1. Introduction

With the rapid development of science and technology, wireless services such as cloud-based extended reality, holographic communication and intelligent interaction are becoming more prevalent. To provide real-time immersive user experience, the Wireless Computing Power Network (WCPN), as a highly integrated intelligent framework, is capable of delivering intense and adaptive computing services for consumers through the deep integration and utilization of distributed reachable computing resources[

1,

2,

3]. Morever, WCPN can effectively cope with the challenge of load imbalance by decomposing computing tasks and coordinating between computing nodes [

2,

3], fully utilizing available computing resources, and providing fast and accurate computing services. However, WCPN largely relies on data, and the correctness of its decisions depends on the diversity of data used for training. Therefore, relying only on local data from devices to train is far from enough. And it is necessary to combine data from other devices to provide sufficient amounts and diversity of data. However, local data on devices is the privacy of users, sharing this data may be used for other malicious purposes, which deviates from the original intention of improving user experience. Recognizing these potential risks of privacy leakage, a distributed machine learning model, Federated learning (FL), has emerged [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Unlike traditional machine learning methods that run in data centers, FL only needs to send machine learning models to various intelligent devices for training. After training, smart devices upload trained models to central nodes, which then aggregate the models uploaded by various smart devices. The aggregated model is a comprehensive model that combines data from all smart devices. There is no interaction between device original data during this process, only the uploading of device machine learning models, which protects user data privacy security while achieving the goal of collaborative machine learning with multiple devices. Therefore, FL has been applied to enable distributed intelligence of WCPN, which guarantees the security of computing nodes and the privacy of computing devices [

8].

In FL, the central node needs to connect with a large number of user devices and receive the distribute machine learning models in each global aggregation [

5,

9]. With the rapid development of WCPN, the number of intelligent devices is overwhelming and still increasing. The performance requirements of these devices for machine learning will certainly make the coverage of FL wider and the scale of machine learning models larger, which will exert tremendous pressure on the computing architecture. However, due to the limited spectrum resources, there are always some user devices that do not have enough spectrum resources to transmit machine learning models, resulting in slow or even failed transmission tasks. These users are called draggers or laggards, and their transmission latency has a decisive impact on the efficiency of FL. Therefore, dragger problems are indispensable in the research of FL [

6,

7,

10]. To improve the efficiency of FL, some studies based on different design principles propose various device scheduling strategies, including reducing draggers and minimizing convergence time [

11,

12]. In addition, due to the heterogeneity of smart devices’ computing capabilities , communication conditions and imbalanced service demands, it is usually possible for a single node to provide FL services, which may lead to device overloading and communication congestion [

13,

14]. To address this massive computational demand, W. Sun et al. combined asynchronous FL WCPN framework by jointly optimizing the computation strategy of individual computing nodes and their collaborative learning strategies to minimize the total energy consumption of all computing nodes [

15]. This algorithm performs excellently in terms of learning accuracy, convergence speed, and energy conservation.

The architecture of WCPN enables users to receive dense and adaptive computing tasks without knowing the exact service deployment, they only need to provide their own service demands.The service delay caused by insufficient computing power, poor communication conditions, or other factors is extremely lethal for time-sensitive tasks, especially for those that require real-time monitoring and control. The interval between data generation and its invocation is a key factor affecting task performance, which is referred to as the Age of Information (AoI) [

16]. AoI has become an important metric for measuring data freshness. There have been several studies on the impact of AoI on different optimization objectives, and they have sought to enhance data utilization efficiency and reliability by minimizing the AoI defined in this specific scenario [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. To minimize the average age of critical information (AoCI) of mobile clients, X. Wang et al. built a system model based on request response communication. [

25]. They proposed an information sensing heuristic algorithm based on Dynamic Programming (DP), which showed advantages in terms of average AoCI under various network parameters and had a short convergence time. Furthermore, W. Dai et al. studied the convergence behavior of extensive distributed machine learning models and algorithms with delayed update [

26]. Through numerous experiments, it was demonstrated that delayed updates significantly reduce the convergence speed of FL global models due to the influence of Gradient Coherence. In other words, the staleness of each local model in FL affects the convergence speed of the global model, and outdated local models may negatively impact global model convergence when they update in opposite directions from the current global model.

Caching originates from computer systems, where copies of frequently used commands and data are stored in memory[

27]. To enhance the commnucation efficiency of FL, several researches proposed the cache scheme to improve FL, which can effectively reduce the training time of FL by reducing per-iteration training time[

28,

29,

30]. However, Existing research on FL with caching lacks in-depth exploration of the AoI. Besides, although excellent AoI can significantly improve the performance of time-sensitive machine learning models, the cost of pursuing excellent AoI in the FL framework is often to bring about significant service delays. Therefore, to improve the quality and models in WCPN, this paper proposed a FL with caching resource scheduling strategy, then focuses on optimizing resource coordination, improving service quality and reducing parameter age related to machine.

1.1. Relate Works

In many time-sensitive FL tasks, both the quality of data used for local training and the quality of uploaded models are closely related to their age. Outdated parameter ages can result in slower convergence rates for FL and reduce the performance of the global model. To tackle these issues, several recent studies have focused on optimizing the data parameter age during the device scheduling process.

In [

31], the parameter age is incorporated into the device scheduling process in FL, and an age-aware wireless network FL communication strategy is proposed to prevent the devices from exiting training using energy collection technology. The fast and accurate model training can be achieved by jointly considering the aging of parameters and the heterogeneous capabilities of terminal devices. In [

32], the authors propose a theoretical framework for statistical AoI provisioning in mobile edge computing (MEC) systems based on Stochastic Network Calculus (SNC) to support the tail distribution analysis of AoI. Additionally, they design a dynamic joint optimization algorithm based on block coordinate descent to solve the energy minimization problem. In [

33], the authors focus on the timeliness of MEC systems, believing that the freshness of data and computing tasks is very important, and establish an age-sensitive MEC model, where the AoI minimum problem is defined. A new hybrid policy-based multimodal deep Reinforcement Learning (RL) framework with edge FL mode is proposed, which not only outperforms the baseline system in terms of average system age but also improves the stability of the training process. In [

34], considering the time-sensitive IoT system with UAV assistance, the research on information freshness in the system is conducted, and a node data acquisition algorithm based on DDQN is proposed to effectively reduce the average information age of the system by optimizing the flight trajectory and transmission sequence of sensors. In [

35], we propose FedAoI, an AoI based client selection policy. FedAoI ensures fairness by allowing all clients, including stragglers, to submit their model updates while maintaining high training efficiency by keeping round completion times short. In [

36], the authors formulate the problem of multi-UAV trajectory planning and data collection as a Mixed Integer NonLinear Programming (MINLP), aiming to minimize the AoI and the energy consumption of IoT devices. The formulation takes into account the flight constraints of UAVs, the limitations of device data collection, and interference coordination conditions. In [

37], considering the trade-off between data sampling frequency and long-term data transmission energy consumption while maintaining information freshness, a two-stage iterative optimization framework based on FL is proposed to minimize the global mean and variance of transmission energy, saving a large amount of execution energy with relatively small performance loss.

In addition to considering the impact of parameter age in federated machine learning, these works have achieved good optimization results in terms of service delay or energy consumption. However, they have not conducted in-depth research on time-sensitive data itself and have not fully considered the potential reference value of lagging user models, stopping at resource scheduling optimization strategies for shortening service delay. Based on these considerations, this paper designs a WCPN FL framework with dual caches that comprehensively considers parameter age, energy consumption, and service delay, and optimizes the iteration strategy. Besides, a WCPN FL resource scheduling strategy based on information age perception is proposed, which designs a dynamic scheduling strategy to enable as many users as possible to participate in FL in a timely manner by jointly considering the parameter freshness and heterogeneity of terminal devices.

1.2. Contributions and Paper Organization

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows.

To consider the trade-off between parameter age and service delay, we designed a FL resource scheduling strategy based on information age perception in WCPN, which takes advantage of data caching mechanisms. This strategy optimizes device’s data collection frequency, computation frequency, and spectral resources to improve the global model performance in FL.

In this paper, we comprehensively consider the aging of parameters, time-varying channels, random FL request arrivals, and heterogeneous computing capabilities among participating devices. We model the high-dimensional dynamic multi-user centralized FL framework system as a MDP, using the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm to solve for the minimization of global parameter age, energy consumption, and FL service delay.

Sufficient comparative simulation experiments are designed to verify the correctness and superiority of our scheme, and the reasons are analyzed and demonstrated.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section II proposes a dual-cache FL framework with local data caching and server model caching, and present the problem of the WCPN FL resource scheduling strategy based on information age perception in this work. Section III formulates the MDP for the target problem and then construct an age-aware PPO double-cache FL scheduling algorithm to solve the corresponding optimal solution. Section IV demonstrates the performance of our proposed approach through extensive simulation studies, providing simulation results and theoretical analysis. Finally, we summarize this paper in Section V.

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

In related research on conventional FL, it is usually assumed that intelligent terminals collect data in advance for model training. However, this can lead to a certain degree of aging of the data. This case of higher AoI is very unfriendly for some tasks that are sensitive to AoI. In addition, collecting data only when receiving FL requests may ensure sufficient freshness, but the service delay during data collection may be unbearable. Therefore, it is necessary to make a balance between service delay and information age and coordinate their needs reasonably.

