1. Introduction

Circulating Vaccine-derived polioviruses Type 2 (cVDPV2) can arise from Sabin strain poliovirus serotypes 1, 2, and 3 found in the oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) after extended person-to-person transmission [

1]. When population vaccination immunity against polioviruses is suboptimal, sustained transmission can result in viral genetic changes that trigger a reversion to neurovirulence and clinical disease identical to that caused by wild poliovirus [

2]. Vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPCs) are divided into multiple categories: The viruses are first classified as cVDPVs when community circulation is confirmed (i.e., an outbreak) [

3]. They are also called immunodeficiency-associated (iVDPVs) if isolated from individuals with primary immunodeficiency [

4]. Lastly, ambiguous (aVDPVs) is a classification of exclusion when not associated with immune deficiency or community circulation when detected through Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) or Environmental Surveillance (ES) [

5].

Environmental surveillance in Jigawa State, Nigeria, first detected a single cVDPV2 emergence (named JIS-1) in January 2018. During the reporting period, the strain was later found in 12 other states in Nigeria and abroad [

6]. The first half of 2019 saw the discovery of isolates genetically connected to JIS-1 from environmental surveillance samples and AFP cases, first in Niger and then in Benin, Cameroon, and Ghana [

7].

In 2020, about 27 countries worldwide reported 959 human cases of cVDPV2 and 411 cVDPV2-positive environmental samples; 21 of these countries were in Africa, and the remaining six were in the Eastern Mediterranean, European Union, and Western Pacific regions [

8]. Compared to 2019, when 366 cVDPV2 cases and 173 cVDPV2-positive environmental samples were recorded, there were more cVDPV2 cases and environmental samples in 2020 [

9]. Since 2017, numerous genetically different cVDPV2 outbreaks have been reported in multiple African countries [

10,

11]. The current epidemic of cVDPV2 affects about twenty-one countries: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, and Togo. Outbreak response activities are being carried out in these countries [

9]. In March 2024, Sierra Leone confirmed the presence of a poliovirus variant 3 in the Kambia District and a type two variant in sewage near the Mabella sawmill bridge in the Western Area Urban District [

12].

In response to the latest cVDPV outbreak, which started on the 10th of March 2024, a national novel Oral Polio Vaccine (nOPV) campaign planned in the 16 districts to be synchronized with five countries in the West African subregion (Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia, Burkina Faso, and Mali). The first round was conducted from the 10th – 13th May 2024.

The Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) of the Ministry of Health carried out several additional vaccination campaigns in the wake of the nOPV synchronized mass vaccination campaign. Measles, COVID-19, Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), and malaria vaccine introduction were among the immunization campaigns carried out before the response to the cVDPV outbreak.

The documented evidence of the success of immunization activity in the face of many other immunization efforts in Sierra Leone is scanty. Also, there is an absence of research that evaluates the quality of administrative data on polio vaccination against the Lot Quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) performance tool, as well as community acceptance of the nOPV campaign and cross-border vaccination coverage. Thus, such information is important to evaluate the success of large-scale nOPV campaign activity in Sierra Leone.

Therefore, our study generally looked at the success of such activity in the face of many other immunization efforts by the Ministry of Health. Specifically, the study assessed the quality of administrative data against the LQAS performance, the community acceptance of the nOPV campaign, cross-border vaccination coverage, and the quality of supervision of the campaign.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Population: Sierra Leone is a country located in West Africa, with a population of over 8 million people [

13]. There are 328,710 surviving infants. The country confirmed the cVDPV2 isolation through environmental surveillance on January 8, 2024 [

14]. An Environmental Sample (ES) was collected in one of the five ES sites in Sawmill Bridge, Mabella, Freetown. The laboratory result was received on March 8, 2024, which was positive,

virus type 2, EPID No, ENV-SIL-WEA-WAU-MSB-MSB-24-001. These isolates were genetically linked to an outbreak in Nigeria. The outbreak was reported to WHO, HG, on March 9, 2024. It was declared a National Public Health Emergency on the 22

nd May 2024

. The Ministry of Health conducted the first nationwide supplementary immunization activity with nOPV2 in May 2024 to reach eligible children with two doses, targeting 1,584,140 children aged 0-59 months.

Study Design: This study employs descriptive secondary data analysis of the nationwide novel Oral Poliovirus (nOPV) vaccination campaign conducted in response to the 2024 cVDPV2 outbreak in Sierra Leone.

