Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Animals

3.2. Diagnosis

3.3. Diuretic Treatment and Clinical Outcome

3.4. Adverse Reactions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mullens, W.; Damman, K.; Harjola, V.P.; Mebazaa, A.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Martens, P.; Testani, J.M.; Tang, W.H.W.; Orso, F.; Rossignol, P.; et al. The use of diuretics in heart failure with congestion - a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2019, 21, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, M.A.; Adin, D. Toward quantification of loop diuretic responsiveness for congestive heart failure. J Vet Intern Med 2023, 37, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keene, B.W.; Atkins, C.E.; Bonagura, J.D.; Fox, P.R.; Haggstrom, J.; Fuentes, V.L.; Oyama, M.A.; Rush, J.E.; Stepien, R.; Uechi, M. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2019, 33, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poissonnier, C.; Ghazal, S.; Passavin, P.; Alvarado, M.P.; Lefort, S.; Trehiou-Sechi, E.; Saponaro, V.; Barbarino, A.; Delle Cave, J.; Marchal, C.R.; et al. Tolerance of torasemide in cats with congestive heart failure: a retrospective study on 21 cases (2016-2019). BMC Vet Res 2020, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buggey, J.; Mentz, R.J.; Pitt, B.; Eisenstein, E.L.; Anstrom, K.J.; Velazquez, E.J.; O'Connor, C.M. A reappraisal of loop diuretic choice in heart failure patients. Am Heart J 2015, 169, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.R.; MacAllister, R.; Sofat, R. Intravenous Furosemide for Acute Decompensated Congestive Heart Failure: What Is the Evidence? Clin Pharmacol Ther 2015, 98, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adin, D.; Atkins, C.; Papich, M.G. Pharmacodynamic assessment of diuretic efficacy and braking in a furosemide continuous infusion model. J Vet Cardiol 2018, 20, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnoush, A.H.; Khalaji, A.; Naderi, N.; Ashraf, H.; von Haehling, S. ACC/AHA/HFSA 2022 and ESC 2021 guidelines on heart failure comparison. ESC Heart Fail 2023, 10, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, D.H.; Felker, G.M. Diuretic Treatment in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 1964–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoorn, E.J.; Ellison, D.H. Diuretic Resistance. Am J Kidney Dis 2017, 69, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porciello, F.; Rishniw, M.; Ljungvall, I.; Ferasin, L.; Haggstrom, J.; Ohad, D.G. Sleeping and resting respiratory rates in dogs and cats with medically-controlled left-sided congestive heart failure. Vet J 2016, 207, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonagura, J.D.T., D. C. Management of heart failure in dogs; Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2009; pp. 769–779. [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs, S.M.; Rishniw, M. Dermatologic adverse effect of subcutaneous furosemide administration in a dog. J Vet Intern Med 2013, 27, 1248–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacharias, H.; Raw, J.; Nunn, A.; Parsons, S.; Johnson, M. Is there a role for subcutaneous furosemide in the community and hospice management of end-stage heart failure? Palliat Med 2011, 25, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Ukai, Y.; Kanakubo, K.; Yamano, S.; Lee, J.; Kurosawa, T.A.; Uechi, M. Comparison of the diuretic effect of furosemide by different methods of administration in healthy dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2015, 25, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, V.; Fang, J.C. Gastrointestinal and Liver Issues in Heart Failure. Circulation 2016, 133, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.; Desai, A.; Jamil, A.; Csendes, D.; Gutlapalli, S.D.; Prakash, K.; Swarnakari, K.M.; Bai, M.; Manoharan, M.P.; Raja, R.; et al. Re-defining the Gut Heart Axis: A Systematic Review of the Literature on the Role of Gut Microbial Dysbiosis in Patients With Heart Failure. Cureus 2023, 15, e34902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandek, A.; Bauditz, J.; Swidsinski, A.; Buhner, S.; Weber-Eibel, J.; von Haehling, S.; Schroedl, W.; Karhausen, T.; Doehner, W.; Rauchhaus, M.; et al. Altered intestinal function in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007, 50, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Larouche-Lebel, E.; Loughran, K.A.; Huh, T.P.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Oyama, M.A. Metabolomics analysis reveals deranged energy metabolism and amino acid metabolic reprogramming in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e018923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, R.; Iwanaga, K.; Ueda, K.; Isaka, M. Intestinal Complication With Myxomatous Mitral Valve Diseases in Chihuahuas. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 777579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlin, E.T.; Rush, J.E.; Freeman, L.M. A pilot study investigating circulating trimethylamine N-oxide and its precursors in dogs with degenerative mitral valve disease with or without congestive heart failure. J Vet Intern Med 2019, 33, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Larouche-Lebel, E.; Loughran, K.A.; Huh, T.P.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Oyama, M.A. Gut Dysbiosis and Its Associations with Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Dogs with Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease. mSystems 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoldi, C.; Aspidi, F.; Romito, G. Dermatologic adverse effect of subcutaneous furosemide administration in a cat. Open Vet J 2023, 13, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.A.; Muntendam, P.; Myers, R.L.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Sale, M.E.; de Boer, R.A.; Pitt, B. Subcutaneous Furosemide in Heart Failure: Pharmacokinetic Characteristics of a Newly Buffered Solution. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2018, 3, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa, P.G.; Arribas, M.T.; Mena, J.M.; Perez, M.G. Cutaneous adverse reaction to furosemide treatment: new clinical findings. Can Vet J 2006, 47, 576–578. [Google Scholar]

