1. Introduction

Selective laser sintering (SLS) is the subject of extensive research, as the properties of materials, machinery, and postprocessing techniques are still being studied [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Research often focuses on studying the effects of the process on the powder, as this powder can be recycled and may reduce its environmental impact. This has drawn attention within the scientific community because of its potential for being environmentally friendly and sustainable [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Studies have investigated how machine parameters impact the physicochemical properties of PA12 powder before and after sintering [

10,

11,

12].

Feifei et al. [

16] reported that the powder aging time affects the thermal properties, particle size, and mechanical strength postmanufacturing.

Yang et al. [

17] noted that varying powder mix proportions influence part of the performance.

Martynková et al. [

18] reported differences in particle size and melting temperature when a 50–50 blend of new and recycled powder was used. These studies have yielded extensive data on the physicochemical properties of materials under these conditions. However, many of these studies concentrate on investigations involving a 1:1 powder ratio or, in some cases, unused materials. This poses a challenge, as the use of 50% or more combinations of unused powder suggests a greater investment in raw materials [

13,

14,

15]. Research has focused on these powder concentrations because constant reuse of powder causes orange peel defects in parts, a phenomenon that still lacks complete understanding [

19].

Parts made with 70% recycled powder show good resistance and surface quality, reducing the need for new materials [

20]. The effects on the material after multiple sintering cycles are unclear. The relationships among the thermal properties, particle size, and crystal morphology are not well understood [

21,

22]. For this reason, this study examined the effects of using a 70% recycled and 30% virgin powder blend before and after two sintering cycles on the structure, morphology, particle size, crystalline structure, and composition of the blend, which could influence the printed parts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1). Powder

Virgin and recycled EOS powder PA 12 was employed before and after the sintering process. The particle size was determined via SEM on a Vega 3 Tetscam instrument with a gold metallized sample. The particle size was evaluated via ImageJ software with four SEM images. The mixture conditions (70% recycled before one sintering cycle, 30% virgin) were analyzed before the sintering process. A sintering process was performed in an EOS Formiga P110 Velocid with standard machine parameters with a CO2 laser power of 30 W, a scan speed of 5 m s−1, a layer thickness of 0.12 mm, and a build rate of 1.2 l/h. The powder population was extracted after the pieces were separated and mixed, 10 g of material was extracted, and the remainder was placed in the machine cube again. This population was then used for the next sintering cycle, and a sample was extracted from a mixed volume that was retired.

2.2). Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed via a SHIMADZU IRAffinity-1S (Japan) spectrophotometer via the attenuated total reflection (ATR) technique. The measurement conditions were as follows: a spectral resolution of 8 cm-1, 64 scans per spectrum and a wavenumber range between 400–200 cm-1.

2.3). Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

A Mettler Toledo Differential Scanning Calorimeter (Germany) 1-500/227 was used for thermal characterization. The temperature range was between 25 °C and 200 °C, with a heating and cooling rate of 10 °C/min in a N2 atmosphere.

2.4). X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The powder crystalline structure was determined via a Philips diffractometer (Germany) with a 30 kV voltage and 20 mA current, working in the Bragg‒Brentano configuration with K alpha signals from the copper anode (γ = 0.1542 nm), between 2Θ values of 5–50° and a step size of 0.02°.

2.5). Microtome

The crystals of the powder particles were observed under a Karll Zeiss (Germany) polarized microscope. A wave polarizer with a quarter-wave retarder was used. A microtome with macro search HP35 high-profile blades was used for sample cutting.

2.5). Statistical Analysis

Three quantities for each powder condition were randomly selected. Owing to the nonnormality of the distributions, randomization was performed, nonparametric data were evaluated via the Kruskal‒Wallis (2500 particles per condition) test, and pairwise comparisons were performed via the Bonferroni adjustment test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1). Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

