1. Introduction

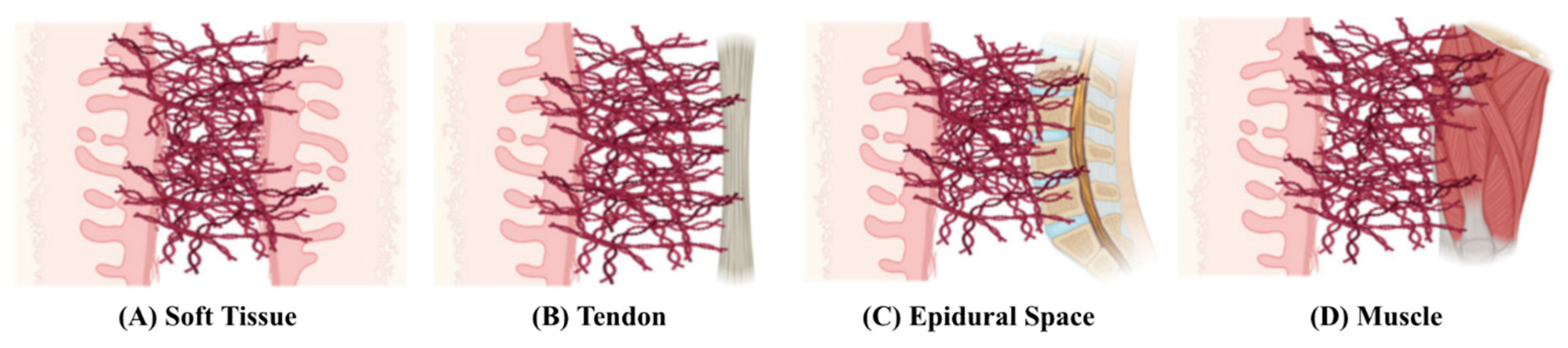

Adhesions are bands of fibrous tissue that form between different layers of tissues in the body, and they usually occur between soft tissue and other tissue types [

1], as shown in

Figure 1. Adhesions are mostly found in the abdomen and pelvis as a natural response to various inflammatory causes, with surgery being the most frequent cause [

2]. Given that the organs in the abdominopelvic cavity are all lined by the peritoneum, the pathophysiology of post-operative adhesion formation in the abdomen and pelvis is similar.

Although the formation of adhesions plays a vital role in the post-surgical healing process, they have been known to cause significant complications. For instance, the formation of peritoneal adhesions inhibits the movement of organs, which can then cause bowel obstruction as well as chronic abdominal pain [

3]. Consequently, numerous methods have been developed to prevent post-operative adhesions. While mechanical barriers are the most employed approach, their use is often limited to cases involving small incisions and restricted surgical access. Additionally, mechanical barriers can be challenging to apply to tissues with complex geometries and may adhere aggressively to the surgeon's gloves during use [

4].

With the recent advancements in nanotechnology, there has been a growing interest in its potential to prevent post-operative abdominal adhesions. However, research and clinical experience in this area remain limited. Thus, this paper aims to review the various nanotherapeutic approaches which have been developed to prevent post-operative abdominal adhesions and explore their potential for future clinical applications.

1.1. Pathophysiology of Post-Operative Abdominal Adhesion Formation

Post-operative adhesions occur in 50-90% of all open abdominal surgeries, representing a significant clinical problem that affects hundreds of millions of patients each year [

5]. These adhesions can lead to serious complications, making adhesion prevention a critical area of focus. Within ten years of abdominal or pelvic surgery, 35% of patients experienced readmission an average of 2.1 times due to disorders directly or potentially related to adhesions [

6]. To develop successful preventive strategies, understanding how various cells and factors contribute to adhesion formation is necessary. Simply put, adhesions arise when fibrin deposition occurs at a faster rate than fibrinolysis. However, in reality, the process of post-operative adhesion formation is complex and involves various systems, pathways, and cellular interactions [

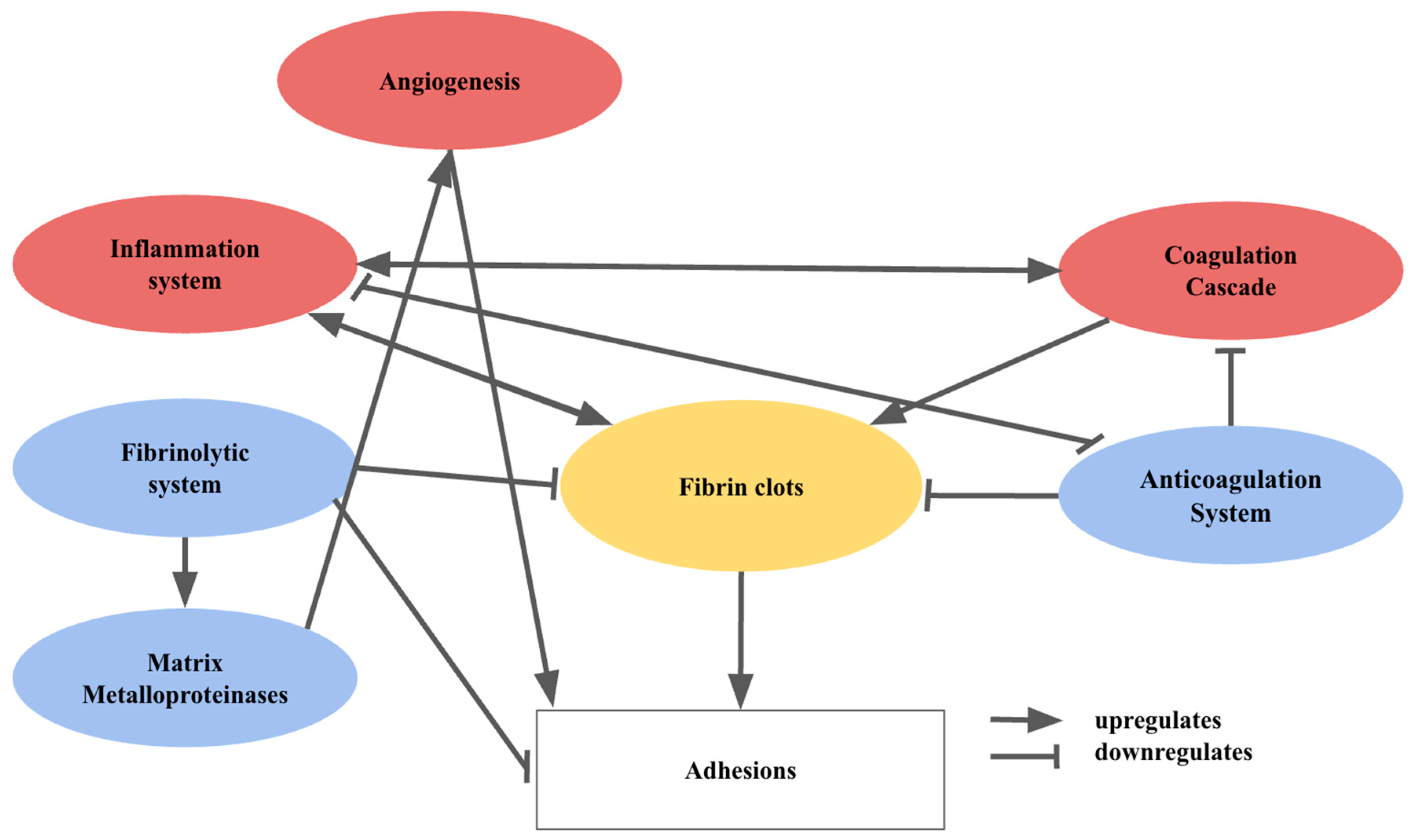

7]. The interactions between the main pathways and the cell types involved are illustrated in

Figure 2.

