Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer in males

after lung cancer, with an estimated 1,600,000 cases and 366,000 deaths annually. This cancer accounts for

7% of newly diagnosed cancers in men worldwide and is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths among men in developed regions[

1]. The prognosis for an individual with PC is highly variable and dependent on the tumor grade and stage at primary diagnosis. Current methods for early detection, such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing and digital rectal examination (DRE), allow for the diagnosis of most men when the disease is in its early stages. About 80% of men are diagnosed with organ-confined PC, 5% with locoregional metastases, and 5% with distant metastases. For men with localized PC, the potential for a long life is high, with a 10-year survival rate reaching as high as 99% if the cancer is detected early. However, men who are diagnosed with advanced-stage PC, characterized by distant metastases, have a much bleaker prognosis, with only a 30% overall survival (OS) rate at 5 years[

2].

Androgen deprivation therapy, often combined with an androgen receptor pathway inhibitor, represents a standard initial treatment approach for males diagnosed with advanced PC. However, a significant majority of patients eventually experience disease progression even while undergoing hormonal therapies, leading to the clinical state known as metastatic castration-resistant PC (mCRPC)[

3]. The precise mechanisms underlying the transition from androgen-dependent (referred to as hormone-sensitive or castration-sensitive) PC to CRPC remain largely elusive. mCRPC has a poor prognosis, with an expected median survival of only 2 to 3 years[

4]. For males with metastatic and nonmetastatic CRPC, multiple active life-prolonging therapeutic options have emerged in the last decade. This article is intended to review novel radiotherapy and antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) for the treatment of CPRC.

Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigens

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a type II membrane protein that functions as a glutamate-preferring carboxypeptidase in all forms of prostate tissue[

5]. PSMA expression is also found in the salivary and lacrimal glands, liver, spleen, bowel, kidneys, and sympathetic ganglia. Studies have found that PSMA is highly overexpressed in PC around 100 to 1000 times the normal level, especially in advanced cancer. In Sven Perner’s study[

6], the expression levels of PSMA exhibited statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) across benign prostatic tissue, localized PC, and lymph node metastases. It was observed that elevated levels of PSMA and the presence of metastases correlated with the time of PSA recurrence (HR, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.1 – 2.8, P = 0.017; and hazard ratio, 5; 95% confidence interval, 2.6 – 9.7, P < 0.001, respectively). This finding represents the diagnostic and therapeutic value of PSMA, which is used as a targeted antigen.

PSMA PET-CT for Imaging Prostate Cancer

Typically, the diagnosis and risk stratification of PCa are dependent on PSA level, DRE, and traditional

imaging techniques, such as CT, MRI, and bone scans. Although PSA level and DRE help increase the early detection of PC, its low specificity would lead to overdiagnosis[

7]. Furthermore, in the detection of PCa with lymph node metastases, CT and MRI demonstrate a great limitation since

they are unable to detect lymph nodal lesions smaller than 8 mm[

8]. PSMA PET-CT is a combination of molecular target and image technology, which could enhance the precision of PCa detection by labeled with radioisotopes.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) combines two imaging techniques: PET and CT. PET works by injecting a small amount of radioactive tracer into the human body. This tracer accumulates in tissues with high metabolic activity, such as tumors, and emits positrons. When these positrons encounter electrons, they produce gamma rays, which are detected by the PET scanner to create images showing the metabolic activity of tissues. CT uses X-rays to produce images of internal structures in the human body. The combination of PET-CT provides both functional information from PET and anatomical details from CT, which is widely used in clinical oncology to detect, stage, and monitor cancer.

Realizing the therapeutic potential of radiolabeled PSMA targets, several PSMA-targeting agents have been developed as tracers for PET-CT in the last 20 years. The first approved radiolabeled compound targeting PSMA was indium-111 capromab pendetide, which received its approval from the FDA in 1996[

9]. The most widely used agent

68Ga-PSMA-11 was developed by Matthias Eder at the German Cancer Research Center in 2012 and was approved by the FDA (in 2020) and EMA (in 2022)[

10]. The use of

18F-labeled ligands, such as 18F-PSMA-1007, is becoming more prevalent in PSMA imaging due to their superior imaging properties. 18F-PSMA-1007 has better positron energy, higher positron yield, and longer half-life, which enhance image quality and reduce noise[

11].

PSMA PET-CT has proven to be highly advantageous over traditional imaging techniques in the diagnosis of PCa. In a meta-analysis by Satapathy et al.[

12], PSMA PET-CT demonstrated a high sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 66% for the primary detection of PCa. Additionally, in primary lymph node staging, PSMA PET-CT is prior to conventional imaging methods such as CT and MRI, with higher sensitivity (73.7% vs 38.5% vs 38.9%) and specificity (97.5% vs 83.6% vs 82.6%) for detecting lymph node metastases[

13].

Otherwise, conventional methods need to detect metastases at much higher PSA levels. For instance, bone scans could only identify osseous metastases at a median PSA value around 40 ng/mL, and CT scans show poor lymph node detection rates below 20 ng/mL of PSA[

14]. In contrast, PSMA PET-CT demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity, which could detect recurrent disease at much lower PSA levels. In Sadeq Abuzallouf’s study[

15], PSMA PET can identify 51.5% of patients with potential sites of recurrence at PSA < 1.0 ng/mL, and 90% at PSA >2.0 ng/mL. Moreover, PSMA PET-CT also shows remarkable value in the evaluation of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC). In a study involving 200 patients with nmCRPC, PSMA PET detected 55% of patients presenting distant metastases (M1) despite negative results from conventional imaging[

16]. These findings highlight the potential of PSMA PET-CT in primary staging and the detection of metastatic and recurrent diseases, including mCRPC, making it an essential tool for the early diagnosis and management of high-risk PC patients.

177LU-PSMA Radiotherapy

177Lu-PSMA-617 (Pluvicto

TM) is a radiopharmaceutical product approved by the FDA for the treatment of PCa. The development of

177Lu-PSMA-617 began in 2012, building on previous work involving the Glu-urea-Lys binding motif, which had already been characterized for its strong affinity to PSMA[

17]. Though the early urea-based inhibitors are effective in targeting tumors, it came up with a challenge that it demonstrated a high uptake in non-target organs, particularly the kidneys[

18]. Researchers at the German Cancer Research Center enhanced the compound to optimize its pharmacokinetic properties. This led to the creation of PSMA-617 (Vipivotide tetraxetan), which exhibited high tumor uptake and low retention in non-targeted tissues[

19]. For several years, clinical trials of

177Lu-PSMA-617 began showing promising results in multicentric studies and phase III trials, and it received FDA approval in 2022[

17].

