1. Introduction

Radar, particularly Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), is a tool that detects the distance, velocity, and altitude of objects by emitting electromagnetic waves, offering advantages over traditional optical sensors [

1,

2]. In recent years, with the advancement of SAR imaging technology and the improvement of image resolution, SAR target detection has become a hot topic, being part of SAR image post-processing. The goal of SAR target detection is to extract the orientation and location of targets from complex scenes quickly and effectively. This is crucial for Synthetic Aperture Radar automatic target recognition, where the accuracy of detection determines the success of subsequent tasks. This study is applicable to not only SAR target detection but also signal detection, aiming to enhance the ability to identify signals and targets in complex electromagnetic environments through deep learning techniques. Signal detection and recognition in dynamic electromagnetic environments is a critical field of study within electronic engineering, driven by the exponential growth of wireless technology usage across sectors. In a wireless monitoring system, signal detection is fundamental and important, serving as the basis for signal recognition, direction, and spectral analysis. However, the electromagnetic environment is complex, presenting significant challenges to detection. Signal detection can be divided into time and frequency domain detection. Additionally, deep learning has demonstrated superior performance in signal detection, enabling automatic feature extraction, improving detection accuracy. Wireless radio signal classification and modulation recognition are crucial issues in intelligent signal processing, holding significance for managing electromagnetic spectrum resources and ensuring reliability and security of communication systems. Researchers have proposed various methods for wireless radio signal identification to improve classification and modulation recognition accuracy.

In recent years, deep learning has been extensively applied across various industries, demonstrating superior performance relative to traditional methods. Many researchers globally have incorporated deep learning techniques into signal detection. O’Shea pioneered using convolutional neural networks (CNN) [

3] and deep neural networks (DNN) in radio communications for feature learning and signal recognition [

4]. Deep learning-based signal recognition methods typically utilize the spectro-temporal image obtained after short-time Fourier transformation (STFT) [

5] as input and output the spectro-temporal information. Prasad et al. [

5] used a reduced version of Faster-RCNN [

6] for radio signal detection to reduce network size. Another study [

7] applied YOLO object detectors to spectrum images to discover signals including Zigbee, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi from the Internet of Things (IoT). Rahman et al. proposes a Bi-LSTM-based channel estimation and signal detection method, demonstrating its effectiveness in RIS-supported multi-user SISO OFDM systems [

8]. Compared to traditional detection algorithms requiring manual feature extraction, deep learning methods leverage convolutional neural networks with superior feature extraction capabilities, enabling richer feature collection.

Despite the remarkable performance of Transformer-based models in the field of image processing and the potential they exhibit in SAR target detection and electromagnetic signal detection, they have not yet incorporated prior knowledge from signal processing. In this study, we introduce the latest deep learning models to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of signal modulation identification. These new models not only demonstrate superior performance in image processing and object recognition, particularly outperforming traditional methods in terms of processing speed and accuracy, but also overcome the high misclassification rates and slow response times of traditional models in specific scenarios through innovative algorithm optimization. Our key innovations are as follows.

Half-Window Filtering Technology: By proposing half-window filter(HWF), which leverages prior knowledge from SAR signal processing, the feature extraction process is enhanced, significantly improving the recognition performance for targets of different scales. While Transformer-based models have demonstrated strong performance in image processing, SAR target detection and electromagnetic signal detection, they have not yet fully integrated SAR signal processing priors, which this approach addresses.

Auxiliary Feature Extractors: During training, auxiliary feature extractors are introduced to provide additional supervision signals, enhancing the model’s encoding and decoding capabilities. Traditional object detection algorithms have shown poor performance on SAR target detection tasks. The introduction of auxiliary feature extractors significantly improves this by providing more robust feature learning and enhancing overall recognition accuracy.

Multi-Scale Adapter: The Multi-Scale Adapter dynamically constructs feature pyramids through upsampling and downsampling operations, enhancing multi-scale feature alignment and significantly improving detection accuracy for targets of varying sizes and scales.

3. Method

As shown in

Figure 1, our model processes input images to produce final outputs. The image is initially processed by the main network and Transformer encoder, generating feature maps. These feature maps are then processed by the multi-scale adapter to create multi-scale features. Further processing by auxiliary feature extractors generates classification and regression predictions. By comparing these predictions with real labels, we calculate classification and regression losses. The total loss optimizes model parameters, enhancing feature learning and improving performance.

