; (7) reusing and recycling products and materials; (8) purchasing products based on their environmental impact; (9) preferring bicycles or public transport over cars. These items were all evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never; 2 = almost never; 3 = sometimes; 4 = almost always; 5 = always). Given that they exhibited good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.71, they were gathered together as a unique new variable called ‘sustainable behaviours’.

For the analysis, we used Stata software. In this analysis, we adopted an explorative approach, considering information regarding two factors that we assumed were associated with energy citizenship: belonging to the cooperative (0 = Ecopower; 1 = è nostra) and shareholders’ instrumental motivations, measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important; 5 = very important). In parallel, we t conducted a cluster analysis, a promising tool to effectively read and interpret the data from a Likert scale [

57].In each cooperative two variables were considered, namely public and private engagement in order to question the shareholder’s diversity and identify groups across the cooperatives. Since our data set was fairly big, we considered the Ward method well suited for exploring and identifying meaningful patterns and common characteristics among members [

58,

59]. To determine the number of clusters, we used the Duda-Hart rules [

60].

Furthermore, we sought to explore any potential correlations between the clusters and the underlying concepts of empowerment and justice that, as noted above, are intrinsic to the notion of energy citizenship [

61,

62]. To this end, we used two other variables:

Empowerment: (1) ‘By being a member of the cooperative, I have been able to develop energy competencies. The items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 1 = disagree; 2 = neutral; 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree).

Justice and social inclusion: (1): ‘What is your gender?’, where respondents could select either ‘woman’ or ‘man’; (2) ‘What is your field of study?’, coded as either ‘No higher degree’, ‘Degree in STEM’ or ‘Degree in humanities’; (3) ‘What is your income?’, coded as either ‘Above the median’ or ‘Under the median’. These three questions were combined as a single variable, ‘Inclusivity’, by summing their values from 1 (strong diversity in members’ characteristics) to 5 (homogeneity in members’ characteristics).

For these two variables, we conducted descriptive statistics and a Kruskal–Wallis test, the equivalent of an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for the categorical variables to identify whether their variations were statistically significant across our clusters.

Finally, for the quantitative analysis, we integrated interview data that we had coded using NVivo according to the concepts identified previously: public and private engagement, empowerment and inclusivity. In this way, qualitative data allowed for a more comprehensive and insightful interpretation of the quantitative results, enabling us to capture a richer understanding of the research phenomenon under investigation.

4. Results

4.1. Cluster Analysis

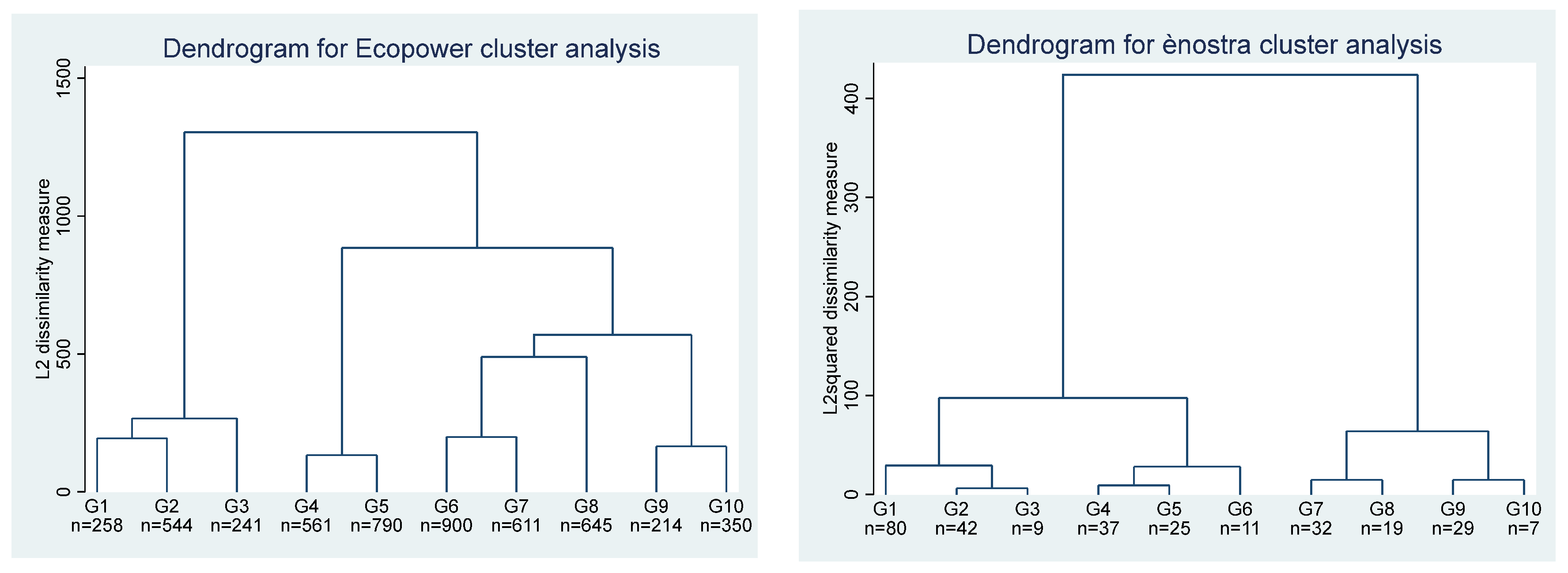

With regard to Ecopower, the analysis confirms the presence of diverse participation profiles within the cooperative (

