1. Introduction

Mating induces physiological changes in the female reproductive tract that regulate reproductive function. Mating components independent of sperm, such as sensorial stimulation of the vaginocervical area and seminal plasma, modify the physiology of reproductive organs at various distances from the site of insemination. Recently, we reported that mating induces an early transcriptional response in the oviductal mucosa of rats [

1], and we revealed that the signals that partially regulate this transcriptional response include tumor necrosis factor and retinoic acid. The cohort of mating-related genes was involved mainly in cell-to-cell signaling and interactions; thus, in the present study, we described the role of one of these genes,

carbohydrate sulfotransferase 10 (

Chst10).

Chst10 is upregulated in the oviductal mucosa of rats 3 h after mating [

1]. This gene encodes a sulfotransferase that participates in the synthesis of the human natural killer-1 (HNK-1) carbohydrate moiety, which is associated with membrane lipids and proteins and mediates interactions among cells in both the immune system and nervous system [

2,

3,

4]. CHST10 is located in the Golgi apparatus, and in addition to its involvement in the synthesis of HNK-1 glycoproteins, it also participates in the generation of part-time proteoglycans [

5]. Therefore, this sulfotransferase could modify the expression patterns of HNK-1 glycoproteins and/or proteoglycans that must be exposed on the epithelial membrane and/or secreted into the oviductal lumen. Indeed, high Golgi apparatus activity and high sulfated glycoprotein secretion have been reported in response to mating in sheep and rabbits, respectively [

6,

7].

On the other hand, CHST10 is also involved in estrogen metabolism because it actively sulfates glucuronidated estradiol (E

2). CHST10 deficiency leads to high levels of E

2 in the serum, uterine hypertrophy, and infertility in mice [

8]. In our rat model, mating changes not only the mechanism by which E

2 accelerates oviductal egg transport but also the sensitivity to E

2. Indeed, accelerating oviductal egg transport in mated rats requires a dose of E

2 that is 10 times greater than that needed in unmated rats (10 µg/rat and 1 µg/rat, respectively) [

9]. Therefore, exploring the specific processes regulated by CHST10 in oviductal physiology early after mating is imperative.

To achieve our objective, we measured the protein levels and activity of CHST10 in the oviductal mucosa, determined the localization of HNK-1 carbohydrate moieties in the oviduct, identified the HNK-1 glycoproteins present in the oviductal mucosa and determined their oviductal localization. Finally, we identified the component of mating that regulates the expression of Chst10 in the oviductal mucosa.

3. Discussion

Previously, we reported that mating induces an early transcriptional response in the oviductal mucosa of rats, suggesting that the oviduct can organize a physiological response to sustain the events that occur in the oviduct early after mating. Here, we report one of those physiological responses.

Glycoconjugates in the female reproductive tract are critical for controlling sperm maturation, sperm transport and gamete interactions [

11,

12,

13]. Thus, it is interesting that mating increases the transcriptional activity of

Chst10, a gene encoding a carbohydrate sulfotransferase that participates in the synthesis of the particular carbohydrate moiety HNK-1. The structure of the HNK-1 moiety in glycoproteins and glycolipids is unique and consists of a sulfated trisaccharide with the sequence SO

4-3GlcAb1-3Galb1-4GlcNAc–R [

14]. This moiety mediates interactions among cells in the nervous system and immune system [

2,

3,

4], and here, we report that it could mediate cell interactions in the reproductive system.