3.1. Half-Window Filter

The half-window filter(HWF) is designed to reduce the variational energy while maintaining image edges. Its basic concept is to use the pixel local solutions of the regularization operator as the projection operation, and to reduce the regularization energy by approximating the image as a constant, minimum or expandable surface within a local window.

Given the input image

I, after passing through the HWF and CNN, we obtain the feature map

F.

As shown in Equation (

1), after passing the input image

I through the HWF and CNN, we obtain the feature map

F.

The HWF works through two main steps. First, in the neighborhood of each pixel, the image is approximated locally as a constant, minimal surface, or developable surface through local regression. Second, among all possible local approximations, the one that results in the smallest change in the central pixel intensity is selected, thereby minimizing the increase in data fitting energy.

The following equations describe the implementation of the projection operator used in the HWF. Let represent the value of the input function at the pixel (or index) . The surrounding values can be defined as follows: , , , , , , , , .

The projection operator

is applied as follows.

Where , , , and represent the computed differences based on the surrounding values of , and is the minimum absolute difference. The final result, , is obtained by adding to the original value , which adjusts the value based on the neighboring pixel differences.

In our model, the HWF serves as a layer within the CNN and is trained via backpropagation using standard error. This method harnesses deep learning techniques for image processing and feature extraction while significantly reducing variational energy, thereby enhancing model performance and training efficiency. This approach effectively supplants traditional convolution kernels, utilizing deep learning methodologies to achieve superior image processing and feature extraction.

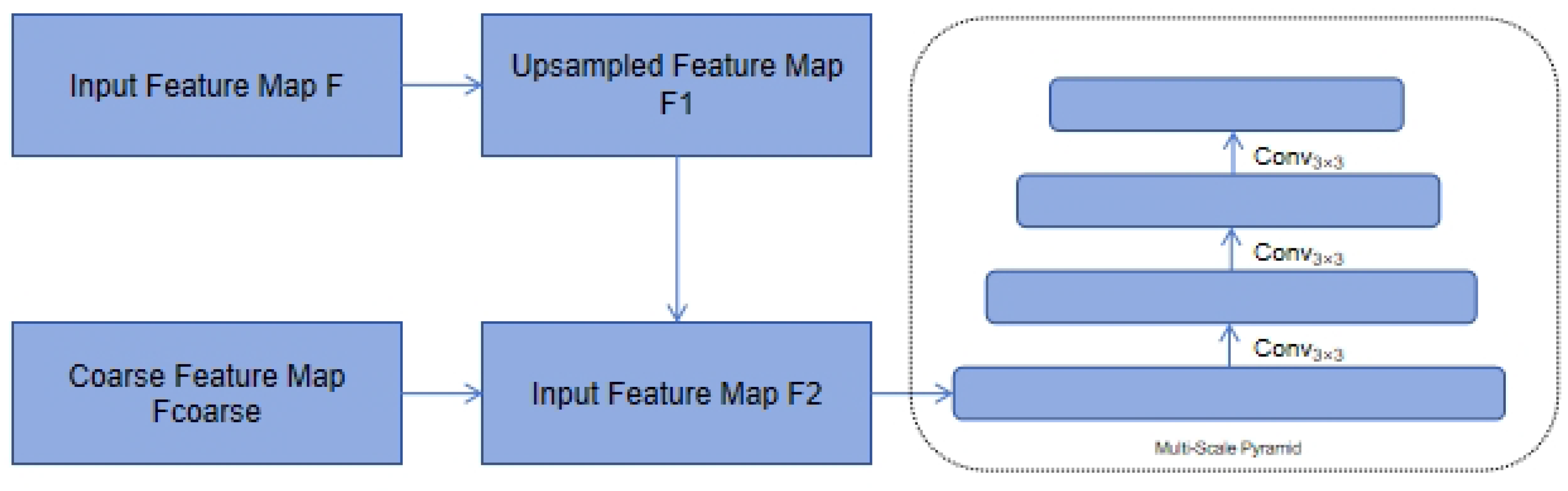

3.2. Multi-Scale Adapter

In object detection tasks, the Multi-Scale Adapter, a specialized tool, is strategically utilized to transform single-scale or multi-scale features. These features are meticulously processed and output by the encoder into a multi-scale feature pyramid. The adapter’s functionality significantly enhances the ability of auxiliary feature extractors to meet their specific needs. This process results in a more effective and efficient object detection system.

