1. Introduction

Work in forestry is recognized as one of the most physically demanding professions, requiring extensive manual labor in challenging outdoor environments [

1]. The manual and moto manual work involves extensive physical labor, including walking long distances over uneven terrain, lifting different loads, and tree-cutting, delimbing, crosscutting, manual axe chopping, and cutting with a chainsaw including different cutting conditions. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), forestry employment is characterized by high working load conditions and physically demanding tasks [

2]. This demanding nature of forestry work poses significant risks for incidents, acute injuries, and musculoskeletal strain, particularly in the lower extremities and spine. Forestry workers are exposed to a variety of risks due to the nature of their work environment and the tools they use. Prolonged movement through difficult forest terrain can lead to slips, trips, and falls, which are common causes of injury in this sector. These types of accidents are arising based on statistics in 25-38% of the overall accidents [

3,

4,

5]. To focus on a slip, trip, and fall accident root-cause analysis there could be several points that may lead to the accident or injury. If we skip all technical, organizational, and work behavioral reasons, one of the main causes concerning the work demand could be the accumulative effect of terrain and terrain conditions on energy consumption, physical and muscle workload, and fatigue [

6]. The handling of chainsaws and other loads adds another layer of physical strain, as these tools are heavy, require a high level of manual dexterity, and often need to be transported across variable terrains [

7]. This also leads from the other side to impact workers' ability to maintain stability and adapt to changes in terrain and terrain conditions [

8].

In the past 10 years, some laboratory-based studies have attempted to simulate human locomotion in different terrains by having tested subjects walk on different devices like treadmills or test lines with different surfaces consisting of regularly spaced obstacles. These studies tried to simulate obstacles like unleveled bumps, hard and soft materials, loose rocks, etc.. to predict the changes in Gait parameters [

9,

10].

Research has generally shown that, compared to walking on regular flat surfaces, individuals exhibit greater variability in stride characteristics, such as step length and width [

11,

12]. They also adopt flatter foot postures at initial contact, increase foot clearance during the leg swing phase [

13], and show higher leg muscle activation [

12,

14], when walking on irregular surfaces. These adaptations are believed to help maintain balance and prevent tripping on uneven terrain.

Several laboratory Studies show that movement patterns, body, and walking stability are considerably influenced by the physical demands, environmental conditions, body load, and conditions of their work [

15,

16]. Some studies also focus on the impact of the urban walking environment. Walking on varied surfaces such as concrete, asphalt, gravel, sand, or grass, requires less specific adjustments to gait mechanics to ensure stability [

17]. However, as surface stability decreases—as seen on gravel or sand—gait parameters adjust to compensate for increased instability and unevenness [

18]. There were also studies focused on typical urban irregular and uneven surfaces, upstairs/downstairs, and slope up/ down walking [

19]. Previous scientific studies have shown that gait adaptations utilized when walking on irregular surfaces may reflect reduced stability and increased fall risk. Terrain can significantly influence foot motion during walking. It may also impact factors such as average stride length and width [

20]. Walking on uneven terrain often necessitates lifting the foot higher during the mid-swing phase [

21], which increases energy expenditure [

22]. Additionally, maintaining balance may be more difficult on certain terrains, prompting stabilizing adjustments [

23], including modifications in foot placement [

24,

25].

Laboratory-based, urban, and some test studies on artificially created environments indicate that human locomotion interacts with terrain surfaces. However, such studies typically record subjects walking on even surfaces, irregular terrains our species encounters, or treadmills that do not represent the irregular terrains in natural Mid-European / European forestry environments.

Only a limited number of studies have explored walking kinematics in complex, naturally irregular, environments outside of laboratory settings, controlled or test-designed environments.

Based on the kinematic movement study provided in forest terrains of the Bolivian Amazon [

26] we expect that movement in the forestry environment will require highly adaptive movement strategies to maintain balance avoid body instability and differentiate Gait structure in comparison to a flat, stable surface.

Gait analysis is a crucial tool in understanding how different surfaces impact walking mechanics. Gait parameters, such as step length, stride duration, and Body-ground reaction, are influenced by the type of surface an individual walks on. Solid surfaces like pavements provide consistent support, leading to more stable and predictable gait patterns.

In contrast, uneven surfaces such as forestry trails and mixed environments introduce variability that can significantly alter these parameters [

27]. Based on the above-mentioned studies is evident that soft and uneven surfaces, such as loose soil, rocks, and roots, increase step variability. This variability is due to the body's need to adapt to changing ground conditions, which affects stability and movement efficiency [

28].

Our primary hypothesis expects that gait parameters will vary significantly between solid external surfaces, forestry trails, and mixed forestry environments. Soft surfaces, loose forestry soil, rocks, and roots will result in an increase in step variability compared to solid external surfaces and forestry trails.

Dynamic stability refers to the ability to maintain balance during movement, which is crucial for preventing slips, trips, and falls. The risk of slips, trips, and falls, as indicated by dynamic stability metrics and ground reaction force variability, will be higher on loose or uneven forestry soil and root-covered terrains compared to solid surfaces or forestry trails.

Body-ground interaction and movement stabilities are the forces exerted by the ground on the body during walking and are key indicators of dynamic stability. On uneven surfaces, Body-ground interaction and movement parameters become more variable, reflecting the increased challenge of maintaining balance [

29].

The secondary hypotheses propose that the risk of slips, trips, and falls will be higher on uneven forestry soil and root-covered terrains compared to solid surfaces or forestry trails. This is because uneven surfaces disrupt the normal gait cycle, requiring greater adjustments in posture and movement to maintain stability.

2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventional studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

2.1. Methods

The recent development of wearable Motion-tracking, Motion-capturing technologies, and non-invasive biological data collection open various possibilities for human research work in exterior environments. Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) are wearable motion-tracking devices that are pivotal in advancing gait and locomotion analysis. Unlike traditional optical measurement methods which we may mostly use in laboratory environments, wearable IMUs enable researchers and clinicians to collect detailed movement data in outdoor and real-world settings, enhancing the possibility of the data collection and the validity of assessments [

30,

31]. By capturing metrics such as acceleration, angular velocity, and orientation, IMUs allow for a comprehensive evaluation of gait parameters, including stride length, cadence, and stability, even on varied and uneven terrains. This flexibility makes IMUs an essential tool for studying natural locomotion and understanding movement adaptations in diverse environments [

32].

To collect participants' movement and gait data, we utilized the MVN Awinda motion capture (MoCap) system, equipped with 17 IMU sensors, developed by Xsens/Movella. This system is versatile, supporting applications in medical, clinical, sports, ergonomics, and scientific research.

The MVN Awinda IMUs integrate accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers, allowing for the estimation of body segment position and orientation through sensor fusion [

33]. Using this data, joint kinematics can be accurately calculated. Motion capture is recorded at a sampling rate of 60 Hz, with 17 IMUs strategically placed on the head, sternum, pelvis, upper legs, lower legs, feet, shoulders, upper arms, forearms, and hands, enabling comprehensive full-body motion analysis.

