1. Introduction

Accurate ocular biometry is indispensable in modern ophthalmology, particularly for intraocular lens (IOL) power calculation during cataract surgery and refractive procedures. This precision highlights the clinical goal of minimizing refractive errors, thereby enhancing both surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction [

1,

2]. Over recent decades, advances in optical biometry have largely replaced earlier ultrasound techniques, offering non-contact methods with improved accuracy and reproducibility [

2,

3].

Technological innovations have introduced various measurement systems, including Partial Coherence Interferometry (PCI), Optical Low Coherence Reflectometry (OLCR), Optical Low Coherence Interferometry (OLCI) and Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography (SS-OCT). While PCI, pioneered by the IOLMaster series, set a gold standard for decades, limitations in dense cataracts prompted the development of OLCR / OLCI and SS-OCT technologies, which achieve higher penetration and resolution [

4,

5]. These advancements are critical, as accurate axial length (AL) and keratometry measurements contribute to up to 54% of refractive prediction errors in cataract surgery [

2,

6].

SS-OCT has emerged as a transformative innovation, leveraging longer wavelengths for superior tissue penetration and imaging depth. Devices like the IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) or Argos (Movu, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) not only ensure high reproducibility but also allow the visualization of entire ocular structures, offering diagnostic advantages beyond biometric measurements [

7,

8]. Comparative studies have consistently shown the reliability of SS-OCT across diverse patient populations, including those with challenging conditions such as dense cataracts [

9,

10].

Despite the consensus on the superior imaging capabilities of SS-OCT, the agreement between this technology and OLCI remains a critical area of investigation. OLCI devices, such as the Lenstar (Haag-Streit AG, Köniz, Switzerland) or Aladdin (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), have long demonstrated high repeatability and ease of use, particularly in cases with clear optical pathways [

11,

12]. However, head-to-head comparisons reveal nuanced differences in measurements such as anterior chamber depth (ACD) and lens thickness (LT), which may influence IOL power predictions [

13,

14].

The potential impact of these measurement differences extends to clinical outcomes. Studies exploring IOL power calculations based on formulas like Barrett Universal II and Haigis underscore the importance of precise biometry [

15,

16]. While both OLCR / OLCI and SS-OCT technologies achieve clinically acceptable levels of agreement, subtle variations in parameters such as AL and ACD may affect refractive outcomes in specific patient cohorts [

17,

18].

This study aims to compare the agreement of a SS-OCT and an OLCI biometer, focusing on their clinical utility in precise ocular biometric measurements critical for cataract surgery and refractive outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Ethics, and Informed Consent

This retrospective, observational study analyzed refractive and visual outcomes in patients who underwent successful cataract surgery. The research was conducted within the Ophthalmology Department at the "Victor Babeș" University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Timișoara, Romania, over the timeframe of January 2022 to June 2024. The study complied with the ethical standards set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Given its retrospective nature, the institutional ethics committee waived the need for specific approval. Additionally, all participants had provided informed consent for their surgeries, which included permission for the use of their data in research. Throughout the study, patient confidentiality was rigorously protected.

2.2. Subjects and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Patients selected for this study were those who underwent uncomplicated cataract surgery with IOL implantation. Biometric data collection using either SS-OCT (Movu, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) or OLCI (Aladdin, Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) devices was guided by clinical workflow and equipment availability, ensuring a comparable distribution of cases for comparison.

Eligibility criteria included: (1) Eyes with no history of trauma or injury. (2) No previous ocular surgeries. (3) Absence of systemic conditions that could affect ocular health. (4) Preoperative corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) of 0.4 logMAR or better. (5) Corneal astigmatism with a regular pattern. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) A history of corneal ectasia. (2) Significant dry eye syndrome. (3) Retinal disorders. (4) Previous refractive surgery.

2.3. Procedure

All patients underwent a detailed preoperative ophthalmic examination, including biometric measurements with both SS-OCT and OLCI devices. The measurements included AL, ACD, LT, keratometry (flat, steep, and axis), and white-to-white corneal diameter (WTW). These variables were measured sequentially using both devices, with the order of device usage randomized to minimize bias. To ensure consistent tear film quality, patients were instructed to blink before each measurement. For each patient, three consecutive scans were performed, and the average results were analyzed.

2.4. Biometers

Biometric measurements were conducted using two advanced optical devices. The Argos® biometer (Movu Inc., Komaki, Japan), which operates on SS-OCT technology, utilizes a 1060 nm light source and incorporates segmental refractive indices (cornea: 1.376; aqueous and vitreous: 1.336; lens: 1.410) to enhance measurement accuracy. On the other hand, the Aladdin® biometer (Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) employs OLCI with an 830 nm light source and a Placido disk for keratometry.