Graph 1). The dendrogram reveals the existence of approximately five distinct member groups. The Duda-Hart criterion supports the notion that the optimal outcome is achieved with a five-cluster solution (

Table A2 in

Appendix A). Looking deeper into our results, we see that the shareholders of Ecopower differ significantly on both variables of public and private engagement, presenting diverse degrees of involvement as well as a variety of practices more or less oriented towards sustainability. However, the cluster analysis for è nostra yields contrasting findings on these two variables (

Graph 1). Both the dendrogram and Duda-Hart analysis (

Table A2 in

Appendix A) indicate that a three-cluster solution best fits our data for è nostra. These discrepancies between the cooperatives are primarily explained by the greater homogeneity of practices among è nostra members, which consequently reduces the diversity of patterns identified by the cluster analysis in this case.

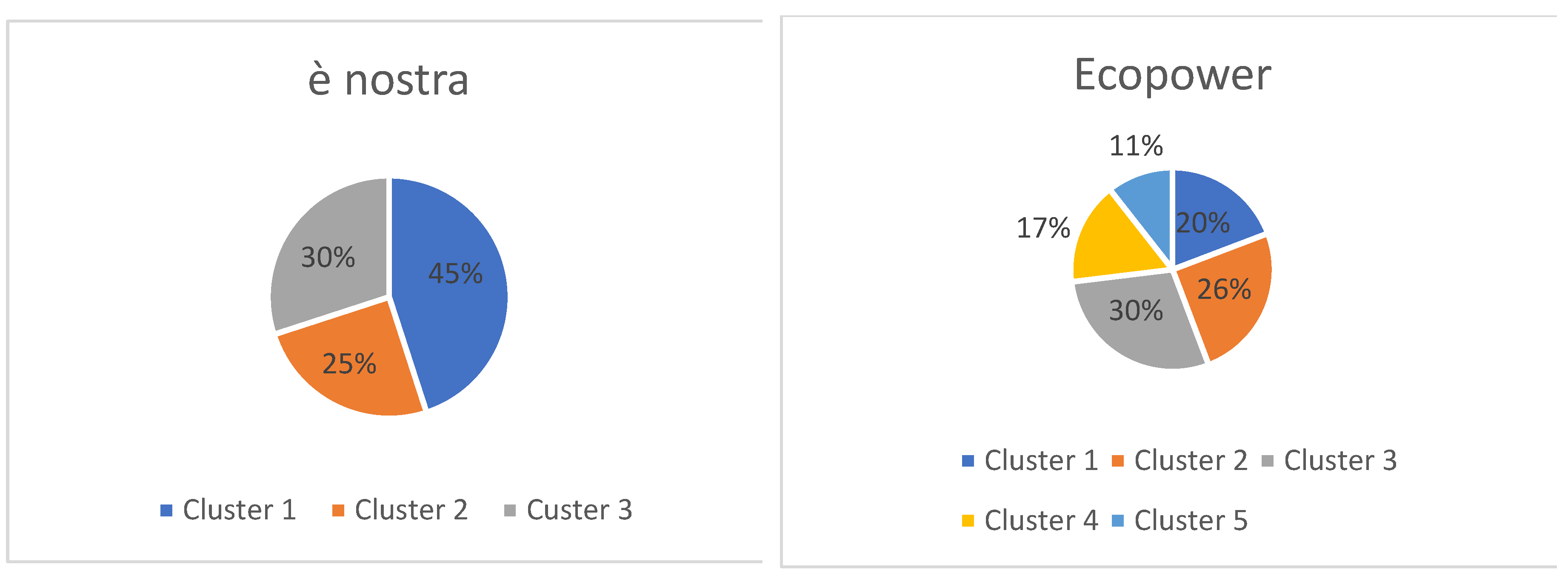

In terms of the distribution of cases across clusters, in è nostra, Cluster 1 emerges as the dominant group, representing 45% of the cases. The other two clusters have relatively similar sizes, with Cluster 2 accounting for 30% and Cluster 3 for 25% of the cases.

In Ecopower, however, the largest clusters are Clusters 3 and 2, comprising 30% and 26% of the cases, respectively. Cluster 1 represents 20% of the cases, while Cluster 4 accounts for 17% and the smallest cluster, Cluster 5, consists of 11%.

Graph 2.

Repartition of the cases across clusters.

Graph 2.

Repartition of the cases across clusters.

4.1.1. Public Engagement in the Cooperatives’ Activities

In general, our data show a low involvement in both cooperatives across members (

Table A2 in

Appendix A). However, still significant contrasts emerge between the two organizations. For example, reading emails is more prevalent among Belgian shareholders compared to their Italian counterparts, while in the case of è nostra 18% assist to the general assembly against 8% for Ecopower (

Table A2 in

Appendix A).Our quantitative data reveal also that individuals with higher financial motivations exhibit a slightly greater level of involvement in cooperative activities (

Table A3 in

Appendix A), going deeper with the cluster analysis, different patterns of public engagement emerge.

