Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

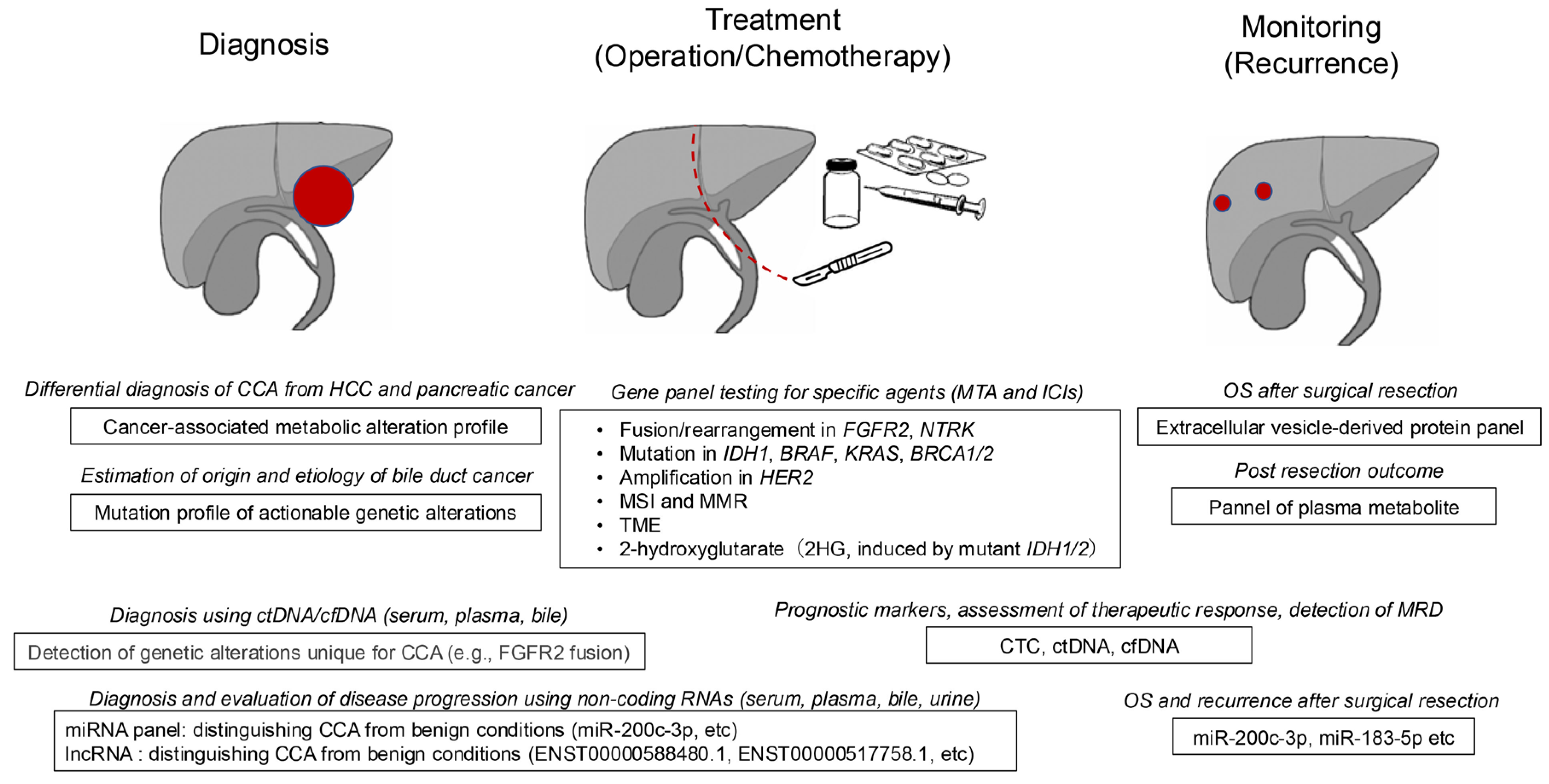

2. Serum and Plasma Biomarkers for Cholangiocarcinoma

3. Genetic Aberrations in Cholangiocarcinoma

4. Molecular-Targeted Therapies and Biomarkers

4.1. FGFR2 Gene Fusions/Rearrangements

4.2. Mutations in the IDH Gene

4.3. Activating Mutations in the KRAS and BRAF Genes

4.4. HER2 Gene Amplification/Overexpression

4.5. Other Biomarkers for Molecular Targeted Agents

5. Emerging Biomarkers and Their Future Perspectives

5.1. Tumor Cells and Cell-Free DNA in Peripheral Blood

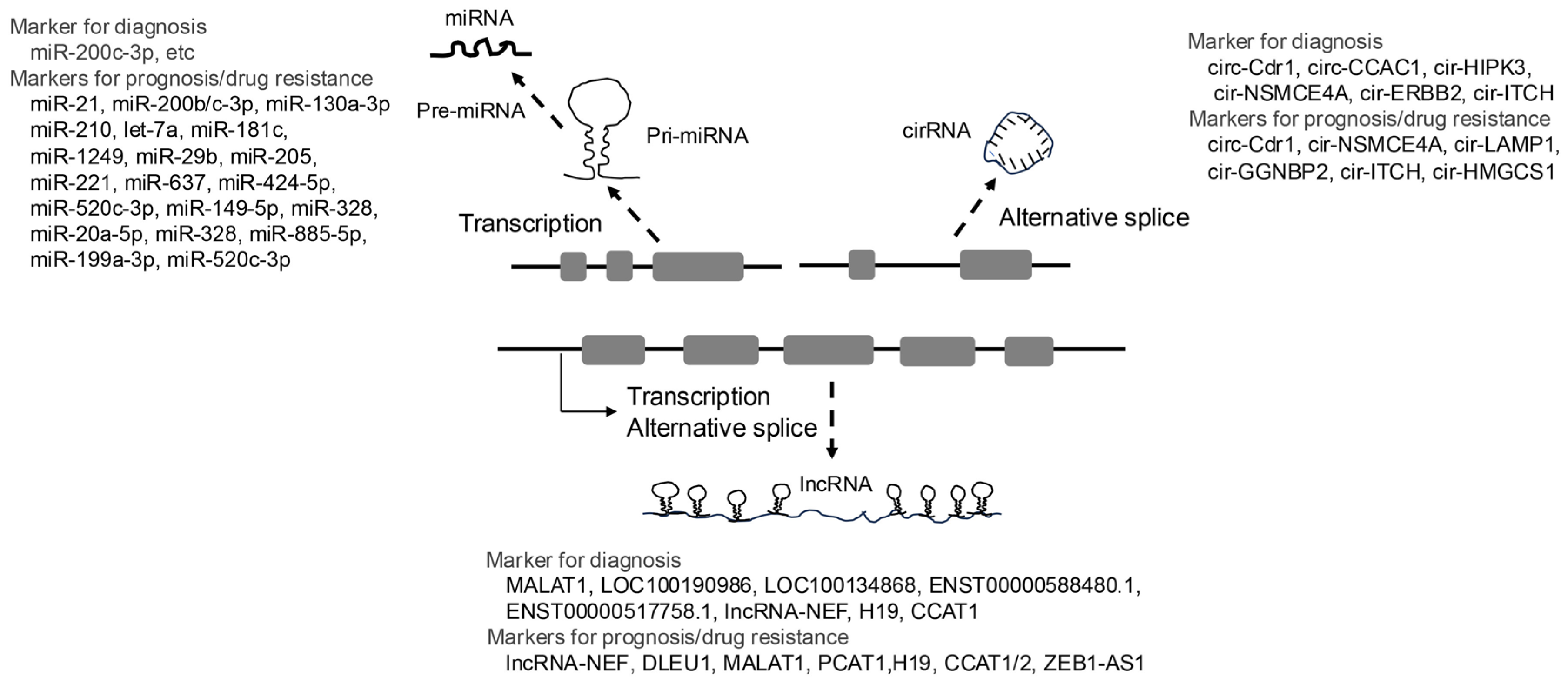

5.2. Non-Coding RNAs

5.2.1. MicroRNAs

5.2.2. LncRNAs

5.2.3. CircRNAs

6. Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Treatment Using Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA19-9 | Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| CCA | Cholangiocarcinoma |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| dCCA | Distal CCA |

| CA19-9 | Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| CTCs | Circulating tumor cells |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| dMMR | Mismatch repair deficiency |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecules |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCCs | Hepatocellular carcinomas |

| iCCA | Intrahepatic CCA |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| MMP-7 | Matrix metalloproteinase-7 |

| MTAs | Molecular targeted agents |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| ORR | Objective response rate |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PARP | Poly ADP-ribose polymerase |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| TILs | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TME | Tumor immune microenvironment |

