Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Perennial grasses have multiple important uses such as forage, cover crops, and intercrops, utilized in pest management and supporting scientific experiments. Among those grasses, Urochloa brizantha is a tropical forage, having vigorous deep roots, commonly used for arbuscular mycorrhizae (AMF) multiplication in glasshouse and nursery, developing infective propagules to be conserved in germplasm banks. Other grass species, such as Urochloa decumbens, is also used for arbuscular mycorrhizae multiplication in addition to its cultivation for guaranteeing the sustainability of livestock systems. In this study, the soil chemical characterization, microcharcoal content and AMF spore identification showed high amount of potassium (K), high microcharcoal content and the occurrence of AMF, most of Glomeraceae. Due to its economic importance for sustainable agricultural production and other uses besides its environmental services, more detailed research is needed on the biotic interactions and inoculant production in these studied grasses.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

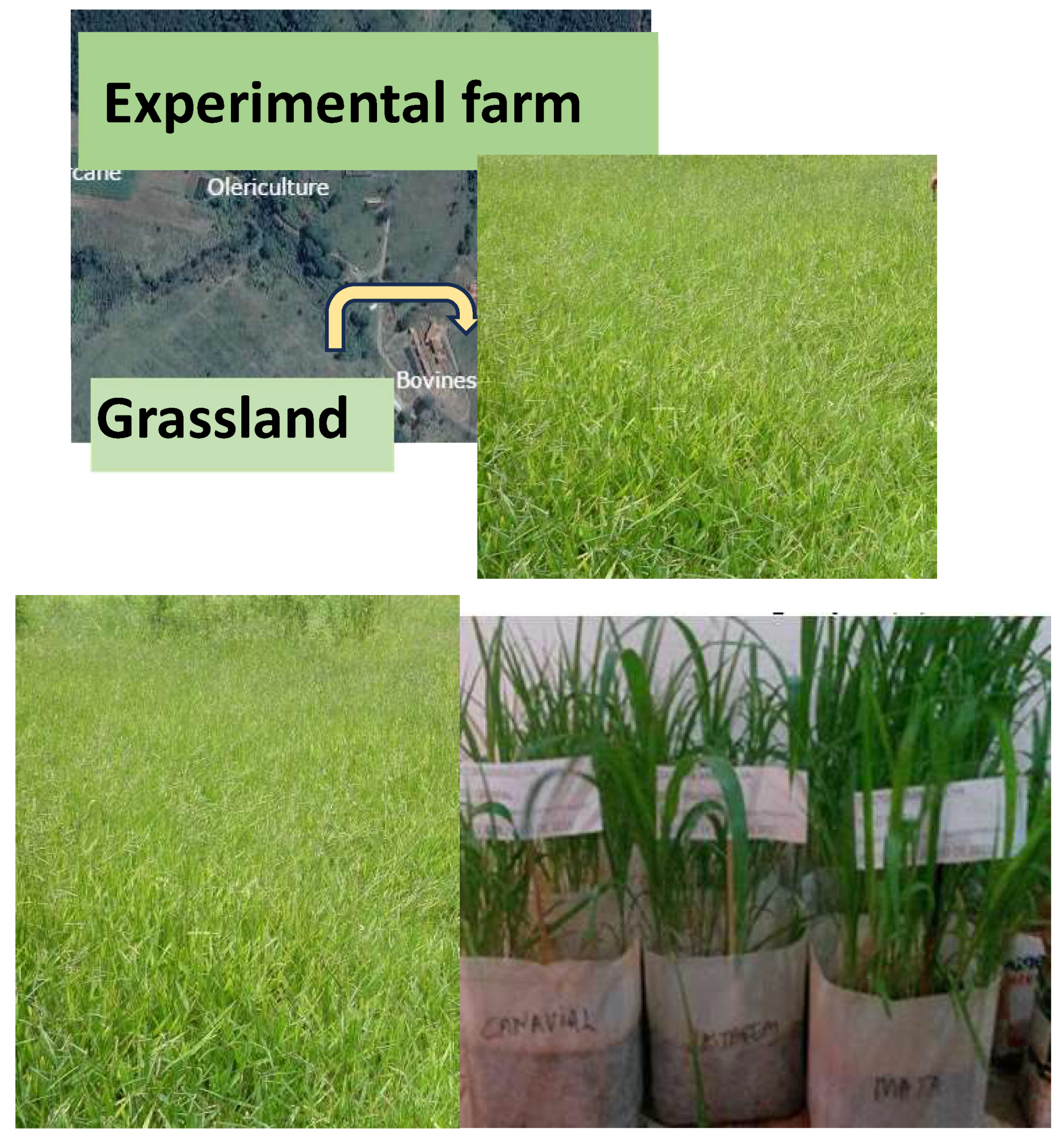

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Soil Sampling and Chemical Characterization