The raw data from all sensors are collected using the Xsens MVN recording software. Before conducting any trials or body motion measurements, the anthropometrical body segment dimensions of each participant must be entered into the software. These dimensions are measured using a measuring tape while the participant stands upright. Measurements include the distances of the ankle, knee, hip, and top of the head from the ground, as well as the inter-ASIS (pelvis width), inter-acromion (shoulder width), inter-dactylion (upper arm width), and foot length.

To ensure accurate and stable measurements, the IMU system must be calibrated before each measurement session or as required by the conditions. Calibration involves the participant assuming a neutral pose, such as an N-pose, followed by a walk calibration. The Xsens MVN software then calculates the orientation of body segments by combining individual IMU data with a biomechanical model of the human body. Each IMU orientation is determined by fusing signals from accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. This sensor-to-segment calibration establishes the kinematics of 23 body segments. Once calibrated, the participant can undergo 3D motion analysis, which may include walking at various gait speeds (e.g., slow, self-selected, or fast). The motion capture data is then used to generate a comprehensive gait report.

2.2. Measurement Environment

The experiment took 3 days in 08/2024 place outdoors at a camp area close to the village Zubri in the Czech mid-forest area at 672 m above sea level. The experiment was performed in the average meteorological conditions of 25,7 °C/ 53% humidity, wind 1,2 m/s, and light values 530 lx. All participants walked in a designated marked walking space with minimal terrain variation, negligible visible undulations, and minimal cross-slope.

In our preliminary study, we measured healthy adults walking on three types of outdoor surfaces: solid surfaces, forest trails, and forest environments (see

Figure 1).

2.3. Participants

Fifteen adult participants with an average age of 38 with no reported history of injuries or musculoskeletal neurological conditions, that affected their locomotion, gait, or posture in the previous two years volunteered for this preliminary study. The sample of participants was selected from a group of non-professional sportspeople. All participants provided written consent with personal data and biological data collection. The group of participants consists of 10 men and 5 women with an average height of 173,3 cm and shoe size of 29,03 cm.

2.4. Gait Data Collection and Recording

Before each measurement, the participant's body segments were measured, and all sensors were placed according to the MoCap Awinda placement manual on the participants' body segments and bones. to keep the preciseness of the measurements, the calibration of the sensors and system was done before each set of measurements on each surface.

Each participant was individually instructed with verbal and visual instruction to walk at their normal pace and to let their body and arms move naturally. Participants stood in the starting position till the instruction to walk. To ensure the objectivity of the measurements, the locomotion cycle was left to the individual participants.

Each walking trial was set for a specific distance and walking pattern - see

Table 1:

Surface trials were presented in order of solid external surfaces, forest trails, and forest environments. There was adequate rest provided in between experiment trials to prevent fatigue between trials.

During the whole experiment for every individual participant, also heart rate data were recorded. Those data are not the subject of this analysis.

For the data collection setting, the where necessary to set a data collection and measurement scenario. Within the MVN software, four user scenarios are available which mainly differ in the handling of interactions with the environment (floor interactions). For our purpose the Soft Floor scenario was used. This scenario is intended for cases where floor interaction with a single level floor is important, but the floor is not strictly a zero level, such as when walking on a soft surface as in case of the Forestry soft ground may happened. All raw data files exported from Awinda MTw sensors to the MVN Xsens/ Movella SW are stored in *.mvn format as well as heart data in *.csv stored at the university safety data storage. All data are processed and kept with European and Czech GDPR and legal requirements and legal obligations and requirements of the data keepers and processors.

2.5. Gait Data Analysis

All Gait data were processed using a specialized cloud-based application developed by Xsens/Movella Technologies specifically for gait analysis reporting. This platform was designed to equip the clinical and research community with tools for detailed gait analysis. A clinical Gait report is generated through this system, providing spatial and temporal parameters of the human gait cycle. The cloud-based system ensures secure storage and accessibility, offering several advantages: data processing does not rely on front-end hardware, and users with authorized permissions can securely access reports from any location. This enhances collaboration and communication among interdisciplinary teams.

Xsens MotionCloud now features the new MVN reporting functionality, a tool designed to generate detailed reports using Xsens recording *.mvn or *.mvnx files. These reports facilitate the analysis and interpretation of various kinematic parameters across different tasks. The recording files are securely uploaded to Movella/Xsens MotionCloud, ensuring a reliable and protected environment for data processing. Before processing of the data in Gait analysis report in the Xsens MotionCloud reporting tool, all records were checked once more and HD reprocessing was performed. HD processing mode adds the feature of processing data over a larger time window to get an optimal (and more consistent) estimate of the position and orientation of each body segment to ensure high data accuracy.

Within the Xsens MotionCloud Gait analysis report [

34] is processed 66 Gait parameters in several groups as:

