1. Introduction

In recent years, remote work has experienced a significant increase, driven by the need to balance personal and professional life. This shift has been made possible by technological advances that allow employees to perform their tasks from anywhere [

2]. However, remote work also presents major challenges, such as lack of face-to-face interaction, distraction, difficulty in creating a suitable work environment, and blurred boundaries between personal and professional life [

3]. To address these challenges, virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a promising technology. VR not only improves understanding of the environment in remote meetings [

21], but also facilitates access to otherwise difficult to obtain resources [

5] and allows for the creation of immersive training scenarios [

6,

7]. In addition, VR increases immersion and the sense of embodiment [

8,

9], which can improve efficiency and reduce distractions during virtual meetings. However, integrating VR also has drawbacks, such as virtual motion sickness and other issues associated with prolonged use of VR hardware, including eye strain, stress, and mental overload [

10,

11]. These symptoms may depend on factors such as demographics, movement illusion, and viewing mode [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. A relevant approach to increasing immersion in virtual environments is the use of avatars, digital representations of users, which facilitate interaction [

17]. However, using avatars can introduce additional challenges that affect the user experience and modify behavior and attitudes [

18,

23]. Hyper-realistic avatars, while more closely resembling real people, can create insecurities in users [

20], while avatar personalization can influence behavior or even trigger psychological issues, such as body dysmorphia [

21,

22,

23]. Opting for realistic avatars without reaching hyper-realism can mitigate some of these issues while preserving an acceptable sense of embodiment and control over the avatar [

24]. To better understand these effects, two studies on the use of avatars have been conducted. Study 1 explored how users relate to different types of avatars they control themselves. This study evaluated three types of avatar: hyperrealistic, nonrealistic, an avatar representing another person of the same gender, and another person using the user’s avatar, analyzing their impact on embodiment, technostress, usability, and privacy. Study 2 was designed to complement this research, focusing on how users perceive interaction when the interviewer uses different types of avatar. This study included hyper-realistic, non-realistic, different-gender avatars, and an avatar representing the participant. It was aimed at analyzing how these representations affected the credibility of the interviewer, the comfort of the participants, the techno-stress and the perception of privacy. By combining findings from both studies, the goal is to provide a broader view of the benefits and limitations of using avatars in different roles within virtual environments, as well as their impact on social and professional interactions.

2. Study Design

The study was structured into two parts, each with a different focus on evaluating the use of avatars in virtual meetings. In Study 1 (SE1), participants controlled their own avatars, while in Study 2 (SE2), the interviewer used different types of avatars. Both studies were conducted in a controlled environment that simulates virtual meeting scenarios.

2.1. Participants

Inclusion criteria included individuals between 18 and 65 years of age from Spain and Germany with previous experience in online meetings or virtual reality systems. Participants were required to have sufficient cognitive, auditory and / or visual abilities to read, write, or hold conversations in the study language. Exclusion criteria included null or very limited IT skills and sensory disorders that would impede participation in the study (e.g., blindness or deafness). The final sample consisted of the following.

Study 1: 42 participants (22 men and 20 women) between the ages of 22 and 62, with an average age of 32.4 years (SD = 9.3). Most participants had a high educational level, with 71.5% (30 participants) holding a university degree or higher. Regarding video conferencing experience, 69% reported frequent use, 23% had regularly used VR systems, while 14.3% had never used VR before this study.

tem Study 2: 40 participants, equally divided into 25 men and 15 women, aged between 20 and 38 years old, with an average age of 28.2 (SD = 4.7). All participants had a high level of education, 83% having a university degree or pursuing a degree. Regarding video conferencing use, 58% reported frequent use and 43. 5% had occasionally used a virtual reality system.

2.2. Materials

To simulate the use of avatars with varying appearances in an online meeting, the Geometry-Guided GAN for Face Animation (G3FA) was utilized [

25]. This model, which has shown superior performance compared to other state-of-the-art real-time facial animation methods, enables the integration of 3D information into face animation using only 2D images. This significantly enhances the image generation capabilities of the talking head synthesis model.

In Study 1, participants used three types of avatars: a hyper-realistic avatar of the participant; a non-realistic avatar (cartoon of the participant); a hyper-realistic avatar of another person of the same gender; and a final test where another person used the participant’s avatar. In Study 2, the interviewer used the following avatars: a hyper-realistic avatar of a person of the same gender as the participant; a hyper-realistic avatar of a person of the opposite gender; a non-realistic (cartoon) avatar; a hyper-realistic avatar of another person; and a hyper-realistic avatar representing the participant. The VToonify tool [

32] was used to generate non-realistic avatars, allowing the creation of animated-style images from real photographs.

2.3. Variables and Measurement Instruments

The evaluation protocol consists of three parts: user information collected before the study; information collected during each test; and data collected at the end of the study.

2.3.1. User Profile

Before starting the test, demographic information (gender, age, educational background) and previous experience with online meetings and virtual reality technology in various contexts (work, education, leisure) were collected.

2.3.2. Measures Obtained at the End of Each Test

A 5-point Likert scale questionnaire adapted from the System Usability Scale (SUS) [

26] was used to collect user feedback at the end of each test. In addition, a psychometric approach assessed the embodiment [

1] toward the avatar’s face, focusing on ownership, agency, and change [b19]. Questions on privacy were also included, adapted from a validated technostress test [

28]. All questions were tailored for each study to refer to the user or the interviewer. For Study 2, location ownership could not be assessed, as the user did not control the avatar. The technostress caused was also not assessed, as these questions are more related to the stress, anxiety, or pressure that self-representation might cause. Instead, five questions were added to evaluate the impact of the avatar on the credibility of the interviewer and the trust that the participant had in the interaction. These questions followed the same scale as the others and were adapted from a validated technostress test [

28]. Additionally, for the final test in Study 2, these questions focused on the use of a different-gender avatar.

Appendix A presents the questions used to collect data on embodiment, privacy, and technostress in Study 1 (

Table A1), as well as embodiment, technostress, and gender in Study 2 (

Table A2).

2.3.3. Final Study Measures

At the end of all the tests, the participants completed a final test composed of three parts:

Study 1: Technostress caused by avatar use was evaluated using the same scale as the individual tests (SUS) and adapted from a validated test [

27]; acceptability of using these types of avatars in different contexts—work, education, and leisure—was also assessed. Questions, again using the SUS scale, were adapted from a validated acceptability questionnaire [

29,

30,

31]; finally, preferences for avatar type were evaluated in six scenarios: team meetings or interactions with external participants, educational settings as a student or teacher, and recreational activities with strangers or friends.

Study 2: In the same way as in the first study, the test included the evaluation of acceptability and avatar preferences in the same scenarios. In addition, four open questions evaluated the general experience, any discomfort caused, and the use of avatars of different gender.

