Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

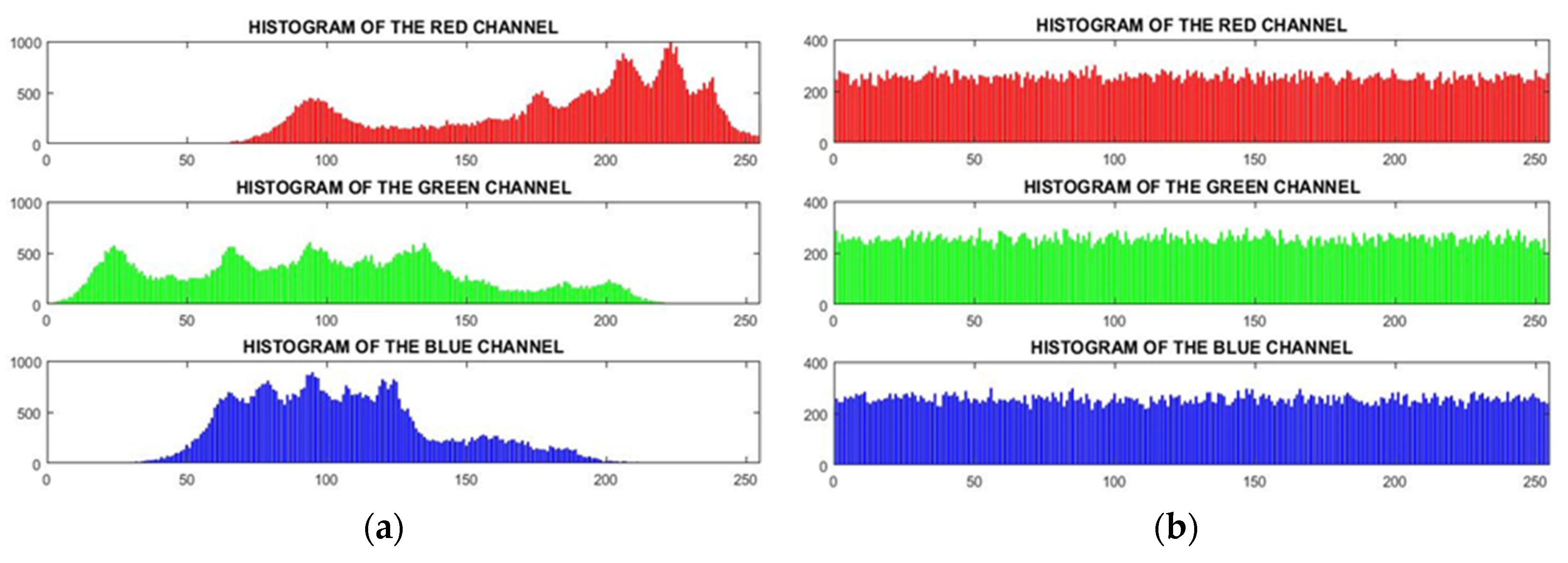

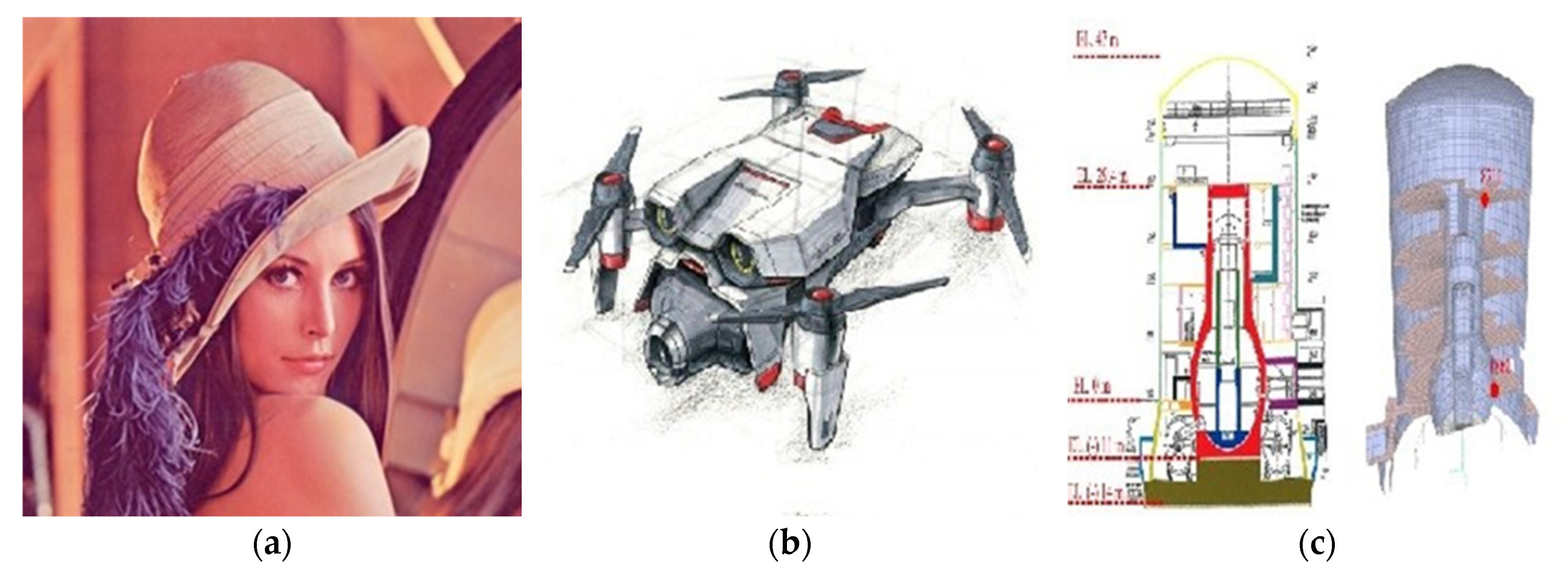

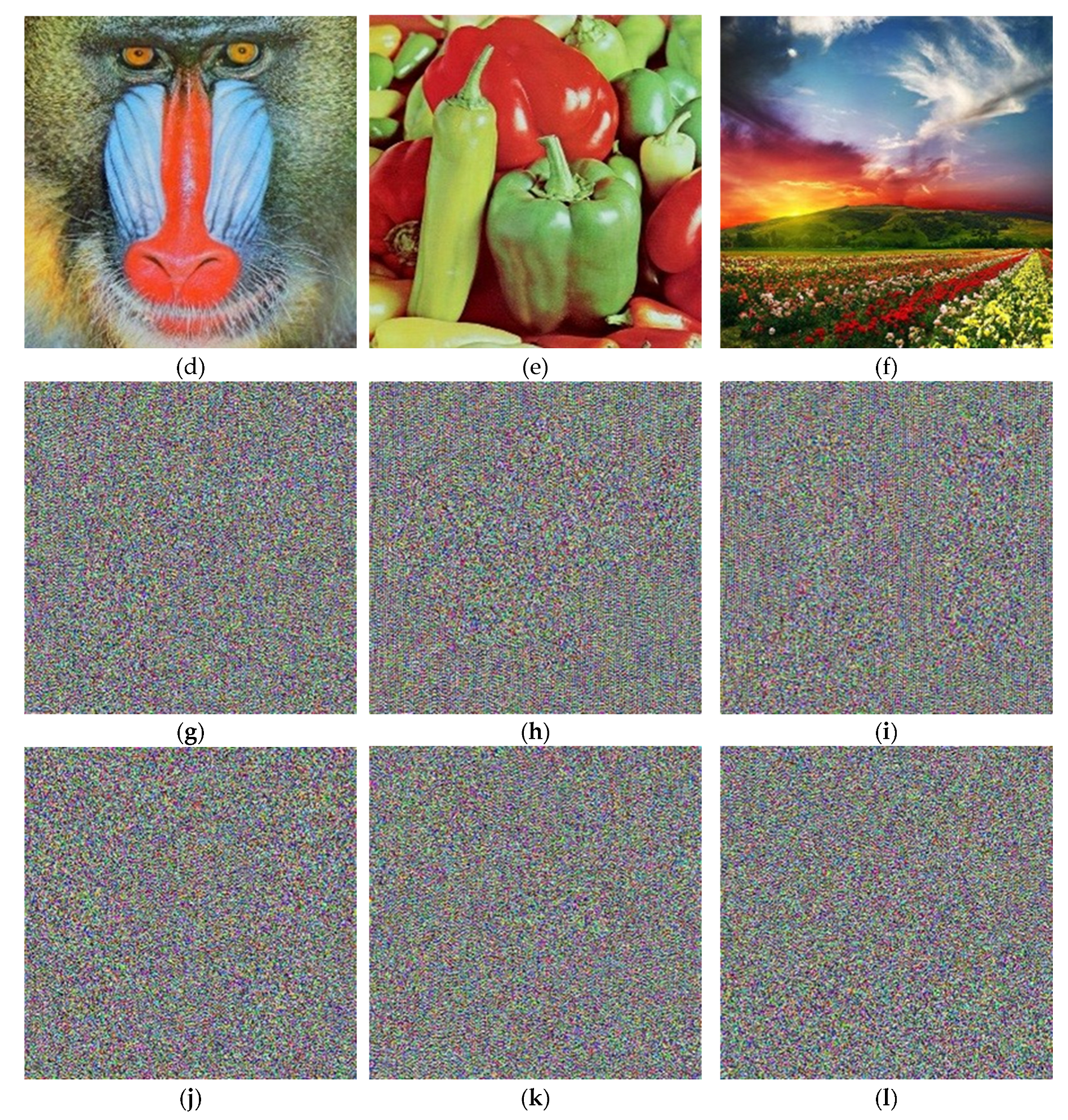

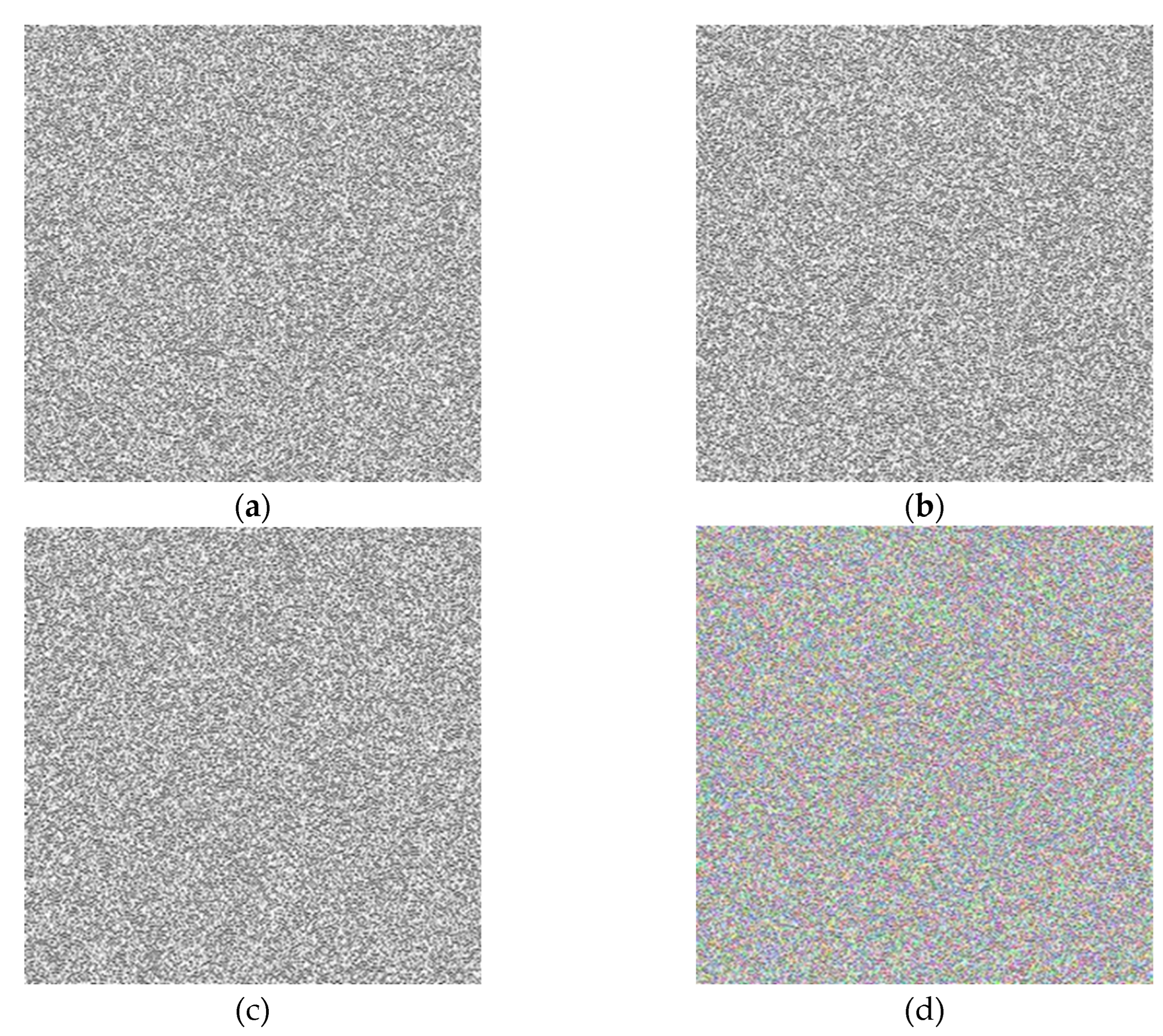

This study presents a novel encryption method for RGB (Red-Green-Blue) color images that combines scrambling techniques with the logistic map equation. In this method, image scrambling serves as a reversible transformation, rendering the image unintelligible to unauthorized users and thus enhancing security against potential attacks. The proposed encryption scheme, called Bit-Plane Representation of Quantum Images (BRQI), utilizes quantum operations in conjunction with a one-dimensional chaotic system to increase encryption efficiency. The encryption algorithm operates in two phases: first, the quantum image undergoes scrambling through bit-plane manipulation, and second, the scrambled image is mixed with a key image generated using the logistic map. To assess the performance of the algorithm, simulations and analyses were conducted, evaluating parameters such as entropy (a measure of disorder) and correlation coefficients confirm the effectiveness and robustness of this algorithm in safeguarding and encoding color images. The results show that the proposed quantum color image encryption algorithm surpasses classical methods in terms of security, robustness, and computational complexity.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

