1. Introduction

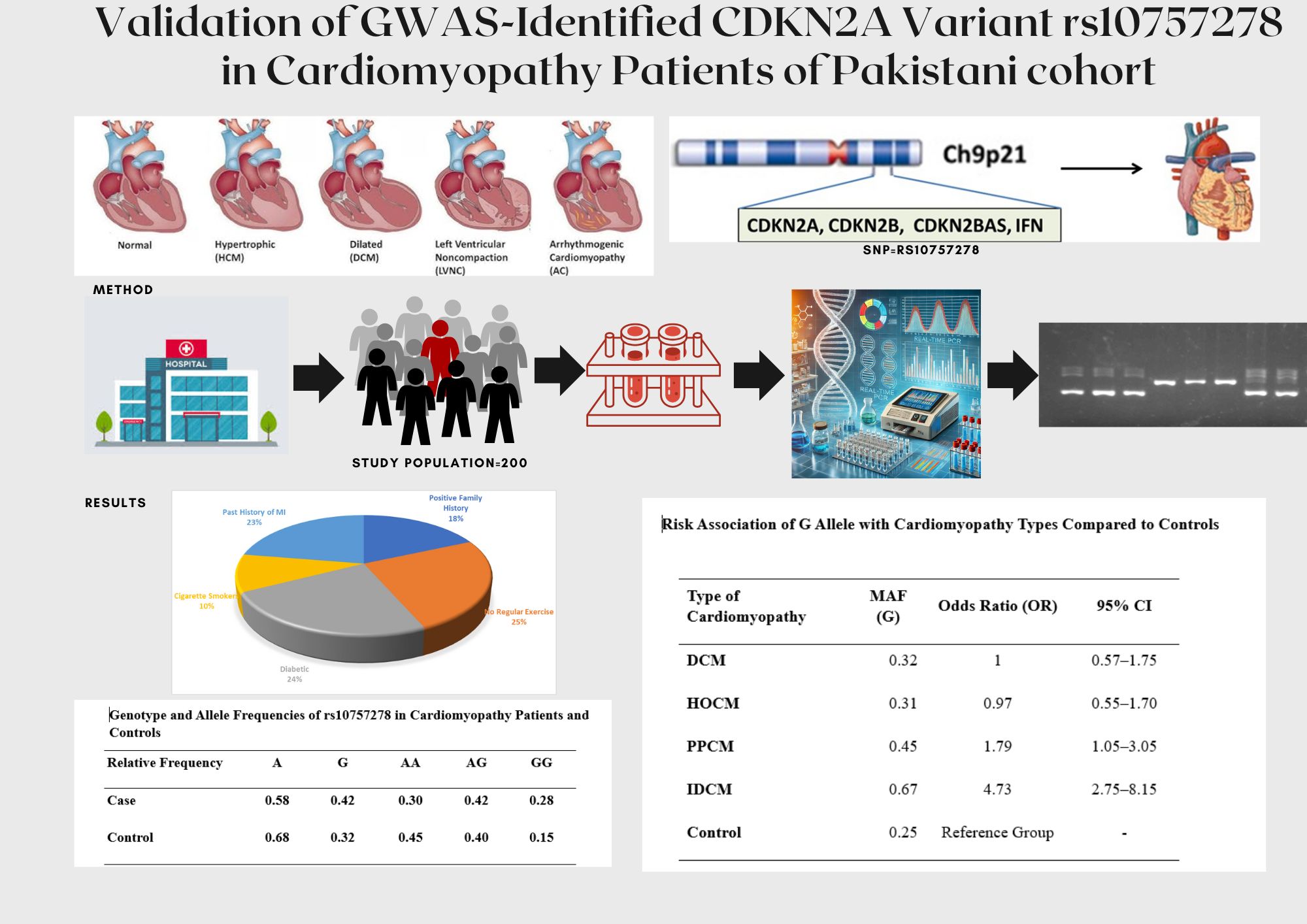

Cardiomyopathy refers to a diverse group of heart muscle disorders that impair the heart's ability to pump blood effectively, leading to symptoms ranging from arrhythmias to heart failure [

1]. World Health Organization (WHO) and European Society of Cardiology; categorized cardiomyopathy into dilated cardiac myopathies (DCM), hypertrophic cardiac myopathies (HCM), restrictive cardiac myopathies (RCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular (ARVC), and non-classifiable cardiomyopathies [

1,

2,

3]. This disease occurs due to primary and enigmatic myocardium disorder or secondary due to various disorders like myocardial infarction (MI), hypertension, diabetes, valvular heart disease, pregnancy complication etc. [

2,

3].

Cardiomyopathies was first documented in early 1891 by German scientist Krehl. It encompasses a diverse spectrum of disorders, frequently culminating in progressive heart failure and posing substantial risks of morbidity and mortality [

2,

4]. The causes of cardiomyopathy in adults are multifaceted with variety of risk factors. The main contributing factors are family history, genetics, coronary artery disease (CAD), physical stress, nutritional deficiencies, obesity, viral infections such as Chagas disease, hypertension exposure to toxins (such as ethanol), smoking, heart attack, complications of pregnancy and endomyocardial fibrosis. These factors contribute collectively to the higher frequencies of cardiac myopathies especially dilated cardiomyopathy in developing countries [

4,

5].

Worldwide prevalence of cardiomyopathy is estimated at 6.0 million, although actual cases may be higher due to delayed diagnosis from asymptomatic progression and non-reporting in underdeveloped countries. Cardiomyopathy significantly contributes to cardiovascular diseases, which account for 18 million deaths annually. In 2021, 2.26 million cases of DCM were reported, predominantly in the USA, France, Italy, and the UK, with an annual increase of approximately 2% [

4,

6].

Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy (IDCM) and Peripartum Cardiomyopathy (PPCM), subclasses of DCM, are leading causes of heart failure with high morbidity and mortality, despite advancements in CAD management. IDCM typically arises from worsening CAD, causing impaired left ventricular systolic function with an ejection fraction below 40% [

7]. Prior myocardial infarctions (MI) and ventricular remodeling lead to irreversible myocardial tissue loss. Even with coronary revascularization, contractile function does not recover as the infarcted tissue is non-viable, emphasizing the need for early intervention [

7,

8]. PPCM is caused by myocardial dysfunction that occurs during pregnancy or the postpartum period, often in the absence of pre-existing heart disease [

9].

