1. Introduction

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) allow people to control external devices using their brain activities, without the need for nerve or muscle tissue. BCIs that use electroencephalography (EEG) signals as the interface are easy to wear, thus EEG-based BCIs have been widely used for various applications [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Among EEG-based BCIs, steady-state visual evoked potential-based (SSVEP-based) BCI has a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [

3], making it one of the most successful interfaces. However, the performance of SSVEP-based BCIs is degraded in real-life applications, which reduces their usability. Therefore, improving the classification performance can effectively facilitate the transition of SSVEP-based BCIs from laboratory demonstrations to real-life applications.

Brain-computer interface (BCI) is an innovative technology for information communication and control [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. A BCI enables direct communication between the human brain and a computer or external devices. It allows users to control and interact with devices using their thoughts and brain signals. Therefore, BCIs are especially suitable for developing assistive communication systems that can enable people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to communicate without relying on their muscles. In recent years, electroencephalography (EEG), which offers a non-invasive way to measure neural activity, has been extensively used for brain activity recording [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Therefore, developing a non-invasive EEG-based BCI is highly appropriate for real-life applications.

Steady-state visual-evoked potential (SSVEP) is an oscillatory stimulus-response that is evoked by repetitive stimuli with a constant frequency, and it is used to elicit a brain response in the primary visual cortex. These responses are recorded in the EEG, and the frequency of the response matches the frequency of the flickering stimulus. Compared to other BCIs, SSVEP-based BCI is a successful interface due to its ease of recording and high signal-to-noise ratio [

3]. Therefore, SSVEP-based BCI has been applied to various applications, such as visual spelling [

20,

21], and decoding user intent to operate assistive devices [

22,

23]. However, the accuracy of SSVEP-based BCIs plays a crucial role in their acceptance, and therefore, improving their accuracy is very important for users to accept these BCIs.

A suitable representation of the SSVEP signal is crucial for classification tasks as it can significantly improve the system's performance. Multi-domain features (MDFs) are a suitable representation of the SSVEP signal as they can precisely represent its characteristics. Previous studies have used MDFs to increase classification performance for various applications. Yu et al. [

24] applied the spatial, frequency, and compression domains to improve classification performance for JPEG images. Chung et al. [

25] and Baek et al. [

26] used time and frequency domains to enhance the performance of blood pressure prediction. Cao et al. [

27] selected common spatial pattern, phase-locking value, Pearson correlation coefficient, and transfer entropy as the MDFs to improve the performance of the motor-modality-based BCI. The results showed that the MDFs are very useful, but the computational complexity is high in computing the features. Thus, selecting an MDF with low computational complexity is very useful for developing BCIs. Li et al. [

28] used MDFs to diagnose faults in rolling element bearings. The experimental results of these studies showed that MDFs outperform single-domain features. Therefore, using MDFs can significantly improve the performance of SSVEP-based BCIs.

Recently, multi-task learning (MTL), which leverages shared representation to exploit commonalities across tasks, has been successfully used in many deep learning-based applications. Chuang et al. [

8] used MTL to improve the performance of SSVEP-based BCIs by jointly performing signal enhancement and classification tasks. However, MTL frameworks typically require a large amount of training data. To reduce the need for training data, Khok et al. [

29] proposed an MTL block that performs group convolutions. Results showed that this proposed MTL block outperforms fully connected and traditional convolutional layers. Therefore, integrating an MTL block can increase the accuracy of an SSVEP-based BCI.

In this study, an SSVEP-based BCI with MDFs and MTL is develop to help people communicate with others. To precisely represent the characteristics of the SSVEP signal, the SSVEP signals in time and frequency domains are selected as the multi-domain features and used as inputs for the neural network. To effectively extract the embedding features, convolutional neural networks are separately used for time and frequency domains. The embedding features for the time and frequency domains are then fused using an element-wise addition operation and batch normalization. To find the discriminative embedding features for classification, a sequence of convolutional neural networks is adopted. Finally, to correctly detect the corresponding stimuli, the MTL block is used.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The proposed SSVEP-based BCI with multi-domain features and MTL is described in

Section 2.

Section 3 then conducts a series of experiments to evaluate the performance of our approach.