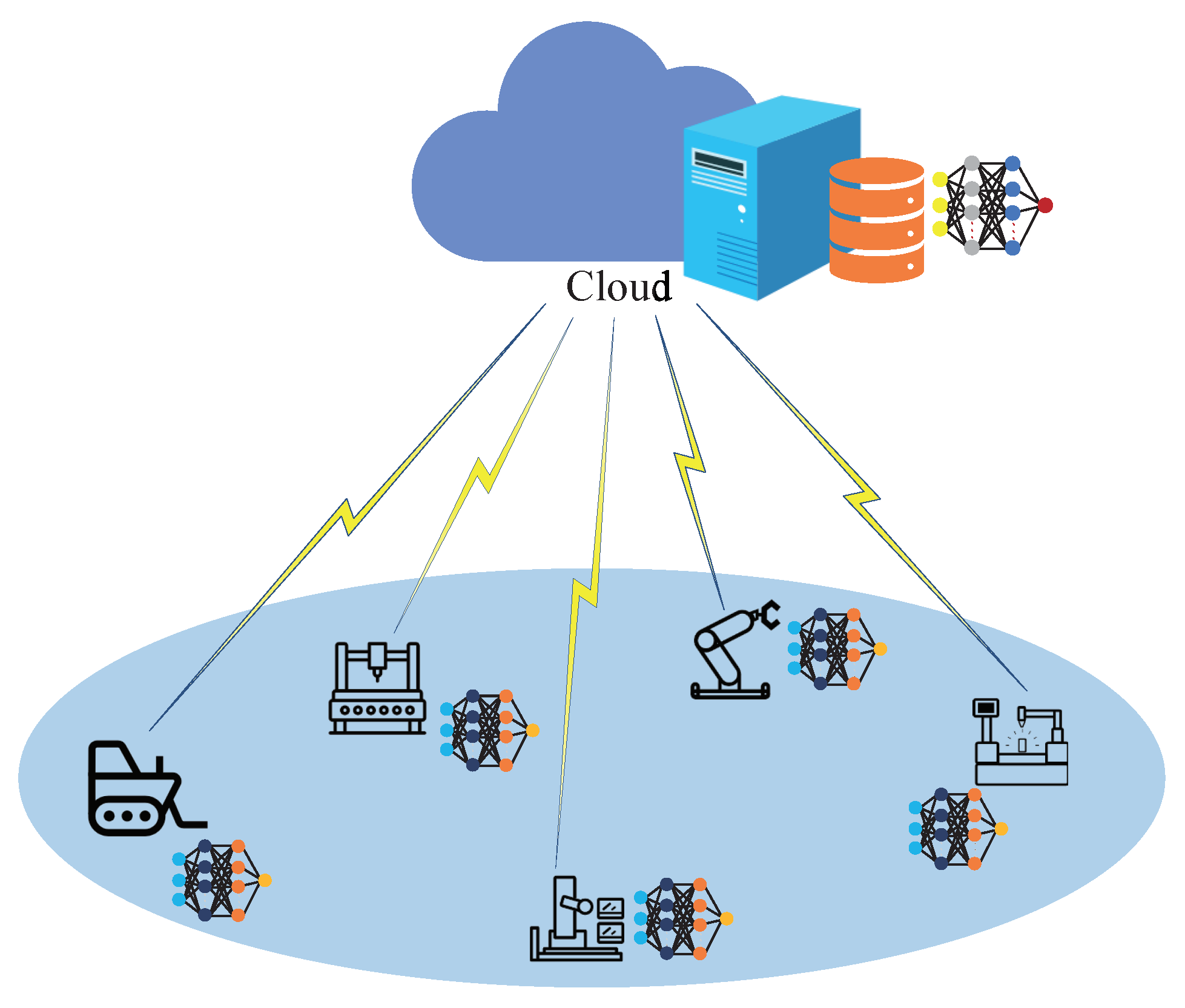

Our system model, as shown in

Figure 1, consists of a central server and

K smart devices which have data collection and local computing capabilities. These devices share limited spectrum resources to interact with the central server for local model upload. The model owner initiates a FL task involving a set of smart devices

. During the FL task, there can be multiple instances of model training requests initiated by the model owner, and each participating intelligent device uses its local latest data to train the model together to maintain the global model. This paper assumes that each instance arriving at the request follows a Poisson process [

38]. First, FL-based model training is initiated based on the request from the model owner, with each model training taking place in N iterations to minimize the global loss

, where

N is specified by the model owner and

. Each iteration is composed of three steps in sequence:

The smart device k uses the locally collected and processed data to train the received global model to obtain the local model .

The smart device transmits the model parameters to the central server.

All the model parameters received from K smart devices are aggregated to obtain a new global model , which is then sent to each intelligent device for iterations.

In the synchronous FL scheme, the time taken for each iteration is limited by the slowest device. The central server needs to wait for all smart devices to complete local training, and then aggregate global model. Smart devices also need to obtain new global models to carry out the next round of iteration. To effectively reduce the service delay of FL (i.e., the delay from responding to FL to completing model uploading), this paper designs an age-aware dual-cache FL framework. Each smart device has a data cache buffer to pre-collect local training data. Meanwhile, the central server sets up a cache buffer to save models uploaded by lagging devices.

2.1. AoI and Service Latency Model

Since the diversity of uploaded parameters is crucial for training performance with non-independent distributed data, we utilize a bandwidth dynamic scheduling strategy to enable as many users as possible to participate in FL in a timely manner. In this paper, we propose a wireless network FL resource scheduling strategy based on information age awareness, which enables rapid and accurate model training by jointly considering the parameter freshness and heterogeneous capabilities of end devices. We jointly optimize AoI and resource allocation strategies to achieve a trade-off between FL accuracy, training time, and user energy consumption. Considering the potential impact of current scheduling on subsequent training and available resources, we describe the optimization problem as a MDP.

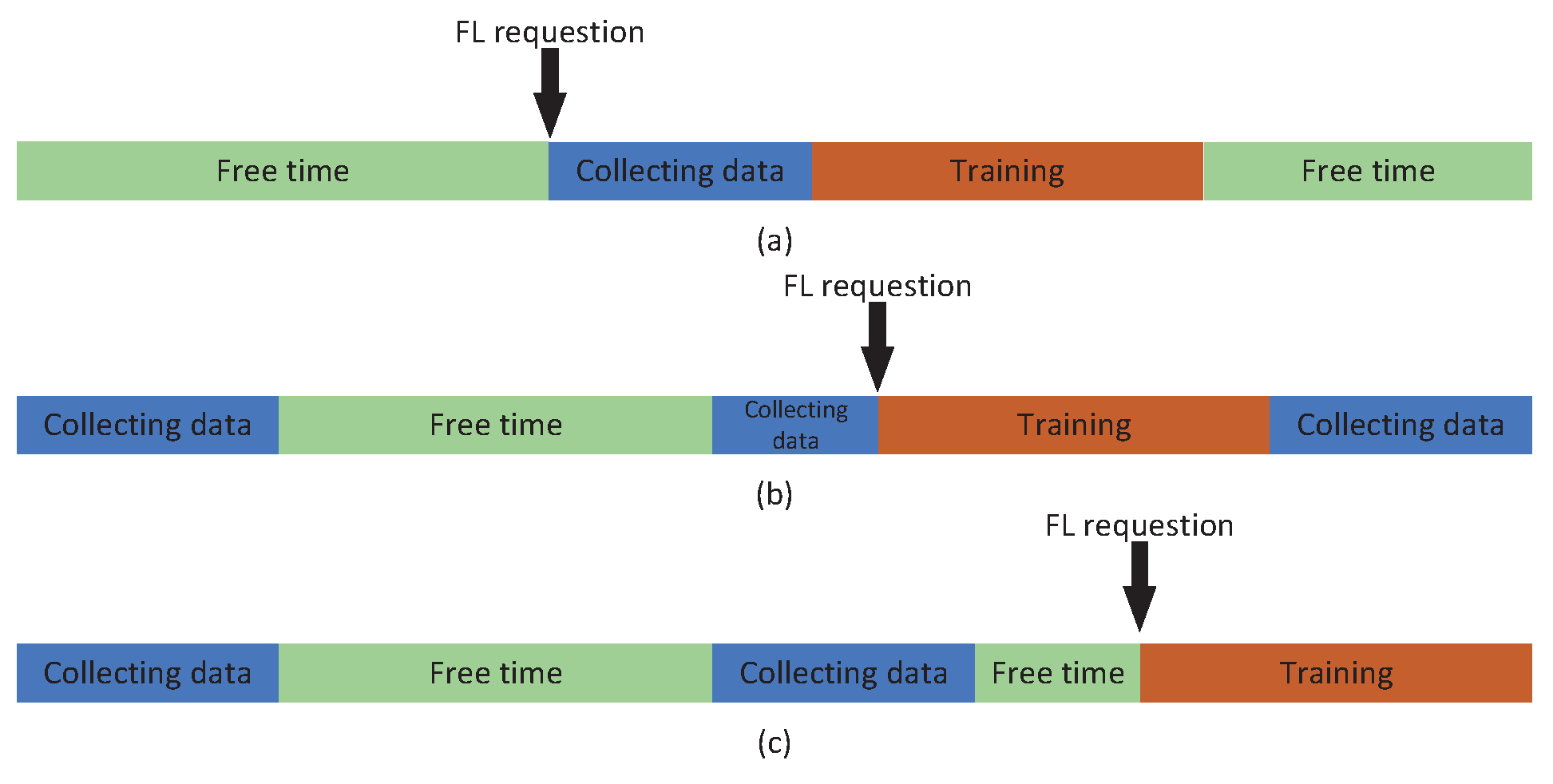

2.1.1. Local Delay and Age of Local Data

In

Figure 2, the time period during which device

k waits for FL training requests to complete local training includes idle time, data collection and processing time, and local model parameter training time. In traditional FL, users only start collecting training data and performing local training after receiving FL training requests, as shown in

Figure 2(a). The time delay for user

k to perform local model training is represented by

, while the time delay for device

k to collect required data samples is represented by

. Starting from the beginning of data collection and completing it before starting local training can ensure absolute data freshness, but it will result in significant delays, with a corresponding local delay of

.