2.1. Pre-Campaign Activities

Coordination of the response: The country declared the cVDPV2 outbreak in March 2024. The Ministry of Health, in collaboration with its partners, set up an emergency operation centre (EOC) to guide and coordinate the response. The EOC formed different response pillars, including surveillance, risk communication, case management, contact tracing, and vaccine pillars. The vaccine pillar was assigned to the EPI program, which planned and coordinated the nOPV2 campaign in collaboration with its partners. The vaccination pillar formed six technical working groups: Leadership, Coordination and Finance, Vaccine Logistics and Supply Chain, Service Delivery Training and Human Resources, Monitoring and Evaluation, Advocacy Communication and Social Mobilization, and Vaccine Safety Surveillance. All pillars had their separate meeting, planning, and reporting to the Incident Manager at the EOC daily.

Readiness Assessment: To assess the national program and district readiness for the campaign, there were five rounds of readiness assessment conducted at both national and district levels. The country reviewed the WHO readiness assessment tool and adapted it to the country’s context.

Training: Training materials were developed for training healthcare workers under six topics. The included Polio epidemiology, nOPV2 vaccine characteristics, management and Supply chain, Vaccination Strategy and administration, Roles and Responsibilities of supervisors, Performance Monitoring, Risk Communication, Social Mobilization, and Vaccine Safety Surveillance. The training was conducted at different levels, starting with National Training of Trainers (nTOT), District and chiefdom supervisors training, and vaccinators training. One week of integrated training was conducted for implementation, with two days each for national, district, and chiefdom supervisors and one day for vaccinators.

