Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

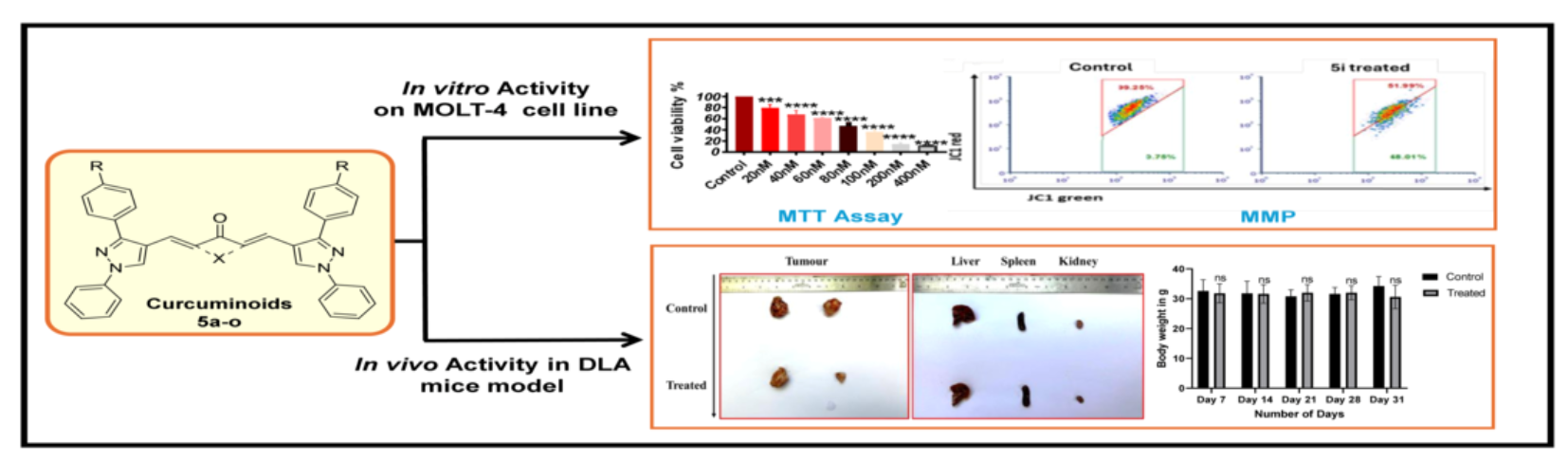

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

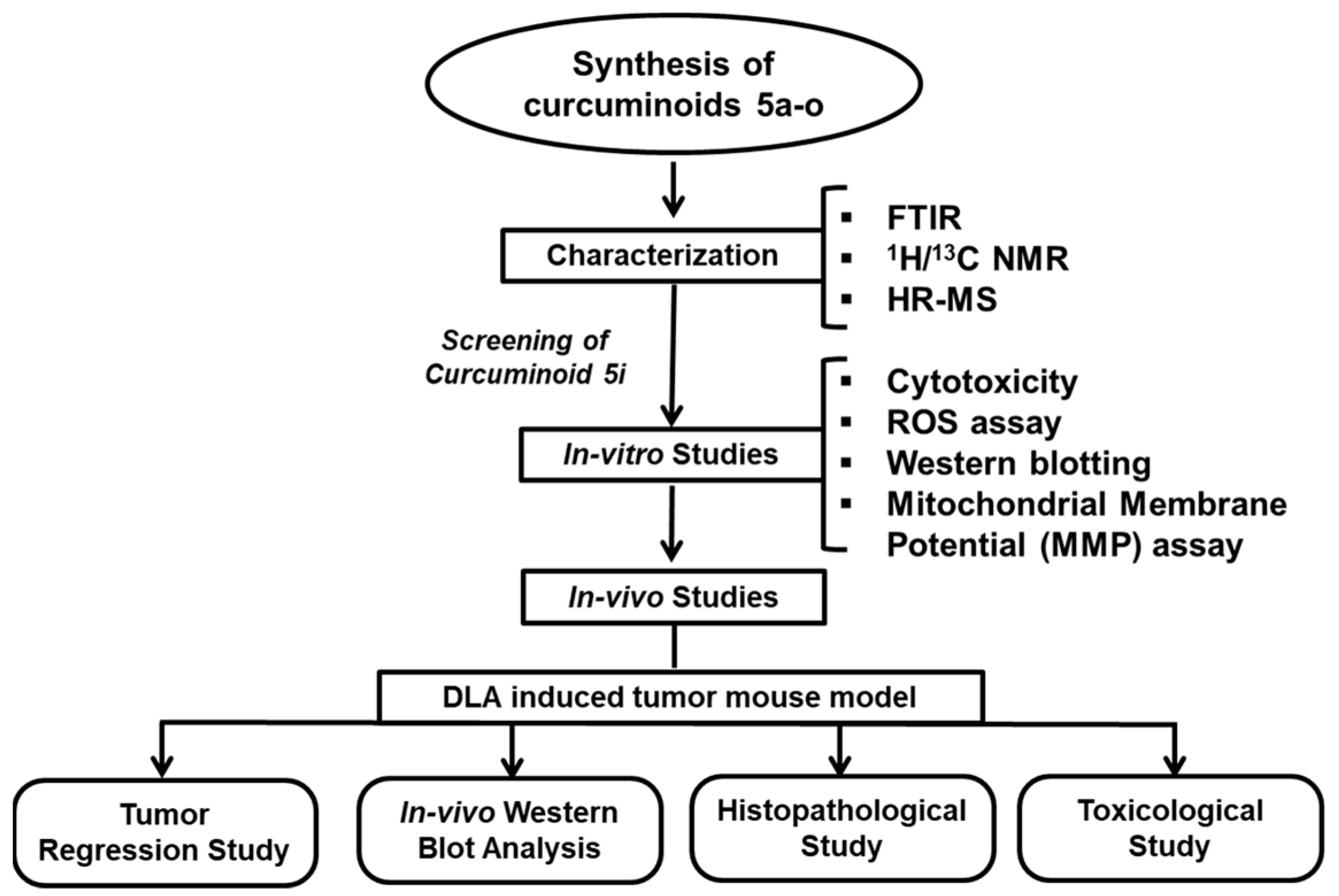

