Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

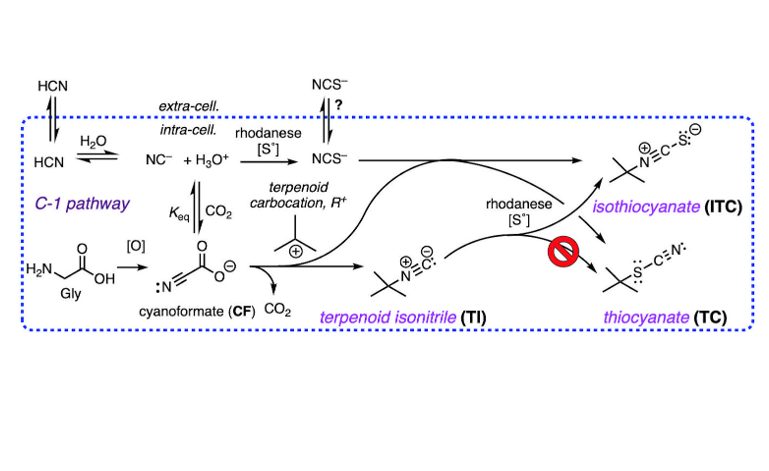

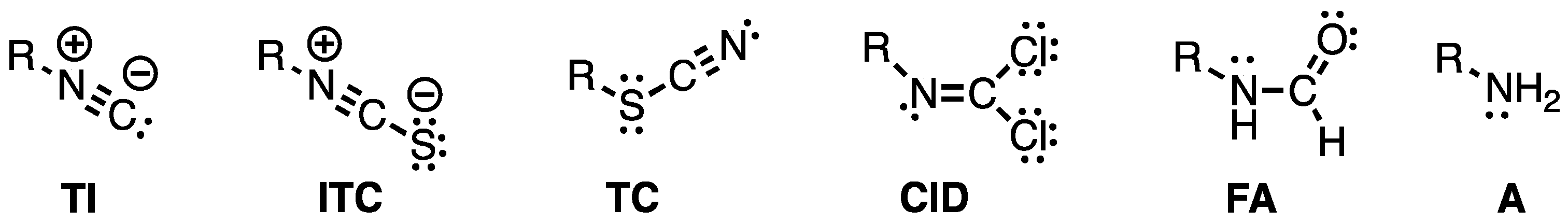

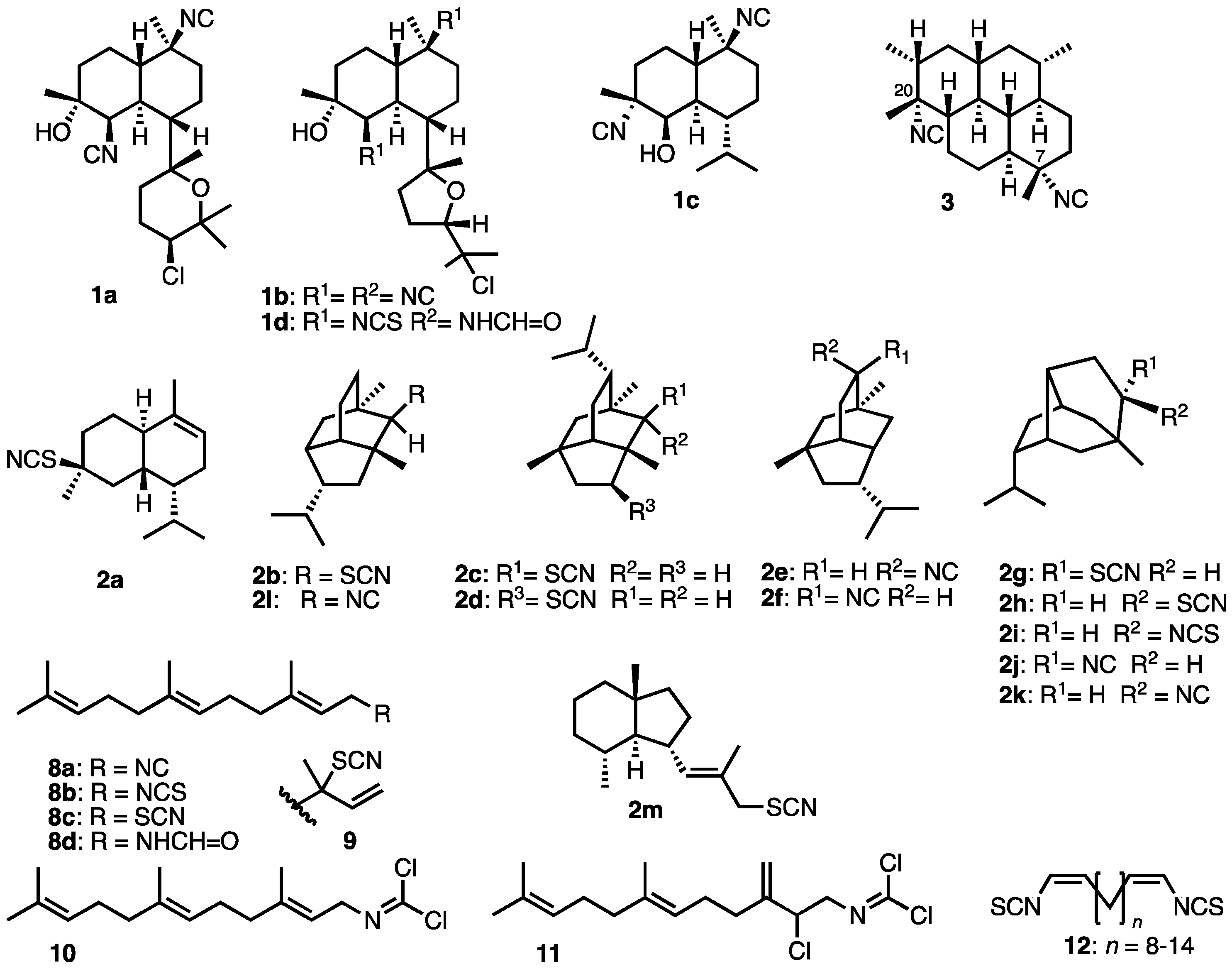

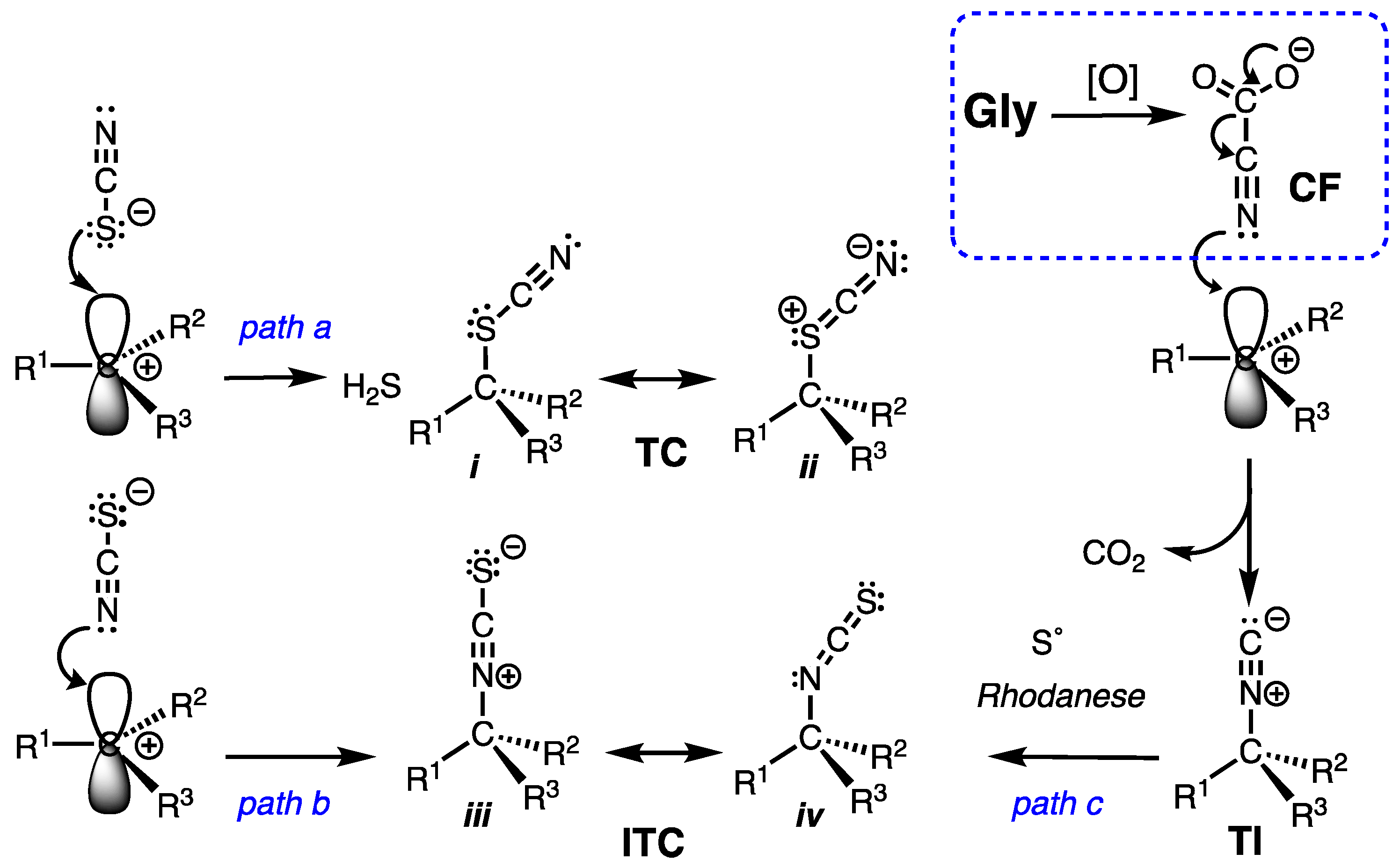

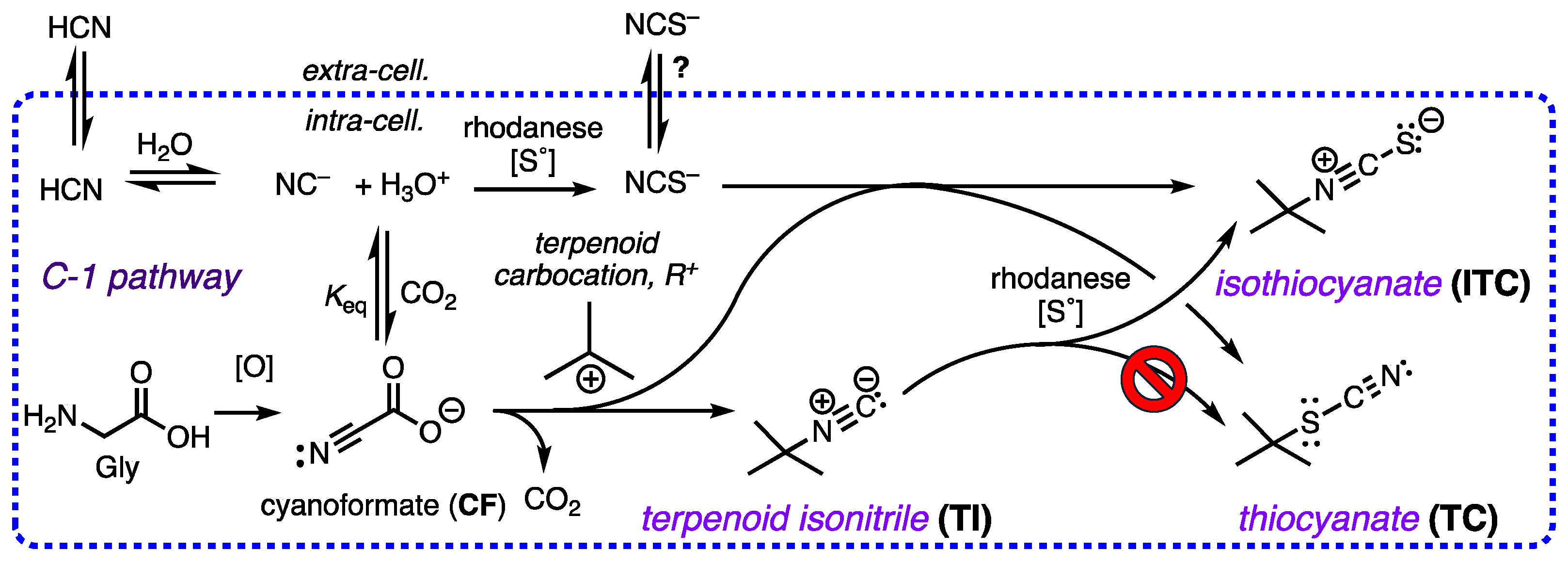

The co-occurrence of rare terpenoid thiocyanates (R-C-SCN), structurally similar to their more common isothiocyanate isomers (R-NCS) remained an enigma that can now be rationalized by consideration of three integrated biosynthetic motifs: terpenoid carbocation capture by cyanoformate, NC-COOH (itself in equilibrium with NC– and CO2), a co-localized rhodanese (a dual-function enzyme that can both convert inorganic NC– to thiocyanate ion, NCS–, and alkyl isonitriles to alkyl isothiocyanate (R-NC –> R–NCS). This scenario explains the preponderance of isothiocyanates, R-NCS as products of a linear reaction path – a-addition of S0 to R-NC – over the minor, less stable thiocyanates, R-SCN, as products of adventitious capture of liberated NCS– by the penultimate terpenoid carbocation precursor. DFT calculations support the proposal and eliminate other possibilities, e.g. isomerization of R-NCS to R-SCN.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion.

