1. Introduction

Hydraulic fracturing refers to the expansion and

extension of fractures existing within rock masses under the action of

high-pressure water flow or other liquids [1].

Hydraulic fracturing was first applied in the petroleum industry to increase

the output of oil wells, and was later used in fields such as in-situ stress

measurement, nuclear waste storage and geothermal development [2]. Meanwhile, hydraulic fracturing can also have

serious consequences for engineering projects. For example, rock slopes may

slide under the action of groundwater, high-pressure water conveyance

structures and reservoir dams may crack, and water gushing may occur during

tunnel construction. Therefore, the problem of hydraulic fracturing in rock

masses has become an issue that urgently needs to be solved at present.

Numerical simulation methods provide important

tools for studying the mechanism of hydraulic fracturing in rocks. Among them,

the Extended Finite Element Method (XFEM) is a relatively effective numerical

simulation method for analyzing discontinuous problems [3]. When this method is used to analyze fracture

problems, its computational grid is independent of the physical boundaries or

the internal geometry of the structure. It overcomes the need for high-density

meshing in the crack tip region, and there is no need to re-mesh when

simulating crack propagation. Therefore, it can conveniently analyze the

problem of hydraulic fracturing in rocks. Sheng Mao et al. [4] used the Extended Finite Element Method to

simulate the propagation of a single hydraulic crack under the action of a

constant water pressure. Shi Luyang et al. [5]

introduced the uncoupled model of hydraulic fracturing into the Extended Finite

Element Method to simulate the propagation of hydraulic fractures and natural

fractures. Zhang et al. [6] combined the phase

field method with the Extended Finite Element Method to simulate the hydraulic

fracturing process of natural fractures in shale formations. Lecampion et al. [7] used the Extended Finite Element Method based on

the uncoupled model to simulate the crack width and pressure distribution in

hydraulic cracks. At present, there are relatively few studies on the mechanism

of hydraulic fracturing of rock compression cracks using the Extended Finite

Element Method.

In this paper, a numerical model for solving the

problems of hydraulic fracturing and frictional contact of rock cracks using

the extended finite element method is established. The computational model is

applied to the analysis of hydraulic fracturing of specimens with central

cracks and gravity dams with initial cracks under the action of axial pressure,

so as to study the influence of axial compressive stress and initial crack

length on the critical water pressure of hydraulic fracturing of specimens as

well as the influence of hydraulic fracturing on the crack stability of gravity

dams.

2. The Hydraulic Fracturing Model and Contact Model of the Extended Finite Element Method

2.1. The Approximate Displacement Function of the Extended Finite Element Method

The extended finite element method is based on the

partition of unity concept. Additional functions that reflect the singularity

at the crack tip and the discontinuity of the crack surface are added to the

traditional finite element approximate displacement function formula. Its

approximate displacement function is as follows [8]:

where is the nodal degrees of freedom of a conventional

element; is the additional degrees of freedom of a

crack-penetrating element; is the additional degrees of freedom of a crack-tip

element; is the set of all nodes within the computational

domain; is the set of nodes of the crack-penetrating

element; is the set of nodes of the crack-tip element; is the shape function of the node.

is a jump function that reflects the displacement

discontinuity of the crack-penetrating element:

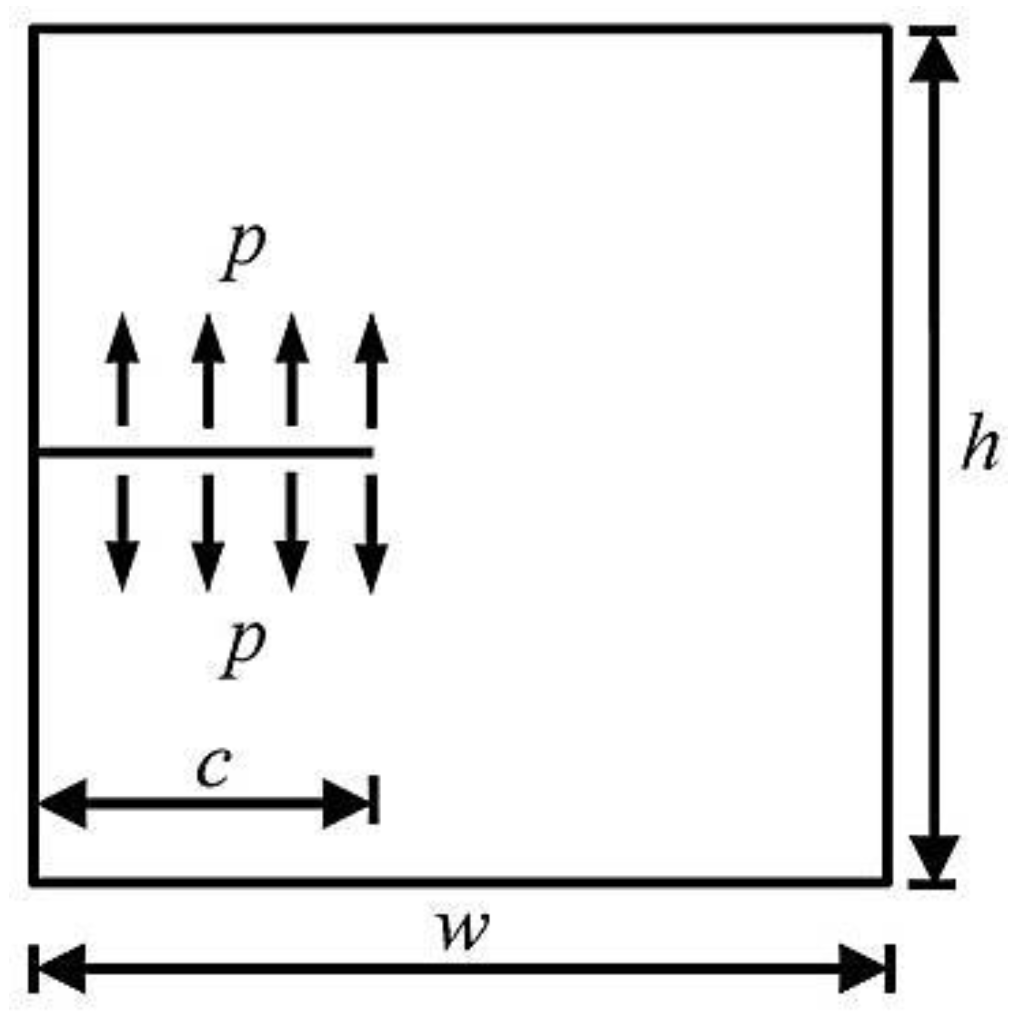

is an additional function of the crack-tip element that reflects the singularity at the crack tip [

9]:

where

are the local polar coordinates at the crack tip (see

Figure 1).

For the elements containing cracks, the relative displacement of the same point on the crack surfaces can be obtained from Equation (1):

where

represents the relative displacement of the same point on the crack surfaces.

2.2. Discrete Equations for Hydraulic Fracturing

After the displacement mode is constructed, the extended finite element governing equations for the hydraulic fracturing problem are derived through the principle of virtual work:

where

is the water pressure on the crack surface

;

is the external force on the boundary

;

is the body force on the computational domain

;

,

and

are the cauchy stress tensor, virtual displacement and virtual strain respectively.

Substituting the extended finite element approximate displacement expressions (1) and (4) into the extended finite element governing equation (5), the discrete equations for hydraulic fracturing can be obtained:

The global stiffness matrix

is assembled from the element stiffness matrices

the functional expressions of the strain matrices

,

,

can be found in Reference [

10].

is the node displacement vector:

is the equivalent nodal load vector of the body force

, the external force

and the water pressure

, and it can be expressed as:

where

.

2.3. Contact Model

The extended finite element governing equations for the frictional contact problem can be obtained from the principle of virtual displacement as follows:

where

is the contact force vector on the crack surface

(in the global coordinate system).

It can be obtained from the governing equation (11), formula (5) and the discrete equation (6):

where

is the equivalent nodal load vector of the contact force vector

on the crack surface.

The above formula can be written in the following form:

where

,

,

are the relative displacements generated by the external load

on the crack surface.

Equation (13) can be expressed in the following form:

where

,

,

are the global transformation matrices.

The above formula is the relational expression between the relative displacements and forces on the contact surface.

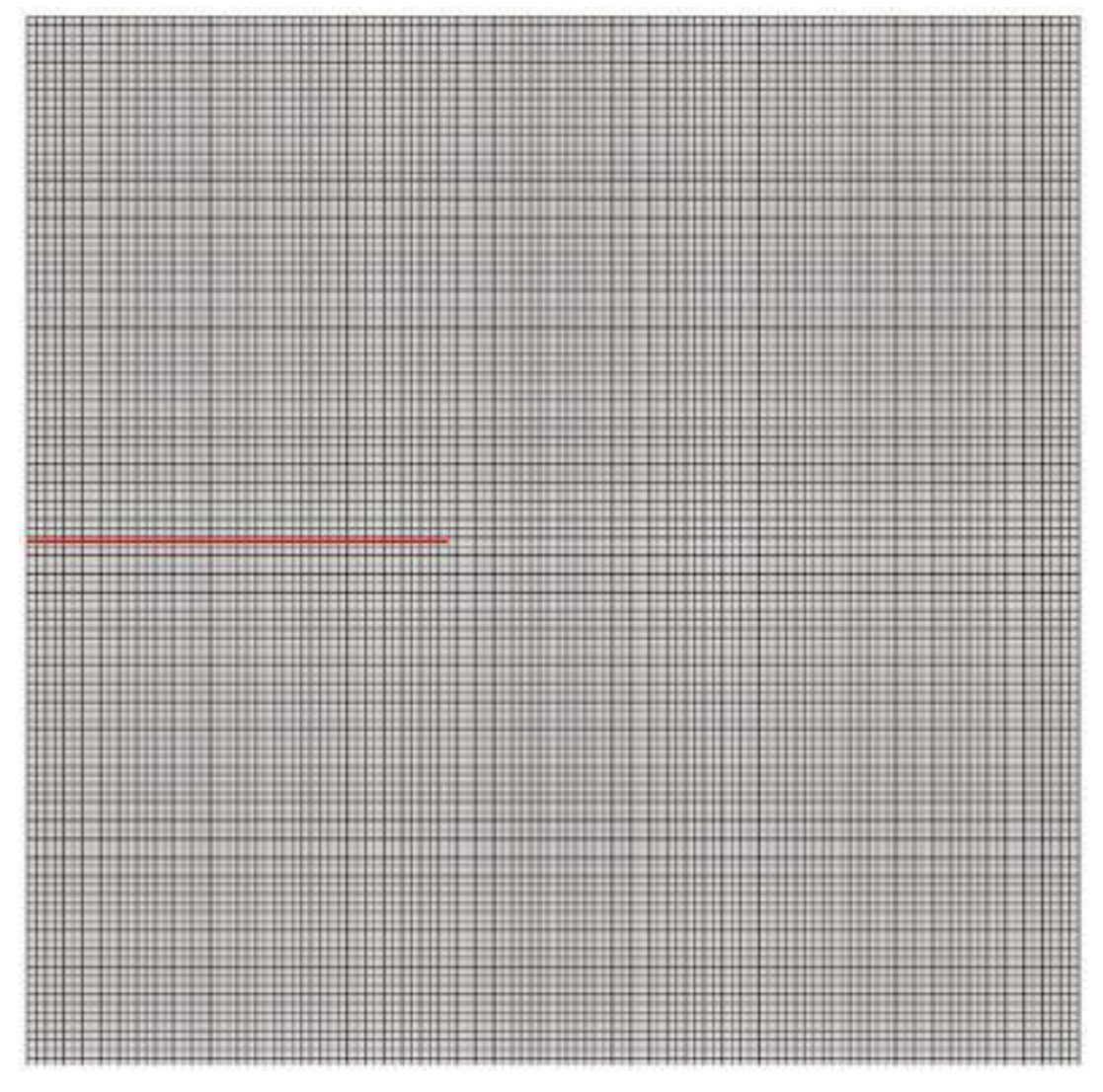

When dealing with contact problems using the conventional finite element method, it is required that the crack surface be consistent with the element boundary and that there are nodes on the crack surface. However, when handling contact problems with the extended finite element method, the crack surface can penetrate through the interior of the element and there are no nodes on the crack surface. In this paper, the contact relationship on the crack surface is reflected by using the relationship between the displacements and forces at the Gaussian points on the crack surface (see

Figure 2).

The Gaussian points are contact point pairs. Considering the -th contact point pair, it should satisfy the geometric compatibility condition and the friction condition (see Reference [

11]). These contact conditions can be written in the form of the following non-smooth equations of the nonlinear complementary type:

where

is the Coulomb friction coefficient.

It can be seen from Equation (15) that the vector

is a function of the vector

. Therefore, Equations (16) and (17) can be written as non-smooth equations of the nonlinear complementary type with

as the variable:

The above formula is a non-smooth equation system model of the nonlinear complementary type for the plane friction contact problem. In this paper, the non-smooth damped Newton method [

11] is adopted to directly solve the above non-smooth equation system.