2. Results

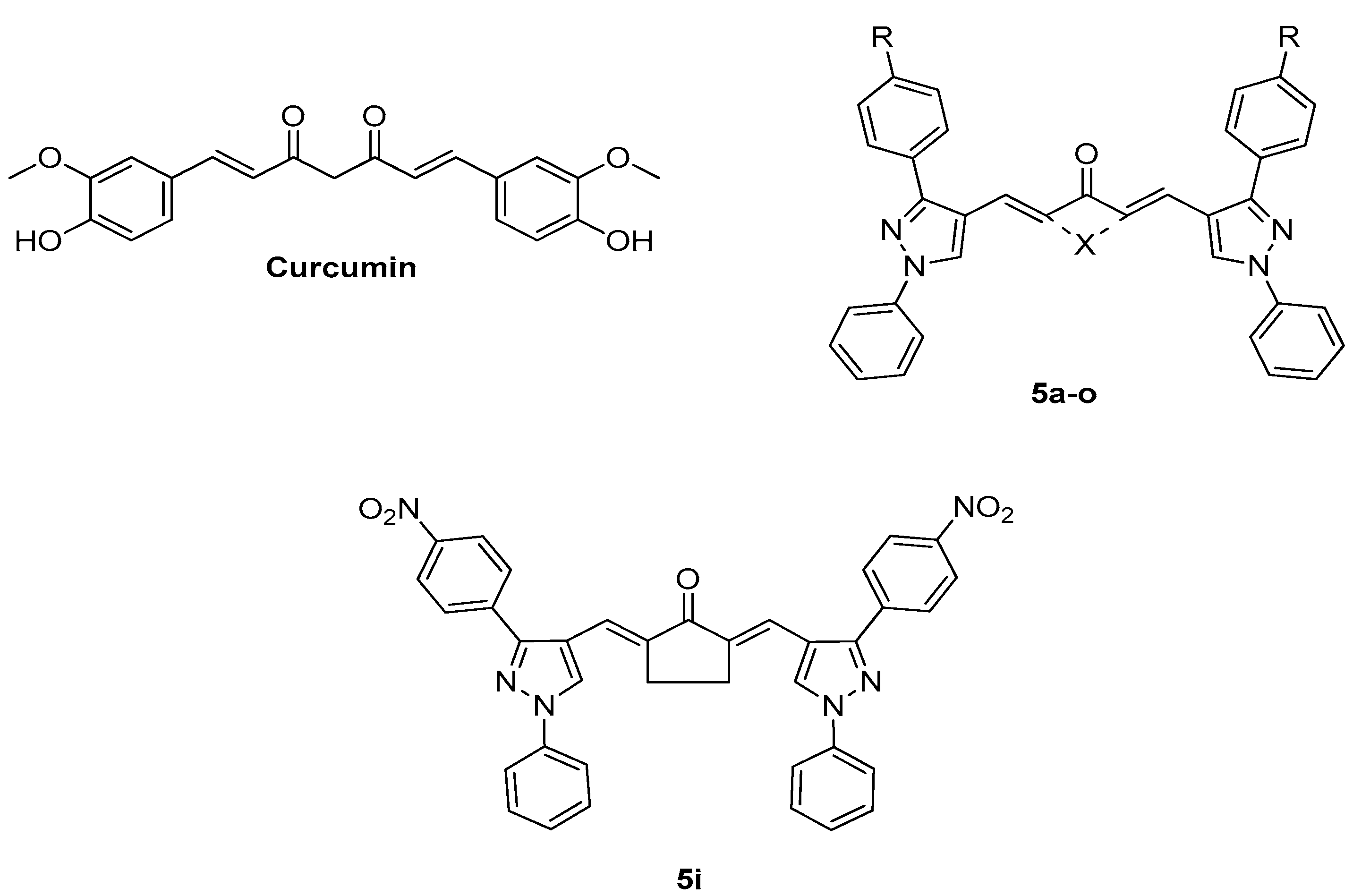

2.1. Chemistry

Synthesis and Characterization of Curcuminoids

2.2. In Vitro Studies

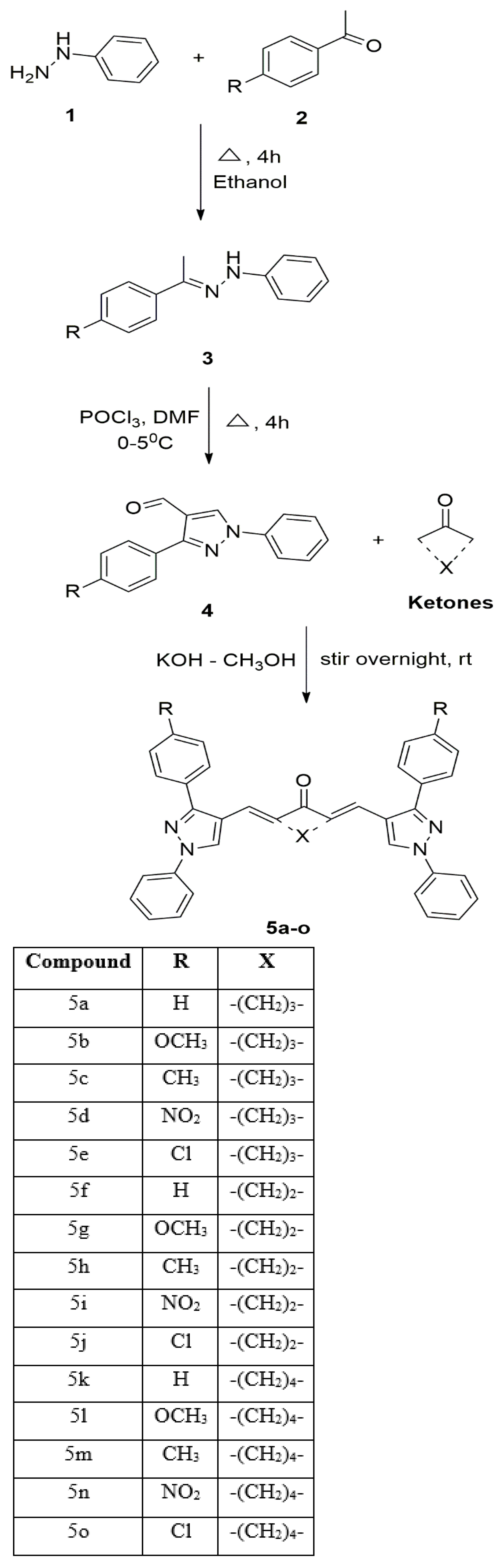

2.2.1. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation

2.2.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation in Cell Lines

2.2.3. 5i Alters Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP) (∆ψm)

