1. Introduction

The frontiers of the current scientific research on biological systems—while observed from the computational point of view—are pointing towards the possibility of the existence of a common denominator, and hence, towards a possibility to find a unified description of functioning biological systems.

It has become gradually transparent that there are several from-the-first-sight independent streams of research within biology [

1,

2], biochemistry [

3,

4,

5], quantum biology [

6] and quantum field theory, interactions of quantum systems with electromagnetic fields [

3,

4,

5], morphology driven by electric potentials present on cellular membranes [

7,

8,

9,

10], and complex systems describing biological systems that they all are converging towards a common denominator. It is still rather unclear how to exactly pinpoint this common denominator. According to the current state-of-the-art of the above-mentioned research areas, massively-parallel computational descriptions have a relatively big potential to become a unifying descriptive tool [

11,

12,

13] that might bring deeper mathematical and computational insights into the inner workings of biological systems.

From recent research presented within the above-provided research areas, it is becoming obvious that the importance of the inherent massive-parallelism operating within all living systems is still highly underestimated. That is why it is important, according to the current understanding of the author, to focus our theoretical attention to the solution of well-defined massive-parallel problems that are motivated by real biological systems, in the ways as is demonstrated in this publication.

1.1. Natural Phenomena

When natural phenomena are observed through the lenses of complex systems, using the concept of multiple scales, the ground scale encompass all physics, higher scales encompass chemistry, biochemistry, and finally the top scales encompass cells, tissues, organs, and entire living systems. Obviously, the most complicated phenomena are observed in living systems where self-organization (SO), self-assembly, and emergence (EM) operate on several distinct scales utilizing different emergent entities and rules governing their mutual interactions. Each scale utilizes a completely different matrix and a set of micro-processes to reach its fully functional state. Functional-levels range at different scales: atoms, molecules, biomolecules, organelles, cells, tissues, organs, bodies, and ecosystems. Each functional level utilizes specific interactions: atomic bonds, chemical bonds, cell signaling, etc.

1.2. Descriptions of Natural Phenomena

There exists the central question, “What drives natural phenomena to operate as they do operate? “ Despite many centuries of development of descriptive mathematical tools, living systems are still evading their formal description.

It is well known that descriptions of natural phenomena underwent dramatic changes over past centuries. Original descriptive methods were quite primitive. With development of mathematics and especially with the incorporation of computers, advanced methodologies were developed; for details see

Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of natural phenomena underwent a dramatic development over many centuries; it went from the simplest descriptions (relationships) to more complicated (analysis & calculus), and now it reached the highest known level (complex systems).

Table 1.

Description of natural phenomena underwent a dramatic development over many centuries; it went from the simplest descriptions (relationships) to more complicated (analysis & calculus), and now it reached the highest known level (complex systems).

| Different levels of description of natural phenomena |

|---|

| Level |

Description |

|

| Pre-scientific |

In old times, phenomena were believed to be caused by supernatural forces. |

|

| Relationships |

Later, gradually, numbers, linear and non-linear dependencies, and functions were adopted. |

|

| Complicated dependencies |

Calculus, differential equations, and functionals followed. |

|

| Complex systems |

Currently, understanding of massive-parallelism of multi-component systems represents the most advanced methodology in description of natural phenomena. |

|

| Complicated dependencies: described in details |

| Analysis |

Statistics & Probability |

|

| functions |

statistics |

|

| equations |

probability |

|

| calculus |

AI, ML, DM, ANN |

|

| Complex systems: described in details |

| Level |

Type of process |

Mode |

| 1 |

Self-assembly |

done once |

| 2 |

Self-organization, replication, self-replication, and emergence |

continuous, far-from-equilibrium |

| 3 |

Emergent information processing |

continuous & capable of computing |

1.3. Current Knowledge of Root Processes That Creates Life

The contemporary biological research is starting to address inherent massive-parallelism, self-organization, self-assembly, and emergence, and from those the resulting robustness of living systems directly. Currently, there are several distinct paths of attack to gain knowledge of the root processes that are driving living structures to become and stay alive.

Gradually, disparate research streams that are originating in distant scientific areas are converging to a common denominator. Those fields are represented not only by quantum field theory [

2], quantum mechanics, chemistry, electrochemistry [

3,

4,

5], biochemistry [

1], biology, and theory of computation [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Surprisingly, theory of computation is gradually discovering computational methods, which are capable of capturing the functioning of massively-parallel computations, that describes self-organization, self-assembly, and emergence from the first principles and, importantly, confirm them experimentally [

11,

12,

13]. Cellular biocomputing [

14], a relatively novel research field, is sharing common ground with emergent information processing methodology [

11,

12,

13] that deserves deeper studies, such as the one presented in the research presented in this computational research paper.

The importance of electromagnetic fields in the catalysis of biomolecules from abiotic chemicals [

3,

4,

5] and quantum field properties of synchronized domains present in water [

6] is uncovered in addition to already gained knowledge. Additionally, water acquires its fourth state, beside gaseous, liquid, and solid, near certain surfaces (called the exclusion zone (EZ) water), which is important in promoting many chemical reactions within cells, including propelling blood flow through micro-vessels [

15,

16,

17,

18]. In the light of this research, emergent information processing seems to be a promising computational approach that will assist us in uncovering the hidden processes and properties of biological systems in at least several of their lower-level functional layers [

11,

12,

13].

From the above-covered information, it follows that biological systems are utilizing more advanced computations than can be realized by Turing machine [

19,

20], which itself is the theoretical model of all currently used silicon-based computers. To uncover the capabilities of biological systems, a carefully designed tasks were defined and have been studied over many decades; see

Section 3 for details.

1.4. Selected Fundamental Tasks in Massively-Parallel Systems

Biological observations suggest that cells, tissues, organs, and bodies utilize massively-parallel computations (MPCs) to achieve desired goals. To decipher the exact functioning of such systems is extremely hard. That is why over the decades, several quite difficult problems, yet simultaneously easy to define computationally within various MPCs systems were recognized. Two important and often solved ones are represented by the density classification task (DCT) and firing-squad synchronization problem (FSSP) .

That is why deep understanding of the DCT and FSSP can be utilized in development of artificial MCSs that would be capable of solving problems within highly decentralized systems. Consequently, this understanding will help us to perform the reverse engineering of real living systems.

1.5. Effects of Quantum Phenomena and Electromagnetism on Biological Systems

Important fields of research, which are relevant to this research presented here, are quantum biology and electromagnetism in biological systems. Therefore, they are briefly discussed here.

The latest research is pointing towards the possibility that quantum biology is going to play the pivotal role in our understanding of functioning of biological systems in the near future [

6]. It is hypothesized that microtubules might serve as quantum computing environment. According to this research stream, microtubules are protecting their inner part from quantum decoherence and hence they can perform quantum computations within living systems at the body temperature [

21,

22].

Feedback loops [

1] play the crucial role in the functioning of all living systems in existence. Without them, life ceases to exist instantly. They are often facilitated by chemical signals; yet they utilize electromagnetic and possibly even quantum-level phenomena.

It is a well-known fact that mere chemistry is unable to explain rising of RNA without preexisting RNA or DNA and some proteins [

2]. That is the moment where it is important to mention by Larson’s et al. found catalysis of prebiotics that is facilitated by certain segments of EMG spectrum of sunlight [

3,

4,

5].

2. Brief Review of Known Emergent Systems

Emergence is operating within many natural phenomena across the entire spectrum of scientific disciplines, which are utilizing the principally the same mechanism of operation. Yet, both theoretical and computational understanding of emergence are still in their infancy. We need a well-defined MPC system that is easy to understand emergence. This leads us directly to CAs that are representing a well-known testbed of complex systems research and substantially contributes to their understanding. To understand CAs, an introduction into cellular automata modeling of massively-parallel computing systems is provided in the reviews of CSs within biomedicine [

23] and EIP in CSs [

11]. Additionally, the position paper [

11] serves as a thorough introduction to EIP, which should be followed by reading the application of EIP in AI and biological intelligence [

24]. Introduction into agent-based modeling (ABM)—another broad area of complex systems research—can be found, e.g., in [

25] with many well-documented examples.