For the single-scale encoder output, the feature pyramid is first constructed through bilinear interpolation and convolution operations. Let the feature map output by the encoder be F. We construct the feature pyramid through the following steps.

In the process of upsampling the feature map, bilinear interpolation is applied. For each feature map

, the upsampling operation can be expressed as Equation (

8).

Figure 2.

Multi-Scale Adapter Workflow for Feature Pyramid Construction.

Figure 2.

Multi-Scale Adapter Workflow for Feature Pyramid Construction.

After upsampling, the feature map is further processed with a

convolution. The convolution operation is defined as Equation (

9).

As shown in Equation (

8), the feature map is upsampled using bilinear interpolation. Then, as described in Equation (

9), the upsampled feature map undergoes a convolution operation.

For the multi-scale encoder, we only downsample the coarsest feature in the multi-scale encoder features to build the feature pyramid. For the multi-scale encoder output, assuming the coarsest feature map is , we construct the feature pyramid through downsampling operations:

Start with the coarsest feature map

. The initial feature map is given.

Next, apply a

convolution with stride 2 to the feature map to downsample it. This downsampling operation can be expressed.

Repeat this downsampling step as necessary to construct the feature pyramid.

As shown in Equation (

10), we start with the coarsest feature map

. Then, as described in Equation (

11), a downsampling operation is applied to the feature map.

The Multi-Scale Adapter is crucial for object detection tasks, as it transforms single-scale or multi-scale features into a multi-scale feature pyramid. This enhances the ability of auxiliary feature extractors to meet their needs, improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the object detection system. The adapter achieves this through bilinear interpolation and convolution operations or downsampling the coarsest feature map, constructing multi-level feature representations. In summary, the Multi-Scale Adapter greatly facilitates performance optimization and training convergence of object detection models.

3.3. Auxiliary Feature Extractor

In modern object detection frameworks, feature extraction and accurate prediction play crucial roles in achieving high performance. auxiliary feature extractors are introduced to provide additional supervision signals during the training phase, thereby enhancing the learning of features. This section explains the process and significance of using auxiliary feature extractors in our model.

Given the input image

I, after passing through the Backbone (including the HWF and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)) and the Transformer encoder, we obtain the feature map

F.

Multi-scale adapter processes the feature map

F, generating multi-scale features

.

Each auxiliary feature extractor processes the multi-scale features, generating classification predictions

and regression predictions

.

Where k denotes the k-th auxiliary feature extractor.

The use of auxiliary feature extractors enhances feature learning by providing additional supervision signals during training. Unlike traditional data augmentation, which increases data diversity through geometric and color transformations, auxiliary feature extractors generate extra labels and features to improve the model’s encoding and decoding abilities. This method enhances feature-level diversity and information content, leading to improved model performance and generalization.

We use three different auxiliary feature extractors in our experiments:ATSS, YOLOv3 and Faster-RCNN. ATSS (Adaptive Training Sample Selection) [

34] bridges the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection methods, offering adaptability and robustness in various scenarios. YOLOv3 [

35] is a single-stage detector that predicts multiple object bounding boxes and categories in a single forward pass, excelling in computational efficiency. Faster-RCNN [

36] is a region-based convolutional neural network that combines a Region Proposal Network (RPN) with a Fast R-CNN detector. It provides higher detection accuracy but requires more computational resources.

3.4. Loss Function and Optimization

In deep learning, the loss function and optimization are central to the training process. The loss function quantifies the discrepancy between the model’s predictions and the ground truth, while optimization methods are used to adjust the model parameters to minimize this discrepancy. In this section, we discuss the loss functions used in our model, the total loss function, and the optimization process.

The loss function in our model consists of two main components: classification loss and regression loss. These losses are calculated separately for each auxiliary feature extractor. The classification loss measures the difference between the predicted class probabilities and the true class labels, while the regression loss measures the difference between the predicted bounding box coordinates and the ground-truth coordinates.

In object detection, the classification loss

measures the difference between the predicted class and the ground truth class label, typically calculated using cross-entropy loss. The formula is as Equation (

15).

where

is the predicted class output from the

k-th auxiliary feature extractor, and

is the ground truth class label.

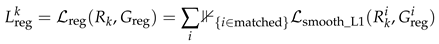

The regression loss

measures the difference between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth bounding box, typically computed using smooth L1 loss. The formula is as Equation (16).

where

is the regression output (e.g., bounding box coordinates) from the

k-th auxiliary feature extractor,

is the ground truth bounding box coordinates, and

is an indicator function that checks whether the predicted and ground truth boxes are matched.