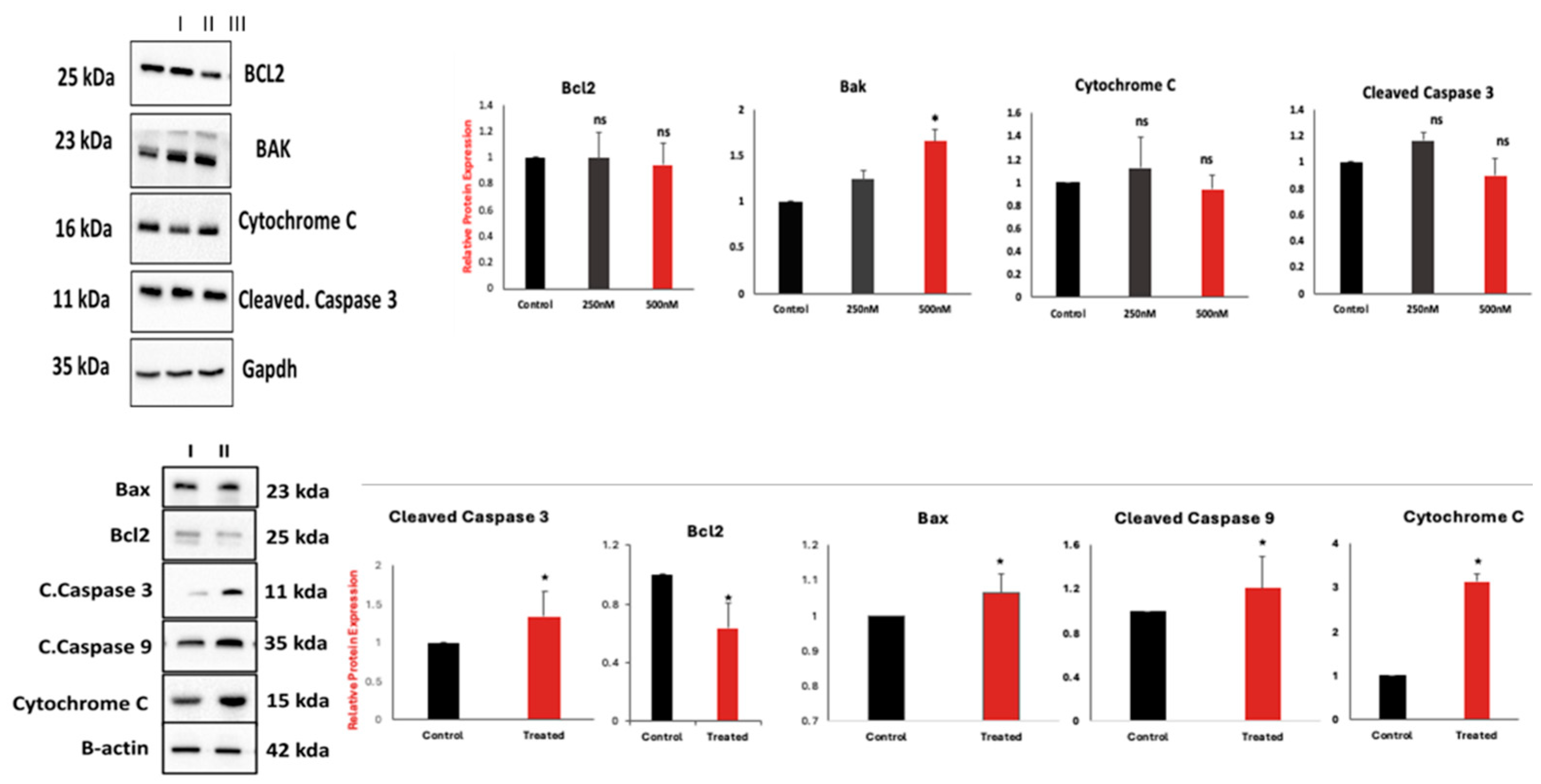

2.2.4. 5i Treatment-Induced Apoptotic Activation in MOLT-4 Cells

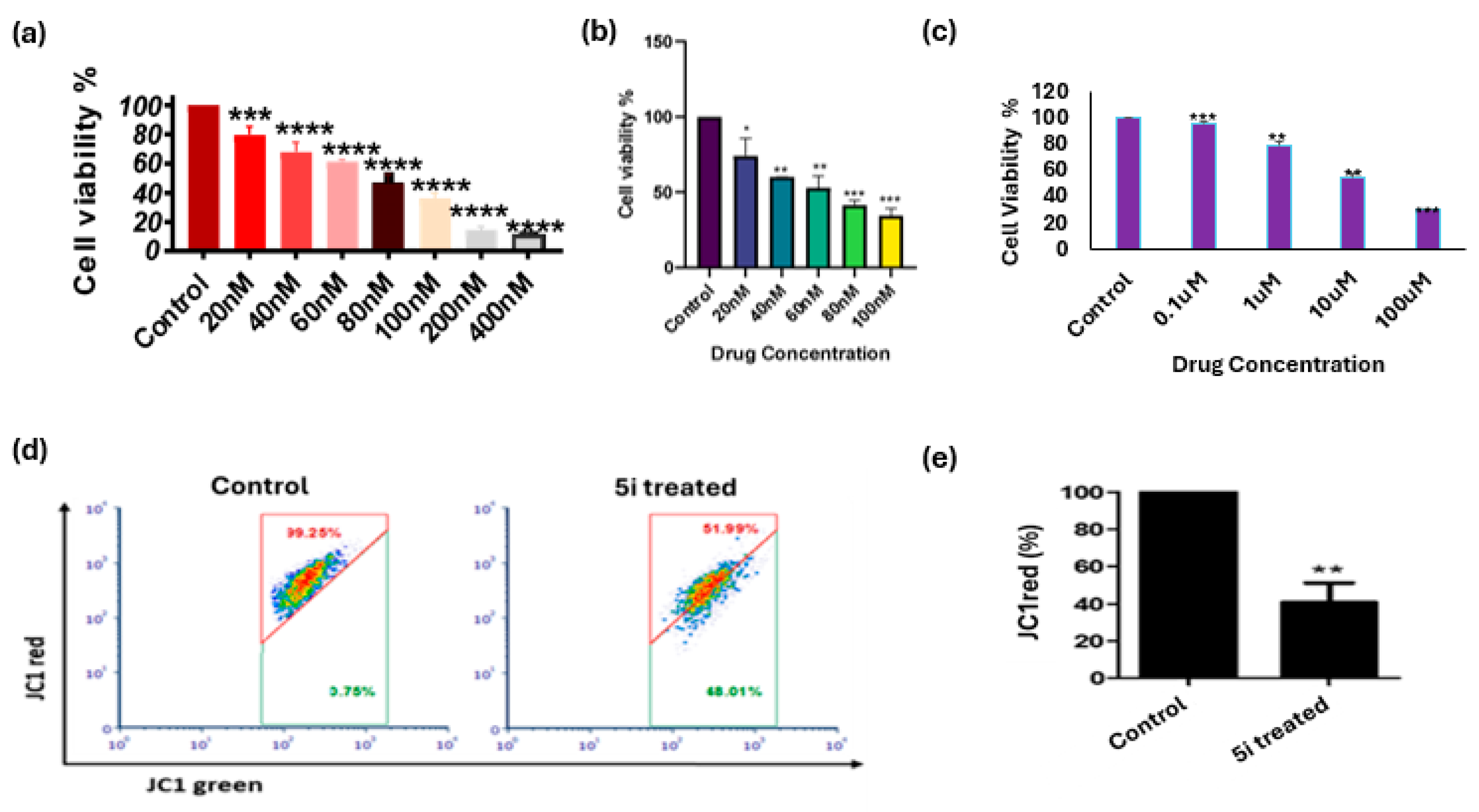

2.3. In Vivo Studies

