Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Aims

2.1.1. Primary:

2.1.1. Secondary:

2.2. Study design

2.3. Ethical Consideration

2.4. Sample and Inclusion Criteria

2.5. Study Setting

2.6. Instrument

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Content Validity Index

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Comparison Between Multiple Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for nursing practice and nursing policy

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Federazione Nazionale Ordini Professioni Infermieristiche (FNOPI). Vademecum della Libera Professione Infermieristica, 2020. Available online: https://www.fnopi.it/le-politiche-professionali/libera-professione/#1572340301684-c38d9ace-6c6e (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Parlamento della Repubblica Italiana. Legge 21 aprile 2023, n. 49. Disposizioni in materia di equo compenso delle prestazioni Professionali. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ eli/id/2023/05/05/23G00051/sg (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Italy, Data. Available online: https://data.who.int/countries/380 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). Noi Italia 2024. Available online: https://noi-italia.istat.it/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Ministero della Salute Italiano. Decreto 23 maggio 2022, n. 77, Regolamento recante la definizione di modelli e standard per lo sviluppo dell'assistenza territoriale nel Servizio sanitario nazionale. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/06/22/22G00085/sg (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Ministero della Salute Italiano. Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza, PNRR Salute, Il nuovo modello di assistenza territoriale in un’ottica One Health. Available online: https://www.pnrr.salute.gov.it/portale/pnrrsalute/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- American Nurse Association (ANA). Nurse Burnout: What Is It & How to Prevent It, 2024. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/content-hub/resources/workplace/what-is-nurse-burnout-how-to-prevent-it/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on mental health at work, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053052 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Ortega-Campos, E.M.; Cañadas, G.R.; Albendín-García, L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in oncology nursing: A meta-analytic study. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Cangelosi, G.; Scuri, S.; Davidici, C.; Lavorgna, F.; Debernardi, G.; Benni, A.; Veprini, A.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Caraffa, A.; Grappasonni, I. Burnout syndrome: A preliminary study of a population of nurses in Italian prisons. Clin. Ter. 2020, 171, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pien, L.C.; Cheng, Y.; Lee, F.C.; Cheng, W.J. The effect of multiple types of workplace violence on burnout risk, sleep quality, and leaving intention among nurses. Ann. Work Expo Health 2024, 77, wxae052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Oe, M.; Ishida, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Chiba, H.; Uchimura, N. Workplace violence and its effects on burnout and secondary traumatic stress among mental healthcare nurses in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Donovan, R.; De Brún, A.; McAuliffe, E. Healthcare professionals' experience of psychological safety, voice, and silence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, L.A.; Lefton, C.; Fischer, S.A. Nurse leader burnout, satisfaction, and work-life balance. J. Nurs. Adm. 2019, 49, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwhaibi, M.; Alhawassi, T.M.; Balkhi, B.; Al Aloola, N.; Almomen, A.A.; Alhossan, A.; Alyousif, S.; Almadi, B.; Bin Essa, M.; Kamal, K.M. Burnout and depressive symptoms in healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamisa, N.; Oldenburg, B.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D. Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.B.; Lee, S.H. The nursing work environment, supervisory support, nurse characteristics, and burnout as predictors of intent to stay among hospital nurses in the Republic of Korea: A path analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, L.A.; Muñoz, L.; Weber Johnson, H.; Rodriguez, T. Exploring job satisfaction and workplace engagement in millennial nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, L.; Zhang, N.J. The hospital work environment and job satisfaction of newly licensed registered nurses. Nurs. Econ. 2014, 32, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Gascón, T.; Martín-Fernández, J.; Gálvez-Herrer, M.; Tapias-Merino, E.; Beamud-Lagos, M.; Mingote-Adán, J.C.; Grupo EDESPROAP-Madrid. Effectiveness of an intervention for prevention and treatment of burnout in primary health care professionals. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, A.C.; Warshawsky, N.; Talbert, S. Factors that influence millennial generation nurses' intention to stay: An integrated literature review. J. Nurs. Adm. 2021, 51, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, R.T.; Bamgbade, S.; Bourdeanu, L. Nursing leadership roles and its influence on the millennial psychiatric nurses' job satisfaction and intent to leave. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2023, 29, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber, B.; Barriball, K.L. Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: A review of the research literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maqbali, M.A. Factors that influence nurses' job satisfaction: A literature review. Nurs. Manag. (Harrow) 2015, 22, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, N.; Seki, M.; Nakai, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Nagao, K.; Morimitsu, R. Depressive symptoms, burnout, resilience, and psychosocial support in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide study in Japan. PCN Rep. 2023, 2, e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raei, M.; Shahrbaf, M.A.; Salaree, M.M.; Yaghoubi, M.; Parandeh, A. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey in teaching hospitals. Work 2024, 77, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuri, S.; Tesauro, M.; Petrelli, F.; Argento, N.; Damasco, G.; Cangelosi, G.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Savva, D.; Grappasonni, I. Use of an online platform to evaluate the impact of social distancing measures on psycho-physical well-being in the COVID-19 era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülşen, M.; Ertuğrul, B.; Taşkın, G.; Aytar, A.; Genç, Y.K. The relationship between burnout and work engagement levels of nurses and physiotherapists working during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Work 2024, 77, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetto, Y.; Farr-Wharton, R. A Case Study Examining the Impact of Public-Sector Nurses' Perception of Workplace Autonomy on Their Job Satisfaction: Lessons for Management. Int. J. Manag. Organ. Behav. 2004, 8(5), 521–539. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska-Lipień, I.; Gabryś, T.; Kózka, M.; Gniadek, A.; Brzostek, T. Nurses' Intention to Leave Their Jobs in Relation to Work Environment Factors in Polish Hospitals: Cross-Sectional Study. Med. Pr. 2023, 74(5), 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacour, F.; Estrate, M. Au-delà du soin, une collaboration des infirmiers libéraux en réseau de santé [Beyond Care, the Collaboration of Freelance Nurses in a Healthcare Network]. Soins 2013, (775), 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, C.K.D.R.; Guirardello, E.B. Nurse Work Environment and Its Impact on Reasons for Missed Care, Safety Climate, and Job Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77(5), 2398–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlamento della Repubblica Italiana. Legge 43 del 1 Febbraio 2006, Disposizioni in Materia di Professioni Sanitarie Infermieristiche, Ostetrica, Riabilitative, Tecnico-Sanitarie e della Prevenzione e Delega al Governo per l'Istituzione dei Relativi Ordini Professionali. Gazzetta Ufficiale, 17 February 2006. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2006/02/17/006G0050/sg (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Parlamento della Repubblica Italiana. Legge 3 del 11 Gennaio 2018, Delega al Governo in Materia di Sperimentazione Clinica di Medicinali Nonché Disposizioni per il Riordino delle Professioni Sanitarie e per la Dirigenza Sanitaria del Ministero della Salute. Gazzetta Ufficiale, 31 January 2018. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/1/31/18G00019/sg (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Italiano. Decreto Legislativo 502 del 30 Dicembre del 1992, Riordino della Disciplina in Materia Sanitaria, a Norma dell'Articolo 1 della Legge 23 Ottobre 1992, N. 421. Gazzetta Ufficiale, 7 January 1994. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1994/01/07/094A0049/sg (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Italiano. Misure Urgenti a Sostegno delle Famiglie e delle Imprese per l'Acquisto di Energia Elettrica e Gas Naturale, Nonché in Materia di Salute e Adempimenti Fiscali. Gazzetta Ufficiale, 30 March 2023. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2023/03/30/23G00042/sg (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Federazione Nazionale Ordini Professioni Infermieristiche (FNOPI). Infermieri per Voi. Available online: https://infermieripervoi.it/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Skrivankova, V.W.; Richmond, R.C.; Woolf, B.A.R.; Yarmolinsky, J.; Davies, N.M.; Swanson, S.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Timpson, N.J.; Dimou, N.; Langenberg, C.; Golub, R.M.; Loder, E.W.; Gallo, V.; Tybjaerg-Hansen, A.; Davey Smith, G.; Egger, M.; Richards, J.B. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization: The STROBE-MR Statement. JAMA 2021, 326(16), 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, B.A. Development of an Instrument to Measure Quality of Nurses' Worklife. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, University of Illinois at Chicago, Health Sciences Center. 2001. 3008064.