2.4. Hardware

The studies were carried out on computers equipped with NVIDIA RTX3060 graphics cards, ensuring smooth performance and low latency in avatar rendering.

2.5. Procedure

The study for each participant was conducted through the following phases:

2.5.1. Pre-Study

Participants were informed about the study’s purpose and signed an informed consent form. Then, they completed an initial questionnaire to gather demographic data and previous experience.

2.5.2. Study

In both studies, participants interacted with the interviewer in several different tests, each featuring a different type of avatar. The interactions lasted between 2 and 3 minutes, simulating conversations in virtual meetings.

-

Avatar Familiarization: Before each interaction, participants were briefly introduced to the avatar that either the interviewer or the participant would use in the session.

- -

S1: Hyper-realistic, non-realistic, hyper-realistic avatar of another person, and a test as a spectator while another user used their avatar.

- -

S2: Hyper-realistic, non-realistic, hyper-realistic avatar of another person of the same gender, hyper-realistic avatar of a person of a different gender, and a hyper-realistic avatar of the participant.

Simulated Interview: Participants engaged in a conversation with the interviewer, designed to make them focus on the interaction rather than on the avatar. They were allowed to change the topic or avoid questions if they wished. In S1, the interviewer positioned themselves behind the users to minimize distraction, allowing users to maintain focus on the avatar. The interview aimed to stimulate conversation and divert attention from the avatar by asking personal questions where participants could expand freely. In S2, the interview took place via video conference in separate rooms, with questions structured to simulate a job interview.

Post-interaction Questionnaire: At the end of each interaction, participants completed a brief questionnaire to evaluate each avatar type.

2.5.3. Post-Study

After completing all tests, participants completed the final questionnaire.

3. Results

3.1. User’s Perception of Embodiment

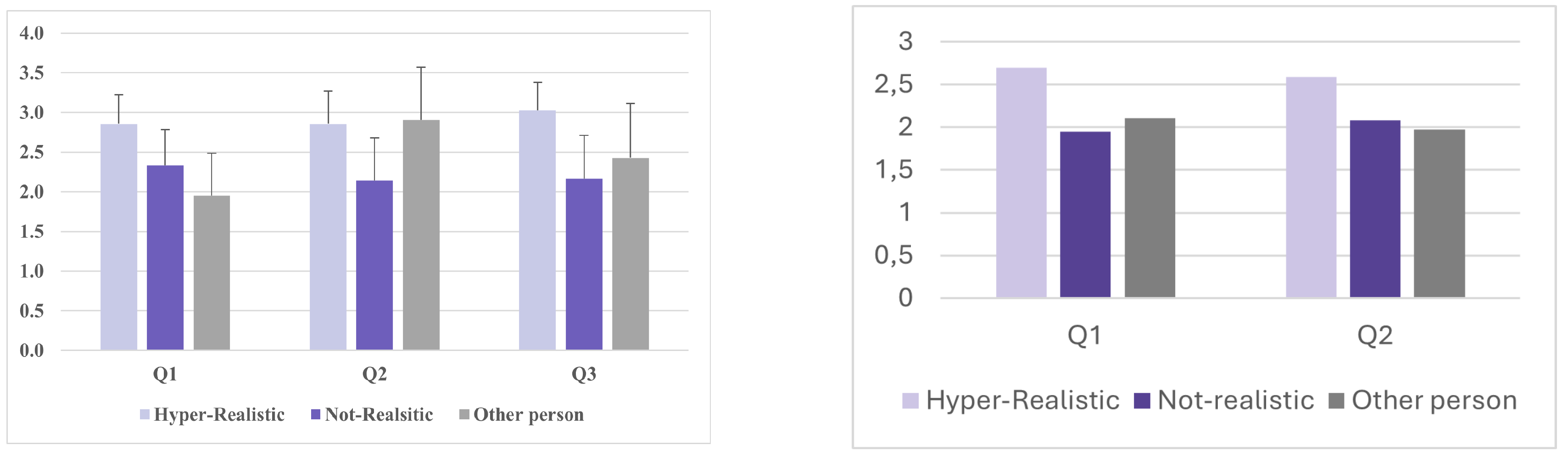

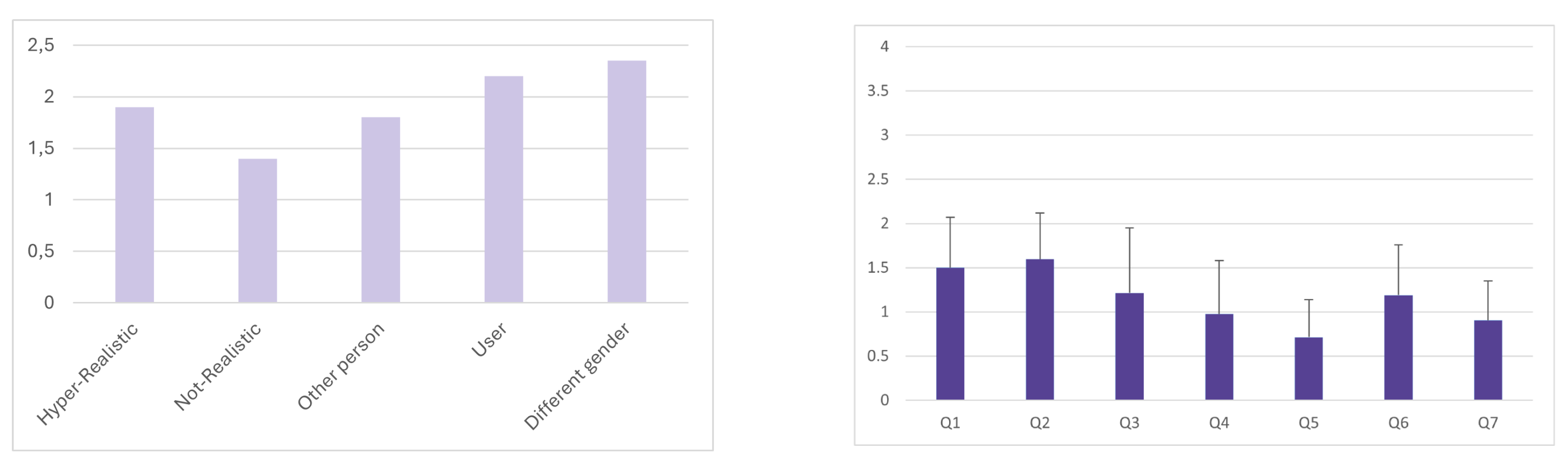

In both studies, embodiment perception was a key dimension in measuring the effectiveness of avatars. The questionnaire elements were classified into three properties that influence this perception: ownership, agency, and change (the latter not applicable to study 2). In terms of ownership,

Figure 1 illustrates that both hyper-realistic avatars in both studies achieved a greater resemblance to human faces than the non-realistic avatar (Q2). Participants particularly attributed a stronger sense of facial ownership to their hyper-realistic avatars in questions about facial features (Q1 and Q3).