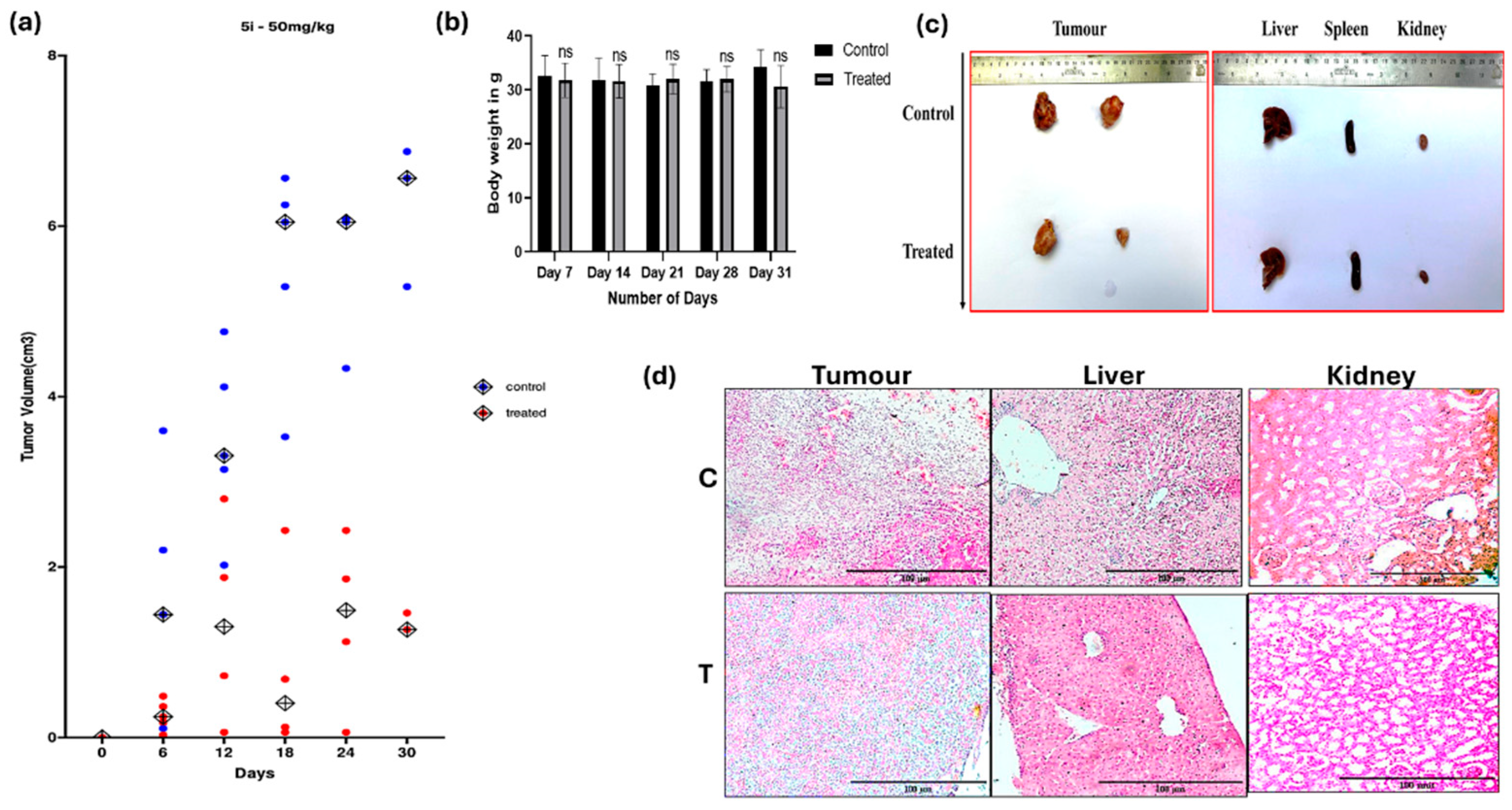

5i Induced Tumor Regression in DLA Mouse Model Without Observable Toxicity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

