Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Vasculogenic mimicry (VM) has been recently discovered as an alternative mechanism to nourish cancer cells in vivo. During VM, tumor cells align and organize in three-dimensional (3D) channel-like structures to transport nutrients and oxygen to the internal layers of tumors. This mechanism occurs mainly in aggressive solid tumors and has been associated with poor prognosis in oncologic patients. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are essential regulators of protein-encoding genes involved in cancer development and progression. These single-stranded RNA molecules regulate critical cellular functions in cancer cells, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, VM, therapy response, migration, invasion, and metastasis. Recently, high-throughput RNA sequencing technologies have identified thousands of lncRNAs, but only a tiny percentage have been functionally characterized in human cancers. The vast amount of data about its genomic expression in tumors can allow us to dissect their functions in cancer biology and make them suitable biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Here, we have reviewed the current knowledge about the role of lncRNAs in VM in human cancers, with a special emphasis on their potential to be used as novel therapeutic targets in RNA-based molecular interventions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

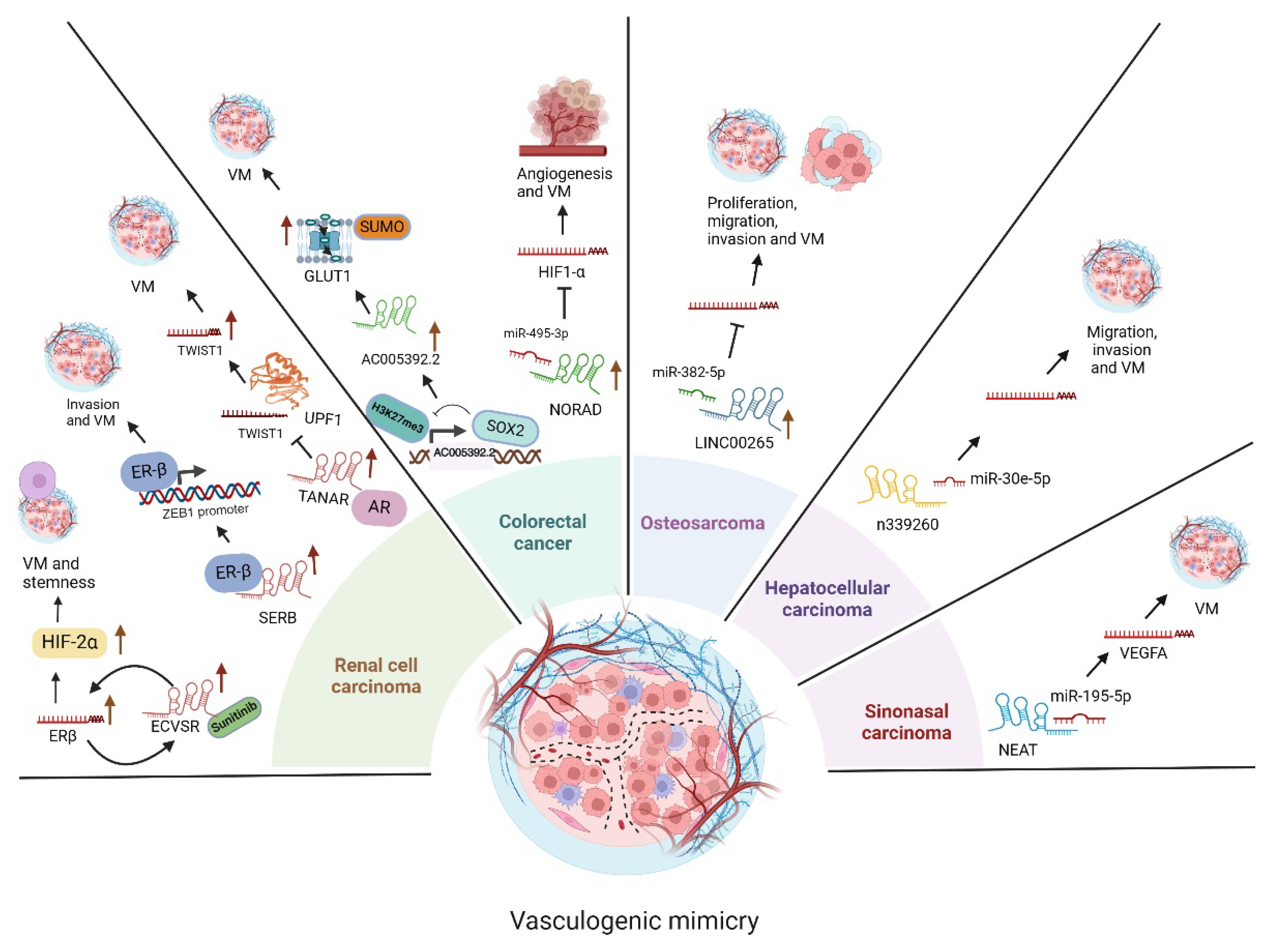

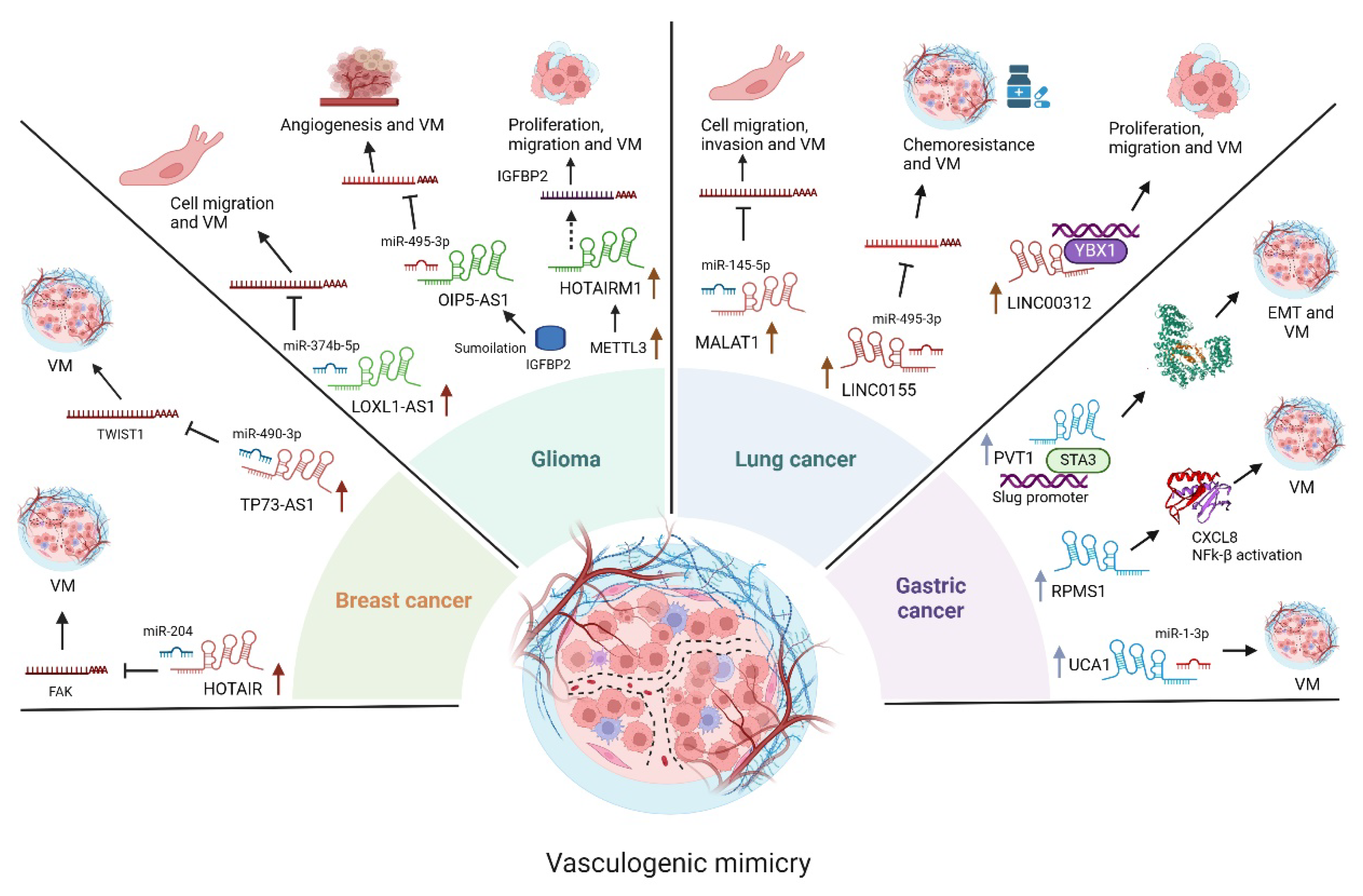

3.1. LncRNAs Functions in Glioma

3.2. LncRNAs Functions in Lung Cancer

3.3. LncRNAs Functions in Gastric Cancer

3.4. LncRNAs Functions in Breast Cancer

3.5. LncRNAs Functions in Renal Cell Carcinoma

3.6. LncRNAs Functions in Osteosarcoma

3.7. LncRNAs Functions in Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

3.8. LncRNAs Functions in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

3.9. LncRNA Functions in Sinonasal Cancer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tahara, S.; Rentsch, S.; De Faria, F. C. C.; Sarchet, P.; Karna, R.; Calore, F.; Pollock, R. E. Three-dimensional models. Oncol Res. 2024, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix, M. J.; Seftor, E. A.; Hess, A. R.; Seftor, R. E. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. Nature reviews. 