The structure of

177Lu-PSMA-617 contains three components: 1) a PSMA-binding motif (Glu-urea-Lys), 2) a chelator (DOTA), and 3) a linker (comprising 2-naphthyl-L-alanine (Nal) and tranexamic acid (TXA))[

20]. This structure allows DOTA chelated with lutetium-177, a beta-emitting radionuclide with a half-life of 6.64 days. Once injected into the body, the binding motif binds selectively to PSMA-positive cancer cells. The radioligand is then internalized into the cancer cells, where the beta particles emitted by lutetium-177 cause DNA damage and then lead to cell death. The

177Lu isotope has a maximum range of 2.2 mm and an average range of 0.67 mm, categorizing it as a short-range β-particle emitter[

17]. This limited range allows the particle to penetrate and eliminate PSMA-positive cells, while its impact on adjacent healthy tissue remains minimal. Additionally, the low-energy gamma emissions from lutetium-177 enable post-therapy imaging, allowing doctors to monitor the treatment’s progress and adjust dosages as needed[

21].

177Lu-PSMA-617 is recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s guidelines for the treatment of patients with PSMA-positive M1 CRPC who were previously treated with androgen receptor-directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy (such as docetaxel)[

22].

177Lu-PSMA-617 has been shown to improve progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in patients with progressive mCRPC. As evidenced by the phase II trial ANZUP 1603[

23],

177Lu-PSMA-617 demonstrated a higher rate of a ≥50 percent PSA decline compared with the cabazitaxel group (66% vs. 37%) in mCRPC patients who previously received docetaxel and androgen receptor-directed treatment. This trial also reported fewer grade 3 or 4 adverse events and better patient-reported outcomes. The phase III VISION trial further validated the benefits of

177Lu-PSMA-617 by showing significant improvements in median radiographic PFS (8.7 vs. 3.4 months) and median OS (15.3 vs. 11.3 months) and was associated with a higher objective response rate (30% vs. 2 percent%) compared with standard care[

24]. These findings underline its potential as a preferred treatment over traditional options such as cabazitaxel, particularly in the management of advanced PC.

Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

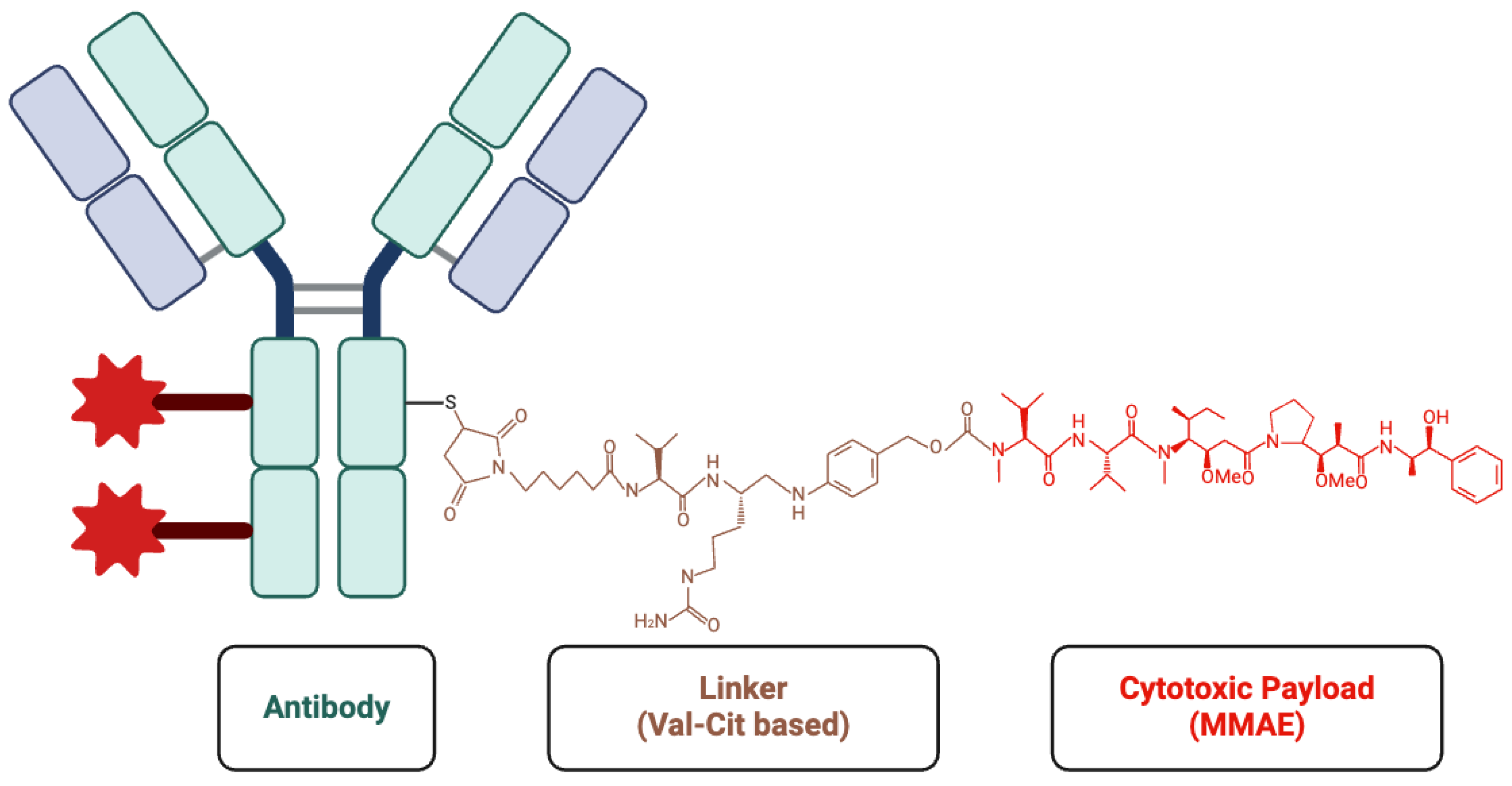

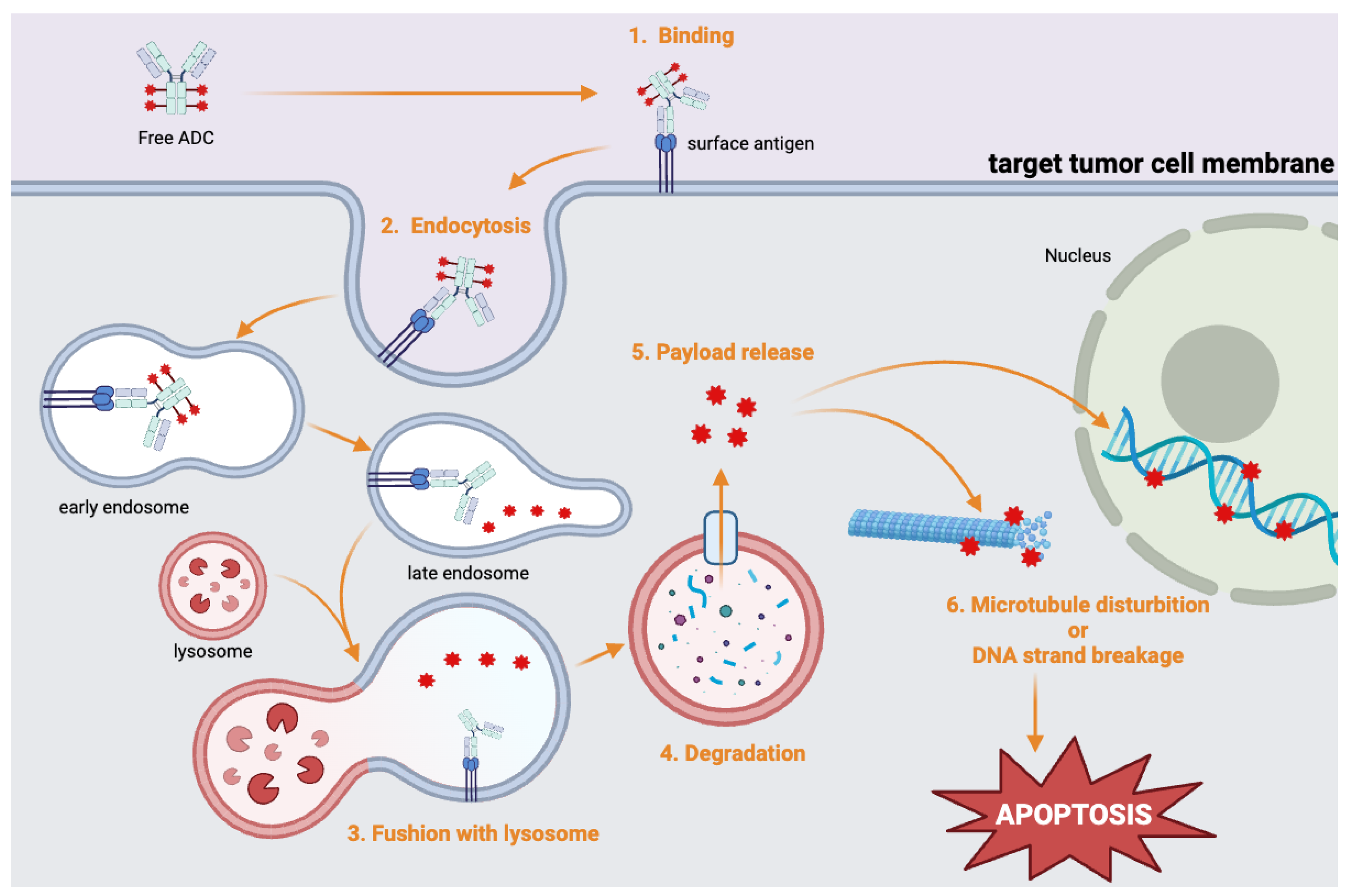

ADCs have emerged as an innovative and promising approach in targeted cancer therapy. ADCs combine monoclonal antibodies, which specifically target tumor antigens, with potent cytotoxic agents to selectively destroy cancer cells while reducing off-target toxicity[

25] (

Figure 1). Initially, ADCs were primarily used to treat breast cancer and malignant lymphoma, such as gemtuzumab ozogamicin for acute myeloid leukemia and trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) for HER2-positive breast cancer[

26]. More recently, ADCs such as enfortumab vedotin (approved in 2019) and sacituzumab govitecan (approved in 2021) have received FDA approval for UC treatment[

27], highlighting the growing role of ADCs in the field of urology.

ADCs consist of three main components: an antibody, a linker, and a cytotoxic drug (payload). In ADC design, selecting stable, antigen-specific antibodies is critical for ensuring precise drug delivery to tumor cells while avoiding healthy tissues. These antibodies must distinguish between tumor and normal cells to prevent off-target toxicity. Humanized IgG is commonly used in ADC to reduce immune reactions associated with non-human antibodies[

28].

Linkers connect the antibody to the cytotoxic drug and play a crucial role in the release of drugs. Cleavable linkers are sensitive to the intracellular microenvironment, which releases the drug by hydrolysis or protease cleavage within endosomes. While non-cleavable linkers represent greater stability, on the other hand, they only release cytotoxic drug in lysosome[

29].

The payload is a potent cytotoxic drug that is delivered directly into tumor cells in high concentrations. These payloads can be categorized as either microtubule disruptors or DNA-damaging agents. For instance, monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) disrupts microtubule assembly and induces apoptosis[

30]. SN-38 is a topoisomerase I inhibitor that causes DNA damage[

31]. The use of these cytotoxic agents makes ADCs particularly effective at killing cancer cells (

Figure 2).

Anti-PSMA Monoclonal Antibodies

Compared with small molecule agents (∼1.4kD) such as Glu-urea-Lys in

77Lu-PSMA-617, monoclonal antibodies have a larger molecular weight (approximate 150 kDa). While larger molecular weight would dramatically decrease the glomerular filtration rate of antibody-based drugs, this characteristic leads to a longer half-life[

32]. Otherwise, several studies have shown that antibodies demonstrate better tumor uptake and more uniform distribution, primarily due to an optimal balance between their in vivo half-life and vascular/tissue penetration abilities[33-34].