Suppose the total Floating Point Operations(FLOPs) needed to process one data sample is

, and the FLOPs of each CPU cycle of device

k is

. Then, the time for device

k to process one data sample can be denoted by:

In this paper, we consider designing a data buffer mechanism for FL processes. Devices should adjust the data collection frequency

based on intelligent algorithms and collect data in intervals of time

during idle periods. As shown in

Figure 2(b) and

Figure 2(c), this approach can save the data collection process and quickly respond to FL while ensuring data freshness, with a local delay of

.

Assuming that device

k needs to collect

units of data samples for local training, data collection requires continuously collecting data and sending each group of data sequentially into the data buffer. If device

k has completed data collection processing and still hasn’t received FL training requests after waiting for

time, then new data will be collected to remain the freshness of data in the buffer. According to the First In First Out (FIFO) principle, the latest collected unit of data is sent to the tail of the buffer queue, and the unit of data at the head of the buffer queue will be discarded. As shown in

Figure 2(b), during the new data collection process, there are always enough data samples available in the local system to quickly respond to FL requests during the data collection period.

To quantify the freshness of each unit of data, device

k ages its data every time it passes through a time period

during idle time, which means:

where

represents the freshness of device

k’s

nth group of data at time

t. After receiving an FL request and completing local model training, device

k uploads the latest local model parameters

to the central server. In the process of uploading model parameters, the parameter upload rate cannot remain efficient and stable due to the dynamic changes in the geographical location and communication environment of device

k. Moreover, due to the instability of communication conditions, the probability that many devices fall behind during parameter upload increases significantly. Therefore, it is necessary to set a receive waiting time threshold

to limit the waiting time for the central server to receive device

k’s model. Let

. For device

k, its model can only be successfully aggregated in this round if

. Assuming that device

k receives an FL request at time

, the sum of all local data ages of device

k at this moment is

, and the model age will be calculated based on this basis, the optimization objective can be denoted as:

2.1.2. Transmission Delay and Age of Model

Considering the diversity of data samples is beneficial for improving model performance, while the freshness of device

local model also affects the convergence speed of the FL global model. Therefore, it is necessary to make reasonable use of limited bandwidth resources to enable as many models as possible that meet the age requirements to participate in global aggregation. For each device who responds to an FL request, they will upload their trained local model to the central server for aggregation of new global models. Due to dynamic changes in devices’ available computing resources and communication conditions, there is uncertainty in the delay between responding to an FL request and successfully uploading the local model to the central server. Therefore, due to the impact of local training and model upload delays, devices may risk missing multiple rounds of global aggregation. The Age of user

k’s local model

increases with the increase in global iteration times until the model is used for global aggregation or discarded due to being too old, which is denoted as:

where

is the time interval between two global iterations. Considering the impact of model utilization on its age, this paper sets a model freshness threshold

to limit models that exceed this age threshold and will be discarded from global model aggregation. Combining the constraints on service latency mentioned above, only when both conditions

and

are satisfied at the same time, will

be set, otherwise

, can be denoted as:

Based on the above analysis, the latest global model age for global aggregation is:

2.2. Energy Consumption Model

Considering that the central server has sufficient resources, we ignore energy consumption during the global model’s downlink process. In our model, energy consumption is mainly reflected in the local computation and model upload processes of smart devices. Given the heterogeneous computing resources and communication conditions of different smart devices, the time taken by each device for the processes of local computation and model upload is different, resulting in different energy consumption. In the following, we will model the energy consumption of these two processes separately.

2.2.1. Energy Consumption in Local Train

The calculation frequency of device

k can be approximately represented as:

where

is the coefficient determined by the chip structure of device

k, and

is the instantaneous voltage applied to the chip by device

k, and a threshold protection is applied to prevent damage to the chip due to high voltages for the purpose of preserving its lifetime. That is,

. The power consumed by this device under the given calculation frequency

can be calculated as follows:

where

can be considered as a constant determined by physical factors such as process and architecture of the chip, and is denoted as

. The number of FLOPs for local training by devices

k during one iteration is represented by

. The latency of local training during one FL iteration when device

k participates with data buffering mechanism can be calculated as follows:

In addition, the computation frequency

of device

k during data collection will be consistent with that during local training. Let

be the total number of collected data samples within the time interval between two global iteration

for device

k. Then, the local-phase energy consumption (including data collection and model training processes) of this devices can be calculated as follows:

2.2.2. Energy Consumption in Model Upload

Assuming that the maximum available bandwidth within the coverage area of the central server is

. If device

k is assigned with the bandwidth

, its data upload rate can be calculated as follows:

where

is the signal-to-noise ratio from device

k to the central server, and

bits is the size of the local model of device

k. The latency for uploading the model of device

k can be calculated as follows:

Let the transmission power during upload process be

. Then, the energy consumption of device

k uploading its local model can be calculated as follows:

The global iteration of the current round will only aggregate models that meet the requirements. The aggregated model is only related to the required devices, so the energy consumption generated during this iteration can be simply calculated by summing up the energy consumption of the corresponding devices, represented as:

2.3. Problem Formulation

We have set up data buffer and model buffer in both the device and server sides respectively. To ensure the performance of the models, we can ensure the data in each buffer is fresh enough by reducing the service latency of FL [

39]. In addition to age of parameter and FL service latency, system energy consumption is also an important factor that demands consideration. Therefore, can be denoted as:

To design frequency adjustment strategies for devices’ data collection, local computation, and bandwidth allocation, and to coordinate the global parameter age, energy consumption, and FL service latency. Therefore, the problem of equtation (

15):

where

ensures that each device has available spectrum resources for uploading their local models.

requires that the sum of global allocated spectrum resources to devices does not exceed the maximum available value globally.

requires that the adjusted computation resources of devices at current time cannot exceed the maximum available computation resources at the same time.

3. Algorithm

Considering the dynamic and high-dimensional nature of scenarios, it is very difficult to solve problem (

16) using traditional methods. In this section, the optimization problem (

16) is modeled as a MDP and deep reinforcement learning models are introduced for solving it. Q-learning and DQN are popular value-based RL methods that learn the action value function Q(s, a) related to the system’s rewards or penalties. However, when the action space becomes too large, finding the best action becomes extremely difficult. To overcome the complexity of the action space, a policy-based approach is introduced.

PPO is an on-policy RL algorithm that improves the Policy Gradient (PG) algorithm by retaining its excellent performance in continuous state and action spaces. The PG algorithm is updated by calculating the policy gradient estimate and maximizing the policy value using gradient ascent methods [

40]. PPO is parameterized by a set of parameters that parametrize the policy, replacing deterministic policies in value-based reinforcement learning with probabilistic distributions. Different actions are sampled from the return action probability list and optimized using neural network methods. It was developed from the Additive Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C) algorithm in 2017. The core idea of PPO is to limit the policy update range within a certain offset to avoid unstable problems caused by large or small updates, effectively balancing simplicity, sample complexity, and tuning difficulty.