General Parameters

Gait cycle parameters

Spatial Parameters

Temporal Parameters

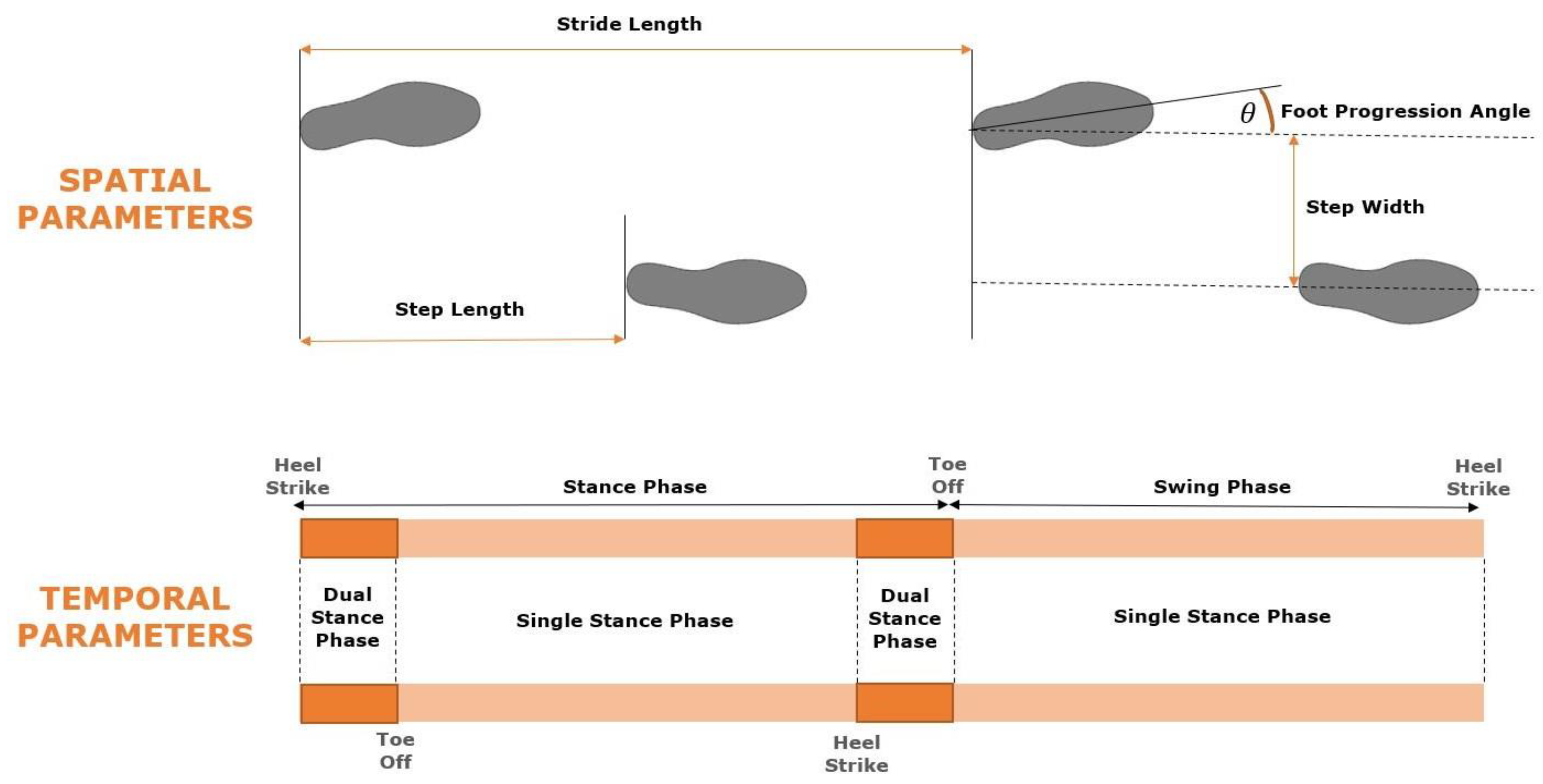

Figure 2.

Spatial and Temporal parameters [

34].

Figure 2.

Spatial and Temporal parameters [

34].

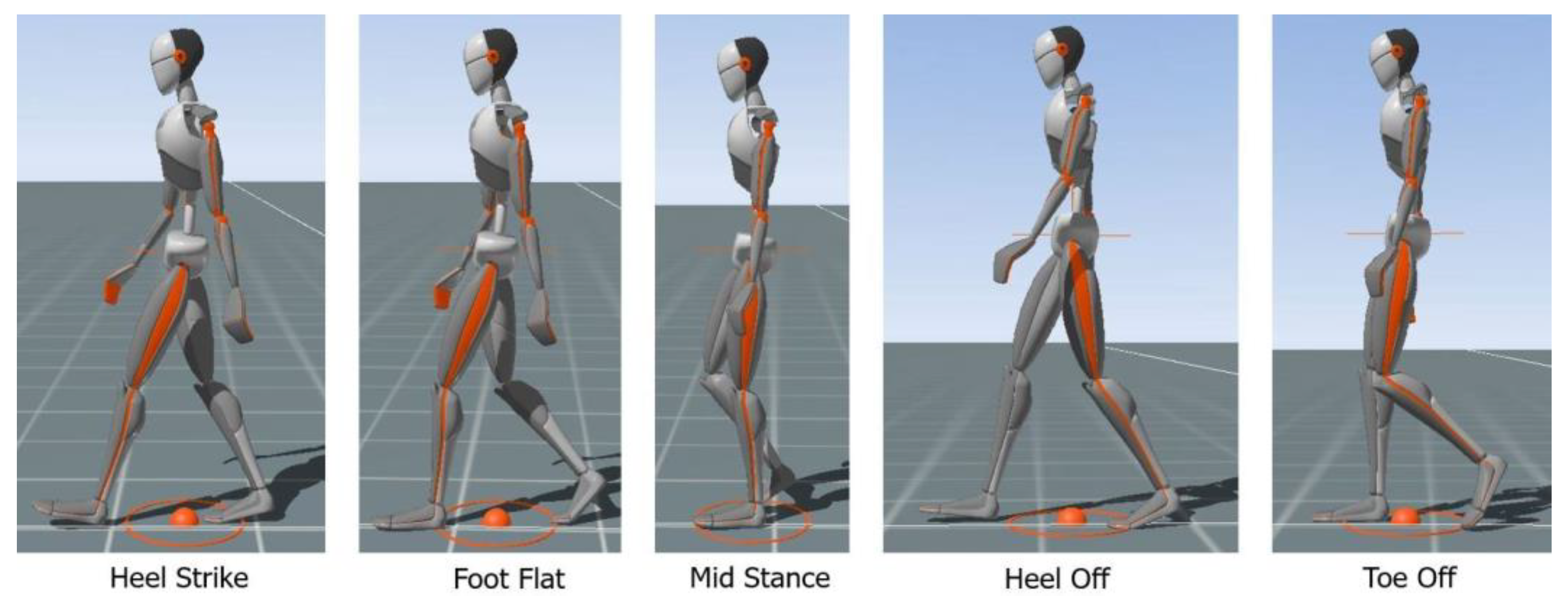

Figure 3.

Specific events of the stance phase for the left leg, with the direction of progression to the left [

34].

Figure 3.

Specific events of the stance phase for the left leg, with the direction of progression to the left [

34].

And 10 different Gait graphical parameters as:

Hip motion patterns

Knee motion patterns

Ankle motion patterns

Pelvis motion patterns

Foot progression angle

Centre of mass tracking

Spatial and temporal parameters provide a basic functional assessment of gait. For a more detailed analysis, the actions and movements of individual lower limb segments and joints can be examined. The events within a gait cycle occur in a consistent sequence, independent of time. This precise coordination is essential for achieving energy-efficient and safe walking.

To support the purpose of this study how human locomotion and Gait parameters change with different terrains, especially on the forest environments, we will investigate only some of the Gait parameters which are linked to the energy-efficient and safe walking as for example:

No of steps

Trial duration

Step speed

Step cadence

Foot strike Heal

Foot strike Toe

Step width

Step length

Stride length

3. Results

In our study, we focus mainly on forestry environments in the coniferous and mixed broadleaved-coniferous forests such as soft surfaces, loose forestry soil, rocks, roots, and solid Forestry surfaces, which we compare with solid external surfaces, Forestry trails.

The purpose of this study was to investigate how human locomotion and Gait parameters change with different terrains, such as solid external surfaces, forest trails, and forest environments with a focus on parameters that may impact human motion stability and are possibly linked to slip, trip, or fall risks.

3.1. Data Analysis and Statistics

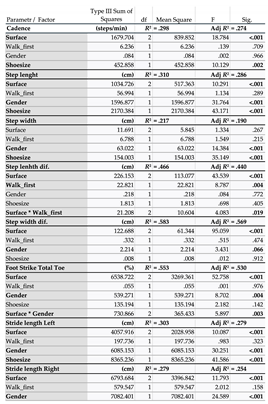

The individual assessed Gait - spatial and temporal parameters of walking are listed in the descriptive statistics of the measurements – see

Table 2:

The above parameters were evaluated and further statistically processed within the framework of the Gait and data analysis.

The results of individual measurements were evaluated and processed using the Xsens/ Movella MotionCloud reporting system - part Gait analysis. Before evaluating the individual parameters of the gait analysis, we conducted a statistical investigation of the significance of the differences and the relevance of the processed data. In addition to examining specific parameters, we used the ANOVA statistical method, with which we tested the significance of the differences in the monitored parameters between the individual monitored factors monitored by the subjects for each terrain surface. We also tested the correlation between the walking parameters for the selected variables/ factors individually.