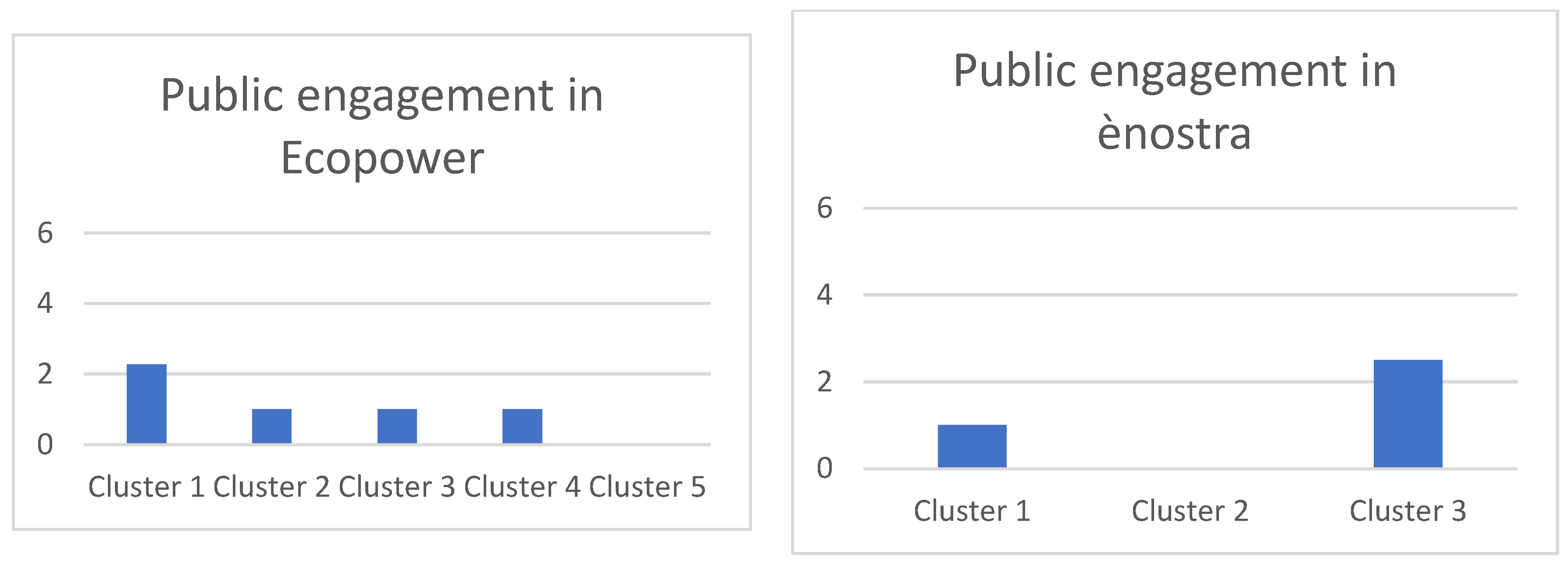

With the exception of Cluster 5 in Ecopower and Cluster 2 in è nostra, which show no involvement, there is generally a significant level of public participation among the shareholders in both cooperatives. However, it is noteworthy that for the Cluster 1 in è nostra and Clusters 2, 3 and 4 in Ecopower (

Graph 3), the members tend to be quite passive, with many shareholders primarily engaging by reading emails rather than actively involving themselves in their communities. To the contrary, Cluster 1 in Ecopower and Cluster 3 in è nostra exhibit higher levels of engagement than the other clusters. Their members actively participate in events such as general assemblies and take on roles in promoting their cooperatives. Nevertheless, with regard to activities that require more resources, such as volunteering, the percentage of shareholders involved is relatively small, even in these clusters. Specifically, only around 1% of shareholders in è nostra and a mere 0.001% in Ecopower are inclined to engage in volunteering activities. This suggests that while there is a segment of highly engaged individuals within these clusters, the overall level of participation in resource-intensive activities remains limited.

Graph 3.

Mean member public engagement in the cooperatives across clusters.

Graph 3.

Mean member public engagement in the cooperatives across clusters.

These quantitative findings are corroborated by the insights gathered from our interviews with shareholders and staff in both cooperatives, which confirm that only a few individuals actively participate in their activities. Nevertheless, despite this low level of participation – which aligns with the notion of an ‘homo economicus’ reluctant to allocate personal resources for managing common goals – our quantitative data reveal the presence of highly engaged shareholders within the two communities [

63]. Certainly, financial motivations play a role in one’s decision to join and remain in the cooperative, as clearly emerges in the interview data; for instance, one interviewee stated, ‘

I won’t remain in Ecopower if I have to pay three or four times more’ (Interview 15). However, it is important to note that this concern is relatively counterbalanced as many individuals are attracted by the political and social projects underlying their communities. This holds true even for those who exhibit a lower degree of involvement, as expressed by one interviewee: ‘

I am generally a principled person, so I am also very interested in economics, but I am interested in how it can be used to improve the world, like the idea that the cooperative could be an alternative to capitalism’ (Interview 18). Moreover, some members stated their commitment to remaining in the cooperative even if prices were to increase. They are willing to forget their dividends if it proves beneficial to supporting their organizations and their objectives.

A second noteworthy finding from our qualitative investigations is that the reasons for non-participation are not primarily linked to a lack of interest. The main obstacle mentioned by most shareholders is the constraint of time, particularly when they have family responsibilities. Furthermore, delving deeper into the interviews, shareholders revealed a strong sense of transparency and trust towards the executive board and staff. It became apparent from the interviews that many shareholders feel well-informed, mainly through communication channels such as emails, and are supportive of the activities and initiatives undertaken by their cooperative. Consequently, shareholders do not perceive a compelling need to be more actively engaged, as they believe the executive board of their cooperative is already effectively fulfilling its responsibilities towards members. One shareholder expressed this sentiment by stating, ‘I do not feel the need to participate in the general assemblies because they always explain very clearly what they are doing, and so far, I agree with and understand their actions’ (Interview 15).