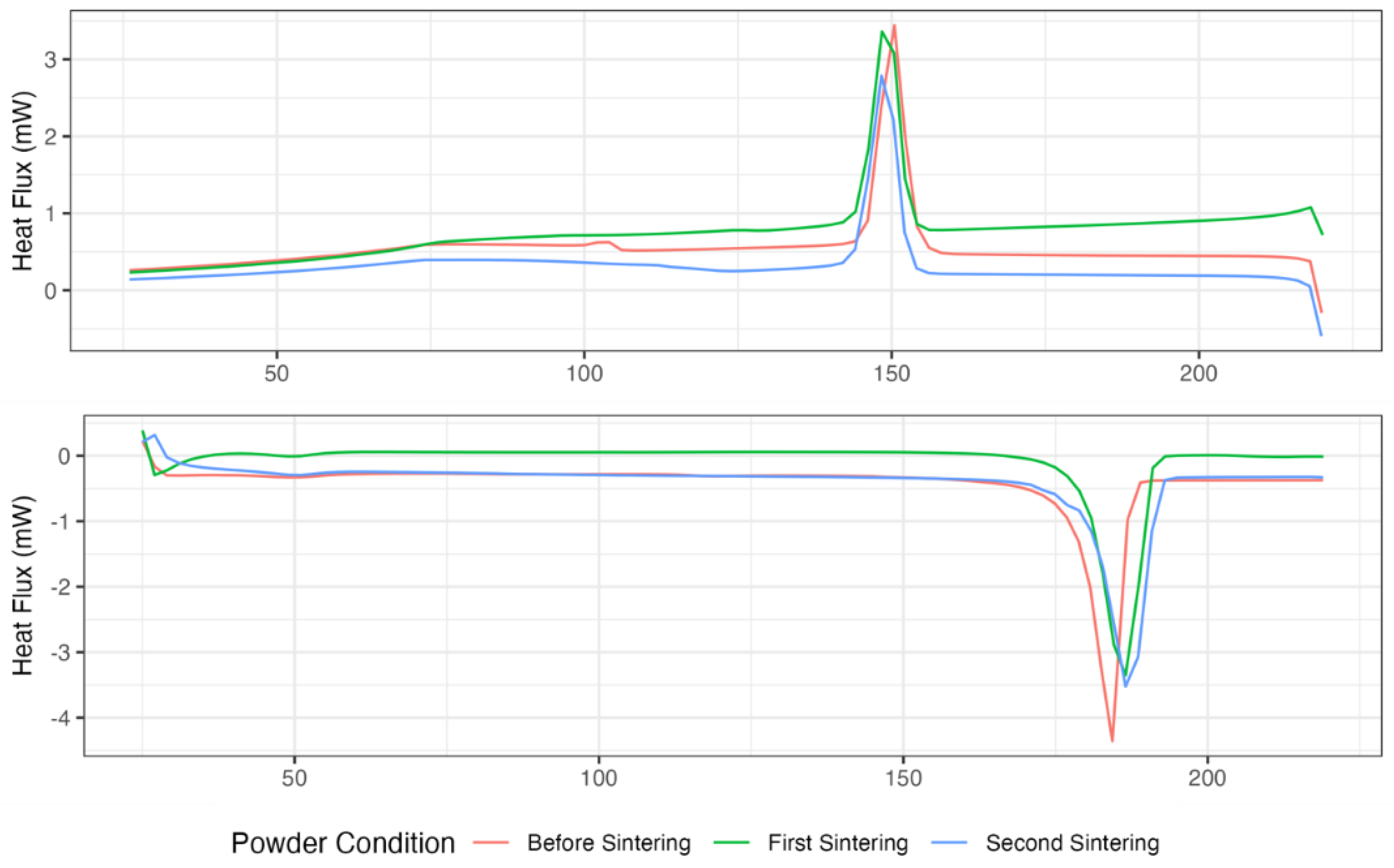

The DSC spectrum of the PA12 powder is displayed in red before sintering, blue for the first sintering, and green for the second sintering (

Figure 1).

Figure 1 (upper) indicates endothermic behavior, revealing that the crystallization temperatures were lower in both the first and second sintering conditions than in the presintering conditions.

Figure 1 (lower) shows the exothermic behavior, and it is evident that the before-sintering powder shifted toward lower melting temperatures than did the postsintering powder. Although the first and second sintering conditions had similar behaviors, the second condition slightly shifted toward higher melting temperature values.

Table 1 shows the crystallinity percentage (C.P.) values of the powder before and after the sintering cycles. Compared with those of the initial powder, the first and second sintering conditions resulted in 11.98% and 9.76% greater crystallinity percentages, respectively. The first and second sintering cycles increased the melting temperature (Tm) by 1.09 and 1.62%, respectively. Furthermore, the crystallization temperature decreased by 0.66% in the first sample and 0.96% in the second sample compared with that of the mixed powder. Finally, the sintering window (S.W.) increased by 1.68% in the first and 2.27% in the second sintering.

An increase in the C.P. was observed after the sintering process, and this behavior may be associated with the powder being subjected to temperatures above the Tc. Owing to these thermal conditions, the accumulation of polymeric chains in all powder conditions is favored, resulting in an annealing process [

23,

24]. Research, such as that of [

25,

26], shows a decay in the CP as a function of the number of sintering cycles. In contrast, the increase in C.P. suggests that the powder’s state and proximity to the laser are essential. Short distances would lead to a more aggressive temperature change, decreasing the C.P. Therefore, the second process would have a lower C.P. value since it could have been in a zone closer to the laser and produced faster cooling.

