Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

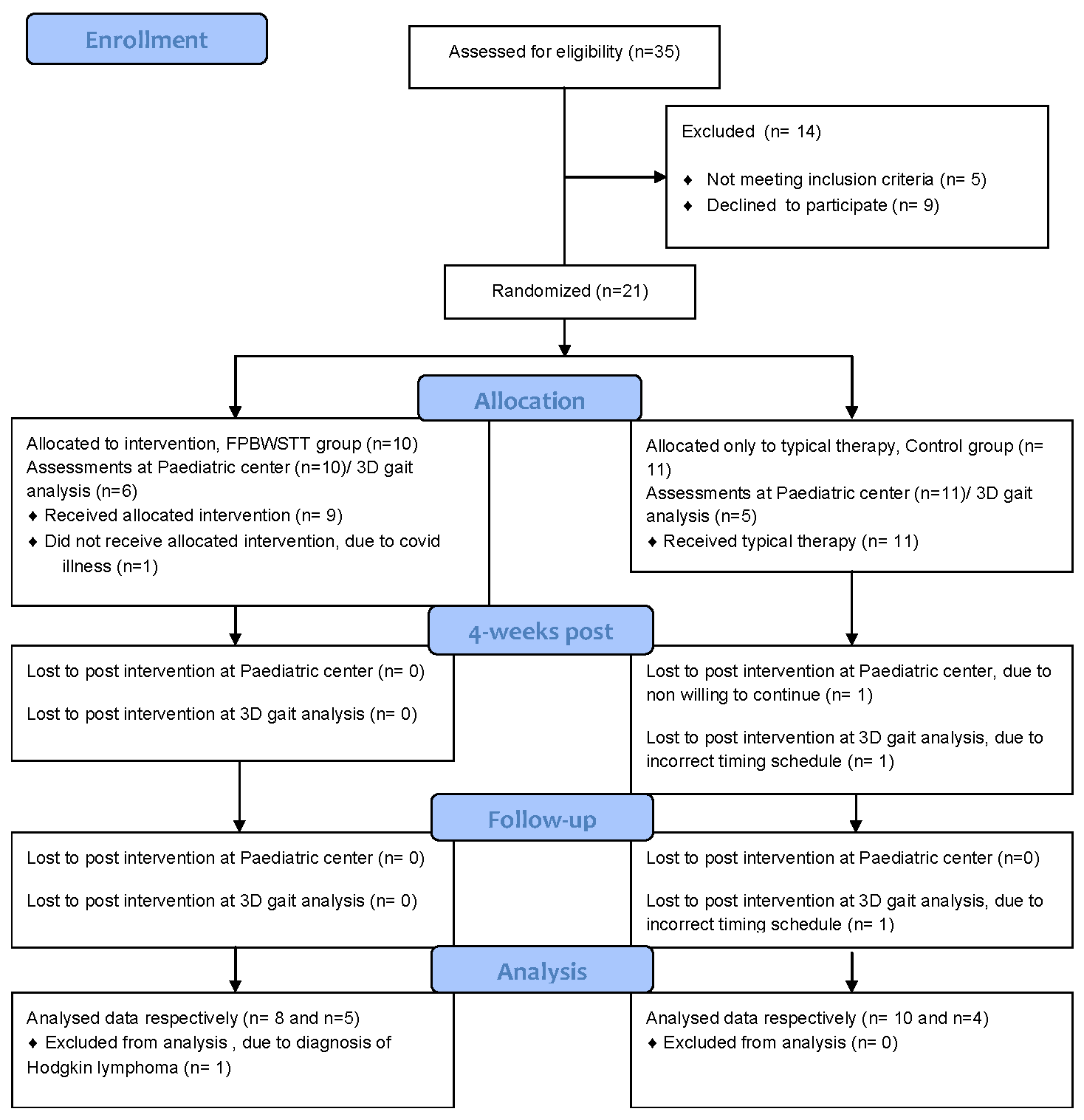

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

3.2. Primary outcomes: Domains D and E of the GMFM-88(%)

3.3. Secondary outcomes

3.3.1. Secondary variables from 3D Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Musselman, K.E.; Stoyanov, C.T.; Marasigan, R.; Jenkins, M.E.; Konczak, J.; Morton, S.M.; Bastian, A.J. Prevalence of ataxia in children: a systematic review. Neurology 2014, 82, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, H.; Cassidy, E.; Bunn, L.; Kumar, R.; Pizer, B.; Lane, S.; Carter, B. Exercise and Physical Therapy Interventions for Children with Ataxia: A Systematic Review. Cerebellum 2019, 18, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavone, P.; Praticò, A.D.; Pavone, V.; Lubrano, R.; Falsaperla, R.; Rizzo, R.; Ruggieri, M. Ataxia in children: early recognition and clinical evaluation. Ital J Pediatr. 2017, 43, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepoura, A.; Lampropoulou, S.; Galanos, A.; Papadopoulou, M.; Sakellari, V. Scale for Assessment and Rating Ataxia (SARA) in Children with Ataxia: Greek Cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties. Open Access Journal of Neurology & Neurosurgery 2023, 18, e555976. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Hübsch, T.; du Montcel, S.T.; Baliko, L.; Berciano, J.; Boesch, S.; Depondt, C.; Giunti, P.; Globas, C.; Infante, J.; Kang, J.S.; Kremer, B.; Mariotti, C.; Melegh, B.; Pandolfo, M.; Rakowicz, M.; Ribai, P.; Rola, R.; Schöls, L.; Szymanski, S.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.; Dürr, A.; Klockgether, T.; Fancellu, R. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006, 66, 1717–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, W.B.; Pedroso, J.L.; Souza, P.V.; Albuquerque, M.V.; Barsottini, O.G. Non-progressive cerebellar ataxia and previous undetermined acute cerebellar injury: a mysterious clinical condition. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2015, 73, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzeri, D.; Bettinelli, M.S.; Biffi, E.; Rossi, F.; Pellegrini, C.; Orsini, N.; Recchiuti, V.; Massimino, M.; Poggi, G. Application of the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) in pediatric oncology patients: A multicenter study. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020, 37, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.; Yau, W.Y.; O'Connor, E.; Houlden, H. Spinocerebellar ataxia: an update. J Neurol. 2019, 266, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinlin, M. Non-progressive congenital ataxias. Brain Dev. 1998, 20, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, E.; Mazzà, C.; McNeill, A. A systematic review of the gait characteristics associated with Cerebellar Ataxia. Gait Posture. 2018, 60, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, S.C.; Hocking, D.R.; Georgiou-Karistianis, N.; Murphy, A.; Delatycki, M.B.; Corben, L.A. Sensitivity of spatiotemporal gait parameters in measuring disease severity in Friedreich ataxia. Cerebellum. 