1. Introduction

There is an overarching concept in the pre-life chemical evolution of biological systems that has perhaps been neglected or incompletely expressed. That is, that biological systems initially evolved around a small number of central functional cores. For transcription systems, the central cores were two double-Ψ−β-barrel type DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, promoters and TFB in Archaea and σ factors in Bacteria [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. TFB and σ factors are homologs of one another made up of repeating helix-turn-helix motifs. Translation systems, by contrast, evolved around transfer RNA (tRNA), which is the genetic adapter [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Essentially, all life and genetic coding evolved around the functional core of tRNA.

Evolution of life on Earth required chemical coevolution of tRNAomes (all the tRNAs of an organism), aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARS), ribosomes, mRNA and a genetic code plus numerous interacting systems and molecules. This raises the question about how chemical evolution was driven by sufficiently powerful selective pressures before true cells could coalesce and commence Darwinian selection and evolution. This report addresses this question based on a history of chemical selection, written and recorded in conserved genetic code. Notably, the most central history of the pre-life to life transition on planet Earth was recorded in the sequences of tRNAs. Thus, the core story of genesis of life on Earth was chronicled in tRNA sequences.

The three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem shows how tRNA evolved chemically on pre-life Earth [

6,

10]. For replication, a 31 nt D loop minihelix of known sequence was ligated to two 31 nt anticodon/T loop minihelices of almost entirely known sequence. After processing by 9 nt internal deletion(s) within ligated acceptor stems, type II and type I tRNAs were generated. Type II tRNA was formed by a single 9 nt internal deletion in a 93 nt tRNA precursor that was a replication intermediate for 31 nt minihelices. Type I tRNA was generated by two closely related 9 nt internal deletions in the same 93 nt tRNA precursor. The two internal 9 nt deletions to form type I tRNA were identical to one another on complementary RNA strands. An early version of type II tRNA could have been processed to type I tRNA via a single 9 nt internal deletion. Thus, the process for generation of the first tRNAs was highly ordered and not chaotic or random, showing that the early Earth was capable during pre-life of ordered, chemically evolved processes. We posit that these ordered processes won out over random processes in chemical evolution because ordered processes were faster to establish core functions. Chaotic processes were simply too slow to generate the genetic adapter that is the core feature of life.

Remarkably, the tRNA body was initially made up of 100% RNA repeats and inverted repeats (stem-loop-stems) of known sequence. The 5’-acceptor stem was a 7 nt GCG repeat (GCGGCGG). The 3’-acceptor stem was a 7 nt complementary CGC repeat (CCGCCGC). The 17 nt D loop minihelix core was a UAGCC repeat (UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA). The 17 nt anticodon and T stem-loop-stems were initially of the sequence ~CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG (_ separates stems and loops; / indicates a U-turn in the RNA backbone; ? indicates that, because of coding, the pre-life sequence is not now known). It is possible the T loop minihelix was formed from the complement of the anticodon loop minihelix, with the initial sequence ~CCGGG_UU/???AG_CCCGG. The 9 nt internal deletion processing events were within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems (CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG→GGCGG (D 3’-stem and tRNA-26) and CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG→CCGCC (type I V loop)). These 9 nt internal deletions were identical on complementary RNA strands, so a single processing mechanism can account for both deletions. The type II V arm for tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser evolved from the initial sequence CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG to form a stem-loop-stem that could be discriminated by LeuRS-IA (5 tRNA

Leu in a synonymous set) and SerRS-IIA (4 tRNA

Ser in a synonymous set) [

11]. Leucine and serine occupy 6-codon sectors in the genetic code. Because there are so many leucine and serine anticodons, the consistent and conserved tRNA type II V arm was used as a determinant for tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser discrimination rather than the anticodon loops. The number of synonymous type II tRNA sets in an organism is limited by the available trajectory set points of the V arm: 2 set points in Archaea (tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser) and 3 in Bacteria (tRNA

Tyr, tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser) [

11]. From analysis of tRNA sequences, the pre-life Earth was capable of accurate complementary RNA replication. Very clearly, the first type II and type I tRNAs were generated by highly ordered, non-random processes on pre-life Earth.

Phylogenomics and bioinformatics methods provide insights into first proteins and cofactors that coevolved with the genetic code [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Integrating these data with tRNA evolution provides unprecedented insight into the pre-life to life transition on planet Earth.

A recent review describes a bricolage theory (multiple diverse functions coalescing into new functions) for evolution of translation systems [

16]. Our view would include a radially outward evolution component centered first on a primitive adapter molecule (ACCA-Gly) and then on RNAs of increasing complexity attaching 3’-ACCA-Gly, evolving by a recognized pathway to Gly-tRNA. We posit that dirty, pre-life polyglycine formed the core aggregator for evolution of translation systems, protocells and the first true cells. Our view posits a powerful chemical selection for the pre-life to life transition on Earth. The history that we relate is centered on tRNA, based on the molecular history of tRNA as inscribed in tRNA sequences. The mechanism for evolution of tRNA demands that RNAs be ligated for complementary RNA replication. Thus, many complex RNAs were generated during pre-life to supply many tasks of complex ribozymes and to generate the first rRNA-like molecules. So, an RNA World and a complex Peptide World radiate from tRNA. There does not appear to be a “chicken and egg” problem in evolution of living cells on Earth. Our radially outward evolution model centered on tRNA makes rich predictions for many experiments.

3. Evolution of Type II and Type I tRNA

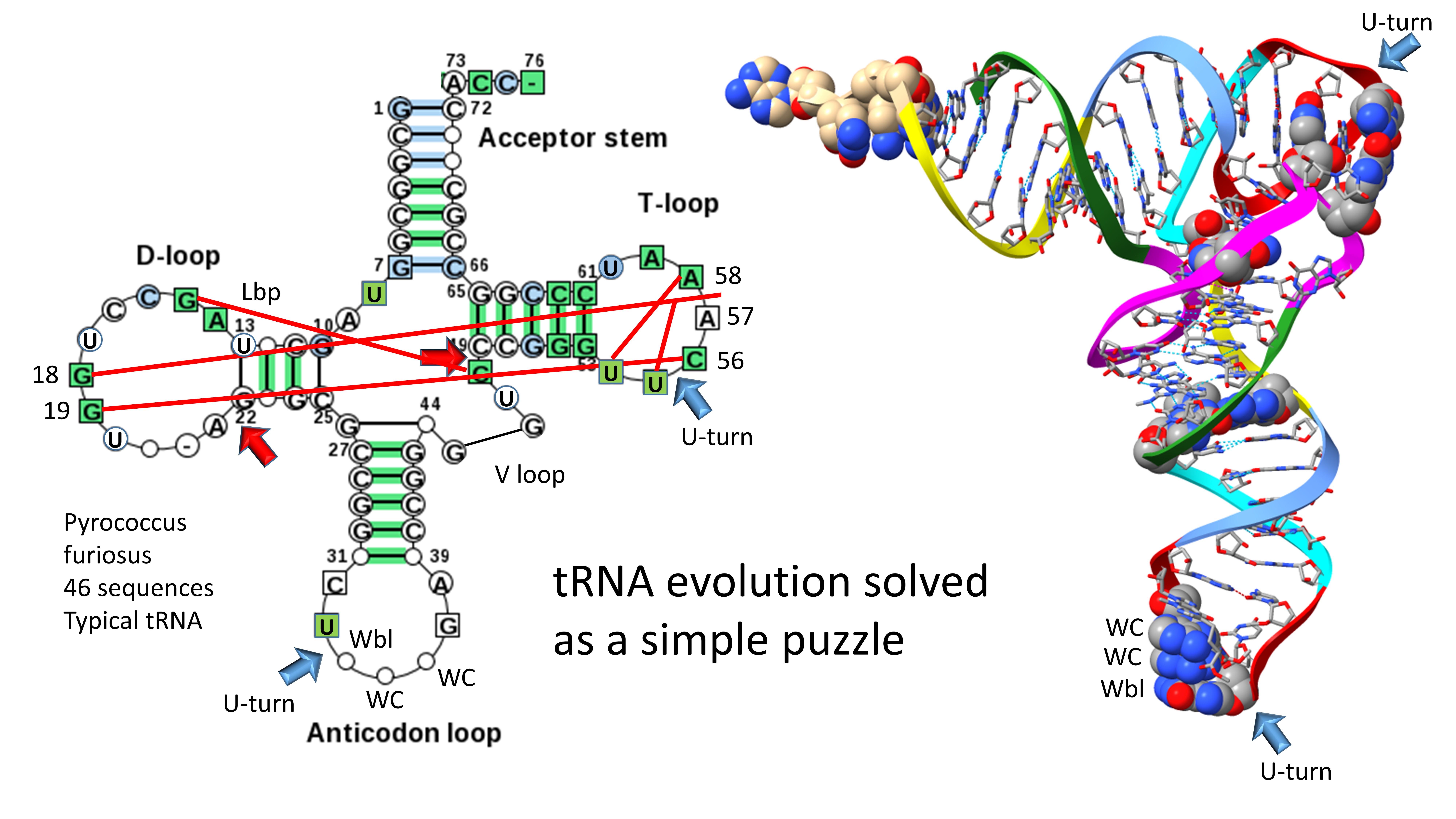

Evolution of type II and type I tRNAs is summarized in

Figure 1. The molecules are colored according to the three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem, as published elsewhere [

6,

10]. A 31 nt D loop minihelix lacking the 3’-ACCA-Gly adapter was ligated to a 31 nt anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelix lacking the 3’-ACCA-Gly adapter, which was ligated to a second anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelix lacking the 3’-ACCA-Gly adapter or else to its very similar complement (to form the T stem-loop-stem). The 93 nt tRNA precursor was then processed by two closely related internal 9 nt deletions within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems. An early version of the type II tRNA could be processed by a single 9 nt internal deletion to a type I tRNA, so type II tRNA could have been a processing intermediate to type I tRNA, depending on the order of deletions to form type I tRNA [

11]. The more 5’ internal 9 nt internal deletion was identical for both type II and type I tRNAs (red arrows). The two internal 9 nt deletions in type I tRNA were identical on complementary RNA strands. On pre-life Earth, the purpose of these molecules was to synthesize polyglycine, posited to have been a main aggregator of pre-life intermediates and protocells [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. The process for tRNA generation shows that the pre-life Earth was capable of: 1) RNA ligation (i.e., by a ribozyme RNA ligase); 2) complementary replication; 3) chiral sorting of precursors; 4) selection of 7 nt U-turn loops; 5) measuring stems and loops; 6) aminoacylation of ribose rings; 7) polypeptide synthesis; 8) internal processing of RNAs; and 9) sorting of U, A, G and C nucleotides and exclusion of other bases.

