Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

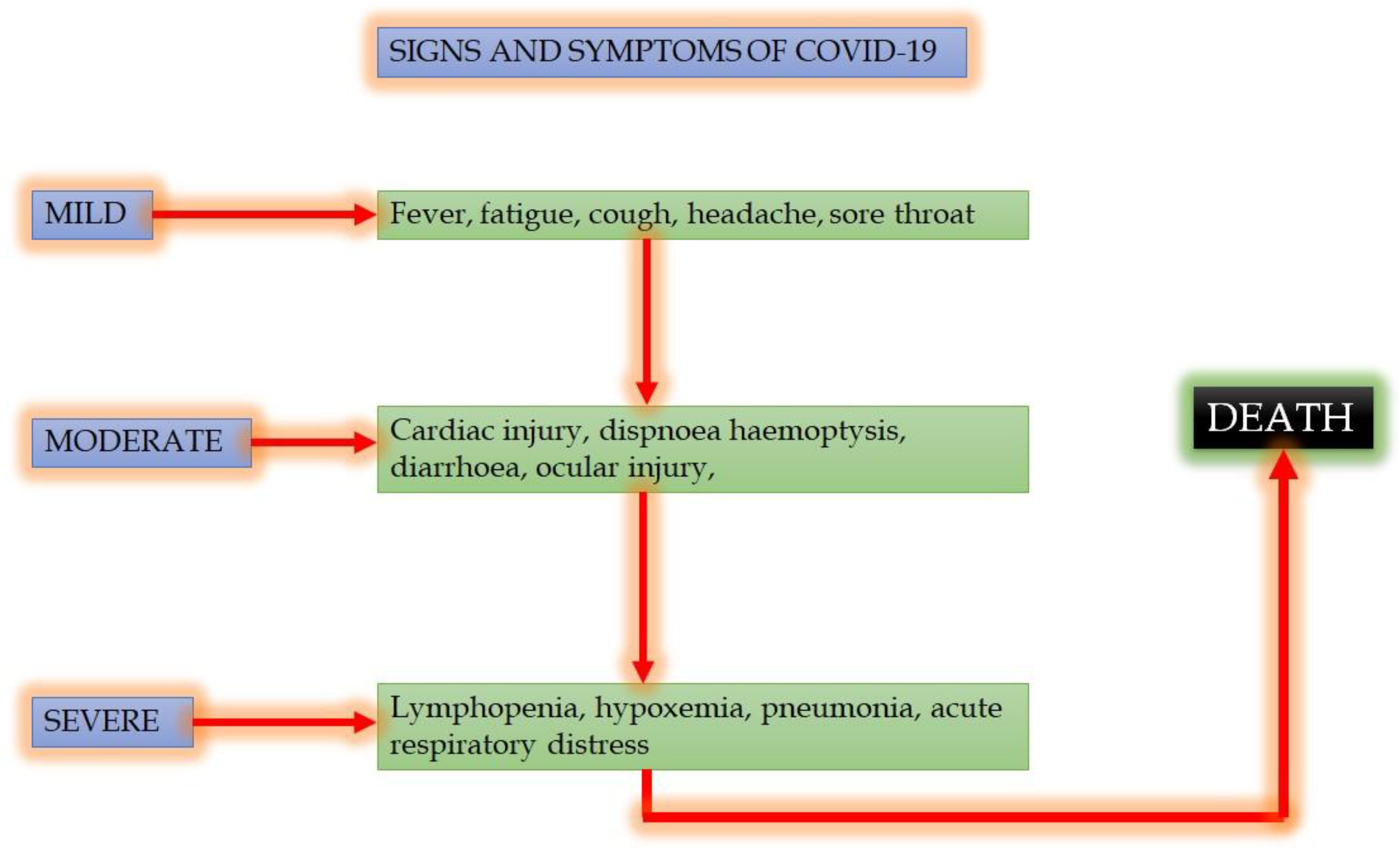

2. COVID-19: Signs and Symptoms

3. Treatment of COVID-19

4. Comorbility

4.1. Diabetes and COVID-19

4.2. Secondary Metabolites with a Potential Effect on Diabetic Patients COVID-19

4.2.1. Copper and N-Acetylcysteine

4.2.2. Quercetin

4.2.3. Houttuynia cordata

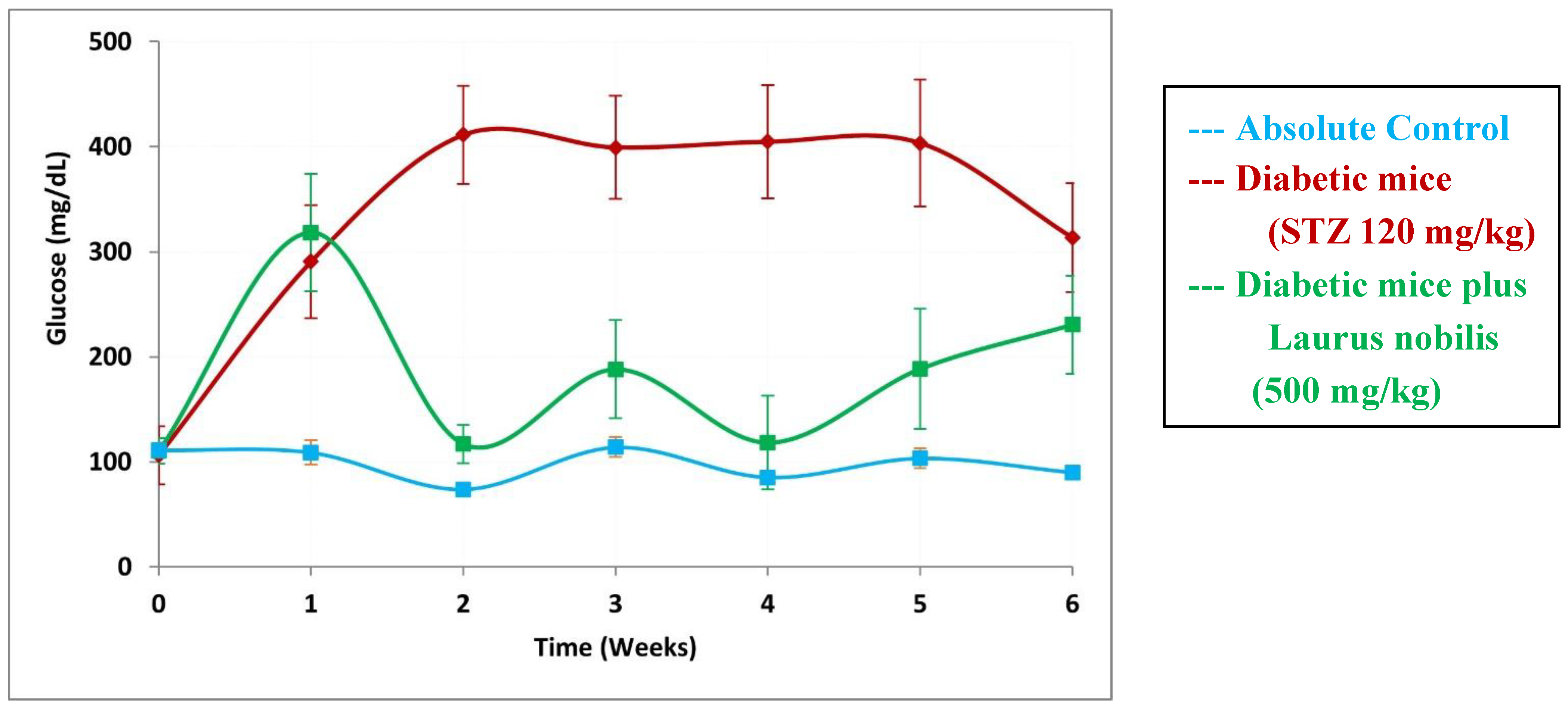

4.2.4. Laurus nobilis

4.2.5. Naringenin

4.2.6. Naringin

4.2.7. Azadirachta indica

4.2.8. Vitamin C

5. Conclusions

Perspectives

References

- World Health Organization, WHO. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report–52. March 12, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/20200312-sitrep-5 2-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn¼e2bfc9c0_2 (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- World Health Organization, WHO (2020). World experts and funders set priorities for COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/12-02-2020-world-experts-and-funders-set-priorities-for-covid-19-research (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- Tian, S.; Hu, N.; Lou, J.; Chen, K.; Kang, X.; Xiang, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Liu, N.; Liu, D.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Lian, H.; Niu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J. Infection 2020, 80, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijing Health Commission. Update on the novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak. February 10, 2020. Beijing: Beijing Health Commission; 2020. http://wjw.beijing.gov.cn/xwzx_20031/wnxw/202002/t20200211_1628034.html (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- Lu, H.; Stratton, C.W.; Tang, Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknownetiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J. Med.Virol. 2020, 92, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.L.; Wang, Y.M.; Wu, Z.Q.; Xiang, Z.C.; Guo, L.; Xu, T.