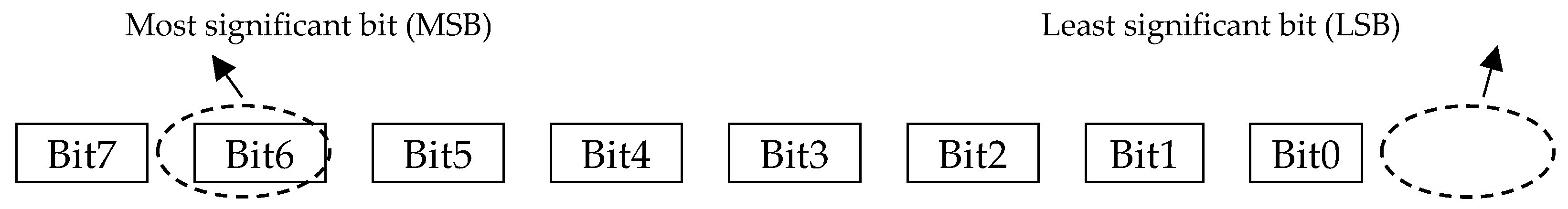

2.1. Bit and Qubits

2.2. Quantum Gates and Circuits

3. Our Proposed Model for Quantum Encryption Method for RGB Images Based on Bit-Planes and Logistic Maps

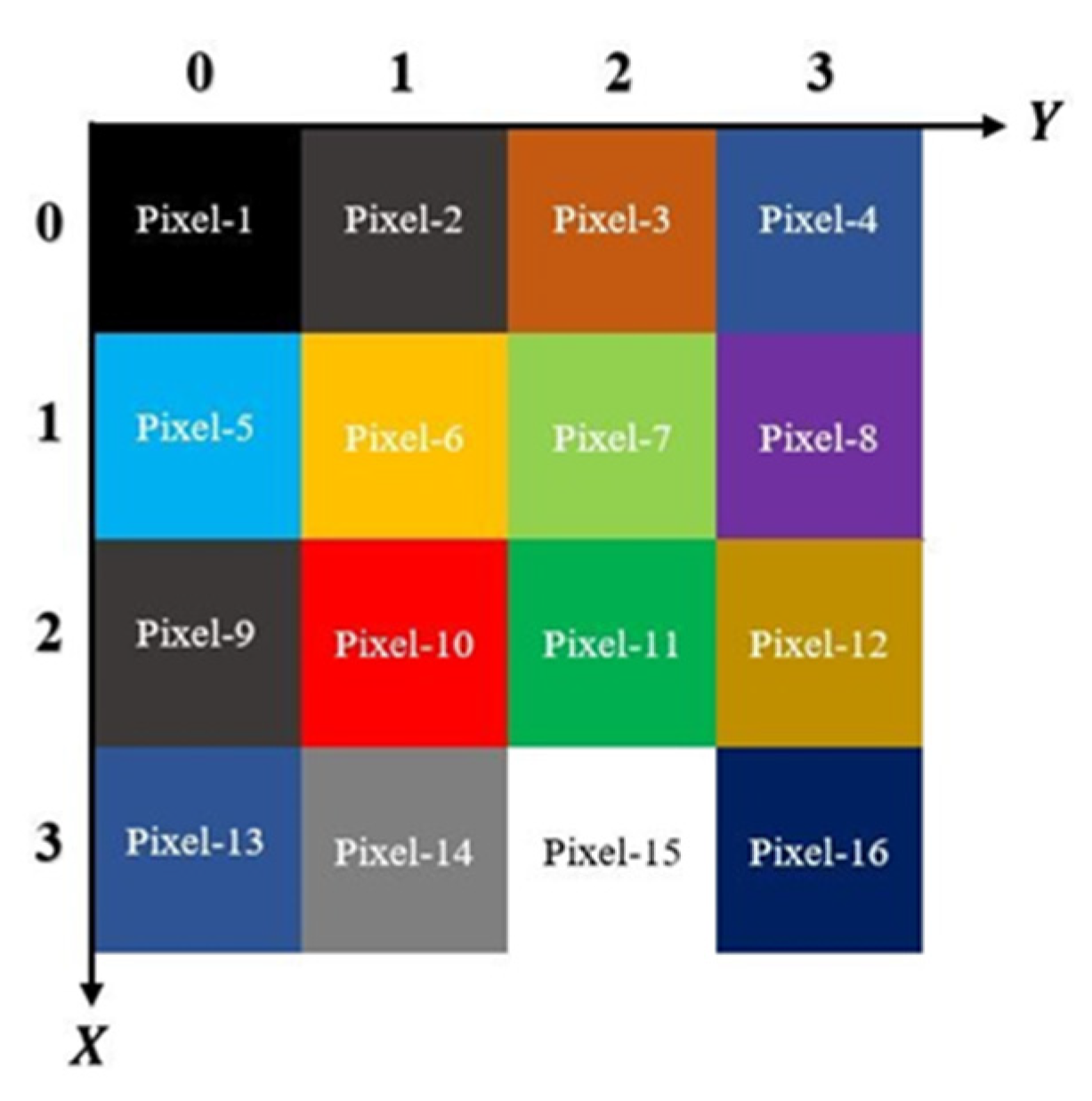

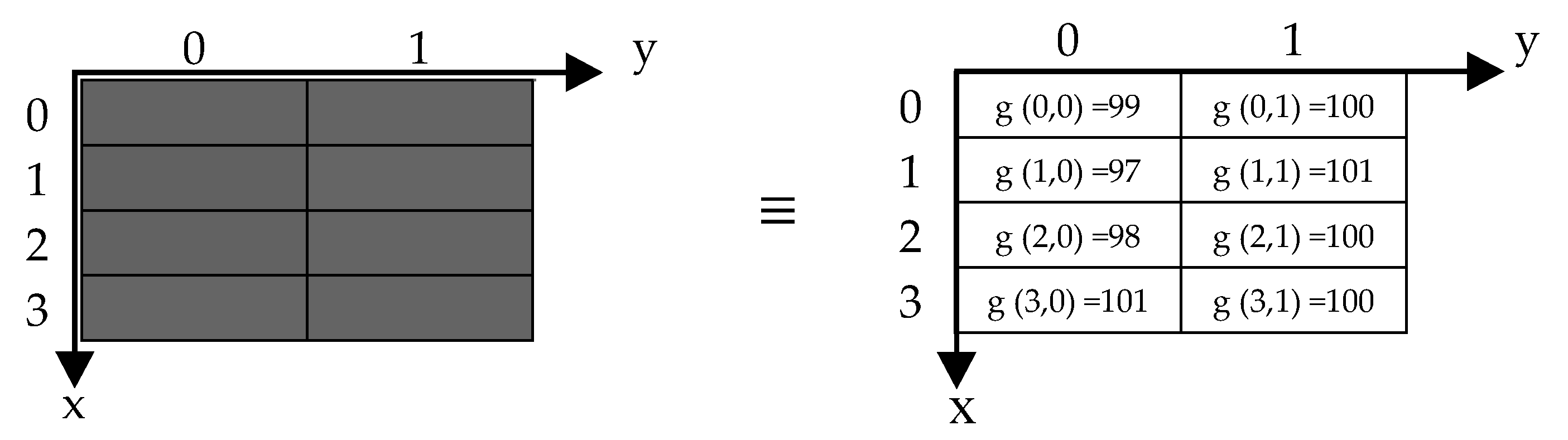

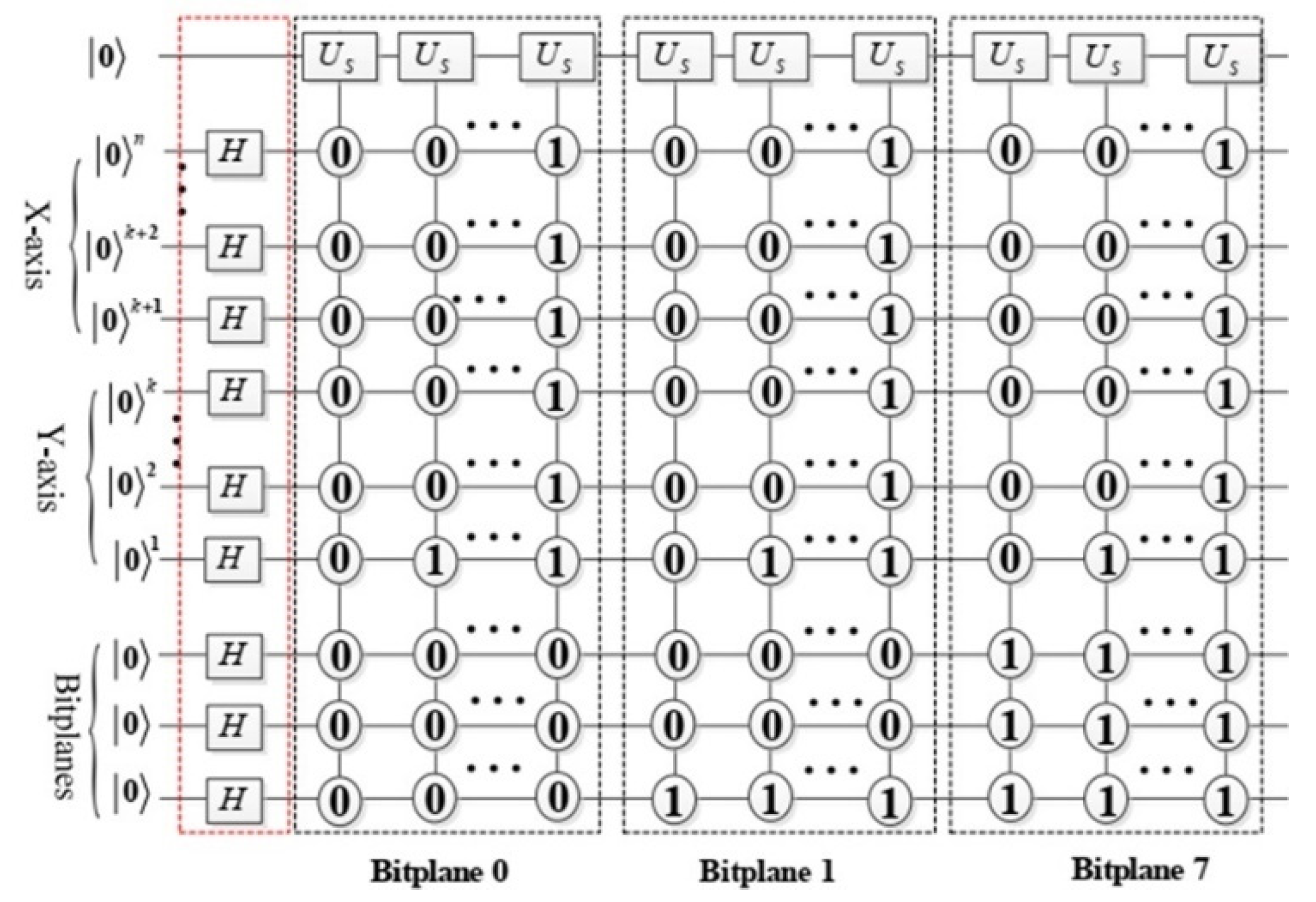

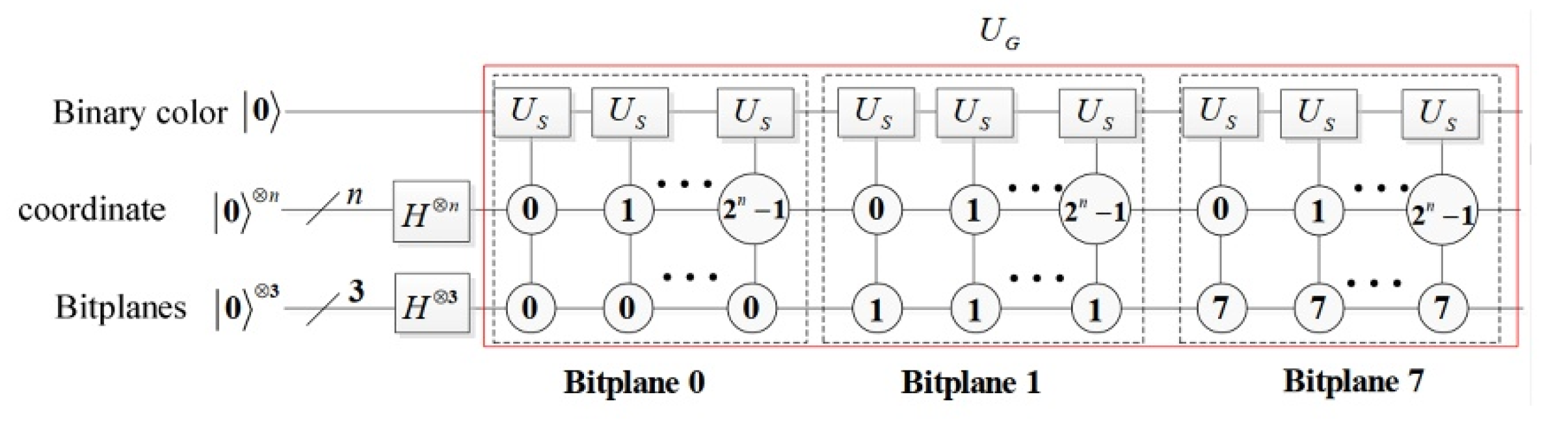

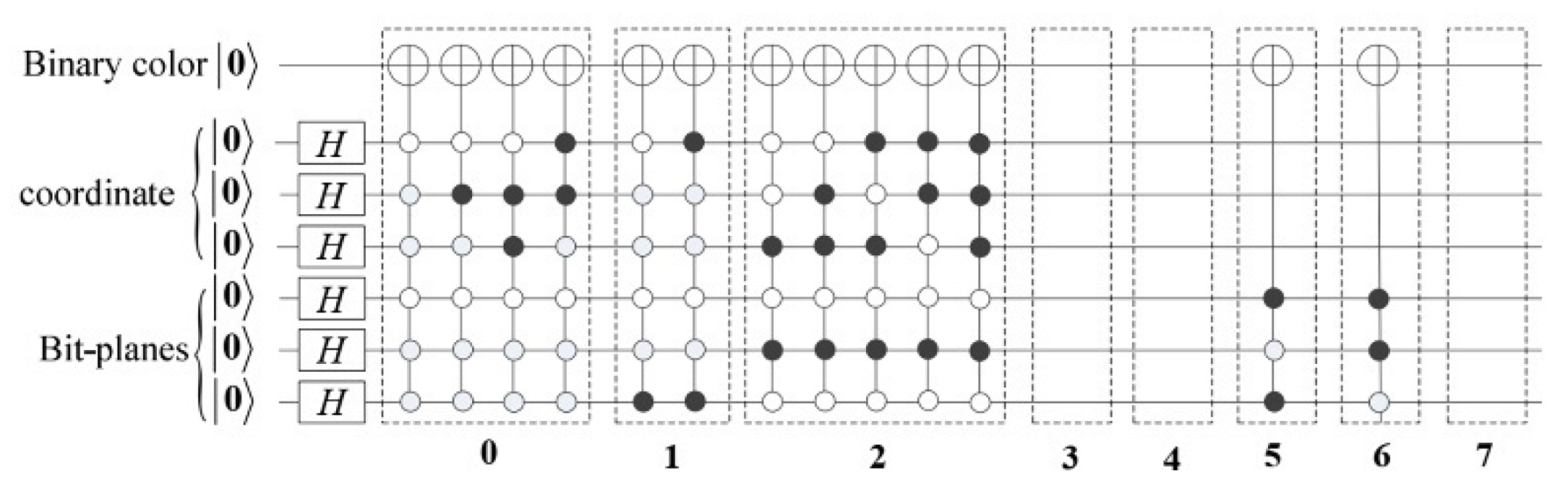

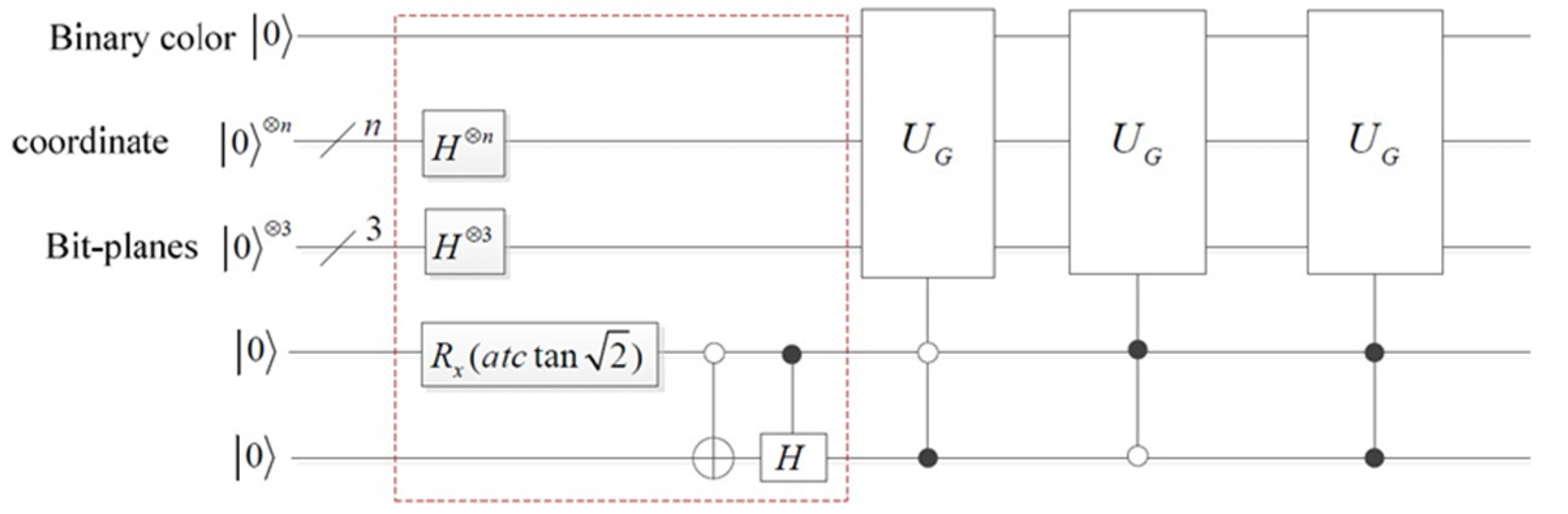

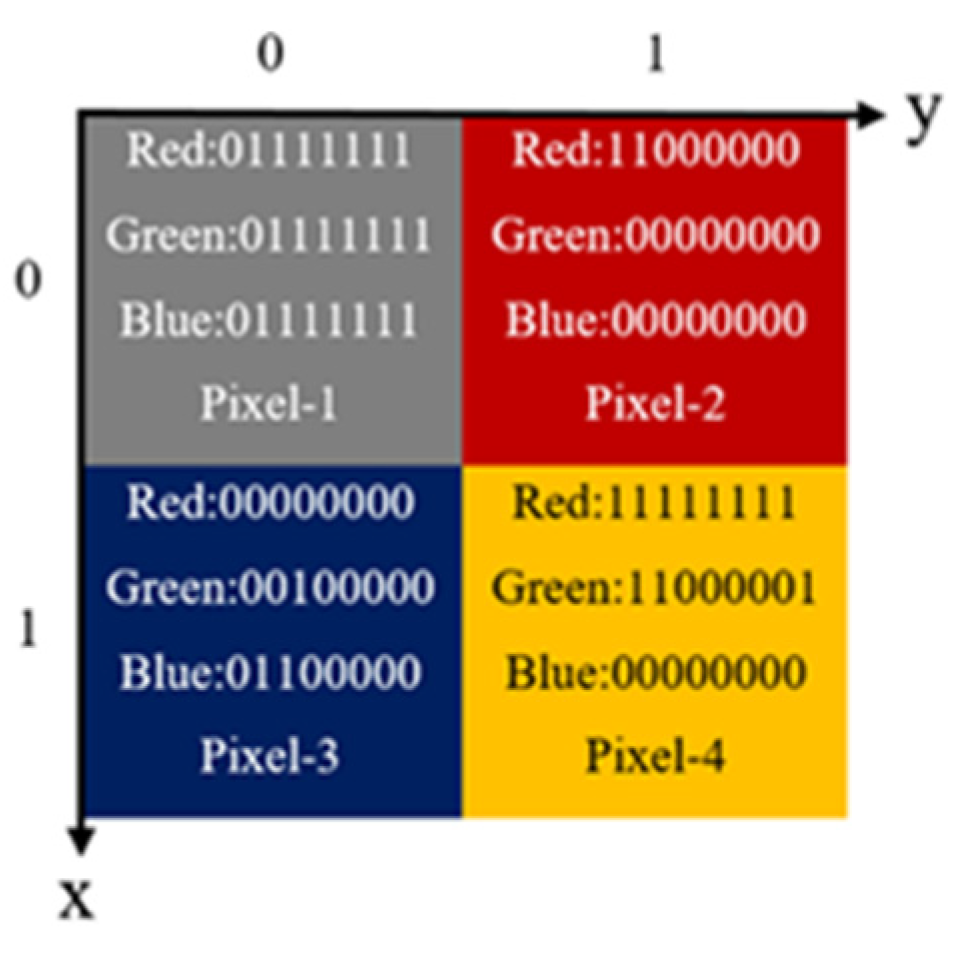

3.1. BRQI for RGB Color Images

3.2. Our Model for RGB Images Encryption Based on Bit-Planes and Logistic Maps

3.2.1. Image Scrambling Process

- 1.

- Swapping bit-planes;

- 2.

- Transferring image bitplanes;

- 3.

- Color complement.

3.2.2. Constructing Process

4. Analyzing the Proposed Method

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morkel, T.; Eloff, J.H.P.; Olivier, M.S. An Overview of Image Steganography. Information and Computer Security Architecture (ICSA) Research Group, 2005.