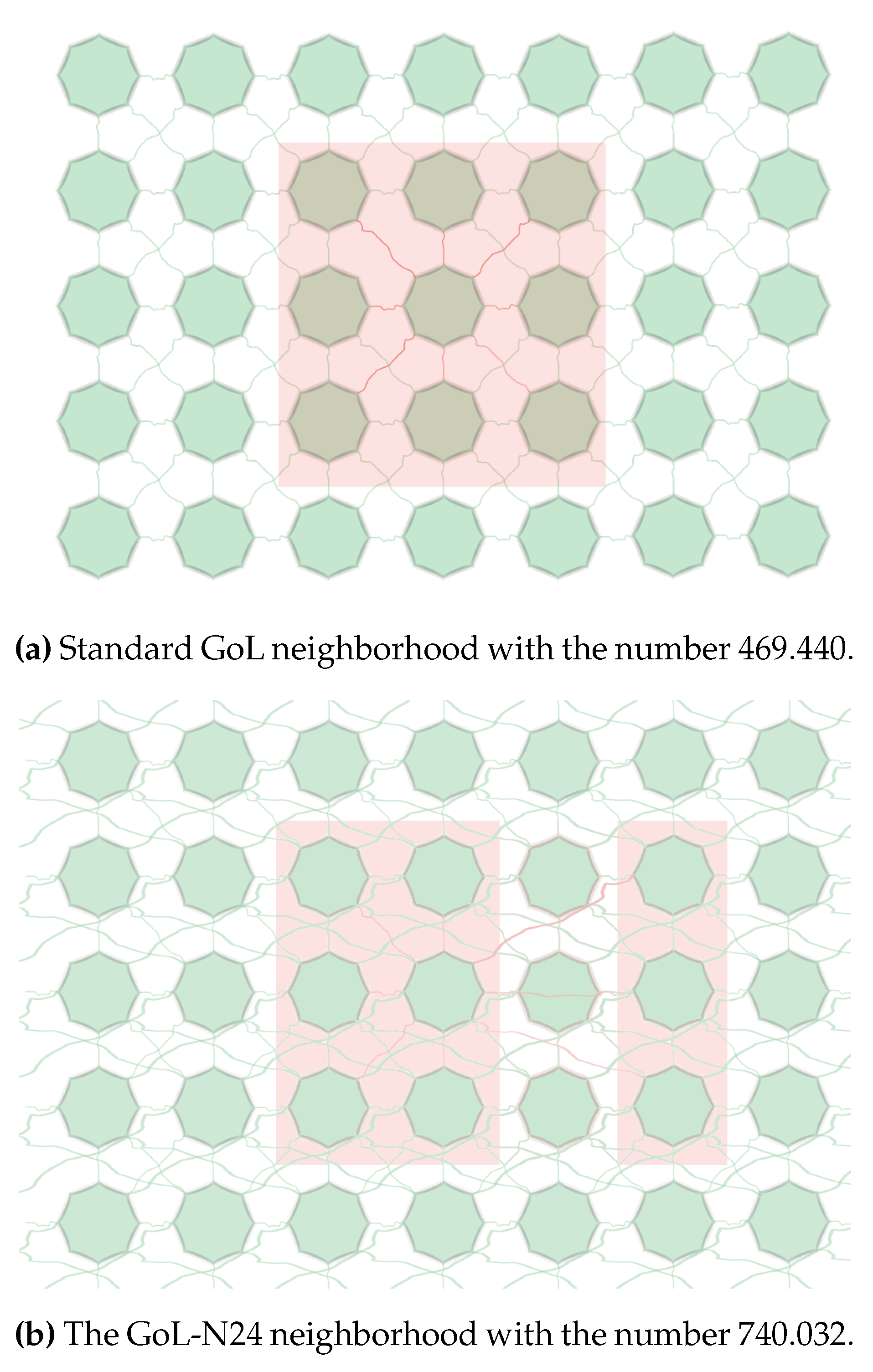

EIP is a descendant of ’Game of Life’ (GoL) cellular automaton as defined by John H. Conway [

26] in his seminal research. EIP is relaxing the fixed shape of GoL neighborhood and allowing choose eight neighbors from 24 possible positions within an extended

neighborhood (obviously the central cell is excluded) instead of the original eight nearest neighbors of the original GoL.

Many vital examples of emergence are covered in the book [

27], which is written in a way that is accessible to both scientists and laymen. This book is helpful in fast and effective entering the broad field of emergence. More specialized examples of emergence are covered in biology and science [

23] and a very broad number of physical, biological, QM, and computational examples [

11] (see citations there).

The motivation to work on advanced emergent computational systems and on the development of fast solutions of synchronization problems heavily rely on the experience gained, and the observations made during development of the massively-parallel computational model describing dynamic recrystallization [

28,

29] in 1999, where some possible local rules were tested. The original idea to carry on research on EIP originates in that period of time. Additionally, development of the EIP Python program GoL-N24 [

30] in the years 2022–2024 and its use to scan the vast space of all possible neighborhoods led to the realization of why the topology of neighborhoods is fundamental in understanding of emergence and self-organization. This area still remains under-researched and deserves higher attention from a broad research community.

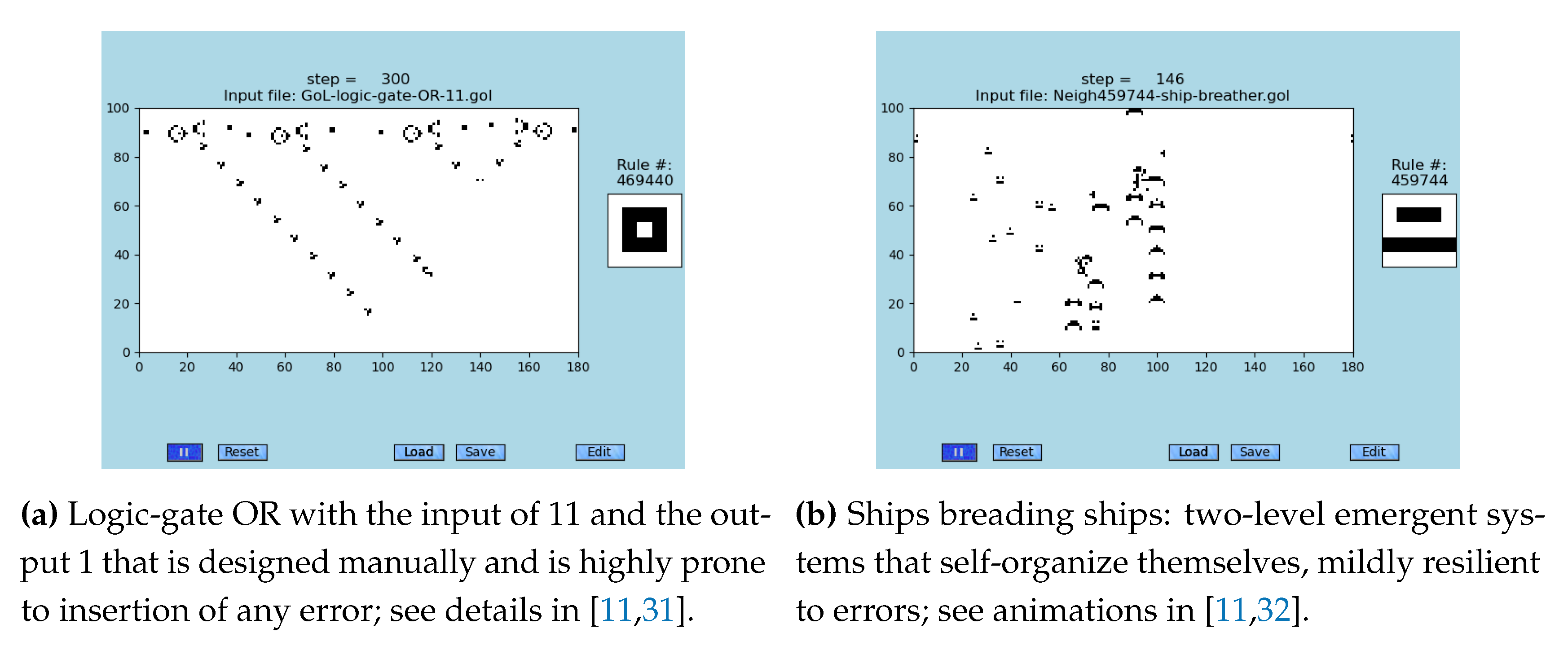

Two examples of emergent systems observed in CAs are demonstrated in

Figure 1: manually designed and two-level one. The first sub-figure (A) show manually designed emergent system using a set of three glider-guns and by them emitted gliders that are colliding; see animations in [

31]. In this case, the input of 11 defines the output of 1. The sub-figure (B) demonstrates the spontaneous occurrence of emergents, which are called ships, that generate yet another emergents of the 2

nd order; see animations in [

32]. This discovery is quite surprising because the system lacks feedback loops.

A good knowledge of massively-parallel computations is important for understanding of this research; concise introductions into this subject can be found in [

23,

33,

34]. This must be accompanied by knowledge of programming; e.g., Python [

35,

36] that is fundamental for understanding of the program used to define the neighborhood and generate animation snapshots [

30].

3. Prototypical Emergent Tasks

As already discussed, there is existing a long-standing class of problems within the field of massively-parallel computations where each problem is dealing with global decisions while utilizing only strictly local interactions. These type of problem is known to be notoriously difficult to implement computationally. On the other hand, biological systems are famous for their ability to find very fast solutions of such problems; this gives an opportunity of cross-fertilization to both fields. Researchers are only starting to understand the inner workings of bio-computing. For example, within computer science, picture manipulations, and network-wide decisions are facing a similar class of problems.

All of to the author-known solutions for the following synchronization tasks, even for those not mentioned here are using mechanistic approaches. In other words, manually designed CA evolution rules are carefully tailored to each task at hand. Contrary to those approaches, emergent information processing offers a unique approach utilizing self-organization and emergence to reach a synchronization event; this is discussed in depth in the

Section 5. In the following, only two generic synchronization tasks are explained: the density classification task and firing-squad synchronization problem.

3.1. Density Classification Task (DCT)

The density classification task (DCT) represents one of the generic tasks known in massively-parallel computing environments that serve as a test bed for novel computational approaches. The definition of the DCT (see the box below) is simple: one-dimensional array of two-state cells has to decide which of two states is dominant globally—in other words, a long-range task—, that all must be accomplished using only simple, local, evolution rules, and short-range neighborhood. Use of global variables is forbidden! In this case, cells must decide which of two possible states is in the majority, and stop at this state, or stay undecided; see publications [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Density classification task: "A configuration of two-state cellular automaton composed of N cells has m cells in zero state and n cells in one state where . When , the cellular automaton will end up with all cells in the state of zero. When , the cellular automaton will end up with all cells in the state of one. Finally, when , the cellular automaton will end up undecided"

The impossibility of the existence of a perfect classifier was proven in [

40]. For example, this obstacle was later overcome by Capcarrere, Sipper and Thomasini by relaxing the definition of the cellular automaton [

41]. It is important to stress that there are other existing variant of the DCT that are not discussed in detail in this text. Each time we deal with the DCT, it is necessary to understand which variant it is.

3.2. Firing-Squad Synchronization Problem: Also Known Under Names of Long-Range Synchronization or Pacemaker

The firing-squad synchronization problem (FSSP) is one of the crucial tasks that require clever strategies to achieve long-range synchronization by utilizing only short-range interactions [

42]. The first solution was found by Minski [

43], followed by [

44]. So far known best algorithms need more than

N steps for an array of

N cells to fire [

42,

45,

46]. The majority of known solutions are substantially slower in the range of

steps.