A thorough assessment of clinical symptoms and diagnostic procedures, such as chest X-ray, Transthoracic echocardiography, cardiac MRI, CT, ECG, and echocardiography, is essential for the diagnosis of cardiomyopathies. While genetic profiling and blood tests can improve accuracy by ruling out other causes of heart failure, echocardiography remains a fundamental procedure for diagnosis [

7,

8,

9].

Genetic mutations play a crucial role in the development of various types of cardiac myopathies by altering the structure and function of proteins critical for cellular activities. Significant strides have been achieved in identifying the genetic underpinnings of cardiomyopathy throughout the last 25 years. More than 100 genes have been linked to various cardiomyopathies to date, opening the door for better patient outcomes, individualized treatment plans, and improved diagnostics [

10,

11].

The chromosomal region 9p21.3 has been strongly associated with MI and CAD in numerous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and case-control analyses [

12]. This locus is also implicated in other conditions, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, aortic aneurysm, cancer, and peripheral artery disease. This region contains the rs10757278 SNP, which is next to the CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes, which play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis, despite being outside of protein-coding sequences. Numerous GWAS have examined the rs10757278 polymorphism in relation to CAD and MI, and they have a strong correlation [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Although the association between rs10757278 and CAD is well established, its role in cardiomyopathy, particularly in IDCM, remains underexplored.

Given the established association between rs10757278 and cardiovascular disease like CAD & MI, we hypothesize that this SNP may also contribute to the development of IDCM by influencing left ventricular function and promoting myocardial remodeling. The present study aims to investigate the genetic association of rs10757278 SNP with cardiomyopathy subtypes, focusing on IDCM, in a cohort from the Pakistani population. Our findings could offer new insights into the genetic underpinnings of cardiomyopathy and pave the way for genetic risk profiling in clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The study was conducted as case control study, at the Rawalpindi Institute of Cardiology (RIC) and, PMAS Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi. It included 200 subjects (100 cases and 100 controls), recruited from RIC. This study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Rawalpindi Institute of Cardiology (RIC) and, Pir Mehr Ali Shah, Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi approved the study. All procedures were in compliance with Helsinki declaration. The data and blood samples were collected according to the information on the questionnaire, designed for the study. All participants provided written informed consent prior to sample collection.

2.2. Study Population

The CAD patients with various types of cardiomyopathy subtypes, including DCM, HOCM, IDCM and PPCM were recruited from outpatient and inpatient department of RIC based on clinical evaluations. Participants aged 18-75 years were included in either the cardiomyopathy/disease group (DCM, HOCM, PPCM, and IDCM) or the control/normal group. All of the CAD subjects were diagnosed cases based on comprehensive bio-data, ECG, echocardiography, and relevant laboratory parameters). Echocardiography was conducted to assess cardiac structure and function parameters, as aortic root diameter (ARD), left atrium diameter (LAD), septal thickness (ST), systolic diameter, diastolic diameter and ejection fraction (EF) were evaluated by an expert cardiologist of RIC. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels were measured using the fully automated Atellica Solution integrated chemistry analyzer by Siemen.

Those patients were excluded who had valvular heart disease, or long-term systemic conditions such as cancer or autoimmune diseases. Control group consisted of healthy adults without cardiovascular disease or any other systemic health conditions matched for age and gender. With the challenges in obtaining patients with particular subtypes of cardiomyopathy (such as PPCM and IDCM), and the reported stronger association of rs10757278 SNP with CAD and MI in many GWAS (12-15), this sample size is expected to provide sufficient statistical power to detect a meaningful genetic association. Moreover, power analysis also confirmed that this sample size would be adequate to detect an effect size of X with 80% power at a significance level of 0.05.

2.3. Study Groups & Sub-Types

CAD subjects were further categorized into different groups according to type of cardiomyopathy. DCM group consist of patients with clinical signs of heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%, without other identifiable causes. HOCM patients with unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy (>15 mm) and no systemic causes were eligible. PPCM included women with heart failure during the last month of pregnancy or within five months postpartum, with no prior heart disease. For IDCM, patients with a history of myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease and an LVEF <40% were included.

2.4. Genotyping

DNA was extracted from the blood samples using the modified Sambrook protocol [

16] ensuring high purity and yield. The DNA samples were quantified by the nanodrop (Thermo Scientific™ NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c). Primers for tetra arms PCR of SNP rs10757278 were designed using online SOTON tetra arms PCR primer designing Software (

Table 1). Applied Biosystem’s online Tm calculator was used to verify primers melting temperature and estimation of PCR annealing temperature. Genotyping was done by T-Arms PCR on (T100 Thermal Cycler bi Biorad). The amplified DNA products were analyzed on 2% gel, viewed by using Gel documentation system (Alpha Innotech USA). Fragment size of 263bp corresponds to AA homozygous, and 338bp corresponds to GG homozygous.

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed using R software version 4.4.2. Demographic and biochemical parameters like age, sex, BMI, diabetic status, smoking pattern were analyzed using descriptive analyses. The differences in the range of biochemical parameters among different cardiomyopathies were analyzed using chi.square analysis. Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed using goodness of fit. Risk allele frequencies were calculated and, Chi square test was applied to compare gene/allele frequencies between cases and controls. Odds ratio (OR) was calculated to identify the disease risk by specific genotypes. Logistic regression model was applied for risk prediction of cardiomyopathies based on genotype and relative allele frequencies, and to identify association between the risk allele frequency and cardiomyopathies.

Functional analysis of the variant was done on GTEx and RegulomeDB, further the phenome wide association of the SNP was identified by assessment of the associated phenotype GWASs across UK Biobank.

