Submitted:

19 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

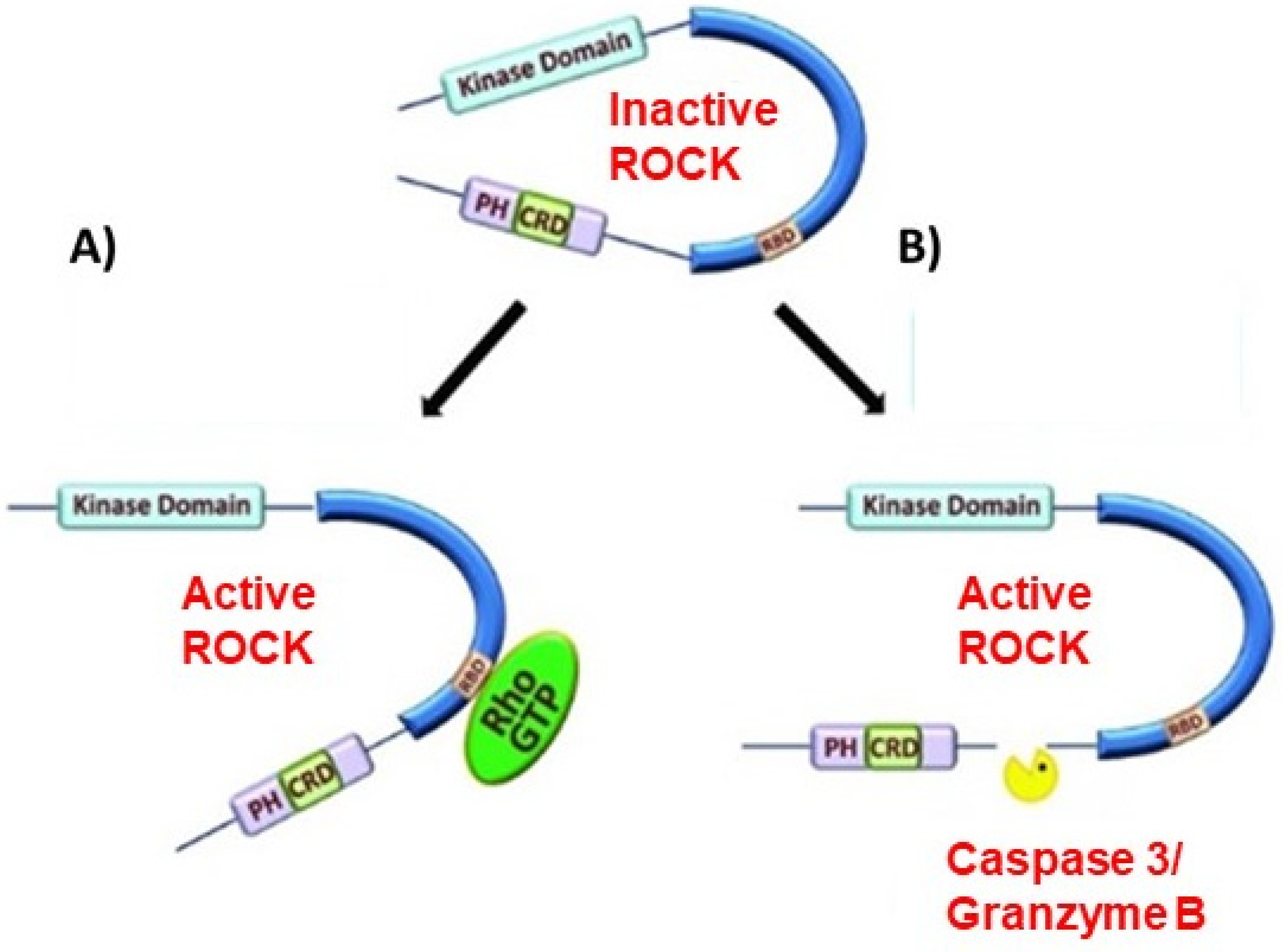

RhoA/ROCK Pathway in Neuronal Regulation

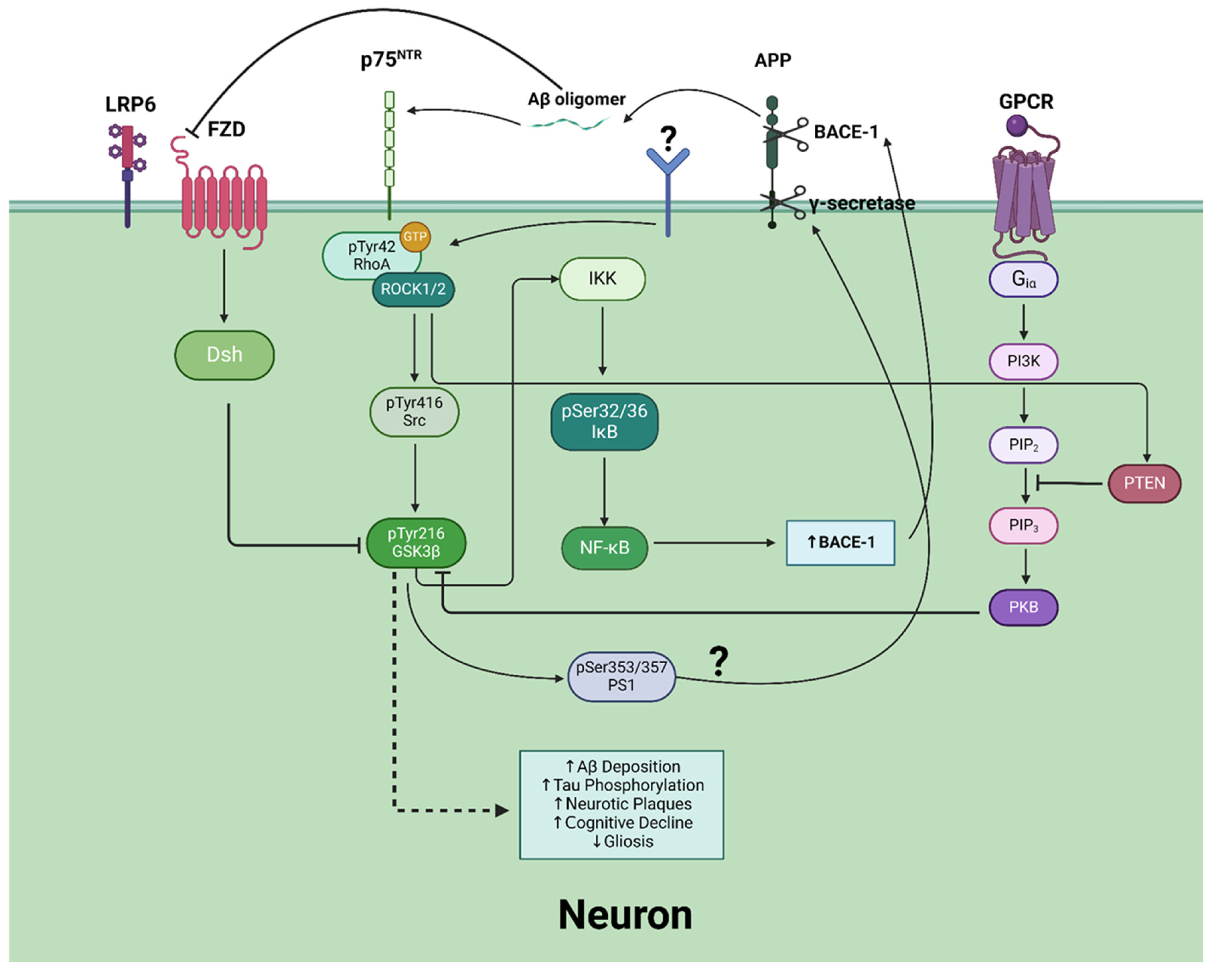

GSK3β Regulation

GSK3β in Neuronal Development

RhoA/ROCK/GSK3β in Alzheimer’s Disease

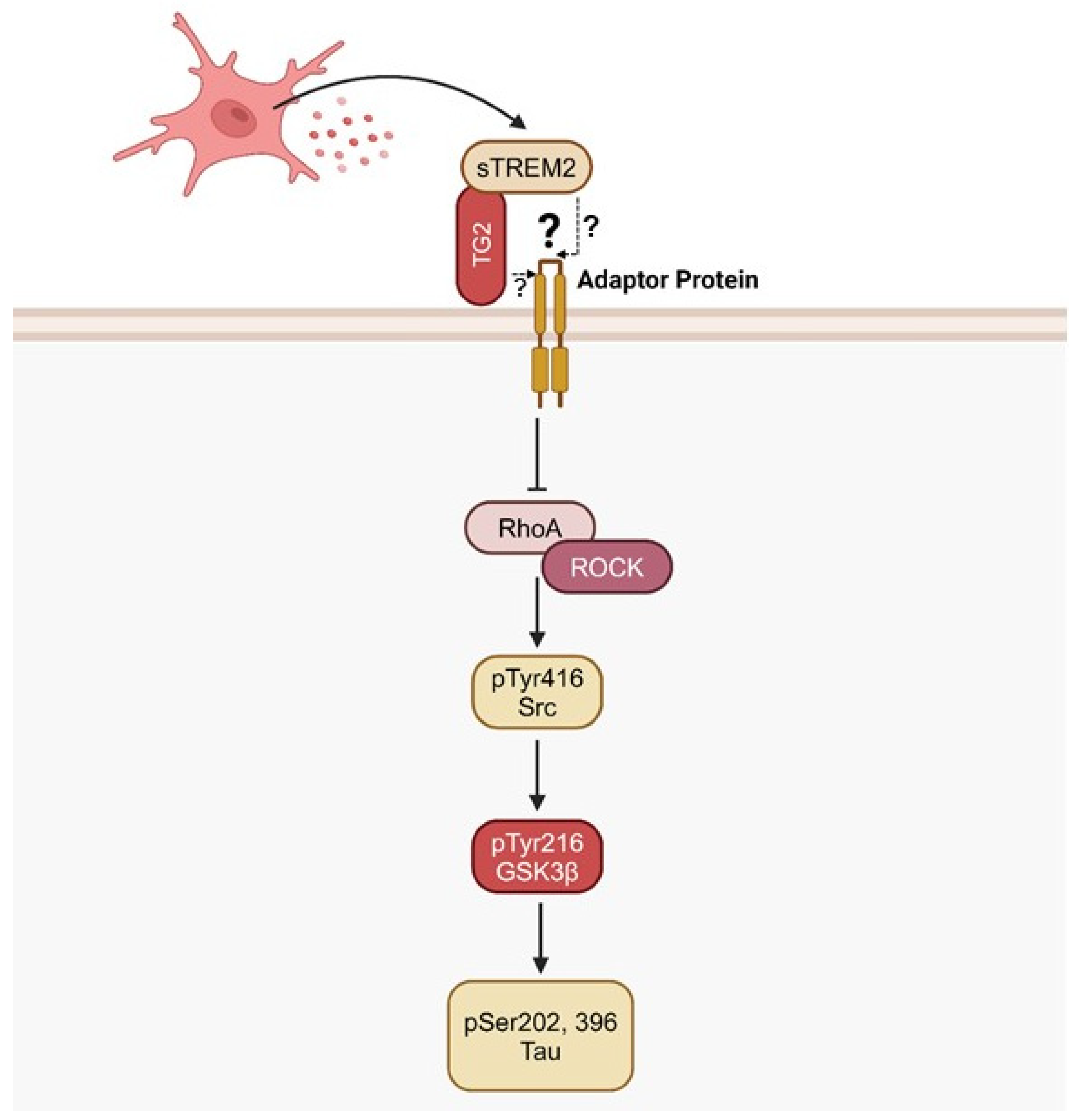

sTREM2 as a Regulator of RhoA/ROCK/GSK3β Signaling

Emerging Perspectives and Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ittner, L.M.; Ke, Y.D.; Delerue, F.; et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell 2010, 142, 387–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, D.; Perestelo-Perez, L.; Westman, E.; et al. Meta-Review of CSF Core Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease: The State-of-the-Art after the New Revised Diagnostic Criteria. Front Aging Neurosci 2014, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.F. Thirty Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease Unified by a Common Neuroimmune-Neuroinflammation Mechanism. Brain Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creekmore, B.C.; Watanabe, R.; Lee, E.B. Neurodegenerative Disease Tauopathies. Annu Rev Pathol 2024, 19, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindarajulu, M.; Ramesh, S.; Beasley, M.; et al. Role of cGAS-Sting Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Zheng, T.; Li, W.; et al. IL-33/ST2 signaling pathway and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2023, 230, 107773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, K. C/EBPbeta/AEP Signaling Drives Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. Neurosci Bull 2023, 39, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sai Varshini, M.; Aishwarya Reddy, R.; Thaggikuppe Krishnamurthy, P. Unlocking hope: GSK-3 inhibitors and Wnt pathway activation in Alzheimer’s therapy. J Drug Target 2024, 32, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; et al. Role of RhoA/ROCK signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res 2021, 414, 113481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, L.; Yang, J.; et al. Soluble TREM2 ameliorates tau phosphorylation and cognitive deficits through activating transgelin-2 in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckenstaler, R.; Hauke, M.; Benndorf, R.A. A current overview of RhoA, RhoB, and RhoC functions in vascular biology and pathology. Biochem Pharmacol 2022, 206, 115321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, K.; Chen, M. Dynamic functions of RhoA in tumor cell migration and invasion. Small GTPases 2013, 4, 141–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y. Cell type-specific signaling function of RhoA GTPase: lessons from mouse gene targeting. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 36179–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, M.; Rusk, N. Control of vesicular trafficking by Rho GTPases. Curr Biol 2003, 13, R409–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loirand, G.; Guerin, P.; Pacaud, P. Rho kinases in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology. Circ Res 2006, 98, 322–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. Rho GTPases in neuronal morphogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2000, 1, 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Helden, S.F.; Anthony, E.C.; Dee, R.; et al. Rho GTPase expression in human myeloid cells. e: PLoS One 7, 4256; e3. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.I.; Blaabjerg, M.; Freude, K.; et al. RhoA Signaling in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolias, K.F.; Duman, J.G.; Um, K. Control of synapse development and plasticity by Rho GTPase regulatory proteins. Prog Neurobiol 2011, 94, 133–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankiewicz, T.R.; Linseman, D.A. Rho family GTPases: key players in neuronal development, neuronal survival, and neurodegeneration. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulherkar, S.; Tolias, K.F. RhoA-ROCK Signaling as a Therapeutic Target in Traumatic Brain Injury. 