Section 4 presents the conclusions and provides recommendations for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

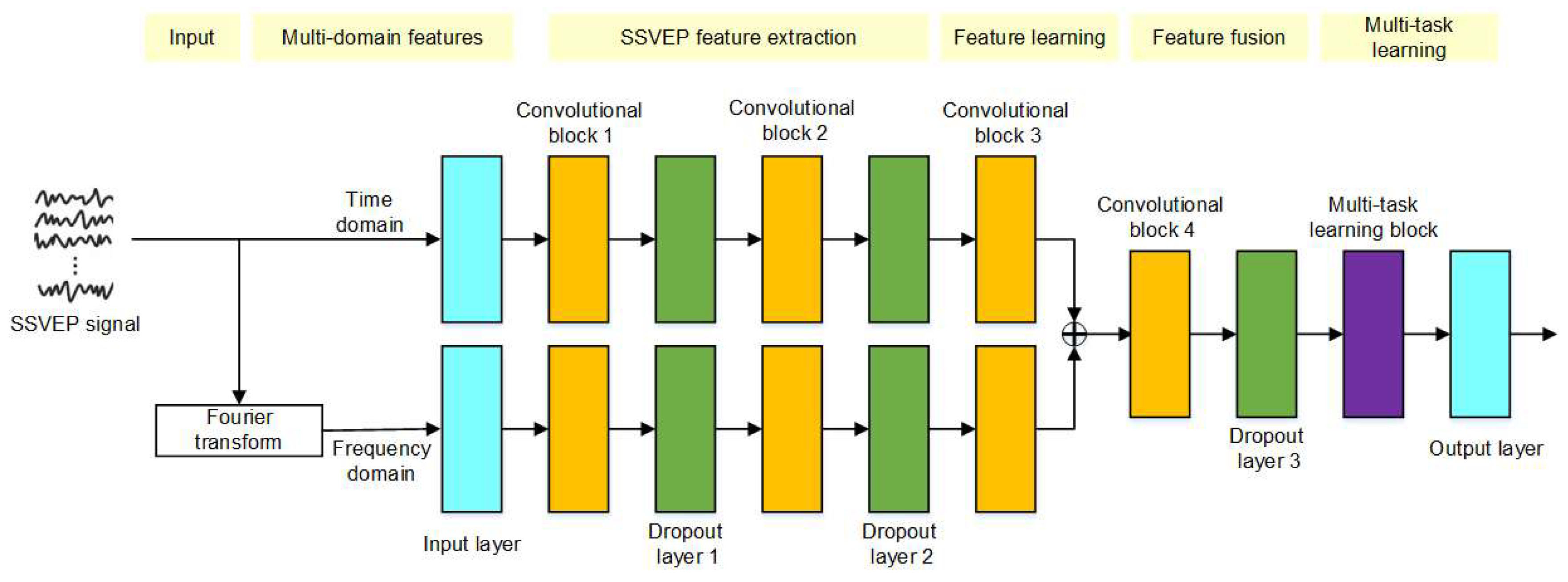

The proposed neural network architecture for SSVEP-based BCIs with MDFs and MTL is presented in

Figure 1. First, multi-domain features, including time and frequency domains, are utilized to accurately represent the characteristics of the SSVEP signal. Second, a convolutional layer that convolves across the channel dimension is employed to fuse information from multiple channels. A convolution layer is then used to extract embedding features from the SSVEP signals in dome and frequency domain. Third, the multi-domain features are fused by an element-wise addition operation and batch normalization. Fourth, embedding features are learned using a sequence of convolutional layers. Finally, an MTL-based convolutional layer is employed to make the final decisions. This process is described in detail in the following.

2.1. Multi-Domain Features

In this study, the SSVEP signal in both time and frequency domains are used as the multi-domain features. The discrete Fourier transform is used to transform the SSVEP signal from the time domain, x={x

0, x

1,…, x

N}, to the frequency domain, X={X

0, X

1,…, X

N}, and defined as

Since the discrete Fourier transform can select any analysis window length, the feature lengths for different domains can be made the same. This simplifies the process of extracting embedding features in different domains.

