Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Side-Channel Attacks (SCAs): SCAs exploit unintended data leakage to infer critical information like cryptographic keys. Countermeasures such as masking, noise injection, and algorithmic optimizations aim to obscure exploitable patterns, but balancing security with performance remains challenging [9,10].

- IC Cloning and Counterfeiting: Cloning techniques replicate secure devices, undermining anti-counterfeiting measures. This is especially concerning resource-constrained IoT devices, where robust defenses are difficult to implement [11].

- Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs): PUFs leverage intrinsic manufacturing variations to generate unique identifiers for authentication and cryptographic key generation. Recent innovations, such as dynamic and hybrid PUF architectures, enhance security and reliability under varying environmental conditions [12,13].

- Quantum-Resilient Architectures: Preparing hardware for quantum-era threats [22].

2. Methodology and Implementation

2.1. Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs)

2.1.1. Overview and Applications:

- 1. Authentication: PUFs enable secure device-specific authentication without requiring external key storage, minimizing risks of key theft or tampering [18].

- Key Generation: By deriving cryptographic keys directly from PUF responses, systems achieve high entropy and uniqueness, reducing dependency on stored secrets. [21]

- Anti-Counterfeiting: Embedded PUFs safeguard hardware components from cloning and unauthorized replication, enhancing supply chain integrity and intellectual property protection [31].

- Secure Communication: PUFs facilitate one-time session key generation, ensuring data confidentiality and integrity during transmission [22].

2.2. Key Architectures

- SRAM PUFs:

- 2.

- Arbiter and XOR PUFs

- 3.

- Memristor-Based PUFs

2.3. Security Protocols

- Dynamic Transformations: Challenges are modified dynamically, enhancing response unpredictability and security.

- Mutual Authentication: Both communicating parties verify each other’s authenticity, ensuring a secure exchange.

- Cryptography-Free Design: APP achieves robust security without computationally intensive cryptographic primitives, making it ideal for IoT and edge devices [16]

- Error Tolerance: Mechanisms address natural variations in PUF responses, ensuring reliability under diverse conditions [17]

2.4. Hardware Trojans

- Insertion Phase

- Design Phase: Trojans at this stage involve altering the circuit layout or introducing malicious logic within the design files [30].

- Fabrication Phase: Foundries may introduce unauthorized modifications, exploiting the globalization of semiconductor manufacturing [17].

- Post-Manufacturing Phase: Trojans can also be added during testing, assembly, or deployment.

- 2.

- Trigger Mechanism

- Internal Triggers: Activation is based on specific internal conditions, such as reaching a counter value or particular logic states.

- External Triggers: Activation occurs through external stimuli like specific input patterns or environmental factors, ensuring stealthy behavior until the attack is launched [37].

- 3.

- Payload

- HT payloads determine their impact, which can include:

- Data Exfiltration: Leakage of cryptographic keys or sensitive information during secure communication.

- Functional Disruption: Degrading device performance or causing denial-of-service (DoS) attacks.

- Subtle Malfunctions: Gradual deterioration of operational reliability to avoid immediate detection [35].

2.5. Detection Methodologies

- Reverse Engineering: Analyzing IC layouts to identify unauthorized modifications or structural anomalies [20].

- 2.

- Side-Channel Analysis: Monitors power consumption, timing variations, or electromagnetic emissions to detect anomalies [32].

2.6. Emerging Techniques

- Machine Learning-Based Detection: Utilizes supervised and unsupervised learning models to analyze side-channel data and detect Trojan-induced anomalies [28].

- 2.

- PUF-Integrated Detection: Embeds PUFs into hardware to monitor real-time behavior. PUFs generate unique device identifiers and act as integrity checks, enhancing Trojan detection [6].

2.7. Countermeasure

2.8. Side-Channel Attacks (SCAs)

- o

- Simple Power Analysis (SPA): Observes direct power usage patterns.

- o

- Differential Power Analysis (DPA): Uses statistical methods to identify correlations with cryptographic keys [35].

- Applications: Widely used against embedded devices and smart cards.

- Masking: Introduces random noise into intermediate cryptographic computations, ensuring that leaked side-channel information is uncorrelated with actual data. [18]

- 2.