2003, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzella, F.; Ribatti, D. Vascular co-option and vasculogenic mimicry mediate resistance to antiangiogenic strategies. Cancer reports 2022, 5, e1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schaft, D. W.; Seftor, R. E.; Seftor, E. A.; Hess, A. R.; Gruman, L. M.; Kirschmann, D. A.; Yokoyama, Y.; Griffioen, A. W.; Hendrix, M. J. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on vascular network formation by human endothelial and melanoma cells. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004, 96, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hernández, A. P.; Sánchez-Sánchez, G.; Carlos-Reyes, A.; López-Camarillo, C. Functional roles of microRNAs in vasculogenic mimicry and resistance to therapy in human cancers: an update. Expert review of clinical immunology. 2024, 20, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulitsky, I.; Bartel, D. P. lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell. 2013, 154, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekulaeva, M.; Rajewsky, N. Roles of Long Noncoding RNAs and Circular RNAs in Translation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2019, 11, a032680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuska, B. Should scientists scrap the notion of junk DNA? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 1032–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J. T. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018, 172, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A. M.; Chang, H. Y. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer cell. 2016, 29, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cai, H.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Gong, W.; Chen, J.; Xi, Z.; Xue, Y. Long Non-coding RNA LINC00339 Stimulates Glioma Vasculogenic Mimicry Formation by Regulating the miR-539-5p/TWIST1/MMPs Axis. Molecular therapy. Nucleic acids. 2018, 10, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wei, N. METTL3-mediated HOTAIRM1 promotes vasculogenic mimicry icontributionsn glioma via regulating IGFBP2 expression. Journal of translational medicine. 2023, 21, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Yang, Y. T.; Xu, X. D.; Chen, J. S.; Chen, T. L.; Chen, H. J.; Zhu, Y. B.; Lin, J. Y.; Li, Y.; et al. IGFBP2 promotes vasculogenic mimicry formation via regulating CD144 and MMP2 expression in glioma. Oncogene. 