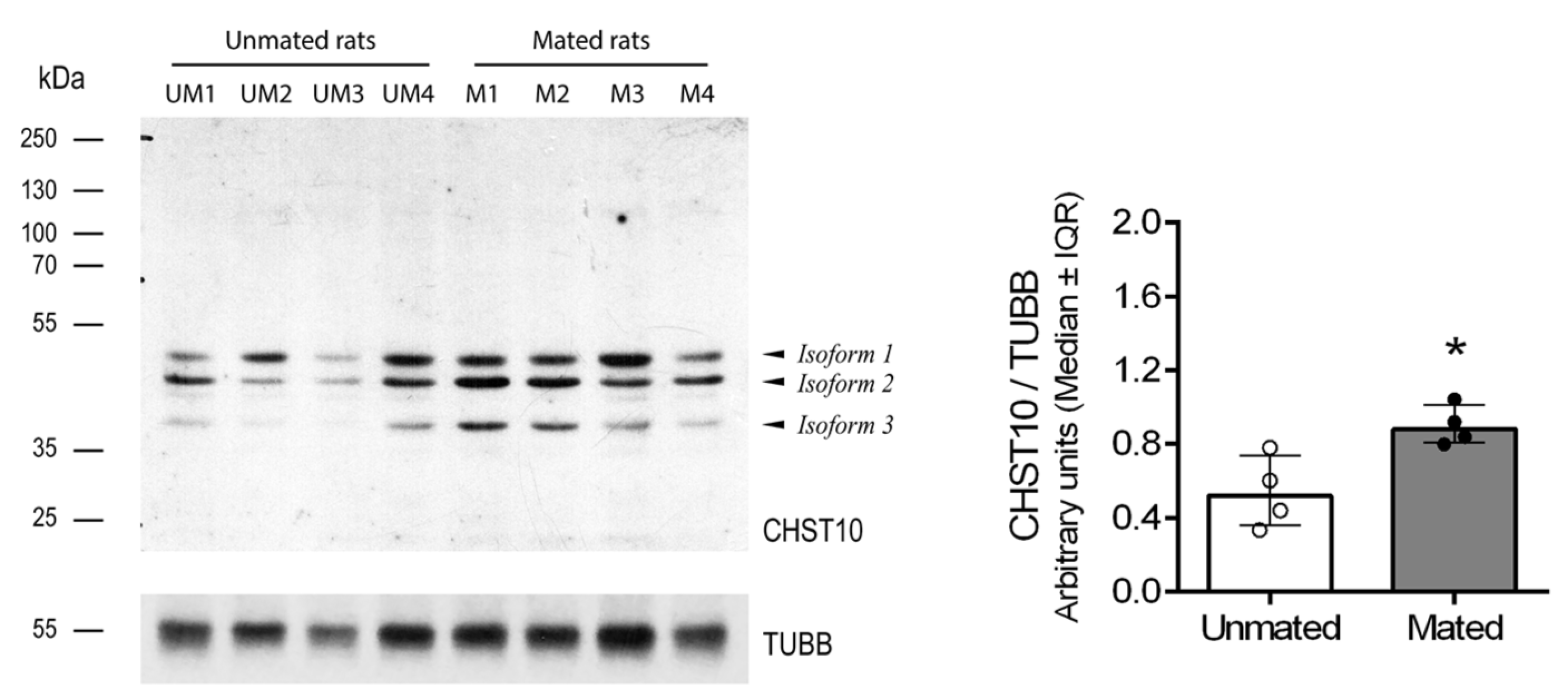

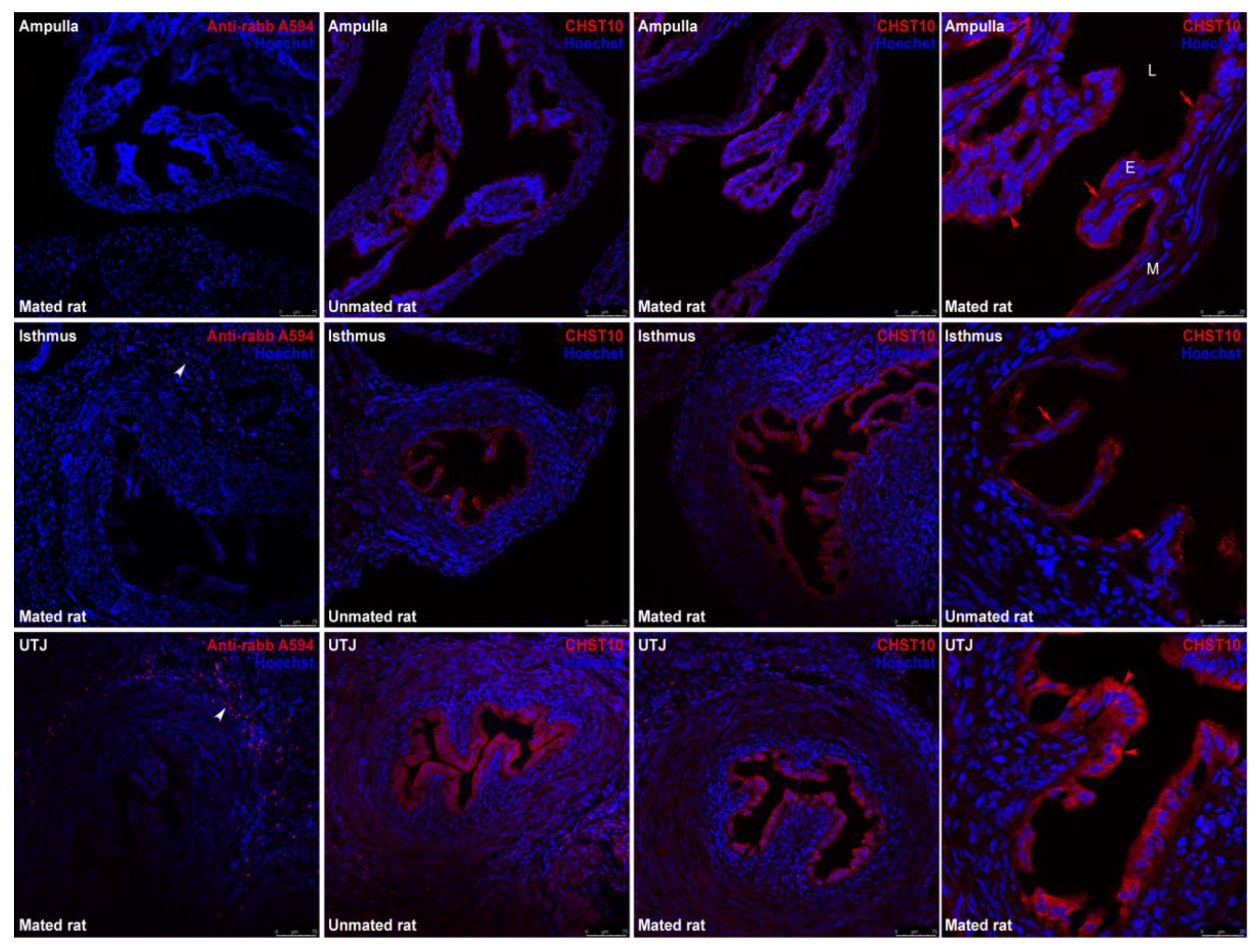

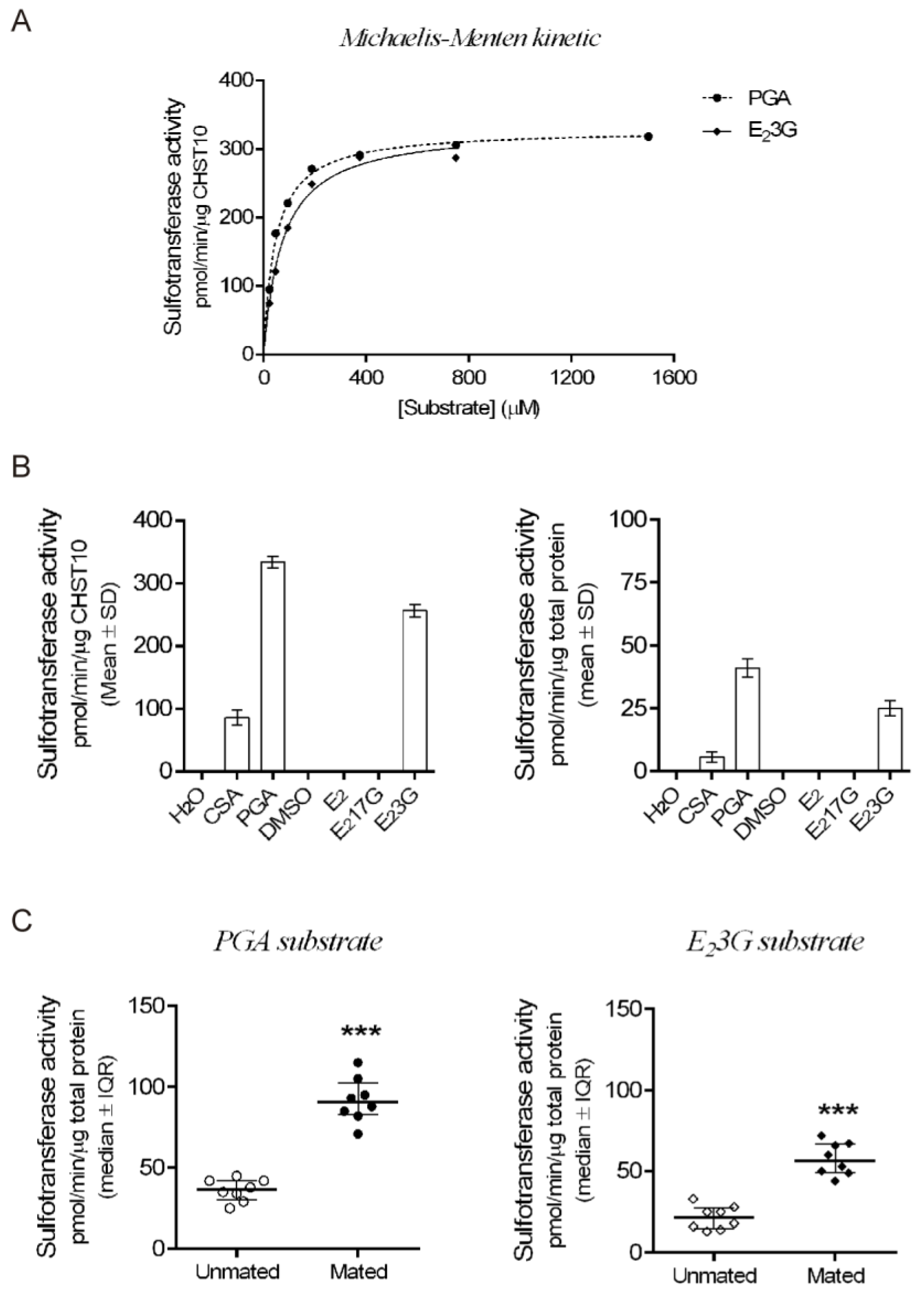

Our results show that mating increases the activity of CHST10 and induces the synthesis of novel HNK-1 glycoproteins, which were identified as ALDH9A1, ALDOA and FHL-1, in the oviductal mucosa. Three isoforms of CHST10 can be found in this tissue with molecular masses ranging from 40 to 50 kDa. These bands correspond to CHST10 isoforms proposed to be expressed in rats (see the Rat Genome Databank:

https://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/report/gene/main.html?id=621216). Indeed, the sequence of the human antigen used to raise the antibody (

Figure S1) has 81, 81 and 85% amino acid (aa) residue identity with CHST10 isoforms X1 (374 aas), X2 (356 aas) and X3 (288 aas), respectively (

Figure S2a-c) [

15,

16,

17]. The putative location of this sulfotransferase is the Golgi apparatus, and we detected signals suggesting this location, especially in the UTJ; however, we also detected CHST10 in the epithelium cytoplasm in all oviductal regions and in the muscular layer in the UTJ. Since estrogen sulfotransferases, such as Sult1E1, are located in the cytosol [

18], we propose that cytosolic CHST10 could participate in estrogen metabolism in the oviductal mucosa. Indeed, in addition to its 3´-PAPS binding domain, CHST10 also contains a 5´-PAPS binding domain, which is characteristic of cytosolic sulfotransferases [

18]. Moreover, we measured the specific sulfotransferase activity with glucuronidated estradiol (E

23G) in the oviductal mucosa. Therefore, we propose that in the oviductal mucosa, CHST10 participates not only in the synthesis of HNK-1 glycoproteins but also in estrogen metabolism. On the other hand, since we cannot discriminate which isoform exists in a particular subcellular location, we used the sum of the intensities of all the isoforms