7E11

The 7E11.C5 antibody is a murine monoclonal antibody that recognizes the intracellular domain of PSMA, which was generated by immunizing mice with human PC LNCaP cells[

35]. Subsequent immunohistochemical studies confirmed its strong specificity for epithelial cells in prostate tissue, with only limited expression observed in other tissues, such as the brain, salivary glands, and small intestine[

36]. The 7E11.C5 antibody binds to a linear epitope composed of the first six amino acids at the N-terminal of PSMA, which is located on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane. This intracellular localization restricts its ability to detect living cells, as the epitope becomes accessible primarily in apoptotic or necrotic cells. This unique property forms the basis of its application in the ProstaScint™ imaging agent for the detection of PC, although the requirement for substantial quantities of nonviable cells limits its diagnostic sensitivity, particularly for smaller tumors. Despite these limitations, 7E11.C5 has played a critical role in PSMA research, laying the foundation for the development of more advanced antibodies and therapeutic strategies targeting PSMA.

J591

J591 is the first humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the extracellular domain of PSMA, which has shown potential in both diagnostic and therapeutic applications. When conjugated with the radionuclide lutetium-177, J591 delivers targeted radiotherapy by binding to PSMA, leading to internalization and radiation-induced cell death. Clinical trials with

177Lu -J591 have demonstrated its ability to reduce PSA levels and stabilize disease in a significant number of patients. Imaging studies confirmed tumor targeting, and PSA reductions of over 30% were seen in many patients[

37].

225Ac-J591 is composed of radioactive particles Actinium-225 and J591. A phase I trial recruited 32 patients with mCRPC and treated them with a single dose of 225Ac-J591. As a result, 46.9% of patients experienced a 50% decline in PSA, and 59.1% had a positive response in circulating tumor cell (CTC) counts[

38].

89Zr-DFO-J591 is a radiotracer for immunoPET imaging. In a study, 89Zr-labeled J591 demonstrated high radiochemical yield ( > 77%) and purity ( > 99%) and maintained strong immunoreactivity for up to 7 days. In vivo studies on mice with PSMA-positive tumor cells (LNCaP) showed significant tumor-specific uptake, reaching 45.8% after injection for 144 h. ImmunoPET imaging provided excellent tumor-to-muscle contrast, allowing the clear delineation of PSMA-positive tumors. The complex showed high in vivo stability and thermodynamic favorability, ensuring its reliable performance[

39]. Overall, J591 shows great potential for both non-invasive imaging and radiotherapy in the treatment of PC. Due to its high specificity for PC cells and tumor uptake rate, J591 is a promising tool for enhancing the accuracy of diagnostic imaging and improving the efficacy of targeted radiotherapy in clinical applications.

5. D3

5D3 is a monoclonal antibody that specifically targets the extracellular domain of PSMA. Unlike earlier antibodies, such as J591, 5D3 binds specifically to surface-exposed conformational epitopes of native PSMA. It demonstrates high specificity, minimal cross-reactivity with unrelated proteins, and approximately 10-fold higher affinity than J591[

40]. Moreover, the 5D3 Fab fragment achieved an even faster tumor-specific contrast in the NIRF image, which is visible within 2 h and sustained through 24 h. 5D3 is also implanted in 111In-DOTA-5D3 as a surrogate for therapeutic isotopes such as 177Lu or 90Y. In mice bearing PSMA (+) PC3 PIP xenografts, tumor uptake peaked at 24 h postinjection and remained high until 72 h. Compared with control experiments xenografted with the PSMA (−) PC3 flu cells, it revealed no specific binding up to 24 h after incubation[

41]. These results highlight the tumor specificity of 5D3.

ADCs Targeting PSMA in PC

PSMA-MMAE

NCT01414283

NCT01414283 is an open-label, dose-escalation phase 1 clinical trial investigating PSMA ADC in patients with mCRPC. The PSMA ADC consisted of a fully human anti-PSMA monoclonal antibody (mAb) conjugated to MMAE via a valine–citrulline linker, which was designed to be stable in the blood but cleaved intracellularly in PSMA-expressing PC cells. The mechanism of MMAE disrupts microtubule polymerization, inducing cell-cycle arrest and cell death. The trial enrolled 52 patients between October 2008 and October 2012, all of whom had progressive mCRPC with prior taxane-based chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria included significant cardiac or pulmonary disease, active infections, prior PSMA-targeting therapies, or a history of substance abuse. PSMA-MMAE was administered intravenously every three weeks for up to four cycles. If patients demonstrate clinical benefit, eligible will enter an extension study for up to 13 additional cycles (NCT01414296). The study was completed in September 2013.

The result of this trial was published by Daniel P Petrylak on

Prostate[

42]. The median age of the 52 patients was 70 years, and 62% of the patients had an ECOG performance status of 1. The study established the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of PSMA-MMAE at 2.5 mg/kg, and dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were observed at 2.8 mg/kg. Common adverse effects included fatigue (40%), neutropenia (33%), nausea (29%), and temporary elevations in liver enzymes (25%). Pharmacokinetic analysis showed that peak serum concentrations of free MMAE were reached 2–4 days post-infusion, indicating the slow release from ADC, and its half-life ranged from 2 to 3 days. Repeat dosing did not lead to a significant accumulation of the drug. PSMA-MMAE also demonstrated encouraging antitumor activity, particularly at doses ≥1.8 mg/kg. Among the treated cohort, 8 patients achieved PSA reductions of ≥50%, with maximum declines exceeding 90% in two cases. Changes in CTC counts further demonstrated the treatment’s efficacy: eight patients experienced a shift from unfavorable (≥5 cells/7.5 mL of blood) to favorable (<5 cells/7.5 mL) CTC counts at doses ≥1.6 mg/kg.

Over half of the participants completed at least four treatment cycles, and 10 patients continued therapy in an extension phase for up to 11 months. These findings highlight the potential of PSMA ADC as a therapeutic option for mCRPC, with a favorable safety profile and evidence of significant antitumor activity at the recommended phase 2 dose of 2.5 mg/kg.