3. Stress Intensity Factor Calculation and Crack Propagation Criterion

3.1. Calculation of Stress Intensity Factor

The stress intensity factor at the crack tip is calculated by the interaction integral method. The expression of the interaction integral

is as follows [

12]:

where

,

and

are the displacement vector, stress tensor and strain tensor respectively;

is the integral region around the crack tip;

is the Kronecker delta;

is the weight function;

is the water pressure on the crack surface; the superscript 1 represents the real state and takes the numerical solution of the extended finite element method; the superscript 2 represents the auxiliary state and takes the crack tip asymptotic field.

is the interaction strain energy density of states 1 and 2, and its expression is as follows:

There is the following relationship between the stress intensity factor and the interaction integral [

12]:

for plane strain,

; for plane stress,

.

Selecting state 2 as the asymptotic fields of mode I and mode II, the stress intensity factors of mode I and mode II for state 1 can be obtained: , .

3.2. Crack Propagation Criterion

The crack propagation criterion adopts the maximum circumferential stress criterion to obtain the crack propagation angle

:

The equivalent stress intensity factor

is determined by the following formula:

4. Numerical Examples

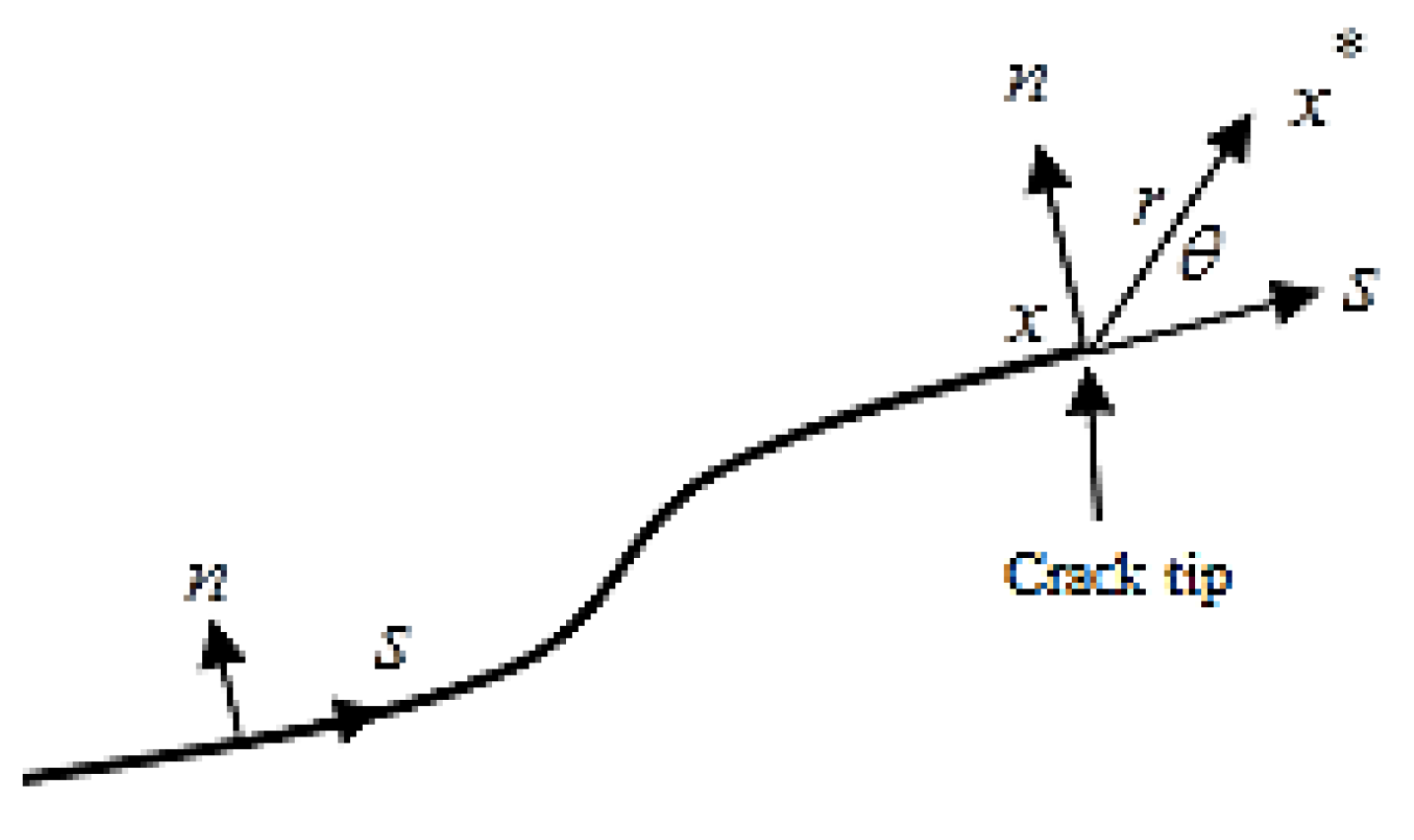

4.1. A Plate with a Single-Edge Crack

The rectangular plate with the length of a single-edge crack being

is shown in

Figure 3. The width of the flat plate is

, the height is

, and the uniformly distributed water pressure

acts on the crack surface. The elastic modulus of the material of the rectangular plate is

, and the Poisson's ratio is

.

Figure 3.

A rectangular plate with edge crack.

Figure 3.

A rectangular plate with edge crack.

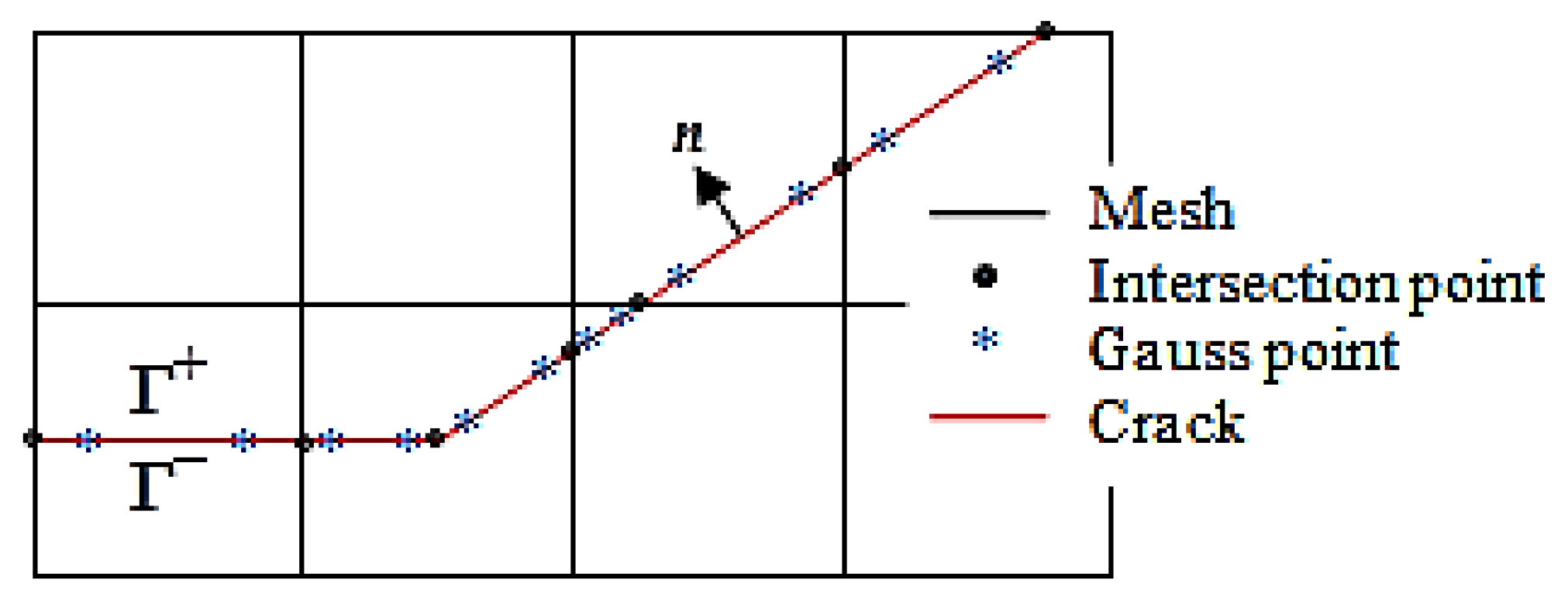

Figure 4.

Mesh generation.

Figure 4.

Mesh generation.

According to the superposition principle [

13], the exact solution of the stress intensity factor when the crack surface is subjected to the action of uniformly distributed water pressure is

Let the normalized stress intensity factor

where

is the stress intensity factor calculated by the method proposed in this paper.

Table 1.

Normalized SIF values for different elements.

Table 1.

Normalized SIF values for different elements.

| |

the number of mesh elements |

| 1225 |

2025 |

4225 |

5625 |

9025 |

13225 |

|

0.9011 |

0.9292 |

0.9627 |

0.9734 |

0.9894 |

1.0008 |

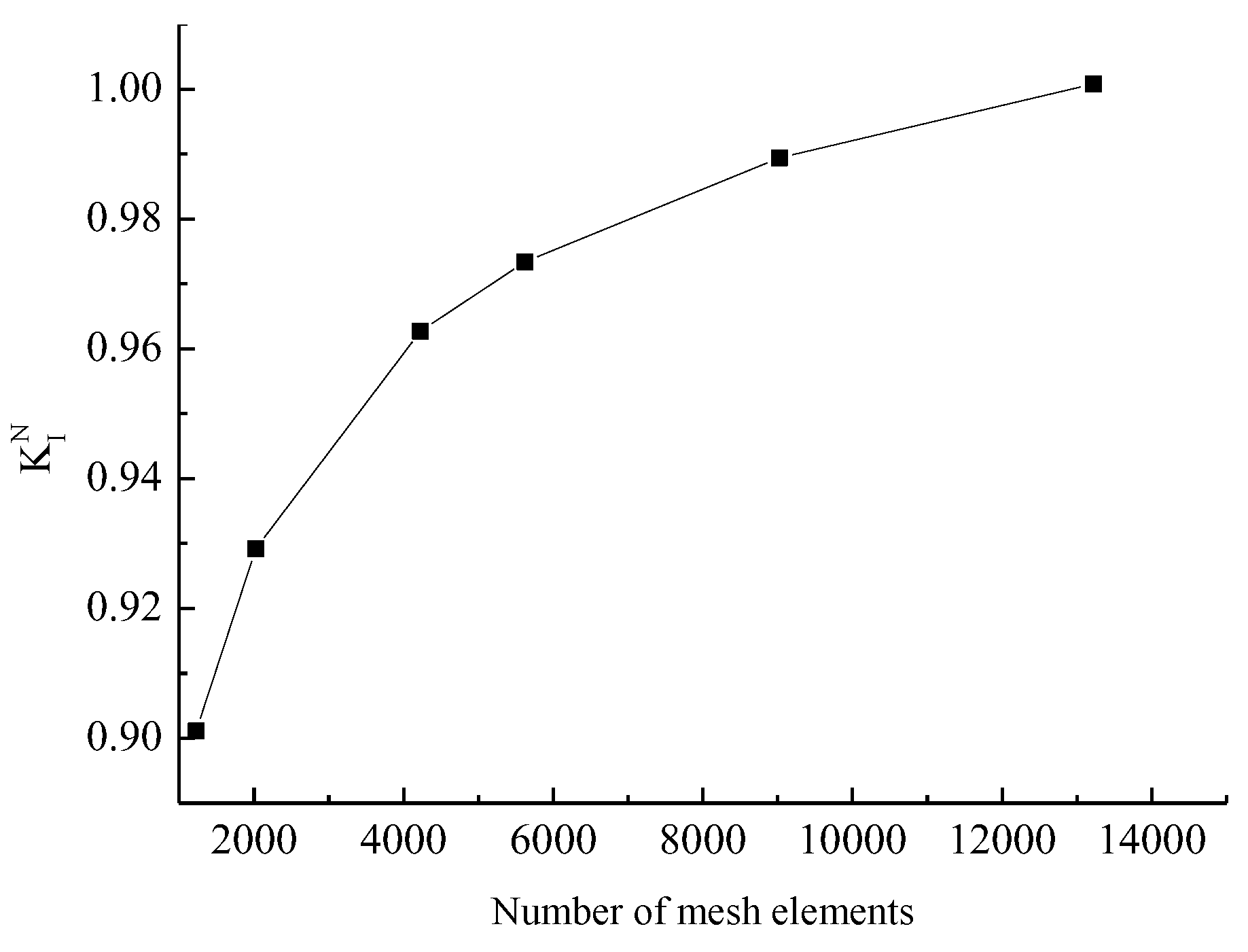

The influence of the number of mesh elements on the value of the normalized stress intensity factor is shown in

Figure 5. It can be seen from the figure that high computational accuracy can be achieved even when the number of elements is relatively small. As the number of elements increases, the computational error gradually decreases. When the number of mesh elements is around 10,000, the influence of the number of mesh elements on computational accuracy can be neglected.

