1. Introduction

Concrete structures inevitably degrade over time as a result of exposure to environmental factors. Reinforced-concrete components subjected to axial loads, such as structural columns, piles, and bridge piers, are utilized to transfer compression forces from upper surfaces to lower ones. Typically, these compressive elements are the most significant members of the structure [

1,

2,

3]. Polymer bars are viable alternatives in reinforced columns subjected to bending and shear loads, owing to their physical and mechanical properties, as well as their resistance to corrosion and electromagnetic interference [

4].

In recent years, significant research has been conducted on various uses of FRP bars as flexural and shear reinforcement for reinforced concrete [

5,

6,

7,

8]. say synonym: Nevertheless, the axial compression behavior of FRP-RC elements has not been determined yet [

9]. International codes acknowledged the use of CFRP bars in compressive elements, like concrete columns, without any contribution to load-bearing capacity. In contrast, there is no Australian standard governing CFRP-reinforced concrete, and the Chinese technical code GB50608-2010 only provides guidelines for the design of FRP-reinforced flexural concrete elements [

10,

11]. Previous studies indicated that the contribution of CFRP bars to the capacity of columns ranged from 4% to 16% of the total capacity of the columns [

12] in comparison with 7 and 18% when CFRP bars were used [

13,

14] and between 11 and 17% when steel bars were applied [

1,

15]. Some studies have shown that the contribution of FRP bars to the capacity of eccentrically loaded RC columns can be disregarded [

16], while others portrayed that their contribution is considerable, such as Hadhood et al. considered an averagely contribution of 27% in column’s capacity [

3], and Guérin et al. indicated that CFRP bars in short RC columns contributed to carrying eccentric loads by 3%, 5%, and 13% at eccentricities of 10%, 20%, and 40%, respectively [

17]. The ductility of columns is influenced by various factors, including the longitudinal reinforcement ratio, the spacing and type of transverse reinforcement, and the loading conditions [

18,

19]. It was reported that increasing the longitudinal reinforcement ratio improved the ductility of CFRP-RC and CFRP-RC columns under axial loading [

20,

21]. Transverse bars with a closer spacing provide greater confinement to the concrete core of RC columns and prevent the buckling of longitudinal reinforcement bars [

16,

20,

22]. FRP transverse bars showed a significant impact on ductility, increasing by 60% to 205%, as the spiral bar spacing was reduced from 100 mm to 35 mm, while their effect on capacity was less pronounced [

23]. ACI 440.1R-15 and CSA-S806-12 set identical provisions and requirements for FRP and steel transverse bars; however, these standards may need revision because FRP bars have a lower elasticity modulus than steel reinforcement [

24,

25]. Research has shown that CFRP/CFRP spirals provide greater confinement for column ductility compared to CFRP/CFRP ties [

20].

The effects of concrete types on FRP-RC columns are different. Steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) and macro-synthetic fiber are highly practical and effective for crack control, offering increased crack resistance and enhanced ductility [

26]. The fiber volume fraction (V

f) plays a critical role in the compressive strength of concrete. A low fiber content is mainly effective for crack control without significantly enhancing compressive capacity, while a V

f of 0.5%–1.5% can increase compressive strength by 3.5%–18%. [

27]. Additionally, the fiber length-to-diameter ratio (l/d) positively influenced the compressive strength of SFRC [

28], However, if the ratio exceeded a certain threshold, it resulted in the opposite effect. [

29]. Reported that if we use hybrid fibers in concrete columns, it would result in improvements of the strength, confinement, and ductility in different loadings [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

This research involved experimental investigations into the behavior of MSFRC-RC columns reinforced with CFRP and steel bars as longitudinal and transverse reinforcements, respectively, under axial compression loads. Macro-synthetic fibers were incorporated into the concrete to enhance both ductility and strength. Another objective was to substitute steel with CFRP to assess the structural response of CFRP-RC columns. Consequently, various types of specimens were fabricated based on parameters such as plain and modern materials, as well as different configurations. The results from the compressive loading tests were analyzed and compared with various design formulas available in the literature and international codes. Additionally, a theoretical model was selected for MSFRC-RC columns, considering CFRP bars as longitudinal reinforcement and steel bars as transverse reinforcement, along with varying spiral and hoop spacings. This study aimed to understand the structural behavior of MSFRC-RC columns and their potential application in the construction industry.

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Sample Design

2.1.1. Concretes

Based on requirements of ASTM/C150 [

36], the Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) type-II with maximum crashed aggregates size by 12 mm were used for PC and MSP in this study. As shown in

Figure 1, fibers type of macro-synthetic was POLYTAR-GT600.

Table 1 presented physical and mechanical properties of MS. To obtain a homogeneous concrete mixture, Plastit

®SPC218 was used as a superplasticizer for FC. The reduced water ratio to cement was 30% for PC and MSP. In accordance with ASTM/C143 [

10], slump values of 80 mm and 70 mm were obtained for the fresh PC and MSP, respectively. As given in

Table 2, Three cylinders by the dimension of 150 mm × 300 mm and ingredients were fabricated for each batch of PC and FC. It was induced under a standard compression loading rate of 0.28 MPa/s according to ASTM/C39 [

12] to obtain the average strength of samples at the age of 28 days. For PC and MSP, test results were amounts of 31.2 MPa and 34.5 MPa with standard deviations of 2.07 and 2.23, respectively. When testing the corresponding concrete columns, these tests were performed.

2.1.2. Reinforcement

Steel and CFRP bars with a diameter of 9.7 mm were used as longitudinal reinforcement, while steel bar with a diameter of 6.4 mm was applied transversely in the circular column sections. The CFRP bars were impregnated with thermosetting polyester resin, and included fillers and additives to achieve a fiber volume content of 86%.