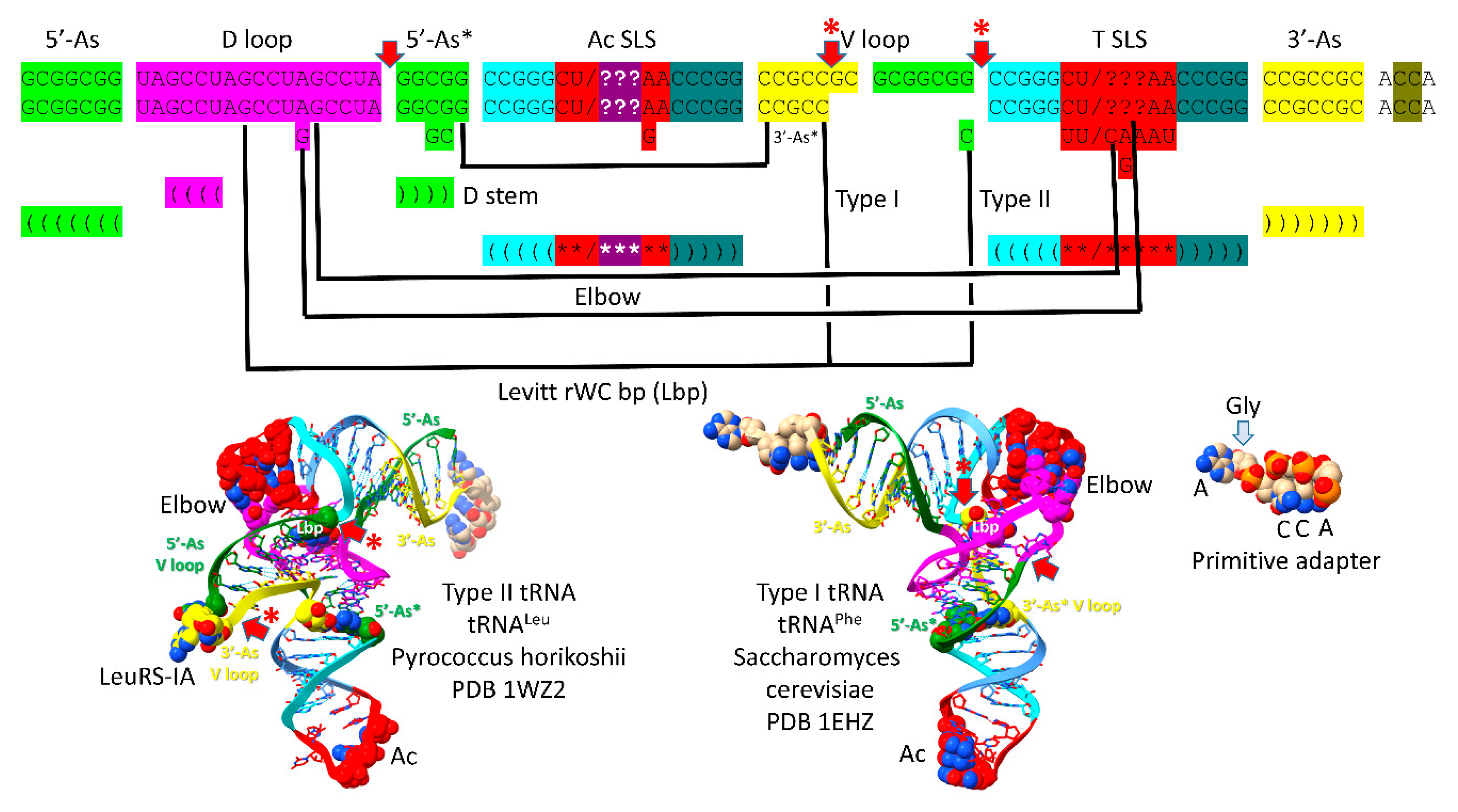

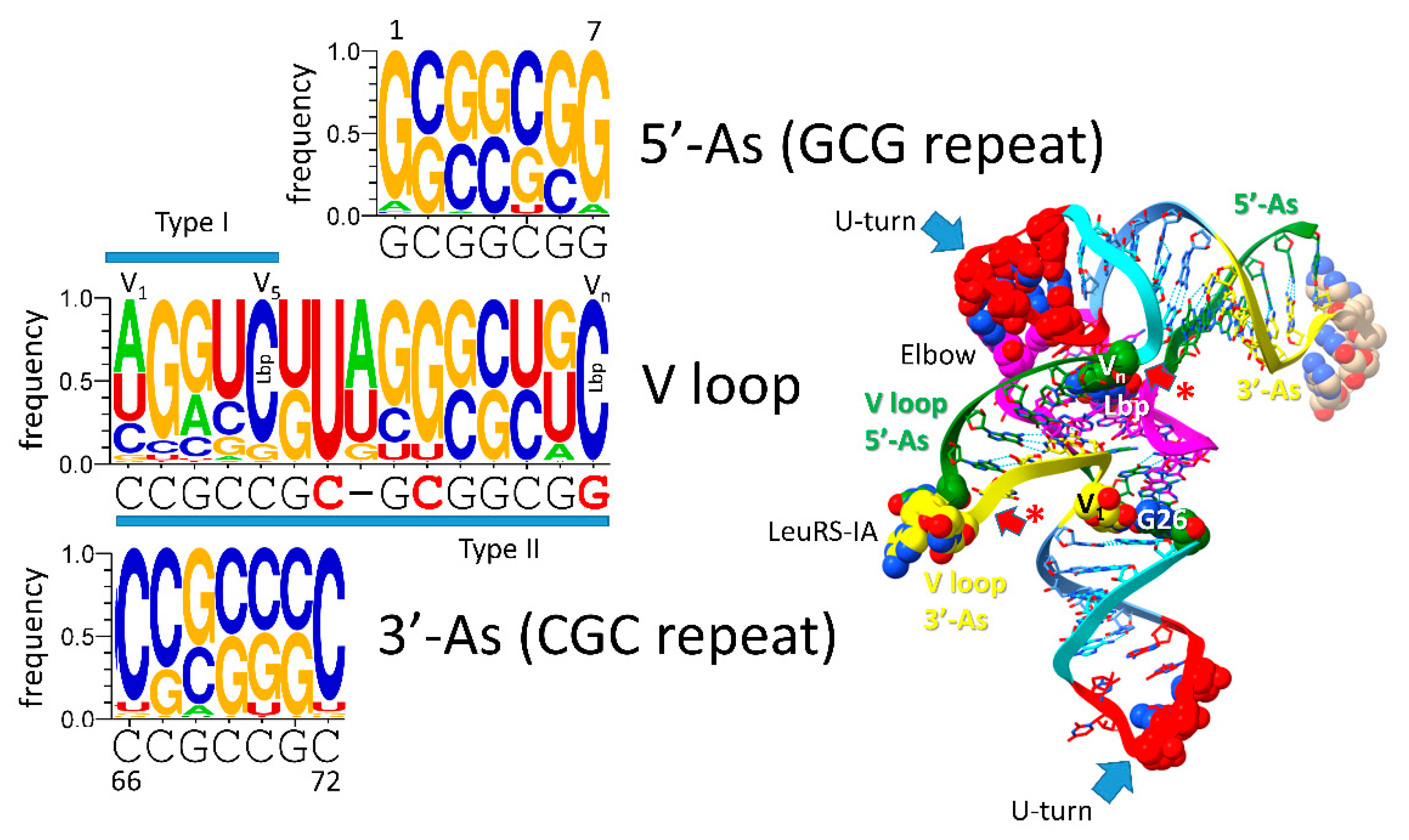

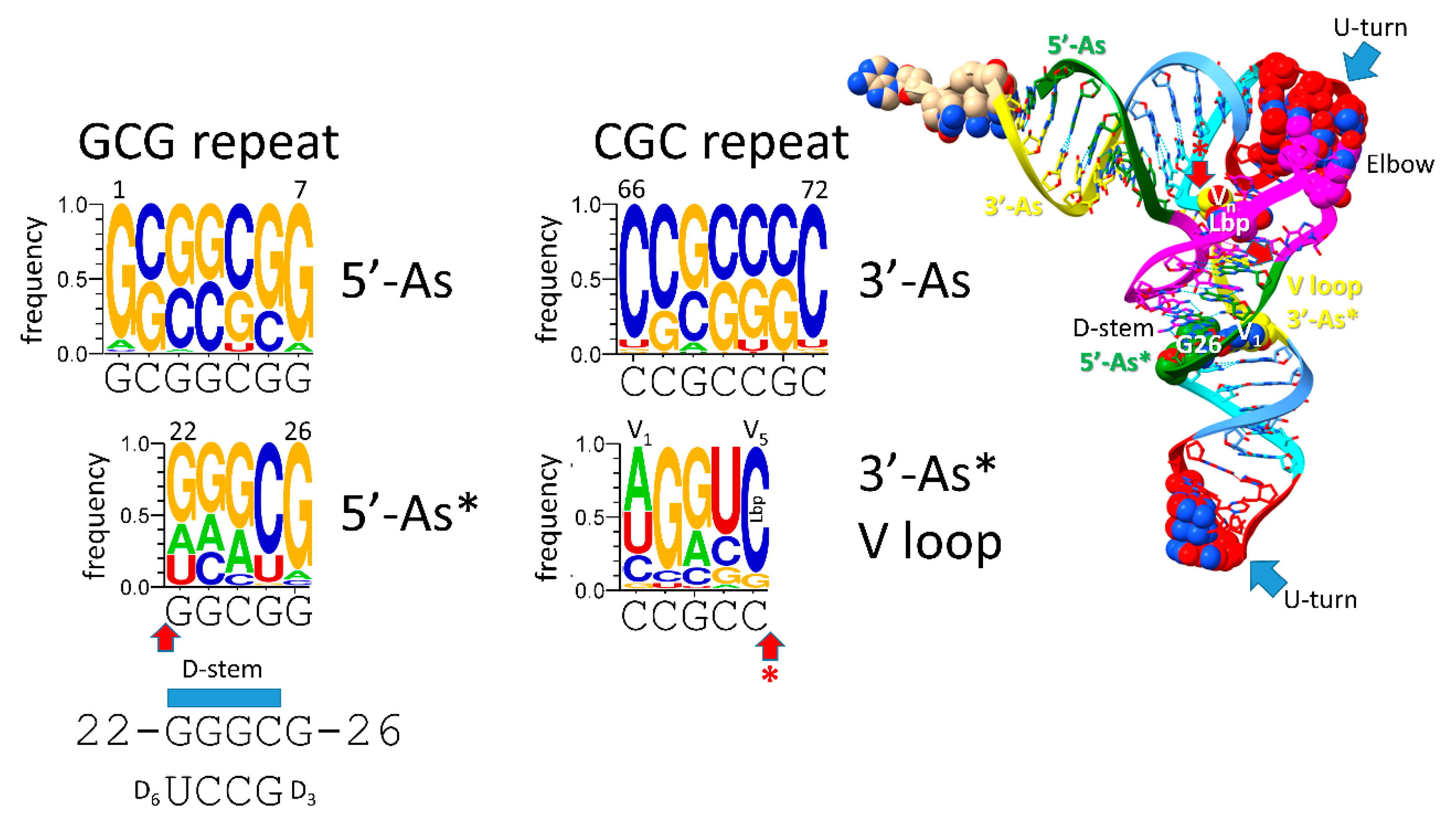

To correlate the tRNA structures to their root sequences,

Figure 2 is shown. The entire tRNA sequence was formed from RNA repeats and inverted repeats (stem-loop-stems). Initially, the orderly process was a surprise because tRNA evolution had been proposed to have been chaotic [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. 5’-acceptor stems and their 5’-acceptor stem remnants were formed from 7 nt GCG repeats (GCGGCGG and after deletion GGCGG). 3’-acceptor stems were formed from complementary 7 nt CGC repeats (CCGCCGC and after deletion CCGCC (the type I tRNA V loop)). The D loop was formed from a 17 nt UAGCC repeat. The anticodon and T stem-loop-stems had the initial 17 nt sequence ~CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG. It is possible that the T stem-loop-stem initially formed from the complement of the anticodon stem-loop-stem (~CCGGG_UU/???AG_CCCGG). Ambiguity in the pre-life sequences arises because some of the nucleotides form the anticodon in tRNA, and the anticodon was scrambled in evolution to support coding. After LUCA (the last universal common (cellular) ancestor) the T loop sequence is known with confidence, but this sequence was strongly selected to form the tRNA “elbow” where the D loop binds the T loop, so uncertainty about the pre-life 7 nt U-turn loop sequence remains at the anticodon positions.

The major difference comparing type II and type I tRNAs is the variable loop (V loop). For type II tRNA, the sequence was a 3’-acceptor stem ligated to a 5’-acceptor stem (initially CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG) [

11,

36]. For type I tRNA, the V loop was initially CCGCC, processed from CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG by an internal 9 nt deletion removing GC_GCGGCGG. The type II tRNA V arm evolved to form a stem-loop-stem with a particular trajectory of the V arm from the tRNA body that is consistent within a synonymous tRNA set (i.e., in an Archaeon, there are 5 tRNA

Leu V arms with a common trajectory unique to tRNA

Leu and 4 tRNA

Ser V arms with a common trajectory unique to tRNA

Ser). Type I V loops contact residues in the D stem, explaining differences in type I V loops from the original sequence. The 5’-acceptor stem (5’-As*) remnant common to both type II and type I tRNAs was formed by an identical internal 9 nt deletion on the complementary RNA strand (CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG→GGCGG by deletion of CCGCCGC_GC). So, a single internal 9 nt deletion process can account for both the more 5’ and 3’ 9 nt internal deletions in type I tRNA. Because of complementary replication in pre-life, the strands on which 9 nt deletions occurred cannot now be known.

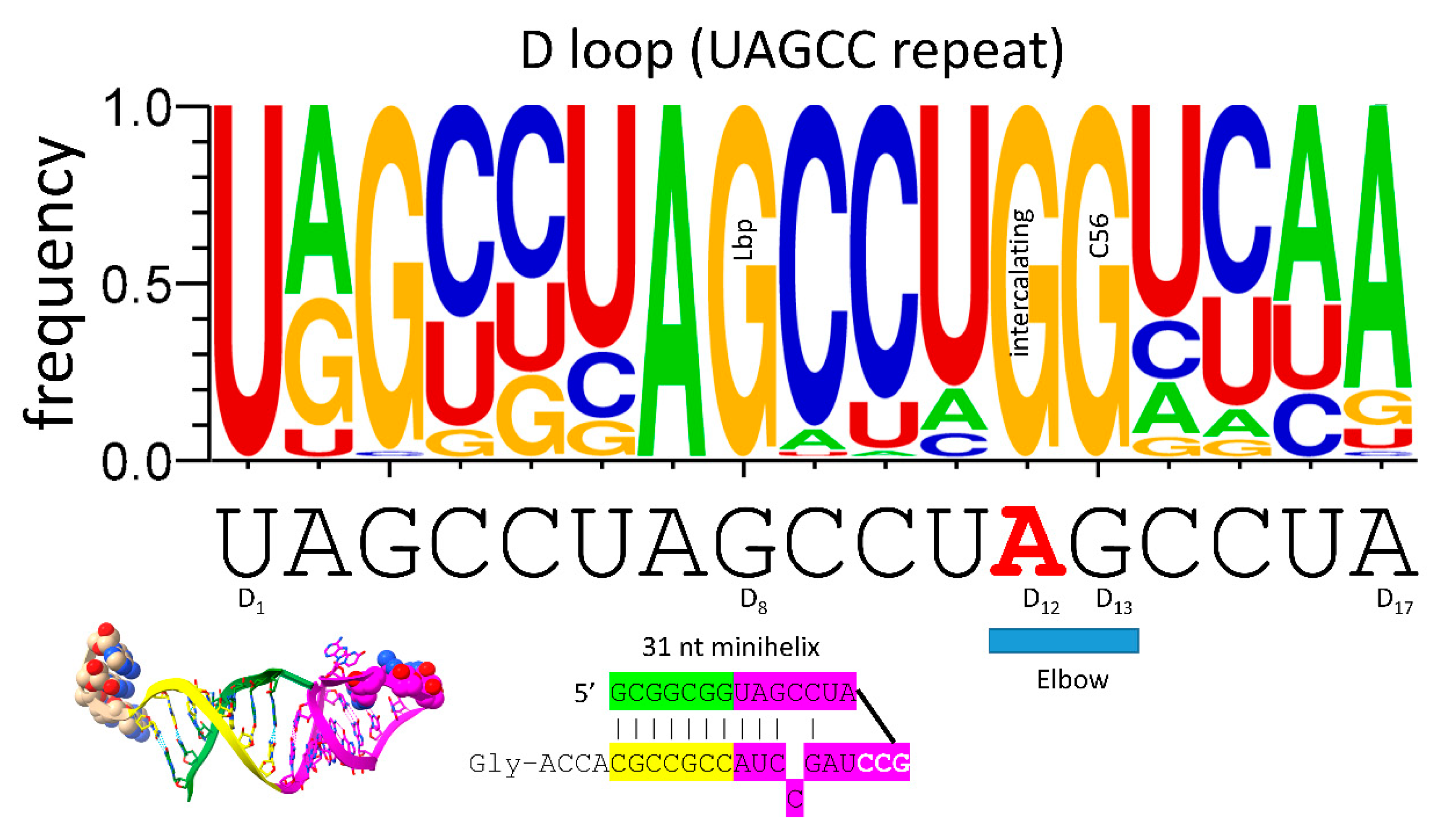

To support the tRNA fold, some sequence deviations were made from the original tRNA sequences and are indicated in