3.2). X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

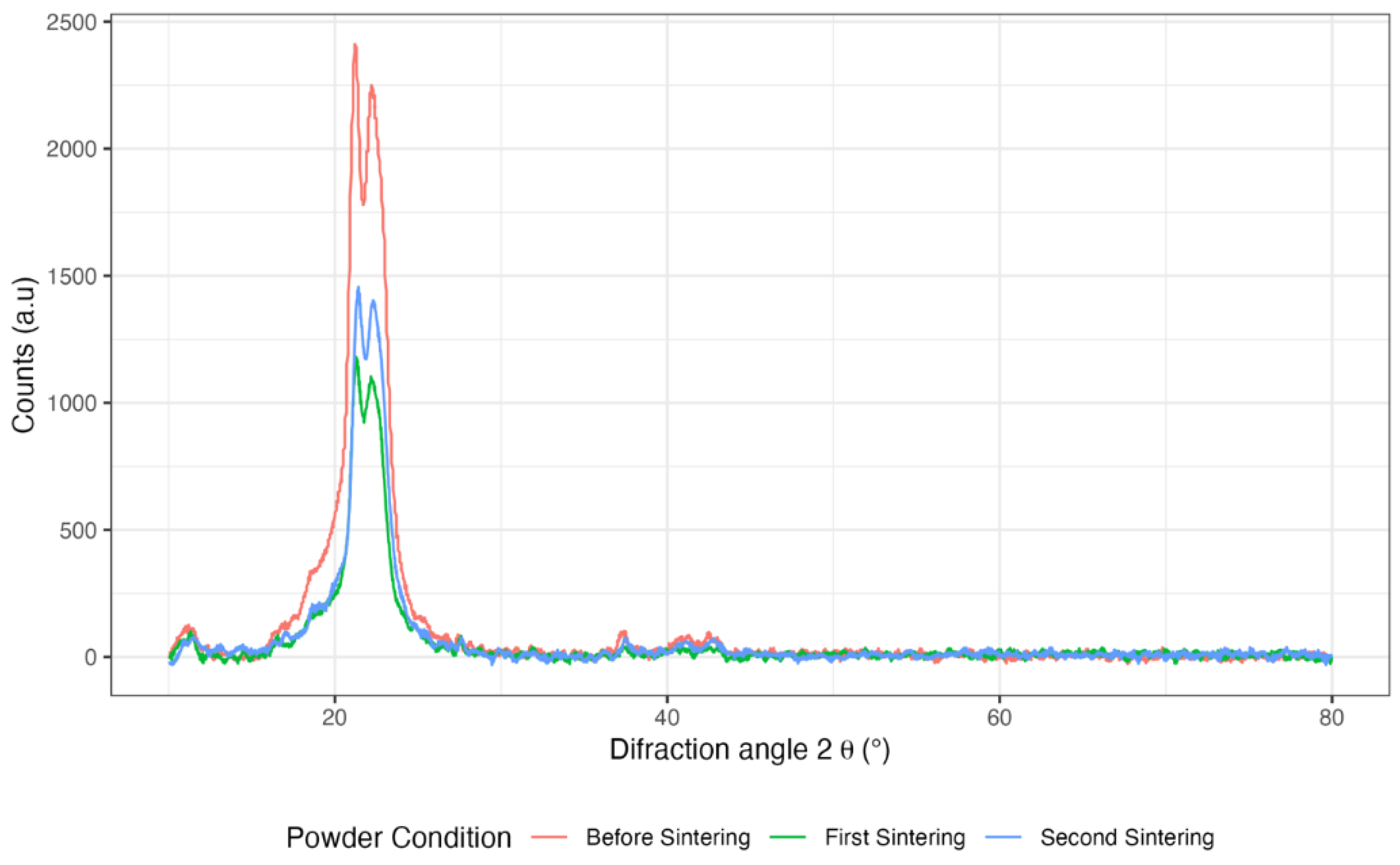

Figure 2 shows the XRD spectrum of the PA12 powder samples. Two main signals corresponding to the phase were observed. The polyamide structure crystallizes in the alpha phase (monoclinic) and gamma crystals (pseudohexagonal).

Table 2 below shows the angles corresponding to the phases of PA12. XRD revealed the characteristic gamma and alpha signals of PA12 [

27,

28]. There are no appreciable changes in either technique under powder conditions, suggesting that the increase in crystallinity could be associated with agglomerated chains and is not due to the appearance of new phases in the powder material.

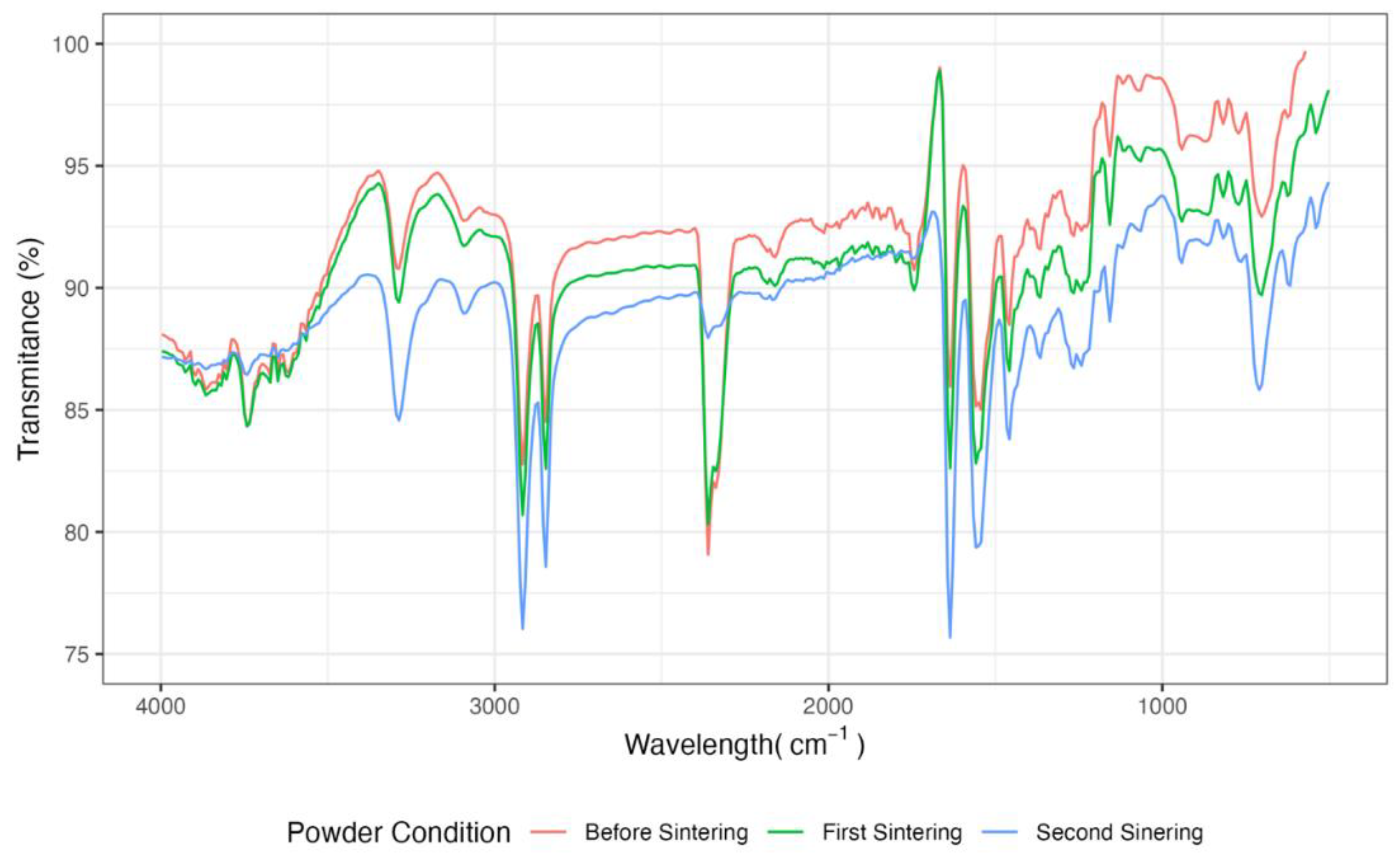

3.3). Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Figure 3 shows the IR spectra of PA powder under different conditions. Signals corresponding to the amide groups were observed. The amide IV group (bending) was observed at 632 cm

-1, the amide III group (stretching) at 1275 cm

-1 and 1578 cm

-1, the amide II group (bending), and the amide I group (stretching) at 1654 cm

-1.