Synthesis and Characterization of Curcuminoids

4.2. In Vitro Studies

4.2.1. Cell Lines and Cultures

4.2.2. MTT Assay

4.2.3. Resazurin Assay

4.2.4. JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm) Assay

4.2.5. Western Blotting

4.3. In Vivo Studies

4.3.1. Animals

4.3.2. Investigating the Anticancer Potential of 5i in Mice Models

4.3.3. Histological Evaluation of Tumor and Organs (Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fah, Chueahongthong; Tima, S.; Sawitree, Chiampanichayakul; Berkland, C. Songyot Anuchapreeda The Effect of Co-Treatments of Chemotherapeutic Drugs and Curcumin on Cytotoxicity and FLT3 Protein Expression in Leukemic Stem Cells. Research Square (Research Square), 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major Cancer Types by Deaths Worldwide 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/288580/number-of-cancer-deaths-worldwide-by-type/ (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- GUNZ, F.W.; HOUGH, R.F. Acute Leukemia over the Age of Fifty: A Study of Its Incidence and Natural History. Blood 1956, 11, 882–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebbi, C.K. Etiology of Acute Leukemia: A Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burcu Güleryüz; Ayşe Işık; Murat Gülsoy Synergistic Effect of Mesoporous Silica Nanocarrier-Assisted Photodynamic Therapy and Anticancer Agent Activity on Lung Cancer Cells. Lasers in Medical Science 2024, 39. [CrossRef]