detected in each sample to compare CHST10 protein levels between unmated and mated rats. Thus, we found that mating increases the protein levels of CHST10 in the oviductal mucosa, which correlates with the measured increase in sulfotransferase activity when two specific acceptor substrates, PGA and E

23G, were used. Although we cannot test whether the sulfotransferase activity measured in the oviductal mucosa is exclusive to CHST10 due to a lack of specific inhibitors, we concluded that mating increases the activity of CHST10 in the oviductal mucosa, as supported by the following: i) activity measurements with specific acceptor substrates; ii) a pattern of acceptor substrate preferences that is similar to that of human recombinant CHST10; and iii) the endogenous production of its specific product, the HNK-1 carbohydrate moiety.

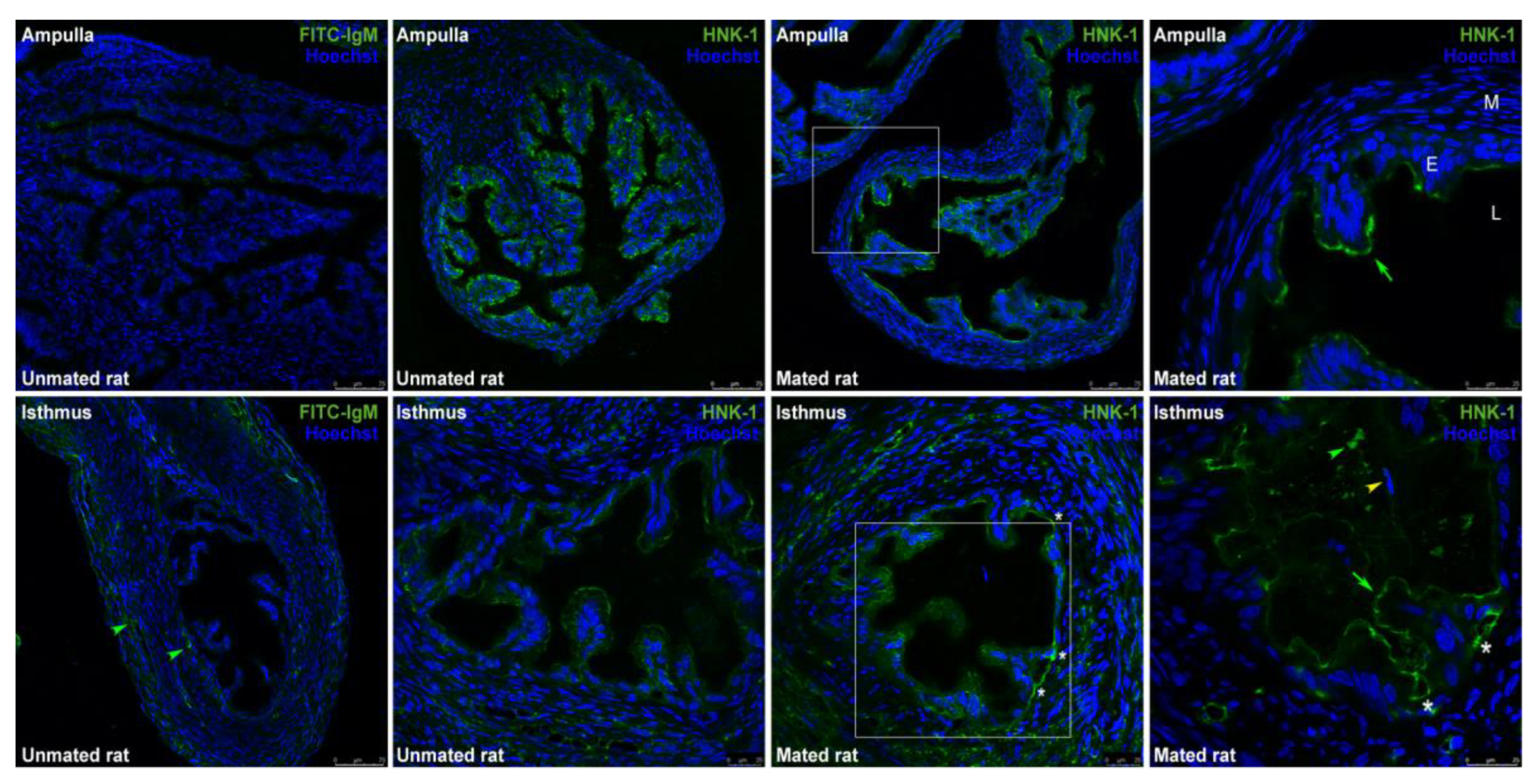

Compared with the isthmus and UTJ, the HNK-1 moiety is more abundant in the ampulla and is located predominantly on the luminal face of the oviductal epithelium. There was an unexpected diversity of HNK-1 glycoproteins in the oviductal mucosa, with clear differences in the molecular masses of the

cellular pool (higher than 70 kDa) and the

secreted pool (lower than 100 kDa) of glycoproteins (

Figure 5). These results support the separation of glycoproteins into

cellular and

secreted pools by simple centrifugation after mechanical isolation of the oviductal mucosa and before lysis of its cellular components. However, in the

secreted pool of glycoproteins, we cannot exclude the presence of some serum and/or cytosolic proteins released after the cells are damaged upon oviductal mucosal mechanical isolation. Our 2D analysis increased the power of HNK-1 glycoprotein detection. There were at least 15 HNK-1-positive

spots with different intensities between the samples of unmated and mated rats, among which 5 were identified.