- Ladlow, J. Injection site-associated sarcoma in the cat: treatment recommendations and results to date. J Feline Med Surg 2013, 15, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, D.H. Clinical Pharmacology in Diuretic Use. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 14, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luis Fuentes, V.; Abbott, J.; Chetboul, V.; Cote, E.; Fox, P.R.; Haggstrom, J.; Kittleson, M.D.; Schober, K.; Stern, J.A. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of cardiomyopathies in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2020, 34, 1062–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, L.M.; Rush, J.E.; Farabaugh, A.E.; Must, A. Development and evaluation of a questionnaire for assessing health-related quality of life in dogs with cardiac disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005, 226, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.M.; Rush, J.E.; Oyama, M.A.; MacDonald, K.A.; Cunningham, S.M.; Bulmer, B.; MacGregor, J.M.; Laste, N.J.; Malakoff, R.L.; Hall, D.J.; et al. Development and evaluation of a questionnaire for assessment of health-related quality of life in cats with cardiac disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012, 240, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damman, K.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Coster, J.E.; Krikken, J.A.; van Deursen, V.M.; Krijnen, H.K.; Hofman, M.; Nieuwland, W.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Voors, A.A.; et al. Clinical importance of urinary sodium excretion in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2020, 22, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subject | Breed | Sex | Age (years) |

Weight (Kg) |

Diagnosis | CHF | SRR T2 | Diuretic T2 | Oral Diuretic dose (mg/kg/day) |

Other therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog 1 | Beagle | FN | 10 | 14.0 | MMVD | PE | 80 | Torasemide | 0.4 | Benazepril, Spironolactone, Pimobendan, Digoxin |

| Dog 2 | Chihuahua | M | 8 | 7.4 | MMVD | PE | 68 | Furosemide | 3 | Benazepril, Spironolactone, Pimobendan |

| Dog 3 | Chihuahua | F | 9 | 4.9 | MMVD | PE | 72 | Furosemide | 6 | Benazepril, Spironolactone, Pimobendan |

| Dog 4 | JRT | MN | 10 | 8.1 | MMVD | PE | 45 | Furosemide | 7.25 | Benazepril, Spironolactone, Pimobendan, Codeine |

| Dog 5 | Labrador | MN | 11 | 33.2 | AVDys + AF | PE; Ascites | 60 | Furosemide | 3.6 | Benazepril, Spironolactone, Pimobendan, Sotalol |

| Dog 6 | Labrador | FN | 11 | 37.7 | MMVD + AF | Ascites | 30 | Furosemide | 8 | Benazepril, Spironolactone, Pimobendan, Digoxin, Diltiazem |

| Dog 7 | CKCS | FN | 6 | 7.3 | MMVD | PE | 32 | Furosemide | 8 | Benazepril, Spironolactone, Pimobendan |

| Dog 8 | DDB | FN | 8 | 49.3 | TVDys + AF | PLE; Ascites | 40 | Furosemide | 8.2 | Pimobendan, Spironolactone, Digoxin, Diltiazem |

| Dog 9 | Bulldog | MN | 6 | 22.3 | ARVC | Ascites | 44 | Furosemide | 6 | Pimobendan, Spironolactone, Amiodarone |

| Dog 10 | CKCS | MN | 8 | 9.0 | MMVD | PE | 60 | Torasemide | 0.2 | Pimobendan, Benazepril, Spironolactone |

