Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

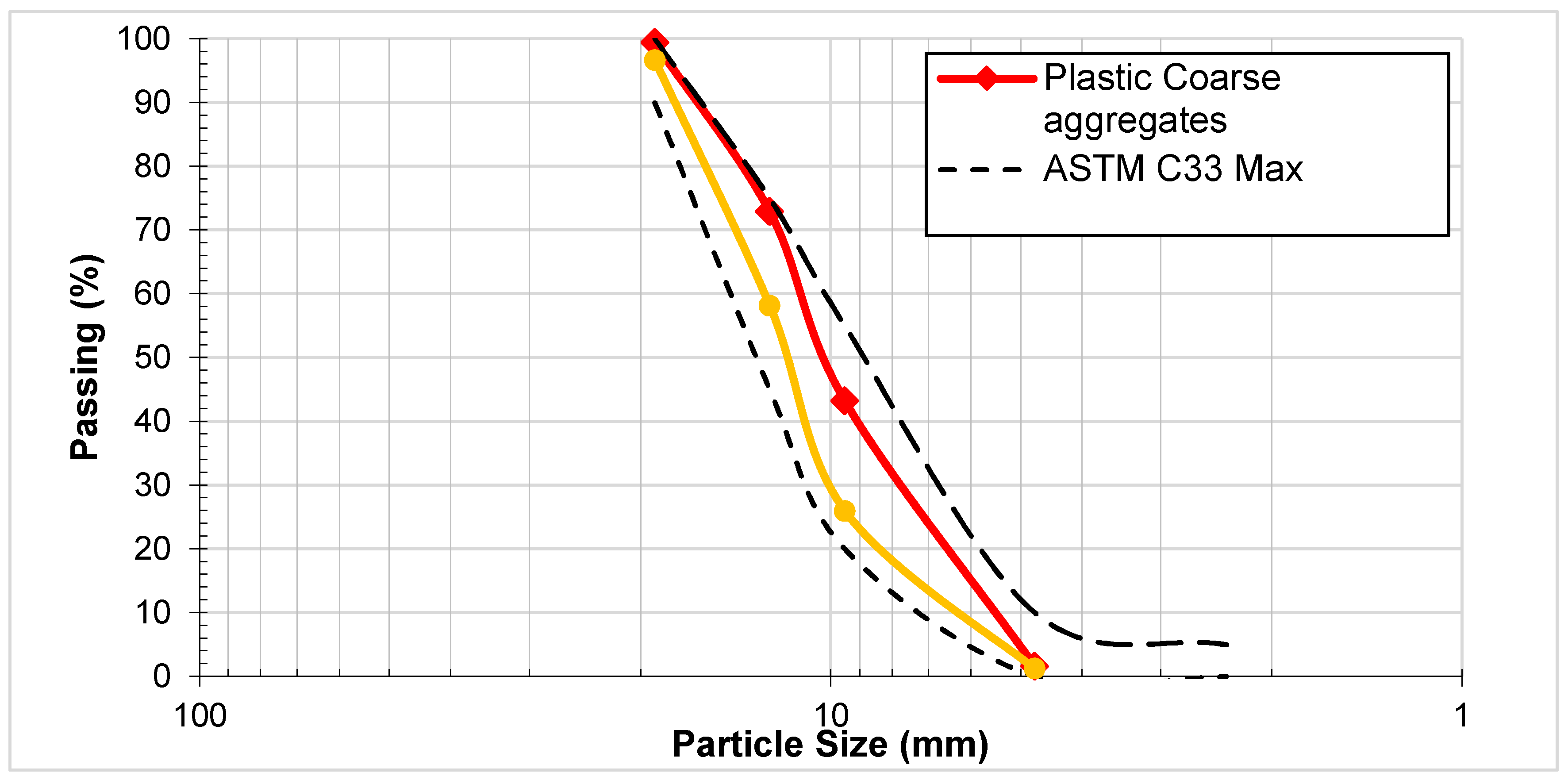

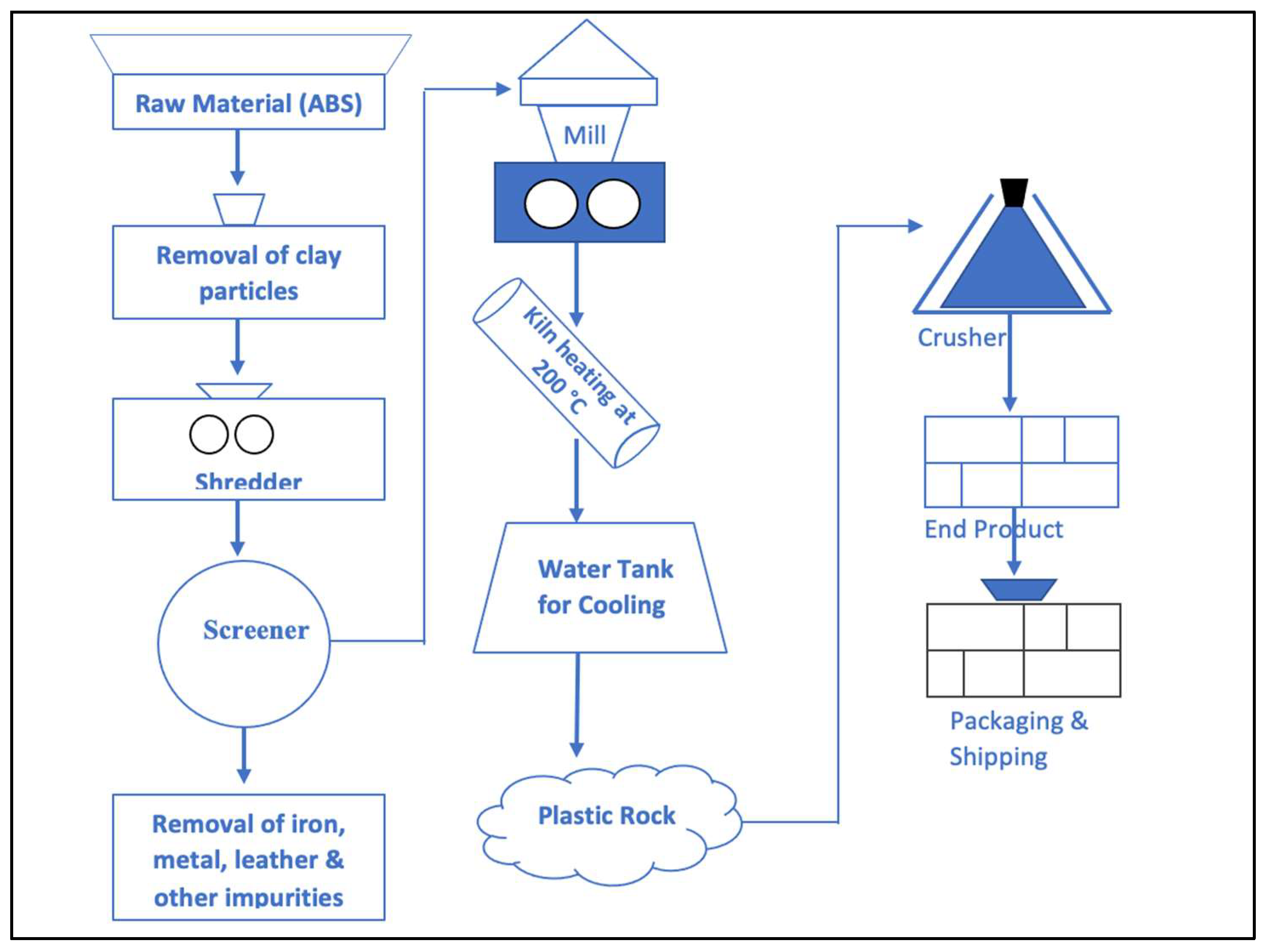

Owing to rapid urbanization and population expansion, an increase in plastic utensils leads to an increase in plastic waste. Research in the domain of the recycling and repurposing of plastic waste in the construction industry offered a solution to decrease plastic waste as relief for environmental damage and protecting natural resources. This study is about replacing natural coarse aggregate in concrete with plastic coarse aggregate (PCA), which is made from electronic waste. Natural coarse aggregates (NCA) are replaced by PCA as 10%, 15%, and 20%. Rheological and mechanical properties i.e., workability, concrete density, compressive strength, and split tensile strength are investigated. The durability of concrete is assessed by water absorption, abrasion resistance, Sorptivity, Sulphuric attack resistance, and thermal conductivity. scanning electron microscopy is performed for the confirmation of durability claims. The analysis revealed that the use of produced PCA enhances the workability of concrete; nevertheless, the compressive and tensile strengths were reduced as 18.58% and 3.7%, respectively. PCA is treated with sand and silica fumes (SF) in order to attain targeted strength. It helped to reduce the negative effects of PCA on the strength properties of the concrete. PCA is concluded as a substitute for NCA having equivalent strength with enhanced performance of concrete.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Significance