2020; 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, A.E.; Takizawa, B.T.; Strittmatter, S.M. Rho kinase inhibition enhances axonal regeneration in the injured CNS. J Neurosci 2003, 23, 1416–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Xu, X.M. RhoA/Rho kinase in spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res 2016, 11, 23–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, A.; Reinhard, N.R.; Hordijk, P.L. Toward understanding RhoGTPase specificity: structure, function and local activation. Small GTPases 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherfils, J.; Zeghouf, M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev 2013, 93, 269–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, J.L.; Rehmann, H.; Wittinghofer, A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell 2007, 129, 865–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, R.G.; Ridley, A.J. Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mata, R.; Boulter, E.; Burridge, K. The ’invisible hand’: regulation of RHO GTPases by RHOGDIs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011, 12, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DerMardirossian, C.; Bokoch, G.M. GDIs: central regulatory molecules in Rho GTPase activation. Trends Cell Biol 2005, 15, 356–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, K.; Melendez, J.; Baumann, J.M.; et al. Loss of RhoA in neural progenitor cells causes the disruption of adherens junctions and hyperproliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 7607–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, T.; Kikuchi, A.; Ohga, N.; et al. Purification and characterization from bovine brain cytosol of a novel regulatory protein inhibiting the dissociation of GDP from and the subsequent binding of GTP to rhoB p20, a ras p21-like GTP-binding protein. J Biol Chem 1990, 265, 9373–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, M.J.; Maru, Y.; Leonard, D.; et al. A GDP dissociation inhibitor that serves as a GTPase inhibitor for the Ras-like protein CDC42Hs. Science 1992, 258, 812–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulter, E.; Garcia-Mata, R.; Guilluy, C.; et al. Regulation of Rho GTPase crosstalk, degradation and activity by RhoGDI1. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12, 477–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.D.; Kiosses, W.B.; Schwartz, M.A. Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J 1999, 18, 578–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, S.; Aivazian, D. Targeting Rab GTPases to distinct membrane compartments. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004, 5, 886–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solski, P.A.; Helms, W.; Keely, P.J.; et al. RhoA biological activity is dependent on prenylation but independent of specific isoprenoid modification. Cell Growth Differ 2002, 13, 363–73. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.J.; Mitin, N.; Keller, P.J.; et al. Rho Family GTPase modification and dependence on CAAX motif-signaled posttranslational modification. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 25150–25163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.; Gesbert, F.; Delespine-Carmagnat, M.; et al. Protein kinase A phosphorylation of RhoA mediates the morphological and functional effects of cyclic AMP in cytotoxic lymphocytes. EMBO J 1996, 15, 510–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbroek, S.M.; Wennerberg, K.; Burridge, K. Serine phosphorylation negatively regulates RhoA in vivo. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 19023–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauzeau, V.; Le Jeune, H.; Cario-Toumaniantz, C.; et al. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway inhibits RhoA-induced Ca2+ sensitization of contraction in vascular smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 21722–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Huang, F.; Lum, H. PKA inhibits RhoA activation: a protection mechanism against endothelial barrier dysfunction. L: Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284, 2003; -80. [Google Scholar]