References

- Izquierdo-Sanchez, L.; Lamarca, A.; La Casta, A.; Buettner, S.; Utpatel, K.; Klumpen, H.J.; Adeva, J.; Vogel, A.; Lleo, A.; Fabris, L.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma landscape in Europe: Diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic insights from the ENSCCA Registry. J Hepatol. 2022, 76, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlus, C.L.; Arrive, L.; Bergquist, A.; Deneau, M.; Forman, L.; Ilyas, S.I.; Lunsford, K.E.; Martinez, M.; Sapisochin, G.; Shroff, R.; et al. AASLD practice guidance on primary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2023, 77, 659–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhong, L.; He, Q.; Wang, S.; Pan, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Y. Diagnostic Accuracy of Serum CA19-9 in Patients with Cholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2015, 21, 3555–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, R.I.R.; Cardinale, V.; Kendall, T.J.; Avila, M.A.; Guido, M.; Coulouarn, C.; Braconi, C.; Frampton, A.E.; Bridgewater, J.; Overi, D.; et al. Clinical relevance of biomarkers in cholangiocarcinoma: critical revision and future directions. Gut. 2022, 71, 1669–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tot, T. Adenocarcinomas metastatic to the liver: the value of cytokeratins 20 and 7 in the search for unknown primary tumors. Cancer. 1999, 85, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, R.; Suzuki, H.; Lemaitre, L.; Kubota, N.; Hoshida, Y. Molecular and immune landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma to guide therapeutic decision-making. Hepatology. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tot, T. Identifying colorectal metastases in liver biopsies: the novel CDX2 antibody is less specific than the cytokeratin 20+/7- phenotype. Med Sci Monit. 2004, 10, BR139–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uenishi, T.; Yamazaki, O.; Tanaka, H.; Takemura, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Tanaka, S.; Nishiguchi, S.; Kubo, S. Serum cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA21-1) as a prognostic factor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008, 15, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Chen, W.; Liang, P.; Hu, W.; Zhang, K.; Shen, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Han, Y.; et al. Serum CYFRA 21-1 in Biliary Tract Cancers: A Reliable Biomarker for Gallbladder Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2015, 60, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelawat, K.; Narong, S.; Wannaprasert, J.; Ratanashu-ek, T. Prospective study of MMP7 serum levels in the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 4697–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirica, A.E. Matricellular proteins in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Adv Cancer Res. 2022, 156, 249–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loosen, S.H.; Roderburg, C.; Kauertz, K.L.; Pombeiro, I.; Leyh, C.; Benz, F.; Vucur, M.; Longerich, T.; Koch, A.; Braunschweig, T.; et al. Elevated levels of circulating osteopontin are associated with a poor survival after resection of cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017, 67, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goydos, J.S.; Brumfield, A.M.; Frezza, E.; Booth, A.; Lotze, M.T.; Carty, S.E. Marked elevation of serum interleukin-6 in patients with cholangiocarcinoma: validation of utility as a clinical marker. Ann Surg. 1998, 227, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matull, W.R.; Andreola, F.; Loh, A.; Adiguzel, Z.; Deheragoda, M.; Qureshi, U.; Batra, S.K.; Swallow, D.M.; Pereira, S.P. MUC4 and MUC5AC are highly specific tumour-associated mucins in biliary tract cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008, 98, 1675–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitz, A.; Azkargorta, M.; Milkiewicz, P.; Olaizola, P.; Zhuravleva, E.; Grimsrud, M.M.; Schramm, C.; Arbelaiz, A.; O’Rourke, C.J.; La Casta, A.; et al. Liquid biopsy-based protein biomarkers for risk prediction, early diagnosis, and prognostication of cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2023, 79, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banales, J.M.; Inarrairaegui, M.; Arbelaiz, A.; Milkiewicz, P.; Muntane, J.; Munoz-Bellvis, L.; La Casta, A.; Gonzalez, L.M.; Arretxe, E.; Alonso, C.; et al. Serum Metabolites as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Cholangiocarcinoma, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Hepatology. 2019, 70, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, R.I.R.; Munoz-Bellvis, L.; Sanchez-Martin, A.; Arretxe, E.; Martinez-Arranz, I.; Lapitz, A.; Gutierrez, M.L.; La Casta, A.; Alonso, C.; Gonzalez, L.M.; et al. A Novel Serum Metabolomic Profile for the Differential Diagnosis of Distal Cholangiocarcinoma and Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urman, J.M.; Herranz, J.M.; Uriarte, I.; Rullan, M.; Oyon, D.; Gonzalez, B.; Fernandez-Urien, I.; Carrascosa, J.; Bolado, F.; Zabalza, L.; et al. Pilot Multi-Omic Analysis of Human Bile from Benign and Malignant Biliary Strictures: A Machine-Learning Approach. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Shu, M.; Liao, J.; Liang, R.; Liu, S.; Kuang, M.; Peng, S.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, Q. Identification and validation of a plasma metabolomics-based model for risk stratification of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023, 149, 12365–12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Arai, Y.; Totoki, Y.; Shirota, T.; Elzawahry, A.; Kato, M.; Hama, N.; Hosoda, F.; Urushidate, T.; Ohashi, S.; et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet. 2015, 47, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javle, M.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Jain, A.; Wang, Y.; Kelley, R.K.; Wang, K.; Kang, H.C.; Catenacci, D.; Ali, S.; Krishnan, S.; et al. Biliary cancer: Utility of next-generation sequencing for clinical management. Cancer. 