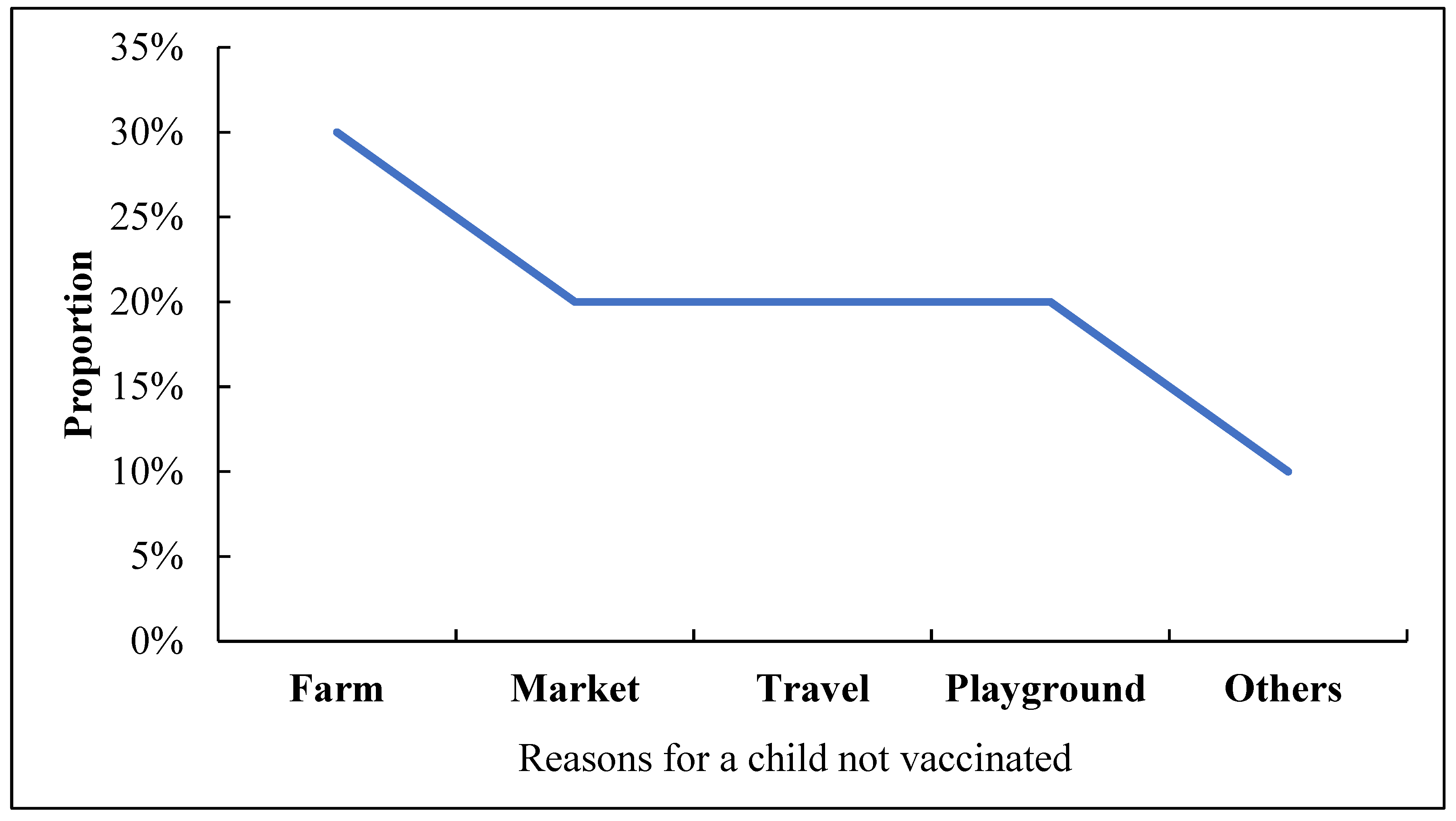

Advocacy Communication and Social Mobilization: To minimize vaccine hesitancy and missed opportunities, robust community and stakeholder engagement meetings were held across all districts. Different media platforms, including radio, TV spots, and social media, were used to sensitize caregivers and create demand for the campaign. Rapid Refusal Resolution Teams (RRRT) were set up in all districts to promptly respond to all refusal cases. Members of the RRTs were drawn from key influencer people within the community.

Vaccination Teams: 4,043 vaccination teams were allocated to all 16 districts based on the approved budget, geography, and special population of the districts (special team) by the EPI program. The training was conducted for all staff and partners deployed for implementing and supervising the nOPV round one activity, including vaccinators, vaccine accountability monitors, and supervisors. A total of 9,102 Vaccinators & Mobilizers, 356 Team supervisors, 230 Chiefdom supervisors, 160 District supervisors, 84 National supervisors and 10 Regional supervisors. The trainings were conducted at national, district, and chiefdom levels.

A total of 80 independent Monitors and 20 LQAS surveyors were also trained to validate the campaign. The teams were allocated to the district and then to health facilities within their districts. Each vaccination team comprised a vaccinator, a recorder, and a social mobilizer. At least two teams were allocated to every health facility. Each vaccination team had a daily target of 100 for rural and 150 for urban.

2.2. Intra-Campaign Activities

Vaccine Management: The nOPV2 vaccine was distributed to all health facilities based on their target population identified in the health facility micro plan. Before the implementation, a cold chain assessment was done to determine the gaps in the CCE requirements. Health facilities without functional CCEs were supplied with vaccine cold boxes lined with adequately conditioned ice packs during the campaign. On the field, every team was assigned a vaccine carrier lined with coolant packs to keep the vaccine in the correct temperature range (+2 to +8 0C). Because of the dangers associated with the use of the nOPV2 vaccine in the environment, Vaccine Accountability Monitors were recruited to ensure every vaccine vail was accounted for.

Vaccination Strategy and Administration: The campaign was conducted across the 16 districts, delivering vaccines to eligible children and communities using House-to-House, Fixed, and Transit vaccination strategies. While most eligible children were vaccinated in the households by the house-to-house teams, special or transit teams were assigned to border crossing points, lorry parks, marketplaces, places of worship, schools, etc., to ensure that children who were missed in the households were vaccinated. At the same time, fixed teams were assigned to the health facilities to vaccinate eligible children who would visit the health facilities for other interventions during the campaign period. Supervisors were allocated to monitor the day-to-day vaccination processes—four teams to a supervisor in rural areas and five teams to a supervisor in urban settlements. National, regional, district, chiefdoms, and team supervisors were deployed to monitor the vaccination exercise. Four days of supervision were conducted to monitor the implementation across all districts. Also, daily debriefings were conducted in all districts either at 7 am – 9 am or evening from 4:30 pm to 7 pm. The meeting provides a platform for supervisors to discuss issues of the day and make action points with the responsible person to act on them before the next day's work. This serves as a corrective means of the problem faced in the field while supervising the implementation so that the intended goal is met by all districts. The national debriefing meeting starts at 8 pm, where regional, national, and districts give updates from their district to the EPI program. To discuss the day's activity implementation, make action points or recommendations for the next day. A National situation room was formed to support and coordinate the activities at the national level. Head of units were drawn to constitute the situation room.