2.1. Chemistry and Bonding in TC and ITC.

2.2. Dissociation-Reassociation.

2.3. Precedence Strengthens the Role of Adventitious NCS–

2.4. Thiocyanate is a competent ambident nucleophile.

2.5. A Simple Proposal – Thiocyanates Arise Adventitiously.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emsermann, J.; Kauhl, U.; Opatz, T. Marine Isonitriles and Their Related Compounds. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 16–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garson, M.J.; Simpson, J.S. Marine isocyanides and related natural products – structure, biosynthesis and ecology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chena, T-Y.; Chen, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Guo, Y.; Chang, W-C. Current Understanding Toward Isonitrile Group Biosynthesis and Mechanism. Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J. T.; Wells, R. J.; Oberhänsli, W. E.; Hawes, G. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 4010–4012. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.J.; Patra, A.; Roll, D.M.; Scheuer, P.J.; Matsumoto, G.K.; Clardy, J. Kalihinol-A, a highly functionalized diisocyano diterpenoid antibiotic from a sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4644–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. J.; Patra, A.; Roll, D. M.; Scheuer, P. J.; Matsumoto, G. K.; Clardy, J. Kalihinols, multifunctional diterpenoid antibiotics from marine sponges Acanthella sp. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4644–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, Z.; Abel, S.; Hollin, T.; Barnes, G.L.; Chung, J.H.; Daub, M.E.; Renard, I.; Choi, J.Y.; Vydyam, P.; Pal, A.; Alba-Argomaniz, M.; Banks, C.A.S.; Kirkwood, J.; Saraf, A.; Camino, I.; Castenada, P.; Cuevas, J.C.; De Mercado-Arnanz, J.; Fernandez-Alvaro, E.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Ibarz, N.; Viera-Morilla, S.; Prudhomme, J.; Joyner, C.J.; Bei, A.K.; Florens, L.; Ben-Mamoun, C.; Vanderwal, C.D.; Le Roch, K.G. A kalihinol analog disrupts apicoplast function and vesicular trafficking in P. falciparum malaria. Science 2024, 385, 7966–7978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafieri, F.; Fattorusso, E.; Magno, S.; Santacroce, C.; Sica, D. Isolation and Structure of Axisonitrile-1 and Axisothiocyanate-1. Two Unusual Sesquiterpenoids from the Marine Sponge Axinella cannabina. Tetrahedron 1973, 29, 4259–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinski, T.F. The Paradox of Antimalarial Terpenoid Isonitrile Biosynthesis Explained. Proposal of Cyanoformate as an NC Delivery Vector. J. Nat. Prod. 2024, 87, ASAP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wratten, S.J.; Faulkner, D.J. Carbonimidic dichlorides from the marine sponge Pseudaxinyssa pitys. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 7367–7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brust, A.; Garson, M.J. Dereplication of complex natural product mixtures by 2D NMR: Isolation of a new carbonimidic dichloride of biosynthetic interest from the tropical marine sponge Stylotella aurantium. ACGC Chem. Res. Commun. 