Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

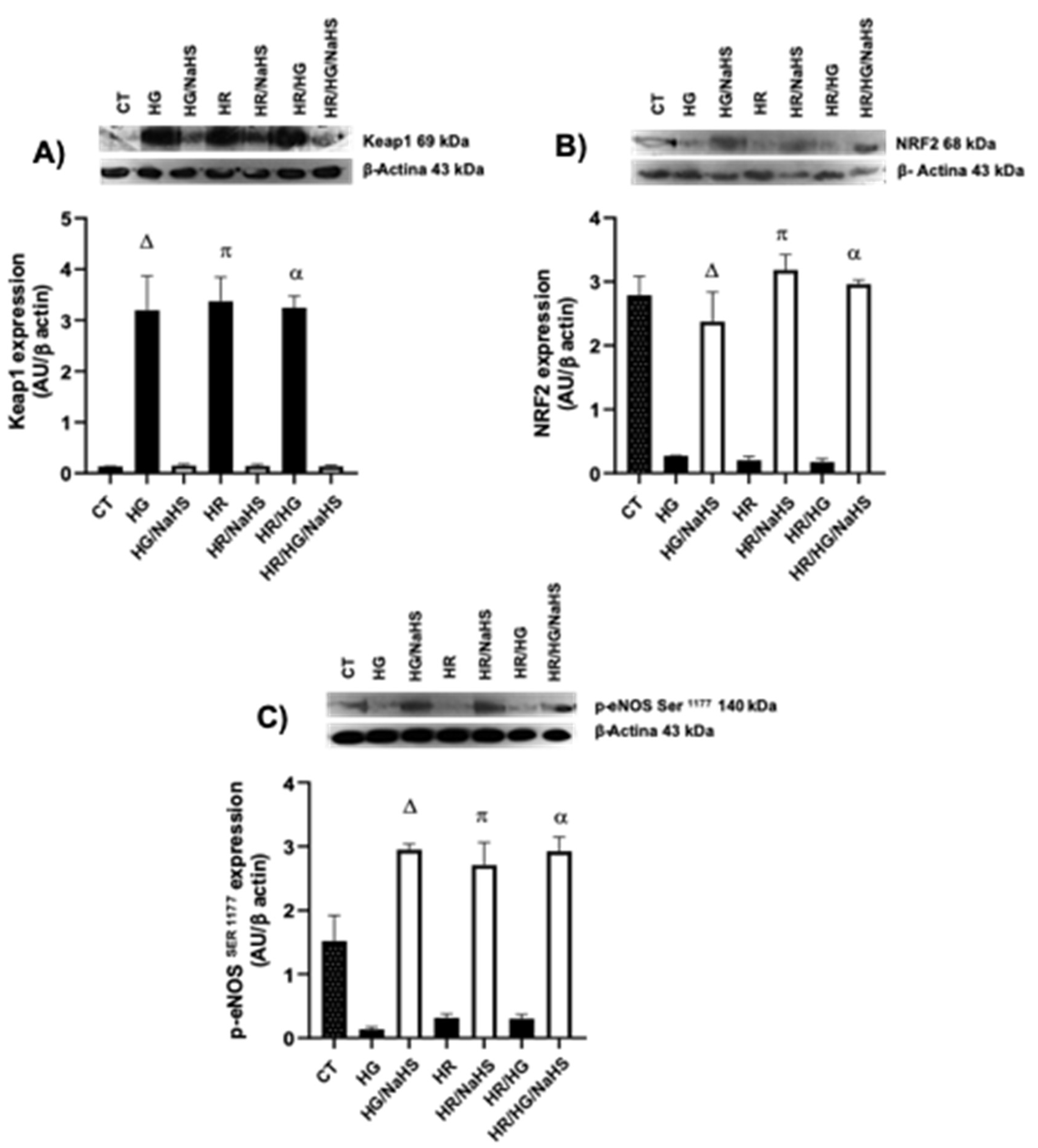

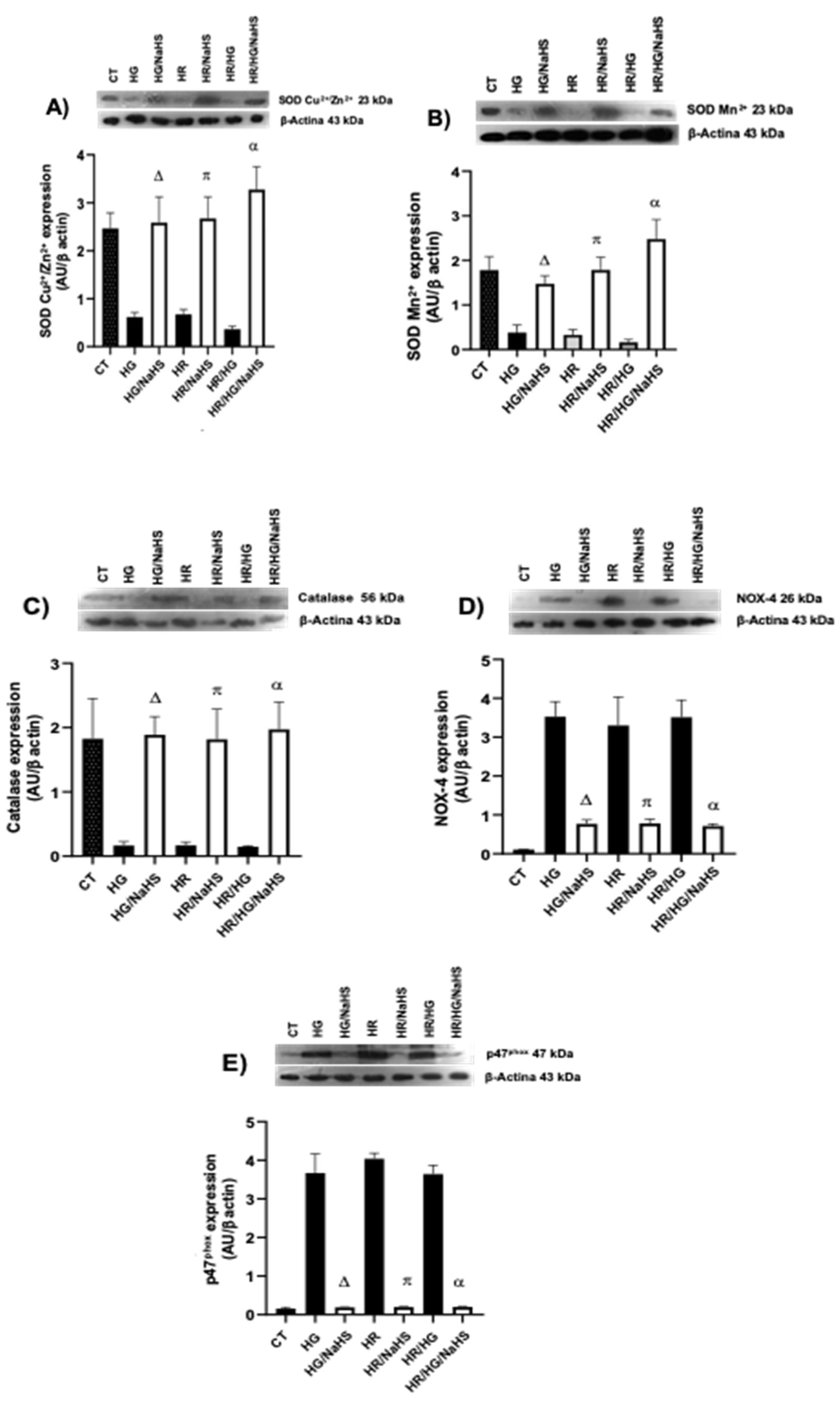

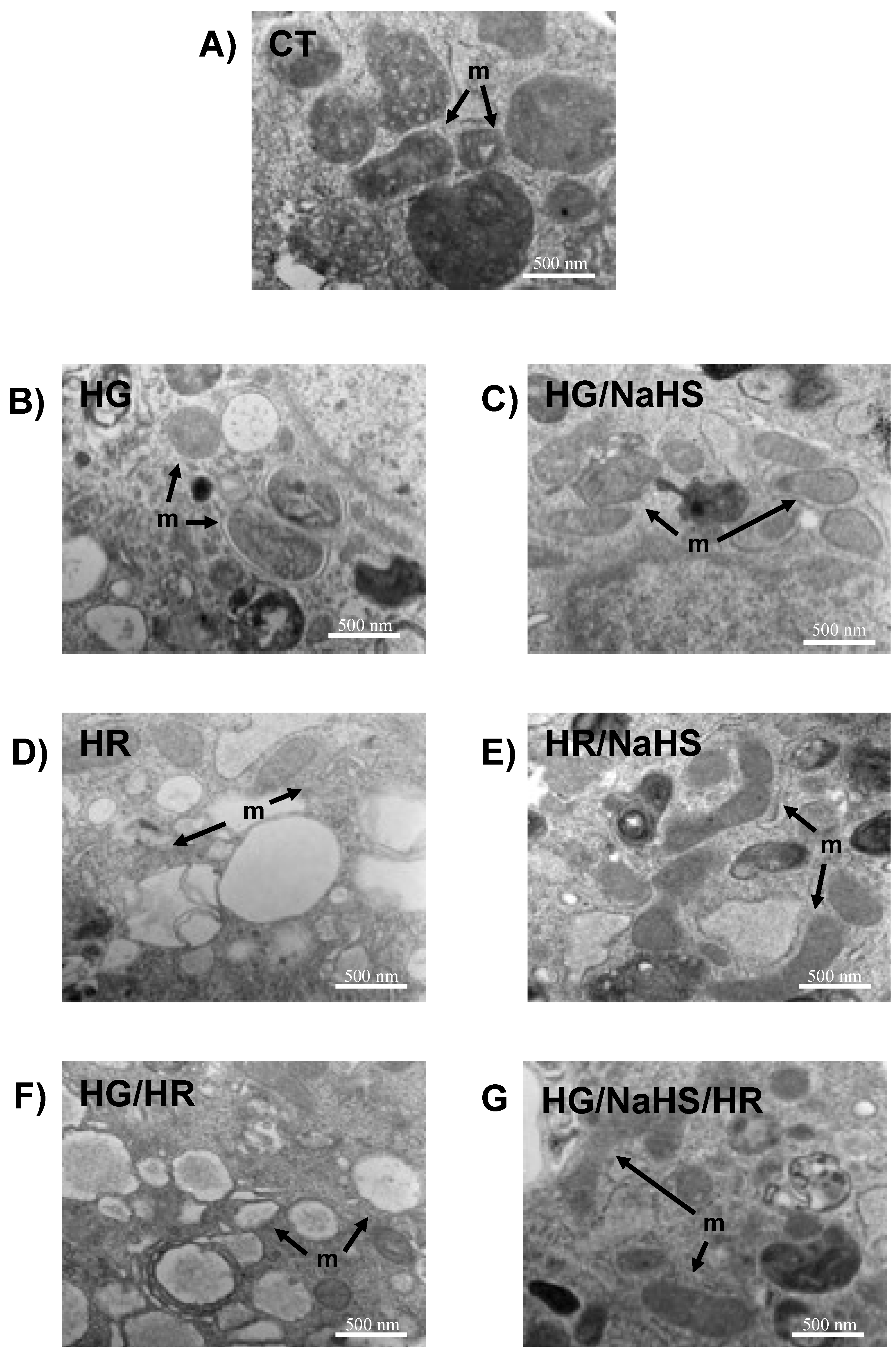

Under conditions of hyperglycemia and ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, myocardial oxidative stress increases, leading to cellular damage. Inhibition of oxidative stress has been reported to be involved in the cardioprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) during I/R and diabetes. Recent studies have shown that H2S has the potential to protect the heart. However, the mechanism by which H2S regulates the level of cardiac reactive oxygen species (ROS) during I/R and hyperglycemic conditions remains unclear. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the cytoprotective effect of H2S in primary cardiomyocyte cultures subjected to hyperglycemia, hypoxia/reoxygenation (HR), or both conditions, by assessing the PPAR-α/Keap1/Nrf2/p47phox/NOX4/p-eNOS/CAT/SOD signaling pathway and the PPAR-γ/PGC1α/AMPK/GLUT4 signaling pathway. Treatment with NaHS (100 μM) as an H2S donor in cardiomyocytes subjected to hyperglycemia, HR, or a combination of both experimental conditions increased cell viability, total antioxidant capacity, and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) concentrations, while reducing ROS production, malondialdehyde concentrations, 8-hydroxy-2´-deoxyguanosine, and dihydrobiopterin (BH2) concentrations. Additionally, H2S donor treatment increased the expression and activity of PPAR-α, reversed the reduction in the expression of PPAR-γ, PGC1α, AMPK, GLUT4, Nrf2, p-eNOS, SOD and CAT, and decreased the expression of Keap1, p47phox y NOX4. Treatment with the H2S donor protects cardiomyocytes from damage caused by hyperglycemia, HR, or both conditions by reducing oxidative stress markers and improving antioxidant mechanisms, thereby increasing cell viability and cardiomyocyte ultrastructure.