- Blinding: Adds random values to sensitive computations, hiding real data from side-channel analysis. [21]

- Randomized Caches: Obfuscate memory access patterns by randomizing cache lines or introducing unpredictable delays, mitigating timing-based SCAs [22]

- Power Management Techniques: Implement dynamic voltage scaling or dummy operations to smooth power consumption patterns, masking variations attackers rely on [35].

- Electromagnetic Shielding: Incorporate shielding layers into ICs to minimize or render electromagnetic emissions meaningless [28].

- Combine cryptographic techniques with hardware defenses for comprehensive protection. Employing masking alongside randomized hardware mechanisms ensures redundancy in security [20].

- Dynamic voltage scaling coupled with algorithmic blinding disrupts both timing and power-based SCAs.

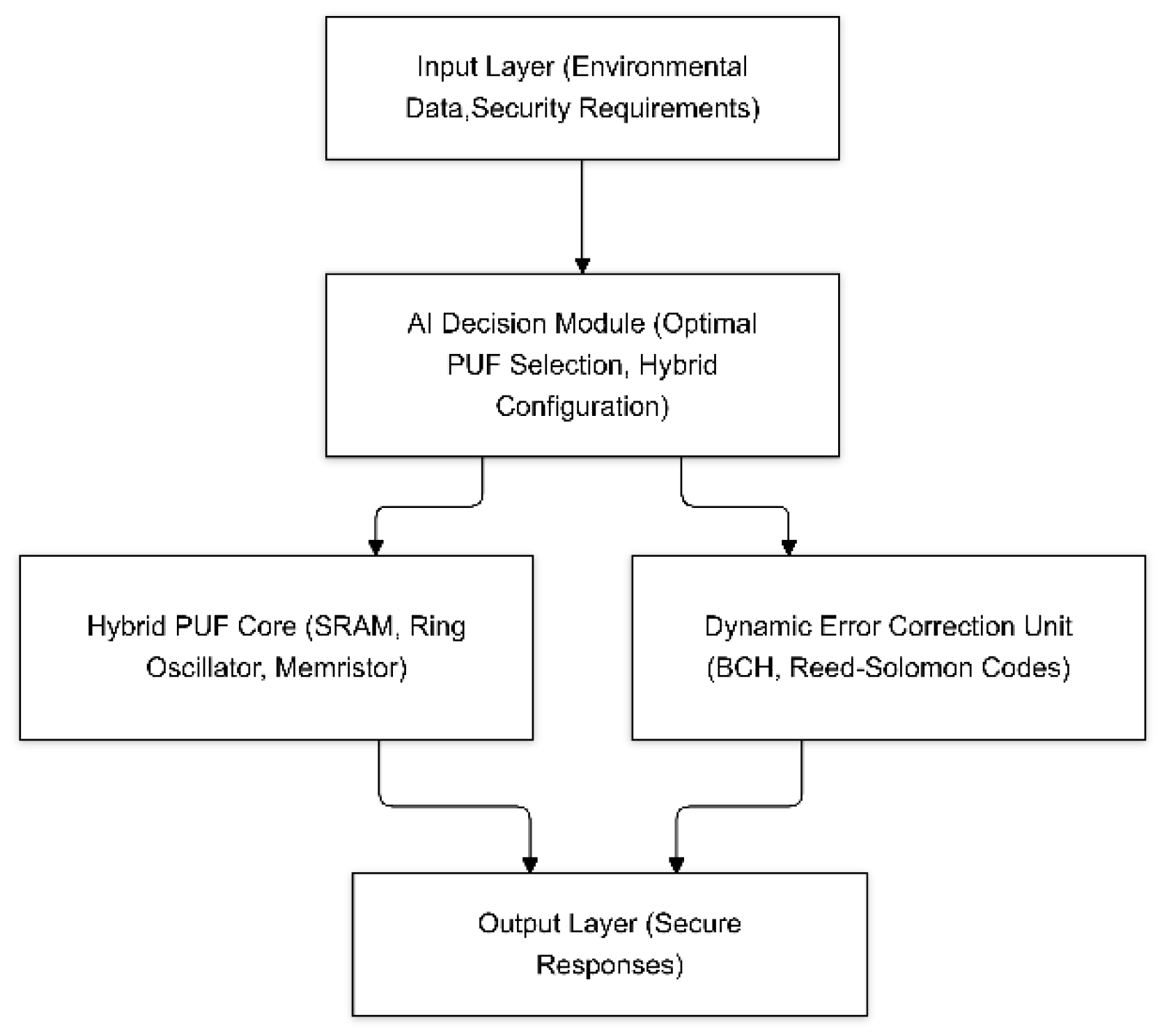

3. Proposed AI model

3.1. Model Architecture

-

Hybrid PUF Core: Combines different PUF types for enhanced versatility.

- o

- SRAM PUF ensures ease integration.

- o

- Ring Oscillator PUF provides environmental robustness.

- o

- Memristor PUF offers high entropy and energy efficiency.

- AI Decision Module: Analyzes real-time environmental data to select or configure the optimal PUF type.

- Dynamic Error Correction Unit (DECU): Employs AI-enhanced error correction, ensuring stable responses under diverse conditions.

3.2. Flow of Operation

- Input Processing: Collect environmental data and operational parameters.

- PUF Selection: AI module selects the optimal PUF type or hybrid configuration.

- Challenge Processing: Generate raw responses via selected PUF(s).