2004, 17, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hagadone, M.R.; Burreson, B.J.; Scheuer, P.J.; Finer, J.S.; Clardy, J. Defense Allomones of the Nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa Lamarck 1801. Helv. Chim. Acta 1979, 62, 2484–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, A.H.; Molinski, T.F.; Fahy, E.; Faulkner, D.J.; Xu, C.; Clardy, J. 5-Isothiocyanatopupukeanane from a sponge of the genus Axinyssa. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 5184–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wratten, S.J.; Faulkner, D.J.; Hirotsu, K.; Clardy, J. Diterpenoid Isocyanides from the Marine Sponge Hymeniacidon amphilecta. Tetrahedron 1978, 4345–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinski, T.F.; Faulkner, D.J.; Van Duyne, G.D.; Clardy, J. Three New Diterpene Isonitriles from a Palauan Sponge of the Genus Halichondria. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 3334–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avile, E.; Rodriguez, A.D.; Vincente, J. Two Rare-Class Tricyclic Diterpenes with Antitubercular Activity from the Caribbean Sponge Svenzea flava. Application of Vibrational Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy for Determining Absolute Configuration. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 22–11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.Y.; Faulkner, D.J.; Shumsky, J.S.; Hong, K.; Clardy, J. A sesquiterpene thiocyanate and three sesquiterpene isothiocyanates from the sponge Trachyopsis aplysinoides. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 2511–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.T.; Ichiba, T.; Yoshida, W.Y.; Scheuer, P.J.; Uchida, T.; Tanaka, J.; Higa, T. Two marine sesquiterpene thiocyanates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 4843–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Salvá, J.; Caíalos, R.F.; Faulkner, D.J. Sesquiterpene Thiocyanates and Isothiocyanates from Axinyssa aplysinoides. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3191–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasman, Y.; Edrada, R.A.; Wray, V.; Proksch, P. New 9-Thiocyanatopupukeanane Sesquiterpenes from the Nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa and Its Sponge-Prey Axinyssa aculeata. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1512–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusetani, N.; Wolstenholme, H.J.; Shinoda, K.; Asai, N.; Matsunaga, S.; Onuki, H.; Hirota, H. Two sesquiterpene isocyanides and a sesquiterpene thiocyanate from the marine sponge Acanthella cf. cavernosa and the Nudibranch Phyllidia ocellata. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 6823–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.Y.; Salva, J.; Catalos; Faulkner, D.J. Sesquiterpene thiocyanates and isothiocyanates from Axinyssa aplysinoides. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3191–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaževića, I.; Montaut, S.; Burčul, F.; Olsend, C.E.; Burowe, M.; Rollin, P.; Agerbirk, N. Glucosinolate structural diversity, identification, chemical synthesis and metabolism in plants. Phytochemistry 2020, 169, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasio, B.; Fattorusso, E.; Magno, S.; Mayol, L.; Pedone, C.; Santacroce, C.; Sica, D. Axisonitrile-3, axisothiocyanate-3 and axamide-3. Sesquiterpenes with a novel spiro[4,5]decane skeleton from the sponge Axinella cannabina. Tetrahedron 1976, 32, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