- Nusser, N.; Gosmanova, E.; Makarova, N.; et al. Serine phosphorylation differentially affects RhoA binding to effectors: implications to NGF-induced neurite outgrowth. Cell Signal 2006, 18, 704–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riento, K.; Ridley, A.J. Rocks: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003, 4, 446–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, O.; Fujisawa, K.; Ishizaki, T.; et al. ROCK-I and ROCK-II, two isoforms of Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein serine/threonine kinase in mice. FEBS Lett 1996, 392, 189–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaki, T.; Maekawa, M.; Fujisawa, K.; et al. The small GTP-binding protein Rho binds to and activates a 160 kDa Ser/Thr protein kinase homologous to myotonic dystrophy kinase. EMBO J 1996, 15, 1885–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorsky, R.; Blumenstein, L.; Vetter, I.R.; et al. Structural insights into the interaction of ROCKI with the switch regions of RhoA. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 7098–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Liu, W.; Yan, J.; et al. Structure basis and unconventional lipid membrane binding properties of the PH-C1 tandem of rho kinases. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 26263–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, K.; Fujita, A.; Ishizaki, T.; et al. Identification of the Rho-binding domain of p160ROCK, a Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 23022–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.C.; Tatenhorst, L.; Roser, A.E.; et al. ROCK inhibition in models of neurodegeneration and its potential for clinical translation. Pharmacol Ther 2018, 189, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.K.; Seto, M.; Noma, K. Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2007, 50, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ito, M.; Ichikawa, K.; et al. Inhibitory phosphorylation site for Rho-associated kinase on smooth muscle myosin phosphatase. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 37385–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapet, C.; Simoncini, S.; Loriod, B.; et al. Thrombin-induced endothelial microparticle generation: identification of a novel pathway involving ROCK-II activation by caspase-2. Blood 2006, 108, 1868–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmandke, A.; Schmandke, A.; Strittmatter, S.M. ROCK and Rho: biochemistry and neuronal functions of Rho-associated protein kinases. Neuroscientist 2007, 13, 454–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Yamashita, T. Axon growth inhibition by RhoA/ROCK in the central nervous system. Front Neurosci 2014, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.C.; Koleske, A.J. Mechanisms of synapse and dendrite maintenance and their disruption in psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci 2010, 33, 349–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newell-Litwa, K.A.; Badoual, M.; Asmussen, H.; et al. ROCK1 and 2 differentially regulate actomyosin organization to drive cell and synaptic polarity. J Cell Biol 2015, 210, 225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, X.; Surma, M.; et al. Distinct roles for ROCK1 and ROCK2 in the regulation of cell detachment. Cell Death Dis, 2013; 4, e483. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, D.A.; Alessi, D.R.; Cohen, P.; et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 1995, 378, 785–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamano, T.; Shirafuji, N.; Yen, S.H.; et al. Rho-kinase ROCK inhibitors reduce oligomeric tau protein. Neurobiol Aging 2020, 89, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, N.; Tamarozzi, E.R.; Lima, J.; et al. Novel Dual AChE and ROCK2 Inhibitor Induces Neurogenesis via PTEN/AKT Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease Model. 2022; 23. [Google Scholar]