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Li, X.W.; Li, H.; Fan, G.H.; Gu, X.Y.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, H.; Xu, J.Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.M.; Wu, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.W.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.R.; Dong, J.; Li, L.; Huang, C.L.; Zhao, J.P.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, Z.S.; Liu, L.L.; Qian, Z.H.; Qin, C.; Jin, Q.; Cao, B.; Wang, J.W. Iden-tification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: a descriptive study. Chin Med J. 2020, 133, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, L.X.; Wang, G.X.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Guo1, H.; Jiang, R.D.; Liu, M.Q.; Chen, Y.; Shen, X.R.; Wang, X.; Zheng, X.S.; Zhao, K.; Chen, Q.J.; Deng, F.; Liu, L.L.; Yan, B.; Zhan, F.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Xiao, G.F.; Shi, Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, M.Y.; Wang, W.; Song, G.Z.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; Yuan, M.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Dai, F.H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.M.; Zheng, J.J.; Xu, L.; Holmes, E.C.; Zhang, W.Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.J.; Ren, Z.G.; Li, X.X.; Yan, J.L.; Ma, C.Y.; Wu, D.D.; Ji, X.Y. Advances and challenges in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, L.F. Immune response, inflammation and the clinical spectrum of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization WHO. (2020). Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- De Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric R, Enjuanes L, Gorbalenya AE, Holmes KV, Perlman S, Poon L, Rootier PJM, Talbot PJ, Woo PCY, Ziebuhr J. (2012). Family coronaviridae: Part ii. The positive sense single stranded RNA viruses. In: Virus taxonomy: Classification and nomenclature of viruses. King A, Adams M, Carstens E, Lefkowitz E (eds.). Elsevier/Academic Press: Amsterdam, Boston, pp. 806–820.