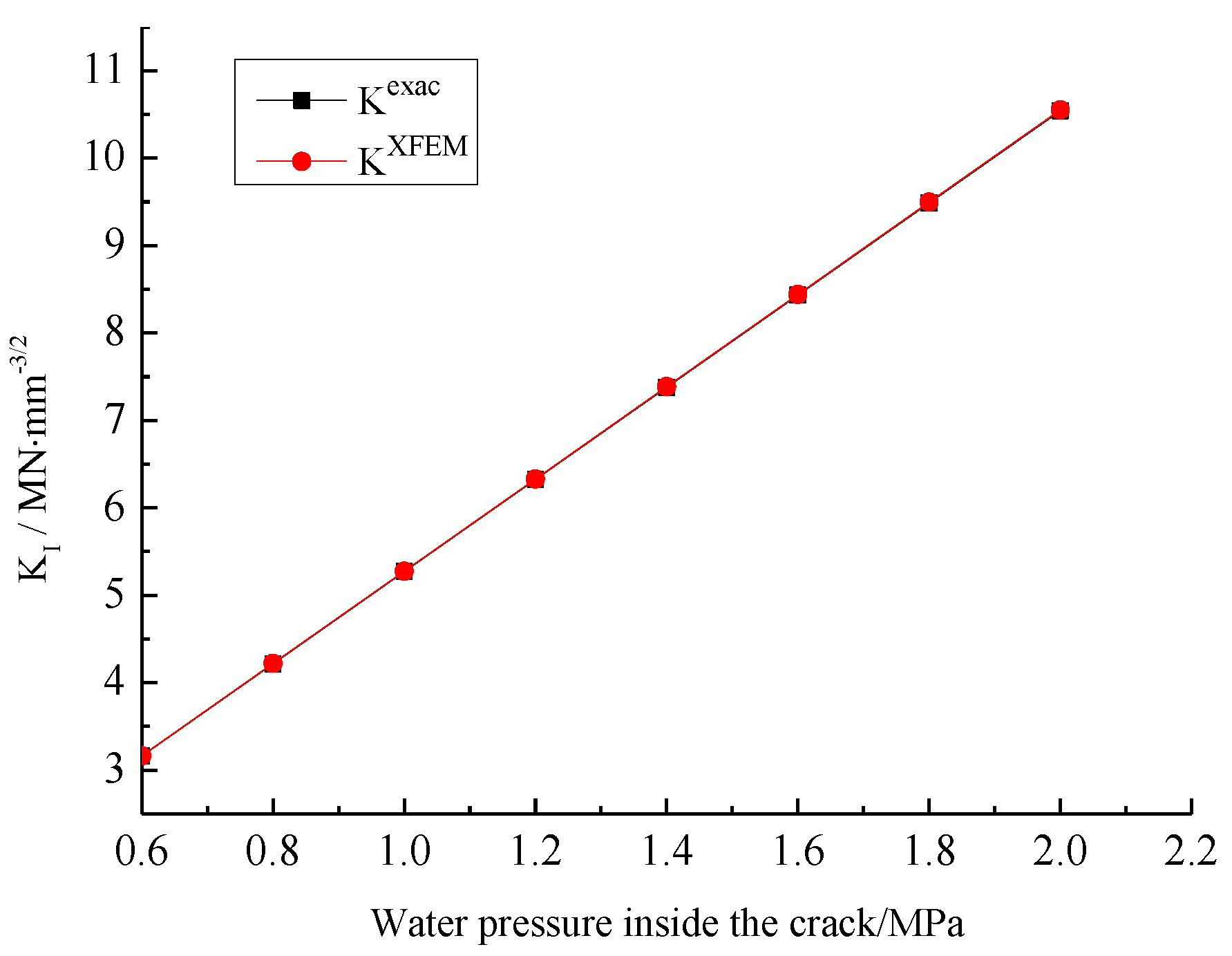

Figure 6 shows the stress intensity factors under the action of different water pressures on the crack surface when the number of mesh elements is 13,225 (the mesh generation is shown in

Figure 4). It can be seen from the figure that the values of the stress intensity factors calculated by the method in this paper are consistent with the exact solutions, indicating that the method in this paper is accurate in calculating the stress intensity factors when the crack surface is subjected to the action of uniformly distributed water pressures.

4.2. A Plate with a Through Crack

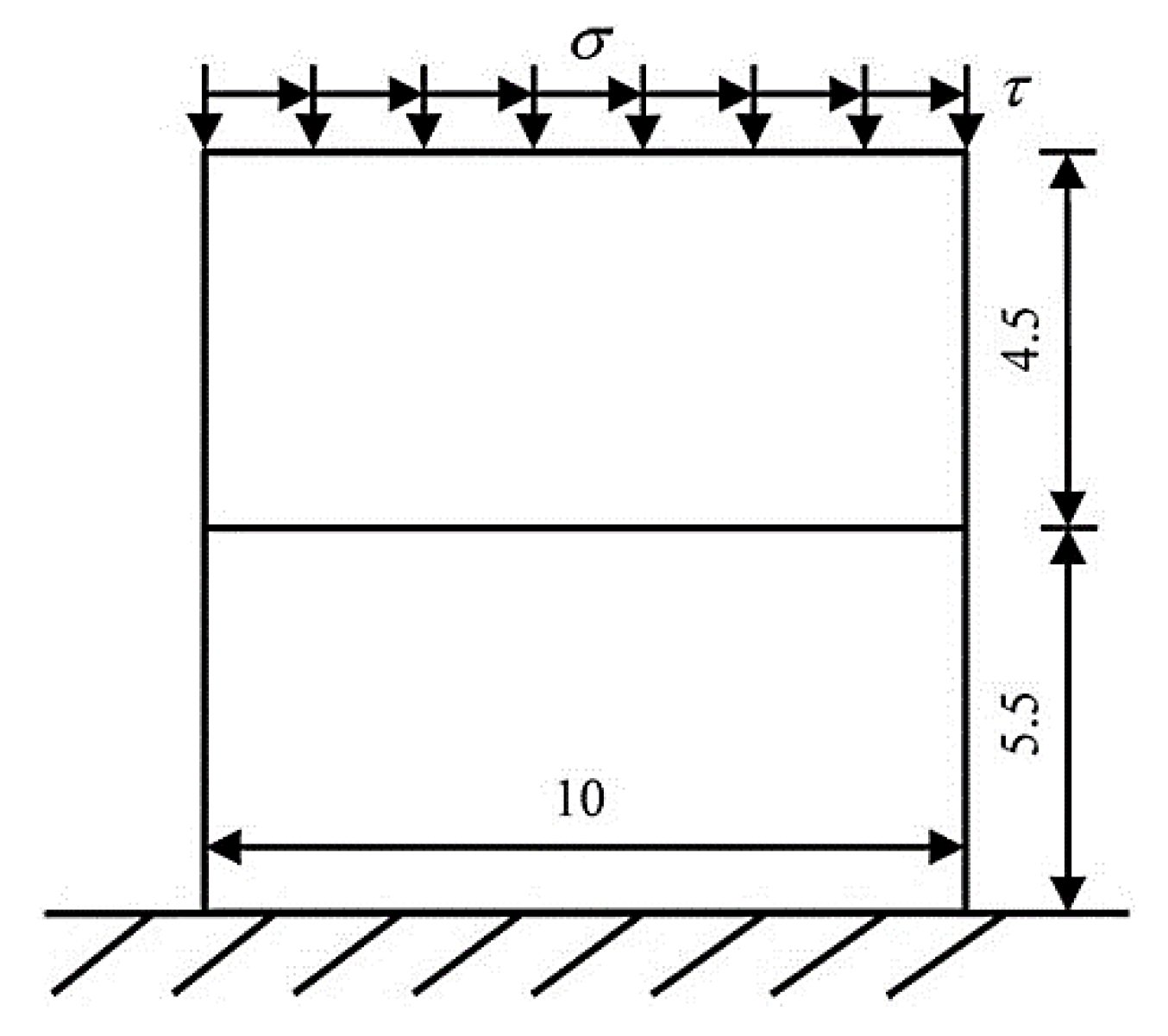

Figure 7 shows a rectangular plate with a through crack. The friction coefficient of the crack surface is

, the bottom is under fixed constraints. Both the length and width of the flat plate are 10 meters. Its top is subjected to the tangential uniformly distributed shear force

and the normal uniformly distributed pressure

, The elastic modulus is

, and the Poisson's ratio is

.

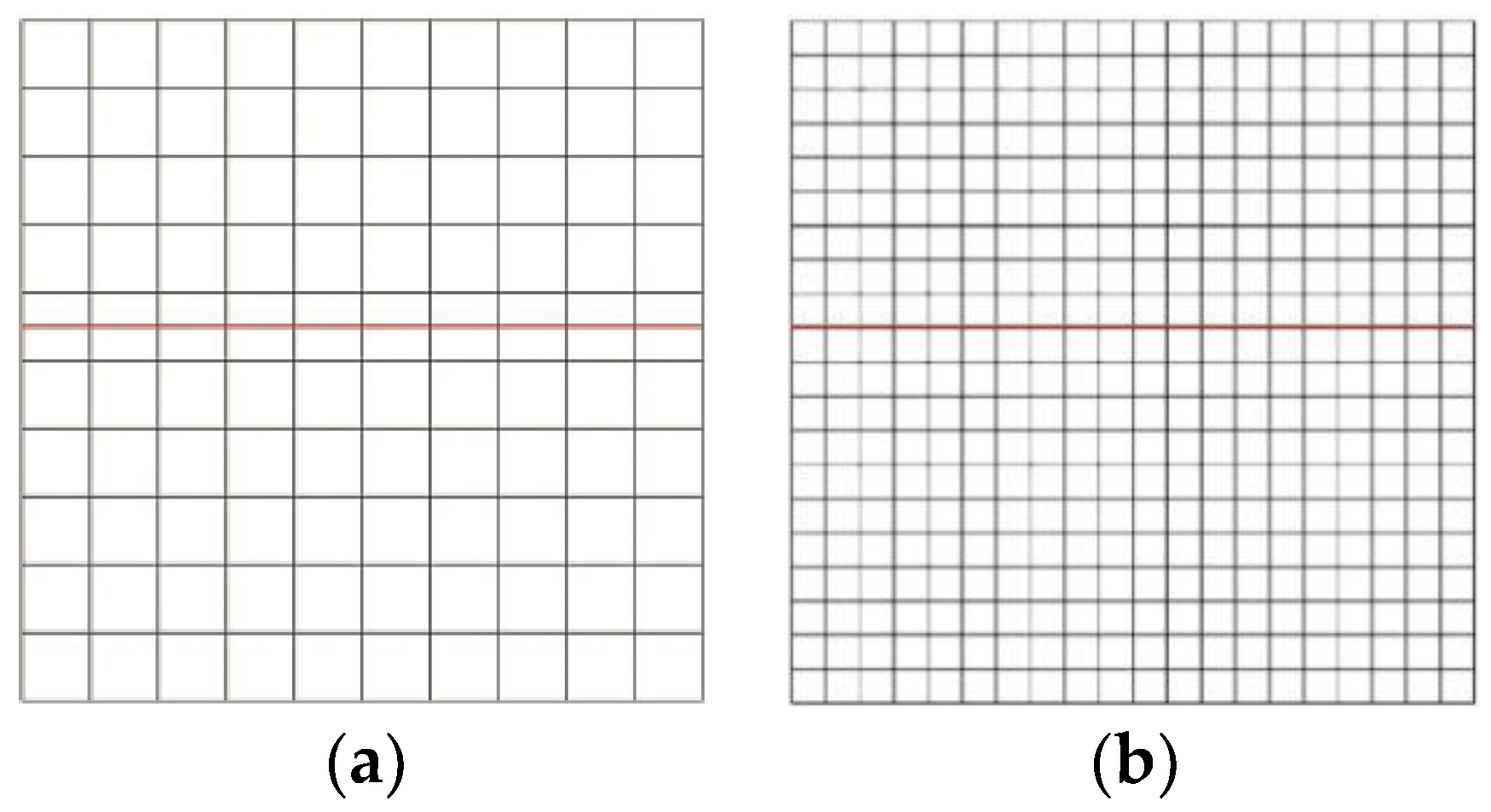

Figure 8a shows the extended finite element mesh, which adopts four-node isoparametric elements. The computational model is divided into 100 elements in total. The numerical example has undergone 5 iterations of calculation and met the convergence requirements, with a tolerance of 9.1104e

-9.