Surgery disrupts the epithelium or mesothelium on the basement membrane. The resultant exposure of the basement membrane triggers neutrophil and monocyte infiltration, which sparks inflammation and fibrin-rich exudate secretion during initial healing [

8]. Activated platelets release cytokines, chemokines, fibrinogen and fibrin which recruit macrophages, neutrophils and epithelial cells to the injury site, supporting inflammation and healing [

9]. At the same time, platelet aggregation and coagulation occur to reduce blood loss. The activated pro-coagulation factors culminate in fibrin monomer formation, in a process mediated by thrombin. The fibrin monomers will then aggregate with the activated platelets to form fibrin clots [

10]. Inflammation and coagulation are tightly intertwined. Inflammatory cytokines regulate the coagulation cascade, while inflammation is regulated by coagulation proteases, which influence cytokine and growth factor production [

11].

Haemostasis requires the tight regulation of coagulation through the anticoagulation system. In particular, the protein C pathway influences the formation of thrombin when thrombin binds to thrombomodulin. This upregulates the activation of protein C, and inhibits fibrin formation as well as coagulation [

12]. In addition, inflammation downregulates the protein C pathway and vice versa [

11]. The fibrinolytic system involves plasminogen activators (PA) and plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAI). The components of the fibrinolytic system rely on an intact mesothelium, and play a vital role in fibrin degradation and limiting adhesion formation [

9]. The fibrinolytic system promotes the action of matrix metalloproteinases, which degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) components [

13].

Angiogenesis involves ECM degradation and neovascularization [

14]. Though the exact mechanism is unclear, it is thought to enhance the formation of adhesions directly via the recruitment of pericytes, which adopt a fibroblastic phenotype. [

15]. Coagulation and inflammation promote fibrin deposition, while anticoagulation and fibrinolysis reduce deposition and break down the matrix [

7]. Persistent fibrin clots allow for the attachment of fibroblasts and inflammatory cells. Along with vascular formation, this promotes an organized matrix deposition, leading to adhesion formation. When the integrity of the mesothelium and basal membrane is compromised, fibrin deposition exceeds fibrinolysis, causing adhesions [

7].

In peritoneal adhesion formation, fibroblasts transform into an adhesion phenotype under hypoxia [

16], upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production to reoxygenate hypoxic tissue represented by fibrin clots [

17]. The degradation of ECM also upregulates adhesion formation [

9].

2. Therapeutic Models to Prevent Post-Operative Abdominal Adhesions

Bowel obstruction is a common complication of post-operative adhesions. In some cases, surgical adhesiolysis is required, where adhesion bands are cut to relieve the obstruction. However, adhesiolysis is expensive and time-consuming, can lead to longer hospitalisations, and can negatively impact patients’ quality of life. Thus, there is greater interest in methods to prevent adhesion formation [

2].

2.1. Pharmaceutical Strategies

Adjuvants are agents that either disrupt adhesion formation pathways or enhance inhibitory pathways. Early studies on fibrin in adhesions explored fibrinolytic agents like fibrinolysin, pepsin, trypsin, and PA [

18]. These agents promote fibrinolysis or directly target fibrin clots. Current studies examine tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and streptokinase. However, their effectiveness is limited, and side effects like bleeding have been observed.

Another approach is the regulation of local inflammation. While hyaluronic acid (HA) is primarily considered to be a mechanical barrier, it dissolves fibrin and is anti-inflammatory in nature [

19]. Although HA is an ideal anti-adhesion material, its rapid resorption limits its ability to prevent adhesions. Hence, methods to prolong and maximise its anti-adhesive properties are being studied. Other drugs which were studied include resveratrol [

20] and pirfenidone [

21], which target inflammatory cytokines, including transforming growth factor-beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Although they were promising, they have not been clinically evaluated, and may increase undesirable side effects [

22]. Other agents, such as anticoagulants and antioxidants [

23], have also been studied. Although some were proven to be promising in animals, there is no data that supports their efficacy.

Therapies that integrate mechanical barriers and drugs may be a feasible approach to preventing adhesions. However, some combinations such as Interceed® with heparin, as well as Seprafilm® with vitamin E, showed no improved efficacy [

24,

25], while others showed minimal improvements in animals [

26]. Although the use of adjuvants holds promise in theory, they present with inherent limitations. Due to the complexity and interconnectedness of these pathways, studies have suggested that a single extracellular mediator is insufficient in preventing adhesions, and utilising various synergistic agents may be necessary [

27,

28]. Further challenges include, the ability to deliver agents in a localised fashion and the permanency and side effects of the agents [

26,

29]. Therefore, more research and clinical trials are still needed to assess the safety and efficiency of these agents in different surgical procedures [

7].