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F. Receptor Recognition Mechanisms of Coronaviruses: a Decade of Structural Studies. 2015, 89, 1954–1964. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html?CDC AA refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprepare%2Ftransmission.html (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; Mcguire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020, 181, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.K.; Berne, M.A.; Somasundaran, M.; Sullivan, J.L.; Luzuriaga, K.; Greenough, T.C.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Kruger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; Muller, M.A.; Drosten, C.; Pohlmann, S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020, 181, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, S.; Netland, J. Coronaviruses post-sars: Update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri L, Ohja R, Pedro, L, Djannatian M, Franz, J, Kuivanen S, Kallio K, Kaya T, Anastasina M, Smura T, Levanov L, Szirovicza L, Tobi A, Kallio-Kokko H, Osterlund P, Joensuu M, Meunier F, Butcher S, Winkler M, Mollenhauer B, Helenius A, Gokce O, Teesalu T, Hepojoki J, Vapalahti O, Stadelmann C, Balistreri G, Simons M. (2020). Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and provides a possible pathway into the central nervous system. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- García, L.F. Immune response, inflammation, and the clinical spectrum of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, S.; Dandekar, A.A. Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus infections: implications for SARS. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, M.Z.; Poh, M.C.; Rénia, L.; MacAry, A.P.; Ng, L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sch€onrich, G.; Raftery, M.J.; Samstag, Y. Devilishly radical NETwork in COVID-19: Oxidative stress, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and T cell suppression. Adv. Biol. Reg. 2020, 77, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esakandari1, H.; Nabi-Afjadi, M.; Fakkari-Afjadi, J.; Farahmandian, N.; Miresmaeili, S.M.; Bahrein, E. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 characteristics. Biol. Procs. Online. 2020, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovato, A.; de Filippis, C.; Marioni, G. Upper airway symptoms in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Zhong, Z.; Ji, P.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Pang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C. Clinicopathological characteristics of 8697 patients with COVID-19 in China: a meta-analysis. Fam Med Commun Health. 2020, 8, e000406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Cui, J.; Huang, L.; Du, B.; Chen, L.; Xue, G.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Sun, Y.; Yao, H.; Li, N.; Zhao, H.; Feng, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, D.; Yuan, J. Rapid and visual detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) by a reverse transcription loopmediated isothermal amplification assay. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rettner R. (2020). How does the new coronavirus compare with the flu? Live Sci. 25.

- Paranjpe I, Russak A, De Freitas JK, Lala A, Miotto R, Vaid A, Johnson KW, Danieletto M, Golden E, Meyer D, Singh M, Somani S, Manna S, Nangia U, Kapoor A, O’Hagan A, O’Reilly PF, Huckins LM, Glowe P, Kia A, Timsina P, Freeman RM, Levin MA, Jhan J, Firpo A, Kovatch P, Finkelstein J, Aberg JA, Bagiella E, Horowitz CR, Murphy B, Fayad BZ, Narula J, Nestler EJ, Fuster V, Cordon-Cardo C, Charney DS, Reich DL, Just AC, Bottinger EP, Charney AW, Glicksberg BS, Nadkarni GN. (2020). Clinical Characteristics of Hospitalized Covid-19 Patients in New York City. medRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. (2020). Clinical predictors of mortality due to covid-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; Guan, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Tu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Cao, B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, P.; Ronconi, G.; Carafa, A.; Gallenga, C.E.; Ross, R.; Frydas, I.; Kritas, S.K. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by coronavirus-19 (COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2): Anti-inflammatory strategies. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 2020, 34, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; Tai, Y.; Bai, C.; Gao, T.; Song, J.; Xia, P.; Dong, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.S. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Giménez, V.M.; Inserra, F.; Tajer, C.D.; Mariani, J.; Ferder, L.; Reiter, R.J.; Manuch, W. Lungs as target of COVID-19 infection: Protective common molecular mechanisms of vitamin D and melatonin as a new potential synergistic treatment. Life Sci. 2020, 254, 117808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belen-Apak, F.B.; Sarıalioğlu, F. Pulmonary intravascular coagulation in COVID-19: possible pathogenesis and recommendations on anticoagulant/thrombolytic therapy. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2020, 50, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Xiao SY. (2020). Hepatic involvement in COVID-19 patients: Pathology, pathogenesis, and clinical implications. J. Med. Virol. [CrossRef]