The executive board and staff understand and support this choice:: ‘You could say people don’t participate in the general assemblies. But if you are happy with your supplier, you get a lot of information, so why should you go to the meeting on a Saturday morning?’ (Interview 20); ‘Some people are not interested in participating, and we must respect that. They are happy just to have a green and honest supplier and they already make them participate by contributing to the shift towards a greener and fairer transition’ (Interview 16). In particular, they highlight how having a high level of participate can also constrain the cooperative’s management: ‘So yeah of course in our general assemblies in Ecopower only 450 people of the 70,000 come… but luckily they don’t all come’ (Interview 20). This difficulty is particularly evident when engaging groups that aspire to become more active – ‘active shareholders’ – which presents both an opportunity and a challenge for the cooperatives in terms of establishing involvement procedures that benefit both parties. Hence, the cooperatives’ objective is to create avenues for individuals who are eager to actively engage, primarily at the local level. Additionally, the cooperatives aim to tap into the expertise of those who possess renewable energy knowledge, all while refraining from imposing moral expectations or making judgements regarding those who opt to limit their involvement to shareholding: ‘What is more important to me is to have the right structure which allows for this participation. I think there are different levels of participation, and we should facilitate this by providing the right structure’ (Interview 8).

The executive board also highlighted the importance of shareholders’ informal participation: ‘If somebody does not feel like taking the floor in the communities, they can also organize a dinner at home with some friends and diffuse the cooperative model’ (Interview 1). In our interview data, we can observe an important, informal way of contributing to the cooperatives’ development through disseminating information on their energy provider through one’s personal network: ‘I am among the nine out of ten who do not attend the general assemblies, but nevertheless, I contribute in a different way’ (Interview 17); ‘I also talked to my father and mother-in-law for example and it’s not the most, like, most sexy conversation topic’ (Interview 17); ‘When I make a presentation, I always put up my slides: the energy used for this PowerPoint is 100% renewable and sustainable, and I put on the slogan of è nostra’ (Interview 10).

Finally, some of the members of the two cooperatives stress how being a part of these organizations crucially allows them to create a sense of community. This feeling is especially strong for è nostra shareholders and may be related to the generally low level of interest in climate issues in Italy compared to in Belgium: ‘For years, I have been caring for the climate, but I felt alone. Since I started taking part in the cooperative, this is not the case anymore… è nostra is a part of me’ (Interview 2).

4.1.2. Private Engagement

In both cooperatives, there is a significant emphasis on taking responsibility for energy and sustainability matters. Furthermore, upon conducting a more detailed analysis of our index, we can identify variations in both energy-related practices and broader sustainable behaviours among shareholders. For instance, examining the item ‘paying attention to reduce energy consumption’, we find that 70% of Ecopower shareholders and 75% of è nostra shareholders strongly emphasize this aspect. However, when we consider sustainability behaviours that are not directly related to energy, 81% of è nostra members consistently adopt them, whereas the results for Ecopower are more varied. Specifically, 47% of Ecopower shareholders claim to always follow these principles, while 41% do so only sometimes. Interestingly, individuals with higher financial motivations tend to exhibit positive practices regarding energy savings but perform less consistently on the other sustainability items (

Table A5 and

Table A6 in

Appendix A). The cluster analysis also shows that generally groups exhibit a heightened awareness of their behaviours concerning energy and sustainability issues. However, this tendency is particularly homogeneous among shareholders in è nostra in comparison to Ecopower, where we observe greater diversity in private practices among members (