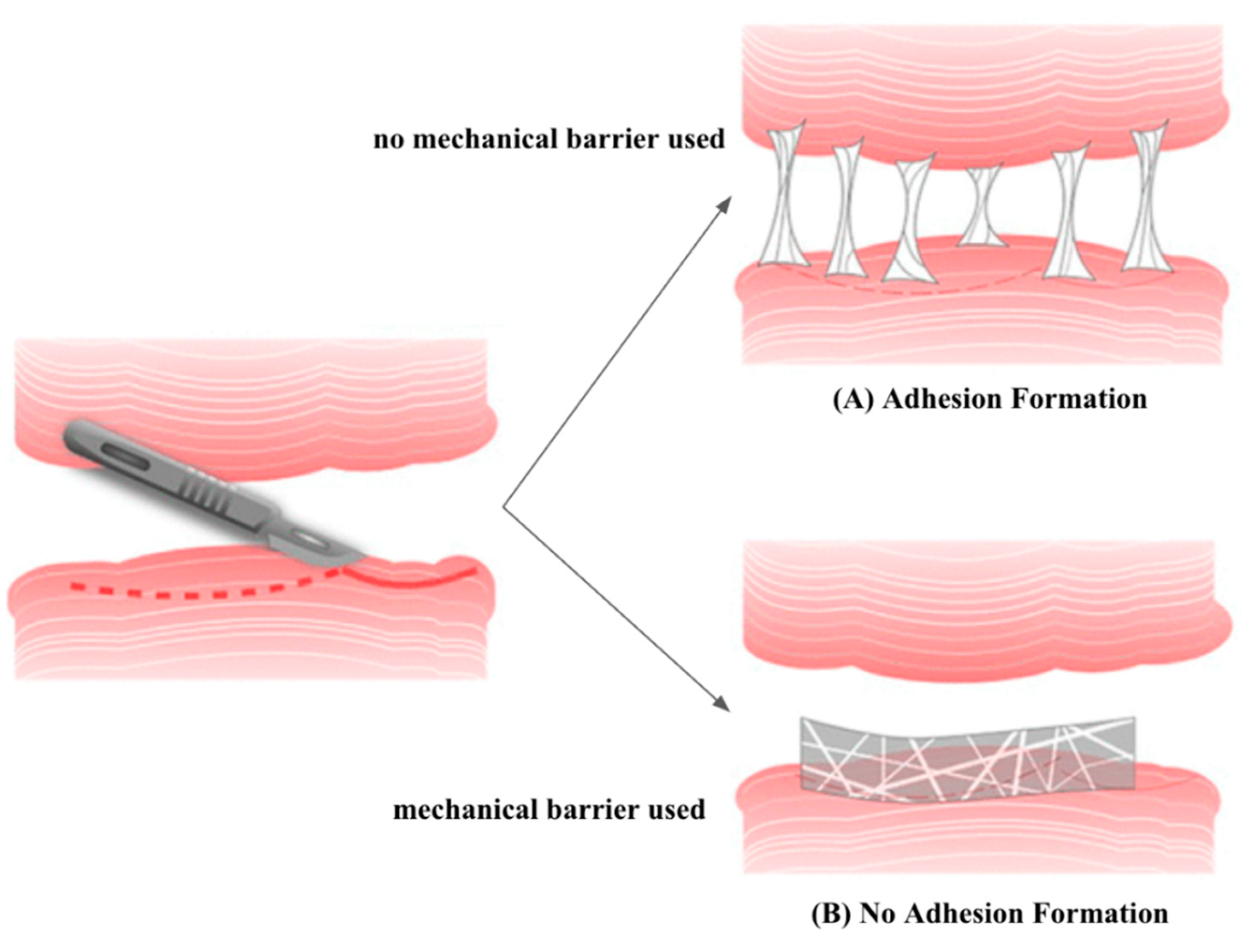

2.2. Mechanical Barriers

Apart from pharmaceutical strategies, there have also been efforts to develop mechanical barriers, which include solid polymers, gels, and liquids that have been widely used in various tissues to prevent adhesions [

30] (

Figure 3). However, in laparoscopic surgeries, liquid and gel barriers are more convenient to apply than solid ones [

31]. Significant research has explored natural and synthetic polymers as barriers in the in vivo and clinical context [

19]. In addition, combining mechanical barriers of different structures offers various possibilities that are being investigated [

32]. Recently, tissue grafts, including allogeneic amniotic membranes, have been studied, but they yielded poor results in peritoneal adhesion prevention [

7].

Recently, in a randomised clinical trial which involved 30 patients undergoing open abdominal surgery, Seprafilm® effectively reduced adhesions [

33]. Similarly, Interceed® reduced the formation of adhesions from 85.5% to 37.5% in a clinical study involving 38 patients undergoing reconstructive pelvic surgery [

34]. The safety of Adept® was shown in a clinical trial which involved 300 patients with small bowel obstruction [

35]. On the other hand, another double-blinded randomised clinical trial demonstrated that Adept® failed to prevent adhesions, but was safe to use [

36]. Sprayshield™ demonstrated effective reduction of adhesion formation [

7]. In a trial consisting of 43 patients, Hyalobarrier® decreased the extent of adhesion, but it was not proven to reduce adhesion sites [

37].

Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of several of the key studies that highlight the use of mechanical barriers.

Overall, although mechanical barriers in the form of films are commonly used, their application to irregular surfaces and cavities is challenging. This is due to their fragility, difficulty in handling, incompatibility with minimally invasive laparoscopic or catheter-based procedures, and limited efficacy (~25%). Novel technologies are needed to overcome clinical limitations [

38].

2.3. Gene Therapy

With the recent advances in molecular biology, gene therapy is a feasible substitute or complementing approach to adhesion prevention. Some strategies include delivering t-PA genes via viral vectors to promote fibrinolysis, using small interfering ribonucleic acid to reduce hypoxic gene expression, or decreasing the action of fibrinolysis inhibitors [

23]. However, these methods have yielded modest results. Similarly, transferring the hepatocyte growth factor gene via viral vectors demonstrated only some reduction in peritoneal adhesions in rats [

39].

3. Nanotherapeutics for the Prevention of Abdominal Adhesions

Currently, there are several nanotherapeutic solutions for the prevention of abdominal adhesions. These include nanocomposites, hydrogels and nanofibers.

3.1. Nanocomposites

Nanocomposites offer exceptional advantages in preventing post-operative adhesions, including their biocompatibility and enhanced mechanical characteristics. Furthermore, a wide range of nanosized organic and inorganic substances can be mixed to generate diverse nanocomposites with distinct physicochemical, physical, and biological properties [

40]. Wei et al. (2022) noticed that poly(dopamine) human keratinocyte growth factor nanoparticles combined with HA were not only effective in preventing post-operative adhesions in the abdomen in rats by reducing collagen deposition and fibrosis and inhibiting inflammatory responses, but also in promoting mesothelial cell repair in the injured peritoneum [

41].

A biologically targeted, photo-crosslinkable nanopatch (pCNP), which consists of two nanoparticles, for postsurgical adhesion prevention has also been developed. One of the nanoparticles will bind to the site of injury and deliver Dexamethasone 21-Palmitate, which is an anti-inflammatory drug that prevents adhesion formation. Based on the study’s trials which were conducted in a rat parietal peritoneum excision model, the pCNP developed was more effective in preventing surgical adhesions than Seprafilm, and did not show any significant toxicity [

42].

3.2. Hydrogels

A hydrogel is a water-soluble polymer network structure [

43], and it can be transformed into multiple forms due to its ease of processing [

44]. As such, hydrogels can be designed to possess favourable characteristics that would enable them to address the limitations of anti-adhesive products currently being used. This makes hydrogels an appealing alternative to commercially available barriers.