Spots 2 and 3 were identified as ALDH9A1, as they have the same molecular mass but different isoelectric points. Although both are HNK-1 glycosylated proteins,

spot 2 is more acidic than

spot 3; therefore,

spot 2 is the more densely glycosylated variant. Additionally, the protein

cores of

spots 2 and 3 were detected in samples from mated rats only (

Figure 7, lower panel). Consequently, mating induces the

de novo synthesis of HNK-1-ALDH9A1 isoelectric variants in the oviductal mucosa, and the presence of acidic variants could very well be correlated with the increased activity of CHST10. We found similar results for

spots 5 and 6, which were identified as FHL1. In this case, mating induces the

de novo synthesis of the more acidic variant of FHL1 since

spot 5 was detected only in samples from mated rats, whereas

spot 6 was detected in both the mated and unmated samples. Therefore, mating induces the synthesis of acidic variants of specific HNK-1 glycoproteins in the oviductal mucosa. This conclusion could also be applied to ALDOA, although we only detected this protein in

spot 4; however, we propose that

spot A and

spot B are acidic variants of ALDOA (

Figure 6). We did not identify

spots A or B because these

spots were not well resolved in the Coomassie blue-stained gels; that is, other

spots were too close, as observed in the silver-stained membranes used for western blotting (

Figure 7). More importantly, contrary to our expectations, we cannot validate our initial interpretation of

spot 4 from 2D analysis; that is, mating decreased its intensity (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Indeed, further western blot analyses revealed that mating increased ALDOA levels (

spot 4) in the oviductal mucosa (

Figure 8B). This contradiction could be explained by the fact that

spots A and B are acidic variants of ALDOA; indeed,

spots A, B and 4 have the same molecular mass, and

spots A and B are located to the left of

spot 4 (toward the acidic region). Furthermore,

spot A was induced, and

spot B was increased in mated samples (

Figure 6 and 7), which correlates well with the increased levels of ALDOA in the oviductal mucosa of mated rats. However, this hypothesis must be elucidated in future work. Overall, we conclude that mating increases the activity of CHST10 in the oviductal mucosa to induce the synthesis of acidic variants of ALDH9A1 and FHL1 via HNK-1 glycosylation.