| Dog 11 | Beagle | FN | 12 | 10.0 | MMVD + PH | PE | 50 | Torasemide | 0.15 | Pimobendan, Benazepril, Spironolactone |

| Dog 12 | Chihuahua | MN | 6 | 3.2 | MMVD | PE | 45 | Torasemide | 0.5 | Pimobendan, Benazepril, Spironolactone, Digoxin |

| Dog 13 | CKCS | MN | 11 | 11.3 | MMVD | PE | 32 | Furosemide | 2 | Pimobendan, Benazepril, Spironolactone |

| Subject | Breed | Sex | Age (years) |

Weight (Kg) |

Diagnosis | CHF | SRR T2 | Oral Diuretic T2 | Diuretic dose (mg/kg/day) |

Other therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat 1 | DSH | MN | 7 | 5.2 | MVDys | PE | 49 | Torasemide | 0.2 | Spironolactone, Clopidogrel |

| Cat 2 | Bengal | FN | 3 | 3.5 | AS | PE | 68 | Furosemide | 6.4 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 3 | Sphynx | MN | 4 | 3.5 | HCM + SAM | PE | 80 | Torasemide | 0.25 | None |

| Cat 4 | Scottish | MN | 1 | 3.9 | HCM | PE | 50 | Torasemide | 0.25 | None |

| Cat 5 | Siberian | MN | 8 | 3.9 | ESC | PE | 52 | Furosemide | 4 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 6 | DSH | MN | 11 | 6.0 | ESC | PE | 64 | Furosemide | 6.6 | Pimobendan, Clopiodogrel, Sotalol |

| Cat 7 | DSH | MN | 1 | 5.6 | HCM | PE, PCE | 60 | Furosemide | 3.6 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 8 | BSH | FN | 1 | 3.1 | HCM | PE | 44 | Furosemide | 4 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 9 | DSH | MN | 4 | 4.0 | VSD | PE | 48 | Torasemide | 0.25 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 10 | DSH | MN | 10 | 6.0 | HCM | PLE | 60 | Torasemide | 0.5 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 11 | Scottish | MN | 1 | 5.0 | MVDys + SAM | PE | 45 | Furosemide | 5 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 12 | BSH | MN | 5 | 5.2 | TVDys + AF | PLE, Ascites | 44 | Furosemide | 8 | Spironolactone, Clopidogrel |

| Cat 13 | Sphynx | FN | 12 | 3.4 | RCM | PLE | 72 | Furosemide | 6 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 14 | DSH | MN | 15 | 3.5 | RCM | PLE | 40 | Furosemide | 5.7 | Pimobendan, Clopidogrel |

| Cat 15 | DSH | MN | 14 | 4.8 | RCM + AF | PE, PLE | 38 | Furosemide | 6 | Clopidogrel |

| Cat 16 | DSH | MN | 7 | 4.6 | ESC | PLE, PE | 48 | Furosemide | 6 | Pimobendan, Clopidogrel |

| Cat 17 | DSH | MN | 11 | 5.0 | HCM + SAM | PLE | 44 | Furosemide | 3 | Clopidogrel, Benazepril, Spironolactone |