Table 3 presents the physical and mechanical properties of both the steel and CFRP bars.

2.2. Specimen Fabrication

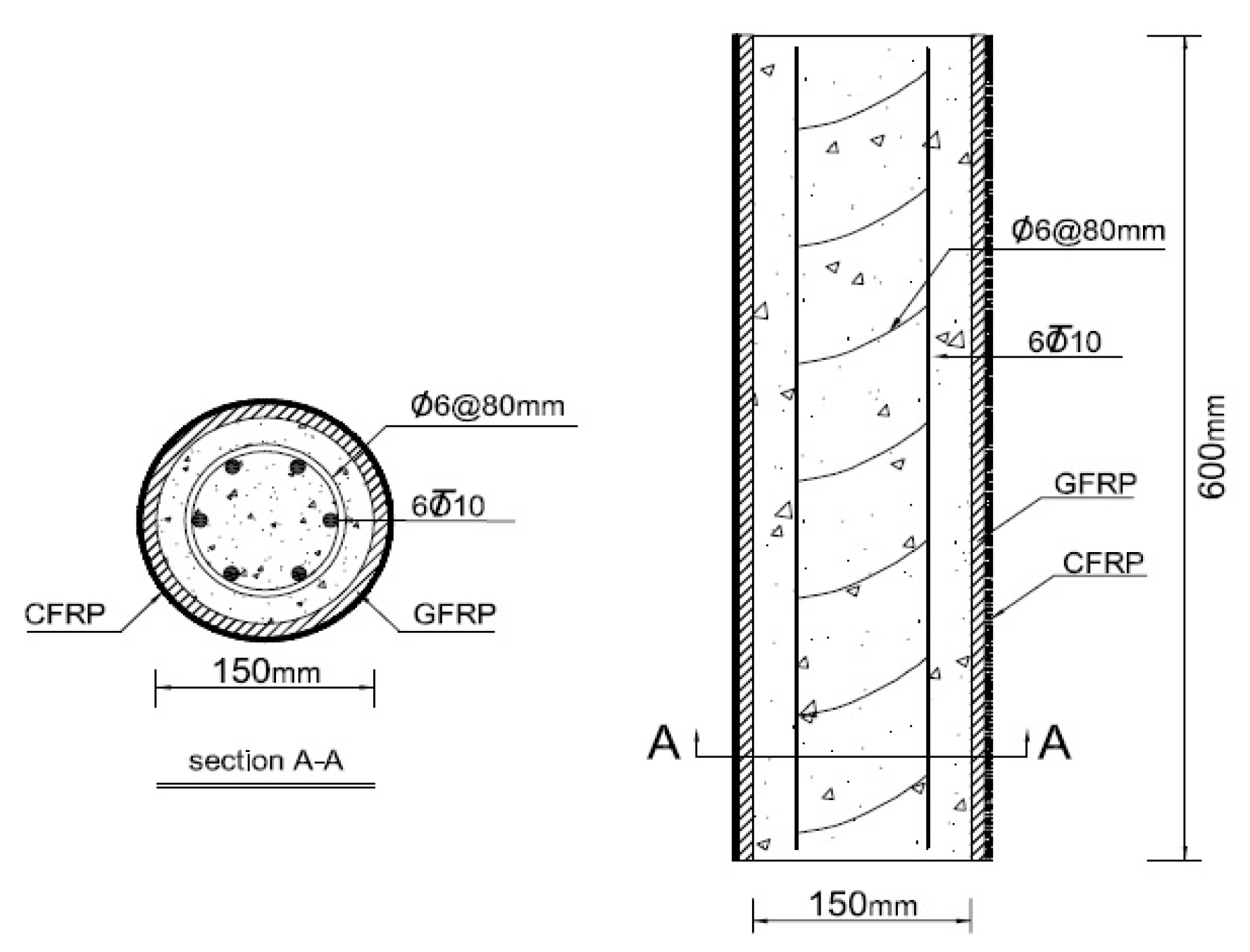

For this study, 16 circular columns were prepared, divided into four sets: Group I included four CFRP-reinforced plain concrete (CRCC) samples, Group II contained four CFRP-reinforced fiber concrete (CRFC) samples, Group III consisted of four steel-reinforced plain concrete (SRPC) samples, and Group IV comprised four steel-reinforced fiber concrete (SRFC) samples. Each column was laterally reinforced with steel bars configured as ties (hoops) and spirals, spaced at 40 mm and 75 mm, respectively.

Table 4 outlines the specifications of each test specimen. Column designations used letters and numbers: the first letter, either G or S, indicated the type of longitudinal bars as CFRP or steel, while the second letter, P or F, specified the concrete type as plain or fiber concrete, respectively. The third letters, T and P, represented the type of transverse reinforcement, indicating tied bars and spiral bars, respectively. The number specified the spacing of the transverse reinforcement. These columns were tested to assess the influence of macro-synthetic fibers, longitudinal bars, confinement type, and pitch spacing on the structural response of the specimens under concentric loading. Each specimen had a diameter of 150 mm and a height of 600 mm. The concrete cover was set at 50 mm.

Figure 1 illustrate the configurations of two columns reinforced with spiral and tie bars, spaced at 75 mm. The spacing of the spiral/tie steel bars served to prevent elastic buckling in CFRP bars and inelastic buckling in steel bars [

10].