2019, 38, 1815–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, D.; Yi, B.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y.; Lou, X.; Xi, Z.; Li, Z. SUMOylation of IGF2BP2 promotes vasculogenic mimicry of glioma via regulating OIP5-AS1/miR-495-3p axis. International journal of biological sciences. 2021, 17, 2912–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, B.; Li, H.; Cai, H.; Lou, X.; Yu, M.; Li, Z. LOXL1-AS1 communicating with TIAR modulates vasculogenic mimicry in glioma via regulation of the miR-374b-5p/MMP14 axis. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2022, 26, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, T.; Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; He, J. Long non-coding RNA HULC stimulates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process and vasculogenic mimicry in human glioblastoma. Cancer medicine. 2021, 10, 5270–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ruan, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Shao, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, L.; et al. HNRNPD interacts with ZHX2 regulating the vasculogenic mimicry formation of glioma cells via linc00707/miR-651-3p/SP2 axis. Cell death & disease 2021, 12, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, F.; Ruan, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, D.; Zheng, J.; Xue, Y.; Shen, S.; Shao, L.; Yang, Y.; et al. The PABPC5/HCG15/ZNF331 Feedback Loop Regulates Vasculogenic Mimicry of Glioma via STAU1-Mediated mRNA Decay. Molecular therapy oncolytics. 2020, 17, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xue, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Shen, S.; Yang, C.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Ma, J.; et al. ZRANB2/SNHG20/FOXK1 Axis regulates Vasculogenic mimicry formation in glioma. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research 2019, 38, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari Kordkheyli, V.; Rashidi, M.; Shokri, Y.; Fallahpour, S.; Variji, A.; Nabipour Ghara, E.; Hosseini, S. M. CRISPER/CAS System, a Novel Tool of Targeted Therapy of Drug-Resistant Lung Cancer. Advanced pharmaceutical bulletin. 2022, 12, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, H. M., Fong, K. M. Lung cancer screening - Time for an update? Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2024, 196, 107956.