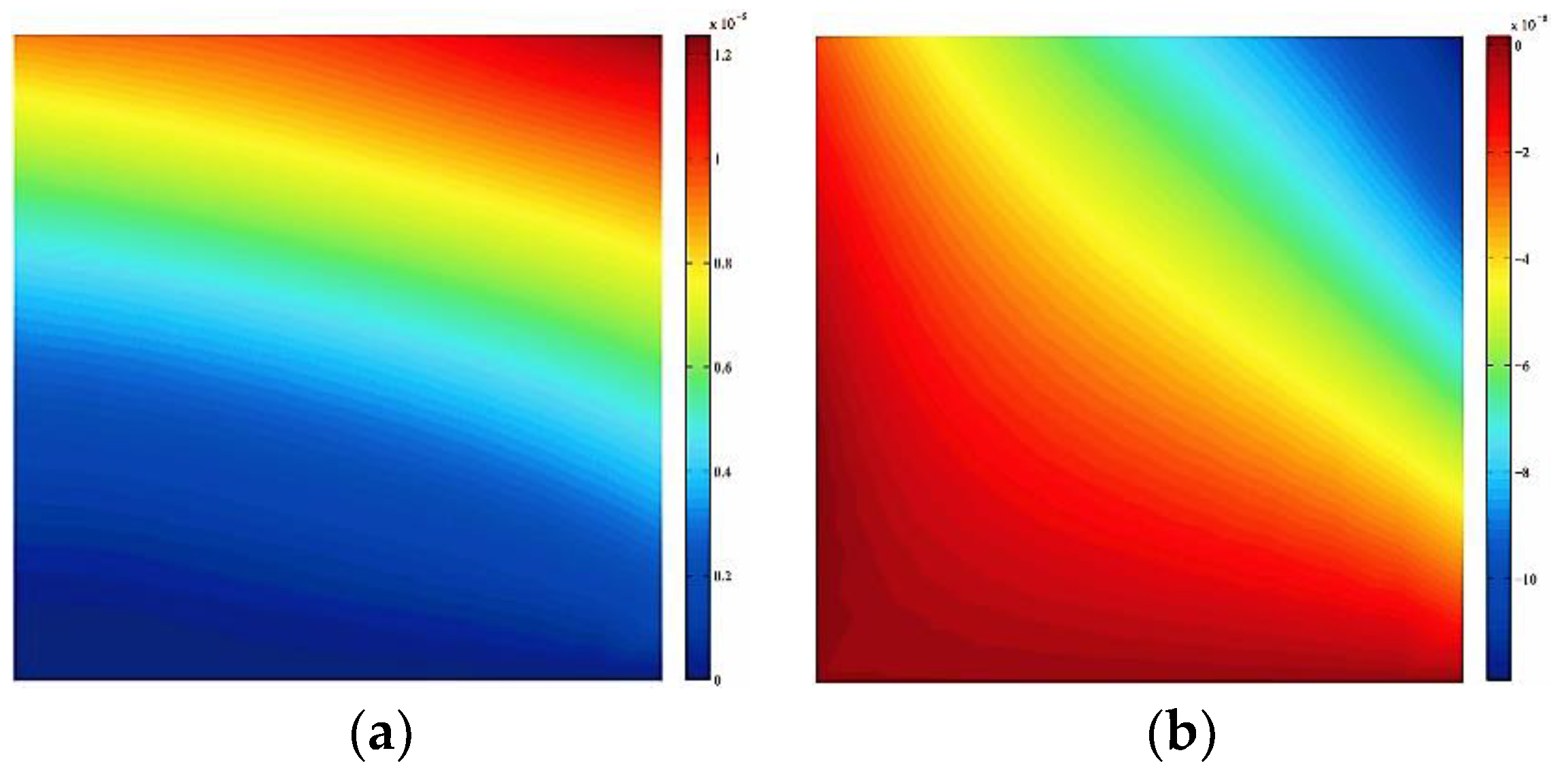

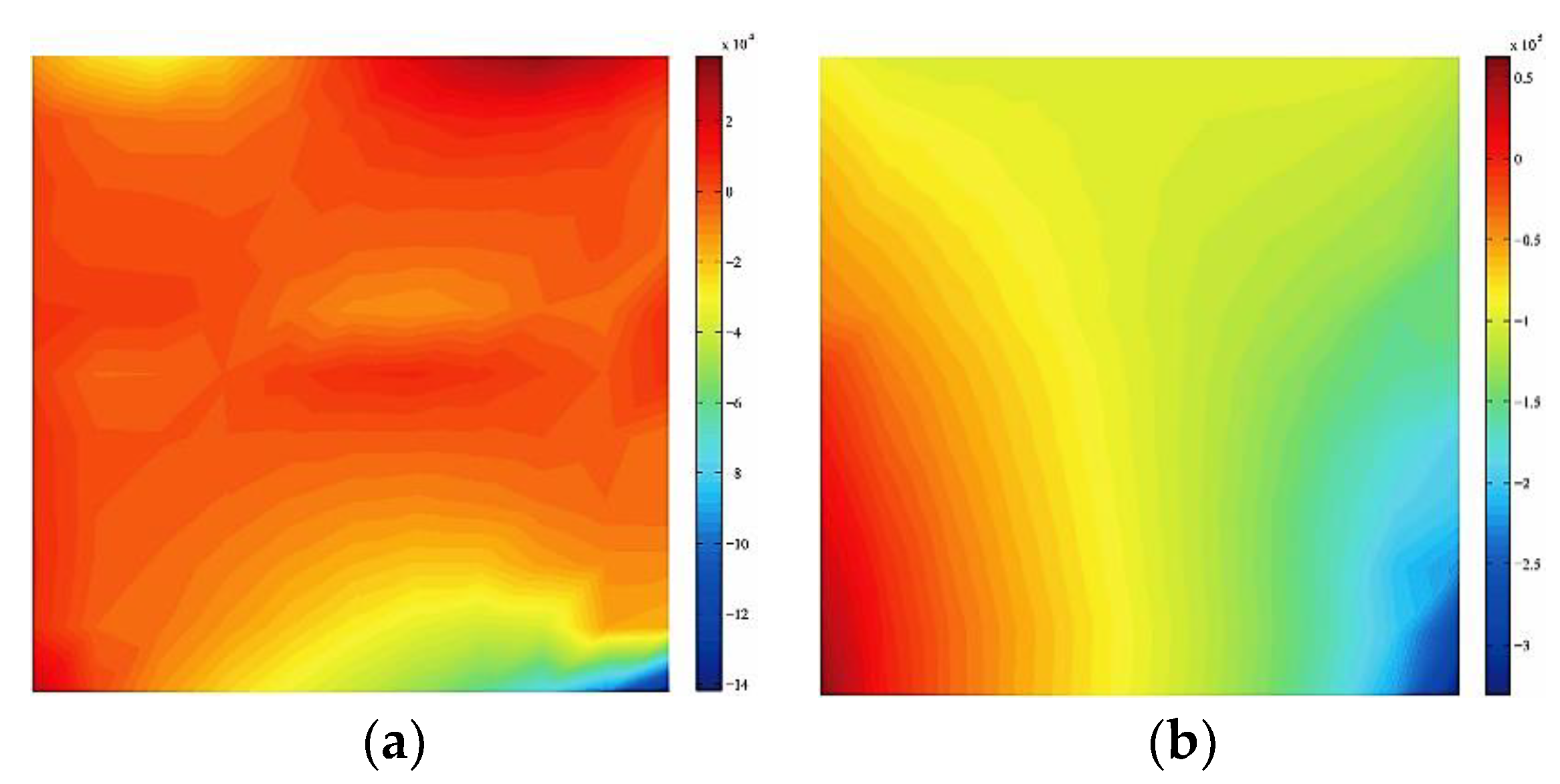

Figure 9 shows the displacement contour plot. It can be seen from the figure that under the action of compressive-shear stress, the horizontal and vertical displacements of the upper and lower parts of the crack surface are continuous, indicating that the contact algorithm in this paper is effective. The stress contour plot is shown in

Figure 10. As can be seen from the figure, the normal normal stress on the crack surface is continuous, while the tangential normal stress is discontinuous, which conforms to the conditions of the compressive stress contact surface.

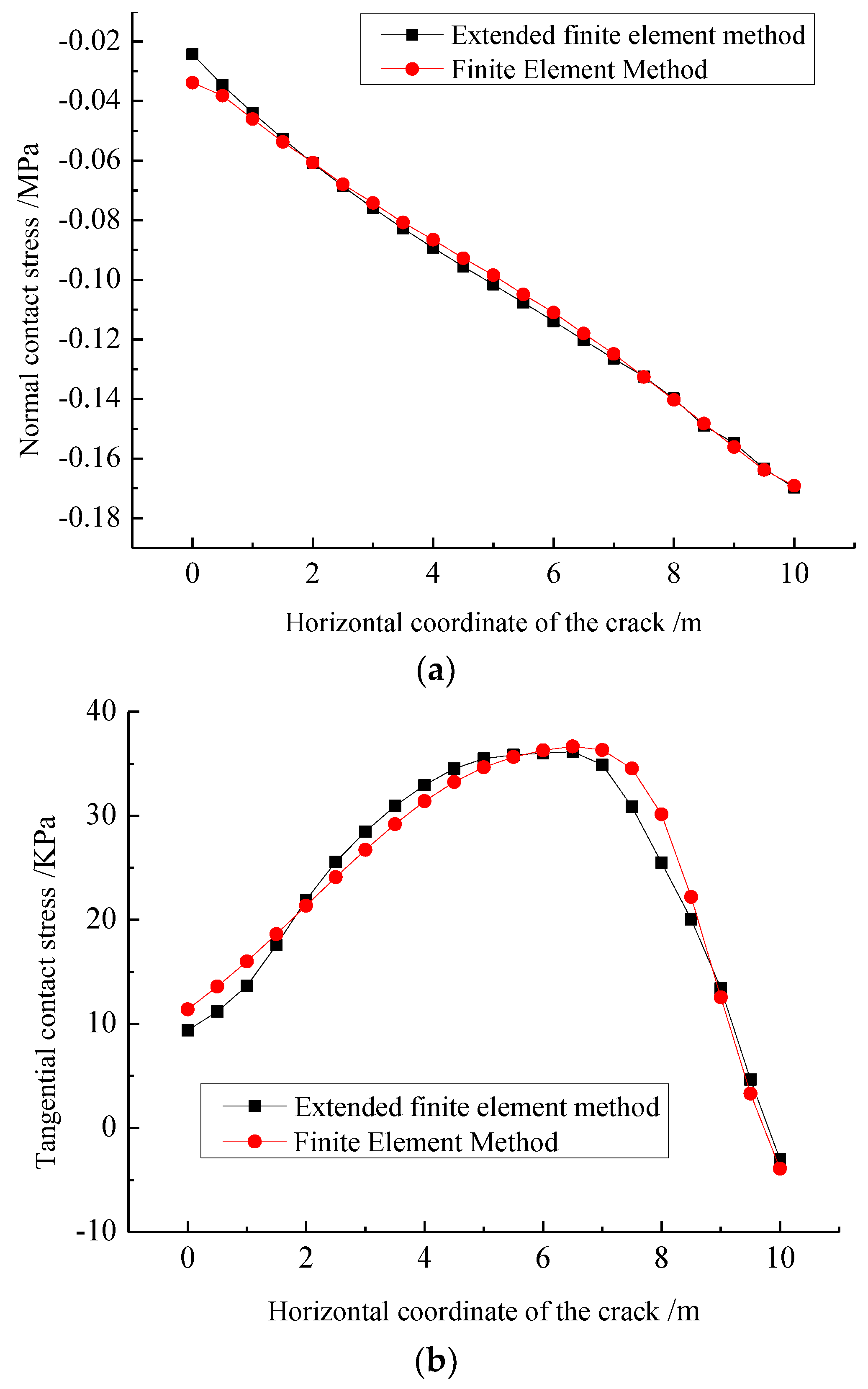

The contact algorithm in this paper is compared with the finite element penalty function method to verify the accuracy of the contact algorithm in this paper. The finite element mesh generation is shown in

Figure 8b, and the computational model is divided into 400 elements in total. The contact stresses on the crack surface calculated by the finite element penalty function method and the contact algorithm in this paper are shown in

Figure 11. It can be seen from the figure that the calculation results of the contact algorithm in this paper and the finite element penalty function method are quite consistent, indicating that the contact algorithm in this paper is accurate.

Table 2 presents the normal contact forces, normal relative displacements as well as tangential contact forces and tangential relative displacements of Gaussian points 1 to 20 on the crack surface.

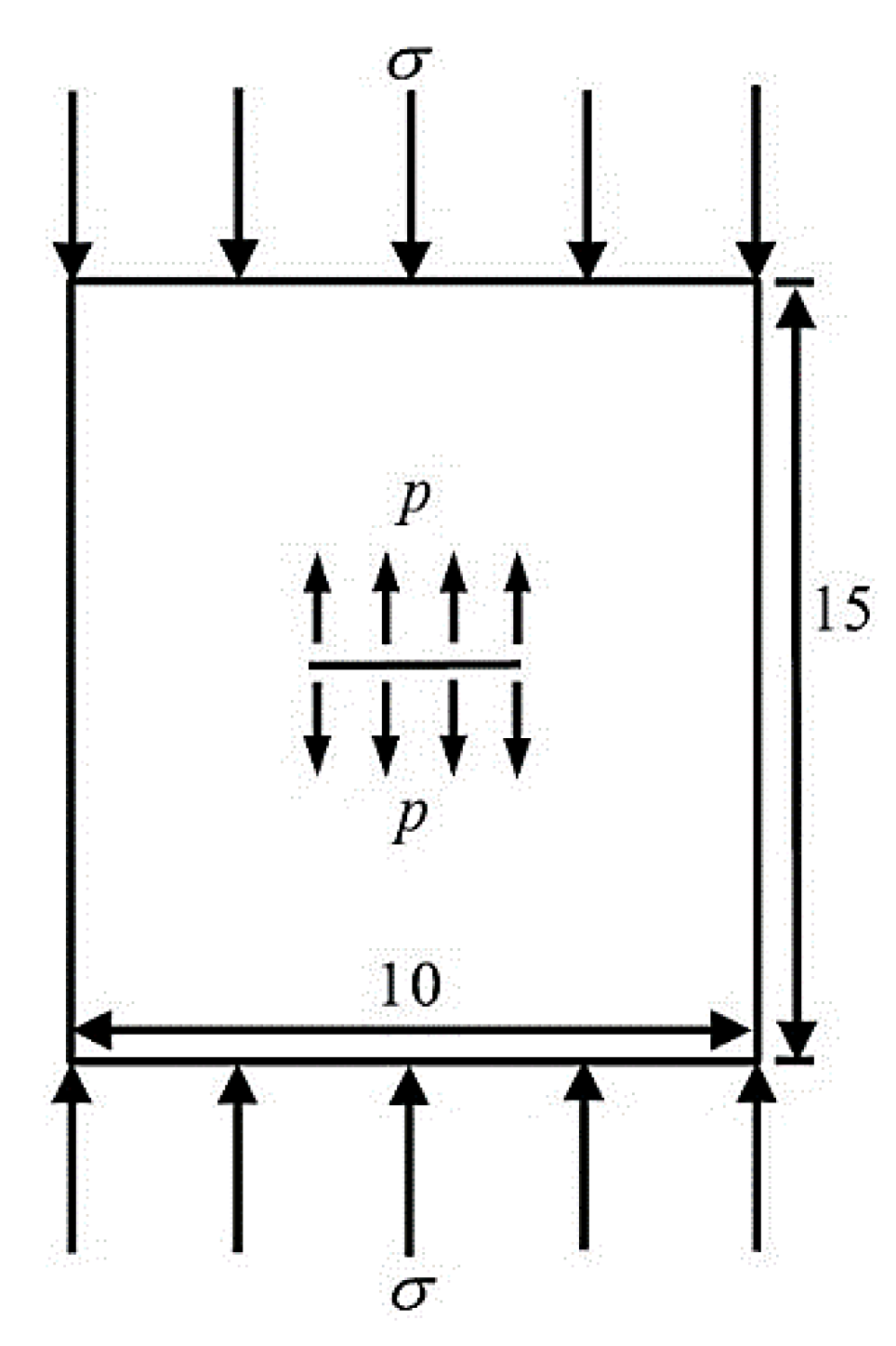

4.3. A Plate with a Central Crack

Figure 12 shows a rock specimen with a central crack. The length of the central crack is 2 meters, the height of the specimen is 15 meters, and the width is 10 meters. The top of the specimen is subjected to an external axial pressure

, and the crack surface is acted upon by a uniformly distributed water pressure

. The elastic modulus of the rock specimen is

, the Poisson's ratio is

, the fracture toughness is

, and the friction coefficient of the crack surface is

.

