1. Introduction

1.1. The Need to Change Design Thinking

Architecture and design profoundly influence human health, cognition, and emotions through the body’s visual interaction with the physical environment. Living geometry can be derived from Christopher Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties, integrating biological and mathematical principles to create environments that enhance human well-being. Unlike axiomatic geometric systems in mathematics, living geometry is complex and merges fractal hierarchies, strong centers, positive space, and coherence—qualities consistently linked to human neurophysiological preferences [

1].

Contemporary architecture, in contrast, is guided by stylistic trends and theoretical constructs divorced from empirical validation [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. This paper argues that such approaches not only fail to address the needs of building users but also actively undermine cognitive function and long-term health. The epistemological gap between these conflicting paradigms necessitates a shift toward evidence-based design frameworks rooted in living geometry. Arguments are presented here for a new paradigm in architectural and urban design.

It is worth noting the reasons for why we find ourselves in this situation today, although providing a historical explanation is not the goal of this paper. How can society follow a design philosophy that does not respond to human biology? Architects operating within a narrow framework value artistic originality, formal innovation, and stylistic movements more than emotional well-being and empathy in designs. Groundbreaking research on biophilia and environmental enrichment [

10,

11,

12,

13] therefore has difficulty penetrating this dominant system. Resistance is motivated by four entrenched positions:

(a) Philosophical bias — dismisses evidence-based approaches as reductive and a threat to architecture as an art form;

(b) Detached formality — teaches architects to see buildings as formal compositions rather than lived experiences;

(c) Institutional inertia — makes architecture schools and professional organizations cling to established narratives and pedagogical models that favor abstraction over emotional engagement; and

(d) Market and media forces — reward iconic, provocative designs to promote “starchitect” culture instead of adaptive, human-centered ones.

It is important to know the obstacles to be faced in introducing a different design paradigm. A breakthrough helping this project is the application of AI both to judge and to generate adaptive designs. With the appropriate prompts, AI large-language models draw upon vast datasets of cross-disciplinary evidence for adaptive design. The ability to perform these two complementary tasks sidesteps the usual opposition to human-centered design approaches coming from the architectural establishment, which doggedly promotes its dominant styles. AI-generated designs have their own logical structure that is independent of the architectural establishment’s design ideology.

1.2. Outline of this Paper

Section 2 introduces Christopher Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties of living geometry, such as fractal scaling, strong centers, and nested symmetries, linking them to human cognitive engagement and well-being. These properties provide a diagnostic and generative toolkit for adaptive design. AI can be used as an effective tool in both assessing the 15 properties in existing designs and creating new designs that prioritize living geometry principles.

Applying AI to generate environments aimed at enhancing creativity is illustrated through six visual examples (

Section 3). These environments embody living geometry and are suggested to improve creative output by aligning with human neurocognitive preferences, fostering positive emotional states, and reducing stress.

Section 4 evaluates AI’s capability to systematically detect Alexander’s 15 properties in images, by analyzing the six figures. AI derives living geometry principles by highlighting the creative potential of working environments.

Section 5 underscores the health implications of environmental geometry, referencing research that connects coherent, fractal-rich spaces to enhanced well-being, faster recovery, and reduced stress. It argues for the measurable benefits of living geometry in physical and mental health contexts.

Summarizing the potential of living geometry to boost creativity,

Section 6 gathers support from interdisciplinary findings in neuroscience and psychology. These insights are complemented by anecdotal evidence from Christopher Alexander’s workspaces (

Section 7), emphasizing the influence of the environment on creative productivity.

Section 8 critiques contemporary architectural practice for its reliance on ideological aesthetics and resisting empirical validation.

Section 9 advocates replacing this flawed approach with the scientifically-validated basis of living geometry. A human-centered epistemological framework for design aligns with human biology and fosters enriching, health-promoting environments. The conclusion (

Section 10) calls for embracing evidence-based principles of design to improve human creativity and well-being.

2. Living Geometry and Christopher Alexander’s 15 Fundamental Properties

Living geometry encompasses spatial forms and relationships that arise naturally in biological and harmonious, stable inanimate systems. Its properties, such as emergent coherence, fractal scaling, and nested symmetries, resonate with human cognitive and emotional processes [

1,

2]. Living geometry integrates aesthetic with functional dimensions, fostering a deep connection between individuals and their surroundings. One approach to living geometry is through Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties, listed as follows:

1. Levels of scale

2. Strong centers

3. Thick boundaries

4. Alternating repetition

5. Positive space

6. Good shape

7. Local symmetries

8. Deep interlock and ambiguity

9. Contrast

10. Gradients

11. Roughness

12. Echoes

13. The void

14. Simplicity and inner calm

15. Not-separateness

Alexander’s 15 properties provide a practical toolkit for creating and diagnosing living geometry. These geometrical properties act synergistically to generate environments that evoke calm, promote cognitive engagement, and reduce stress. A very promising implementation is to use the 15 properties in a prompt for AI large-language models (which is done here). Several extended descriptions of the 15 properties available online can be attached to a design question [

14,

15,

16]; this paper uses the Appendix from Ref. [

17]. So far, the results from combining AI with the 15 properties are remarkable. The prompts lead the AI program directly to living geometry, but without explicitly directing it.

This new tool has two distinct applications. First, used as a diagnostic, AI can evaluate an image for the presence of the 15 properties; and second, as a guide for generating new designs that adapt to human biology.

Living geometry refers to geometrical arrangements, forms, and patterns that reflect biological complexity, coherent organization, fractal scaling, and symmetry. These mechanisms of visual ordering lead to harmonious, stable structures that are comfortable for the brain to process. Biophilia, natural fractals, and symmetry groups provide a conceptual foundation for living geometry independently of Alexander’s 15 properties [

18]. The present author gives a detailed mathematical model in [

18], which will not be reproduced here. Living geometry’s main features can be summarized as:

1. Multiscalar: Repetitive forms appear at different scales (approximate fractal scaling), creating a hierarchy of visual information.