2016, 122, 3838–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jusakul, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Yong, C.H.; Lim, J.Q.; Huang, M.N.; Padmanabhan, N.; Nellore, V.; Kongpetch, S.; Ng, A.W.T.; Ng, L.M.; et al. Whole-Genome and Epigenomic Landscapes of Etiologically Distinct Subtypes of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1116–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardell, C.P.; Fujita, M.; Yamada, T.; Simbolo, M.; Fassan, M.; Karlic, R.; Polak, P.; Kim, J.; Hatanaka, Y.; Maejima, K.; et al. Genomic characterization of biliary tract cancers identifies driver genes and predisposing mutations. J Hepatol. 2018, 68, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umemoto, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Oikawa, R.; Takeda, H.; Doi, A.; Horie, Y.; Arai, H.; Ogura, T.; Mizukami, T.; Izawa, N.; et al. The Molecular Landscape of Pancreatobiliary Cancers for Novel Targeted Therapies From Real-World Genomic Profiling. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlingue, L.; Malka, D.; Allorant, A.; Massard, C.; Ferte, C.; Lacroix, L.; Rouleau, E.; Auger, N.; Ngo, M.; Nicotra, C.; et al. Precision medicine for patients with advanced biliary tract cancers: An effective strategy within the prospective MOSCATO-01 trial. Eur J Cancer. 2017, 87, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdaguer, H.; Sauri, T.; Acosta, D.A.; Guardiola, M.; Sierra, A.; Hernando, J.; Nuciforo, P.; Miquel, J.M.; Molero, C.; Peiro, S.; et al. ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets Driving Targeted Treatment in Patients with Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1662–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, F.; Remon, J.; Mateo, J.; Westphalen, C.B.; Barlesi, F.; Lolkema, M.P.; Normanno, N.; Scarpa, A.; Robson, M.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol. 2020, 31, 1491–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruki, Y.; Morizane, C.; Arai, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Ueno, M.; Ioka, T.; Naganuma, A.; Furukawa, M.; Mizuno, N.; Uwagawa, T.; et al. Molecular detection and clinicopathological characteristics of advanced/recurrent biliary tract carcinomas harboring the FGFR2 rearrangements: a prospective observational study (PRELUDE Study). J Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N. The role of FGFR inhibitors in the treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma-unveiling the future challenges in drug therapy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2023, 12, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckart, J.; Rasmusen, V.; Talib, Z.; GnanaDev, D.A.; Rahnemai-Azar, A.A. Emerging Therapies in Management of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Sahai, V.; Hollebecque, A.; Vaccaro, G.; Melisi, D.; Al-Rajabi, R.; Paulson, A.S.; Borad, M.J.; Gallinson, D.; Murphy, A.G.; et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javle, M.; Roychowdhury, S.; Kelley, R.K.; Sadeghi, S.; Macarulla, T.; Weiss, K.H.; Waldschmidt, D.T.; Goyal, L.; Borbath, I.; El-Khoueiry, A.; et al. Infigratinib (BGJ398) in previously treated patients with advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 fusions or rearrangements: mature results from a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 6, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, L.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Hollebecque, A.; Valle, J.W.; Morizane, C.; Karasic, T.B.; Abrams, T.A.; Furuse, J.; Kelley, R.K.; Cassier, P.A.; et al. Futibatinib for FGFR2-Rearranged Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, L.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Hollebecque, A.; Valle, J.W.; Morizane, C.; Karasic, T.B.; Abrams, T.A.; Furuse, J.; Kelley, R.K.; Cassier, P.A.; et al. Plain language summary of the FOENIX-CCA2 study: futibatinib for people with advanced bile duct cancer. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 2811–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N.; Aoki, T.; Morita, M.; Chishina, H.; Takita, M.; Ida, H.; Hagiwara, S.; Minami, Y.; Ueshima, K.; Kudo, M. Non-Inflamed Tumor Microenvironment and Methylation/Downregulation of Antigen-Presenting Machineries in Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N.; Kudo, M. Genetic/Epigenetic Alteration and Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Transforming the Immune Microenvironment with Molecular-Targeted Agents. Liver Cancer. 2024, 13, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borger, D.R.; Goyal, L.; Yau, T.; Poon, R.T.; Ancukiewicz, M.; Deshpande, V.; Christiani, D.C.; Liebman, H.M.; Yang, H.; Kim, H.; et al. Circulating oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a potential surrogate biomarker in patients with isocitrate dehydrogenase-mutant intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Macarulla, T.; Javle, M.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Lubner, S.J.; Adeva, J.; Cleary, J.M.; Catenacci, D.V.; Borad, M.J.; Bridgewater, J.; et al. Ivosidenib in IDH1-mutant, chemotherapy-refractory cholangiocarcinoma (ClarIDHy): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, V.; Kreitman, R.J.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Gazzah, A.; Lassen, U.; Stein, A.; Wen, P.Y.; Dietrich, S.; de Jonge, M.J.A.; Blay, J.Y.; et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in BRAFV600E-mutated rare cancers: the phase 2 ROAR trial. Nat Med. 2023, 29, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javle, M.; Borad, M.J.; Azad, N.S.; Kurzrock, R.; Abou-Alfa, G.K.; George, B.; Hainsworth, J.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Swanton, C.; Sweeney, C.J.; et al. Pertuzumab and trastuzumab for HER2-positive, metastatic biliary tract cancer (MyPathway): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2a, multiple basket study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1290–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J.J.