NCT01695044

NCT01695044 is an open-label, single-arm, multicenter phase 2 clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of PSMA-MMAE in patients with mCRPC, which is also a further phase 2 trial of NCT01414283. The trial enrolled 119 patients at 28 U.S. centers between September 2012 and October 2014, including chemotherapy-experienced and chemotherapy-naïve subjects who must have received and progressed on abiraterone acetate and/or enzalutamide. Enrolled patients are divided into two groups: 1) prior history of treatment with at least one taxane-containing chemotherapy regimen, and 2) no prior history of treatment with a cytotoxic chemotherapy regimen but have received Radium-223. Patients received PSMA-MMAE at an initial dose of 2.5 mg/kg via intravenous infusion every three weeks for up to eight cycles, later adjusted to 2.3 mg/kg due to safety concerns, such as febrile neutropenia and sepsis. Subjects with clinical benefits after eight cycles could enter an extension study (

NCT02020135). The study was completed in February 2015.The result of this trial was published by Daniel P Petrylak on

Prostate[

43]. The median age of 119 patients was 71 years, and 96% of the participants had an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1. Efficacy analysis revealed PSA declines of ≥50% in 14% of all treated and 21% of chemotherapy-naïve subjects. CTC reductions of ≥50% were observed in 78% of patients (≥5 cells/7.5 mL of blood), and 47% achieved favorable CTC conversions (<5 cells/7.5 mL). Chemotherapy-naïve patients showed higher CTC response rates, with 89% demonstrating ≥50% declines and 53% achieving conversions, compared with 74% and 45% in the chemotherapy-experienced group, respectively. Safety analysis indicated that 95% of patients experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), with 58% reporting grade 3 or higher events. The most common AEs included neutropenia (36%), fatigue (34%), decreased electrolytes (29%), anemia (25%), and peripheral neuropathy (12%). Peripheral neuropathy was the leading cause of treatment discontinuation, which was reported by 14 patients. Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 51% of patients, and most of them suffered from dehydration, hyponatremia, or febrile neutropenia. Additionally, a smaller proportion of chemotherapy-naïve patients discontinued treatment before completing five cycles due to progressive disease or AEs (54% vs. 66%).

These findings demonstrate that PSMA-MMAE exhibits notable antitumor activity, with manageable toxicities at the recommended phase 2 dose of 2.3 mg/kg. Notably, chemotherapy-naïve patients showed more favorable outcomes based on greater PSA responses, CTC reductions, and OS (97.1% vs. 91.7%). The optimization of dose regimens and enhanced patient selection could further improve outcomes and minimize adverse effects.

ARX517

NCT04662580

NCT04662580 is a phase 1, multicenter, open-label trial investigating the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary antitumor activity of ARX517 in patients with mCRPC who are resistant or refractory to standard therapies. ARX517 consists of a humanized anti-PSMA monoclonal antibody (IgG1κ) linked to two proprietary microtubule-disrupting toxins (AS269). The study includes dose-escalation (phase 1a) and dose-expansion (phase 1b) stages to determine the MTD and RDDs. Eligible participants were men aged 18 or older with histologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma, metastatic disease, and castration-resistant PC (serum testosterone ≤ 50 ng/dL). Patients must have received at least two prior lines of therapy, including one second-generation androgen receptor inhibitor (such as abiraterone, darolutamide, apalutamide, or enzalutamide). ARX517 is administered intravenously every three or four weeks. This study is still recruiting.

MLN2704

The structure of MLN2704 consists of a humanized mAb MLN591 targeting the external domain of PSMA, an antimicrotubule agent maytansinoid-1 (DM1), and linked by a disulfide bond[

44]. The phase 1/2 clinical trial of MLN2704 evaluated its safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor activity in patients with progressive mCRPC[

45]. Sixty-two patients were enrolled and divided into four dosing schedules: weekly (60–165 mg/m²), every 2 weeks (120–330 mg/m²), every 3 weeks (330–426 mg/m²), and a 6 week cycle (330 mg/m²).

MLN2704 demonstrated limited clinical efficacy. Only 8% of patients represented ≥50% reduction in PSA levels, and most of them were in the dose of 330mg/m2. No significant tumor regression was observed, although 35% of the patients exhibited stable disease. In addition, the major limiting factor for the utility of MLN2704 was its safety profile. Peripheral neuropathy was the most common adverse event (71%), with 10% of them experiencing severe (grade 3 or 4) neuropathy. Neurotoxicity is considered to be the instability of the disulfide linker between MLN591 and DM1. Pharmacokinetic analysis revealed rapid clearance of the conjugated antibody, while free DM1 levels persisted in circulation for up to 30 days. Levels of free DM1 were > 20-fold higher in the 2-week and 3-week groups in the dose of 330 mg/m2. This instability resulted in the premature deconjugation of DM1 in the bloodstream, leading to elevated systemic exposure to free DM1 and subsequent toxicity.

The clinical development of MLN2704 was hampered by significant neurotoxicity and limited antitumor activity. This trial indicates that linker instability substantially narrowed the therapeutic window of ADCs. Advancements in linker technology could help reduce systemic toxicity and improve the efficacy of PSMA-targeting ADCs.

MEDI3726

NCT02991911

NCT02991911 is an open-label, dose-escalation phase 1/1b clinical trial evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and preliminary efficacy of MEDI3726 in patients with mCRPC. MEDI3726 is composed of a humanized mAb J591 conjugated to pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimers via a linker[

46]. PBD dimers are potent cytotoxins that form DNA interstrand crosslinks, which are minimally disrupted by DNA repair mechanisms[

47].

The study enrolled 33 patients between February 2017 and November 2019, all with histologically confirmed mCRPC that had progressed after abiraterone, enzalutamide, and taxane-based chemotherapy. MEDI3726 was administered intravenously every three weeks at doses ranging from 0.015 to 0.3 mg/kg.

The result of this trial was published by Johann S. de Bono on

Clin Cancer Res[

48]. The median age of the 33 participants was 71 years. The MTD of MEDI3726 was not identified; however, the MAD was established at 0.3 mg/kg. Among the 33 patients, 90.9% experienced drug-related AEs, with common adverse events that included skin toxicities, effusions, and elevated liver enzymes. Grade 3/4 TRAEs were observed in 45.5% of patients, and 33.3% of patients discontinued treatment due to toxicity. Pharmacokinetics revealed nonlinear clearance and a short half-life of 0.3–1.8 days, while 40.6% of the patients developed antidrug antibodies. In an efficacy test, a 12.1% composite response rate was reported, with responses occurring in higher-dose cohorts (≥0.2 mg/kg). One patient (3%) exhibited a PSA reduction of ≥50%, and four patients (12%) achieved a confirmed CTC response in the low CTCs group (≤50 CTC/7.5 mL blood). The median PFS was 3.6 months, and the OS was 8.9 months. This trial demonstrated a relatively limited activity of MEDI3726.