3. Material

4. Experimental Methods

5. Results & Discussion

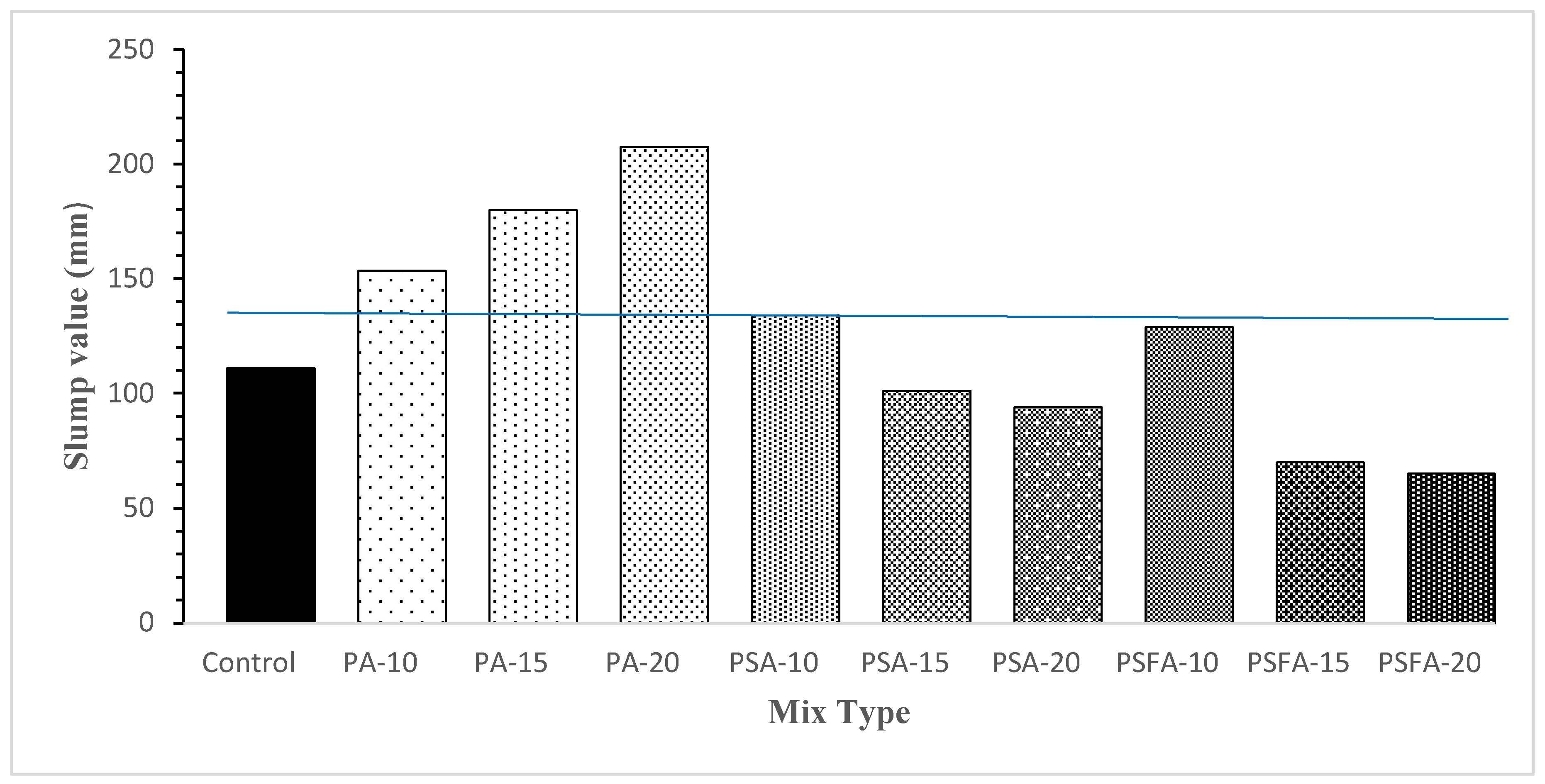

5.1. Workability

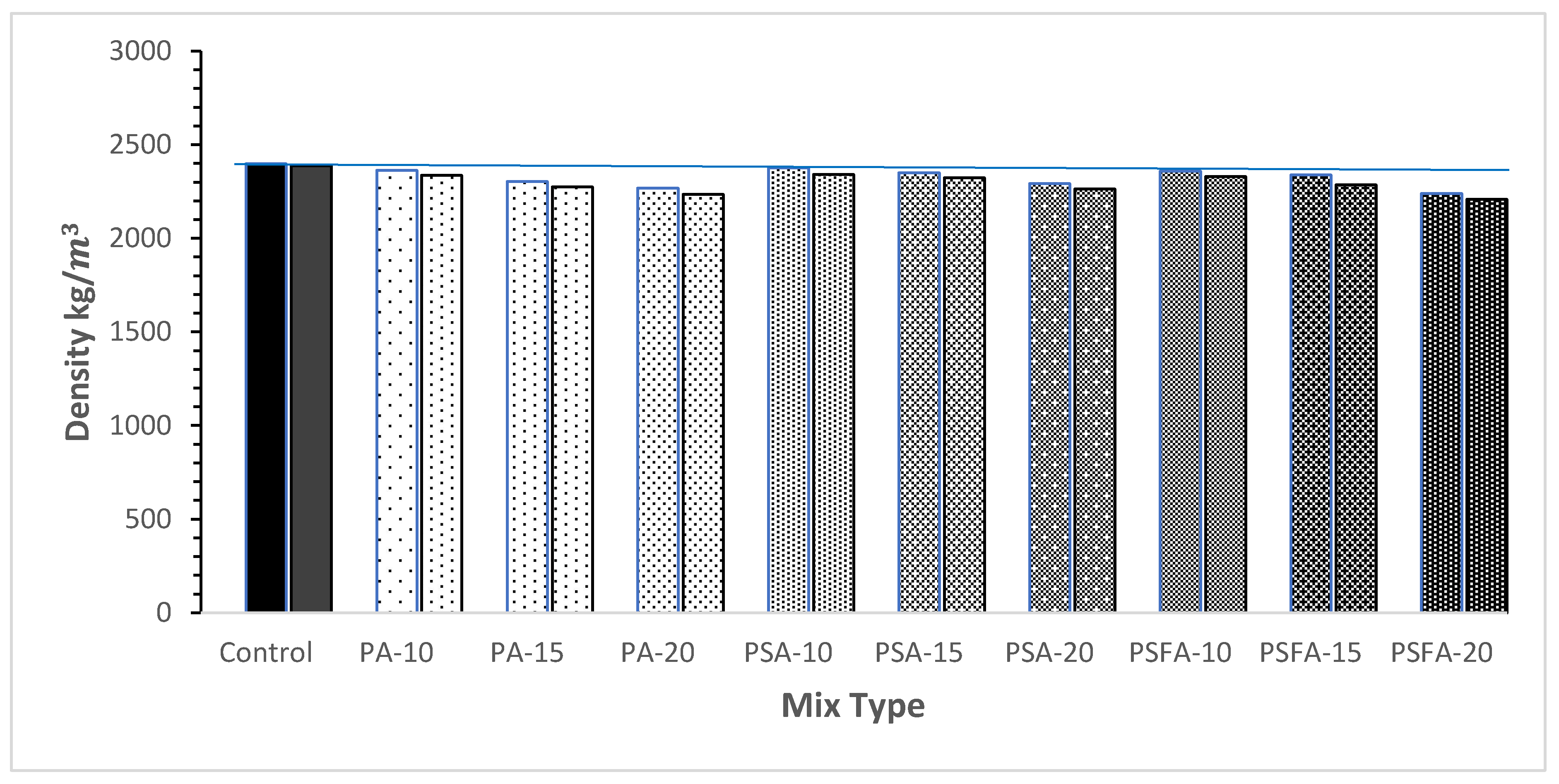

5.2. Fresh and Dry Density

5.3. Mechanical Property of Concrete

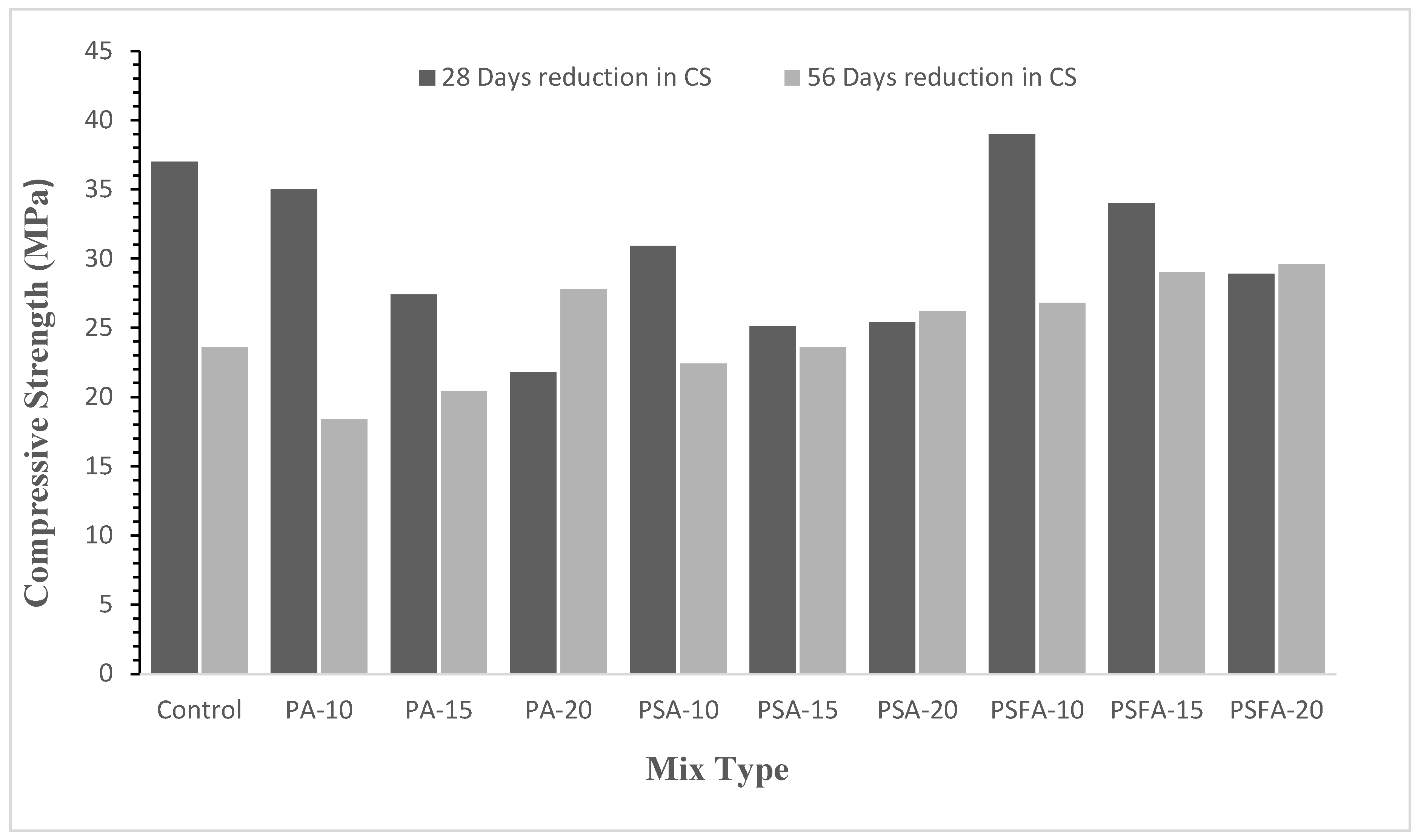

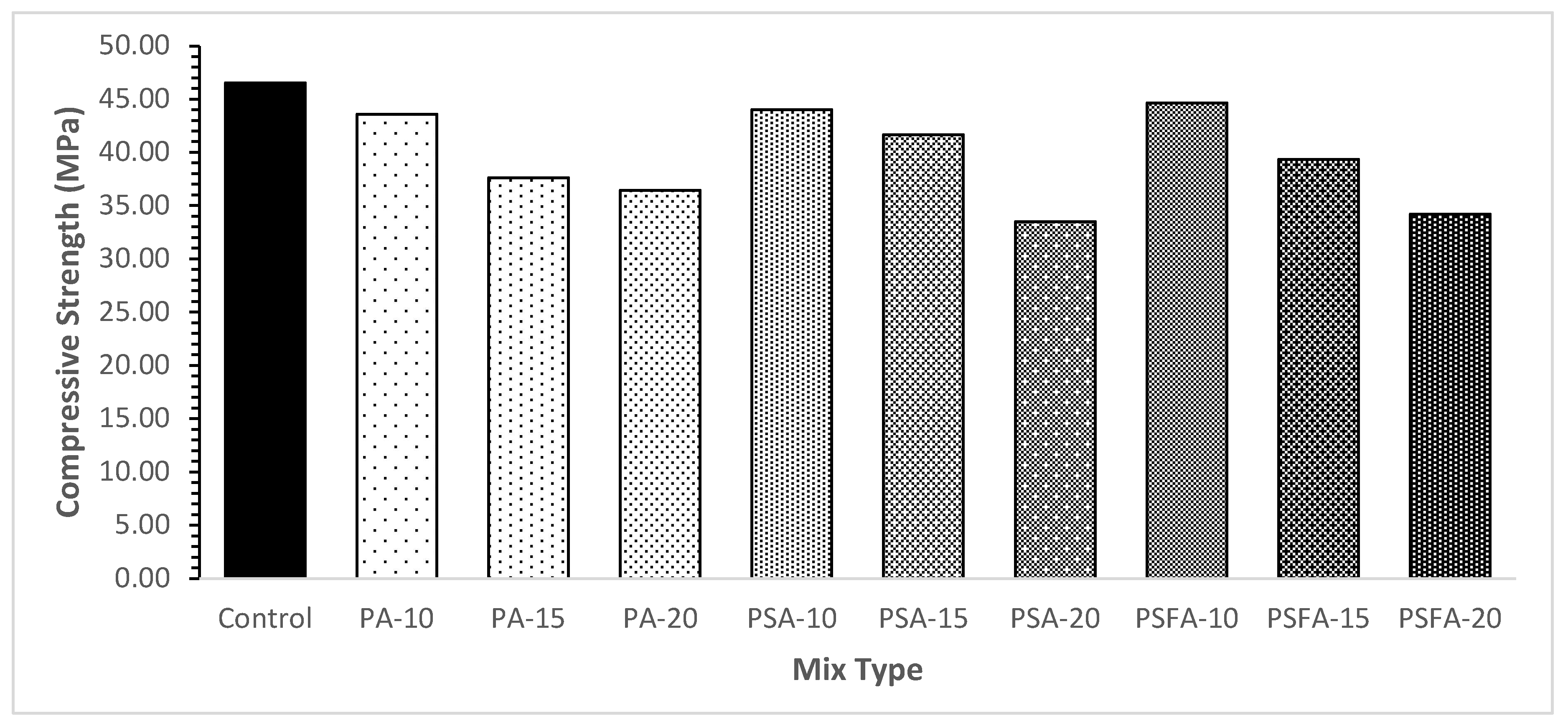

5.3.1. Compressive Strength

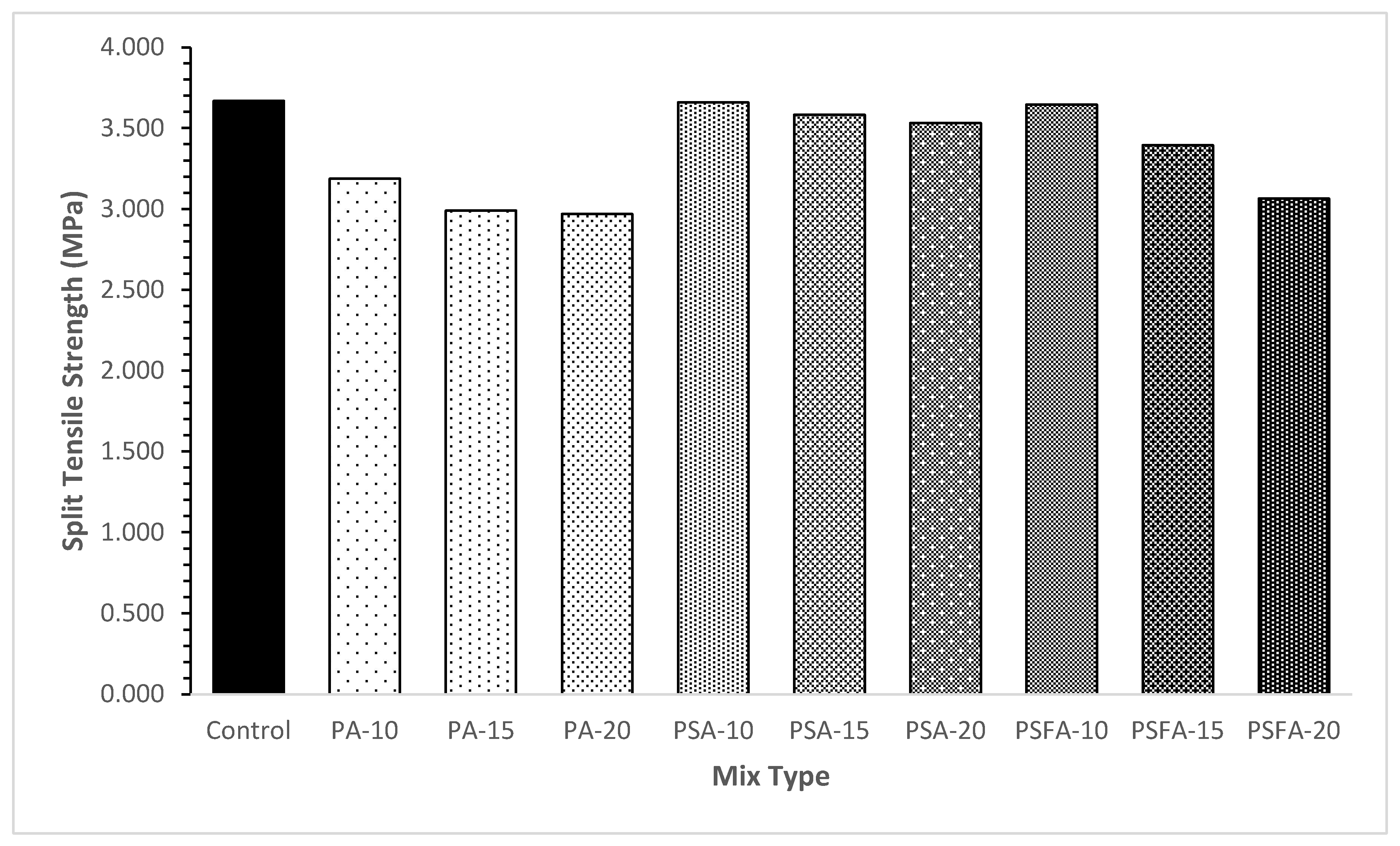

5.3.2. Split Tensile Strength

5.4. Durability Properties

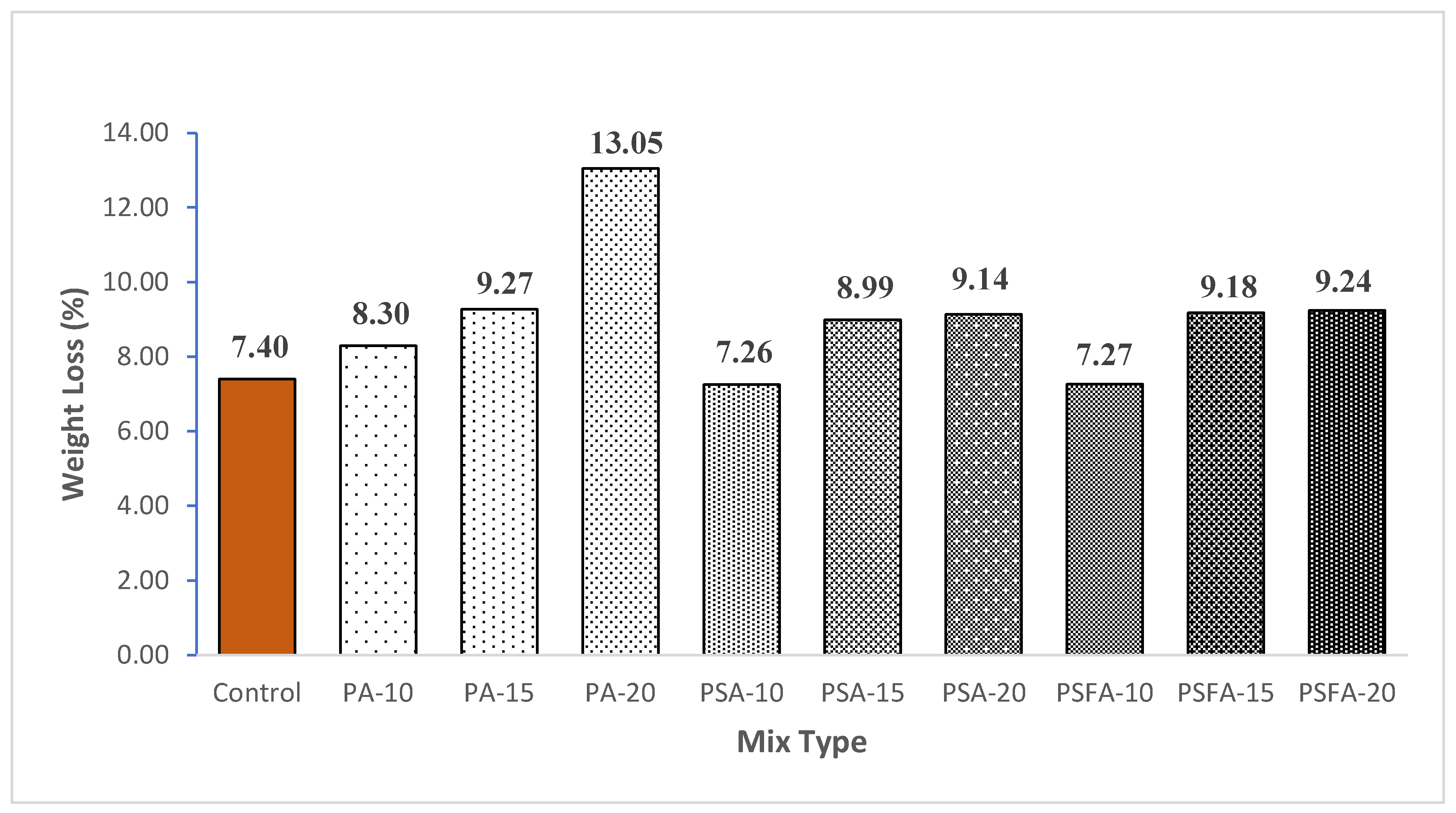

5.4.1. Abrasion Resistance

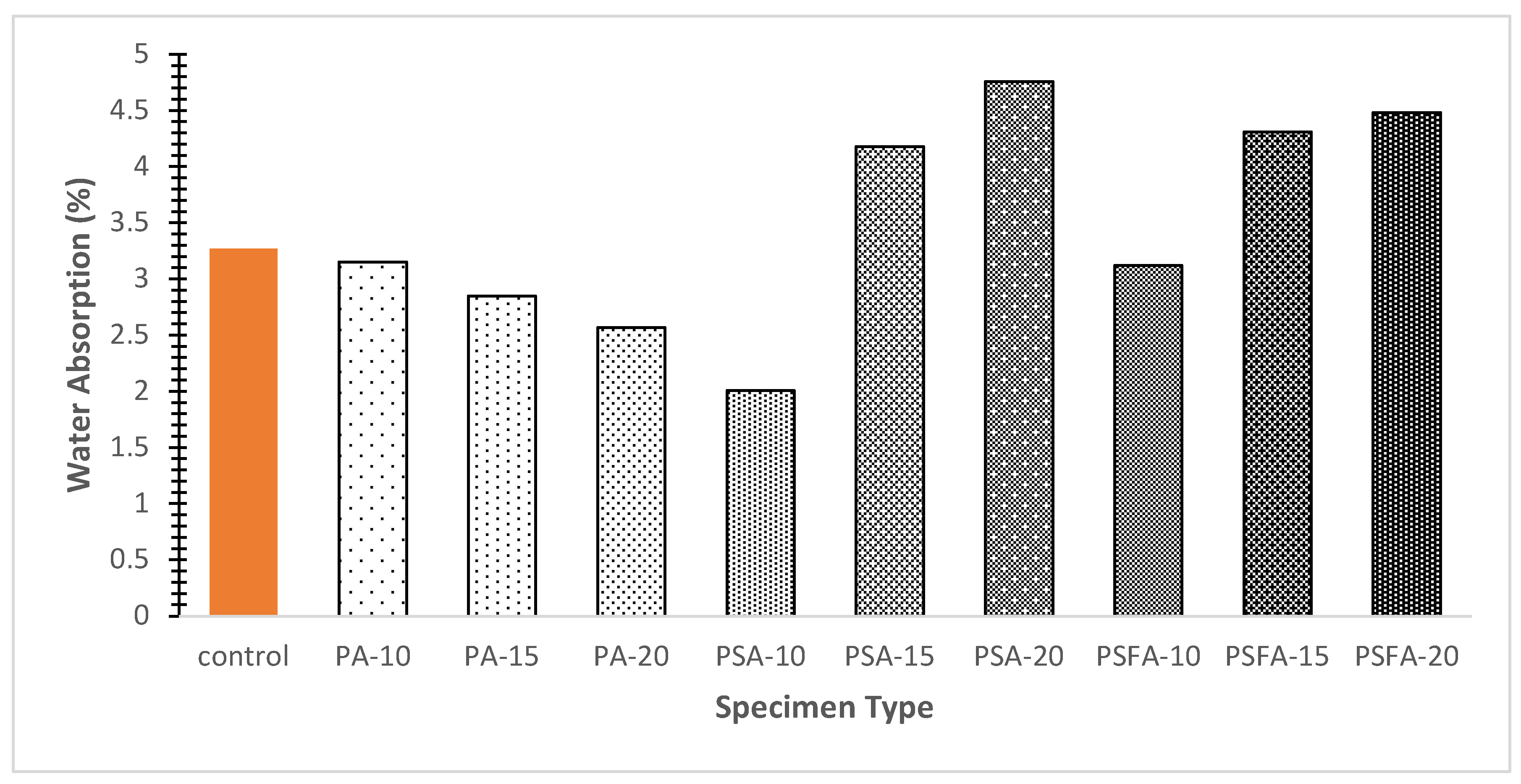

5.4.2. Water Absorption

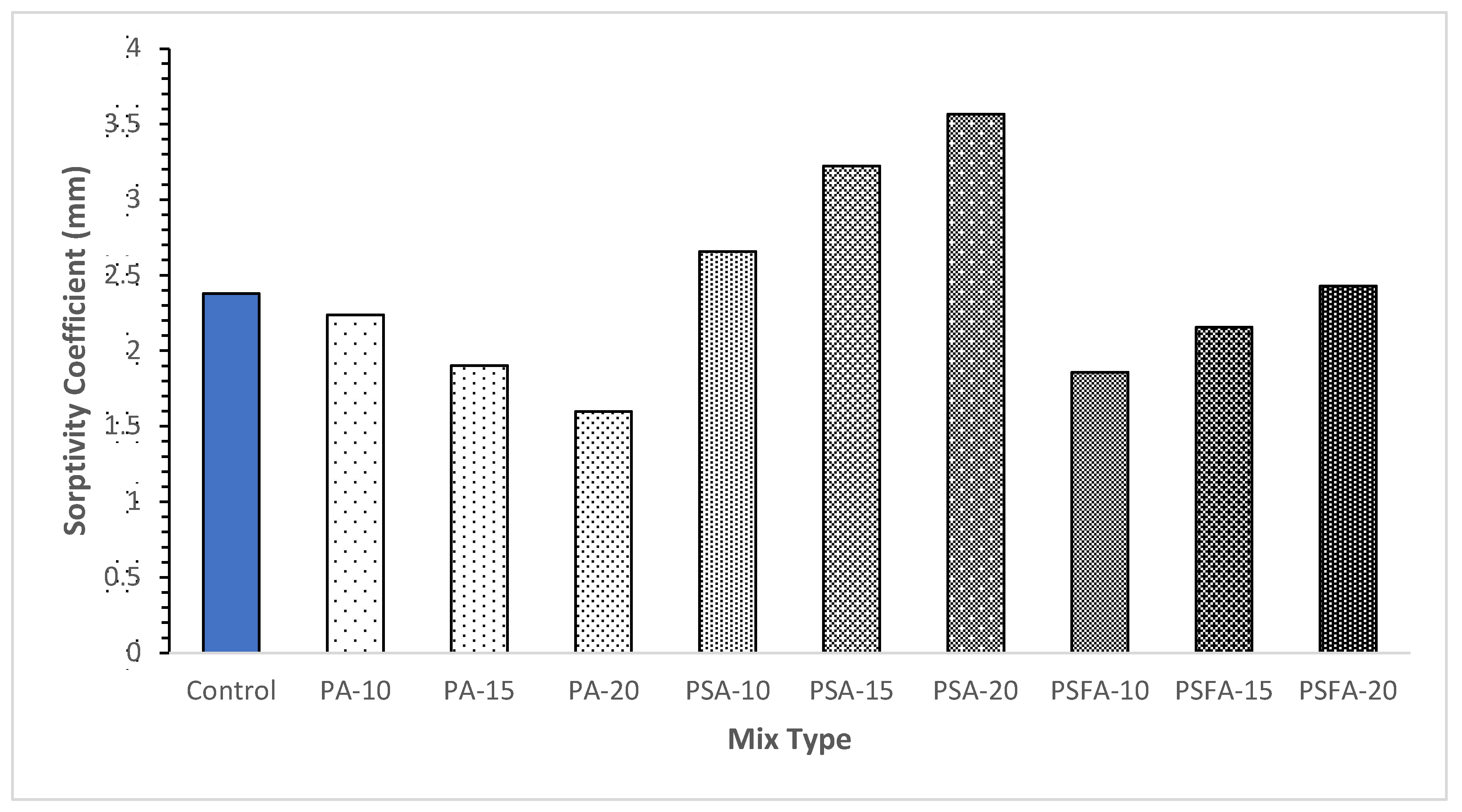

5.4.3. Sorptivity

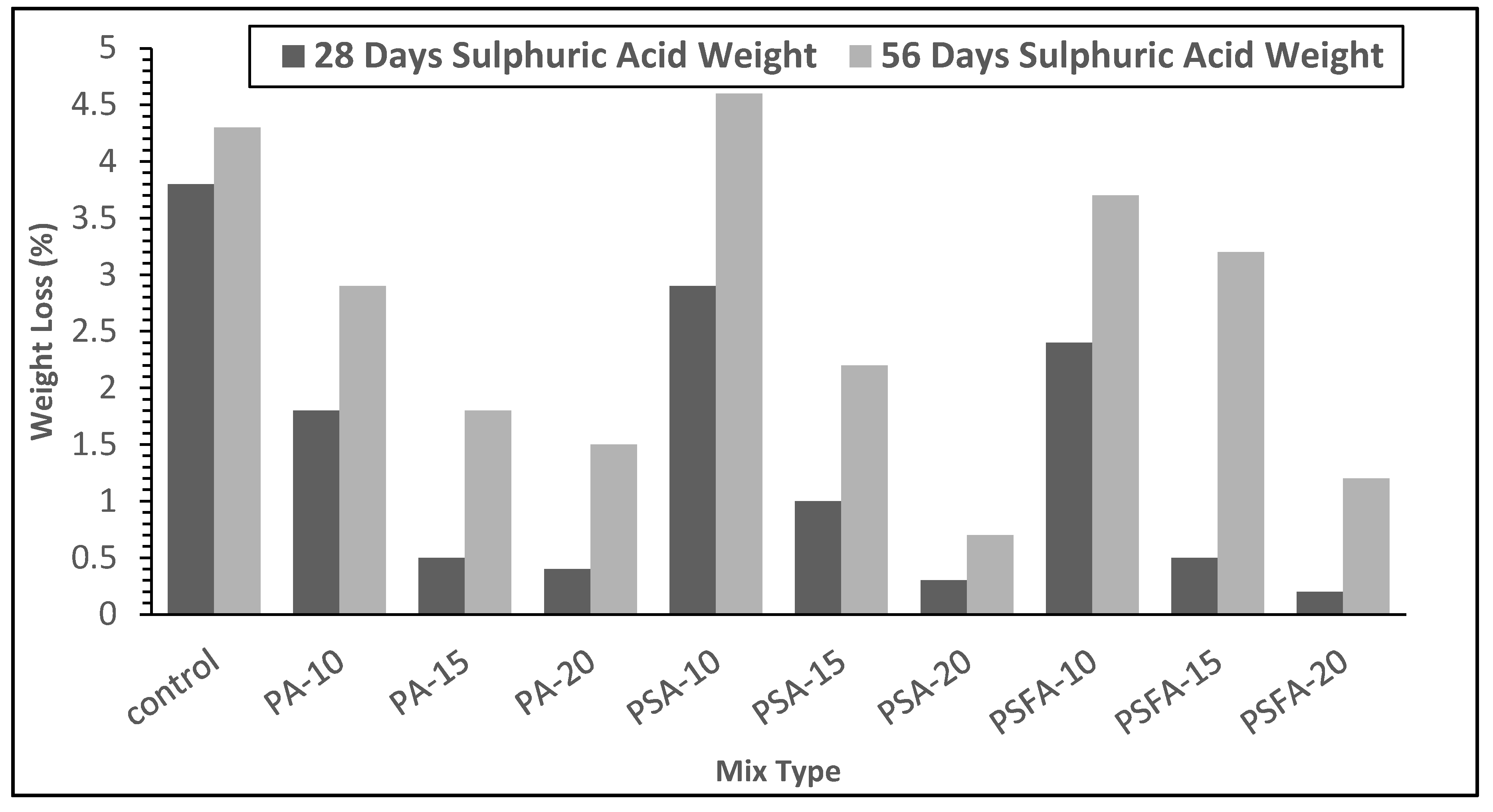

5.4.4. Sulphuric Acid Attack Resistance

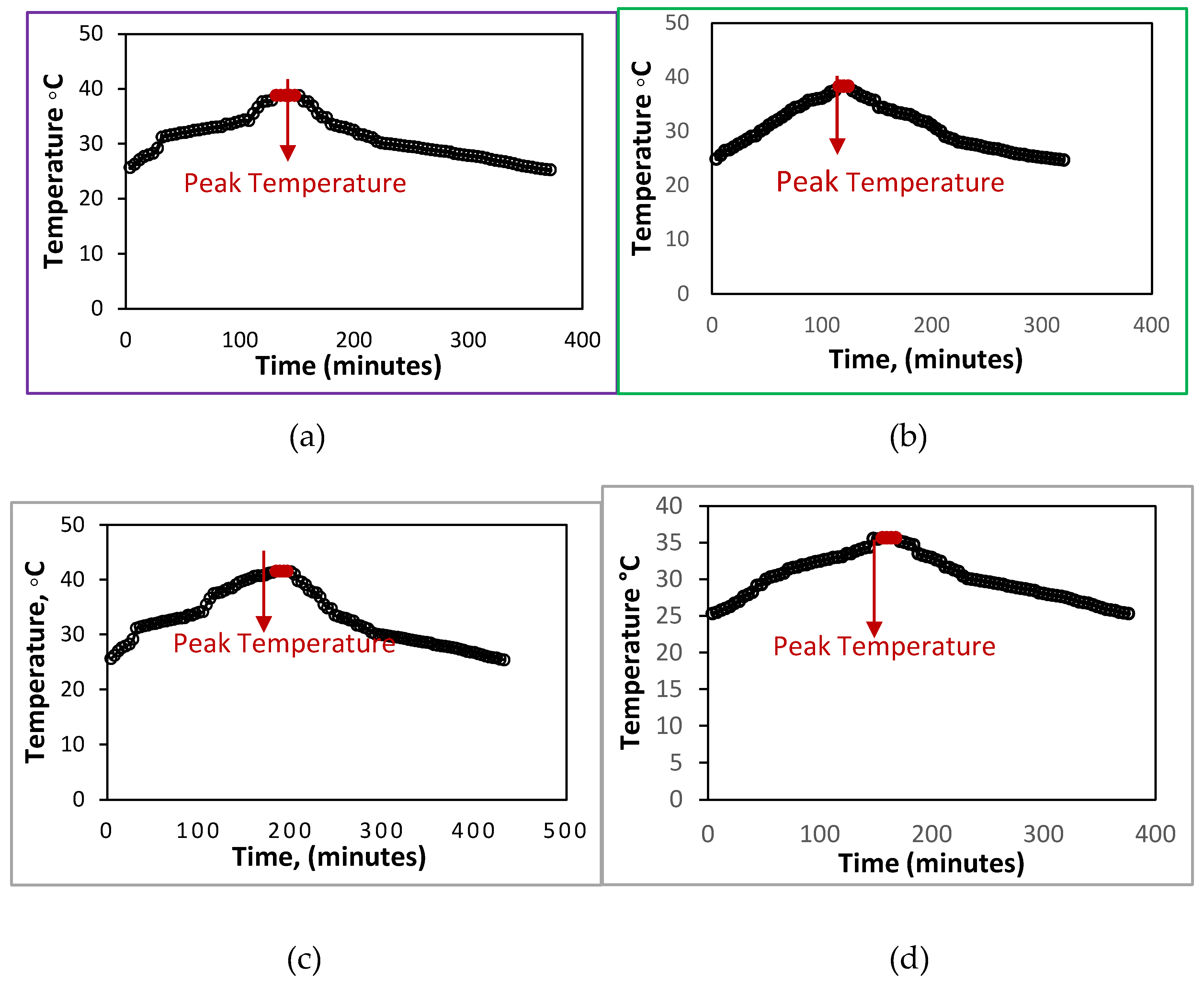

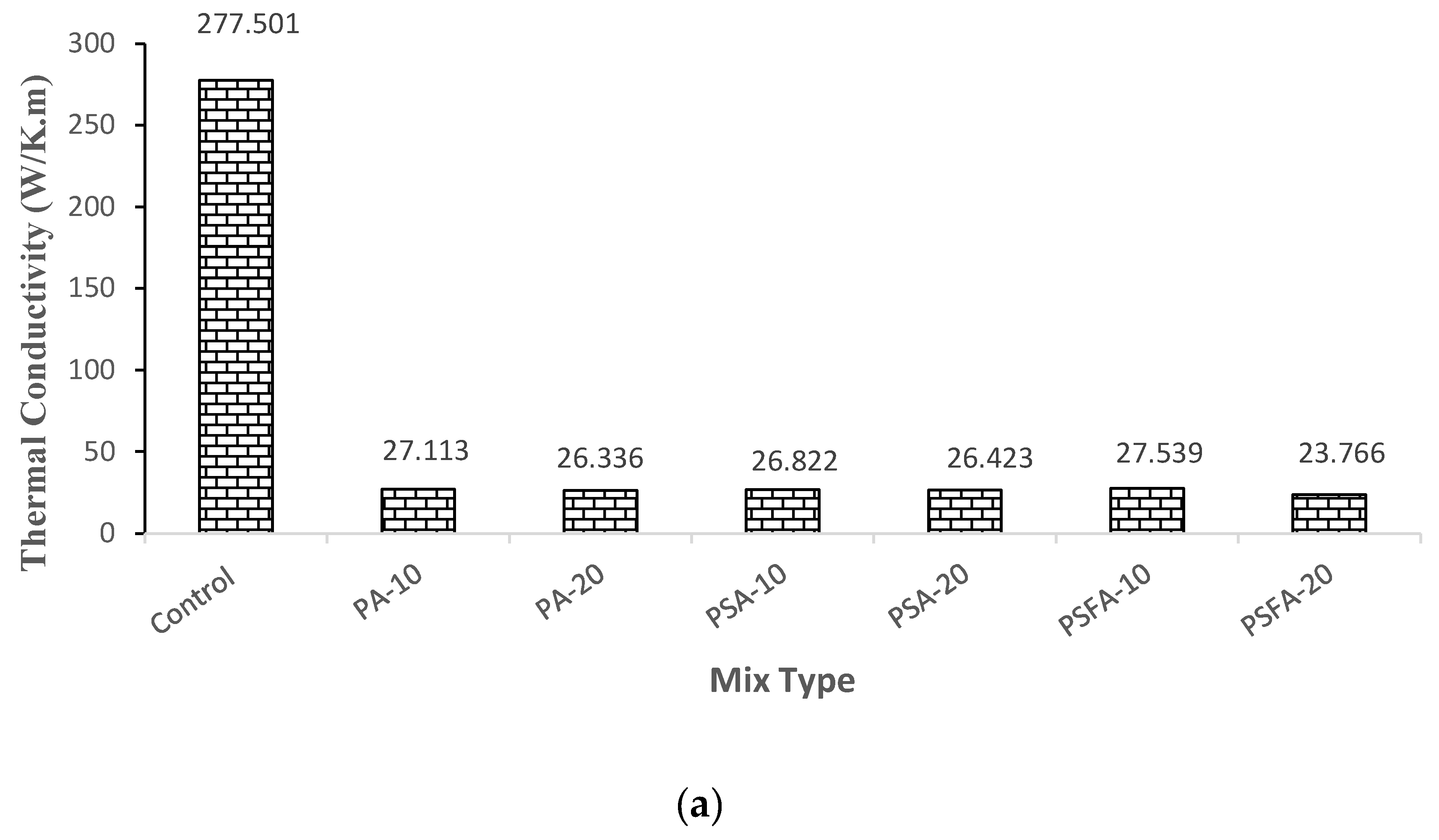

5.4.5. Thermal Performance

5.4.6. Thermal Conductivity

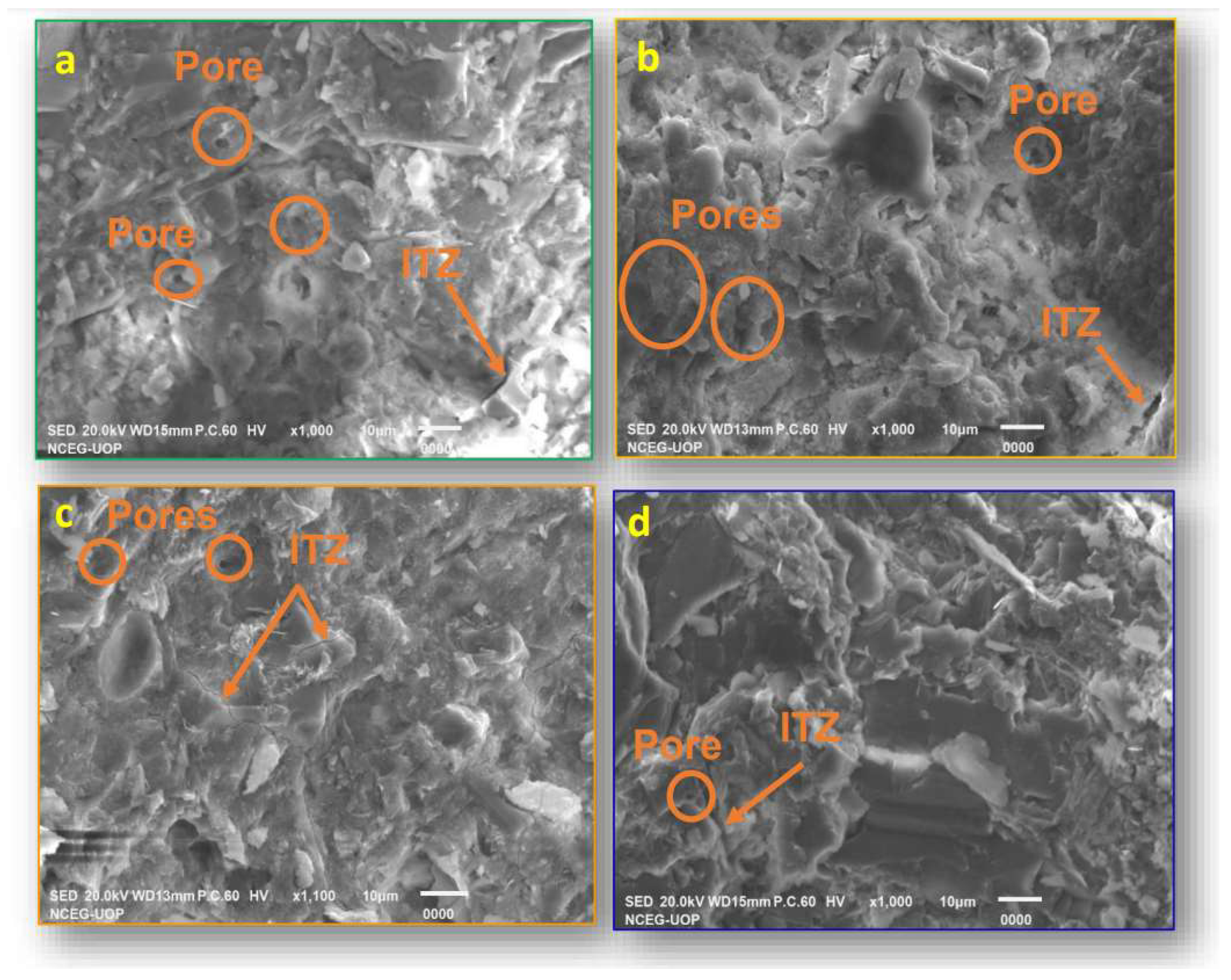

5.4.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

5.5. Conclusion & Recommendation

- The workability of concrete containing untreated E-waste recycled plastics was better than concrete containing sand-treated and silica fume treated E-waste recycled plastics. The greater