2.5. Agreement Analysis and Statistical Methods

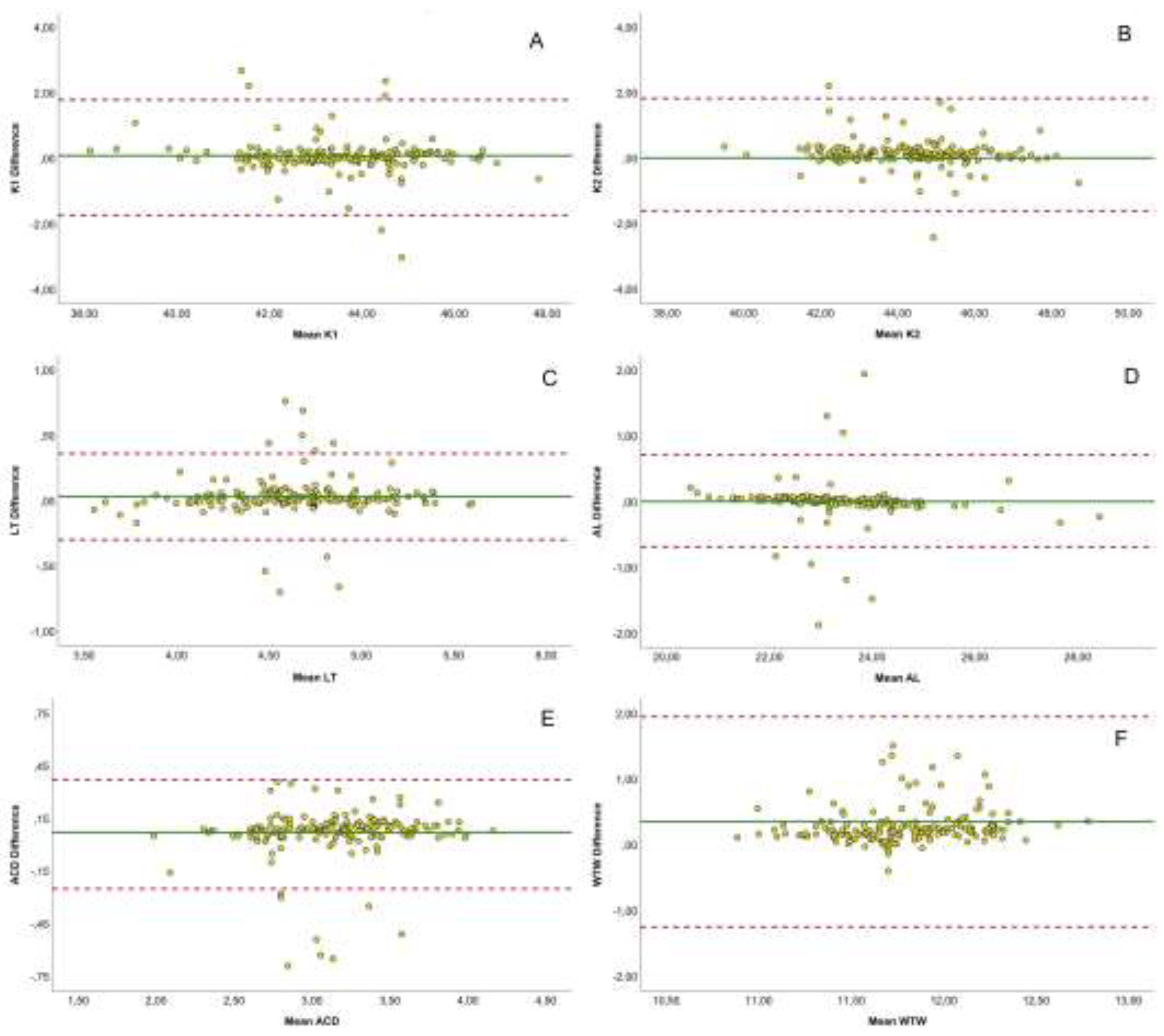

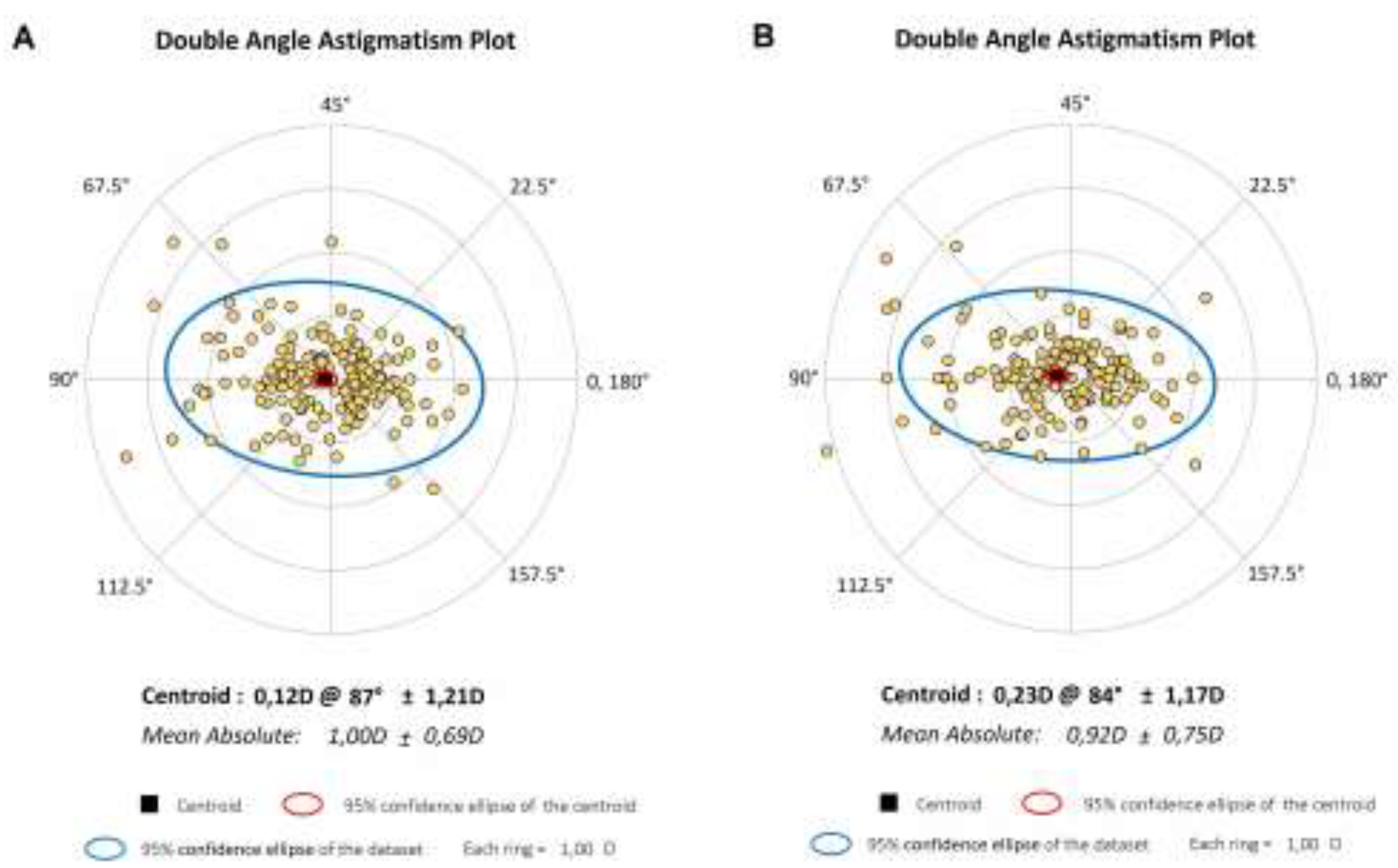

The agreement between biometric measurements obtained from the SS-OCT and OLCI devices was evaluated for key parameters, including flat and steep keratometry, AL, ACD, LT, and WTW. Bland-Altman plots were used to assess the differences between the devices, providing a visualization of the mean difference and 95% limits of agreement (LoA). Astigmatism parameters were analyzed using double-angle plots, which mapped astigmatism power and axis with Jackson cross-cylinder vectors (J0, J45). The centroid and 95% confidence ellipses of the dataset were plotted for each biometer to evaluate the distribution and agreement of astigmatism-related measurements.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and ranges, were calculated for all variables. The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Paired t-tests were employed to detect significant differences between the two devices. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to quantify linear relationships, and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were used to evaluate reliability and agreement between the two measurement methods. ICC values were categorized as poor (<0.5), moderate (0.5–0.75), good (0.75–0.9), or excellent (>0.9).

3. Results

The study evaluated a total of 170 eyes from 102 patients, with a mean age of 68.88 ± 10.82 years, ranging from 40 to 86 years. The cohort comprised 57 males (55.9%) and 45 females (44.1%). The preoperative refractive data showed a mean spherical equivalent of 0.36 ± 3.17 D, with individual values ranging from -13.13 to 8.63 D. The mean sphere was 0.46 ± 3.07 D, with a range from -12.00 to 8.00 D, while the mean cylinder was -0.10 ± 1.57 D, ranging from -4.50 to 4.25 D. The axis of astigmatism varied widely, with a mean of 80.59° ± 60.45° (range: 0° to 180°). Visual acuity, assessed using CDVA (LogMAR), had a mean value of -0.39 ± 0.31, with values between 0.00 and 1.70. Intraocular pressure ranged from 10.0 to 27.5 mmHg, with a mean of 15.97 ± 3.44 mmHg. These descriptive statistics provide a comprehensive overview of the baseline characteristics of the study population and their refractive status, serving as the foundation for the comparative analysis between SS-OCT and OLCI measurements.