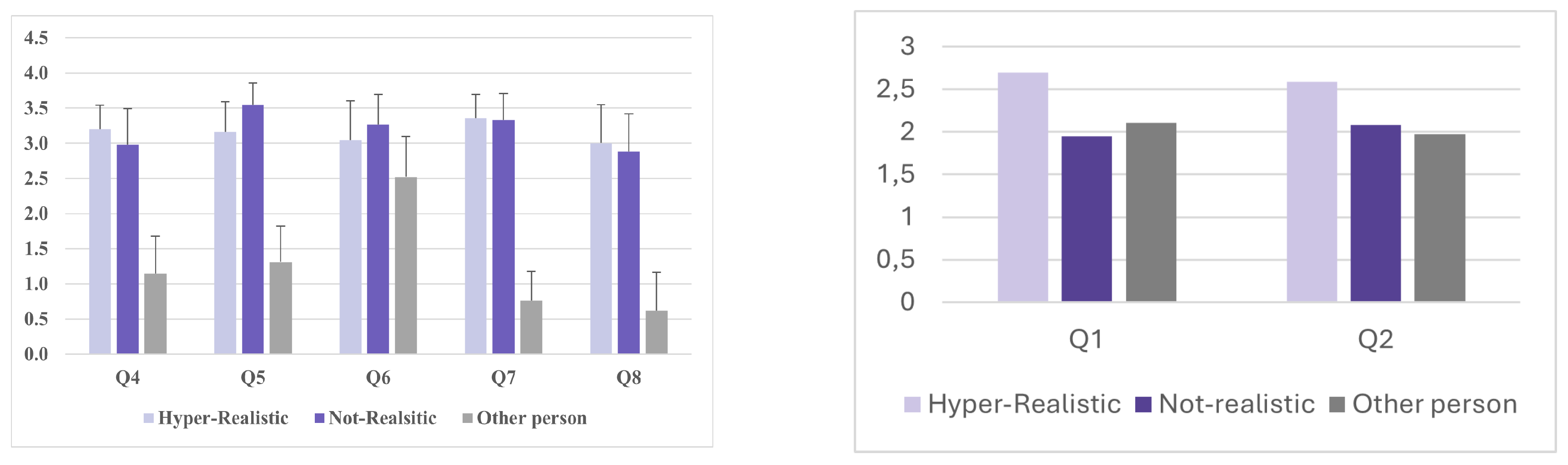

For agency,

Figure 2 shows that, in Study 1, users’ own avatars received higher scores across all questions. The hyper-realistic avatar scored highest on questions related to avatar movement (Q4, Q7, and Q8), while the non-realistic avatar scored higher on questions related to enjoyment (Q5) and comfort (Q6). Conversely, the avatar representing another person did not score significantly high in any question, except for comfort. In Study 2, the difference between avatar types was much more balanced, although the participant’s own hyper-realistic avatar retained slightly higher values. It is notable that the question about feeling like they were speaking with a real person rather than a representation (Q4) received a clearly lower value.

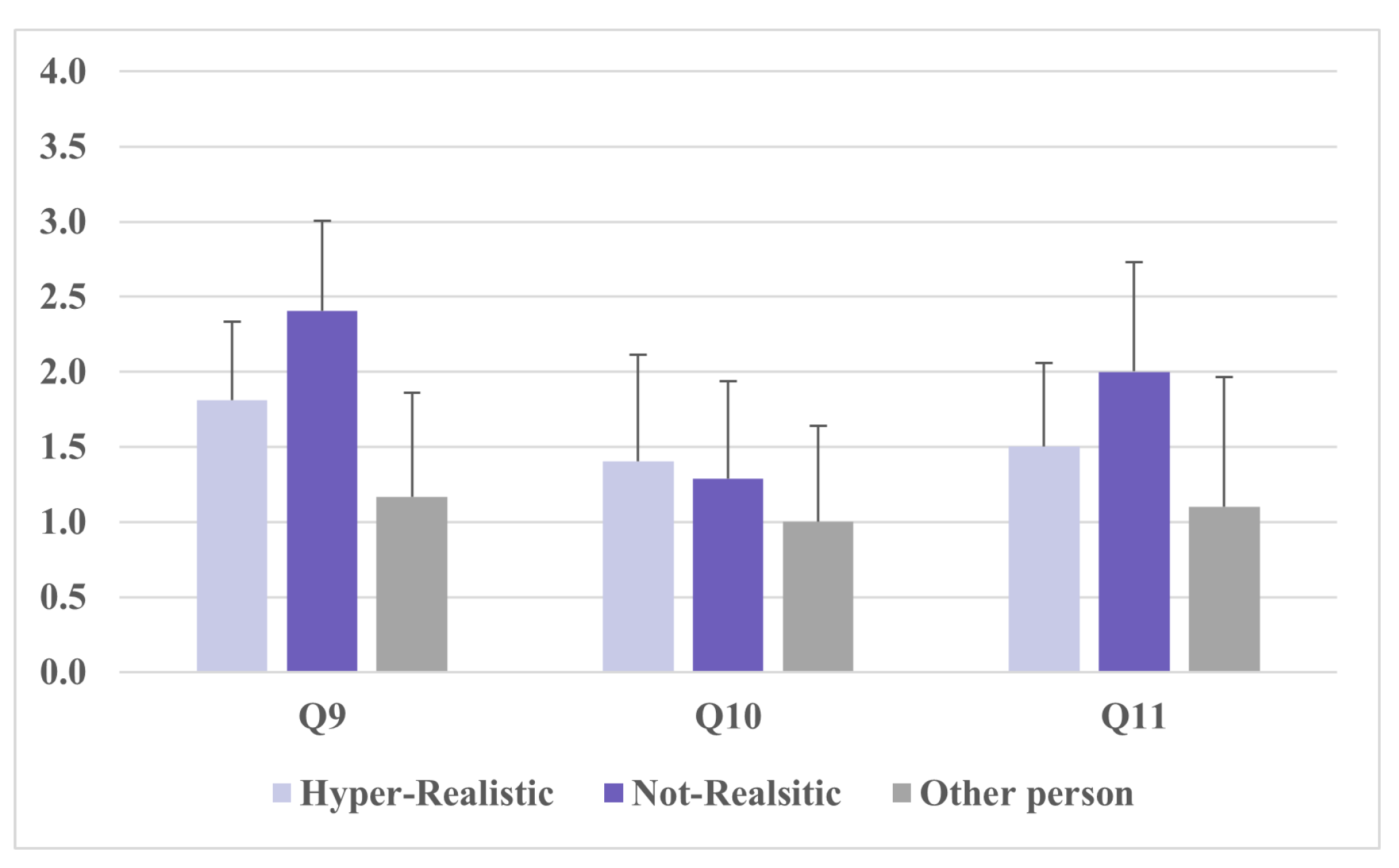

Lastly, the results for change in Study 1 are presented in

Figure 3. In all three cases, the values remained relatively low (below 2.5). However, the non-realistic avatar showed a pronounced sense of change. Interestingly, the hyper-realistic avatar led more users to question changes in their own face (Q10). Additionally, the avatar that did not belong to the user received the lowest scores across the three questions.