The classification loss

for the

k-th auxiliary feature extractor is calculated as Equation (

17).

Similarly, the regression loss

is computed as Equation (

18).

Where and are the predicted class and bounding box coordinates, and and are the ground truth class labels and bounding box coordinates.

The total loss function

is the weighted sum of the classification and regression losses from all auxiliary feature extractors. It is formulated as Equation (

19).

Here, and are the weighting coefficients, which balance the contributions of the classification and regression losses.

To minimize the total loss function , we use an optimization algorithm to update the model parameters during training. We employ the Adam optimizer, which combines the benefits of both adaptive learning rates and momentum, making it effective for training deep networks. The optimization process aims to minimize the total loss function by adjusting the model’s parameters iteratively.

The design of the loss function significantly impacts the optimization process. By balancing the classification and regression losses appropriately, we ensure that the model is not biased toward one task over the other. The loss function guides the optimization process toward finding the best model parameters that minimize the prediction errors for both classification and bounding box regression tasks. Furthermore, the auxiliary feature extractors help regularize the model by providing additional supervision signals, which enhances the optimization process and prevents overfitting.

In summary, the loss function and optimization play a crucial role in training our model, ensuring that it effectively learns to perform both classification and regression tasks while generalizing well to unseen data.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Details

In this study, we utilized the HRSiD (High-resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar Ship Detection) [

37] dataset, which is specifically designed for ship detection tasks using high-resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) images. The HRSiD dataset contains a large number of high-resolution SAR images captured under various environmental conditions, aimed at evaluating the performance of ship detection algorithms in complex backgrounds. The dataset includes data from multiple voyages, covering a range of weather conditions, sea states, and different types of ships. Each image is meticulously annotated with detailed information, such as ship categories and locations, providing comprehensive support for model training and performance evaluation. In this research, we used the HRSiD dataset for both model training and testing, with the goal of validating the effectiveness and robustness of our proposed method in ship detection tasks.

To better illustrate the characteristics of the HRSiD dataset, we present two example images.

Figure 3a shows a high-resolution SAR image of a ship under calm sea conditions, while

Figure 3b depicts a ship in a more complex maritime environment with rough sea states. These images highlight the challenges of ship detection in SAR imagery, including varying ship types, sea states, and environmental conditions.

Our experiments also use two-dimensional spectrograms generated from radio waves through a Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). These serve as primary input for our model, with the horizontal axis representing signal frequency and the vertical axis denoting time. The signal is visually depicted as a rectangular block within the spectrogram for clarity. We also utilize the Spectral color mapping scheme to enhance diagram efficacy. Specific parameter settings tailored for our dataset are as shown in

Table 1.

In our experiments, the 10 modulation modes are considered separately. The signal can be divided into two types: unaliased and aliased, as shown in “

Figure 4a”.“

Figure 4a” is a simple pattern of radio with no time and frequency aliasing, while “

Figure 4b” is a complex pattern with time or frequency aliasing.

We analyzed signals with random durations determined by the DataBitLength parameter, which was varied between minimum and maximum bit lengths for each modulation type. The minimum bit length ranged from 20-200, and the maximum bit length ranged from 400-3000. Storage duration was calculated based on the number of samples and sampling rate to allow for visualization as 512x512 spectrograms.

We conducted extensive trials to compare our model with other successful detectors. All experiments were carried out on a GeForce RTX 3070 GPU. We trained all detectors using the SGD optimizer, with a momentum of 0.937 and a weight decay of 0.00001.

In our experiments, we adopted ATSS [

34] as auxiliary feature extractors. We set the number of learnable object queries to 300 and the hyperparameters

to the default values of

. Here,

and

control the loss function.

The selection of the appropriate auxiliary feature extractor is crucial for achieving both high detection accuracy and computational efficiency. While Faster R-CNN offers higher accuracy, it is more computationally demanding. In contrast, single-stage detectors like YOLO and SSD are typically more efficient, making them ideal for real-time detection tasks. The choice of auxiliary feature extractor should also take into account specific application scenarios and dataset characteristics to optimize model performance and applicability.

4.2. Comparative Experiments

Under the same experimental configuration, we compared our model with other DETR-based models.All results are reproduced using mmdetection.

