Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

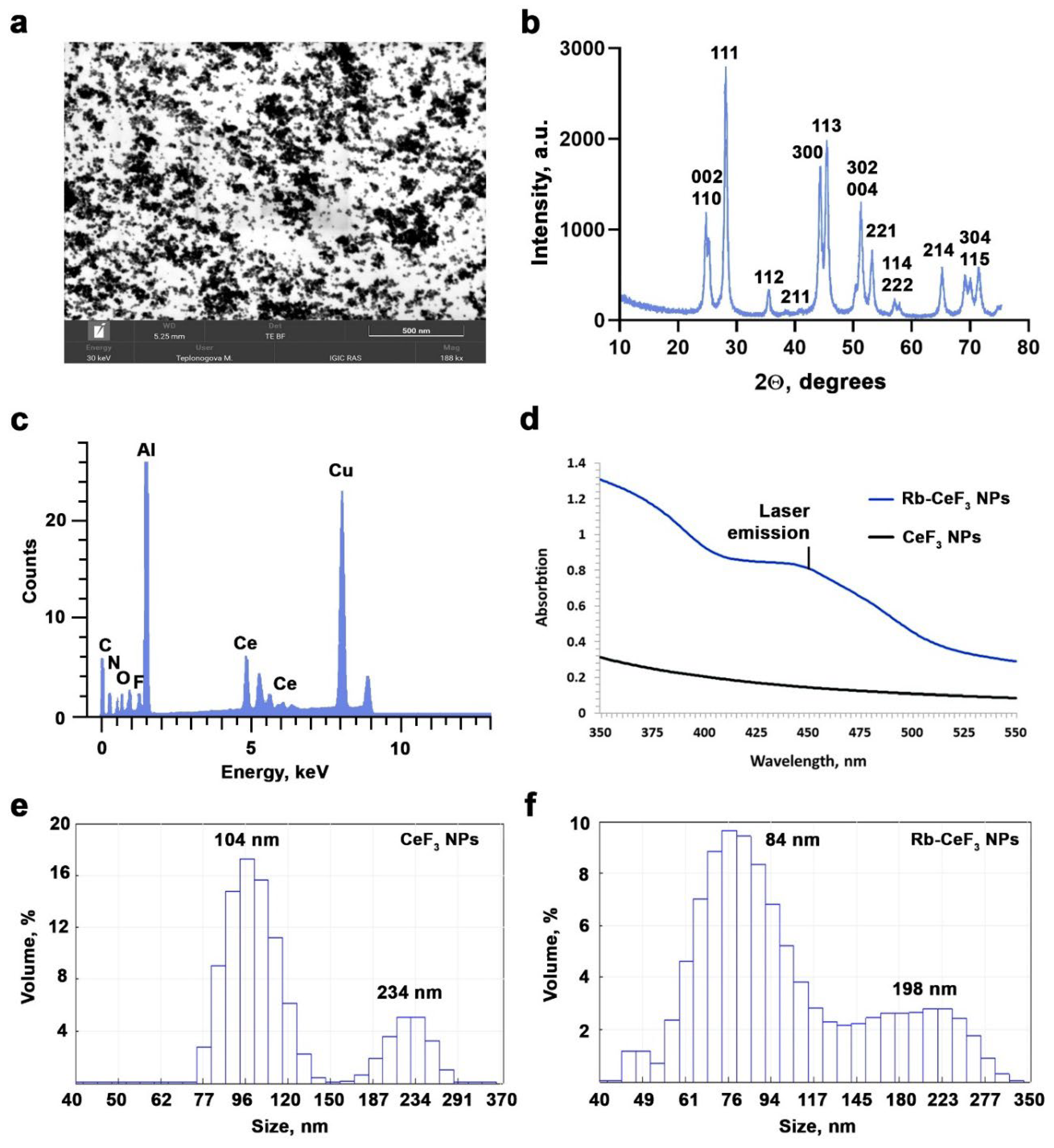

2.1. Synthesis of Riboflavin-Functionalized CeF3 Nanoparticles

2.2. Physico-Chemical Analysis

2.3. Cell Culture

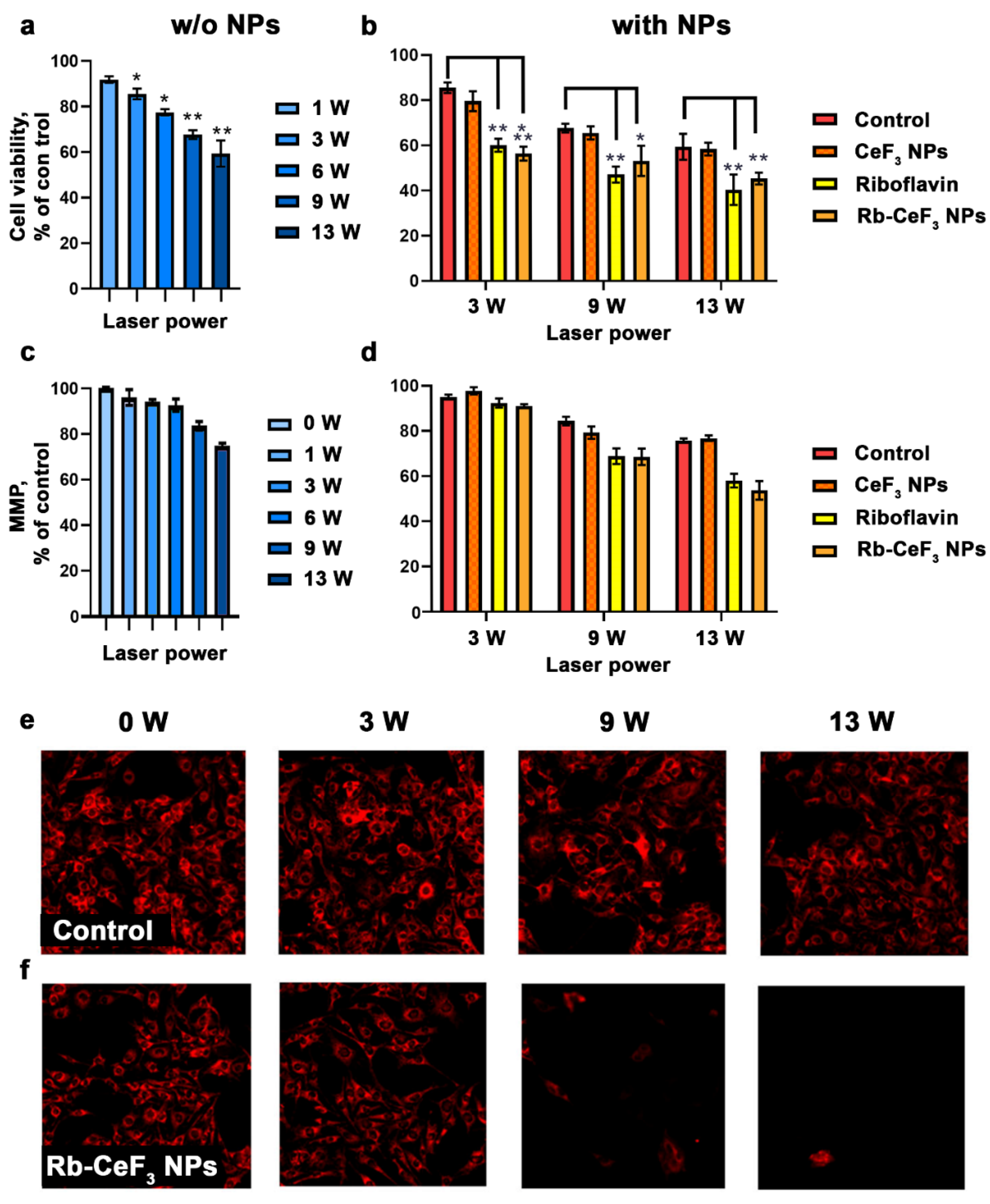

2.4. Laser Light Irradiation

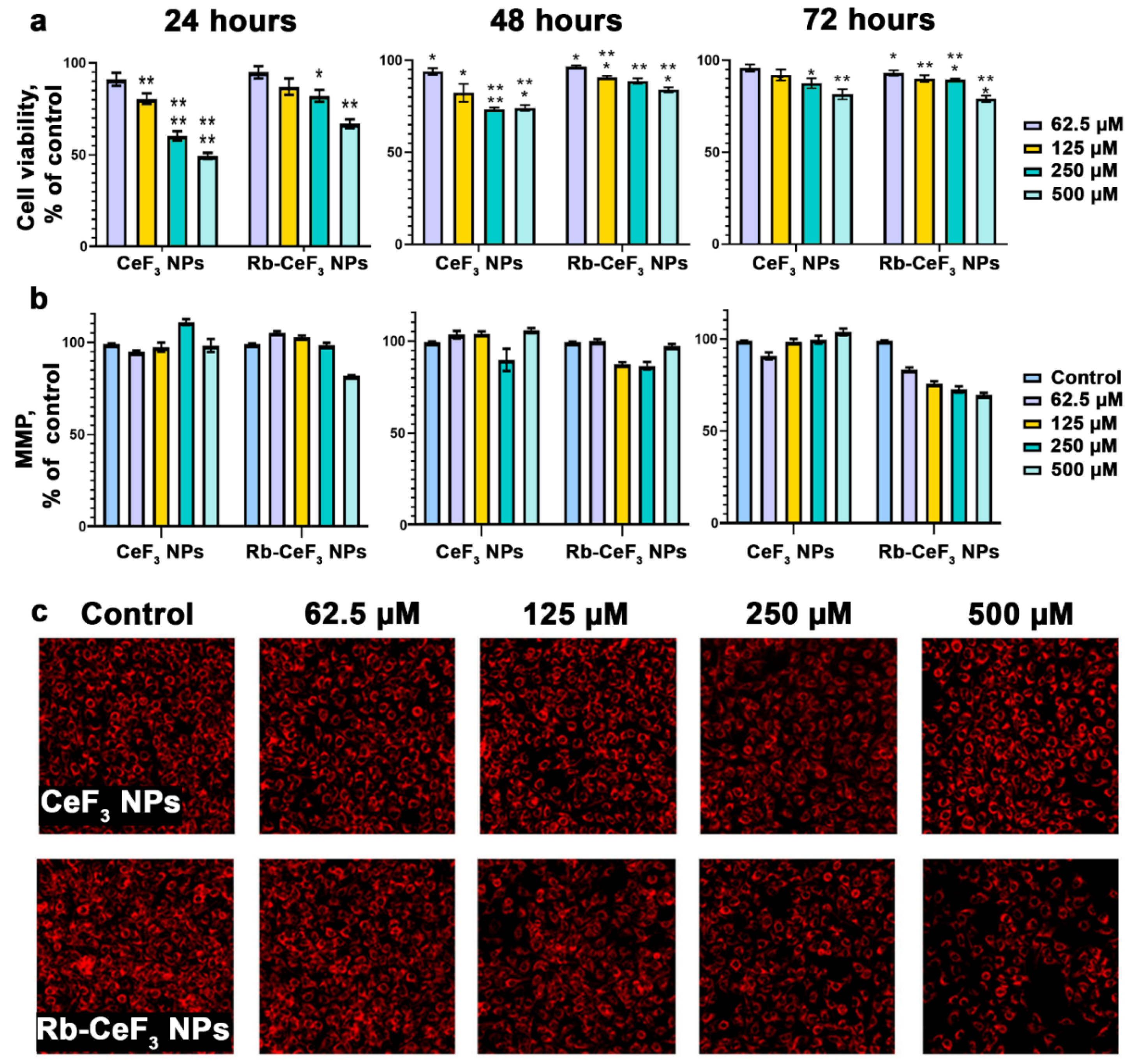

2.5. Cell Viability Assay

2.6. Analysis of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

2.7. Cell Death Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

References

- Gunaydin, G.; Gedik, M.E.; Ayan, S. Photodynamic Therapy—Current Limitations and Novel Approaches. Front. Chem. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, D.E.J.G.J.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003, 3, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer: An Update. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarranz, Á.; Jaén, P.; Sanz-Rodríguez, F.; Cuevas, J.; González, S. Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. Basic Principles and Applications. Clin Transl Oncol 2008, 10, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.B.; Brown, E.A.; Walker, I. The Present and Future Role of Photodynamic Therapy in Cancer Treatment. Lancet Oncol 2004, 5, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Lee, C.-S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, P. Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2019, 8, 1900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, H.; Hamblin, M.R. New Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Biochemical Journal 2016, 473, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konan, Y.N.; Gurny, R.; Allémann, E. State of the Art in the Delivery of Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2002, 66, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassie, J.A.; Whitelock, J.M.; Lord, M.S. Targeted Delivery and Redox Activity of Folic Acid-Functionalized Nanoceria in Tumor Cells. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jin, F.; Liu, D.; Shu, G.; Wang, X.; Qi, J.; Sun, M.; Yang, P.; Jiang, S.; Ying, X.; et al. ROS-Responsive Nano-Drug Delivery System Combining Mitochondria-Targeting Ceria Nanoparticles with Atorvastatin for Acute Kidney Injury. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, C.; Zeng, Y.-P.; Hao, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-W.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Li, R. Nanoceria-Mediated Drug Delivery for Targeted Photodynamic Therapy on Drug-Resistant Breast Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 31510–31523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Li, P.; Hu, B.; Liu, T.; Huang, Z.; Shan, C.; Cao, J.; Cheng, B.; Liu, W.; Tang, Y. A Smart Photosensitizer–Cerium Oxide Nanoprobe for Highly Selective and Efficient Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 7295–7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukavin, N.N.; Ivanov, V.K.; Popov, A.L. Calcein-Modified CeO2 for Intracellular ROS Detection: Mechanisms of Action and Cytotoxicity Analysis In Vitro. Cells 2023, 12, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukavin, N.N.; Popov, A.L.; Shcherbakov, A.B.; Ivanova, O.S.; Filippova, A.D.; Ivanov, V.K. CeO2-Calcein Nanoconjugate Protective Action against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Vitro. Nanosystems: Phys. Chem. Math. 2022, 13, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, A.B.; Zholobak, N.M.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Ryabova, A.V.; Ivanov, V.K. Cerium Fluoride Nanoparticles Protect Cells against Oxidative Stress. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2015, 50, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.R.; Kudinov, K.; Tyagi, P.; Hill, C.K.; Bradforth, S.E.; Nadeau, J.L. Photoluminescence of Cerium Fluoride and Cerium-Doped Lanthanum Fluoride Nanoparticles and Investigation of Energy Transfer to Photosensitizer Molecules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 12441–12453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ansari, A.A.; Malik, A.; Syed, R.; Ola, M.S.; Kumar, A.; AlGhamdi, K.M.; Khan, S. Highly Water-Soluble Luminescent Silica-Coated Cerium Fluoride Nanoparticles Synthesis, Characterizations, and In Vitro Evaluation of Possible Cytotoxicity. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19174–19180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukavin, N.N.; Kolmanovich, D.D.; Filippova, A.D.; Teplonogova, M.A.; Ivanov, V.K.; Popov, A.L. Synthesis of Redox-Active Ce0.75Bi0.15Tb0.1F3 Nanoparticles and Their Biocompatibility Study in Vitro. Nanosystems: Phys. Chem. Math. 2024, 15, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.L.; Zholobak, N.M.; Shcherbakov, A.B.; Kozlova, T.O.; Kolmanovich, D.D.; Ermakov, A.M.; Popova, N.R.; Chukavin, N.N.; Bazikyan, E.A.; Ivanov, V.K. The Strong Protective Action of Ce3+/F- Combined Treatment on Tooth Enamel and Epithelial Cells. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2022, 12, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xu, H.; Cao, W.; Gao, W.; Tang, B. Cerium Fluoride Nanoparticles as a Theranostic Material for Optical Imaging of Vulnerable Atherosclerosis Plaques. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2023, 106, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukavin, N.N.; Filippova, K.O.; Ermakov, A.M.; Karmanova, E.E.; Popova, N.R.; Anikina, V.A.; Ivanova, O.S.; Ivanov, V.K.; Popov, A.L. Redox-Active Cerium Fluoride Nanoparticles Selectively Modulate Cellular Response against X-Ray Irradiation In Vitro. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, D.R.; Libardi, S.H.; Skibsted, L.H. Riboflavin as a Photosensitizer. Effects on Human Health and Food Quality. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas Aiello, M.B.; Castrogiovanni, D.; Parisi, J.; Azcárate, J.C.; García Einschlag, F.S.; Gensch, T.; Bosio, G.N.; Mártire, D.O. Photodynamic Therapy in HeLa Cells Incubated with Riboflavin and Pectin-Coated Silver Nanoparticles. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2018, 94, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, J.; Zhu, T.; Yu, S.-S.; Zuo, C.; Yao, R.; Qian, H. A New Trick (Hydroxyl Radical Generation) of an Old Vitamin (B2) for near-Infrared-Triggered Photodynamic Therapy. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 102647–102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, F. Pathogen Inactivation of Blood Components: Current Status and Introduction of an Approach Using Riboflavin as a Photosensitizer. Int J Hematol 2002, 76, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, R.W.; Kochevar, I.E. Medical Applications of Rose Bengal- and Riboflavin-Photosensitized Protein Crosslinking. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2019, 95, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; P, M.R.; Rizvi, A.; Alam, Md.M.; Rizvi, M.; Naseem, I. ROS Mediated Antibacterial Activity of Photoilluminated Riboflavin: A Photodynamic Mechanism against Nosocomial Infections. Toxicology Reports 2019, 6, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, L.; He, C.; Tai, S.; Zhu, L.; Ma, C.; Yang, T.; Cheng, F.; Sun, X.; Cui, R.; et al. An Experimental Study on Riboflavin Photosensitization Treatment for Inactivation of Circulating HCT116 Tumor Cells. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2019, 196, 111496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darguzyte, M.; Drude, N.; Lammers, T.; Kiessling, F. Riboflavin-Targeted Drug Delivery. Cancers 2020, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareford, L.M.; Phelps, M.A.; Foraker, A.B.; Swaan, P.W. Intracellular Processing of Riboflavin in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2008, 5, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannasom, N.; Kao, I.; Pruß, A.; Georgieva, R.; Bäumler, H. Riboflavin: The Health Benefits of a Forgotten Natural Vitamin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.T.; Zempleni, J. Riboflavin. Adv Nutr 2016, 7, 973–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remucal, C.K.; McNeill, K. Photosensitized Amino Acid Degradation in the Presence of Riboflavin and Its Derivatives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5230–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insińska-Rak, M.; Sikorski, M.; Wolnicka-Glubisz, A. Riboflavin