1. Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is one of the most common malignant primary brain tumors and, despite a numerous efforts to find an effective therapy, it is still characterized by a very poor prognosis [

1,

2]. Among others, one feature that makes GBM difficult to defeat is its ability to migrate and infiltrate into the surrounding brain parenchyma and these properties are strongly related to a continuous dynamic reorganization of the polymers making up the cytoskeleton of glioblastoma cells [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. At the same time, many of the changes in cell properties during tumor progression induce significant alterations in the architecture and mechanical properties of both the tumor cells and the surrounding host tissue. The strategies against this type of tumor, like in other cases, are complicated by the potential go-or-grow behaviour of the involved malignant cells. This mechanism refers to a hypothesis, derived mainly from

in-vitro experiments, according to which the infiltrative and proliferative states of cancer cells are mutually exclusive phenotypes [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Moreover, a problem of glioma cells, which is also typical of other tumor cells, is their ability to adapt to changing environmental situations by adjusting for example the migration strategy to a variation of the physical environment [

16,

17,

18]. Although the available standard therapy for GBM has evolved into multimodality approaches, comprising temozolomide and the antiangiogenic monoclonal recombinant antibody bevacizumab, corticosteroids, and immunotherapy, unfortunately, the improvements in patients’ survival have been only modest [

19,

20]. This has led to an important effort to identify new molecular targets in GBM tumors, specifically focusing on pathways involved in motility, applied traction force, and proliferative properties of the associated cells [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. It is known that cellular and matrix mechanics are involved in many biological functions in eukaryotic cells, such as migration, differentiation, morphogenesis, and proliferation [

27,

28,

29]. The cytoskeleton and the associated proteins are responsible both for transducing external mechanical stimuli into biochemical processes and for the application of stresses to the external matrix. This sort of mechanical reciprocity is strictly dependent on the activity of cytoskeleton-associated motor proteins and the cell/matrix adhesion molecules and it is altered in the case of developing and migrating tumors [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Specific Microtubule-Associated Proteins (MAPs), especially those related to the highly dynamic behaviour of microtubules, could represent a good focus to simultaneously act on the invasion and proliferation activity of GBM cells. From this point of view, compounds that selectively target MAPs inducing alteration of microtubules dynamics but preventing their depolymerization could more selectively target cancer cells, in which the dynamic activity is strongly enhanced [

35,

36].

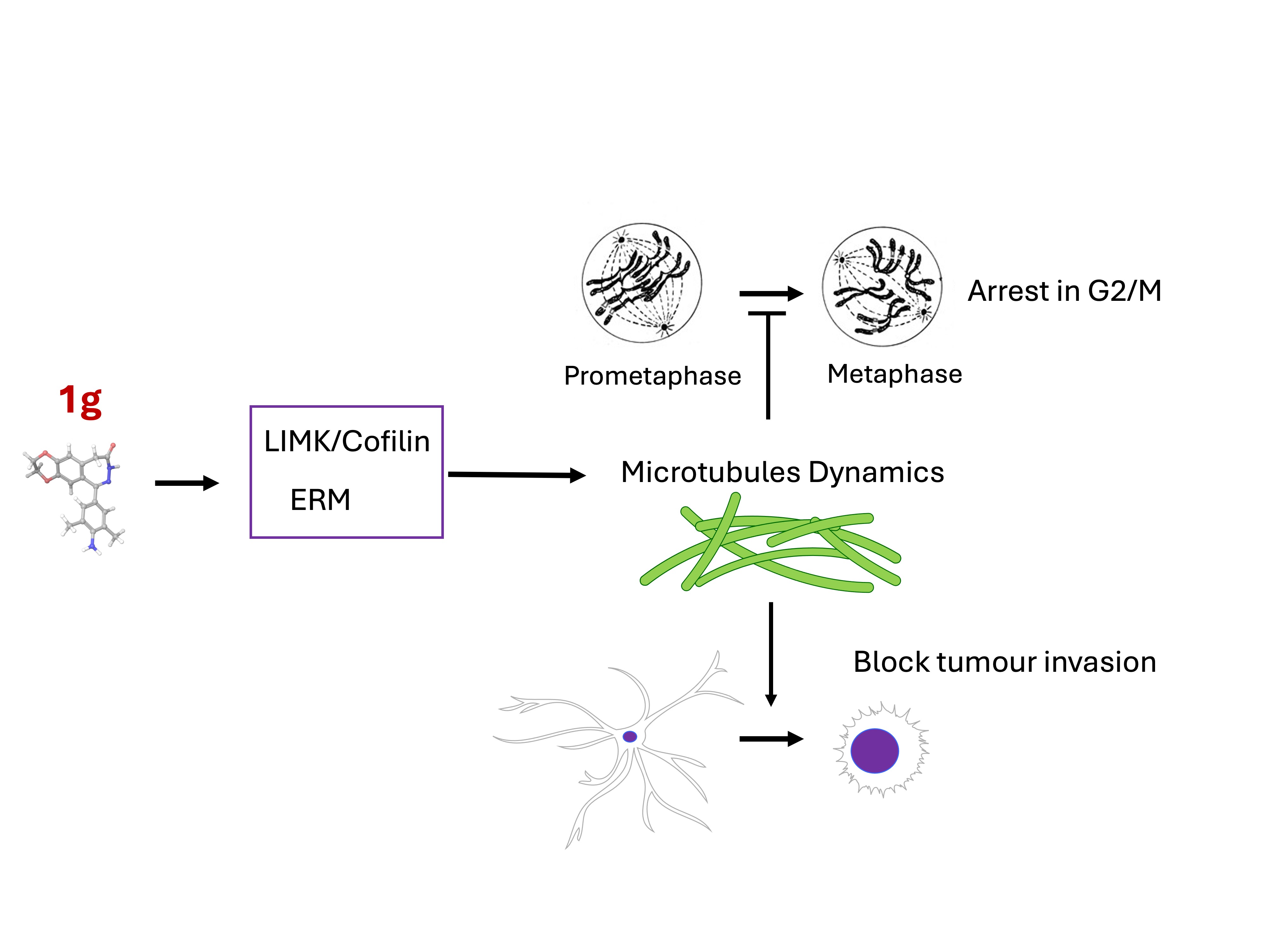

We recently demonstrated the ability of a new 2-benzodiazepine-3-one derivative (hereafter referred to as 1g) to arrest the cell cycle progression in human leukemia Jurkat T cells and HeLa cells by altering mitotic spindle formation during mitosis with the formation of multipolar spindles without centrosome amplification and by affecting microtubule dynamics [

37,

38]. In the case of HeLa cells, the molecule does not appear to affect microtubule organization in interphase and it does not seem to interact directly with microtubules but rather through some MAP. This behavior opens up the possibility of a specificity of the interaction of this molecule for different cell types, due to the presence of different MAPs in different cell lines. Since the new molecule is supposed to be able to cross the blood-brain barrier [

39], it could represent an interesting candidate in the fight against brain tumors. In this work, we studied how 1g interferes with the replication, migration, and mechanical properties of the U87MG cell line. We considered different cell environments to study the effect of 1g, starting from multicellular spheroids, and then moving to single-cell migration on substrates of different stiffness. We found that 1g is able to reduce the expansion of cell spheroids in Matrigel

® matrices and strongly affects (by decreasing) collective contractility. Exploiting 2D systems to deepen our understanding of the biochemical action mechanism of 1g, we found that, in the short term, this molecule affects cell morphology in the short term by removing cell polarity in a cell-specific manner on U87MG cells and not on fibroblast (NIH

Balb-3T3) cells. The polarity loss is then associated to a strong decrease in the migration ability in terms of cell directionality and explored area. In a long-term effect, 1g strongly perturbs the mitotic process in a less cell-specific way by producing a multipolar spindle with aberrant mitosis. In interphase, after the initial rounding effect, cells flatten on the surface without polarizing and cells undergoing mitosis, after prolonged attempts to perform division, perform a mitotic slippage and flatten on the surface We also focused on the mechanobiology of U87MG cells on substrates of different stiffness analyzing the specific effect of the 1g molecule in these different situations. At the same time, we characterized the mechanical phenotype of the cells exposed to 1g both by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) at the single cell level and by the Micropipette Aspiration Technique (MAT) for cell aggregates. We found an increased stiffness for single cells exposed to 1g for 24 h (cells not in mitosis and with a round shape, i.e., cells in interphase probably after an attempt of mitosis) and a decreased stiffness and surface tension for spheroids, where the mechanical properties strongly depend on the cell/cell interactions and on the extracellular matrix. We suggest that 1g, at the tested concentrations, acts by altering microtubule dynamics without inducing depolymerization. In terms of cellular morphology and migration capacity, this molecule is therefore more effective in the case of cells that rely significantly on microtubules for these functions, such as glioma cells. We also found pieces of evidence suggesting an interaction of the molecule at issue with the microtubule/plasma membrane attachment sites causing both a loss of polarity and an aberrant mitotic fuse formation due to the disorganization of the astral microtubules.

3. Discussion

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary tumor of the central nervous system. Its very poor prognosis is mainly related to its extremely high invasive potential, which allows its cells to migrate along vessels and through the white matter in the brain, probably exploiting specific mechanisms for different environments. Therefore it is urgent to develop new compounds for GBM treatment that can be used alone or in combination with existing drugs to enhance efficacy and minimize side effects. Extensive research has focused on the cytoskeletal features of tumor cells to evaluate the dynamics of cell motility and invasion. Considering this, we conducted a detailed study on how a new benzodiazepine derivative (1g) affects cellular mechanics, proliferation, invasion and migration of the glioblastoma cell line U87MG.

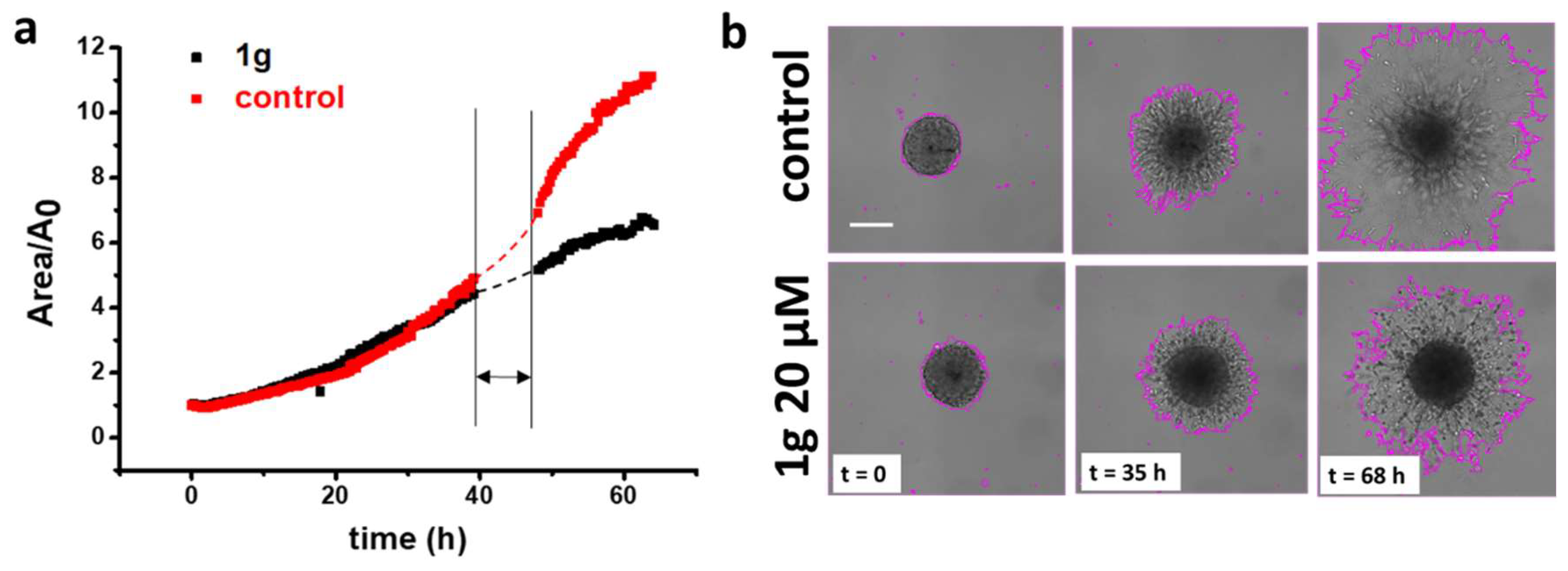

We conducted invasion experiments by embedding spheroids in a Matrigel environment. Spheroid expansion experiments did not allow us to fully distinguish between the contributions of cell invasion and cell duplication. This distinction is particularly important for U87MG cells exposed to 1g, as biochemical and optical microscopy analyses of 2D cell populations indicate that 1g induces an arrest of U87MG cells in the G2/M phase, functioning similarly to a cytostatic drug. However, in our case, we can assume that the most significant factor influencing the observed expansion of U87MG spheroids is cell diffusion, which relates to random migration along with a form of directed motility away from the core region. This directed motility is likely attributable to a gradient in nutrients [

90], although the exact process is not completely understood. This assumption is supported by taking into account that only a limited time (65 hours) is considered, suggesting that proliferation is not the primary factor governing the expansion behavior.