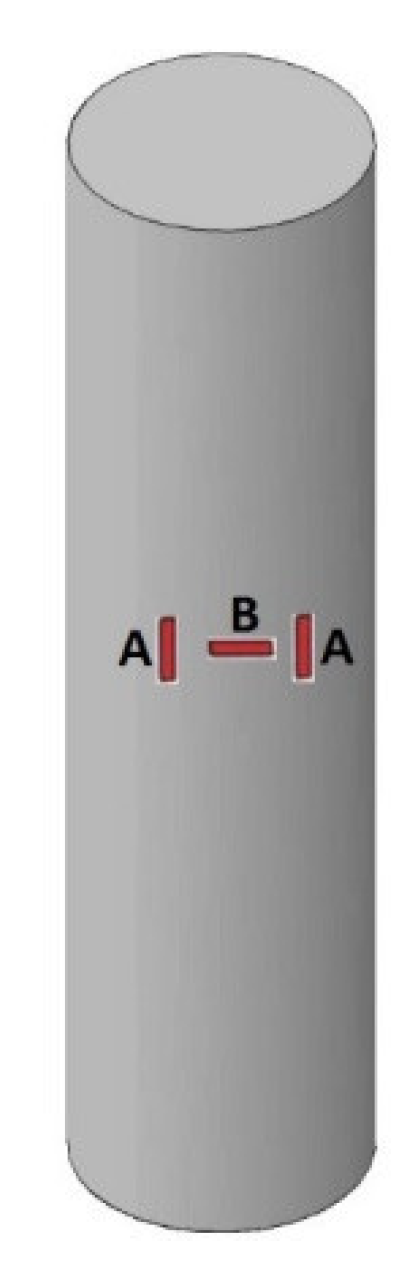

2.3. Columns’ Testing Setup and Instrument

Internal instrumentation included two strain gauges-A (TML

®PFL-20-11) mounted at the midpoint of the CFRP/steel longitudinal bars and one strain gauges-B attached to the steel spirals and hoop bars, as shown in

Figure 2. Strain data from all bars was recorded via an electronic data logger connected to a computer. To ensure even load distribution across the column cross-section, sulfur capping was applied to the top and bottom surfaces of the columns prior to testing,

Figure 3 shows the fabricated columns prior to the axial compression tests. The columns were then tested under a loading rate of 10 kN/s using a compression machine with a 5,000 kN capacity. In the testing machine, the lower hydraulic jaw was movable, while the upper jaw was fixed. A concentric compressive load was applied to the top surface of each column. Two LVDTs were positioned on sides of each column to measure concentric compressive deformation. Both the applied load and column deflection were recorded through a data acquisition system connected to the compression testing machine, as shown in

Figure 4.

3. Results of Experiments

The axial compressive strength for SRPC and SRFC specimens ranged from 560 kN to 717 kN, while the CRPC and CRFC columns exhibited strengths between 505 kN and 610 kN. The CP-T75 column recorded the lowest axial strength at 505 kN, whereas the SF-P40 column achieved the highest axial strength at 717 kN. Columns with spiral/hoop bars at a 40 mm pitch showed an average of 10% higher axial strength than those with a 75 mm pitch. The axial strengths of columns with spirals were, on average, 4.5%, 3.9%, 8.7%, and 5.5% further, respectively, than those of their counterparts with hoops. The addition of macro-synthetic fibers to plain concrete increased axial strength, with CRFC and SRFC columns showing strengths 7.8% and 6% higher, respectively, than those of CRPC and SRPC columns.

Table 5 presents the experimental results based on the LVDT data outputs.

In SRPC and SRFC specimens, the axial compression strengths were observed higher than their CRPC and CRFC counterparts. Compression strengths and corresponding deflections of SRPC and SRFC specimens – reinforced longitudinally by steel bars – were obtained averagely 18% and 6.7%, respectively, further compared with CRPC and CRFC specimens – reinforced longitudinally by CFRP bars. Also, the compression strength of CRPC columns was averagely received by 85.1% of SRPC columns’ strength and values of 536 kN versus 630 kN, respectively. CRFC columns, on average, showed a compression strength of 578 kN, which was 13% less than their counterpart columns in SRFC. The corresponding deflection at the maximum compression strength of CRPC columns was averagely 10% lower than SRPC columns, which presented the value of 3.6 mm versus 4.0 mm, respectively.

4. Ductility Index of the Column

The structural member’s capacity of the energy absorption after reaching the maximum axial compression strength is identified as “ductility” presented based on different types of parameters like strain, deflection, rotation, members’ dissipated or absorbed energy [

12]. In this study, based on the proposed equations of Elchalakani & Ma and Saffarian [

12,

38,

39,

40] the ductility index (DI) of the columns containing PC and FC, respectively, were determined.

where A75% and are total areas of the under load–deflection curves up to 75% of columns’ maximum axial strength called Pu and for PC and FC, respectively, which are related to the corresponding deflections called and at axial compression strengths called and in elastic regions. Also, A85% and are total areas of the under load–deflection curves up to 85% of columns’ maximum axial strengths, which are related to the corresponding deflections called and at axial compression strengths called and in post-peak regions of the curves for CC and FC, respectively, as graphically represented for PC and FC in Figure 8.