- Hanger, D.P.; Hughes, K.; Woodgett, J.R.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 induces Alzheimer’s disease-like phosphorylation of tau: generation of paired helical filament epitopes and neuronal localisation of the kinase. Neurosci Lett 1992, 147, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgett, J.R. Molecular cloning and expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3/factor A. EMBO J 1990, 9, 2431–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doble, B.W.; Woodgett, J.R. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci 2003, 116, 1175–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, C.A.; Jope, R.S. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol 2001, 65, 391–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draffin, J.E.; Sanchez-Castillo, C.; Fernandez-Rodrigo, A.; et al. GSK3alpha, not GSK3beta, drives hippocampal NMDAR-dependent LTD via tau-mediated spine anchoring. e: EMBO J 40, 1055; e13. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Mattar, P.; Zinyk, D.; et al. GSK3 temporally regulates neurogenin 2 proneural activity in the neocortex. J Neurosci 2012, 32, 7791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.X.; Wang, X.L.; Chen, J.Q.; et al. Differential Roles of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Subtypes Alpha and Beta in Cortical Development. Front Mol Neurosci 2017, 10, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeki, K.; Machida, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta2 has lower phosphorylation activity to tau than glycogen synthase kinase-3beta1. Biol Pharm Bull 2011, 34, 146–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuskaitis, C.J.; Jope, R.S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates microglial migration, inflammation, and inflammation-induced neurotoxicity. Cell Signal 2009, 21, 264–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurel, E.; Jope, R.S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates inflammatory tolerance in astrocytes. Neuroscience 2010, 169, 1063–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Shao, C.Y.; Xu, S.M.; et al. GSK3beta promotes the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells via beta-catenin-mediated transcriptional regulation. Mol Neurobiol 2014, 50, 507–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K.; Nikolakaki, E.; Plyte, S.E.; et al. Modulation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 family by tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J 1993, 12, 803–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, D.A.; Alessi, D.R.; Vandenheede, J.R.; et al. The inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin or insulin-like growth factor 1 in the rat skeletal muscle cell line L6 is blocked by wortmannin, but not by rapamycin: evidence that wortmannin blocks activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in L6 cells between Ras and Raf. 2: Biochem J 303 ( Pt 1), 1994; -6. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Yu, S.X.; Lu, Y.; et al. Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 11960–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.F.; van den Bosch, M.T.; Hunter, R.W.; et al. Dual regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3)alpha/beta by protein kinase C (PKC)alpha and Akt promotes thrombin-mediated integrin alphaIIbbeta3 activation and granule secretion in platelets. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 3918–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.; Frame, S.; Cohen, P. Further evidence that the tyrosine phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) in mammalian cells is an autophosphorylation event. Biochem J 2004, 377, 249–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goc, A.; Al-Husein, B.; Katsanevas, K.; et al. Targeting Src-mediated Tyr216 phosphorylation and activation of GSK-3 in prostate cancer cells inhibit prostate cancer progression in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 775–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Xu, C.; Gong, Y.; et al. RhoA/Rock activation represents a new mechanism for inactivating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the aging-associated bone loss. Cell Regen 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Tan, J.; Xie, S.; et al. GSK-3beta is Dephosphorylated by PP2A in a Leu309 Methylation-Independent Manner. J Alzheimers Dis 2016, 49, 365–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Sotnikova, T.D.; Yao, W.D.; et al. Lithium antagonizes dopamine-dependent behaviors mediated by an AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 signaling cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 5099–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, J.L.; Unterwald, E.M. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling in cellular and behavioral responses to psychostimulant drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2020, 1867, 118746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.R.; Hattori, H.; Hossain, M.A.; et al. Akt as a mediator of cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 11712–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sarno, P.; Bijur, G.N.; Zmijewska, A.A.; et al. In vivo regulation of GSK3 phosphorylation by cholinergic and NMDA receptors. Neurobiol Aging 2006, 27, 413–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svenningsson, P.; Tzavara, E.T.; Carruthers, R.; et al. Diverse psychotomimetics act through a common signaling pathway. Science 2003, 302, 1412–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szatmari, E.; Habas, A.; Yang, P.; et al. A positive feedback loop between glycogen synthase kinase 3beta and protein phosphatase 1 after stimulation of NR2B NMDA receptors in forebrain neurons. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 37526–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, P.; et al. beta-amyloid impairs the regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35, 449–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.; Beaulieu, J.M. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by lithium, a mechanism in search of specificity. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 1028963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryves, W.J.; Harwood, A.J. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 by competition for magnesium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 280, 720–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenboim, N.; Plotkin, B.; Shlomo, S.B.; et al. Lithium-mediated phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta involves PI3 kinase-dependent activation of protein kinase C-alpha. J Mol Neurosci 2004, 24, 237–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.; Sabio, G.; Risco, A.M.; et al. Lithium blocks the PKB and GSK3 dephosphorylation induced by ceramide through protein phosphatase-2A. Cell Signal 2002, 14, 557–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, A.; Sabio, G.; Gonzalez-Polo, R.A.; et al. Lithium inhibits caspase 3 activation and dephosphorylation of PKB and GSK3 induced by K+ deprivation in cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem 2001, 78, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, R.; Hough, C.; Nakazawa, T.; et al. Lithium protection against glutamate excitotoxicity in rat cerebral cortical neurons: involvement of NMDA receptor inhibition possibly by decreasing NR2B tyrosine phosphorylation. J Neurochem 2002, 80, 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonaka, S.; Hough, C.J.; Chuang, D.M. Chronic lithium treatment robustly protects neurons in the central nervous system against excitotoxicity by inhibiting N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 2642–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, T.; Gotoh, H.; Kiyonari, H.; et al. Cell Type-Specific Transcriptional Control of Gsk3beta in the Developing Mammalian Neocortex. Front Neurosci 2022, 16, 811689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Wang, G.L.; Shi, X.; et al. The age-associated decline of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta plays a critical role in the inhibition of liver regeneration. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 3867–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rylatt, D.B.; Aitken, A.; Bilham, T.; et al. Glycogen synthase from rabbit skeletal muscle. Amino acid sequence at the sites phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase-3, and extension of the N-terminal sequence containing the site phosphorylated by phosphorylase kinase. Eur J Biochem 1980, 107, 529–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeflich, K.P.; Luo, J.; Rubie, E.A.; et al. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature 2000, 406, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, S.; Cohen, P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem J 2001, 359, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jope, R.S.; Johnson, G.V. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem Sci 2004, 29, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; et al. GSK-3 is a master regulator of neural progenitor homeostasis. Nat Neurosci 2009, 12, 1390–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Guo, W.; Liang, X.; et al. Both the establishment and the maintenance of neuronal polarity require active mechanisms: critical roles of GSK-3beta and its upstream regulators. Cell 2005, 120, 123–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.; Jang, J.; Choi, J.; et al. GSK3beta, but not GSK3alpha, inhibits the neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells as a downstream target of mammalian target of rapamycin complex1. Stem Cells Dev 2014, 23, 1121–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, T.; Hevner, R.F. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in development of the cerebral cortex. Dev Growth Differ 2009, 51, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machold, R.; Hayashi, S.; Rutlin, M.; et al. Sonic hedgehog is required for progenitor cell maintenance in telencephalic stem cell niches. Neuron 2003, 39, 937–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, K.; Gaiano, N. Notch signaling in the mammalian central nervous system: insights from mouse mutants. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8, 709–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, J.; et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.; et al. Direct inhibition of GSK3beta by the phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of LRP6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. e: PLoS One 3, 4046. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Huang, H.; Garcia Abreu, J.; et al. Inhibition of GSK3 phosphorylation of beta-catenin via phosphorylated PPPSPXS motifs of Wnt coreceptor LRP6. e: PLoS One 4, 4926. [Google Scholar]