Keywords:

Introduction

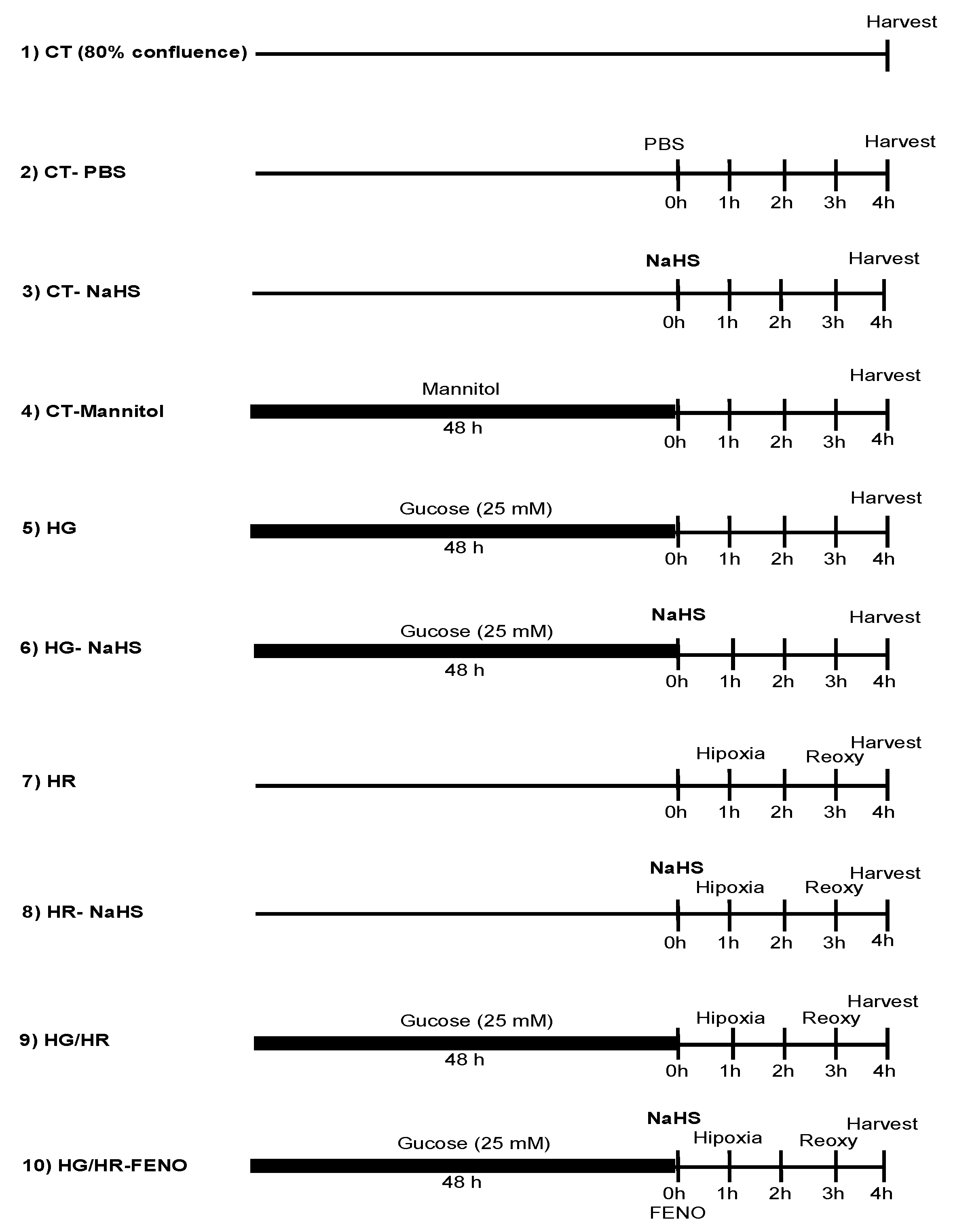

Material and Methods

2.Animals

2.Neonatal Rat Cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) Isolation and Culture

2.HIF1-α Expression

2.Cell Viability

2.Antioxidant Capacity Assay

2.ROS Production

2.Quantification of Malondialdehyde (MDA).

2.Quantification of 8-Hydroxy-2’-Deoxyguanosine (8-OH-2dG)

2.Capillary Zone Electrophoresis for Determination of BH4 and BH2

2.Palmitoyl CoA Oxidase Activity

2.Protein Expression by Western Blot

2.Mitochondria Ultrastructure

2.Statistical Analysis

Results

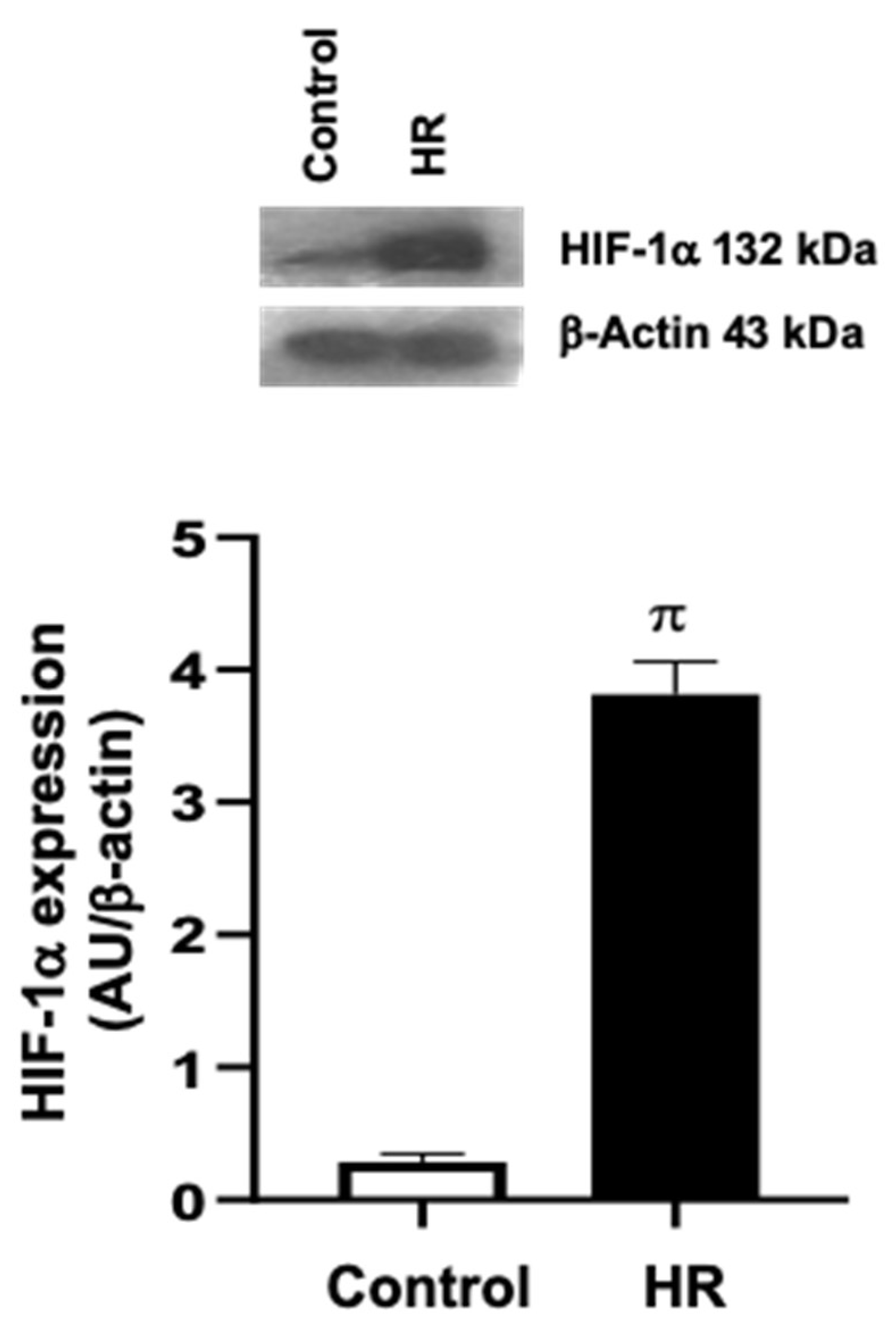

3.Evaluation of the Hypoxia/Reoxygenation (HR) Model in Primary Cardiomyocyte Cultures