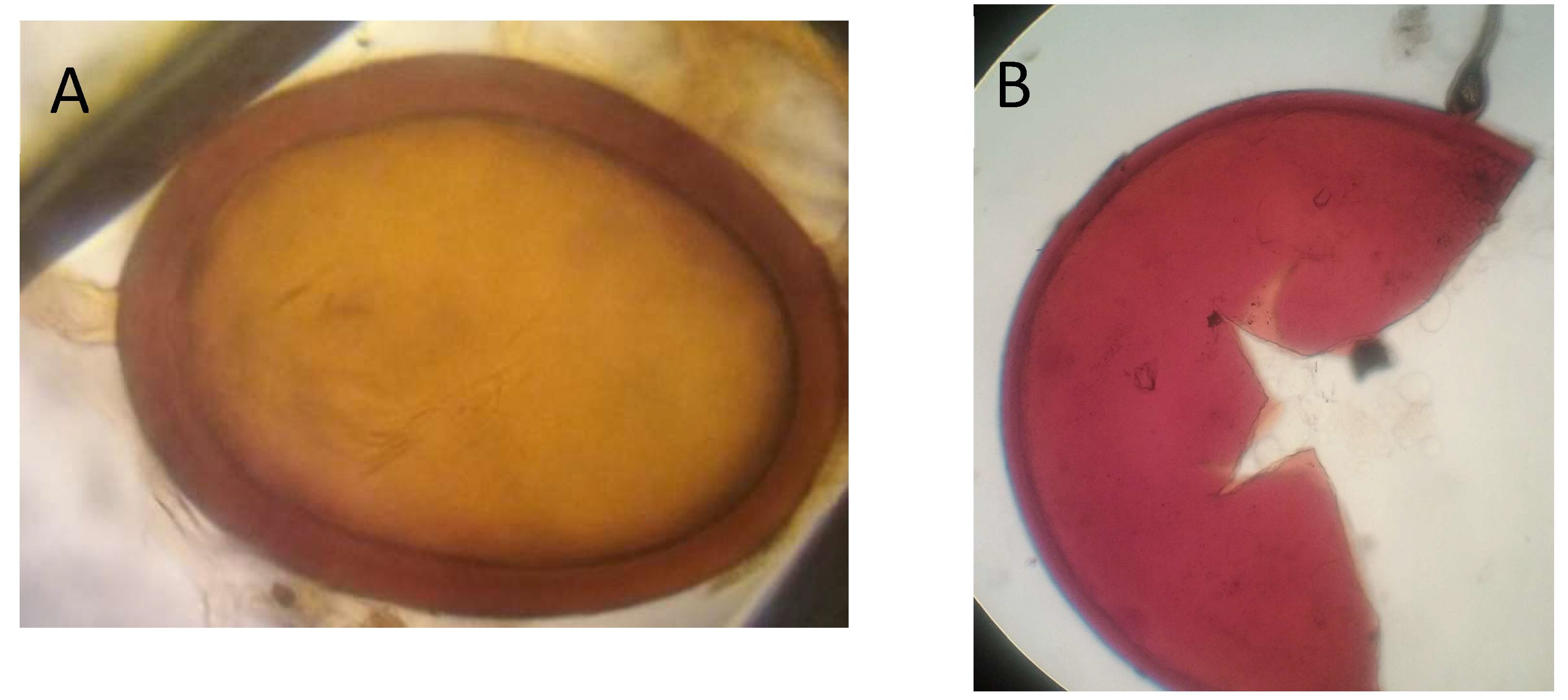

2.3. AMF Spore Isolation and Identification

2.4. Microcharcoal Content

3. Results

| Vegetation / Field/ greenhouse | Plant species | Geographical coordinates | Altitude (m asl) | Estimated age of cultivation (year) | AMF species/Glomalin | State | Reference |