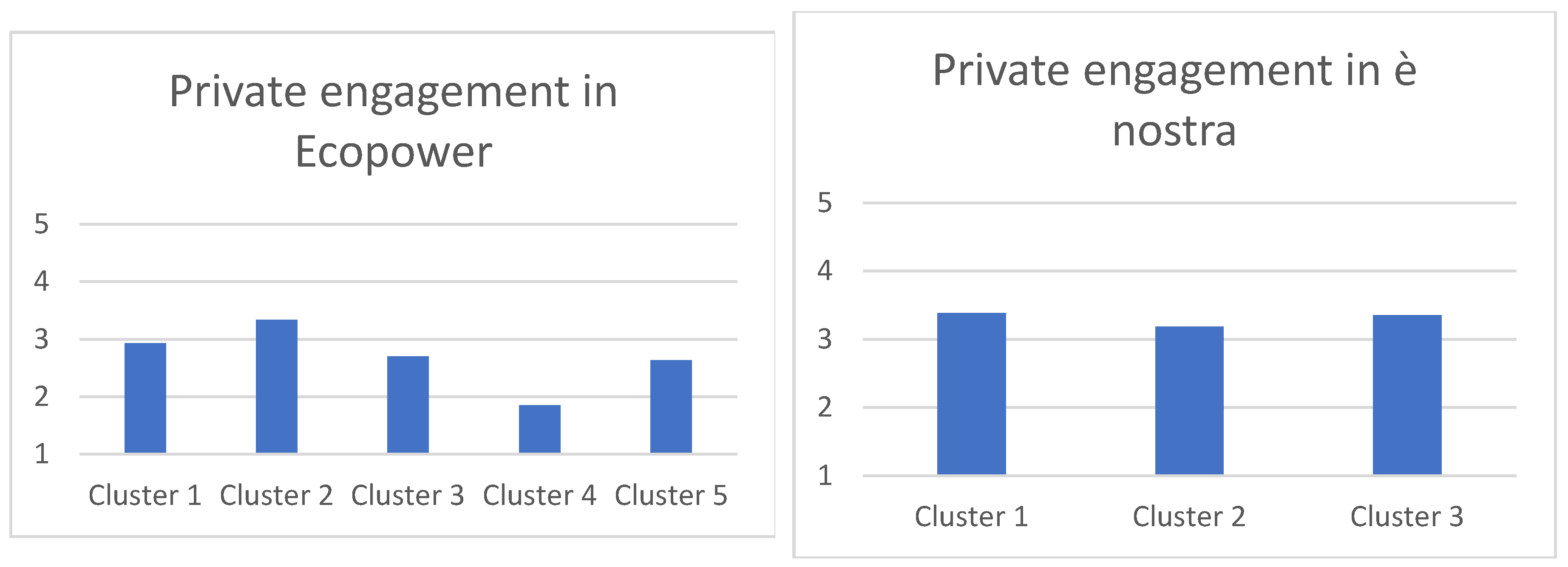

Graph 4).

Graph 4.

Mean private engagement of cooperative members across clusters.

Graph 4.

Mean private engagement of cooperative members across clusters.

These findings are supported by the results of our qualitative interviews. A significant portion of the shareholders express a strong sense of awareness regarding energy and sustainability, albeit with some limitations especially in Ecopower: ‘We’ve tried to be sustainable in general and especially regarding our energy practices …There’s always a balance between luxury and what is economically feasible so we’re not very extreme in this respect but we’re working on it’ (Interview 13);. However, it is worth noting that a subset of shareholders demonstrates a remarkably high level of attentiveness, as seen in Cluster 2 of Ecopower and Clusters 1 and 3 of è nostra: ‘We almost never use cars, even if we have four children. We use bikes. Even when we go on holiday, we try to take bikes and we prefer to stay close to home, choosing local destinations in order to limit our environmental impact (Interview 15).; ‘I decided to get rid of my freezer as it accounted for one third of my energy consumption’ (Interview 20).