Discussion

ADCs have emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for PC, which has aroused interest in the development of PSMA-targeting therapy. PSMA is a critical diagnostic and therapeutic target due to its selective expression in PC cells, particularly in the advanced and metastatic stages. Its overexpression provides a unique opportunity for precise delivery of cytotoxic agents, maximizing antitumor efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity. Several researchers have invested in the development and clinical trials of PSMA-targeting ADCs for mCRPC. Despite notable progress, challenges related to efficacy and safety remain significant barriers to their clinical adoption.

PSMA-targeting ADCs have demonstrated their ability to induce significant tumor responses. PSMA-MMAE showed promising antitumor activity in chemotherapy-naïve patients, with ≥50% PSA reductions observed in up to 21% cases and 53% of CTC conversion. This highlights its potential efficacy when administered at optimized doses (2.3 mg/kg). According to Johann S. de Bono’s article, CTC are the independent predictor for the prognosis of mCRPC, with the OS improved in conversion to favorable CTC[

49]. In this case, the OS of chemotherapy-naïve patients was observed to be 97.1% over 7 months. These results underscore the antitumor activity and ability of PSMA ADCs to improve survival.

The use of advanced payloads, such as microtubule disruptors (MMAE) and PBD dimers, further enhances the efficacy of ADCs. These payloads are designed to disrupt cell division or induce DNA damage selectively in tumor cells, and most of them could bypass the resistance mechanism associated with conventional therapies. Despite these strengths, safety concerns have been a major limitation for PSMA-targeting ADCs. PSMA-MMAE showed DLTs, including febrile neutropenia and sepsis, which necessitated dose adjustments from 2.5 mg/kg to 2.3 mg/kg. MLN2704 was associated with high rates of peripheral neuropathy (71%). Similarly, MEDI3726 faced significant toxicity challenges, with 45.5% of patients experiencing grade 3/4 TRAEs. Pharmacokinetics plays a critical role in narrowing the therapeutic window of these agents. Rapid deconjugation of MLN2704 (associated with linker instability) and the short half-life of MEDI3726 (0.3–1.8 days) increase premature payload release and systemic exposure to free cytotoxic agents, resulting in the exacerbation of adverse effects.

To improve the therapeutic potential of ADCs, several strategies should be explored. The therapeutic efficacy of ADCs is correlated with the concentration and retention time of the payload within tumor cells, and exceeding a threshold concentration is essential for tumor stasis[

50]. This requires a balance between ADC stability in circulation and efficient payload release in the tumor microenvironment. Parameters such as conjugation site, linker length, cleavage mechanism, and steric hindrance play a crucial role in optimizing linker design[

51]. A well-designed linker ensures effective payload delivery, enhancing therapeutic outcomes while minimizing systemic toxicity. Moreover, the development of payloads with lower systemic toxicity and the adjustment of dose regimens could improve patient tolerability. Modifying the physicochemical properties of the payload, particularly its polarity, can improve antibody aggregation, plasma stability, and bystander effects in ADCs[

52]. Hydrophobic payloads enhance bystander effects by readily penetrating cell membranes, while the slow diffusion of hydrophilic payloads could potentially reduce the off-target toxicity[

53]. Otherwise, selecting payloads with a small molecular weight, great tissue penetration, and short half-life is also a crucial point in ADC design.

In conclusion, while PSMA-targeting ADCs have shown promising results for treating mCRPC, their clinical utility is currently limited by safety concerns and suboptimal durability of response. Future innovations in ADC design and patient stratification will be critical to overcoming these challenges and unlocking their full potential as effective therapies for advanced PC.

Conclusions

ADCs targeting PSMA have emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). By leveraging the tumor-specific overexpression of PSMA, ADCs offer a means to deliver potent cytotoxic agents directly to PC cells while minimizing off-target toxicity. Several clinical trials have demonstrated encouraging antitumor activity, particularly in chemotherapy-naïve patients, with significant reductions in PSA levels and CTC counts. However, the clinical development of PSMA-targeting ADCs has faced challenges, including DLTs such as neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy, and systemic toxicities associated with premature payload release. The key limitations of first-generation PSMA ADCs, such as unstable linkers and high systemic toxicity, have highlighted the need for further optimization. Advances in linker chemistry, payload selection, and dosing strategies will be critical in enhancing the therapeutic window of these agents. Improved conjugation techniques that enhance ADC stability and promote controlled payload release within tumor cells could reduce adverse effects and increase efficacy. Additionally, patient stratification based on PSMA expression levels and biomarkers may improve clinical outcomes by identifying those most likely to benefit from ADC therapy. Despite the challenges, PSMA-targeting ADCs represent a significant step forward in the treatment landscape of mCRPC. Future research should focus on refining ADC design, optimizing dosing regimens, and integrating these agents with existing PC therapies such as androgen receptor inhibitors and radioligand therapies. With continued innovation and clinical validation, PSMA ADCs have the potential to become a key component of precision medicine for patients with advanced PC, offering improved survival and quality of life.