Table 2 presents the results of the comparative experiments conducted on the HRSID dataset, evaluating different methods using mAP

50 and mAP (mAP

50:95). The results demonstrate that our proposed method achieves a mAP of

0.682, surpassing all other methods, including the previous state-of-the-art CS

3Net, which achieved a mAP of 0.66. Additionally, our method achieves competitive performance in terms of mAP

50, reaching

0.902, which is comparable to CS

3Net (0.912) and Yue et al. (0.911).

Compared to lightweight models such as YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-tiny, and YOLOv8n, our method not only outperforms them in mAP but also achieves a favorable trade-off between accuracy and model complexity. Furthermore, while the CS3Net and Yue et al. methods achieve high mAP50 scores, they fall short in terms of mAP, indicating the robustness of our method across varying IoU thresholds. These results highlight the superior performance of our approach in detecting small and challenging objects in the HRSID dataset.

The comparative experimental results, as presented in

Table 3, highlight the effectiveness of the proposed Refined Deformable-DETR model in comparison to other DETR-based methods and popular object detection frameworks. The Refined Deformable-DETR achieves the highest performance across all evaluation metrics, with the best results obtained after 36 epochs of training. Specifically, it achieves an

of 0.540, an

of 0.804, and an

of 0.586, which significantly surpasses the results of the baseline Deformable-DETR and other DETR variants.

Compared to the original Deformable-DETR, the refined version demonstrates substantial improvements across all metrics, with an increase of 0.283 in , 0.399 in , and 0.313 in . Furthermore, the proposed model excels in detecting small and medium objects, achieving and , indicating its robustness across different object scales. These improvements are attributed to the introduction of the and the refined architecture, which enhance the feature representation and learning capacity of the model.

Overall, the Refined Deformable-DETR achieves state-of-the-art performance, with notable improvements in accuracy, scalability, and training efficiency, validating its effectiveness in object detection tasks under challenging conditions.

To further analyze the model’s performance across different modulation schemes, we present the confusion matrix in

Figure 5. From the confusion matrix, we observe that the model performs exceptionally well on certain classes, such as GMSK and 64QAM, with classification accuracies of 66% and 89%, respectively. This indicates that these modulation schemes have distinct characteristics, making them easier for the model to classify correctly.

The confusion matrix analysis reveals the model’s performance across different modulation schemes. Although the model performs well on certain signals, it struggles to distinguish between similar modulation types. Future work could introduce more advanced feature extractors or utilize higher-level supervisory signals to improve classification performance.

4.3. Ablation Study

In this section, we compared the impact of different auxiliary feature extractors on model performance. We selected YOLOv3 [

35], Faster-RCNN [

36] and ATSS [

34] as auxiliary feature extractors, and conducted experiments under various configurations.

The results of the ablation study on the HRSID dataset are shown in

Table 4. When HWF is enabled, YOLOv3 outperforms the other two extractors with an AP of 0.682 and AP

50 of 0.902. Faster-RCNN shows slightly lower performance, with an AP of 0.602 and AP

50 of 0.858. ATSS achieves an AP of 0.677 and an AP

50 of 0.882. All extractors show a decrease in performance when HWF is disabled, with YOLOv3 maintaining the best performance in both AP and AP

50 under the non-HWF configuration.

Table 5 presents the results of the ablation study on the Spectrograms dataset. YOLOv3, with HWF enabled, achieves an AP of 0.540 and an AP

50 of 0.804. The performance decreases slightly when HWF is disabled. Faster-RCNN and ATSS also demonstrate similar trends, with ATSS yielding the best performance among the three, reaching an AP of 0.533 and an AP

50 of 0.771 when HWF is enabled. For both datasets, disabling HWF leads to a reduction in performance, although the degree of the drop varies between extractors and datasets.

The results from both datasets suggest that the HWF module is particularly effective in scenarios requiring high-precision detections. On the HRSID dataset, which contains diverse targets including medium and large objects, the module provides significant benefits in both AP and AP50. On the Spectrograms dataset, which involves more complex signal patterns, the module still contributes to performance improvements, albeit to a lesser extent.

In conclusion, this ablation study highlights the positive impact of the HWF module on detection performance, demonstrating its ability to enhance feature extraction and improve recognition accuracy across different datasets. While the gains are more prominent on the HRSID dataset, the consistent improvements across datasets underline the utility of the HWF module as a general enhancement for detection tasks.

is an indicator function that checks whether the predicted and ground truth boxes are matched.

is an indicator function that checks whether the predicted and ground truth boxes are matched.