2.2. Neural Network Structure for Feature Extraction

Two convolutional blocks are designed for extracting features from the SSVEP signal. Each block consists of a convolution layer, a batch normalization layer, and an exponential linear unit. For a convolutional block, let z be an input, which is the output of previous block, and then the convolution,

u(), of the input with kernel,

w, can be defined as following

where * is the convolution operation. The activation function,

, is exponential linear unit and defined as

where

is a hyperparameter to be tuned with the constraint

. A dropout layer, which is a mask that nullifies the contribution of some neurons, is also included in each block to reduce the number of parameters in the neural network.

The first block is responsible for extracting embedding features from the time- or frequency-domains of the SSVEP signal. The process of the first block is similar to extract features by using spectral and cepstrum processing, and its first convolutional layer has a kernel size of 1xL1. The convolutional layer in the second block convolves across the dimension of EEG channels, with a kernel size of L2x1 and then it performs spatial filtering.

2.3. Neural Network Structure for Feature Learning

The third convolutional block is designed to capture temporal patterns in the previous layer outputs, using various dilation configurations. It includes a convolutional layer, a batch norm layer, and an exponential linear unit. Dilation convolutions can increase the receptive field and perform feature learning with a smaller kernel size, allowing for the use of a smaller model to identify appropriate embedding features, which can potentially improve performance.

2.4. Neural Network Structure for Feature Fusion

Comparing the element-wise addition operation to the concatenation operation, the concatenation operation would increase the dimensionality of the embedding features. Considering the computational complexity of the neural network, the element-wise addition operation is chosen to fuse the embedding features in the time and frequency domains. Once the fused features are obtained, a convolutional block, whose neural network structure is the same as the third convolutional block, is used to learn discriminative embedding features.

2.5. Neural Network Structure for Multi-Task Learning

Each classification target is considered as an individual task and is processed by an MTL block, which uses group convolutions to perform separate convolutions within a single convolutional layer. This allows the same model architecture to be easily scaled to any number of tasks. First, the output of the previous layer is expanded by M times using concatenation, where M is the number of classification targets, to match the input size of the MTL block. Second, group-wise convolution is applied to split the inputs into M different groups of weights, where each group learns each classification target separately. Finally, the results of M convolutions are concatenated to produce N binary output targets. As a result, the MTL block can be trained for multiple tasks in parallel on a single GPU.

3. Results and Discussion

In this study, a user-independent SSVEP-based BCI is considered for practical applications. Therefore, leaving-one-participant-out cross-validation, where the number of folds equals the number of participants in the dataset, was adopted to evaluate our proposed approach. Thus, a subject is left as the testing data and other subjects are treated as the training data.

The hyperparameters of the proposed neural network with MDFs and MTL is shown in

Table 1. To train our proposed neural network structure, the Adam algorithm was selected as the optimizer, which is an adaptive learning rate optimization technique. The learning rate, epoch, batch size, and early stopping were set to 0.001, 100, 64, and 10, respectively. The results of our proposed SSVEP-based BCI are detailed in the following section.

3.1. The Ssvep Signal Dataset

In this study, an open-access dataset, HS-SSVEP, which was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tsinghua University, is used to train and evaluate the proposed approaches [

21]. In this dataset, a 40-target BCI speller is used to design an offline BCI experiment, which contains 40 characters including 26 English alphabets, 10 digits, and 4 symbols. The 40 stimuli are flickered at frequencies between 8-15.8 Hz with an interval of 0.2 Hz and coded using a joint frequency and phase modulation approach [

30].

In this dataset, 35 healthy subjects (17 females and 18 males) aged between 17-34 years (mean age: 22 years) were asked to participate in the offline BCI experiment. For each subject, each target frequency was presented 6 times, and then 240 trials were collected. Each trial lasted for 6 seconds, in which the first and last 0.5 seconds were used for visual cues and rest, respectively.

The EEG signal was recorded using 64 channels at a 1k Hz sampling rate. Out of the 64 electrodes, eleven channels from the occipital and parietal areas, namely Pz, PO-3/4/5/6/7/8/z, and O-1/2/z, were used. To reduce storage and computation costs, the collected EEG signal was simply downsampled to 250 Hz and filtered using a 6th-order Butterworth filter between 1 Hz and 40 Hz. Then, the filtered EEG signals were segmented and the first and last 0.5 seconds were removed. The first dt seconds was selected as a data epoch, which contains 250 dt time samples by 11 channels. In this study, the dt is examined by using 4, 3, 2, and 1.