To better distinguish between the processes of proliferation and invasion, it would be useful to extract quantitative information from the process as illustrated in

Figure 1. The growth of spheroids has been described using various mathematical models, with the Gompertz [

90,

91] model being the most widely employed. This model consists of several phases, including a latent period, an optimal growth phase, and a plateau phase. The mathematical representation of spheroid growth is characterized by a sigmoidal behavior in the radius as a function of time. The initial latent period corresponds to the formation of a compact cell aggregate, followed by an exponential growth phase. This is followed by a linear growth phase, during which the rim of proliferating cells remains constant, and, finally, a saturation phase is reached where growth is balanced by necrosis. Although the growth trends we observed align with this model, it is essential to consider the invasive nature of glioma spheroids when they are embedded in a 3D gel. For smaller spheroids, such as those examined in this study, it is crucial to distinguish the two different regions: the core and the rim. These regions exhibit different behaviors regarding proliferation and dispersion. The core region of spheroids is typically characterized by rapidly proliferating cells with low diffusion properties. In contrast, the rim consists of cells that exhibit higher diffusion behavior but lower replicative properties, in accordance with the go-or-grow hypothesis. Mathematical models have been developed to simultaneously describe cell duplication and invasion in spheroids. These models commonly utilize various parameters to characterize the invasion and growth of spheroids, including a diffusion constant (D), a maximum cell density to account for growth inhibition at very high densities, a coefficient representing the number of cells moving away from the core’s boundary per unit time, a factor for cell duplication time, and a directed velocity —likely due to gradients of nutrients or signals from metabolic byproducts of the spheroid cells. Using these models could help evaluate whether exposure to 1g, for example, favors an expansion, where diffusion dominates over directed motion. However, fitting these models to experimental data requires a clear distinction between the core and rim of the spheroids. In our case, we could not clearly identify this separation, particularly in control spheroids, where the transition between the two regions is largely faded. We can conclude that, in the case of GBM spheroids exposed to 1g, the central core region remains stable over time. In contrast, cells in the rim diffuse much less than those in the control experiment. This may indicate that the drug is unable to penetrate completely into the core of the spheroid; therefore, cells in the inner region continue to duplicate, while cells in the rim neither duplicate nor diffuse significantly. Moreover, the type of migration is different in the control case compared to the case with 1g, being mainly a collective and mesenchymal migration in the former case and an amoeboid and individual migration in the latter case.

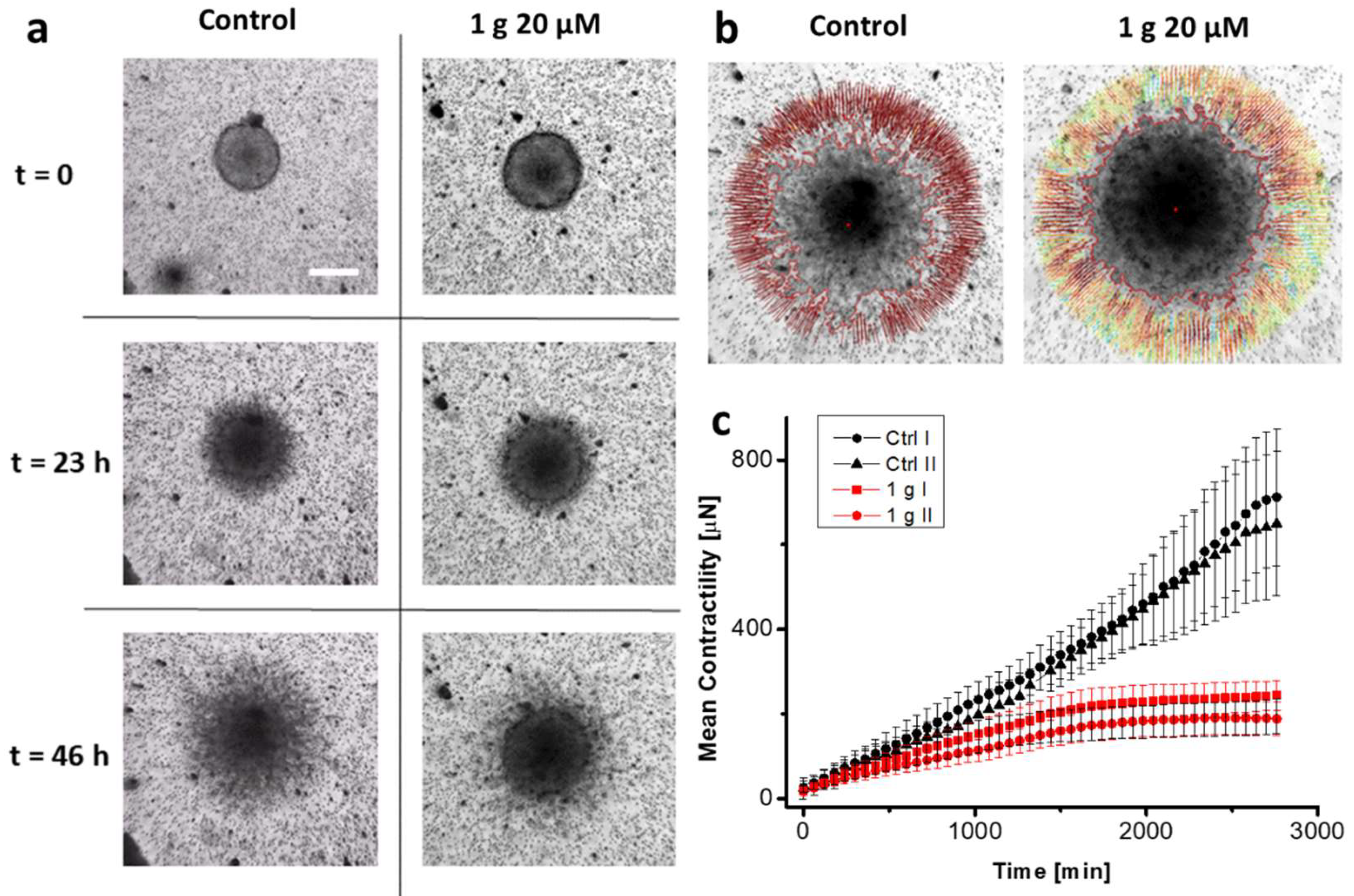

Traction force microscopy experiments on U87MG spheroids revealed that exposure to 1g resulted in decreased contractility, which may contribute to a reduced invasion ability of cells within the 3D Matrigel matrix. Strong contractility is vital as it helps align fibers around the spheroid, allowing cells to exploit these fibers for directed migration into areas distant from the spheroid. Although 1g exposure decreased the surface tension of cell aggregates (see

Figure 3), the individual behavior of cells in a 3D environment under 1g significantly diminished their contractility. This reduction hampered their interaction with extracellular fibers and their overall invasion potential. In contrast, the collective behavior of untreated U87MG cells led to strong contraction of the extracellular matrix, which is positively correlated with their invasion ability [

44]. Additionally, we assessed the mechanical properties of single cells using atomic force microscopy (AFM), observing an increase in cell rigidity under 1g conditions. In 2D culture analyses, 1g exposure considerably affected cell morphology, leading to a rapid loss of polarity (see

Figure 5). In this case, it is important to consider that an increased contraction (or prestress) in cells in 2D typically leads to an increased rigidity of the cells as probed by AFM.

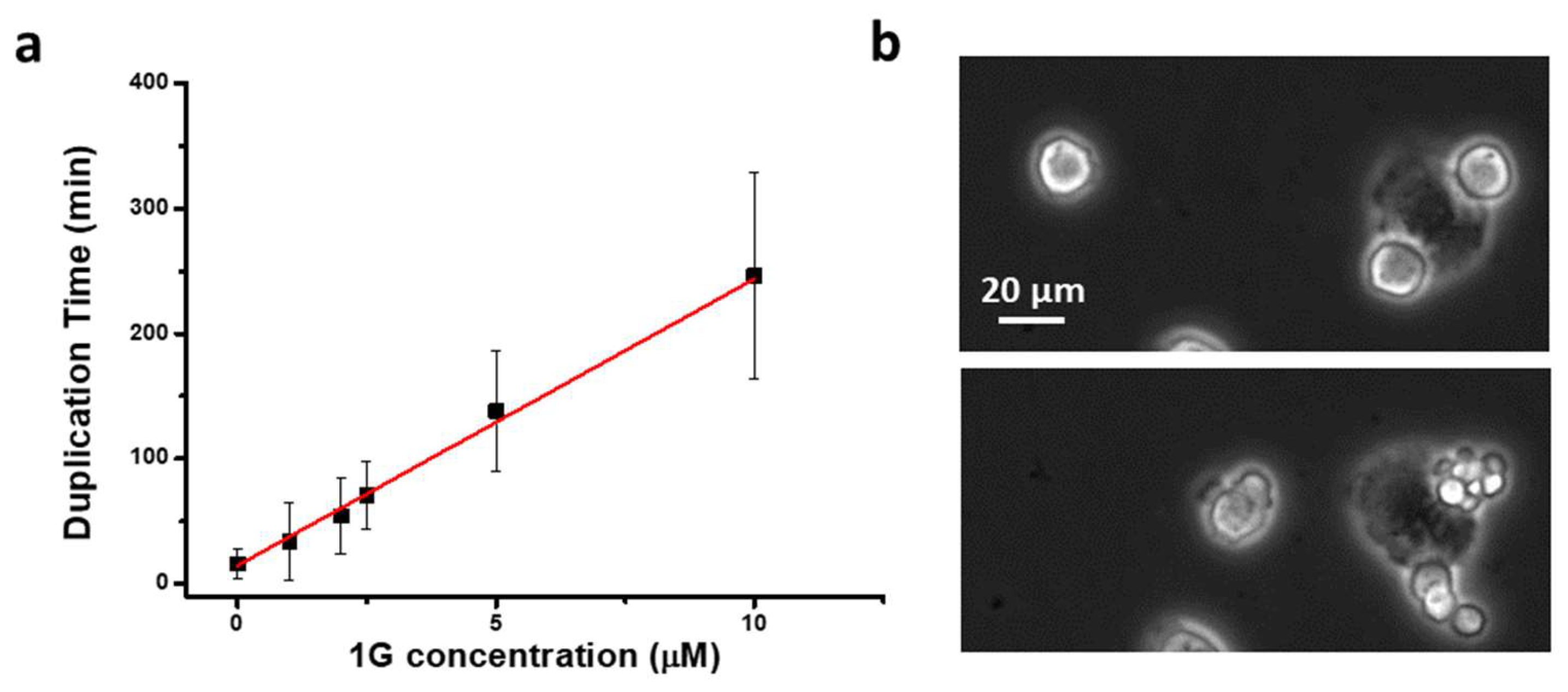

We also noted a clear correlation between 1g concentration and the increased duration of cell mitosis (see