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Shah, R.H.; Murphy, J.J.; Cleary, J.M.; Shapiro, G.I.; Quinn, D.I.; Brana, I.; Moreno, V.; Borad, M.; et al. Antitumour activity of neratinib in patients with HER2-mutant advanced biliary tract cancers. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, J.J.; Fan, J.; Oh, D.Y.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, J.W.; Chang, H.M.; Bao, L.; Sun, H.C.; Macarulla, T.; Xie, F.; et al. Zanidatamab for HER2-amplified, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer (HERIZON-BTC-01): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2b study. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohba, A.; Morizane, C.; Kawamoto, Y.; Komatsu, Y.; Ueno, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Ikeda, M.; Sasaki, M.; Furuse, J.; Okano, N.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Expressing Biliary Tract Cancer (HERB; NCCH1805): A Multicenter, Single-Arm, Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42, 3207–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A.; Le, D.T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Delord, J.P.; Geva, R.; Gottfried, M.; Penel, N.; Hansen, A.R.; et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients With Noncolorectal High Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cancer: Results From the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; Shah, M.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Chung, H.C.; Kindler, H.L.; Lopez-Martin, J.A.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroeidi, I.A.; Burghofer, J.; Kalbourtzis, S.; Taghizadeh, H.; Webersinke, G.; Piringer, G.; Kasper, S.; Schreil, G.; Liffers, S.T.; Reichinger, A.; et al. Understanding homologous recombination repair deficiency in biliary tract cancers: clinical implications and correlation with platinum sensitivity. ESMO Open. 2024, 9, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.S.; DuBois, S.G.; Kummar, S.; Farago, A.F.; Albert, C.M.; Rohrberg, K.S.; van Tilburg, C.M.; Nagasubramanian, R.; Berlin, J.D.; Federman, N.; et al. Larotrectinib in patients with TRK fusion-positive solid tumours: a pooled analysis of three phase 1/2 clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebele, R.C.; Drilon, A.; Paz-Ares, L.; Siena, S.; Shaw, A.T.; Farago, A.F.; Blakely, C.M.; Seto, T.; Cho, B.C.; Tosi, D.; et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Shen, L.; Luo, M.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. Circulating tumor cells: biology and clinical significance. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D.; Campion, M.B.; Liu, M.C.; Chaiteerakij, R.; Giama, N.H.; Ahmed Mohammed, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, C.; Campion, V.L.; Jen, J.; et al. Circulating tumor cells are associated with poor overall survival in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2016, 63, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.H.; Yeh, T.S.; Wu, R.C.; Yeh, C.N.; Yeh, C.T. GALNT14 genotype is associated with perineural invasion, lymph node metastasis and overall survival in resected cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017, 13, 4215–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Shao, S.; Sun, H.; Zhu, H.; Fang, H. Bile-derived exosome noncoding RNAs as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for cholangiocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 985089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uson Junior, P.L.S.; Majeed, U.; Yin, J.; Botrus, G.; Sonbol, M.B.; Ahn, D.H.; Starr, J.S.; Jones, J.C.; Babiker, H.; Inabinett, S.R.; et al. Cell-Free Tumor DNA Dominant Clone Allele Frequency Is Associated With Poor Outcomes in Advanced Biliary Cancers Treated With Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022, 6, e2100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Xin, H.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, Z.; Sun, R.; Yao, N.; Sun, Q.; Borjigin, U.; Wu, X.; Fan, J.; et al. Tumor-derived exosomes induce immunosuppressive macrophages to foster intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma progression. Hepatology. 2022, 76, 982–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurje, I.; Czigany, Z.; Bednarsch, J.; Gaisa, N.T.; Dahl, E.; Knuchel, R.; Miller, H.; Ulmer, T.F.; Strnad, P.; Trautwein, C.; et al. Genetic Variant of CXCR1 (rs2234671) Associates with Clinical Outcome in Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022, 11, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, K.; Shi, A.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D.; et al. Bile exosomal miR-182/183-5p increases cholangiocarcinoma stemness and progression by targeting HPGD and increasing PGE2 generation. Hepatology. 2024, 79, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, J.W.; Wasan, H.; Lopes, A.; Backen, A.C.; Palmer, D.H.; Morris, K.; Duggan, M.; Cunningham, D.; Anthoney, D.A.; Corrie, P.; et al. Cediranib or placebo in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine chemotherapy for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (ABC-03): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.V.; Pokuri, V.K.; Groman, A.; Ma, W.W.; Malhotra, U.; Iancu, D.M.; Grande, C.; Saab, T.B. A Multicenter Phase II Study of Gemcitabine, Capecitabine, and Bevacizumab for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Biliary Tract Cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018, 41, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frundt, T.; von Felden, J.; Krause, J.; Heumann, A.; Li, J.; Riethdorf, S.; Pantel, K.; Huber, S.; Lohse, A.W.; Wege, H.; et al. Circulating tumor cells as a preoperative risk marker for occult metastases in patients with resectable cholangiocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 941660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, P.; Chiang, N.J.; Bandaru, A.; Sinha, A.; Huang, W.Y.; Hung, S.C.; Shan, Y.S.; Lee, G.B. Exploring Circulating Tumor Cells in Cholangiocarcinoma Using a Novel Glycosaminoglycan Probe on a Microfluidic Platform. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020, 9, e1901875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.L.; Huang, C.J.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chiang, N.J.; Huang, Y.S.; Hung, S.C.; Shan, Y.S.; Lee, G.B. An integrated microfluidic system for automatic detection of cholangiocarcinoma cells from bile. Lab Chip. 2024, 24, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rompianesi, G.; Di Martino, M.; Gordon-Weeks, A.; Montalti, R.; Troisi, R. Liquid biopsy in cholangiocarcinoma: Current status and future perspectives. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021, 13, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarca, A.; Kapacee, Z.; Breeze, M.; Bell, C.; Belcher, D.; Staiger, H.; Taylor, C.; McNamara, M.G.; Hubner, R.A.; Valle, J.W. Molecular Profiling in Daily Clinical Practice: Practicalities in Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma and Other Biliary Tract Cancers. J Clin Med. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Taniguchi, H.; Ikeda, M.; Bando, H.; Kato, K.; Morizane, C.; Esaki, T.; Komatsu, Y.; Kawamoto, Y.; Takahashi, N.; et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA sequencing in advanced gastrointestinal cancer: SCRUM-Japan GI-SCREEN and GOZILA studies. Nat Med. 2020, 26, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintachai, P.; Lim, J.Q.; Techasen, A.; Lert-Itthiporn, W.; Kongpetch, S.; Loilome, W.; Chindaprasirt, J.; Titapun, A.; Namwat, N.; Khuntikeo, N.; et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Circulating Cell-Free DNA for Cholangiocarcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Oki, E.; Kobayashi, S.; Yuda, J.; Shibuki, T.; Bando, H.; Yoshino, T. Bridging horizons beyond CIRCULATE-Japan: a new paradigm in molecular residual disease detection via whole genome sequencing-based circulating tumor DNA assay. Int J Clin Oncol. 2024, 29, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, K.; Cleary, S.P. A Review of Circulating Tumor DNA in Hepatobiliary Malignancies. Front Oncol. 2018, 8, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettrich, T.J.; Schwerdel, D.; Dolnik, A.; Beuter, F.; Blatte, T.J.; Schmidt, S.A.; Stanescu-Siegmund, N.; Steinacker, J.; Marienfeld, R.; Kleger, A.; et al. Genotyping of circulating tumor DNA in cholangiocarcinoma reveals diagnostic and prognostic information. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, R.; Kurzrock, R.; Mallory, R.J.; Fanta, P.T.; Burgoyne, A.M.; Clary, B.M.; Kato, S.; Sicklick, J.K. Comprehensive genomic landscape and precision therapeutic approach in biliary tract cancers. Int J Cancer. 2021, 148, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchuck, J.E.; Facchinetti, F.; DiToro, D.F.; Baiev, I.; Majeed, U.; Reyes, S.; Chen, C.; Zhang, K.; Sharman, R.; Uson Junior, P.L.S.; et al. The clinical landscape of cell-free DNA alterations in 1671 patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022, 33, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzrock, R.; Aggarwal, C.; Weipert, C.; Kiedrowski, L.; Riess, J.; Lenz, H.J.; Gandara, D. Prevalence of ARID1A Mutations in Cell-Free Circulating Tumor DNA in a Cohort of 71,301 Patients and Association with Driver Co-Alterations. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.J.; Ivanics, T.; Gravely, A.; Gallinger, S.; Sapisochin, G.; O’Kane, G.M. Optimizing Circulating Tumour DNA Use in the Perioperative Setting for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Diagnosis, Screening, Minimal Residual Disease Detection and Treatment Response Monitoring. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023, 30, 3849–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedeld, H.M.; Folseraas, T.; Lind, G.E. Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis - The promise of DNA methylation and molecular biomarkers. JHEP Rep. 2020, 2, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.A.; Richards, D.; Cohn, A.; Tummala, M.; Lapham, R.; Cosgrove, D.; Chung, G.; Clement, J.; Gao, J.; Hunkapiller, N.; et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann Oncol. 2021, 32, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.B.; Mahler, M.S.K.; Andersen, R.F.; Jensen, L.H.; Raunkilde, L. The Clinical Impact of Methylated Homeobox A9 ctDNA in Patients with Non-Resectable Biliary Tract Cancer Treated with Erlotinib and Bevacizumab. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasi, P.M.; Lee, J.K.; Pasquina, L.W.; Decker, B.; Vanden Borre, P.; Pavlick, D.C.; Allen, J.M.; Parachoniak, C.; Quintanilha, J.C.F.; Graf, R.P.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Enables Sensitive Detection of Actionable Gene Fusions and Rearrangements Across Cancer Types. Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Oropeza, R.; Melendez-Zajgla, J.; Maldonado, V.; Vazquez-Santillan, K. The emerging role of lncRNAs in the regulation of cancer stem cells. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2018, 41, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhu, B.; Meng, D.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. Down-regulation of lncRNA-NEF indicates poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Biosci Rep. 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Henson, R.; Lang, M.; Wehbe, H.; Maheshwari, S.; Mendell, J.T.; Jiang, J.; Schmittgen, T.D.; Patel, T. Involvement of human micro-RNA in growth and response to chemotherapy in human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. Gastroenterology. 2006, 130, 2113–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Chen, G.; Xia, Q.; Shao, S.; Fang, H. Exosomal miR-200 family as serum biomarkers for early detection and prognostic prediction of cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019, 12, 3870–3876. [Google Scholar]