Figure 2. The Levitt reverse Watson-Crick base pair is indicated by tRNA-15G (or GD

8) and the last base of the V loop (CV

5 for type I tRNAs and CV

n for type II tRNAs). For type II tRNA V arms, the original sequence was GV

n, changed to CV

n to support the Levitt G=C base pair. A reverse Watson-Crick base pair is a standard Watson-Crick pair (i.e., in DNA) with one of the bases flipped over and shifted slightly. A G=C reverse Watson-Crick base pair forms two hydrogen bonds instead of three, as in DNA. tRNA-18G (GD

12) replaced an A in the original UAGCC repeat sequence. GD

12 intercalates between tRNA-57A or tRNA-57G and tRNA-58A and forms a hydrogen bond to tRNA-55U, just before the T loop U-turn. The sequence change supports the tRNA fold by stabilizing the tRNA elbow where the D loop and T loop interact. Another elbow contact is tRNA-19G (GD

13) forming a Watson-Crick interaction with tRNA-56C. The 5’-As* sequence was slightly rearranged to support the stability of the D stem (typically 22-GGCGG-26→GGGCG to pair with D

3-GCCU-D

6). tRNA-G26 (or a substituted base) interacts with the V

1 base. The anticodon loop was selected to support coding with various anticodon sequences (typically CU/BNNAA) (B is U, C or G and not A; N is A, G, C or U; / indicates the U-turn). The T loop (typically UU/CAAAU) was selected to support D loop contacts at the elbow.

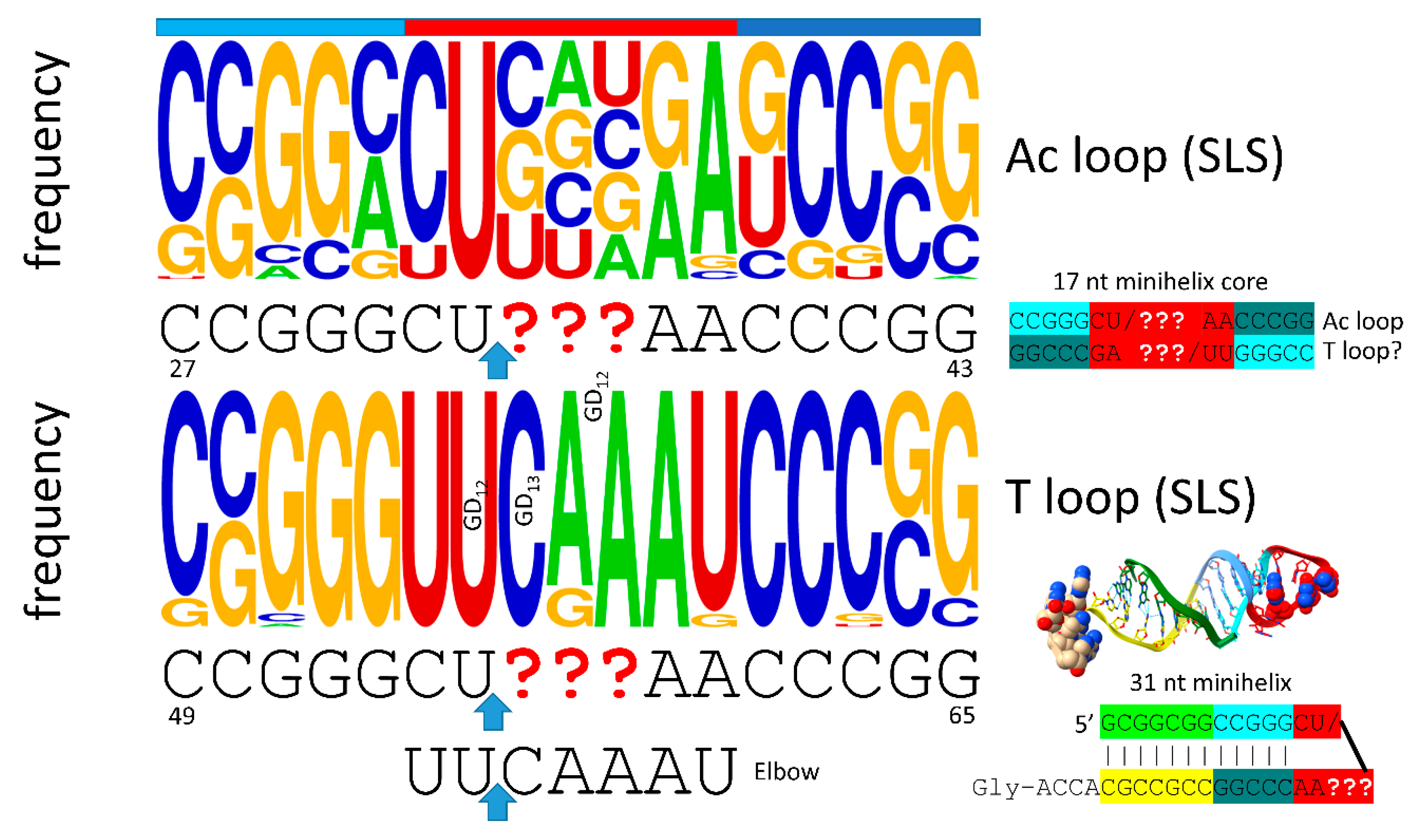

5. The Anticodon and T Stem-Loop-Stems

Remarkably, the anticodon and T stem-loop-stems, as with the D loop UAGCC repeat, are also 17 nt in length (

Figure 4). We conclude that the D loop functioned similarly to the anticodon and T stem-loop-stems on pre-life Earth, with a different sequence but a common purpose, which was synthesis of polyglycine. The anticodon stem-loop-stem was evolved to support coding. In tRNA, the T stem-loop-stem was evolved to support elbow contacts to the D loop. The anticodon stem-loop-stem has the top logo sequence CCGGC_CU/BNNGA_GCCGG. The T stem-loop-stem has the top logo sequence CCGGG_UU/CAAAU_CCCGG. Clearly, these are homologous sequences, just by inspection. Because these are stem-loop-stems, they read very similarly on complementary strands. The T loop, therefore, may be derived from the complement of the anticodon stem-loop-stem, as indicated. We do not know, at this time, how to resolve which strand may have produced the T stem-loop-stem. The ~CU/BNNAA U-turn loop is significant intellectual property for evolution of life, as described below. The anticodon/T stem-loop-stem minihelix is shown in the figure. This is a more rigid stem-loop-stem than the D loop minihelix. On pre-life Earth, there may have been a negative selection for the rigid 31 nt anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelix with 12 C=G pairs. Difficulty in melting and replicating this long stem may have been part of the driving force for evolution of tRNA, in which C=G stems are shorter and more easily melted. It is probable that the flexibility of the D loop minihelix contributed to the initial formation of tRNAs. That is to indicate that tRNA, perhaps, could not have been evolved from ligation of three anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelices, which might have been expected to be, instead, processed to three 31 nt anticodon minihelices.