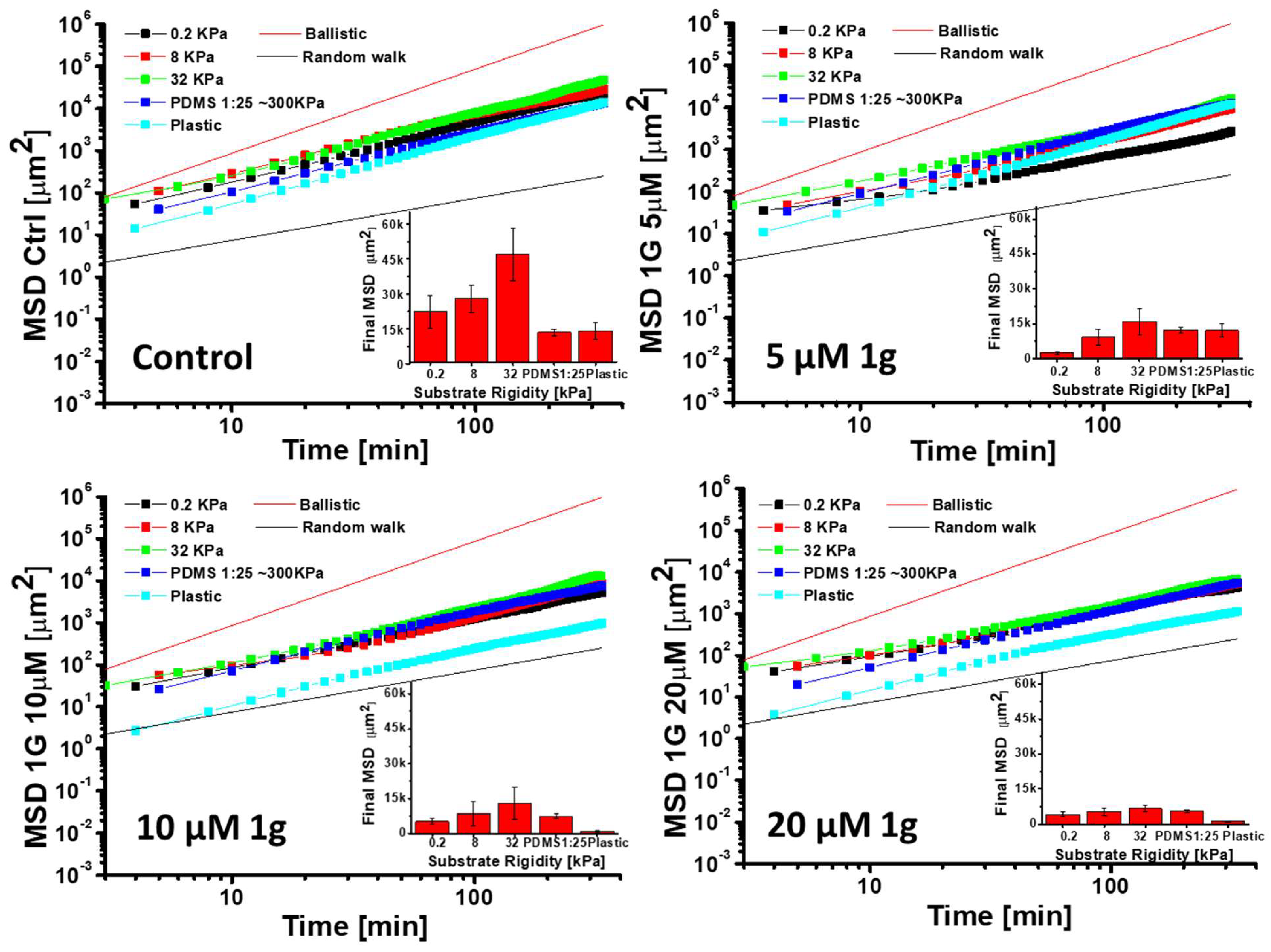

Figure 7). Interestingly, the loss of polarity appeared to be cell-type dependent; for instance, the morphology of NIH3T3 cells at the same 1g concentrations was unaffected. This loss of polarity correlated with a significant reduction in the migration area explored by U87MG cells in 2D cultures. We further investigated cell migration on substrates with varying rigidities. The mean square displacement (MSD) parameter indicated a biphasic behavior for U87MG cells in response to substrate rigidity, consistent with observations in other cell lines [

69,

92,

93,

94]. This behavior likely reflects a balance between cell adhesion to the substrate and the dynamics of actin polymerization and traction force generation [

95,

96]

. On softer substrates, cells exhibited lower adhesion areas, producing a weaker attachment of focal adhesion complexes at the leading edge and inefficient forward movement. Conversely, on very stiff substrates, strong adhesion complexes development complicated the release of the cell’s rear portion during migration. Therefore, an intermediate substrate stiffness might provide an optimal balance, enhancing cell migration

. A quantitative model based on the motor-clutch mechanism [

69], originally designed to explain traction force exerted by cells, can also be applied to the migration process. This model involves various modules oriented differently, each one connected to the central nuclear region, and analyzed according to the molecular clutch theory. These modules generate traction forces that facilitate effective cell migration [

97]. Within each module, myosin contractility is partially transmitted to the adhesion complexes, which link cytoskeletal elements to the substrate, establishing a retrograde flow of actin. The binding and unbinding rate constants, alongside the rate of force application on the substrate, are fine-tuned to achieve an optimal intermediate substrate rigidity, ensuring that the rate of force application neither hinders the formation of sufficient integrin/substrate attachment points before disengagement nor allows premature detachment of adhesion complexes before adequate force is exerted on the substrate.

Whereas the motor-clutch mechanism primarily focuses on the roles of cytoskeletal actin polymers, adhesion complexes and motor proteins, microtubules generally do not play a direct role. However, it has been shown that drugs affecting microtubule dynamics can also indirectly influence actin stress fibers, traction force, and cell migration [

70,

80,

98,

99]. Specifically, drugs that disrupt microtubule attachment to integrin adhesion sites can activate Rho GTPase pathways, thereby strengthening actin stress fibers [

100]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that drugs interacting with microtubules can alter the substrate rigidity value corresponding to the maximum explored area in cell migration, but, in our case we didn’t see any appreciable variation of this value, probably because of a reduced resolution of the values of substrate stiffness that we considered. In some cases, research has shown that drugs interacting with microtubules and slowing their dynamics can reduce the sensitivity of cell migration to the stiffness of the substrate [

101]. Our data suggest a similar trend: higher concentrations of 1g result in minimal differences in the area explored across various substrate rigidities. According to the molecular clutch model used for simulating cell migration, several critical parameters can influence cell migration behavior and its dependence on substrate rigidity. These include the number of molecular motors, the number of molecular clutches (particularly the ratio between the two), the actin polymerization rate (which guides pseudopodia formation and the capping of actin filaments), and the rate of pseudopodia formation. Previous studies have demonstrated that when drugs are used at concentrations that slow microtubule dynamics, there is a decrease in the actin polymerization rate and an increase in the pseudopodia nucleation rate. Both of these changes can lead to a reduction in the area explored by cells and a decreased sensitivity to the substrate’s Young’s modulus [

102]. In our observations, particularly from the time-lapse videos of U87MG cells exposed to 1g (see Movie S16), we believe that the increased nucleation rate of pseudopodia is the most likely explanation for our findings. Each time the cell attempts to extend a pseudopodium, it fails to stabilize this extension, causing the cell to retract and initiate a new extension in a different direction.

Previous investigations into the effects of 1g have shown that it can influence microtubule dynamics, likely through the action of certain Microtubule-Associated Proteins (MAPs) [

37]. This mechanism suggests that 1g may have specific effects on different cell types, depending on the presence of various MAPs. In HeLa cells, the impact of 1g on the cytoskeletal structure during interphase was minimal, with its primary effects observed during the mitotic phase. Conversely, in U87MG cells, the loss of cell polarity induced by 1g indicates that it may also affect microtubule dynamics during interphase, which contrasts with the behavior observed in HeLa cells. We can hypothesize that 1g, by acting on microtubule dynamics, inhibits the stabilization of process after they are initiated. As a result, migrating cells may undergo rapid changes in their direction of motion, appearing similar to Brownian particles, even over short time intervals. It is also noteworthy to compare the observations made with 1g to the effects of taxanes on endothelial cells. In that context, a decrease in cell migration was noted, affecting both speed and directionality, at concentrations lower than those required to impair cell duplication [

100]. The effect of taxanes was associated with an alteration in microtubule dynamics (frequency of transition from the growth to the shortening phase), resulting, at higher concentrations, in a strong decrease in shortening rate and length, and a decrease in the number of cell adhesion complexes, accompanied by an enlargement of the remaining ones. Moreover, paxillin was observed to form enlarged circular structures similar to those showed in

Figure 13b.

Taxol has been shown to reduce the presence of EB1-decorated plus ends of microtubules, which limits the delivery of the molecular components necessary for the protrusive activity of podosomes and their stabilization. This, in turn, affects cell polarization

102. The stabilization of focal adhesion complexes is typically associated with the activity of the actin cytoskeleton, as actin filaments strongly interact with integrins, which are central to adhesion complexes. This stabilization is correlated with the formation of contractile bundles of actin and myosin motors, known as stress fibers. However, microtubules also target focal adhesion sites and interact with the cell cortex [

103]. Microtubules dock at the plasma membrane through cortical microtubule stabilizing complexes (CMSCs) [

101]. This association not only stabilizes microtubules against depolymerization but also promotes cell polarization. Consequently, there is a strong correlation between microtubule dynamics and the actin cytoskeleton, which can influence the formation or disassembly of adhesion complexes and cell protrusions. It is essential to consider that microtubules serve as pathways for the transport of molecules within the cell. Inhibitory signals are transported via microtubules, and if their dynamics are reduced, these signals may persist longer than necessary in the region where cell polarization begins, preventing its stabilization. This process could be the reason for the increase in the rate of nucleation of processes but without their stabilization, as we reported on the basis of time-lapse imaging.

Drugs that target microtubule dynamics can have different effects depending on their concentration. At high concentrations, they may cause depolymerization or stabilization of the microtubules; however, at low concentrations, these drugs typically converge in reduced activity. In this context, it has been found that both paclitaxel and vinblastine, which are among the most widespread and already approved drugs for the treatment of cancer, are able to stabilize the dynamics of microtubules, even if they act differently by promoting, at higher concentrations, stabilization or depolymerization, respectively [

104].