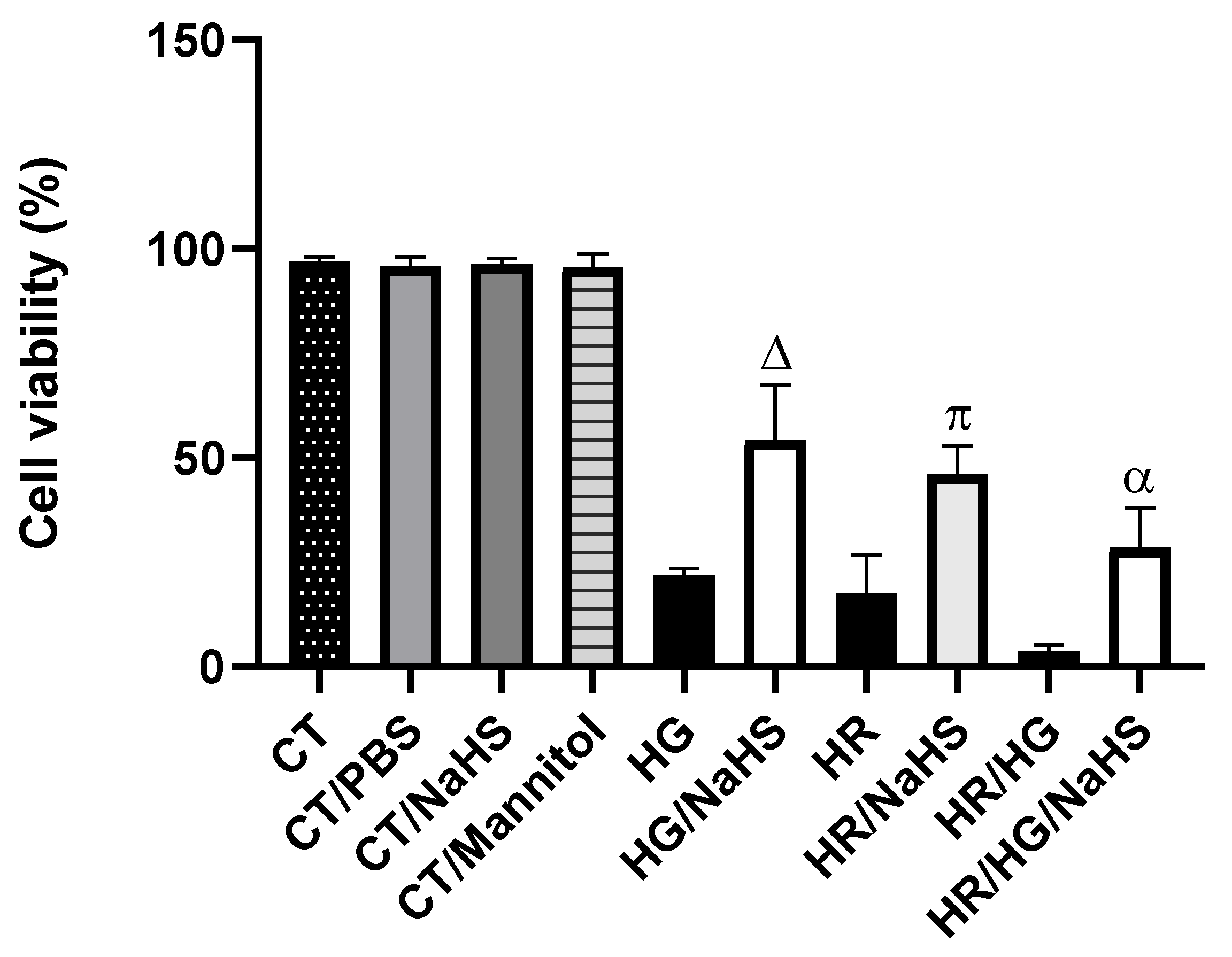

3.Evaluation of Cell Viability

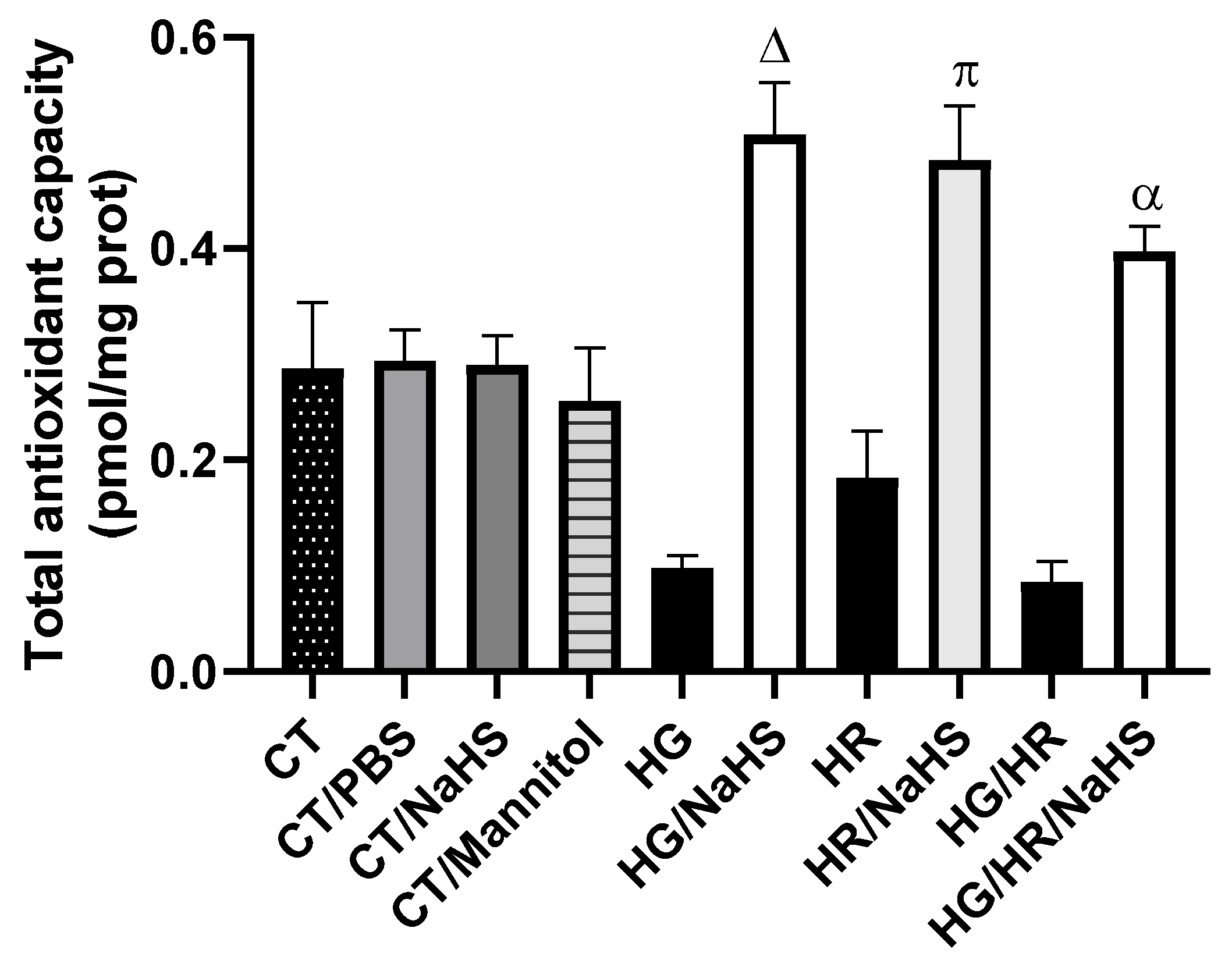

3.Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC)