A correlation analysis with sociodemographic data and prior experience was performed using Spearman’s correlation. Results indicated no significant correlation with age, gender, education level, or previous videoconferencing experience. However, prior experience with virtual reality showed a correlation, as displayed in

Table 1, where the Agency factor in Study 1 demonstrated improvement with prior VR experience, suggesting a greater sense of control over the avatar with increased VR exposure. No significant correlations were found in Study 2.

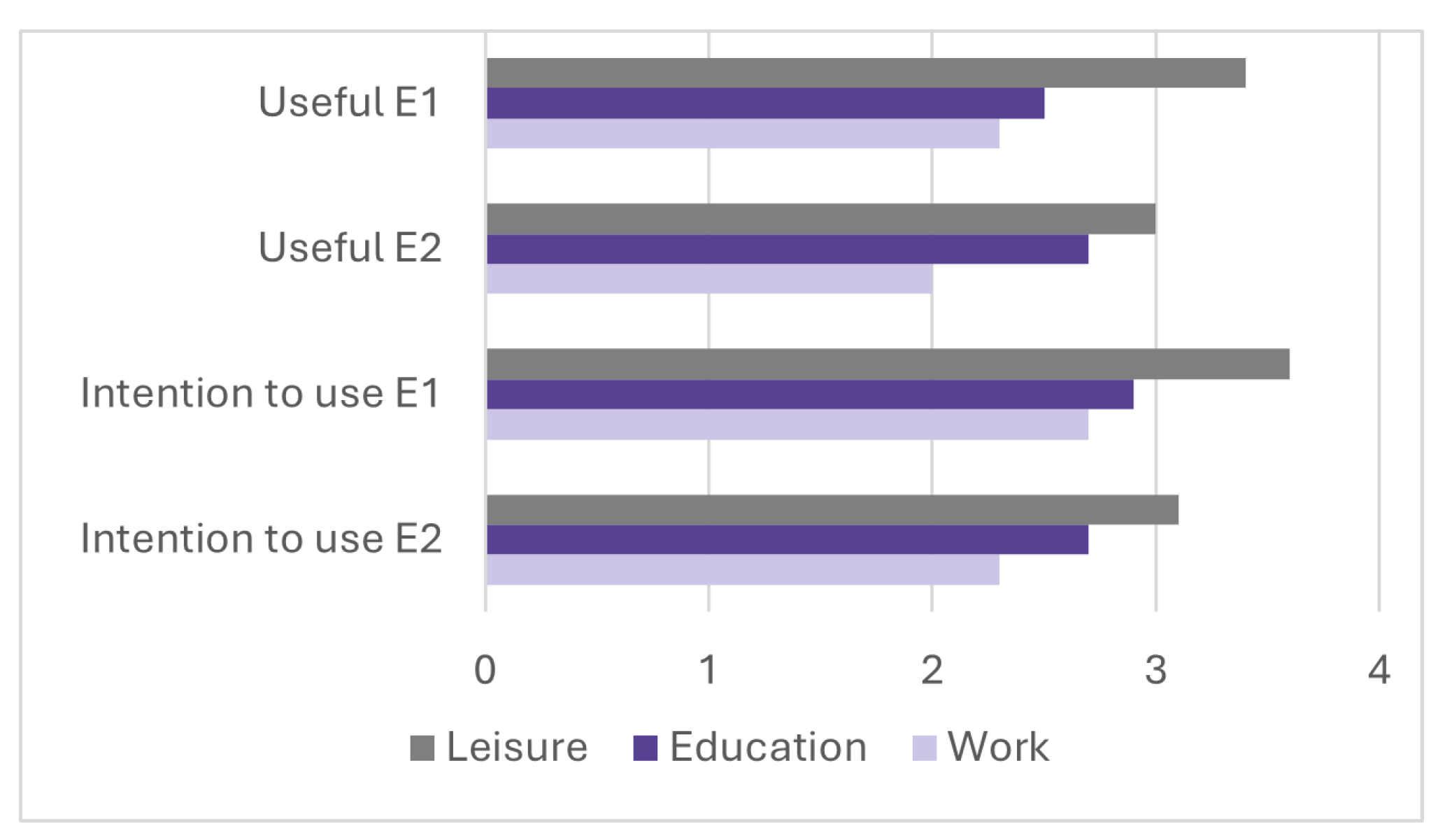

3.1.1. Credibility and Confidence

As shown in

Figure 4, in Study 2, participants generally felt that the avatar did not cause a notable lack of credibility or trust. However, the participant’s own hyper-realistic avatar scored below average on all questions. On the other hand, the lowest-scoring avatar was the non-realistic one. In a Spearman correlation analysis between results and prior experience, a negative correlation was again found between prior VR experience and question Q5 (r=-498; p=0.008), indicating that users with VR experience had greater confidence when interacting with an avatar. Regarding the relationship between credibility and trust with embodiment properties, a significant negative correlation was found with the sense of ownership. The resulting values are shown in

Table 2, suggesting that the greater the sense that the avatar belongs to the interlocutor, the higher the credibility and confidence.

3.1.2. Privacy

In Study 1, users did not express concern about privacy for the first three avatars (with values below 0.5 on a scale of 0 to 4). However, this increased to 1.5 when they saw that others could use their avatar. In Study 2, higher privacy concern wasconcerns were evident from the first avatar.

Figure 5 (left), which presents the results of the second study, shows that hyper-realistic avatars generated more concern than the non-realistic one, with concerns increasing with the use of the participant’s own avatar and gender changes.

To further explore the correlation between privacy concerns and embodiment perception, a Spearman correlation analysis was conducted, with detailed results shown in Table III. The table shows a correlation between privacy concerns and the three embodiment factors. In Study 1, there was a notable correlation between hyper-realistic avatars and the sense of change (r=0.575; p=0.001) and, to a lesser extent, the sense of control (r=0.397; p=0.014). In Study 2, a stronger correlation was found between the sense of control and avatars representing another person (r=0.377; p=0.018) and the participant’s own avatar (r=0.460; p=0.003). Despite being a low correlation, both types of avatars negatively correlated with the sense of ownership. However, the most notable correlation was with the use of an avatar of a different gender, showing discomfort (r=0.745; p=0.0001).