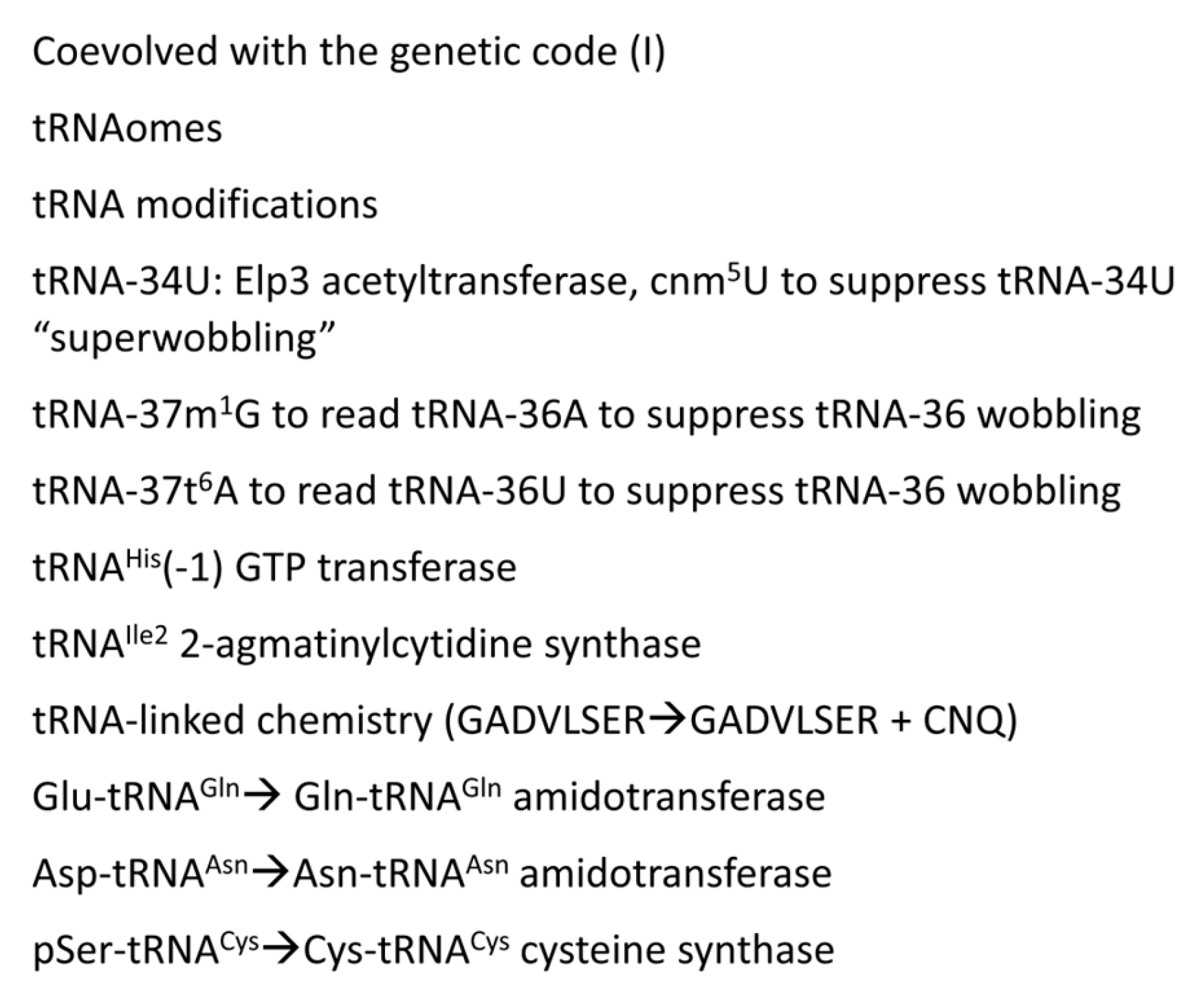

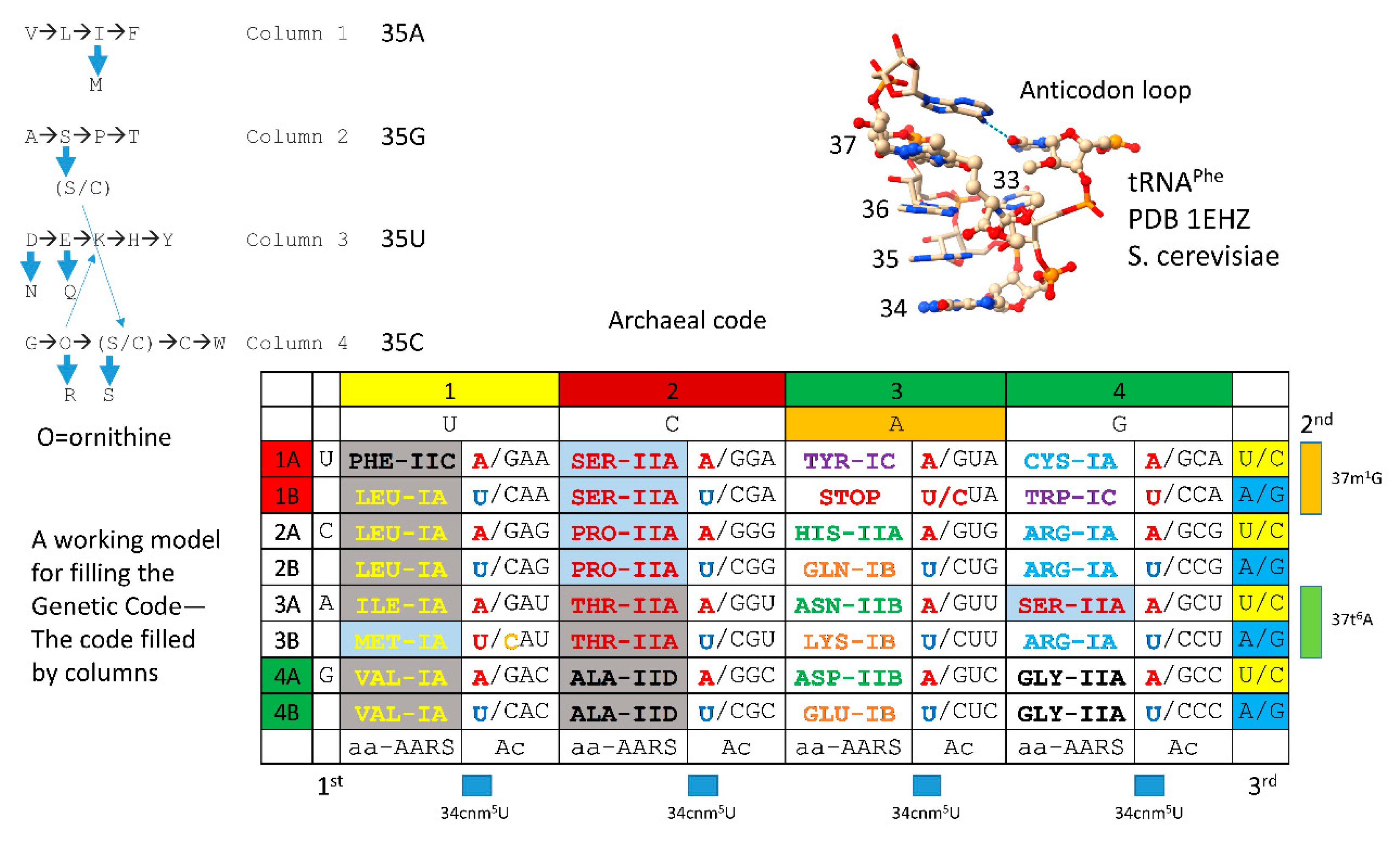

At the base of genetic code evolution, wobble tRNA-34A is not utilized. Wobble tRNA-34G interacts with wobble mRNA-3C (Watson-Crick pairing) or -3U (wobble pairing), so wobble tRNA-34A is not necessary. Without modification, wobble tRNA-34C pairs well with mRNA-3G but poorly with mRNA-3A. So, tRNA-34U is necessary to evolve the code, but unmodified wobble tRNA-34U is not ultimately suitable because of “superwobbling” [

7,

39,

40]. In mitochondria, to shrink the size of the mitochondrial genome and tRNAome, a single unmodified wobble tRNA-34U reads wobble mRNA-3A, -3G, -3C and -3U. To evolve a code including two codon sectors, therefore, requires modification of tRNA-34U to restrict its reading. The acetyltransferase Elp3, which is as ancient as the genetic code, begins the modification [

41]. For instance, tRNA-34cnm

5U (5-cyanomethyluridine) is an example of a tRNA-34U modification initiated by Elp3, which may be as ancient as the genetic code, to suppress superwobbling. The tRNA-34 wobble position, therefore, has only purine-pyrimidine resolution, because reading A and U in a wobble position is awkward.

Reading A and U is also awkward at tRNA-36. Notably, at the base of the code, if tRNA-36A is present, the tRNA-37m

1G modification (or a similar modification) is present. If tRNA-36U is present, the tRNA-37t

6A modification (or a similar modification) is present [

7]. We conclude that modification of tRNA-37 affects the reading of tRNA-36, particularly, if tRNA-36A or tRNA-36U is present. We conclude that tRNA-36 was most likely a wobble position at which wobbling was suppressed during code evolution, in part, by modification of tRNA-37. Note that wobbling at tRNA-34 could not be suppressed in the same manner as tRNA-36 because tRNA-33 is on the opposite side of the anticodon loop U-turn. Modification of tRNA-33U would be unlikely to affect reading of tRNA-34. Modification of tRNA-35 could not be done to suppress tRNA-34 wobbling. As a Watson-Crick position for coding, there are four bases present at tRNA-35 and their modifications might disrupt coding.

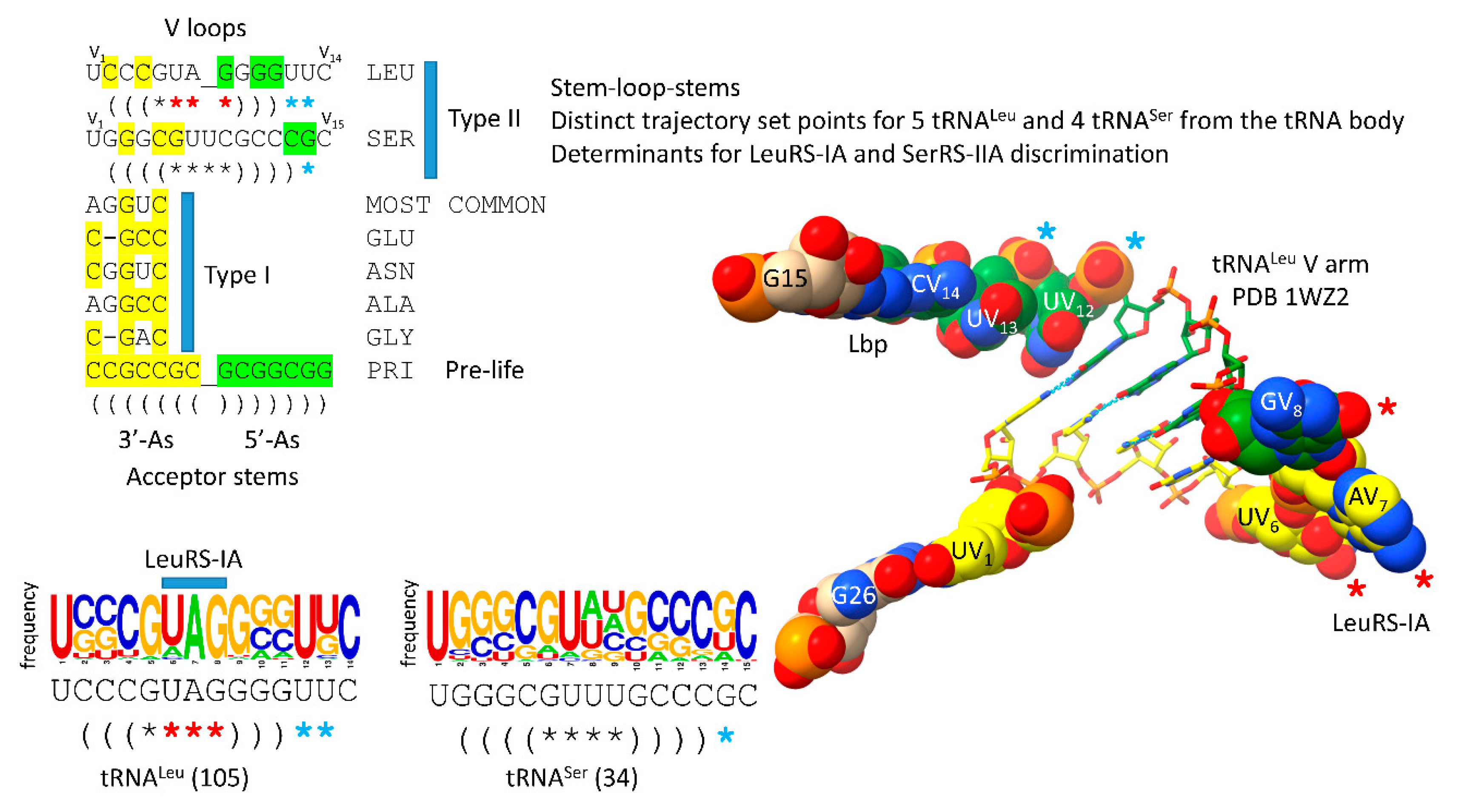

9. Evolution of the Type II V Arms and V Arm Trajectories

The number of synonymous tRNA sets in an organism that can have type II V arms is limited by the number of permitted V arm trajectories (

Figure 8) [

11]. In Archaea, only the synonymous sets of tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser utilize type II V arms. There are 5 tRNA

Leu and 4 tRNA

Ser in an ancient Archaeon, and each synonymous set of tRNA

Leu or tRNA

Ser has a common V arm trajectory and a similar sequence within the set. The V arm trajectory is given by the number of unpaired bases between the 3’-V arm stem and the Levitt base CV

n. For tRNA

Leu, the V arm has a trajectory score of 2 unpaired bases. For tRNA

Ser, the V arm has a trajectory score of 1 unpaired base. LeuRS-IA binds the tRNA

Leu V arm end loop V

6-UAG-V

8. The V

6-UAG-V

8 sequence that binds LeuRS-IA is highly conserved in Archaea (see the sequence logo). SerRS-IIA binds to the V arm stems and the elbow of tRNA

Ser. SerRS-IIA mostly recognizes the distinct trajectory of tRNA

Ser V arms and rejects tRNA

Leu V arms that have a cramped trajectory for SerRS-IIA contacts. In Archaea, only two type II V arm trajectories are observed. In Bacteria, by contrast, three type II V arm trajectories evolved. In Bacteria, tRNA

Tyr is also a type II tRNA. In Bacteria, for tRNA

Tyr the V arm has a trajectory set point score of 2 unpaired bases; tRNA

Leu has a trajectory set point score of 1 unpaired base; tRNA

Ser has a trajectory set point score of 0 unpaired bases [

11]. tRNA

Ser V arms in Bacteria are longer than in Archaea, which may explain in part the evolution of the third trajectory set point of 0 unpaired bases for bacterial tRNA

Ser. The trajectory set point of 0 is not utilized in Archaea. In Bacteria, the longer tRNA

Ser V arm stems may stabilize the tighter connection at the base of the V arm stem (V

2-V

(n-1)).