Considering the structural symmetry of the specimen, the right half of the specimen is taken. The mesh generation is shown in

Figure 13. The computational model is divided into 12,675 elements in total. The numerical example has undergone 4 iterations of calculation and met the convergence requirements, with a tolerance of 1.1586e

-10.

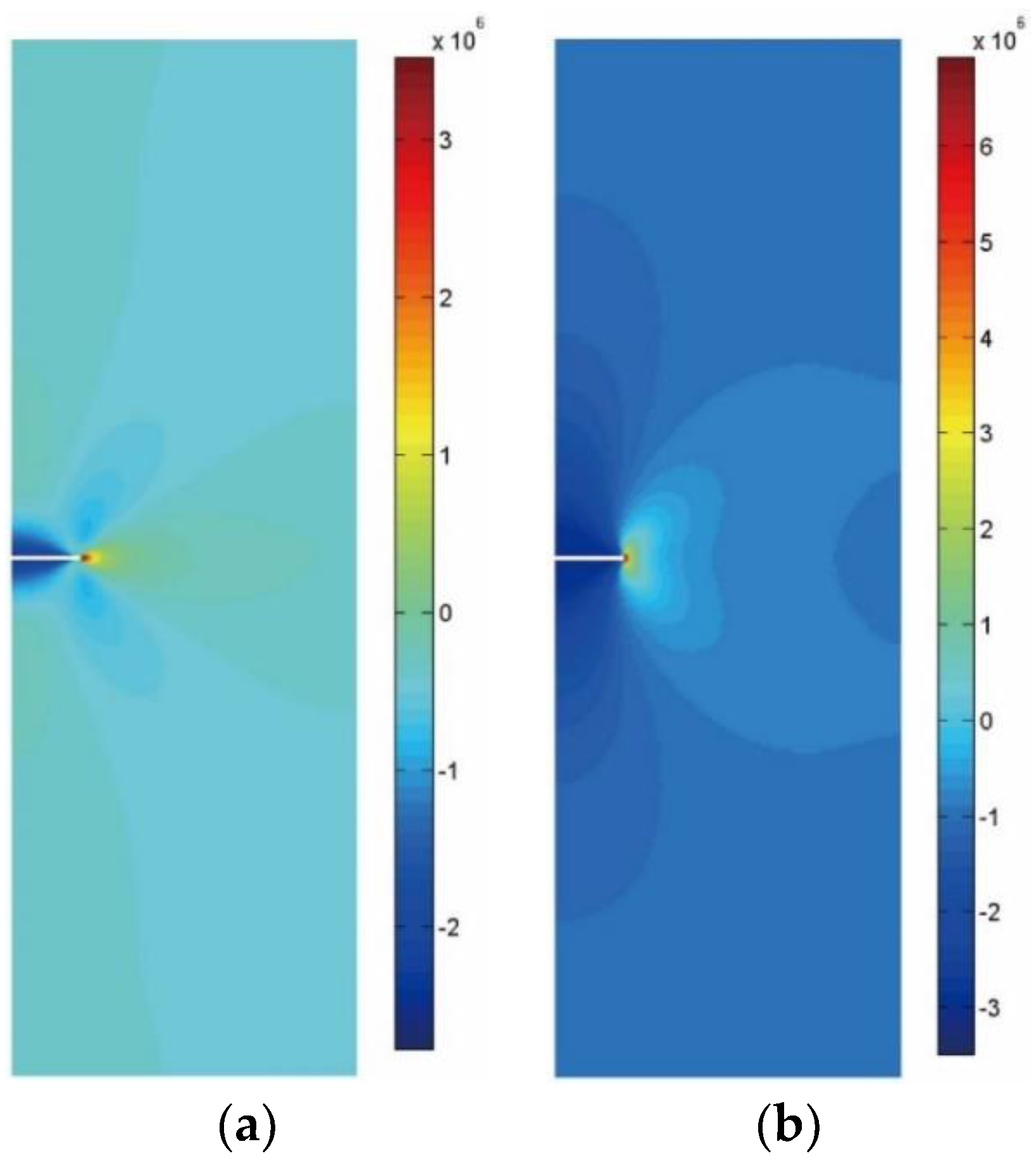

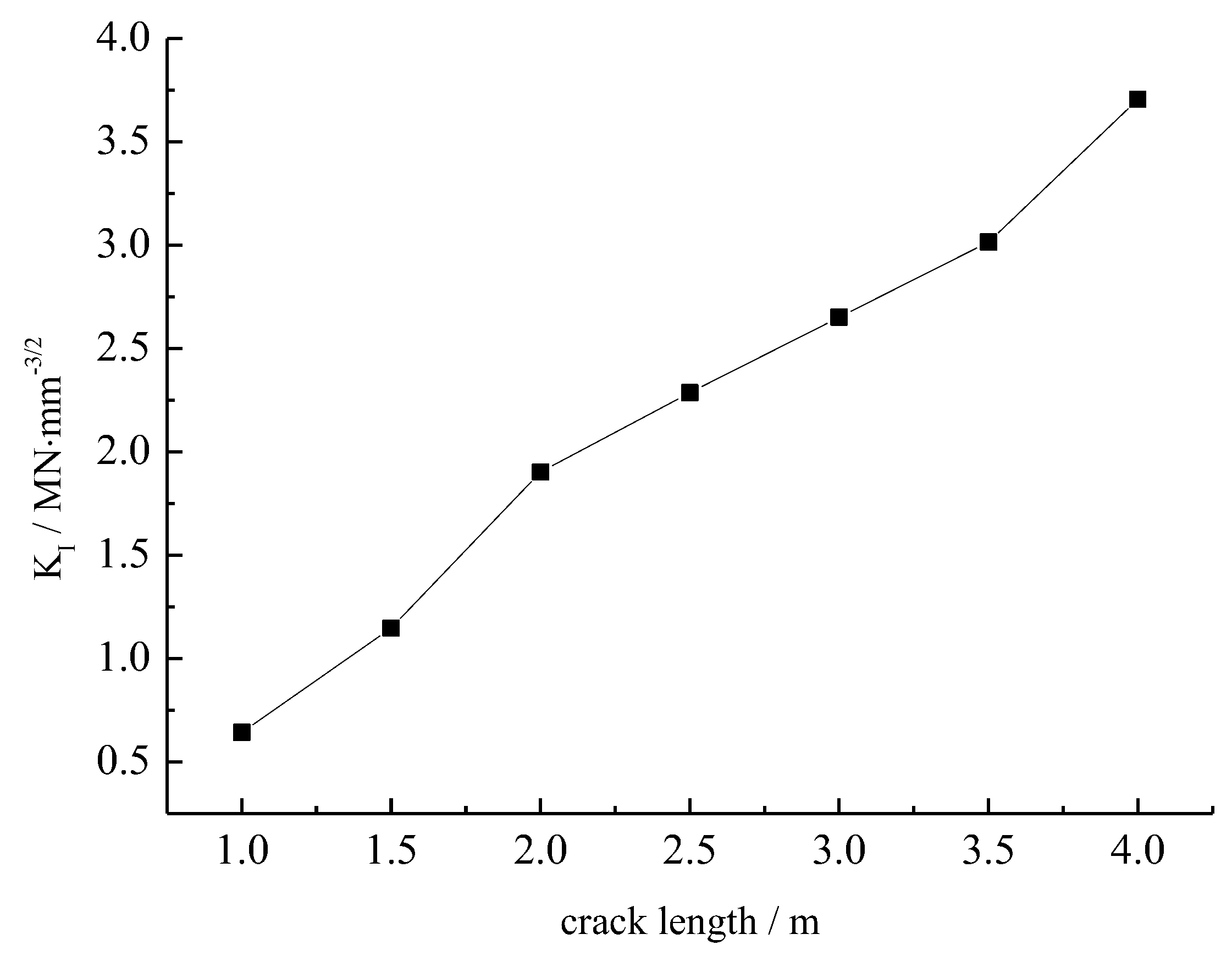

Figure 14 shows the stress contour plot. It can be seen from the figure that under the combined action of the external axial pressure and the internal water pressure, an obvious stress concentration phenomenon appears at the crack tip of the rock specimen with a central crack. The stress intensity factors under different crack lengths are shown in

Figure 15, indicating that under the combined action of the external axial pressure and the internal water pressure, the stress intensity factor at the crack tip of the rock specimen increases as the crack length increases.

The water pressure inside the crack starts from 0 MPa and gradually increases with an increment of 0.1 Mpa. When the stress intensity factor at the crack tip is greater than the fracture toughness, the water pressure inside the crack at this time is taken as the critical water pressure.

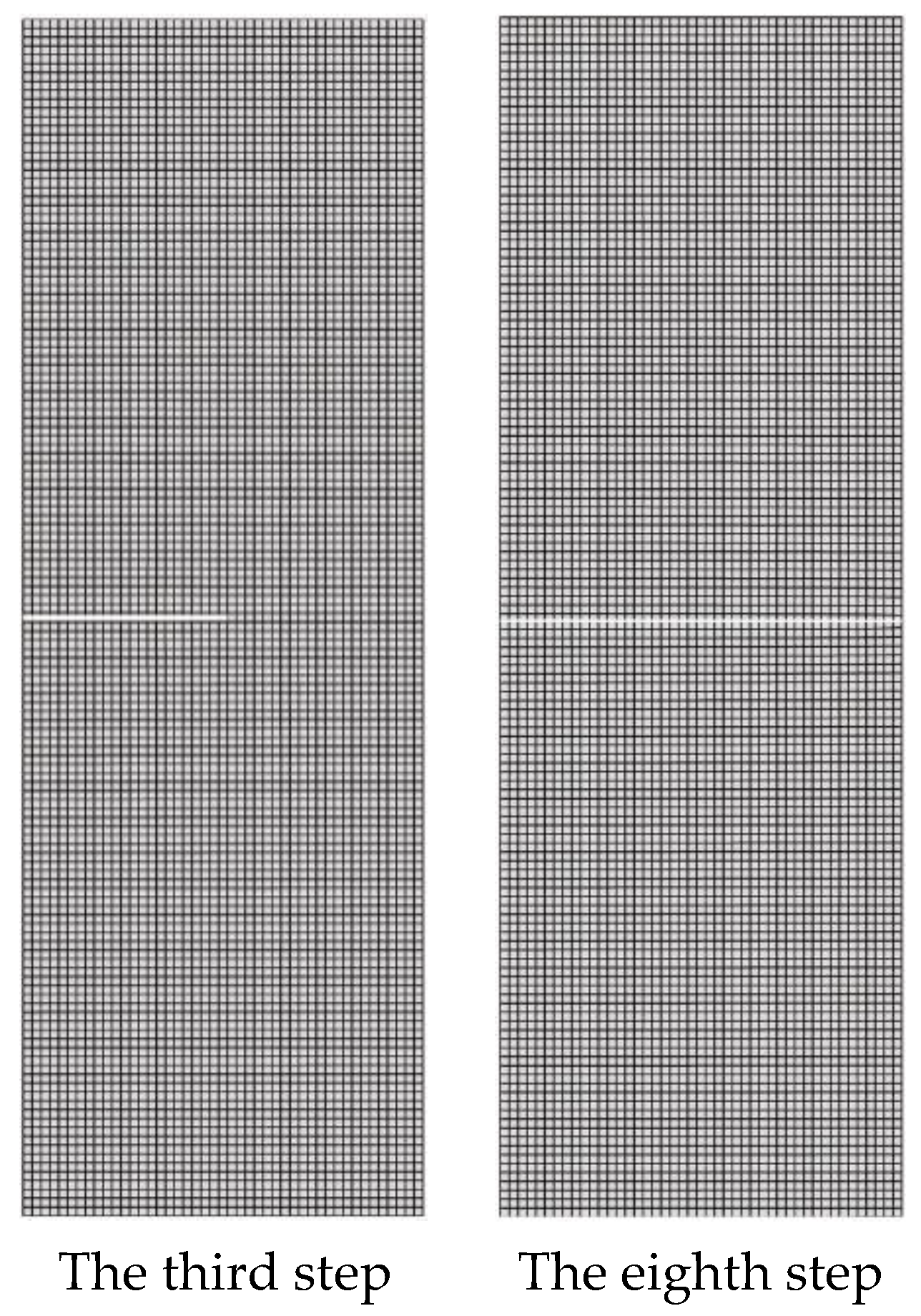

Figure 16 shows the crack propagation path under the action of the critical water pressure of 3 Mpa. The number of crack propagation steps is 8, and the crack propagation step length is taken as 0.5 m. The crack propagation criterion is the maximum circumferential stress criterion. It can be seen from the figure that the crack starts to propagate from the tip and extends along the horizontal direction. The numerical calculation results are the same as the experimental results in Reference [

14].