workability of PA is due to zero water absorption as compared to treated PA and treated silica-fume PA. The reduced workability of treated PA and treated silica fume aggregate was related to the change from hydrophobic to hydrophilic character of recycled PA, as well as enhanced adhesion between cement paste and plastic aggregates.

- The addition of PA to concrete reduced the fresh and dry densities of concrete mixes by up to 5.4% and 7.5%, respectively.

- The compressive strength of concrete using sand-treated and silica fume treated recycled plastic aggregates was greater than that of concrete with untreated E-waste. The greater compressive strength values of concrete including sand-treated, and silica fume-treated recycled plastics E-waste were caused by a change in recycled plastic behavior from hydrophobic to hydrophilic and enhanced bonding between treated plastics and cement paste. The compressive strength values of treated PA concrete were found to be higher than those of untreated PA.

- The split tensile strength of concrete containing sand-treated and silica treated recycled plastics E-waste was greater than that of concrete containing untreated recycled plastics. E-waste. The increased split tensile strength values of concrete, comprising sand-treated and silica fume-treated recycled plastics E-waste, were the consequence of a change from hydrophobic to hydrophilic behavior of recycled plastics and enhanced bonding between sand-treated plastics and cement paste. Indoor thermal performance experiments have shown that concrete containing plastic aggregate provides greater thermal insulation by decreasing heat conductivity by about 90 percent and enhancing thermal resistance.

- Treated PA with sand and SF has more water absorption by 29.2% and 27.2% at maximum replacement ratio. The reason for the increase in water absorption was sand and SF on the surface of aggregate.

- The durability of concrete containing sand-treated and SF-treated E-waste was enhanced due to transition of PA from non-water absorbing surface to the water fill surface leaded to adhered CSH gel around the surface for more packed ITZ.

References

- P. Watson, “Blueprint for greening affordable housing,” Hous Stud, 2021, . [CrossRef]

- McGraw Hill Construction, Green Building Retrofit and Renovation. 2009.