- Garzaro, G.; Clari, M.; Donato, F.; Dimonte, V.; Mucci, N.; Easton, S.; Van Laar, D.; Gatti, P.; Pira, E. A Contribution to the Validation of the Italian Version of the Work-Related Quality of Life Scale. Med. Lav. 2020, 111(1), 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. MBI: Maslach Burnout Inventory; Manual; University of California: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Sirigatti, S.; Stefanile, C. Adattamento e Taratura per l’Italia. In Maslach, C.; Jackson, S., Eds.; MBI Maslach Burnout Inventory; Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 1993, 33–42.

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. Technique for the Measure of Attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 140. [Google Scholar]

- The jamovi project. Jamovi Version 2.3, 2002. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Steven, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, B.I.; Brown Mahoney, C.; Xu, Y. Impact of Job Demands and Resources on Nurses' Burnout and Occupational Turnover Intention Towards an Age-Moderated Mediation Model for the JD-R Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16(11), 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the Burnout Experience: Recent Research and Its Implications for Psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, N.A.; Hammond, G.D. A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Construct Validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73(1), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albolino, S.; Tartaglia, R.; Bellandi, T.; Amicosante, A.M.; Bianchini, E.; Biggeri, A. Patient Safety and Incident Reporting: Survey of Italian Healthcare Workers. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2010, 19 (Suppl 3), i8–i12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P.; Senabe, S.; Naicker, N.; Kgalamono, S.; Yassi, A.; Spiegel, J.M. Workplace-Based Organizational Interventions Promoting Mental Health and Happiness Among Healthcare Workers: A Realist Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16(22), 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aust, B.; Leduc, C.; Cresswell-Smith, J.; O'Brien, C.; Rugulies, R.; Leduc, M.; Dhalaigh, D.N.; Dushaj, A.; Fanaj, N.; Guinart, D.; Maxwell, M.; Reich, H.; Ross, V.; Sadath, A.; Schnitzspahn, K.; Tóth, M.D.; van Audenhove, C.; van Weeghel, J.; Wahlbeck, K.; Arensman, E.; Greiner, B.A.; MENTUPP Consortium Members. The Effects of Different Types of Organizational Workplace Mental Health Interventions on Mental Health and Wellbeing in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2024, 97(5), 485–522. [CrossRef]

- Smets, T.; Pivodic, L.; Piers, R.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Engels, Y.; Szczerbińska, K.; Kylänen, M.; Gambassi, G.; Payne, S.; Deliens, L.; Van den Block, L. The Palliative Care Knowledge of Nursing Home Staff: The EU FP7 PACE Cross-Sectional Survey in 322 Nursing Homes in Six European Countries. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27(1), 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Italiano. Decreto Ministeriale 71, Modelli e Standard per lo Sviluppo dell'Assistenza Territoriale nel Servizio Sanitario Nazionale. Gazzetta Ufficiale, 3 May 2022. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/05/03/22A02656/sg (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Labrague, L.J.; McEnroe-Petitte, D.M.; Leocadio, M.C.; Van Bogaert, P.; Cummings, G.G. Stress and Ways of Coping Among Nurse Managers: An Integrative Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27(7–8), 1346–1359. [CrossRef]