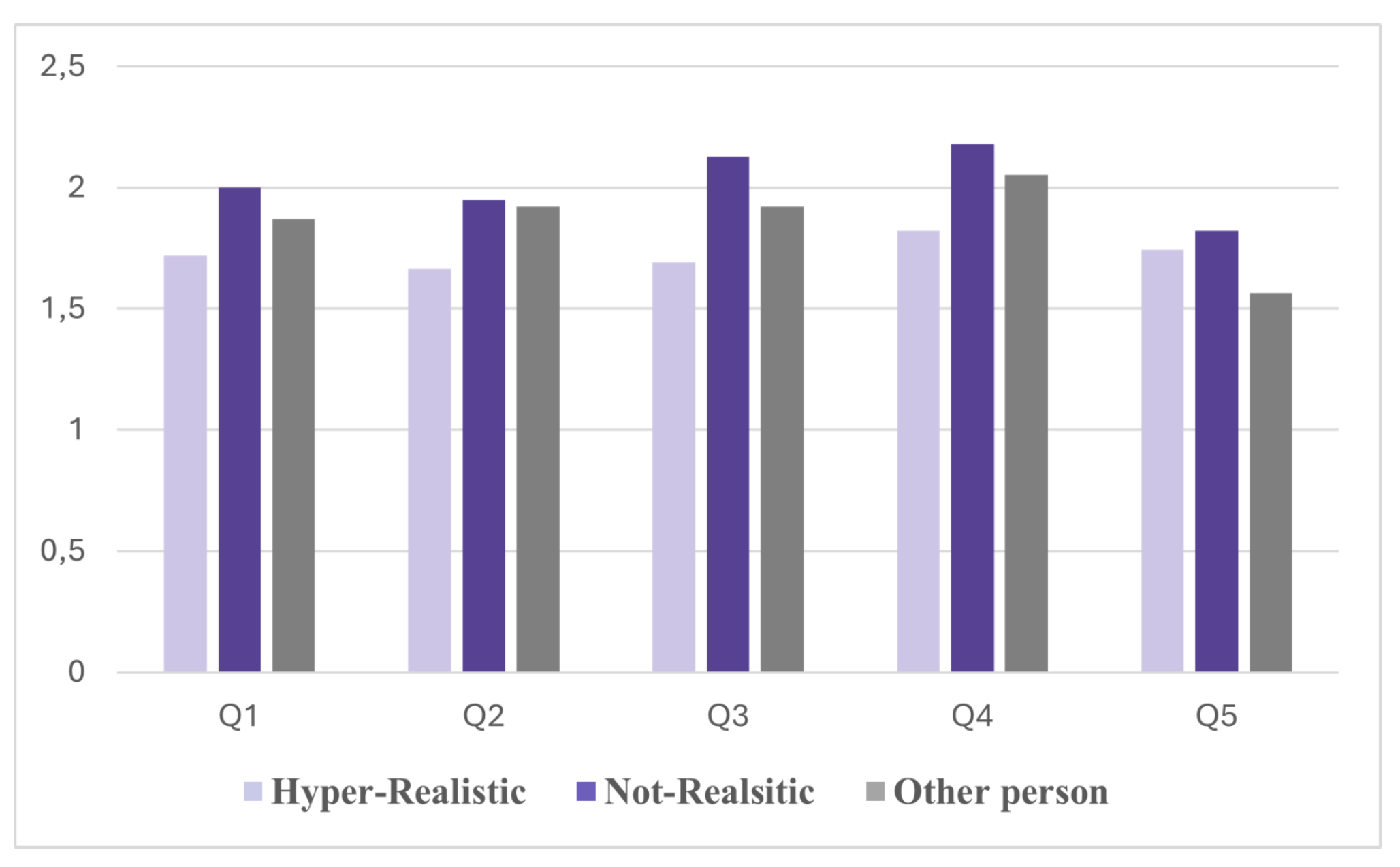

3.1.3. Technostress

Figure 5 (right) provides a visual comparison of questionnaire responses, as shown in Table I, offering insights into levels of technostress. Specifically, questions 4, 5, and 7, related to privacy, fatigue, and self-esteem while using avatars, showed the lowest values, all below 1. In contrast, questions 1 and 2, focused on the avatar’s appearance, scored higher, exceeding 1.5. These findings suggest that merely using avatars does not inherently induce high levels of technostress. However, additional analysis using Spearman’s correlation revealed significant associations:

Gender correlated with questions 6 (r=0.359; p=0.05) and 7 (r=0.298; p=0.018), indicating a greater concern among women regarding possible judgment or discrimination based on avatar appearance, aligning with previous research on appearance-related anxiety in video conferencing.

Age correlated with questions 1 through 5 (Average: r=0.319; p=0.045), indicating higher concerns among younger participants regarding avatar appearance, privacy, and fatigue, consistent with existing literature.

Videoconferencing experience correlated with apprehension about expressing one’s true personality (r=0.377; p=0.014), suggesting that more experience amplifies concerns in this domain.

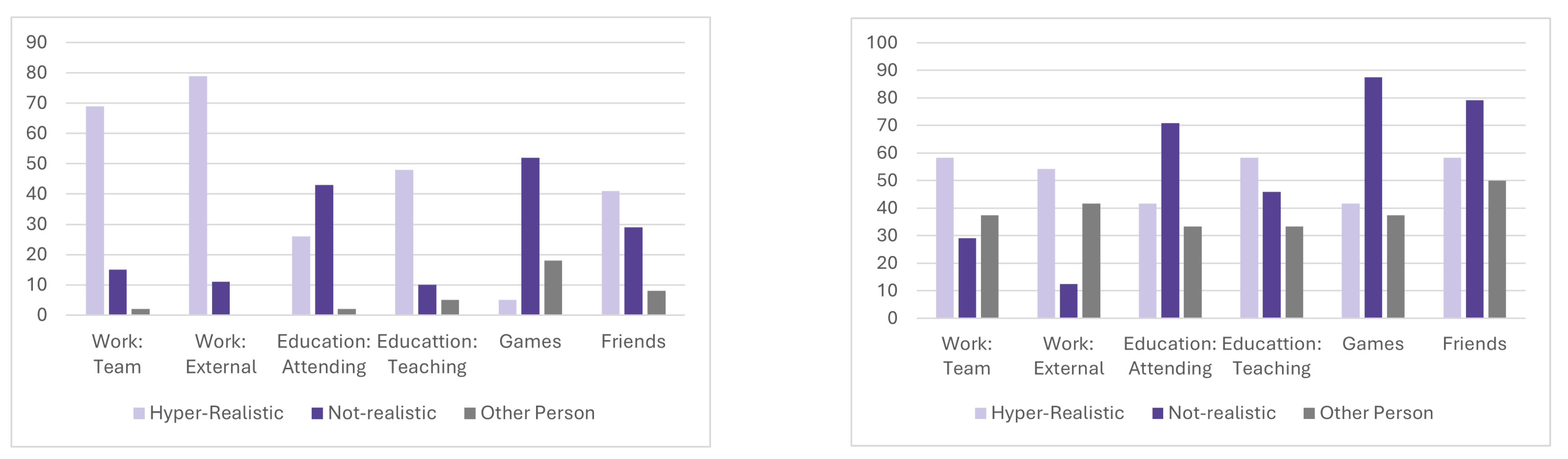

4. Acceptability

As shown in

Figure 6, users perceived avatar technology as useful in both educational and leisure settings in both studies, with ratings above 2.5. However, uncertainty remains about their effectiveness in the workplace, although users still recognize its utility (S1: 2.3; S2: 2). For intention to use, the effect is similar: scores are higher than for utility, but the same trend persists, with leisure scoring the highest and work the lowest.