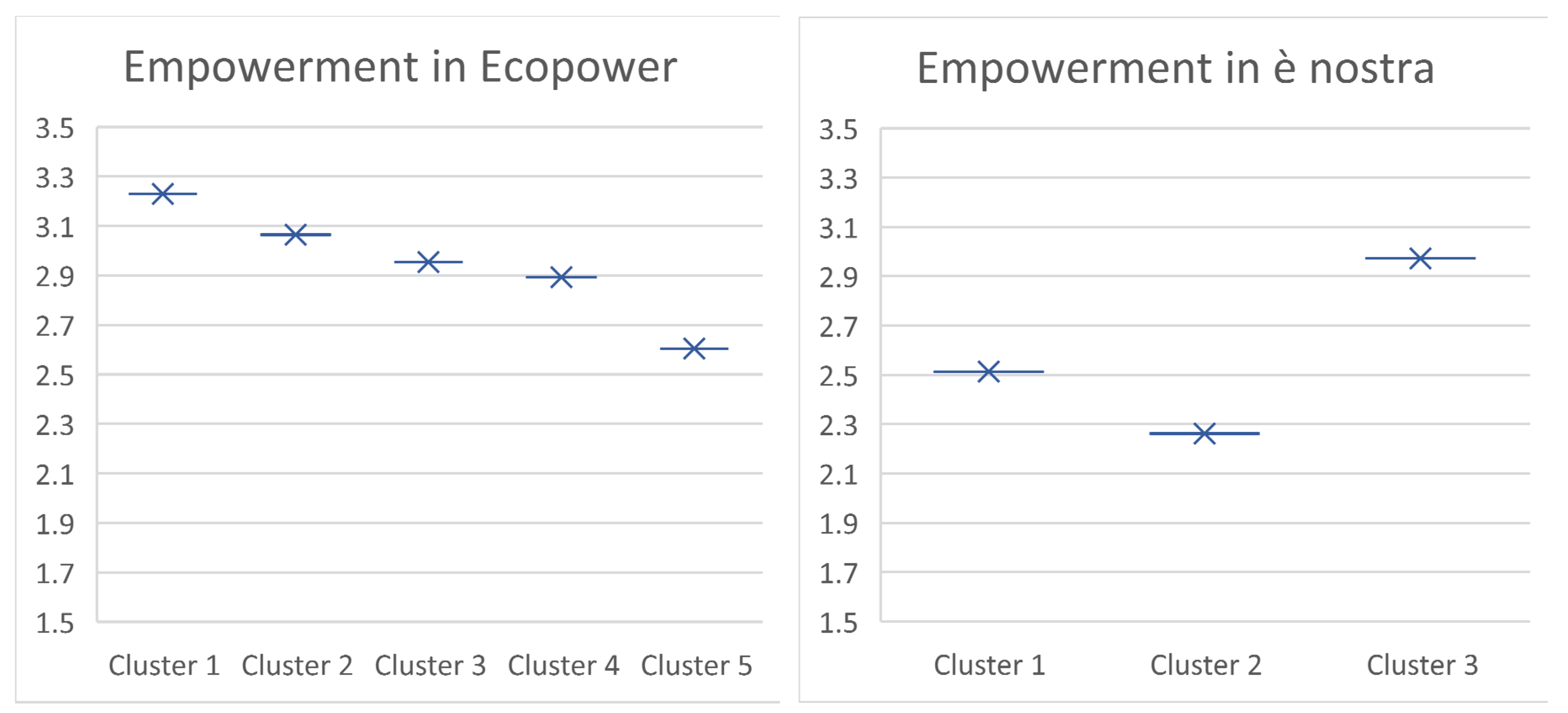

4.2. Empowerment

As underlined previously in the literature, energy communities raise strong expectations on the issue of empowerment (

Graph 5), However, between the two cooperatives, the pattern appears to differ quite notably, as the shareholders of Ecopower present a higher level of empowerment than those of è nostra. This supports Coenen and Hoppe’s [

64] recent findings that joining a REScoop results in a more than 20% reduction in electricity consumption. Additionally, it highlights the excellent results of Ecopower members compared to other cooperatives, such as è nostra, specifically regarding the item empowerment. Indeed, the predictive margins of our model show that 40% of the è nostra shareholders think that they have not gained competencies from participating in the cooperative, compared to only 24% of the Ecopower shareholders. Those declaring that they care about making a profit are most likely to declare having obtained competencies concerning energy issues compared to those less focusing on economic motivations (

Table A7). Furthermore, going deeper in the analysis, the cluster analysis shows that not all shareholders in è nostra or Ecopower are equally likely to experience a knowledge gain from their participation. Empowerment is more likely to occur when shareholders actively engage in their communities as in Cluster 3 for è nostra or Cluster 1 for Ecopower. In the case of Ecopower, this applies to individuals with minimal sustainable practices as well as those who are highly aware.

Graph 5.

Mean empowerment in the cooperatives.

Graph 5.

Mean empowerment in the cooperatives.

These quantitative results are confirmed by the qualitative interview data. In Ecopower, the executive board confirmed how empowerment is generated by being a member of the cooperative: ‘What’s really showing the effect of becoming a member is that if you take the ones without solar panels, our shareholders consumed 20% less than the average in Belgium… Some people choose to replace their light bulbs, upgrade to a more energy-efficient refrigerator, or even discard their freezer altogether’ (Interview 20). Furthermore, the official line of Ecopower’s executive board appears to be very clear: ‘Ecopower has been, let’s say, successful in being the cheapest supplier…But I often say paying €250 for the cheapest electricity doesn’t make this person a cooperative member. He becomes a client, and then it is up to the cooperative to inform this person, to educate this person, so that over time, he becomes inspired by the cooperative idea, so it’s a job that every cooperative has to do’ (Interview 20).

Ecopower already has three people working full time in order to promote public engagement. They organize numerous webinars as well as events such as an ‘Energy Café’, where people can meet and exchange information about their practices. Ecopower also highlights the potential of knowledge co-construction, with some shareholders giving their expertise during webinars, or exchanging insights on an online platform to improve the use of software that helps people monitor their consumption (Interview 14). By contrast, è nostra is still looking to give a frame to shareholders’ participation: ‘We are not yet ready for such structured processes of involvement’ (Interview 6).