A significance level of 0.05 was chosen for the evaluation of the test.

The most statistically significant parameters were surface, gender, shoe size, and number of passes - first and following walk on the same surface – see

Table 3.

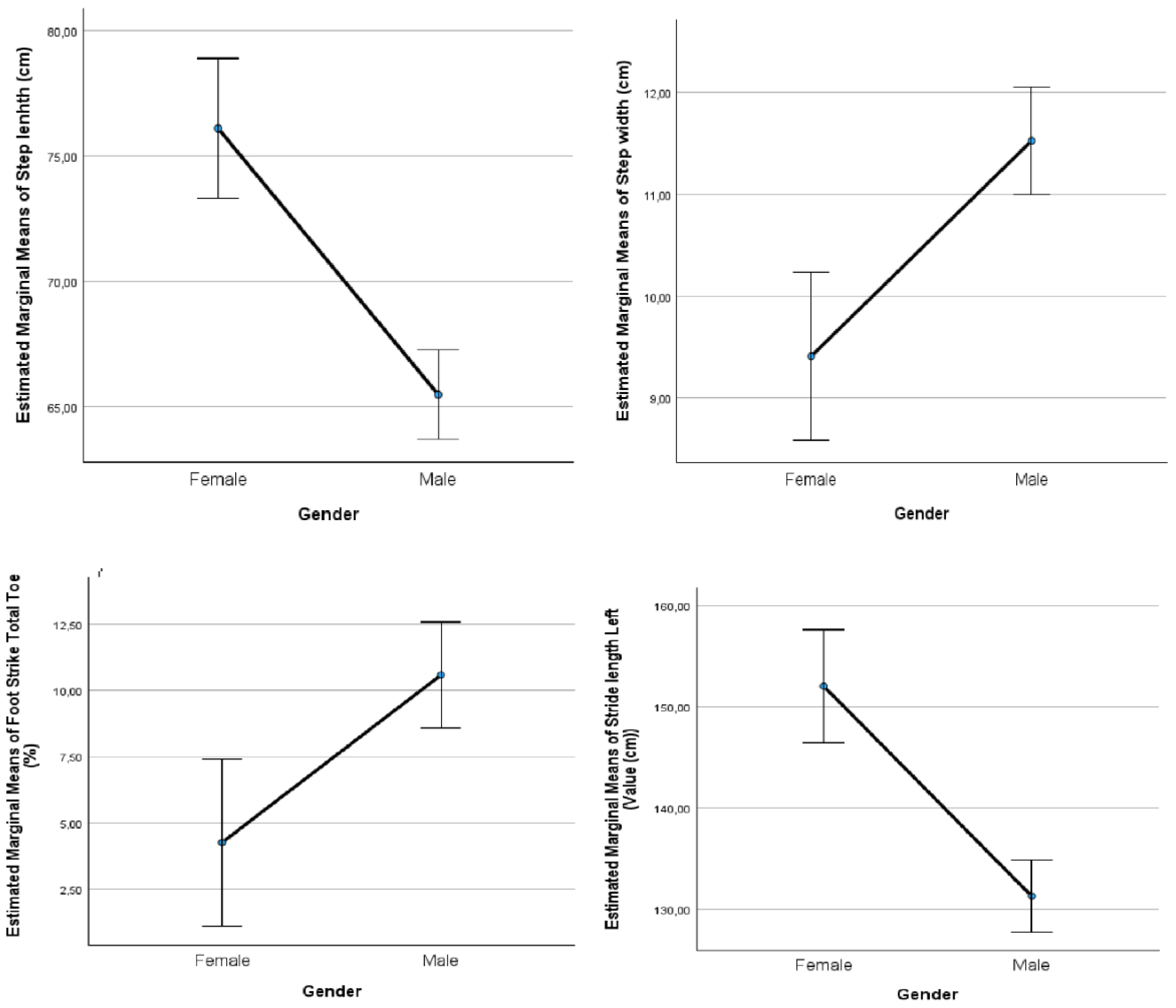

As part of the assessment of the data set, we were primarily interested in significant variables such as gender, foot length, or height had a significant impact on the overall set of processed data. Gender and shoe size support each other, as men are generally taller and have larger feet, and therefore, when it comes to maintaining balance, people with longer feet have a longer contact time with the surface. The analysis shows that these are statistically significant parameters, but they are not parameters that would have a significant impact on the overall results of the gait assessment. However, the results confirm the generally known anthropometric fact that women have, on average, a smaller shoe size and a more massive body base than men.

Figure 4.

Influence of gender on individual evaluated parameters step and stride differences.

Figure 4.

Influence of gender on individual evaluated parameters step and stride differences.

Another parameter that was significant for the actual processing and analysis of gait data was the influence of the neuro-motor learning ability with subsequent adaptation of the body's movement patterns during the first and multiple passages of the tested persons over individual surfaces. If we look at the individual components of the processed gait analysis data, we see that although from an overall perspective, the number of passages over individual terrains is statistically significant, it does not affect the overall results of the individual measured parameters of gait analysis. From the perspective of neuro-motor connections, the connection between the number of passages over individual terrains and small changes in parameters underline the fact that although with the number of repetitions of the same activity, there is a process of changes in the locomotor chain, that on the other hand this chain, including the individual parameters of gait, can be negatively influenced by long-term load on the neuro-motor functions.