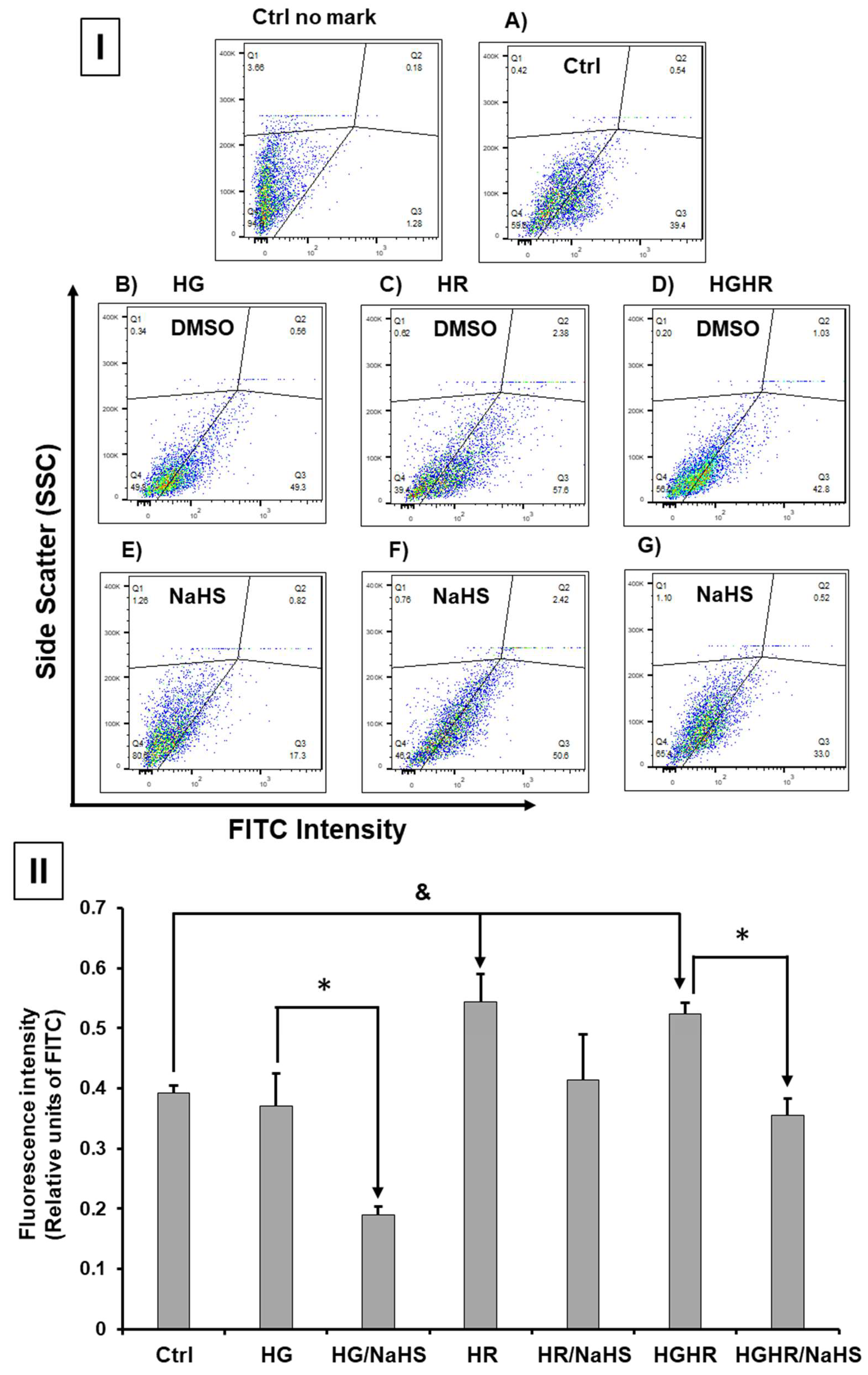

3.ROS Production

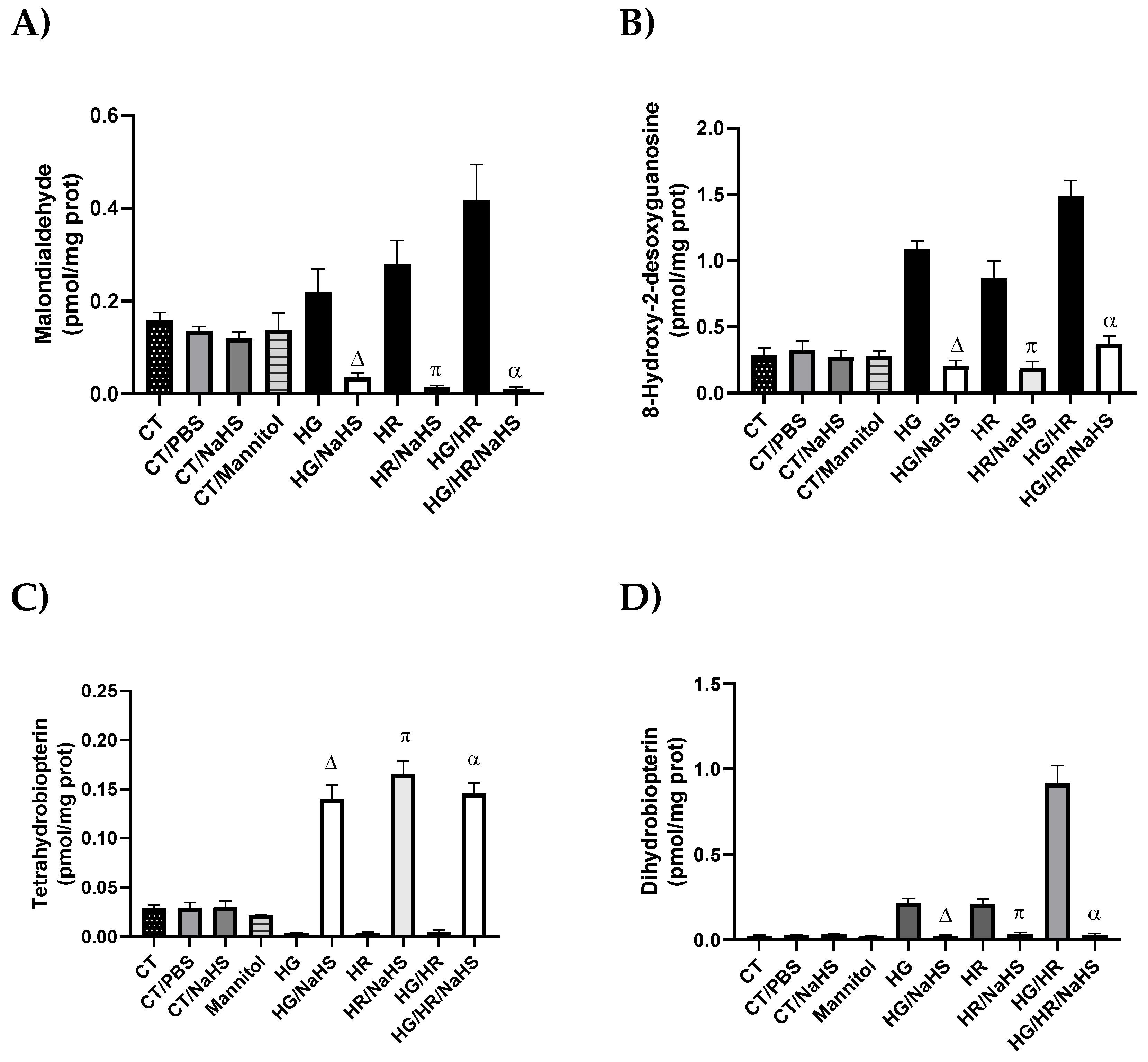

3.Evaluation of Oxidative Stress

3.Evaluation of Cofactor for eNOS, Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), and Its Oxidation Product (BH2)

