1. Introduction

Endosymbiotic bacteria are common in arthropods, with over 50% of species infected, primarily via maternal inheritance [

1,

2]. Endosymbiotic bacteria have co-evolved with their hosts, influencing host's nutrition, digestion, resistance, and defense against predators, thereby play critical role in host colonization and ecological evolution in specific habitats [

3,

4]. At present, the most studied secondary endosymbionts including

Wolbachia,

Cardinium,

Rickettsia,

Spiroplasma, are known to manipulate the host reproductive and developmental processes by inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility, male-killing, parthenogenesis, heat resistance and drug resistance in their hosts [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Wolbachia is a maternally transmitted gram-negative bacteria found in arthropods. The host range of

Wolbachia is extremely wide, and approximately 65% of insect species naturally carry this endosymbiont.

Wolbachia is abundantly present in insect ovaries and testes, and is also distributed in non-reproductive tissues such as head, muscles, midgut, salivary gland, Malpighian tubules, hemolymph and fat body of insects [

9,

10]. The regulatory effects of

Wolbachia on its host has always been a hot topic in

Wolbachia-related research. Currently, the documented

Wolbachia's reproductive regulation of the host include cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), male-killing, feminization and parthenogenesis etc. CI is the most common reproductive regulation induced by

Wolbachia, which refers to the phenomenon where mating between

Wolbachia-infected male and uninfected female insect results in either no or few offspring. In addition, some strains of

Wolbachia can also affect the host's sense of smell, lifespan, immunity, nutrition, fertility and developmental processes etc [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Rickettsia is an intracellular symbiotic bacteria that spreads and cause diseases in humans and animals, and is also a secondary endosymbionts existing in insects.

Rickettsia, gram-negative bacteria belongs to the family

Rickettsiaceae in the α subgroup of

Proteobacteria. It is widely distributed in nature, and its hosts include vertebrates, arthropods, annelids, amoebas, ciliates, hydrozoans and plants [

7]. Research has found that

Rickettsia and its host insects have a mutualistic symbiosis and are co-evolved.

Rickettsia can affect the reproductive behavior of their host by inducing male-killing, parthenogenesis, and also has an impact on the fitness of the host insects [

8,

15,

16,

17,

18].

In nature, co-infection of arthropod hosts by different symbiotic bacteria is quite common. The impacts of multiple infection on the host may be cumulative [

19]. The interactions between co-infecting symbiotic bacteria may lead to reproductive phenotypes that are completely different from those seen in singly infected hosts. If co-infection confers a higher fitness than single infection, it can be stably maintained within the host population [

20].

Rickettsia and

Wolbachia sometimes co-infect arthropods. However, little research has been conducted on the interactions between these two bacteria [

2,

21,

22,

23,

24], and studies on co-infections have only focused on the expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility, while the impact of co-infection of these two bacteria on host reproduction has not been reported.

Tetranychus turkestani (Ugarov et Nikolski) is an important agricultural pest, which is distributed in Russia, Kazakhstan, United States, Middle East, and in Xinjiang, China [

25,

26]. This spider mite reproduces rapidly, has a short generation cycle, and is the dominant pest in the cotton fields in northern Xinjiang. Various endosymbiotic bacteria are present in this mite, including

Wolbachia,

Cardinium,

Rickettsia, etc [

27]. In this study, we compared the different hybridization types of four different infected strains of

Tetranychus turkestani (double-infected

Rickettsia and

Wolbachia strain I

WR, single-infected

Rickettsia strain I

R, single-infected

Wolbachia strain I

W and double-uninfected strain I

U), and investigated the effects of

Wolbachia and

Rickettsia on the host and their interaction. These results will further enhance our understanding of the reproductive manipulation induced by the co-infection of symbiotic bacteria in arthropods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Rearing of Spider Mites

The Tetranychus turkestani were collected in 2019 from the experimental field of the College of Agriculture, Shihezi University in 2019. Since then, they have been reared within a light incubator at the Insect Physiology Laboratory of the College of Agriculture, Shihezi University, under controlled conditions (25 ℃, a photoperiod of 16 hours of light and 8 hours of darkness, and a relative humidity of 60%). The mites were fed on Phaseolus vulgaris L. throughout the rearing process, with no exposure to any pesticides.

2.2. Detection of Infections by Different Symbiotic Bacteria

Extraction of total DNA: 25 μL of STE buffer (100 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, pH = 8.0) was added to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube. A single spider mite was picked with an insect needle and placed in the tube, then thoroughly crushed with a plastic pestle. Subsequently, 2 μL of proteinase K (10 mg/mL) was added. The mixture was centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 2 min, incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, then heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and centrifuged again at 3000 rpm for 2 min. 2 μL of the supernatant was used as the template for PCR amplification.

Primers were designed using the Beacon Designer 7 software to detect whether Tetranychus turkestani was infected with Wolbachia and Rickettsia (see Appendix Table A2 and Table A5).

2.3. Establishment of Strains Infected with Different Endosymbiotic Bacteria

Establishment of a strain co-infected with Wolbachia and Rickettsia: A complete and fresh kidney bean leaf was put in a Petri dish with sponge (9 cm diameter), and was divided into four approximately equal chambers using moistened cotton strips according to the leaf size. Unmated female mites were selected in the static III state from the laboratory strain and were placed individually into each chamber for parthenogenesis. When the offspring developed into adult male mites, the mother was backcrossed with her male offspring. After two days of backcrossing, the mother was transferred to a new chamber for oviposition. After seven days, perform PCR was performed to detect the mother. These above steps were repeated for five generations with the offspring of the female mites with co-infection of Wolbachia and Rickettsia, and then 30 of them were selected for PCR detection of the infection rates of Wolbachia and Rickettsia. Once all were infected, a strain co-infected with Wolbachia and Rickettsia was obtained.

The experimental strains with single infection of Rickettsia and single infection of Wolbachia were obtained using the same method.

Establishment of a completely uninfected strain of Tetranychus turkestani: A complete and fresh kidney bean leaf were soaked in a 0.2% tetracycline solution for 24 hours and then placed into a 9 cm diameter Petri dish with sponge. Moist cotton strips were placed around the bean leaf to prevent the spider mites from escaping. Newly hatched Tetranychus turkestani larvae (unfed, nearly white) were selected and placed on the leaf, where they were allowed to grow and reproduce naturally. Distilled water was added daily to the Petri dish to maintain the moisture of the sponge, and the leaf were replaced with a fresh one in a timely manner. Once the larvae matured, about 30 individuals were selected for PCR detection of Wolbachia and Rickettsia infections. If no infections was detected, the offspring of this strain were continuously cultured, to obtaining an experimental strain uninfected with Wolbachia and Rickettsia.

Nomenclature of spider mite strains: IW represented the strain singly infected with Wolbachia, IR represented the strain singly infected with Rickettsia, IWR represented the strain co-infected with Wolbachia and Rickettsia, and IU represented the uninfected strain. F stands for female, and M stands for male. Tetranychus turkestani can be abbreviated as T. turkestani.