Based on experimental results, the ductility indices of CRPC columns were higher than their SRPC counterparts, as observed in the previous research [

20,

40]. The DI of CRPC columns was averagely 109.5% of that of SRPC specimens. Similarly, the DI of CRFC specimens than SRFC counterparts was higher, and it was observed averagely 137.3%, which was due to using fiber content in the improvement of the post-peak behavior and a more expanded softening branch of the load-deflection curve [

38,

39]. As the pitch of spiral or tied bar decreases, the DI of the columns increases because of the well-confined CFRP and steel bars and confining the affective transversal of the concrete core for absorbing more energy [

2,

41]. The DI of CRPC and CRFC columns increased averagely 131.7% and 125.7%, respectively, due to the decrease of the spiral and tied bars pitch from 75 mm to 40 mm. Similarly, the DI of SRPC and SRFC columns improved averagely 122% and 119%, respectively, with the decrease of the spiral and tied bars pitch from 75 mm to 40 mm. The confinement of spiral bars was higher than hoop bars in circular columns [

10,

42], and their ductility indices were gained by averagely 115.6%. Ductility indices columns of CP-T75, CF-T75, SP-T75, and SF-T75 were obtained 4.1, 4.6, 3.9, and 4.2, respectively, while the ductility indices columns of CP-P75, CF-P75, SP-P75, and SF-P75 were received 4.3, 4.6, 4.1 and 4.3, respectively. The ductility index parameter for columns basis on the axial compression loading and the corresponding axial deflection was given in

Table 6.

Table 6 displays the effectiveness of confining of spirals and hoops on the core concrete’s strength enhancement, which was presented by the ratio

and

for PC and FC, respectively, where

and

were the confined concrete compressive strength for PC and FC, respectively and

was the unconfined concrete compressive strength (0.85

). It was observed that the increase of the volumetric ratio from 1.71% to 3.22%, ratio

averagely raised by 5.6%; As ratio

of the CP-T40, CP-P40, CF-T40, CF-P40, SP-T40, SP-P40, SF-T40, and SF-P40 columns were 1.06, 1.03, 1.06, 1.02, 1.13, 1.04, 1.03, and 1.08 higher than their counterpart columns, respectively. Also, the ratio

of columns were averagely enhanced by 8.7% from spirals to hoops; As the ratios of CP-P75, CP-P40, CF-P75, CF-P40, SP-P75, SP-P40, SF-P75, and SF-P40 columns were 1.077, 1.039, 1.118, 1.074, 1.159, 1.063, 1.054, and 1.112 further than their counterpart specimens, respectively. In conclusion, the piths of lateral bars were more effective on columns’ confinement than the type of transversal reinforcements.

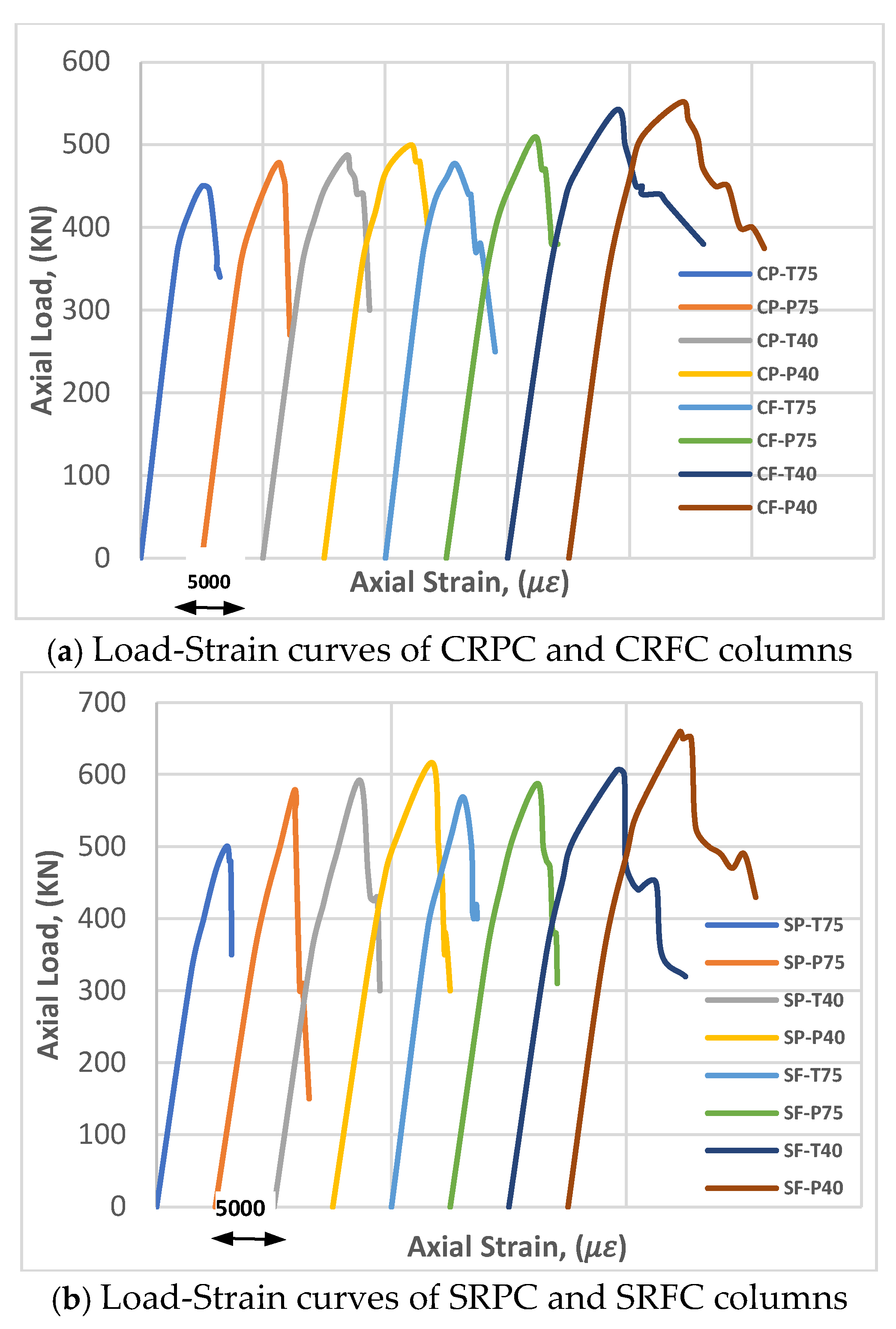

5. Load-Strain Relationship in Columns

The RC columns load-strain curves that reinforced by CFRP and steel as longitudinal bars and confined by steel spiral and hoop bars, respectively, were presented in