2. Symmetry-rich: Employs reflectional, rotational, translational, and spiral symmetries, as well as combinations thereof.

3. Highly-connected: Elements are intertwined via alignments, coherent organizational principles, and nesting (smaller elements fit inside larger ones).

4. Vertically-aligned: All intermediate and large-scale symmetries cooperate to help define the gravitational axis.

5. Emergent & complex: The whole becomes more than the sum of its parts through hierarchical organization and “emergent” patterns.

The living geometry underlying both organisms and evolved architecture (such as traditional and vernacular buildings and cities) has particular and specific properties. Current research uncovers the link between the geometry of the environment and human neurophysiological responses [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Living geometry triggers positive-valence responses, whereas its absence triggers negative-valence responses. The latter situation comes from visual fields situated at opposite scales of an informational spectrum: either empty (no information, providing no clue for a survival response), or disordered (random information, which overwhelms the sensory system).

Designers would surely like to know how to benefit from living geometry. Firstly, designed products will have greater unconscious appeal if they incorporate some elements of living geometry. Secondly, the preceding discussion helps to focus on designing visual environments that can aid the designer unconsciously. Can creative output be influenced by the setting in which a person is working? Observations answer yes; however, the architectural profession has yet to give an unambiguous response to this question. This paper presents AI experiments and data from neuroscience to support a model for enhancing creativity.

3. AI Generates Environments That Boost Creativity

Six figures were created by the large-language model ChatGPT-4o, which uses DALL•E 3 for image generation. The prompts asked the software to illustrate visual environments that would enhance creative thinking unconsciously. The first three examples are for general settings, whereas the last three are supposed to specialize for creativity in different professions: mathematics (

Figure 4), architecture (

Figure 5), and cross-disciplinary work on AI, human biology, and neuroscience (

Figure 6).

Note that ChatGPT draws upon open-source scientific data to generate these figures, so these should not be misinterpreted simply as pretty graphics motivated by artistic interest. The crucial aspect of the epistemological framework is rigorously evidence-based, as discussed in detail in

Section 6, below. The captions were generated by the software and are reproduced here unedited. The figures also use color for a positive effect, whereas the discussion in this paper is limited to geometrical qualities. Color contributes an important factor to creativity, and that dimension will be analyzed in a future study.

Figure 1.

A visual representation of an environment designed to foster creativity, based on experimental findings on neural engagement. The patterns, colors, and textures aim to stimulate creative thinking by promoting neural combinations conducive to innovation. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 1.

A visual representation of an environment designed to foster creativity, based on experimental findings on neural engagement. The patterns, colors, and textures aim to stimulate creative thinking by promoting neural combinations conducive to innovation. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 2.

An abstract mural representation designed to encourage creative thought subconsciously. Its dynamic patterns, harmonious colors, and natural forms are crafted to subtly inspire and energize those working nearby. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 2.

An abstract mural representation designed to encourage creative thought subconsciously. Its dynamic patterns, harmonious colors, and natural forms are crafted to subtly inspire and energize those working nearby. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 3.

Here is an abstract painting designed to catalyze creative thought by engaging the viewer’s neural circuits in a positive way. This work avoids representational imagery and instead relies on harmonious patterns, subtle asymmetries, and dynamic color interplay to evoke curiosity, exploration, and mental clarity. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 3.

Here is an abstract painting designed to catalyze creative thought by engaging the viewer’s neural circuits in a positive way. This work avoids representational imagery and instead relies on harmonious patterns, subtle asymmetries, and dynamic color interplay to evoke curiosity, exploration, and mental clarity. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 4.

Here is a mural crafted to stimulate mathematical creativity and cross-disciplinary problem-solving. The design integrates geometric and organic patterns with mathematical elements, encouraging innovative and non-traditional thinking. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 4.

Here is a mural crafted to stimulate mathematical creativity and cross-disciplinary problem-solving. The design integrates geometric and organic patterns with mathematical elements, encouraging innovative and non-traditional thinking. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 5.

Here is a mural designed to inspire architectural creativity, capturing the rhythm, harmony, and complexity of classical, traditional, and folk architecture. It emphasizes intricate patterns, organic forms, and a warm, inviting palette to evoke emotional connection and encourage human-centered architectural designs. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 5.

Here is a mural designed to inspire architectural creativity, capturing the rhythm, harmony, and complexity of classical, traditional, and folk architecture. It emphasizes intricate patterns, organic forms, and a warm, inviting palette to evoke emotional connection and encourage human-centered architectural designs. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