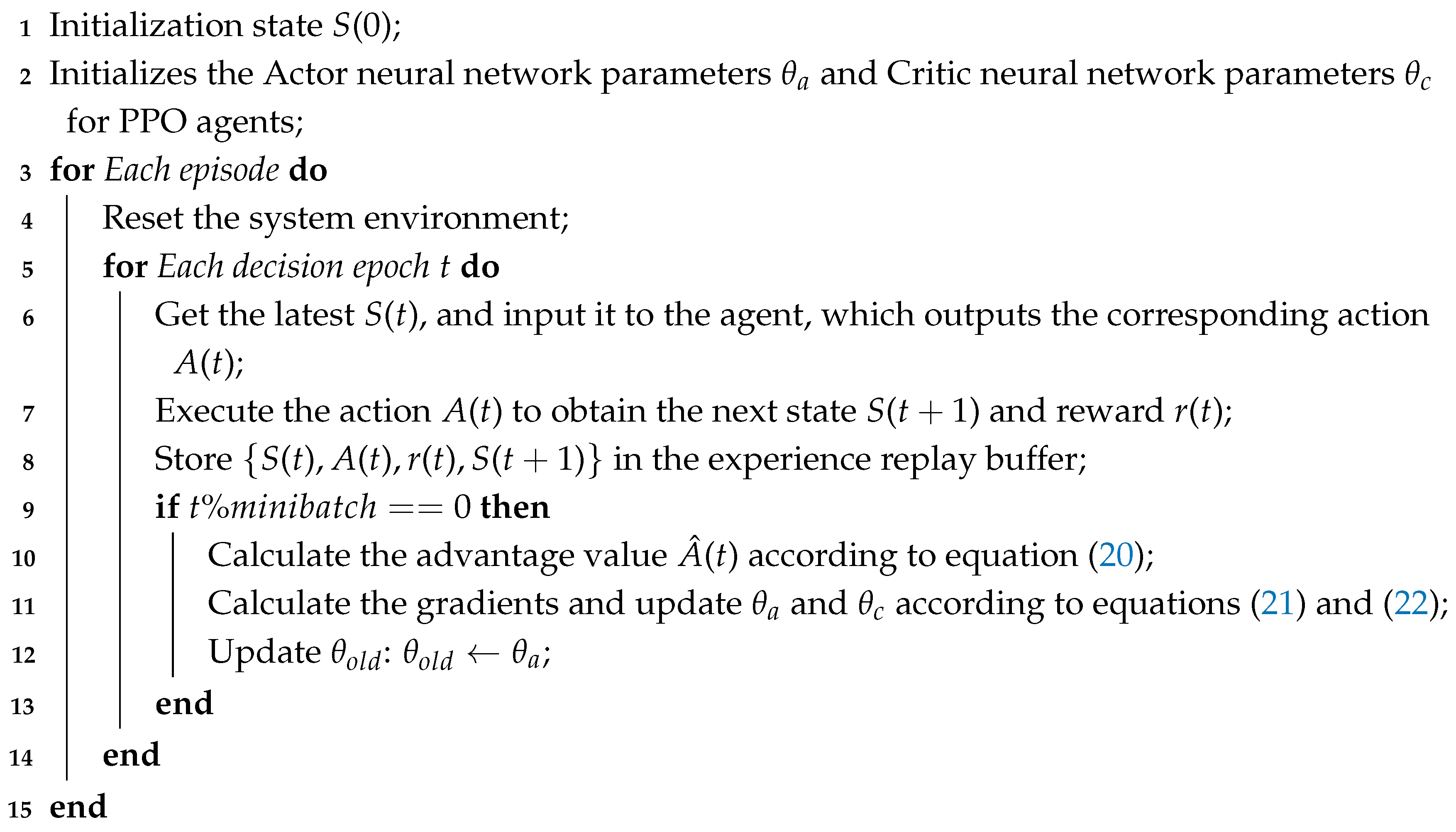

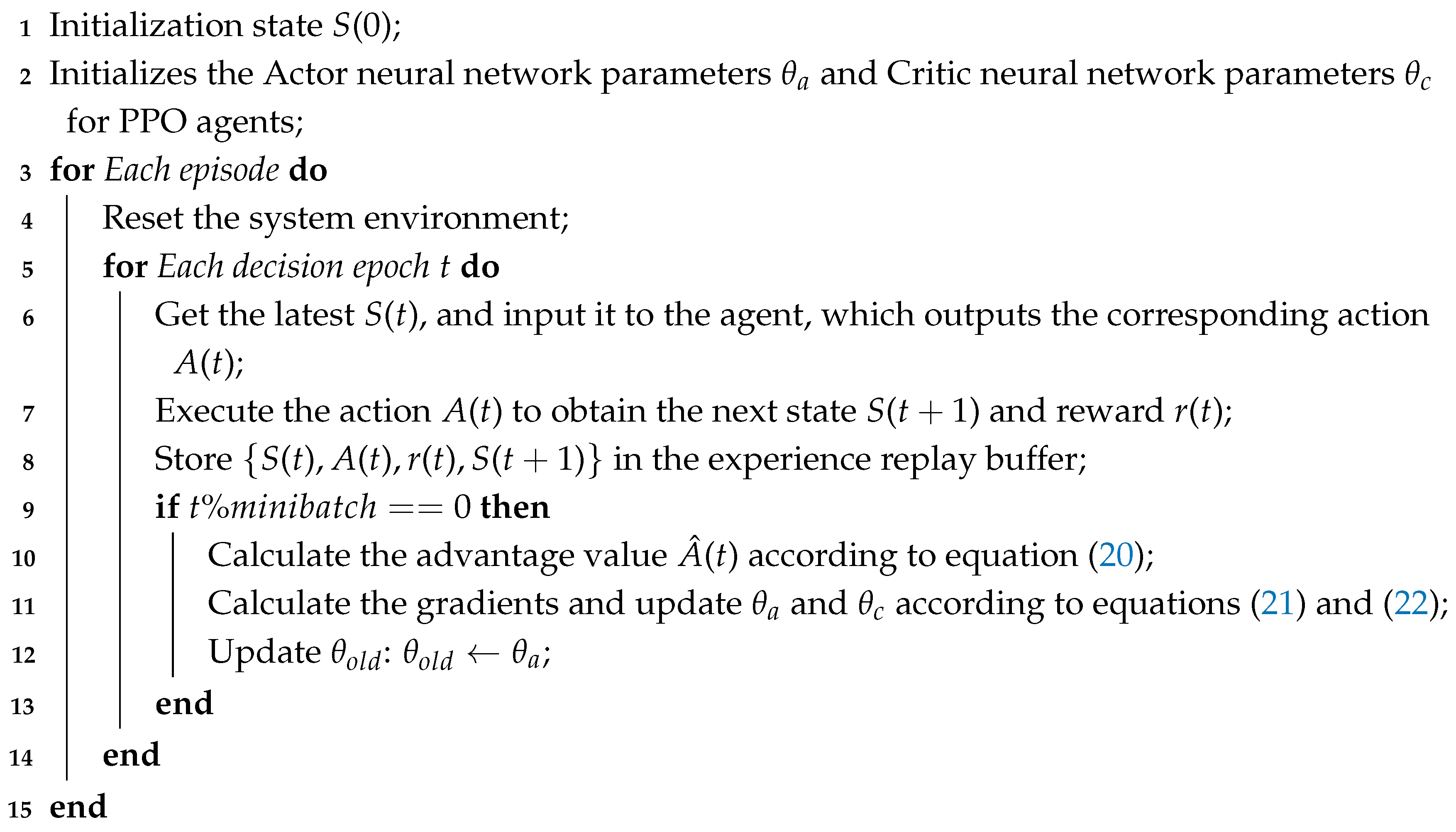

Considering the complexity and high dynamics of the scenario in this article, PPO algorithm will be used to solve the MDP problem and optimize the objective. The algorithm flow is shown in

Figure 3. In the designed algorithm, FL resources in WCPN will be scheduled and optimized. The algorithm flow is as follows:

WCPN sends the environment state to the PPO agent;

The PPO agent outputs the optimal decision and evaluation value based on the current state, and returns the decision to the WCPN environment for execution;

The WCPN environment returns the reward after executing the decision;

The PPO agent saves relevant data to the experience replay buffer;

When the amount of data in the experience replay buffer reaches a preset value, the parameters of the Actor and Critic networks in the PPO agent are updated.

3.1. MDP Modeling for Optimization Problems

The MDP process is a commonly used model for designing environmental interaction systems, and often applied for reinforcement learning and dynamic. In an MDP, an agent learns the optimal strategy through interaction with the environment to maximize its expected return.

The core idea of MDP is to model the problem as a dynamic process in which an agent needs to take actions in a constantly changing environment and adjust its behavior based on feedback from the environment. However,the environment in an MDP can be uncertain, meaning that an agent may need to take different actions to respond to different situations.

3.1.1. State

The state

includes the amount of data that each device still needs to collect upon arrival of an FL request, the amount of data collected by each device since their last response to an FL request, the signal-to-noise ratio (SINR) at the current moment, and the time interval between the last two FL requests. Therefore, the state space at decision epoch t can be expressed by

3.1.2. Action

Based on the current environmental state

, the action

adjusts the frequency of data collection for all device

, the local computation frequency, and the spectrum resources allocated for uploading the local model, i.e.,

. Similarly, the action of the decision epoch t can be denoted as

3.1.3. Reward

Considering the age of data samples and model parameters during the FL iteration process, as well as the tradeoff between computational energy consumption, transmission energy consumption, and service latency, we aim to minimize the age while ensuring that energy consumption and latency are within acceptable ranges. We cannot sacrifice computing resources and spectrum resources for reducing parameter age at the expense of a large number of data samples and model parameters. In combination with our optimization objective (

16), the goal of the reinforcement learning agent is to maximize the expected reward

. Therefore, the reward of the agent can be described in a negative form of (

15), which is:

3.2. Double Cache FL Scheduling Algorithm of Age of Parameter Base on PPO

The PPO algorithm is a reinforcement learning algorithm based on policy gradient, aiming to optimize the policy by finding the optimal set of parameters and making the best decisions to maximize expected returns. The neural network of PPO consists of Actor network and Critic network. The Critic network is a value function network which estimates the value of each state, while the Actor network calculates the probability distribution of actions under different states.