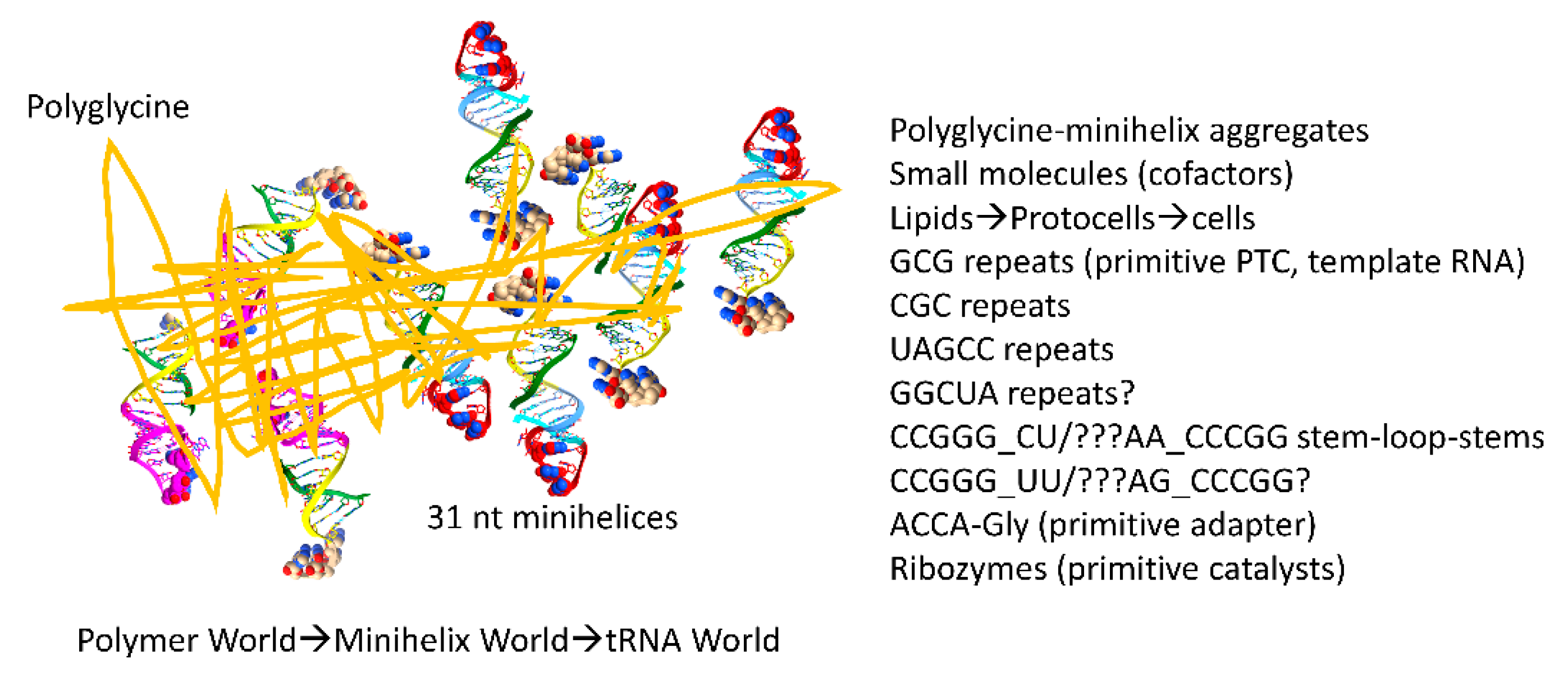

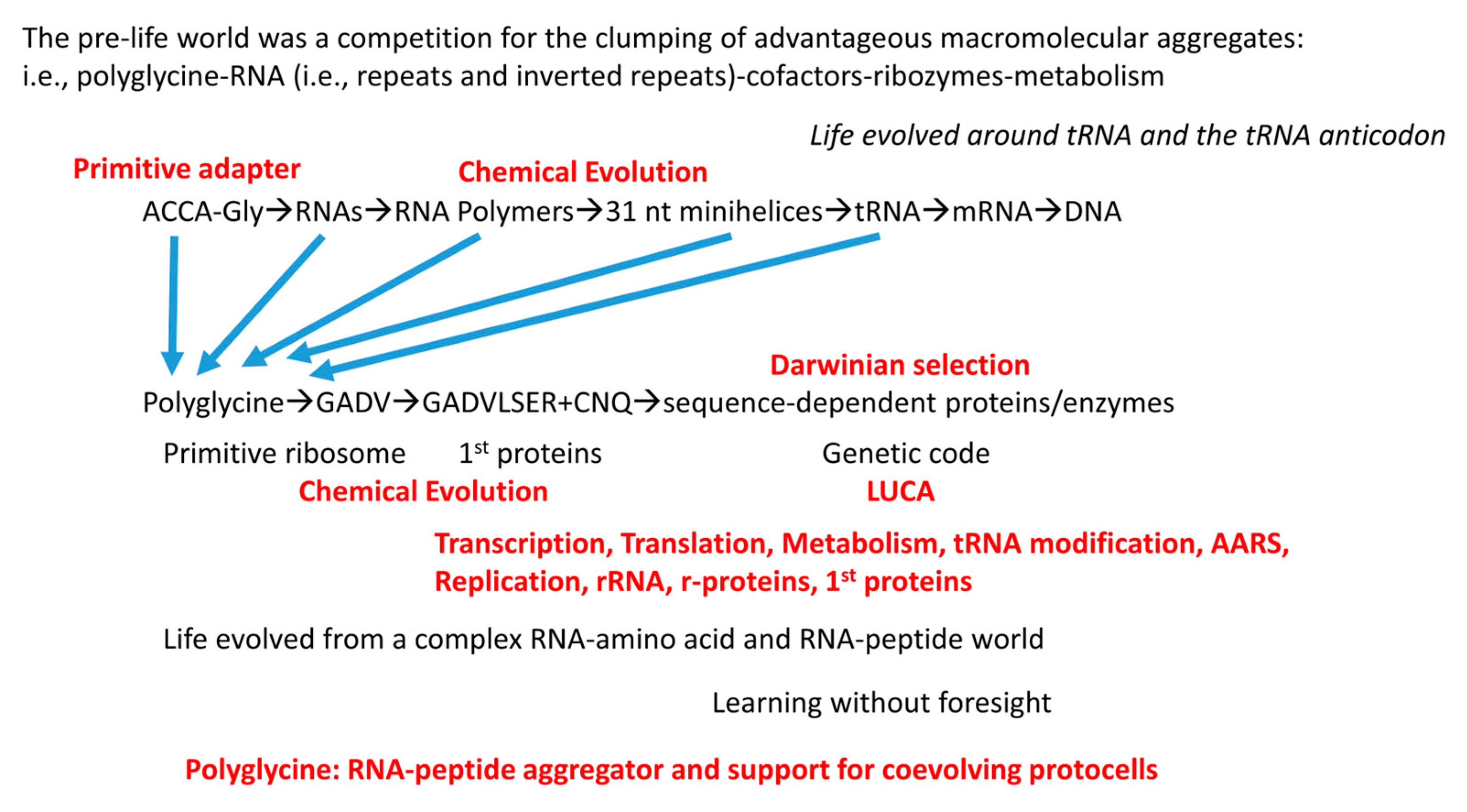

12. A Model for Evolution of the First Cells

A model to describe chemical evolution of the first cells is shown in

Figure 11. There is no “chicken and egg” problem in the pre-life to life transition, and no supreme deity appears to be required. Phylogenomic and bioinformatics provide huge insight into the enzymes and cofactors that were likely present at LUCA. Here, we attempt to correlate parts of that emerging analysis with inferences that are based on tRNA evolution, as recorded in conserved tRNA sequence.

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 provide lists of some of the tRNA modifications and protein enzymes identified for LUCA that we infer must have coevolved with the genetic code.

Life on Earth evolved around tRNA and the tRNA anticodon. So far as we can see, this conclusion cannot now rationally be questioned. Translation systems and the genetic code coevolved with tRNAomes. Without a genetic adapter as good or better than tRNA, it is difficult to consider how else complex encoded enzymes and proteins could have evolved. Considering structure, function and evolution, it is difficult to re-design tRNA to evolve a more advantageous genetic adapter. To replace tRNA with a genetic adapter that is not comprised of RNA and that is not evolved within an aqueous environment is a daunting problem. To alter the tRNA anticodon loop to another loop structure (i.e., 3, 4, 5, 6 or 8 nt) is also a daunting problem to which there may not be a reasonable solution. The 7 nt U-turn tRNA anticodon loop must evolve to a 3 nt genetic code with a single tRNA-34 wobble position. The chances of evolving a 4 nt genetic code are vanishingly slim. Ribosomes evolved around tRNA. For instance, the large ribosomal subunit includes a tRNA-shaped channel through which the tRNAs advance [

48]. We conclude that the genetic code and sequence-dependent proteins evolved around tRNA and the tRNA anticodon. Also, mRNA evolved secondarily to tRNA, so evolution of the tRNA anticodon directed mRNA codon evolution. Therefore, evolution of tRNA is the central story in evolution of life on Earth. Fortunately, the history of tRNA evolution was recorded and conserved for ~4.2 billion years in tRNA sequence.

We posit two coupled mechanisms for aggregation of pre-life macromolecules leading to life: 1) aggregation of macromolecules interacting with (dirty) polyglycine; and 2) progression of lipids→protocells→cells probably emulsified by polyglycine. When we refer to polyglycine, we consider dirty polyglycine, with other induced chemistries (i.e., reaction products from ultraviolet light exposure) and associations (i.e., binding by other amino acids and chemicals). Glycine was probably the first encoded amino acid. Glycine is the simplest amino acid. Glycine occupies the most favored sector in the genetic code (tRNA

Gly (BCC)), indicating that glycine might be the first encoded amino acid [

8,

9,

25,

26,

27]. Glycine was present on early Earth.

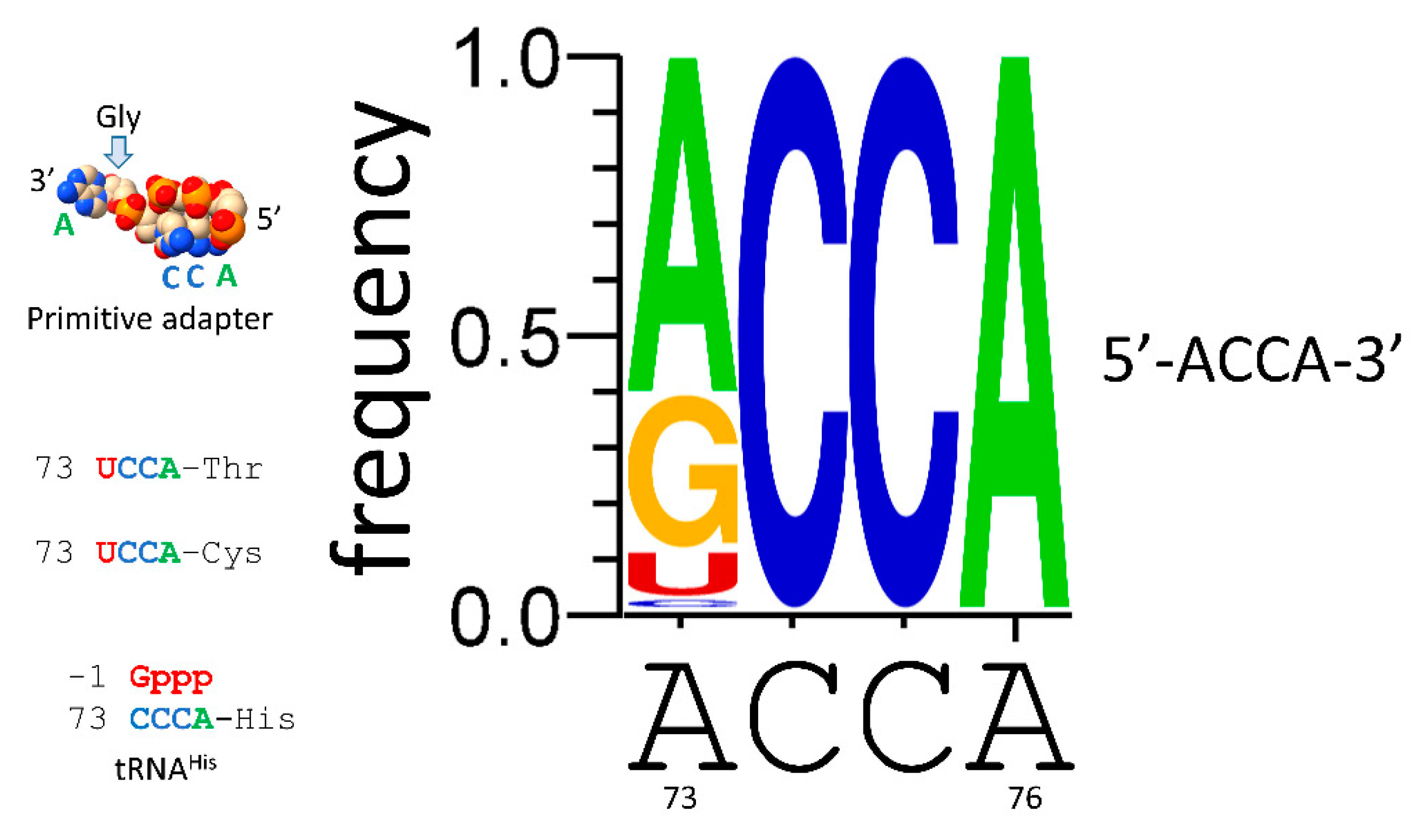

We posit ACCA-Gly as a primitive adapter molecule (

Figure 9). We posit that ACCA-Gly was ligated (i.e., by a ribozyme ligase) to many RNAs on pre-life Earth. Analysis of tRNA sequence reveals that GCG, CGC and UAGCC repeats were present in pre-life Earth. Also, ~CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG stem-loop-stems were present. Multiple ACCA-Gly could assemble on GCGGCGGCG repeats. Binding of multiple ACCA-Gly in proximity should be sufficient to support polyglycine synthesis (i.e., with wet-dry cycles) [

46].

In the progression of RNAs of increasing complexity, GCG repeats, CGC repeats, UAGCC repeats and stem-loop-stems were recombined into 31 nt minihelices. With ACCA-Gly attached, these 35 nt minihelices could have been used to synthesize polyglycine, using a coevolved and mobile peptidyl transferase center that may have first arose from GCG repeats. At some point a primitive decoding center and the first mRNA-like molecules coevolved. We posit that polyglycine synthesis was the primary selective chemical driving force. As a molecular aggregator, polyglycine provided the major chemical selection for pre-life chemistries leading to the first cells. As noted above, 31 nt minihelices may have been partly selected against because of their long and very stable stems. This negative selection may have provided some of the impetus to evolve the first tRNAs, which do not include the long stems that may have rendered minihelices difficult to unwind and replicate. Also, tRNA was positively selected because it is a molecule that could “teach” itself to code by duplication and repurposing in a pre-life environment.

We posit that the initial purpose of type I and type II tRNAs was to synthesize polyglycine on a primitive decoding center with a primitive mRNA, utilizing a mobile, primitive peptidyl tranferase center perhaps derived initially from GCG repeats. As reported elsewhere, the genetic code appears to have evolved from encoding G→GADV→GADVLSER+CNQ→20 aas + stops [

6,

8,

9,

11,

27]. Coevolution of tRNAomes, AARS, ribosomes, mRNA, tRNA-linked chemistry, first proteins and protocells drove the evolution of the first cells. We define first proteins as those that coevolved with the genetic code. We consider proteins identified at LUCA by phylogenomic studies to be likely candidates for first proteins.