- N. Iman, “Digital Sustainability: Paving the Way Toward a Green Economy?,” Sustainability and climate change, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 268–277, Aug. 2023, . [CrossRef]

- V. Forti, C. P. Baldé, R. Kuehr, and G. Bel, “The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, flows and the circular economy potential,” 2020.

- F. Ahmad, A. Jamal, K. M. Mazher, W. Umer, and M. Iqbal, “Performance evaluation of plastic concrete modified with e-waste plastic as a partial replacement of coarse aggregate,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 2022, . [CrossRef]

- K. Ali, M. I. Qureshi, S. Saleem, and S. U. Khan, “Effect of waste electronic plastic and silica fume on mechanical properties and thermal performance of concrete,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 285, p. 122952, 2021, . [CrossRef]

- S. N. Abbas, M. I. Qureshi, M. M. Abid, M. A. U. R. Tariq, and A. W. M. Ng, “An Investigation of Mechanical Properties of Concrete by Applying Sand Coating on Recycled High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) and Electronic-Wastes (E-Wastes) Used as a Partial Replacement of Natural Coarse Aggregates,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 4087, 2022.

- B. T. A. Manjunath, “Partial replacement of E-plastic waste as coarse-aggregate in concrete,” Procedia Environ Sci, vol. 35, pp. 731–739, 2016.

- R. Saxena, S. Siddique, T. Gupta, R. K. Sharma, and S. Chaudhary, “Impact resistance and energy absorption capacity of concrete containing plastic waste,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 176, pp. 415–421, 2018.

- Prof. C. S. Bari, “Coal Bottom Ash as A Partial Replacement with Fine Aggregate in Concrete,” INTERANTIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT, vol. 07, no. 07, 2023, . [CrossRef]

- A. Shiuly, T. Hazra, D. Sau, and D. Maji, “Performance and optimisation study of waste plastic aggregate based sustainable concrete – A machine learning approach,” Cleaner Waste Systems, vol. 2, 2022, . [CrossRef]

- A. B. Nyakuma and T. J. P. Ivase, “Emerging trends in sustainable treatment and valorisation technologies for plastic wastes in Nigeria: A concise review,” Environ Prog Sustain Energy, vol. 40, no. 5, 2021, . [CrossRef]

- K. Senthil Kumar and K. Baskar, “Recycling of E-plastic waste as a construction material in developing countries,” J Mater Cycles Waste Manag, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 718–724, 2015.