References

- Rebello, R.J.; Oing, C.; Knudsen, K.E.; Loeb, S.; Johnson, D.C.; Reiter, R.E.; Gillessen, S.; Van der Kwast, T.; Bristow, R.G. Prostate cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henríquez, I.; Roach, M., 3rd; Morgan, T.M.; Bossi, A.; Gómez, J.A.; Abuchaibe, O.; Couñago, F. Current and Emerging Therapies for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC). Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francini, E.; Gray, K.P.; Shaw, G.K.; Evan, C.P.; Hamid, A.A.; Perry, C.E.; Kantoff, P.W.; Taplin, M.E.; Sweeney, C.J. Impact of new systemic therapies on overall survival of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in a hospital-based registry. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2019, 22, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.S. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol 2004, 6 (Suppl. 10), S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perner, S.; Hofer, M.D.; Kim, R.; Shah, R.B.; Li, H.; Möller, P.; Hautmann, R.E.; Gschwend, J.E.; Kuefer, R.; Rubin, M.A. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression as a predictor of prostate cancer progression. Hum Pathol 2007, 38, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, I.M.; Ankerst, D.P.; Chi, C.; Goodman, P.J.; Tangen, C.M.; Lucia, M.S.; Feng, Z.; Parnes, H.L.; Coltman, C.A., Jr. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006, 98, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hövels, A.M.; Heesakkers, R.A.; Adang, E.M.; Jager, G.J.; Strum, S.; Hoogeveen, Y.L.; Severens, J.L.; Barentsz, J.O. The diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI in the staging of pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Radiol 2008, 63, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, D.; Williams, R.D.; Seldin, D.W.; Libertino, J.A.; Hirschhorn, M.; Dreicer, R.; Weiner, G.J.; Bushnell, D.; Gulfo, J. Radioimmunoscintigraphy with 111indium labeled CYT-356 for the detection of occult prostate cancer recurrence. J Urol 1994, 152, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, A.; Basu, S. PSMA Receptor-Based PET-CT: The Basics and Current Status in Clinical and Research Applications. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awenat, S.; Piccardo, A.; Carvoeiras, P.; Signore, G.; Giovanella, L.; Prior, J.O.; Treglia, G. Diagnostic Role of (18)F-PSMA-1007 PET/CT in Prostate Cancer Staging: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, S.; Singh, H.; Kumar, R.; Mittal, B.R. Diagnostic Accuracy of (68)Ga-PSMA PET/CT for Initial Detection in Patients With Suspected Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021, 216, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochumsen, M.R.; Bouchelouche, K. PSMA PET/CT for Primary Staging of Prostate Cancer - An Updated Overview. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 2024, 54, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, S.S. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. Rev Urol 2004, 6, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Abuzallouf, S.; Dayes, I.; Lukka, H. Baseline staging of newly diagnosed prostate cancer: a summary of the literature. J Urol 2004, 171, 2122–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fendler, W.P.; Weber, M.; Iravani, A.; Hofman, M.S.; Calais, J.; Czernin, J.; Ilhan, H.; Saad, F.; Small, E.J.; Smith, M.R.; Perez, P.M.; Hope, T.A.; Rauscher, I.; Londhe, A.; Lopez-Gitlitz, A.; Cheng, S.; Maurer, T.; Herrmann, K.; Eiber, M.; Hadaschik, B. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Ligand Positron Emission Tomography in Men with Nonmetastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 7448–7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennrich, U.; Eder, M. [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 (Pluvicto(TM)): The First FDA-Approved Radiotherapeutical for Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benešová, M.; Bauder-Wüst, U.; Schäfer, M.; Klika, K.D.; Mier, W.; Haberkorn, U.; Kopka, K.; Eder, M. Linker Modification Strategies To Control the Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)-Targeting and Pharmacokinetic Properties of DOTA-Conjugated PSMA Inhibitors. J Med Chem 2016, 59, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Hetzheim, H.; Kratochwil, C.; Benesova, M.; Eder, M.; Neels, O.C.; Eisenhut, M.; Kübler, W.; Holland-Letz, T.; Giesel, F.L.; Mier, W.; Kopka, K.; Haberkorn, U. The Theranostic PSMA Ligand PSMA-617 in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer by PET/CT: Biodistribution in Humans, Radiation Dosimetry, and First Evaluation of Tumor Lesions. J Nucl Med 2015, 56, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alati, S.; Singh, R.; Pomper, M.G.; Rowe, S.P.; Banerjee, S.R. Preclinical Development in Radiopharmaceutical Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Semin Nucl Med 2023, 53, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, R.; Chakraborty, S. A review of advances in the last decade on targeted cancer therapy using (177)Lu: focusing on (177)Lu produced by the direct neutron activation route. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021, 11, 443–475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Prostate Cancer, Version 4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2024, 33.

- Hofman, M.S.; Emmett, L.; Sandhu, S.; Iravani, A.; Joshua, A.M.; Goh, J.C.; Pattison, D.A.; Tan, T.H.; Kirkwood, I.D.; Ng, S.; Francis, R.J.; Gedye, C.; Rutherford, N.K.; Weickhardt, A.; Scott, A.M.; Lee, S.T.; Kwan, E.M.; Azad, A.A.; Ramdave, S.; Redfern, A.D.; Macdonald, W.; Guminski, A.; Hsiao, E.; Chua, W.; Lin, P.; Zhang, A.Y.; McJannett, M.M.; Stockler, M.R.; Violet, J.A.; Williams, S.G.; Martin, A.J.; Davis, I.D. [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wambeke, S.; Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Gyawali, B. Controlling the Control Arm in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Trials: Best Standard of Care or the Minimum Standard of Care? J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 1518–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, P.M.; Rabuka, D. Recent Developments in ADC Technology: Preclinical Studies Signal Future Clinical Trends. BioDrugs 2017, 31, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogia, P.; Ashraf, H.; Bhasin, S.; Xu, Y. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: A Review of Approved Drugs and Their Clinical Level of Evidence. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, C.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Luo, H.L.; Sung, W.W. Antibody-drug conjugates targeting HER2 for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma: potential therapies for HER2-positive urothelial carcinoma. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1326296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayama, A.; Ellisen, L.W.; Chabner, B.; Bardia, A. Antibody-Drug Conjugates for the Treatment of Solid Tumors: Clinical Experience and Latest Developments. Target Oncol 2017, 12, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Smith, S.W.; Ghone, S.; Tomczuk, B. Current ADC Linker Chemistry. Pharm Res 2015, 32, 3526–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waight, A.B.; Bargsten, K.; Doronina, S.; Steinmetz, M.O.; Sussman, D.; Prota, A.E. Structural Basis of Microtubule Destabilization by Potent Auristatin Anti-Mitotics. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, W.; Matsui, S.; Yin, M.B.; Burhans, W.C.; Minderman, H.; Rustum, Y.M. Topoisomerase-I inhibitor SN-38 can induce DNA damage and chromosomal aberrations independent from DNA synthesis. Anticancer Res 1998, 18, 3499–3505. [Google Scholar]