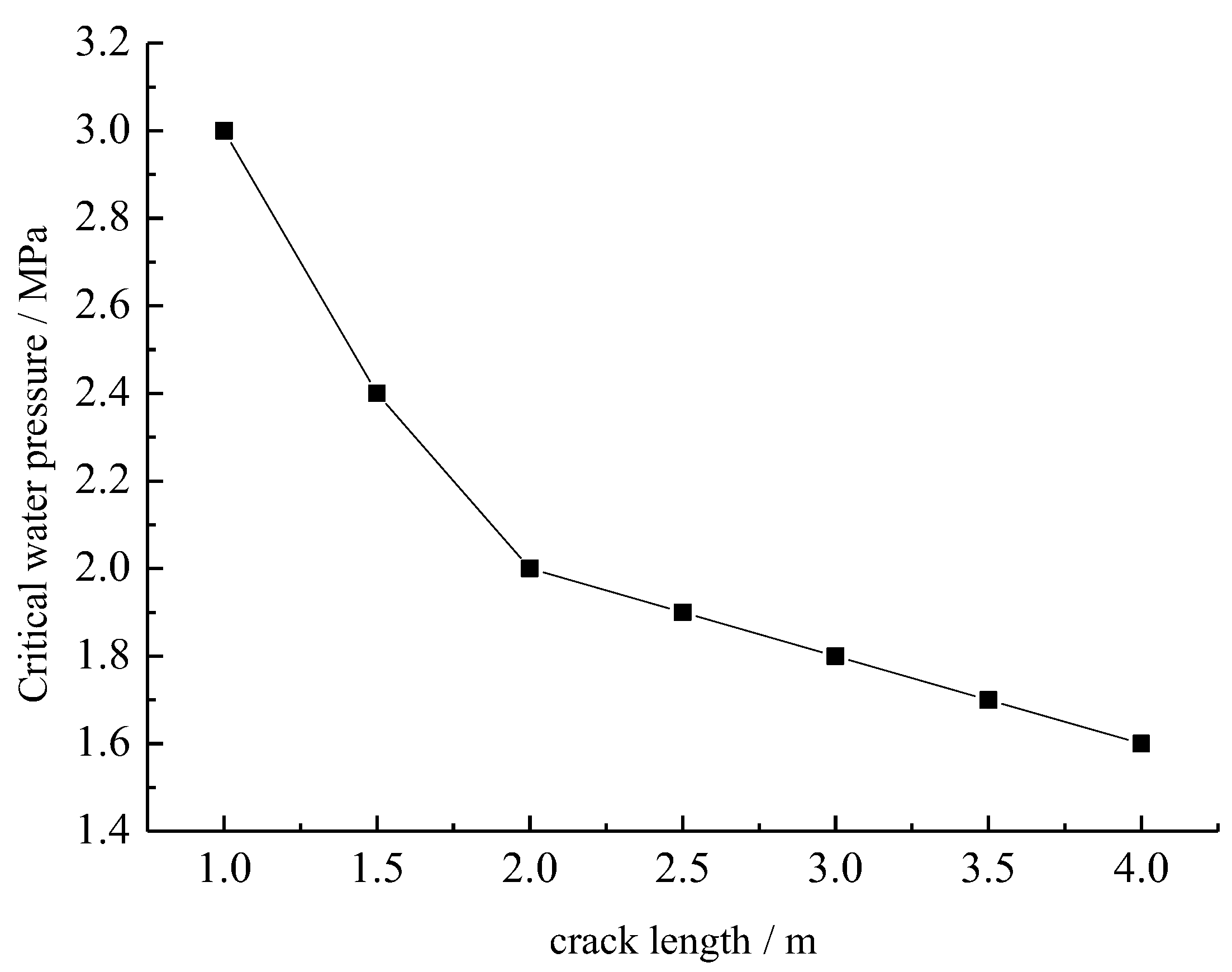

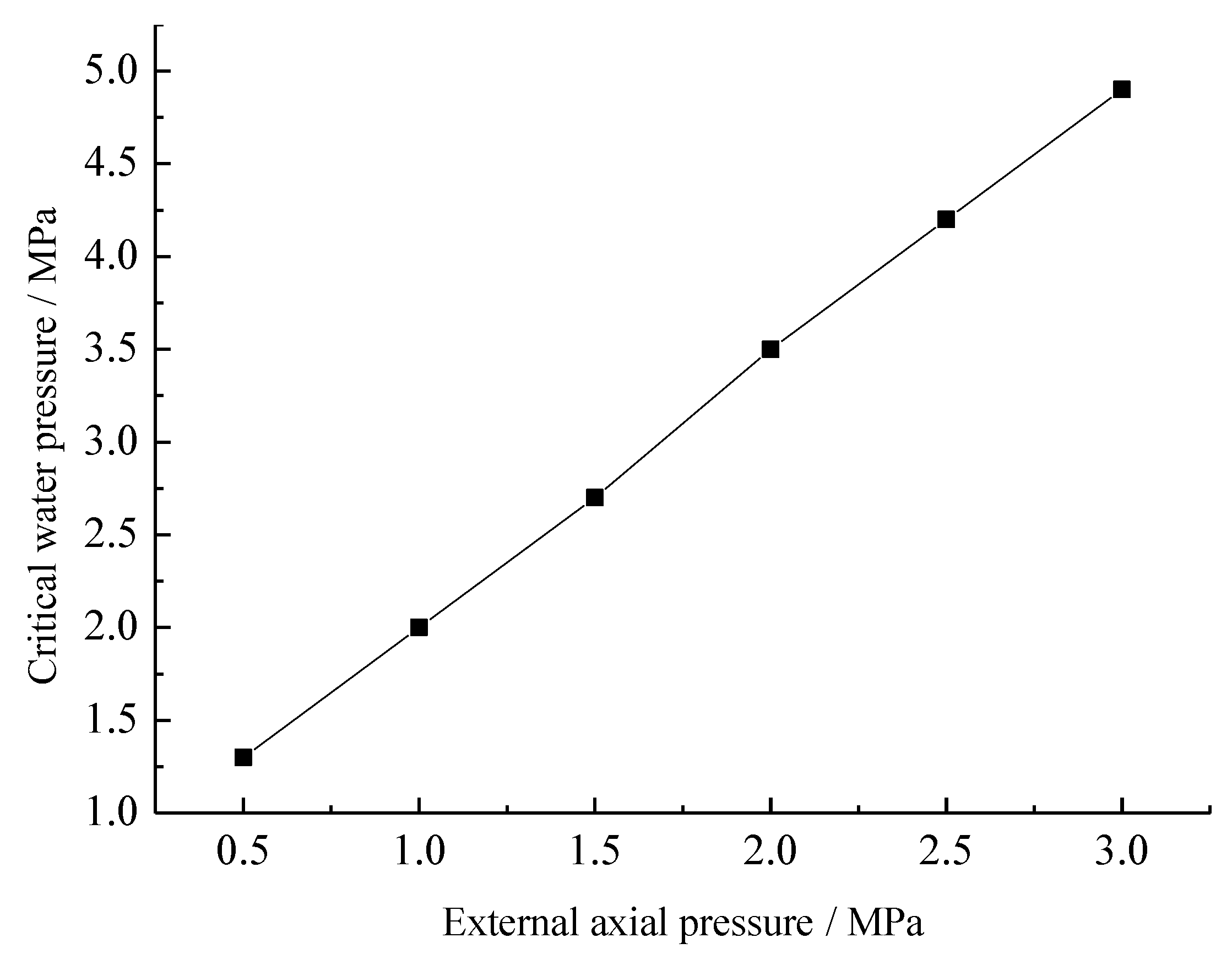

Figure 17 shows the critical water pressures under different crack lengths. It can be seen from the figure that the critical water pressure decreases as the crack length increases. The critical water pressures under different external axial pressures are shown in

Figure 18. It can be seen from the figure that as the external axial pressure increases, the critical water pressure also increases. The calculation results are consistent with the experimental results in Reference [

14]. The axial pressure has an inhibitory effect on crack initiation, and the critical water pressure will increase.

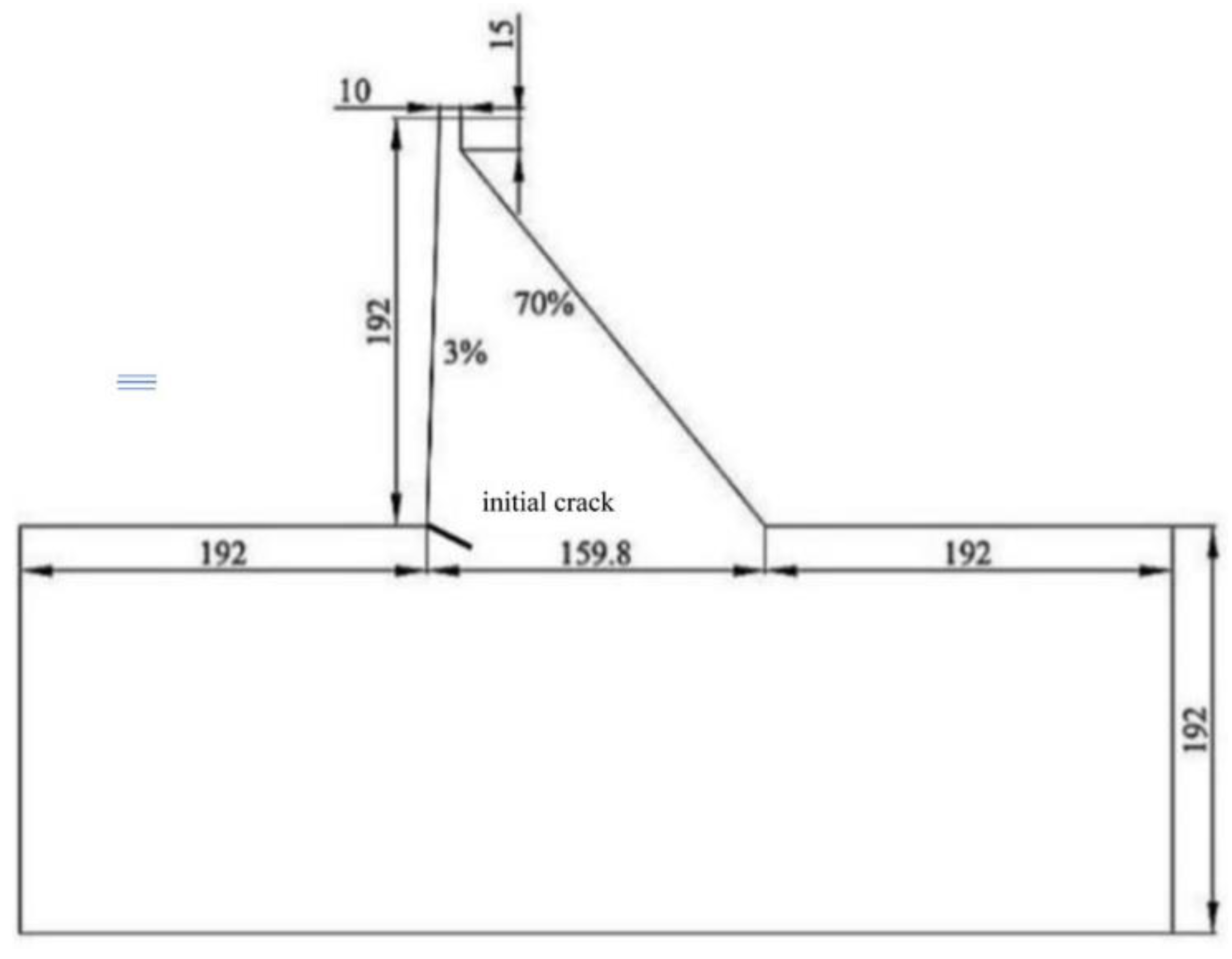

4.4. A Gravity Dam with an Initial Crack

There is an initial crack with a length of 10 meters at the foundation of a concrete gravity dam. The angle between this crack and the horizontal section of the dam heel is 30