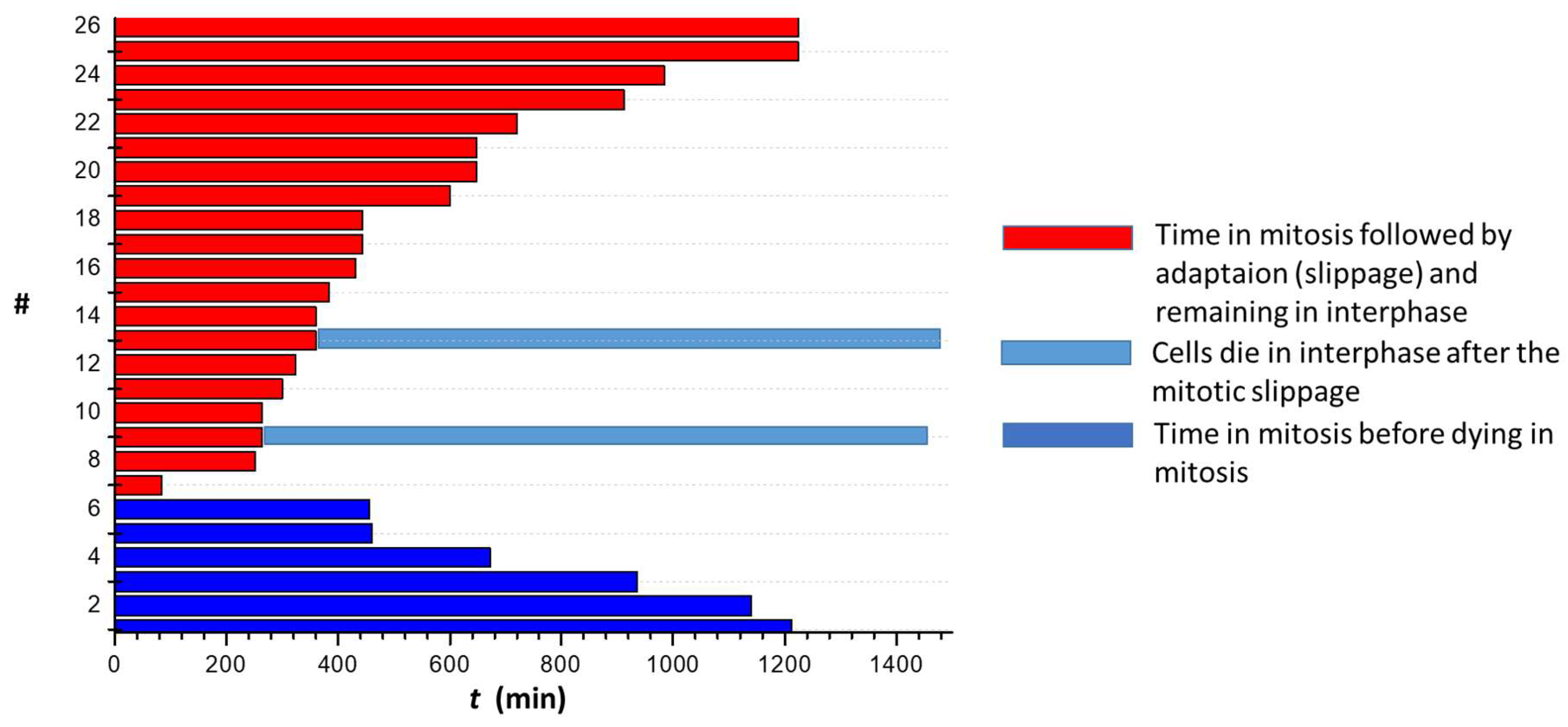

While many microtubule-targeting drugs are considered for their antimitotic effects, it has been reported that inducing complete antimitotic effects, which pushes cells toward apoptosis by attempting to override the spindle mitotic checkpoint, is not always necessary for these drugs to be effective. For example, paclitaxel has been shown to promote the formation of multipolar spindles at clinically relevant concentrations, leading to a majority of cells experiencing an abnormal exit from mitosis, a process known as mitotic slippage. This process results in gradual cell death during interphase [

60]. One reason for this behavior may be that cells have access to more apoptotic pathways during the interphase compared to the mitotic phase, prompting them to undergo mitotic slippage to better engage these pathways. It has been hypothesized that paclitaxel targets the mechanisms responsible for correcting the frequent occurrence of multipolar spindles in cancer cells, particularly in cases of centrosome amplification [

105]. Even in the case of 1g, we found that cells blocked in mitosis preferentially undergo a slippage to interphase, and they are typically killed after one attempt to perform mitosis. In general, given the increase of microtubule dynamics during mitosis, by altering microtubule dynamics, drugs can induce cells to form multipolar spindles even in the absence of centrosome amplification, consequently leading to a division with multipolar spindles [

37]. However, microtubule-targeting drugs are also able to affect cell behavior during the interphase stage[

62,

106]. This impairment may occur because microtubules function as highways for transporting various signaling molecules, such as proteins, vesicles, and mitochondria. They play a crucial role in both inhibiting and promoting specific signaling pathways and interact with surface proteins on the cell. Several proteins play significant roles in the complex mechanism of cell migration, particularly within focal adhesion complexes. These complexes are structures formed at the ends of stress fibers, anchoring cells to the substrate and ensuring both stability and directionality during the cell migration process. There are two competing effects related to the strength of focal adhesions in cellular motion: on one hand, the formation of larger structures is associated with stronger adhesion to the substrate, leading to reduced invasiveness. On the other hand, weak complexes are unable to generate the traction force necessary for cell migration [

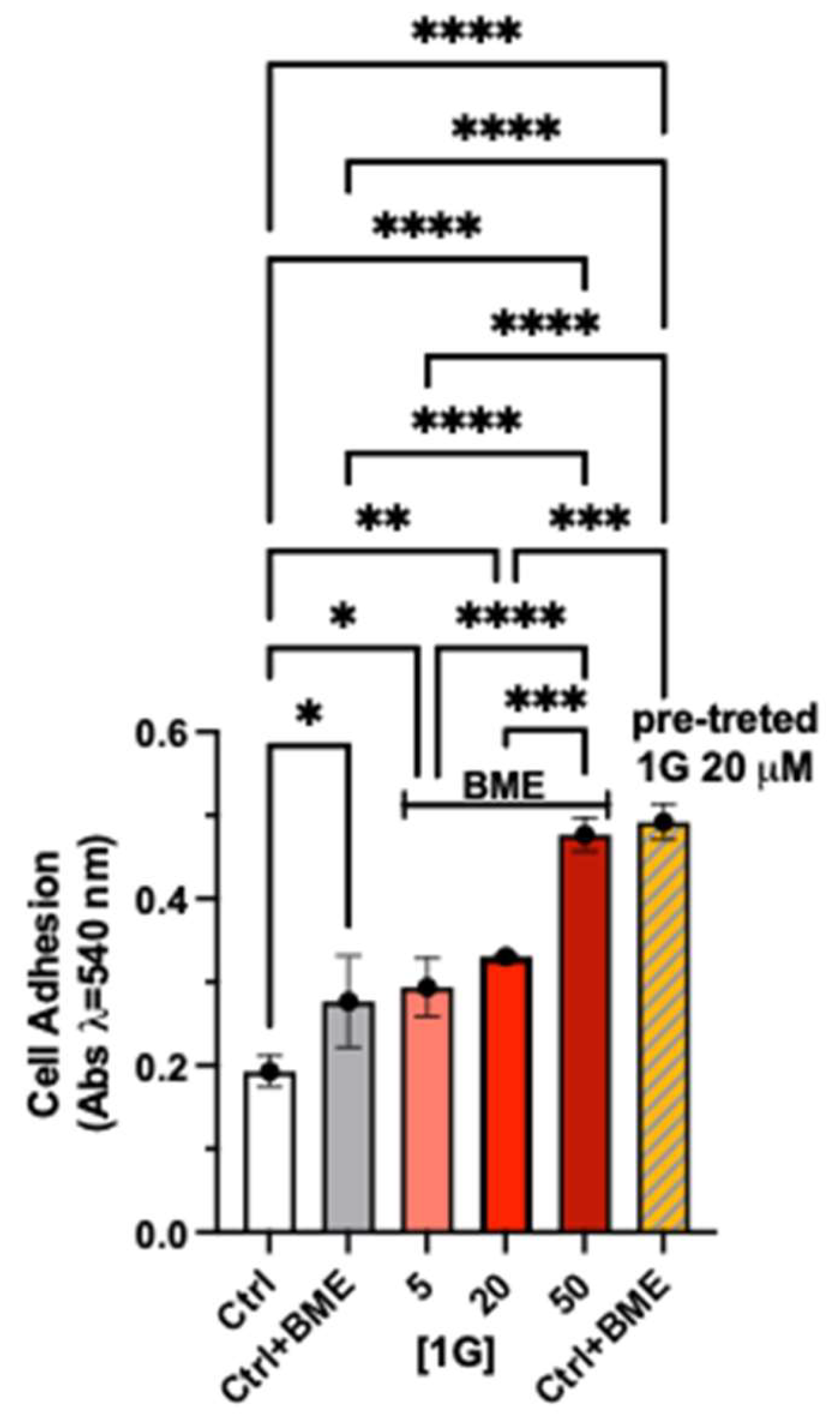

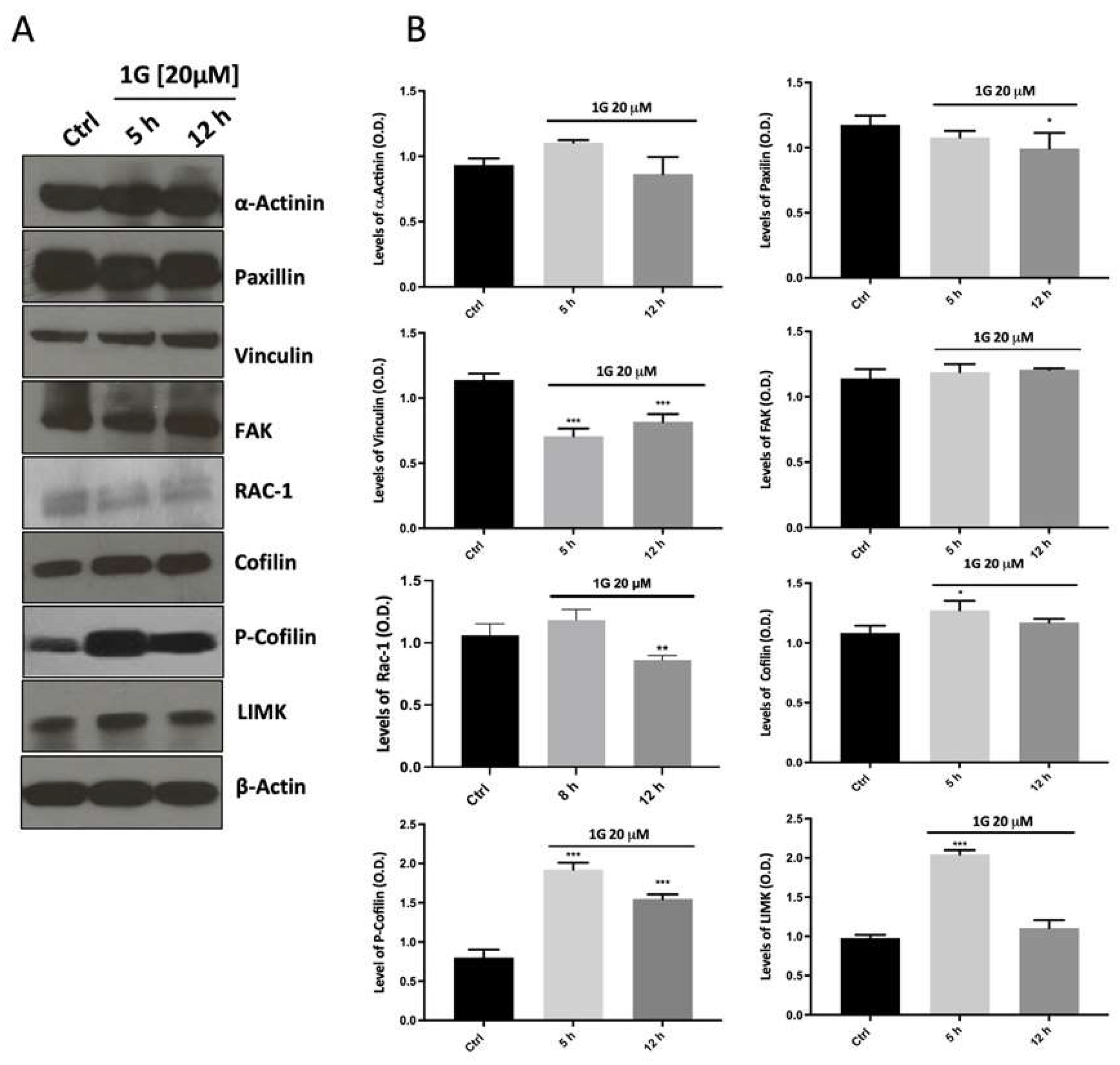

107]. In our study, we examined the expression of certain proteins present in focal adhesions through immunoblotting. Our results indicated that the expression of the structural protein α-actinin did not exhibit significant changes in the presence of 1g, with only a minimal decrease observed after 24 hours of treatment. In contrast, the concentration of vinculin, a protein involved in mechanical force transduction, showed a significant reduction shortly after the initiation of 1g treatment. This finding agrees with earlier data indicating a loss of polarization within a short timeframe. Conversely, paxillin did not show any changes in protein expression over the 24-hour period compared to the control. Additionally, analysis of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) protein expression revealed no differences at the tested time points. This suggests the possibility of an alternative pathway involved in pro-adhesion activity illustrated in