3. Results

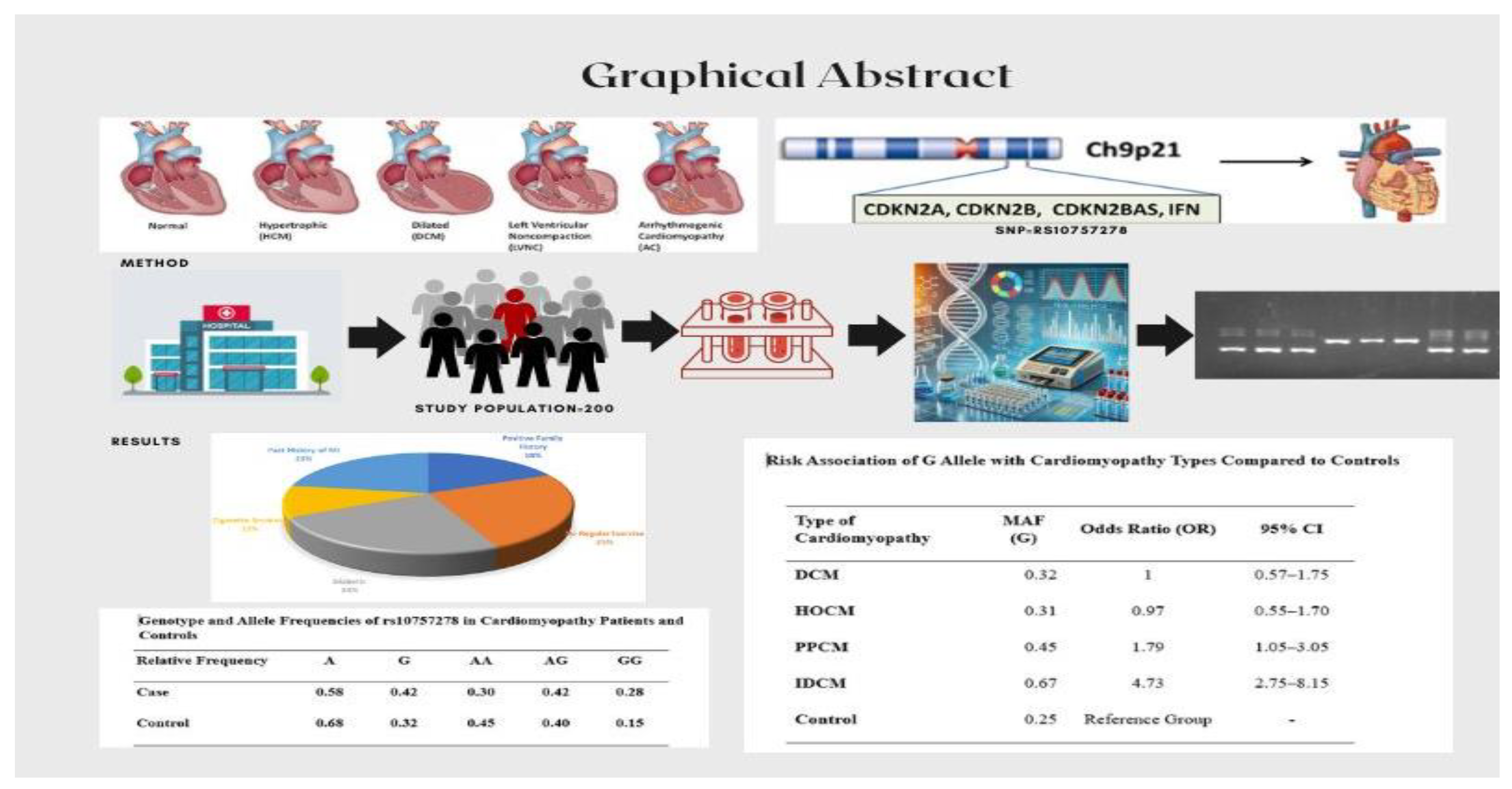

3.1. Demographic and Biochemical Findings of Studied Participants

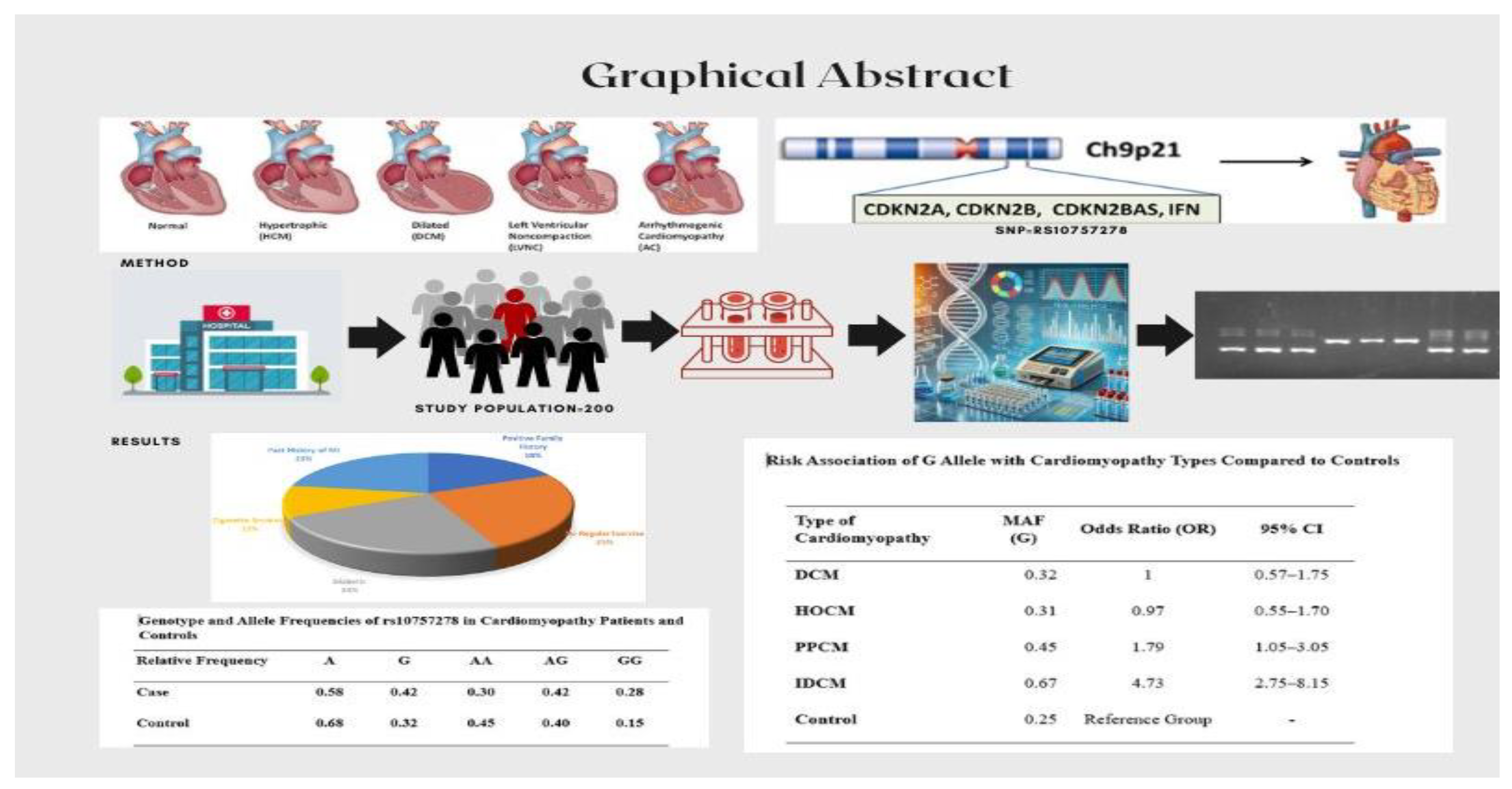

Studied population (n=200), had 55.4% (n=111) male and 44.6% (n=89) females indicating the higher proportion of males (57.0%) in diseased group. Comparison of mean values for clinical and biochemical parameters compared between patients and healthy individuals identified age (47 ± 15.7 years), BMI (24.5 ± 3.9 kg/m²), BNP (1255.0 ± 942.0 pg/mL), ARD (28.3 ± 4.1 mm), LAD (39.2 ± 6.7 mm), ST (11.2 ± 4.7 mm), systolic diameter (47.2 ± 12.3 mm), diastolic diameter (57.6 ± 10.4 mm), and EF (29.4 ± 13.9%). The control group demonstrated mean values of 40.0 ± 12.0 years, 24.0 ± 3.2 kg/m², 97.8 ± 43.6 