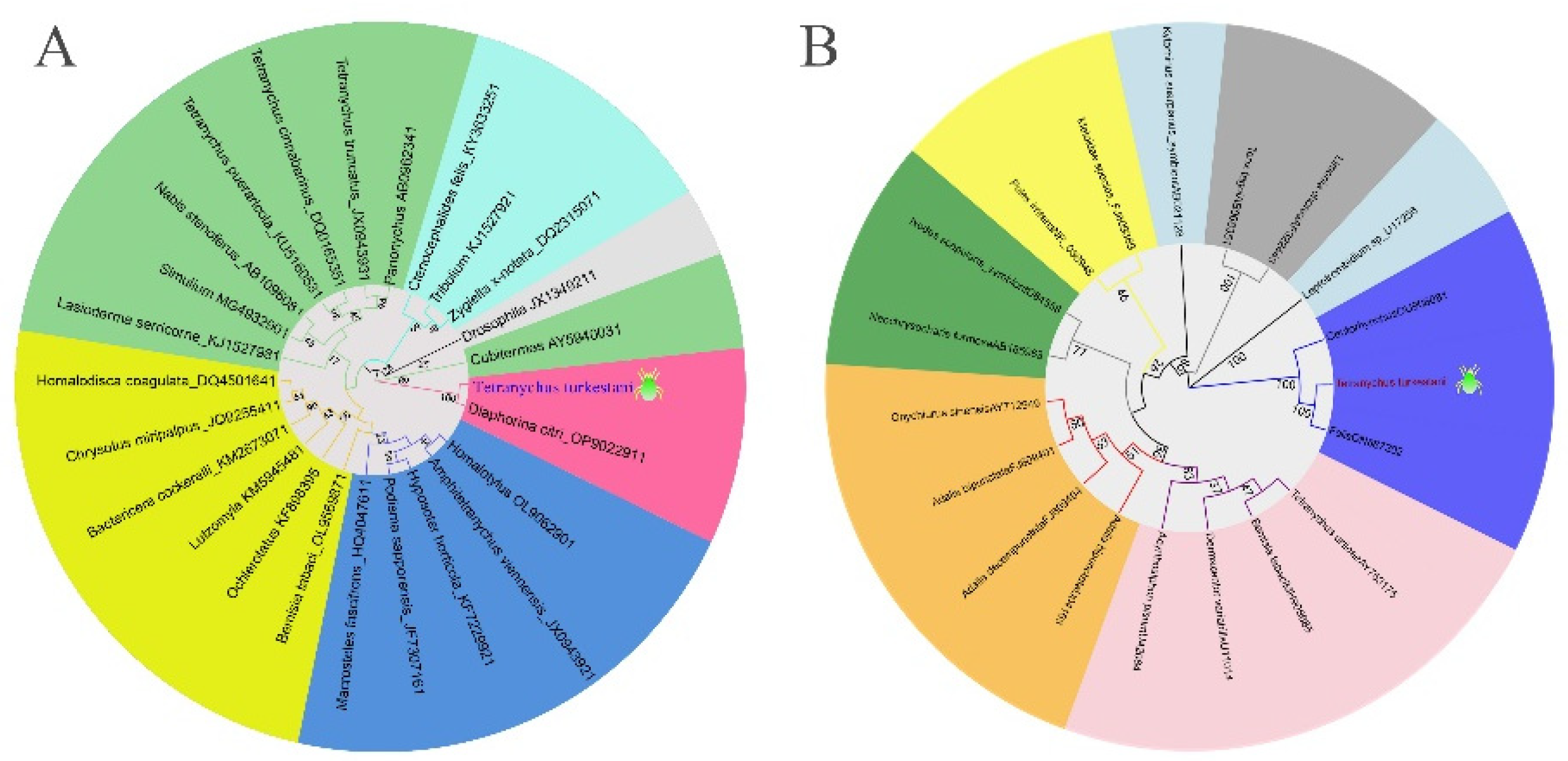

2.4. Wolbachia and Rickettsia Phylogenetic Tree Construction

The wsp sequence of Wolbachia and the gltA sequence of Rickettsia (see Appendix Table A2 , Table A3 and Table A4) were used in the PCR. PCR amplification products were detected using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and positive results were further purified using gel recovery, and then the purified products were sent to Youkang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for bidirectional sequencing. Sequences of Wolbachia wsp and Rickettsia gltA from different species were searched and downloaded from the NCBI database. ClustaIW sequence alignment was performed using MEGA11, and an NJ (Neighbor - joining) phylogenetic tree was constructed. Bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates was conducted.

2.5. Detection of the Maternal Inheritance Efficiency of Wolbachia and Rickettsia

The maternal inheritance efficiency of the symbiotic bacteria Wolbachia and Rickettsia was determined by measuring the infection rates of the two bacteria in the male offspring from parthenogenesis of single female mites or the female offspring of sexual reproduction of single pairs of Tetranychus turkestani. The parthenogenetic offspring of IW, IR, and IWR female mites, the bisexual reproductive offspring of IW female mites and IU male mites, the bisexual reproductive offspring of IR female mites and IU male mites, and the bisexual reproductive offspring of IWR female mites and IU male mites were selected respectively. Using the primers for Rickettsia gltA and Wolbachia wsp, the infection status of Rickettsia and Wolbachia was detected by PCR. A total of 10/50 female mites were randomly selected (since the number of parthenogenetic offspring of IR female mites is relatively small, 50 IR female mites were selected) to determine whether they undergo arrhenotokous parthenogenesis or bisexual reproduction. Subsequently, 10/2 male or female offspring from each female mite were tested, with a total of 100 offspring individuals in each group. Based on the PCR amplification results, the infection rates of Wolbachia and Rickettsia were calculated.