We posit that the tRNA-based genetic code initially evolved to synthesize polyglycine. GADV are the four simplest amino acids and are posited to be the first four encoded [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. GADV occupy the most favored row in evolution of the genetic code (tRNA-36C; anticodon BNC). The genetic code then appears to have progressed to an 8 amino acid bottleneck (GADVLSER). The 8 amino acid bottleneck arose because both tRNA-34 and tRNA-36 were wobble positions and only a single wobble position could be read at a time [

6,

8,

11,

27]. At a wobble position, only pyrimidine-purine resolution could be achieved, so, at this stage, the maximum complexity of the code was 2x4 or 4x2, which equals 8. Leucine and serine evolved to occupy 6-codon sectors in the final code, and tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser are type II tRNAs with longer V arms for LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA recognition, to avoid anticodon ambiguity in coding. Arginine also occupies a 6-codon sector of the code, but tRNA

Arg is a type I tRNA. To circumvent coding ambiguity, ArgRS-IA unwinds the tRNA

Arg anticodon loop to expose additional bases for cognate tRNA

Arg charging [

55]. CNQ then may have been added to the expanding code via tRNA-linked chemistry. Serine→cysteine [

56,

57], aspartic acid→asparagine and glutamic acid→glutamine [

58,

59] are reactions identified in ancient organisms today. We posit that these reactions expanded the 8 amino acid bottleneck to an 11 amino acid code that could support synthesis of first proteins to coevolve with the code. Many proteins essential for life coevolved with the genetic code. Upon suppression of wobbling at tRNA-36, the genetic code expanded to 20 amino acids plus stops. Because of wobbling at tRNA-34, the maximum complexity of the genetic code is 2x4x4=32 assignments. Wobbling at tRNA-34 could not be suppressed in evolution. The code froze at 20 amino acids plus stops because of fidelity mechanisms. In textbooks and school, the genetic code is described as having a complexity of 4x4x4=64 assignments. That is not correct because ambiguous reading of wobble tRNA-34 on the ribosome requires degeneracy.

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 describe some of the enzymes that coevolved with the genetic code to indicate how biological complexity arose [

12,

13,

14,

15,

60].

Figure 12 concentrates on tRNAomes, tRNA modifications and tRNA-linked chemistry supporting code evolution. We posit that LUCA had a fully established genetic code [

12,

13]. tRNAomes coevolved with mRNA, ribosomes, AARS enzymes and other first proteins. tRNA modifications were necessary to evolve the code. Specifically, tRNA-34U modifications (i.e., tRNA-34cnm

5U) were necessary to suppress superwobbling [

7]. Such modifications begin with the Elp3 acetyltransferase. The 5-carbon of tRNA-34U is acetylated by Elp3 followed by other modifications. tRNA-34cnm

5U appears to be one of the oldest such modifications. Without suppression of superwobbling, the genetic code would lack 2-codon boxes. To read tRNA-36A required a tRNA-37m

1G modification or a variation. To read tRNA-36U required a tRNA-37t

6A modification or a variation. We posit that tRNA-36 was initially a wobble position. Wobbling at tRNA-36 was partially suppressed by tRNA-37 modifications. tRNA

His(-1) GTP transferase was necessary to properly position tRNA

His in the peptidyl site of the peptidyl transferase center. tRNA

His(-1) GTP transferase also confers a unique discriminator sequence for accurate histidine charging by HisRS-IIA [

41,

61]. For methionine to enter the genetic code, tRNA

Ile2 2-agmatinylcytidine synthase and loss of tRNA

Ile (UAU) were required. We posit that evolution of the genetic code stalled at 8 amino acids because of wobbling at tRNA-36. The 8 amino acid bottleneck was partially relieved by: 1) modifications at tRNA-37 [

7]; 2) tRNA-linked chemistry to synthesize C, N and Q from S, D and E; and 3) evolution of the decoding center “latch” (see below). S→pSer→C reactions have been characterized [

57]. D→N and E→Q amidotransferases have been identified [

58,

59,

62].

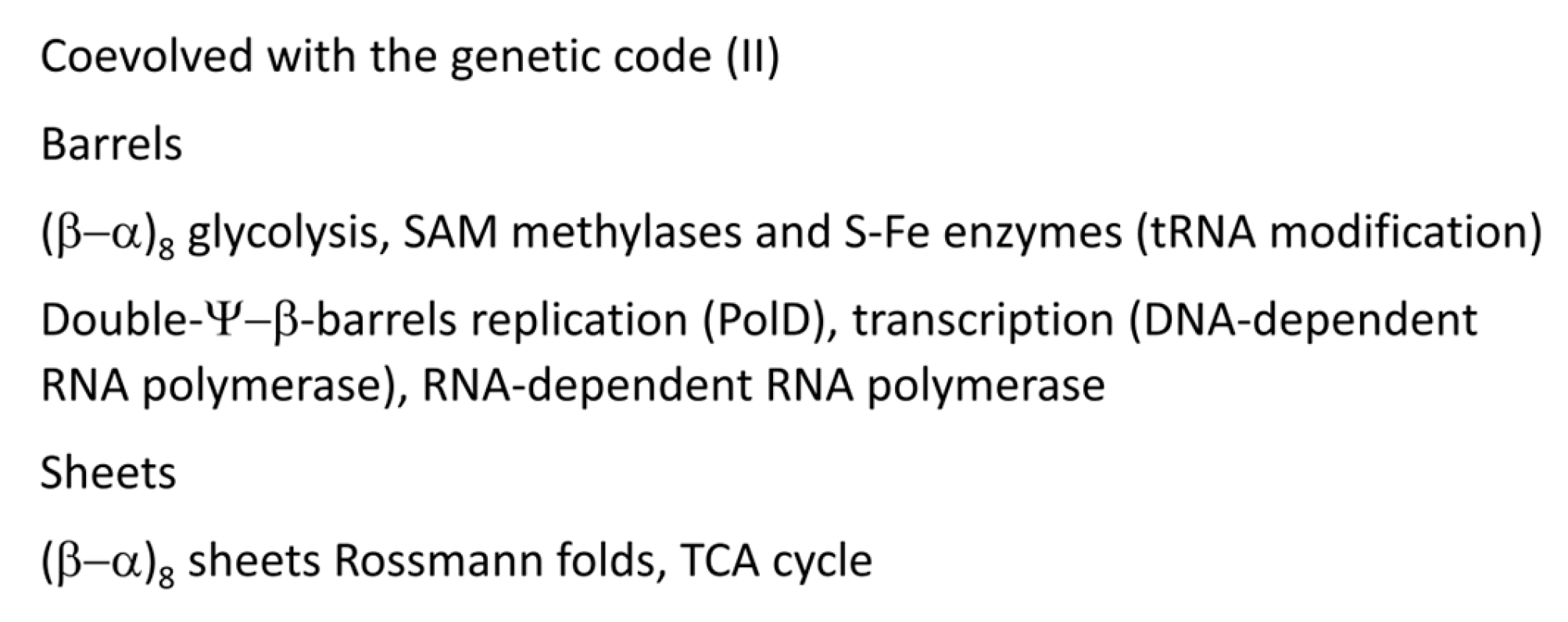

Figure 13 indicates barrels and sheets that support metabolism, DNA replication, transcription and essential tRNA modifications. We have proposed that (β−α)

8 barrels (i.e., TIM barrels; TIM for triosephosphate isomerase) were formed by a similar mechanism to tRNA in which multiple similar or identical RNAs were ligated for replication [

6]. Ligation of multiple βαβα units resulted in (β−α)

8 barrels, which were also refolded into (β−α)

8 sheets (losing β7 in the process). TIM barrels and Rossmann folds describe much of core metabolism. Double-Ψ−β-barrels were formed similarly to (β−α)

8 barrels by RNA ligation, in this case, of two RNAs encoding ββαβ units followed by folding into the barrel ββαβββαβ. Two double-Ψ−β-barrel type enzymes describe DNA polymerase PolD in Archaea, which may be the first replicative DNA-dependent DNA polymerase [

63,

64], and, also, DNA-dependent RNA polymerases in all organisms [

1,

63].

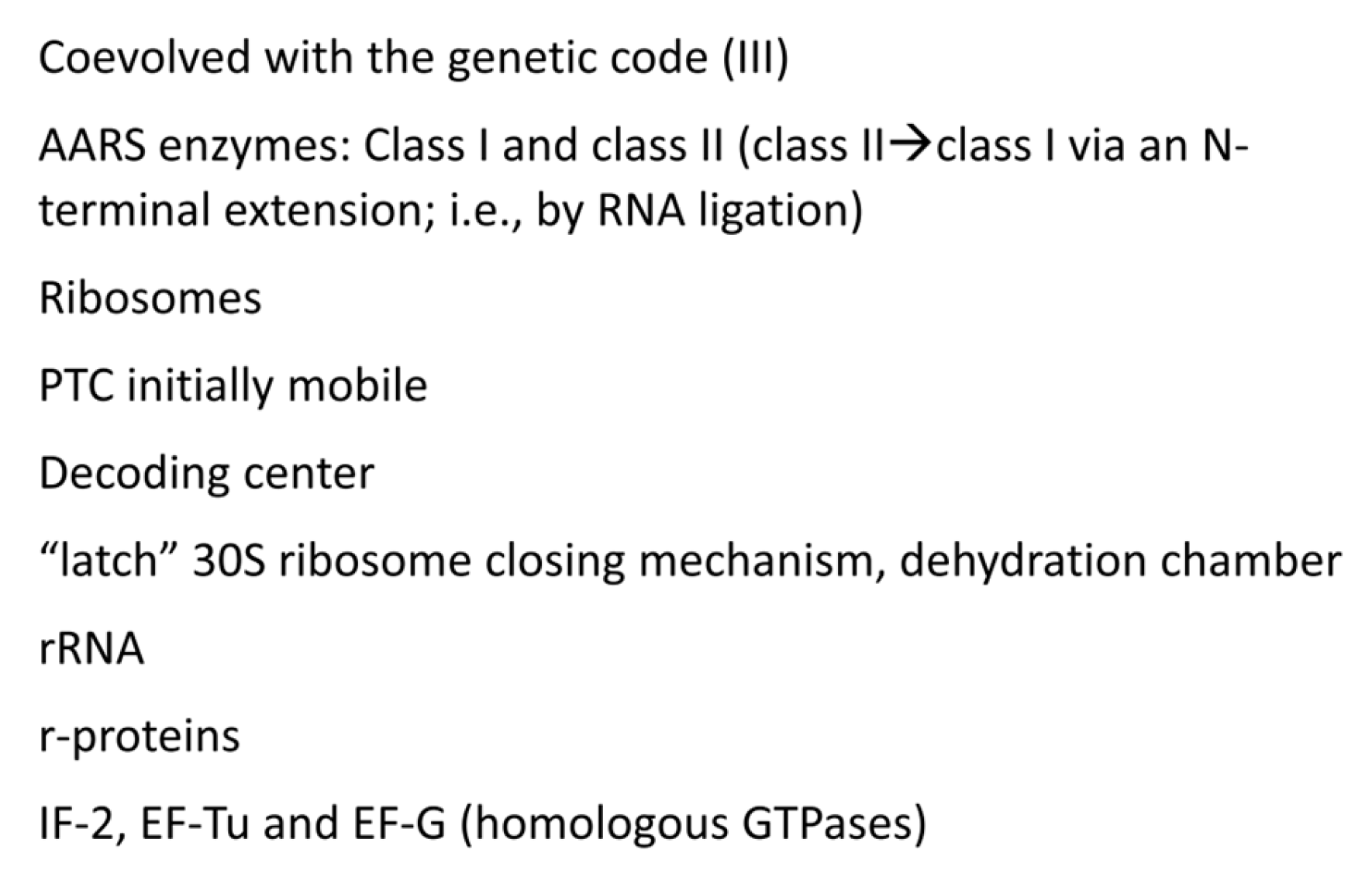

A summary of additional first protein translation functions is shown in

Figure 14. Ribosomes are posited to have evolved from an independent decoding center and peptidyl transferase center. Translation initiates on the small ribosomal subunit, which includes the decoding center and most of the “latch”. The latch enforces Watson-Crick geometry at the two Watson-Crick positions (anticodon tRNA-35 and -36; mRNA codon 1 and 2) and regulates wobbling (anticodon wobble tRNA-34; mRNA wobble codon 3) [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. The ribosomal large subunit that includes the peptidyl transferase center (aminoacyl site and peptidyl site) couples with the small subunit after initiation, and, in tandem, the small and large ribosomal subunits support accurate stepwise translocation. Initiation factor 2 (IF-2), EF-Tu and EF-G are homologous GTPases that support initiation, aa-tRNA entry and translocation. EF-Tu and EF-G alternate binding to shared, overlapping sites mostly on the large ribosomal subunit during elongation. We consider the translation system to be relatively simple in concept but complex in its genetics and evolved structure. Basically, the ribosome appears to be a simple construct with a complex genetic history and many add-ons to the original evolving functional core.

Recent work on ancient protein folds SH3 and OB that are common in ribosomal proteins and cradle-loop barrels (i.e., double-Ψ−β-barrels;

Figure 13) is very consistent with mechanisms we describe for evolution of first proteins [

70,

71].

LUCA appears to have encoded a full set of AARS enzymes and, therefore, must have had an intact genetic code. Despite claims to the contrary [

72,

73,

74,

75], class II and class I AARS enzymes are homologs [

8,

9,

27,

28]. Apparently, the first class I AARS (probably a primitive ValRS-IA) was formed by addition of an N-terminal extension to a primitive GlyRS-IIA. From the tRNA evolution scheme, probably, the 5’-RNA N-terminal encoding extension was ligated to a GlyRS-IIA RNA for replication, much as described above for 31 nt minihelix replication and tRNA evolution (

Figure 1). Because translation termination was initially imprecise, these RNAs need not necessarily have been ligated in phase.