Figure 5 (a and b). The behavior of all columns was initially relatively linear in the pre-peak branch, up to the ultimate loads; This stiffness was because of compressive strength of PC and FC. The maximum concentric load (Pu) of CFRP RC columns varied from 505 to 610 kN, and the steel RC columns ranged from 560 to 717kN. The higher loads were corresponded to specimens’ confinement due to the type of their configurations. The CRPC, CRFC, SRPC, and SRFC columns with spirals had higher compression strengths by 5%, 4.3%, 9.7%, and 6% than their counterpart columns. The lateral strains were measured averagely at the peak load for the CP-P75, CP-P40, CF-P75, and CF-P40 columns by values of 374, 585, 442, and 809

, respectively, which were further as compared with the CP-T75, CF-T40, SP-T75, and SF-T40 columns by amounts of 306, 518, 324, and 698

, respectively (

Table 6).

In the post-peak branch of load-strain curves, confinement pressures were activated initially with lateral cracks due to spirals and hoops. The axial strains in maximum loads of the CRPC, CRFC, SRPC, and SRFC columns were averagely measured by values of 6000, 7333, 6625, and 7583 , respectively, presented FC (CRFC and SRFC) had higher axial strains than PC in counterpart specimens by 22% and 14%, respectively, indicating the effectiveness of SF materials and CFRP bars in columns’ ductility. In this stage, the dilation of the core concrete occurred, and the confinement restriction of spirals and hoops began to carry the load with increasing the lateral strains, up to approximately 85% of the maximum axial compression strength of columns.

On the other hand, axial strains of longitudinal bars for CRPC, CRFC, SRPC, and SRFC columns were averagely 5790, 7383, 1490, and 1625 , respectively, indicated 19%, 25%, 6%, and 6.5% of their ultimate tensile strains, respectively. Also, the of the CFRP bars in CRPC and CRFC columns varied from 29.59 kN to 78.19 kN, and the of the steel bars in SRPC and SRFC columns ranged from 98.19.91 kN to 163.65 kN. The significant differences of values between CFRP and steel bars were because of having the reinforcement ratios equally rather than equally the axial stiffness in tests. The of CRPC, CRFC, SRPC, and SRFC were averagely 7.9%, 9.4%, 19.9%, and 20.7%, respectively, presented the CFRP bars contribution were less than steel bars contribution in ultimate compression loads (Pu).

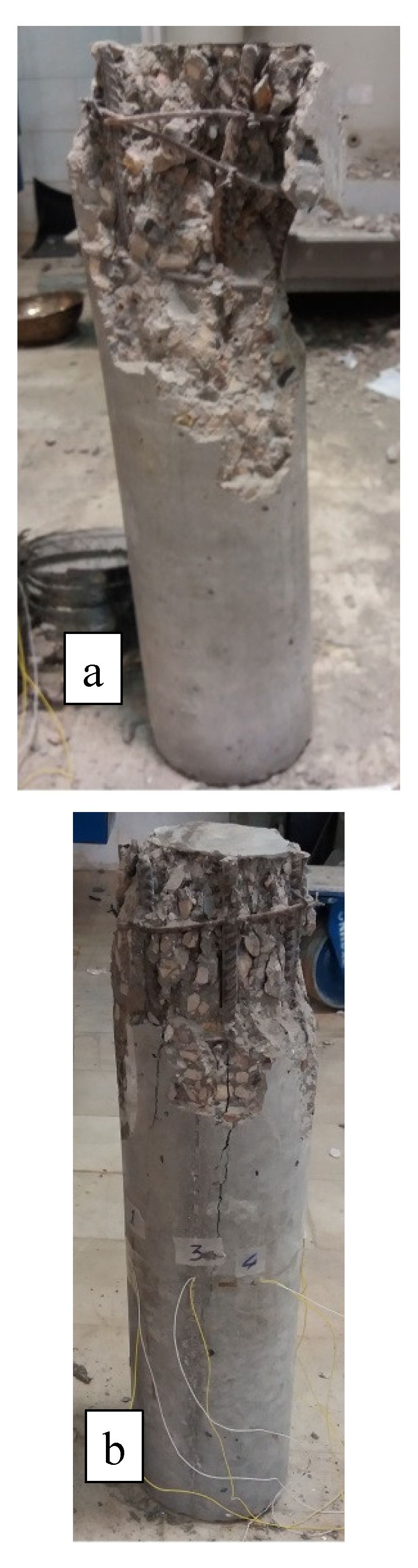

The failure modes were similarly displayed by four groups i.e., CRPC, CRFC, SRPC, and SRFC columns. During the failure process, mode of failure causes of interlaminar degradation of CFRP bars occurred with 75 mm pitch of spirals and tied bars (CP-T75, CP-P75, CF-T75 and CF-P75), while steel was yielded because of longitudinal bars buckling (SP-T75, SP-P75, SF-T75, and SF-P75). The failure modes caused the rupture of spirals/ties, and the crush of the columns’ concrete core with the value spacing of 40 mm spirals/ties (CP-T40, CP-P40, CF-T40, CF-P40, SP-T40, SP-P40, SF-T40, and SF-P40).

Figure 6 represents modes and crack patterns of two columns under axial loading.