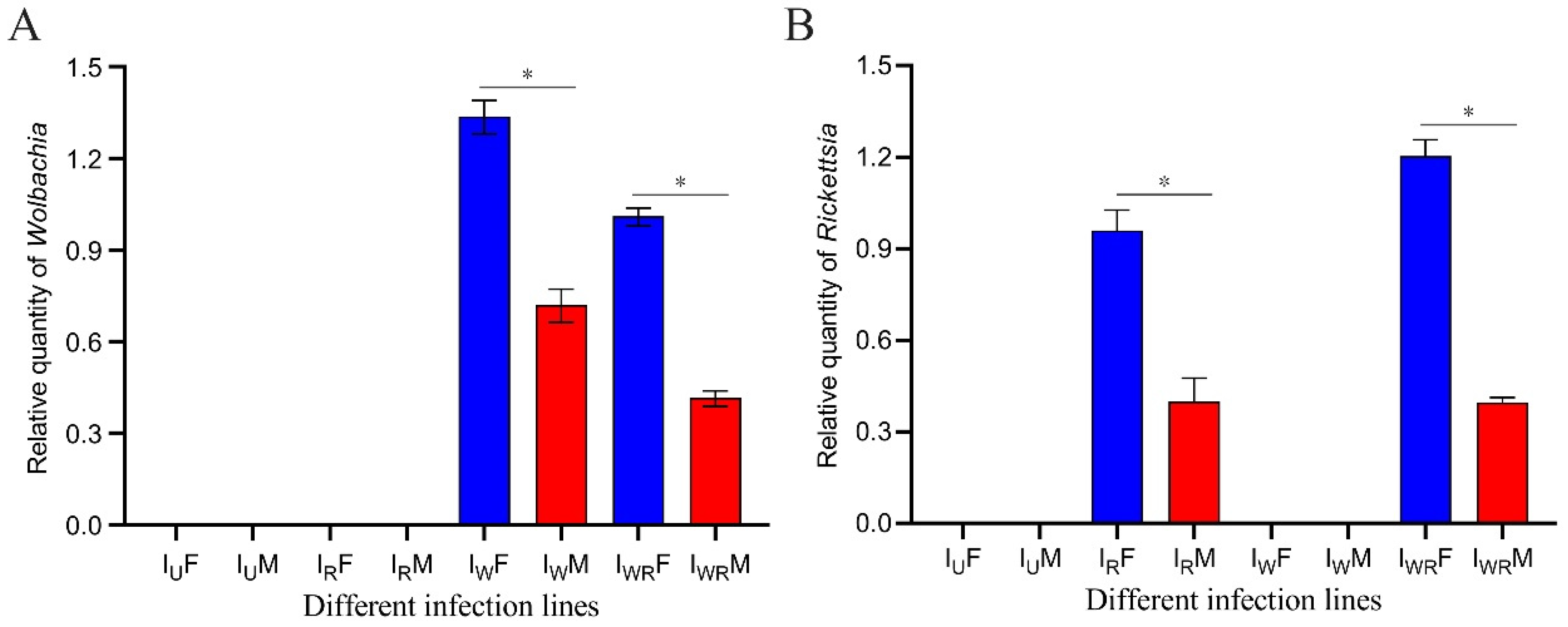

2.6. Detection of the Titers of Wolbachia and Rickettsia in Tetranychus turkestani

Based on the

gltA gene sequence of

Rickettsia and the

wsp gene sequence of

Wolbachia, specific quantitative primers were designed to detect the titers of

Rickettsia and

Wolbachia in

Tetranychus turkestani. The

RPSI8 reference gene was selected as an internal control for data standardization and quantification [

28](see Appendix Table A5, A6, A7). Adult male and female mites from different infected strains were quantified, with 200-300 individuals per group constituting one replicate, and the experiment was repeated three times. The quantitative PCR (qPCR) reactions were performed on ABI Prism 7500 qPCR instrument. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 seconds; 95°C for 5 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, 40 cycles. To verify the specificity of the qPCR products, a melting curve (95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute, 95°C for 15 seconds) was conducted at the end of the reaction. Three technical replicates were performed for each sample. A negative control was set for each reaction. The titer data of

Wolbachia and

Rickettsia in

Tetranychus turkestani were analyzed using SPSS software, and the expression levels were calculated by the 2

-ΔΔCt method. The statistical significance analysis was performed using Student's t test.

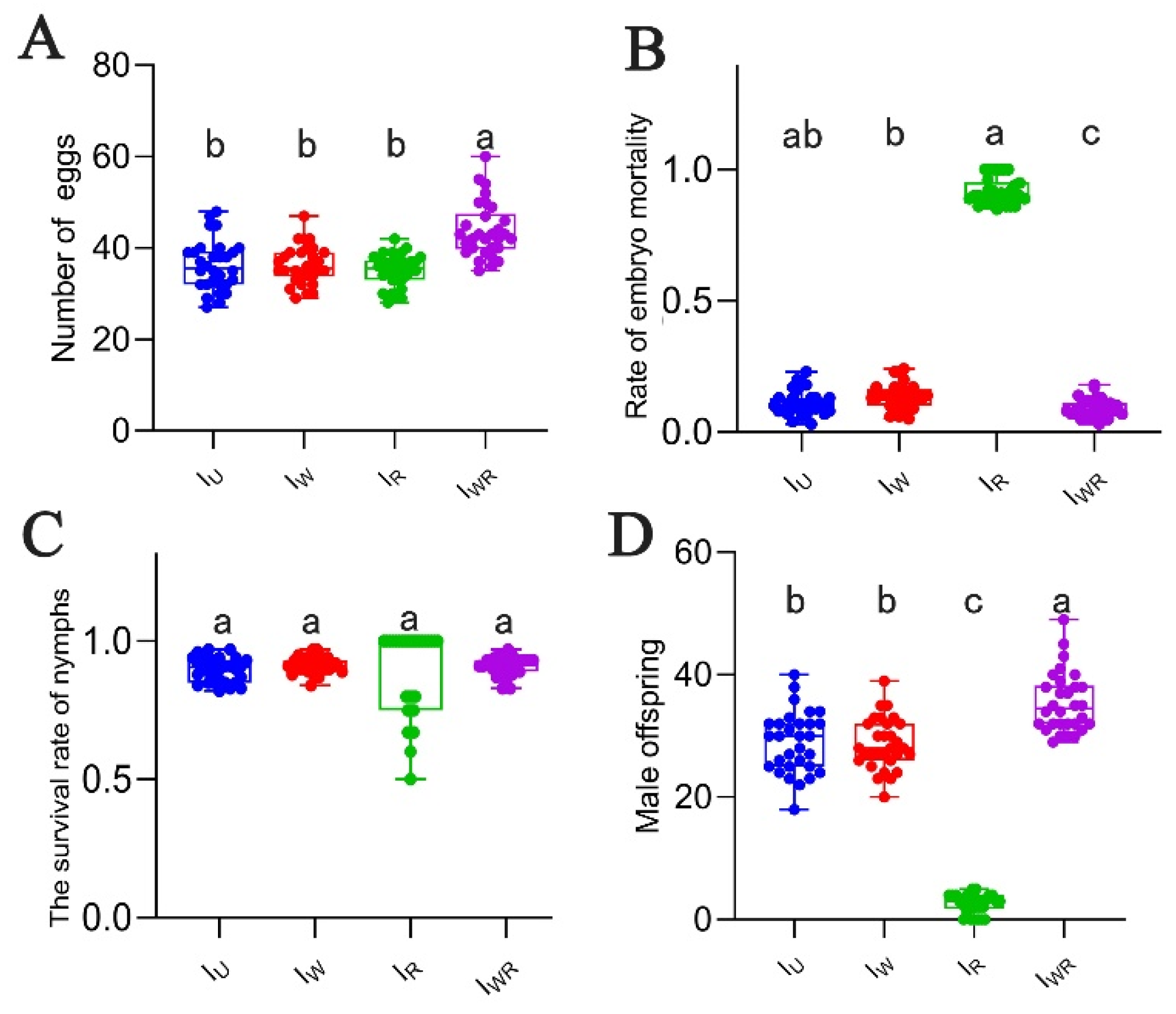

2.7. Effects of Different Symbiotic Bacteria Infections on the Fecundity of Tetranychus turkestani

Parthenogenesis: Fresh kidney bean leaves were taken and each leaf was divided into four circular sections with an area of approximately 4 cm² each. Single female mites in the static III stage with different infection statuses were selected and placed onto each section of the leaf. Number of eggs laid were counted daily and the counting was started from the first day the female mite begins to lay eggs. After laying eggs for five consecutive days, the female mite was removed. The daily egg-laying count and the total number of eggs laid were recorded. Once the eggs hatch into larvae, the hatching rate was recorded and when they develop into adult mites, the sex ratio (female/male) was noted.