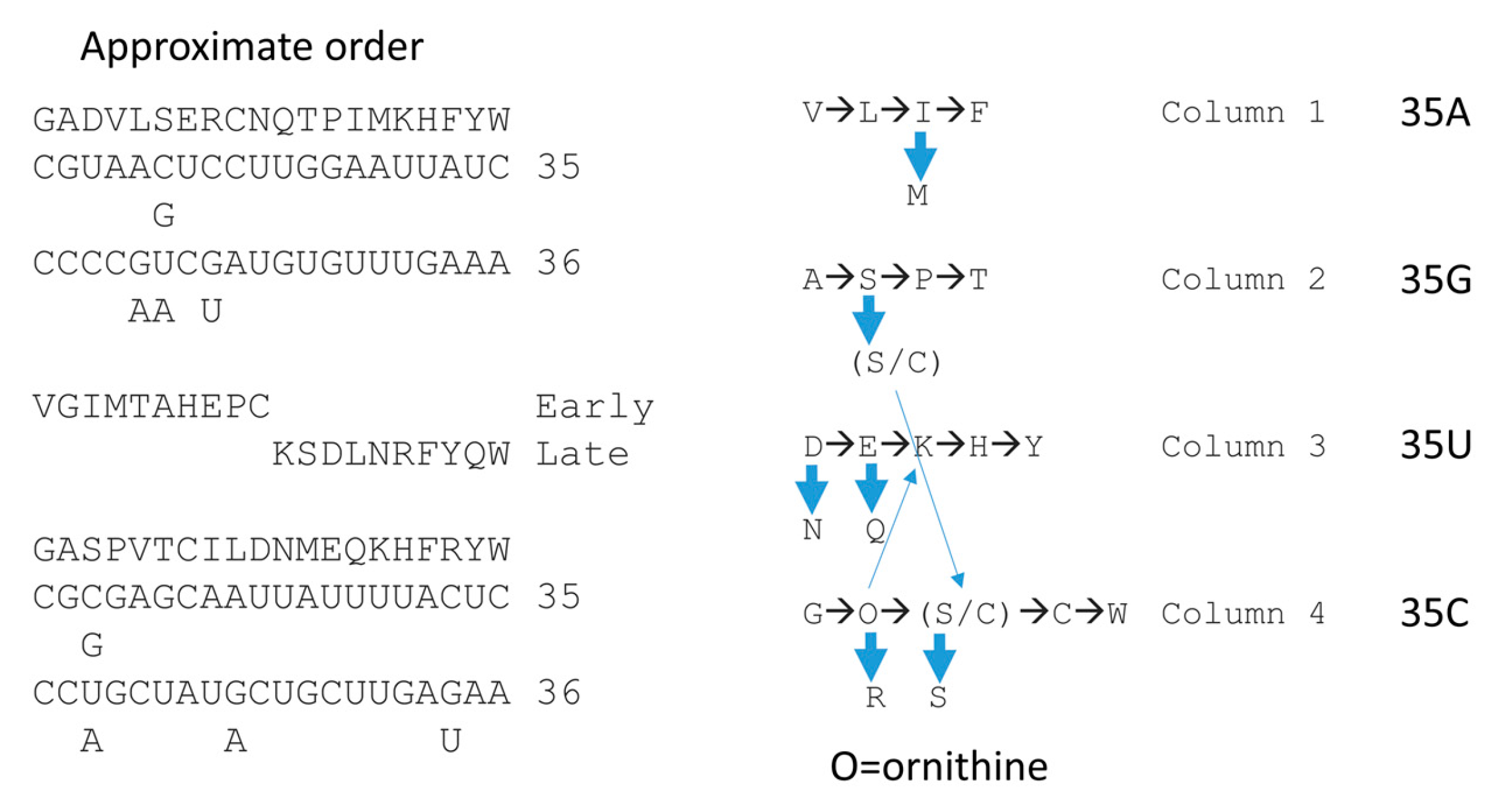

13. Order of Addition of Amino Acids into the Genetic Code

The precise order of addition of amino acids into the genetic code is important but has been difficult to determine. Recently, phylogenomic studies have been used to attempt to make this determination [

13]. In contrast, we have approximated an order of addition into the code from inference based on the highly structured code [

8,

9,

11,

27]. We find the phylogenomic arguments somewhat awkward to provide a clear answer to this fundamental question about the origin of life. Also, we experienced some difficulty in sorting different amino acid addition orders that arise from different methods of ascertainment. What we conclude is that the best current understanding of this issue results if the order of amino acid additions is split into different columns of the genetic code, which causes different determinations to make better sense and to approach closer agreement.

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 describe our best current understanding of this issue presented as a potential working model for amino acid entry into the genetic code.

Figure 15 shows how consideration of evolution within code columns can simplify the discussion. Very clearly, the genetic code evolved to a large extent within code columns [

8,

9,

11,

27,

28]. Glycine is the simplest amino acid and occupies the most favorable anticodon (tRNA-35C, tRNA-36C) [

8,

9,

11,

27,

28]. The simplest amino acids GADV are found on the 4th row of the code (tRNA-36C), indicating that these were the first amino acids to be encoded [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. It appears that amino acids entered the code filling larger sections that were then reduced as other amino acids entered. The amino acids that entered first retained the most favored available anticodons, according to the rules tRNA-35 (C>G>U>A) and tRNA-36 (C>G>U>>A).

In

Figure 16, the working model for amino acid additions is correlated with the structure of the archaeal genetic code, which we posit was the code at LUCA [

8,

9,

11,

27,

28]. Bacterial and eukaryotic codes appear to be derived from a more primitive archaeal code at LUCA and via fusions at LECA (last universal eukaryotic common ancestor). In column 1, VIML are similar hydrophobic amino acids, and ValRS-IA, IleRS-IA, MetRS-IA and LeuRS-IA are closely related AARS enzymes. Methionine is posited to have invaded a 4-codon isoleucine sector, leading to differential wobble C modifications (C→agmatidine to encode isoleucine [

76,

77]; C is lightly modified (elongation) or unmodified (initiation) to encode methionine). Also, anticodon UAU is not utilized at the base of the code because use of UAU would cause ambiguity in coding for isoleucine and methionine. Leucine eventually occupies a 6-codon sector. We posit that an enlarged leucine sector gave rise to invasion by isoleucine and then methionine.

In column 2, ATPS are neutral amino acids. T and S are chemically related. Serine eventually occupies a 6-codon sector of the code that is split between column 2 and column 4 of the code. Serine is the only amino acid that splits between two code columns. ThrRS-IIA, ProRS-IIA and SerRS-IIA are closely related AARS enzymes. We posit that a now extinct AlaRS-IIA may have been replaced before LUCA with AlaRS-IID to suppress tRNA charging errors. We posit that an enlarged serine sector gave rise to threonine and proline sections and also may have allowed early entry of cysteine into the code. Cysteine, for instance, was necessary for early folding of AARS enzymes by binding Zn [

28]. We posit that serine jumped from column 2 to column 4 of the genetic code, and this event may be associated with early entry of cysteine into the code. Cysteine can be generated from serine by two mechanisms [

56,

57]. Cysteine ended up on column 4, row 1 of the code.

We have previously suggested that D and E entered the code to form a striped pattern in column 3 that resolved to D, N and H in rows 4A, 3A and 2A and E, K and Q in rows 4B, 3B and 2B. In tRNA-linked reactions, D→N and E→Q via amidotransferase enzymes [

58,

59,

62]. Note that, in Archaea, AspRS-IIB, AsnRS-IIB and HisRS-IIA are closely related AARS enzymes. In Archaea, GluRS-IB, LysRS-IB and GlnRS-IB are closely related AARS enzymes. Interestingly, GlnRS-IB was not utilized at the base of code evolution. GlnRS-IB was generated in eukaryotic systems and acquired in archaeal systems via horizontal gene transfers [

7]. At the base of code evolution, a dual function GluRS-IB was coupled with the Glu-tRNA

Gln amidotransferase to generate Gln-tRNA

Gln.

Column 4 of the code was the most favored column (tRNA-35C), explaining why glycine occupies column 4, row 4 (BCC anticodon; the most favored anticodon). Arginine occupies a 6-codon sector of the code that was invaded by serine. It may be that ornithine was the initial positively charged amino acid to enter the code [

78]. Ornithine can be converted to arginine in two steps. Ornithine is flexible similar to lysine. Arginine is more rigid and forms strong ion pairs to aspartic acid that are formed and broken in allosteric switching for many enzymes and proteins. Lysine entry into column 3 may relate to ornithine having been present in column 4 (i.e., initially, only a single CCU→CUU anticodon base change may have been required for ornithine or lysine jumping from column 4 into column 3).

Aromatic amino acids FYW are posited to have added late, across disfavored row 1 of the genetic code, perhaps initially as a now extinct PheRS-IC AARS [

8,

9,

11]. We posit that PheRS-IC was replaced by PheRS-IIC before LUCA to discriminate phenylalanine and tyrosine, which utilizes TyrRS-IC, which is closely related to TrpRS-IC.

When considered according to genetic code columns, our working model closely relates to the orders of addition proposed by others. Our model stresses the importance of coupling metabolism to tRNAome and genetic code evolution. For instance, multiple tRNA-linked metabolic reactions can be identified in code evolution. S→C, D→N and E→Q could be attributed to tRNA-linked chemistry. O→R (O for ornithine), F→Y and V→L may be other examples of tRNA-linked reactions in evolution of the code. In pre-life, metabolism and genetic code evolution were tightly coupled. As soon as isoleucine was encoded, methionine could be incorporated into the code. We posit that arginine, which occupies a 6-codon sector, entered earlier than proposed by others. This discrepancy may relate to the posited replacement of ornithine by arginine and the enhanced roles of arginine in allosteric shifts in sequence-dependent proteins.

Methionine occupies a 1-codon sector because methionine invaded a 4-codon isoleucine box. Differential modifications of wobble tRNA-34C to agmatidine (isoleucine) or 2’-O-methyl-C (methionine; elongation) and elimination of the UAU anticodon tRNA describe these events. Tryptophan occupies a 1-codon sector and shares a 2-codon box with a stop codon. Stop codons do not utilize a tRNA and are recognized instead as stop codons bound by protein release factors that interact with mRNA on the ribosome to terminate the reading frame [

79]. To split a 2-codon sector into two different amino acids presents problems that have not been solved in evolution.

16. Conclusions

Type I and type II tRNAs evolved chemically via highly ordered mechanisms during pre-life. Very likely, these steps could be reproduced in laboratories.

The mechanisms for chemical evolution of tRNAs can be extended to generate highly complex RNAs such as rRNAs.

Polyglycine is proposed to have been a primary aggregator of pre-life macromolecules and cofactors and also to have promoted the transition of lipids to protocells and protocells to cells. The utility of polyglycine to promote these chemistries could be reproduced in laboratories.

With coevolution of translation functions, mechanisms for evolution of the first proteins that were coevolved with the genetic code can be described. RNA ligations of similar or identical RNAs generated barrels. Refolding of barrels generated linear sheets (i.e., Rossmann folds). Class I AARS were initially generated by attachment of an N-terminal extension to a primitive GlyRS-IIA (i.e., by RNA ligation for replication).

A straightforward and rational working model for evolution of the genetic code has been proposed based initially on the chemical evolution of tRNA and the tRNA anticodon. The model is supported by the coevolution of tRNAomes and AARS enzymes. Strong predictions arise about the order of entry of amino acids into the code and, also, the positioning of amino acids in the code. tRNA-linked reactions were necessary for code evolution. Metabolism and code evolution were tightly coupled. Evolution was primarily within code columns. There was very little chaos in chemical evolution of the code.

By focusing on the prominence of tRNA in evolution of translation systems, the genetic code and life, we emphasize the central winning pathway. Our approach has been a top-down, sequence-based approach, so the evidence for our conclusions is largely embedded in tRNA sequences in living organisms. A bottom-up approach would be to create life in a test tube from pre-life components. Much very reasonable pre-life chemistry done in laboratories, however, may represent dead-end strategies. Pre-life chemistry must have been complicated and diverse, and many chemically evolved processes must have gone extinct with the first organisms around the time of LUCA (i.e., Polymer World and Minihelix World). tRNA was a molecule chemically evolved in pre-life that has survived, supporting life for ~4.2 billion years.

Figure 1.

Evolution of type II and type I tRNAs from ligation of three 31 nt minihelices. ACCA-Gly was a pre-life adapter molecule that could function alone or ligated to various RNAs including 31 nt minihelices and tRNAs. Type II tRNAs were formed by a single internal 9 nt deletion within ligated 3’ and 5’ acceptor stems. Type I tRNAs were formed by an additional 9 nt deletion in the V arm region. The purpose of the initial molecules was to synthesize polyglycine. Colors: green) 5’-acceptor stems and 5’-acceptor stem remnants; magenta) 17 nt D loop core; cyan-red-cornflower blue) 17 nt anticodon and T stem-loop-stem; yellow) 3’-acceptor stem and 3’-acceptor stem remnant (type I V loop). Red arrows indicate the sites of the 9 nt internal deletions. Red arrows with asterisks represent the more 3’ 9 nt internal deletion unique to type I tRNA. Blue arrows indicate U-turn loops. Some bases are emphasized using space-filling representation.