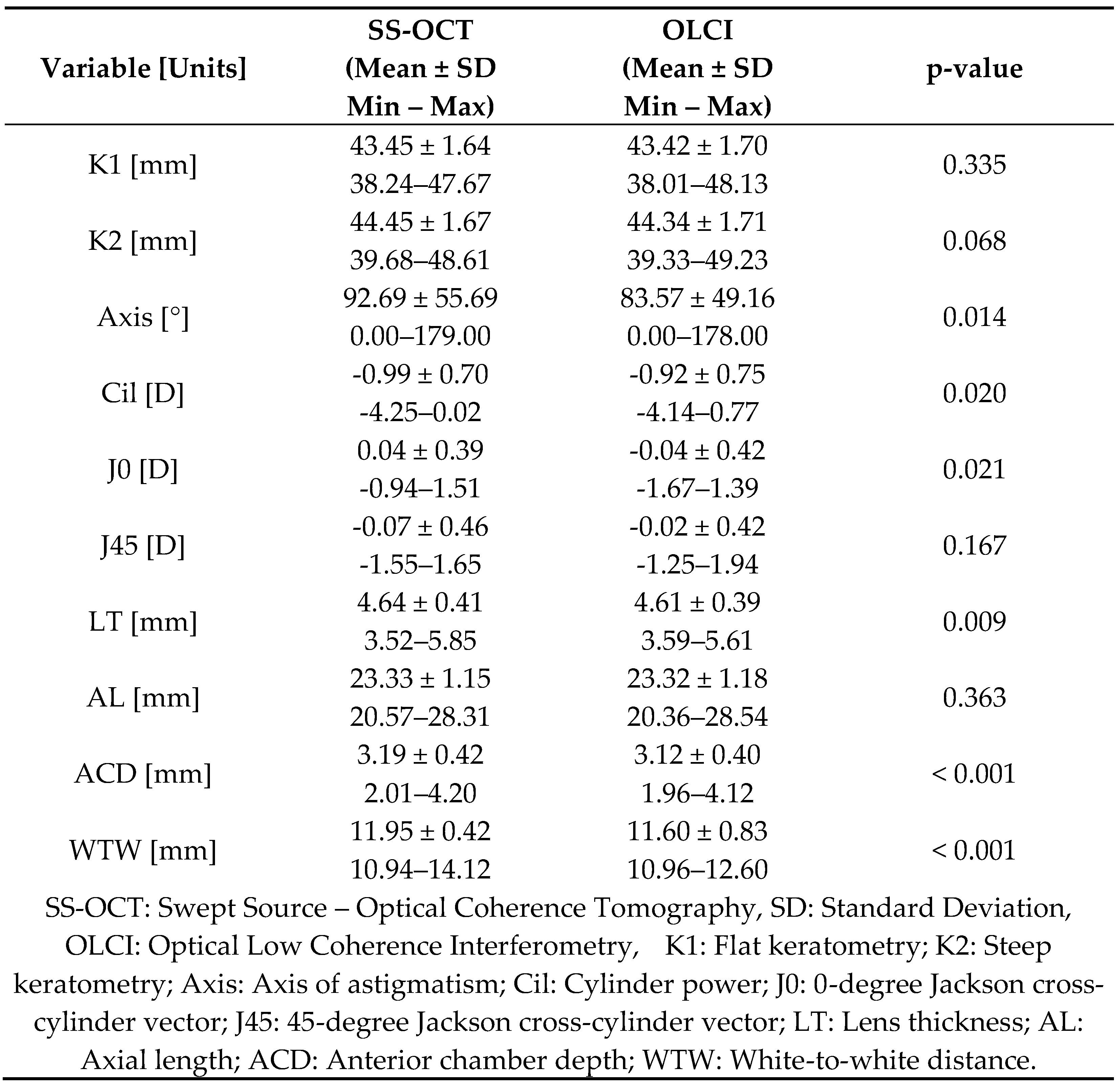

Table 1 presents a detailed comparison of biometric measurements between the SS-OCT and OLCI. The results demonstrate high consistency between the two modalities, with significant differences observed in certain variables.