pg/mL, 25.0 ± 3.0 mm, 38.0 ± 4.5 mm, 9.5 ± 1.5 mm, 41.0 ± 5.0 mm, 49.0 ± 5.0 mm, and 55.0 ± 5.0%, respectively. Significant differences (p=<0.05) have been observed in various variables (Age, BNP, ARD, systolic diameter, diastolic diameter, and EF (

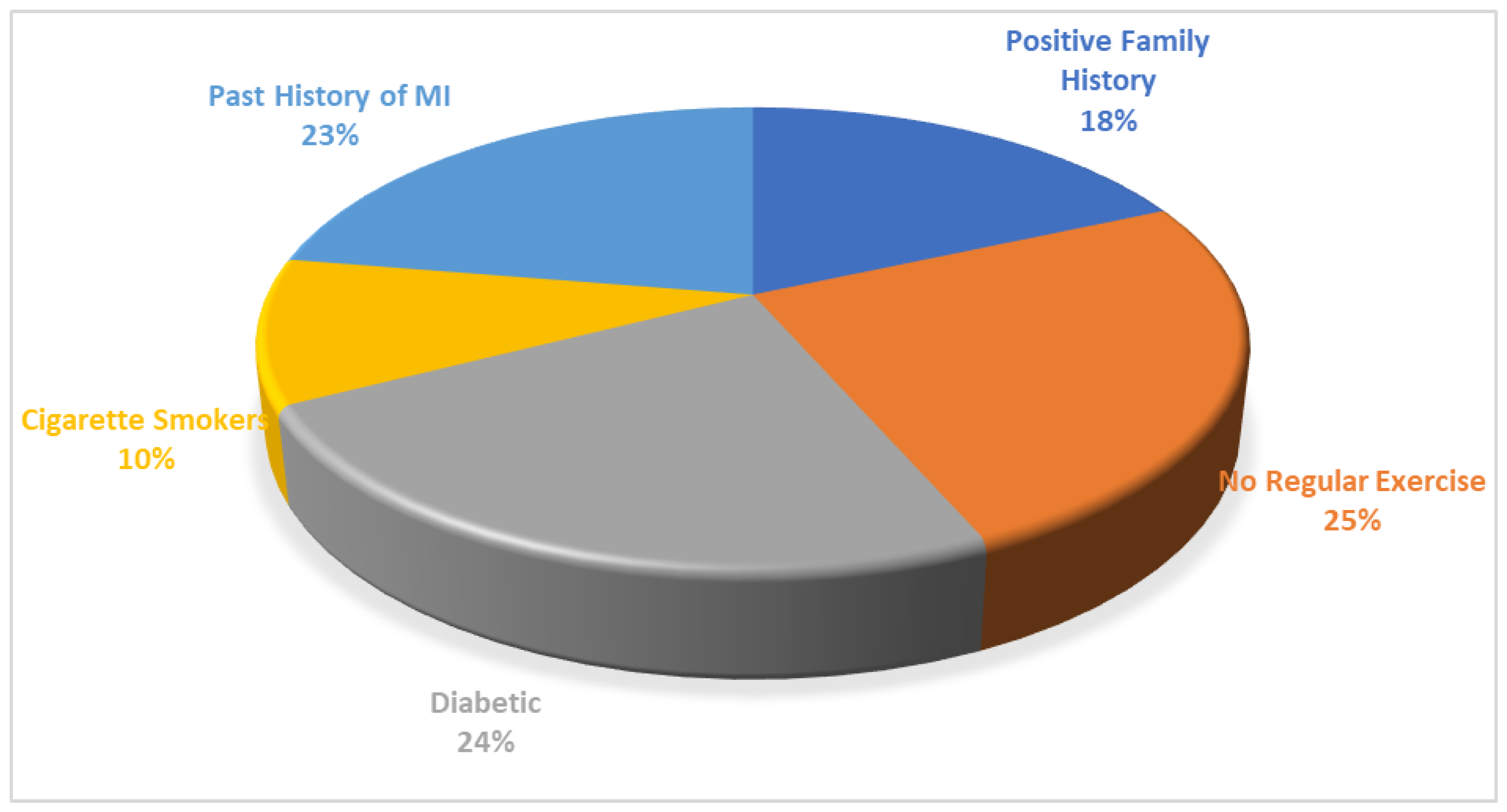

Table 2). The analysis of risk factors in cardiomyopathy patients indicated that, of 100 cardiomyopathies patients, 44.3% patients had family history for cardiovascular myopathies, 60.7% with no daily activity, 21.3% having diabetes alongside cardiomyopathy, 24.6% people were cigarette smokers, 54.1% people had past history of MI, one of the risk factors in the initiation and advancement of cardiovascular myopathies particularly enlarged cardiomyopathy (

Figure 1).