| U. brizantha U. decumbens |

Experimental Station of The Cerrado |

Diversispora sp., Scutellospora sp. Glomus sp. Gigaspora sp. | GO | [4] | |||

| Greenhouse | U. brizantha | 19°42'51.5"S 44°53'37.0"W |

628,36 | >10 | A. colombiana, A. longula/ + | MG | [5] |

| [6] | |||||||

| U. brizantha | NA | SP | [7] | ||||

| U. brizantha | 48°26’W; 22°51’ S |

740 | NA | SP | [8] |

| pH (H2O) | 5.4 | ||

| OC (dag kg-1) | NA | ||

| Ca (cmolc kg-1) | 1.5 | ||

| Mg (cmolc kg-1) | 0.9 | ||

| Al (cmolc kg-1) | 0.7 | ||

| K mg⋅kg-1 | 43 | ||

| P mg⋅kg-1 | 1.8 | ||

| Soil texture | Clayey- loam | ||

| Charcoal content# | 19.66 |

| AMF Family | AMF species | ||||

| Ambisporaceae | Ambispora appendicula | ||||

| Claroideoglomeraceae | Claroideoglomus etunicatum | ||||

| Glomeraceae | Funneliformes geosporus | ||||

| Dentiscutataceae | Dentiscutata heterogama | ||||

| Glomeraceae | Glomus brohultii |

| AMF species | |||||||||||||

| Dentiscutataceae | |||||||||||||

| Dentiscutata heterogama | |||||||||||||

| Claroideoglomeraceae | |||||||||||||

| Claroideoglomus etunicatum | |||||||||||||

| Racocetraceae | |||||||||||||

| Racocetra fulgida | |||||||||||||

| Glomeraceae | |||||||||||||

| Funneliformes geosporus | |||||||||||||

| Glomus sp. 1 | |||||||||||||

| Glomus sp. 2 | |||||||||||||

4. Discussion

5.1. Urochloa Species in Cover Crops.

5.2. Urochloa Species for AMF Studies

5.3. Urochloa Species for Carbon Mitigation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

References

- Lambers, H, Cong, W-F. 2022. Challenges Providing Multiple Ecosystem Benefits for Sustainable Managed Systems. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng., 9 (2) 170-176. [CrossRef]

- Goldan, E. ; Nedeff, V, Barsan, N.,Culea,M.Panainte-Lehadus, M, Mosnegutu,E.,Tomozei,C., Chitimus, D.; Irimia, D. 2023. Assessment of Manure Compost Used as Soil Amendment—A Review. Processes. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Lucas, L. , Rubio Neto, M.A. de Moura, J., B. Fernandes de Souza, R., Fernandes Santos, M E.; Fernandes de Moura, L, Gomes Xavier, E. J M dos Santos, J.M., Dutra Silva, R. N. S. 2022 Mycorrhizal fungi arbuscular in forage grasses cultivated in Cerrado soil.2022. Scientific Reports, 12:3103. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M. V., Pedroso, D. de F.,F. Araujo Pinto, J. dos Santos V; Carbone Carneiro, M.A. 2019. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Urochloa brizantha: symbiosis and spore multiplication. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Tropical 49, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Alves Teixeira, R. Gazel Soares, T. Rodrigues Fernandes, A. Martins de Souza Braz, A. 2014. Grasses and legumes as cover crop in no-tillage system in northeastern Pará Brazil, Acta Amaz. [CrossRef]

- Baptistella, J.L.C.; Bettoni Teles, AP. Favarin J, Mazzafera, P. 2022 Phosphorus cycling by Urochloa decumbens intercropped with coffee. Experimental Agriculture, 58, 2022, e36.

- Crusciol et al. 2023. Lasting effect of Urochloa brizantha on a common bean-wheat-maize rotation in a medium-term no-till system. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 7. [CrossRef]

- Baptistella, J. L. C.; de Andrade S. A. L; Favarin J. L.; Mazzafera P. 2020. Urochloa in Tropical Agroecosystems, Frontiers in Sustainable food systems, 4, 119. 4.

- 11. Stevenson, J. 11. Stevenson, J., Haberle, S., 2005. Macro Charcoal Analysis: a Modified Technique Used by the Department of Archaeology and Natural History. Palaeoworks Technical Papers, p. 5.108.

- Varga, S. , Finozzi, C., Vestberg, M., K Arctic arbuscular mycorrhizal spore community and viability after storage in cold conditions. Mycorrhiza 25. 335–34.

- Pagano, MC; Duarte,NF., Corrêa, EJA. 2020. Effect of crop and grassland management on mycorrhizal fungi and soil aggregation. Applied Soil Ecology, 147p. 103385.

- Pedroso, D., Barbosa, M.V., dos Santos, J.V. et al. (2018). Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi favor the Initial Growth of Acacia mangium, Sorghum bicolor, and Urochloa brizantha in Soil Contaminated with Zn, Cu, Pb, and Cd. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 101, 386–391. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).