- Niskala, J.; Kanste, O.; Tomietto, M.; Miettunen, J.; Tuomikoski, A.M.; Kyngäs, H.; Mikkonen, K. Interventions to Improve Nurses' Job Satisfaction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76(7), 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasin, Y.M.; Kerr, M.S.; Wong, C.A.; Bélanger, C.H. Factors Affecting Nurses' Job Satisfaction in Rural and Urban Acute Care Settings: A PRISMA Systematic Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsen, K.A.; de Blok, J. Buurtzorg: Nurse-Led Community Care. Creat. Nurs. 2013, 19, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumillo-Gutiérrez, I.; Salto, G.E. Buurtzorg Nederland, a Proposal for Nurse-Led Home Care. Enferm. Clin. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 31, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegedüs, A.; Schürch, A.; Bischofberger, I. Implementing Buurtzorg-Derived Models in the Home Care Setting: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2022, 4, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Hou, T.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y.; Ni, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Deng, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Jia, Y.; Dong, W.; Qian, X. Status and Influencing Factors of Nurses' Burnout: A Cross-Sectional Study During COVID-19 Regular Prevention and Control in Jiangsu Province, China. Glob. Ment. Health (Camb.) 2024, 11, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Deng, W.; Li, Z.; Hou, T.; Dong, W. Impact of Insomnia on Burnout Among Chinese Nurses Under the Regular COVID-19 Epidemic Prevention and Control: Parallel Mediating Effects of Anxiety and Depression. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1605688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sihvola, S.; Nurmeksela, A.; Mikkonen, S.; Peltokoski, J.; Kvist, T. Resilience, Job Satisfaction, Intentions to Leave Nursing and Quality of Care Among Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Questionnaire Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, A.M.; Al-Hniti, M.; Bani Salameh, A.; Alkaid-Albqoor, M.; Ahmad, M. Predictors of Job Satisfaction of Registered Nurses Providing Care for Older Adults. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiessen, N.J.; Leslie, K.; Stephens, J.M.L. An Examination of Self-Employed Nursing Regulation in Three Canadian Provinces. Policy Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2023, 24, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sguanci, M.; Mancin, S.; Gazzelloni, A.; Diamanti, O.; Ferrara, G.; Morales Palomares, S.; Parozzi, M.; Petrelli, F.; Cangelosi, G. The Internet of Things in the Nutritional Management of Patients with Chronic Neurological Cognitive Impairment: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Mancin, S.; Pantanetti, P.; Nguyen, C.C.T.; Morales Palomares, S.; Biondini, F.; Sguanci, M.; Petrelli, F. Lifestyle Medicine Case Manager Nurses for Type Two Diabetes Patients: An Overview of a Job Description Framework—A Narrative Review. Diabetology 2024, 5, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.; Golzio, L.E.; Bianchi, G. The Evolution of Health-, Safety- and Environment-Related Competencies in Italy: From HSE Technicians to HSE Professionals and, Eventually, to HSE Managers. Safety Sci. 2019, 118, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Mancin, S.; Morales Palomares, S.; Pantanetti, P.; Quinzi, E.; Debernardi, G.; Petrelli, F. Impact of School Nurse on Managing Pediatric Type 1 Diabetes with Technological Devices Support: A Systematic Review. Diseases 2024, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | N | Median | Mode | IQR | Setting | Emplyee | N | Median | Mode | IQR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of service | F | 165 | 15 | 15 | 14.0 | Years of service | Domiciliary | Freelance | 26 | 9 | 10 | 10.25 | |

| M | 35 | 15 | 6 | 19.0 | Private | 8 | 14 | 1 | 16 | ||||

| Age | F | 165 | 40 | 39 | 15.0 | Public | 8 | 16 | 30 | 20.5 | |||

| M | 35 | 39 | 33 | 19.5 | Hospital | Freelance | 8 | 8.5 | 5 | 9 | |||

| Employee | N | Median | Mode | IQR | Private | 26 | 16 | 5 | 17.5 | ||||

| Years of service | Freelance | 46 | 7.5 | 6 | 10.8 | Public | 64 | 17 | 15 | 13 | |||

| Private | 46 | 15.5 | 5 | 19.8 | Territorial | Freelance | 12 | 5.5 | 2 | 13.25 | |||

| Public | 108 | 16 | 15 | 13.0 | Private | 12 | 17.5 | 12 | 20.5 | ||||

| Age | Freelance | 46 | 30.5 | 25 | 10.8 | Public | 36 | 14.50 | 12 | 7.25 | |||