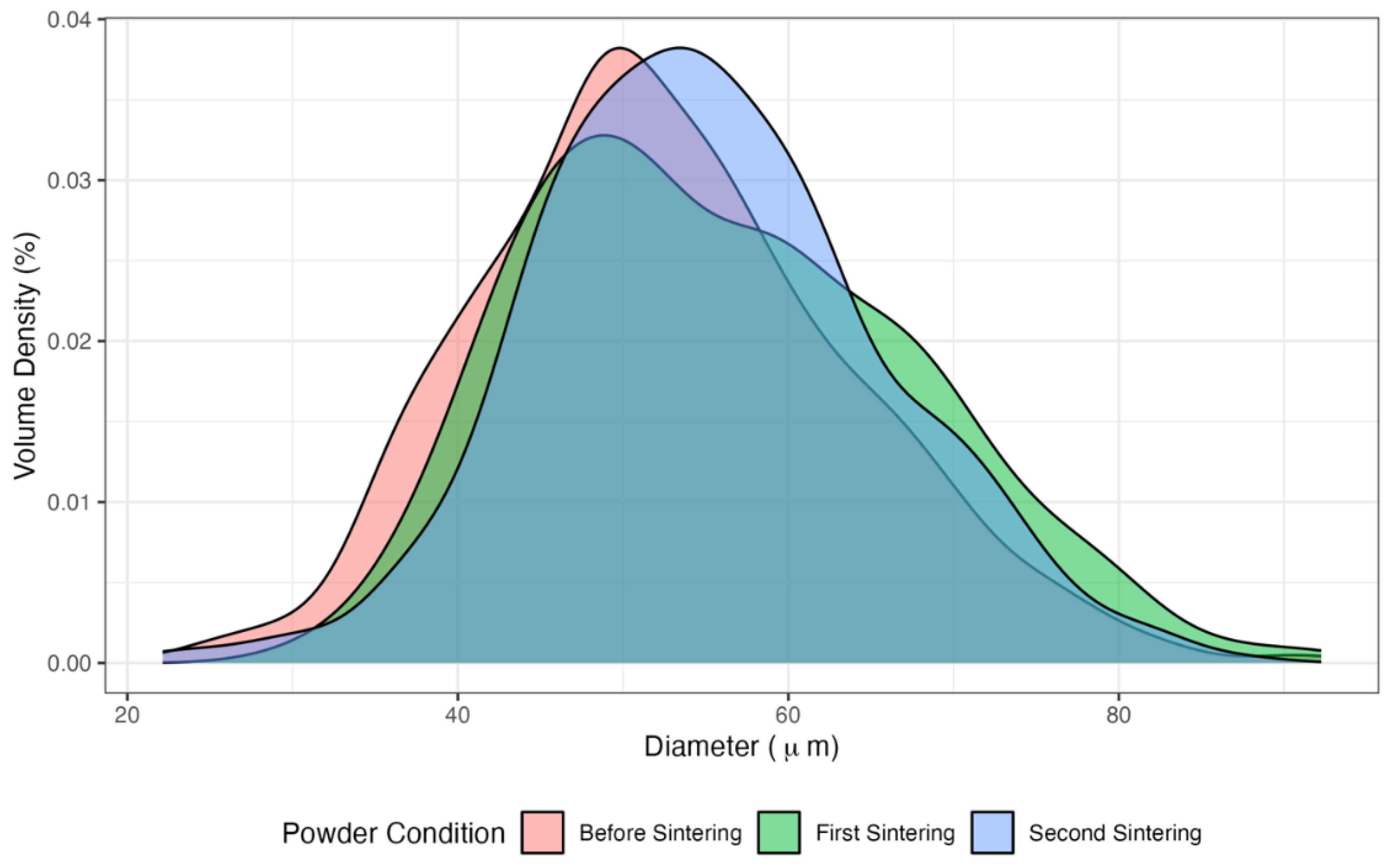

3.4). Size of the Particles

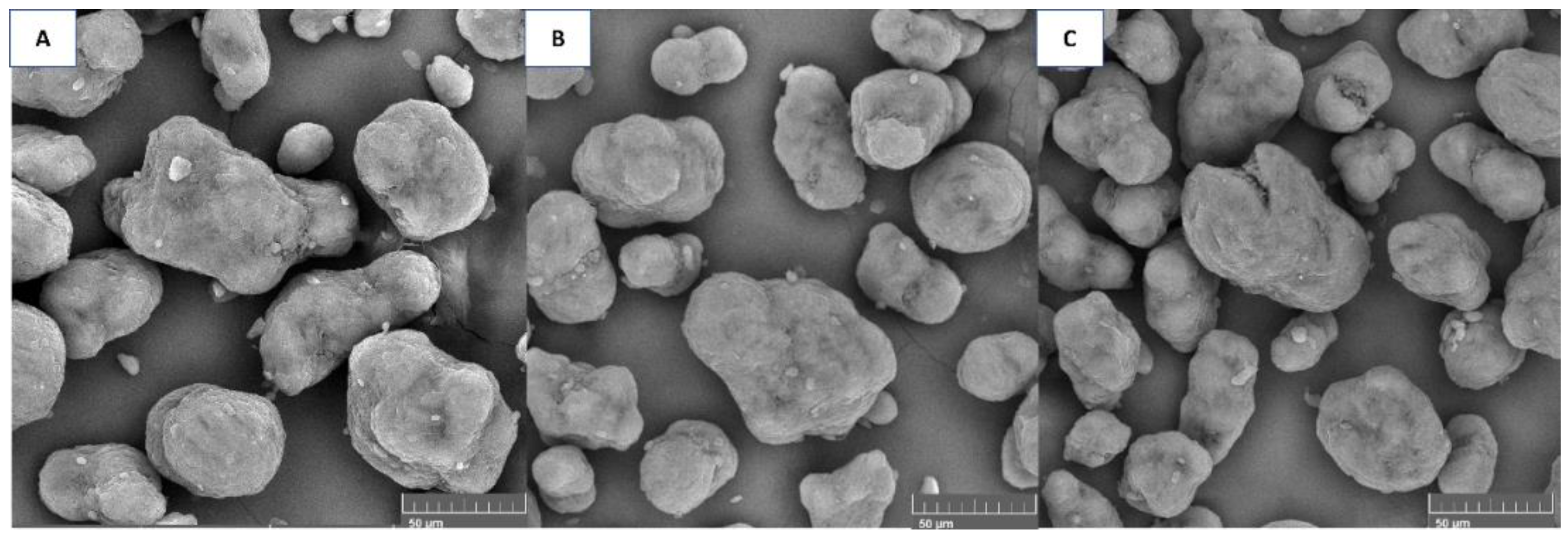

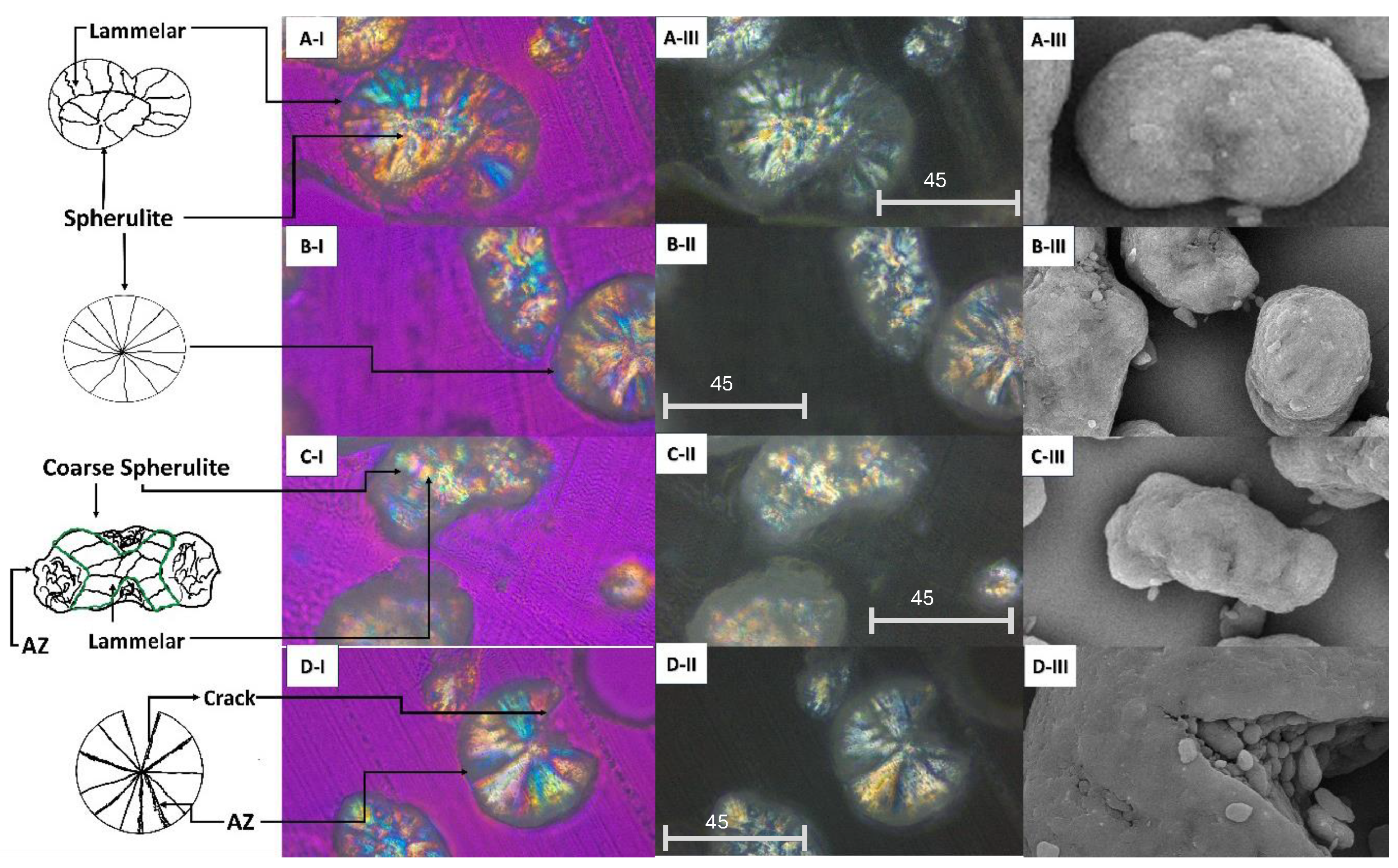

Figure 4 shows the particulates for each of the powder conditions. The more sintering cycles the powder underwent, the more irregularly shaped the particles tended to increase.

Figure 5 shows the particle diameter distribution for each of the PA12 powder conditions. The powder diameter size distribution had the highest particle density, corresponding to values close to 50 µm. In addition, a shoulder with a greater diameter (65 µm) was identified in all the cases.

According to

Table 3, the diameter of the particle increases by approximately 6.66% after one sintering cycle and 4.99% after two sintering cycles compared with that of the powder before the sintering cycles (

Table 1). A Kruskal‒Wallis nonparametric statistical test revealed statistically significant differences in particle size distribution (p=5.91 e-07). The Bonferroni post hoc comparison test revealed a significant difference in the particle diameter between the initial powder and the first sintering powder (p=3.9 e

-06) and between the initial powder and the second sintering powder (p=1.3 e

-04).

3.5). Morphology of the Particle Crystal

Figure 6 shows the crystal morphology as a function of the particle morphology.

Figure 6A shows a particle potato morphology with spherulite crystals in the center of greater diameter and preferential lamellar growth in the particle limits.

Figure 6B shows a spherical particle with strong spherulitic behavior. The black zones at the crystal boundaries could be the particle amorphous zones (AZs).

Figure 6C shows an irregular particle that presents a course spherulitic crystal. In addition, lamellar-type crystals were observed inside the spherulite particles. Finally, in

Figure 6D, a circular particle with a crack was observed. The fracture was intercrystalline, and spherulitic-lamellar crystals were present in the particle.

The particle size of the powder significantly changes with use conditions, as shown by comparing the pre- and postsintering states. This change is not just in size; the particle morphology also varies. Initially, circular particles are found in the virgin powder, but with recycling, more irregular and fractured shapes appear. These changes impact sample defects such as fusion issues, porosity, and orange peel texture [

25,

34].