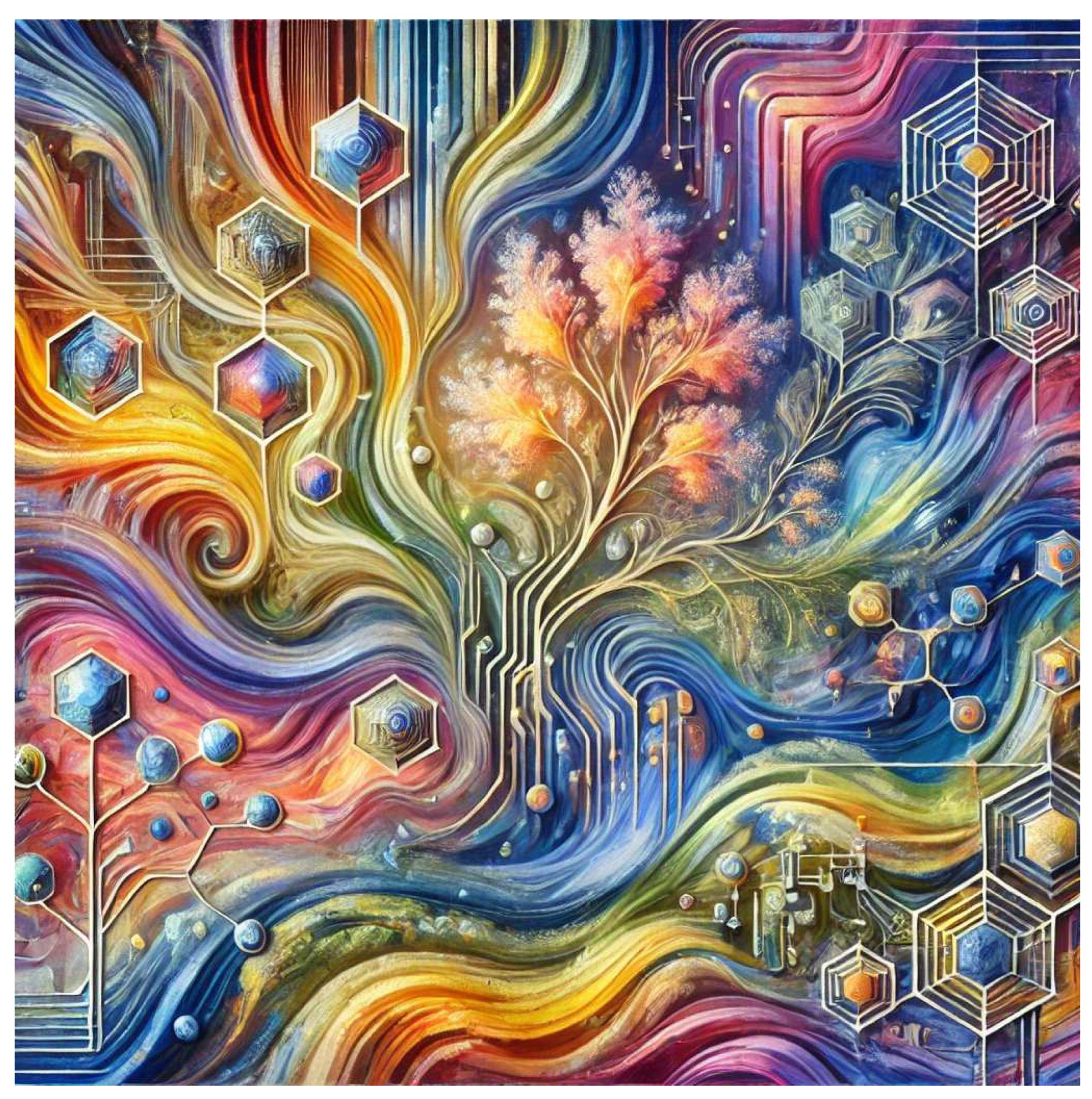

Figure 6.

Here is an abstract painting designed to evoke creativity and inspire innovative thinking by blending elements of AI, neuroscience, and human biology. It incorporates flowing organic forms, vibrant colors, and intricate details that align with the prompts. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

Figure 6.

Here is an abstract painting designed to evoke creativity and inspire innovative thinking by blending elements of AI, neuroscience, and human biology. It incorporates flowing organic forms, vibrant colors, and intricate details that align with the prompts. Figure and caption by ChatGPT-4o, prompted by the author.

These graphics could be discussed at great length as to how appropriate they would be for decorating offices and workplaces to boost creativity. Maybe they are too distracting, or maybe not. After one century during which industrial modernism has dominated workspaces, people are not used to such lively visual stimulation, hence that revelation may be disconcerting at first. What is certain, however, is that all these figures satisfy living geometry. This consistency will be verified by a further analysis also using large-language models (carried out below).

This AI exercise is intended to encourage longitudinal research into which visual characteristics of physical environments help creative thought. Limitations in the above results should be recognized and overcome. The software will produce paintings that incorporate images of neurons and other organic forms that are irrelevant to the question. Instead, it is the painting that should stimulate creative thinking because its specific visual details and the overall composition trigger neural processes that catalyze creative thought. The geometry itself may be the actual driver of creative cognition and occupant well-being.

The software gets the causality wrong, because architects and interior designers mistakenly believe that images representing details of work in those fields (e.g., literal representations of creative domains such as binary code or drawings of neurons) will affect brain circuits in a positive way. Assertions about creativity or design appear in architectural discourse but cannot be found in cognitive science or psychology journals. An architect might claim that certain images “promote creative work” without objective research (e.g., cognitive or physiological data) to back it up. Conceptually-misleading ideas thus get repeated in professional magazines, thereby contaminating the data bank from which the large-language model draws upon.

Progress in this direction must replace a cycle of unverified claims with a body of credible knowledge. Creative environments have to be empirically tested rather than ideologically asserted. AI-aided verification will use large-language models (LLMs) not merely to compile texts but to filter them according to evidence quality. LLMs can be fine-tuned to evaluate source hierarchy. Prompts should ask an LLM to highlight contradictory data, flag claims that lack references, and identify missing references. Rather than just copying popular opinion, longitudinal datasets should build open databases on creativity metrics.

4. Large-Language Models Pick Out the 15 Fundamental Properties

The six figures generated by AI above were evaluated by ChatGPT-4o with an uploaded detailed description of Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties. This list is published as an Appendix to Ref. [

18] and was attached to the large-language prompt as a pdf file. The software was asked to analyze each graphic and list which of the 15 properties were present to a notable degree. The results are now discussed. To illustrate the type of response obtained, here is an unedited analysis for how each of the 15 properties is represented in the painting shown as

Figure 3:

“Levels of Scale: The artwork shows a clear hierarchy of patterns, with varying levels of detail from small intricate forms to broader, more generalized ones. These scales are distinct and harmonious, spaced in magnification factors conducive to perceptual coherence.

Strong Centers: There are multiple focal points in the painting, defined both explicitly and through the interaction of surrounding forms. These centers are reinforced by their surrounding elements, creating a nested and balanced composition.

