1. Introduction

Endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC) began in the 1990s, driven by the need for less invasive but equally effective therapeutic options. To ensure safe and effective treatment, a comprehensive guideline was developed based on clinical outcomes from surgical treatments. This guideline initially established the absolute indication for endoscopic treatment by analyzing factors such as tumor size, histologic differentiation, and ulcer presence, which are closely associated with the risk of lymph node metastasis [

1].

With advancements in endoscopic tools and techniques, as well as growing expertise among endoscopists, the treatment of larger and more complex lesions has become feasible. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), using specialized endoscopic knives, has replaced endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) as the preferred method for treating EGC, offering significantly higher complete resection rates. Despite these advancements, outcomes of endoscopic treatment for EGC remained suboptimal, especially for larger and more complex lesions. This led to the development of the expanded indication for endoscopic treatment, based again on the patients’ surgical outcomes [

2].

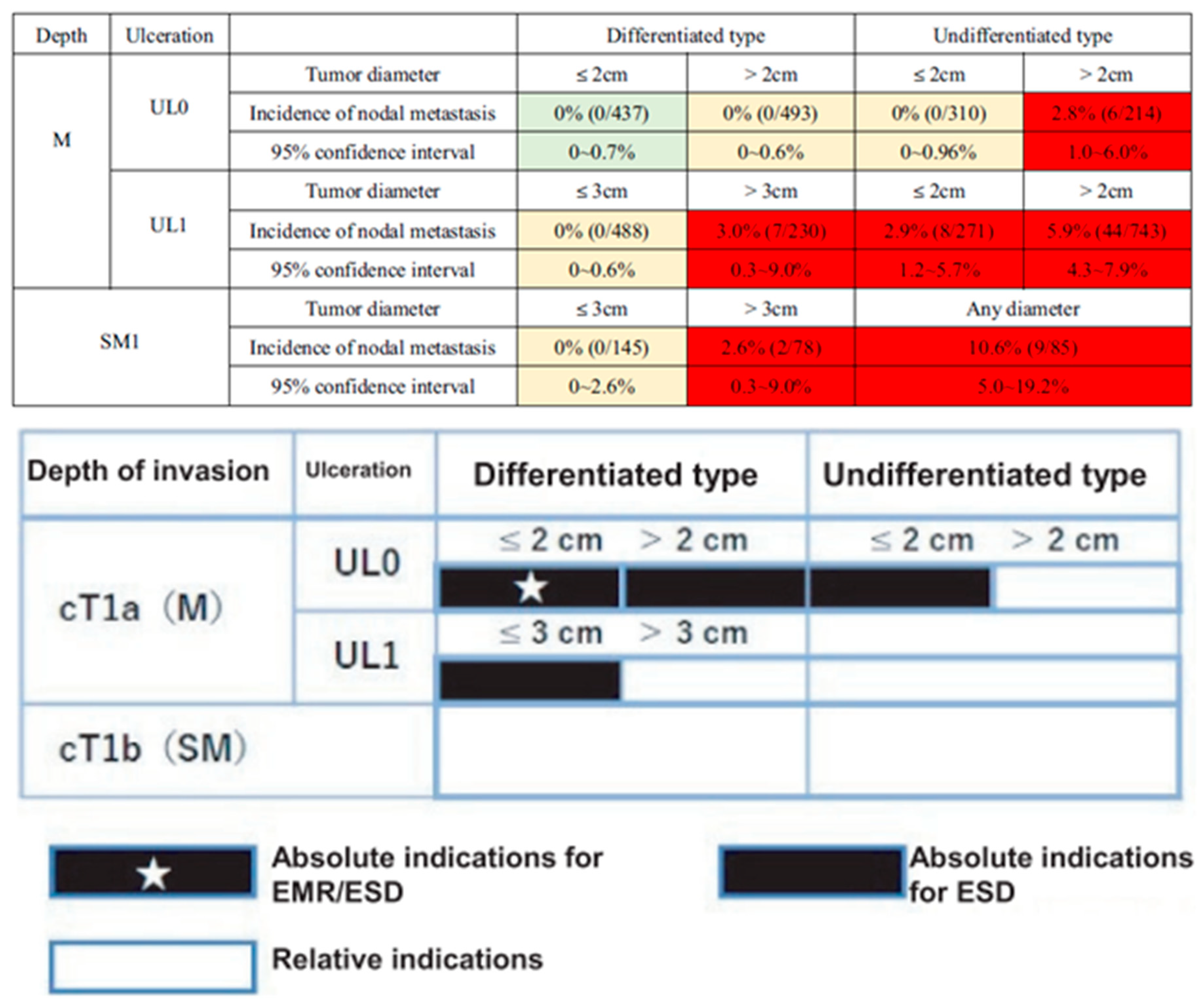

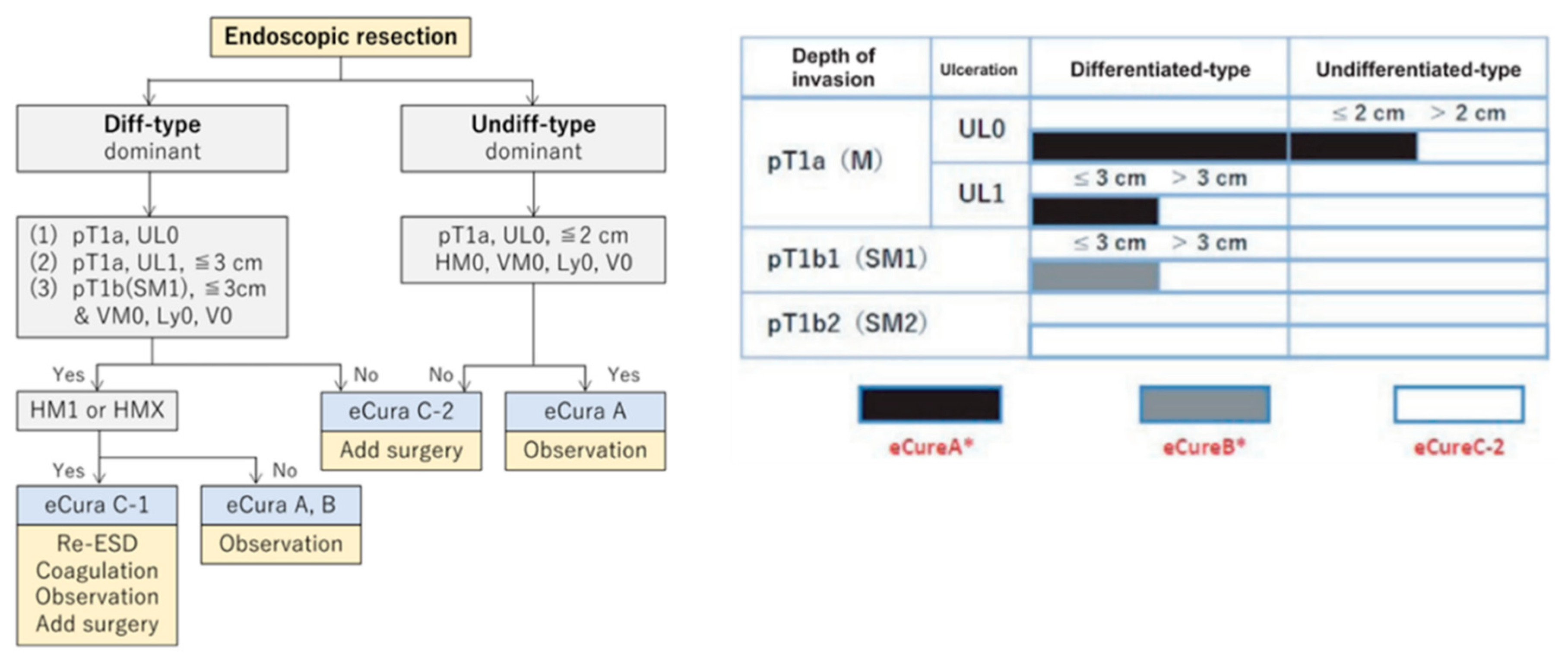

The categorization, as outlined in Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2010 (3

rd edition) and the Japanese Cancer Treatment Guideline (6th Edition), presents categories: absolute indication (absolute indication for EMR/ESD), expanded indication (absolute indication of ESD), and relative indication (

Figure 1). These categories are based on the possibility of lymph node metastasis observed in the surgical specimen [

3,

4].