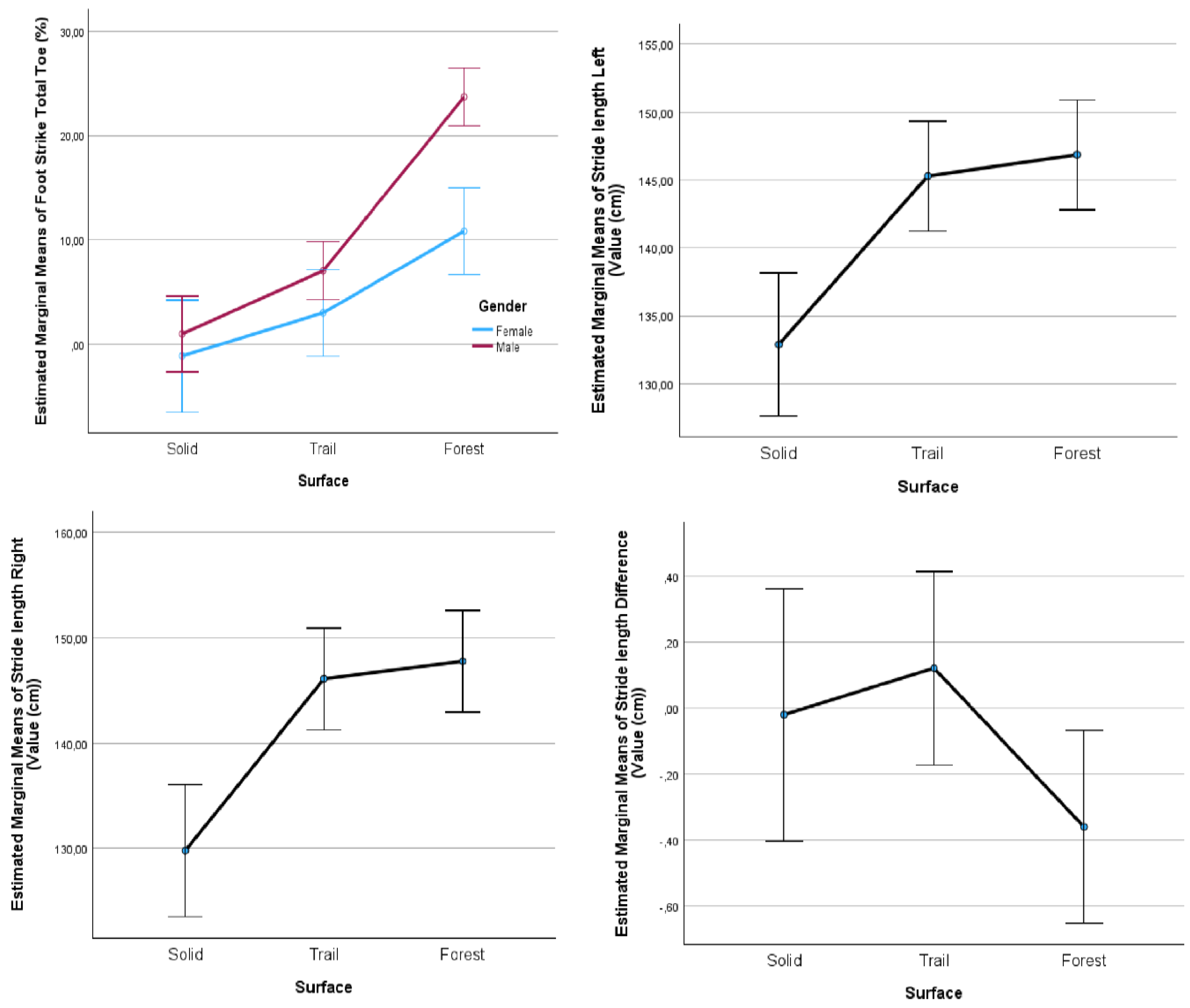

Figure 5.

Influence of Surface on Foot strike Total Toe percentage placement on the surface and stride length parameters.

Figure 5.

Influence of Surface on Foot strike Total Toe percentage placement on the surface and stride length parameters.

Figure 6.

Influence of Surface on step cadence and step length parameters with distribution of the Number of passes on the same surface (First and another walk).

Figure 6.

Influence of Surface on step cadence and step length parameters with distribution of the Number of passes on the same surface (First and another walk).

By statistically comparing the individual measured parameters, we can see how individual surfaces affect the parameters of the Gait analysis. With the increasing difficulty of movement in unstable terrain, which forest surfaces undoubtedly are, there is a significant decrease in Cadence, an increase in Step length and Step width, and an increase in the total contact of the foot with the Foot Strike Toe pad. During locomotion, there are also changes in the body's center of gravity and the ability to properly ensure locomotion in uneven terrain.

For clarity, we present the interpretation of the results of graphic gait parameters such as Pelvis orientation and Center of mass position when walking on individual terrains - Solid surfaces, Forest trails, and Forest environments for one of the study participants:

Pelvis orientation:

Figure 7.

Example of distribution of the pelvis positioning and movement on different surface.

Figure 7.

Example of distribution of the pelvis positioning and movement on different surface.

3.2. Summary of Results

We measured and evaluated the group of 15 participants walking through different terrains, such as solid external surfaces, forest trails, and forest environments. Totally we evaluate 150 trials divided into 30 trials on solid surfaces, 60 trials on forest trails, and 60 trials in forest environment.

With the change of walking surface from solid to forestry Participants made more steps with the longer time frame, but the speed and cadence were slower, steps were wider, and their feet spent more with the touch on the ground - see

Table 4.

Walking through complicated terrain also impacted the Centre of mass position and stability and symmetry of pelvic movement - see chart example –

Figure 8. While walking on Forest Trial and Forest Environment the body of the participants tried to stabilize and compensate for terrain instability by several supportive techniques to ensure safe movement.

The analysis of human gait across three different surface types—solid surface, forest trail, and forest environment—provides key insights into how individuals adjust their movement patterns to maintain stability and reduce the risk of slips, trips, and falls. Variations in gait parameters such as step count, duration, speed, cadence, foot strike, and stride characteristics reflect biomechanical adaptations to the demands of different terrains. Understanding these adaptations is critical for promoting safety and mobility, especially in challenging environments.

On solid surfaces, gait is stable and efficient, marked by fewer steps, shorter duration, and consistent speed (1.10 m/s). The cadence of 103.30 steps/min and a near-exclusive reliance on heel strikes (99.68%) indicate a biomechanically optimal walking pattern. Low variability in step width and stride length further reflects stability provided by the even surface. Fatigue has minimal impact in such environments since the physical demands are relatively low, and energy expenditure remains steady. Solid surfaces, therefore, represent the baseline for safe and efficient locomotion. This minimizes the risk of slips or trips, as consistent gait mechanics are easily maintained.

In contrast, forest trails require individuals to adapt their gait to uneven terrain. The number of steps increases (24.70), and the cadence rises slightly to 107.56 steps/min, reflecting the need for quicker, shorter steps to navigate the irregular ground. While speed slightly increases to 1.24 m/s, step width and step length differences also grow significantly (5.72 cm and 4.92 cm, respectively). The increased variability in these parameters highlights the effort to maintain balance and stability while moving across uneven surfaces. Notably, the percentage of heel strikes decreases to 94.28%, with a corresponding rise in toe strikes (5.72%). This adjustment suggests that individuals rely more on their forefoot to push off and stabilize against potential slips.

The forest environment presents the most challenging conditions, with a higher step count (27.93), longer duration (16.97 s), and reduced speed (1.17 m/s). Cadence decreases to 100.10 steps/min, reflecting a cautious approach to navigation in this complex terrain. Variability in step width (0.63 cm) and step length (5.77 cm) increases further, indicating continuous adjustments to maintain balance. The significant drop in heel strikes (80.59%) and rise in toe strikes (19.41%) illustrate the biomechanical need for more forefoot engagement. This change enhances stability and reduces the likelihood of falls when encountering obstacles like roots or rocks. Stride variability is also evident, with differences of 0.24 cm, underscoring the adaptive nature of gait in such environments.

On solid surfaces, regular gait patterns suffice for stability, while uneven surfaces demand increased focus on balance and foot placement. On forest trails, fatigue may result in irregular steps and an increased reliance on visual feedback to compensate for reduced proprioception. In the forest environment, where physical demands are even higher, fatigue exacerbates the risk of slips, trips, and falls by compromising stability during transitions between irregular surfaces. Moreover, cognitive fatigue from a sustained focus on foot placement obstacle avoidance, and working activity may impair decision-making, leading to missteps or tripping over obstacles.