3.2. Distribution of Biochemical and Echocardiographic Findings Among Cardiomyopathy Subgroups

Among the cardiomyopathy subjects, 54% had IDCM, followed by DCM (20%), HCM (15%), and PPCM (11%) with no ARVC patients found during studied period. The mean values of studied parameters, including ARD, LAD, ST, systolic diameter, diastolic diameter, EF, BMI, and BNP, were 68.3 ± 13.3, 25.1 ± 4.3, 28.7 ± 3.6, 39.9 ± 6.2, 9.7 ± 2.0, 51.2 ± 8.8, 60.9 ± 7.5, 23.9 ± 6.2, 25.1 ± 4.3, and 2367 ± 850 pg/mL, respectively, IDCM subjects. For patients with DCM, the mean values were 63.0 ± 15.2, 24.8 ± 3.7, 29.8 ± 3.3, 42.7 ± 7.0, 10.2 ± 2.0, 52.8 ± 10.6, 60.8 ± 10.5, 25.0 ± 8.3, 24.8 ± 3.7, and 1523 ± 750 pg/mL, respectively. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in the mean values of echocardiographic parameters (LAD, ST, systolic diameter, diastolic diameter, and EF) and age. However, there were no significant differences in the mean values of LAD, BMI or BNP among all groups (

Table 3).