To prevent overshooting, where the policy falls into a worse-performing region and fails to provide sufficient effective information in the future, the PPO algorithm also quantifies the optimization of the policy to ensure that each update has some degree of effectiveness. By updating the policy parameters through calculating the advantage function, a new policy can become more excellent. According to the advantage estimation method proposed by Mnih et al. [

41], the Actor is run within a minibatch of logical decision slots and samples are collected for advantage estimation, which can be denoted as:

where

is the discount factor,

is the state value function, and

is the advantage function. To make up for the shortcomings of the PG algorithm, PPO algorithm introduces off-policy in parameter updates to ensure that a set of data obtained through sampling can be reused. At the same time, using a clipped alternative objective ensures the change magnitude between new and old policies. Let

represent the difference between the policy

before and after updating. The objective function of PPO can be expressed as:

where

is a hyperparameter used to limit the magnitude of policy updates. The clip function, which clips

between

, can be used to restrict the update magnitude of the policy. Additionally, the optimization objective of the Critic network is to minimize the difference between the estimated value and the actual reward, and its loss function can be represented as:

During the training process of PPO algorithm, the agent obtains the initial state

from the environment. Based on the current state, it generates a random policy distribution and samples an action to apply to the FL of WCPN and the new state and action transition sequence are obtained. With each minibatch step of data collected, the alternative loss is constructed using these data, and the Actor-Critic network parameters

and

are updated using the Adam optimizer to obtain the optimal policy parameters

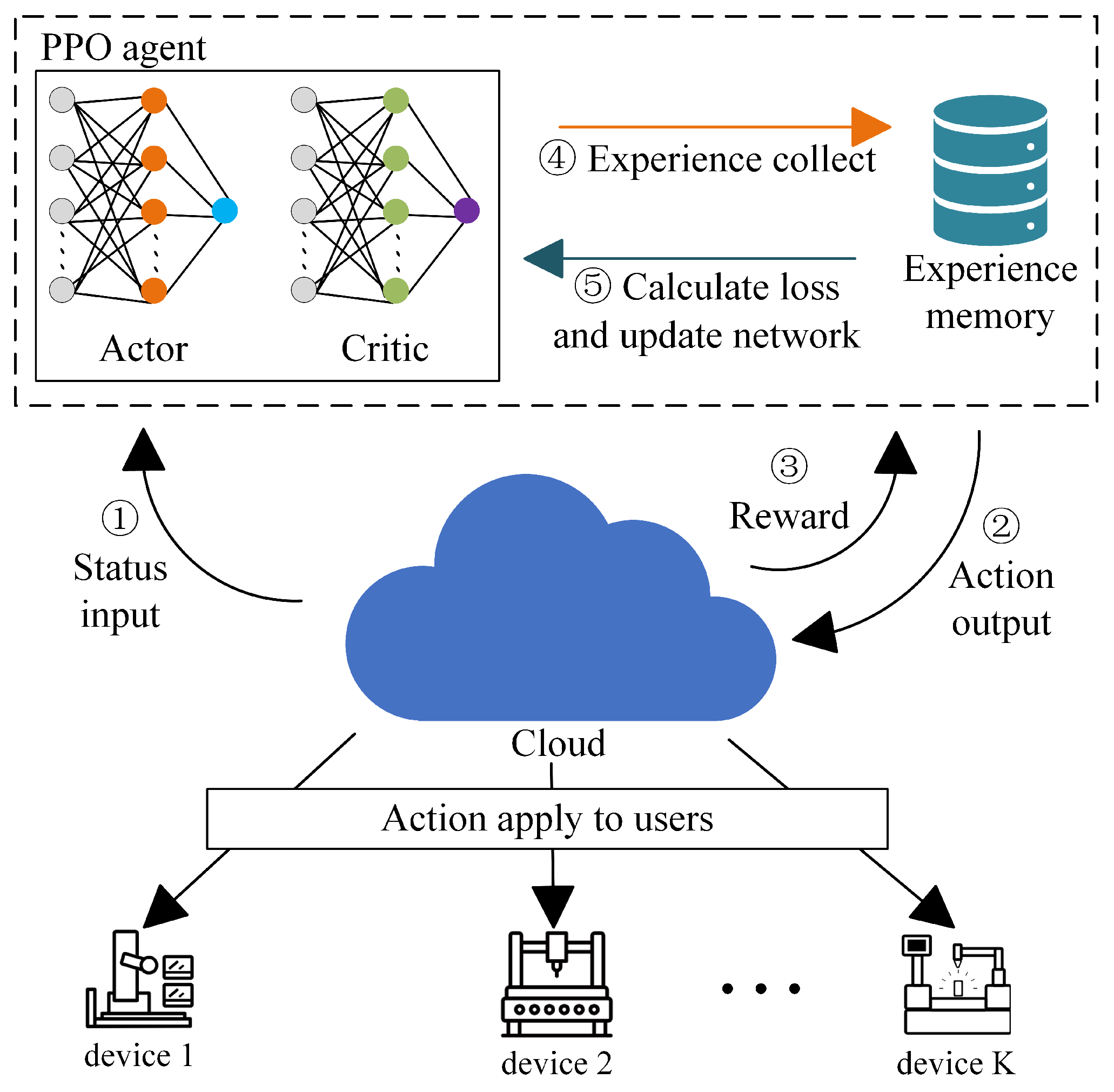

. Algorithm 1 provides pseudocode for the parameter age-aware PPO double buffer FL scheduling algorithm.

|

Algorithm 1: Parameter age-ware PPO Double Buffer FL Scheduling Algorithm |

|

4. Experiment

This section evaluates the performance of the proposed parameter-aware PPO double buffer FL scheduling algorithm through experimental testing, and sets up multiple comparison schemes to verify the correctness and superiority of the proposed scheme.

4.1. Experiment Setting

In this paper, the PPO algorithm is built using the TensorFlow neural network framework. The Actor network consists of an input layer, three hidden layers, and one output layer, while the Critic network consists of an input layer, two hidden layers, and one output layer. The PPO algorithm is set with the clipping parameter , the learning rate for the Actor network , the learning rate for the Critic network , and the discount factor . The maximum number of training rounds in RL is , each round has an iteration of , and the minibatch size in PPO algorithm is 64.

In addition, we also validates the FL performance of the age-aware PPO double buffer scheduling algorithm using a real dataset MNIST. MNIST dataset consists of handwritten digit images and labels from 0 to 9. It includes 60,000 training images and 10,000 testing images. During simulation validation, devices use convolutional neural networks as the machine learning model for FL. They randomly collect data samples from MNIST data and conduct local training. Following the introduction in

Section 2, this paper assumes that the arrival rate of FL requests follows a Poisson distribution. Considering a scenario where a central server and

devices jointly complete the FL task, the main environment parameters defined in

Table 1 are shown below.

4.2. Numerical Results

We set up multiple comparison schemes to verify the correctness and superiority of the proposed solution from different perspectives in simulation. There are a total of six different comparison schemes, and the meanings of these comparison schemes are as follows: (i) OnlyModelCache: Set only the model cache buffer in the central server to save models for dropped devices; (ii) OnlyLocalCache: Set only the local data cache buffer for each device to pre-cache data samples needed for local training; (iii) WithoutAnyCache: Do not set any cache buffers, which is the case of FL in a general scenario; (iv) FixFcol: Fix the device’s data collection frequency and optimize only the device’s computation frequency and allocated bandwidth size; (v) FixFcom: Fix the ratio of the device’s computation frequency used for data collection and local computing to the maximum available computation frequency, and optimize only the device’s data collection frequency and allocated bandwidth size; (vi) FixBandwidth: Fix the device’s allocated bandwidth size and optimize only the device’s data collection frequency and computation frequency.

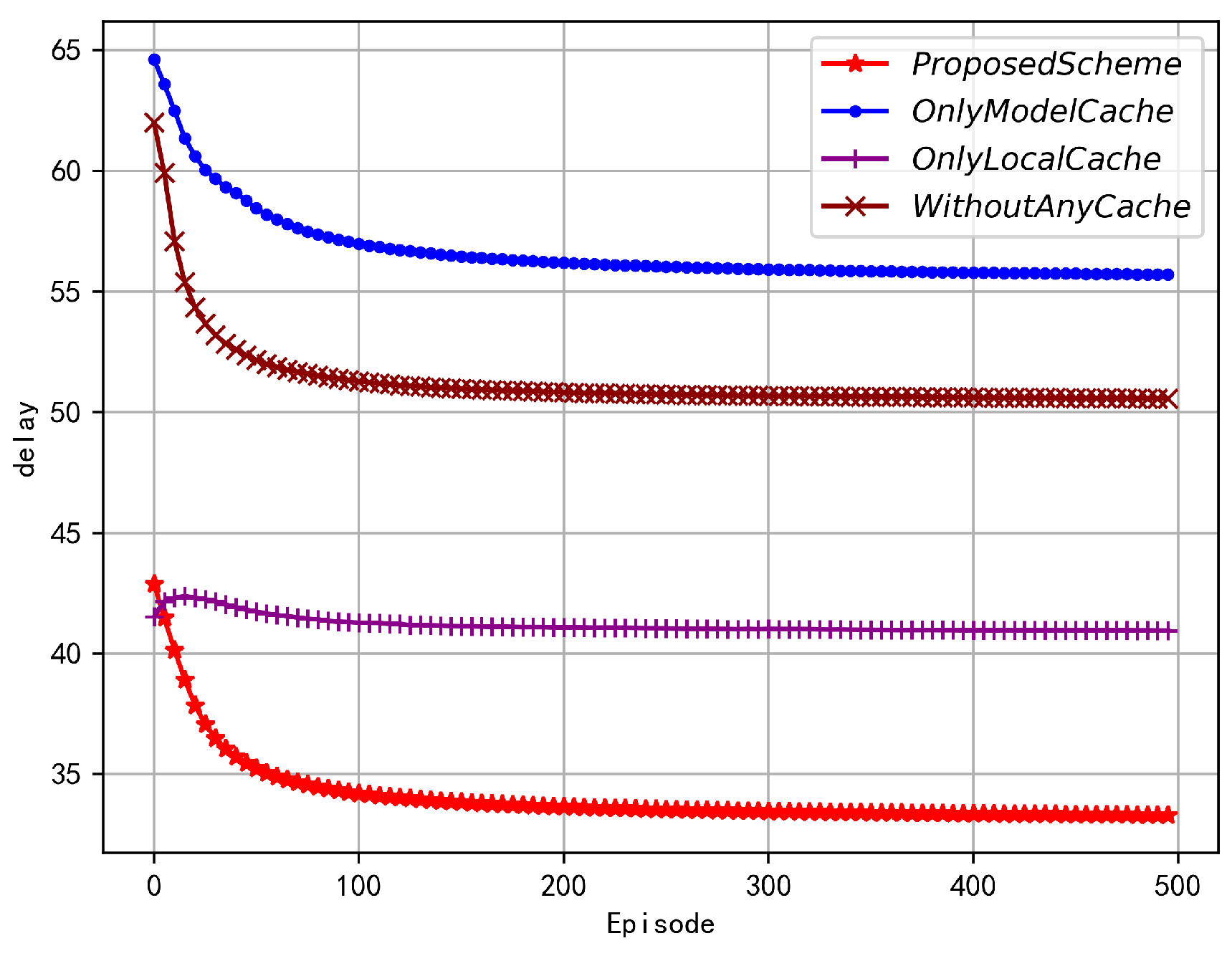

As shown in

Figure 4, as the number of iterations increases, all four algorithms can effectively reduce the FL service delay. From the reward equation(