Figure 6 and mediated by 1g . Notably, FAK does not interact directly with integrins but rather through adaptor molecules such as paxillin or α-actinin [

108]. Previous research established that 1g can arrest the cell cycle in the G2 phase, significantly increasing p21 protein expression [

57]. p21 is known to activate LIM kinase (LIMK), a family of actin-binding proteins that stabilize actin filaments by activating cofilin. Our findings showed that while Rac-1 expression is inhibited by 1g, LIMK levels were increased, which in turn deactivates cofilin through phosphorylation, an increase also observed after exposure to 1g. Thus, we can speculate that LIMK/cofilin activation may be triggered by p21. Moreover, since cofilin interacts directly with integrins through the c-Src complex [

109], and is crucial for cell adhesion, the rise in the phosphorylated form of cofilin could partially account for the increase in cell adhesion and the decrease in cell motility induced by 1g. The evidence that 1g enhances cell adhesion while decreasing motility is critical regarding cancer cell spreading. Indeed, in various epithelial cancer cell lines, it has been demonstrated that poorly adherent cell populations tend to exhibit higher metastatic potential [

110], suggesting that the adhesiveness of a particular tumor may serve as a physical marker for metastatic activity.

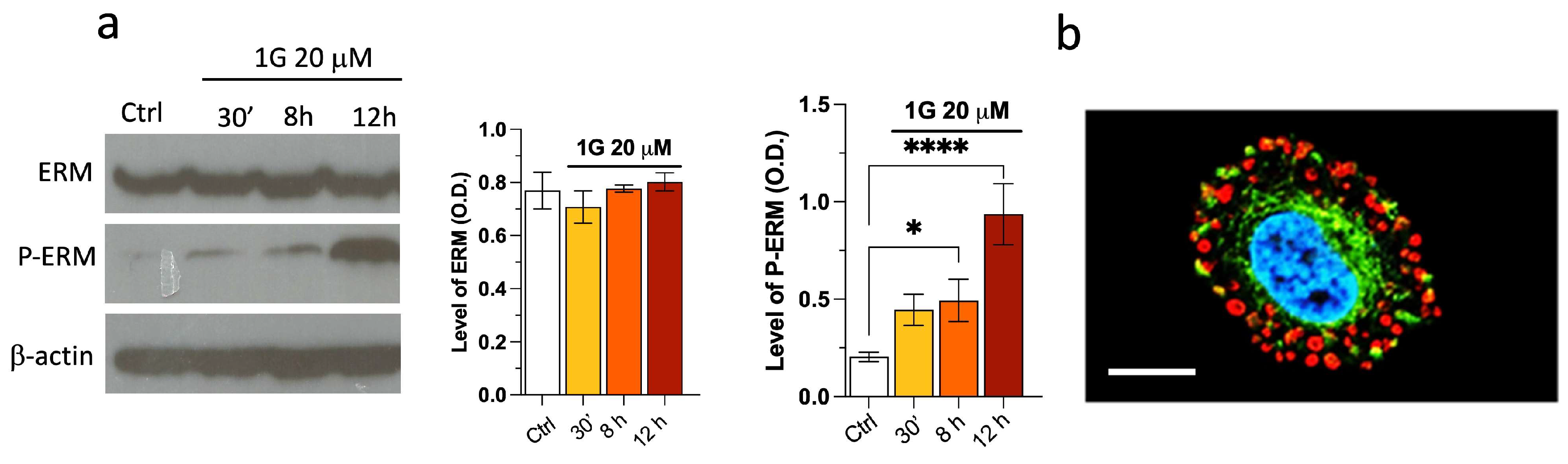

Interestingly, treatment with 1g increased the p-ERM/ERM ratio at both short and long incubation times. This behavior may indicate a feedback mechanism where the cortical actin cytoskeleton attempts to leverage hyper-phosphorylation of ERM proteins to enhance contact with the membrane, resulting in increased cortical tension. Simultaneously, ERM proteins crosslink microtubules to the plasma membrane. Research has shown that destabilization of microtubules can trigger almost instantaneous activation of ERM proteins, facilitating the attachment of cortical actin to the membrane [

111]. This mechanism is responsible for the rounding of cells as they enter the mitotic phase and may explain the rounding of U87MG cells observed immediately after exposure to 1g. In their study, Leguay et al. attributed the strong activation of ERM proteins to pathways associated with RhoA and the release of Ser/Thr kinases from the Ste20-like kinase family (SLK) [

111]. The increase in the pERM/ERM ratio leads to an accumulation of p-ERM proteins near the plasma membrane and around the chromosomes during the mitotic phase. These findings agree with the results reported by Leguay et al. [

111], where an increase in p-ERM, caused by GEF-H1 release due to alterations in microtubule dynamics induced by nocodazole, resulted in a rounded cell shape, similar to what occurs during mitotic entry [

112]. However, we established that the pathway promoted by compound 1g should differ from the effects of nocodazole. At the same time, it has been noted that taxol, a drug that stabilizes microtubules, does not induce an increase in p-ERM. The activation of ERM proteins is not solely dependent on their phosphorylation; rather, their active form is first achieved through interaction with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), while phosphorylation later serves to stabilize this active form [

113]. Once activated, ERM proteins connect actin to the plasma membrane by interacting with membrane receptors such as CD44. CD44 receptors are known to bind hyaluronan in the extracellular matrix and play a key role in cell migration and adhesion. Moreover, CD44 is typically overexpressed in cancer cells, which underscores the relevance of ERM proteins in cell adhesion to substrates. The activation of ERM proteins by microtubule-destabilizing drugs has been reported to induce cell rounding during interphase, akin to the changes that occur when cells enter mitosis [

114]. We can hypothesize a similar mechanism in the case of 1g, involving various proteins such as Rac-1, LIMK, cofilin, and ERM. In fact, Rac-1 has been shown to be crucial for microtubule polarity and, consequently, for proper cell motility and the functioning of kinetochores on mitotic chromosomes [

115]. Additionally, Rac-1 is involved in cell cycle progression, promoting the transition from G2 into the mitotic stages [

116]. We propose that the pathway of 1g action is closely related to the cortical layer of cells, where ERM proteins function, focusing on the connection between the cell membrane and cortical actin. This mechanism is mediated by microtubule dynamics and their association with cell adhesion complexes. For instance, it has been found that the activated and phosphorylated form of ERM proteins can interact with microtubules, stabilizing their connection with the cell membrane. This interaction may lead to the destabilization of focal adhesion complexes and hinder the cells’ ability to polarize [

112]. A comparable situation was observed in migrating keratinocytes, where microtubule stabilization facilitated the disassembly of focal adhesion sites [

117]. Moreover, the instability of microtubule connections with the cortical region of the cells is critical during the mitotic phase. Astral microtubules must maintain stable interactions with the cortical region to ensure correct spindle positioning and the separation of centrosomes, or, in cases of centrosome amplification, to cluster them effectively to form two opposing poles [

118]. This mechanism may explain why 1g can influence the mitotic spindle in various cell types. The resulting effect of ERM activation is an increase in tension within the cortical layer. This observation is consistent with our findings from Micropipette Aspiration experiments. We noted that individual cells within the aggregates became more rounded and independent from one another after exposure to 1g. This effect may explain the decreased surface tension observed in the treated spheroids. The interesting aspect of our analysis is that the effect of the compound 1g varies depending on the cell line being investigated, particularly concerning cell morphology and migration. In the case of NIH3T3 cells, we observed no significant changes in morphology induced by 1g, even at concentrations that led to a loss of polarity in U87MG cells. Additionally, the migration of fibroblasts was minimally affected by 1g. We speculate that this selectivity may be related to the role of microtubules in different cell lines.

4. Materials and Methods

Cell Line and Treatment

The U87MG and NIH3T3 cell lines (ATCC), were cultured on polystyrene culture dishes (Euroclone, Italy) and grown in EMEM, containing 1% Non-essential aminoacids (NEA), 1% Na pyruvate, 1% glutamine, 1% pencillin/streptomycin and supplemented with 10 % FBS (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy). The cells were kept in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until the time of experiments. 1g compound was prepared in DMSO at 100 mM (stock solution) and diluted in medium at the working concentrations. The G166 isolated from malignant glioma that show stem cell properties were a kind gift of Prof. Paolo Salomoni UCL Cancer Institute. The cells were grown in NS cell media (Stemcell Techologies, Canada) add with human EGF and human FGF-2, 10ng/ml of each, (Peprotech, USA) on laminin-coated flask (Merck, Italy), and kept in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

2D Cell Migration

Wound-healing assay was used to assess the effect of 1g on cell migration of glioma cells. U87MG cell lines were seeded in multi-six well plates and cultured until reaching confluence. A 10-µL pipette tip was used to make a straight vertical scratch. The cells were then treated with 1g (20 µM) or medium as a control. Images of the wounds were captured under an inverted light microscope Olympus IX 70 (10X magnification) by time-lapse microscopy for 24 h and measured using Image J software. Time-lapse imaging studies were performed using a phase contrast microscope with a home-developed on-stage cell incubator with a controlled temperature of 37°C, a humidity of 90-95%, and 5% CO

2 [

119]. To perform single cell migration analysis, U87MG were plated at 3.5 × 10

3 cells/cm

2 in a plastic multi-six well plate and in multi-six well plates covered by a thin layer of PDMS to obtain substrates with different value of the Young modulus: 0.2 kPa, 8 kPa, 32 kPa (CytoSoft

® 6-well Plates, Advanced Biomatrix), and PDMS 1:25. The cells were incubated overnight and subsequently observed under the microscope (Olympus IX 70), at 10X magnification. The system takes a photo every 4 minutes. This system allowed us to simultaneously evaluate the effects of 1g at three different concentrations: 5 μM, 10μM and 20 μM. The time-lapse videos were then edited using ImageJ and cell positions were recorded using the manual tracking software of FIJI.

Adhesion Assay

U87MG cells pre-treated (6h with 1g at 20 μM) or not, were grown in 96-well plates pre-coated with BME 0.25% at 90,000 cells/cm2, and incubated or not with 1g at 5,20,50 μM, in serum-free EMEM, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. followed by a wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent cells. The cells were fixed in cold acetone for 15 minutes and stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 1 h and red at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermofisher, Biorad, Bologna).