Physical exertion and fatigue can significantly impair stability, coordination, and gait mechanics. As individuals expend more energy navigating uneven terrain, fatigue may cause muscular weakness, reduced proprioception (awareness of body position), and impaired reflexes, all of which negatively affect balance. These factors lead to increased variability in step and stride length, irregular foot placement, and diminished response times to environmental hazards. Fatigue can also alter foot strike patterns, potentially reducing the effectiveness of forefoot engagement, which is critical for stabilizing the body on uneven ground.

In summary, human movement adapts to terrain-specific challenges by altering gait patterns, engaging different foot strike strategies, and adjusting step and stride variability. These adaptations are essential for maintaining stability and protecting against slips, trips, and falls, especially in environments where the risk of imbalance is heightened.

4. Discussion

Human locomotion is a complex process influenced by various factors, including the type of terrain. Understanding how different terrains affect gait parameters is crucial for assessing motion stability and identifying potential risks of slips, trips, or falls. This article explores the changes in human locomotion and gait parameters when walking on solid external surfaces, forest trails, and forest environments, with a focus on parameters that impact motion stability.

In our study, we investigated how different terrain conditions affect individual walking parameters. The study involved 15 participants walking through three different terrains: solid external surfaces, forest trails, and forest environments. We conducted a total of 150 trials, with 30 trials on solid surfaces, 60 trials on forest trails, and 60 trials in forest environments. The primary aim was to evaluate how these different terrains affect gait parameters and motion stability.

Key Findings

When walking on forest trails and forest environments compared to solid surfaces, participants demonstrated noticeable adaptations in gait:

Steps and Duration: Participants took more steps over a longer time frame in forest terrains. This suggests that the uneven and unpredictable nature of these terrains requires shorter and more frequent steps, likely as a strategy to maintain balance and stability.

Speed and Cadence: Both speed and cadence decreased significantly in forest environments, indicating a cautious approach to walking. This aligns with the need for greater control over movement to counteract the challenges posed by soft soils, loose debris, roots, and uneven surfaces.

Step Width and Foot Strike: Step width increased, and the duration of foot-ground contact was prolonged (as seen in increased foot strike percentages for both heel and toe contact). These adaptations likely reflect efforts to widen the base of support and ensure more stable footing, reducing the likelihood of slipping or tripping.

Walking on unstable surfaces, such as forest trails and environments, introduces significant variability in gait parameters. Research has shown that walking on uneven terrains like dirt, gravel, grass, and woodchips significantly increases energy expenditure and affects gait parameters such as stride variability and virtual foot clearance. These changes are indicative of the body's natural response to maintain stability and prevent falls.

Unstable surfaces require greater adjustments in gait to accommodate the irregularities of the terrain. For instance, walking on sand requires different ground reaction forces and joint torque profiles compared to solid ground, highlighting the adaptive strategies employed by humans to navigate yielding terrains.

The analysis of the kinematics of movement in individual terrains shows that the increasing difficulty of the terrain from Solid surface to Forest trails to Forest environment leads to the gradual destabilization of the body position and its elements, such as the walking parameters, center of gravity and the position of the pelvis. First of all, this is an increase in the tilt and extent of the deflection and rotation of the pelvis, which is directly related to the position of the body, which is reduced only by the movement of the terrain and shifts in the direction.

These adaptations are crucial for maintaining balance and also support the initial idea that the danger of body instability when moving in difficult terrain can correlate with the amount of risk of slipping, tripping, or falling.

Adaptive locomotion on uneven terrains often involves both feedforward planning and body feedback. Feedforward planning allows the body to anticipate changes in the terrain and adjust gait patterns accordingly, while sensor feedback provides real-time information about the terrain, enabling immediate adjustments to maintain stability.

Concurrently, body feedback provides real-time information about the terrain, allowing for immediate responses to unexpected variations in surface characteristics, such as roots, wood parts or uneven footing. Together, these mechanisms support the dynamic adaptations necessary for stable locomotion across diverse environments.

Several case studies highlight the biomechanical and physiological strategies employed during terrain-specific adaptations. There is an study explored the differences in walking on sand compared to solid ground [

35]. The findings revealed that walking on sand demands greater energy expenditure and altered joint torque profiles. Participants adapted to the yielding surface by increasing their step width and foot contact time, which improved lateral stability and reduced the risk of falls.

Similar examination was linked to the navigating rocky terrain. This study demonstrated the heightened demands on lower limb muscles and the importance of proprioceptive feedback in ensuring stable foot placement on uneven surfaces [

36]. Participants relied on both visual and tactile feedback to dynamically adjust their gait and maintain stability while stepping on unpredictable rocky features.

In the comparative gait analysis on urban pavements versus natural terrains, such as grass and gravel [

37] research found that walking on natural terrains required more frequent adjustments in gait parameters, including step length and cadence, to accommodate the irregular and often unstable surface. These findings reinforce the notion that natural terrains impose greater demands on the neuromuscular system compared to stable, even urban surfaces.

Our study underscores the importance of understanding how different terrains affect human locomotion and gait parameters. Participants exhibited increased step width and longer foot contact time, reflecting strategies aimed at enhancing lateral stability. These adjustments are also critical for reducing the likelihood of slips and falls on the uneven surfaces of forest trails. These insights can inform the design of safer walking standards and the development of interventions to reduce the risk of slips, trips, and falls.

The insights gained from studies and our findings underscore the importance of understanding how varying terrains influence human locomotion and gait parameters. Such knowledge is essential for designing safer walking environments and developing targeted interventions to minimize the risks of slips, trips, and falls. Our future research should continue to explore the biomechanical and physiological adaptations required for walking on various terrains to further enhance our understanding of human locomotion, ultimately contributing to extending an understanding of human locomotion and its implications for safety and mobility.

Maintaining stability on uneven terrains involves continuous adjustments to the body's center of mass (CoM). The CoM is a critical factor in balance and stability, and its position and movement are constantly regulated to prevent falls. On uneven surfaces, the CoM shifts more frequently and requires greater control to maintain balance.

Postural control strategies, such as the ankle and hip strategies, are employed to manage these shifts. The ankle strategy involves small adjustments at the ankle joint to maintain balance, while the hip strategy involves larger movements at the hip to counteract more significant perturbations. These strategies are essential for maintaining stability on uneven terrains.

The study revealed significant disruptions to the center of mass (COM) position and pelvic movement symmetry on forest trails and forest environments. These disruptions likely result from the need to constantly adjust body posture to accommodate the uneven terrain. Key observations include:

Pelvic Movement: Greater asymmetry in pelvic motion was observed in forestry environments, which is a biomechanical response to terrain irregularities. Such asymmetry helps redistribute body weight dynamically to avoid instability.

COM Adjustments: The irregular positioning of the COM is indicative of the body’s ongoing efforts to regain dynamic stability. These adjustments are more pronounced in terrains with loose soil and roots, where the risks of losing balance are heightened.

Humans employ various strategies to adapt to different terrains. These strategies can be categorized into behavioral, acclimatory, and developmental adjustments:

Behavioral Adjustments: These are immediate responses to environmental stressors, such as adjusting gait patterns or using assistive devices like walking sticks to enhance stability.