- Rothan, H.A.; Byrareddy, S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmunity 2020, 109, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, WHO. (2020). COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---24-november-2020 (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Momattin, H.; Mohammed, K.; Zumla, A.; Memish, Z.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A. Therapeutic options for middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy. Int. J. Infect. Diseases. 2013, 17, e792–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.J.; Kim, K.H.; Yi, J.; Choi, S.J.; Choe, P.G.; Park, W.B.; Kim, N.J.; Oh, M.D. In vitro antiviral activity of ribavirin against severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, M.L.; Andres, E.L.; Sims, A.C.; Graham, R.L.; Sheahan, T.P.; Lu, X.; Smith, E.C.; Case, J.B.; Feng, J.Y.; Jordan, R.; Ray, A.S.; Cihlar, T.; Siegel, D.; Mackman, R.L.; Clarke, M.O.; Baric, R.S.; Denison, M.R. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. mBio. 2018, 9, e00221–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, C.E. Antiviral Actions of Interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 778–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, B.; Michaelis, M.; Baer, P.C.; Doerr, H.W.; Cinatl, J. Ribavirin and interferon-β synergistically inhibit SARS-associated coronavirus replication in animal and human cell lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 326, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, V.; Shannon, C.P.; Wei, X.S.; Xiang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.H.; Tebbutt, S.J.; Kollmann, T.R.; Fish, E.N. Interferon-α2b treatment for COVID-19. Front. Inmmunol. 2020, 11, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoudi-Monfared, E.; Rahmani, H.; Khalili, H.; Hajiabdolbaghi, M.; Salehi, M.; Abbasian, L.; Kazemzadeh, H.; Yekaninejad, M.S. A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of interferon-1a in treatment of severe COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01061–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wilde, A.H.; Pham, U.; Posthuma, C.C.; Snijder, E.J. Cyclophilins and cyclophilin inhibitors in nidovirus replication. Virol. 2018, 522, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sato, Y.; Sasaki, T. Suppression of coronavirus replication by cyclophilin inhibitors. Viruses. 2013, 5, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma-Lauera Y, Zhenga Y, Maleševićc M, von Brunna B, Fischerd G, von Brunn A. (2020). Influences of cyclosporin A and non-immunosuppressive derivatives on cellular cyclophilins and viral nucleocapsid protein during human coronavirus 229E replication. Antiv. Res.173, 104620. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen NN, von Brunn A, Hornum M, Jensen MB. (2020). Cyclosporine and COVID-19: risk or favorable?. Am. J. Transplant. [CrossRef]

- Keyaerts, E.; Vijgen, L.; Maes, P.; Neyts, J.; Ranst, M.V. In vitro inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by chloroquine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 323, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touret, F.; de Lamballerie, X. Of chloroquine and COVID-19. Antivir. Res. 2020, 177, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez S, Martínez O, Valenzuela F, Silva F, Valenzuela O. (2020). Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19: should they be used as standard therapy? Clin. Rheumatol. [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Lagier, L.C.; Parolaa, P.; Hoanga, V.T.; Meddeba, L.; Mailhea, M.; Doudier, B.; Courjone, J.; Giordanengo, V.; Vieiraa, V.E.; Dupont, H.T.; Stéphane Honoréi, S.; Colsona, P.; Chabrièrea, E.; La Scolaa, B.; Rolaina, J.M.; Brouqui, P.; Raoult, D. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J.Antimicrob. Agents. 2020, 56, 105949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.M.; Sisk, J.M.; Mingo, R.M.; Nelson, E.A.; White, J.M.; Frieman, M.B. Abelson Kinase Inhibitors are potent inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8924–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ortega, A.; Bernal-Bello, D.; Llarena-Barroso, C.; Frutos-Pérez, B.; Duarte-Millán, M.A.; de Viedma-García, V.G.; Farfán-Sedano, A.I.; Canalejo-Castrillero, E.; Ruiz-Giardín, J.M.; Ruiz-Ruiz, J.; San Martín-López, J.V. Imatinib for COVID-19: A case report. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 218, 108518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, M. COVID-19-driven endothelial damage: complement, HIF-1, and ABL2 are potential pathways of damage and targets for cure. Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugaraj, B.; Siriwattananon, K.; Wangkanont, K.; Phoolcharoen, W. Perspectives on monoclonal antibody therapy as potential therapeutic intervention for Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 38, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempowski, G.D.; Saunders, K.O.; Acharya, P.; Wiehe, K.J.; Haynes, B.J. Pandemic preparedness: developing vaccines and therapeutic antibodies for COVID-19. Cell. 2020, 181, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghazadeha, A.; Rezaei, N. Towards treatment planning of COVID-19: Rationale and hypothesis for the use of multiple immunosuppressive agents: Anti-antibodies, immunoglobulins, and corticosteroids. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauc, G.; Sinclair, D. Biomarkers of biological age as predictors of COVID-19 disease severity. Aging. 2020, 12, 6490–6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A.L.; McNamara, M.S.; Sinclair, D.A. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging. 2020, 12, 9959–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, N.M.; Selim, L.A. Characterisation of COVID-19 pandemic in paediatric age group: a systematic review and meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 128, 104395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, Z.; Odish, F.; Gill, I.; O’Connor, D.; Armstrong, J.; Vanood, A.; Ibironke, O.; Hanna, A.; Ranski, A.; Halalau, A. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 288, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannouchos TV, Sussman RA, Mier JM, Poulas K, Farsalinos K. (2020). Characteristics and risk factors for COVID-19 diagnosis and adverse outcomes in Mexico: an analysis of 89,756 laboratory–confirmed COVID-19 cases. Eur. J. Resp. [CrossRef]