19), it can be seen that the FL delay is also an important objective in optimization. As the PPO agent solves for maximizing the reward, it also considers minimizing the FL delay, which is consistent with the goal of minimizing FL delay set in this paper. Two schemes with local data caching buffers have the lowest FL service delay. The performance of only model caching and no caching scheme is almost the same, indicating that model caching does not have a negative impact on FL service delay. The simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of data caching buffers in reducing FL service delay. Although adding a model caching buffer will not significantly affect FL service delay, on the other hand, it can provide more device machine learning models for the global model, resulting in better global model performance and stronger generalization ability.

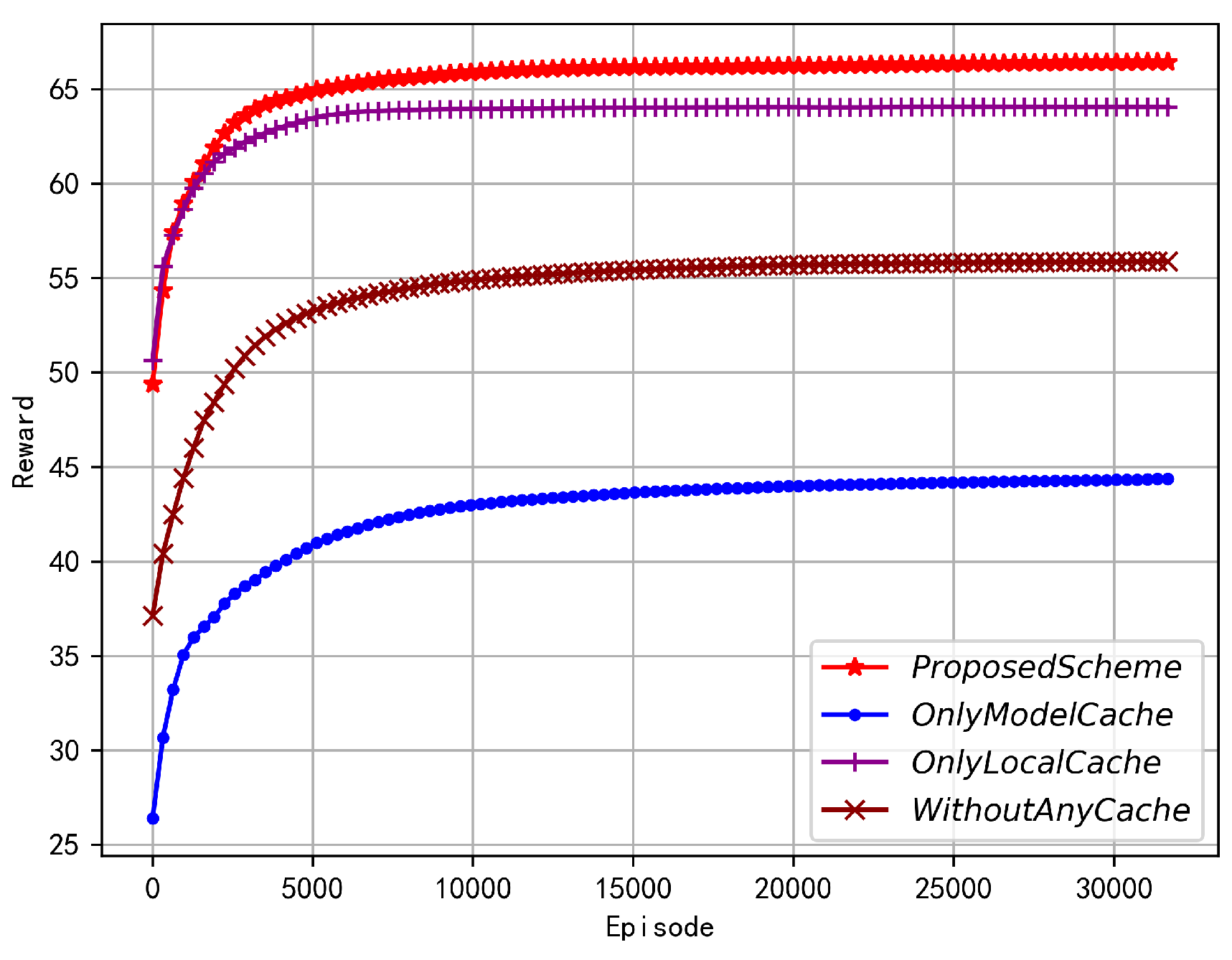

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the agent’s reward and the number of iterations for the four schemes. Since the proposed scheme and the local data caching scheme can significantly reduce the service delay of FL, these two schemes also have obvious advantages in terms of rewards. Although only model caching and no caching schemes collect data after receiving FL requests, their data is the freshest, and the age of parameters involved in local training will be very low. However, the performance of these two schemes in terms of FL service delay is worse, as fresh data cannot offset the negative impact caused by high service delay, so their rewards are also lower.

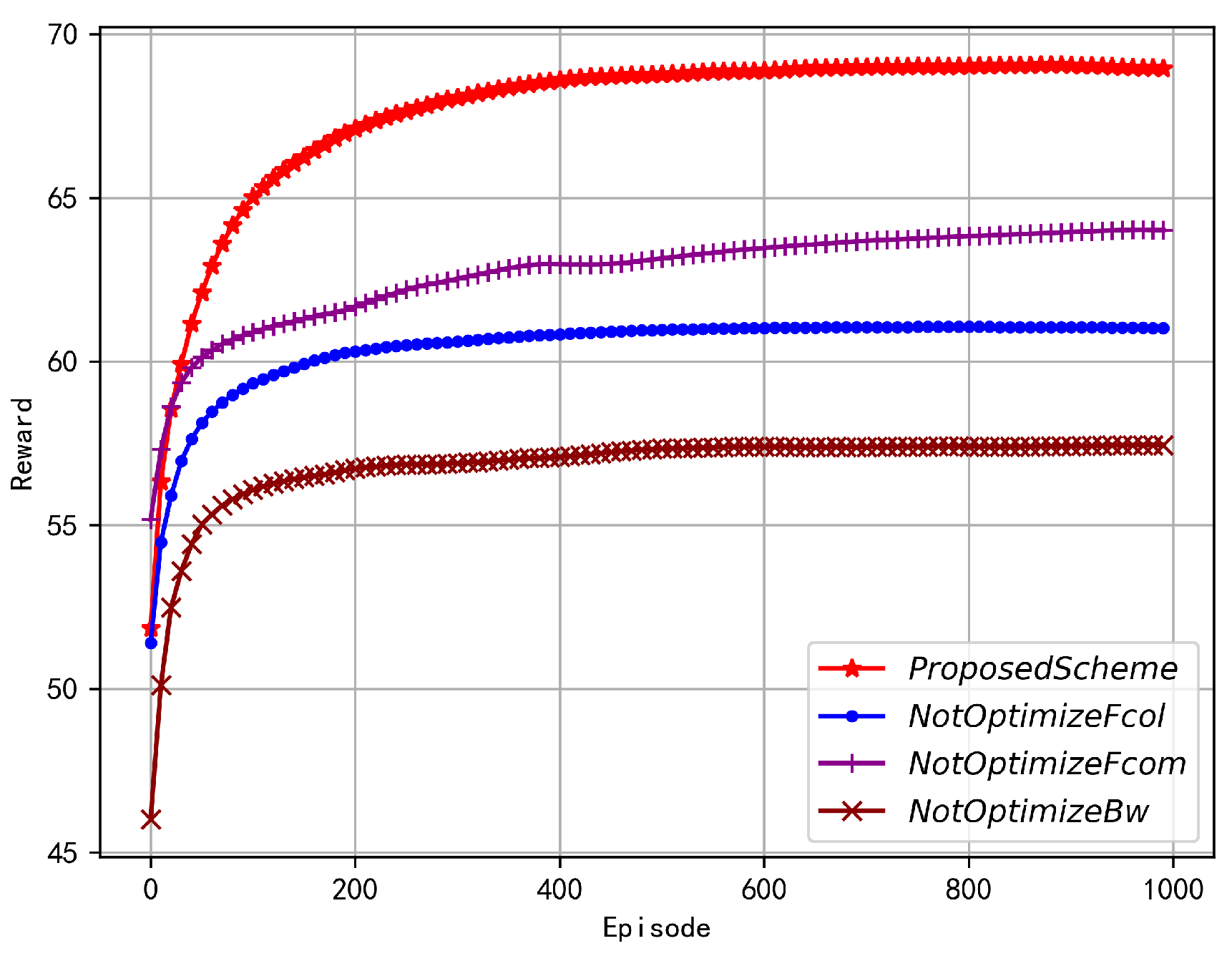

As shown in

Figure 6, as the number of iterations increases, the rewards for all four optimization schemes gradually increase and tend to converge. According to the definition in equation(

19), the optimization objective defined by equation(

15), is a negative exponential term of the reward, which means that the maximum reward of the agent corresponds to the minimization of equation(

15). This is consistent with the goal of minimizing FL delay set in this paper. Compared with the other three schemes, the proposed scheme can obtain the largest reward. As the optimization variables in the proposed scheme are relatively more, its convergence speed is slightly slower, but its reward value has a significant advantage relative to other schemes. Other schemes lack optimization of necessary variables, although they can also converge to good rewards, their final results are far worse than those proposed in this paper. In conclusion, the joint optimization scheme of the three variables proposed in this paper is reasonable, correct and significantly superior.