Figure 1.

Evolution of type II and type I tRNAs from ligation of three 31 nt minihelices. ACCA-Gly was a pre-life adapter molecule that could function alone or ligated to various RNAs including 31 nt minihelices and tRNAs. Type II tRNAs were formed by a single internal 9 nt deletion within ligated 3’ and 5’ acceptor stems. Type I tRNAs were formed by an additional 9 nt deletion in the V arm region. The purpose of the initial molecules was to synthesize polyglycine. Colors: green) 5’-acceptor stems and 5’-acceptor stem remnants; magenta) 17 nt D loop core; cyan-red-cornflower blue) 17 nt anticodon and T stem-loop-stem; yellow) 3’-acceptor stem and 3’-acceptor stem remnant (type I V loop). Red arrows indicate the sites of the 9 nt internal deletions. Red arrows with asterisks represent the more 3’ 9 nt internal deletion unique to type I tRNA. Blue arrows indicate U-turn loops. Some bases are emphasized using space-filling representation.

Figure 2.

The pre-life type II (top sequence) and type I (second sequence line) tRNA sequences. Interactions and sequence changes to support the tRNA fold are indicated. Red arrows indicate internal 9 nt deletion sites and end points. Red arrows with asterisks indicate processing of an early type II tRNA to a type I tRNA. See the text for details.

Figure 2.

The pre-life type II (top sequence) and type I (second sequence line) tRNA sequences. Interactions and sequence changes to support the tRNA fold are indicated. Red arrows indicate internal 9 nt deletion sites and end points. Red arrows with asterisks indicate processing of an early type II tRNA to a type I tRNA. See the text for details.

Figure 3.

The 17 nt D loop core was based on a UAGCC repeat (UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA). The sequence and an approximate structure of the D loop minihelix are shown. Colors are meant to be consistent between figures. GD8 forms the Levitt reverse Watson-Crick base pair to type I CV5 or type II CVn. Red AD12 was substituted by GD12 to form elbow contacts to the T loop. GD13 pairs with tRNA-56C.

Figure 3.

The 17 nt D loop core was based on a UAGCC repeat (UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA). The sequence and an approximate structure of the D loop minihelix are shown. Colors are meant to be consistent between figures. GD8 forms the Levitt reverse Watson-Crick base pair to type I CV5 or type II CVn. Red AD12 was substituted by GD12 to form elbow contacts to the T loop. GD13 pairs with tRNA-56C.

Figure 4.

The anticodon stem-loop-stem and the T stem-loop-stem are homologs. The blue arrow indicates the position of the U-turn. In tRNA, the T loop (UU/CAAAU) evolved to interact with the D loop at the elbow. The T stem-loop-stem is also very similar to the anticodon stem-loop-stem complement. Colors are meant to be consistent between figures. At the elbow: U55 interacts with GD12; GD13 binds C56; GD12 intercalates between A57 or G57 and A58. The bar above the figure indicates the stem-loop-stem structure (cyan-red-cornflower blue).

Figure 4.

The anticodon stem-loop-stem and the T stem-loop-stem are homologs. The blue arrow indicates the position of the U-turn. In tRNA, the T loop (UU/CAAAU) evolved to interact with the D loop at the elbow. The T stem-loop-stem is also very similar to the anticodon stem-loop-stem complement. Colors are meant to be consistent between figures. At the elbow: U55 interacts with GD12; GD13 binds C56; GD12 intercalates between A57 or G57 and A58. The bar above the figure indicates the stem-loop-stem structure (cyan-red-cornflower blue).

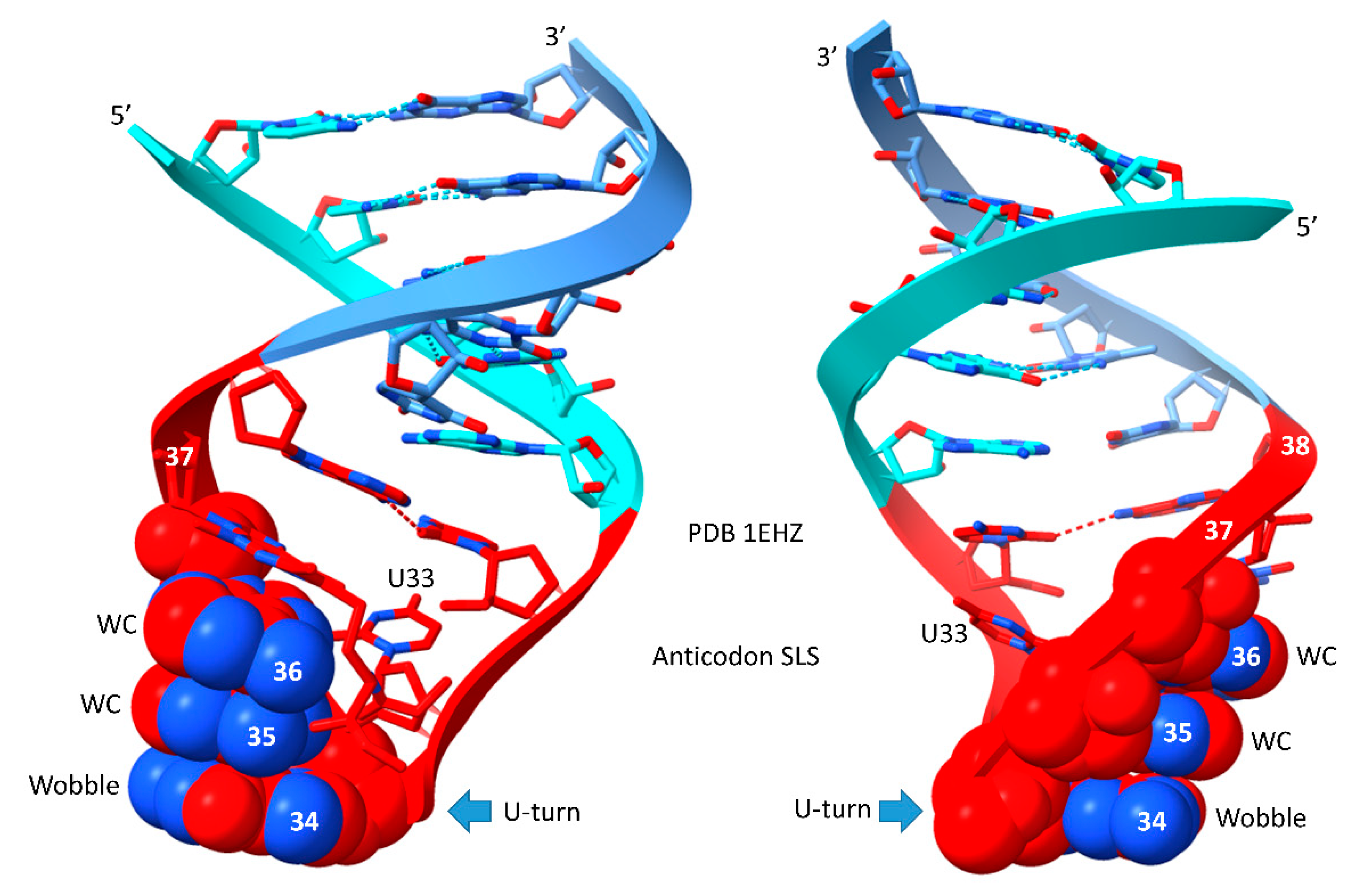

Figure 5.

The anticodon stem-loop-stem (two views). Colors and arrows are consistent between figures. WC for Watson-Crick.

Figure 5.

The anticodon stem-loop-stem (two views). Colors and arrows are consistent between figures. WC for Watson-Crick.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the type II V arm and alignment to the type I V loop. The tRNASer type II V arm single base insert may not be properly placed.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the type II V arm and alignment to the type I V loop. The tRNASer type II V arm single base insert may not be properly placed.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the 3’-D stem (5’-As*) and the type I tRNA V loop (3’-As*). Colors and arrows are consistent with other figures. Early sequences of the D stem are indicated.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the 3’-D stem (5’-As*) and the type I tRNA V loop (3’-As*). Colors and arrows are consistent with other figures. Early sequences of the D stem are indicated.

Figure 8.

Relationship of type II V arms to type I V loops in Archaea. The sequence alignment shows how type II V arms and type I V loops align to one another and their derivation from ligation of 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems. The tRNA

Leu (CAA) V arm of Pyrococcus horikoshii is shown [

43,

44]. Sequence logos of 105 14 nt archaeal tRNA

Leu V arms and 34 15 nt archaeal tRNA

Ser V arms are shown. In Archaea, tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser are discriminated by: 1) the distinct trajectories of the V arms (cyan asterisks); 2) the V

6-UAG-V

8 V arm end loop sequence determinant for tRNA

Leu (red asterisks); and 3) SerRS-IIA binding the V arm stems of tRNA

Ser with a trajectory set point score of one unpaired base (cyan asterisks).

Figure 8.

Relationship of type II V arms to type I V loops in Archaea. The sequence alignment shows how type II V arms and type I V loops align to one another and their derivation from ligation of 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems. The tRNA

Leu (CAA) V arm of Pyrococcus horikoshii is shown [

43,

44]. Sequence logos of 105 14 nt archaeal tRNA

Leu V arms and 34 15 nt archaeal tRNA

Ser V arms are shown. In Archaea, tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser are discriminated by: 1) the distinct trajectories of the V arms (cyan asterisks); 2) the V

6-UAG-V

8 V arm end loop sequence determinant for tRNA

Leu (red asterisks); and 3) SerRS-IIA binding the V arm stems of tRNA

Ser with a trajectory set point score of one unpaired base (cyan asterisks).

Figure 9.

ACCA-Gly was the primordial adapter molecule. See the text for details.

Figure 9.

ACCA-Gly was the primordial adapter molecule. See the text for details.

Figure 10.

A proposed role for polyglycine in the pre-life world. Polyglycine is posited to have been the main aggregator of macromolecules that led to chemical selection, protocell enhancements and formation of the first true cells. A list of some of the components aggregated by polyglycine that contributed to assembly of the first cells is shown. PTC for peptidyl-transferase center.

Figure 10.

A proposed role for polyglycine in the pre-life world. Polyglycine is posited to have been the main aggregator of macromolecules that led to chemical selection, protocell enhancements and formation of the first true cells. A list of some of the components aggregated by polyglycine that contributed to assembly of the first cells is shown. PTC for peptidyl-transferase center.

Figure 11.

A model for chemical evolution of the first cells.

Figure 11.

A model for chemical evolution of the first cells.

Figure 12.

tRNAomes, tRNA modifications and tRNA-linked reactions in evolution of the genetic code.

Figure 12.

tRNAomes, tRNA modifications and tRNA-linked reactions in evolution of the genetic code.

Figure 13.

Barrels and sheets.

Figure 13.

Barrels and sheets.

Figure 14.

AARS, ribosomes and translation factors.

Figure 14.

AARS, ribosomes and translation factors.

Figure 15.

Splitting amino acids by genetic code columns helps to explain the order of addition of amino acids into the code. In the approximate order, we provide our determinations and two versions by another group [

13]: 1) Early and Late additions; and 2) another determination based on comparisons of amino acid usages at pre-LUCA and LUCA. tRNA-35 and tRNA-36 anticodon bases are indicated. Breaking the genetic code into code columns causes the information to make better sense.

Figure 15.

Splitting amino acids by genetic code columns helps to explain the order of addition of amino acids into the code. In the approximate order, we provide our determinations and two versions by another group [

13]: 1) Early and Late additions; and 2) another determination based on comparisons of amino acid usages at pre-LUCA and LUCA. tRNA-35 and tRNA-36 anticodon bases are indicated. Breaking the genetic code into code columns causes the information to make better sense.

Figure 16.

Correlation of amino acid additions with the archaeal genetic code. AARS enzymes are colored to emphasize patterns of evolution within code columns. Grey shading indicates an AARS editing active site separate from the aminoacylating active site. Blue shading indicates an editing reaction within the AARS aminoacylating active site. Wobble tRNA-34 bases shown in red are not utilized in Archaea. tRNA-34U in blue indicates that the Elp3 acetyltransferase-initiated modification (i.e., tRNA-34cnm5U) was necessary to suppress superwobbling. tRNA-37m1G was necessary to read tRNA-36A. tRNA-37t6A was necessary to read tRNA-36U. CAU with C modified to agmatidine encoded isoleucine. CAU (C unmodified (initiation) or C lightly modified (elongation; Cm)) encoded methionine.

Figure 16.

Correlation of amino acid additions with the archaeal genetic code. AARS enzymes are colored to emphasize patterns of evolution within code columns. Grey shading indicates an AARS editing active site separate from the aminoacylating active site. Blue shading indicates an editing reaction within the AARS aminoacylating active site. Wobble tRNA-34 bases shown in red are not utilized in Archaea. tRNA-34U in blue indicates that the Elp3 acetyltransferase-initiated modification (i.e., tRNA-34cnm5U) was necessary to suppress superwobbling. tRNA-37m1G was necessary to read tRNA-36A. tRNA-37t6A was necessary to read tRNA-36U. CAU with C modified to agmatidine encoded isoleucine. CAU (C unmodified (initiation) or C lightly modified (elongation; Cm)) encoded methionine.