- Pahati, O.J. Confounding Carnivore: How to Protect Your Online Privacy. AlterNet, 2001-11-29. Archived from the original on 2007-07-16. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- Singh, L.D.; Singh, K.M. Image Encryption Using Elliptic Curve Cryptography. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 54, 287–294.

- Lukac, R.; Plataniotis, K.N. Bit-Level-Based Secret Sharing for Image Encryption. Pattern Recognition 2005, 38, 873–882.

- Mishra, R.; Bhanodiya, P. A Review on Steganography and Cryptography. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computer Engineering and Applications, IEEE, March 2015.

- Kamali, S.H.; Shakerian, R.; Hedayati, M.; Rahmani, M. A New Modified Version of Advanced Encryption Standard Based Algorithm for Image Encryption. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronics and Information Engineering, IEEE, August 2010.

- Jiang, N.; Wang, L.; Wu, W. Quantum Hilbert Image Scrambling. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 2014, 53, 2655–2663.

- Jiang, N.; Wu, W.; Wang, L. The Quantum Realization of Arnold and Fibonacci Image Scrambling. Quantum Information Processing 2014, 13, 2179–2192.

- Sankpal, P.R.; Vijaya, P.A. Image Encryption Using Chaotic Maps: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Signal and Image Processing, IEEE, January 2014.

- Chen, J.X.; Zhu, Z.L.; Liu, Z.; Fu, C.; Zhang, L.B.; Yu, H. A Novel Double-Image Encryption Scheme Based on Cross-Image Pixel Scrambling in Gyrator Domains. Optics Express 2014, 22, 10343–10356.

- Wong, K.W.; Kwok, B.S.H.; Yuen, C.H. An Efficient Diffusion Approach for Chaos-Based Image Encryption. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2009, 42, 1877–1888.

- Yang, Y.; Jia, X.; Xu, P.; Tian, J. Analysis and Improvement of the Watermark Strategy for Quantum Images Based on Quantum Fourier Transform. Quantum Information Processing 2013, 12, 2971–2990.

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Xia, H.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, Z. A Quantum Image Representation Based on Bitplanes. In Proceedings of the IEEE, 2018.

- Yan, F.; Iliyasu, A.M.; Venegas-Andraca, S.E. A Survey of Quantum Image Representations. Quantum Information Processing 2016, 15, 1065–1085.

- Erhard, M.; Krenn, M.; Zeilinger, A. Advances in High-Dimensional Quantum Entanglement. Nature Reviews Physics 2020, 2, 365–381.

- Vedral, V. Quantum Entanglement. Nature Physics 2014, 10, 256–258.

- Delaubert, V.; Treps, N.; Fabre, C.; Bachor, H.A.; Réfrégier, P. Quantum Limits in Image Processing. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 2008, 81, 44001.

- Venegas-Andraca, S.E.; Bose, S. Storing, Processing, and Retrieving an Image Using Quantum Mechanics. In Proceedings of Quantum Information and Computation, Volume 5105, pp. 137–147, 2003.

- Chakraborty, S.; Mandal, S.B.; Shaikh, S.H. Quantum Image Processing: Challenges and Future Research Issues. International Journal of Information Technology 2018, 10, 1–15.

- Ventura, D.; Martinez, T. Quantum Associative Memory with Exponential Capacity. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, World Congress on Computational Intelligence, Vol. 1, pp. 509–513, May 1998.