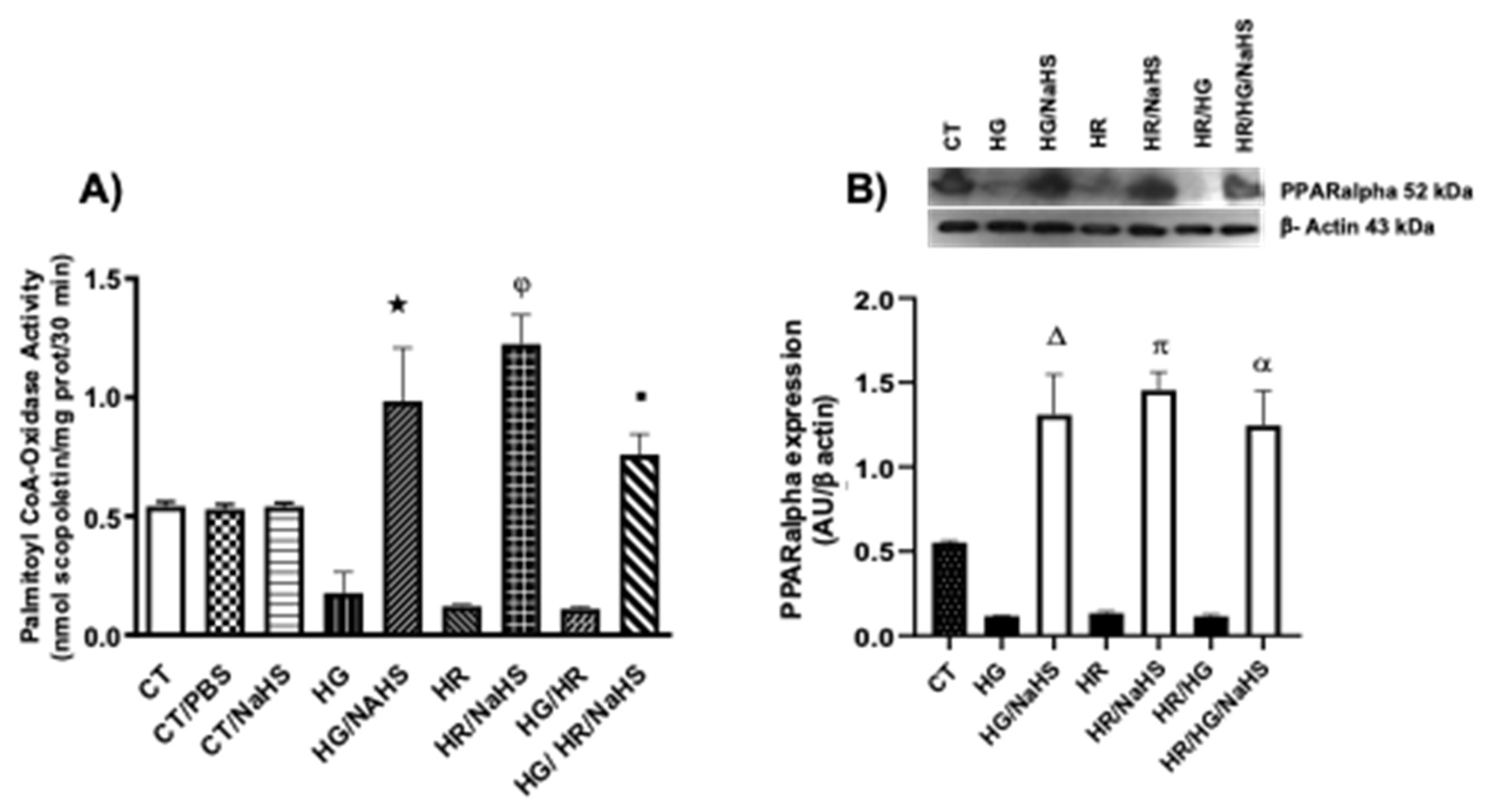

3.Evaluation of Palmitoyl-CoA Oxidase Activity and PPAR-α Expression

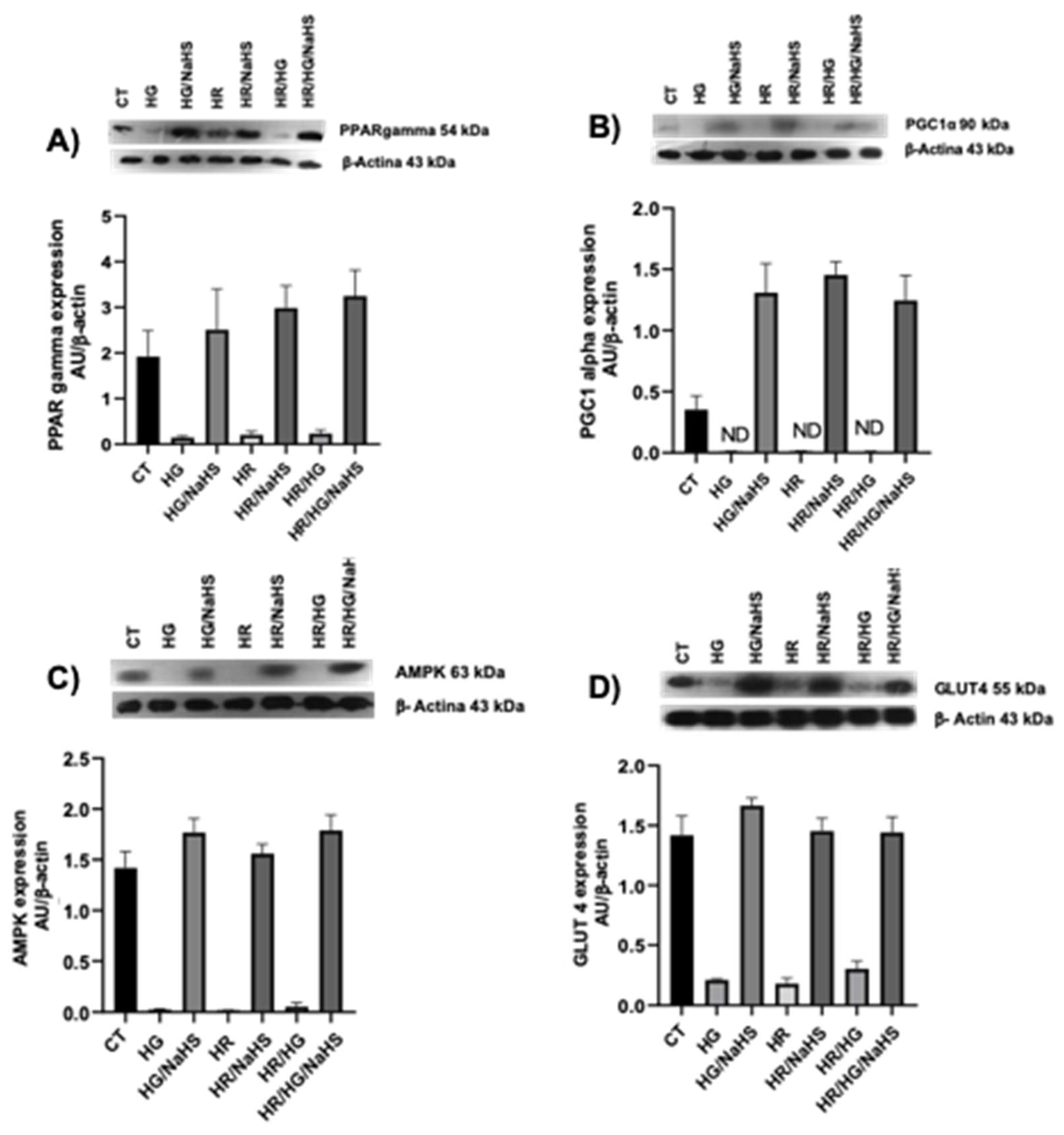

3.Evaluation of PPAR-γ, PGC 1α, AMPK, GLUT4, Keap1, Nrf2 y p-eNOS Ser1177 Expression

3.Evaluation of the Expression of SOD-Cu2+/Zn2+, SOD-Mn2+, catalase, NOX 4 y p47phox

3.Evaluation of Mitochondrial Ultrastructure in Cardiomyocytes

Discussion

Conclusions

Data Availability

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, Larrea-Sebal A, Siddiqi H, Uribe KB, et al. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Teven S, Affner MH, Eppo S, Ehto L, Apani T, Önnemaa R, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nesto, RW. Correlation between cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus: Current concepts. Am J Med. 2004, 116, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti JS, Sehrawat A, Mishra J, Sidhu IS, Navik U, Khullar N, et al. Oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and related complications: Current therapeutics strategies and future perspectives. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022, 184, 114–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang M, Lu Y, Xin L, Gao J, Shang C, Jiang Z, et al. Role of Oxidative Stress in Reperfusion following Myocardial Ischemia and Its Treatments. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021.

- Ide T, Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Utsumi H, Kang D, Hattori N, et al. Mitochondrial electron transport complex I is a potential source of oxygen free radicals in the failing myocardium. Circ Res. 1999, 85, 357–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla AK, Singal PK. Antioxidant changes in hypertrophied and failing guinea pig hearts. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 1994;266.

- Janaszak-Jasiecka A, Płoska A, Wierońska JM, Dobrucki LW, Kalinowski L. Endothelial dysfunction due to eNOS uncoupling: molecular mechanisms as potential therapeutic targets. Cell Mol Biol Lett [Internet]. BioMed Central; 2023;Available from, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda J, Ago T, Matsushima S, Zhai P, Schneider MD, Sadoshima J. NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) is a major source of oxidative stress in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15565–70.