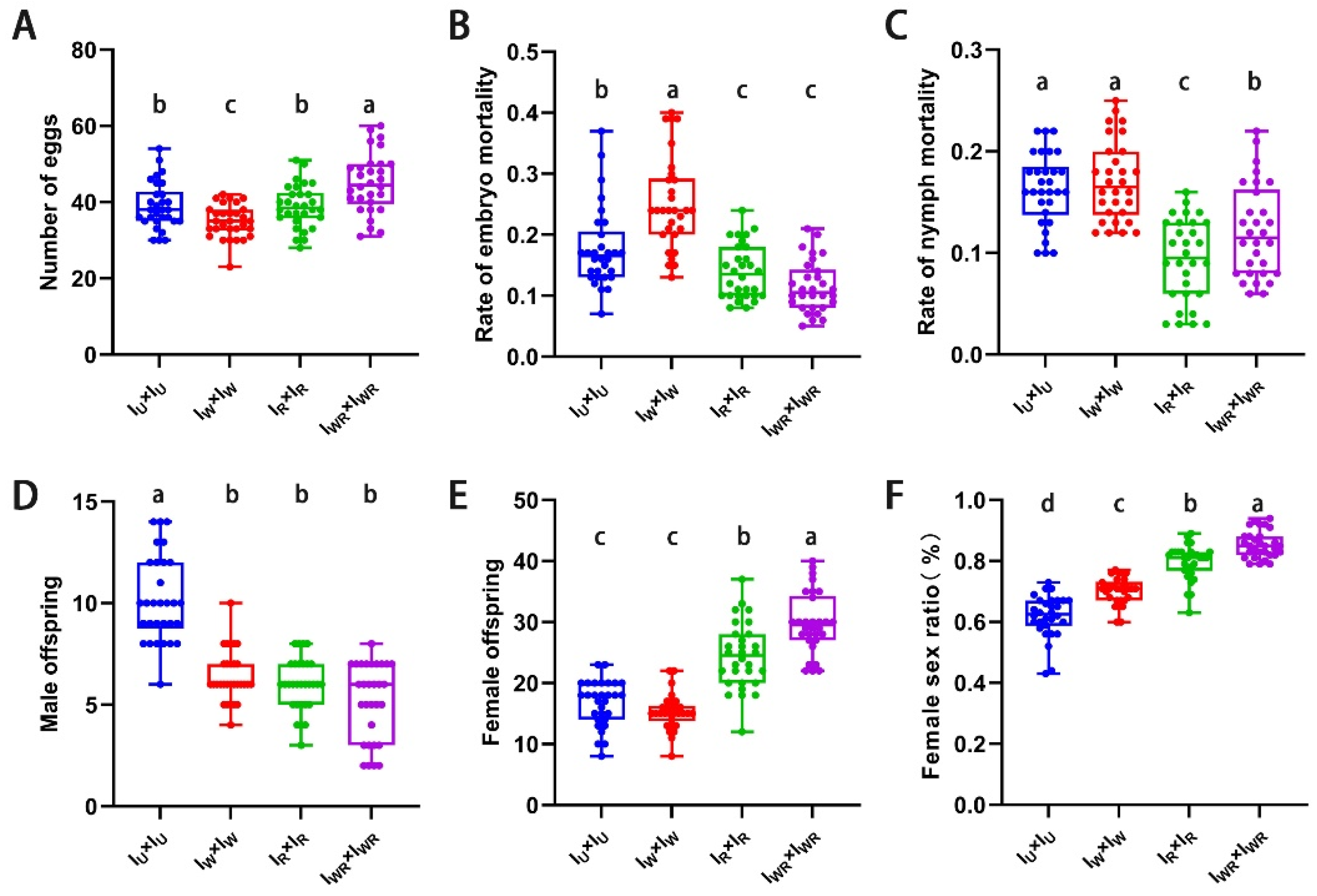

Sexual reproduction: Four different strains of

Tetranychus turkestani were selected using different crossbreeding combinations to conduct hybridization experiments. Fresh leaves were taken and divided each leaf into four circular sections, each approximately 4 cm². A single female and male mite in the static III stage with different infection statuses were placed together in each section of the leaf, with one pair per section. Two days after the female molted into a mature adult, the male was removed. Starting from the first day of egg-laying, the female mites were removed after laying eggs for five days. Daily egg-laying count and total eggs laid were recorded. After the eggs hatched into larvae, the hatching rate was recorded, and the sex ratio (female/male) was noted once the mites reached adulthood. If the parental male adult mite died before the female mite starts laying eggs, it was promptly replaced with another male adult mite. If the parental female adult mite died before completing five days of egg laying, the data for that pair was discarded. The CI level (CI%) was calculated using the formula: CI% = (1−F /FC) × 100, where F represnts the number of female offspring from incompatible crosses (♀Iu×♂I

W, ♀Iu×♂I

WR), and FC is the average number of female offspring from the control cross (♀Iu×♂I

U) [

29]. The embryonic mortality (EMs) of different

Tetranychus turkestani strains (parthenogenetic individuals or sexually reproducing individuals) was calculated using the formula EM = TE-HE, where TE is the total number of eggs in a single cross, and HE is the number of hatched eggs. The post embryonic mortality (PEM) of each crossbreeding combination (♀I

U×♂I

WR, ♀I

U×♂I

W) was calculated using the following formula: PEM% = (1–AO/HE )×EM, where AO is the number of adult offspring in a single cross [

30].

The above experiments were repeated 30 times. Under a microscope, the number of eggs laid by a single female mite or each pair of parents was counted, and the number of embryonic deaths and nymph deaths was recorded. Adult mites were collected for gender identification.

2.8. Data Processing

A one-way analysis of variance (SPSS 26.0) was used to compare the outputs of arrhenotokous parthenogenesis and bisexual reproduction in the IWR, IW, IR, and IU strains, and to analyze the cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) function of Wolbachia in the IWR and IW strains. Pairwise comparisons of all variables were performed using Duncan's multiple range test. Independent samples t-tests (SPSS 26.0, P<0.05) were employed to analyze the infection titers of Wolbachia and Rickettsia in Tetranychus turkestani of different genders in the IWR, IW, and IR strains, to compare the outputs of arrhenotokous parthenogenesis and bisexual reproduction in the IWR, IR, and IW strains, and to analyze the impact of male killing induced by Rickettsia on the CI function induced by Wolbachia. Graph Pad software was used for graphing.