- Burki, T.K. Coronavirus in China. Lancet Respir Med. 2020, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, X. Acute respiratory failure in COVID-19: is it “typical” ARDS? Critical Care. 2020, 24, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, K.J.; Choong, M.C.; Cheong, E.H.; Kalimuddin Wen, S.D.; Phua, G.C.; Chan, K.S.; Mohideen, S.H. Rapid progression to acute respiratory distress Syndrome: review of current understanding of critical illness from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2020, 49, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieco, D.L.; Bongiovanni, F.; Chen, L.; Menga, L.S.; Cutuli, S.L.; Pintaudi1, G.; Carelli, S.; Michi1, T.; Torrini, F.; Lombardi, G.; Anzellotti1, G.M.; De Pascale, G.; Urbani, A.; Bocci, M.G.; Tanzarella, E.S.; Bello, G.; Dell’Anna, A.M.; Maggiore, S.M.; Brochard, L.; Antonelli, M. Respiratory physiology of COVID-19- induced respiratory failure compared to ARDS of other etiologies. Crit Care. 2020, 24, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.M.; Tam, A.; Shaipanich, T.; Hackett, T.L.; Singhera, G.K.; Dorscheid, D.R.; Sin, D.D. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2000688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Meng, M.; Kumar, R.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Lian, N.; Deng, Y.; Lin, S. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID-19: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhi, Y.; Ying, S. COVID-19 and asthma: reflection during the pandemic. Clinic. Rev. Allerg. Immunol. 2020, 59, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhiba, K.D.; Patel, G.B.; Vu, T.H.T.; Chen, M.M.; Guo, A.; Kudlaty, E.; Mai, Q.; Yeh, C.; Muhammad, L.N.; Harris, K.E.; Bochner, B.S.; Grammar, L.C.; Greenberger, P.A.; Kalhan, R.; Kuang, F.L.; Saltoun, C.A.; Schleimer, R.P.; Stevens, W.W.; Peters, A.T. Prevalence and characterization of asthma in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 307–314.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adapa, S.; Chenna, A.; Balla, M.; Merugu, G.P.; Koduri, N.M.; Daggubati, S.R.; Gayam, V.; Naramala, S.; Konala, V.M. COVID-19 pandemic causing acute kidney injury and impact on patients with chronic kidney disease and renal transplantation. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2020, 12, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adapa, S.; Aeddula, N.R.; Konala, V.M.; Chenna, A.; Naramala, S.; Madhira, B.R.; Gayam, V.; Balla, M.; Muppidi, V.; Bose, S. COVID-19 and renal failure: challenges in the delivery of renal replacement therapy. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2020, 12, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, M. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; Gong, W.; Liu, X.; Liang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, H.; Yang, B.; Huang, C. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in wuhan, china. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.L.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Vecchié, A.; Bonaventura, A.; Talasaz, A.H.; Kakavand, H.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Perciaccante, A.; Castagno, D.; Ammirati, E.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Stevens, M.P.; Abbate, A. Cardiovascular considerations in treating patients with corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 75, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Huang, Z.; Lin, L.; Lv, J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease: A viewpoint on the potential influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers on onset and severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallarés-Carratalá, V.; Górriz-Zambrano, C.; Morillas-Ariño, C.; Llisterri-Caro, J.L.; Gorriz, J.L. COVID-19 y enfermedad cardiovascular y renal: ¿Dónde estamos?¿hacia dónde vamos?. Semergen 2020, 46 (Suppl. 1), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhi, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Bi, Z.; Zhao, Y. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadic, M.; Cuspidi, C.; Mancia, G.; Dell’Oro, R.; Grassi, G. COVID-19, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases: Should we change the therapy? Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadic, M.; Cuspidi, C.; Grassi, G.; Mancia, G. COVID-19 and arterial hypertension: Hypothesis or evidence? J. Clin. Hypertens. 2020, 22, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Jenner, B.L.; Wilkinson, I. COVID-19 and hypertension. J. Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2020, 21, 1470320320927851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha S. (2020). COVID-19 and pulmonary hypertension. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. ccc021. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Mahawar, K.; Xia, Z.; Yang, W.; EL-Hasani, S. Obesity and mortality of COVID-19. Meta-analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caci, G.; Albini, A.; Malerba, M.; Noonan, D.M.; Pochetti, P.; Polosa, R. COVID-19 and obesity: Dangerous liaisons. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, A.; Kreis, N.N.; Louwen, F.; Yuan, J. Obesity and COVID-19: Molecular mechanisms linking both pandemics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.E.; Lopez, R.; Sanchez, N.; Ng, S.; Gresh, L.; Ojeda, S.; Burger-Calderon, R.; Kuan, G.; Harris, E.; Balmaseda, A.; Gordon, A. Obesity increases the duration of influenza A virus shedding in adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1378–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, J.A.S.; Galindo-Fraga, A.; Ortiz-Hernández, A.A.; Gu, W.; Hunsberger, S.; Galán-Herrera, J.F.; Guerrero, M.L.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Beigel, J.H. Underweight, overweight, and obesity as independent risk factors for hospitalization in adults and children from influenza and other respiratory viruses. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2019, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Lavie, C.J.; Mehra, M.R.; Henry, B.M.; Giuseppe Lippi, G. Obesity and outcomes in COVID-19: When an epidemic and pandemic collide. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Shufa Du, S.; Green, W.D.; Beck, M.A.; Algaith, T.; Herbst, C.H.; Alsukait, R.F.; Alluhidan, M.; Alazemi, N.; Shekar, M. Individuals with obesity and COVID-19: A global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lusignan, S.; Dorward, J.; Correa, A.; Jones, N.; Akinyemi, O.; Amirthalingam, G.; Andrews, N.; Byford, R.; Dabrera, G.; Elliot, A.; Ellis, J.; Ferreira, F.; Bernal, J.L.; Okusi, C.; Ramsay, M.; Sherlock, J.; Smith, G.; Williams, J.; Howsam, G.; Zambon, M.; Joy, M.; Hobbs, F.D.R. Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 among patients in the Oxford Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre primary care network: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychter, A.M.; Zawada, A.; Ratajczak, A.E.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Should patients with obesity be more afraid of COVID-19? Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, D.; Salamanca-Fernández, E.; Rodríguez, B.M.; Navarro, P.P.; Jiménez, M.J.J.; Sánchez, M.J. Obesity as a risk factor in Covid-19: Possible mechanisms and implications. Aten. Primaria. 2020, 52, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Chaar, M.; King, K.; Galvez, L.A. Are black and hispanic persons disproportionately affected by COVID-19 because of higher obesity rates?. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 1096–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer M. (2020). Deadly companions: COVID-19 and diabetes in Mexico. Med. Antrhopol. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Bhowmik, B.; Do Vale Moreira, N.C. COVID-19 and diabetes: Knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 162, 108142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadic, M.; Cuspidi, C.; Sala, C. COVID-19 and diabetes: Is there enough evidence? J. Cli.n Hypertens. (Greenwich). 2020, 22, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Lau, E.S.H.; Ma, R.C.W.; Kong, P.S.A.; Wild, H.S.; Goggins, W.; Chow, E.; So, W.Y.; Chan, C.N.J.; Luk, O.Y.A. Secular trends in all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates in people with diabetes in Hong Kong, 2001–2016: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetol. 2020, 63, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuschieri, A.; Grech, S. COVID-19 and diabetes: The why, the what and the how. J. Diabetes Complications. 2020, 34, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erener, S. Diabetes, infection risk and COVID-19. Mol. Metab. 2020, 39, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniyappa, R.; Gubbi, S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E736–E741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.K.; Yoon, K.H.; Lee, M.K. Diabetes and COVID-19: Global and regional perspectives. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 166, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Arora, A.; Sharma, P.; Anikhindi, S.A.; Bansal, N.; Singla, V.; Khare, S.; Srivastava, A. Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID19? A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhman, G.; Bavuma, C.; Gishoma, C.; Gupta, N.; Kwan, G.F.; Laing, R.; Beran, D. Endemic diabetes in the world’s poorest people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 402–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruíz, J. Diabetes mellitus. Rev. Med. Suisse. 2012, 8, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, R.; Magon, A.; Irene Baroni, I.; Dellafore, F.; Arrigoni, C.; Pittella, F.; Ausili, D. Health literacy in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDF. (2019). Diabetes atlas. www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Guthrie, R.A.; Guthrie, D.W. Pathophisiology of diabetes mellitus. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2004, 27, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, J.M.; Cooper, M.E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 137–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida-Pititto, B.; Dualib, P.M.; Zajdenverg, L.; Rodrigues-Dantas Dias de Souza, F.; Rodacki, M.; Casaccia-Bertoluci, M. Severity and mortality of COVID 19 in patients with diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Synd. 2020, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Long, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z. ACE2 expression in pancreas may cause pancreatic damage after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2128–2130.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Martínez MM, Carrera-Boada C, Madera-Silva MD, Marín W, Contreras M. (2020). COVID-19 and diabetes: a bidirectional relationship. Clin. Investig. Arterioscler. S0214-9168, 30105–4. [CrossRef]