°. The height of the dam is 192 meters, the width at the bottom of the dam is 159.8 meters, and the width at the top of the dam is 10 meters. The scope of the dam foundation extends 192 meters upstream, downstream and in the depth of the dam foundation respectively, as shown in

Figure 19. The upstream and downstream boundaries of the dam foundation are under normal constraints, and the bottom of the dam foundation is under fixed constraints. The computational parameters related to the materials of the gravity dam are shown in

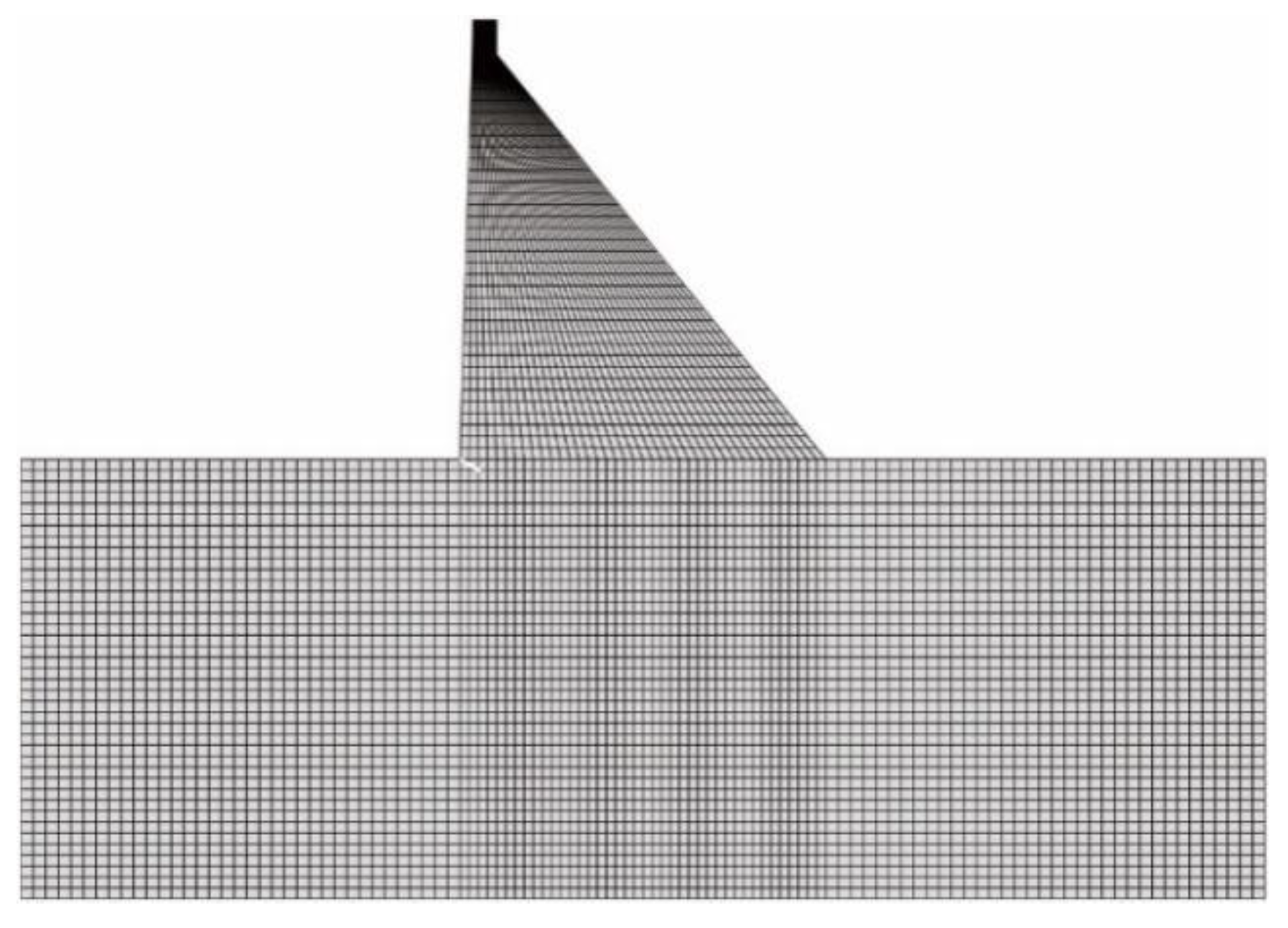

Table 3. The quadrilateral isoparametric elements are adopted for numerical analysis. The mesh generation is shown in

Figure 20, with the number of elements being 5920 and the number of nodes being 6109.

The main loads considered in the calculation include the self-weight of the dam, the upstream hydrostatic pressure and the water pressure inside the crack. For the hydrostatic pressure, the method of gravity overload is adopted. Only the water gravity is increased while the water level remains at 192 meters. The overload coefficient is the ratio before and after the increase of the water pressure. In this example, the overload coefficient is taken as 2.5.

The maximum circumferential stress criterion is adopted as the crack propagation criterion, and the crack propagation step length is taken as 3 meters. There are a total of 12 crack propagation steps.

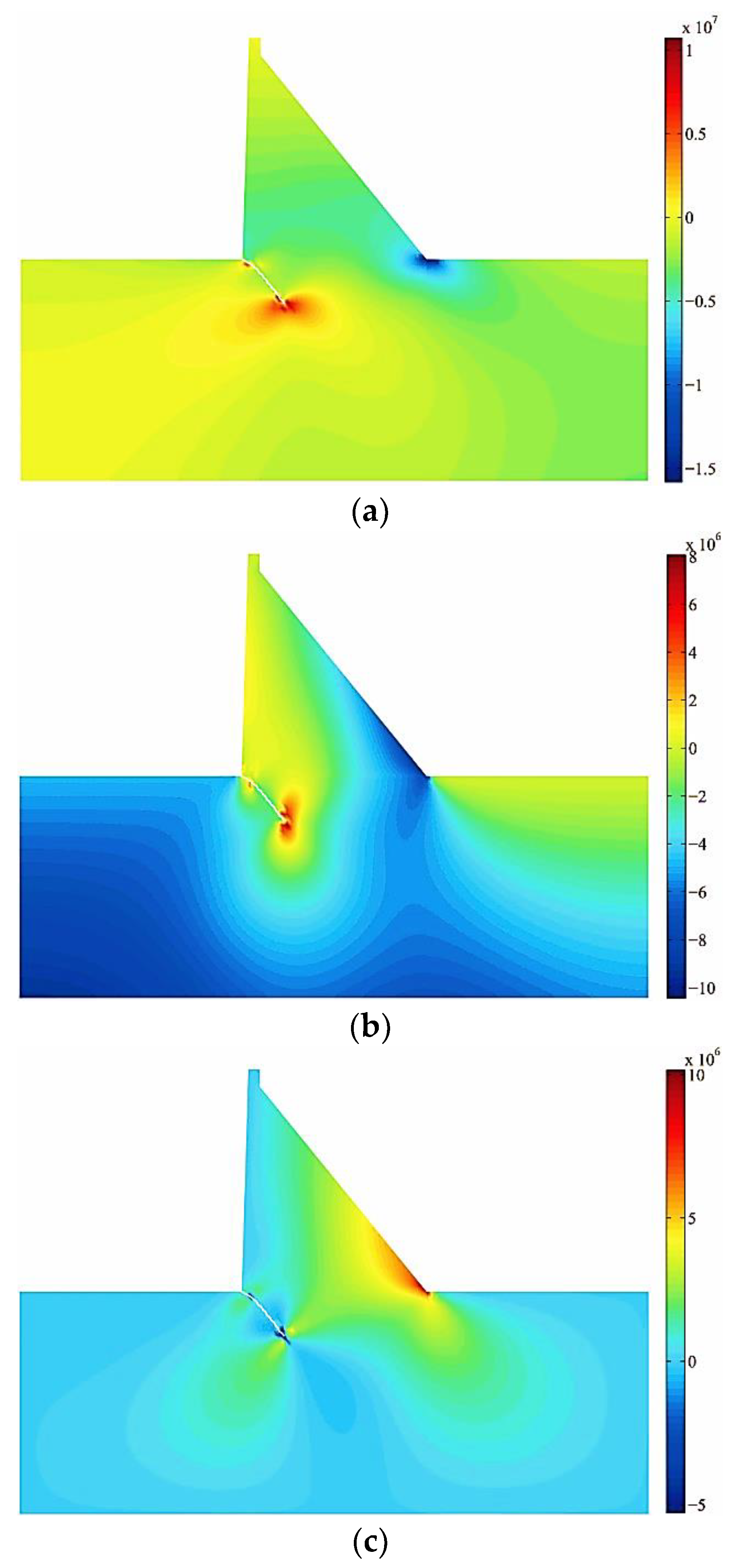

Figure 21 shows the stress contour plot of the gravity dam obtained by the extended finite element calculation. It can be seen from the figure that stress concentration phenomena occur in both the dam heel and the crack tip areas, and the stress value in the dam heel area is significantly lower than that in the crack tip area.

stress; (b) stress; (c) stress.

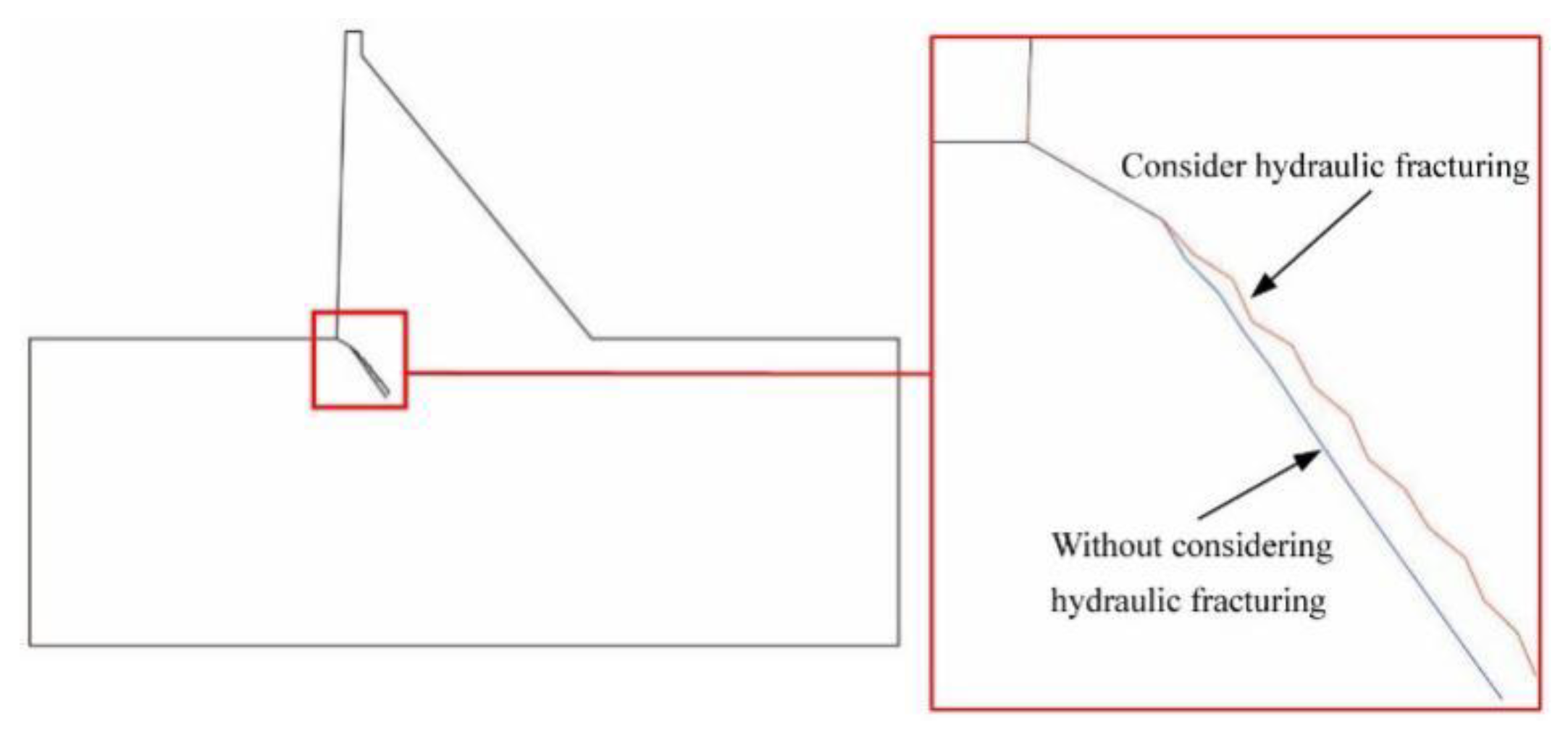

The crack propagation paths with and without considering hydraulic fracturing are shown in

Figure 22. The crack propagation angle in the case of considering hydraulic fracturing is smaller than that in the case of not considering hydraulic fracturing.