Original firing-squad synchronization problem: "An 1D array of cells contains an initiator. All cells are in a quiescent state except the initiator. The next cell’s state is defined by the states of neighbors and the cell itself. The task is to force all cells to fire simultaneously and in this way synchronize the entire array of cells."

Many available solutions of traditional FSSP are reviewed in [

47,

48,

49]. An important extension of the original FSSP can be found in the area of higher-dimensional FSSPs [

50].

Additionally, an important subclass of the FSSP operating above computational environments that contain multiple updating cycles [

50], i.e., there are operating quasi-asynchronous mechanisms of updating within utilized computational environments. This leads to the class of the distributed FSSP where there is an existing need to speed up synchronization of many processors during massively parallel computations [

51]; fast solutions can substantially speed up parallelization of huge computations that are distributed to many processors!

Finally, a modification of the FSSP, found accidentally, which became the main research subject of this publication, is shown in the subsequent text.

3.3. Novel Semi-Two-Dimensional Synchronization Problem Called Necklace

A novel, global, narrow, semi-two-dimensional synchronization problem (S2D-SP) called necklace is defined below. The term narrow means that height of only about ten cells and any larger width eventually produces periodic synchronization. This is enabled by the use of 2D neighborhood with a special shape to reach unexpectedly fast and highly counter intuitive solution.

The semi-two-dimensional synchronization problem called necklace: "The S2D-SP is defined as a narrow 2D array of cells using the periodic boundary condition. The goal is to find a specific neighborhood that will bring the system to synchronization and fire the array of cells simultaneously at one specific moment."

4. Definition of Modified GoL Cellular Automaton Used To Solve Semi-Two-Dimensional Synchronization Problem

The main motivation to explore the proposed synchronization problem is to understand the design of long-range synchronization tasks in purely locally defined massively-parallel systems. The proposed model is not an ideal solution. Nevertheless, there exists a potential to its future improvements. The uniqueness and biggest values of the proposed solution are its extraordinary speed and its capability of uncovering of so far unknown method of synchronization.

The solution of the semi-two-dimensional synchronization problem (S2D-SP), which is based on the original definition of the J.H. Conway’s GoL cellular automaton [

26], where the modification is clearly declared (see point 2):

- 1:

-

A 2-dimensional (2D) cellular automaton using the GoL local evolution rule with eight neighbors:

- (a)

Any cell with less than two alive cells will die (under-population).

- (b)

Any alive cell with two of three alive neighbors stay alive (survival).

- (c)

Any cell with more than three alive cells will die or stay dead (overpopulation).

- (d)

Any dead cell with exactly three alive neighbors will become alive (birth).

- 2:

The cellular automaton uses the neighborhood #740.032 (it clearly differs from the original GoL neighborhood #469.440, definition link below). This change represents the only difference from the original GoL’s CA definition.

- 3:

The CA updates are occurring in discrete steps: synchronous updates.

The definition of each neighborhood is provided in detail within [

11]. The used eight neighbors defining each possible neighborhood are selected from the wider neighborhood of

cells. Very briefly, each existing neighbor of the given neighborhood has number

where

n is the ordering number of each active neighbor; the central cell is skipped in counting. The lower-left corner has number

, the nearest right neighbor has number

, it continues in given and all above lines until the upper-right corner is reached with

. Those numbers are inserted in a sum defining the neighborhood number.

The Algorithm 1 differs from the definition of M2D SP to increase the efficiency of its processing. Additionally, Algorithm 1 can be further computationally optimized, but this is not the subject of this research; it will require writing down a library in C programming language that will be a part of the Python program.

|

Algorithm 1:The algorithm, describing modified GoL, is performed simultaneously in all cells during one time step. The main loop is omitted. The algorithm was applied to generate that are presented in the following Section 5; e.g., some snapshots are shown further in Figure 3 and Figure 6 . |

- 1:

function NeighborsAlive() - 2:

Count number of alive neighbors (state = 1) of the updated cell - 3:

end function - 4:

if

then

- 5:

state = 1 “Comment: Cell becomes or stay alive” - 6:

else ifthen

- 7:

“Comment: Cell stays alive” - 8:

else - 9:

“Comment: Cell dies or stay dead” - 10:

end if |

The general CA updating principles: All cells have two time layers. One layer is considered to be old and the other one new. The new cells are updated sequentially. Once all cells of the new layer are updated, the old and new layers are swapped: the new layer becomes the old layer and the new layer is erased. The simulation is proceeding by alternative swapping of old and new layers until it is terminated; details in [

11].

5. Research Results

An important discovery of semi-two-dimensional synchronization problem (S2D-SP) is reported in this section. It is not only the first emergent solution to the modified synchronization problem (SP) known to the author, but it is so far the fastest known one. Actually, it is the fastest of all known solutions to all synchronization problems, e.g., the DCT or FSSP, that are known to the author. Simultaneously, the solution of modified S2D-SP is paving a path towards similar emergent solutions of many similar naturally observed complex phenomena. Density classification task is yet another hot candidate to look for such type of solutions.

5.1. Solution of Semi-Two-Dimensional Synchronization Problem (S2D-SP)

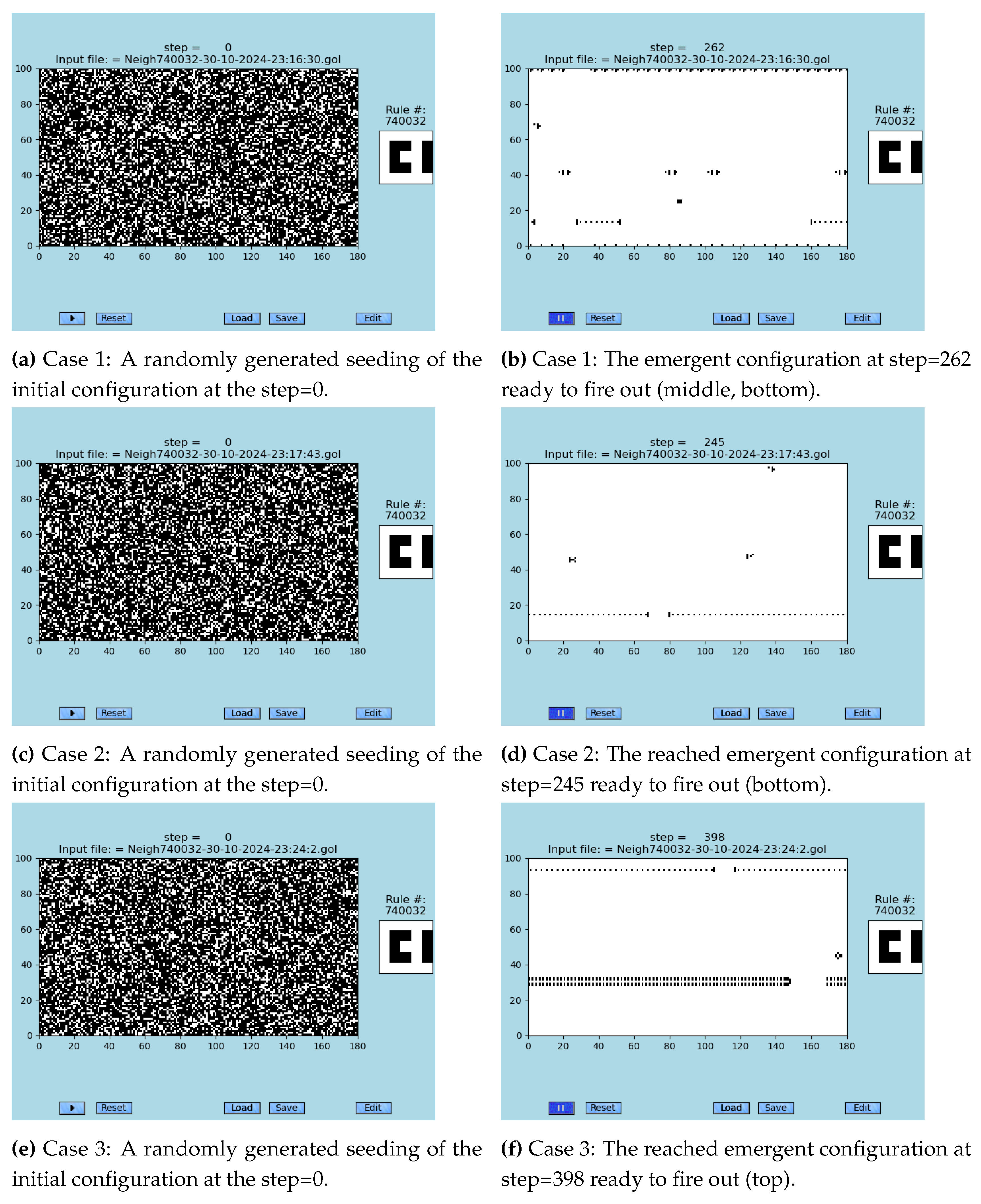

In the following, as already stated, so far the fastest known solution of any synchronization problem, semi-two-dimensional synchronization problem (S2D-SP) is presented (the solution was accidentally found in 2009). The key part of the solution is the fact that one of the neighborhoods, #740.032, is capable of solving S2D-SP using the original GoL evolution rule. Unfortunately, there always remains a desynchronized narrow gap during every synchronization event. A set of three solutions that are spontaneously emerging from sufficiently dense random initial conditions

’*.gol’ can be seen in the sample runs demonstrated in Videos 1, 2, and 3 (Supplementary Videos 1, 2, 3) or [

52], snapshots shown in

Figure 2.