- Othman, E.M.; Fayed, E.A.; Husseiny, E.M.; Abulkhair, H.S. Apoptosis Induction, PARP-1 Inhibition, and Cell Cycle Analysis of Leukemia Cancer Cells Treated with Novel Synthetic 1,2,3-Triazole-Chalcone Conjugates. Bioorganic Chemistry 2022, 123, 105762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, K.; Aktar, A.; Roy, P.; Biswas, B.; Hossain, Md.E.; Sarkar, K.K.; Bachar, S.C.; Ahmed, F.; Monjur-Al-Hossain, A.S.M.; Fukase, K. A Review on Mechanistic Insight of Plant Derived Anticancer Bioactive Phytocompounds and Their Structure Activity Relationship. Molecules 2022, 27, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Hegde, M.; Dey Parama; Sosmitha Girisa; Kumar, A. ; Uzini Devi Daimary; Prachi Garodia; Sarat Chandra Yenisetti; Oommen, O.V.; Aggarwal, B.B. Role of Turmeric and Curcumin in Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases: Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2023, 6, 447–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Kather, F.; Morsy, M.; Sai Boddu; Mahesh Attimarad; Shah, J. ; Pottathil Shinu; Nair, A. Advances in Nanocarrier Systems for Overcoming Formulation Challenges of Curcumin: Current Insights. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 672–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, R.; Veena, M.S.; Wang, M.B.; Srivatsan, E.S. Curcumin: A Review of Anti-Cancer Properties and Therapeutic Activity in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Molecular Cancer 2011, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, F.G.; Sampaio, B.B.; Oliveira, G.; Silva; Julia; Kamila Chagas Peronni; Evangelista, A. F.; Hossain, M.; Dimmock, J.R.; Bandy, B.; et al. The Transcriptome of BT-20 Breast Cancer Cells Exposed to Curcumin Analog NC2603 Reveals a Relationship between EGR3 Gene Modulation and Cell Migration Inhibition. Molecules 2024, 29, 1366–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MaruYama, T.; Hiroyuki Yamakoshi; Iwabuchi, Y. ; Shibata, H. Mono-Carbonyl Curcumin Analogs for Cancer Therapy. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 2023, 46, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Mishra, S.; Surolia, A.; Panda, D. C1, a Highly Potent Novel Curcumin Derivative, Binds to Tubulin, Disrupts Microtubule Network and Induces Apoptosis. Bioscience Reports 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Al-Khazaleh, A.K.; Bhuyan, D.J.; Li, F.; Li, C.G. A Review of Recent Curcumin Analogues and Their Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Activities. Antioxidants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, N.S.; Mishra, S.; Jha, S.K.; Surolia, A. Antioxidant Activity and Electrochemical Elucidation of the Enigmatic Redox Behavior of Curcumin and Its Structurally Modified Analogues. Electrochimica Acta 2015, 151, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, S.; Dhar, G.; Dwivedi, V.; Das, A.; Poddar, A.; Chakraborti, G.; Basu, G.; Chakrabarti, P.; Surolia, A.; Bhattacharyya, B. Stable and Potent Analogues Derived from the Modification of the Dicarbonyl Moiety of Curcumin. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 7449–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiani, A.; Rozzo, C.; Fadda, A.; Delogu, G.; Ruzza, P. Curcumin and Curcumin-like Molecules: From Spice to Drugs. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 21, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Chen, M.; Chen, H.; Wu, N.; Qi, Q.; Jiang, X.; Fang, D.; Feng, Q.; Jin, R.; Jiang, L. The Curcumin Analog Da0324 Inhibits the Proliferation of Gastric Cancer Cells Via HOTAIRM1/MiR-29b-1-5p/PHLPP1 Axis. Journal of Cancer 2022, 13, 2644–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Shao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Chu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, S. Exploration and Synthesis of Curcumin Analogues with Improved Structural Stability Both in Vitro and in Vivo as Cytotoxic Agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2009, 17, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.; E. Shivakumar; Ramachandran, D. Design, Synthesis and Anticancer Evaluation of Substituted Aryl-1,3-Oxazole Incorporated Pyrazole-Thiazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents. Chemical Data Collections 2024, 51, 101127–101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugu, Edukondalu; Reddymasu, Sireesha; Pushpalatha, Kavuluri; Suresh, P.; Rao, C.; Chandrasekhar, C. Rudraraju Ramesh Raju Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Sulfonamide Derivatives of Benzothiazol-Quinoline-Pyrazoles as Anticancer Agents. Chemical Data Collections, 2024; 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, M.; Signorello, M.G.; Russo, E.; Caviglia, D.; Ponassi, M.; Iervasi, E.; Rosano, C.; Chiara Brullo; Spallarossa, A. Structure–Activity Relationship Studies on Highly Functionalized Pyrazole Hydrazones and Amides as Antiproliferative and Antioxidant Agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 4607–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshta, N.M.; Temirak, A.; El-Shahid, Z.A.; Shafiq, Z.; Ahmed, A.F. Soliman Design, Synthesis, Molecular Docking and Biological Evaluation of 1,3,5-Trisubstituted-1H-Pyrazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents with Cell Cycle Arrest, ERK and RIPK3- Kinase Activities. Bioorganic chemistry 2024, 143, 107058–107058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachhot, K.D.; Vaghela, F.H.; Dhamal, C.H.; Vegal, N.K.; Bhatt, T.D.; Joshi, H.S. Water-Promoted Synthesis of Pyrazole-Thiazole-Derivatives as Potent Antioxidants and Their Anti-Cancer Activity: ADMET and SAR Studies. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, C. Eco-Friendly Green Synthesis of N-Pyrazole Amino Chitosan Using PEG-400 as an Anticancer Agent against Gastric Cancer Cells via Inhibiting EGFR. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Animal 2024, 60, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseiny, E.M.; Hamada S., Abulkhair; El-Dydamony, N.M.; Anwer, K.E. Exploring the Cytotoxic Effect and CDK-9 Inhibition Potential of Novel Sulfaguanidine-Based Azopyrazolidine-3,5-Diones and 3,5-Diaminoazopyrazoles. Bioorganic Chemistry 2023, 133, 106397–106397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malebari, A.M.; E. A. Ahmed, H.; Ihmaid, S.K.; Omar, A.M.; Muhammad, Y.A.; Althagfan, S.S.; Aljuhani, N.; A. A. El-Sayed, A.