2014, 13, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peri, E.; Panzeri, D.; Beretta, E.; Reni, G.; Strazzer, S.; Biffi, E. Motor Improvement in Adolescents Affected by Ataxia Secondary to Acquired Brain Injury: A Pilot Study. Biomed Res Int. 2019, 2019, 8967138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasco, G.; Gazzellini, S.; Petrarca, M.; Lispi, M.L.; Pisano, A.; Zazza, M.; Della Bella, G.; Castelli, E.; Bertini, E. Functional and Gait Assessment in Children and Adolescents Affected by Friedreich's Ataxia: A One-Year Longitudinal Study. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0162463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, D.L.; DeJong, S.L. A systematic review of the effectiveness of treadmill training and body weight support in pediatric rehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2009, 33, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Rueda, F.; Aguila-Maturana, A.M.; Molina-Rueda, M.J.; Miangolarra-Page, J.C. Pasarelarodante con o sin sistema de suspension del peso corporal enninos con paralisis cerebral infantil: revision sistematica y metaanalisis [Treadmill training with or without partial body weight support in children with cerebral palsy: systematic review and meta-analysis]. Revista de Neurologia. 2010, 51, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, G.; Cai, X.; Xu, K.; Tian, H.; Meng, Q.; Ossowski, Z.; Liang, J. Which gait training intervention can most effectively improve gait ability in patients with cerebral palsy? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2023, 13, 1005485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin-Gudiol, M.; Bagur-Calafat, C.; Girabent-Farrés, M.; Hadders-Algra, M.; Mattern-Baxter, K.; Angulo-Barroso, R. Treadmill interventions with partial body weight support in children under six years of age at risk of neuromotor delay: a report of a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013, 49, 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson, K.F.; Moreau, N.; Bodkin, A.W. Short-burst interval treadmill training walking capacity and performance in cerebral palsy: a pilot study. Dev Neurorehabil. 2019, 22, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamacher, D.; Herold, F.; Wiegel, P.; Hamacher, D.; Schega, L. Brain activity during walking: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015, 57, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín Valenzuela, C.; Moscardó, L.D.; López-Pascual, J.; Serra-Añó, P.; Tomás, J.M. Effects of Dual-Task Group Training on Gait, Cognitive Executive Function, and Quality of Life in People With Parkinson Disease: Results of Randomized Controlled DUALGAIT Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1849–1856e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.R.; Chen, Y.C.; Lee, C.S.; Cheng, S.J.; Wang, R.Y. Dual-task-related gait changes in individuals with stroke. Gait Posture. 2007, 25, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhinidi, E.I.; Ismaeel, M.M.; El-Saeed, T.M. Effect of dual-task training on postural stability in children with infantile hemiparesis. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016, 28, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.Y.; Lee, E.J.; Kwon, H.Y. The effects of dual-task training on balance and gross motor function in children with spastic diplegia. J Exerc Rehabil. 