Those three sample runs were selected from 20 randomly initiated runs of the neighborhood #740.032; see the list of all 20 ’*.gol’ initial configuration files, where 12 of them lead to the necklace emergent and eight are not, in Supplement 1 in the ZIP file. Those numbers yield a rough estimate of probability of the occurrence of a necklace emergent in any randomly generated initial configuration.

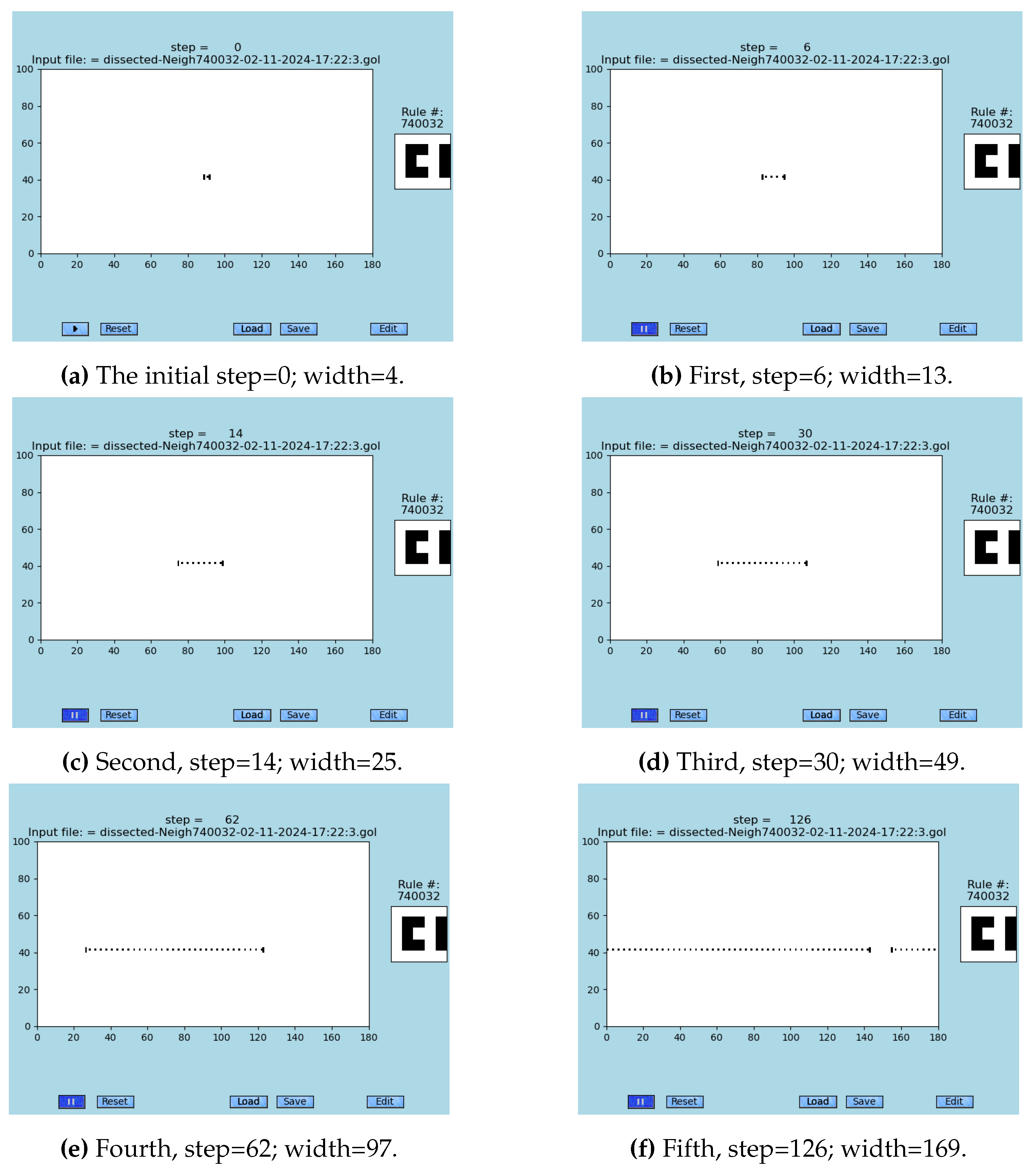

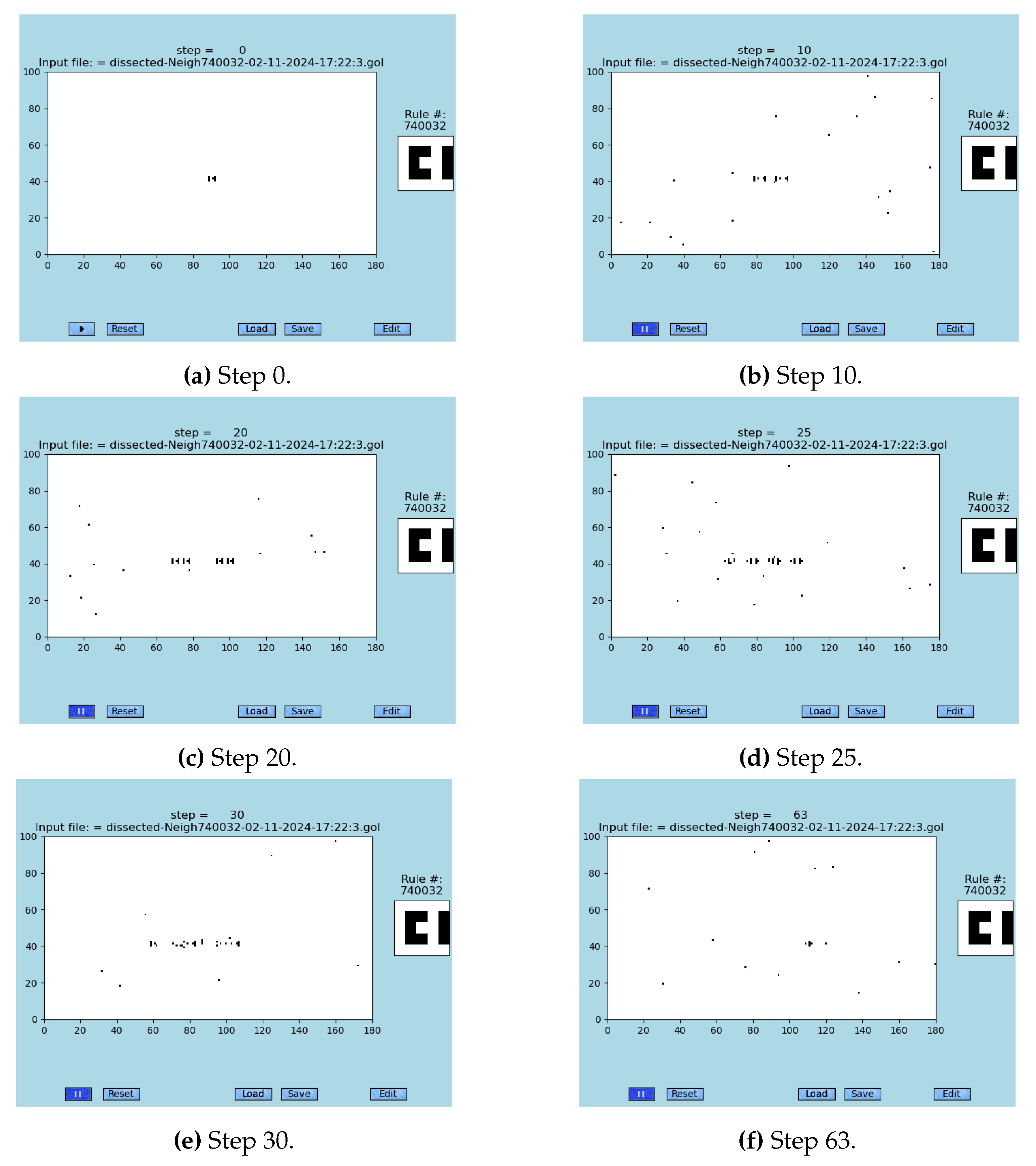

A precisely selected initial configuration of an emergent of the S2D-SP—as it was dissected from the Case 1 in

Figure 2 —is displayed in

Figure 3 (A)–(F) where the maximal theoretical speed of this solution is measured; see Video 4 (Supp. Video 4) [