Western Blot

Proteins were extracted from U87MG control and 1g-treated cells (20 μM) using RIPA buffer (50 mMTris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mMNaCl, 1% Na deoxycolate, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM PMSF) (Sigma Aldrich, Milano, Italy). Lysate proteins were quantified using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Life Technology, Milano, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 5 mg of each sample was loaded onto a pre-cast 5-12% SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy). The membrane was blocked in TBST (20 mMTris- HCl, 0.5 M NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20) buffer containing 5% non-fat dried milk overnight at 4°C and incubated with primary antibody anti-ɑ-actinin (1:1000), anti-paxilin (1:1000), anti-phospho-Erm (phospho-ezrin (Thr567)/radixin (Thr564)/moesin (Thr558) (1:1000), anti-Erm (1:1000), and anti-vinculin (1:1000), anti-phospho-Fak (Y397) (1:1000), anti-Fak (1:1000), anti-RhoA (1:1000), anti-Rac1 (1:1000), at RT respectively for 3 h under gentle agitation (the primary antibodies were from Cell Signaling, USA). After being washed in TBST, the membranes were incubated for 1h with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling, USA) or with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Cell Signaling, USA) and visualized using chemiluminescence method (Amersham, GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Milan, Italy). The immune complexes were analyzed using the Imagestudio lite software with β-actin as loading control.

Spheroid Preparation

For the formation of spheroids, the U87MG cells were seeded in 96-well plates ultra-low attachment (Costar, Corning Inc, Corning, NY) at a density of 500 cells/well in complete medium.

The following day, the spheroids were treated with 1g 20 µM and after 24 hours analyzed with 3D Traction force microscopy and Micropipette Aspiration. For the analysis of spheroid invasion, spheroids were embedded in a Matrigel® gel (10 mg/mL) and their evolution was measured by optical microscopy in bright contrast acquiring an image every hour. The best focused plane was acquired using a 10X objective and the resulting image is obtained stitching 4 fields together in order to capture the whole region of interest For 3D traction Force Microscopy, to assemble the system, we mixed the beads with the Matrigel® and we deposited a layer of the solution in a well of a 96-well-plate. We then waited for the Matrigel® to start the polymerization and we subsequently deposited a spheroid on it. The spheroid was then covered with another layer of the same Matrigel®, a layer of the medium, and we waited another time interval for the polymerization of the newly deposited gel before starting the acquisition of the images.

3D Traction Force Microscopy of Spheroids

The measurements of the traction forces exerted by the spheroids upon the surrounding micro-environment has been evaluated following the protocol developed by ref. [

45] and previously by ref. [

48].

First, the time-lapse images of the spheroids have been aligned to a given frame of reference. Then, the field of displacements (deformations) around the spheroids has been evaluated adopting the PIV method. We used a square window size of 40 pixels with a cut-off of 650 pixels (1 pixel=0.73 μm since the images had been captured using a 20X magnification). The PIV method compares a couple of subsequent images of the sequence identifying the spheroid boundaries, the field displacements (deformations), and eventually the drift correction can be included. The field of displacements are stored in a dedicated subdirectory in .npy python arrays.

Before the final force reconstruction step the look-up table must be evaluated. The lookup table describes the connection between the normalized distance (r/r

0) and the normalized deformation (d/r

0) for different applied pressures. The previous authors [

45] provides a list of several lookup table for Matrigel

® and collagen with different densities. We evaluated the appropriate lookup table for Matrigel

® 10 mg/mL using the semi-affine material model previously exploited by ref. [

48]. This model is able to simulate a non-linear material subdividing his behavior in three different regimes: buckling, linear regime, strain stiffening.

The ε parameter represents the strain, κ0 is the linear stiffness, while d0 and ds are the rate of stiffness change during buckling and stiffening phase, respectively. Finally, εs parameter is the onset of strain stiffening. During the buckling regime the material is under compressions (negative strain) and the fibers constituting the material are not able to respond to the external stimuli, and the stiffness decreases exponentially. For limited positive strains the material produces a linear response. For larger positive strains (above εs) the material undergoes strain stiffening. Since d0, ds and εs are independent with respect to the particular Matrigel® concentration we need to adjust only the linear stiffness parameter before proceeding with the lookup table evaluation.

After obtaining the lookup table for Matrigel® with 10 mg/mL concentration we can pass to the force reconstruction step. To avoid artifacts due to cells close to spheroid boundaries, we reconstruct the force for distances larger than 2 spheroid radii. The results are summarized in a .xls file containing the fitted pressure, the measured contractility, and their angular distributions.

Micropipette Aspiration Technique

The microaspiration of cell spheroids were performed exploiting micropipette prepared by pulling borosilicate capillaries (World Precision Instruments, WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA), 1.5 mm/1 mm O/I diameter) with a double step pulling strategy. The micropipettes were initially thinned using an automatic puller and then were further thinned using a custom-developed puller. A custom developed forge was exploited to cut pipettes in order to have the pipette aperture perpendicular to its longitudinal. Pipettes were fire-polished to ensure good contact with the spheroid and avoid damage to cells in the periphery of the spheroid. To prevent adhesion between the glass sides of the pipette and cells, the micropipettes were pretreated with BSA (10 mg/mL) or Surfasil. In the case of pretreatment with BSA the pipettes were immersed in the BSA solution for 5 minutes and then they were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water before being filled with the same culture medium used to grow the spheroids. In the case of Surfasil pretreatment, the micropipettes were immersed for 5 min. in a toluene diluted Surfasil solution they were subsequently thoroughly washed with toluene and then kept for 10 min. in the oven at 90 °C to allow a complete adhesion of the layer in contact with the pipette glass. Each pipette was then connected to a pneumatic pressure transducer (Lorenz MPCU-3, sensitivity of 1 mm H

2O) to establish a pressure difference between the internal side of the pipette and the external solution. The pressure difference was applied by controlling the air pressure on top of a cylindrical tube containing the culture medium solution. The tube was initially positioned in order to assure the position of the free surface of the culture medium that allowed a negligible starting pressure difference, verified by controlling the null aspiration or repulsion of small objects in solution. The spheroids were kept inside a chamber made by glass-slides separated by a PDMS or Teflon ring allowing the entry of the pipette from one side and the injection of a single spheroid from the other side. The bottom glass of the chamber was pretreated with BSA or Surfasil to avoid adhesion with the spheroid during the time needed to find and grab it with the micropipette. We performed a creep compliance analysis in the time domain analyzing the response of the spheroid inside the micropipette after a pressure difference jump of about 20 cm H

2O (between the internal pipette region and the region just outside the pipette). To analyze the creep behavior, the progressive position of the spheroid protrusion inside the micropipette is measured for 20 min in the aspiration and another 20 min in the release phase by exploiting optical microscopy images and at a rate of 1 frame per min. Images were acquired by an Olympus IX 70 inverted microscope in Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) mode with a 20X or 40X objective. To maintain as much as possible optimal conditions for cells, a closed system was used to inject humidified water vapor at a temperature of 37°C with a CO

2 concentration of 5% (see SI of ref. [

120]). To confirm the state of cells, a LIVE/DEAD cell imaging Kit has been used to establish cell viability on the basis of intracellular esterase activity and plasma membrane integrity (two different filters,FITC and TRITC were used: green → live cells, red → dead cells) (Fig. S2). The images were then analyzed by using the ImageJ software (NIH, Washington, USA) in order to automatically detect the position of the cell protrusion inside the micropipette.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis by AFM

Cells were analyzed with a BioScope I microscope equipped with a Nanoscope IIIA controller (Veeco Metrology, Plainview, NY, USA). The cantilever spring constant has been calibrated using the thermal noise method [

121]. Dynamic mechanical measurements have been performed exploiting a home-developed device that can apply a sinusoidal signal taken from a lock-in amplifier to the z-piezo-scanner of the AFM obtaining a modulation of the cantilever position when a constant indentation is maintained. The other input of the lock-in amplifier is connected to the signal of the cantilever deflection detector. The lock-in amplifier detects the amplitude of the deflection signal and the phase lag between the two signals. Due to the low integration time of the lock-in amplifier and to stability problems of the AFM cantilever, we considered frequencies not lower than 1 Hz (enough cycles must be obtained before the signal stabilizes). When the cantilever oscillates around an indentation δ

0, we can write the following equation [

79]:

where R is the radius of the indenting probe,

F(ω) and

δ(ω) are the periodic force applied by the tip and the sample indentation, respectively. The indentation is obtained by subtracting the cantilever deflection from the piezo vertical displacement. The term

E* is the complex Young modulus in the frequency domain and

is the Poisson ratio. The previous equation is related to the Hertz theory of contact mechanics, whereas rheological investigations typically consider the shear modulus

G. It is possible to consider the parameter G according to the transformation

G=E/2(ν+1). The correspondence principle for linear viscoelasticity allows to write:

where

F(ω) and

δ(ω) are the Fourier transforms of the force and indentation parameters and

G* is the complex shear modulus. The complex modulus can also be written as:

where

is the shear storage modulus (related to elastic behavior) and

is the shear loss modulus (related to viscous dissipation).

F(ω) and

δ(ω) can be written as:

and their ratio is given by:

Considering the expression for the complex shear modulus, we can write:

The phase lag

between the applied force and the cantilever deflection, equivalent to the produced indentation, measured by the AFM detector could be affected by spurious phase lags due to the electronic system (mainly the piezoactuator device) and to the viscous drag of the cantilever when excited to high frequencies. To account for the first spurious contribution, we performed measurements of the phase lag between the two quantities when the cantilever was in contact with a rigid and not deformable surface like mica. Considering that the phase lag observed in this case is not due to a viscous behavior of the indented sample, this value of the phase lag was subtracted from the value we obtained on living cells at different frequencies. To account for the drag force, we included in the formula a dissipative term:

and for

b(0) we took the value reported in the literature for a similar cantilever (

b(0)=5 × 10

−6 Ns/m) [

78,

122].

Ting Model Analysis of Single Force Curves

An extensive rheological analysis of living cells can be realized also considering viscoelastic models to describe the complete approach and retract portions of the force-curve. To perform this analysis, we exploited the Ting model using a procedure similar to the one presented in the work by Efremov et al. [

83]. Briefly, the Ting solution for a rigid pyramidal indenter exerts a force on a viscoelastic material is exploited according to the formulas:

where

F is the tip/sample force

, tind is the time of the entire indentation cycle (approach and retract phases),

tm is the inversion time of the indentation cycle,

t1 is a parameter needed to compensate for the sample relaxation during the retraction phase and it is calculated by the expression reported in the above formula and

E(t) represents the Young’s modulus relaxation expression. For

E we adopted the following expression:

where

t’ corresponds to the sampling time during the force-curve, and

E0 is the instantaneous Young modulus of the sample. The adopted relaxation expression is known as the power law rheology model and it is the typically exploited model for AFM rheological measurements [

83]. Equation (2) is numerically solved and a least squares error fitting procedure using the experimental values of the force is exploited to find the best values for the two parameters E

0 and α. All the force-curve analyses were performed with a home-developed Python software. The vertical scanning tip speed was 8 μm/s, the total z-scan displacement was between 2.5 μm and 3 μm. The fitting procedure was repeated for all the sample points of the Force Volume image (32 × 32 pixels

2) and the average values from force curves obtained over the nucleus region were evaluated. The cells were imaged for a total time of about 3h while keeping the temperature constant at 37°C.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Conceptualization, Riccardo Tassinari, Andrea Alessandrini and Lorenzo Corsi; Data curation, Alessia Gallerani, Domenico Di Rosa, Claudia Cavallini, Martina Marcuzzi, Valentina Taglioli, Andrea Alessandrini and Lorenzo Corsi; Formal analysis, Andrea Mescola, Chiara Zannini, Valentina Taglioli, Beatrice Bighi and Andrea Alessandrini; Funding acquisition, Carlo Ventura, Andrea Alessandrini and Lorenzo Corsi; Investigation, Giorgio Regazzini, Riccardo Tassinari, Alessia Gallerani, Chiara Zannini, Domenico Di Rosa, Claudia Cavallini, Beatrice Bighi and Lorenzo Corsi; Methodology, Giorgio Regazzini, Andrea Mescola, Riccardo Tassinari and Andrea Alessandrini; Resources, Claudia Cavallini, Carlo Ventura and Andrea Alessandrini; Supervision, Vincenzo Zappavigna, Carlo Ventura and Lorenzo Corsi; Visualization, Martina Marcuzzi and Roberta Ettari; Writing – original draft, Giorgio Regazzini, Andrea Mescola, Chiara Zannini, Valentina Taglioli, Beatrice Bighi, Andrea Alessandrini and Lorenzo Corsi; Writing – review & editing, Giorgio Regazzini, Riccardo Tassinari, Vincenzo Zappavigna, Carlo Ventura, Andrea Alessandrini and Lorenzo Corsi. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Figure 1.

a) Normalized equatorial area expansion of a control (DMSO) U87MG spheroid and a spheroid of the same cells treated with 20 μM 1g. The spheroids were embedded inside a Matrigel® matrix as described in Methods; b) Images of a control and of a 1g treated spheroid at different time points. The line highlighting spheroid expansion has been obtained using the Analyze_Spheroid_Cell_Invasion_In_3D_Matrix tool from FIJI. (bar = 200 μm).