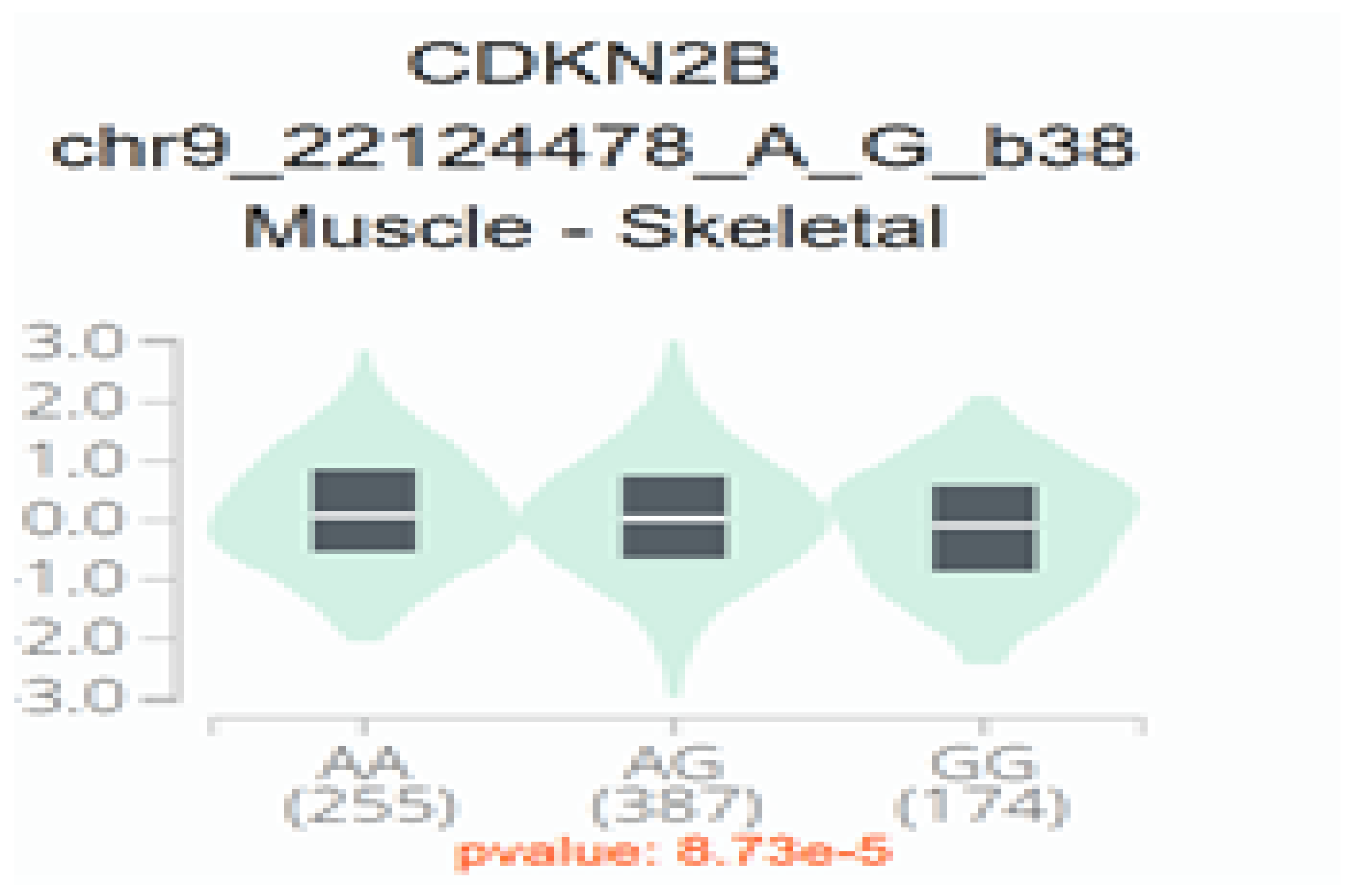

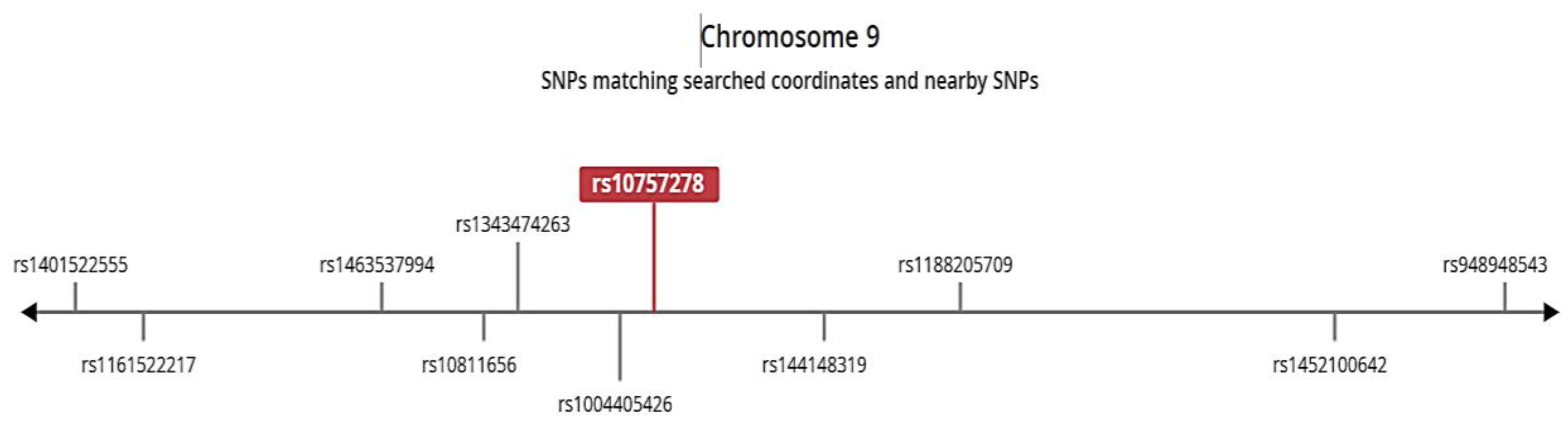

3.3. Functional Analysis

The phenome wide analysis across UK Biobank is given in supplementary file 1. It revealed that rs10757278 is associated with multiple phenotypes linked to development of heart diseases, specifically the stronger association with CAD and chronic ischemic heart disease (p=1.09E-93, p=2.09E-71 respectively). The specific features and functional annotation of SNP through RegulomeDB (

Figure 2) and GTEx identified the regulome score of 1 and ranked as 3a indicating it having a regulatory function as effecting the enhancer regions. Single Tissue eQTL for this SNP is given in

Table 4, with the expression associated with allcardio genotypes in specific Skeletal Muscle tissue (

Figure 3). The genotype GG and AG are associated with the relatively reduces expression level in the tissue as compared to AA, suggesting that G allele contributes to decreased protein expression. The SNP is found in closed linkage disequilibrium with the rs144148319 and rs1004405426 (

Figure 4).

3.4. Association of Disease Phenotype with Genotype and Risk Alleles: MAF and Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Analysis

Genotype frequencies of SNP rs10757278 for each participant are given in

Table 5, indicates AG genotype frequency was the highest (0.42) in cases, followed by AA genotype (0.30), while the GG genotype, associated with disease susceptibility, was the lowest in controls (0.15) but significantly higher in cases (0.28). Similarly, the allelic frequency of the A allele was higher in controls (0.68), suggesting a protective effect, whereas the G allele showed a higher frequency in cardiomyopathy patients (0.48), indicating its association with disease (

Table 5).

Minor allele frequency (MAF) was calculated for each type of cardiomyopathy, along with the control group. Our results revealed that MAF varies across cardiomyopathy types. For subjects with DCM, HCM, PPCM, and IDCM, MAF frequencies were recorded as 0.32, 0.31, 0.45, and 0.67, respectively, while the control group exhibited a lower MAF of 0.25 (

Table 6). Chi-square analysis was applied to test Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE), revealing that the data for all groups except IDCM followed HWE (p-value > 0.05). The G allele emerged as an independent risk allele for cardiomyopathy, particularly IDCM, in the investigated Pakistani population.

The high frequency of the G allele in IDCM, along with its deviation from HWE, underscores its potential role in disease susceptibility. Additionally, the moderate frequency of the G allele in PPCM suggests some level of association, although not as pronounced as in IDCM. This highlights the distinct genetic risk profiles among different types of cardiomyopathies (

Table 6). The risk association of G allele were calculated and we found a strong association of the G allele with IDCM, with an odds ratio (OR) of 4.73 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 2.75–8.15, indicating a significantly higher risk compared to controls. A moderate association was observed with PPCM, showing an OR of 1.79 (95% CI: 1.05–3.05). However, no significant association was found with DCM or HOCM, as their CIs included 1 (OR: 1.00 and 0.97, respectively). Our findings suggested that the G allele may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and, to a lesser extent, PPCM (

Table 6).

A significant association is found between rs10757278 and disease phenotype (Chi-sq. = 6.979, p-value = 0.03052). Comparison analysis of genotypes between all cases and controls by logistic regression model further identified significant association with the GG genotype (p=0.00958 **). Among all studies groups of cardiomyopathies, IDCM was found to have significant association with rs10757278 (Chi-sq=11.679, p = 0.00291), specifically with GG and AG (p=0.02613, p=0.00104 respectively). Logistic regression of allele frequencies identified that risk allele G is positively associated with IDCM, (p= 0.0031, OR= 3.19, 95%, CI= 1.51-7.17 ) indicating G allele increasing the likelihood of outcome. However, A allele is found to have negative association with outcome thus having protective role on disease phenotype (p=0.00961, OR=0.35, 95%CI=0.15-0.177). A moderate association was observed with PPCM, showing an OR of 1.79 (95% CI: 1.05–3.05). However, no significant association was found with DCM or HOCM, as their CIs included 1 (OR: 1.00 and 0.97, respectively). Our findings suggested that the G allele may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and, to a lesser extent, PPCM. A significant association of is also found with MI (Chi-sq = 11.371, p = 0.003395) and Systolic Diameter (Chi-sq=131.77, p=0.002725) while no association of rs10757278 is found with other parameters including Aortic Root Diameter (Chi-sq=23.228, p=0.9183), Left Atrium Diameter (Chi-sq=65.15, p=0.1041), Septal Thickness (Chi-sq=37.926, p=0.4729), Diastolic Diameter(Chi-sq=91.435, p=0.0608), Ejection Fraction (Chi-sq=23.783, p=0.252).

HWE value indicated that all groups except IDCM followed HWE (p-value > 0.05). The G allele is an independent risk allele for cardiomyopathy, particularly IDCM, in the investigated Pakistani population. The high frequency of the G allele in IDCM, along with its deviation from HWE, underscores its potential role in disease susceptibility.

4. Discussion

The present study was aimed to explore the association of rs10757278 SNP, particularly the G allele, with different subtypes of cardiomyopathies in Pakistani population. Our study identified that the MAF and its association with risk differed widely amongst the various subtypes of cardiomyopathy. Importantly, the presence of the G allele exhibited a significantly strong correlation with IDCM, underscoring its potential as a genetic risk factor for IDCM. Moderate association was also seen with PPCM while DCM and HOCM showed no significant association. These findings emphasizes the complex genetics of cardiomyopathies and highlight the potential of SNP rs10757278 as a susceptibility marker in IDCM.