4. Discussion

In this study, different strains of Tetranychus turkestani infected with different endosymbiotic bacteria (Wolbachia and Rickettsia) were examined, and phylogenetic analysis was carried out. The results showed that the Wolbachia infected Tetranychus turkestani belonged to supergroup B and can induce cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) in the host. The transmission efficiency of Wolbachia and Rickettsia were statistically analyzed. The results revealed that, regardless of parthenogenesis or sexual reproduction, both symbiotic bacteria completely follow maternal transmission. Real- time quantitative PCR was used to determine the titers of the endosymbiotic bacteria. The results showed significant differences in the abundance of Wolbachia and Rickettsia between male and female adult mites.

Rickettsia is a maternally inherited symbiotic bacterium. In some hosts, it acts as a nutritional symbiont, while in others, it influences the host reproduction through reproductive regulations such as parthenogenesis induction and male killing. It can also enhance the host resistance to pesticides and improve the host ability to resist to predators, high temperatures, or other lethal factors [

3,

4,

16,

17,

31,

32,

33,

34]. To date, no experimental studies have investigated the reproductive regulation of this bacterium in mites. Our research demonstrated that

Rickettsia infected spider mite resulted in parthenogenesis producing only male offspring, but the hatching rate of male embryos was extremely low. Sexual reproduction in

Rickettsia singly infected mites produced both female and male offspring, with increased number of female offspring than male, resulting in a high female to male sex ratio. This indicated that

Rickettsia infection leads to a male - killing phenotype.

Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is the most common reproductive regulation induced by

Wolbachia, typically occurs in two forms. The first form is characterized by high embryonic mortality rate, resulting in a decrease number of female offspring, which is called female lethality. The second form does not decreased the total number of offspring, but results in an increase in the number of male offspring, known as male development. Both female lethality and male development induced by

Wolbachia may occur simultaneously in a single insect host, such as the

Wolbachia wLhetl strain in parasitic wasps [

35,

36]. In this study, sexual reproduction of

Tetranychus turkestani (♀I

U×♂I

W) significantly increased the mortality rates of embryos and nymphs, and significantly decreased the female to male sex ratio, which belongs to the female lethality type.

Wolbachia singly-infected in

Tetranychus turkestani induced strong CI.

Currently, research on the interaction between

Rickettsia and

Wolbachia is limited, especially regarding the impact of

Rickettsia and

Wolbachia co-infection on the reproductive regulation of host insects, which has not yet been reported. In this study, we found that the

Rickettsia and

Wolbachia co-infection induced cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) in

Tetranychus turkestani, but the intensity was much weaker than that induced by single-infection of

Wolbachia. This may be because the male killing effect of the

Rickettsia in co-infection reduced the CI level induced by

Wolbachia. Subsequent hybridization experiments clearly demonstrated an antagonistic interaction between the male killing effect of

Rickettsia and the CI induced by

Wolbachia. Previous studies have shown that there are two types of

Wolbachia in nature: one that maintains a high prevalence in insect host and weakly induces CI, such as

Wolbachia in

Drosophila melanogaster [

37]; the another that induces strong CI but maintains a low prevalence and titer, like

Wolbachia in

Drosophila melanogaster [

38]. The

Wolbachia in

Tetranychus turkestani studied here was most similar to the former. Furthermore, compared with the control group (I

U×I

U) without symbiotic bacteria infection, the

Rickettsia-

Wolbachia co-infection had a higher fecundity, lower mortality, a higher female to male ratio, and more offspring. In conclusion, the synergistic effect of the two symbiotic bacteria significantly improved the fitness of

Tetranychus turkestani.

In conclusion, our study revealed five findings (

Figure 10):

Rickettsia infection induced male-killing effect in the sexual reproduction of

Tetranychus turkestani;

Rickettsia infection caused the death of parthenogenetically produced male embryos in

Tetranychus turkestani, leading to a reduction in the number of offspring;

Wolbachia single infection induced strong cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) in

Tetranychus turkestani, while

Rickettsia-Wolbachia co-infection induced weaker CI; the male killing effect induced by

Rickettsia antagonized the strong CI induced by

Wolbachia;

Rickettsia-Wolbachia co-infection promoted the fitness of

Tetranychus turkestani, suggesting synergistic mutualistic relationship between the two symbiotic bacteria within the same host

Tetranychus turkestani. We gained a better understanding of the complex interactions between symbiotic bacteria and host, as well as between different symbionts, providing strategies and insights for future applications of symbionts in biological control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W and Y.Z.; methodology, S.W and Y.Z.; software, S.W.; validation, S.W., X.W. and A.B.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, S.W.; resources, S.W and X.W.; data curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W., Y.Z., Q.W., K.Z. and A.B.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 2.

Density of Wolbachia and Rickettsia in female and male T. turkestani of different infection strains. (A) Relative quantity of Wolbachia. (B) Relative quantity of Rickettsia. IUF: Female of the IU population, IuM: Male of the Iu population, IRF: Female of the IR population, IRM: Male of the IR population, IwF: Female of the Iw population, IwM: Male of the Iw population, IWRF: Female of the IWR population, IWRM: Male of the IWR population. The symbol “*” indicates a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.05), while “ns” represents no significant difference. All error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

Density of Wolbachia and Rickettsia in female and male T. turkestani of different infection strains. (A) Relative quantity of Wolbachia. (B) Relative quantity of Rickettsia. IUF: Female of the IU population, IuM: Male of the Iu population, IRF: Female of the IR population, IRM: Male of the IR population, IwF: Female of the Iw population, IwM: Male of the Iw population, IWRF: Female of the IWR population, IWRM: Male of the IWR population. The symbol “*” indicates a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.05), while “ns” represents no significant difference. All error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 3.

Parthenogenetic parameters of IU、IW、IR、IWR in T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) The survival rate of nymphs. (D) Male offspring. The data in the figure are average ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Parthenogenetic parameters of IU、IW、IR、IWR in T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) The survival rate of nymphs. (D) Male offspring. The data in the figure are average ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Sexual reproductive parameters of IW、IR 、IWR and IU mating in T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Male offspring. (E) Female offspring. (F) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ±standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Sexual reproductive parameters of IW、IR 、IWR and IU mating in T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Male offspring. (E) Female offspring. (F) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ±standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