| Private | 46 | 39 | 33 | 16.5 | Age | Domiciliary | Freelance | 26 | 32 | 25 | 12.25 | ||

| Public | 108 | 42 | 39 | 13.5 | Private | 8 | 38.5 | 46 | 15.75 | ||||

| Setting | N | Median | Mode | IQR | Public | 8 | 44 | 41 | 11.75 | ||||

| Years of service | Domiciliary | 42 | 10 | 10 | 10.8 | Hospital | Freelance | 8 | 31.50 | 26 | 10.75 | ||

| Hospital | 98 | 16.5 | 15 | 15.8 | Private | 26 | 40.5 | 33 | 17.75 | ||||

| Territorial | 60 | 14 | 12 | 11.3 | Public | 64 | 45.5 | 50 | 12.5 | ||||

| Age | Domiciliary | 42 | 35.5 | 26 | 13.5 | Territorial | Freelance | 12 | 29 | 25 | 6.75 | ||

| Hospital | 98 | 44 | 33 | 16.0 | Private | 12 | 41 | 39 | 15.5 | ||||

| Territorial | 60 | 39 | 39 | 12.3 | Public | 36 | 39 | 39 | 9.25 |

| Factor | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Uniqueness | |||||||

| Item 1 | 0.118 | 0.105 | 0.9783 | 0.128 | 0.00149 | ||||||

| Item 2 | 0.207 | 0.249 | 0.4623 | 0.129 | 0.66506 | ||||||

| Item 3 | 0.198 | 0.190 | -0.0889 | 0.347 | 0.79668 | ||||||

| Item 4 | 0.197 | 0.108 | 0.2147 | 0.723 | 0.38014 | ||||||

| Item 5 | 0.754 | 0.123 | 0.1207 | 0.232 | 0.34848 | ||||||

| Item 6 | 0.216 | 0.227 | 0.2763 | 0.484 | 0.59171 | ||||||

| Item 7 | 0.851 | 0.192 | 0.1824 | 0.216 | 0.15890 | ||||||

| Item 8 | 0.129 | 0.845 | 0.1661 | 0.234 | 0.18625 | ||||||

| Item 9 | 0.223 | 0.793 | 0.1873 | 0.179 | 0.25491 | ||||||

| Item 10 | 0.330 | 0.139 | 0.1437 | 0.259 | 0.78431 | ||||||

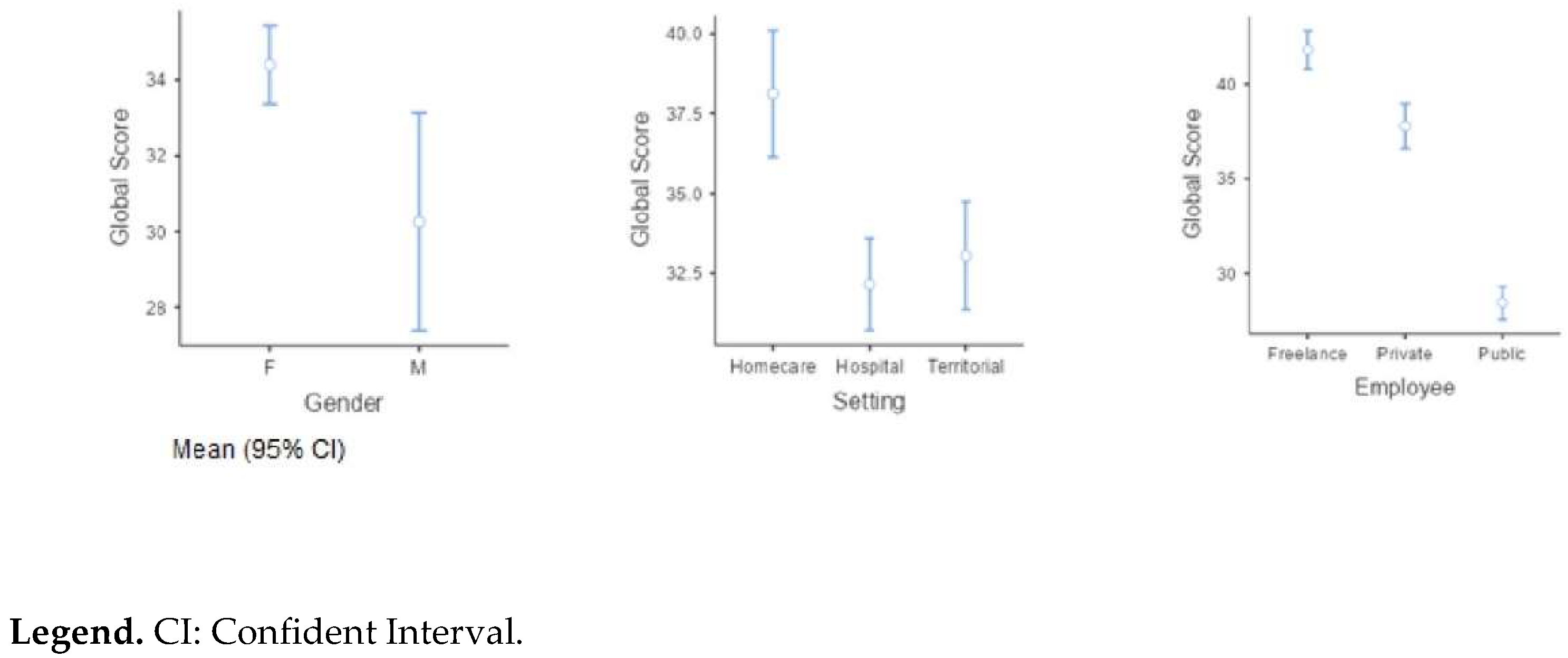

| Global Score | Gender | N | Mean | Median | Mode | SD | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 165 | 34.4 | 35 | 29 | 6.68 | 11.0 | |

| M | 35 | 30.3 | 28 | 29 | 8.35 | 14.5 | |