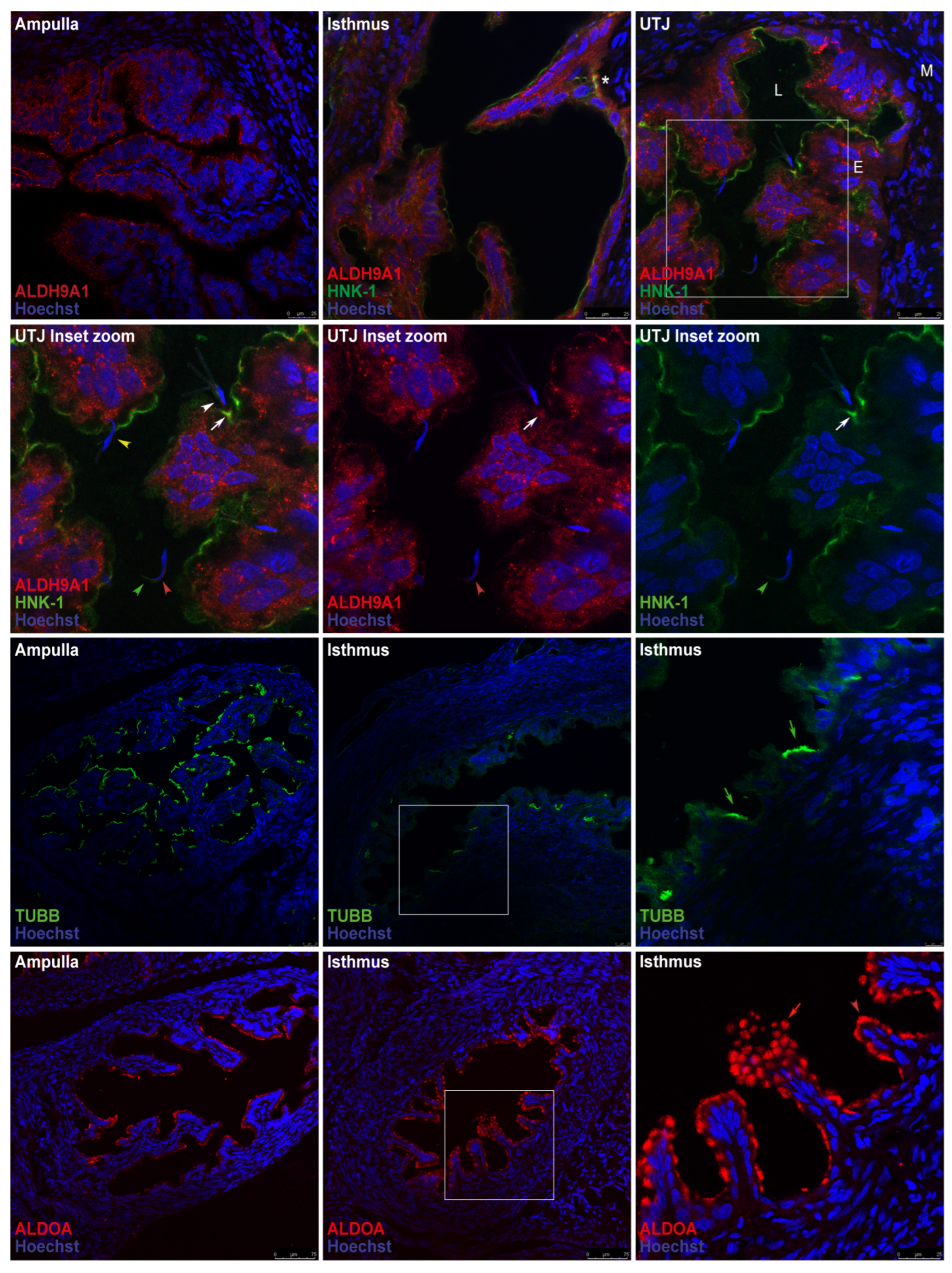

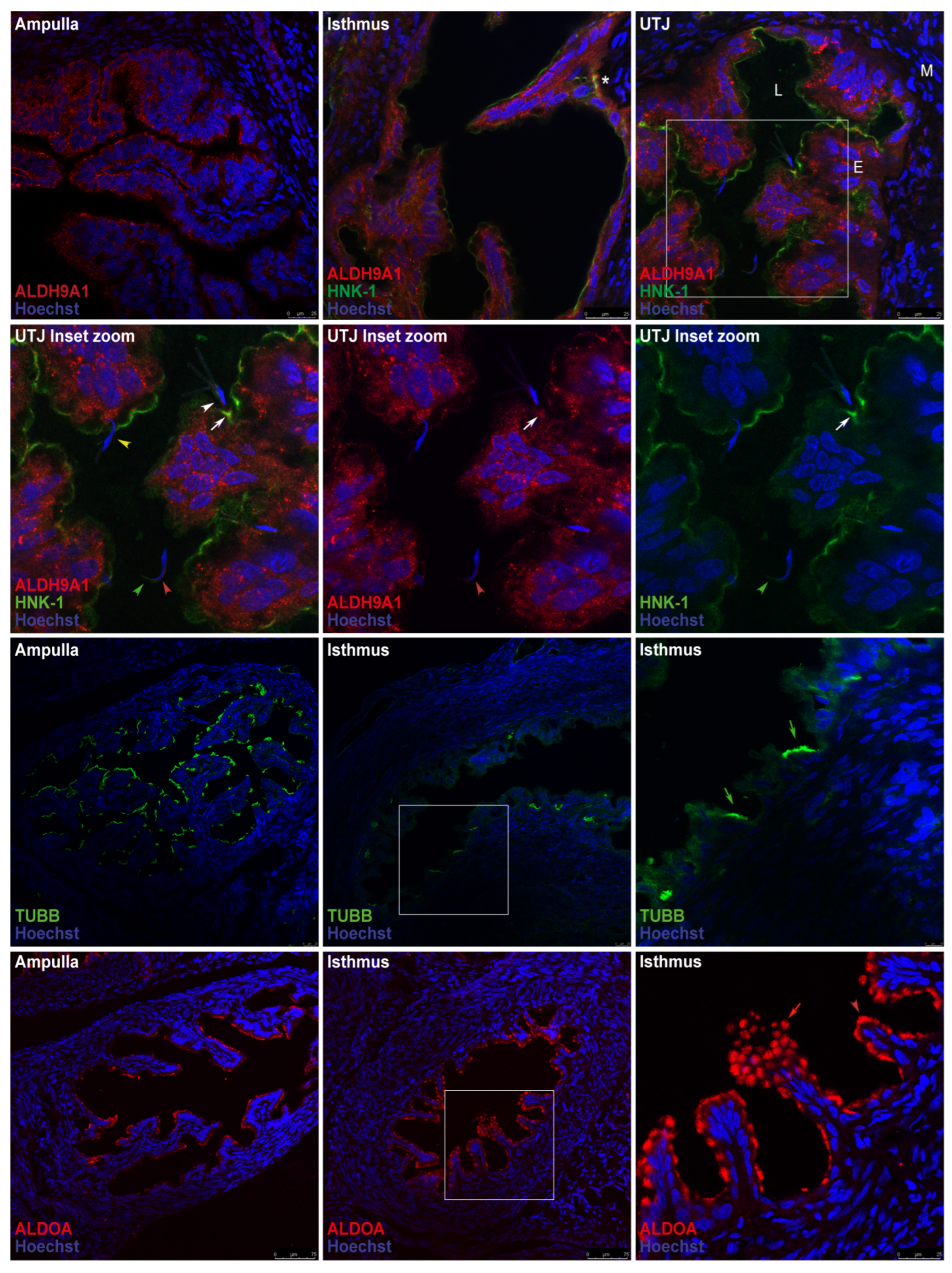

We propose that mating induces the

de novo secretion of ALDH9A1 from oviductal epithelium. Our results revealed that ALDH9A1 was not present in the oviductal mucosa

secreted pool from unmated rats (except for one sample), but after mating, this glycoprotein was detected (

Figure 8A). Similar results were detected by staining the 2D western blot membrane with silver (

Figure 7), as we did not detect an ALDH9A1 protein

core (

spots 2 and 3) in the unmated rat sample. ALDH9A1 is located predominantly on the luminal face of the epithelium in the ampulla, but it is found in the cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vesicles in the isthmus and UTJ. Interestingly, HNK-1-ALDH9A1 represents a minor fraction of the total ALDH9A1 synthesized in the oviductal mucosa of the isthmus and UTJ since the majority of this protein was shown to not colocalize with the HNK-1 signal via immunofluorescence (

Figure 9, first row). Colocalization of the HNK-1 and ALDH9A1 signals was detected in particular regions of the isthmus (

Figure 9, first row, asterisk), specifically in the trenches created by the mucosal folds, which could be related to the ciliated cell clusters that are also found in these trenches, creating a striped pattern of ciliated cell clusters in the isthmus (

Figure 9, third row, green arrows), as observed in mice [

19]. This striped pattern is similar to the pattern of sperm distribution in the isthmus shown in previous elegant studies in mice [

20,

21,

22]. Furthermore, we previously reported that sialic acid moieties, which have a particular distribution similar to that of HNK-1-ALDH9A1 in the isthmus, are involved in sperm‒oviduct interactions in rats; these interactions occur between sialoglycoconjugates in epithelial cells and sialic acid-binding proteins on the sperm surface

in vivo [

23]. Therefore, we propose that HNK-1-ALDH9A1 could be another sperm binding site in the rat oviductal mucosa and that sialoglycoconjugates and HNK-1-ALDH9A1 could guide the sperm since they bind intermittently to particular regions of the isthmus during its journey to the fertilization site [

24,

25]. On the other hand, in the UTJ, we detected the specific colocalization of HNK-1 and ALDH9A1, but in this case, their colocalization appeared in a mucosa fold that were in close contact with acrosome-reacted sperm (

Figure 9, second row, white arrows and white arrowhead, respectively). We propose that the regions with HNK-1-ALDH9A1 in the UTJ could be involved in the sperm quality control machinery proposed to exist in the oviduct [

26] because in those regions, the sperm was induced to undergo the acrosome reaction prematurely, and consequently, its survival was compromised. In support of this proposal, we detected acrosome-intact sperm interacting with the mucosal folds in a region where the HNK-1 and ALDH9A1 signals did not colocalize (

Figure 9, second row, yellow arrowhead).