- Aberle, H.; Bauer, A.; Stappert, J.; et al. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J 1997, 16, 3797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Cullen, J.P.; Morrow, D.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta positively regulates Notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells: role in cell proliferation and survival. Basic Res Cardiol 2011, 106, 773–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, L.; Ingles-Esteve, J.; Aguilera, C.; et al. Phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta down-regulates Notch activity, a link for Notch and Wnt pathways. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 32227–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Conner, S.D. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibition enhances Notch1 recycling. Mol Biol Cell 2018, 29, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempe, D.; Casas, M.; Karaz, S.; et al. Multisite protein kinase A and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylation leads to Gli3 ubiquitination by SCFbetaTrCP. Mol Cell Biol 2006, 26, 4316–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, J.K.; Bates, R.D.P.; Rapp, C.D.; et al. GSK-3 modulates SHH-driven proliferation in postnatal cerebellar neurogenesis and medulloblastoma. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dill, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, F.; et al. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 promotes axonal growth and recovery in the CNS. J Neurosci 2008, 28, 8914–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.H.; Cheng, T.; Jan, L.Y.; et al. APC and GSK-3beta are involved in mPar3 targeting to the nascent axon and establishment of neuronal polarity. Curr Biol 2004, 14, 2025–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, T.; Kawano, Y.; Arimura, N.; et al. GSK-3beta regulates phosphorylation of CRMP-2 and neuronal polarity. Cell 2005, 120, 137–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hapak, S.M.; Rothlin, C.V.; Ghosh, S. PAR3-PAR6-atypical PKC polarity complex proteins in neuronal polarization. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018, 75, 2735–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Dong, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Regulation of PTEN by Rho small GTPases. Nat Cell Biol 2005, 7, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meili, R.; Sasaki, A.T.; Firtel, R.A. Rho Rocks PTEN. Nat Cell Biol 2005, 7, 334–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalhoub, N.; Baker, S.J. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol 2009, 4, 127–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoeli-Lerner, M.; Chin, Y.R.; Hansen, C.K.; et al. Akt/protein kinase b and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta signaling pathway regulates cell migration through the NFAT1 transcription factor. Mol Cancer Res 2009, 7, 425–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, X.F.; Viswambharan, H.; Barandier, C.; et al. Rho GTPase/Rho kinase negatively regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation through the inhibition of protein kinase B/Akt in human endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 8467–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauretti, E.; Dincer, O.; Pratico, D. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2020, 1867, 118664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, C.; Killick, R.; Lovestone, S. The GSK3 hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 2008, 104, 1433–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toral-Rios, D.; Pichardo-Rojas, P.S.; Alonso-Vanegas, M.; et al. GSK3beta and Tau Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease and Epilepsy. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukrasch, M.D.; Biernat, J.; von Bergen, M.; et al. Sites of tau important for aggregation populate beta-structure and bind to microtubules and polyanions. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 24978–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukrasch, M.D.; Bibow, S.; Korukottu, J.; et al. Structural polymorphism of 441-residue tau at single residue resolution. e: PLoS Biol 7, 2009; e34. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten, M.D.; Lockwood, A.H.; Hwo, S.Y.; et al. A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975, 72, 1858–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drubin, D.G.; Kirschner, M.W. Tau protein function in living cells. J Cell Biol 1986, 103, 2739–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarella, R.A.; Skiniotis, G.; Goldie, K.N.; et al. Surface-decoration of microtubules by human tau. J Mol Biol 2004, 339, 539–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, W.; Hanger, D.P.; Miller, C.C.; et al. The importance of tau phosphorylation for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurol 2013, 4, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkinderen, P.; Scales, T.M.; Hanger, D.P.; et al. Tyrosine 394 is phosphorylated in Alzheimer’s paired helical filament tau and in fetal tau with c-Abl as the candidate tyrosine kinase. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 6584–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neddens, J.; Temmel, M.; Flunkert, S.; et al. Phosphorylation of different tau sites during progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2018, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintanilla, R.A.; von Bernhardi, R.; Godoy, J.A.; et al. Phosphorylated tau potentiates Abeta-induced mitochondrial damage in mature neurons. Neurobiol Dis 2014, 71, 260–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielska, A.A.; Zondlo, N.J. Hyperphosphorylation of tau induces local polyproline II helix. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 5527–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantrelle, F.X.; Loyens, A.; Trivelli, X.; et al. Phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation of the PHF-1 Epitope of Tau Protein Induce Local Conformational Changes of the C-Terminus and Modulate Tau Self-Assembly Into Fibrillar Aggregates. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14, 661368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindwall, G.; Cole, R.D. Phosphorylation affects the ability of tau protein to promote microtubule assembly. J Biol Chem 1984, 259, 5301–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Dexheimer, T.; Sui, D.; et al. Hyperphosphorylated tau aggregation and cytotoxicity modulators screen identified prescription drugs linked to Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive functions. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.C.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K. Alzheimer’s disease hyperphosphorylated tau sequesters normal tau into tangles of filaments and disassembles microtubules. Nat Med 1996, 2, 783–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Kwon, Y.T.; Li, M.; et al. Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature 2000, 405, 360–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, H.C.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Y.; et al. A survey of Cdk5 activator p35 and p25 levels in Alzheimer’s disease brains. FEBS Lett 2002, 523, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Su, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Regulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) phosphorylation and processing by p35/Cdk5 and p25/Cdk5. FEBS Lett 2003, 547, 193–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.L.; Kesavapany, S.; Gravell, M.; et al. A Cdk5 inhibitory peptide reduces tau hyperphosphorylation and apoptosis in neurons. EMBO J 2005, 24, 209–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seger, R.; Krebs, E.G. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J 1995, 9, 726–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Lee, H.G.; Raina, A.K.; et al. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosignals 2002, 11, 270–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, M.G. The role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in memory encoding. Rev Neurosci 2006, 17, 619–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sclip, A.; Tozzi, A.; Abaza, A.; et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase has a key role in Alzheimer disease synaptic dysfunction in vivo. e: Cell Death Dis 5, 1019. [Google Scholar]