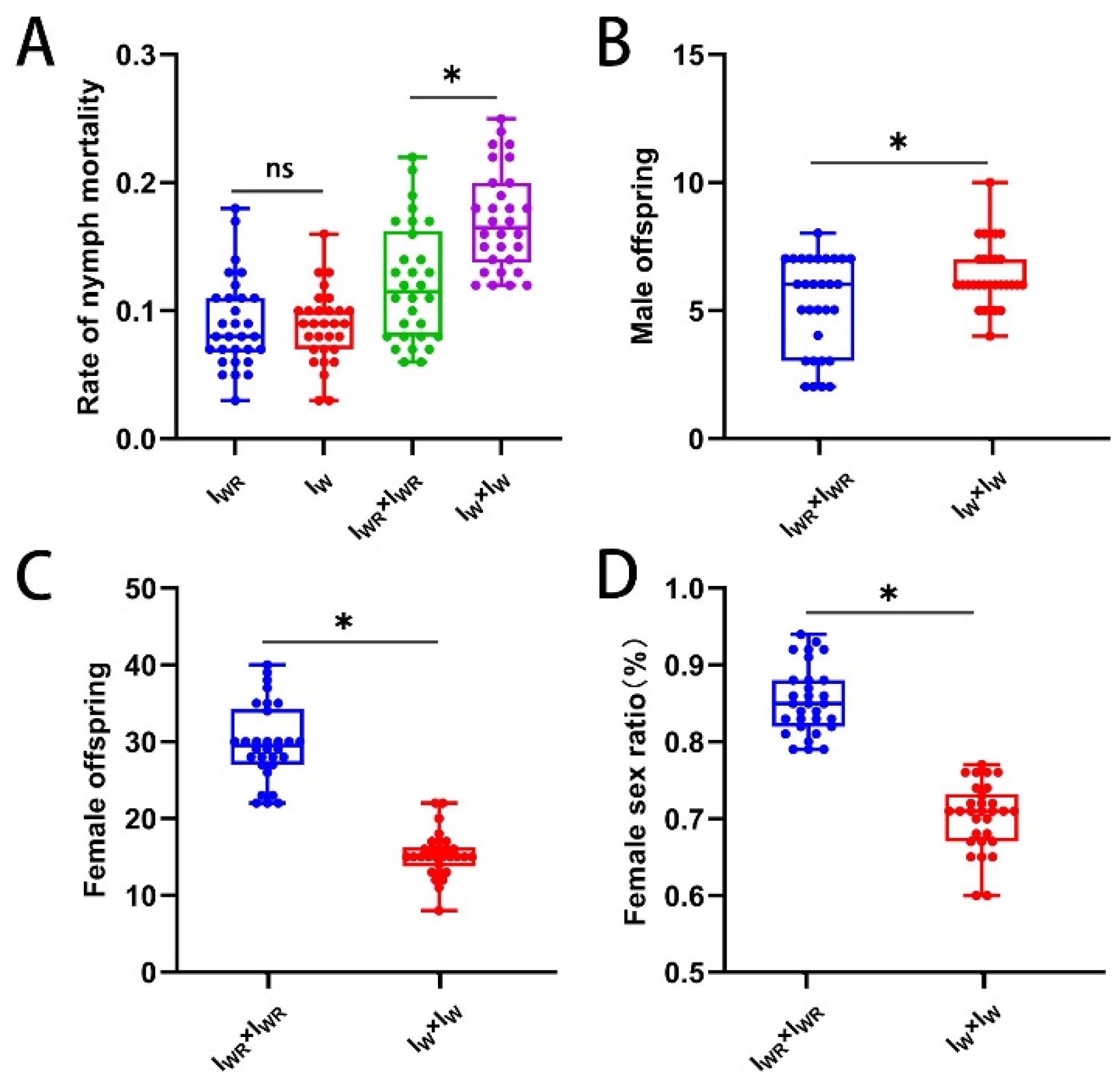

Figure 5.

Parthenogenesis and intraspecific sexual reproduction of IWR and IW in T. turkestani within 5 days of oviposition. (A) Rate of nymph mortality. (B) Male offspring. (C) Female offspring. (D) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Parthenogenesis and intraspecific sexual reproduction of IWR and IW in T. turkestani within 5 days of oviposition. (A) Rate of nymph mortality. (B) Male offspring. (C) Female offspring. (D) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

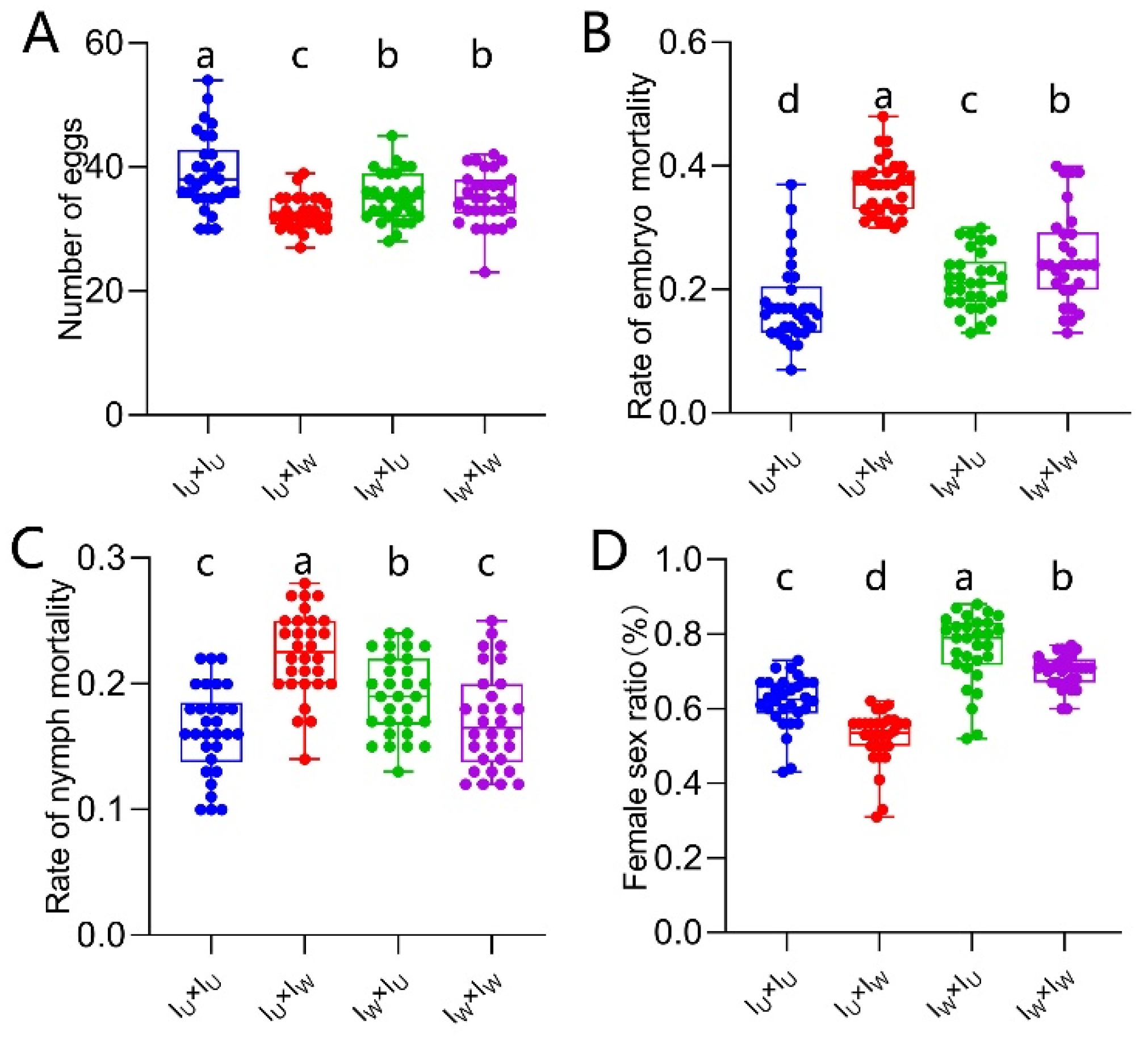

Figure 6.