- Error Correction: DECU ensures response consistency.

- Response Generation: Final output used for authentication or cryptographic tasks.

3.3. Model Diagram

- The architecture of the hybrid AI-driven PUF model is illustrated in the diagram below:

3.4. Future Prospects

- Quantum-Resilient Integration: Incorporate post-quantum cryptography.

- Blockchain Applications: Use as a root of trust for decentralized systems.

- Edge Scalability: Design ultra-low-power AI modules for energy-harvesting devices.

4. Future Directions

4.1. Enhancing Resilience:

- ▪

- Dynamic PUF Transformations: Developing complex, adaptive transformation mechanisms for PUFs can combat advanced modeling and side-channel attacks. These transformations dynamically alter challenge-response relationships, making it exceedingly difficult for attackers to predict or model behavior [18].

- ▪

- Quantum-Resilient Architectures: As quantum computing becomes a tangible threat to cryptographic systems, integrating quantum-safe algorithms with hardware security mechanisms is critical. Hybrid designs combining PUFs with lattice-based cryptography ensure long-term resilience [22].

- ▪

- Integrated Tamper Detection: Embedding active monitoring systems within ICs to detect and respond to physical tampering in real-time enhances security. Such systems could utilize behavioral analysis or physical integrity checks to flag anomalies immediately [37].

- ▪

- AI-Driven Detection Mechanisms: Incorporating AI for dynamic threat detection enables systems to adapt to evolving attack strategies. AI-based models can analyze side-channel data in real-time to identify complex patterns indicative of malicious activities. [30]