2021, 17, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, I.; Poljac, E.; Müller, H.; Kiesel, A. Cognitive structure, flexibility, and plasticity in human multitasking-An integrative review of dual-task and task-switching research. Psychol Bull. 2018, 144, 557–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoura, A.; Lampropoulou, S.; Galanos, A.; Papadopoulou, M.; Sakellari, V. Study protocol of a randomised controlled trial for the effectiveness of a functional partial body weight support treadmill training (FPBWSTT) on motor and functional skills of children with ataxia. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e056943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herson, J.; Wittes, J. The Use of Interim Analysis for Sample Size Adjustment. Drug Information Journal. 1993, 27, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.K.; Kim, J.H. Statistical data preparation: management of missing values and outliers. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küper, M.; Döring, K.; Spangenberg, C.; Konczak, J.; Gizewski, E.R.; Schoch, B.; Timmann, D. Location and restoration of function after cerebellar tumor removal-a longitudinal study of children and adolescents. Cerebellum. 2013, 12, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, K.J.; Taylor, N.F.; Graham, H.K. A randomized clinical trial of strength training in young people with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003, 45, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern-Baxter, K.; McNeil, S.; Mansoor, J.K. Effects of home-based locomotor treadmill training on gross motor function in young children with cerebral palsy: a quasi-randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013, 94, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, F.A.; Petrarca, M.; Beretta, E.; Strazzer, S.; Piccinini, L.; Maghini, C.; Panzeri, D.; Corbetta, C.; Morganti, R.; Reni, G.; Castelli, E.; Frascarelli, F.; Colazza, A.; Cordone, G.; Biffi, E. Minimum Clinically Important Difference of Gross Motor Function and Gait Endurance in Children with Motor Impairment: A Comparison of Distribution-Based Approaches. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, 2794036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Shen, I.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Liu, W.Y.; Chung, C.Y. Validity, responsiveness, minimal detectable change, and minimal clinically important change of Pediatric Balance Scale in children with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2013, 34, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleim, J.A.; Jones, T.A. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008, 51, S225–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols-Larsen DS, Kegelmeyer DA, Buford JA, Kloos AD, Heathcock JC, Michele Basso D. Neurologic Rehabilitation : Neuroscience and Neuroplasticity in Physical Therapy Practice. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Schatton, C.; Synofzik, M.; Fleszar, Z.; Giese, M.A.; Schöls, L.; Ilg, W. Individualized exergame training improves postural control in advanced degenerative spinocerebellar ataxia: A rater-blinded, intra-individually controlled trial. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017, 39, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz-Hübsch, T.; Fimmers, R.; Rakowicz, M.; Rola, R.; Zdzienicka, E.; Fancellu, R.; Mariotti, C.; Linnemann, C.; Schöls, L.; Timmann, D.; Filla, A.; Salvatore, E.; Infante, J.; Giunti, P.; Labrum, R.; Kremer, B.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.; Baliko, L.; Melegh, B.; Depondt, C.; Schulz, J.; du Montcel, S.T.; Klockgether, T. Responsiveness of different rating instruments in spinocerebellar ataxia patients. Neurology. 2010, 74, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilg, W.; Schatton, C.; Schicks, J.; Giese, M.A.; Schöls, L.; Synofzik, M. Video game-based coordinative training improves ataxia in children with degenerative ataxia. Neurology. 2012, 79, 2056–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbecque, E.; Schepens, K.; Theré, J.; Schepens, B.; Klingels, K.; Hallemans, A. The Timed Up and Go Test in Children: Does Protocol Choice Matter? A Systematic Review. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2019, 31, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini-Panisson, R.D.; Donadio, M.V. Timed "Up & Go" test in children and adolescents. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2013, 31, 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, D.; Hickey, C.; Delahunt, E.; Walsh, M.; OʼBrien, T. Six-Minute Walk Test in Children With Spastic Cerebral Palsy and Children Developing Typically. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2016, 28, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.K.; Nelson, M.; Brooks, D.; Salbach, N.M. Validation of stroke-specific protocols for the 10-meter walk test and 6-minute walk test conducted using 15-meter and 30-meter walkways. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2020, 27, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.C.; Kirk, J.; Stewart, G.; Cook, K.; Weir, D.; Marshall, A.; Leahey, L. Contributing factors to muscle weakness in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003, 45, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darras, N.; Tziomaki, M.; Pasparakis, D. Motion Graph Deviation Index (MGDI): An index that enhances objectivity in clinical motion graph analysis. ΕΕΧOΤ 2015, 67, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima, A.; Yoshida, K.; Genno, H.; Murata, A.; Matsuzawa, S.; Nakamura, K.; Nakamura, A.; Ikeda, S. Clinical assessment of standing and gait in ataxic patients using a triaxial accelerometer. Cerebellum Ataxias. 2015, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chini, G.; Ranavolo, A.; Draicchio, F.; Casali, C.; Conte, C.; Martino, G.; Leonardi, L.; Padua, L.; Coppola, G.; Pierelli, F.; Serrao, M. Local Stability of the Trunk in Patients with Degenerative Cerebellar Ataxia During Walking. Cerebellum. 2017, 16, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | FPBWSTT Group | Control Group | p-value |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 14.69±2.05 | 13.45±2.73 | 0.304 |