- Gourmaud, S.; Paquet, C.; Dumurgier, J.; et al. Increased levels of cerebrospinal fluid JNK3 associated with amyloid pathology: links to cognitive decline. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015, 40, 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, R.J., 3rd; Govindarajan, A.; Tonegawa, S. Translational regulatory mechanisms in persistent forms of synaptic plasticity. Neuron 2004, 44, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.J.; Braak, H.; An, W.L.; et al. Up-regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases ERK1/2 and MEK1/2 is associated with the progression of neurofibrillary degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2002, 109, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I.; Blanco, R.; Carmona, M.; et al. Phosphorylated map kinase (ERK1, ERK2) expression is associated with early tau deposition in neurones and glial cells, but not with increased nuclear DNA vulnerability and cell death, in Alzheimer disease, Pick’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Brain Pathol 2001, 11, 144–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giraldo, E.; Lloret, A.; Fuchsberger, T.; et al. Abeta and tau toxicities in Alzheimer’s are linked via oxidative stress-induced p38 activation: protective role of vitamin E. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 873–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.L.; Li, Q.X.; Ciccotosto, G.D.; et al. Mild oxidative stress induces redistribution of BACE1 in non-apoptotic conditions and promotes the amyloidogenic processing of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid precursor protein. e: PLoS One 8, 6124; e6. [Google Scholar]

- Igaz, L.M.; Winograd, M.; Cammarota, M.; et al. Early activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway in the hippocampus is required for short-term memory formation of a fear-motivated learning. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2006, 26, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, L.; Ammit, A.J. Targeting p38 MAPK pathway for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2010, 58, 561–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenki, P.; Khodagholi, F.; Shaerzadeh, F. Inhibition of phosphorylation of JNK suppresses Abeta-induced ER stress and upregulates prosurvival mitochondrial proteins in rat hippocampus. J Mol Neurosci 2013, 49, 262–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz-Montano, J.R.; Moreno, F.J.; Avila, J.; et al. Lithium inhibits Alzheimer’s disease-like tau protein phosphorylation in neurons. FEBS Lett 1997, 411, 183–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Chen, D.C.; Klein, P.S.; et al. Lithium reduces tau phosphorylation by inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 25326–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentini, A.; Rosi, M.C.; Grossi, C.; et al. Lithium improves hippocampal neurogenesis, neuropathology and cognitive functions in APP mutant mice. e: PLoS One 5, 1438; e2. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, P.T.; Wu, Y.; Zou, H.; et al. Inhibition of GSK3beta-mediated BACE1 expression reduces Alzheimer-associated phenotypes. J Clin Invest 2013, 123, 224–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.J.; Hernandez, F.; Gomez-Ramos, P.; et al. Decreased nuclear beta-catenin, tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration in GSK-3beta conditional transgenic mice. EMBO J 2001, 20, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez de Barreda, E.; Perez, M.; Gomez Ramos, P.; et al. Tau-knockout mice show reduced GSK3-induced hippocampal degeneration and learning deficits. Neurobiol Dis 2010, 37, 622–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, K.; Yilmaz, Z.; Brion, J.P. Increased level of active GSK-3beta in Alzheimer’s disease and accumulation in argyrophilic grains and in neurones at different stages of neurofibrillary degeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2007, 33, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, F.; Gomez de Barreda, E.; Fuster-Matanzo, A.; et al. GSK3: a possible link between beta amyloid peptide and tau protein. Exp Neurol 2010, 223, 322–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cap, K.C.; Jung, Y.J.; Choi, B.Y.; et al. Distinct dual roles of p-Tyr42 RhoA GTPase in tau phosphorylation and ATP citrate lyase activation upon different Abeta concentrations. Redox Biol 2020, 32, 101446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnaik, A.; Zagrebelsky, M.; Korte, M.; et al. Signaling via the p75 neurotrophin receptor facilitates amyloid-beta-induced dendritic spine pathology. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, B. Roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3 in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012, 9, 864–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, K.; Kuzuya, A.; Shimozono, Y.; et al. GSK3beta activity modifies the localization and function of presenilin 1. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 15823–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.F.; Xu, T.H.; Yan, Y.; et al. Amyloid beta: structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2017, 38, 1205–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, V.J.R.; Guimaraes, F.M.; Diniz, B.S.; et al. Neurobiological pathways to Alzheimer’s disease: Amyloid-beta, TAU protein or both? Dement Neuropsychol 2009, 3, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Xia, W.; et al. Targeting Amyloidogenic Processing of APP in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Mol Neurosci 2020, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twomey, C.; McCarthy, J.V. Presenilin-1 is an unprimed glycogen synthase kinase-3beta substrate. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 4015–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofola, O.; Kerr, F.; Rogers, I.; et al. Inhibition of GSK-3 ameliorates Abeta pathology in an adult-onset Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. e: PLoS Genet 6, 1001. [Google Scholar]