Thick Boundaries: Borders within the artwork are proportional and help define enclosed regions. The use of thickness enhances visual focus and emphasizes the interplay between different parts of the composition.

Alternating Repetition: The painting includes rhythmically repeating patterns with variations, avoiding monotony. This alternation contributes to visual harmony and engagement.

Positive Space: Each region within the painting feels complete and well-defined. The interplay of convex and concave forms ensures that all areas contribute to the overall coherence, leaving no sense of fragmentation.

Good Shape: The shapes in the painting are cohesive and visually graspable, aligning with natural principles of compactness and aesthetic balance. These forms reduce cognitive overload and enhance perceptual clarity.

Local Symmetries: The painting contains small-scale symmetrical elements that contribute to its overall harmony. These symmetries are not rigid but flexible, enhancing a sense of order within the complexity.

Deep Interlock and Ambiguity: Interlocking patterns and transitions in the painting create a sense of interconnectedness. Elements overlap and blend into each other, enhancing the perception of unity and complexity.

Contrast: Effective use of contrast in color and texture highlights differences while maintaining unity. This ensures a dynamic but coherent composition.

Gradients: Gradual transitions in the painting’s colors and textures provide a sense of continuity and flow, avoiding abrupt disruptions.

Roughness: A degree of natural imperfection in the patterns adds character and authenticity, breaking regularity while preserving coherence.

Echoes: Repeated motifs across different scales tie the composition together, creating unity and reinforcing the painting’s cohesive structure.

The Void: Open spaces within the artwork balance denser areas, ensuring the composition feels neither cluttered nor empty. These voids provide a sense of openness and relief.

Simplicity and Inner Calm: Despite its complexity, the painting achieves a sense of calm through harmonious integration of elements. There is no unnecessary detail, which prevents distraction.

Not-Separateness: All elements of the painting feel deeply connected, with no artificial breaks. This seamless integration ensures that the artwork feels like a coherent whole.”

Repeating this exercise with the other five generated figures gives very similar results. The actual prompt demanded further details, namely, to rank the presence of each of the 15 properties according to its relative strength. This analysis distinguished strongly-present from weakly-present properties and identified properties that were either negligible or very weak. Those detailed analyses are not included here, but suffice it to say that ChatGPT found most of the 15 properties in each of the illustrated figures. For reference, the quantitative estimates of how many properties are present, and to what degree, are listed in

Table 1.

How accurate are these evaluations? To determine this, the six graphics would need to be judged by one or more humans who are familiar with living geometry and Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties. It is not strictly necessary to do this, since the author considers that the software is reasonably accurate in picking out the presence of the 15 properties, which is good enough for the present model. General questions of how accurate a large-language model can be in detecting the 15 properties in an image are discussed in Ref. [

18].

To summarize this AI experiment, the same ChatGPT software generated the six figures, then analyzed them for their degree of living geometry by measuring Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties. What is astonishing is that the 15 properties were not inputted as part of the prompt: the question asked the software to discover and represent visual environments conducive to creative thought. The 15 properties were the output to this question, not its input.

5. Environmental Factors Directly Affect Health and Well-Being

This research topic is currently being investigated through converging cross-disciplinary techniques. Nevertheless, so far, the focus has been on more tangible factors causing harm such as pathogens, pollutants, noise, etc. instead of the impact of visual/geometrical information. And yet, the human body is strongly influenced by the visual field even though the effect is in large part unconscious.

Research from, environmental psychology, neuroscience, and public health confirms that the geometry of the physical environment significantly impacts physical and mental health. For example, Roger Ulrich’s studies show that patients recover faster and require fewer painkillers if their hospital room looks onto natural scenes [

24,

25]. Environmental stress research finds that settings with fractal patterns and biophilic features reduce cortisol (stress hormone) levels and promote overall well-being [

26,

27]. A positive correlation between health and living geometry is well-established in the medical literature [

28].

Living geometry offers a rigorous, evidence-based approach bridging aesthetic and biological needs. While living geometry resonates with Christopher Alexander’s observations about his “fifteen fundamental properties” for life-enhancing design, it also aligns with findings from biophilic design [

11,

14]. Living geometry is not merely a stylistic preference; it represents an approach that maps onto underlying biological and cognitive processes. The experience of positive-valence information characterized by balanced symmetries, harmonious geometrical relationships, and scaling hierarchies has measurable restorative effects.

Current research consistently underscores the effect of built environments on human psycho-physiology. Those studies include randomized controlled trials in hospital settings, longitudinal studies on mental health and neighborhood design, and large-scale correlational research linking nature integration with reduced stress and improved cognitive function. Robust evidence from multiple fields is rapidly accumulating, and it supports this paper’s thesis.

6. What Is the Scientific Evidence that Living Geometry Boosts Design Creativity?

A preliminary discussion by the present author indicates a link between physical environments that embody living geometry, and a person’s creative output while working in such an environment [

18]. The best type of experiment is a longitudinal study in classrooms and offices whose output is supposed to be creative thought. Applying neuroscience methods (EEG, fMRI, etc.) to architectural settings holds promise for linking specific geometric attributes to brain activity and creative performance. Such studies are time-consuming; hence a shortcut is most welcome. AI might provide this shortcut.

The hypothesis that living geometry can boost design creativity is supported by observations that human beings tend to respond positively to environments with coherent, fractal, and naturalistic qualities. Interdisciplinary work and preliminary research suggest that certain geometric qualities in the built environment—particularly those derived from biological forms and processes—foster heightened cognitive engagement and creative thinking. Environments rich in coherent complexity, fractal scaling, and nested symmetries can enhance emotional well-being, lower stress, and potentially free mental capacity for creative exploration.

Studies in conceptual blending (where visual cues can serve as inputs for a blending process that allows for novel combinations of ideas) and priming (where visual cues activate related semantic concepts in the brain leading to new insights on a problem) show that visual cues can spark new ideas. Conversely, visual monotony reduces the incidental sparks that feed lateral thinking. Sterile environments (e.g., uniform white walls with no stimulation) do not provide enough spontaneous cues or triggers for associative thinking. This is a question of the highest importance to designers in all fields of application, which should challenge investigators to design and perform the relevant experiments.