IDCM, which is the sub-type of DCM, is caused by ischemic heart disease, such as CAD or MI [

8]. SNP rs10757278 is related to the increase in the risk of CAD and MI, it might indirectly play `vital' roles in the mechanism of IDCM. However, few studies have specifically investigated the role of rs10757278 in IDCM. The G allele of the rs10757278 polymorphism has been consistently associated with increased risk of CAD and MI in previous studies. Homozygous G allele individuals have been found at increased risk of these illnesses, studies indicating that this SNP may account for 20-30% of heart disease cases [

17].

We compared our results with previously conducted studies in Pakistan. A single centre study done over a 12-year period in Peshawar described echocardiographic findings of different types of cardiomyopathy. Their findings revealed that DCM was the most frequently diagnosed subtype (66%), followed by PPCM and HOCM, with frequencies of 11% and 8%, respectively, across both adult and pediatric age groups [

18]. Similarly, in our study, DCM accounted for 64% of the total cases, while PPCM was observed in 11%, closely quite similar to the Peshawar study. Khan and his colleague discovered IDCM as the main reason for Heart failure in 36% of patients which matches well with our study [

19]. The consistent nature of these findings highlights the importance of DCM as a predominant subtype of cardiomyopathy in the local population.

Soman et al. (2023) investigated NT-proBNP level changes among patients with ischemic and non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. In their study, the proportion of males was higher in both groups, which is in agreement with our findings, wherein 57% of the patients were male. In their study, the mean age of patients in the IDCM group was 64 ± 11 years while in our study the mean age of this group was 68.3 ± 13.3 years which is also comparable. They reported a higher NT-proBNP level with a mean value of 3100 ± 2906 pg/mL in patients with IDCM than our reported results which was 2367 ± 850 pg/mL [

20]. This difference can be attributed to variations in baseline characteristics or severity of the disease or healthcare practice.

Our observed mean echocardiographic findings and low EF values are consistent with those reported in recent and past studies by Gouda et al. (2024) and Rihal et al. (1994), respectively. Both studies reported dilated ventricles and reduced EF in cardiomyopathy groups, aligning with our findings [

21,

22].

We compared the genetic frequencies identified in our cohort to those described in the Polish population in order to validate. Niemiec et al. (2012) reported allele frequencies for A and G were 0.47 and 0.53, respectively, which are comparable to the frequencies observed in our study [

23]. The frequency of the G allele and GG genotype was significantly higher in CAD patients than in controls (p=0.011 and p=0.006, individually).The ARIC study by Yamagishi et al. (2009) demonstrated that the GG genotype of rs10757274 on chromosome 9p21 is associated with increased HF and CAD risk, particularly among white participants (n= 11085). Similarly, our study highlights the association of the GG genotype of rs10757278 with cardiomyopathies, particularly IDCM, in the Pakistani population [

24].

Nawaz et al. (2015) identified a significant association between the G allele of rs10757274 on chromosome 9p21 and increased CAD risk in a Pakistani population, with the GG genotype more frequent in patients. Similarly, our study found the G allele and GG genotype of rs10757278 to be more frequent in cardiomyopathy cases, particularly IDCM. Both studies underscore the 9p21 locus as a key genetic risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in the Pakistani population [

25].

Numerous studies, including GWAS and meta-analyses, have firmly established the 9p21 locus as a significant predictor of MI and cardiomyopathy [

26]. Research from local, Indian, Asian, and global populations consistently supports this association [

27,

28,

29]. Given that CAD and MI are key etiological factors in the development of cardiomyopathies, particularly IDCM, our findings confirm a strong association between the rs10757278 polymorphism and IDCM. While specific data linking rs10757278 to heart failure remain scarce, our study highlights its critical role in the progression of cardiomyopathy, emphasizing the need for further research to explore its mechanistic implications in heart failure and other cardiovascular conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study identifies the GG genotype of rs10757278 on chromosome 9p21 as a significant risk factor for cardiomyopathies, particularly IDCM, in the Pakistani population. The findings suggest that this polymorphism contributes to disease progression alongside CAD. Our findings support the hypothesis that this polymorphism contributes to the initiation and progression of cardiomyopathies, likely in conjunction with CAD. The G allele emerges as a key genetic predictor, emphasizing the need for larger studies to confirm its frequency and role in cardiomyopathy pathogenesis.

6. Limitation of Study

This study has several limitations, such as using a single SNP without functional data support on a smaller sample size which can limits genetic insights. Also, there is no functional data supporting the involvement of rs10757278 in cardiomyopathy. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into genetic risk factors for IDCM, and future studies should address these issues to further validate and expand upon the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Muhammad Noor ul Amin and Pakeeza Arzoo Shaiq; Data curation, Asad Raja, Rafaqat Ishaq, Abida Arshad and Muhamamd Asad; Formal analysis, Muhammad Noor ul Amin and Muhammad Ilyas; Funding acquisition, Ghazala Raja; Investigation, Muhammad Noor ul Amin, Shahid Rashid, Asad Raja and Muhammad Ilyas; Methodology, Muhammad Noor ul Amin, Shahid Rashid and Rafaqat Ishaq; Project administration, Ghazala Raja; Resources, Pakeeza Arzoo Shaiq; Software, Umm Habiba and Rafaqat Ishaq; Supervision, Pakeeza Arzoo Shaiq; Validation, Muhammad Noor ul Amin and Muhamamd Asad; Visualization, Abida Arshad; Writing – original draft, Muhammad Noor ul Amin, Umm Habiba and Asad Raja; Writing – review & editing, Abida Arshad, Muhamamd Asad and Pakeeza Arzoo Shaiq.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as it involved human participants, and was approved by the Research and Ethics Review Committee of the Rawalpindi Institute of Cardiology (Approval No. RIC/RERC/01/21 dated 05/01/2021) and the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) of Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi (Approval No. PMAS-AAUR/IEC/18 dated 14/02/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants involved in this study provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any impact on their medical treatment or rights. Confidentiality and anonymity of all personal data were ensured.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality and privacy concerns regarding patient information.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Cardiologists and the laboratory staff of Rawalpindi Institute of Cardiology for their valuable support and collaboration. Special thanks to the research lab staff of the UIBB, ARID Agriculture University, Rawalpindi for their hard work and dedication throughout the course of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DCM |