A recent study developed the nanocomposite hydrogel Collagen Aldehdeylated Poly(ethylene glycol) Cysteine HAS-18His Protein and Docetaxel (Col-APG-Cys@HHD) that is capable of preventing intraperitoneal adhesions while simultaneously inhibiting tumour growth. The hydrogel could adhere to the tissue on one side due to the presence of collagen, while the other side was effective in preventing the adhesion of proteins or cells, thus reducing the probability of peritoneal adhesion. The design of Col-APG-Cys@HHD not only overcame the limitations of traditional hydrogels that lack a combination of tissue adhesion and anti-biological pollution but also provided a means for both the prevention of post-operative abdominal adhesion and tumour recurrence with minimal side effects [

45]. Wang et al. (2019) designed a naproxen-loaded chitosan hydrogel which harnessed both the anti-adhesion properties of chitosan hydrogels and the analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of Naproxen. Upon evaluation of the hydrogel’s efficacy in preventing adhesions in a rodent abdominal adhesion model, it was found that the hydrogel was as effective as commercial products in preventing post-operative adhesion, and it also demonstrated stable drug release behaviour [

4].

A novel “nanoengineered hydrogel” barrier has been developed based on silicate nanoplatelets and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) to prevent post-operative adhesions. Due to its unique non-Newtonian properties, this novel nanoengineered hydrogel is injectable and sprayable. This advantageous feature allows for its application to large surface areas even in minimally invasive interventions and enables it to adapt to complex anatomies by coating their surface. Furthermore, the PEO component impedes cell adherence, provides physical separation between tissues, and inhibits the infiltration of collagen-secreting cells. Hence, this nanoengineered hydrogel is effective in preventing post-operative adhesions in a variety of surgical procedures. Of the 3 hydrogel formulae studied by the authors, the shear-thinning hydrogel barrier 10% by weight of silicate nanoplatelets, 3% by weight of PEO formulation was the best at preventing post-operative adhesions. However, all of the hydrogel formulae studied were shown to have better outcomes than Seprafilm® [

38].

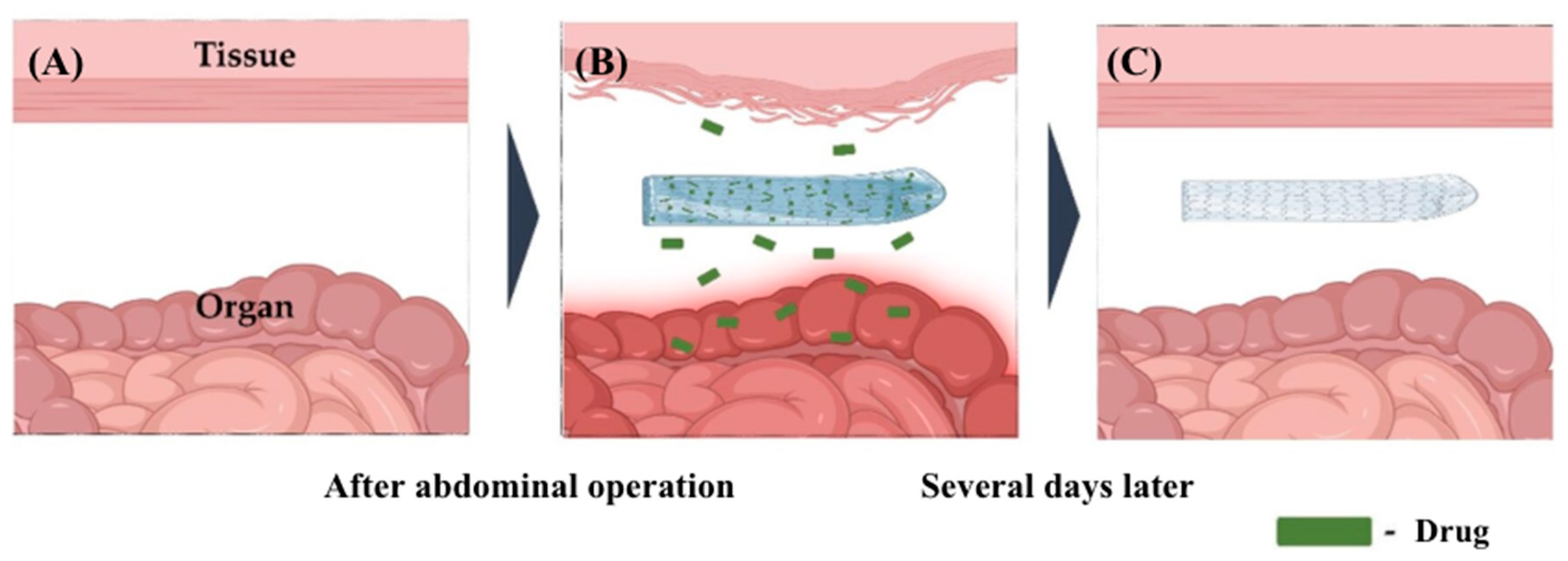

3.3. Nanofibers

Planar nanofibrous layers act as a barrier between layers of soft tissues. Some advantages include their potential biodegradability and ECM similarity [

30]. Wang et al. (2022) developed electrospun nanofibers with super-lubricated nano-skin grown on it. These nanofibers possess favourable tensile properties, biocompatibility, and friction coefficients below 0.025. Compared to Interceed® and DK-film®, they were more effective in preventing abdominal adhesions in rat models and had lower production costs [

46]. Recent studies show lidocaine has an anti-adhesive effect when loaded onto a poloxamer-alginate-calcium chloride barrier in a rat planar incision model [

47]. Building on this, Baek et al. (2020) developed a lidocaine-loaded alginate/carboxymethyl cellulose/PEO nanofiber film, controlling the degree of crosslinking to regulate lidocaine release and enhance alginate’s negative charge to reduce cell adhesion

. Calcium chloride is used to control drug release

[48].

Figure 4 illustrates the functionality of nanofiber films loaded with drugs.

Dinarvand et al. (2012) fabricated biodegradable nanofibers from poly(caprolactone) (PCL), nonabsorbable poly(ethylsulfone) (PES), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and poly(

l-lactide), comparing their anti-inflammatory and antiadhesive properties with Interceed®. PCL and PLGA were most noteworthy. PCL was as effective as Interceed® in preventing adhesions with less inflammation while PLGA had the least inflammation and was the best antiadhesive [

49]. Biodegradable PCL, which incorporated an antibiotic, was used to assess its anti-adhesive effect in a rat model. The study has shown that PCL, with or without the antibiotic loaded, decreased tissue adhesion, but the antibiotic significantly reduced adhesions and supported healing [

50].

A recent study incorporated curcumin (CUR) into PCL film casts and electrospun nanofibers [

51]. PCL films were good at preventing adhesions, possibly because of their mechanical properties. Furthermore, CUR-incorporated nanofibers outperformed PCL nanofibers without CUR. However, long-term in vivo studies and further investigation are needed [

51]. Jiang et al. (2013) created a double-layered nanofiber with an inner PCL layer loaded with HA to maintain tissue gliding. In rat cecum abrasion models, the double-layered membrane had significantly better antiadhesive effects than a single-layered PCL [

52]. Shin et al. (2014) constructed PLGA-based nanofibers that release poly(phenol epigallocatechin-3-

O-gallate) to inhibit adhesion formation and speed up the healing process. An in vivo rat model testing showed these membranes had a remarkable effect on preventing adhesions, similar to Interceed® and superior to PLGA [

53].