Data collection and reporting: During the nOPV2 campaign, administrative data were collected at different levels. The Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E), Technical Working Group (TWG), in collaboration with Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partners, designed and pre-tested the data collection and reporting tools. At the vaccination team level, vaccinators used tally sheets to record the number of children vaccinated for the day.

Administrative data was collected using tally sheets and an electronic-based (Open Digital Kit (ODK) to record the number of children vaccinated each day. The tally sheets consist of the number of children who received the nOPV in each age category, both zero dose and one or more doses, refusals and revisits were used during the implementation phase. Thus, administrative coverages were available day by day. Aggregated vaccination data is summarized by the team supervisors in the daily team vaccination summary sheet and submitted to the chiefdom supervisor. The chiefdom supervisors summarized the summaries from all health facilities within the chiefdom in the Daily Chiefdom Summary Form. The chiefdom supervisors submitted the daily summary form to the district Monitoring and Evaluation Officer, who summarized the data by chiefdoms in the district Excel-linked file. The Excel-linked file was uploaded to Google Drive so that the national M&E team and partners could access the data as they were entered at the district levels. The linked file had a summary sheet and data analysis sheet used at the national level to inform decision-making.

Supportive Supervision: Supportive Supervision exercises were conducted at all implementation levels during the campaign. At the team and health facility levels, one team supervisor was assigned to five teams. At the chiefdom level, each chiefdom had at least one chiefdom supervisor who supported all health facilities within his or her chiefdom. In addition to the district-level supervisors, there were three national supervisors assigned to each district. A supportive supervision checklist was developed by the World Health Organization, which was uploaded to ODK for data collection. All supervisors used the ODK mobile app to collect data during the campaign.

2.3. Post-Campaign Activities

Post-vaccination assessment monitoring was done using the clustered-LQAS campaign evaluation; the survey was conducted two days after the nOPV2 campaign. All 16 districts were selected. In each district, we randomly selected six chiefdoms and a community (village or neighbourhood) in each chiefdom. In each community, ten children were surveyed (one per household). Next, the first household was randomly selected in the cluster according to existing geographical landmarks: the locality map was drafted, divided into smaller sectors according to existing landmarks (streets, playgrounds, rivers, etc.), and randomly selected one industry where the most central household was chosen to start the survey [

15]. In the selected household, caregivers were interviewed for the nOPV2 vaccination status of their children, and all eligible children were selected. Children were checked for finger markings and household markings.

2.4. Lot Quality Assurance Survey

Definition: For the clustered LQAS survey, health districts in Sierra Leone were defined as ‘lots.’ Also, an individual vaccinated against polio is defined as a child between 0 and 59 months presenting an indelible ink mark on the fingernail at the time of nOPV vaccination.

Since our objective was a clustered LQAS for the nOPV vaccination, a two-day survey was implemented after the mopping up and the last day of the campaign was confirmed. For the nOPV antigen, 60 eligible individuals were interviewed per lot (district) for vaccination status, each lot was divided into six clusters of 10. In each district, six chiefdoms were randomly selected. Communities (villages or neighbourhoods) were randomly selected in each chiefdom. In each community, 10 (one per household) children were surveyed.

Next, the first household in the cluster was randomly selected according to geographic random sampling: a map of the locality was drafted and divided into four smaller units according to existing landmarks (streets, rivers, etc.) and randomly selected one sector which is the most central household to start the survey [