4.2. Expanding Applications

5. Conclusions

References

- Hu, T.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Y.; Yang, Y. Hardware Trojan detection combine with machine learning: An SVM-based detection approach. 2019 IEEE 13th International Conference on Anti-Counterfeiting, Security, and Identification (ASID), 2019; 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamitkar, R.; Dube, R. R. A survey on using machine learning to counter hardware Trojan challenges. In ICT with Intelligent Applications: Proceedings of ICTIS 2021, Volume 1. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, J.; Gavas, E.; Jimenez, J.; Padman, V.; Karri, R. Towards a comprehensive and systematic classification of hardware Trojans. Proceedings of 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, 2010; 1871–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranipoor, M.; Koushanfar, F. A survey of hardware Trojan taxonomy and detection. IEEE Design & Test of Computers 2010, 27, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghilan, A.; Ponnambalam, M.; Chellamani, G. K. Hardware Trojan design and analysis in FPGA: An introductory exploration. 2024 International Conference on Signal Processing, Computation, Electronics, Power and Telecommunication (IConSCEPT), 2024; 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Lin, B.; Pang, Y.; Xu, F.; Lu, Y.; Chiu, Y. C.; Wu, H. Concealable physically unclonable function chip with a memristor array. Science Advances 2022, 8, eabn7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortez, M.; Dargar, A.; Hamdioui, S.; Schrijen, G. J. Modeling SRAM start-up behavior for physical unclonable functions. 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Defect and Fault Tolerance in VLSI and Nanotechnology Systems (DFT), 2012; 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfmeier, C.; Boit, C.; Nedospasov, D.; Seifert, J. P. Cloning physically unclonable functions. 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Hardware-Oriented Security and Trust (HOST), 2013; 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dofe, J.; Rajput, S. Protecting against modeling attacks: Design and analysis of lightweight dynamic physical unclonable function. Cluster Computing 2025, 28, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.; Idriss, H.; Idriss, T.; Bayoumi, M. Lightweight PUF protocols. In Lightweight Hardware Security and Physically Unclonable Functions: Improving Security of Constrained IoT Devices; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Sahay, S. K. Modern hardware security: A review of attacks and countermeasures. arXiv preprint 0 arXiv:2501.04394, 2025. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2501, 4394.

- Bauer, L.; Nassar, H.; Khan, N.; Becker, J.; Henkel, J. Machine-learning-based side-channel attack detection for FPGA SoCs. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Artificial Intelligence 2024, 1, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Johnson, R.; Smith, A. A taxonomy of side-channels. Proceedings of SoutheastCon 2024. IEEE, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Potestad-Ordóñez, F. E.; Morales, A. D.; Rodríguez, J.; Garcia, L. Design and evaluation of countermeasures against fault injection attacks and power side-channel leakage. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 65548–65549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Zeng, Q. Survey of CPU cache-based side-channel attacks: Systematic analysis, security models, and countermeasures. Security and Communication Networks 2021, 5559552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Suh, G. E. Remote power side-channel attacks on FPGAs. IEEE Design & Test, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuet, L.; Gogniat, G.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Design of PUF-based secure systems. IEEE Design & Test 2015, 32, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, L.; Wu, Y. Dynamic PUF architectures for IoT. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing 2021, 9, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shin, J. Advanced PUF protocols for secure communications. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2020, 15, 2023–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasser, F.; El Mahjoub, K. B.; Sadeghi, A. R.; Wachsmann, C. Advances in IoT security. IEEE Security & Privacy 2016, 14, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, R. Physically Unclonable Functions: Constructions, Properties, and Applications; Springer, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Käsper, E. Cryptography on constrained devices. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2015, 10, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabeel, M.; Khan, S. Memristor-based PUFs: A survey of advancements and challenges. Journal of Hardware Security 2021, 3, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, G.; Bernard, C.; Regazzoni, F. Lightweight cryptographic implementations with energy-efficient PUFs. IEEE Design & Test 2019, 36, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheesh, S.; Udaya, K. Emerging PUF technologies: A review. Microelectronics Journal 2019, 88, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tria, M.; Mahjoub, K. B. E.; Bossuet, L. Evaluation of error-tolerant PUFs. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2019, 66, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, C. Lightweight cryptography with PUF integration. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 178473–178485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwoliński, M.; Shah, S. Exploring the security of Arbiter-based PUFs. Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems–CHES, 2018; 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Rahman, M. T.; Basu, A. Hardware Trojan detection: A comprehensive review. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2017, 36, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.; Nandi, S. Comparative analysis of hardware Trojan defense mechanisms. Journal of Hardware Security 2020, 4, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, W. A survey of hardware security techniques. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2019, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Comprehensive survey on power-based side-channel attacks. ACM Computing Surveys 2015, 48, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Lu, Q. Hybrid approaches for hardware Trojan detection. Journal of Cryptographic Engineering 2020, 10, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, M.; Kalra, J. Lightweight security mechanisms for IoT and edge devices. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 1895–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L. Energy-efficient countermeasures for side-channel attacks. Journal of Hardware Security 2021, 5, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, W. A survey of hardware security techniques. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2019, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwoliński, M.; Wang, J. Advanced detection mechanisms for hardware Trojans. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing 2020, 8, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).