This morphology change was associated with the crystal shape. The spherulitic crystals are generally symmetrical. In contrast, the potato morphology has a spherulite section where lamellar structures, resulting from the thermal process, follow. Finally, the irregular particles subjected to considerable thermal changes exhibited a thicker spherulitic behavior with lamellar subcrystals.

On the other hand, particle fracture is a phenomenon that is not clear today. Some theories associate this cracking with the thermal effect [

35] and mechanical damage [

36]. This research proposes a combination of both approaches. Although the fractured particle crystals are mainly spherulites, lamellar sections are also present. These thermal changes during sintering create crystalline gradients, increasing the resistance of some zones. When the blade sweeps the powder, stress on weaker areas can cause intercrystalline fractures at the crystal boundaries, which are considered amorphous.

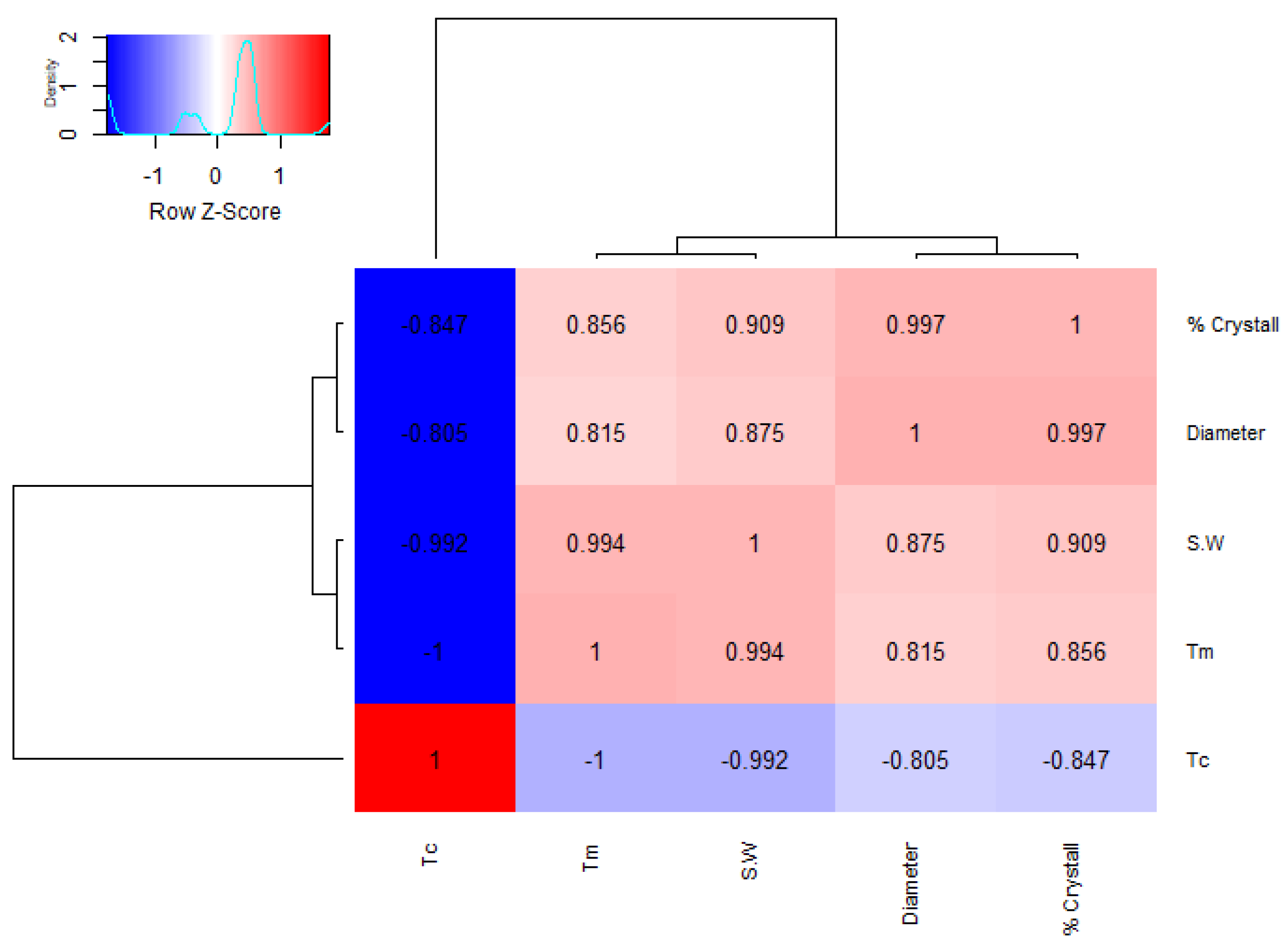

This study revealed strong statistical correlations between the thermal variables and the particle size and morphology.

Figure 7 shows that the properties present a proportional correlation, except for Tm-Tc, which offers an inverse relationship. This behavior should be studied as a function of the proximity of the laser in the sintering chamber to determine whether it is replicable or if the recycled powder has significant anisotropic conditions.

5. Conclusions

The PA12 powder was thoroughly analyzed in its initial blend and after two sintering cycles. The chemical composition remained unchanged, but the particle size and morphology significantly changed. A strong link was found between powder morphology and thermal properties, leading to a hypothesis explaining the cracking of the particles. The study highlighted how sintering affects the particle size and structure, which are key factors in sample defects. Future research will explore the relationship between the crystal shape and the laser distance to understand various behaviors in raw material studies.

References

- Garcia, E. Espejo, M. Velasco, and C. Narvaez, “Mechanical properties of polyamide 12 manufactured by means of SLS: Influence of wall thickness and build direction.,” Mater Res Express, 2023.

- K. D. Traxel, M. K. D. Traxel, M. Darin, K. Starkey, and A. Bandyopadhyay, “Model-driven directed-energy-deposition process workflow incorporating powder flowrate as key parameter,” Manufacturing Letters.