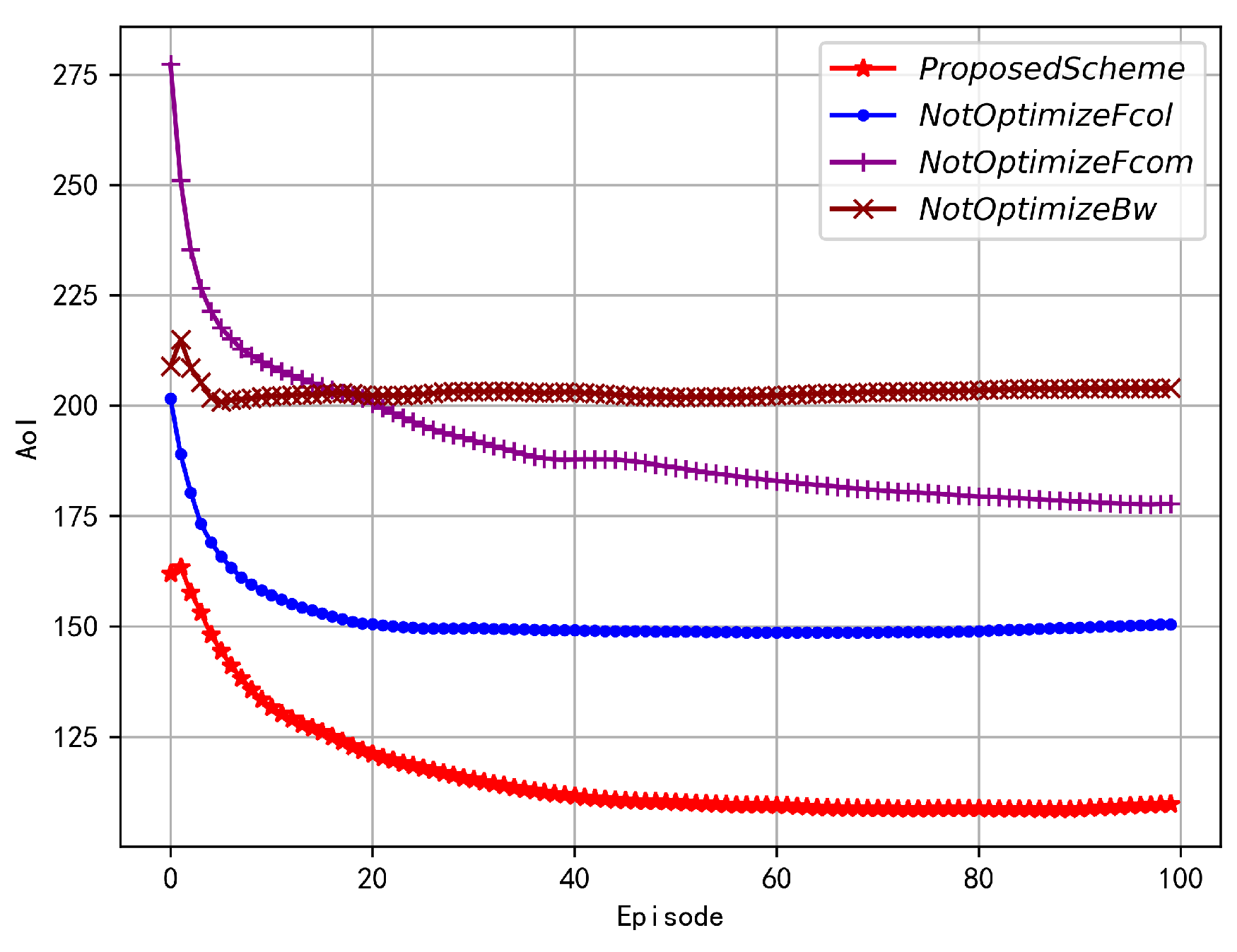

As shown in

Figure 7, with the increase of iteration number, all four optimization schemes can gradually reduce global parameter age and converge. Parameter age is an important indicator of the convergence performance of the agent as an optimization objective in equation(

15). Similarly, due to the relatively more optimization variables in the proposed scheme, its corresponding parameter age optimization declines at a slower convergence speed, but it can still reduce global parameter age to a very small value. Fixed collection frequency at a larger value can maintain smaller local data parameter age, but this scheme cannot make adaptive adjustments to the randomness of FL requests, so its parameter age will be slightly smaller than that of the proposed scheme. In addition, this will also bring great energy consumption, which is why its parameter age is smaller than that of fixed computation frequency but reward is very close to it. Fixed device’s computation frequency makes the time spent by each device collecting unit data relatively fixed, but FL requests arrive randomly and require comprehensive consideration of the overall system energy consumption. The scope of adaptive adjustment of data collection frequency is limited and can only be controlled to a lower collection frequency, resulting in larger data sample age. Overall, adjusting either data collection frequency or computation frequency alone cannot effectively reduce local sample parameter age, and both need to be dynamically adjusted together to achieve optimal results. Furthermore, fixing the bandwidth size allocated to each device is influenced by the dragger under high dynamic communication conditions, causing the central server to wait for the dragger to complete FL service before aggregating, during which all device’s parameter ages are aging together, leading to extremely poor overall parameter age performance.

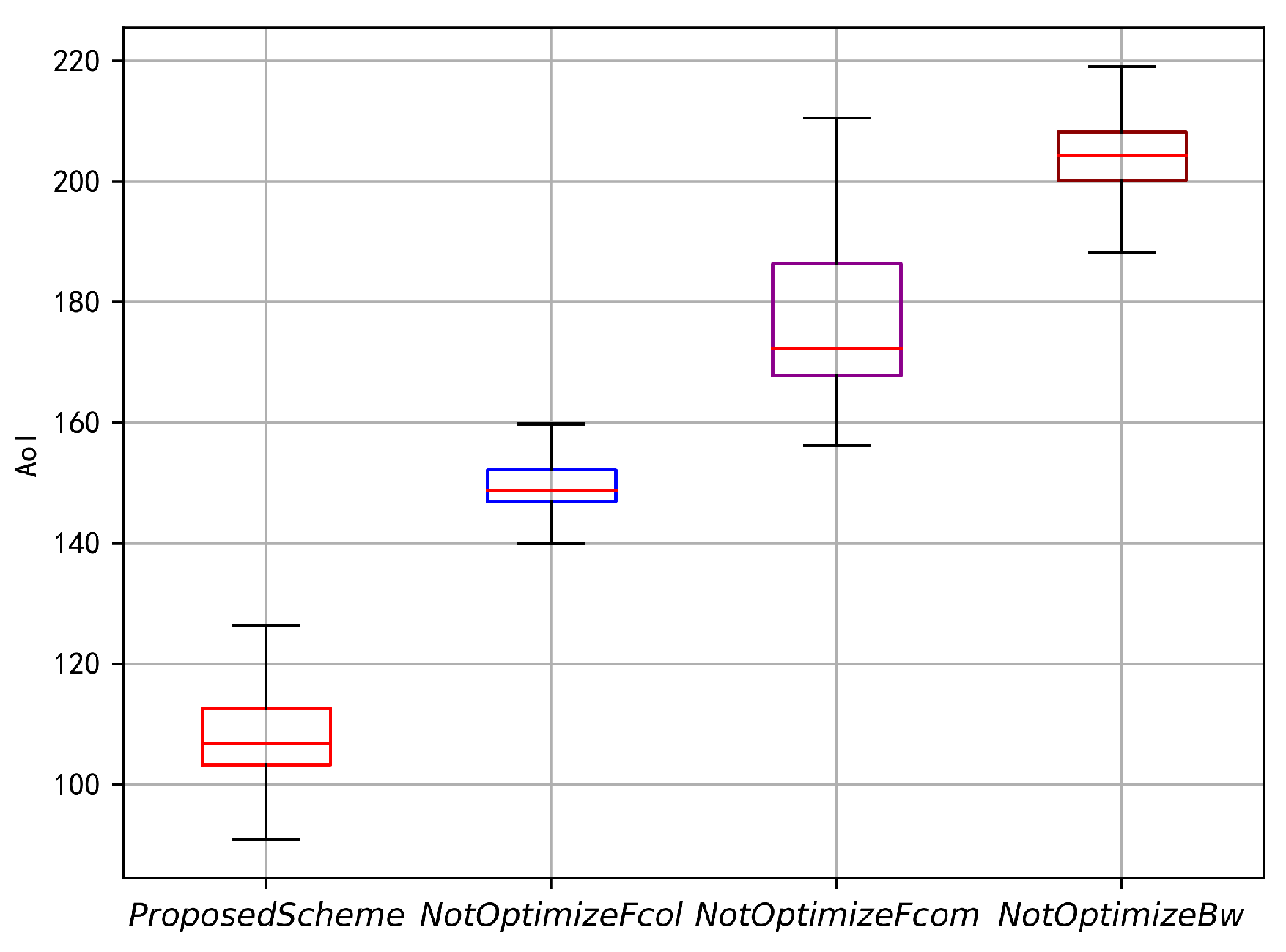

Figure 8 compares the boxplot of global parameter age under four schemes, including the proposed scheme, the fixed data collection frequency scheme, the fixed device computation frequency scheme, and the fixed device bandwidth scheme. From the figure, it can be seen that the proposed scheme performs the best in terms of global parameter age minimization, and its overall stability is relatively good with a smaller range for the upper and lower bounds of global parameter age. This proves that the proposed scheme not only performs the best in terms of global parameter age optimization but also has good stability, further validating the correctness and superiority of the scheme.