- Magdesian, M.H.; Carvalho, M.M.; Mendes, F.A.; et al. Amyloid-beta binds to the extracellular cysteine-rich domain of Frizzled and inhibits Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 9359–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berth, S.H.; Lloyd, T.E. Disruption of axonal transport in neurodegeneration. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- LaPointe, N.E.; Morfini, G.; Pigino, G.; et al. The amino terminus of tau inhibits kinesin-dependent axonal transport: implications for filament toxicity. J Neurosci Res 2009, 87, 440–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittner, L.M.; Ke, Y.D. ; Gotz J: Phosphorylated Tau interacts with c-Jun N-terminal kinase-interacting protein 1 (JIP1) in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 20909–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuchillo-Ibanez, I.; Seereeram, A.; Byers, H.L.; et al. Phosphorylation of tau regulates its axonal transport by controlling its binding to kinesin. FASEB J 2008, 22, 3186–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soutar, M.P.; Kim, W.Y.; Williamson, R.; et al. Evidence that glycogen synthase kinase-3 isoforms have distinct substrate preference in the brain. J Neurochem 2010, 115, 974–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chu, C.B.; Li, J.F.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 reduces acetylcholine level in striatum via disturbing cellular distribution of choline acetyltransferase in cholinergic interneurons in rats. Neuroscience 2013, 255, 203–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, L.; Duan, L.; Xu, W.; et al. Nerve growth factor metabolic dysfunction contributes to sevoflurane-induced cholinergic degeneration and cognitive impairments. Brain Res 2019, 1707, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Liu, E.J.; et al. Activation of GSK-3 disrupts cholinergic homoeostasis in nucleus basalis of Meynert and frontal cortex of rats. J Cell Mol Med 2017, 21, 3515–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.Q.; Liu, D.; Hu, J.; et al. GSK-3 beta inhibits presynaptic vesicle exocytosis by phosphorylating P/Q-type calcium channel and interrupting SNARE complex formation. J Neurosci 2010, 30, 3624–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.Q.; Wang, S.H.; Liu, D.; et al. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibits long-term potentiation with synapse-associated impairments. J Neurosci 2007, 27, 12211–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, D.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 as a key regulator of cognitive function. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2020, 52, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Taliyan, R. Neuroprotective role of Indirubin-3′-monoxime, a GSKbeta inhibitor in high fat diet induced cognitive impairment in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 452, 1009–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peineau, S.; Bradley, C.; Taghibiglou, C.; et al. The role of GSK-3 in synaptic plasticity. S: Br J Pharmacol 153 Suppl 1, 2008; -37. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, C.; Markevich, V.; Plattner, F.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition is integral to long-term potentiation. Eur J Neurosci 2007, 25, 81–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peineau, S.; Taghibiglou, C.; Bradley, C.; et al. LTP inhibits LTD in the hippocampus via regulation of GSK3beta. Neuron 2007, 53, 703–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.H.; Schoenfeld, B.P.; Bell, A.J.; et al. Pharmacological reversal of synaptic plasticity deficits in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome by group II mGluR antagonist or lithium treatment. Brain Res 2011, 1380, 106–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, A.V.; King, M.K.; Palomo, V.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors reverse deficits in long-term potentiation and cognition in fragile X mice. Biol Psychiatry 2014, 75, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Hoeffer, C.A.; Capetillo-Zarate, E.; et al. Dysregulation of the mTOR pathway mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One, 2010; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.H.; Lv, B.L.; Xie, J.Z.; et al. AGEs induce Alzheimer-like tau pathology and memory deficit via RAGE-mediated GSK-3 activation. Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33, 1400–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contestabile, A.; Greco, B.; Ghezzi, D.; et al. Lithium rescues synaptic plasticity and memory in Down syndrome mice. J Clin Invest 2013, 123, 348–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewers, M.; Biechele, G.; Suarez-Calvet, M.; et al. Higher CSF sTREM2 and microglia activation are associated with slower rates of beta-amyloid accumulation. e: EMBO Mol Med 12, 1230; e8. [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeier, N.; Suarez-Calvet, M.; Frontzkowski, L.; et al. Higher CSF sTREM2 attenuates ApoE4-related risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener 2020, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, D.; Suarez-Calvet, M.; Hager, P.; et al. sTREM2 is associated with amyloid-related p-tau increases and glucose hypermetabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. e: EMBO Mol Med 15, 1698; e7. [Google Scholar]

- Ewers, M.; Franzmeier, N.; Suarez-Calvet, M.; et al. Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med, 2019; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchon, A.; Dietrich, J.; Colonna, M. Cutting edge: inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes. J Immunol 2000, 164, 4991–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipello, F.; Morini, R.; Corradini, I.; et al. The Microglial Innate Immune Receptor TREM2 Is Required for Synapse Elimination and Normal Brain Connectivity. 9: Immunity 48, 2018; e8. [Google Scholar]

- Dardiotis, E.; Siokas, V.; Pantazi, E.; et al. A novel mutation in TREM2 gene causing Nasu-Hakola disease and review of the literature. 1: Neurobiol Aging 53, 2017; e22. [Google Scholar]

- Daws, M.R.; Sullam, P.M.; Niemi, E.C.; et al. Pattern recognition by TREM-2: binding of anionic ligands. J Immunol 2003, 171, 594–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Rochford, C.D.; Neumann, H. Clearance of apoptotic neurons without inflammation by microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2. J Exp Med 2005, 201, 647–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Prinz, M.; Stagi, M.; et al. TREM2-transduced myeloid precursors mediate nervous tissue debris clearance and facilitate recovery in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. e: PLoS Med 4, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hamerman, J.A.; Jarjoura, J.R.; Humphrey, M.B.; et al. Cutting edge: inhibition of TLR and FcR responses in macrophages by triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM)-2 and DAP12. J Immunol 2006, 177, 2051–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winfree, R.L.; Seto, M.; Dumitrescu, L.; et al. TREM2 gene expression associations with Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology are region-specific: implications for cortical versus subcortical microglia. Acta Neuropathol 2023, 145, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennerfelt, H.; Frost, E.L.; Shapiro, D.A.; et al. SYK coordinates neuroprotective microglial responses in neurodegenerative disease. Cell 185:4135‐4152 e22, 2022.