CI identification of Wolbachia in Iw of T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

CI identification of Wolbachia in Iw of T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

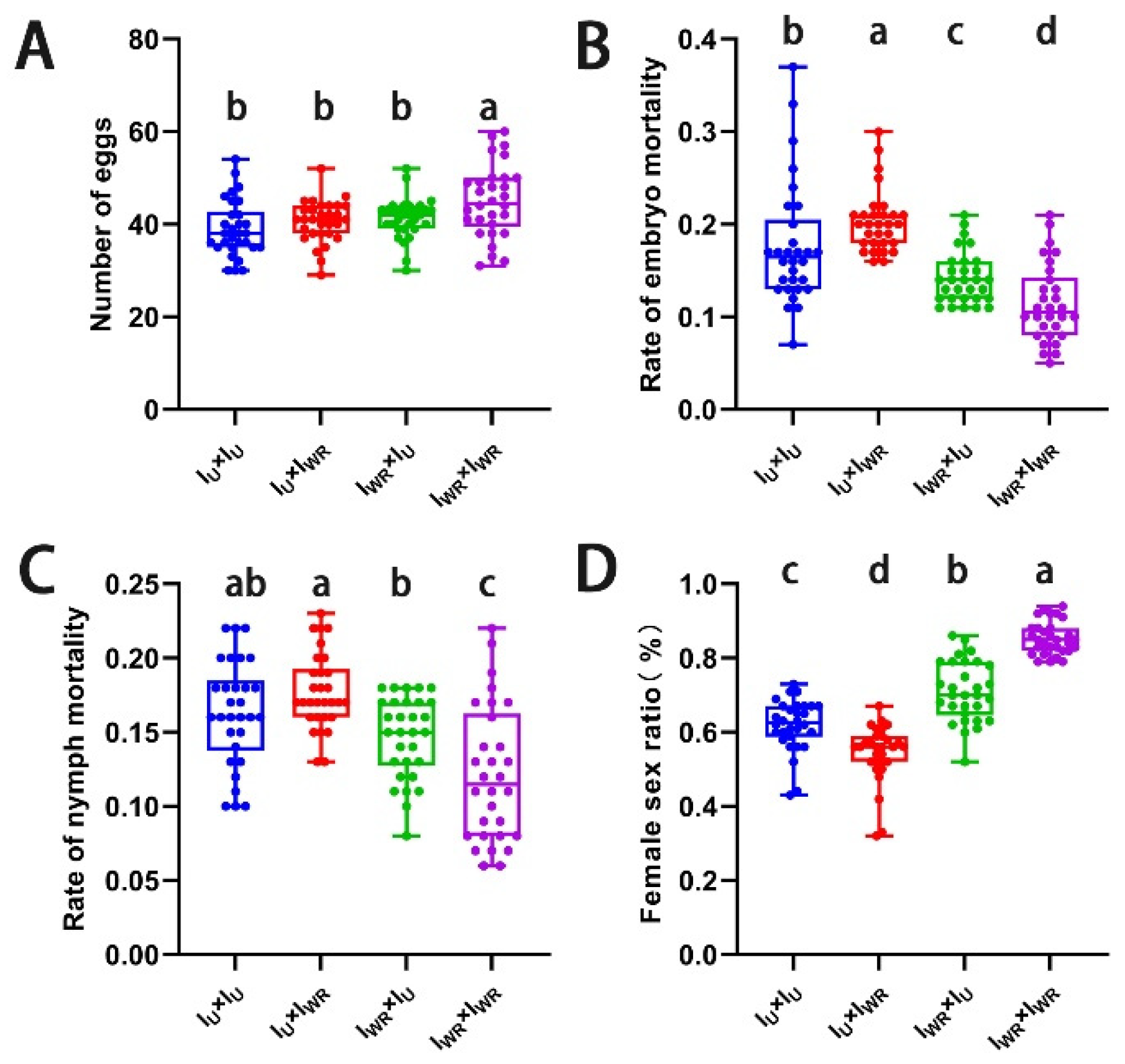

Figure 7.

CI identification of Wolbachia and Rickettsia in IWR of T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

CI identification of Wolbachia and Rickettsia in IWR of T. turkestani. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Female sex ratio. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