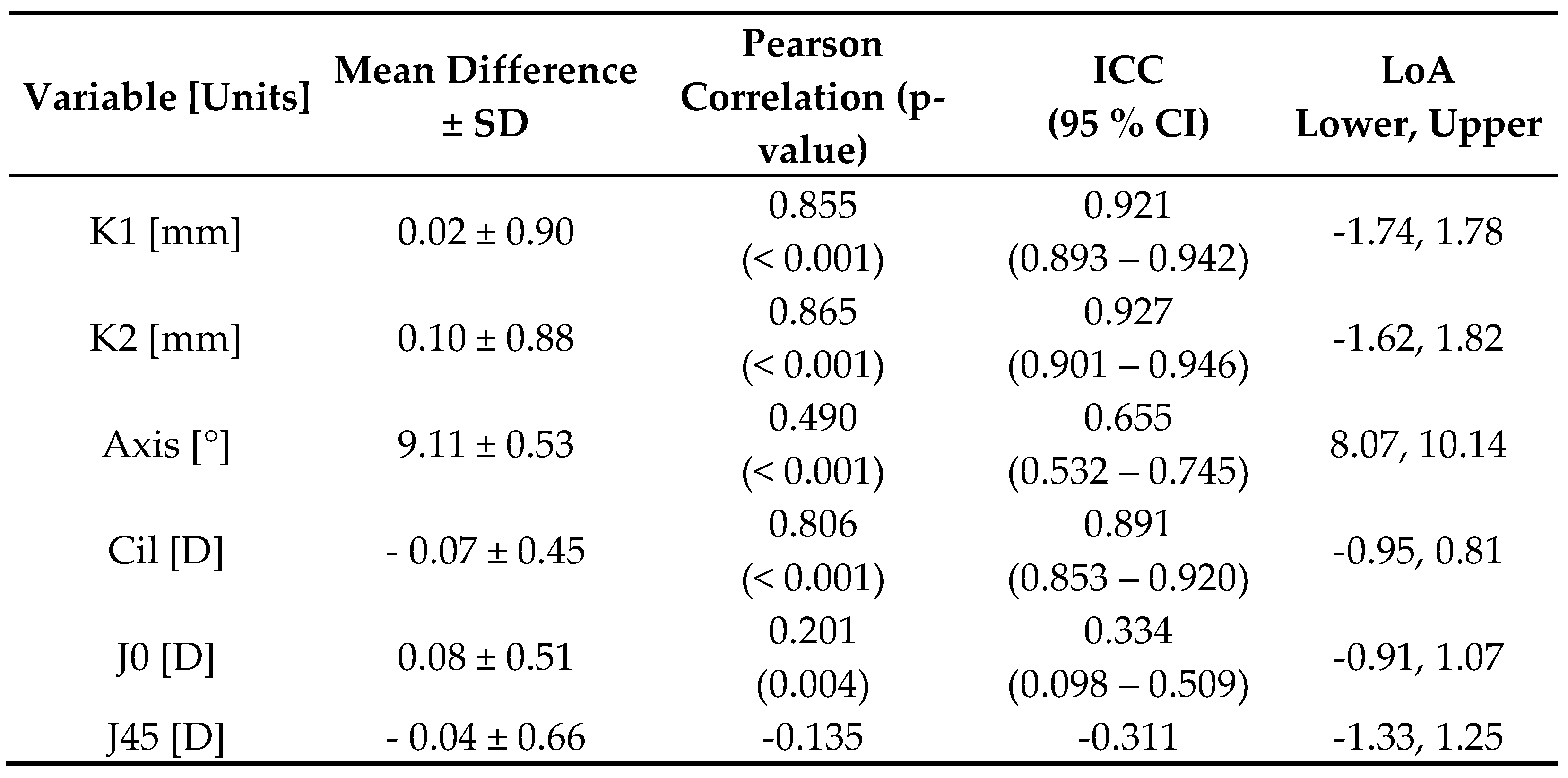

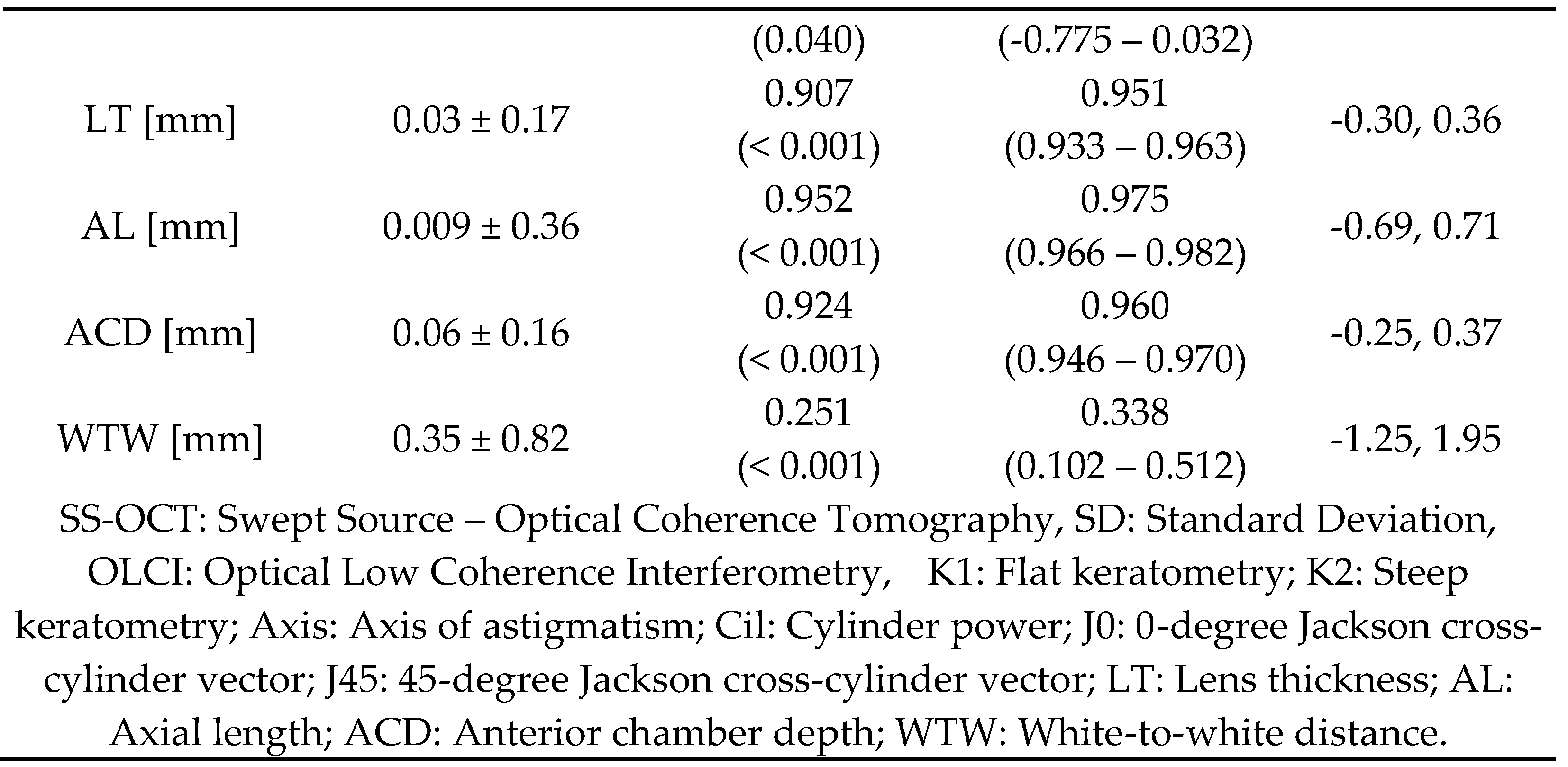

Table 2 summarizes the agreement analysis between SS-OCT and OLCI biometers. The mean differences for most variables were minimal, indicating close agreement. The results indicate a strong agreement between SS-OCT and OLCI for most variables, particularly in axial and keratometry measurements, but highlight certain discrepancies in astigmatism-related parameters and WTW measurements.

Figure 1 illustrates Bland-Altman plots comparing the agreement between SS-OCT and OLCI biometers for various parameters. Each subplot represents the mean differences between the devices plotted against their averages, with the solid green line indicating the mean difference and the dashed red lines representing the limits of agreement (LoA). Flat keratometry shows minimal mean differences, with most data points lying within the LoA (-1.74 to 1.78 mm), indicating strong agreement between devices. Steep keratometry also exhibits a similar pattern, with narrow LoA (-1.62 to 1.82 mm) and data closely clustering around the mean difference. LT shows excellent agreement, with a mean difference near zero and narrow LoA (-0.30 to 0.36 mm), confirming high consistency. AL reveals tight clustering around the mean difference, with most values within the LoA (-0.69 to 0.71 mm), indicating robust agreement. ACD displays narrow LoA (-0.25 to 0.37 mm) and a minimal mean difference, emphasizing strong reliability. WTW shows broader variability, with LoA ranging from -1.25 to 1.95 mm, reflecting lower agreement compared to other parameters.

Figure 2 presents the double-angle astigmatism plots for comparing astigmatic components between the SS-OCT and OLCI. These polar plots provide a visual representation of the magnitude and axis of astigmatism, with each data point corresponding to an eye's astigmatic value. The double-angle plots highlight strong agreement between SS-OCT and OLCI for astigmatic measurements, as both datasets show comparable centroids and mean absolute astigmatism. However, OLCI exhibits a slightly larger variability, as evidenced by the broader 95% confidence ellipse. These findings suggest that while both devices provide reliable astigmatism data, SS-OCT might offer slightly more precision in capturing astigmatic components.