Another study blended PLGA with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) to reduce PLGA’s high hydrophobicity [

54]. The membranes prevented fibroblast attachment, proliferation, and penetration of abdominal structures in the rat cecum model while being biocompatible and biodegradable. The 5% PEG concentration showed the best anti-adhesive effect [

54]. Gholami et al. (2021) evaluated the adhesion efficacy of poly(urethane) (PU) nanofibers macroscopically and histopathologically on a rat cecal abrasion model. It was found that the 8% PU nanofibers had the best adhesion inhibition score. Additionally, PU degraded faster than PMS Steripack®, a commercially-available mesh [

55].

4. Regulatory Pathways for Nanotherapeutics

While the field of nanotherapeutics for adhesion prevention is still developing, there are already several research papers on the topic, though many are preclinical studies. These strategies hold much potential, and may even facilitate a shift towards precision medicine. However, any proposed strategy must be safe, effective, and biocompatible. Hence, all prospective agents must be evaluated rigorously in comprehensive clinical trials before they can be fully rolled out to be used universally [

56]. The primary development of any nanotherapeutic product includes tests to determine a product’s translational potential, which will then form the basis for further preclinical development. This involves tests for investigational new drug (IND) applications, new drug applications, and abbreviated new drug applications by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [

57].

Once a product is deemed to be a new research drug, investigations will be conducted to determine its efficacy and safety during clinical trials. Clinical trials consist of three phases: the first phase studies its safety, the second phase examines efficacy, and the third phase evaluates efficacy, safety and dosage. Afterwards, the FDA can submit an IND application for the endorsement of the new nanomedicine [

58]. The FDA regulations mandate that it is essential to determine their potential risks and hazards to biological systems [

59]. Nanotherapeutics must be biocompatible, which means that they would not elicit any undesired adverse reactions while performing their function [

60]. Therefore, a comprehensive test of its biocompatibility is required during the preclinical stage to resolve concerns about toxicology [

61]. These studies would then determine the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the nanotherapeutic agent before it is applied in the clinical context.

Some of the existing nanotherapeutic agents are almost progressing to the clinical stage of their trial. For instance, when the naproxen-loaded chitosan hydrogel was prepared, high concentrations of β-glycerolphosphate disodium salt pentahydrate (β-GP) and acid solvents were used [

4]. However, such high concentrations of β-GP may cause the hydrogel to have greater toxicity. Therefore, to make the naproxen-loaded chitosan hydrogel safe for clinical use in future, decreasing the concentration of β-GP or developing other thermosensitive chitosan hydrogels without acid solubilization would be necessary [

4].

5. Safety and Ethics of Nanotherapeutics

Despite the exciting prospects of using nanotherapeutics, there are still several concerns regarding its safety and associated ethical issues that need to be duly addressed.

5.1. Safety Concerns

There are several stakeholders affected by the potential safety hazards that chronic exposure to nanotherapeutics and nanopollution poses. These concerns should be promptly resolved should there be a widespread use of nanotherapeutics in future. The adverse effects and diseases that result from the use of nanotherapeutics are a cause for great concern. For instance, nanomaterial exposure and its subsequent accumulation can give rise to a multitude of complications, including cancers, Parkinson's disease, cardiovascular disease, Crohn's disease, and birth abnormalities [

62]. While it is still unclear as to how exactly the accumulation of nanomaterials gives rise to the aforementioned diseases, it is known that having a larger surface area would contribute to the increase in oxidative stress exerted by the nanotherapeutic, which would then give rise to a greater risk of inflammation and cytotoxicity in the lungs [

63,

64]. However, to fully elucidate the mechanisms involved in the disease process, the effects of chronic exposure to nanomaterials still require further detailed study.

If there are insufficient measures to prevent potential harm, prolonged exposure to nanomaterials may cause individuals who manufacture nanomaterials to have an increased risk of harm or actual harm. However, as the risk from nanomaterials is still not well-known, workers will have to make do with interim precautionary measures which have been extrapolated from the safety recommendations for known industrial fine and ultrafine particles. This is concerning as exposure to different nanomaterials can have varying degrees of risks; hence an ongoing evaluation of health risks is needed alongside continued communication and development of management plans to establish adequate safety precautions that will provide ample protection for workers [

65].

Furthermore, the process of manufacturing nanomaterials leads to the generation of waste that manifests as nanopollution [

66]. According to recent studies, toxic nanomaterials can float for days or weeks in air and water, creating significant dangers during manufacturing, shipping, handling, consumption, trash disposal, and recycling operations [

67]. The presence of nanomaterials in the environment also affects the food chain - the metal components of nanomaterials in the soil can be transferred from plant roots to edible plant parts [

68], thus giving rise to toxic effects on the food chain [

69].

5.2. Ethical Concerns

There is an abundance of ethical concerns that surround nanotherapeutics which will need to be addressed; two of these issues include the issues of unequal access and the potential inability to obtain proper informed consent from patients.

As nanomedicine involves the convergence of high-cost technologies, nanotherapeutics are likely to carry a significant cost, potentially making them inaccessible to financially challenged patients [

70]. Moreover, as the trailblazers in the field of nanomedical research are developed countries including the United States, European countries and China [

71], they are more likely to secure patents for new nanotherapeutics [

70]. This means that the issue of having unequal access to new medical technology between the developed and developing world would be further exacerbated, and patients in developing countries are less likely to enjoy the potential improvements in quality of life that nanotherapeutics could bring.

Furthermore, obtaining real informed consent from participants in nanomedical trials may prove to be challenging. As a result of the novel and developing nature of research in this field and the unknown and/or unpredictable aspects of the behaviour of nanotechnology in the human body, medical professionals may struggle to fully grasp the implications of nanomedical trials themselves and hence find it challenging to provide patients with the comprehensive explanation that they need to make an informed decision [

70]. In addition, the fact that the associated risks of using nanotherapeutics have not been fully established makes it even more likely that participants of the clinical trials would underestimate the potential risks of nanotherapeutics, which then presents further obstacles in obtaining fully informed consent from them [

72,

73].