3.2. The Results of Ssvep-Based Bci with Multi-Task Learning

The performance of the neural network using different domain features and MTL examined in this section. The results of the proposed approach were compared with those using only a convolutional layer and a fully connected layer as the last layers of the neural network. The experimental results are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3 for using time and frequency domain features, respectively. The neural networks with using convolutional layer, fully connected layer, and multi-task learning as the last layer are denoted as C, FC, and MTL, respectively. The results show that the accuracy of the neural networks using time-domain features is higher compared to those using frequency-domain features. Hence, the time-domain feature is more suitable for neural network approaches.

In addition, accuracy decreases when the duration of the SSVEP signal is decreased. Performance is too low for practical SSVEP-based BCIs when the input SSVEP signal duration is 1 second. While increasing the duration of the input SSVEP signal improves performance, it also increases the response time of the SSVEP-based BCI, which may be undesirable for users. Therefore, improving the performance of an SSVEP-based BCI with a short input signal duration would be very useful for practical applications.

Table 2 and

Table 3 show that using MTL as the last layer in the neural network results in better performance than using the convolutional or fully connected layer. The accuracy can be significantly improved when the duration of the input SSVEP signal is 1 second. The improvement rates for using time and frequency domain features are 48.22% and 67.95%, respectively, compared to the convolutional layer. The improvement rates for using time and frequency domain features are 53.08% and 69.59%, respectively, compared to the fully connected layer. This demonstrates that using MTL as the last layer is effective in modeling the embedded features extracted from the 1-second SSVEP signal. Additionally, the response time of MTL with the 1-second duration is more practical for SSVEP-based BCIs.

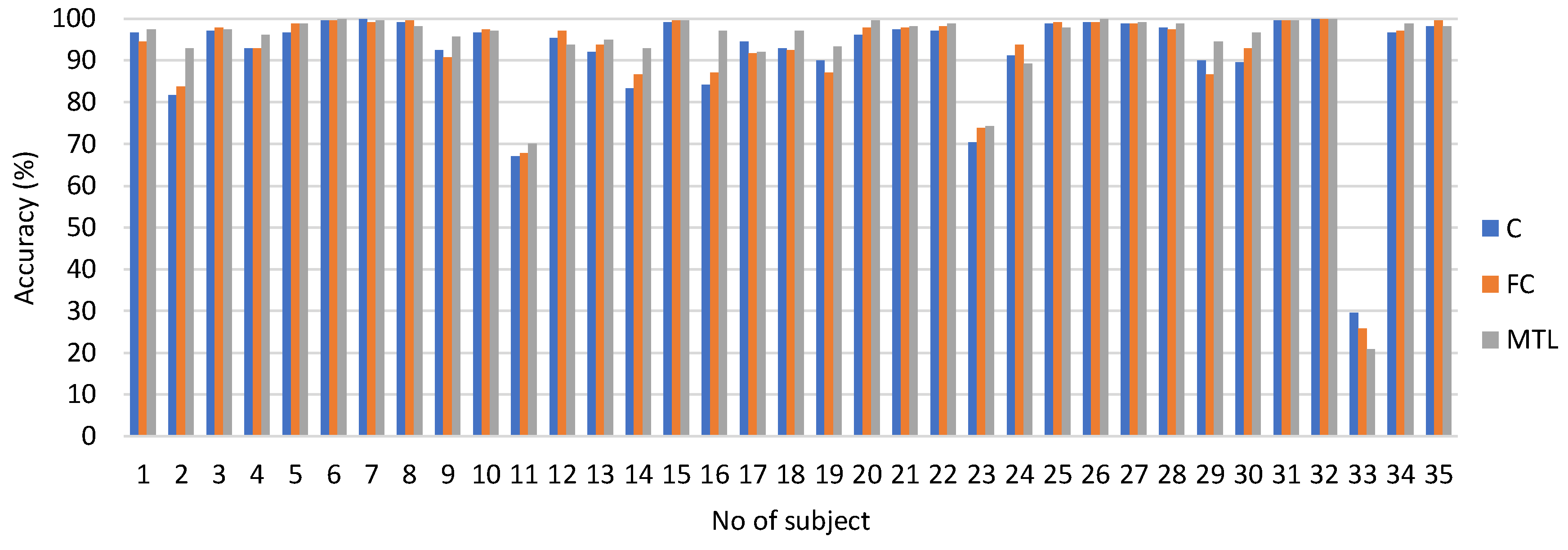

In

Table 2 and

Table 3, the standard deviation is greater than 10%. To examine this further, the accuracy for each subject using a 4-second SSVEP signal is shown in