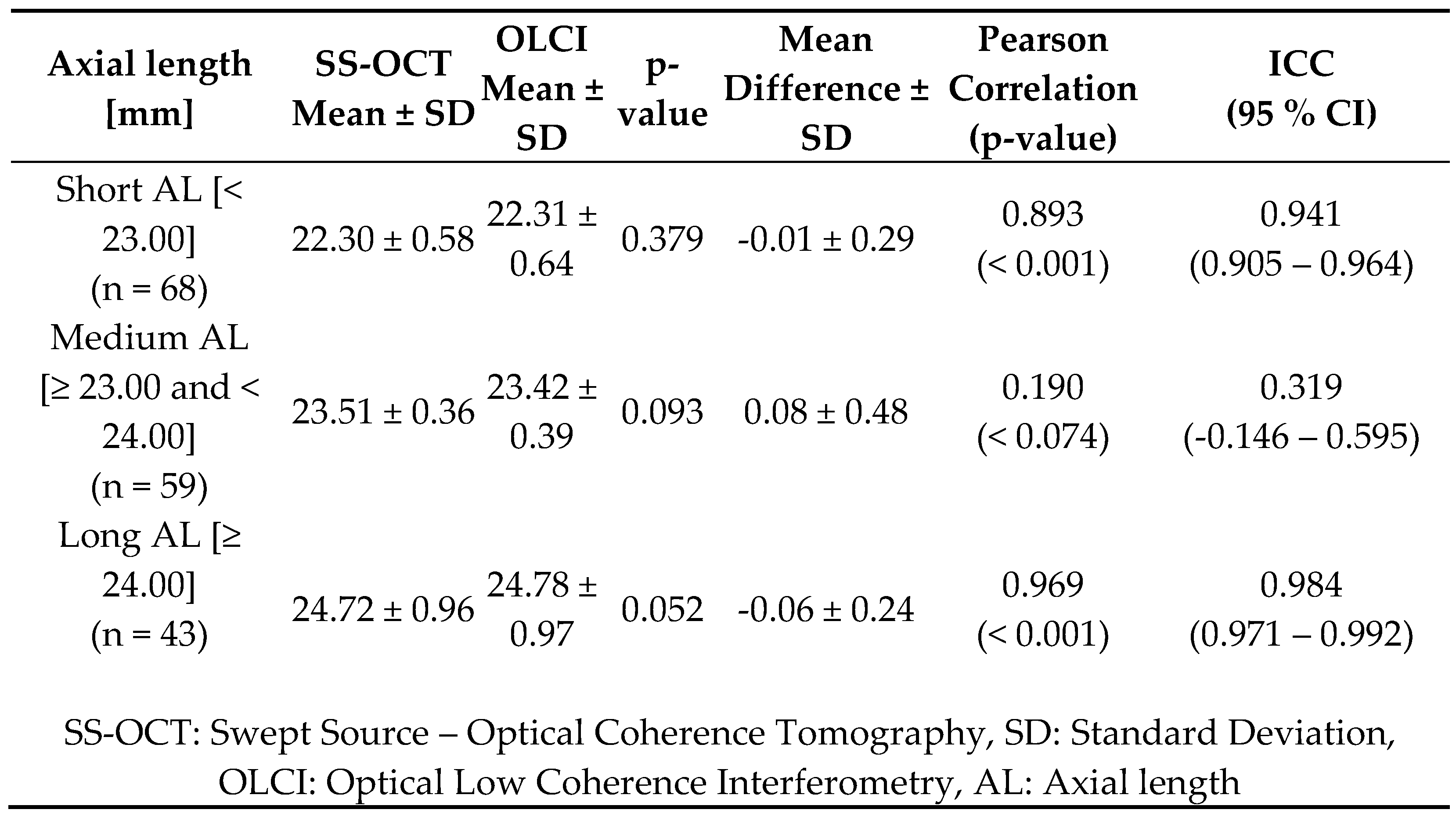

Table 3 provides a detailed analysis of A) measurements across three groups—short eyes (< 23.00 mm), medium eyes (≥23.00 and <24.00 mm), and long eyes (≥24.00 mm)—comparing data obtained from SS-OCT and OLCI. The results highlight strong agreement between SS-OCT and OLCI for AL measurements in short and long eyes, evidenced by high Pearson correlations and ICC values above 0.940. The agreement is particularly robust in long eyes, where the ICC reaches 0.984. In contrast, medium eyes show lower agreement, with a weak correlation and an ICC of 0.319, possibly due to greater variability in this group.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate a strong overall agreement between SS-OCT and OLCI for biometric measurements. Key parameters such as flat and steep keratometry, AL, LT, ACD exhibited minimal mean differences, high Pearson correlations, and excellent ICC, confirming the reliability of both devices. However, discrepancies were noted in astigmatism-related parameters, including the axis of astigmatism, cylinder power, and Jackson cross-cylinder components, where agreement was moderate to low. Additionally, WTW showed broader limits of agreement and lower ICC values. Subgroup analysis of AL revealed robust agreement for short and long eyes, with reduced consistency in medium eyes. These findings highlight the comparability of SS-OCT and OLCI in most biometric measurements, while also identifying specific areas where differences may influence clinical decision-making.