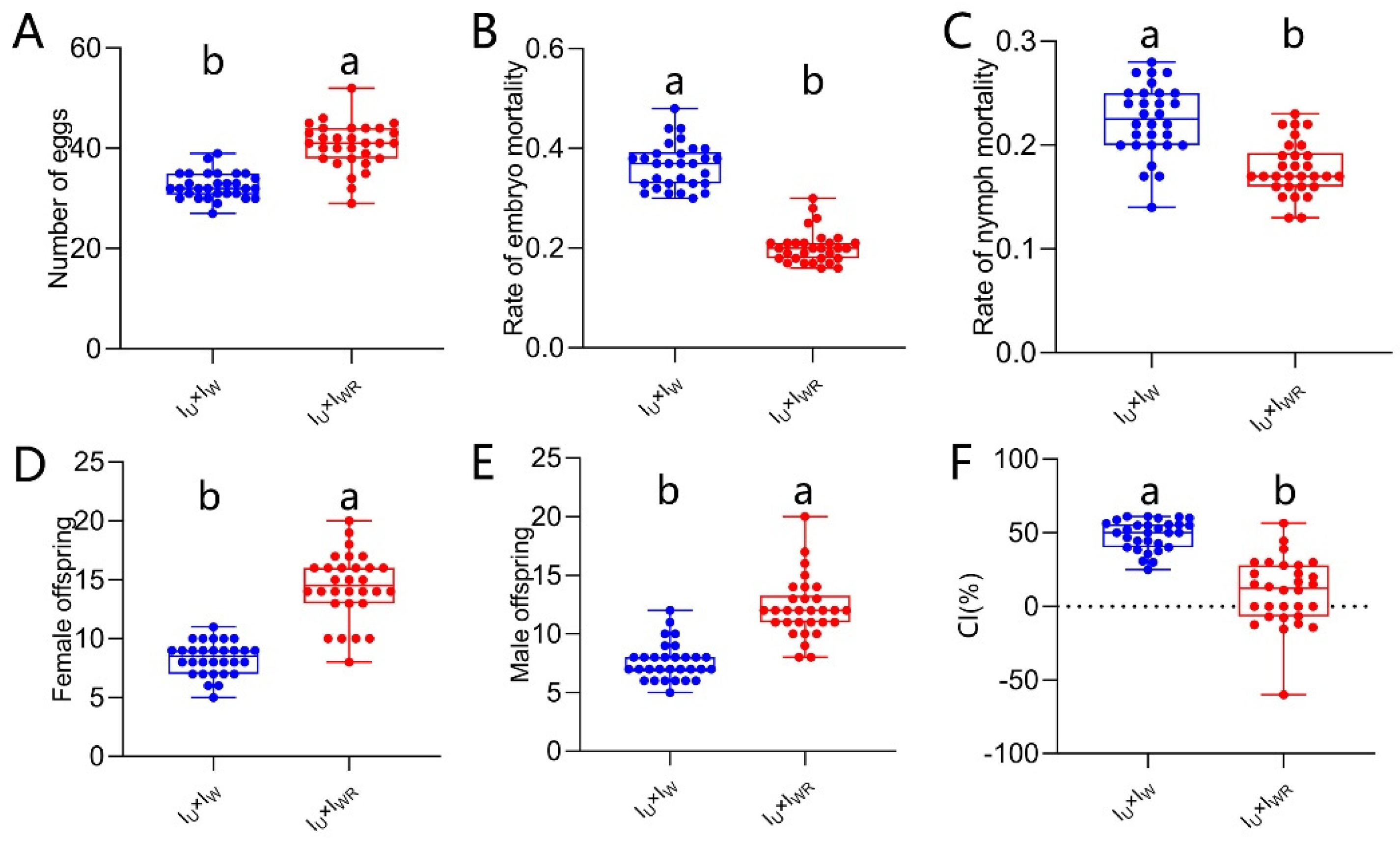

Figure 8.

Antagonistic effect of Rickettsia co-infection on CI in Wolbachia. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Female offspring. (E) Male offspring. (F) CI%. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Antagonistic effect of Rickettsia co-infection on CI in Wolbachia. (A) Number of eggs. (B) Rate of embryo mortality. (C) Rate of nymph mortality. (D) Female offspring. (E) Male offspring. (F) CI%. The data in the figure are mean ± standard error; The mean values of different letter markers were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

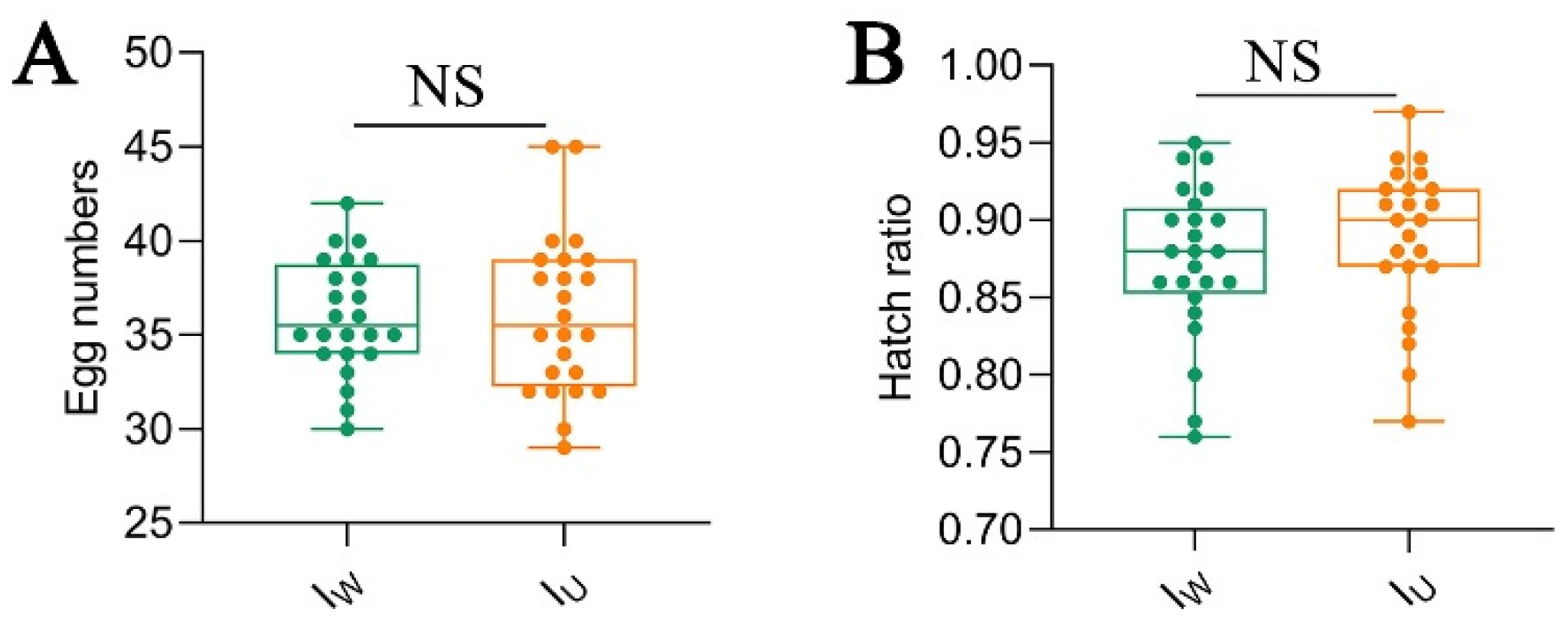

Figure 9.

The reproductive parameters of different combinations of T. turkestani. (A) Egg production of IW and IU in parthenogenesis. (B) Hatching rate of IW and IU in parthenogenesis. IU,Wolbachia-uninfected;IW,Wolbachia-infected. Crossing combinations of strains are shown as‘Female×Male’. The data in the figure are presented as mean ± standard error; means marked with different letters indicate a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

Figure 9.

The reproductive parameters of different combinations of T. turkestani. (A) Egg production of IW and IU in parthenogenesis. (B) Hatching rate of IW and IU in parthenogenesis. IU,Wolbachia-uninfected;IW,Wolbachia-infected. Crossing combinations of strains are shown as‘Female×Male’. The data in the figure are presented as mean ± standard error; means marked with different letters indicate a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

Figure 10.

The action model of Rickettsia and Wolbachia on the reproductive regulation of T. turkestani. RI: T. turkestani with single Rickettsia infection; R: Parthenogenesis with single Rickettsia infection; WCI: Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) induced by single Wolbachia infection; WRCI: Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) induced by co-infection of Wolbachia-Rickettsia; WR: T. turkestani with co-infection of Wolbachia-Rickettsia.

Figure 10.

The action model of Rickettsia and Wolbachia on the reproductive regulation of T. turkestani. RI: T. turkestani with single Rickettsia infection; R: Parthenogenesis with single Rickettsia infection; WCI: Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) induced by single Wolbachia infection; WRCI: Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) induced by co-infection of Wolbachia-Rickettsia; WR: T. turkestani with co-infection of Wolbachia-Rickettsia.