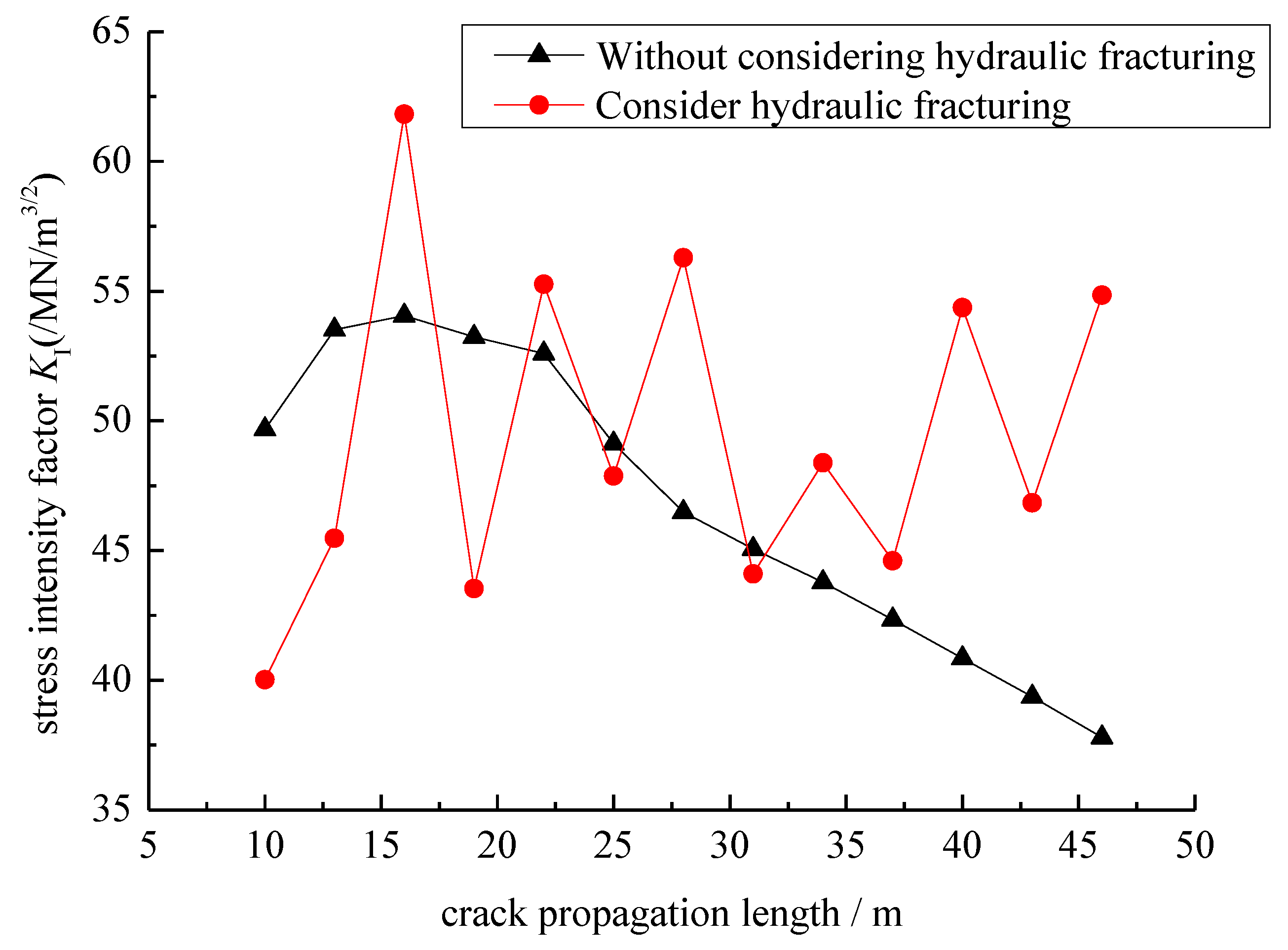

The relationship curve between the stress intensity factor and the crack length is shown in

Figure 23. The mode-I stress intensity factor in the case of considering hydraulic fracturing has fluctuations, while the mode-I stress intensity factor in the case of not considering crack hydraulic fracturing is relatively flat. As the crack continues to propagate, the mode-I stress intensity factor in the case of considering hydraulic fracturing is greater than that in the case of not considering hydraulic fracturing, indicating that hydraulic fracturing will increase the mode-I stress intensity factor at the crack tip, thereby reducing the stability of the crack at the foundation of the gravity dam.

5. Conclusions

This paper takes advantage of the extended finite element method in solving problems on moving discontinuous surfaces. By considering the virtual work principle of the water pressure distribution on the crack surface and the frictional contact of the crack surface, the governing equations for analyzing hydraulic fracturing and frictional contact problems using the extended finite element method are derived. A numerical model of the extended finite element method for solving the problems of hydraulic fracturing and frictional contact of rock cracks is established. The calculation model is applied to the hydraulic fracturing analysis of the specimens with central cracks and the gravity dams with initial cracks under the action of axial pressure. The following conclusions are obtained:

- (1)

The values of the stress intensity factors calculated by the method in this paper are consistent with the exact solutions, indicating that the method in this paper is accurate in calculating the stress intensity factors when the crack surface is subjected to the action of uniformly distributed water pressures. Moreover, as the number of elements increases, the computational error gradually decreases.

- (2)

The contact algorithm in this paper can effectively prevent the crack surfaces from interpenetrating. Its results are consistent with the calculation results of the finite element penalty function method, indicating that the contact algorithm in this paper is accurate.

- (3)

Under the combined action of the external axial pressure and the internal water pressure, the stress intensity factor at the crack tip of the rock specimen increases as the crack length increases. The critical water pressure decreases as the crack length increases; the critical water pressure increases as the external axial pressure increases. The axial pressure has an inhibitory effect on crack initiation, and the critical water pressure will increase.

- (4)

Hydraulic fracturing will increase the mode-I stress intensity factor at the crack tip and reduce the stability of the cracks at the foundation of the gravity dam.

Funding

This research was supported by the Joint Funds of the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LZJWY22E090008, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 51279100.

References

- ANDREE, G. Brittle failure of rock materials test results and constitutive models[M]. Rotterdam: A. A. Balkema, 1995: 1−5.

- Xu, Y.Q.; Zhan, D.Y. An introduction to rock mass hydraulics[M]. Chengdu: Southwest Jiaotong University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, L.B.; Yu, K.L.; Xu, D.Q. Numerical analysis of macro-meso fractures in concrete gravity dams using extended finite element method[J]. Journal of Hydroelectric Engineering, 2017, 36, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Li, G.S. Extended finite element modeling of hydraulic fracture propagation[J]. Engineering Mechanics, 2014, 31, 123−128. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.Y.; Li, J.; Xu, X.R.; et al. Influence of hydraulic fracturing on natural fracture in rock mass[J]. Rock and Soil Mechanics, 2016, 37, 3003−3010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.N.; Yu, H.; Xu, W. L.; et al. A hybrid numerical approach for hydraulic fracturing in a naturally fractured formation combining the XFEM and phase-field model[J]. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2022, 271, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecampion, B. An extended finite element method for hydraulic fracture problems[J]. Communications in Numerical Methods in Engineering, 2009, 25, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moës, N.; Dolbow, J.; Belytschko, T. A finite element method for crack growth without remeshing[J]. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 1999, 46, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Chu, Y. A.; Moran, B.; et al. Enriched element-free Galerkin methods for crack tip fields[J]. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 1997, 40, 1483–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.X.; Luo, X.Q.; Chen, Z.H. Hydraulic fracturing coupling model of rock mass based on extended finite element method[J]. Rock and Soil Mechanics, 2019, 40, 799–808. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, A. X.; Luo, X. Q. A mathematical programming approach for frictional contact problems with the extended finite element method [J]. Archive of Applied Mechanics, 2016, 86, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Chu, Y. A.; Moran, B.; et al. Enriched element-free Galerkin methods for crack tip fields[J]. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 1997, 40, 1483–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, J.Q. Calculation of stress intensity factor for crack in a finite plate[J]. Chinese Journal of Rock Mechanics and Engineering, 2005, 24, 963–968. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.Q.; Tao, Y.C.; Liu, D.T.; et al. Hydraulic fracture test of rock-like materials under uniaxial compression[J]. Advances in Science and Technology of Water Resources, 2018, 38, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Local polar coordinates.

Figure 1.

Local polar coordinates.

Figure 2.

Gaussian points on the crack surface.

Figure 2.

Gaussian points on the crack surface.

Figure 5.

The effect of mesh elements on Normalized SIF.

Figure 5.

The effect of mesh elements on Normalized SIF.

Figure 6.

The SIFs under different water pressures on the crack.

Figure 6.

The SIFs under different water pressures on the crack.

Figure 7.

Rectangular plate with through crack.

Figure 7.

Rectangular plate with through crack.

Figure 8.

Mesh generation. (a) Extended finite element mesh; (b) Finite element mesh.

Figure 8.

Mesh generation. (a) Extended finite element mesh; (b) Finite element mesh.

Figure 9.

Displacement contour (Unit: m). (a) Horizontal displacement; (b) Vertical displacement.

Figure 9.

Displacement contour (Unit: m). (a) Horizontal displacement; (b) Vertical displacement.

Figure 10.

Stress contour (Unit: Pa). (a) Normal stress; (b) Normal stress σyy.

Figure 10.

Stress contour (Unit: Pa). (a) Normal stress; (b) Normal stress σyy.

Figure 11.

Contact stresses on the crack surface. (a) Normal contact stress; (b) Tangential contact stress.

Figure 11.

Contact stresses on the crack surface. (a) Normal contact stress; (b) Tangential contact stress.

Figure 12.

Specimen with center crack.

Figure 12.

Specimen with center crack.

Figure 13.

Mesh generation.

Figure 13.

Mesh generation.

Figure 14.

Stress contour (Unit: Pa). (a) normal stress σxx; (b) normal stress σyy.

Figure 14.

Stress contour (Unit: Pa). (a) normal stress σxx; (b) normal stress σyy.

Figure 15.

The SIFs under different crack lengths.

Figure 15.

The SIFs under different crack lengths.

Figure 16.

The crack propagation path.

Figure 16.

The crack propagation path.

Figure 17.

Critical internal water pressure under different crack lengths.

Figure 17.

Critical internal water pressure under different crack lengths.

Figure 18.

Critical internal water pressure under different external axial pressures.

Figure 18.

Critical internal water pressure under different external axial pressures.

Figure 19.

gravity dam with initial crack (unit: m).

Figure 19.

gravity dam with initial crack (unit: m).

Figure 20.

Mesh division.

Figure 20.

Mesh division.

Figure 21.

Stress contour for gravity dam (Unit: Pa). (a)

Figure 21.

Stress contour for gravity dam (Unit: Pa). (a)

Figure 22.

Crack extension path of gravity dam.

Figure 22.

Crack extension path of gravity dam.

Figure 23.

Relationship curve between stress intensity factor and crack length.

Figure 23.

Relationship curve between stress intensity factor and crack length.

Table 2.

Computational results of the slipping contact points 1-20.

Table 2.

Computational results of the slipping contact points 1-20.

|

/N

|

/N

|

/m

|

/m

|

| 1 |

-1.6978E+04 |

2.8712E+04 |

2.1843E-07 |

-2.8033E-15 |

| 2 |

-1.3372E+04 |

4.0254E+04 |

2.9343E-07 |

-2.6368E-15 |

| 3 |

-1.4746E+04 |

4.7598E+04 |

3.4758E-07 |

-2.5171E-15 |

| 4 |

-1.8951E+04 |

5.7070E+04 |

4.2055E-07 |

-2.3471E-15 |

| 5 |

-2.1670E+04 |

6.3780E+04 |

4.5915E-07 |

-2.2239E-15 |

| 6 |

-2.4894E+04 |

7.2643E+04 |

4.9167E-07 |

-2.0582E-15 |

| 7 |

-2.6968E+04 |

7.8693E+04 |

5.0011E-07 |

-1.9333E-15 |

| 8 |

-2.9409E+04 |

8.6359E+04 |

4.9064E-07 |

-1.7677E-15 |

| 9 |

-3.0967E+04 |

9.2017E+04 |

4.6729E-07 |

-1.6463E-15 |

| 10 |

-3.2781E+04 |

9.9811E+04 |

4.1295E-07 |

-1.4754E-15 |

| 11 |

-3.3636E+04 |

1.0452E+05 |

3.5693E-07 |

-1.3540E-15 |

| 12 |

-3.4159E+04 |

1.0958E+05 |

2.5821E-07 |

-1.1857E-15 |

| 13 |

-3.5201E+04 |

1.1714E+05 |

1.7515E-07 |

-1.0625E-15 |

| 14 |

-4.3069E+04 |

1.3107E+05 |

4.6932E-08 |

-8.9208E-16 |

| 15 |

-4.3905E+04 |

1.2898E+05 |

5.4210E-19 |

-7.6978E-16 |

| 16 |

-2.6140E+04 |

1.1299E+05 |

5.5904E-19 |

-6.0238E-16 |

| 17 |

-2.0941E+04 |

1.4269E+05 |

4.5740E-19 |

-4.6339E-16 |

| 18 |

-2.4505E+04 |

2.3981E+05 |

3.3881E-20 |

-2.4817E-16 |

| 19 |

-1.9113E+04 |

2.2663E+05 |

-6.2680E-20 |

-1.4095E-16 |

| 20 |

-8.1822E+02 |

9.3493E+04 |

2.8799E-20 |

-6.2992E-17 |

Table 3.

Mechanical parameters of gravity dam materials.

Table 3.

Mechanical parameters of gravity dam materials.

| section |

elastic modulus /GPa |

Poisson's ratio |

unit weight /()

|

fracture toughness /()

|

| dam body |

22 |

0.167 |

24 |

21500 |

| dam foundation |

24 |

0.2 |

28 |

22800 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).