The ALDH9 family encodes enzymes involved in the metabolism of 4-aminobutyraldehyde (ABAL) and amino aldehydes derived from polyamines and choline [

27]. ALDH9A1 catalyzes the irreversible NAD(P)-dependent oxidation of aliphatic or aromatic aldehydes, was first purified from the liver and was characterized as an ABAL dehydrogenase that forms γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [

28], a well-known neurotransmitter; however, GABA is also an inducer of the acrosome reaction in the sperm of many species

in vitro [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Interestingly, the abundance of GABA in the rat oviduct is 2.5 times greater than that in the whole brain [

33]. GABA is synthesized and secreted by the oviductal mucosa [

34], and its concentration is greater at diestrus [

33]. Here, we report that ALDH9A1 is highly expressed in the oviductal mucosa (

Figure 9), which correlates well with GABA abundance; however, its physiological role in the oviduct

in vivo remains to be determined. Recently, ALDH9A1 was shown to exhibit wide substrate specificity, but has a clear preference for γ-trimethylaminobutyraldehyde (Km = 6 mM) [

35]; other novel identified substrates include 4-guanidinobutyraldehyde (GBAL) and 3-aminopropanal (APAL), with Km values of 21 ± 2 mM and 56 ± 7 mM, respectively [

35]. APAL is produced during spermine metabolism by the sequential actions of

spermine oxidase and

polyamine oxidase [

36]. Interestingly, spermine is a ubiquitous polyamine present at millimolar concentrations in the seminal plasma of many species, including humans, rats, and rams [

37]. Spermine is rapidly incorporated into sperm during ejaculation and temporarily inhibits premature capacitation and the spontaneous acrosome reaction (sAR); indeed, spermine has been proposed as the major decapacitation factor in seminal fluid [

38,

39,

40]. Therefore, considering that ALDH9A1 participates in spermine metabolism and GABA production and since we detected i) acrosome-reacted sperm in close contact with HNK-1-ALDH9A1 in the UTJ and ii) the distribution of HNK-1-ALDH9A1 in the isthmus, we propose that the HNK -1-ALDH9A1 in close contact with sperm could adjust the content of spermine in the spermatozoa during their journey to the site of fertilization. Therefore, if spermatozoa with a low content of spermine arrives at the UTJ and contacts HNK-1-ALDH9A1 regions, the spermine content will surpass the critical limit, and the spermatozoa will be induced to undergo sAR or AR because of the GABA present in the oviductal mucosa. Thus, HNK-1-ALDH9A1 in the UTJ and isthmus could control the quality of sperm arriving to the fertilization site. This hypothesis merits further research to propose the use of HNK-1-ALDH9A1 in the selection of sperm in procedures of assisted reproduction.

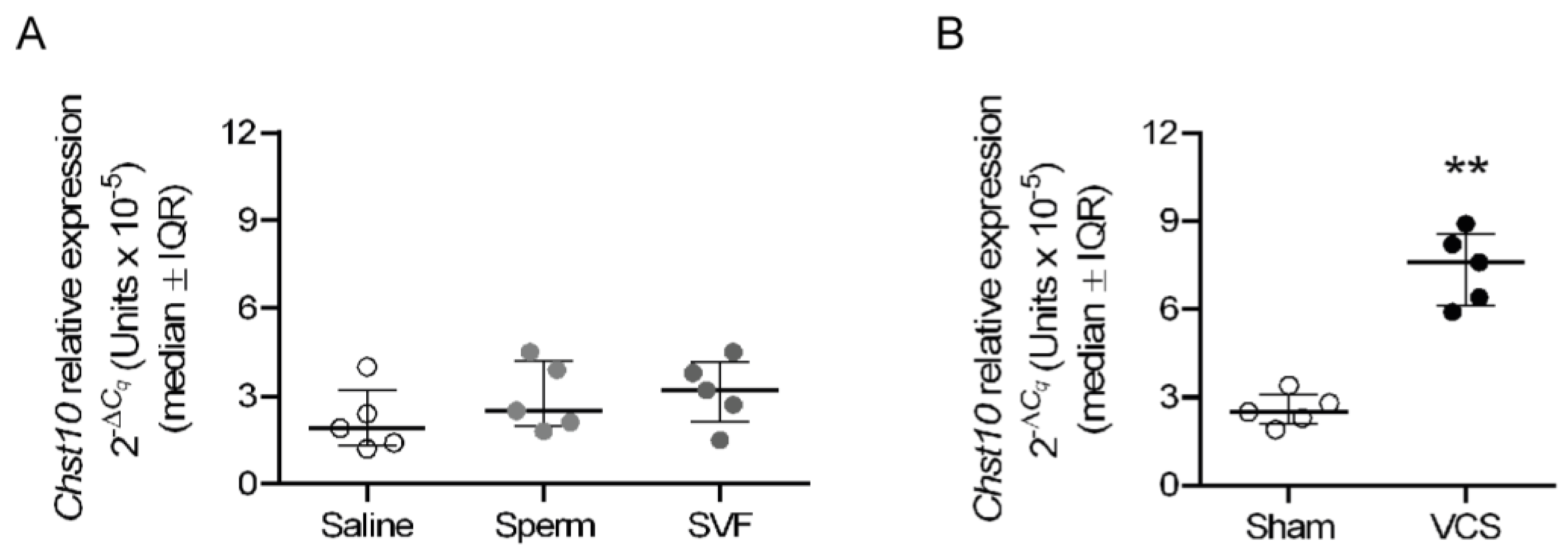

Finally, sensorial stimulation of the vaginocervical area induces the physiological processes necessary for female reproductive success, such as ovulation in rabbits [

41] and pseudopregnancy in spontaneous ovulators such as rats [

42]. Here, we showed that VCS increases the mRNA level of

Chst10 in the oviductal mucosa of rats. Our data suggest that, in the oviductal mucosa, an increase in

Chst10 transcripts is correlated with increased CHST10 protein levels and activity; therefore, we propose that all events described in this paper could be regulated by the sensorial component of mating. It is conceivable that signals regulating sperm‒oviduct interactions must arrive at the oviduct earlier than sperm. Thus, the sensorial stimulation associated with mating possibly arrives at the oviduct via the neuronal network that connects the vagina to the oviduct [

43], since sperm arrives in the oviduct 15 min after mating [

44]. Therefore, our findings merit further research since they suggest that the sensorial component of mating could regulate events occurring in the oviductal mucosa early after mating.

Figure 1.

Mating increases the CHST10 protein level in the oviductal mucosa. Western blot of samples obtained from the oviductal mucosa of unmated (UM1-4) and mated (M1-4) rats. Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph represents the intensities of the three CHST10 isoforms detected by western blot normalized to that of TUBB. IQR: Interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Mating increases the CHST10 protein level in the oviductal mucosa. Western blot of samples obtained from the oviductal mucosa of unmated (UM1-4) and mated (M1-4) rats. Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph represents the intensities of the three CHST10 isoforms detected by western blot normalized to that of TUBB. IQR: Interquartile range.

Figure 2.