| Sex, male/female | 7(87.5%)/1(12.5%) | 7(70%)/3(30%) | 0.588 |

| Weight (kg), mean±SD | 41.56±8.79 | 46.55±14.53 | 0.407 |

| Height(cm), mean±SD | 157.38±11.17 | 151.90±14.67 | 0.397 |

| BMI, mean±SD | 16.86±2.20 | 19.72±3.56 | 0.058 |

| Type of ataxia, non-P/P | 7(87.5%)/1(12.5%) | 9(90%)/1(10%) | 1.000 |

| GMFCS, II/III/IV | 6(75%)/1(12.5%)/1(12.5%) | 7(70%)/2(20%)/1(10%) | 0.909 |

| Laterality, right/left | 8(100%)/0(0%) | 9(90%)/1(10%) | 1.000 |

| Child’s quality of life questionnaire | |||

| Friends-Family, mean±SD | 7.18±0.92 | 6.81±0.82 | 0.375 |

| Participation, mean±SD | 6.06±2.31 | 5.65±1.79 | 0.675 |

| Communication, mean±SD | 6.58±1.28 | 6.00±1.50 | 0.395 |

| Use of limbs, mean±SD | 5.99±1.78 | 6.23±1.62 | 0.683 |

| Self-care, median±IR | 7.00±0.0 | 7.00±0.0 | 0.537 |

| Equipment, mean±SD | 4.21±1.38 | 4.21±0.76 | 1.00 |

| Pain-discomfort mean±SD | 2.98±0,77 | 2.98±0.93 | 0.991 |

| Sense of happiness median±IR | 7.00±1.0 | 7.00±0.5 | 0.573 |

| Assistance with questionnaire completion, mean±SD | 2.38±1.06 | 2.40±1.07 | 0.961 |