52] and the graph in

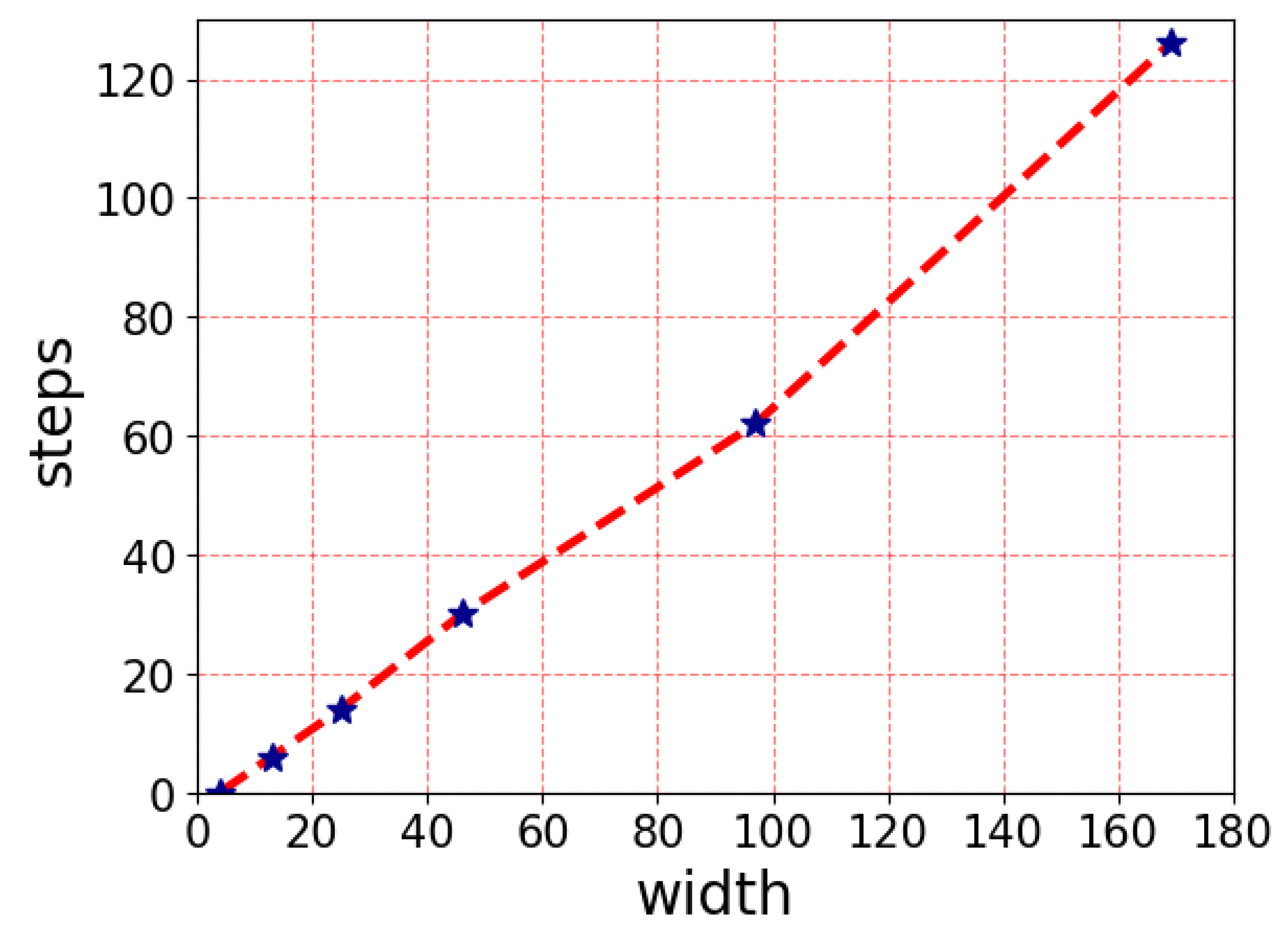

Figure 4. A semi-linear dependence between the number of steps necessary to achieve synchronization for a defined length was found. It must be mentioned that only some lengths can be synchronized using this neighborhood, as seen from

Figure 3, and graph in

Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Long-range synchronization: (A) The snapshots start from a pre-selected seed. (B)-(F) Each subsequent snapshot depicts approximate doubling of the length of synchronized cells. Step and width of each coordinated string is provided; see graph in

Figure 4 and animations in [

52] and [

12,

30].

Figure 3.

Long-range synchronization: (A) The snapshots start from a pre-selected seed. (B)-(F) Each subsequent snapshot depicts approximate doubling of the length of synchronized cells. Step and width of each coordinated string is provided; see graph in

Figure 4 and animations in [

52] and [

12,

30].

Figure 4.

The dependence of the number of steps (vertical axis) necessary to reach a synchronization event on the width of the cellular array (horizontal axis). The dependence is not linear. Actual values are taken from sub-figures of

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

The dependence of the number of steps (vertical axis) necessary to reach a synchronization event on the width of the cellular array (horizontal axis). The dependence is not linear. Actual values are taken from sub-figures of

Figure 3.

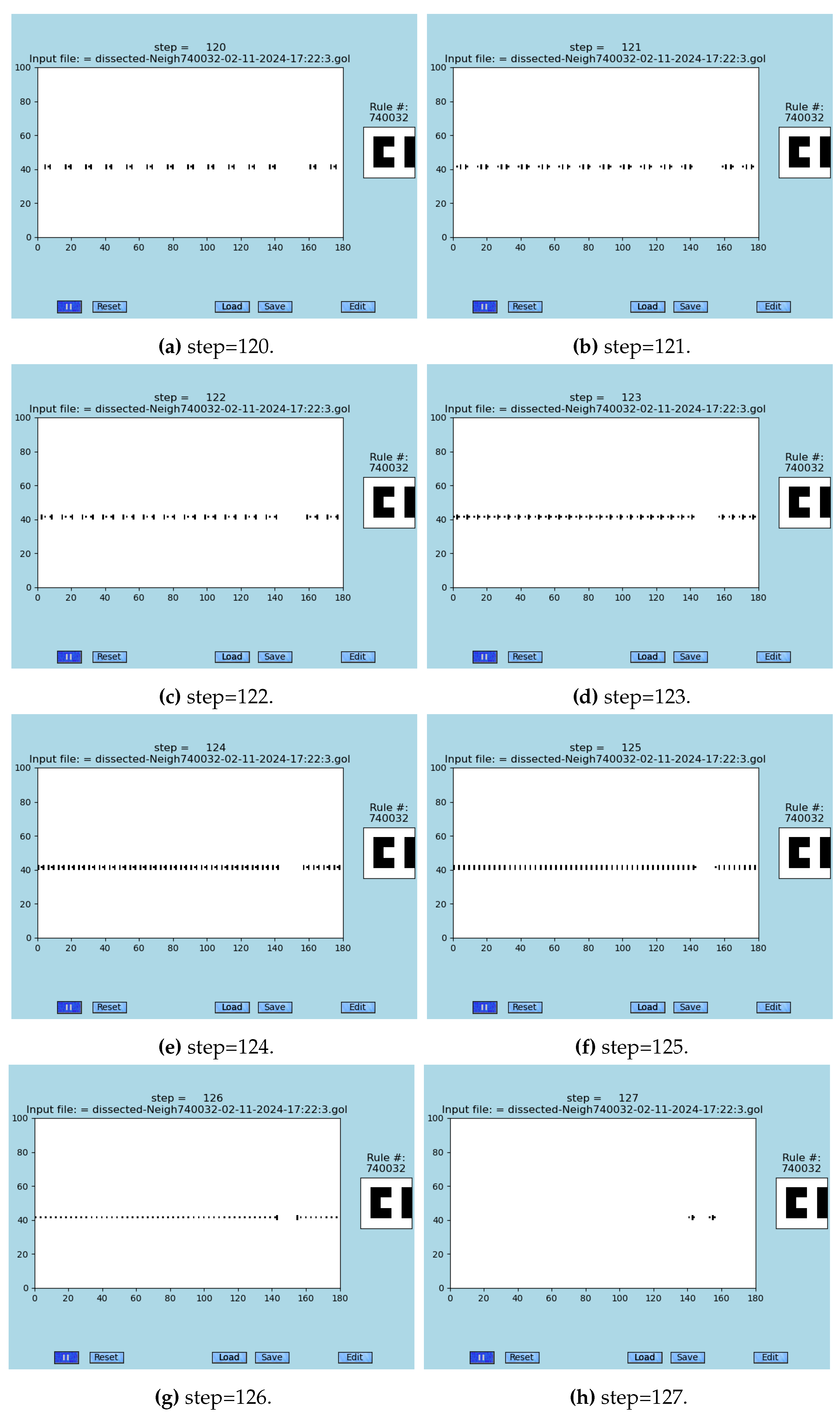

A sequence of snapshots of the S2D-SP simulation is demonstrated in

Figure 5 where six preceding steps and one subsequent step to the synchronizing step are demonstrated. The way of propagation, collisions, and bouncing of emergent gliders is displayed in a concise way; see Video 4 (Supplementary Video 4) [

52]. The solution is highly counter intuitive and almost impossible to design manually. Yet random search of the space of all neighborhoods revealed it. A natural question arises: what other emergent systems is GoL-N24 hiding among its 731,471 possible configurations are able to accomplish?