- Li, D.; Shen, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Repression of linc01555 up-regulates angiomotin-p130 via the microRNA-122-5p/clic1 axis to impact vasculogenic mimicry-mediated chemotherapy resistance in small cell lung cancer. Cell cycle. 2023, 22, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, J.; Shan, B.; Li, B.; Peng, W.; Dong, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhao, W.; He, D.; Duan, M.; et al. The long noncoding RNA LINC00312 induces lung adenocarcinoma migration and vasculogenic mimicry through directly binding YBX1. Molecular cancer 2018, 17, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Guo, M.; Xiang, R.; Xie, T.; Zhuang, X.; Dai, W.; Li, Q.; Lai, Q. Upregulation of long intergenic non-coding RNA LINC00326 inhibits non-small cell lung carcinoma progression by blocking Wnt/β-catenin pathway through modulating the miR-657/dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 2 axis. Biology direct. 2023, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Ding, J.; He, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, R.; Han, Z.; Xing, E. Z.; Zhang, C.; Yeh, S. Estrogen receptor β promotes the vasculogenic mimicry (VM) and cell invasion via altering the lncRNA-MALAT1/miR-145-5p/NEDD9 signals in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2019, 38, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Chen, M.; Li, Q.; Ma, K.; Xiao, P.; Luo, C. Hypomethylation-associated LINC00987 downregulation induced lung adenocarcinoma progression by inhibiting the phosphorylation-mediated degradation of SND1. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2024, 63, 1260–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blancas-Zugarazo, S. S.; Langley, E.; Hidalgo-Miranda, A. Exosomal lncRNAs as regulators of breast cancer chemoresistance and metastasis and their potential use as biomarkers. Frontiers in oncology. 2024, 14, 1419808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Pu, M.; Gong, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Ye, J.; Huang, H.; Liao, D.; Yang, Y.; Yin, A. METTL3-driven m6A modification of lncRNA FAM230B suppresses ferroptosis by modulating miR-27a-5p/BTF3 axis in gastric cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. General subjects 2024, 1868, 130714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, M.; Yu, K.; Liu, J.; Chang, J. Vasculogenic mimicry triggers early recidivation and resistance to adjuvant therapy in esophageal cancer. BMC cancer, 2024, 24, 1132.

- Wang, H.; Ding, Q.; Zhou, H.; Huang, C.; Liu, G.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, Z.; You, X. Dihydroartemisinin inhibited vasculogenic mimicry in gastric cancer through the FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology. 2024, 134, 155962.

- Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, J.; Sun, L.; Lin, L.; Huang, N.; Bin, J.; Liao, Y.; Liao, W. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 promotes gastric cancer tumorigenicity and metastasis by regulating vasculogenic mimicry and angiogenesis. Cancer letters, 2017, 395, 31–44.

- Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, G.; Qin, LLncRNA PVT1 induces aggressive vasculogenic mimicry formation through activating the STAT3/Slug axis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer. Cellular oncology, 2020, 43, 863–876.

- Zhang, J. Y.; Du, Y.; Gong, L. P.; Shao, Y. T.; Wen, J. Y.; Sun, L. P.; He, D.; Guo, J. R.; Chen, J. N.; Shao, C. K. EBV-Induced CXCL8 Upregulation Promotes Vasculogenic Mimicry in Gastric Carcinoma via NF-κB Signaling. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2022, 12, 780416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, B.; Shen, A.; Yu, K.; Ma, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, H. LncRNA UCA1 promotes vasculogenic mimicry by targeting miR-1-3p in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2024, 45, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2024, 74, 229–263.

- Kondov, B.; Milenkovikj, Z.; Kondov, G.; Petrushevska, G.; Basheska, N.; Bogdanovska-Todorovska, M.; Tolevska, N.; Ivkovski, L. Presentation of the Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer Detected By Immunohistochemistry in Surgically Treated Patients. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2018, 6, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Romero, A.; Astudillo-de la Vega, H.; Terrones-Gurrola, M. C. D. R.; Marchat, L. A.; Hernández-Sotelo, D.; Salinas-Vera, Y. M.; Ramos-Payan, R.; Silva-Cázares, M. B.; Nuñez-Olvera, S. I.; Hernández-de la Cruz, O. N. HOX Transcript Antisense RNA HOTAIR Abrogates Vasculogenic Mimicry by Targeting the AngiomiR-204/FAK Axis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Non-coding RNA, 2020 6(2), 19.