Axial Length

The current study demonstrated excellent agreement in AL measurements between SS-OCT and OLCI devices, with a mean difference of 0.009 mm (SD ± 0.36) and an ICC of 0.975. These results align with findings from Hoffer et al.[

9], who observed negligible differences in AL measurements between the IOLMaster 700 and Lenstar LS 900, with ICCs >0.99. Similarly, Gao et al.[

2] reported strong agreement with Bland-Altman limits of agreement within ±0.05 mm to ±0.07 mm, reinforcing the high precision of these technologies. However, subgroup analysis in this study highlighted minor discrepancies in medium and long eyes, which were less frequently discussed in prior literature.

Anterior Chamber Depth

This study observed a small but statistically significant difference in ACD measurements, with SS-OCT consistently measuring deeper values (mean difference 0.06 mm, SD ± 0.16, ICC = 0.960). This finding echoes the results of Kurian et al.[

11] and Hoffer et al.[

9], who both reported deeper ACD measurements with SS-OCT compared to OLCR, though the differences remained clinically insignificant. The ability of SS-OCT to penetrate dense media may partly explain these differences, as noted by Kanclerz et al.[

19].

Lens Thickness

Agreement in LT measurements between the two devices was excellent, with a mean difference of 0.03 mm (SD ± 0.17) and ICC of 0.951. This is consistent with findings from Yu et al. [

12] and Kunert et al. [

5], who also observed high concordance in LT values between SS-OCT and OLCR / OLCI devices. These findings reinforce the reliability of both technologies for preoperative evaluations where precise LT measurements are critical.

Keratometry and Astigmatism

Keratometry values (flat K1 and steep K2) displayed high levels of agreement, with ICC values of 0.921 and 0.927, respectively, and mean differences of 0.02 mm (K1) and 0.10 mm (K2). These results are comparable to those of Gao et al. [

2], who demonstrated similar agreement between SS-OCT and OLCR / OLCI devices, with ICCs >0.98 for all keratometric parameters

Astigmatism vectors (J0 and J45) exhibited variable agreement, with J0 showing moderate agreement (ICC = 0.334) and J45 displaying lower reliability (ICC = -0.311). This variability may be attributed to differences in the algorithmic processing of astigmatism data between devices, as also noted in studies by Zharei Ghanavati et al.[

10] and Passi et al.[

13]. Employing double-angle vector representation to analyze differences in astigmatism measurements could provide a more nuanced understanding of the observed variability and improve comparative analysis between devices.

White-to-White

WTW measurements showed notable differences, with SS-OCT measuring larger values (mean difference 0.35 mm, SD ± 0.82, ICC = 0.338). El Chebab et al.[

6] also reported differences in WTW between these devices but attributed them to variations in measurement algorithms and device design. Yu et al.[

12] similarly observed discrepancies in WTW, emphasizing the need for device-specific calibration in clinical practice.

Kanclerz et al.[

19] and Macalinden et al. [

20] emphasized the superior penetration and lower dropout rates of SS-OCT devices compared to OLCR / OLCI, particularly in dense cataracts. These advantages, combined with the robust agreement in key parameters such as AL, ACD, and keratometry, make SS-OCT a versatile choice for clinical settings. However, the discrepancies observed in WTW, and astigmatism vectors highlight areas where further standardization and cross-device calibration may be necessary.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size, while sufficient for detecting differences in most biometric parameters, may limit the generalizability of findings, particularly for subgroup analyses of medium axial lengths. Second, the study focused exclusively on a single population demographic, which may not fully capture variability in biometric measurements across different ethnicities, ages, or refractive statuses. Third, potential inter-operator variability in measurement acquisition was not assessed, which could influence the agreement between devices. Additionally, while SS-OCT and OLCI were compared directly, the study did not evaluate their performance against a gold standard reference method. Moreover, the study did not analyze the potential effect of device-specific artifacts or noise on the measurements, which could play a role in the observed discrepancies.

4.2. Future lines of research

Future research should explore the integration of SS-OCT and OLCI data through advanced computational methods, such as artificial intelligence or machine learning algorithms, to enhance the precision of biometric measurements. Longitudinal studies could assess how these devices perform over time in tracking progressive conditions, such as keratoconus or cataract development, to determine their reliability in dynamic clinical scenarios. Expanding the scope to include pediatric populations and highly ametropic eyes would provide valuable insights into the versatility of these technologies across a broader range of clinical settings. Lastly, further studies could focus on optimizing device calibration protocols to minimize variability and improve cross-device standardization in clinical practice.

4.3. Clinical application

The results of this study underline the practical utility of both SS-OCT and OLCI in clinical settings, particularly in preoperative planning for refractive and cataract surgery. The high agreement observed in key parameters, such as AL, keratometry, and LT, supports the interchangeable use of these devices in routine biometric assessments, ensuring reliable data for IOL power calculations. The robust performance in short and long eyes highlights their suitability for a wide range of refractive conditions, while the strong precision in ACD measurements underscores their relevance in surgical planning for anterior segment procedures.

However, the moderate agreement in astigmatism-related parameters suggests that clinicians should carefully evaluate astigmatic data, particularly the axis and cylinder power, when using these devices interchangeably. Additionally, the variability observed in WTW measurements calls for caution in applications requiring precise corneal sizing, such as phakic IOL implantation.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the high comparability between SS-OCT and OLCI for most biometric measurements, establishing both as reliable tools for clinical and surgical planning. Key parameters such as axial length, lens thickness, and keratometry exhibited excellent agreement, supporting their interchangeability in routine practice. However, moderate discrepancies in astigmatism-related parameters and white-to-white distance underscore the need for caution when using these devices for specific refractive and surgical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; methodology, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; validation, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; formal analysis, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; investigation, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; resources, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; data curation, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; writing—original draft preparation, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; writing—review and editing, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; visualization, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; supervision, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; project administration, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S; funding acquisition, L.A-B, N.M, Y.I-I, M.M and H-T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical review and approval were waived by the Institutional Ethics Committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study through the standard refractive surgery consent form, which included permission for the use of anonymized data in research.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Victor Babes University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara for their support in partially covering the costs of publication for this research paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACD |

Anterior Chamber Depth |

| AL |

Axial Length |

| CDVA |

Corrected Distance Visual Acuity |

| D |

Diopters |

| IOL |

Intraocular Lens |

| logMAR |

Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution |

| K1 |

Flat Keratometry |

| K2 |

Steep Keratometry |

| LT |

Lens Thickness |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| MedAE |

Median Absolute Error |

| ME |

Mean Error |

| OLCI |

Optical Low Coherence Interferometry |

| OLCR |

Optical Low Coherence Reflectometry |

| SE |

Spherical Equivalent |

| SS-OCT |

Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography |

| UDVA |

Uncorrected Distance Visual Acuity |

| WTW |

White-to-White Corneal Diameter |

References

- Arriola-Villalobos, P.; Almendral-Gómez, J.; Garzón, N.; Ruiz-Medrano, J.; Fernández-Pérez, C.; Martínez-de-la-Casa, J.M.; Díaz-Valle, D. Agreement and Clinical Comparison between a New Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography-Based Optical Biometer and an Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry Biometer. Eye 2017, 31, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Chen, H.; Savini, G.; Miao, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J. Comparison of Ocular Biometric Measurements between a New Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography and a Common Optical Low Coherence Reflectometry. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, G.; Modis, L.J. Ocular Measurements of a Swept-Source Biometer: Repeatability Data and Comparison with an Optical Low-Coherence Interferometry Biometer. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2019, 45, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo-Sanz, J.A.; Portero-Benito, A.; Arias-Puente, A. Efficiency and Measurements Agreement between Swept-Source OCT and Low-Coherence Interferometry Biometry Systems. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 256, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunert, K.S.; Peter, M.; Blum, M.; Haigis, W.; Sekundo, W.; Schütze, J.; Büehren, T. Repeatability and Agreement in Optical Biometry of a New Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography–Based Biometer versus Partial Coherence Interferometry and Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2016, 42, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Chehab, H.; Agard, E.; Dot, C. Comparison of Two Biometers: A Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography and an Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry Biometer. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 29, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shammas, H.J.; Ortiz, S.; Shammas, M.C.; Kim, S.H.; Chong, C. Biometry Measurements Using a New Large-Coherence-Length Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomographer. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2016, 42, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Cheng, H.; Wu, M. Association of Refractive Outcome with Postoperative Anterior Chamber Depth Measured with 3 Optical Biometers. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffer, K.J.; Hoffmann, P.C.; Savini, G. Comparison of a New Optical Biometer Using Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography and a Biometer Using Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2016, 42, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarei-Ghanavati, S.; Nikpayam, M.; Namdari, M.; Bakhtiari, E.; Hassanzadeh, S.; Ziaei, M. Agreement between a Spectral-Domain Ocular Coherence Tomography Biometer with a Swept-Source Ocular Coherence Tomography Biometer and an Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry Biometer in Eyes with Cataract. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2023, 35, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurian, M.; Negalur, N.; Das, S.; Puttaiah, N.K.; Haria, D.; J, T.S.; Thakkar, M.M. Biometry with a New Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Biometer: Repeatability and Agreement with an Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry Device. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2016, 42, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhao, G.; Lei, C.S.; Wan, T.; Ning, R.; Xing, W.; Ma, X.; Pan, H.; Savini, G.; Schiano-Lomoriello, D.; et al. Repeatability and Reproducibility of a New Fully Automatic Measurement Optical Low Coherence Reflectometry Biometer and Agreement with Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography-Based Biometer. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 108, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passi, S.F.; Thompson, A.C.; Gupta, P.K. Comparison of Agreement and Efficiency of a Swept Source-Optical Coherence Tomography Device and an Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry Device for Biometry Measurements during Cataract Evaluation. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2018, Volume 12, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Vicent, A.; Venkataraman, A.P.; Dalin, A.; Brautaset, R.; Montés-Micó, R. Repeatability of a Fully Automated Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Biometer and Agreement with a Low Coherence Reflectometry Biometer. Eye Vis. 2023, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, W.; Ong, A.; Zheng, B.; Liang, Z.; Cui, D. Comparative Analysis of a Novel Spectral-Domain OCT Biometer versus Swept-Source OCT or OLCR Biometer in Healthy Pediatric Ocular Biometry. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montés-Micó, R. Evaluation of 6 Biometers Based on Different Optical Technologies. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2022, 48, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fişuş, A.D.; Hirnschall, N.D.; Ruiss, M.; Pilwachs, C.; Georgiev, S.; Findl, O. Repeatability of 2 Swept-Source OCT Biometers and 1 Optical Low-Coherence Reflectometry Biometer. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2021, 47, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanclerz, P.; Bazylczyk, N.; Radomski, S.A. Tear Film Stability in Patients with Symptoms of Dry Eye after Instillation of Dual Polymer Hydroxypropyl Guar/Sodium Hyaluronate vs Single Polymer Sodium Hyaluronate. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanclerz, P.; Hecht, I.; Tuuminen, R. Technical Failure Rates for Biometry between Swept-Source and Older-Generation Optical Coherence Methods: A Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlinden, C.; Wang, Q.; Gao, R.; Zhao, W.; Yu, A.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Huang, J. Axial Length Measurement Failure Rates With Biometers Using Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Compared to Partial-Coherence Interferometry and Optical Low-Coherence Interferometry. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 173, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).