- Wang, S.; Sudan, R.; Peng, V.; et al. TREM2 drives microglia response to amyloid‐beta via SYK‐dependent and ‐independent pathways. Cell 185:4153‐4169 e19, 2022.

- Wang, S.; Mustafa, M.; Yuede, C.M.; et al. Anti‐human TREM2 induces microglia proliferation and reduces pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease model. J Exp Med 217, 2020.

- Mathys, H.; Adaikkan, C.; Gao, F.; et al. Temporal Tracking of Microglia Activation in Neurodegeneration at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, P.; Sevalle, J.; Deery, M.J.; et al. TREM2 shedding by cleavage at the H157-S158 bond is accelerated for the Alzheimer’s disease-associated H157Y variant. EMBO Mol Med 2017, 9, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbach, D.; Schindler, P.; Barske, C.; et al. ADAM17 is the main sheddase for the generation of human triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells (hTREM2) ectodomain and cleaves TREM2 after Histidine 157. Neurosci Lett 2017, 660, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raha, A.A.; Henderson, J.W.; Stott, S.R.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of TREM-2 in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Model. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 55, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilalta, A.; Zhou, Y.; Sevalle, J.; et al. Wild-type sTREM2 blocks Abeta aggregation and neurotoxicity, but the Alzheimer’s R47H mutant increases Abeta aggregation. J Biol Chem 2021, 296, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, D.L.; Stuchell-Brereton, M.D.; Kluender, C.E.; et al. Functional insights from biophysical study of TREM2 interactions with apoE and Abeta(1‐42). Alzheimers Dement, 2020.

- Lessard, C.B.; Malnik, S.L.; Zhou, Y.; et al. High‐affinity interactions and signal transduction between Abeta oligomers and TREM2. EMBO Mol Med 10, 2018.

- Zhong, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhuo, R.; et al. Soluble TREM2 ameliorates pathological phenotypes by modulating microglial functions in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccio, L.; Buonsanti, C.; Cella, M.; et al. Identification of soluble TREM-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and its association with multiple sclerosis and CNS inflammation. Brain 2008, 131, 3081–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoretti-Mercado, B.; Forsythe, S.M.; LeBeau, M.M.; et al. Expression and cytogenetic localization of the human SM22 gene (TAGLN). Genomics 1998, 49, 452–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapland, C.; Hsuan, J.J.; Totty, N.F.; et al. Purification and properties of transgelin: a transformation and shape change sensitive actin-gelling protein. J Cell Biol 1993, 121, 1065–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.M.; Xu, Y.D.; Peng, L.L.; et al. Transgelin‐2 as a therapeutic target for asthmatic pulmonary resistance. Sci Transl Med 10, 2018.

- Elsafadi, M.; Manikandan, M.; Dawud, R.A.; et al. Transgelin is a TGFbeta-inducible gene that regulates osteoblastic and adipogenic differentiation of human skeletal stem cells through actin cytoskeleston organization. e: Cell Death Dis 7, 2321. [Google Scholar]

- Na, B.R.; Kim, H.R.; Piragyte, I.; et al. TAGLN2 regulates T cell activation by stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton at the immunological synapse. J Cell Biol 2015, 209, 143–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, B.R.; Jun, C.D. TAGLN2-mediated actin stabilization at the immunological synapse: implication for cytotoxic T cell control of target cells. BMB Rep 2015, 48, 369–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, K.S.; et al. An Essential Role for TAGLN2 in Phagocytosis of Lipopolysaccharide-activated Macrophages. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 8731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, H.R.; Mun, Y.; et al. Transgelin-2 in immunity: Its implication in cell therapy. J Leukoc Biol 2018, 104, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.K.; Lu, J.; Wang, X.L.; et al. The Effects of a Transgelin-2 Agonist Administered at Different Times in a Mouse Model of Airway Hyperresponsiveness. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 873612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.R.; Park, J.S.; Park, J.H.; et al. Cell-permeable transgelin-2 as a potent therapeutic for dendritic cell-based cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.G.; Islam, R.; Cho, J.Y.; et al. Regulation of RhoA GTPase and various transcription factors in the RhoA pathway. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 6381–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forget, M.A.; Desrosiers, R.R.; Gingras, D.; et al. Phosphorylation states of Cdc42 and RhoA regulate their interactions with Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor and their extraction from biological membranes. Biochem J 2002, 361, 243–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Liang, Z.; Shi, J.; et al. PKA modulates GSK-3beta- and cdk5-catalyzed phosphorylation of tau in site- and kinase-specific manners. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 6269–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.M.; Ulloa, L.; Yang, Y.Q. Transgelin-2: Biochemical and Clinical Implications in Cancer and Asthma. Trends Biochem Sci 2019, 44, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gez, S.; Crossett, B.; Christopherson, R.I. Differentially expressed cytosolic proteins in human leukemia and lymphoma cell lines correlate with lineages and functions. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007, 1774, 1173–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Qiao, A.; Fan, G.H. Indirubin-3′-monoxime rescues spatial memory deficits and attenuates beta-amyloid-associated neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 2010, 39, 156–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, L.; Thunnissen, A.M.; White, A.W.; et al. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases, GSK-3beta and CK1 by hymenialdisine, a marine sponge constituent. Chem Biol 2000, 7, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, M.; Krause, W.; Fabian, H.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of iloprost in patients with chronic renal failure and on maintenance haemodialysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1990, 10, 285–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Begum, A.N.; Jones, M.R.; et al. GSK3 inhibitors show benefits in an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) model of neurodegeneration but adverse effects in control animals. Neurobiol Dis 2009, 33, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selenica, M.L.; Jensen, H.S.; Larsen, A.K.; et al. Efficacy of small-molecule glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors in the postnatal rat model of tau hyperphosphorylation. Br J Pharmacol 2007, 152, 959–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).