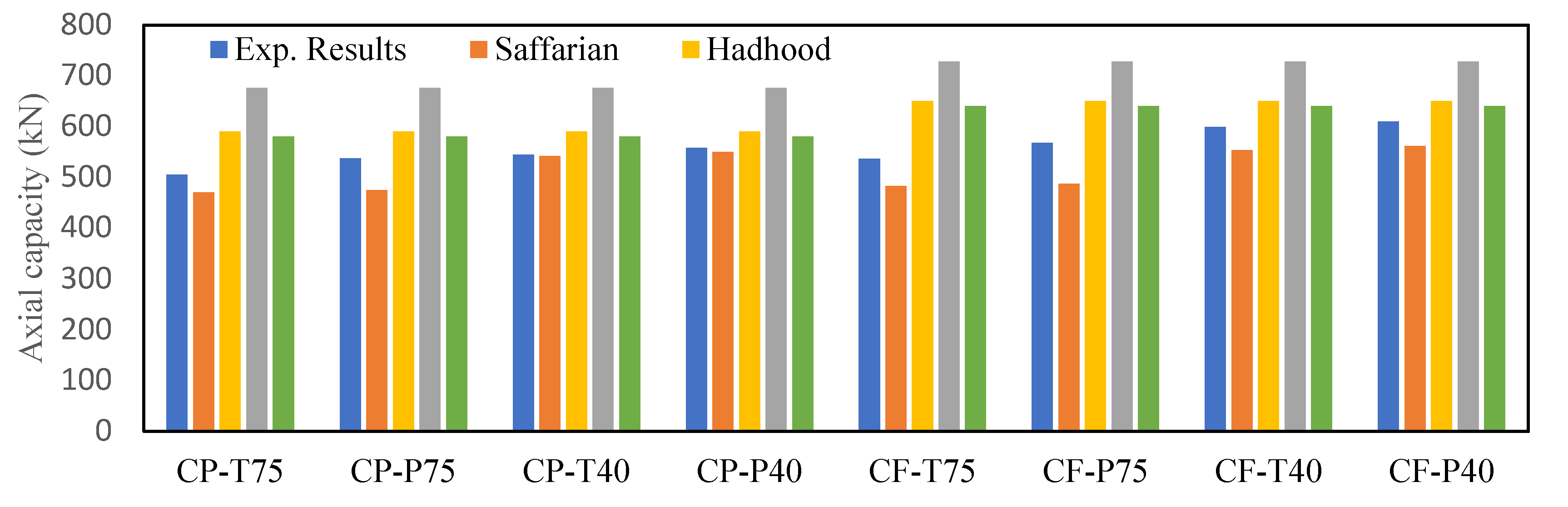

6. Axial Capacity of Columns in the Literature

The researchers proposed relationships to determine the capacity of columns reinforced with polymer bars based on different criteria, which can be generally divided into four groups. In this part, the experimental results of this research are compared with some existing relationships.

Saffarian et. al. [

12] proposed an equation for calculating the axial compressive strength (

Pu) of CFRP-RC columns was proposed as represented by Eq. (8). This equation is presented for hybrid reinforced columns with CFRP bar as a longitudinal reinforcement, steel bar as a transversal bar, and steel fibers, after spalling of concrete cover.

where

= transverse steel reinforcement ratio,

= effectiveness factor of spiral and hoop bars that was taken 1 and 0.9, respectively,

= steel yielding stress of spiral/hoop reinforcement,

tensile modulus of elasticity of CFRP bars, and

= compressive strength of PC and FC.

As stated previously, some studies such as Hadhood et al. [

43,

44] proposed the columns’ nominal axial capacity with FRP longitudinal bars as Eq. (3) in which the FRP bars’ contribution to the capacity of columns is neglected.

where

= nominal capacity corresponding to first peak load,

= reduction factor which was taken 0.85,

= compressive strength of concrete,

= area of the concrete gross section of concrete,

= area of FRP longitudinal reinforcement. Some researchers proposed various philosophies to consider the contribution of FRP bars to the FRP-RC columns capacities. Some of them suggested equations determined a reduction factor for the low axial compression strength of CFRP bars in columns compression capacities, as presented by Afifi et al. [

45] and Tobbi et al. [

46] in Eq. (4)

where

the ratio of the axial compressive strength to the tensile strength of CFRP bars which was taken 0.35,

= CFRP bars tensile strength. Using Eq. (2), the nominal axial compression capacity of columns was calculated 24% higher than the compression capacity of CFRP-RC columns was averagely obtained in this test. Some other researchers proposed the contribution of CFRP bars based on the compressive strain of concrete [

44]. In this approach, suggested equations adopted the CFRP bars strains, to calculate their contribution to the capacity of CFRP-RC columns. Maranan et al. [

44,

47] presented Eq. (5)

where

= reduction factor which was taken 0.9,

tensile modulus of elasticity of CFRP bars. According to the strain compatibility between concrete and CFRP bars, the bars strain was taken equal to the ultimate concrete strain, which varied between 0.2 and 0.35% [

44].

Figure 7 compares experimental results with the theoretical equation suggested predictions for the axial strength of CRPC and CRFC columns. It should be noted and used in theoretical equations A

core instead of A

g, because the lateral bars are activated when the spalling cover of concrete has occurred. Some equations were not considered either lateral confinement of transversal reinforcement or spalling cover of concrete. These equations had a close result with experimental results. The proposed equations of Saffarian et al. [

12], Hadhood et al. [

3], Tobbi et al. [

48], and Maranan et al. [

23] than to test results were averagely calculated at 0.92, 1.11, 1.26, and 1.10, respectively. These results showed that the relationship presented by Safarian et al. was close to experimental results while the equation of Maranan et al. was also close to test results.