| Global Score | Employee | N | Mean | Median | Mode | SD | IQR |

| Freelance | 46 | 41.8 | 42 | 43 | 3.43 | 4.00 | |

| Private | 46 | 37.8 | 38 | 37 | 4.03 | 4.75 | |

| Public | 108 | 25.5 | 29 | 29 | 4.52 | 5.00 | |

| Global Score | Setting | N | Mean | Median | Mode | SD | IQR |

| Home care | 42 | 38.1 | 40 | 42 | 6.35 | 7.75 | |

| Hospital | 98 | 32.2 | 32 | 26 | 7.14 | 11.00 | |

| Territorial | 60 | 33.0 | 32 | 29 | 6.54 | 8.00 |

| Dependent Variable | Grouping Variable | Normality Test | Normality p | F | df1 | df2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Score | Gender | KS test | 0.106 | 7.58 | 1 | 43.7 | 0.009 |

| Employee | KS test | 0.166 | 213 | 2 | 102 | <.001 | |

| Setting | KS test | 0.372 | 12.6 | 2 | 106 | <.001 |

| POST HOC TEST (Games-Howell): Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | |||

| F | Mean Difference | - | 4.14 | |

| p-value | - | 0.009 | ||

| M | Mean Difference | - | ||

| p-value | - | |||

| POST HOC TEST (Games-Howell): Employee | ||||

| Freelance | Private | Public | ||

| Freelance | Mean Difference | - | 4.02 | 13.34 |

| p-value | - | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Private | Mean Difference | - | 9.32 | |

| p-value | - | <.001 | ||

| Public | Mean Difference | - | ||

| p-value | - | |||

| POST HOC TEST (Games-Howell): Setting | ||||

| Homecare | Hospital | Territorial | ||

| Homecare | Mean Difference | - | 5.97 | 5.07 |

| p-value | - | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Hospital | Mean Difference | - | -0.897 | |

| p-value | - | 0.699 | ||

| Territorial | Mean Difference | - | ||

| p-value | - | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).