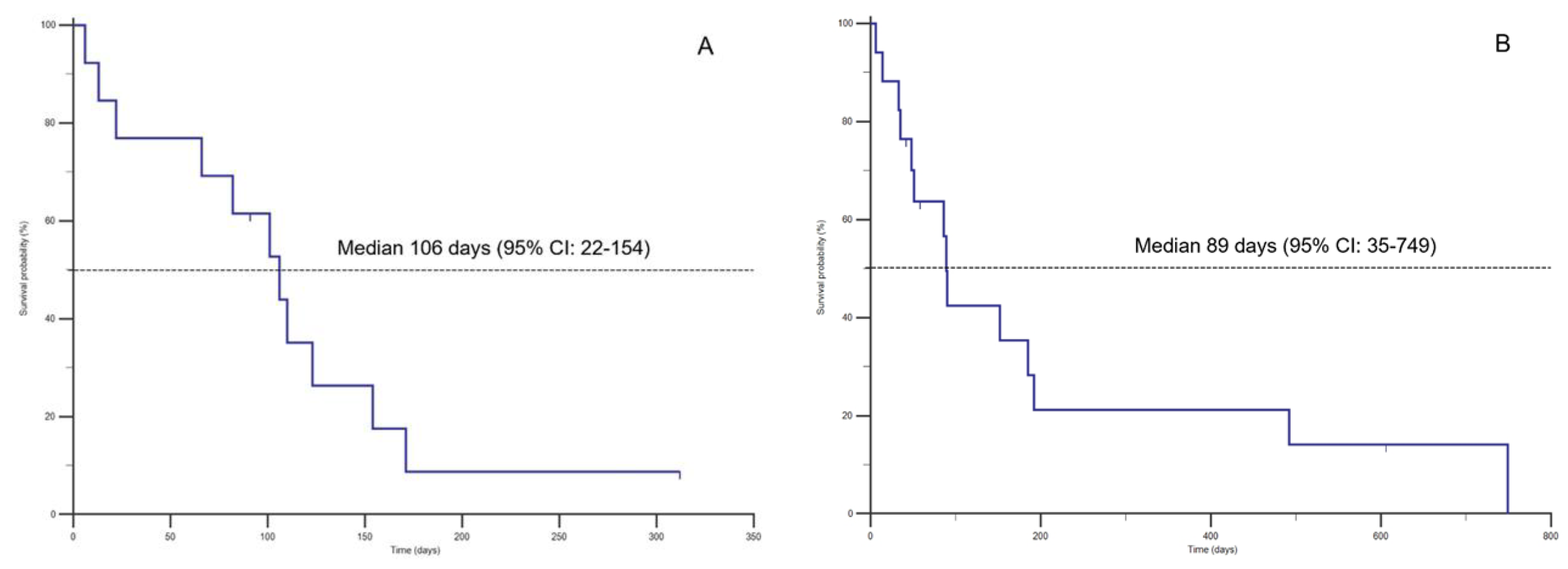

| A | |||||

| Patients | T1-T2 (days) | T2-T3 (days) | SC Furosemide dose T3 (mg/Kg/day) | Adverse reactions (T2-T3) | Cause of death |

| Dog 1 | 177 | 106 | 8.4 | Mild skin reaction (alopecia/irritation) | Euthanasia |

| Dog 2 | 71 | 6 | 4.0 | Sudden death | |

| Dog 3 | 36 | 66 | 6.0 | Sudden death | |

| Dog 4 | 32 | 22 | 7.8 | Euthanasia | |

| Dog 5 | 180 | 82 | 4.0 | Euthanasia | |

| Dog 6 | 148 | 123 | 7.4 | Euthanasia | |

| Dog 7 | 39 | 13 | 9.0 | Sudden death | |

| Dog 8 | 163 | 171 | 6.6 | Sudden death | |

| Dog 9 | 65 | 110 | 4.0 | Sudden death | |

| Dog 10 | 178 | 91 | 5.5 | Moderate skin reaction (scratching, alopecia, temporary lump) | Alive |

| Dog 11 | 203 | 101 | 4.0 | Euthanasia | |

| Dog 12 | 41 | 312 | 4.4 | Alive | |

| Dog 13 | 12 | 154 | 4.4 | Euthanasia | |

| B | |||||

| Patients | T1-T2 (days) | T2-T3 (days) | SC Furosemide dose T3 (mg/Kg/day) | Adverse reactions (T2-T3) | Cause of death |

| Cat 1 | 139 | 492 | 4 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 2 | 15 | 6 | 6.4 | Sudden death | |

| Cat 3 | 35 | 749 | 4 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 4 | 19 | 48 | 6 | Sudden death | |

| Cat 5 | 5 | 192 | 6 | Moderate skin reaction (scratching, alopecia, pyoderma) | Sudden death |

| Cat 6 | 129 | 90 | 7.5 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 7 | 31 | 51 | 4.6 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 8 | 38 | 35 | 4 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 9 | 5 | 185 | 4 | Sudden death | |

| Cat 10 | 130 | 152 | 5 | Moderate skin reaction (scratching, alopecia and pyoderma) | Euthanasia |

| Cat 11 | 9 | 504 | 6 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 12 | 135 | 89 | 4 | Sudden death | |

| Cat 13 | 13 | 14 | 5.6 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 14 | 155 | 33 | 4.0 | Euthanasia | |

| Cat 15 | 356 | 42 | 4.0 | Mild skin irritation; scratching | Alive |

| Cat 16 | 72 | 58 | 3.4 | Alive | |

| Cat 17 | 343 | 86 | 2.0 | Euthanasia | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).