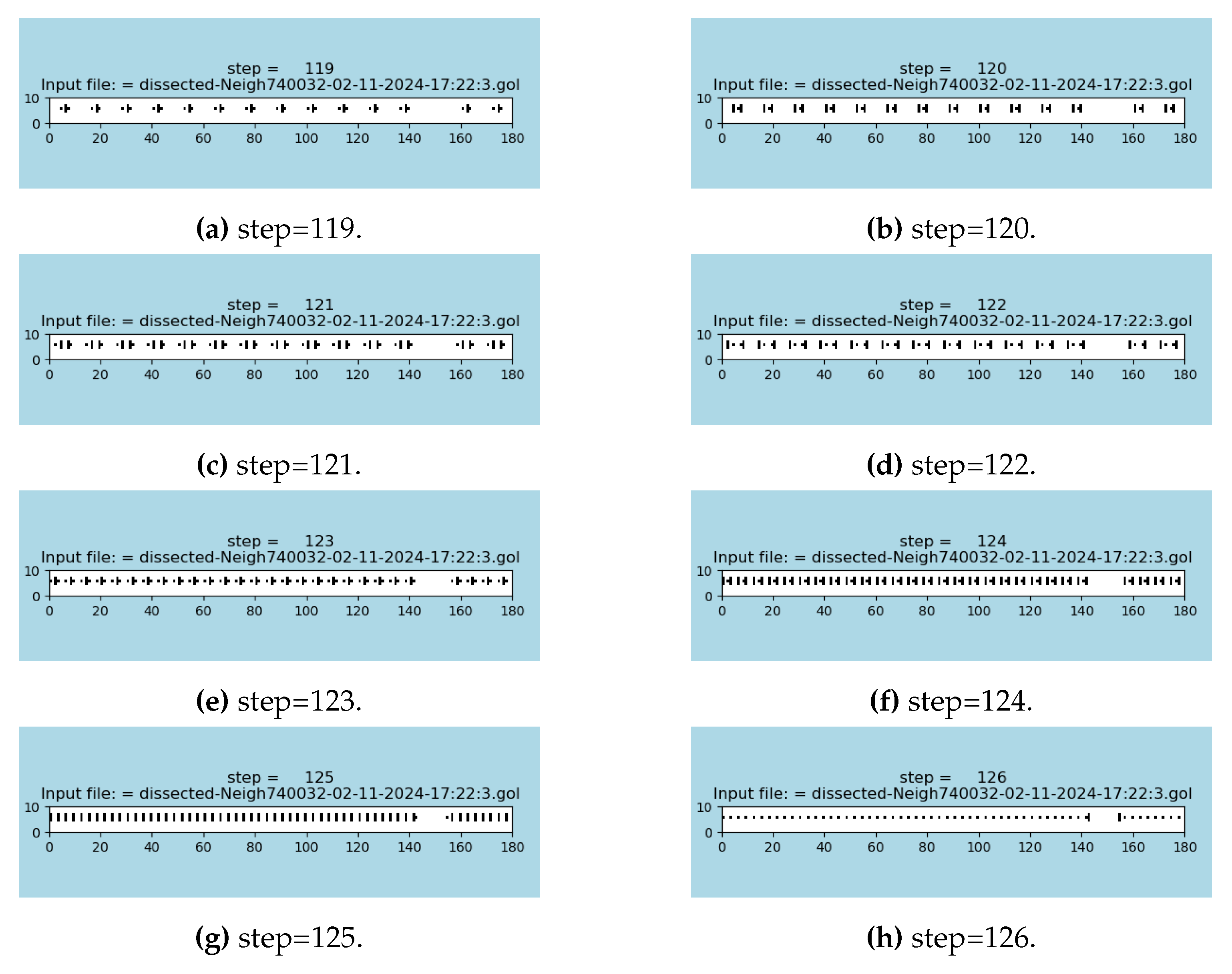

A zoomed area of the S2D-SP simulation is demonstrated in

Figure 6 where a sequence of seven steps preceding the synchronization event are shown; in this case, the last sub-figure is the synchronization event itself that occurs at step 126.

Figure 5.

Long-range synchronization: eight subsequent steps preceding the full scale synchronization (G) are shown; see the animations in [

52], made by [

12,

30].

Figure 5.

Long-range synchronization: eight subsequent steps preceding the full scale synchronization (G) are shown; see the animations in [

52], made by [

12,

30].

Figure 6.

Seven steps (A)–(G) that are preceding the creation of the necklace emergent, which itself is depicted in the sub-figure (H); see the animations in [

52], made by [

30], and video-database [

12].

Figure 6.

Seven steps (A)–(G) that are preceding the creation of the necklace emergent, which itself is depicted in the sub-figure (H); see the animations in [

52], made by [

30], and video-database [

12].

5.2. Maximal Speed to Reach Synchronizing Event in S2D-SP

The maximal possible speed of reaching a synchronizing event is demonstrated and measured in

Figure 5 (G): it is 126 steps for width of 180 cells; it requires a manually designed initial configuration prior to running the simulation.

In the case of spontaneously arising synchronization events, the number of steps that are going to be reached cannot be predicted. It would be longer in the vast majority of randomly initiated simulations. Not every simulation leads to necklace emergent, as already shown, only about 60% of simulation runs will reach the emergent stage.

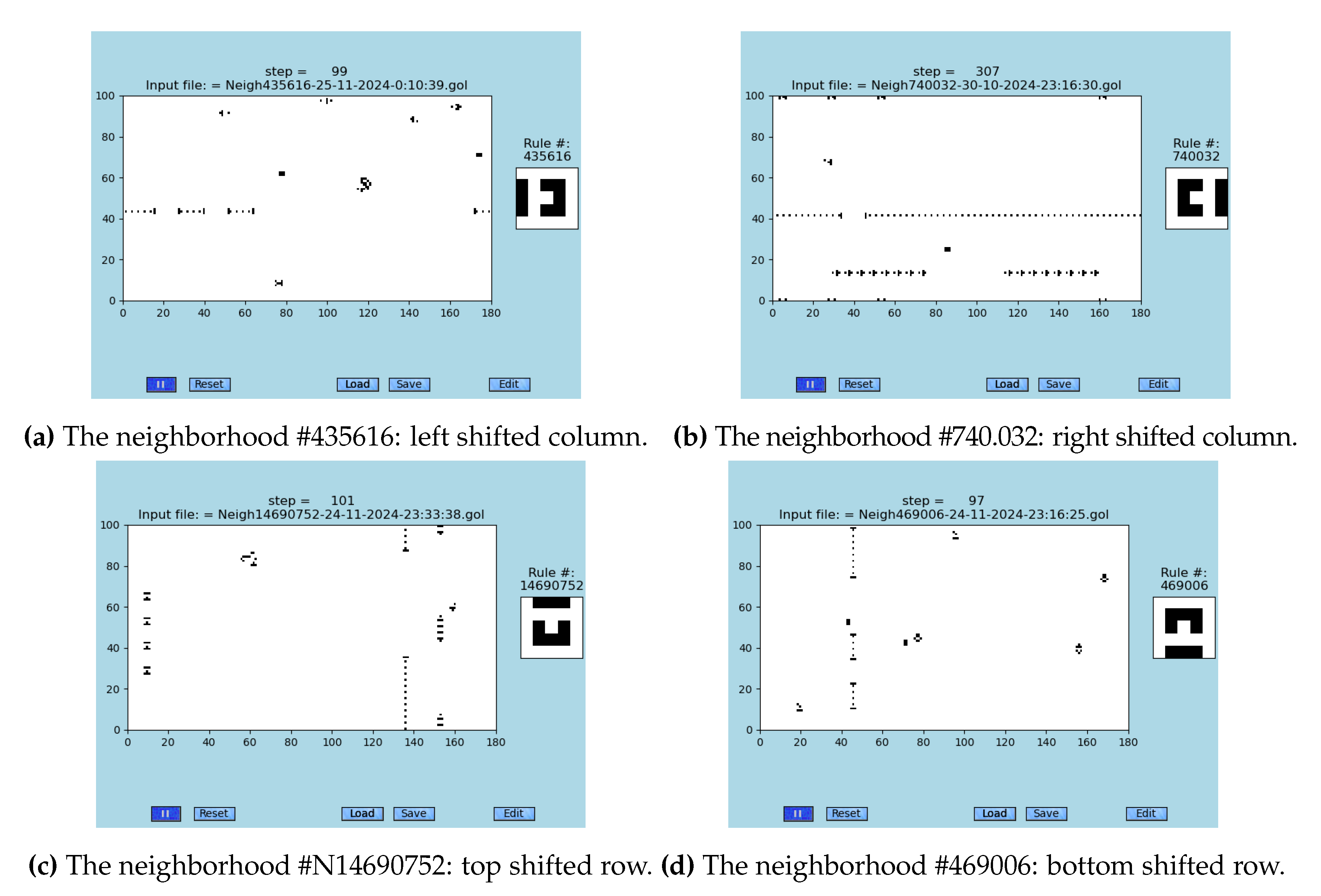

5.3. Four Different Neighborhoods generating S2D-SP

Logically, there are four possible configurations of neighborhoods with a detached one column or row of cells that produce the S2D-SP: #435616 (left column), #740.032 (right column), #14690752 (top column) and #469006 (down column); see

Figure 7 for their depictions. This is due to the four-fold symmetry of the neighborhoods that originates in four-sided cells. The neighborhood #740.032 was the first one found and is applied in all simulations presented in this research article. All four neighborhoods are yielding the qualitatively identical behavior.

5.4. Differences Between Original FSSP and S2D-SP

A warning. To make things clear, the proposed S2D-SP solution is much faster than any known solution to the original FSSP [

42,

47,

48,

49], but it is important to stress out that both problems differ. FSSP is a one-dimensional problem, while S2D-SP is a semi-two-dimensional problem with a gap within synchronized cells. Yet S2D-SP does not require much more of computational power, as the height of CA can be quite low in comparison of a single cell layer in the original FSSP. It can be only 10 cells high, as used in

Figure 6, and probably even less.

The original FSSP is solved by utilizing manually designed evolution rules, whereas S2D-SP utilizes emergents that are arising from a specific configuration of the cell neighborhood. The original FSSP is not error-resilient and simultaneously is extremely sensitive to the initial configuration. Contrary to it, S2D-SP that is partially error-resilient and spontaneously arises in a certain percentage of cases from random initial conditions. Those properties of the S2D-SP are quite unique when compared to the original FSSP.

5.5. Resilience of S2D-SP Towards Injected Errors

A possible full resilience of the S2D-SP solutions against injection of errors would be an important factor in finding a solution that will recover from imperfect computations; see

Figure 8 for a sample run. Unfortunately, as expected, the S2D-SP is not resilient against systematically injected errors into the evaluation process. Nevertheless, as shown in the randomly initiated simulations the system is relatively resilient against sporadically injected errors; see Supplementary Videos 1, 2, and 3 or [

52]. Simulations recover from sporadically injected error due to the parallelism of emergents; destruction of all emergents except one will lead to the recovery of the process of the final synchronization, which will become only delayed. Living systems possess the natural capability of error-resilience because the wetware they are built upon is made of faulty computing elements that malfunction or, alternatively, are often being replaced in the run-time due to apoptosis and cellular division.

Figure 8 demonstrates the resilience of the found solution of the S2D-SP against systematic injection of 0.001% of errors in the evolution rule; see Supplementary Video 5. Each error swaps the state of given cell into its opposite value with the above-given probability. As already declared, the found S2D-SP is not possessing error-resilience property against systematic errors. Obviously, the error-resilience of emergent solutions bring the next level of complications into finding emergent solutions, as already demonstrated in [

11,

13].

6. Future Directions

The demonstrated fast solution of long-range synchronization gives us an idea that many other, by nature utilized, solutions might be based on a similar approach. The surprising simplicity of the S2D-SP solution potentiated by its speed provide an impetus to search further and deeper. It would be advisable to try to explore many others emergent processes that are observed in the natural phenomena, make their database, and trace them back to a simple evolution rule and interaction topology whenever possible.