Figure 2. The accuracy for subjects 11, 23, and 33 is below 80%, which greatly contributes to the higher standard deviation. This indicates that the SSVEP signals for some subjects cannot be effectively evoked. As a result, some individuals may not be able to communicate with others using SSVEP-based BCIs, which limits its practical application.

3.3. The Results of Ssvep-Based Bci with Multi-Domain Features

The SSVEP-based BCI using multi-domain features is examined in this section. Typically, the concatenation operation is used to combine multi-domain features, but it increases the model size and computational complexity of the neural network. To reduce this complexity, the concatenation operation was compared with the element-wise addition operation. Moreover, a feature learning layer (the convolution block 3 in

Figure 1) was designed before (MDF1) and after (MDF2) the concatenation/element-wise addition operation.

The experimental results of MDF1 and MDF2 are shown in

Table 4. The performance of the neural network using element-wise addition as the fusion operation is slightly better than when using the concatenation operation. Additionally, the number of parameters in the neural network using element-wise addition is lower than that in the neural network using concatenation. Therefore, the element-wise addition operation is more suitable for combining multi-domain features.

In

Table 5, the performance of MDF2 is slightly better than that of MDF1. For MDF2, the embedding features are learned independently in the time and frequency domains, and then fused using the element-wise addition operation. The convolutional layer processes the embedding feature, making it more meaningful to represent the characteristics of each domain.

Comparing the results in

Table 2 and

Table 3, the performances of MDF1 and MDF2 are higher than that of a neural network with MTL that uses either time or frequency domain features.

Table 5 provides a detailed analysis of the improvement rates, showing that fusing different domain features can effectively enhance the performance of SSVEP-based BCIs. Moreover, the minimum improvement rate of the SSVEP-based BCIs, when using input SSVEP signal durations of 4s, 3s, 2s, and 1s, are 24.2%, 40.6%, 43.5%, and 9.4%, and 31.5%, 26.9%, 31.5%, and 35.3% for using time and frequency domain features, respectively. Therefore, fusing different domain features is an effective approach for improving the performance of SSVEP-based BCIs.