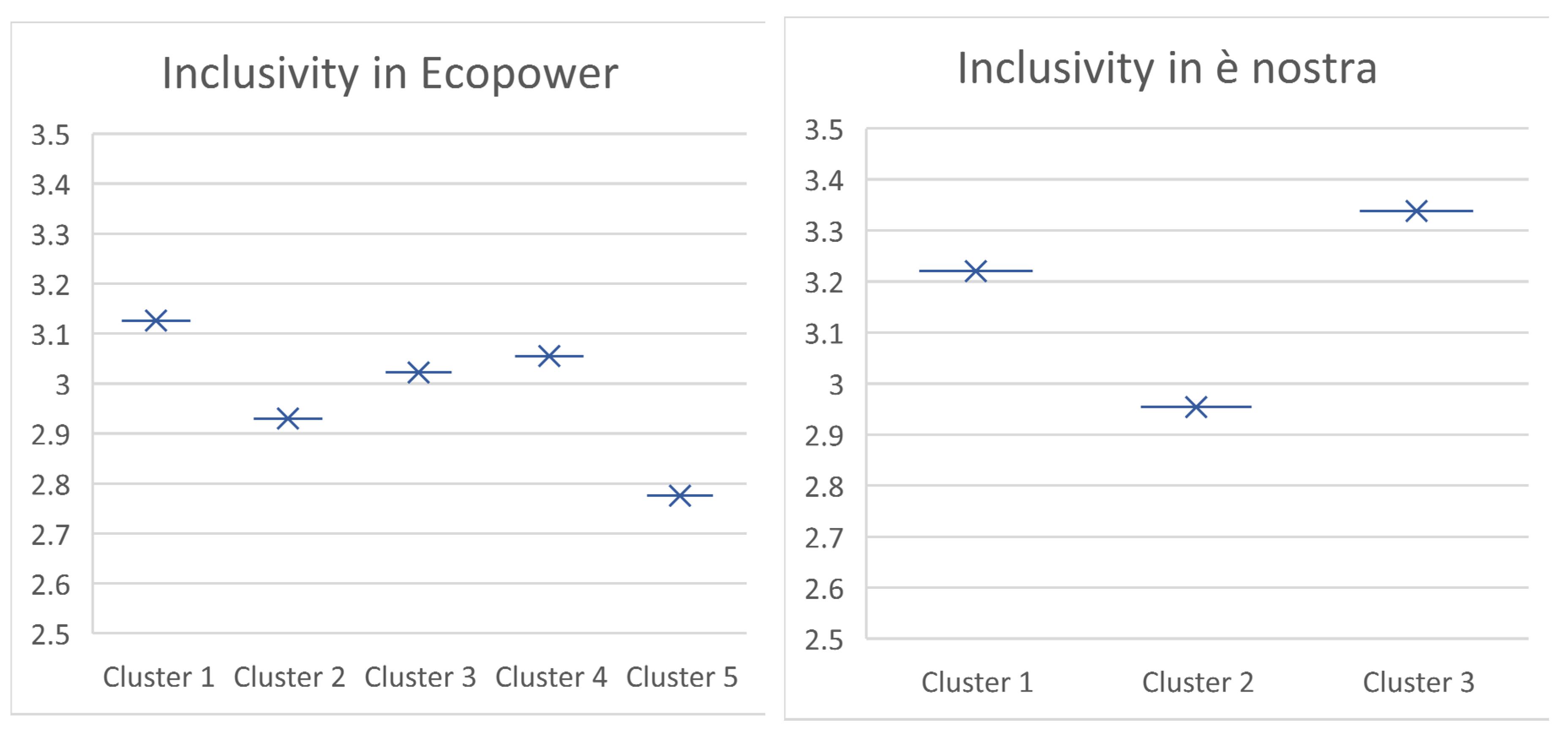

4.3. Inclusivity

The last dimension we investigated was the risk of energy citizenship proving somehow exclusive. Indeed, as already shown in the sample description, the people participating in the cooperatives are mostly male, with a medium-high income and a STEM background. Such similarity of profiles is confirmed by the fact that the clusters tend to excess the mean of the variable, corresponding to males with a degree in STEM and relatively good incomes. These results are also confirmed by the interviews in which members even stressed their social homogeneity, including with regard to empowerment activities. Certainly, the shareholders tended to agree that they were already very concerned about the environment or were passionate about renewable technologies.

Furthermore, upon closer examination of our results through the cluster analysis, certain differences between the two cooperatives become apparent. Firstly, only Cluster 5 in the case of Ecopower demonstrates a higher level of inclusivity. Interestingly, it can be observed that shareholders belonging to this cluster also tend to have minimal or limited involvement in their organization, along with a moderate level of practice related to sustainability awareness: ‘

We have to be honest, most of the people would just choose the cheapest supplier’ (Interview 18). Secondly, gender inequalities play a more significant role in Ecopower compared to in è nostra. In è nostra, there is a high representation of women, which is quite distinctive within the energy community context [

65,

66]. Another noteworthy point regarding Ecopower is that our findings indicate that individuals with a high school degree or lower educational attainment benefit the most from the knowledge provided by their cooperative. This is not limited to those who already possess a strong background in STEM fields, which further enhances the cooperatives’ inclusive dimension of empowerment (

Table A7 in

Appendix A).

Graph 6.

Mean inclusivity in the cooperatives.

Graph 6.

Mean inclusivity in the cooperatives.

As emerges from our study, the executive board of both cooperatives is aware of this issue, recognizing that they face difficulties in reaching some sections of the public. However, again, a major difference can be observed between the two cooperatives. Ecopower is already seriously tackling this issue: ‘We are offering parallel workshops focusing on both the technical side and the social aspects of our cooperative’ (Interview 16). To the contrary, è nostra is still not addressing this issue: ‘The category of vulnerable consumers is a category that the cooperative has never directly involved’ (Interview 1).

if for the board the lack of inclusivity is a problem, it is not always the case for the shareholders. In particular, some shareholders believe that addressing inequality issues should not be a primary goal for energy cooperatives, arguing instead that such responsibility lies with the government: ‘I think it is also the responsibility of the state. We cannot put everything on the shoulders of individuals or the third sector’ (Interview 15). One reason cited for that is the fact that even though the organisational structure of cooperatives sometimes lacks inclusivity, they still contribute to increasing the well-being of every citizen, by promoting the growth of clean energy.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Our findings support the notion that energy communities serve as fertile ground for the development of the concept of energy citizenship. However, it is important to acknowledge that energy citizenship should be understood as a multifaceted rather than singular and idealized concept [

26]: ‘

a label, let’s say, that is useful for thinking about the possibilities of including citizens in the energy transition’ (Interview 9). This perspective is widely shared among the staff and members of the energy communities considered here, who emphasize that the concept of energy citizenship, in its strict sense, is only partially connected to their respective organizations. Hence, when discussing energy citizenship, it is essential to recognize the diverse ways in which individuals contribute to the diffusion of the energy transition.

In particular, in our study we have identified four engagement profiles. In the first pattern (

Cluster 5 for Ecopower and

Cluster 2 for è nostra), the cooperative is seen more as a means of reinforcing a pre-existing ‘

sustainable way of life’. These individuals express a heightened consciousness and awareness compared to the average, but they do not actively engage in cooperative activities. Instead, their focus lies in making conscious consumer choices [

13]. This tendency emerges also in our qualitative interview findings: ‘

I am more like conscious and aware compared to the average I would say. I’m not an active member. I just I like the ideology It’s more my consumer choices, I think’ (Interview 18).