- R. Baserinia, K. R. Baserinia, K. Brockbank, and R. Dattani, “Correlating polyamide powder flowability to mechanical properties of parts fabricated by additive manufacturing,” Powder Technology, vol. 398, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Hejmady, L. C. A. P. Hejmady, L. C. A. van Breemen, D. Hermida-Merino, P. D. Anderson, and R. Cardinaels, “Laser sintering of PA12 particles studied by in situ optical, thermal and X-ray characterization,” Additive Manufacturing, vol. 52, no. January, p. 102624, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Kruth, X. P. Kruth, X. Wang, and T. Laoui, “Lasers and materials in selective laser sintering,” vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 357–371, 2006.

- S. Greiner, A. S. Greiner, A. Jaksch, S. Cholewa, and D. Drummer, “Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research Development of material-adapted processing strategies for laser sintering of polyamide 12,” Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, vol. 4, no. xxxx, 2021.

- O. Sivadas, I. O. Sivadas, I. Ashcroft, A. N. Khobystov, and R. D. Goodridge, “Laser sintering of polymer nanocomposites,” Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, vol. 4, no. xxxx, 2021.

- Y. Yap et al., “Review of selective laser melting: Materials and applications,” Applied Physics Reviews, vol. 2, no. 4, 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. Yusoff, D. T. W. Yusoff, D. T. Pham, and K. Dotchev, “Effect of Employing Different Grades of Recycled Polyamide 12 on the Surface Texture of Laser Sintered (Ls) Parts,” 2009.

- X. Jiang, W. X. Jiang, W. Shen, L. Jiang, and H. Qin, “Effects of Particle Size Distribution and Impact Speed on Printing Quality in Direct Energy Deposition,” Manuf Lett, vol. 33, pp. 521–526, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Starr, T. J. T. L. Starr, T. J. Gornet, and J. S. Usher, “The effect of process conditions on mechanical properties of laser-sintered nylon,” Rapid Prototyping Journal, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 418–423, 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. V. Salmoria, J. L. G. V. Salmoria, J. L. Leite, and R. A. Paggi, “The microstructural characterization of PA6/PA12 blend specimens fabricated by selective laser sintering,” Polymer Testing, vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 746–751, 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Hejmady, L. C. A. P. Hejmady, L. C. A. van Breemen, D. Hermida-Merino, P. D. Anderson, and R. Cardinaels, “Laser sintering of PA12 particles studied by in situ optical, thermal and X-ray characterization,” Addit Manuf, vol. 52, no. January, p. 102624, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Fotovvati and K. Chou, “Build surface study of single-layer raster scanning in selective laser melting: Surface roughness prediction using deep learning,” Manuf Lett, vol. 33, pp. 701–711, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Gawade, G. V. Gawade, G. Galkin, Y. B. Guo, and W. G. Guo, “Quantifying and modeling overheating using 3D pyrometry map in powder bed fusion,” Manufacturing Letters, vol. 33, pp. 880–892, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Yang, T. F. Yang, T. Jiang, G. Lalier, J. Bartolone, and X. Chen, “A process control and interlayer heating approach to reuse polyamide 12 powders and create parts with improved mechanical properties in selective laser sintering,” Journal of Manufacturing Processes, vol. 57, no. September, pp. 828–846, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Schmid and K. Wegener, “Additive Manufacturing: Polymers applicable for laser sintering (LS),” Procedia Engineering, vol. 149, no. June, pp. 457–464, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Martynková et al., “Polyamide 12 materials study of morpho-structural changes during laser sintering of 3d printing,” Polymers, vol. 13, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Launhardt, C. M. Launhardt, C. Fischer, and D. Drummer, “Research on the Influence of Geometry and Positioning on Laser Sintered Parts,” Applied Mechanics and Materials, vol. 805, pp. 105–114, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Pham, K. D. T. Pham, K. D. Dotchev, and W. A. Y. Yusoff, “Deterioration of polyamide powder properties in the laser sintering process,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, vol. 222, no. 11, pp. 2163–2176, 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. K.- Schuk, Lase Sintering with Plastics. HANSER, 2018.

- X. Jiang, W. X. Jiang, W. Shen, L. Jiang, and H. Qin, “Effects of Particle Size Distribution and Impact Speed on Printing Quality in Direct Energy Deposition,” Manufacturing Letters, vol. 33, pp. 521–526, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Majewski, H. C. E. Majewski, H. Zarringhalam, and N. Hopkinson, “Effects of degree of particle melt and crystallinity in SLS Nylon-12 parts,” 19th Annual International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, SFF 2008, pp. 45–54, 2008.

- W. Yang, F. W. Yang, F. Liu, J. Zhang, E. Zhang, X. Qiu, and X. Ji, “Influence of thermal treatment on the structure and mechanical properties of one aromatic BPDA-PDA polyimide fibers,” European Polymer Journal, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Dadbakhsh, L. S. Dadbakhsh, L. Verbelen, O. Verkinderen, D. Strobbe, P. Van Puyvelde, and J. P. Kruth, “Effect of PA12 powder reuse on coalescence behavior and microstructure of SLS parts,” European Polymer Journal, vol. 92, no. May, pp. 250–262, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Yang, N. Zobeiry, R. Mamidala, and X. Chen, “A review of aging, degradation, and reusability of PA12 powders in selective laser sintering additive manufacturing,” Materials Today, Communications, vol. 34, no. 22, p. 105279, 2023. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- El Magri, S. E. Bencaid, H. R. Vanaei, and S. Vaudreuil, “Effects of Laser Power and Hatch Orientation on Final Properties of PA12 Parts Produced by Selective Laser Sintering,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Martynková et al., “Polyamide 12 materials study of morpho-structural changes during laser sintering of 3d printing,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z. Li, and F. Zhu, “Effect of powder recycling on anisotropic tensile properties of selective laser sintered PA2200 polyamide,” Eur Polym J, vol. 141, no. July, p. 110093, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cai, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Comparative study on 3D printing of polyamide 12 by selective laser sintering and multi jet fusion,” J Mater Process Technol, vol. 288, no. 20, p. 116882, 2021. 20 August. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T. Jiang, and X. Chen, “Process control of surface quality and part microstructure in selective laser sintering involving highly degraded polyamide 12 materials,” no. November, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Dadbakhsh, L. S. Dadbakhsh, L. Verbelen, O. Verkinderen, D. Strobbe, P. Van Puyvelde, and J. P. Kruth, “Effect of PA12 powder reuse on coalescence behavior and microstructure of SLS parts,” Eur Polym J, vol. 92, no. May, pp. 250–262, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Yang, N. F. Yang, N. Zobeiry, R. Mamidala, and X. Chen, “A review of aging, degradation, and reusability of PA12 powders in selective laser sintering additive manufacturing,” Mater Today, Commun, vol. 34, no. 22, p. 105279, 2023. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Alo, I. O. Otunniyi, and D. Mauchline, “Aging due to successive reuse of polyamide 12 powder during laser sintering: extrinsic powder properties and quality of sintered parts,” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 370, p. 03011, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Verbelen, S. L. Verbelen, S. Dadbakhsh, M. Van Den Eynde, J. P. Kruth, B. Goderis, and P. Van Puyvelde, “Characterization of polyamide powders for determination of laser sintering processability,” European Polymer Journal, vol. 75, pp. 163–174, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Balemans, N. O. C. Balemans, N. O. Jaensson, M. A. Hulsen, and P. D. Anderson, “Temperature-dependent sintering of two viscous particles,” Additive Manufacturing, vol. 24, pp. 528–542, 2018. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Exothermic and endothermic DSC spectra of each powder sample before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 1.