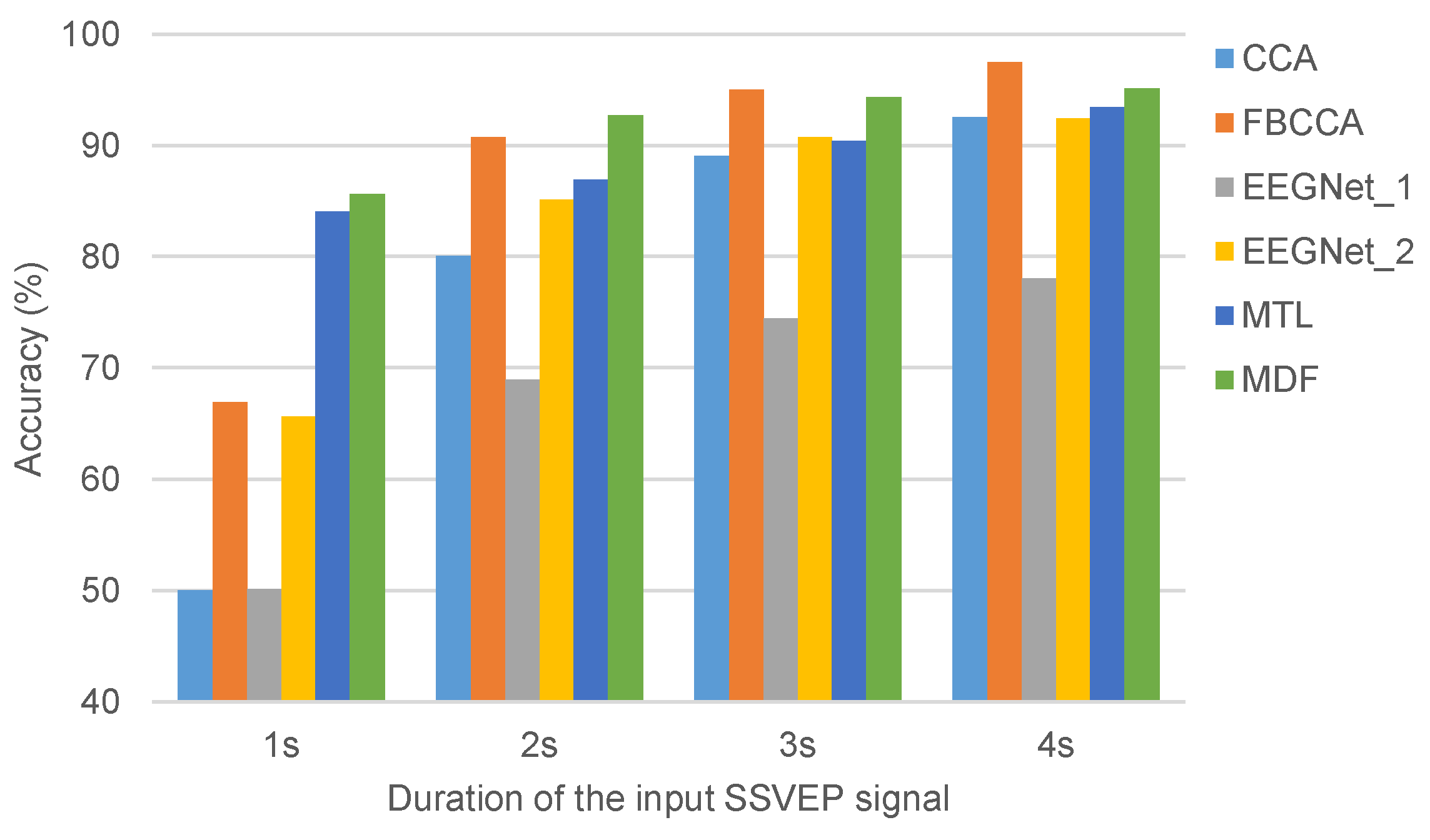

3.4. The Results Compared with Other Approaches

In this section, the statistical approaches including canonical correlation analysis (CCA), filter bank CCA (FBCCA), and task-related component analysis (TRCA) [

21] and the neural network approaches including EEGNet [

31] and MTL [

29] were selected to compare with the proposed approaches. For EEGNet, we designed two neural network structures, which differ in that the second convolutional block is either a traditional convolutional operation (referred to as EEGNet_1) or a convolutional operation across the channel dimension (referred to as EEGNet_2). The experimental results of both the statistical and neural network approaches are shown in

Figure 3. Our findings indicate that the convolutional operation across the channel dimension, as used in EEGNet_2, can effectively fuse information from different channels and obtain more precise embedding features for representing the input SSVEP signal. Furthermore, our proposed approach, MDF, outperforms the selected neural network-based approaches.

If the input SSVEP signal has a short duration, the SSVEP-based BCI can offer a quick response time and can be used for developing real-time systems. In

Figure 3, neural network-based approaches outperform statistical approaches when the duration of the input SSVEP signal is 1s. Moreover, the proposed MDF approach achieves the best performance, making it an excellent option for practical applications.

Statistical analysis typically requires a longer duration for the input SSVEP signal to achieve acceptable performance. As such, the duration of an input SSVEP signal should be larger than 3s. However, this is not suitable for developing a real-time system and may be unacceptable for users. Therefore, it is crucial for neural network-based approaches to increase the precision of representing an SSVEP signal with a long duration. Researchers may employ multi-task learning with non-classification tasks to extract meaningful embedding features, potentially leading to improved performance.