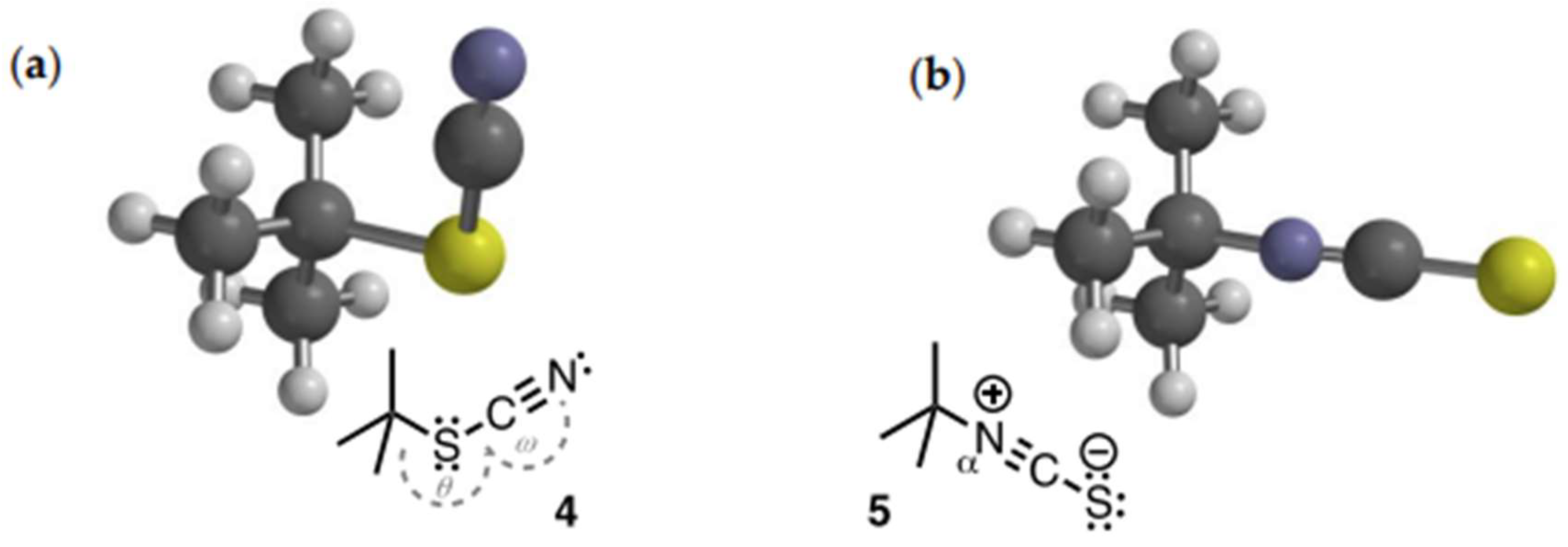

- The DFT minimized structure of 1-isocyano-1-methylcyclohexane (S1) displays similar bond parameters albeit with a slightly more ‘bent’ C-Na-C (θ = 175.5˚).