- Le, P.Q.; Dong, F.; Hirota, K. A Flexible Representation of Quantum Images for Polynomial Preparation, Image Compression, and Processing Operations. Quantum Information Processing 2011, 10, 63–84.

- Li, H.S.; Zhu, Q.; Li, M.C.; et al. Multidimensional Color Image Storage, Retrieval, and Compression Based on Quantum Amplitudes and Phases. Information Sciences 2014, 273, 212–232.

- Sun, B.; Iliyasu, A.M.; Yan, F.; Dong, F.; Hirota, K. An RGB Multi-Channel Representation for Images on Quantum Computers. Journal of Advanced Computational Intelligence and Intelligent Informatics 2013, 17, 404–417.

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, K.; Gao, Y.; Wang, M. NEQR: A Novel Enhanced Quantum Representation of Digital Images. Quantum Information Processing 2013, 12, 2833–2860.

- Abdolmaleky, M.; Naseri, M.; Batle, J.; Farouk, A.; Gong, L.H. Red-Green-Blue Multi-Channel Quantum Representation of Digital Images. Optik 2017, 128, 121–132.

- Li, H.S.; Fan, P.; Xia, H.Y.; et al. Quantum Implementation Circuits of Quantum Signal Representation and Type Conversion. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2018, 65, 1–14.

- Mona Abdolmaleky, Mosayeb Naseri, Josep Batle, Ahmed Farouk, Li-Hua Gong, Red-Green-Blue multi-channel quantum representation of digital images, Optik, Volume 128, 2017, Pages 121-132, ISSN 0030-4026. [CrossRef]

- Heidari, S., Naseri, M. A Novel LSB Based Quantum Watermarking. Int J Theor Phys 55, 4205–4218 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Mosayeb Naseri, Shahrokh Heidari, Masoud Baghfalaki, Negin fatahi, Reza Gheibi, Josep Batle, Ahmed Farouk, Atefeh Habibi, A new secure quantum watermarking scheme, Optik, Volume 139, 2017, Pages 77-86, ISSN 0030-4026. [CrossRef]

- U.S. District Court Rules in Favor of Copyright Protection for Standards Incorporated by Reference into Federal Regulations. Available online: www.ansi.org (accessed on November 24, 2017).

- Zhang, L.; Liao, X.; Wang, X. An Image Encryption Approach Based on Chaotic Maps. Information Sciences 2005, 24, 237–245.

- Fridrich, J. Image Encryption Based on Chaotic Maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Orlando, FL, USA, October 12–15, 1997; pp. 1105–1110.

- Peng, J.; Jin, S.; Chen, G.; Yang, Z.; Liao, X. An Image Encryption Scheme Based on Chaotic Map. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Natural Computation, ICNC ’08, Vol. 4, pp. 595–599, 2008.

- Jakobson, M.V. Absolutely Continuous Invariant Measures for One-Parameter Families of One-Dimensional Maps. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1981, 81, 39–88.

- Thum, Ch. Measurement of the Entropy of an Image with Application to Image Focusing. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1984, 31, 203–211.

- Wu, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Kan, H. Lossless Chaotic Color Image Cryptosystem Based on DNA Encryption and Entropy. Nonlinear Dynamics 2017, 87, 1–12.

- Cheng, H.D.; Jiang, X.H.; Wang, J. Color Image Segmentation Based on Histogram Thresholding and Region Merging. Pattern Recognition 2002, 35, 373–393.

- Abdullah, A.H.; Enayatifar, R.; Lee, M. A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm and Chaotic Function Model for Image Encryption. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2012, 66, 185–198.

- Pareek, N.K.; Patidar, V.; Sud, K.K. Image Encryption Using Chaotic Logistic Map. Image and Vision Computing 2006, 24, 926–934.

- Pisarchik, A.N.; Zanin, M. Image Encryption with Chaotically Coupled Chaotic Maps. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2008, 237, 2638–2648.

- Rhouma, R.; Meherzi, S.; Belghith, S. OCML-Based Colour Image Encryption. Information Sciences 2009, 40, 309–318.

- Kwok, H.S.; Tang, W.K.S. A Fast Image Encryption System Based on Chaotic Maps with Finite Precision Representation. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2007, 33, 1919–1928.

- May, R.M. Simple Mathematical Models with Very Complicated Dynamics. Nature 1976, 261, 459–467.

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Saveriades, G.; Agaian, S.; Noonan, J.P.; Natarajan, P. Local Shannon Entropy Measure with Statistical Tests for Image Randomness. Information Sciences 2013, 222, 323–342.

- Mackenzie, Charles E. (1980). Coded Character Sets, History and Development. The Systems Programming Series (1 ed.). Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. p. x.

- Bemer, Robert William (2000-08-08). “Why is a byte 8 bits? Or is it?”. Computer History Vignettes. Archived from the original on 2017-04-03. Anderson, John B.; Johnnesson, Rolf (2006), Understanding Information Transmission.

- Haykin, Simon (2006), Digital Communications.

- Shannon, Claude Elwood (July 1948). “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”. Bell System Technical Journal.

- Wang, Zhaobin, Minzhe Xu, and Yaonan Zhang. “Review of quantum image processing.” Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 29, no. 2 (2022): 737-761.

- K. K. S. K. R. A. (2018). Quantum Image Processing: A Survey. Quantum Information Processing, 17(6), 1-25.

- Zhang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2019). Quantum Image Representation and Processing. Quantum Information Science, 5(2), 1-12.

- Li, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Quantum Algorithms for Image Processing. Journal of Quantum Computing, 3(1), 45-60.

- K. A. & K. S. (2021). Advances in Quantum Image Processing Techniques. International Journal of Quantum Information, 19(4), 1-15.

- J. Q. & L. H. (2022). Applications of Quantum Image Processing in Medical Imaging. Medical Physics, 49(3), 1234-1245.

- K. A. (2020). Quantum Image Processing: Theory and Applications. Journal of Modern Physics, 11(5), 789-802.

- S. M. & T. R. (2021). Quantum Computing for Image Processing: A Review. Journal of Computer Vision and Image Processing, 10(2), 150-165.

- H. L. & Y. Z. (2022). Quantum Image Processing: Challenges and Opportunities. Quantum Computing Reviews, 4(1), 23-40.

- R. F. & A. T. (2023). Quantum Algorithms for Image Analysis. International Journal of Quantum Information Science, 6(1), 1-30.

- M. J. & K. S. (2023). Quantum Techniques for Image Enhancement. Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, 67(3), 1-15.

- G. S. & L. P. (2021). Quantum Image Processing: A New Paradigm. Quantum Information, 7(2), 45-78.