The visual environment affects cognitive load, mood, and the subconscious processes underlying creativity. Multiple studies converge on the idea that moderate visual stimulation, nature references, and a sense of comfort and control can all boost background associative thinking. Several interrelated pathways linking creativity to living geometry can now be documented.

1. Enhanced Cognitive Engagement and Reduced Mental Fatigue. Spaces with coherent complexity can promote mental restoration, a concept akin to what is observed in biophilic design. A comfortable, restorative environment correlates with improved focus and problem-solving—a key ingredient for creativity. Visual complexity with nested scales (often found in natural systems) is linked to increased interest and reduced stress. Observers unconsciously process—and feel rewarded by—the layered symmetries and “self-similar” patterns characteristic of living geometry. Key brain processes that open the door to creativity include attention restoration and stress reduction through reduced amygdala activation (the stress response center). Increased parasympathetic activity allows a “rest and digest” state conducive to creative thinking. Studies in neuroaesthetics using fMRI [

29,

30] have discovered reduced stress-related activity in participants viewing coherent and symmetrical designs. Lower stress and restored attention free up mental resources for creative ideation (generating new ideas). Living geometry—rich in fractal scaling, organic coherence, and symmetries—can facilitate these restorative effects. Dopamine release in the reward circuitry (ventral striatum), correlates with positive mood states. The “Broaden-and-Build” theory [

31] describes how positive emotions expand cognitive scope, enabling people to see more connections (an essential creative skill).

2. Positive Emotional Resonance. Visual coherence and harmony in the environment (through balanced symmetries) can foster an emotional state conducive to exploration and imagination. Lowered “visual entropy” (or noise) frees cognitive resources for more creative tasks. Creativity thrives when cognitive load is not hijacked by stress or anxiety. “Attention Restoration” theory [

32] shows that naturalistic environments (which often have fractal or coherent spatial organization) help restore depleted attentional resources. When attention is replenished, individuals perform better on creative problem-solving tasks [

33]. Alpha brain waves are frequently linked to cognitive flexibility, idea generation, and “lightly focused” attention—important for contemplative and integrative thinking. When the brain encounters coherent fractal or symmetrical structures, it tends to shift into a calm-yet-engaged mode (boost in alpha waves, potential Default Mode Network (DMN) activation). This physiological state is linked to ideation and insight generation through mind wandering [

34]. The DMN lights up when individuals are not actively attending to external tasks, allowing for the free-form combination of ideas that is a key process in creativity. EEG studies [

35,

36] found that individuals viewing fractal-based images (scaled patterns reminiscent of nature) show increases in alpha activity and higher activation-relaxation balance. Among key brain processes, alpha wave enhancement (8–12 Hz), often associated with a relaxed yet alert state, is conducive to creative insight [

37]. This mental state, when restorative environments improve attention, correlates with better performance on creative tasks [

38,

39].

3. Alignment with Human Neurophysiology. The shape of experienced space influences human psycho-physiology [

40]. Positive affective response correlates with physiological changes such as reduced stress markers (e.g., lowered cortisol) and stable heart rates. Studies by Taylor and colleagues [

41,

42] of fractal patterns in artwork have shown that humans exhibit physiological stress reduction (e.g., reduced skin conductance, blood pressure, heart rate) when viewing fractal geometries within a certain complexity range (linked to a median fractal dimension around 1.3–1.5). Neurological research points to our brains being “tuned” to recognize and process certain levels of fractal complexity efficiently, which may clear mental capacity for creative work. A calmer, less stressed mental state allows more cognitive “room” for divergent thinking. Coherent symmetric patterns (like those found in living geometry) lead to less neural “noise” hence are more efficient in neural pattern recognition. Work on neuroaesthetics shows that recognition of symmetrical, self-similar structures triggers faster “liking” judgments [

43], thus preserving more cognitive bandwidth for creativity. The hippocampus and associated cortical regions code hierarchical spatial relationships, aiding in mapping large, complex environments. The effortless “readability” of multiscale, well-structured spaces primes the mind to see nested, overlapping relationships in ideation [

44].

Filling the current research gap on this crucial question requires collaboration among designers, neuroscientists, and psychologists. It would be wise to avoid introducing architectural bias, however. As this paper argues, conventional design training creates a predisposition for aesthetic preferences among architects leading to disengagement [

10]. Living geometry itself is a complex system involving psychological, spatial, and visual dimensions, making controlled experiments difficult. Also, creativity is multifaceted and challenging to measure consistently—researchers need metrics that capture different types of creative output (artistic, conceptual, problem-solving, etc.).

Despite these gaps, the convergence of attention restoration research, neuroaesthetic findings, stress reduction data, and the psychology of positive affect all underscore that geometry in our environment matters—and that a certain type of coherent, biologically-rooted geometry may prime the human mind for imagination and insight. Moving forward, more empirical research—especially controlled longitudinal studies of people working in settings imbued with living geometry—would help clarify this interaction mechanism. If future findings confirm that living geometry can potentially boost creative output, architects and designers could systematically integrate these principles into diverse fields (e.g., healthcare facilities, schools, workplaces) to foster more creatively stimulating and healthier environments.

Living geometry—with its coherent complexity, fractal scaling, organic connections, and symmetry—has multiple avenues to potentially enhance creativity. By engaging the brain’s natural preference for fractal/nested structures, inviting positive emotional states, reducing stress, and supporting hierarchical thinking, it aligns with known neuroscientific and psychological factors that facilitate creative output. While still awaiting more controlled experiments, the current evidence suggests a significant link between human creative performance and living geometry.