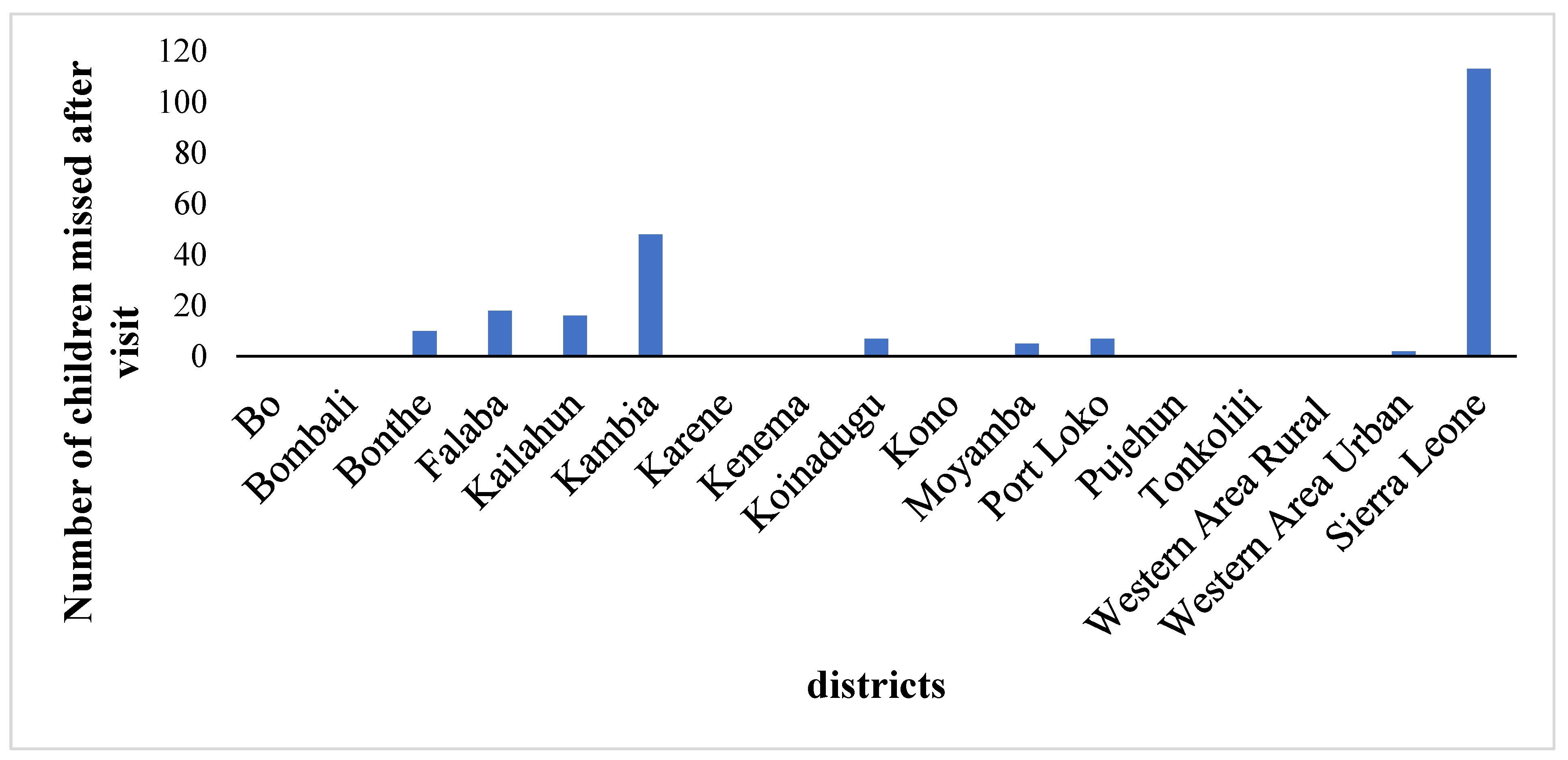

16]. Also, during the campaign, independent monitors were employed to ascertain the quality of administrative data and ensure children missed during the campaign were vaccinated, especially in areas vaccinators have covered. The independent monitors were instructed to participate in the daily vaccination campaign debriefing meetings at the district level and discuss daily findings with health officers and supervisors. The purpose of these meetings was to interpret all information from the field to guide supervisors and strengthen areas of attention.

2.5. Planning the Clustered LQAS Surveys in the Field

The LQAS surveying team planned the nOPV post-vaccination campaign evaluation in collaboration with the Expanded Program on Immunization-Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization. The campaign implementation team was fully aware of the purpose of the LQAS surveys. Independent surveyors were sent across all the selected 16 districts after the nOPV vaccination exercise to evaluate the quality of the administration data reported during the campaign.

Definition of key variables: The following operational definitions were used

ZD: Zero-dose children were defined as those children aged between 0-59 months at the time of the survey who had not received any dose of the novel oral polio vaccine.