Finally, the proposed approach was used to compare it with state-of-the-art neural networks, including a transformer-based deep neural network model (denoted as SSVEPformer) [

18] and a group depth-wise convolutional neural network (denoted as GDNet-EEG) [

19]. The duration of the input SSVEP signal for SSVEPformer and GDNet-EEG is 1 second. The accuracies for SSVEPformer and GDNet-EEG are 83.16% and 84.11%, respectively. Therefore, our proposed approach (85.6%) outperforms both SSVEPformer and GDNet-EEG.

4. Conclusions

This study developed an SSVEP-based BCI with MDFs to enable people to communicate with others or devices. The multi-domain features can precisely represent the characteristics of the SSVEP signal. For multi-channel SSVEP-based BCIs, a convolutional operation across the channel dimension can effectively fuse information from different channels. Additionally, the element-wise addition operation successfully fuses time and frequency domain features. The sequence of convolutional neural networks effectively extracts discriminative embedding features, and MTL is used to make correct final decisions. Experimental results show that the proposed SSVEP-based BCI with MDFs and MTL outperforms EEGNet and MTL. Moreover, compared to statistical approaches, the proposed approach achieves higher accuracy when the duration of the SSVEP signal is 1s or 2s. When the duration of the input SSVEP signal is 3s or 4s, the performance of the proposed approach is similar to that of statistical approaches. The limitation of the proposal is that the SSVEP signals for some subjects may not be effectively evoked. In the future, multi-task learning with non-classification tasks can be adapted to extract meaningful embedding features, thereby improving BCI system performance. Therefore, the proposed approach can be used to develop a practical SSVEP-based BCI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-J. Chen and C.-M. Wu; Data curation, Y.-J. Chen, and C.-M. Wu; Formal analysis, Y.-J. Chen and C.-M. Wu; Investigation, Y.-J. Chen, S.-C. Chen and C.-M. Wu; Methodology, Y.-J. Chen and C.-M. Wu; Project administration, C.-M. Wu; Resources, Y.-J. Chen and C.-M. Wu; Software, Y.-J. Chen; Supervision, C.-M. Wu; Validation, Y.-J. Chen, S.-C. Chen and C.-M. Wu; Visualization, C.-M.Wu; Writing—original draft, Y.-J. Chen, S.-C. Chen and C.-M. Wu; Writing—review and editing, Y.-J. Chen, and C.-M. Wu.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Higher Education Sprout of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, and the other was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, Grant number NSTC 113-2221-E-218-006, NSTC 113-2221-E-218-005, and NSTC 113-2221-E-167-005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