- Drago, L.; Nicola, L.; Ossola, F.; De Vecchi, E. In vitro antiviral activity of resveratrol against respiratory viruses. J. Chemother. 2008, 20, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.C.; Ho, C.T.; Chuo, W.H.; Li, S.; Wang, T.T.; Lin, C.C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. Infect. Diseases. 2017, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinella, M.A. Indomethacin and resveratrol as potential treatment adjuncts for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 74, e13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, L.H.; Bachari, K. Potential therapeutic effects of resveratrol against SARS-CoV-2. Acta Virol. 2020, 64, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, E.; Arslan, A.K.K.; Yerer, M.B.; Bishayee, A. Resveratrol and diabetes: A critical review of clinical studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulashekar, M.; Stom, S.M.; Peuler, J.D. Resveratrol’s potential in the adjunctive management of cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, alzheimer disease, and cancer. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2018, 118, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luc, K.; Schramm-Luc, A.; Guzik, T.J.; Mikolajczyk, T.P. Oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in prediabetes and diabetes. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 70, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camini, F.C.; Caetano, C.C.; Almeida, L.T.; De Brito Magalhães, C. Implications of oxidative stress on viral pathogenesis. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fregoso-Aguilar TA, Hernández-Navarro BC, Mendoza-Pérez JA. (2016). Endogenous antioxidants: A review of their role in oxidative stress. In Morales-González JA, Morales-González A, Madrigal-Santillán EO (eds.). The transcription factor NRF2: A master regulator of oxidative stress. InTech. Croatia. 3–19. [CrossRef]

- Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, MansonJJ (2020). COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 395, 1033–1034. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Mendoza, N.; Morales-González, A.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.O.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Álvarez-González, I.; García-Melo, L.F.; Anguiano-Robledo, L.; Fregoso-Aguilar, T.; Morales-Gonzalez, J.A. Antioxidant and adaptative response mediated by Nrf2 during physical exercise. Antioxidants. 2019, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-González, A.; Bautista, M.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Posadas-Mondragón, A.; Anguiano-Robledo, L.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Álvarez-González, I.; Fregoso-Aguilar, T.; Gayosso-Islas, E.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Morales-González, J.A. Nrf2 modulates cell proliferation and antioxidants defenses during liver regeneration induced by partial hepatectomy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 7801–7811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matzinger, M.; Fischhuber, K.; Heiss, E.H. Activation of Nrf2 signaling by natural products-can it alleviate diabetes? Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1738–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales RY. (2020). Manual de prevención y tratamiento para COVID-19 con plantas medicinales de los Altos de Chiapas. Colectividad Nichim Otanil. México. 72 pags. https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/trazos/cultura/2020/06 (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Cuevas-Barragan, C.E.; Buenrostro-Nava, M.T.; Palos-Gómez, G.M.; Ramirez-Padilla, E.A.; Mendoza-Macias, B.I.; Rivas-Caceres, R.R. Use of Nasoil® via intranasal to control the harmful effects of Covid-19. Microb Pathog. 2020, 149, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreou A, Trantza S, Filippou D, Sipsas N, Tsiodras S. (2020). COVID-19: The potential role of copper and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in a combination of candidate antiviral treatments against SARS-CoV-2. In vivo. 34: 1567-1588.

- . [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Aw, T.Y.; Stokes, K.Y. N-acetylcysteine attenuates systemic platelet activation and cerebral vessel thrombosis in diabetes. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasram, M.M.; Dhouib, I.B.; Annabi, A.; El Fazaa, S.; Gharbi, N. A review on the possible molecular mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine against insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes development. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 48, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yao, J.; Han, C.; Yang, J.; Chaudhry, M.T.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Yin, Y. Quercetin, inflammation and immunity. Nutrients. 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, M.P.; Kandaswami, C.; Mahajan, S.; Chadha, K.C.; Chawda, R.; NairandSchwartz, S.A.H. The flavonoid, quercetin, differentially regulates Th-1 (IFNgamma) and Th-2 (IL4) cytokine gene expression by normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002, 1593, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colunga-Biancatelli, R.M.L.; Berrill, M.; Catravas, J.D.; Marik, P.E. Quercetine and vitamin C: An experimental, Synergistic therapy for the prevention and treatment of SARS-COVD-2 related disease (COVID-19). Front. Inmmunol. 2020, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X.; Fan, J. Therapeutic effects of quercetin on inflammation, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 9340637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.H.; Haddad, P.S. The antidiabetic potential of quercetin: underlying mechanisms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Li, X.; He, L.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Zhong, L.; Tong, R.; Jiang, Z.; Shi, J.; Li, J. Antidiabetic potential of flavonoids from traditional chinese medicine: A review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2019, 47, 933–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.M.; Lee, K.M.; Koon, C.M.; Cheung, C.S.F.; Lau, C.P.; Ho, H.M.; Lee, M.Y.H.; Au, S.W.N.; Cheng, C.H.K.; Lau, C.B.S.; Tsui, S.K.W.; Wan, D.C.C.; Waye, M.M.Y.; Wong, K.B.; Wong, C.K.; Lam, C.W.K.; Leung, P.C.; Fung, K.P. Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia cordata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 118, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; Bose, S.; Shin, N.R.; Chin, Y.W.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, H. Pharmaceutical impact of Houttuynia cordata and metformin combination on high-fat-diet-induced metabolic disorders: Link to intestinal microbiota and metabolic endotoxemia. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 24, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Prasad, S.K.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Hemalatha, S. Antihyperglycemic activity of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 2014, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, V.; Roviello, G.N. Lower COVID-19 mortality in Italian forested areas suggests immunoprotection by Mediterranean plants. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhatem, M.N.; Setzer, W.N. Aromatic herbs, medicinal plant-derived essential oils, and phytochemical extracts as potential therapies for coronaviruses: Future perspectives. Plants. 2020, 9, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Shah, S.; Ahmad, J.; Abdullah, A.; Johnson, S.K. Effect of incorporating bay leaves in cookies on postprandial glycemia, appetite, palatability, and gastrointestinal well-being. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Zaman, G.; Anderson, R.A. Bay leaves improve glucose and lipid profile of people with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2009, 44, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaerunnisa S, Kurniawan H, Awaluddin R, Suhartati S, Soetjipto S. (2020). Potential inhibitor of COVID-19 main protease (Mpro) from several medicinal plant compounds by molecular docking study. Preprints. 2020030226. [CrossRef]