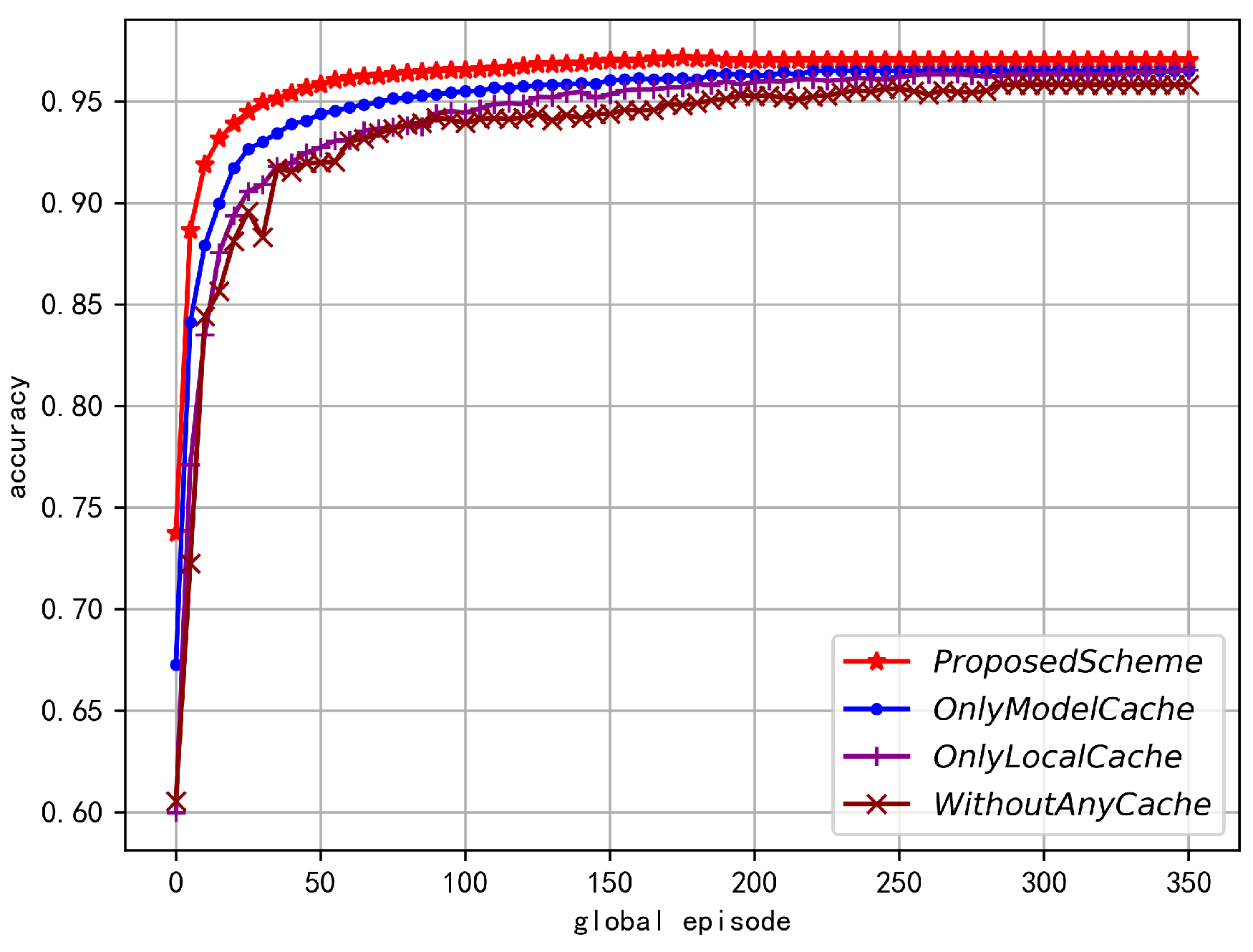

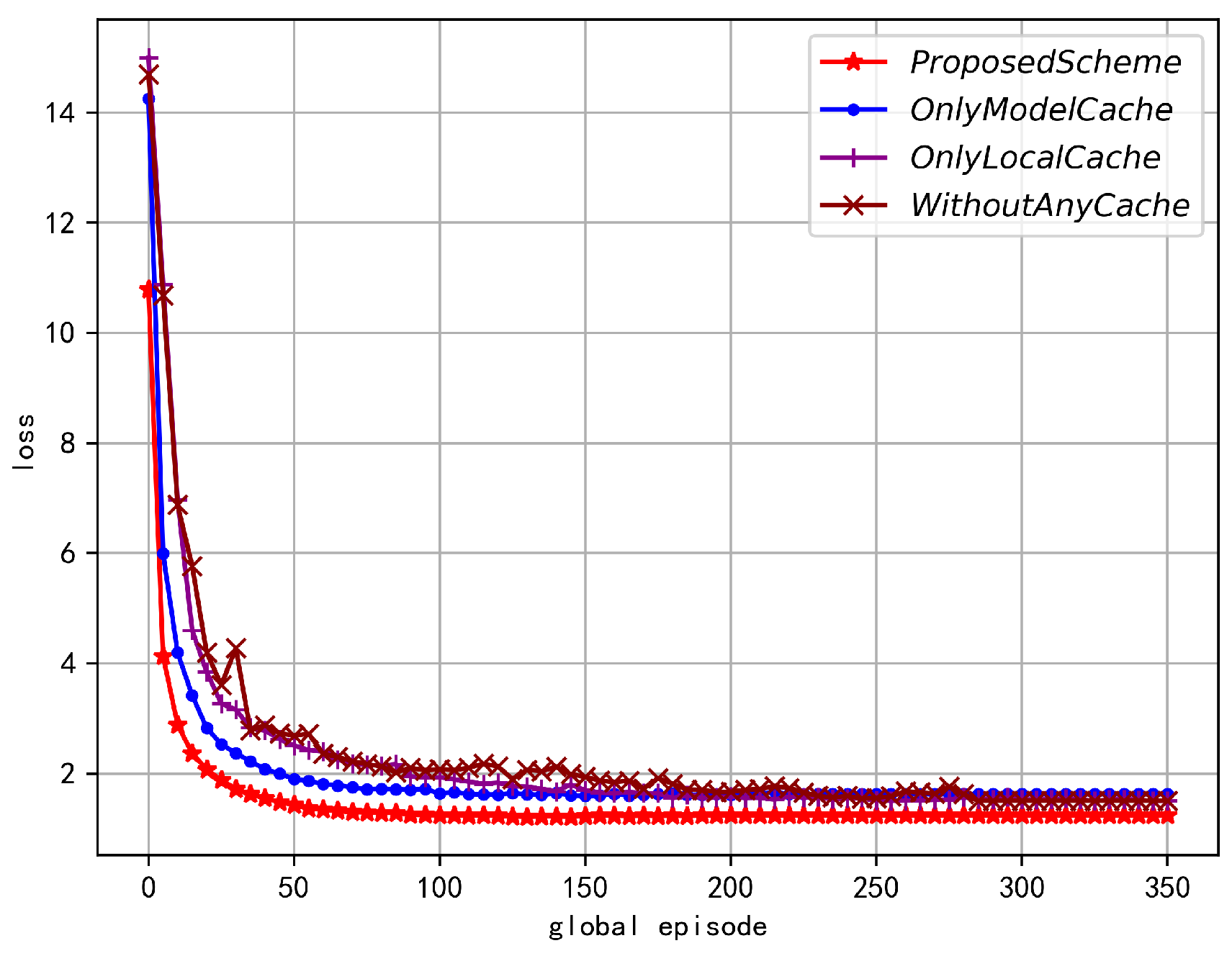

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 compare the accuracy and error of FL under four schemes, including the proposed scheme, the only model cache scheme, the only local data cache scheme, and the no-cache scheme. From the figures, it can be seen that these four schemes can gradually increase their FL accuracy and converge as the global iteration number increases. The convergence trend of these schemes is slightly different due to outdated data reducing the global model’s convergence speed. As analyzed in [

26], due to gradient coherence, if the current gradient is consistent with the gradient direction of the recent period, then the current update is valid; if the current update direction is opposite to the historical direction, then one of the updates (current or historical) is a wrong update, hindering model convergence. The proposed scheme converges the fastest because its global parameter age performs best, which is conducive to global model convergence. The other three comparison schemes converge relatively slowly, but with increasing iterations, these schemes can all converge to roughly the same level.