Exothermic and endothermic DSC spectra of each powder sample before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 2.

DRX spectra of each powder sample before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 2.

DRX spectra of each powder sample before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 3.

DRX spectra of each powder sample before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 3.

DRX spectra of each powder sample before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the powder samples (A) before sintering, (B) after the first sintering cycle, and (C) after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the powder samples (A) before sintering, (B) after the first sintering cycle, and (C) after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 5.

Diameter distribution spectrum of each powder condition: before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 5.

Diameter distribution spectrum of each powder condition: before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle.

Figure 6.

Morphologies of the powder particles and their crystals. The (I) images were taken with polarized light with a quarter-wave retarder. Images (II) were taken only with polarized light, and (III) were SEM images. (A) Potato-type morphology, (B) circular-type morphology, (C) irregular-type morphology, (D) circular-particle-type crack.

Figure 6.

Morphologies of the powder particles and their crystals. The (I) images were taken with polarized light with a quarter-wave retarder. Images (II) were taken only with polarized light, and (III) were SEM images. (A) Potato-type morphology, (B) circular-type morphology, (C) irregular-type morphology, (D) circular-particle-type crack.

Figure 7.

Correlation between the thermic properties and diameter of the particle.

Figure 7.

Correlation between the thermic properties and diameter of the particle.

Table 1.

Crystallization temperature (Tc), melting temperature (Tm), crystallinity percentage (C.P.), sintering window (S.W.), and sintering window for each powder condition: before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle. The thermal properties of each powder condition were compared with the reference values.

Table 1.

Crystallization temperature (Tc), melting temperature (Tm), crystallinity percentage (C.P.), sintering window (S.W.), and sintering window for each powder condition: before sintering, after the first sintering cycle, and after the second sintering cycle. The thermal properties of each powder condition were compared with the reference values.

| Property |

Powder Condición |

Present study |

Dadbakhsh et al. [84] |

Cai et al. [82] |

Yang et al. [79] |

Chen et al. [83] |

Yang et al. [80] |

| Tc (°C) |

Before Sintering |

150.28 |

158.35 |

148.20 |

148.23 |

141.94 |

155.46 |

| First Sintering |

149.28 |

158.50 |

--- |

146.48 |

142.46 |

155.63 |

| Second Sintering |

148.84 |

156.75 |

|

147.02 |

142.78 |

155.67 |

| Tf (°C) |

Before Sintering |

182.58 |

184.05 |

188.90 |

186.38 |

182.53 |

180.15 |

| First Sintering |

185.49 |

185.15 |

---- |

188.18 |

182.53 |

180.13 |

| Second Sintering |

188.1 |

185.60 |

|

187.71 |

182.87 |

180.87 |

| C.P (%) |

Before Sintering |

59.93 |

55.2 ± 0.5 |

48.20 |

46.60 |

45.48 |

51.98 |

| First Sintering |

67.11 |

51.7 ± 0.1 |

--- |

50.02 |

44.92 |

51.17 |

| Second Sintering |

65.78 |

51.1 ± 1.8 |

|

49.35 |

40.17 |

47.26 |

| S.W (°C) |

Before Sintering |

18.44 |

17.80 |

--- |

25.70 |

29.92 |

--- |

| First Sintering |

18.75 |

17.30 |

|

27.70 |

30.31 |

--- |

| Second Sintering |

8.86 |

9.20 |

|

28.50 |

31.00 |

--- |

Table 2.

Comparison of the thermal properties of each powder condition with the literature values.

Table 2.

Comparison of the thermal properties of each powder condition with the literature values.

| Phase PA 12 |

Powder Condition |

Present study |

Yao et al.

[29] |

Cai et al.

[30] |

Yang et al.

[31] |

| Gamma (100) |

Before Sintering |

21.221 |

20.3 |

21.2 |

20.3 |

| First Sintering |

21.283 |

| Second Sintering |

21.393 |

| Alpha (010/110) |

Before Sintering |

22.253 |

23.2 |

22.1 |

23.9 |

| First Sintering |

22.274 |

| Second Sintering |

22.340 |

Table 3.

The particle diameter of the powder before and during the first and second sintering, with bibliography values.

Table 3.

The particle diameter of the powder before and during the first and second sintering, with bibliography values.

| Condition |

Present study (μm) |

Cai et al [30] |

Dadbakhsh et al. [32] |

Yang et al. [33] |

Jiang et al [10] |

Oluwaseun Aet al [34] |

| Before Sintering |

52.5 |

52.6 |

55-60 |

50-60 |

63 |

55.75 |

| First Sintering |

56.0 |

| Second Sintering |

55.1 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).