6. Future Perspectives

The use of nanotechnology in preventing post-operative adhesions is an exciting area for future research work, with numerous innovative opportunities. Nanotherapeutics offer many benefits that the current therapeutic modalities have yet to cover, including a reduced risk of side effects. However, the biocompatibility of nanotherapeutics should be further investigated and the development of nanotechnology should proceed with careful consideration, bearing in mind ethical and safety concerns. Currently, the research on nanotherapeutics in animal models shows great promise, with significant efforts to apply these findings to human models for future clinical use. Further studies will help to prevent post-operative adhesions and reduce the healthcare burden of treating them. This is especially so, given the rise in healthcare costs, which is a growing concern universally. Therefore, to maximise cost efficiency, governments should acquire a deeper understanding of the cost-effectiveness of nanotherapeutics [

74].

7. Conclusions

Post-operative abdominal adhesions form due to the fibrin deposition rate exceeding the fibrinolysis rate after surgery. They cause significant complications including intestinal obstructions and chronic pain, hence necessitating a way to prevent them. Current methods like adhesiolysis, pharmaceuticals, inert polymers and functional biomaterials have limitations that nanotherapeutics may help overcome. The advantages of nanotherapeutics, including their low production cost, have been demonstrated in animal models for preventing post-operative abdominal adhesions, offering a promising outlook for their clinical application. Although further testing is needed, these approaches have the potential to significantly reduce the long-term healthcare burden.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| Col-APG-Cys@HHD |

collagen aldehdeylated poly(ethylene glycol) cysteine HAS-18His protein and docetaxel |

| CUR |

curcumin |

| ECM |

extracellular matrix |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| HA |

hyaluronic acid |

| IND |

investigational new drug |

| NDAs |

new drug applications |

| PA |

plasminogen activators |

| PAI |

plasminogen activator inhibitors |

| PAI-1 |

plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 |

| PCL |

poly(caprolactone) |

| pCNP |

photo-crosslinkable nanopatch |

| PEG |

poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PEO |

poly(ethylene oxide) |

| PES |

poly(ethylsulfone) |

| PLGA |

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PU |

poly(urethane) |

| t-PA |

tissue plasminogen activator |

| VEGF |

vascular endothelial growth factor |

| β-GP |

beta-glycerolphosphate disodium salt pentahydrate |

References

- Park, H., Baek, S., Kang, H., & Lee, D. (2020). Biomaterials to prevent post-operative adhesion. Materials, 13(14), 3056. [CrossRef]

- Nahirniak, P., & Tuma, F. (2022, September 19). Adhesiolysis. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/n/statpearls/article-29/.

- ten Broek, R. P., Issa, Y., van Santbrink, E. J., Bouvy, N. D., Kruitwagen, R. F., Jeekel, J., Bakkum, E. A., Rovers, M. M., & van Goor, H. (2013). Burden of adhesions in abdominal and pelvic surgery: Systematic review and met-analysis. BMJ, 347(oct03 1). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Pang, X., Luo, J., Wen, Q., Wu, Z., Ding, Q., Zhao, L., Yang, L., Wang, B., & Fu, S. (2019). Naproxen nanoparticle-loaded thermosensitive chitosan hydrogel for prevention of postoperative adhesions. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 5(3), 1580–1588. [CrossRef]

- Foster, D. S., Marshall, C. D., Gulati, G. S., Chinta, M. S., Nguyen, A., Salhotra, A., Jones, R. E., Burcham, A., Lerbs, T., Cui, L., King, M. E., Titan, A. L., Ransom, R. C., Manjunath, A., Hu, M. S., Blackshear, C. P., Mascharak, S., Moore, A. L., Norton, J. A., … Longaker, M. T. (2020). Elucidating the fundamental fibrotic processes driving abdominal adhesion formation. Nature Communications, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H., Moran, B. J., Thompson, J. N., Parker, M. C., Wilson, M. S., Menzies, D., McGuire, A., Lower, A. M., Hawthorn, R. J., O’Brien, F., Buchan, S., & Crowe, A. M. (1999). Adhesion-related hospital readmissions after abdominal and pelvic surgery: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet, 353(9163), 1476–1480. [CrossRef]

- Capella-Monsonís, H., Kearns, S., Kelly, J., & Zeugolis, D. I. (2019). Battling adhesions: From understanding to prevention. BMC Biomedical Engineering, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Hellebrekers, B. W., & Kooistra, T. (2011). Pathogenesis of postoperative adhesion formation. British Journal of Surgery, 98(11), 1503–1516. [CrossRef]

- Wong, R, S., Tan, T., Pang, A. S. R., & Srinivasan, D. K. (2025). The role of cytokines in wound healing: from mechanistic insights to therapeutic applications. Exploration of Immunology. 2025 (In Press).

- Furie, B., & Furie, B. (1988). The molecular basis of blood coagulation. Cell, 53(4), 505–518. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M., van der Poll, T., & Büller, H. R. (2004). Bidirectional relation between inflammation and coagulation. Circulation, 109(22), 2698–2704. [CrossRef]

- Esmon, C. (2000). The protein C pathway. Critical Care Medicine, 28(Supplement), 44–48. [CrossRef]

- Lijnen, H. R. (2002). Matrix metalloproteinases and cellular fibrinolytic activity. Biochemistry (Moscow), 67(1), 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Kisucka, J., Butterfield, C. E., Duda, D. G., Eichenberger, S. C., Saffaripour, S., Ware, J., Ruggeri, Z. M., Jain, R. K., Folkman, J., & Wagner, D. D. (2006). Platelets and platelet adhesion support angiogenesis while preventing excessive hemorrhage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(4), 855–860. [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, L. A. (2016). Angiogenesis and wound repair: When enough is enough. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 100(5), 979–984. [CrossRef]

- Saed, G. M., & Diamond, M. P. (2004). Molecular characterization of postoperative adhesions: The adhesion phenotype. The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, 11(3), 307–314. [CrossRef]

- Imudia, A., Kumar, S., Saed, G., & Diamond, M. (2008). Pathogenesis of intra-abdominal and pelvic adhesion development. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 26(04), 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Hellebrekers, B. W. J., Trimbos-Kemper, T. C. M., Trimbos, J. B. M. Z., Emeis, J. J., & Kooistra, T. (2000). Use of fibrinolytic agents in the Prevention of Postoperative Adhesion Formation. Fertility and Sterility, 74(2), 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Feng, X., Liu, B., Yu, Y., Sun, L., Liu, T., Wang, Y., Ding, J., & Chen, X. (2017). Polymer materials for prevention of postoperative adhesion. Acta Biomaterialia, 61, 21–40. [CrossRef]

- Wei, G., Chen, X., Wang, G., Fan, L., Wang, K., & Li, X. (2016). Effect of resveratrol on the prevention of intra-abdominal adhesion formation in a rat model. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry, 39(1), 33–46. [CrossRef]

- Bayhan, Z., Zeren, S., Kocak, F. E., Kocak, C., Akcılar, R., Kargı, E., Tiryaki, C., Yaylak, F., & Akcılar, A. (2016). Antiadhesive and anti-inflammatory effects of pirfenidone in postoperative intra-abdominal adhesion in an experimental rat model. Journal of Surgical Research, 201(2), 348–355. [CrossRef]