8. Conclusions

In this research the compressive behavior of circular RC columns reinforced with CFRP/steel as longitudinal bars, spirals/ hoops as transversal bars were investigated. Sixteen short-scale RC columns were fabricated to study the effect of four parameters on the test: longitudinal bars type, configuration of confinement reinforcement type, lateral bars volumetric ratio, and concrete type (PC/FC). Based on the research, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The CRPC, CRFC, SRPC, and SRFC columns’ axial stains were averagely measured and indicated that CRFC and SRFC columns had higher axial strains than CRPC and SRPC counterpart specimens by averagely 22% and 15%, respectively, indicating the effectiveness of macro-synthetic fibers and CFRP bars in columns’ ductility.

- The DIs of CRPC and CRFC columns were 4.7% and 12.9% higher than those of SRPC and SRFC columns, respectively, showing columns reinforced by CFRP bars were more ductile than their columns counterparts reinforced by steel bars.

-The CRPC and CRFC specimens’ compression strength were averagely 85% and 87% of compressive strengths of their SRPC and SRFC counterparts, respectively, portraying CFRP bars’ contribution in compression strength of columns had less in those of steel bars in columns by values of 15% and 13%, respectively.

-The CRPC, CRFC, SRPC, and SRFC columns with spirals had averagely higher compression strengths by 4.5%, 3.9%, 8.7%, and 5.5%, respectively, than their counterpart columns with hoops that provides more efficiency of the spiral bar than to the hoop bar on axial compressive strength of RC columns.

- The experimental results presented a close agreement with the equations considering the axial involvement of polymeric longitudinal bars, steel-spiral/hoop bar, reinforcement volumetric reinforcement, and type of the concrete, after spalling cover of concrete, like the proposed equation by Saffarian et al.

References

- ACI318–19, Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete. American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills, Michigan, USA, 2019.

- Shafieinia, M. and F. Sajedi, Evaluation and comparison of GRP and FRP applications on the behavior of RCCs made of NC and HSC. Smart Structures and Systems, 2019. 23(5): p. 495-506.

- Hadhood, A., H. Mohamed, M., F. Ghrib, and B. Benmokrane, Efficiency of glass-fiber reinforced-polymer (GFRP) discrete hoops and bars in concrete columns under combined axial and flexural loads. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2017. 114: p. 223-236. [CrossRef]

- ACI-committee440, “Guide for the Design and Construction of Structural Concrete Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Bars”, ed. ACI Committee 440. 2015.

- Trong Nghia-Nguyen, T.C.-L., Samir Kh., Magd A.W., A novel approach to the complete stress strain curve for plastically damaged concrete under monotonic and cyclic loads. Computers and Concrete, 2021. 28: p. 39-53.

- Mehmet E. G., A.C., Sarwar H. M., Crack pattern and failure mode prediction of SFRC corbels: Experimental and numerical study. Computers and Concrete, 2021. 28: p. 507-519.

- Saffarian, I., Strengthening of Concrete Structures using FRP System. Book of KCEO, 2019. 1(2). ISBN: 978-622-00-0091-4.

- Saffarian, I., New techniques of strengthening concrete structures with FRP. International Journal of Civil & Structural Engineering, 2008.

- Saif A., M.K.D., Suraparb K., Predictive model for the shear strength of concrete beams reinforced with longitudinal FRP bars. Structural Engineering and Mechanics, 2022. 84: p. 143-154.

- Saffarian I, Atefatdoost GR, Hosseini SA, and Shahryari L., Experimental and numerical research on the behavior of steel-fiber -reinforced-concrete columns with GFRP rebars under axial loading. Structural Engineering and Mechanics, 2023. 86(3): p. 399-415.

- Chandrasekaran A., N.U., Experimental investigations on resilient beam-column end-plate connection with structural fuse Steel and Composite Structures, 2023. 47(3): p. 315-337.

- Saffarian I, Atefatdoost GR, Hosseini SA, and Shahryari L., Experimental research on the behavior of circular SFRC columns reinforced longitudinally by GFRP rebars. Computers and Concrete, 2023. 31(6): p. 513-525.

- Ahmad A, K.Q., Raza A., Reliability Analysis of Strength Models for CFRP-Confined Concrete Cylinders. Compos Struct, 2020. 244: p.:112-123.

- Xue, W., F. Peng, and Z. Fang, Behavior and Design of Slender Rectangular Concrete Columns Longitudinally Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars. ACI Structural Journal, 2018. 115. [CrossRef]

- Josef F., P.B., Lva B., Evaluation of steel fiber distribution in concrete by computer aided image analysis. Composite Materials and Engineering, 2019. 1.

- Xue W., P., Fang Z, Behavior and design of slender rectangular concrete columns longitudinally reinforced with fiber-reinforced polymer bars. ACI Struct. J., 2018. 115 (2).

- Guérin M, M.H., Benmokrane B, Shield C., Nanni A, Effect of glass fiber-reinforced polymer reinforcement ratio on axial-flexural strength of reinforced concrete columns. ACI Struct. J., 2018. 115(4): p. 1049-1061.

- Guérin, M., H. Mohamed, B. Benmokrane, A. Nanni, and C. Shield, Eccentric Behavior of Full-Scale Reinforced Concrete Columns with Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars and Ties. ACI Structural Journal, 2018. 115. [CrossRef]

- Saffarian I and Saffarian A, Experimental research on the behavior of circular steel-fiber-reinforced-concrete columns reinforced by CFRP bars. International Conference on Smart Materials and Polymer Technology (ICSMPT-2023), 2023.