- ASTM C150/C150M, “Astm C 150,” ASTM C 150/ C150M-15 Standard specification for portland cement, vol. i, pp. 1–9, 2019, . [CrossRef]

- ASTM. C33, “ASTM c33-c33m-08 Standard Specification for concrete agg.”.

- D. S. Premathilake, A. B. Botelho Junior, J. A. S. Tenório, D. C. R. Espinosa, and M. Vaccari, “Designing of a Decentralized Pretreatment Line for EOL-LIBs Based on Recent Literature of LIB Recycling for Black Mass,” Metals, vol. 13, no. 2. MDPI, Feb. 01, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, A. Leśniak, P. Ochab, M. Górka, W. Kokoszka, and A. Sikora, “Interlaboratory comparative tests in ready-mixed concrete quality assessment,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 13, 2021, . [CrossRef]

- ASTM C143/C143M, “Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete,” Astm C143, no. 1, pp. 1–4, 2015, . [CrossRef]

- Astm:C138/C138M-13, “Standard Test Method for Density (Unit Weight), Yield, and Air Content (Gravimetric),” ASTM International, vol. i, pp. 23–26, 2013, . [CrossRef]

- “EN12390–7, Testing Hardened Concrete - Part 7: Density of Hardened Concrete, European Committee for Standardization (2019).”.