Is emergence explainable? "How many known emergent natural phenomena can be traced back to some combination of constituting matrix, local evolution rule, and topology of interaction neighborhood?"

The demonstrated S2D-SP solution is giving us a strong foundation to the possibility that many emergent natural phenomena can have surprisingly simple explanation. While observing the demonstrated solution of the S2D-SP, it would be really interesting to search for a fast and effective solution of the DCT using a similar approach among all neighborhoods from 731,471 possible configurations within GoL-N24. Additionally, the found S2D-SP fast emergent solution is opening a way towards new theoretical approaches in explanation of self-organization and emergence as observed in complex systems, and hence, allow effective prediction and design of emergent complex systems.

6.1. Biological Synchronization: Pacemakers

Biological systems express the capability to synchronize cellular activity at long ranges. One of the typical examples is a pacemaker cells that are located at the right atrium of the human heart; see

Figure 9 for a hypothetical wiring of a biological pacemaker. Artificial, error-resilient pacemakers can be designed using this concept. In biology, there are observed another instances of single-cell organisms (amoebas, e.g., Dictyostelium discoideum), light emission synchronization of fireflies, and others that might benefit from the concept of EIP.

In the light of the presented description of spontaneous, long-range synchronization, which is emerging from any random initial condition under the assumption that the topological structure of underlying excitable medium has a specific connectivity, as described by the used neighborhood, it would be really interesting to study minuscule connectivity of cells that are present within mammalian hearts’ pacemaker.

There exists a non-negligible possibility that the anatomic structure of biologically observed pacemakers can resemble the found rule #740.032. This finding is calling for deeper biological studies of structural composition of living systems according to the author of this text.

6.2. Re-Configurable Computers, Robots, and Biocompatible Interfaces

The concepts that are going to be developed within EIP methodology are potentially having a wide range of applications within the design of reconfigurable, error-resilient, life like computers, robots, biocompatible prosthetic, besides many other potential applications. The demonstrated solution to S2D-SP is providing a living example of design of self-organizing, adaptive, emergent solutions to scientifically ’hard’ system behaviors that are very easy to reach within biological systems.

Some currently developed soft-materials and soft-robotics are undergoing a fast development, for example, re-configurable metal-droplet-containing materials [

53]. This and similar research would create a solid starting experimental basis to explore applications of EIP in applications.

The end goal of the proposed research in the field of computing is re-configurable, self-assembling, and emergent computers that can, after damage or failure of their substantial part, reconfigure themselves and regain fully, although somehow slower, original functionality. Currently used computers usually become faulty with a failure of a single or small number of its components.

6.3. Reverse Engineering

From the accidentally discovered solution of the S2D-SP and knowledge of the total number of possible neighborhoods 731,471, it is obvious that discovery of all future rules must be accomplished by utilizing backward search of the entire neighborhood space. The given global emergent behavior will be found or approximated by searching through the huge space of all possible neighborhoods. Manual searching is time-consuming and brings with itself a great burden. There is a need to develop novel optimization approaches to overcome this obstacle; this would be a challenging task.

Researchers will eventually face even bigger obstacles in the search of perspective solutions when the evolution rule itself is allowed to change. Novel automatic searching algorithms must be developed to accomplish such a feat. At this moment, the methodology is not developed.

7. Discussion

The extraordinarily fast solution of the S2D-SP based on a special shape of the neighborhood—implemented using the software GoL-N24 [

12,

30]—is opening doors towards explorations of simple, massively-parallel, from the first principles defined models that have the capability to explain fairly complicated and complex natural phenomena. The complexity is arising from the simplicity in its purest sense. A deep and broad introduction into the entire problematic can be found in the review [

11] along with the preceding publication [

13] and video-database [

12] that all together introduces the concept of error-resilient emergents in examples and their animations.

Surprisingly, a similar situation to EIP had been encountered by Benoît Mandelbrot in fractal geometry where a very primitive convergence criteria applied to simple iterative schemes using complex numbers had led to the creation of extremely complicated and infinitely structured objects called fractals [

54]. Yet another example of complexity arising from the simplicity.

The solution of the S2D-SP is emergent, contrary to many others solutions that are all based on manual design utilizing mechanistic approaches, e.g., [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

48,

49]. Emergent designs are often superior to their mechanistic counterparts with respect to their high error-resilience; that is why this study describes an early version of an emergent SP.

The most important results achieved by the S2D-SP solution are: (a) The fact that time

by which the solution is reached is always smaller than the width of the synchronized array

w, i.e.,

. This is valid for any one of the shifted columns or rows of neighbors within given neighborhoods; see the rule #740.032 and its rotated versions in

Figure 7. (b) Some widths are synchronized faster than others while taken relatively to the width, see non-linearity in

Figure 4. (c) There always exists a gap in synchronized arrays of necklace emergents with varying their exact position and length. (d) A possibility to speed up synchronization of many processors during massively parallel computations [

51] exists; this will require deeper studies. (e) A small level of error-resilience of necklace emergent against sporadically injected errors is detected. (f) Lastly, a very important factor is opening the doors to apply the given methodology in search of other more effective neighborhoods tailored to this and other synchronization tasks.

The main motivation of this research originates in the observations of the functioning of living systems—such as cells, tissues, organs, and bodies—, which are highly resistant against cellular dysfunctions and replacement during ongoing ’computations’ operating endlessly within them. It is the direction that deserves deeper studies of observed biological systems in the light of EIP methodology. Very probably, there are waiting for us many discoveries of counterintuitive massively-parallel ’computing’ systems. The most challenging task of all within biology is the capability to explain multiscale systems using simple root processes that will yield multiscale emergent systems, viz. this research and [

11,

12,

13].

While looking from a broader perspective, as already hypothesized in [

30], it is probable that GoL-N24 is opening doors towards a completely new type of descriptions of naturally observed phenomena that are based on massively-parallel, uniform, strictly localized interactions. This statement is not coming from thin air; quite the opposite in physics, biochemistry, and biology are known for many phenomena fitting exactly this approach. Just to name some examples: lattice formation in solids; biochemical cellular components like DNA, microtubules, cellular membranes; tissues and organs.

From the purely computational point of view, it would be interesting to find a similarly formulated solution to the DCT. Inevitably, the search for such a solution will require a lot of computational experiments because backward search using manual design of a neighborhood capable of such a feat is, according to insights gathered during the study of the S2D-SP solution is almost impossible. This automatically leads to development of methods of reverse search of uniform microevolution functions and local neighborhoods for each cell of the massively-parallel computing environment. It must be stressed out that the searched space of the combination of microevolution functions and local neighborhoods is astonishingly huge.

The research carried out in this publication is providing one component of an emergent computational environment using massively-parallel computations: the pacemaker. It is hypothesized that this type of computation has a quite high chance of becoming error-resilient, and hence, it will become quite independent of hardware’s or wetware micro-components’ failures.

8. Conclusions

The main objectives of this publication were (a) demonstration that life can be understood as a continuous flow of micro-processes that are operating above a constituting matrix (medium), and (b) providing a proof in the form of a specific example of this flow in the form of a long-range synchronization within short-range communicating medium.

A synchronization problem that was selected to demonstrate the existence of a surprisingly fast synchronization is based on the use of a specific neighborhood along with GoL evolution rule. The found solution of a semi two-dimensional synchronization problem, in which the synchronization is achieved within steps, was proven to be substantially lower than the width of the synchronized cell array w, i.e., . This solution represents the fastest known synchronization problem known to the author; it was found accidentally. As demonstrated, a solution arises spontaneously in roughly 60% of simulation cases starting from a random initial condition. In the case of injection of a tiny number of error events, the solution can resets itself spontaneously.

The resistance of the found solution against insertions of errors into the evaluation process had been thoroughly studied. The solution is error-resistant only against sporadically injected errors. In such cases, it is capable of reestablishing itself. Additionally, the synchronization is reached in a larger number of steps. Injection of systematic errors in the evaluation process lead, inevitably, into the total destruction of the evaluation process; hence, a synchronization event never occurs.

Fourfold symmetry of neighborhoods is an important property of using asymmetric neighborhoods with emergent information processing systems. This is substantially narrowing the total number of possible neighborhoods.

The research presented in this publication serves as a call for the search of similar self-organizing, adaptive, emergent solutions that will describe and simulate naturally observed phenomena in biology and beyond; that all achieved by a set of very primitive evolution rules and neighborhoods. In this regard, several possible applications—biology, heart pacemaker, future computers, etc.—were presented in order to allow everyone to imagine the importance and relevance of emergent information processing in many scientific disciplines.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary ZIP file 1: randomly-gen-initial-gols.zip; Supplementary Video 1; Supplementary Video 2; Supplementary Video 3; Supplementary Video 4.

Acknowledgments

The research is the result of independent research that was fully sponsored by the author himself without any kind of external support. This work is entirely dedicated to the people of The Czech Republic as thanks for many hospitalizations, heart operations, and four implanted defibrillators that occurred over 20 years prior to heart transplantation in 2014. Additional thanks go to Prof. Pirk, M.D. and his team who carried out the heart transplantation that enabled the author to finish this research. The solution to S2D-SP was found in 2009, but due to the failing heart, it was impossible to finish a research paper at that time.