Acclimatory Adjustments: These are temporary physiological changes that occur in response to prolonged exposure to a particular terrain. For example, increased muscle strength and endurance in the lower limbs can improve stability on uneven surfaces.

Developmental Adjustments: These are long-term changes that occur over an individual's lifetime, such as improved proprioception and balance through regular exposure to varied terrains.

The uneven surfaces in forest environments, such as roots, rocks, and loose soil, significantly increase the risk of slips, trips, and falls. These terrains introduce external perturbations that challenge the body's ability to maintain stability. Key parameters that may contribute to fall risks include:

Step Variability: The increased variability in step width and length in forestry terrains reflects the body’s difficulty in maintaining consistent locomotion patterns, a key indicator of instability.

Foot Strike Proportions: Higher ground contact times suggest that participants are compensating for reduced friction and uneven footing. However, prolonged contact may also increase the chances of missteps or slips on loose surfaces.

Pelvic Symmetry Disruptions: Greater asymmetry in pelvic motion reduces the efficiency of recovery mechanisms following a perturbation, increasing fall risks.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a detailed examination of how human locomotion adapts to different terrain types, namely solid surfaces, forest trails, and forest environments. By analyzing gait parameters, stability, and movement patterns across 150 trials involving 15 participants, we have gained valuable insights into the biomechanical and physiological mechanisms that underpin terrain-specific adaptations. These findings provide a foundation for understanding the factors influencing stability, identifying root causes of slips, trips, and falls, and developing strategies to mitigate these risks in diverse environments.

As terrain complexity increases, participants exhibit significant adjustments in gait patterns to maintain balance and reduce the likelihood of falls. On solid surfaces, participants demonstrated stable and efficient locomotion, characterized by consistent speed, cadence, and reliance on heel strikes. However, forest trails and forest environments posed greater challenges, requiring participants to employ a range of adaptive strategies, including shorter steps, increased step width, and longer foot-ground contact times. These biomechanical changes highlight the body’s ability to prioritize stability and safety in response to environmental demands.

Walking on forest trails, participants took more steps with a moderate increase in cadence, reflecting the need for quicker, shorter steps to navigate irregular terrain. In contrast, forest environments elicited slower speeds, reduced cadence, and greater variability in step width and stride length, illustrating a more cautious approach to movement. These adaptations are indicative of the body’s response to minimize the risk of slips, trips, and falls by maintaining a wider base of support and enhancing lateral stability.

The study also underscores the role of the center of mass (CoM) in maintaining balance on uneven terrains. Forest trails and environments caused noticeable shifts in the CoM position and disrupted pelvic symmetry, highlighting the body’s dynamic adjustments to counteract terrain-induced instability. Greater asymmetry in pelvic motion and irregular CoM positioning were observed, reflecting the continuous effort required to stabilize posture and manage perturbations on complex surfaces. Such disruptions are critical indicators of the increased risk of falls, as they compromise the body’s ability to recover from instability.

The findings of this study contribute to understanding the root causes of slips, trips, and falls, particularly in challenging environments. Key parameters influencing fall risks include:

Step Variability: Increased variability in step width and stride length on forest trails and environments reflects the body’s struggle to maintain consistent locomotion patterns. This variability is a critical marker of instability, as irregular steps increase the likelihood of missteps or loss of balance.

Foot Contact Time: Prolonged foot-ground contact on uneven terrains is a compensatory strategy to enhance stability. However, this adaptation can also increase the risk of slips, particularly on loose or slippery surfaces, as longer contact times may reduce the responsiveness of corrective actions.

Pelvic Symmetry Disruptions: Greater asymmetry in pelvic motion compromises the efficiency of recovery mechanisms, making it harder for the body to regain balance after perturbations. This factor is particularly significant in terrains with frequent obstacles, such as roots or rocks.

The interplay between these parameters highlights the complexity of maintaining stability in uneven terrains and underscores the importance of terrain-specific adaptations to reduce the risk of falls. By identifying these root causes, targeted interventions can be developed to enhance gait stability and safety.

These mechanisms work in tandem to support the body's safe and efficient movement across complex surfaces.

For example, when navigating forest trails, in many cases participants rely on visual cues to identify potential obstacles and adjust their steps accordingly. Similarly, proprioceptive feedback from the lower limbs informs adjustments in foot placement and balance. These strategies are particularly evident in forest environments, where participants exhibited increased reliance on forefoot engagement and dynamic CoM adjustments to counteract the challenges posed by soft soils and roots, wood parts, or uneven footing.

This study provides a comprehensive understanding of the biomechanical and physiological adaptations required for walking on various terrains. However, further research is needed to expand on these findings and address the limitations of the current study. Specifically, future studies should:

Increase participants' Sample Size: Conduct studies with a larger and more diverse participant pool to ensure greater generalizability of the findings. Including participants of different ages, fitness levels, and mobility statuses will provide a more comprehensive understanding of terrain-specific adaptations.

Investigate Long-Term Adaptations: Examine how repeated exposure to uneven terrains influences gait mechanics and stability over time. Understanding acclimatory and developmental adjustments will shed light on the long-term benefits of training in challenging environments.

This analysis will provide valuable insights for designing safer walking environments in diverse forest terrain conditions.

In summary, human locomotion on uneven terrains is a dynamic process that requires continuous adjustments in gait parameters, stability, and movement patterns to navigate challenging environments safely. The study highlights the critical role of terrain-specific adaptations in maintaining balance, reducing fall risks, and ensuring efficient movement. By identifying the biomechanical and physiological mechanisms underpinning these adaptations, we can develop targeted interventions to enhance safety and mobility in complex environments.

Future research should build on these findings to explore the long-term impacts of terrain exposure, the effectiveness of assistive interventions, and the influence of environmental factors on gait stability. Through such efforts, we can deepen our understanding of human locomotion and promote safer mobility for individuals in diverse settings.

Author Contributions

Martin Röhrich: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Measurement and Gait data analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Eva Abramuszkinova Pavlikova: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Jakub Sacha: Data methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Mendel University in Brno, Czech Republic.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the person is anonymous in the interpretation of results. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Hsef s.r.o. company for the technical support and also PREMEDIS Foundation as well as the Czech Ergonomic Association for its support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- US National Safety Council, 2022 Occupational Safety Highlights. https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/work/work-overview/work-safety-introduction/.

- Team of Specialists on Best Practices in Forest Contracting, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2011, ISBN 978-92-5-106877-9.

- Tsioras, P.A.; C. Rottensteiner, C. ; Stampfer, K.; Tamparopoulos, A.E. Slip, trip and fall accidents in a large forest enterprise; CRC Press 2013, eBook ISBN 9780429227714.