- 2014 39M, ASTM C 39/C, “ASTM C 39/C 39M – 01. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens,” pp. 3–9, 2014. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C496/C496M − 17, “Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens ASTM C-496,” ASTM International, no. March 1996, pp. 1–5, 2011.

- ASTM, “Standard Method of Test for obtaining and testing drilled cores and sawed beams of concrete,” Standard Specifications for Transportation Materials and Methods of Sampling and Testing, vol. 23, no. 11, pp. 2841–2852, 2018, . [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1585-13, “Standard Test Method for Measurement of Rate of Absorption of Water by Hydraulic Cement Concretes,” ASTM International, vol. 41, no. 147, pp. 1–6, 2013.

- ASTM C131/C131M-14, “C131/C131M-14 Standard Test Method for Resistance to Degradation of Small-Size Coarse Aggregate by Abrasion and Impact in the Los Angeles Machine,” Annual Book of American Society for Testing materials ASTM Standards,West Conshohocken, USA, vol. 04, no. Note 2, pp. 5–8, 2014, . [CrossRef]

- F. Ahmad, A. Jamal, K. M. Mazher, W. Umer, and M. Iqbal, “Performance evaluation of plastic concrete modified with e-waste plastic as a partial replacement of coarse aggregate,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 175, 2021.

- H. Purnomo, G. Pamudji, and M. Satim, “Influence of uncoated and coated plastic waste coarse aggregates to concrete compressive strength,” in MATEC Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, 2017, p. 1016.

- Alagusankareswari, S. S. Kumar, K. B. Vignesh, and K. A. H. Niyas, “An experimental study on e-waste concrete,” Indian J Sci Technol, vol. 9, no. 2, 2016.

- M. J. Islam, M. S. Meherier, and A. K. M. R. Islam, “Effects of waste PET as coarse aggregate on the fresh and harden properties of concrete,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 125, pp. 946–951, 2016.

- Z. H. Lee, S. C. Paul, S. Y. Kong, S. Susilawati, and X. Yang, “Modification of waste aggregate PET for improving the concrete properties,” Advances in Civil Engineering, vol. 2019, 2019.

- Z. J. Grdic, G. A. T. Curcic, N. S. Ristic, and I. M. Despotovic, “Abrasion resistance of concrete micro-reinforced with polypropylene fibers,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 305–312, 2012.

- Ul Haq, A. Elahi, A. Nawaz, S. Aamir Qadeer Shah, and K. Ali, “Mechanical and durability performance of concrete mixtures incorporating bentonite, silica fume, and polypropylene fibers,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 345, no. February, p. 128223, 2022, . [CrossRef]

- ASTM C 642-97, “Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concrete, ASTM International, United States,” Annual Book of ASTM Standards, no. March, pp. 1–3, 1997.

- T. T. Nguyen, V. Picandet, P. Carre, T. Lecompte, S. Amziane, and C. Baley, “Effect of compaction on mechanical and thermal properties of hemp concrete,” European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 545–560, 2010.

| Chemical Properties | Content (%) | Physical Properties | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Specific Gravity | 3.05 | |

| 5.5 | Specific Surface | 322 | |

| 3.5 | Consistency (%) | 29 | |

| 63.47 | Initial Setting Time (min) | 102 | |

| 1.7 | Final Setting Time (min) | 235 | |

| 1.82 | |||

| 0.2 | |||

| 1 | |||

| 0.64 |

| Properties | Cement | NCA | PCA | PSA | PSFA | Plasticizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Size (mm) | 50 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | |

| Water Absorption (%) | 0.33 | - | - | - | ||

| Specific Gravity | 3.05 | 2.4 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.15 |

| Moisture Content (%) | 0.07 | |||||

| 1440 | 1522 | 563 | 617 | 535 | ||

| Morphology | Brown Liquid | |||||

| Abrasion Value (%) | 24 | |||||

| Impact Value (%) | 13 | 2 | 12 | 8% |

| Test Type | Standard | Specimen Shape | Specimen size (mm) | No. of Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slump | ASTM-C143/C143M [18] | Cone | 300×150 | 4 |

| Fresh Density | ASTM-C138/C138M [19] | Cube | 150×150 | 4 |

| Dry Density | BS EN 12390-7 [20] | Cube | 150×150 | 4 |

| Compressive Strength | ASTM-C39/C39M [21] | Cube | 150×150 | 4 |

| Split Tensile Strength | ASTM-C496 [22] | Cylinder | 300×150 | 4 |

| Water Absorption | ASTM C-642 [23] | Cube | 150×150 | 4 |

| Sorptivity | ASTM-C1585 [24] | Cylinder | 50×100 | 4 |

| Abrasion Resistance | ASTM-C131/C131 [25] | Cylinder | 300×150 | 4 |

| Sulphuric Acid Resistance | Cube | 100×100 | 4 | |

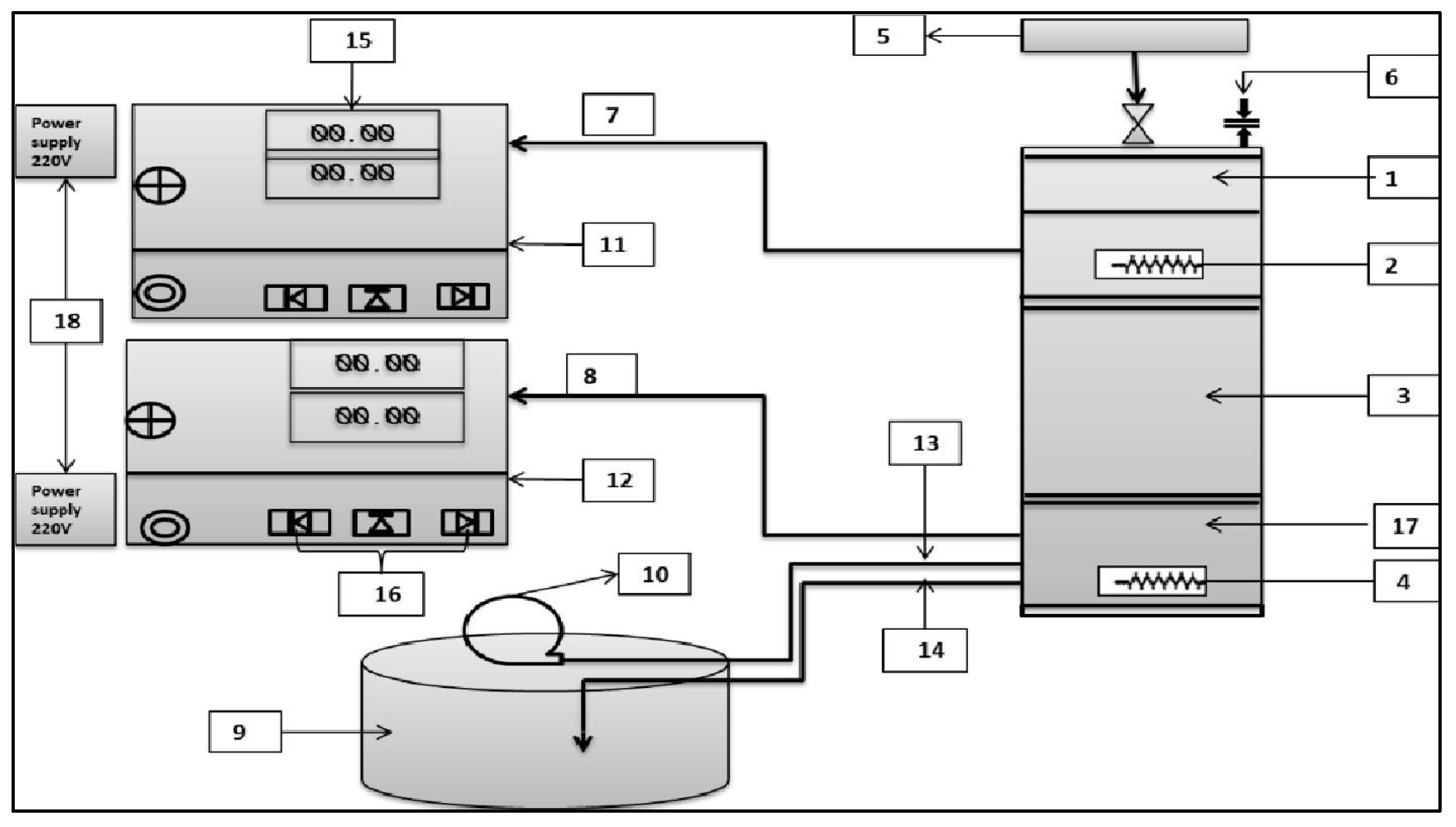

| Thermal Performance | Slab | 200×200 | 4 | |

| Thermal Conductivity | Prism | 50×50 | 4 | |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy | Chunks | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).