National Cheng Kung University Human Research Ethics Committee Approval No. NCKU HREC-F-113-510-2. Date: 19 Sep. 2023 and No. NCKU HREC-F-113-512-2. Date: 23 Sep. 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all study participants and members of the research team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feng, J.; Yin, E.; Jin, J.; Saab, R.; Daly, I.; Wang, X.; Hu, D.; Cichocki, A. Towards correlation-based time window selection method for motor imagery BCIs. Neural Networks 2018, 102, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P. L. C.; Jutten, C.; Congedo, M. Riemannian Procrustes Analysis: Transfer Learning for Brain–Computer Interfaces. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 2018, 66, 2390–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolás-Alonso, L. F.; Gil, J. Brain Computer Interfaces, a Review. Sensors, 2012, 12, 1211–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, S.-C.; Zaeni, I. A. E.; Wu, C.-M. Fuzzy Tracking and Control Algorithm for an SSVEP-Based BCI System. Applied Sciences, 2016, 6, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-H.; Kwak, N.-S.; Guan, C.; Lee, S.-W. Decoding Movement-Related Cortical Potentials Based on Subject-Dependent and Section-Wise Spectral Filtering. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 2020, 28, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisaen, R.; Autthasan, P.; Mingchinda, N.; Leelaarporn, P.; Kunaseth, N.; Tammajarung, S.; Manoonpong, P.; Mukhopadhyay, S. C.; Wilaiprasitporn, T. Decoding EEG Rhythms During Action Observation, Motor Imagery, and Execution for Standing and Sitting. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2020, 20, 13776–13786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, P.-C.; Chen, S.-C.; Wu, C.-M. Denoising Autoencoder-Based Feature Extraction to Robust SSVEP-Based BCIs. Sensors, 2021, 21, 5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.-C.; Lee, C.-C.; So, E. C.; Yeng, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-J. Multi-Task Learning-Based Deep Neural Network for Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces. Sensors 2022, 22, 8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovinović, I.; Vrankić, M.; Vlahinić, S.; Šverko, Z. Design considerations for the auditory brain computer interface speller. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2022, 75, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, H.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, R.; Yin, F. A parallel multi-scale time-frequency block convolutional neural network based on channel attention module for motor imagery classification. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2022, 79, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R. A.; Vasilakos, A. V. Brain computer interface: control signals review. Neurocomputing, 2016, 223, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aricò, P.; Borghini, G.; Flumeri, G. D.; Sciaraffa, N.; Babiloni, F. Passive BCI beyond the lab: current trends and future directions. Physiological Measurement 2018, 39, 08TR02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panachakel, J. T.; Ramakrishnan, A. G. Decoding Covert Speech From EEG-A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xie, S. Q.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Multi-Objective Optimization-Based High-Pass Spatial Filtering for SSVEP-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Fan, C.; Wang, Z.; Hou, L.; Wang, H.; Li, G. Alertness-based subject-dependent and subject-independent filter optimization for improving classification efficiency of SSVEP detection. Technology and Health Care, 2020, 28, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C. Temporal-spatial-frequency depth extraction of brain-computer interface based on mental tasks. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2020, 58, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhi, K.; Hoque, N.; Dutta, S. K.; Hussain, Md. I. An efficient EEG signal classification technique for Brain–Computer Interface using hybrid Deep Learning. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2022, 78, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Xu, P.; Guan, C. A transformer-based deep neural network model for SSVEP classification. Neural Networks, 2023, 164, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Z.; Cheng, W.; Li, M.; Zhu, R.; Duan, W. GDNet-EEG: An attention-aware deep neural network based on group depth-wise convolution for SSVEP stimulation frequency recognition. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-J.; Lim, J.-H.; Jung, Y.-J.; Choi, H.; Lee, S. W.; Im, C.-H. Development of an SSVEP-based BCI spelling system adopting a QWERTY-style LED keyboard. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 2012, 208, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, X.; Gao, S. A Benchmark Dataset for SSVEP-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 2016, 25, 1746–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, N.-S.; Müller, K.-R.; Lee, S.-W. A convolutional neural network for steady state visual evoked potential classification under ambulatory environment. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12, e0172578–e0172578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, K. S.; Pelayo, P.; Anil, D. G.; George, K. An SSVEP based brain computer interface system to control electric wheelchairs. 2018 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Houston, TX, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, I.-J.; Nam, S.-H.; Ahn, W.; Kwon, M.-J.; Lee, H.-K. Manipulation Classification for JPEG Images Using Multi-Domain Features. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 210837–210854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.-C.; Lee, C.-C.; Yeng, C.-H.; So, E. C.; Chen, Y.-J. Attention Mechanism-Based Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Neural Networks to Electrocardiogram-Based Blood Pressure Estimation. Applied Sciences, 2021, 11, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-H.; Jang, J.-Y.; Yoon, S. End-to-End Blood Pressure Prediction via Fully Convolutional Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 185458–185468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, H.; Jia, J.; Chen, S.; Dong, Y.; Fan, C.; Albuquerque, V. H. C. d. An Effective Fusing Approach by Combining Connectivity Network Pattern and Temporal-Spatial Analysis for EEG-Based BCI Rehabilitation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 2022, 30, 2264–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Yan, C.; Wang, W.; Babiker, A.; Wu, L. Health Indicator Construction Based on MD-CUMSUM With Multi-Domain Features Selection for Rolling Element Bearing Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Access, 2019, 7, 138528–138540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khok, H. J.; Teck Chang Koh, V.; Guan, C. Deep Multi-Task Learning for SSVEP Detection and Visual Response Mapping. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, P.; Cheng, K.; Yao, D. Multivariate synchronization index for frequency recognition of SSVEP-based brain–computer interface. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 2013, 221, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawhern, V. J.; Solon, A. J.; Waytowich, N. R.; Gordon, S. M.; Hung, C. P.; Lance, B. J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering, 2018, 15, 56013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).