Figure 1.

a) Normalized equatorial area expansion of a control (DMSO) U87MG spheroid and a spheroid of the same cells treated with 20 μM 1g. The spheroids were embedded inside a Matrigel® matrix as described in Methods; b) Images of a control and of a 1g treated spheroid at different time points. The line highlighting spheroid expansion has been obtained using the Analyze_Spheroid_Cell_Invasion_In_3D_Matrix tool from FIJI. (bar = 200 μm).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the cell shape between the control sample and the U87MG spheroid exposed to 20 μM 1g. Both spheroids were embedded in a Matrigel matrix. The frames are representative of the spheroids at the beginning of th experiment and after 68 hours. (bar = 50 μm).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the cell shape between the control sample and the U87MG spheroid exposed to 20 μM 1g. Both spheroids were embedded in a Matrigel matrix. The frames are representative of the spheroids at the beginning of th experiment and after 68 hours. (bar = 50 μm).

Figure 3.

Traction Force Microscopy of U87MG spheroids. a) Frames at different time steps of a control U87MG spheroid and of a U87MG spheroid in 15 μM 1g. The spheroids were embedded in a Matrigel® matrix with 5 μm diameter latex beads; b) Representation of the traction force at the end of the experiment for a control and a 1g treated spheroids; c) Plot of the mean contractility as a function of time for spheroids in the different conditions (two experiments for each conditions are reported).

Figure 3.

Traction Force Microscopy of U87MG spheroids. a) Frames at different time steps of a control U87MG spheroid and of a U87MG spheroid in 15 μM 1g. The spheroids were embedded in a Matrigel® matrix with 5 μm diameter latex beads; b) Representation of the traction force at the end of the experiment for a control and a 1g treated spheroids; c) Plot of the mean contractility as a function of time for spheroids in the different conditions (two experiments for each conditions are reported).

Figure 4.

Micropipette aspiration of U87MG spheroids. a) Sequence of three images during the aspiration process of an U87MG spheroid exposed to 20 μM 1g. L represents the length of the tongue to be used for the fitting procedure; b) Representative aspiration and relaxation curves for a control spheroid (black squares) and 1g treated spheroid (red circles). In the plot the regions exploited to obtain vin and vout (see text) are highlighted. The continuous lines represent the fit of Eq. (1) to the data; c) Rheological model exploited to obtain Eq. (1). These experiments indicate that 1g is able to decrease the surface tension and viscosity of U87MG spheroids.

Figure 4.

Micropipette aspiration of U87MG spheroids. a) Sequence of three images during the aspiration process of an U87MG spheroid exposed to 20 μM 1g. L represents the length of the tongue to be used for the fitting procedure; b) Representative aspiration and relaxation curves for a control spheroid (black squares) and 1g treated spheroid (red circles). In the plot the regions exploited to obtain vin and vout (see text) are highlighted. The continuous lines represent the fit of Eq. (1) to the data; c) Rheological model exploited to obtain Eq. (1). These experiments indicate that 1g is able to decrease the surface tension and viscosity of U87MG spheroids.

Figure 5.

Effect of 1g on the morphology of U87MG cells. a) Examples of U87MG cells before the injection of 20 μM 1g into the culture medium and their corresponding morphology 1h after the injection (the markers in each column correspond to 20 m); b) Statistical analysis of the elliptical shape defined as the ratio of the two axes resulting from an elliptical fit of the cell morphology.

Figure 5.

Effect of 1g on the morphology of U87MG cells. a) Examples of U87MG cells before the injection of 20 μM 1g into the culture medium and their corresponding morphology 1h after the injection (the markers in each column correspond to 20 m); b) Statistical analysis of the elliptical shape defined as the ratio of the two axes resulting from an elliptical fit of the cell morphology.

Figure 6.

Cell adhesion assay for U87MG cell line. Cells, pre-treated or not with 1g 20 μM or not, were grown on BME and incubated with EMEM without FBS alone (Ctrl and pre-treated with 1g 20 μM) or with 5, 20, or 50 μM of 1g and expressed as rates of U87MG cell adhesion to culture plates (abs = 540 nm).

Figure 6.

Cell adhesion assay for U87MG cell line. Cells, pre-treated or not with 1g 20 μM or not, were grown on BME and incubated with EMEM without FBS alone (Ctrl and pre-treated with 1g 20 μM) or with 5, 20, or 50 μM of 1g and expressed as rates of U87MG cell adhesion to culture plates (abs = 540 nm).

Figure 7.

Effect of 1g on duplication time; a) Plot of the duplication time (time cells remain rounded in mitosis) as a function of 1g concentration. The red line represents a linear fit to the data. b) Example of cells exiting mitosis and producing more than two daughter cells.

Figure 7.

Effect of 1g on duplication time; a) Plot of the duplication time (time cells remain rounded in mitosis) as a function of 1g concentration. The red line represents a linear fit to the data. b) Example of cells exiting mitosis and producing more than two daughter cells.

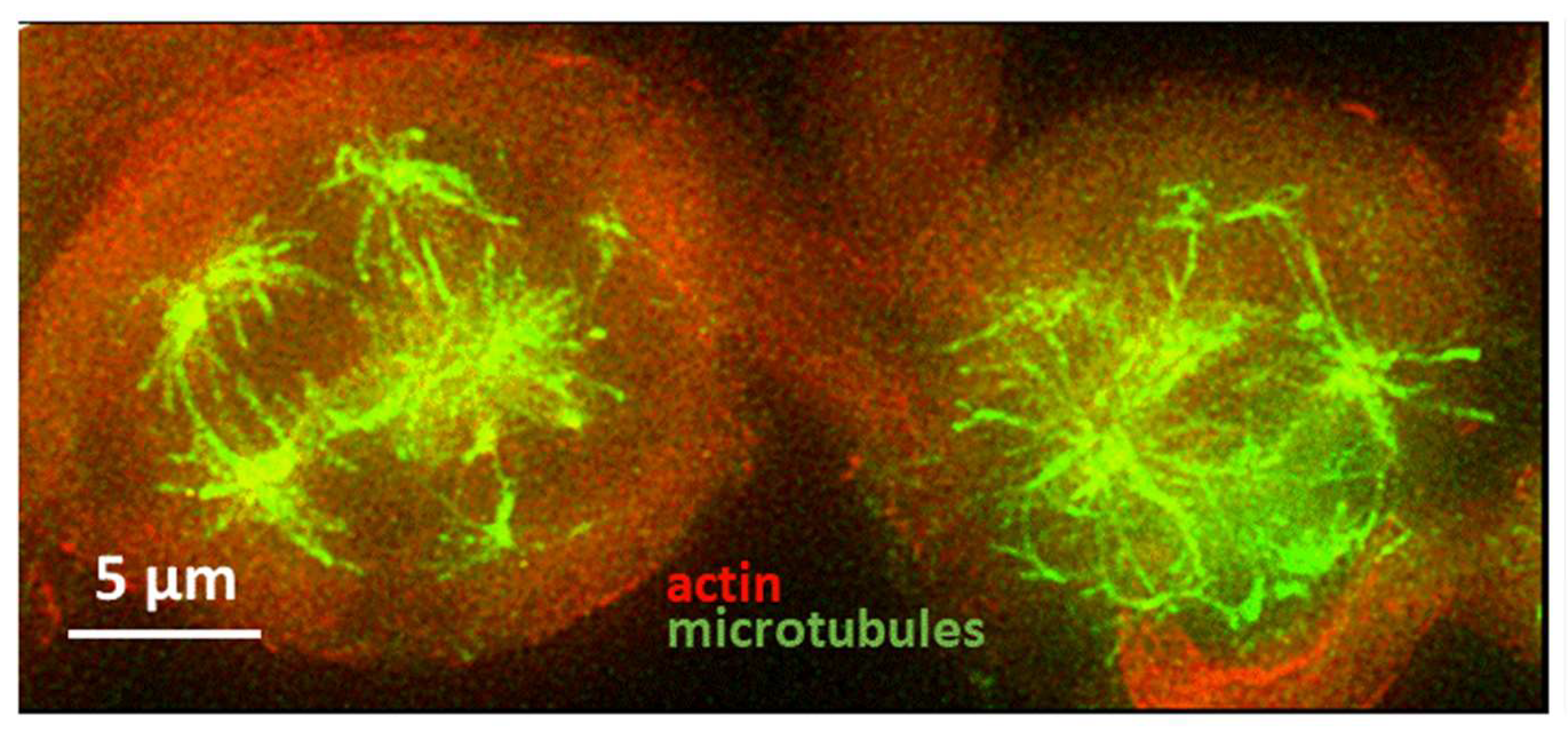

Figure 8.

Multipolar spindle formation. Examples of the presence of more than two asters in the organization of microtubules in mitosis in the presence of 20 μM 1g. The actin cytoskeleton has been marked in red and the microtubules in green.

Figure 8.

Multipolar spindle formation. Examples of the presence of more than two asters in the organization of microtubules in mitosis in the presence of 20 μM 1g. The actin cytoskeleton has been marked in red and the microtubules in green.

Figure 9.

Time-lapse imaging analysis of U87MG cells exposed to 20 μM 1g in mitosis. For 26 cells, by time lapse-imaging, the time spent in mitosis has been recorded. The large majority (78%) of the cells exposed to 20 μM 1g are able to perform mitotic slippage.

Figure 9.

Time-lapse imaging analysis of U87MG cells exposed to 20 μM 1g in mitosis. For 26 cells, by time lapse-imaging, the time spent in mitosis has been recorded. The large majority (78%) of the cells exposed to 20 μM 1g are able to perform mitotic slippage.

Figure 10.

Wound healing assay for control cells and cells exposed to 1g. a) Optical microscopy image of a 2D wound healing assay immediately after the formation of the scratch and after 24h since the formation of the wound both in the absence and in the presence of 20 M 1g; b) time evolution of the still present wound area; c) percentage of wound repair closure after 24h in the absence of 1g and in the presence of 20 μM 1g (p = 0.0049 (**), unpaired t test).

Figure 10.

Wound healing assay for control cells and cells exposed to 1g. a) Optical microscopy image of a 2D wound healing assay immediately after the formation of the scratch and after 24h since the formation of the wound both in the absence and in the presence of 20 M 1g; b) time evolution of the still present wound area; c) percentage of wound repair closure after 24h in the absence of 1g and in the presence of 20 μM 1g (p = 0.0049 (**), unpaired t test).

Figure 11.

Analysis of the MSD of U87MG cells on substrates of different Young modulus and exposed to increasing concentrations of 1g. The MSD vs. time is reported in a Log-Log plot with two lines representing the ballistic and the pure Brownian motion cases. In the inset of each plot, the MSD value at the end of the corresponding plot is reported as a function of the substrate stiffness. The presence of a maximum value of the MSD for an intermediate value of the substrate stiffness for the control case is evident. By increasing the 1g concentration the sensitivity of the MSD value to the substrate stiffness strongly decreases.

Figure 11.