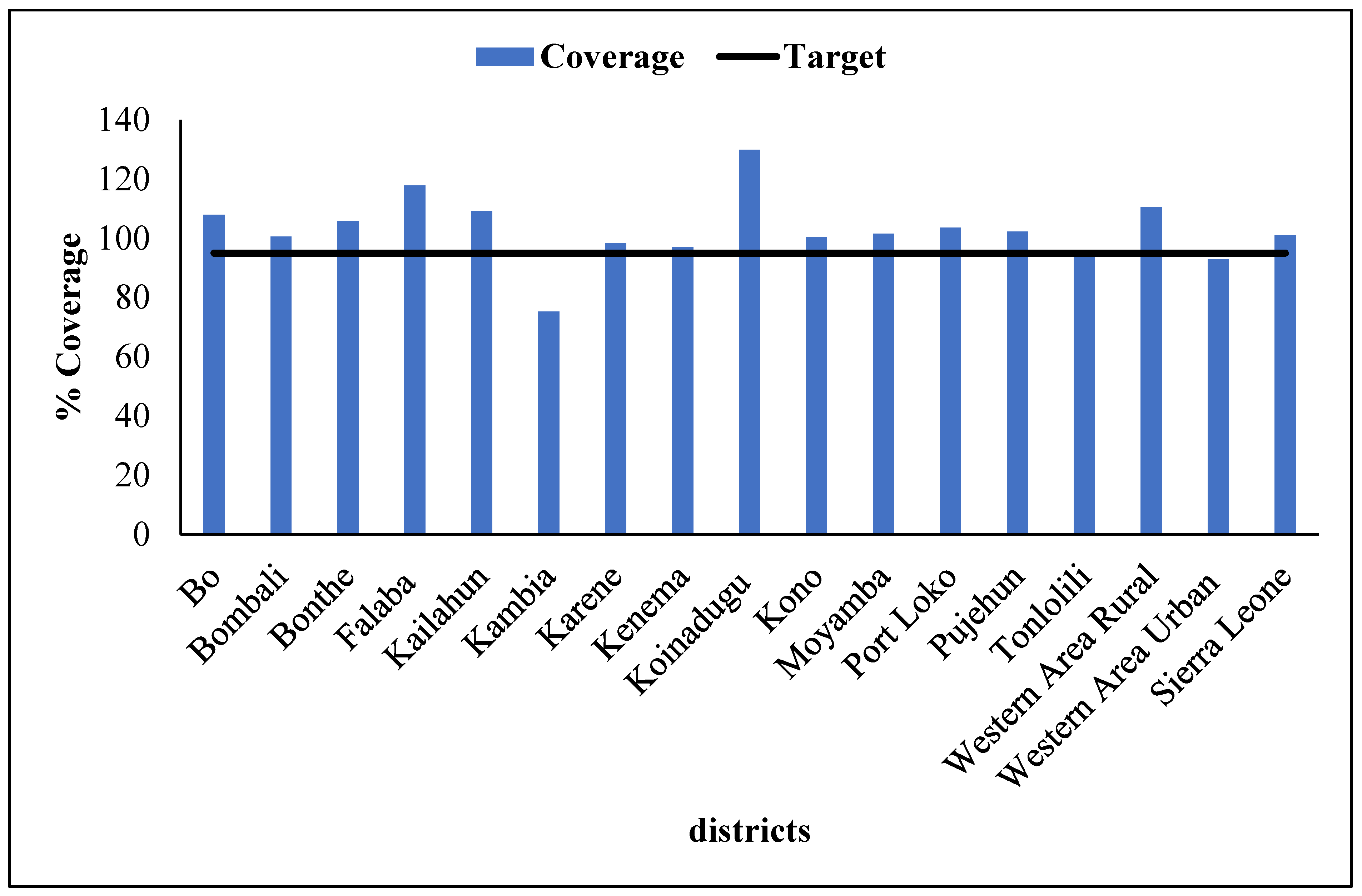

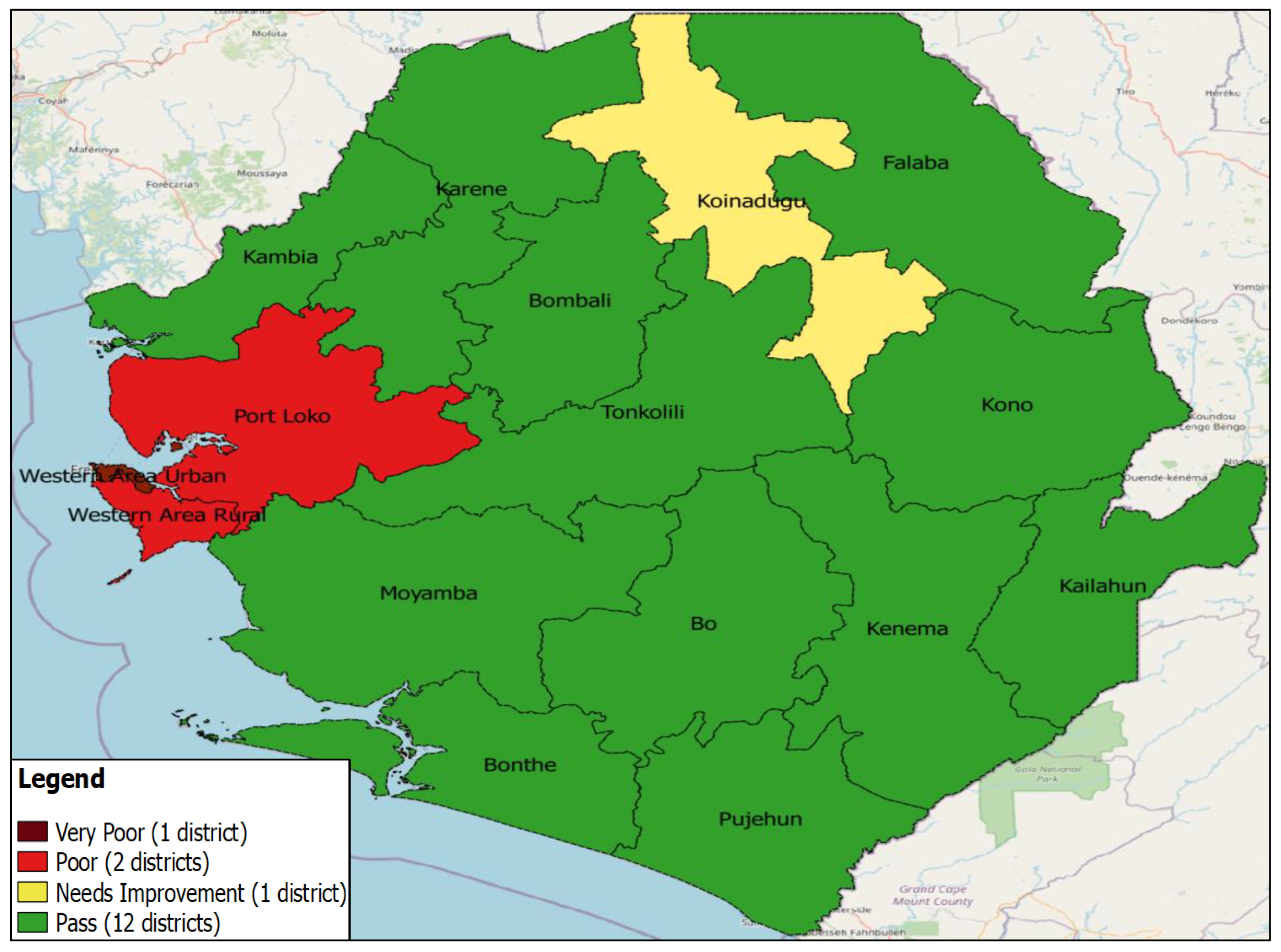

Vaccination Indicators: < 4 children missed during the nOPV campaign are characterized as high Supplementary Immunization Activity (SIA) performance, and no action is required as districts in this category are considered to have achieved high-quality campaign performance, and ≥four children missed were categorised as suboptimal SIA performance.

2.6. Data Analysis

The administrative data were analysed using STATA version 18 and Power-Bi software, and statistical calculation for the clustered LQAS data was analysed using Excel. We entered the campaign data and analysed it with Excel. To take corrective action based on objective information, during the campaign, any individual not presenting proof of vaccination is considered unvaccinated, i.e., those without finger markings. Also, children in streets and schools were not sampled during LQAS activity. The impact of the measures taken following the outcomes of the clustered LQAS on nOPV administrative coverage was analyzed. Districts' nOPV administrative data with LQAS findings were compared. The community acceptance of the nOPV campaign, cross-border vaccination coverage, and the quality of supervision of the campaign. Data were represented on graphs and tables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: DMK, ENS, AKK, SL, NCK, manuscript acquisition: ENS, DMK, AKK, SL, NCK, and HB; Methodology: DMK, ENS, AKK, SL, and NCK, formal analysis: SL, AKK, and ENS, writing review and editing: DMK, AKK, PBJ, AN, AC, ENS, HB, JMK, EGS, MTMK, and TS; Visualization, DMK, AKK, SL, HB, and ENS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in this article.