The second profile we have identified has a priori limited knowledge or interest in energy and sustainability and is instead attracted by potential economic benefits (

Cluster 4 in Ecopower). In particular, this category strongly expects to see growth [

67]. Indeed, these members align with the concept of ‘

financial investors’, joining a cooperative primarily due to the potential economic benefits it offers. Their main motivation is to secure financial returns rather than to actively participate in the cooperative’s activities.

There are different advantages and disadvantages regarding the presence of this group of members. Some members of staff in both cooperatives deem it important not to impose overly strict expectations on the individuals participating in an energy community. On one side, even though their involvement is limited, their presence as financial investors contributes to their cooperative’s financial sustainability and growth. As shown by our results, financial motivations are also not necessarily in conflict with the goal of empowering members within the cooperatives. In particular, financial incentives can be seen as a potential means to attract individuals who may be less familiar with energy and sustainability issues, thereby promoting inclusivity. For instance, Ecopower, unlike è nostra, manages to reach individuals who do not already possess a good level of awareness regarding energy and sustainability. This particular group of members is more diverse compared to others. Overall, having less restrictive expectations can foster inclusivity and engage a broader range of participants in energy communities. Moreover, as underlined by the staff of Ecopower, with time, people mature and become more engaged: ‘Even when they are not very engaged or very active, we instil them with the cooperative’s values and it’s still good. I think it’s the other side of the coin when you increase the size of the cooperatives. There are a lot more people and that is fair’ (Interview 14).

Nevertheless, as emphasized by authors such as Bauwens et al. [

68], with regard to social entrepreneurship, it is crucial to maintain a steadfast focus on the cooperative’s philosophy as it continues to expand. This aspect was also highlighted in our interviews, where the executive board in both cooperatives emphasized the distinction between prospective members and traditional financial investors. They aim to remain grounded in an institutional logic that prevents a shift of focus from the community’s well-being to purely profit-driven motives in the market [

51,

69].

The third group are the pragmatic. These are people who already identify with sustainability or are at least trying to achieve a low-carbon lifestyle, and are interested in following their communities’ activities but with limitations, often due to their restricted time (Clusters 2 and 3 for Ecopower and Cluster 1 for è nostra). Therefore, these individuals place high levels of trust in their executive board and prefer to delegate their decision-making power, believing that the board is capable of making the right choices. Their engagement is high but quite informal, as they contribute to the dissemination of their energy communities’ model through word-of-mouth interactions with family members and friends and on online platforms: ‘When there is discussion about Ecopower on Twitter, a lot of members always get really involved in it, they defend Ecopower and show that they are proud to be members’ (Interview 19).

Moreover, approximately 10% of this group express a desire to be more actively involved in their communities, particularly focusing on the development of local activities. The aspect of empowerment is also significant, as these individuals show a strong inclination to read newsletters and participate in training programmes. They display a keen interest in enhancing their knowledge about energy and changing their behaviours: ‘It becomes like a game, once you’ve started you can’t stop’ (Interview 13).

The last group is the closest to the ideal of energy citizenship: ‘

the green heroes’ (Cluster 1 for Ecopower and Cluster 3 for è nostra). They tend to be strongly engaged in their cooperative and exhibit strong sustainable practices. Already aware of their practices and empowered about sustainability, they contribute to fostering the model by volunteering for their organization or creating local energy communities [

70,

71,

72]. Although this figure is numerically more present in è nostra, reflecting a more political approach to energy communities, we should underline that in Ecopower the potential of these people is being exploited to a greater extent, through knowledge co-creation. Furthermore, even though the presence of these ‘green heroes’ is generally seen as a positive aspect, there are also limitations to consider. Firstly, as emphasized by the executive board, managing an energy cooperative can become challenging if too many individuals seek to be highly involved. Excessive participation may result in counterproductive outcomes. Secondly, limiting energy communities to this notion of energy citizenship overlooks the importance of inclusivity. The green heroes primarily consist of individuals who are already deeply committed to sustainability, which can give the impression of the cooperative being an ‘elite club’ (Radtke and Ohlhorst 2021). This may pose difficulties for the wider diffusion of the cooperative model within the society at large [

73,

74].

Ultimately, we argue that all cluster groups, regardless of their level of engagement, exhibit varying degrees of responsibility and awareness regarding climate change as well as differing levels of engagement in the energy transition. They thus all appear to serve as a means to promote a fairer and more sustainable society, shifting the focus of energy from a mere commodity to a broader societal concern. Accordingly, it can be seen that the concept of energy citizenship idealized in the majority of the literature is very restrictive and does not fit with the general behaviours of the people taking part in these initiatives. Indeed, only a small group of people can be regarded as conforming with these expectations.

In particular, one of the key challenges for energy communities is to attract individuals who may not be familiar with sustainability concepts, but who could greatly benefit from these initiatives. This requires, from both a theoretical and an empirical point of view, a broader definition of energy citizenship, as a general feeling of belonging to a community which can be translated into various and complex forms of engagement. Furthermore, an important area for further research would be to examine the impacts of the scaling of energy cooperatives on energy justice and energy democracy.