- Miyahira, A.K.; Pienta, K.J.; Morris, M.J.; Bander, N.H.; Baum, R.P.; Fendler, W.P.; Goeckeler, W.; Gorin, M.A.; Hennekes, H.; Pomper, M.G.; Sartor, O.; Tagawa, S.T.; Williams, S.; Soule, H.R. Meeting report from the Prostate Cancer Foundation PSMA-directed radionuclide scientific working group. Prostate 2018, 78, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittrup, K.D.; Thurber, G.M.; Schmidt, M.M.; Rhoden, J.J. Practical theoretic guidance for the design of tumor-targeting agents. Methods Enzymol 2012, 503, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.M.; Tannock, I.F. The distribution of the therapeutic monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and trastuzumab within solid tumors. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troyer, J.K.; Feng, Q.; Beckett, M.L.; Wright, G.L., Jr. Biochemical characterization and mapping of the 7E11-C5.3 epitope of the prostate-specific membrane antigen. Urol Oncol 1995, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barren, R.J., 3rd; Holmes, E.H.; Boynton, A.L.; Misrock, S.L.; Murphy, G.P. Monoclonal antibody 7E11.C5 staining of viable LNCaP cells. Prostate 1997, 30, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius, H.; Hu, L. Targeted prodrug approaches for hormone refractory prostate cancer. Med Res Rev 2015, 35, 554–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagawa, S.T.; Thomas, C.; Sartor, A.O.; Sun, M.; Stangl-Kremser, J.; Bissassar, M.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Huicochea Castellanos, S.; Nauseef, J.T.; Sternberg, C.N.; Molina, A.; Ballman, K.; Nanus, D.M.; Osborne, J.R.; Bander, N.H. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen-Targeting Alpha Emitter via Antibody Delivery for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of (225)Ac-J591. J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.P.; Divilov, V.; Bander, N.H.; Smith-Jones, P.M.; Larson, S.M.; Lewis, J.S. 89Zr-DFO-J591 for immunoPET of prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in vivo. J Nucl Med 2010, 51, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nováková, Z.; Foss, C.A.; Copeland, B.T.; Morath, V.; Baranová, P.; Havlínová, B.; Skerra, A.; Pomper, M.G.; Barinka, C. Novel Monoclonal Antibodies Recognizing Human Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) as Research and Theranostic Tools. Prostate 2017, 77, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.R.; Kumar, V.; Lisok, A.; Plyku, D.; Nováková, Z.; Brummet, M.; Wharram, B.; Barinka, C.; Hobbs, R.; Pomper, M.G. Evaluation of (111)In-DOTA-5D3, a Surrogate SPECT Imaging Agent for Radioimmunotherapy of Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen. J Nucl Med 2019, 60, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrylak, D.P.; Kantoff, P.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Mega, A.; Fleming, M.T.; Stephenson, J.J., Jr.; Frank, R.; Shore, N.D.; Dreicer, R.; McClay, E.F.; Berry, W.R.; Agarwal, M.; DiPippo, V.A.; Rotshteyn, Y.; Stambler, N.; Olson, W.C.; Morris, S.A.; Israel, R.J. Phase 1 study of PSMA ADC, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen, in chemotherapy-refractory prostate cancer. Prostate 2019, 79, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrylak, D.P.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Chatta, K.; Fleming, M.T.; Smith, D.C.; Appleman, L.J.; Hussain, A.; Modiano, M.; Singh, P.; Tagawa, S.T.; Gore, I.; McClay, E.F.; Mega, A.E.; Sartor, A.O.; Somer, B.; Wadlow, R.; Shore, N.D.; Olson, W.C.; Stambler, N.; DiPippo, V.A.; Israel, R.J. PSMA ADC monotherapy in patients with progressive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer following abiraterone and/or enzalutamide: Efficacy and safety in open-label single-arm phase 2 study. Prostate 2020, 80, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehn, C.; Jocham, D. Technology evaluation: MLN-591, Cornell University/BZL Biologics/ImmunoGen/Millennium. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2002, 4, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Milowsky, M.I.; Galsky, M.D.; Morris, M.J.; Crona, D.J.; George, D.J.; Dreicer, R.; Tse, K.; Petruck, J.; Webb, I.J.; Bander, N.H.; Nanus, D.M.; Scher, H.I. Phase 1/2 multiple ascending dose trial of the prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted antibody drug conjugate MLN2704 in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 2016, 34, 530.e15–530.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Zammarchi, F.; Williams, D.G.; Havenith, C.E.G.; Monks, N.R.; Tyrer, P.; D'Hooge, F.; Fleming, R.; Vashisht, K.; Dimasi, N.; Bertelli, F.; Corbett, S.; Adams, L.; Reinert, H.W.; Dissanayake, S.; Britten, C.E.; King, W.; Dacosta, K.; Tammali, R.; Schifferli, K.; Strout, P.; Korade, M., 3rd; Masson Hinrichs, M.J.; Chivers, S.; Corey, E.; Liu, H.; Kim, S.; Bander, N.H.; Howard, P.W.; Hartley, J.A.; Coats, S.; Tice, D.A.; Herbst, R.; van Berkel, P.H. Antitumor Activity of MEDI3726 (ADCT-401), a Pyrrolobenzodiazepine Antibody-Drug Conjugate Targeting PSMA, in Preclinical Models of Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2018, 17, 2176–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adair, J.R.; Howard, P.W.; Hartley, J.A.; Williams, D.G.; Chester, K.A. Antibody-drug conjugates - a perfect synergy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2012, 12, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.S.; Fleming, M.T.; Wang, J.S.; Cathomas, R.; Miralles, M.S.; Bothos, J.; Hinrichs, M.J.; Zhang, Q.; He, P.; Williams, M.; Rosenbaum, A.I.; Liang, M.; Vashisht, K.; Cho, S.; Martinez, P.; Petrylak, D.P. Phase I Study of MEDI3726: A Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen-Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugate, in Patients with mCRPC after Failure of Abiraterone or Enzalutamide. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 3602–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bono, J.S.; Scher, H.I.; Montgomery, R.B.; Parker, C.; Miller, M.C.; Tissing, H.; Doyle, G.V.; Terstappen, L.W.; Pienta, K.J.; Raghavan, D. Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14, 6302–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yu, S.F.; Khojasteh, S.C.; Ma, Y.; Pillow, T.H.; Sadowsky, J.D.; Su, D.; Kozak, K.R.; Xu, K.; Polson, A.G.; Dragovich, P.S.; Hop, C. Intratumoral Payload Concentration Correlates with the Activity of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Mol Cancer Ther 2018, 17, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Zhang, D. Linker Design Impacts Antibody-Drug Conjugate Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy via Modulating the Stability and Payload Release Efficiency. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 687926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johann, F.; Wöll, S.; Gieseler, H. “Negative” Impact: The Role of Payload Charge in the Physicochemical Stability of Auristatin Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 113, 2433–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Gou, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in payloads. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 4025–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).