Analysis of the MSD of U87MG cells on substrates of different Young modulus and exposed to increasing concentrations of 1g. The MSD vs. time is reported in a Log-Log plot with two lines representing the ballistic and the pure Brownian motion cases. In the inset of each plot, the MSD value at the end of the corresponding plot is reported as a function of the substrate stiffness. The presence of a maximum value of the MSD for an intermediate value of the substrate stiffness for the control case is evident. By increasing the 1g concentration the sensitivity of the MSD value to the substrate stiffness strongly decreases.

Figure 12.

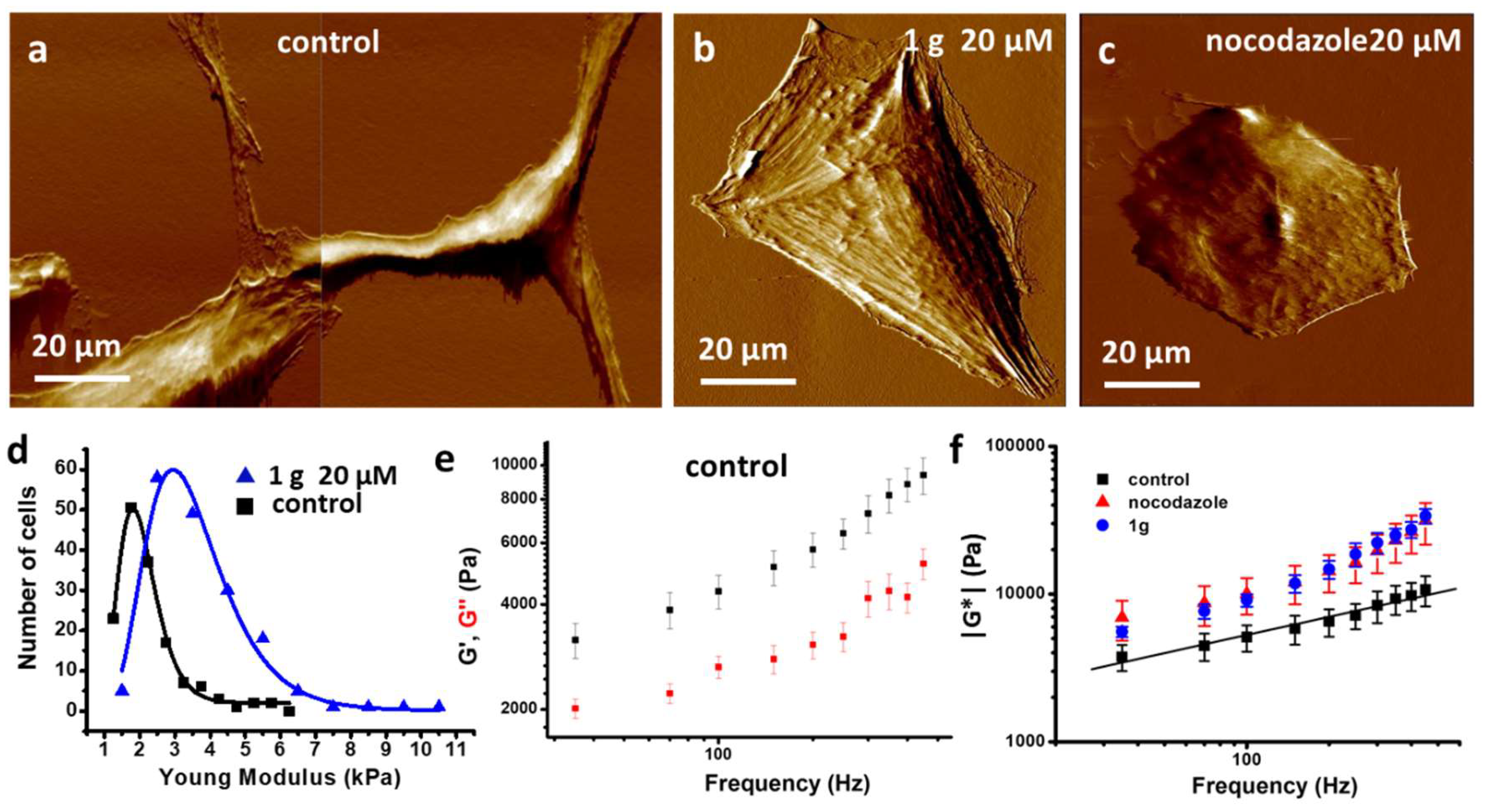

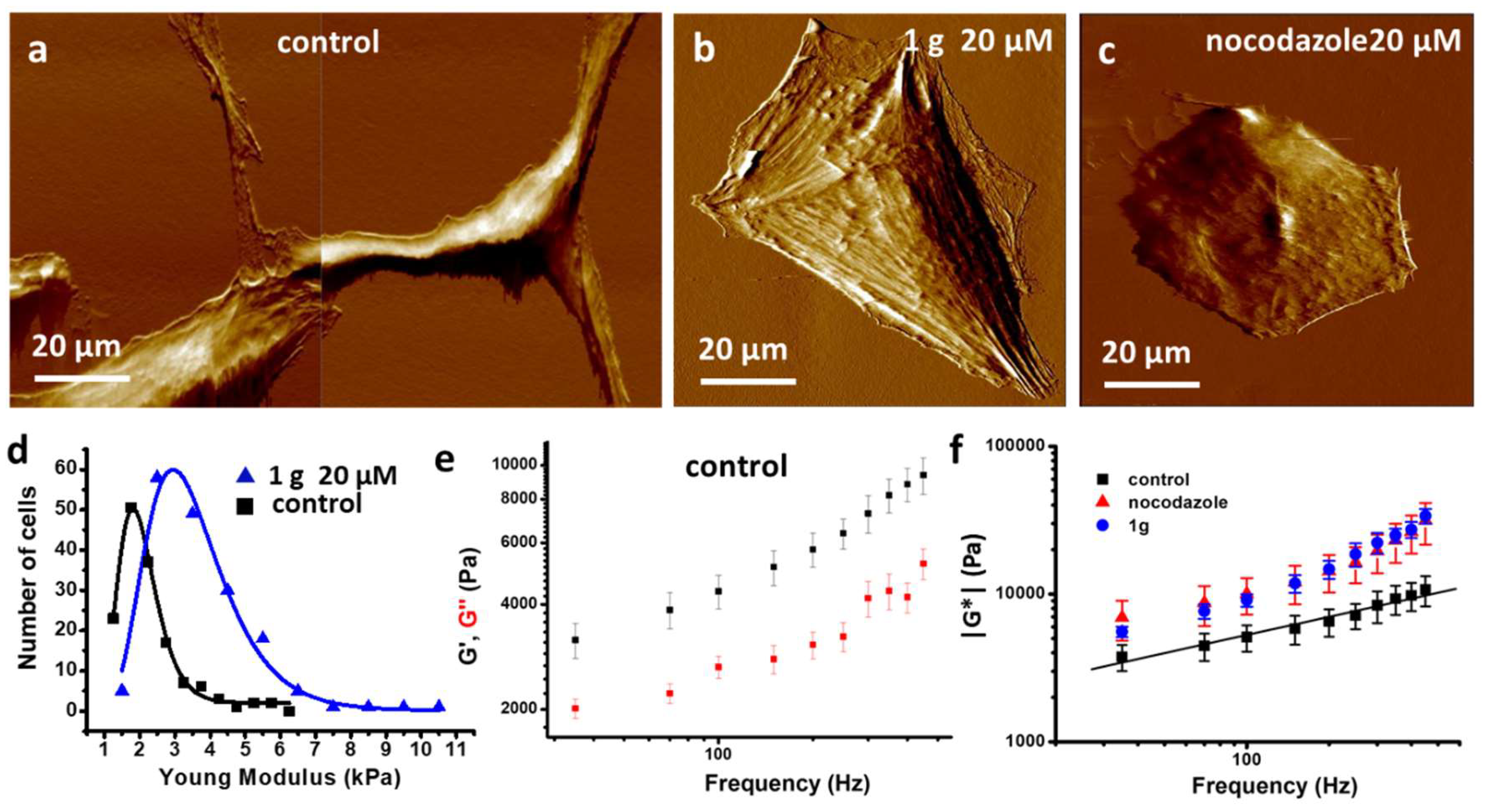

Single-cell mechanical properties measured by AFM: a) AFM image of control U87MG cells; b) AFM image of a U87MG cell exposed to 1g 20 μM for 24 hours; c) AFM image of a U87MG cell exposed to nocodazole 20 μM for 24 hours; d) Distributions of the values obtained for the Young modulus of U87MG cells before (red squares) and after 24 hours in 20 μM 1g. The points in the plot are derived from the distribution histogram of the value. The Young Modulus was obtained by fitting the force curves with a modified Hertz model; e) Elastic (G’, red squares) and viscous (G’’, black squares) components of the shear modulus G* as a function of the frequency of the sinusoidal signal applied to the cantilever base by the piezoactuator in control U87MG cells; f) Comparison of the modulus of the complex shear modulus G*, as a function of frequency, of U87MG cells for untreated, exposed to 20 μM 1g for 24 h and exposed to 20 μM nocodazole for 24 h. Data represent the average value and the standard deviation of N = 7 cells for each condition. The slope of the linear fit to the control cell data is =0.33.

Figure 12.

Single-cell mechanical properties measured by AFM: a) AFM image of control U87MG cells; b) AFM image of a U87MG cell exposed to 1g 20 μM for 24 hours; c) AFM image of a U87MG cell exposed to nocodazole 20 μM for 24 hours; d) Distributions of the values obtained for the Young modulus of U87MG cells before (red squares) and after 24 hours in 20 μM 1g. The points in the plot are derived from the distribution histogram of the value. The Young Modulus was obtained by fitting the force curves with a modified Hertz model; e) Elastic (G’, red squares) and viscous (G’’, black squares) components of the shear modulus G* as a function of the frequency of the sinusoidal signal applied to the cantilever base by the piezoactuator in control U87MG cells; f) Comparison of the modulus of the complex shear modulus G*, as a function of frequency, of U87MG cells for untreated, exposed to 20 μM 1g for 24 h and exposed to 20 μM nocodazole for 24 h. Data represent the average value and the standard deviation of N = 7 cells for each condition. The slope of the linear fit to the control cell data is =0.33.

Figure 13.

a) Expression of ERM and pERM proteins in U87MG cells exposed to 20 μM 1g. The analysis shows the strong increase of the pERM/ERM ratio; b) immunofluorescence of a typical U87MG cells 30 min after injection of 20 μM 1g: pERM (red), microtubules (green), DNA (blue) (bar = 20 μm).

Figure 13.

a) Expression of ERM and pERM proteins in U87MG cells exposed to 20 μM 1g. The analysis shows the strong increase of the pERM/ERM ratio; b) immunofluorescence of a typical U87MG cells 30 min after injection of 20 μM 1g: pERM (red), microtubules (green), DNA (blue) (bar = 20 μm).

Figure 14.

Effect of 1g on protein involved in cell adhesion and motility. (A) Representative western blots of a-actinin, paxilin, vinculin, FAK, Rac-1, cofilin, P-cofilin, and LIMK at different time points; (B), densitometric evaluation of protein levels in U87MG cell lysate after incubation with 20 μM of 1g for 5 or 12 h. Densitometry values were normalized to the protein loading control, beta-actin. The values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (n = 3 per group). *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05 vs. untreated cells (Ctrl), using One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s as post test.

Figure 14.

Effect of 1g on protein involved in cell adhesion and motility. (A) Representative western blots of a-actinin, paxilin, vinculin, FAK, Rac-1, cofilin, P-cofilin, and LIMK at different time points; (B), densitometric evaluation of protein levels in U87MG cell lysate after incubation with 20 μM of 1g for 5 or 12 h. Densitometry values were normalized to the protein loading control, beta-actin. The values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (n = 3 per group). *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05 vs. untreated cells (Ctrl), using One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s as post test.