7. Christopher Alexander’s Working Environment

This section adds anecdotal support to this paper’s thesis, and it would be a shame not to include it here. The present author worked with Christopher Alexander over several decades to edit Alexander’s 4-volume book series

The Nature of Order [

1,

2,

45,

46]. This collaboration involved frequent visits to Alexander’s homes in Berkeley, California, then Chichester, West Sussex, UK. Some readers may be aware that Alexander was a passionate lover of oriental carpets and wrote an important book on the subject [

47]. In both his residences, his working environment was surrounded by beautiful old carpets hanging on the walls and lying on the floor.

This information is relevant to the present discussion because hand-made carpets embody color together with living geometry to an astonishing degree. Alexander’s later books reveal that studying the patterns on his carpets helped him in deriving the 15 fundamental properties [

16,

48]. So, we have here a creative individual producing innovative thinking in his architecture and writings certainly being influenced by the visual characteristics of the environment in which he worked. That visual information field, first in Berkeley, then in Chichester, was defined by living geometry.

While it would be interesting to be able to corroborate this speculation by seeing the working environments of many creative individuals, that task is best left to other investigators. It is known that different persons thrived in different settings, although we know that nature walks — the original source for living geometry — boost creative thought. This fact has been documented for some time. For indoors, an article in Canva compared creative persons’ offices, including those of Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs, and concluded that “Minimalism might be killing your creativity” [

49]. Studies have indeed identified minimalistic environments as discouraging creativity [

50].

8. Flaws of Contemporary Architectural Practice

Modern architectural practice lacks a coherent epistemological foundation [

8,

9,

10]. Its guiding principles are still shaped by unverified factors that are listed below. This controversial statement is justified by uncovering the foundational links to experimentally verifiable principles, or their absence. For more than one century, dominant architectural culture has implemented a set of principles that are never explicitly stated. We get in their stead a narrative about design ideology and politics. The present author attempted to create an open-access database of design experiments, physiological data, and user surveys, so that claims can be quickly verified [

10].

Contemporary designs prioritize abstraction and aesthetic novelty, often adhering to minimalism and industrial modernism without examining evidence of their impact on users [

51]. Theoretical frameworks rarely incorporate findings from environmental psychology or neuroscience, which document the detrimental effects of incoherent and information-poor environments on health and cognition [

20,

52]. The profession cavalierly rejects empirical evidence, as dogma and style rule over substance. Architectural education and practice reinforce stylistic preferences by dismissing scientific validation as irrelevant to design creativity [

53]. Because of the fragmentation and siloing of knowledge, conventional approaches cannot identify health-based design decisions.

Many architects and urban designers operate within a theoretical framework centered on formalistic, “invented codes”, seldom verified or tested against measurable human health outcomes. Practice shuns direct testing or validation. This amounts to invention without verification, which has become accepted as normal. As a result, the built environment often alienates users, generating disconnection and stress rather than fostering emotional and physical comfort and well-being. This now standard approach to design constitutes a radical break between an evidence-based methodology generating living geometry, and contemporary architecture’s invented theoretical constructs.

A conspicuous gap remains where a rigorous comparison between a theoretical narrative and empirically-confirmed design principles should occur. By institutionalizing a philosophical basis separated from evidence-based validation, architecture splits into parallel domains. Consequently, even when research confirms strong correlations between health outcomes and specific spatial patterns, mainstream practice often overlooks or rejects this input. This schism marks a profound divide in architectural knowledge.

Today, buildings and urban spaces arise from an “ideological stance” rather than data on user health or well-being. Urban design lacking human-scale patterns and fractal elements correlates with feelings of alienation, increased stress, and even heightened risks of non-communicable diseases linked to sedentary, isolating lifestyles. The psychological toll—such as higher rates of anxiety and depression —is thoroughly documented in the environmental psychology literature [

54,

55,

56].

AI is misused to generate artistic designs that really do not satisfy their function. For example, AI can generate a photorealistic depiction of an imaginary university building dedicated to creative work in fields like Computer Science, Mathematics, or Molecular Biology. Architects will present an exterior design as a striking “futuristic” blend of concrete, glass, and steel with a flowing, organic geometry that “suggests” creative processes. Walls curve and intersect in unexpected yet harmonious ways, evoking the idea of branching molecules, fractals, or neurons. An angular, sculpted entrance or façade incorporates diagonals and large geometric shapes to convey organic flow and free structure. Intricate, laser-cut metal screening on portions of the façade will suggest branching molecular structures or mathematical patterns. Subtle but eye-catching artistic flourishes—like etched patterns on the glass— evoke abstract network diagrams.

All the above design elements are inappropriate because they “suggest” creative notions instead of embodying human-centered techniques to elicit and nourish creative thought processes. Ignorant of how architecture influences creativity, architects substitute irrelevant visual representations for science. They add surface decoration onto the glass curtain-walls purely for spectacle. The dangerous flaw with “fashion-based” aesthetics is that current design thinking is detached from biological processes and reality. Yet dominant architectural culture has convinced itself, and clients, that this totally superficial approach to design is valid.

9. An Epistemological Framework Replaces Conventional Architectural Theory

Given the growing volume of confirmatory evidence, relying on an archaic theoretical stance that promotes purely aesthetic or stylistic dogmas and ignores or denies health data is indefensible. Because architecture shapes daily life—affecting everything from healing to stress levels—neglecting empirical evidence about spatial geometry is no longer a “neutral” choice; it is a choice that potentially harms the users’ health. Living geometry provides a practical toolkit to incorporate and validate health-based criteria in design decisions. As new AI-driven, empirical, and medical research continues to emerge, any architectural approach that neglects these findings can be viewed as endangering human well-being.

AI-based design evaluations yield a lesson: the software’s conclusions invariably “speak the language” of living geometry. This insight is extraordinary because the prompts do not introduce mathematical descriptors; they explicitly ask for predictions about creative output and emotional impact. Yet the AI’s reasoning resonates with Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties, underscoring how living geometry — bridging architectural beauty, creativity, emotional responses, and healing environments — extends beyond a descriptive tool. It provides a unifying epistemological framework capable of explaining phenomena and revealing their foundational logic.