-A.; Halawa, A.H.; El-Tahir, H.M.; et al. Exploring the Dual Effect of Novel 1,4-Diarylpyranopyrazoles as Antiviral and Anti-Inflammatory for the Management of SARS-CoV-2 and Associated Inflammatory Symptoms. Bioorganic Chemistry 2023, 130, 106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ning, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhou, C.; Ding, X. Curcumin Promotes Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells by Inactivating AKT. Oncology Reports 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneman, M.; Dranoff, G. Combining Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapies in Cancer Treatment. Nature Reviews Cancer 2012, 12, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureddin, S.A.; El-Shishtawy, R.M.; Al-Footy, K.O. Curcumin Analogues and Their Hybrid Molecules as Multifunctional Drugs. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 182, 111631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, E.M.; Fayed, E.A.; Husseiny, E.M.; Abulkhair, H.S. The Effect of Novel Synthetic Semicarbazone- and Thiosemicarbazone-Linked 1,2,3-Triazoles on the Apoptotic Markers, VEGFR-2, and Cell Cycle of Myeloid Leukemia. Bioorganic chemistry 2022, 127, 105968–105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.K.; Kumar, S.; Thimmulappa, R.K.; Parmar, V.S.; Biswal, S.; Watterson, A.C. Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel PEGylated Curcumin Analogs as Potent Nrf2 Activators in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2011, 43, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murwanti, R.; Rahmadani, A.; Ritmaleni, R.; Hermawan, A.; Sudarmanto, B.S.A. Curcumin Analogs Induce Apoptosis and G2/M Arrest in 4T1 Murine Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Indonesian Journal of Pharmacy 2020, 31, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, S.K.; Mohd Ali, N.; Akhtar, M.N.; Razak, N.A.; Chong, Z.X.; Ho, W.Y.; Boo, L.; Zareen, S.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Avtar, R.; et al. Induction of Apoptosis and Regulation of MicroRNA Expression by (2E,6E)-2,6-Bis-(4-Hydroxy-3-Methoxybenzylidene)-Cyclohexanone (BHMC) Treatment on MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Liu, B.; Kong, M.; Xi, Z.; Li, K.; Wang, H.; Su, T.; Yao, J.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Cyclic C7-Bridged Monocarbonyl Curcumin Analogs Containing an O -Methoxy Phenyl Group as Potential Agents against Gastric Cancer. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Tao, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, Z.H.; Wu, W.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Zheng, B.; Huang, X.; et al. Curcumin Derivative WZ35 Inhibits Tumor Cell Growth via ROS-YAP-JNK Signaling Pathway in Breast Cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. A Novel Mono-Carbonyl Analogue of Curcumin Induces Apoptosis in Ovarian Carcinoma Cells via Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Molecular Medicine Reports 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manohar, S.; Khan, S.I.; Kandi, S.K.; Raj, K.; Sun, G.; Yang, X.; Calderon Molina, A.D.; Ni, N.; Wang, B.; Rawat, D.S. Synthesis, Antimalarial Activity and Cytotoxic Potential of New Monocarbonyl Analogues of Curcumin. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2013, 23, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.K.; Ferstl, E.M.; Davis, M.C.; Herold, M.; Kurtkaya, S.; Camalier, R.F.; Hollingshead, M.G.; Kaur, G.; Sausville, E.A.; Rickles, F.R.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Curcumin Analogs as Anti-Cancer and Anti-Angiogenesis Agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2004, 12, 3871–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qi, L.; Zheng, S.; Wu, T. Curcumin Induces Apoptosis through the Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptotic Pathway in HT-29 Cells. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B 2009, 10, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Aatif, M.; Ghazala Muteeb; Mir Waqas Alam; Mohamed El Oirdi; Farhan, M. Curcumin and Its Derivatives Induce Apoptosis in Human Cancer Cells by Mobilizing and Redox Cycling Genomic Copper Ions. Molecules 2022, 27, 7410–7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Sun, J.; Sui, Z. The Novel Curcumin Derivative 1g Induces Mitochondrial and ER-Stress-Dependent Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells by Induction of ROS Production. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleicken, S.; Classen, M.; Pulagam V. L., Padmavathi; Ishikawa, T.; Zeth, K.; Steinhoff, H.-J. ; Enrica Bordignon Molecular Details of Bax Activation, Oligomerization, and Membrane Insertion. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 6636–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Haque, A.; Saleem, K.; Hsieh, M.F. Curcumin-I Knoevenagel’s Condensates and Their Schiff’s Bases as Anticancer Agents: Synthesis, Pharmacological and Simulation Studies. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 21, 3808–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, J.J.; Vasava, S.B.; Parmar, K.C.; Chauhan, S.; Sharma, S. Synthesis, Spectral and Microbial Studies of Some Novel Schiff Base Derivatives of 4-Methylpyridin-2-Amine. E-journal of Chemistry 2009, 6, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroth, J.; Nirgude, S.; Tiwari, S.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Mahadeva, R.; Kumar, S.; Karki, S.S.; Choudhary, B. Investigation of Anti-Cancer and Migrastatic Properties of Novel Curcumin Derivatives on Breast and Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugesan, K.; Koroth, J.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Singh, A.; Mukundan, S.; Karki, S.S.; Choudhary, B.; Gupta, C.M. Effects of Green Synthesised Silver Nanoparticles (ST06-AgNPs) Using Curcumin Derivative (ST06) on Human Cervical Cancer Cells (HeLa) in Vitro and EAC Tumor Bearing Mice Models. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 5257–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|

| 5a | 34.36 ± 3.24 |

| 5b | 134.59 ± 1.55 |

| 5c | 8336811.85 ± 494.90 |

| 5d | 36.39 ± 1.78 |

| 5e | 207969.67 ± 86.00 |

| 5f | 0.92 ± 0.00 |

| 5g | 12.44 ± 0.44 |

| 5h | 49.98 ± 10.77 |

| 5i | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| 5j | 11.91 ± 1.48 |

| 5k | 0.58 ± 0.00 |

| 5l | 16.15 ± 0.31 |

| 5m | 46.24 ± 4.18 |

| 5n | 8.97 ± 2.62 |

| 5o | 9.23 ± 0.04 |

| Curcumin | 61.66 ± 2.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).