- Ibarra-Lara L, Hong E, Soria-Castro E, Torres-Narváez JC, Pérez-Severiano F, Del Valle-Mondragón L, et al. Clofibrate PPARα activation reduces oxidative stress and improves ultrastructure and ventricular hemodynamics in no-flow myocardial ischemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2012, 60, 323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójtowicz S, Strosznajder AK, Jeżyna M, Strosznajder JB. The Novel Role of PPAR Alpha in the Brain: Promising Target in Therapy of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurochem Res [Internet]. Springer US; 2020;45:972–Available from, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Oh YS, Jun HS. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1–16.

- Bian JS, Qian CY, Pan TT, Feng ZN, Ali MY, Zhou S, et al. Role of hydrogen sulfide in the cardioprotection caused by ischemic preconditioning in the rat heart and cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006, 316, 670–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Huang H, Liu P, Tang C, Wang J. Hydrogen sulfide contributes to cardioprotection during ischemia-reperfusion injury by opening KATP channels. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007, 85, 1248–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li H, Zhang C, Sun W, Li L, Wu B, Bai S, et al. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide restores cardioprotection of ischemic post-conditioning via inhibition of mPTP opening in the aging cardiomyocytes. Cell Biosci. 2015, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ehler E, Moore-Morris T, Lange S. Isolation and culture of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. J Vis Exp. 2013;15:1–10.

- Brewer JH, Allgeier DL. Disposable Hydrogen Generator. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 1965;147:1033–Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.147.3661.1033.

- Brewer JH, Allgeier DL. Safe Self-contained Carbon Dioxide-Hydrogen Anaerobic System. Appl Microbiol. 1966;14:985–8.