- Asukai, K.; Kawamoto, K.; Eguchi, H.; Konno, M.; Asai, A.; Iwagami, Y.; Yamada, D.; Asaoka, T.; Noda, T.; Wada, H.; et al. Micro-RNA-130a-3p Regulates Gemcitabine Resistance via PPARG in Cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017, 24, 2344–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Jiang, J.; Yu, Y.; Tian, R.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Shen, M.; Xu, M.; Zhu, F.; Shi, C.; et al. Direct targeting of SUZ12/ROCK2 by miR-200b/c inhibits cholangiocarcinoma tumourigenesis and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2013, 109, 3092–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, P.; Hedayat, S.; Fassan, M.; Cardinale, V.; Lampis, A.; Guzzardo, V.; Vicentini, C.; Scarpa, A.; Cascione, L.; Costantini, D.; et al. Modulation of Biliary Cancer Chemo-Resistance Through MicroRNA-Mediated Rewiring of the Expansion of CD133+ Cells. Hepatology. 2020, 72, 982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silakit, R.; Kitirat, Y.; Thongchot, S.; Loilome, W.; Techasen, A.; Ungarreevittaya, P.; Khuntikeo, N.; Yongvanit, P.; Yang, J.H.; Kim, N.H.; et al. Potential role of HIF-1-responsive microRNA210/HIF3 axis on gemcitabine resistance in cholangiocarcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0199827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Qin, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Geng, X.; Yue, H. Long non-coding RNA LINC00665 promotes gemcitabine resistance of Cholangiocarcinoma cells via regulating EMT and stemness properties through miR-424-5p/BCL9L axis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, T.; Tsutsumi, K.; Ueta, E.; Oda, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Ako, S.; Fujii, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Uchida, D.; Matsumoto, K.; et al. MicroRNA-451a inhibits gemcitabine-refractory biliary tract cancer progression by suppressing the MIF-mediated PI3K/AKT pathway. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2023, 34, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuhisa, A.; Tsunedomi, R.; Kimura, Y.; Nakajima, M.; Nishiyama, M.; Takahashi, H.; Ioka, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Eguchi, H.; Nagano, H. Exosomal miR-141-3p Induces Gemcitabine Resistance in Biliary Tract Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2024, 44, 2899–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Hou, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Yu, T.; Zhang, W. LncRNA FALEC increases the proliferation, migration and drug resistance of cholangiocarcinoma through competitive regulation of miR-20a-5p/SHOC2 axis. Aging (Albany NY). 2023, 15, 3759–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, D.; Li, F.; Qiu, G.; Sun, D.; Zeng, Z. Lnc-PKD2-2-3/miR-328/GPAM ceRNA Network Induces Cholangiocarcinoma Proliferation, Invasion and 5-FU Chemoresistance. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 871281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Xu, S.; Tang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Miao, L. The ATO/miRNA-885-5p/MTPN axis induces reversal of drug-resistance in cholangiocarcinoma. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2021, 44, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xia, X.; Ji, J.; Ma, J.; Tao, L.; Mo, L.; Chen, W. MiR-199a-3p enhances cisplatin sensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells by inhibiting mTOR signaling pathway and expression of MDR1. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 33621–33630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, L.; Ji, D.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Y. SP1-induced HOXD-AS1 promotes malignant progression of cholangiocarcinoma by regulating miR-520c-3p/MYCN. Aging (Albany NY). 2020, 12, 16304–16325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J.T. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018, 172, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapitz, A.; Arbelaiz, A.; O’Rourke, C.J.; Lavin, J.L.; Casta, A.; Ibarra, C.; Jimeno, J.P.; Santos-Laso, A.; Izquierdo-Sanchez, L.; Krawczyk, M.; et al. Patients with Cholangiocarcinoma Present Specific RNA Profiles in Serum and Urine Extracellular Vesicles Mirroring the Tumor Expression: Novel Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers for Disease Diagnosis. Cells. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Wang, Y.; Nie, J.; Li, Q.; Tang, L.; Deng, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, B.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. The diagnostic/prognostic potential and molecular functions of long non-coding RNAs in the exosomes derived from the bile of human cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 69995–70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Y.; Kang, P.; Huang, P.; Meng, N.; Wang, H.; Zheng, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. YY1-induced DLEU1/miR-149-5p Promotes Malignant Biological Behavior of Cholangiocarcinoma through Upregulating YAP1/TEAD2/SOX2. Int J Biol Sci. 2022, 18, 4301–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Kong, L.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Guan, Q.; Cao, X.; Zhu, W.; Ou, K.; et al. The Plasma LncRNA Acting as Fingerprint in Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018, 49, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wan, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Leng, K.; Kang, P.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, X. Long noncoding RNA PCAT1 regulates extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma progression via the Wnt/beta-catenin-signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017, 94, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Cui, Y. Overexpression of long noncoding RNA H19 indicates a poor prognosis for cholangiocarcinoma and promotes cell migration and invasion by affecting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017, 92, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.W.; Ye, H.; Wei, P.P.; He, B.; Han, C.; Chen, Z.H.; Chen, Y.Q.; Wang, W.T. Global identification and characterization of lncRNAs that control inflammation in malignant cholangiocytes. BMC Genomics. 2018, 19, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.M.; Li, Z.L.; Li, J.L.; Zheng, W.Y.; Li, X.H.; Cui, Y.F.; Sun, D.J. LncRNA CCAT1 as the unfavorable prognostic biomarker for cholangiocarcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017, 21, 1242–1247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.G.; Tang, R.F.; Shang, J.F.; Qi, S.; Yu, G.D.; Sun, C. Upregulation of long non-coding RNA CCAT2 indicates a poor prognosis and promotes proliferation and metastasis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2018, 17, 5328–5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Hu, Z.; Guan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Cui, Y. AR-induced ZEB1-AS1 represents poor prognosis in cholangiocarcinoma and facilitates tumor stemness, proliferation and invasion through mediating miR-133b/HOXB8. Aging (Albany NY). 2020, 12, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angenard, G.; Merdrignac, A.; Louis, C.; Edeline, J.; Coulouarn, C. Expression of long non-coding RNA ANRIL predicts a poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2019, 51, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.P.; Song, J.; Liu, G.T.; Wang, J.J.; Guo, H.F. Upregulation of gastric adenocarcinoma predictive long intergenic non-coding RNA promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2018, 16, 3964–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, W.; Guan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiang, X. Long Non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 Promotes Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion in Cholangiocarcinoma Through Regulating miR-760/E2F3 Axis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022, 67, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.M.; Li, Z.L.; Li, J.L.; Xu, Y.; Leng, K.M.; Cui, Y.F.; Sun, D.J. A novel prognostic biomarker for cholangiocarcinoma: circRNA Cdr1as. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018, 22, 365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Leng, K.; Yao, Y.; Kang, P.; Liao, G.; Han, Y.; Shi, G.; Ji, D.; Huang, P.; Zheng, W.; et al. A Circular RNA, Cholangiocarcinoma-Associated Circular RNA 1, Contributes to Cholangiocarcinoma Progression, Induces Angiogenesis, and Disrupts Vascular Endothelial Barriers. Hepatology. 2021, 73, 1419–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, B.; Gu, D.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Su, Y. Circ-0000284 arouses malignant phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma cells and regulates the biological functions of peripheral cells through cellular communication. Clin Sci (Lond). 2019, 133, 1935–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Wen, Z.; Cao, L.; Chen, Y.; Xue, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, D. Tumor-associated macrophages promote cholangiocarcinoma progression via exosomal Circ_0020256. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, P.; Wang, Z.; Su, Z.; Liao, G.; Han, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhong, X. Circ-LAMP1 contributes to the growth and metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma via miR-556-5p and miR-567 mediated YY1 activation. J Cell Mol Med. 2021, 25, 3226–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Lan, T.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Dai, J.; Xu, L.; Cai, Y.; Hou, G.; Xie, K.; Liao, M.; et al. IL-6-induced cGGNBP2 encodes a protein to promote cell growth and metastasis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2022, 75, 1402–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, S.; Liu, L.; Sun, D.; Li, W.; Jiang, X. Upregulation of circ_0059961 suppresses cholangiocarcinoma development by modulating miR-629-5p/SFRP2 axis. Pathol Res Pract. 2022, 234, 153901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.P.; Dong, Z.N.; Wang, S.W.; Zheng, Y.M.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F.; Peng, R.; et al. circHMGCS1-016 reshapes immune environment by sponging miR-1236-3p to regulate CD73 and GAL-8 expression in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Ruth He, A.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; Kim, J.W.; Suksombooncharoen, T.; Ah Lee, M.; Kitano, M.; et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.K.; Ueno, M.; Yoo, C.; Finn, R.S.; Furuse, J.; Ren, Z.; Yau, T.; Klumpen, H.J.; Chan, S.L.; Ozaka, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (KEYNOTE-966): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023, 401, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, S.; Rapoud, D.; Dos Santos, A.; Gonzalez, P.; Desterke, C.; Pascal, G.; Elarouci, N.; Ayadi, M.; Adam, R.; Azoulay, D.; et al. Identification of Four Immune Subtypes Characterized by Distinct Composition and Functions of Tumor Microenvironment in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2020, 72, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Serrano, M.A.; Kepecs, B.; Torres-Martin, M.; Bramel, E.R.; Haber, P.K.; Merritt, E.; Rialdi, A.; Param, N.J.; Maeda, M.; Lindblad, K.E.; et al. Novel microenvironment-based classification of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with therapeutic implications. Gut. 2023, 72, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ma, J.; Zhu, K.; Yu, L.; Zheng, B.; Rao, D.; Zhang, S.; Dong, L.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, X.; et al. Spatial immunophenotypes predict clinical outcome in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. JHEP Rep. 2023, 5, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montironi, C.; Castet, F.; Haber, P.K.; Pinyol, R.; Torres-Martin, M.; Torrens, L.; Mesropian, A.; Wang, H.; Puigvehi, M.; Maeda, M.; et al. Inflamed and non-inflamed classes of HCC: a revised immunogenomic classification. Gut. 2023, 72, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Peng, L.; Dong, L.; Liu, D.; Ma, J.; Lin, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, P.; Song, G.; Zhang, M.; et al. Geospatial Immune Heterogeneity Reflects the Diverse Tumor-Immune Interactions in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 2350–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, K.; Jain, P.; El-Refai, S.M.; Azad, N.S.; Zabransky, D.J.; Baretti, M.; Shroff, R.T.; Kelley, R.K.; El-Khouiery, A.B.; Hockenberry, A.J.; et al. Clinical, Genomic, and Transcriptomic Data Profiling of Biliary Tract Cancer Reveals Subtype-Specific Immune Signatures. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022, 6, e2100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T.F. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015, 523, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Shapiro, B.; Vucic, E.A.; Vogt, S.; Bar-Sagi, D. Tumor Cell-Derived IL1beta Promotes Desmoplasia and Immune Suppression in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, M.; Ascierto, P.A.; Manzyuk, L.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Penel, N.; Cassier, P.A.; Bariani, G.M.; De Jesus Acosta, A.; Doi, T.; Longo, F.; et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient cancers: updated analysis from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Ann Oncol. 2022, 33, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggs, L.P.; Ruf, B.; Ma, C.; Heinrich, B.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Q.; McVey, J.C.; Wabitsch, S.; Heinrich, S.; Rosato, U.; et al. CD40-mediated immune cell activation enhances response to anti-PD-1 in murine intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabitsch, S.; Tandon, M.; Ruf, B.; Zhang, Q.; McCallen, J.D.; McVey, J.C.; Ma, C.; Green, B.L.; Diggs, L.P.; Heinrich, B.; et al. Anti-PD-1 in Combination With Trametinib Suppresses Tumor Growth and Improves Survival of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in Mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 12, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.; Obi, S.; Zhou, J.; Tateishi, R.; Qin, S.; Zhao, H.; Otsuka, M.; Ogasawara, S.; George, J.; Chow, P.K.H.; et al. APASL clinical practice guidelines on systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma-2024. Hepatol Int. 2024, 18, 1661–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address, e.e.e.; European Association for the Study of the, L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2025, 82, 315–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hao, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, S.; Yuan, Y. Bile liquid biopsy in biliary tract cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2023, 551, 117593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Q.; Zhang, C.Z.; Sun, Z.H.; Wu, L.G.; Chen, Y.; Mo, Z.Q.; Mai, Q.C.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.X.; Shi, F.; et al. Cell-free DNA from bile outperformed plasma as a potential alternative to tissue biopsy in biliary tract cancer. ESMO Open. 2021, 6, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedeld, H.M.; Grimsrud, M.M.; Andresen, K.; Pharo, H.D.; von Seth, E.; Karlsen, T.H.; Honne, H.; Paulsen, V.; Farkkila, M.A.; Bergquist, A.; et al. Early and accurate detection of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis by methylation markers in bile. Hepatology. 2022, 75, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Qian, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X.; et al. Liquid Biopsy-Based Accurate Diagnosis and Genomic Profiling of Hard-to-Biopsy Tumors via Parallel Single-Cell Genomic Sequencing of Exfoliated Tumor Cells. Anal Chem. 2024, 96, 14669–14678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).