- Sajedi SF, Saffarian I., Pourbaba M., and Yeon JH, Structural Behavior of Circular Concrete Columns Reinforced with Longitudinal GFRP Rebars under Axial Load. Building, 2024. 14(4): p. 998. [CrossRef]

- Tobbi, H., A. Farghaly, and B. Benmokrane, Strength Model for Concrete Columns Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars and Ties. Aci Structural Journal, 2014. 111: p. 789-798. [CrossRef]

- Khorramian K., S.P., Experimental and Analytical Behavior of Short Concrete Columns Reinforced with GFRP Bars under Eccentric Loading. Engineering Structures, 2017. 151: p. 761–773. [CrossRef]

- Maranan, G.B., A.C. Manalo, B. Benmokrane, W. Karunasena, and P. Mendis, Behavior of concentrically loaded geopolymer-concrete circular columns reinforced longitudinally and transversely with GFRP bars. Engineering Structures, 2016. 117: p. 422-436. [CrossRef]

- ACI-committee440, “Guide for the Design and Construction of Structural Concrete Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Bars”, ed. ACI Committee 440. 2022.

- Canadian Standards Association C.S.A., Design and construction of building components with fibre-reinforced polymers. CAN/CSA, S806-12., 2017(Ontario: CSA.).

- 544, A.C., State-of-the-Art Report on Fiber Reinforced Concrete. ACI, 2018. 544.4-18: p. 66.

- Yazıcı S, I.G., Tabak V., Effect of aspect ratio and volume fraction of steel fiber on the mechanical properties of SFRC. Constr Build Mater 2007. 21(6): p. 1250–3.

- Shan L, Z.L., Experimental study on mechanical properties of steel and polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete. Appl Mech Mater 2014: p. 584–586. [CrossRef]

- Wang X., F.F., Lai J., Xie Y.,, Steel fiber reinforced concrete: A review of its material properties and usage in tunnel lining. Structures, 2021. 34: p. 1080-1098.

- Bazrkar H., Rahimi M., Saffarian I., Naisipour M., and Ansarinia MR, Application of Fiber Concrete with Macro-Synthetic Fibers in Slabs of Drilling Rig Locations of the National Iranian Oil South Company (NISOC). ABA, 2024: p. https://www.concreteday.ir/paper?manu=75670.

- Taheripour M. and Saffarian I., Experimental and Numerical Study on a Novel Steel Beam-Column Connection to Short Stub Column Under Cyclic Loading. preprint, 2024.

- M. Naisipour, M.L., S. A. Sadrnejad, An Assessment of Compressive Size Effect of Plane Concrete Using Combination of Micro-Plane Damage Based Model and 3D Finite Elements Approach. American Journal of Applied Sciences 2008. 5(2): p. 106-109.

- Taheripour M., H.F., Raoufi R., Numerical Study of Two Novel Connections with Short End I or H Stub in Steel Structures. Advanced Steel Construction, 2022. 18(1): p. 495-505.

- Taheripour M., H.F., Raoufi R., Numerical investigation of the new steel connection using short stub column. Analysis of Structure and Earthquake, 2023. 20(2): p. 62-77.

- Zhang X., D.Z., Experimental study and theoretical analysis on axial compressive behavior of concrete columns reinforced with GFRP bars and PVA fibers. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 172: p. 519-532. [CrossRef]

- ASTM-C150/C150M-18, Standard Specification for Portland Cement. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2018.

- Park R., P.M.J.N., Code provisions for confining steel in potential plastic hinge regions of columns in seismic seismic design. The new zealand national society for earthquakee engineering, 1980. 13.1.

- Ahmed Sherif Essawy, M.E.-H., Strength and ductility of spirally reinforced rectangular concrete columns. Construction and Building Materials, 1998. 12(1): p. 31-37.

- Bencardino F., R.L., Spadea G., Swamy R.N, Stress-Strain Behavior of Steel Fiber-Reinforced Concrete in Compression. Materials in civil engineering, 2008. 20: p. 255-263. [CrossRef]

- Elchalakani, D.M. and G. Ma, Tests of glass fibre reinforced polymer rectangular concrete columns subjected to concentric and eccentric axial loading. Engineering Structures, 2017. 151: p. 93-104.

- Elchalakani M., D.M., Karrech A., Li G., Mohamed M.S.A., Yang B, Experimental Investigation of Rectangular Air-Cured Geopolymer Concrete Columns Reinforced with GFRP Bars and Stirrups. J Compos Constr 2019. 23(3).

- Qaiser A.R., Z.K.U., Experimental and theoretical study of GFRP hoops and spirals in hybrid fiber reinforced concrete short columns. Materials and Structures, 2020. 53(139).

- Hadhood A., H.M., Brahim B., Faouzi G, Efficiency of glass-fiber reinforced-polymer (GFRP) discrete hoops and bars in concrete columns under combined axial and flexural loads. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2017. 114.

- Elmessalami N., E.R.A., Abed F, Fiber-reinforced polymers bars for compression reinforcement: A promising alternative to steel bars. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 209: p. 725-737.

- Afifi M., H.M., Brahim B, Axial Capacity of Circular Concrete Columns Reinforced with GFRP Bars and Spirals. Journal of Composites for Construction, 2014. 18.

- Hany Tobbi, A.S.F., and Brahim Benmokrane, Concrete Columns Reinforced Longitudinally and Transversally with Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL, 2012. 109(4).

- Maranan G., M.A., Benmokrane B., Karunasena W., Mendis P, Evaluation of the flexural strength and serviceability of geopolymer concrete beams reinforced with glass-fibre-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars. Eng. Struct., 2015. 101. [CrossRef]

- Tobbi H., Benmokrane B., and F. A, Concrete Columns Reinforced Longitudinally and Transversally with Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars. ACI Structural Journal, 2012. 109(4). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).