To discern factors influencing users’ willingness to adopt avatar systems, a Spearman correlation analysis was conducted. Initially, the analysis considered prior experience and demographic data. In the first study, a positive correlation with previous VR experience was observed in the first study (Work: r=0.397, p=0.009; Education: r=0.399, p=0.009; Leisure: r=0.339, p=0.009). In contrast, in the second study, this correlation was only significant for education and leisure (Education: r=0.459 p=0.024; Leisure: r=0.417, p=0.004). For embodiment factors, ownership emerged as significant in determining perceived usefulness of avatars in both work and educational contexts, thus influencing the intention to use them. Detailed results are provided in

Table 3.

4.0.1. Avatar Preferences

Figure 7 (left) presents a comparative analysis of avatar preferences across different settings in Study 1. In workplace scenarios, users preferred avatars representing themselves, ideally with the highest possible image quality. This preference increased with the seriousness of meetings. Similarly, in educational contexts, particularly regarding educators, users favored a hyper-realistic avatar of themselves (47.6%). For students, self-representation was also preferred as they progressed. In leisure activities, preferences varied depending on the activity. When interacting with friends, users prioritized their hyper-realistic avatar. Conversely, in settings requiring interaction with both acquaintances and strangers, such as gaming environments, users preferred non-realistic avatars (52.4%).

Similarly, in Study 2, users preferred interacting with a hyper-realistic avatar in work settings, ideally a real-life likeness. In educational settings, as students, they preferred non-realistic avatars, while as teachers, they chose hyper-realistic avatars of themselves. In leisure settings, users preferred interacting with non-realistic avatars, although the difference between a non-realistic avatar and hyper-realistic avatars was smaller when interacting with friends. This comparison is shown in

Figure 7 (right).

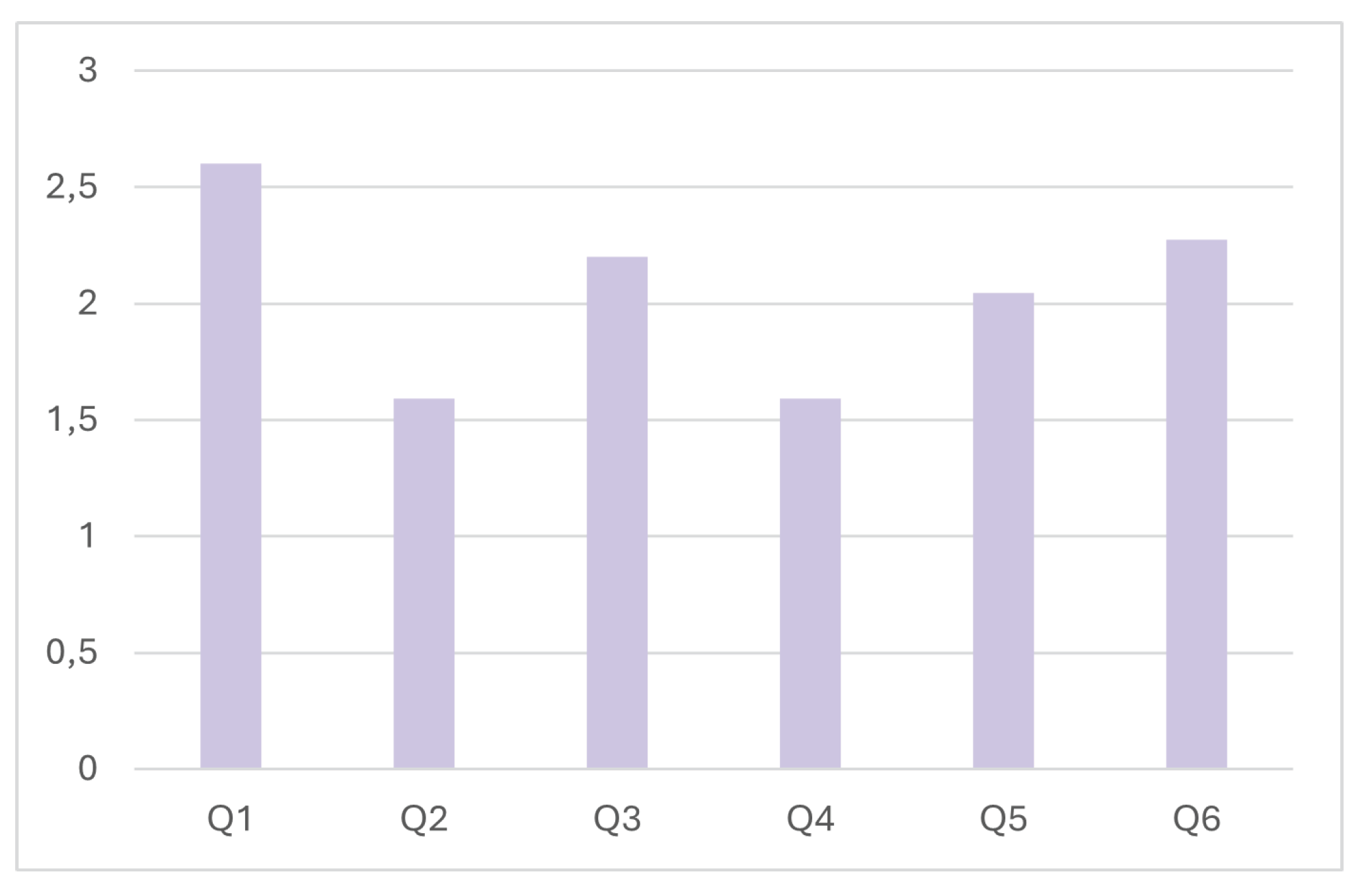

4.0.2. Use of Different-Gender Avatars

In Study 2, an additional test involved using an avatar of a different gender. Results showed that this test scored lower than the others on both embodiment properties (below 1.5 on a scale of 0 to 4), particularly the question about feeling like they were speaking with a real person (0.85). Regarding questions on credibility and trust, results are displayed in

Figure 8, showing that users experienced more issues interacting with the interviewer (2.6), felt increased discomfort (2.2), and had higher privacy concerns (2.3).