Abbreviations

CS - complex system

MPC - massively-parallel computations

SO - self-organization

EM - emergence

EIP - emergent information processing

CA - cellular automaton

GoL - ’Game of Life’ cellular automaton

SP - synchronization problem

FSSP - firing-squad synchronization problem

S2D-SP - semi-2-dimensional synchronization problem

DCT - density classification task

ABM - agent-based modeling

References

- Funk, R.H.W. Understanding the Feedback Loops between Energy, Matter and Life. Frontiers in Bioscience (Elite Ed) 2022, 14, 29. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.P.; Joyex, G.F. The Origins of RNA World. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives Biology 2012, 4, a003608. [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.; Malek, A. The Transformation by Catalysis of Prebiotic Chemical Systems to Useful Biochemicals: A Perspective Based on IR Spectroscopy of the Primary Chemicals: Solid-Phase and Water-Soluble Catalysts. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 10125. [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.; Malek, A.; Odenbrand, I. The Transformation by Catalysis of Prebiotic Chemical Systems to Useful Biochemicals: A Perspective Based on IR Spectroscopy of the Primary Chemicals II. Catallysis and the Building of RNA. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4712. [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.; Malek, A. The Transformation by Catalysis of Prebiotic Chemical Systems to Useful Biochemicals: A Perspective Based on IR Spectroscopy of the Primary Chemicals I. The Synthesis of Peptides by the Condensation of Amino Acids. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 928. [CrossRef]

- Madl, P.; Renati, P. Quantum Electrodynamics Coherence and Hormesis: Foundations of Quantum Biology. International Journal of Molecular Science 2023, 24, 14003. [CrossRef]

- Cervera, J.; Levin, M.; Mafe, S. Bioelectricity of non-excitable cells and multicellular memories: Biophysical modeling. Physics reports 2023, 1004, 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Lagasse, E.; Levin, M. Future medicine: from molecular pathways to the collective intelligence of the body. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2023, 29, 687–710. [CrossRef]

- Cernet, B.; Adams, D.; Lobikin, M.; Levin, M. Use of genetically encoded, light-gated ion translocators to control turmorigenesis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19575–88. [CrossRef]

- Bongard, J.; Levin, M. There’s Plenty of Room Right Here: Biological Systems as Evolved, Overloaded, Multi-Scale Machines. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 110. [CrossRef]

- Kroc, J. Emergent Information Processing: Observations, Experiments, and Future Directions. Software 2024, 3, 81–106. https://www.mdpi.com/2674-113X/3/1/5, . [CrossRef]

- Kroc, J. Exploring Emergence: Video-Database of Emergents Found in Advanced Cellular Automaton ’Game of Life’ Using GoL-N24 Software. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373806519, 2023. Accessed as on 09-10-2023.

- Kroc, J. Robust massive parallel information processing environments in biology and medicine: case study. Journal of Problems of Information Society 2022, 13, 12–22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361818826, . [CrossRef]

- Grotzinger, L.; Amos, M.; Gorochowski, T.E.; Carbonell, P.; Oyarzún, D.A.; Stoof, R.; Fellermann, H.; Zuliani, P.; Tas, H.; Gõni Moreno, A. Pathways to cellular supremacy in biocomputing. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 5250. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Pollack, G., Water and the Cell; Springer Dordrecht, 2006; chapter Solute Exlusion and Potential Distribution Near Hydrophilic Surfaces, pp. 165–174. [CrossRef]

- Elton, D.; Spencer, P.; Riches, J.; Williams, E. Exclusion Zone Phenomena in Water—A Critical Review of Eperimental Findings and Theories. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 5041. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Hong, J.; Sharma, A.; Pollack, G.; Bahng, G. Exclusion zone and heterogeneus water structure at ambient temperature. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195057. [CrossRef]

- Seneff, S.; Nigh, G. Sulfate’s Critial Role for Maintaining Exclusion Zone Water: Dietary Factors Leading to Deficiencies. Water 2019, 11, 22–42. [CrossRef]

- Turing, A. On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1937, s2-42, 230–265. [CrossRef]

- Turing, A. On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem: A Correction. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1938, s2-43, 544–546. [CrossRef]

- Hagan, S.; Hameroff, S.R.; Tuszyński. Quantum computation in brain microtubules: Decoherence and biological feasibility. Physcical Review E 2002, 65, 061901. [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.; F., P. Quantum effects in brain: A review. AVS Quantum Science 2020, 2, 022901. [CrossRef]

- Kroc, J.; Balihar, K.; Matejovic, M. Complex Systems and Their Use in Medicine: Concepts, Methods and Bio-Medical Applications. review, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330546521, . [CrossRef]

- Kroc, J., Complex Systems With Artificial Intelligence; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2024; chapter Difference Between AI and Biological Intelligence Observed by Lenses of Emergent Information Processing. [CrossRef]

- Illachinski, A. Artificial War: Multiagent-Based Simulation of Combat; World Scientific, 2004; p. 787. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M. The fantastic combinations of John Conway’s new solitaire game "life". Scientific American Magazine 1970, 223, 120–123. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mathematical-games-1970-10/.

- Johnson, S. Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities and Software; Penguin Books: New Delhi, India, 2001; p. 288.

- Kroc, J. Simulation of Dynamic Recrystallization by Cellular Automata. PhD thesis, Charles University, Prague, 2001.

- Kroc, J. Application Cellular Automata Simulations to Modelling of Dynamic Recrystallization . In Proceedings of the Computationla Science — ICCS 2002; Sloot, P.; Joekstra, A.; Dongarra, J., Eds., Berlin Heidelberg, 2002; Vol. 2329, pp. 773–782. [CrossRef]

- Kroc, J. Exploring Emergence: Python program GoL-N24 simulating the ’Game of Life’ using 8 Neighbors from 24 Possible. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365477118, 2022. Accessed as on 03-25-2023.

- Kroc, J. Emergent computations: simulations of logic-gate OR using cellular automaton GoL-N24 implemented in Python. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367380336/, 2023. Accessed as on 043-01-2023.

- Kroc, J. Emergent Computations: Emergents Are Breeding Emergents as Demonstrated on Ships Breding Trains of Ships Occuring in Modified GoL Using Program GoL-N24. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368635079/, 2023. Accessed as on 04-01-2023.

- Kroc, J.; Sloot, P.; Hoekstra, A., Simulating Complex Systems by Cellular Automata; Understanding Complex Systems, Springer, 2010; chapter Introduction to Modeling of Complex Systems Using Cellular Automata. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-642-12203-3.

- Illachinski, A. Cellular Automata: A Discrete Universe; World Scientific, 2001; p. 808. https://www.worldscientific.com/worldscibooks/10.1142/4702#.

- Sundnes, J. Introduction to Scientific Programming with Python; Simula SpringerBriefs on Computing, Springer Cham, 2020; p. 148. Open Access, "https://www.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-50356-7", . [CrossRef]

- Langtangen, H. A Primer on Scientific Programming with Python; texts in Computational Science and Engineering, Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2016; p. 922. Open Access, "https://www.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-662-49887-3", . [CrossRef]

- Suryakanta, P.; Sudhakar, S.; Birendra, K.N. Deterministic Computing techniques for Perfect Density Classification. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 2019, 29, 1950064. [CrossRef]

- Chalia, A.; Hao, D.; Rozum, J.C.; Rocha, L.M. The Effect of Noise on the Density Classifcation Task for Various Cellular Automata Rules. In Proceedings of the ALIFE 2024: Proceedings of the 2024 Artificial Life Conference, 07 2024, Artificial Life Conference Proceedings, p. 83. [CrossRef]

- Gács, P.; Kudyumov, G.L.; Levin, L. One dimensional arrays that wash out finite islands. Problemy Peredachi Informatsii (in Russian) 1978, 14, 92–98.

- Land, M.; Belew, R. No perfect two-state cellular automata for density classification exists. Physical Review Letters 1995, 74, 1448–1450. [CrossRef]

- Capcarrere, M.S.; Sipper, M.; Tomassini, M. Two-state, r=1 cellular automaton that classifies density. Physical Review Letters 1996, 77, 4969–4971. [CrossRef]

- Carrera, T.; Gustavo, B.; Lemos, L.; Settle, A. An overview of recent solutions to and lower bounds for the firing synchronization problem. arXiv:1701.01045.

- Goto, E. A minimal time solution on the firing squad problem. Dittoed course notes for Applied Mathematics 1962, 298, 52–59.

- Minski, M. Computation: finite and infinite machines; Prentice-Hall, 1967; p. 317.

- Mazoyer, J. A Six-state Minimal Time Solution to the Firing Squad Synchronization Problem. Theoretical Computer Science 1987, 50, 183–238.

- Boodie, K. A Minimal Time Solution to the Firing Squad Synchronization Problem with Von Neumann Neighbourhood of Extent 2. PhD thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2019. https:dc.uwm.edu/edt/2161.

- Kobayashi, K.; Goldstein, D. On Formulations of Firing Squad Synchronization Problem. In Proceedings of the Unconventional Computation. UC 2005; Claude, C.; Dineen, M.; Pǎul, G.; Pérez-Jímenez, M., Eds., Heidelberg, 2005; Vol. 3699, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 157–168.

- Gruska, J.; La Torre, S.; Napoli, M.; Parente, M. Various Solutions for the Firing Squad Synchronization Problem. ArXive, . [CrossRef]

- Napoli, M.; Parente, M., Computing with New Resources; Springer, 2014; Vol. 8088, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, chapter Minimum and non-Minimum Time Solutions to the Firing Squad Synchronization Problem, pp. 114–128.

- Manzoni, L.; Umeo, H. The Firing Squad Synchronization Problem on CA with Multiple Updating Cycles. Theoretical Computer Science 2014, 559, 108–117. [CrossRef]

- Coan, B.A.; Dolev, D.; Dwork, C.; Stockmeyer, L. The Distributed Firing Squad Problem. SIAM Journal of Computing 1989. [CrossRef]

- Kroc, J. Animations of Global Synchronization Problem Using Strictly Local Interactions by Application of Emergent Information Processing: Solution Reached Faster Than is Size of Problem, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/......

- Zheng, L.; Handsrush-Wang, S.; Ye, Z.; Wang, B. Liquid metal droplets enabled soft robots. Applied Materials Today 2022, 27, 101423. [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; Times Books, 2nd ed., 1982; p. 468.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).