Expression of CHST10 in the oviduct. CHST10 was detected in oviductal sections obtained from unmated and mated rats via immunofluorescence. The panels show the merged red and blue fluorescence. CHST10: red; and nuclear staining: blue. First row: ampulla; second row: isthmus; and third row: utero-tubal junction (UTJ). The panels in the left column are the negative controls. White arrowheads: immune cells in negative controls; red arrowheads: CHST10 signal resembling the Golgi apparatus location; red arrows: CHST10 in the epithelium cytoplasm. L, Lumen; E, mucosa layer; M, muscular layer. Original magnification, 20× (scale bar, 75 μm). Only the right panels display the image at 63× magnification (scale bar, 25 μm). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Expression of CHST10 in the oviduct. CHST10 was detected in oviductal sections obtained from unmated and mated rats via immunofluorescence. The panels show the merged red and blue fluorescence. CHST10: red; and nuclear staining: blue. First row: ampulla; second row: isthmus; and third row: utero-tubal junction (UTJ). The panels in the left column are the negative controls. White arrowheads: immune cells in negative controls; red arrowheads: CHST10 signal resembling the Golgi apparatus location; red arrows: CHST10 in the epithelium cytoplasm. L, Lumen; E, mucosa layer; M, muscular layer. Original magnification, 20× (scale bar, 75 μm). Only the right panels display the image at 63× magnification (scale bar, 25 μm). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Mating increases the CHST10 activity in the oviductal mucosa. (A) Michaelis‒Menten kinetics of human recombinant CHST10 to evaluate specific acceptor substrates. PGA: phenolphthalein glucuronic acid; E23G: 17b-estradiol 3-[b-D-glucuronide]. Biological replicates for each group, n = 3. (B) Pattern of acceptor substrate preferences for CHST10 (left) and total protein from the oviductal mucosa of unmated rats (right). CSA: chondroitin sulfate A; E2: 17b-estradiol; E217G: 17b-estradiol 17-[b-D-glucuronide]; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide. Biological replicates for each group, n = 3. (C) Plots of sulfotransferase activity measured in the oviductal mucosa of unmated and mated rats using PGA and E23G as acceptor substrates. Biological replicates for each group, n = 8.

Figure 3.

Mating increases the CHST10 activity in the oviductal mucosa. (A) Michaelis‒Menten kinetics of human recombinant CHST10 to evaluate specific acceptor substrates. PGA: phenolphthalein glucuronic acid; E23G: 17b-estradiol 3-[b-D-glucuronide]. Biological replicates for each group, n = 3. (B) Pattern of acceptor substrate preferences for CHST10 (left) and total protein from the oviductal mucosa of unmated rats (right). CSA: chondroitin sulfate A; E2: 17b-estradiol; E217G: 17b-estradiol 17-[b-D-glucuronide]; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide. Biological replicates for each group, n = 3. (C) Plots of sulfotransferase activity measured in the oviductal mucosa of unmated and mated rats using PGA and E23G as acceptor substrates. Biological replicates for each group, n = 8.

Figure 4.

Expression of HNK-1 moieties in the oviduct. Immunofluorescence images of the HNK-1 moiety in oviductal sections obtained from unmated and mated rats. The panels show merged green and blue fluorescence. HNK-1 moiety: green; and nuclear staining: blue. First row: ampulla; second row: isthmus; original magnifications are 20× and 40×, respectively (scale bar, 75 μm). The square in the middle panels is the location of the magnified image displayed in the right panel, original magnification, 63× (scale bar, 25 μm). Green arrows: apical location of HNK-1 moieties in epithelial cells; green arrowhead: luminal location of HNK-1 moieties; yellow arrowhead: acrosome-intact sperm in the lumen; asterisks: HNK-1 moieties located in the trenches of the mucosal folds. L: Lumen; E: mucosa layer; M: muscular layer.

Figure 4.

Expression of HNK-1 moieties in the oviduct. Immunofluorescence images of the HNK-1 moiety in oviductal sections obtained from unmated and mated rats. The panels show merged green and blue fluorescence. HNK-1 moiety: green; and nuclear staining: blue. First row: ampulla; second row: isthmus; original magnifications are 20× and 40×, respectively (scale bar, 75 μm). The square in the middle panels is the location of the magnified image displayed in the right panel, original magnification, 63× (scale bar, 25 μm). Green arrows: apical location of HNK-1 moieties in epithelial cells; green arrowhead: luminal location of HNK-1 moieties; yellow arrowhead: acrosome-intact sperm in the lumen; asterisks: HNK-1 moieties located in the trenches of the mucosal folds. L: Lumen; E: mucosa layer; M: muscular layer.

Figure 5.

Mating changes the levels of HNK-1 glycoproteins in the oviductal mucosa. (A) Western blotting via 1D electrophoresis was used to evaluate HNK-1 glycoproteins in the cellular pool of proteins from the oviductal mucosa. Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph presents the intensity of band 1 (130 kDa) normalized to that of TUBB. (B) Western blotting via 1D electrophoresis to evaluate HNK-1 glycoproteins in the secreted pool of proteins from the oviductal mucosa. Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph shows the intensity of band 2 (55 kDa) normalized to that of the total proteins with molecular weights less than 37 kDa, as detected by silver staining of the nitrocellulose membrane.

Figure 5.

Mating changes the levels of HNK-1 glycoproteins in the oviductal mucosa. (A) Western blotting via 1D electrophoresis was used to evaluate HNK-1 glycoproteins in the cellular pool of proteins from the oviductal mucosa. Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph presents the intensity of band 1 (130 kDa) normalized to that of TUBB. (B) Western blotting via 1D electrophoresis to evaluate HNK-1 glycoproteins in the secreted pool of proteins from the oviductal mucosa. Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph shows the intensity of band 2 (55 kDa) normalized to that of the total proteins with molecular weights less than 37 kDa, as detected by silver staining of the nitrocellulose membrane.

Figure 6.

Mating changes the levels of HNK-1 glycoproteins secreted from the oviductal mucosa. Western blotting via 2D electrophoresis of samples from unmated (upper) and mated (lower) rats. Several HNK-1-positive spots were detected in both samples. Black arrowheads: mating induced spots; green arrowheads: spots with increased intensities because of mating; red arrowheads: spots with decreased intensities because of mating; and white arrowheads: spots with any change in intensities between samples.

Figure 6.

Mating changes the levels of HNK-1 glycoproteins secreted from the oviductal mucosa. Western blotting via 2D electrophoresis of samples from unmated (upper) and mated (lower) rats. Several HNK-1-positive spots were detected in both samples. Black arrowheads: mating induced spots; green arrowheads: spots with increased intensities because of mating; red arrowheads: spots with decreased intensities because of mating; and white arrowheads: spots with any change in intensities between samples.

Figure 7.

Mating changes the protein core levels of HNK-1 glycoproteins secreted from the oviductal mucosa. Silver staining was performed on the membranes used for western blotting, as shown in

Figure 6. Arrowheads: HNK-1 glycoproteins.

Figure 7.

Mating changes the protein core levels of HNK-1 glycoproteins secreted from the oviductal mucosa. Silver staining was performed on the membranes used for western blotting, as shown in

Figure 6. Arrowheads: HNK-1 glycoproteins.