The synthesis offered by living geometry contrasts with the current architectural paradigm, which remains detached from empirical evidence. AI demonstrates that living geometry’s principles are not only fundamental to human perception but also computationally identifiable, lending it both explanatory and predictive power across disciplinary boundaries. This universal structure underlies everything from biology, to emotions and subjective beauty, to objective algorithmic output and pattern formation. What emerges is a promise for joining contemporary architectural practice with evidence-based design.

Living geometry provides a useful epistemological framework for discussing emotional responses to a building, healing environments, human-computer interfaces, intelligence, learning environments, and settings that catalyze creativity. More than just a descriptive tool, it connects different types of knowledge that might otherwise seem unrelated. Living geometry has explanatory and predictive power because it describes phenomena and also helps to understand their underlying reason. Medical and scientific data warrant replacing existing design methodology by the principles of living geometry.

10. Conclusions

This paper proposed living geometry as a scientifically-grounded epistemological framework for architectural and design practices. Studies on biophilia and environmental enrichment demonstrate that environments rich in coherent symmetries and fractal patterns enhance cognitive engagement, promote healing, and reduce stress. By contrast, prevailing approaches, which are identified as stylistically-driven, are detached from human biological and cognitive needs. The architectural discipline’s existing epistemological framework is deeply flawed because it disregards evidence of how built environments affect human health. This argument is built around evidence from artificial intelligence, biology, environmental psychology, and neuroscience, and proposes a paradigm shift toward designs that harmonize with human neurophysiology.

AI-driven analysis can diagnose and optimize designs. Through the visual analysis of AI-generated environments, this study demonstrated that designs embodying living geometry not only align with human cognitive and emotional processes but are also profoundly supportive of human creativity and life. These findings affirm that AI, when properly guided, can create adaptive designs rooted in living geometry, bypassing the stylistic biases entrenched in current architectural discourse. By integrating Christopher Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties, living geometry bridges aesthetic considerations with human neurophysiological needs, offering a powerful tool for enhancing creativity.

The importance of these results lies in their potential to redefine how environments are designed from now on. Evidence from environmental psychology and neuroscience supports the argument that living geometry is critical for both mental and physical well-being. The AI-driven analysis further highlights the practical feasibility of incorporating these empirically-validated principles into real-world applications. Ultimately, this research advocates for a paradigm shift in design education and practice, replacing dominant but still untested models with evidence-based methods. Failing to do so misses an opportunity to enhance well-being and arguably constitutes a disservice to the public, whose health depends on evidence-based design.

Supplementary Materials

The detailed list of Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties is available online at:

Preprints.org.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

ChatGPT-4o and ChatGPT o1 were asked questions whose answers are quoted in the text. The six figures were drawn by ChatGPT-4o, which also generated their captions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander, C. The Nature of Order. Book 2: The Process of Creating Life. Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, CA, USA.

- Salama, A.M. Spatial Design Education: New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond, Routledge: London, UK, 2017.

- Buday, R. The Confused and Impoverished State of Architectural Research. Common Edge, 27 July 2017. Available online: https://commonedge.org/the-confused-and-impoverished-state-of-architectural-research/ (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Dickinson, D. Everything Is Changing: But Not Architecture’s “Deep State”. Archinect, 28 June 2018. Available online: https://archinect.com/features/article/150070952/everything-is-changing-but-not-architecture-s-deep-state (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Tzonis, A. Architectural education at the crossroads. Frontiers of Architectural Research 2014, 3, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groat, L.N.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods, 2nd Ed., New York, NY: Wiley & Sons, 2013.

- Mitrović, B. Architectural Principles in the Age of Fraud. Oro Editions: Novato, CA, USA, 2022.

- Pedersen, M.C.; Orfield, S.J. A Top Building Researcher Asks: Why is Architecture Afraid of Science? Common Edge, 24 September 2017. Available online: https://commonedge.org/a-top-building-researcher-asks-why-is-architecture-afraid-of-science/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Salingaros, N. A. Architectural Knowledge: Lacking a Knowledge System, the Profession Rejects Healing Environments That Promote Health and Well-being, New Design Ideas, 2024, 8(2), 261–299. [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Heerwagen, J.; Mador, M. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. John Wiley: New York, USA, 2008.

- Joye, Y. Architectural lessons from environmental psychology: The case of biophilic architecture, Review of General Psychology, 2007, 11(4), 305–328. [CrossRef]

- Salingaros, N.A. The biophilic healing index predicts effects of the built environmenton our wellbeing. Journal of Biourbanism 2019, 8, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design. New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press.

- Mehaffy, M. The Impacts of Symmetry in Architecture and Urbanism: Toward a New Research Agenda. Buildings 2020, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, R.P.; Quillien, J. A search for beauty/A struggle with complexity: Christopher Alexander. Urban Sci. 2019, 3(2), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salingaros, N.A. Christopher Alexander’s 15 Fundamental Properties, Architexturez. Chapter from Unified Architectural Theory: Form, Language, Complexity. Sustasis Press, Portland, Oregon, USA, 2013. Available online: https://patterns.architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-172521 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Salingaros, N.A. Living geometry, AI tools, and Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties, Frontiers of Architectural Research, ??, 2025.

- Salingaros, N.A. Symmetry gives meaning to architecture, Symmetry: Culture and Science 2020, 31(3), 231–260. [CrossRef]

- Sussman, A.; Hollander, J.B. Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment (2nd ed.). Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021.