Additionally, to better understand user preferences when interacting with another person, participants could select whether they preferred interacting with a male or female avatar. Results based on user gender are found in

Table 4. For men: in the workplace, they preferred interacting with a male avatar; in education, they mostly preferred male avatars; and in leisure, where the preference for another person’s avatar increased, the preference was for both genders, with a greater tendency toward female avatars when interacting with strangers. For women, the number of users who preferred another person’s avatar was considerably lower. Notably, in leisure, there was no gender preference for the avatar they interacted with, but in other settings, they preferred either both genders or male avatars.

Additionally, most users mentioned in open-ended questions that interacting with an avatar whose voice did not match the appearance felt less serious and initially distracting until they grew accustomed to it.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the use of different types of avatar in work, educational and recreational settings, evaluating user perceptions of embodiment, acceptability, techno-stress, privacy, and preferences. Two studies were conducted: in the first, participants controlled their own avatars, while in the second, an interviewer used varied avatars. Both studies included hyper-realistic and non-realistic avatars, with variations in gender and identity.

The findings indicate that hyper-realistic avatars are perceived as more effective in generating a greater sense of embodiment, especially when the avatar resembles the user. This embodiment perception positively influenced the perceived utility and intention to use avatars in work and educational settings, where users preferred to interact with avatars that resembled themselves. In recreational settings, however, users showed a preference for non-realistic avatars, particularly in interactions with strangers or in less formal situations.

The study validated the importance of the sense of embodiment in avatar use, indicating that higher embodiment enhances user perceptions of avatar utility and their intention to use them. Therefore, strategies aimed at enhancing ownership and control while minimizing perceptions of bodily alteration in avatars are crucial for maximizing benefits. In particular, avatars that closely resemble the user improved ownership and control while reducing the sense of change.

Although technostress related to avatar use was relatively low, concerns about avatar appearance, especially among younger users, highlight potential insecurities regarding physical appearance. Privacy concerns also emerged, with users expressing increased apprehension when their avatars were used by others. Addressing these concerns, particularly in contexts where confidentiality is paramount, will be essential for the widespread adoption of avatar technologies. In other words, while initial results indicate low concern, this concern may increase over time due to privacy perceptions regarding the information used to create avatars, which could potentially be sold or stolen. This issue will be crucial in any technology that utilizes avatars, especially in settings where confidentiality is critical, such as in the workplace. Therefore, maintaining transparency in data usage and security would be key.

Results showed that the type of avatar used by the interviewer influences participants’ perception of credibility and trust. Hyper-realistic avatars of the user or of another person of the same gender scored higher for credibility, whereas non-realistic avatars generated greater discomfort and a perception of reduced professionalism. This finding suggests that, in professional settings such as job interviews or formal presentations, it is essential to use avatars that maximize credibility and trust in the interaction.

Although a general preference for hyper-realistic avatars was observed in the workplace, the results suggest gender differences in participant preferences. Women, in general, showed greater concern about avatar appearance and its potential impact on others’ perceptions, while men tended to feel more comfortable interacting with same-gender avatars in work and educational contexts. These results suggest that gender differences should be considered when designing avatars for professional environments to ensure all users feel comfortable and confident interacting with this technology.

A relevant aspect that emerged from the findings is the concern about the psychological effects of excessive avatar customization, particularly the risk of body dysmorphia. The ability to modify avatar appearance may trigger insecurities about body image, especially among younger users, suggesting the need to set limits on customization to avoid unrealistic expectations regarding physical appearance. This finding highlights the importance of designing avatars that are balanced and faithful representations of users without causing self-esteem issues.

In conclusion, avatars have significant potential to enhance virtual interactions, especially in professional and educational settings. By prioritizing strategies to enhance embodiment, addressing privacy and appearance concerns, and design avatars that balance realism with comfort, avatars can become invaluable tools for improving virtual interactions and user experiences. Further research exploring perceptions of opposite-gender avatars, taking gender identity into account, examining longer usage periods, and assessing their impact on group dynamics will offer deeper insights into the potential and limitations of this technology.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: C.G. and A.G.-P.; data collection: C.G. and A.J.; software: A.J.; analysis and interpretation of results: C.G.; draft manuscript preparation: C.G. and A.J.; review and editing, A.G.-P. and A.P.; project administration, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EU project CORTEX2 (grant agreement: N° 101070192).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Study 1 questions.

Table A1.

Study 1 questions.

| |

Property |

| Q1 |

It felt like the virtual face was my face. |

| Q2 |

The virtual face felt like a human face. |

| Q3 |

I had the feeling that the virtual face belonged to me. |

| |

Agency |

| Q4 |

The movements of the virtual face seemed to be my own

movements. |

| Q5 |

I enjoyed controlling the virtual face. |

| Q6 |

I have felt comfortable using the virtual face. |

| Q7 |

I felt as if I was causing the movement of the virtual face. |

| Q8 |

The movements of the virtual face were synchronous with |

| |

my own movements. |

| |

Change |

| Q9 |

I had the illusion of owning a different face from my own. |

| Q10 |

I felt the need to check if my face really still looked like

what I had in mind. |

| Q11 |

I felt as if the form or appearance of my face had changed. |

| |

Privacy |

| Q12 |

I feel that the use of this type of avatar is an intrusion

into my privacy. |

| Q13 |

I feel that this kind of avatar reveals private personal

information without my consent. |

| |

Technostress |

| Q1 |

Do you feel or would you feel pressured or stressed about maintaining a |

| |

"perfect" image or appearance through your avatar? |

| Q2 |

Do you feel or think you would feel anxiety or stress when comparing your |

| |

avatar to other people’s avatars in virtual environments? |

| Q3 |

Do you experience or think that you would experience difficulties in |

| |

expressing your true identity or personality through your avatar? |

| Q4 |

Do you or would you feel uncomfortable or stressed about the lack of privacy or |

| |

the potential exposure of your real identity while using an avatar? |

| Q5 |

Do you feel or think you would feel that using avatars in virtual environments |

| |

exhausts you emotionally or mentally? |

| Q6 |

Do you experience or think you would experience worries or stress related to the |

| |

possibility of your avatar being judged or discriminated against by other users? |

| Q7 |

Do you feel or think that you would feel that the use of avatars in virtual |

| |

environments negatively affects your self-esteem or self-confidence? |

Table A2.

Study 2 questions.

Table A2.