- Jankovský M, Allman M, Allmanová Z. What are the occupational risks in forestry? Results of a long-term study in Slovakia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4931. [CrossRef]

- Allman M.; Dudakova Z.; and Jankovsky, M. Occupational accidents in Slovak Military Forests and Estates: incidence, timing, and trends over 10 years. Front. 2024 Public Health 12:1369948. [CrossRef]

- Okuda, M.; Kawamoto, Y.; Tado, H.; Fujita, Y.; Inomata, Y. Energy Expenditure Estimation for Forestry Workers Moving on Flat and Inclined Ground. Forests 2023, 14, 1038. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.Y.; Choe, S.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Koo, K.H. The trend of occupational injuries in Korea from 2001 to 2010. Saf. Health Work 2013, 4, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Landekić, M.; Bačić, M.; Bakarić, M.; Šporčić, M.; Pandur, Z. Working Posture and the Center of Mass Assessment While Starting a Chainsaw: A Case Study among Forestry Workers in Croatia. Forests 2023, 14, 395. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins KA, Clark DJ, Balasubramanian CK, Fox EJ. Walking on uneven terrain in healthy adults and the implications for people after stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;41(4):765-774. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thies, S.B; Richardson, J.K.; Ashton-Miller, J. A. Effects of surface irregularity and lighting on step variability during gait: A study in healthy young and older women, Gait & Posture, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2005, ISSN 0966-6362. [CrossRef]

- Kent, J. A.; Sommerfeld, J. H.; Mukherjee, M.; Takahashi, K. Z.; & Stergiou, N. Locomotor patterns change over time during walking on an uneven surface. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2019, 222, jeb202093. [CrossRef]

- Voloshina, A. S.; Kuo, A. D.; Daley, M. A.; & Ferris, D. P. Biomechanics and energetics of walking on uneven terrain. Journal of Experimental Biology 2013, 216(21), 3963–3970. [CrossRef]

- Gates, D. H.; Wilken, J. M.; Scott, S. J.; Sinitski, E. H.; & Dingwell, J. B. Kinematic strategies for walking across a destabilizing rock surface. Gait and Posture 2012., 35(1), 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Blair, S.; Lake, M. J.; Ding, R.; & Sterzing, T. Magnitude and variability of gait characteristics when walking on an irregular surface at different speeds. Human Movement Science 2018, 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, UQ.; Shahzaib, M.; Shakil, S.; Bhatti, F.A.; Saeed,M.A; Robust and adaptive terrain classification and gait event detection system, Heliyon, Volume 9, Issue 11, 2023, e21720, ISSN 2405-8440. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844023089284). [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Downey, RJ.; Salminen, JS.; Rojas, SA.; Richer, N.; Pliner, EM.; Hwang, J.; Cruz-Almeida, Y.; Manini, TM.; Hass, CJ.; Seidler, RD.; Clark, DJ.; Ferris, DP. Electrical Brain Activity during Human Walking with Parametric Variations in Terrain Unevenness and Walking Speed. 2023 Aug 2:2023.07.31.551289. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kowalsky, DB.; Rebula, JR.; Ojeda, LV.; Adamczyk, PG.; Kuo, AD. Human walking in the real world: Interactions between terrain type, gait parameters, and energy expenditure. PLoS ONE 16(1) 2021: e0228682. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Chen, X.; Yi, J. Human Walking Locomotion Data on Solid Ground and Sand, Mendeley Data, V2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Coppola, S.M., Dixon, P.C. et al. A database of human gait performance on irregular and uneven surfaces collected by wearable sensors. Sci Data 7, 219 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Donelan, JM.; Kram R.; Kuo, A.D. Mechanical work for step-to-step transitions is a major determinant of the metabolic cost of human walking. J Exp Biol. 2002; 205: 3717–27. [PubMed]

- Gates, D.H.; Wilken, J.M.; Scott, S.J.; Sinitski, E.H.; Dingwell, J.B. Kinematic strategies for walking across a destabilizing rock surface. Gait Posture. 2012; 35: 36–42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A,R,; Kuo, A.D. Energetic tradeoffs of foot-to-ground clearance during swing phase of walking. Columbus, OH; 2015.

- Kuo, A.D. Stabilization of lateral motion in passive dynamic walking. Int J Robot Res. 1999; 18: 917–930.

- Bauby, C.E.; Kuo, A.D. Active control of lateral balance in human walking. J Biomech. 2000; 33: 1433– 1440. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruijn S.M. ; van Dieën J. H.; Control of human gait stability through foot placement; J. R. Soc. Interface, 2018; [CrossRef]

- Holowka, NB.; Kraft, TS.; Wallace, IJ.; Gurven, M.; Venkataraman, VV. Forest terrains influence walking kinematics among indigenous Tsimane of the Bolivian Amazon. Evol Hum Sci. 2022 Apr 22;4:e19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brambilla, C.; Beltrame, G.; Marino, G.; Lanzani, V.; Gatti, R.; Portinaro, N.; Molinari Tosatti, L.; Scano, A. Biomechanical Analysis of Human Gait When Changing Velocity and Carried Loads: Simulation Study with OpenSim. Biology 2024, 13, 321. [CrossRef]

- Roggio, F.; Trovato, B.; Sortino, M. et al. Self-selected speed provides more accurate human gait kinematics and spatiotemporal parameters than overground simulated speed on a treadmill: a cross-sectional study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 16, 226 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kowalsky, DB.; Rebula, JR.; Ojeda, LV.; Adamczyk, PG.; Kuo, AD. Human walking in the real world: Interactions between terrain type, gait parameters, and energy expenditure. 2021, PLOS ONE 16(1): e0228682. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J..; Mayagoitia, R.; Smith, I. A portable system for collecting anatomical joint angles during stair ascent: a comparison with an optical tracking device. Dyn Med. 2009 Apr 23;8:3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- chepers, Martin & Giuberti, Matteo & Bellusci, G.. (2018). Xsens MVN: Consistent Tracking of Human Motion Using Inertial Sensing.; Xsens Technol. 1–8 (2018; [CrossRef]

- Negi, S., Sharma, S. and Sharma, N. (2021), "FSR and IMU sensors-based human gait phase detection and its correlation with EMG signal for different terrain walk", Sensor Review, Vol. 41 No. 3, pp. 235-245. [CrossRef]

- Xsens/ Movella company; Xsens MVN Gait Report: The use of inertial motion capture for Cloud based; Document MVN Gait report - Whitepaper, Revision A, 12 Jan 2021.

- Xsens/ Movella company; Xsens MVN Gait Report: Gait Report - How to interpret the data Document MVN Gait report; https://base.movella.com/s/article/Gait-Report-How-to-interpret-data?language=en_US.

- Adamczyk, P. G., & Kuo, A. D. (2021). Biomechanical comparison of human walking locomotion on solid ground and sand. Journal of Biomechanics. Link :.

- Fitzpatrick, L. E. (2021). Human Variation: An Adaptive Significance Approach. In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. Link : Adaptive Locomotion on Uneven Terrains. (2017). SpringerLink. Link : Postural Control. (2021). Physiopedia. Link :.

- Gates, D. H., Wilken, J. M., Scott, S. J., Sinitski, E. H., & Dingwell, J. B. (2012). Gait characteristics of individuals with transtibial amputations walking on a destabilizing rock surface. Gait & Posture. Link :.

- Marigold, D. S., & Patla, A. E. (2008). Gait adaptations to perturbations in the travel path: strategies for maintaining or regaining locomotor control. Journal of Neurophysiology. Link.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).