- Tutunchi, H.; Naeini, F.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J. Naringenin, a flavanone with antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects: A promising treatment strategy against COVID-19. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 3137–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartogh, D.J.; Tsiani, E. Antidiabetic properties of naringenin: A citrus fruit polyphenol. Biomolecules. 2019, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, Y.A.; Suryavanshi, S.V. Combination of naringenin and lisinopril ameliorates nephropathy in Type-1 diabetic rats. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 2020, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheid, A.H.; Babiker, M.Y.; Awad, T.A. Evaluation of certain medicinal plants compounds as new potential inhibitors of novel corona virus (COVID-19) using molecular docking analysis. In silico Pharmacol. 2021, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.S.; Sushma, P.; Dharmashekar, C.; Beelagi, M.S.; Prasad, S.K.; Shivamallu, C.; Prasad, A.; Syed, A.; Marraiki, N.; Prasad, N.S. In silico evaluation of flavonoids as effective antiviral agents on the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, M.; Thotakura, B.; Sekaran, S.P.C.; Jyothi, A.K.; Sundaramurthi, I. Naringin ameliorates streptozicin-induced diabetes through forkhead box M1-mediated beta cell proliferation. Cells Tissues Organ. 2018, 206, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Subhan, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Uddin, S.J.; Reza, H.M.; Sarker, S.D. Effect of citrus flavonoids, naringin and naringenin, on metabolic syndrome and their mechanisms of action. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Pérez JA, Fregoso-Aguilar T. (2013). Chemistry of natural antioxidants and studies performed with different plants collected in México. In Morales-Gonzalez JA (ed.) Oxidative stress and Chronic degenerative diseases: A role for antioxidants. InTech, Croatia. Pages 59–85.

- Borkotoky S, Banerjee M. (2020). A computational prediction of SARS-CoV-2 structural protein inhibitors from Azadirachta indica (Neem). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.R.; Kazmi, S.M.R.; Iqbal, N.T.; Iqbal, J.; Ali, S.T.; Abbas, S.A. A quadruple blind, randomised controlled trial of gargling agents in reducing intraoral viral load among hospitalised COVID-19 patients: A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020, 21, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg S, Anand A, Lamba Y, Roy A. (2020). Molecular docking analysis of selected phytochemicals against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro receptor. Vegetos. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ogidigo JO, Iwuchukwu EA, Ibeji CU, Okpalefe O, Soliman MES. (2020). Natural phyto, compounds as possible noncovalent inhibitors against SARS-CoV2 protease: computational approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Baildya, N.; Khan, A.A.; Ghosh, N.N.; Dutta, T.; Chattopadhyay, A.P. Screening of potential drug from Azadirachta Indica (Neem) extracts for SARS-CoV-2: An insight from molecular docking and MD-simulation studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1227, 129390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parida, P.K.; Paul, D.; Chakravorty, D. The natural way forward: Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of phytochemicals from Indian medicinal plants as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 targets. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 3420–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adithya J, Nair B, Aishwarya S, Nath LR. (2020). The plausible role of Indian traditional medicine in combating Corona Virus (SARS-CoV 2): a mini-review. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. [CrossRef]

- Will, J.C.; Byers, T. Does diabetes mellitus increase the requirement for vitamin C? . Nutrition Revs. 1996, 54, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.; Willis, J.; Gearry, R.; Skidmore, P.; Fleming, E.; Frampton, C.; Carr, A. Inadequate vitamin C status in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: associations with glycaemic control, obesity, and smoking. Nutrients. 2017, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.N. Vitamin C for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertension. Arch. Med. Revs. 2019, 50, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Rowe, S. The emerging role of vitamin C in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z. Intravenous high-dose vitamin C for the treatment of severe COVID-19: study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020, 10, e039519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Study type | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Borkotoky and Banerjee, 2020 [153] | Docking and simulation methods to identify small molecule inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Membrane (M) and Envelope (E) proteins, which are essential for virus assembly and budding. | Of the 70 compounds monitored, we found that five compounds interacted with protein E and two interacted with protein M (nimocin and nimbolin) |

| Khan et al., 2020 [154] | PCR studies in humans to compare the effectiveness of an oral solution based on A. indica with other substances | Reduction of the intraviral oral burden confirmed with real time-PCR i |

| Adithya et al., 2020 [155] | Comparative study comparing information on Ayurvedic Medicine and its antiviral effects | Seven of the plants most used in Ayurvedic Medicine are mentioned ( including A. indica) have antiviral potential |

| Garg et al., 2020 [156] | Molecular docking of the 38 bioactive compounds of five plants effective against SARS-COV-2. | Some of the compounds, such as nimbin, inhibit inhibin the expression of the protein Mpro of COVID-19 |

| Ogidigo et al., 2020 [157] | Computer study of the compounds of two plants with antiviral properties compared with FDA drugs-of-reference | Six compounds including nimbolin had strong inhibitory reactions with the Mpro of COVID-19 |

| Baildya et al., 2021 [158] | Molecular docking and molecular dynamic study of the extracts of different parts A. indica against PLpro del COVID-19 | All compounds presented inhibition in the protein PLpro (above all DesaCetylGedunin (DCG), found in Neem seed) |

| Parida et al., 2020 [159] | molecular dynamic study on the effectiveness of 55 Ayurvedic on SARS-COV-2 | Withanolide R and 2,3-Dihydrowithaferin A were the compounds that interacted with the proteases and the spikes of the virus, but more evaluation is required |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).