Dilated Cardiac Myopathies |

| HCM |

Hypertrophic Cardiac Myopathies |

| RCM |

Restrictive Cardiac Myopathies |

| ARVC |

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| MI |

Myocardial Infarction |

| IDCM |

Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy |

| PPCM |

Peripartum Cardiomyopathy |

References

- Ciarambino, T.; Menna, G.; Sansone, G.; Giordano, M. Cardiomyopathies: an overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salemi, V.M.C.; Mohty, D.; Altavila, S.L.L.D.; Melo, M.D.T.D.; Kalil Filho, R.; Bocchi, E.A. Insights into the classification of cardiomyopathies: past, present, and future directions. Clinics 2021, 76, e2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankuweit, S.; Richter, A.; Ruppert, V.; Maisch, B. Classification of cardiomyopathies and indication for endomyocardial biopsy revisited. Herz 2009, 34, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smail, M.M.A.; Singh, R.B.; Rupee, S.; Rupee, K.; Hanoman, C.; Ismail, A.; Singh, J.; Adeghate, E. Treatment of heart failure using angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor. In Pathophysiology, Risk Factors, and Management of Chronic Heart Failure; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 361–367. [CrossRef]

- Lakdawala, N.K.; Givertz, M.M. Dilated cardiomyopathy with conduction disease and arrhythmia. Circulation 2010, 122, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Data. Cardiomyopathies Epidemiology Analysis and Forecast, 2021–2031, Report Code GDHCER296-22-ST, 2022.

- Bhandari, B.; Quintanilla Rodriguez, B.S.; Masood, W. Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023.

- Pastena, P.; Frye, J.T.; Ho, C.; Goldschmidt, M.E.; Kalogeropoulos, A.P. Ischemic cardiomyopathy: epidemiology, pathophysiology, outcomes, and therapeutic options. Heart Fail. Rev. 2024, 29, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Precone, V.; Krasi, G.; Guerri, G.; Madureri, A.; Piazzani, M.; Michelini, S.; Bertelli, M. Cardiomyopathies. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parmensis 2019, 90, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Pereira, N.L. Genetics of cardiomyopathy: clinical and mechanistic implications for heart failure. Korean Circ. J. 2021, 51, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posafalvi, A.; Herkert, J.C.; Sinke, R.J.; Van Den Berg, M.P.; Mogensen, J.; Jongbloed, J.D., et al. Clinical utility gene card for: dilated cardiomyopathy (CMD). Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21. [CrossRef]

- Le, A.; Peng, H.; Golinsky, D.; Di Scipio, M.; Lali, R.; Paré, G. What Causes Premature Coronary Artery Disease? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2024, 26, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmak, G.J.; Titov, B.V.; Matveeva, N.A.; Bashinskaya, V.V.; Shakhnovich, R.M.; Sukhinina, T.S., et al. Impact of 9p21.3 region and atherosclerosis-related genes' variants on long-term recurrent hard cardiac events after a myocardial infarction. Gene 2018, 647, 283–288. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Colvin, M.; Cook, J.; Cooper, L.T.; Deswal, A.; Fonarow, G.C., et al. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for specific dilated cardiomyopathies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134, e579–e646. [CrossRef]

- Tcheandjieu, C.; Zhu, X.; Hilliard, A.T.; Clarke, S.L.; Napolioni, V.; Ma, S., et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study of coronary artery disease in genetically diverse populations. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1679–1692. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, 2001.

- Lu, W.H.; Zhang, W.Q.; Zhao, Y.J.; Gao, Y.T.; Tao, N.; Ma, Y.T., et al. Case–control study on the interaction effects of rs10757278 polymorphisms at 9p21 locus and traditional risk factors on coronary heart disease in Xinjiang, China. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 75, 439–445. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyas, S.; Fawad, A.; Ilyas, H.; Hameed, A.; Awan, Z.A.; Zehra, A., et al. Echomorphology of cardiomyopathy: review of 217 cases from 1999 to 2010. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2013, 63, 454–458.

- Khan, H.; Jan, H.; Hafizullah, M. A hospital-based study on causes peculiar to heart failure. J. Tehran Univ. Heart Cent. 2009, 4, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Soman, S.O.; Vijayaraghavan, G.; Soman, B.; Ankudinov, A.S.; Kalyagin, A.N. N-Terminal Pro-BNP (NT-ProBNP) and high sensitive troponin levels in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Ann. Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 5, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, P.; Liu, Y.; Butler, J.; Del Prato, S.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Lam, C.S.P., et al. Relationship between NT-proBNP, echocardiographic abnormalities and functional status in patients with subclinical diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rihal, C.S.; Nishimura, R.A.; Hatle, L.K.; Bailey, K.R.; Tajik, A.J. Systolic and diastolic dysfunction in patients with clinical diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy: relation to symptoms and prognosis. Circulation 1994, 90, 2772–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, P.; Gorczyńska-Kosiorz, S.; Iwanicki, T.; Krauze, J.; Trautsolt, W.; Grzeszczak, W., et al. The rs10757278 polymorphism of the 9p21.3 locus is associated with premature coronary artery disease in Polish patients. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 2012, 16, 1080–1085. [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, K.; Folsom, A.R.; Rosamond, W.D.; Boerwinkle, E. A genetic variant on chromosome 9p21 and incident heart failure in the ARIC study. Eur. Heart J. 2009, 30, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.K.; Noreen, A.; Rani, A.; Yousaf, M.; Arshad, M. Association of the rs10757274 SNP with coronary artery disease in a small group of a Pakistani population. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2015, 15, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, N.; Imai, Y.; Morita, H.; Nagai, R. Genome-wide association study of coronary artery disease. Int. J. Hypertens. 2010, 2010, 790539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanushali, A.A.; Parmar, N.; Contractor, A.; Shah, V.T.; Das, B.R. Variant on 9p21 is strongly associated with coronary artery disease but lacks association with myocardial infarction and disease severity in a population in Western India. Arch. Med. Res. 2011, 42, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogari, N.M.; Allam, R.M.; Dannoun, A.; Athar, M.; Bouazzaoui, A.; Elkhateeb, O., et al. Role of single nucleotide polymorphism rs2383206 on coronary artery disease risk among Saudi population: a case-control study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 6100–6107.

- Taheri Bajgan, E.; Zahedmehr, A.; Shakerian, F.; Maleki, M.; Bakhshandeh, H.; Mowla, S.J.; Malakootian, M. Associations between low serum levels of ANRIL and some common gene SNPs in Iranian patients with premature coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).