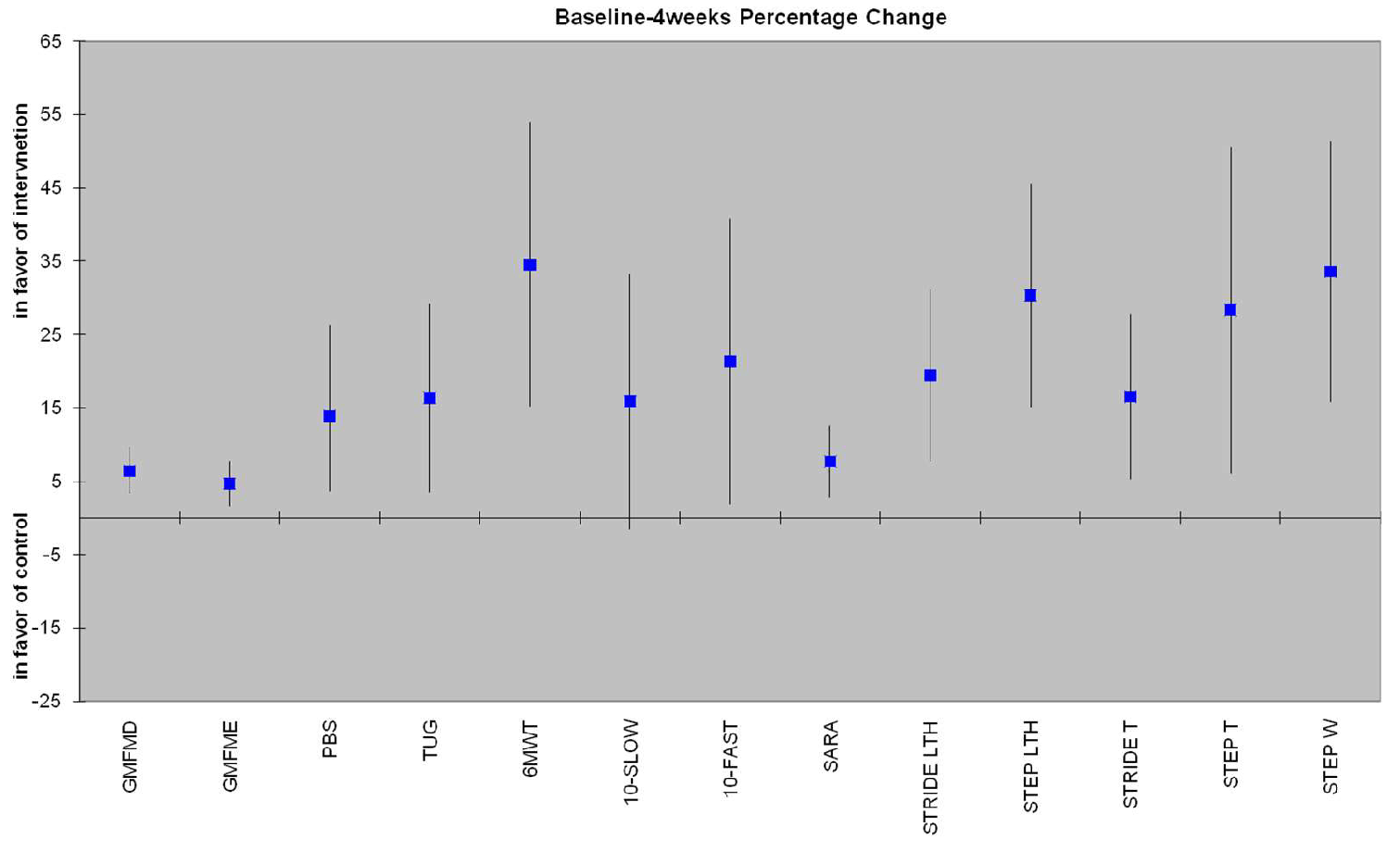

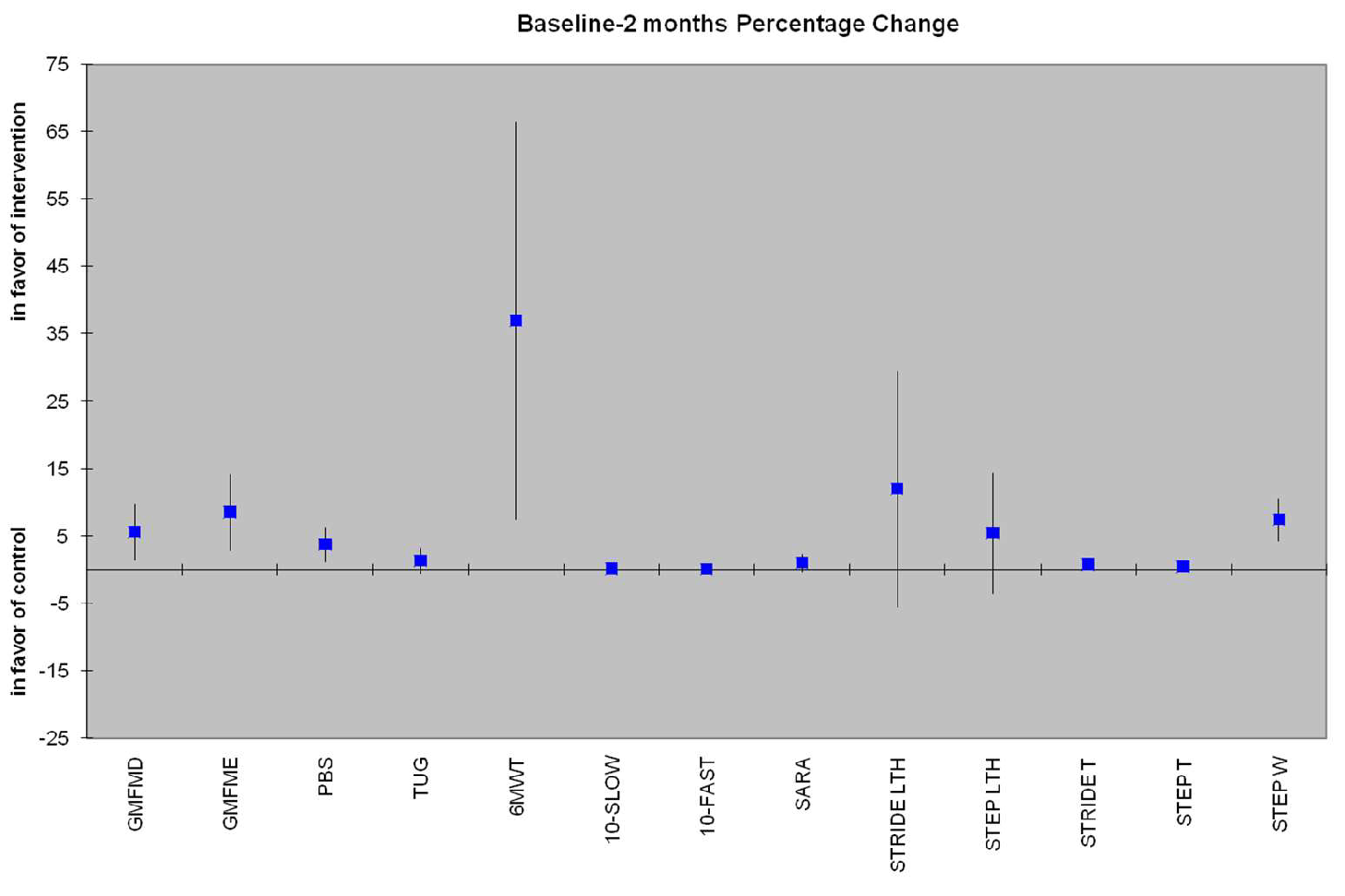

| Secondary Outcome |

4-Week Mean Difference (95% CI) |

p-value | 2-Month Mean Difference (95% CI) | p-value2 |

| PBS | 3.73 (1.13 - 6.33) | 0.008 | 3.85 (-0.14 to 7.71) | 0.05 |

| TUG (sec) | 2.19 (0.7 - 3.67) | 0.007 | 1.29 (-0.53 to 3.10) | 0.151 |

| 10MWT-SLOW (m/sec) | 0.07 (0.04 - 0.18) | 0.193 | 0.05 (0.05 - 0.15) | 0.307 |

| 10MWT-FAST (m/sec) | 0.19 (0 - 0.38) | 0.046 | 0.04 (-0.12 to 0.21) | 0.620 |

| 6MWT (m) | 56.09 (29.22 - 82.96) | <0.005 | 36.92 (7.34 - 66.50) | 0.018 |

| SARAgr | 1.22 (0.44 - 2.01) | 0.005 | 1.00 (-0.31 to 2.34) | 0.125 |

| Step Length (cm) | 8.84 (1.67 - 16.01) | 0.019 | 5.36 (-3.64 to 14.35) | 0.224 |

| Stride Length (cm) | 8.29 (-3.98 to 20.57) | 0.170 | 12 (-5.52 to 29.54) | 0.165 |