- Imai, A., Takagi, H., Matsunami, K., & Suzuki, N. (2010). Non-barrier agents for postoperative adhesion prevention: Clinical and preclinical aspects. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 282(3), 269–275. [CrossRef]

- Atta, H. M. (2011). Prevention of peritoneal adhesions: A promising role for gene therapy. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 17(46), 5049. [CrossRef]

- Reid, R. L., Hahn, P. M., Spence, J. E. H., Tulandi, T., Yuzpe, A. A., & Wiseman, D. M. (1997). A randomized clinical trial of oxidized regenerated cellulose adhesion barrier (Interceed, TC7) alone or in combination with heparin. Fertility and Sterility, 67(1), 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Corrales, F., Corrales, M., & Schirmer, C. C. (2008). Preventing intraperitoneal adhesions with vitamin E and sodium hyaluronate/carboxymethylcellulose: A comparative study in rats. Acta Cirurgica Brasileira, 23(1), 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Ward, B. C., & Panitch, A. (2011). Abdominal adhesions: Current and novel therapies. Journal of Surgical Research, 165(1), 91–111. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, E., Coentro, J. Q., & Zeugolis, D. I. (2018). Advancements and Challenges in Multidomain Multicargo Delivery Vehicles. Advanced Materials, 30(13). [CrossRef]

- Coentro, J. Q., Pugliese, E., Hanley, G., Raghunath, M., & Zeugolis, D. I. (2019). Current and upcoming therapies to modulate skin scarring and fibrosis. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 146, 37–59. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J. P., Tsang, H. H., Cheung, J. J., Yu, H. H., Leung, G. K., & Law, W. L. (2009). Adjuvant therapy for the reduction of postoperative intra-abdominal adhesion formation. Asian Journal of Surgery, 32(3), 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Klicova, M., Rosendorf, J., Erben, J., & Horakova, J. (2023). Antiadhesive nanofibrous materials for medicine: Preventing undesirable tissue adhesions. ACS Omega, 8(23), 20152–20162. [CrossRef]

- ten Broek, Richard P., Bakkum, E. A., Laarhoven, C. J., & van Goor, H. (2016). Epidemiology and prevention of postsurgical adhesions revisited. Annals of Surgery, 263(1), 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Ezhilarasu, H., Vishalli, D., Dheen, S. T., Bay, B.-H., & Srinivasan, D. K. (2020). Nanoparticle-based Therapeutic Approach for diabetic wound healing. Nanomaterials, 10(6), 1234. [CrossRef]

- Stawicki, S. P., Green, J. M., Martin, N. D., Green, R. H., Cipolla, J., Seamon, M. J., Eiferman, D. S., Evans, D. C., Hazelton, J. P., Cook, C. H., & Steinberg, S. M. (2014). Results of a prospective, randomized, controlled study of carboxymethylcellulose sodium hyaluronate adhesion barrier in trauma open abdomens. Journal of Surgical Research, 186(2), 585. [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T., Nishizawa, H., Nishio, E., & Kadowaki, M. (2000). Postoperative adhesion prevention with an oxidized regenerated cellulose adhesion barrier in infertile women. The Journal of reproductive medicine, 45(5), 387–389.

- Sakari, T., Sjödahl, R., Påhlman, L., & Karlbom, U. (2016). Role of icodextrin in the prevention of small bowel obstruction. Safety randomized patients control of the first 300 in the adept trial. Colorectal Disease, 18(3), 295–300. [CrossRef]

- Trew, G., Pistofidis, G., Pados, G., Lower, A., Mettler, L., Wallwiener, D., Korell, M., Pouly, J.-L., Coccia, M. E., Audebert, A., Nappi, C., Schmidt, E., McVeigh, E., Landi, S., Degueldre, M., Konincxk, P., Rimbach, S., Chapron, C., Dallay, D., … DeWilde, R. (2011). Gynaecological Endoscopic Evaluation of 4% icodextrin solution: A European, multicentre, double-blind, randomized study of the efficacy and safety in the reduction of de novo adhesions after laparoscopic gynaecological surgery. Human Reproduction, 26(8), 2015–2027. [CrossRef]

- Mais, V., Bracco, G. L., Litta, P., Gargiulo, T., & Melis, G. B. (2006). Reduction of postoperative adhesions with an auto-crosslinked hyaluronan gel in gynaecological laparoscopic surgery: A blinded, controlled, randomized, multicentre study. Human Reproduction, 21(5), 1248–1254. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Esparza, G. U., Wang, X., Zhang, X., Jimenez-Vazquez, S., Diaz-Gomez, L., Lavoie, A.-M., Afewerki, S., Fuentes-Baldemar, A. A., Parra-Saldivar, R., Jiang, N., Annabi, N., Saleh, B., Yetisen, A. K., Sheikhi, A., Jozefiak, T. H., Shin, S. R., Dong, N., & Khademhosseini, A. (2021). Nanoengineered shear-thinning hydrogel barrier for preventing postoperative abdominal adhesions. Nano-Micro Letters, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-J., Wu, C.-T., Duan, H.-F., Wu, B., Lu, Z.-Z., & Wang, L. (2006). Adenoviral-mediated gene expression of hepatocyte growth factor prevents postoperative peritoneal adhesion in a rat model. Surgery, 140(3), 441–447. [CrossRef]

- Kargozar, S., Gorgani, S., Nazarnezhad, S., & Wang, A. Z. (2023). Biocompatible nanocomposites for postoperative adhesion: A state-of-the-art review. Nanomaterials, 14(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Wei, G., Wang, Z., Liu, R., Zhou, C., Li, E., Shen, T., Wang, X., Wu, Y., & Li, X. (2022). A combination of hybrid polydopamine-human keratinocyte growth factor nanoparticles and sodium hyaluronate for the efficient prevention of postoperative abdominal adhesion formation. Acta Biomaterialia, 138, 155–167. [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y., Yang, F., Bloomquist, C., Xia, Y., Sun, B., Qi, Y., Wagner, K., Montgomery, S. A., Zhang, T., & Wang, A. Z. (2019). Biologically targeted photo-crosslinkable nanopatch to prevent postsurgical peritoneal adhesion. Advanced Science, 6(19). [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E. M. (2015). Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A Review. Journal of Advanced Research, 6(2), 105–121. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y., Guo, D., An, Q., Xiao, Z., Zhai, S., & Zhai, B. (2018). Hydrogels with diffusion-facilitated porous network for improved adsorption performance. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering, 35(12), 2384–2393. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Wang, H., Chen, H., Ling, Y., Xi, Z., Lv, M., & Chen, J. (2023). PH-responsive nanocomposite hydrogel for simultaneous prevention of postoperative adhesion and tumor recurrence. Acta Biomaterialia, 158, 228–238. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yi, Xu, Y., Zhai, W., Zhang, Z., Liu, Y., Cheng, S., & Zhang, H. (2022). In-situ growth of robust superlubricated nano-skin on electrospun nanofibers for post-operative adhesion prevention. Nature Communications, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Choi, G. J., Kang, H., Hong, M. E., Shin, H. Y., Baek, C. W., Jung, Y. H., Lee, Y., Kim, J. W., Park, I. K., & Cho, W. J. (2017). Effects of a lidocaine-loaded poloxamer/alginate/CACL2 mixture on postoperative pain and adhesion in a rat model of incisional pain. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 125(1), 320–327. [CrossRef]