and Its Derivates as Potential Photosensitizers in the Photodynamic Treatment of Skin Cancers. Cells 2023, 12, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.Y.; Farah, N.; Chin, V.K.; Lim, C.W.; Chong, P.P.; Basir, R.; Lim, W.F.; Loo, Y.S. Medicinal Benefits, Biological, and Nanoencapsulation Functions of Riboflavin with Its Toxicity Profile: A Narrative Review. Nutrition Research 2023, 119, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beztsinna, N.; Solé, M.; Taib, N.; Bestel, I. Bioengineered Riboflavin in Nanotechnology. Biomaterials 2016, 80, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas Aiello, M.B.; Romero, J.J.; Bertolotti, S.G.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Mártire, D.O. Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on the Photophysics of Riboflavin: Consequences on the ROS Generation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 21967–21975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasov, R.A.; Sholina, N.V.; Khochenkov, D.A.; Alova, A.V.; Gorelkin, P.V.; Erofeev, A.S.; Generalova, A.N.; Khaydukov, E.V. Photodynamic Therapy of Melanoma by Blue-Light Photoactivation of Flavin Mononucleotide. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, D.; Shishido, S.M.; Queiroz, K.C.S.; Oliveira, D.N.; Faria, A.L.C.; Catharino, R.R.; Spek, C.A.; Ferreira, C.V. Irradiated Riboflavin Diminishes the Aggressiveness of Melanoma In Vitro and In Vivo. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e54269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, M.; Fujikura, T.; Fujiwara, H. Augmentation of the Inhibitory Effect of Blue Light on the Growth of B16 Melanoma Cells by Riboflavin. International Journal of Oncology 2003, 22, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, S.; Liu, M. The Review of the Light Parameters and Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation on Melanoma Cells. Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine 2022, 38, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).