| Step Time (sec) | 0.38 (0.01 - 0.74) | 0.043 | 0.45 (0.01 - 0.90) | 0.048 |

| Stride Time (sec) | 0.45 (0.16 - 0.75) | 0.005 | 0.77 (0.05 - 1.49) | 0.038 |

| Step Width (cm) | 6.74 (4.20 - 9.29) | <0.005 | 7.41 (4.18 - 10.64) | <0.005 |

| STEP LENGTH | STRIDE LENGTH | ||||||

| Groups | Time | Time | |||||

| Baseline | 4-week | 2months | Baseline | 4-week | 2months | ||

| mean±SD | mean±SD | mean±SD | mean±SD | mean±SD | mean±SD | ||

| FPBWSTT | 22.85±7.56 | 28.19±8.69* | 27.49±8.65 | 47.72±12.74 | 54.79±14.69 | 58.16±18.66 | |

| Control | 38.01±7.04 | 35.99±9.63 | 32.88±7.00 | 72.29±17.77 | 68.51±18.27 | 64.57±16.63 | |

| Comparison between groups by time | p<0.005 | p=0.094 | p=0.163 | p=0.005 | p=0.104 | p=0.453 | |

| Interaction between group and time | F(2.32)=6.94, p<0.005 | F(2.32)=6.34, p=0.005 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).