Study 2 questions.

| |

Property |

| Q1 |

It felt like the virtual face was the other person. |

| Q2 |

The virtual face felt like a human face. |

| |

Agency |

| Q3 |

The movements and expressions of the virtual face felt real. |

| Q4 |

I felt that the virtual face was not a representation but the real person. |

| Q5 |

Overall, I felt like I was talking to the other person. |

| |

Credibility and confidence |

| Q1 |

The avatar has distracted me from the conversation. |

| Q2 |

I found it more difficult to maintain the conversation with the avatar than |

| |

with the real person’s face. |

| Q3 |

I felt that it was more difficult to speak with the virtual face than with

the real person. |

| Q4 |

I felt that it was more difficult for me to look at the virtual face during the conversation |

| |

than with the real person. |

| Q5 |

Overall, I felt stressed or uncomfortable talking with the virtual face. |

| Q6 |

I feel that the use of this type of avatar is an intrusion into privacy. |

| Q7 |

I feel that this kind of avatar reveals private personal information without consent. |

| |

Gender |

| Q1 |

I feel it affected my interaction with the interviewer. |

| Q2 |

It made me feel uncomfortable during the conversation. |

| Q3 |

I found it more challenging to maintain the conversation. |

| Q4 |

I feel it affected my confidence with the interviewer to answer their questions. |

| Q5 |

I feel the credibility and/or authority of the interviewer changed. |

| Q6 |

I was concerned about sharing private information while using avatars. |

References

- D. Roth and M. E. Latoschik, "Construction of the Virtual Embodiment Questionnaire (VEQ)," in IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, vol. 26, no. 12, pp. 3546-3556, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Popovici, and A. L. Popovici, “Remote Work Revolution: Current Opportunities and Challenges for Organizations,” in Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 2020.

- N. Fereydooni, and B. N. Walker, “Virtual Reality as a Remote Workspace Platform: Opportunities and Challenges," in New Future of Work 2020, August 2020.

- D. Sun et al, “”A New Mixed-Reality-Based Teleoperation System for Telepresence and Maneuverability Enhancement,” 2020, IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems. 50, 1, 55–67. [CrossRef]

- N. Ramkumar et al, “”Visual Behavior During Engagement with Tangible and Virtual Representations of Archaeological Artifacts,” 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- A.S.S. Thomsen et al, “”Operating Room Performance Improves after Proficiency-Based Virtual Reality Cataract Surgery Training, “ 2017, Ophthalmology. 124, 4, 524–531. [CrossRef]

- N.E. Seymour et al, “”Virtual Reality Training Improves Operating Room Performance Results of a Randomized,” 2002, Double-Blinded Study.

- J.J. Cummings and J.N. Bailenson,“”How Immersive Is Enough? A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Immersive Technology on User Presence,” 2016, Media Psychology. 19, 272–309. [CrossRef]

- S.A. McGlynn et al, “”Investigating AgeRelated Differences in Spatial Presence in Virtual Reality,” 2018, Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 62, 1, 1782–1786. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Souchet, D. Lourdeaux, A. Oagani, and L.Rebenitsch, “A narrative review of immersive virtual reality’s ergonomics and risks at the workplace: cybersickness, visual fatigue, muscular fatigue, acute stress, and mental overload,” in Virtual Reality 27, 19–50, 2023.

- k.M. Stanney, and P. Hash. “Locus of User-Initiated Control in Virtual Environments," in Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 7(5), 447–459, 1998.

- M. E. McCauley, and T.J. Sharkey, “Cybersickness: Perception of Self-Motion in Virtual Environments," in Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 1(3), 311–318, 1992.

- J. T. Reason, and J. J. Brand, “Motion sickness," 310, 1975.

- J. D. Moss, and E. R. Muth, “Characteristics of Head-Mounted Displays and Their Effects on Simulator Sickness," 53(3), 308–319, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Rebenitsch, and C. Owen, “Review on cybersickness in applications and visual displays," in Virtual Reality, 20(2), 101–125, 2016.

- M. M. Knight, and L. L. Arns, “The relationship among age and other factors on incidence of cybersickness in immersive environment users," in Proceedings - APGV 2006: Symposium on Applied Perception in Graphics and Visualization, 162, 2006.

- M. Slater, V. Linakis, M. Usoh, and R. Kooper, “Immersion, Presence and Performance in Virtual Environments: An Experiment with Tri-Dimensional Chess," in Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, VRST, 163–172, 1996.

- L. Aymerich-Franch, “Avatar embodiment experiences to enhance mental health," in Technology and Health, 49–66, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Porras, M. Ferrer, A. Olszewska, L. Yilmaz, C. González, M. Gracia, G. Gültekin, E. Serrano, J. Gutiérrez, “"Is This My Own Body? Changing the Perceptual and Affective Body Image Experience among College Students Using a New Virtual Reality Embodiment-Based Technique," J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 925. [CrossRef]

- J. Park, “"The effect of virtual avatar experience on body image discrepancy, body satisfaction and weightregulation intention," 2018, Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 12(1), article 3.

- O’Donnell, C. (2014). Getting Played: Gamification and the Rise of Algorithmic Surveillance. Surveillance & Society, 12(3), 349-359.

- U. Raman, “Auctus: The Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Scholarship," 2016, https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/auctus/48.

- B.A. Khan, “Emergence of technostress in multi-user VR environments for work-related purposes,” Tampere University.

- Westerman, D., Tamborini, R., & Bowman, N. D. (2015). The effects of static avatars on impression formation across different contexts on social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 111-117. [CrossRef]

- A. Javanmardi, A. Pagani, D. Stricker, “G3FA: Geometry-guided GAN for Face Animation," Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024.

- J. Brooke, “SUS: a "quick and dirty” usability scale," In B. A. In P.W.Jordan, B. Thomas and I. L. M. Weerdmeester (Eds.), in Usability Evaluation in Industry (pp. 189–194). Taylor and Francis, 1996.

- M. R. Longo, F. Schüür, M. P. M. Kammers, M. Tsakiris, and P. Haggard, “What is embodiment? A psychometric approach," in Cognition, 107(3), 978–998, 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. Nimrod, “Technostress: measuring a new threat to well-being in later life," in Aging and Mental Health, 22(8), 1080–1087, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Castilla, C. Botella, I. Miralles, J. Bretón-López, A.M. Dragomir-Davis, I. Zaragoza, and A. Garcia-Palacios, “Teaching digital literacy skills to the elderly using a social network with linear navigation: A case study in a rural area," in International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 118, 24–37, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Castilla, A. Garcia-Palacios, I. Miralles, J. Breton-Lopez, E. Parra, S. Rodriguez-Berges, and C. Botella, “Effect of Web navigation style in elderly users," in Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 909–920, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Castilla, C. Suso-Ribera, I. Zaragoza, A. Garcia-Palacios, and C. Botella, “Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study," in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol. 17, Page 5153, 17(14), 5153, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Shuai and Jiang, Liming and Liu, Ziwei and Loy, Chen Change, “VToonify: Controllable High-Resolution Portrait Video Style Transfer," ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2022, Vol. 41, Page 1-15, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).