- Zeki, S. Beauty in Architecture: Not a Luxury—Only a Necessity. Special Issue: Beauty Matters: Human Judgement and the Pursuit of New Beauties in Post-Digital Architecture. Archit. Des. 2019, 89, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, D.H. Beauty, Neuroscience, and Architecture: Timeless Patterns and Their Impact on Our Well-Being; Fibonacci Press: Denver, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, C. Architectural Allostatic Overloading: Exploring a Connection between Architectural Form and Allostatic Overloading. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paiva, A. Neuroscience for Architecture: How Building Design Can Influence Behaviors and Performance. J. Civil Engineering and Architecture 2018, 12, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Biophilic Theory of Research for Healthcare Design, Chapter 6 of: Kellert, S.R.; Heerwagen, J.; Mador, M. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. John Wiley: New York, USA, 2008, 87–106.

- Ulrich, R.; Quan, X.; Joseph, A. Choudhary, R.; Zimring, C. (2004). The Role of the Physical Environment in the Hospital of the 21st Century: A Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity.

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Daily, G.C. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2012, 1249, 118–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.R.; Gillespie, B.W.; Chen, S.Y. Urban nature experiences reduce stress in the context of daily life based on salivary biomarkers. Frontiers in Psychology, 2019, 10, Article 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.P. The Potential of Biophilic Fractal Designs to Promote Health and Performance: A Review of Experiments and Applications. Sustainability 2021, 13, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, A.; Vartanian, O.; Kenett, Y.N.; Nadal, M.; Hartung, F.; Hayn-Leichsenring, G.; Navarrete, G.; González-Mora, J.; Chatterjee, A. Psychological and neural responses to architectural interiors. Cortex 2020, 126, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, A.; Weinberger, A.; Chatterjee, A. (2023). How architectural design influences emotions, physiology, and behavior. In M. Skov & M. Nadal (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of neuroaesthetics (pp. 194–217). Routledge, UK.

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56(3), 218–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective.

- Atchley, R.A.; Strayer, D.L.; Atchley, P. Creativity in the wild: improving creative reasoning through immersion in natural settings. PLoS One. 2012, 7(12), e51474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.C.; Spreng, R.N.; Ellamil, M.; Andrews-Hanna, J.R.; Christoff, K. The wandering brain: meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of mind-wandering and related spontaneous thought processes. Neuroimage. 2015, 111, 611–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerhall, C.M.; Laike, T.; Taylor, R.P.; Küller, M.; Küller, R.; Martin, T.P. Investigations of human EEG response to viewing fractal patterns”, Perception 2008, 37, 1488–1494. 37. [CrossRef]

- Hägerhäll, C.M.; Purcell, T.; Taylor, R.P. Fractal dimension of landscape silhouette outlines as a predictor of landscape preference, Journal of Environmental Psychology 2004, 24(2), 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Fink, A.; Benedek, M. EEG alpha power and creative ideation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 44(100), 111–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: a literature review on restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4(4), 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2005, 25(3), 249–259. [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, O.; Navarrete, G.; Chatterjee, A.; Fich, L.B.; Leder, H.; Modroño, C.; Nadal, M.; Rostrup, N.; Skov, M. Impact of contour on aesthetic judgments and approach-avoidance decisions in architecture, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110 (supplement 2), 10446–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. P.; Juliani, A. W.; Bies, A. J.; Spehar, B.; Sereno, M. E. The implications of fractal fluency for bioinspired architecture. J. Biourbanism, 2017, 6, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.P. Reduction of physiological stress using fractal art and architecture. Leonardo 2006, 39, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, T.; Höfel, L. Aesthetic judgments of novel graphic patterns: analyses of individual judgments. Percept. Mot. Skills, 2002, 95(3-Pt1), 755–766. [CrossRef]

- Mikiten, T.M.; Salingaros, N.A.; Yu, H.S. Pavements as Embodiments of Meaning for a Fractal Mind. Nexus Network Journal 2 (2000), 63–74. Reprinted as Chapter 7 of A Theory of Architecture, 2nd Edition, Sustasis Press, Portland, Oregon, USA, 2014.

- Alexander, C. The Nature of Order, Book 3: A Vision of a Living World, Center for Environmental Structure: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005.

- Alexander, C. The Nature of Order, Book 4: The Luminous Ground, Center for Environmental Structure: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004.

- Alexander, C. A Foreshadowing of 21st Century Art: The Color and Geometry of Very Early Turkish Carpets, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1993. Available online: https://archive.org/details/AForeshadowingOf21stCenturyArt/page/n9/mode/2up (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Seamon, D. Review of “Christopher Alexander, A Foreshadowing of 21st Century Art: The Color and Geometry of Very Early Turkish Carpets, 1993”, Environmental & Architectural Phenomenology Newsletter, 1993, 6(1), 5–10. Available online: https://www.patternlanguage.com/carpets/revieweap.htm (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Tate, A. The famous creatives that a had messy desk and why you should too, Canva, 17 June 2015. Available online: https://www.canva.com/learn/creative-desks/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Vohs, K.D.; Redden, J.P.; Rahinel, R. Physical Order Produces Healthy Choices, Generosity, and Conventionality, Whereas Disorder Produces Creativity. Psychological Science, 2013, 24(9), 1860–186. [CrossRef]

- Curl, J. S. (2018). Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism. Oxford University Press.

- Valentine, C. The impact of architectural form on physiological stress: a systematic review. Frontiers In Computer Sci. 2024, 5, 1237531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, C.; Mitcheltree, H. Architecture and bioethics: investigating the ethical implications of recent advances in the field of neuroarchitecture, Intelligent Buildings International, 2024, 16(1), 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W. The built environment and mental health. J. Urban Health, 2003, 80(4), 536–55. [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H. Beyond toxicity: human health and the natural environment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20(3), 234–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liu, N.; Polemiti, E.; Garcia-Mondragon, L.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Lett, T.; Yu, L.; Nöthen, M.M.; Feng, J.; Yu, C.; Marquand, A.; Schumann, G. Effects of urban living environments on mental health in adults. Nature Medicine 2023, 29(6), 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).