- Tao, W.; Sun, W.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J. Knockdown of long non-coding RNA TP73-AS1 suppresses triple negative breast cancer cell vasculogenic mimicry by targeting miR-490-3p/TWIST1 axis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2028, 504, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, B.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Y.; Ji, R.; Gu, Q.; Dong, X.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Jia, X.; et al. Twist1 expression induced by sunitinib accelerates tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry by increasing the population of CD133+ cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Molecular cancer. 2014, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandpur, U.; Haile, B.; Makary, M. S. Early-Stage Renal Cell Carcinoma Locoregional Therapies: Current Approaches and Future Directions. Clinical Medicine Insights. Oncology. 2024, 18, 11795549241285390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Hu, Y.; Chang, C.; Liu, S.; Yeh, S. Sunitinib increases the cancer stem cells and vasculogenic mimicry formation via modulating the lncRNA-ECVSR/ERβ/Hif2-α signaling. Cancer letters. 2022, 524, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Chang, F.; Lv, Z.; Li, K.; Li, S.; Hu, Y.; Yeh, S. LncRNA-SERB promotes vasculogenic mimicry (VM) formation and tumor metastasis in renal cell carcinoma. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2024, 300, 107297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, B.; Sun, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, Q.; Fang, R.; Liu, B.; Chou, F.; Wang, R.; Meng, J. Androgen receptor promotes renal cell carcinoma (RCC) vasculogenic mimicry (VM) via altering TWIST1 nonsense-mediated decay through lncRNA-TANAR. Oncogene. 2021, 40, 1674–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Han, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, S. LncRNAs as potential prognosis/diagnosis markers and factors driving drug resistance of osteosarcoma, a review. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2024, 15, 1415722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenbach-Désor, T.; Niesner, I.; Ahmed, P.; Dürr, H. R.; Klein, A.; Knösel, T.; Gospos, J.; McGovern, J. A.; Hutmacher, D. W.; Holzapfel, B. M. Tissue-engineered patient-derived osteosarcoma models dissecting tumour-bone interactions. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2024, 44, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y. LINC00265 targets miR-382-5p to regulate SAT1, VAV3 and angiogenesis in osteosarcoma. Aging. 2020, 12, 20212–20225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhao, W.; Lv, Z.; Xie, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. The functions and mechanisms of long non-coding RNA in colorectal cancer. Frontiers in oncology. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S.; Nandi, S.; Nayak, A. Unraveling the complexities of colorectal cancer and its promising therapies - An updated review. International immunopharmacology. 2024, 143(Pt 1) Pt 1, 113325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zheng, H. SOX2 promotes vasculogenic mimicry by accelerating glycolysis via the lncRNA AC005392.2-GLUT1 axis in colorectal cancer. Cell death & disease. 2023, 14, 791.

- Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Chu, F., Zhang, L. Induction of lncRNA NORAD accounts for hypoxia-induced chemoresistance and vasculogenic mimicry in colorectal cancer by sponging the miR-495-3p/ hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α). Bioengineered. 2022, 13, 950–962.

- Zhang, X., Wang, H., Yuan, Y., Zhang, J., Yang, J., Zhang, L., & He, J. PPM1G and its diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic potential in HCC (Review). International journal of oncology. 2024, 65, 109.

- Liu, T., Liao, S., Mo, J., Bai, X., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, D., Cheng, R., Zhao, N., Che, N., Guo, Y., Dong, X., & Zhao, X. LncRNA n339260 functions in hepatocellular carcinoma progression via regulation of miRNA30e-5p/TP53INP1 expression. Journal of gastroenterology. 2022, 57, 784–797.

- Thawani, R.; Kim, M. S.; Arastu, A.; Feng, Z.; West, M. T.; Taflin, N. F.; Thein, K. Z.; Li, R.; Geltzeiler, M.; Lee, N. The contemporary management of cancers of the sinonasal tract in adults. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2023, 73, 72–112.

- Lu, H.; Kang, F. Down-regulating NEAT1 inhibited the viability and vasculogenic mimicry formation of sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma cells via miR-195-5p/VEGFA axis. Bioscience reports. 2020, 40, BSR20201373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).