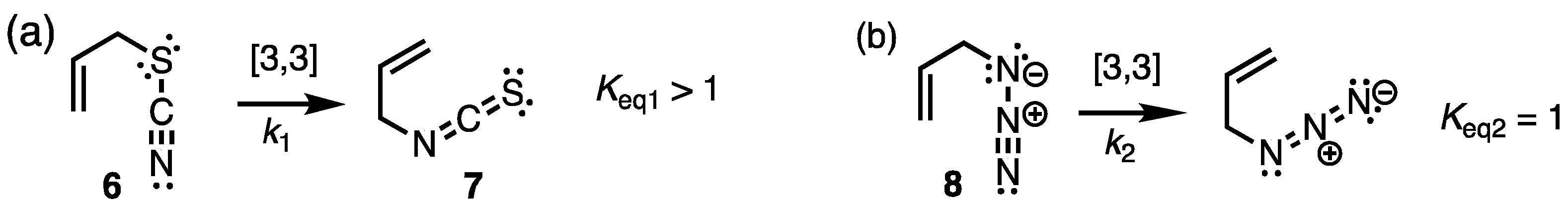

- Carlson, A.S.; Topczewski, J.J. Allylic azides: synthesis, reactivity, and the Winstein rearrangement. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 4406–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneux, A.; Winstein, S.; Young, W.G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 5956–5957. [CrossRef]

- Iliceto, A.; Fava, A.; Mazzucato, U. Thiocyanates and isothiocyanates. Equilibrium, kinetics and mechanisms of isomerization. Tetrahedron Lett. 1960, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, D.W. The Preparation and Isomerization of Allyl Thiocyanate. J. Chem. Ed. 1971, 48, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- At equilibrium in cyclohexane, allyl thiocyanate is undetectable, but in acetonitrile the mol fraction becomes 9-11%, a result consistent with the higher dipole moment of allyl isothiocyanate and an ionic component (dissociative) to the transition state.

- Knowles, C.J.; Bunch, A.W. Microbial Cyanide Metabolism. Adv. Micro. Physiol. 1986, 27, 73–111. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.E.; Bunch, A.W.; Knowles, C.J. Microbial cyanide and nitrile metabolism Sci. Prog., Oxf. 1987, 71, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, C.; Haas, D. Mechanism, regulation, and ecological role of bacterial cyanide biosynthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 2000, 173, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hering, C.; von Langermann, J.; Shulz, A. The Elusive Cyanoformate: An Unusual Cyanide Shuttle. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8282–8284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dose, B.; Niehs, S.P.; Scherlach, K.; Shahda, S.; Flórez, L.; Kaltenpoth, M.; Hertweck, C. Biosynthesis of Sinapigladioside, an Antifungal Isothiocyanate from Burkholderia Symbionts. ChemBioChem. 2021, 22, 1920–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlotek, M. D.; Bose, B.; Hertweck, C. Bacterial Isothiocyanate Biosynthesis by Rhodanese-Catalyzed Sulfur Transfer onto Isonitriles. ChemBioChem. 2024, 25, No–e202300732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Sobel, H.; Songstad, J. Nucleophilic Reactivity Constants toward Methyl Iodide and trans-[Pt(py)2Cl2]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluco, U.; Cattalini, U.; Basolo, F.; Pearson, R.G.; Turco, A. Nucleophilic Constants and Substrate Discrimination Factors for Substitution Reactions of Platinum (II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedemonte, N.; Caci, E.; Sondo, E.; Caputo, A.; Rhoden, K.; Pfeffer, U.; Di Candia, M.; Bandettini, R.; Ravazzolo, R.; Zegarra-Moran, O.; Galietta, L.J.V. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 5144–5153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshiki, M.; Fukushima, T.; Kawano, S.; Kasahara, Y.; Nakagawa, J. Thiocyanate Degradation by a Highly Enriched Culture of the Neutrophilic Halophile Thiohalobacter sp. Strain FOKN1 from Activated Sludge and Genomic Insights into Thiocyanate Metabolism. Microbes Environ. 2019, 34, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.; Raniga, P.; Garson, M. J. Biosynthesis of dichloroimines in the tropical marine sponge Stylotella aurantium. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7947–7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Yu, Z.-G.; Guo, Y.-W. New N-Containing Sesquiterpenes from Hainan Marine Sponge Axinyssa sp. Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 1553–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, G.; Mantegani, A.; Coppi, G. Terpene Compounds Mono- and Sesquiterpene Thiocyanates and Isothiocyanates J. Med. Chem. 1969, 12, 725–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interestingly, although allyl derivatives 6 and 7 exhibit good antibacterial properties, their geranyl and farnesyl analogs (e.g. 8b,c) showed no antibiotic activity.