- Karki P, Fliegel L. Overexpression of the NHE1 isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger causes elevated apoptosis in isolated cardiomyocytes after hypoxia/reoxygenation challenge. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;338:47–57.

- Jin KK, Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Estrogen prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis through inhibition of reactive oxygen species and differential regulation of p38 kinase isoforms. J Biol Chem [Internet]. © 2006 ASBMB. Currently published by Elsevier Inc; originally published by American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2006;281:6760–Available from, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Zou C, Li W, Pan Y, Khan ZA, Li J, Wu X, et al. 11β-HSD1 inhibition ameliorates diabetes-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis through modulation of EGFR activity. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 96263–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes-Lopez F, Sanchez-Mendoza A, Centurion D, Cervantes-Perez LG, Castrejon-Tellez V, Del Valle-Mondragon L, et al. Fenofibrate Protects Cardiomyocytes from Hypoxia/Reperfusion- And High Glucose-Induced Detrimental Effects. PPAR Res.

- Strober, W. Trypan Blue Exclusion Test of Cell Viability. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2015;111:A3.B.1-A3.B.3.

- Crowley LC, Marfell BJ, Christensen ME, Waterhouse NJ. Measuring cell death by trypan blue uptake and light microscopy. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2016, 2016, 643–6. [Google Scholar]

- Apak R, Güçlü K, Özyürek M, Esin Karademir S, Altun M. Total antioxidant capacity assay of human serum using copper(II)-neocuproine as chromogenic oxidant: The CUPRAC method. Free Radic Res. 2005, 39, 949–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung HK, Song E, Jahng JWS, Pantopoulos K, Sweeney G. Iron induces insulin resistance in cardiomyocytes via regulation of oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–13.

- Sánchez-Aguilar M, Ibarra-Lara L, Del Valle-Mondragón L, Rubio-Ruiz ME, Aguilar-Navarro AG, Zamorano-Carrillo A, et al. Rosiglitazone, a Ligand to PPAR γ, Improves Blood Pressure and Vascular Function through Renin-Angiotensin System Regulation. PPAR Res. 2019;2019.

- Kvasnicová V, Samcová E, Jursová A, Jelínek I. Determination of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine in untreated urine by capillary electrophoresis with UV detection. J Chromatogr A. 2003, 985, 513–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walusimbi Kisitu M, Harrison EH. Fluorometric assay for rat liver peroxisomal fatty acyl-coenzyme A oxidase activity. J Lipid Res [Internet]. © 1983 ASBMB. Currently published by Elsevier Inc; originally published by American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.; 1983;24:1077. [CrossRef]

- González-Morán MG, Soria-Castro E. Changes in the tubular compartment of the testis of Gallus domesticus during development. Br Poult Sci. 2010;51:296–307.

- Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: A neglected therapeutic target. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:92–100.

- Cadenas, S. ROS and redox signaling in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and cardioprotection. Free Radic Biol Med [Internet]. Elsevier B.V.; 2018;117:76. [CrossRef]

- Daryabor G, Atashzar MR, Kabelitz D, Meri S, Kalantar K. The Effects of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Organ Metabolism and the Immune System. Front Immunol. 2020;11.

- De Vriese AS, Verbeuren TJ, Van De Voorde J, Lameire NH, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:963–74.

- Chen Y, Zhang F, Yin J, Wu S, Zhou X. Protective mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide in myocardial ischemia. J Cell Physiol [Internet]. 2020;235:9059–Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jcp.29761.

- Wang, R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: A whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:791–896.

- King AL, Polhemus DJ, Bhushan S, Otsuka H, Kondo K, Nicholson CK, et al. Hydrogen sulfide cytoprotective signaling is endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3182–7.

- Zhong X, Wang L, Wang Y, Dong S, Leng X, Jia J, et al. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide attenuates diabetic myocardial injury through cardiac mitochondrial protection. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012, 371, 187–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searcy DG, Whitehead JP, Maroney MJ. Interaction of Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase with hydrogen sulfide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995. p. 251–63.

- Comhaire F, Zalata A, Mahmoud A, Depuydt C, Dhooghe W, Christophe A. The role of reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in male infertility. Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2000;56:433–7.

- Mirończuk-Chodakowska I, Witkowska AM, Zujko ME. Endogenous non-enzymatic antioxidants in the human body. Adv Med Sci. 2018;63:68–78.

- Andreadi A, Bellia A, Di Daniele N, Meloni M, Lauro R, Della-Morte D, et al. The molecular link between oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes: A target for new therapies against cardiovascular diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2022;62:85. [CrossRef]

- Corsello T, Komaravelli N, Casola A. Role of hydrogen sulfide in nrf2-and sirtuin-dependent maintenance of cellular redox balance. Antioxidants. 2018;7:1–11.

- Hassan MI, Boosen M, Schaefer L, Kozlowska J, Eisel F, Von Knethen A, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB induces cystathionine Iγ-lyase expression in rat mesangial cells via a redox-dependent mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:2231–42.

- Hourihan JM, Kenna JG, Hayes JD. The Gasotransmitter Hydrogen Sulfide Induces Nrf2-Target Genes by Inactivating the Keap1 Ubiquitin Ligase Substrate Adaptor Through Formation of a Disulfide Bond Between Cys-226 and Cys-Antioxid Redox Signal [Internet]. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers; 2012;19:465. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Zhang F, Yin J, Wu S, Zhou X. Protective mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide in myocardial ischemia. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:9059–70.

- Liang D, Huang A, Jin Y, Lin M, Xia X, Chen X, et al. Protective effects of exogenous nahs against sepsis-induced myocardial mitochondrial injury by enhancing the PGC-1α/NRF2 pathway and mitochondrial biosynthesis in mice. Am J Transl Res. 2018, 10, 1422–30. [Google Scholar]

- Staels B, Fruchart JC. Therapeutic roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists. Diabetes. 2005;54:2460–70.

- Kim SG, Lee WH. AMPK-dependent metabolic regulation by PPAR agonists. PPAR Res. 2010;2010.

- Lin F, Yang Y, Wei S, Huang X, Peng Z, Ke X, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects against high glucose-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cell injury through activating PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:621–33.

- Li D, Xiong Q, Peng J, Hu B, Li W, Zhu Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide up-regulates the expression of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 via promoting nuclear translocation of PPARα. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:6–8.

- Zhang H, Pan J, Huang S, Chen X, Chia A, Chang Y, et al. Redox Biology Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis through the SLC7A11 / GSH / GPx4 pathway by Keap1 S-sulfhydration and Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol [Internet]. Elsevier B.V.; 2024;70. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Tang J, Zhang S, Pang K, Zhao Y, Liu N, et al. Exogenous H2S initiating Nrf2/GPx4/GSH pathway through promoting Syvn1-Keap1 interaction in diabetic hearts. Cell Death Discov. Springer US; 2023;9:1–14.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).