- Baek, S., Park, H., Park, Y., Kang, H., & Lee, D. (2020). Development of a lidocaine-loaded alginate/CMC/PEO electrospun nanofiber film and application as an anti-adhesion barrier. Polymers, 12(3), 618. [CrossRef]

- Dinarvand, P., Hashemi, S. M., Seyedjafari, E., Shabani, I., Mohammadi-Sangcheshmeh, A., Farhadian, S., & Soleimani, M. (2012). Function of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanofiber in reduction of adhesion bands. Journal of Surgical Research, 172(1). [CrossRef]

- Bölgen, N., Vargel, Korkusuz, P., Menceloğlu, Y. Z., & Pişkin, E. (2006). In vivo performance of antibiotic embedded electrospun PCL membranes for prevention of abdominal adhesions. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 81B(2), 530–543. [CrossRef]

- Babadi, D., Rabbani, S., Akhlaghi, S., & Haeri, A. (2022). Curcumin polymeric membranes for postoperative peritoneal adhesion: Comparison of nanofiber vs. film and phospholipid-enriched vs. non-enriched formulations. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 614, 121434. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Wang, W., Yan, H., & Fan, C. (2013). Prevention of intra-abdominal adhesion by Bi-Layer Electrospun Membrane. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14(6), 11861–11870. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. C., Yang, W. J., Lee, J. H., Oh, J.-W., Kim, T. W., Park, J.-C., Hyon, S.-H., & Han, D.-W. (2014). PLGA nanofiber membranes loaded with epigallocatechin-3-o-gallate are beneficial to prevention of postsurgical adhesions. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 4067. [CrossRef]

- Li, Jian, Zhu, J., He, T., Li, W., Zhao, Y., Chen, Z., Zhang, J., Wan, H., & Li, R. (2017). Prevention of intra-abdominal adhesion using electrospun PEG/PLGA nanofibrous membranes. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 78, 988–997. [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A., Abdoluosefi, H. E., Riazimontazer, E., Azarpira, N., Behnam, M., Emami, F., & Omidifar, N. (2021). Prevention of postsurgical abdominal adhesion using electrospun TPU nanofibers in rat model. BioMed Research International, 2021, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Fatehi Hassanabad, A., Zarzycki, A. N., Jeon, K., Dundas, J. A., Vasanthan, V., Deniset, J. F., & Fedak, P. W. (2021). Prevention of post-operative adhesions: A comprehensive review of present and emerging strategies. Biomolecules, 11(7), 1027. [CrossRef]

- Tyner, K. M., Zou, P., Yang, X., Zhang, H., Cruz, C. N., & Lee, S. L. (2015). Product quality for nanomaterials: Current U.S. experience and perspective. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology, 7(5), 640–654. [CrossRef]

- Ventola C. L. (2017). Progress in Nanomedicine: Approved and Investigational Nanodrugs. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 42(12), 742–755.

- Juillerat-Jeanneret, L., Dusinska, M., Fjellsbø, L. M., Collins, A. R., Handy, R. D., & Riediker, M. (2013). Biological impact assessment of nanomaterial used in nanomedicine. Introduction to the nanotest project. Nanotoxicology, 9(sup1), 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. M. (2012). Biocompatibility. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Biocompatibility&author=Anderson,+J.M.&publication_year=2012&journal=Polym.+Sci.+A+Compr.+Ref.+10+Vol.+Set&volume=9&pages=363%E2%80%93383.

- Hussain, S. M., Warheit, D. B., Ng, S. P., Comfort, K. K., Grabinski, C. M., & Braydich-Stolle, L. K. (2015). At the crossroads of nanotoxicologyin vitro: Past achievements and current challenges. Toxicological Sciences, 147(1), 5–16. [CrossRef]

- Asmatulu, R. (2011). Toxicity of nanomaterials and recent developments in lung disease. Bronchitis. [CrossRef]

- Nel, A., Xia, T., Mädler, L., & Li, N. (2006). Toxic potential of materials at the Nanolevel. Science, 311(5761), 622–627. [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster, G., Oberdörster, E., & Oberdörster, J. (2005). Nanotoxicology: An emerging discipline evolving from studies of Ultrafine Particles. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113(7), 823–839. [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P. A., & Salamanca-Buentello, F. (2006). Ethical and scientific issues of nanotechnology in the workplace. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 12(5), 1319–1332. [CrossRef]

- Asmatulu, R., Zhang, B., & Asmatulu, E. (2013). Safety and ethics of nanotechnology. Nanotechnology Safety, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Abaszadeh, F., Ashoub, M. H., Khajouie, G., & Amiri, M. (2023). Nanotechnology development in surgical applications: Recent trends and developments. European Journal of Medical Research, 28(1). [CrossRef]

- Vittori Antisari, L., Carbone, S., Bosi, S., Gatti, A., & Dinelli, G. (2018). Engineered nanoparticles effects in soil-plant system: Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) study case. Applied Soil Ecology, 123, 551–560. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J. P., Mucha, A. P., Francisco, T., Gomes, C. R., & Almeida, C. M. (2017). Silver nanoparticles uptake by salt marsh plants – implications for phytoremediation processes and effects in Microbial Community Dynamics. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 119(1), 176–183. [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S., Lee, I. H., Kim, S., Lee, J.-H., & Kim, H. (2023). Ethical and legal challenges in Nanomedical Innovations: A scoping review. Frontiers in Genetics, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N. L. (2019). Nanomedicine: Insights from a bibliometrics-based analysis of Emerging Publishing and Research trends. Medicina, 55(12), 785. [CrossRef]

- Atalla, K., Chaudhary, A., Eshaghian-Wilner, M. M., Gupta, A., Mehta, R., Nayak, A., Prajogi, A., Ravicz, K., Shiroma, B., & Trivedi, P. (2016). Ethical, privacy, and intellectual property issues in nanomedicine. Wireless Computing in Medicine, 567–600. [CrossRef]

- Resnik, D. B., & Tinkle, S. S. (2007). Ethics in Nanomedicine. Nanomedicine, 2(3), 345–350. [CrossRef]

- Weissig, V., & Guzman-Villanueva, D. (2015). Nanopharmaceuticals (part 2): Products in the pipeline. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 1245. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).