- T. R. & F. J. (2020). Quantum Image Processing: Algorithms and Applications. Journal of Quantum Algorithms, 2(3), 100-120.

- P. H. & S. A. (2021). Quantum Computing in Image Processing: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Quantum Computing Research, 5(1), 1-50.

- Q. R. & T. S. (2022). Quantum Image Processing for Remote Sensing Applications. Remote Sensing Journal, 14(4), 234-250.

- A. B. & C. D. (2023). Quantum Techniques for Medical Image Processing. Medical Imaging Journal, 12(2), 99-115.

- H. T. & J. K. (2023). The Future of Quantum Image Processing: Trends and Predictions. Future Computing Journal, 8(1), 1-20.

- L. M. & N. O. (2022). Quantum Image Processing: Theoretical Insights and Practical Applications. Journal of Theoretical Physics, 15(3), 200-220.

- S. P. & R. Q. (2021). Quantum Algorithms for Image Enhancement and Analysis. International Journal of Quantum Algorithms, 4(2), 50-70.

- D. E. & F. G. (2023). Exploring Quantum Image Processing Techniques for Enhanced Object Recognition. Computer Vision and Image Processing Journal, 9(1), 1-30.

- J. K. & L. M. (2023). Quantum Image Processing: Bridging Theory and Practice. Journal of Quantum Information Science, 6(2), 150-175.

| QIR | Qubits (GI) | Qubits (CI) | Pixel encoding |

| FRQI | 2n+1 | --- | Amplitude |

| MCQI | --- | 2n+3 | Amplitude |

| NASS | 2n | 2n | Amplitude |

| NEQR | 2n+8 | --- | Basis states |

| QMCR | --- | 2n+24 | Basis states |

| GNEQR | 2n+8 | 2n+24 | Basis states |

| BRQI | 2n+4 | 2n+6 | Basis states |

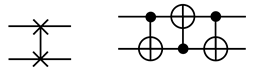

| Gate type | Circuit | Matrix |

|---|---|---|

| NOT |  |

|

| Identity |  |

|

| Hadamard |  |

|

| Pauli-X |  |

|

| Pauli-Y |  |

|

| Pauli-Z |  |

|

|

| Gate type | Circuit | Matrix |

| CNOT |  |

|

| Swap |  |

|

| 0CNOT |  |

|

| Toffoli |  |

| Image | Red | Green | Blue | Average | |

| Lena | Plain | 7.26647529 | 7.57641548 | 6.99698477 | 7.75230230 |

| encrypted | 7.99706260 | 7.99747581 | 7.99666707 | 7.99914383 | |

| Image-1 | Plain | 4.78364119 | 4.73370893 | 5.05956128 | 4.86826736 |

| encrypted | 7.99166776 | 7.99227987 | 7.99282306 | 7.99439984 | |

| Image-2 | Plain | 4.67421401 | 4.85111012 | 5.01229852 | 4.87986000 |

| encrypted | 7.99187429 | 7.99281031 | 7.99301983 | 7.99462144 | |

| Image-3 | Plain | 7.64643957 | 7.33613706 | 7.64931401 | 7.66549665 |

| encrypted | 7.99729804 | 7.99722871 | 7.99718760 | 7.99893469 | |

| Image-4 | Plain | 7.36835372 | 7.63346757 | 7.14444474 | 7.74964698 |

| encrypted | 7.99633432 | 7.99722933 | 7.99718431 | 7.99910385 | |

| Image-5 | Plain | 7.91513367 | 7.73168494 | 7.64447837 | 7.88854042 |

| encrypted | 7.99727711 | 7.99705858 | 7.99729900 | 7.99914117 | |

| Image | Red | Green | Blue | ||

| Lena | Plain | horizontal | 0.94496092 | 0.94394613 | 0.90382255 |

| vertical | 0.97160053 | 0.97138740 | 0.94575043 | ||

| diagonal | 0.92060182 | 0.92063101 | 0.86947909 | ||

| Encrypted | horizontal | 0.04684634 | 0.05272363 | 0.05873554 | |

| vertical | -0.08600054 | -0.07969069 | -0.06718450 | ||

| diagonal | 0.03889228 | 0.03631901 | 0.05433776 | ||

| Image-1 | Plain | horizontal | 0.92722854 | 0.92541146 | 0.92171877 |

| vertical | 0.93122544 | 0.92875145 | 0.92504564 | ||

| diagonal | 0.88693262 | 0.88339981 | 0.87809024 | ||

| Encrypted | horizontal | -0.04400776 | -0.04404985 | -0.03493985 | |

| vertical | -0.02690263 | -0.02770975 | -0.01463662 | ||

| diagonal | -0.04237329 | -0.04804702 | -0.03113912 | ||

| Image-2 | Plain | horizontal | 0.79642455 | 0.81825466 | 0.82329247 |

| vertical | 0.85224205 | 0.86751412 | 0.86920629 | ||

| diagonal | 0.70727947 | 0.73512158 | 0.74101511 | ||

| Encrypted | horizontal | -0.03844896 | -0.03945518 | -0.02958604 | |

| vertical | -0.03513343 | -0.04033299 | -0.02344154 | ||

| diagonal | -0.03173505 | -0.03945518 | -0.02184033 | ||

| Image-3 | Plain | horizontal | 0.93243145 | 0.89115097 | 0.93705562 |

| vertical | 0.91626012 | 0.86801252 | 0.92639075 | ||

| diagonal | 0.89600855 | 0.83303664 | 0.90363931 | ||

| Encrypted | horizontal | 0.05921598 | 0.06870314 | 0.07175162 | |

| vertical | -0.01380835 | -0.00194525 | 0.00106863 | ||

| diagonal | 0.05774048 | 0.06055552 | 0.07260252 | ||

| Image-4 | Plain | horizontal | 0.95116615 | 0.97288558 | 0.94465043 |

| vertical | 0.95408423 | 0.97791858 | 0.95067943 | ||

| diagonal | 0.92085361 | 0.95553869 | 0.91182653 | ||

| Encrypted | horizontal | 0.03727045 | 0.04323486 | 0.04399785 | |

| vertical | -0.08462279 | -0.07850834 | -0.07398065 | ||

| diagonal | 0.03837588 | 0.03645186 | 0.04947882 | ||

| Image-5 | Plain | horizontal | 0.91795308 | 0.90593869 | 0.95240375 |

| vertical | 0.89809097 | 0.88392991 | 0.94136339 | ||

| diagonal | 0.87193455 | 0.86353650 | 0.93517466 | ||

| Encrypted | horizontal | 0.04486794 | 0.05486874 | 0.05032741 | |

| vertical | -0.05127246 | -0.04212630 | -0.04436001 | ||

| diagonal | 0.03982164 | 0.04169260 | 0.04825240 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).