- Simpson, S.; Raniga, P.; Garson, M. J. Biosynthesis of dichloroimines in the tropical marine sponge Stylotella aurantium. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7947–7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuso, P.; Scheuer, P.J. Long-chain α,ω-bisisothiocyanates from a marine sponge. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 4633–4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In Phyllidia varicosa, the nudibranch that depredates A. aculeata and sequesters 2g and 2h, the epimer ratio is altered: in the dorsal mantle it is 1:2, but about equimolar in the digestive organ. Fractionation of secondary metabolites by nudibranchs from their sponge diets (selective metabolism?) has been described before; for example the ratios of trisoxazole macrolides in the Spanish Dancer, Hexbranchus sanginues, are significantly altered from those in its dietary sponge, Halichondria sp. Pawlik, J. R.; Kernan, M. K.; Molinski, T. F.; Harper, M. K.; Faulkner, D. J. Defensive Chemicals of the Spanish Dancer Hexabranchus sanguineus, and its Egg Ribbons: Macrolides Derived from a Sponge Diet. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1988, 119, 99–109.

- Garson, M.J.; Simpson, J.S.; Flowers, A.E.; Dumdei, E.J. Cyanide and thiocyanate-derived functionality in marine organisms—Structures, biosynthesis and ecology. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta ur, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 21, Part B; pp. 329–372.

- Cimino, C.; De Rosa, S.; De Stefano, S.; Sodano, G. Marine natural products: New results from Mediterranean invertebrates. Pure Appl. Chem. 1986, 58, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, M.J. Biosynthesis of the novel diterpene isonitrile diisocyanoadociane by a marine sponge of the Amphimedon genus: Incorporation studies with sodium [14C] cyanide and sodium [2-14C] acetate. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fookes, C.J.R.; Garson, M.J.; MacLeod, J.K.; Skelton, B.W.; White, A.H. Biosynthesis of diisocyanoadociane, a novel diterpene from the marine sponge Amphimedon sp. Crystal structure of a monoamide derivative. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1988, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- It is felt that lack of detection of radiolabeled 3 after incubation with [2-14C]Gly is not paradoxical, but a consequence of below-threshold incorporation and much faster assimilation of these amino acids into the proteins of sponge tissue and other intermediary metabolism.

- A counter explanation would be that fraction of exogenous cyanide that is not incorporated into the structures of sponge TIs is rapidly and efficiently converted to NCS– by rhodanese in separate cellular compartments, spatially distal from the active sites of TI biosynthetic enzymes, and becomes unavailable for TC or ITC production.

- Dumdei, E.J.; Flowers, A.E.; Garson, M.J.; Moore, C.J. The Biosynthesis of Sesquiterpene Isocyanides and Isothiocyanates in the Marine Sponge Acanthella cavernosa (Dendy); Evidence for Dietary Transfer to the Dorid Nudibranch Phyllidiela pustulosa. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1997, 118A, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.S.; Garson, M.J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 3909–3912. [CrossRef]

- Human oxyhemoglobin can convert thiocyanate to cyanide. Seto, Y. Oxidative conversion of thiocyanate to cyanide by oxyhemoglobin during acid denaturation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995, 321, 245–254. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.S.; M.J. Thiocyanate Biosynthesis in the Tropical Marine Sponge Axinyssa n.sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 39, 5819–5822. [CrossRef]

| Entry | Nu: or Nu:– | 103.k2 /M–1.s–1 | Entry | Nu: or Nu:– | 103.k2 /M–1.s–1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MeOH | 1.3 x 10–7 | 7 | PhO– | 0.073 |

| 2 | NH3 | 0.041 | 8 | NCS– | 0.574 |

| 3 | N3– | 0.078 | 9 | NC– | 0.645 |

| 4 | Br– | 0.0798 | 10 | NCSe– | 9.13 |

| 5 | I– | 3.42 | 11 | PhS– | 1070 |

| 6 | (CH3)2S | 0.045 | 12 | S2O32– | 114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).