Figure 8.

Mating changes the levels of ALDH9A1 and ALDOA in the secreted pool of proteins from the oviductal mucosa. (A) ALDH9A1 western blot of samples (40 µg each) obtained from the oviductal mucosa of unmated (UM1-4) and mated (M1-4) (upper panel). Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph represents the intensity of the unique ALDH9A1 band (arrowhead) normalized to the total protein (TP) intensity between 40 and 60 kDa, as detected by Ponceau red staining of the nitrocellulose membrane (lower panel). (B) ALDOA western blot of samples (10 µg each) obtained from the oviductal mucosa of unmated (UM5-8) and mated (M5-8) rats (upper panel). Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph represents the intensity of the unique band (arrowhead) normalized to the TP intensity between 60 and 100 kDa, as detected by Ponceau red staining of the nitrocellulose membrane (lower panel).

Figure 8.

Mating changes the levels of ALDH9A1 and ALDOA in the secreted pool of proteins from the oviductal mucosa. (A) ALDH9A1 western blot of samples (40 µg each) obtained from the oviductal mucosa of unmated (UM1-4) and mated (M1-4) (upper panel). Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph represents the intensity of the unique ALDH9A1 band (arrowhead) normalized to the total protein (TP) intensity between 40 and 60 kDa, as detected by Ponceau red staining of the nitrocellulose membrane (lower panel). (B) ALDOA western blot of samples (10 µg each) obtained from the oviductal mucosa of unmated (UM5-8) and mated (M5-8) rats (upper panel). Biological replicates for each group, n = 4. The bar graph represents the intensity of the unique band (arrowhead) normalized to the TP intensity between 60 and 100 kDa, as detected by Ponceau red staining of the nitrocellulose membrane (lower panel).

Figure 9.

Expression patterns of the HNK-1 glycoproteins ALDH9A1 and ALDOA in the oviductal mucosa of mated rats. The HNK-1 moiety, ALDH9A1, ALDOA and TUBB were detected via immunofluorescence. In all panels, blue fluorescence corresponds to Hoechst nuclear staining. First row: signals from ALDH9A1 (red) and HNK-1 (green). The square in the UTJ panel is the location of the magnified image displayed in the second row. Asterisk: colocalization of the HNK-1 and ALDH9A1 signals in the isthmus. L, Lumen; E, mucosa layer; M, muscular layer. Second row: signals from ALDH9A1 (red) and HNK-1 (green). White arrows: colocalization of HNK-1 and ALDH9A1 signals; white arrowhead: acrosome-reacted sperm; yellow arrowhead: acrosome-intact sperm; red arrowhead: weak signal of ALDH9A1 on free sperm; green arrowhead: weak signal of the HNK-1 moiety on free sperm. Third row: TUBB location (green). The square in the middle panel is the location of the magnified image displayed in the right panel. Green arrows: ciliated cell clusters in the trenches of the mucosal folds. Fourth row: ALDOA location (red). The square in the middle panel is the location of the magnified image displayed in the right panel. Red arrow: ALDOA localization resembling mucin vesicles; red arrowhead: apical location of ALDOA in epithelial cells. Original magnification, 20× (scale bar, 75 μm). The images in the panels in the right column and in the second row are shown at a magnification of 63× (bar, 25 μm). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 9.

Expression patterns of the HNK-1 glycoproteins ALDH9A1 and ALDOA in the oviductal mucosa of mated rats. The HNK-1 moiety, ALDH9A1, ALDOA and TUBB were detected via immunofluorescence. In all panels, blue fluorescence corresponds to Hoechst nuclear staining. First row: signals from ALDH9A1 (red) and HNK-1 (green). The square in the UTJ panel is the location of the magnified image displayed in the second row. Asterisk: colocalization of the HNK-1 and ALDH9A1 signals in the isthmus. L, Lumen; E, mucosa layer; M, muscular layer. Second row: signals from ALDH9A1 (red) and HNK-1 (green). White arrows: colocalization of HNK-1 and ALDH9A1 signals; white arrowhead: acrosome-reacted sperm; yellow arrowhead: acrosome-intact sperm; red arrowhead: weak signal of ALDH9A1 on free sperm; green arrowhead: weak signal of the HNK-1 moiety on free sperm. Third row: TUBB location (green). The square in the middle panel is the location of the magnified image displayed in the right panel. Green arrows: ciliated cell clusters in the trenches of the mucosal folds. Fourth row: ALDOA location (red). The square in the middle panel is the location of the magnified image displayed in the right panel. Red arrow: ALDOA localization resembling mucin vesicles; red arrowhead: apical location of ALDOA in epithelial cells. Original magnification, 20× (scale bar, 75 μm). The images in the panels in the right column and in the second row are shown at a magnification of 63× (bar, 25 μm). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 10.

VCS increases the level of Chst10 in the oviductal mucosa. The graphs show the RT‒qPCR results for Chst10 normalized to the expression of Actb and Gapdh (reference genes). The scatter plots represent the normalized individual data points after 2−ΔCq transformation for each individual sample. (A) Oviductal mucosa obtained 3 h after intrauterine injection of 0.1 mL of saline (0.9% w/v NaCl), a suspension of sperm in saline (10 million cells), or diluted seminal vesicle fluid (SVF, 1:1 dilution) into unmated rats. Biological replicates for each group, n = 5. (B) Oviductal mucosa obtained from unmated rats 3 h after VCS or sham stimulation. Biological replicates for each group, n = 5.

Figure 10.

VCS increases the level of Chst10 in the oviductal mucosa. The graphs show the RT‒qPCR results for Chst10 normalized to the expression of Actb and Gapdh (reference genes). The scatter plots represent the normalized individual data points after 2−ΔCq transformation for each individual sample. (A) Oviductal mucosa obtained 3 h after intrauterine injection of 0.1 mL of saline (0.9% w/v NaCl), a suspension of sperm in saline (10 million cells), or diluted seminal vesicle fluid (SVF, 1:1 dilution) into unmated rats. Biological replicates for each group, n = 5. (B) Oviductal mucosa obtained from unmated rats 3 h after VCS or sham stimulation. Biological replicates for each group, n = 5.

Table 1.

Proteins identified by mass spectrometry.

Table 1.

Proteins identified by mass spectrometry.

| Spot number |

Protein |

Gene |

Sequence coverage (%) |

Molecular mass (kDa) |

| 2 |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 9 family, member A1 |

Aldh9a1 |

37.2 |

54.1 |

| 3 |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 9 family, member A1 |

Aldh9a1 |

45.3 |

54.1 |

| 4 |

Fructose bisphosphate aldolase A |

Aldoa |

42.0 |

39.4 |

| 5 |

Four and a half LIM domains protein 1 |

Fhl1 |

59.3 |

31.9 |

| 6 |

Four and a half LIM domains protein 1 |

Fhl1 |

68.2 |

31.9 |