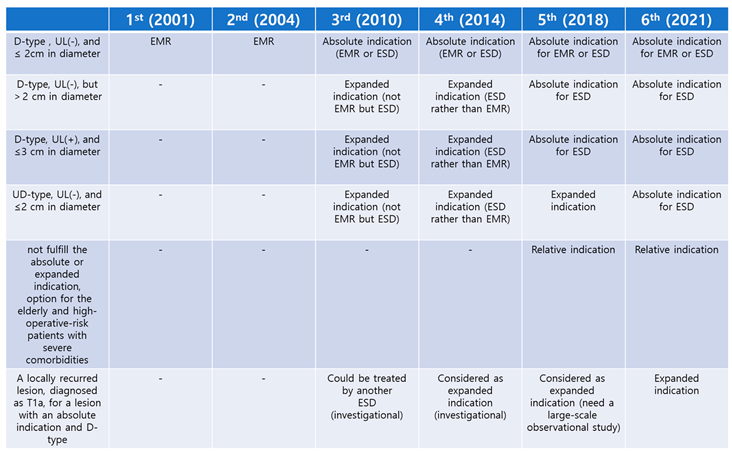

Table 1 summarizes indications for endoscopic treatment presented in the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines and the changes in these indications and terminology over the years.

In a meta-analysis comparing ESD and surgery for EGC with absolute and expanded indication, the 5-year overall survival, disease-specific survival, and disease-free survival rates were found to be similar for both treatments. However, the rates of recurrence, synchronous cancers, and metachronous cancers were higher with endoscopic treatment compared to surgery [

5]. The evolution of endoscopic techniques has expanded the indications for ESD, providing a safe and effective alternative to surgery

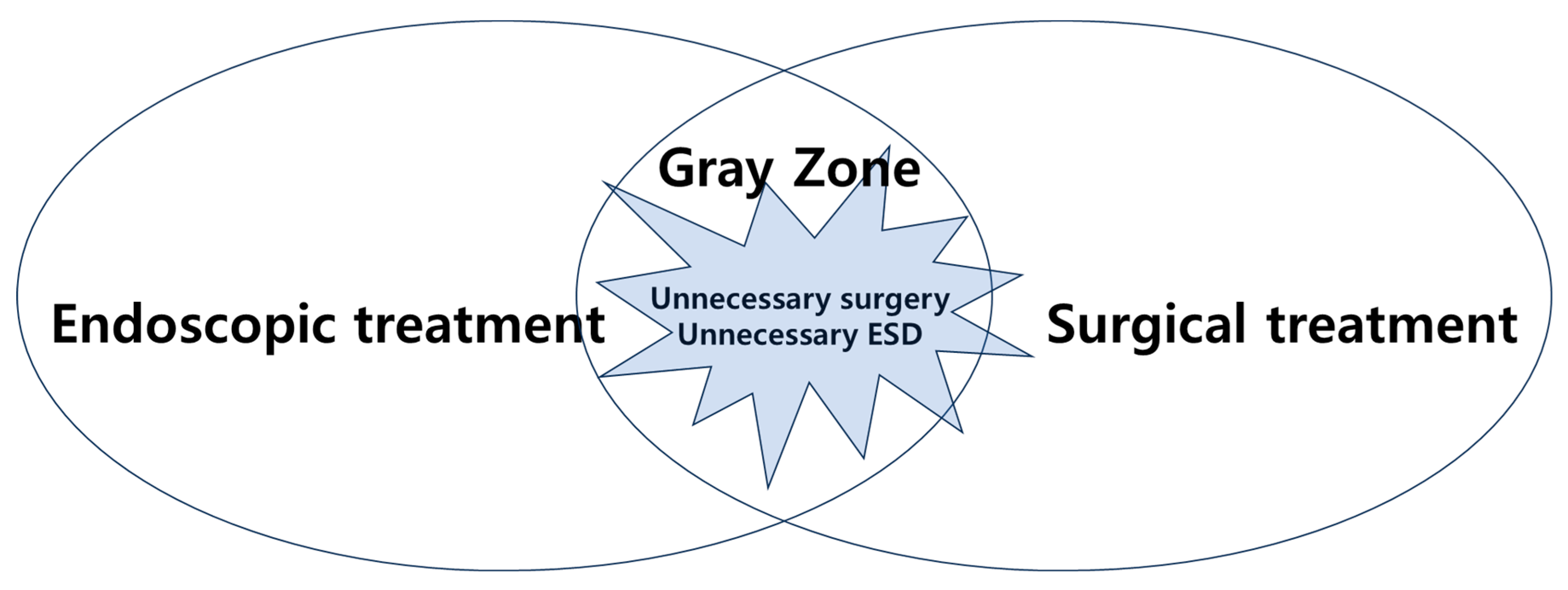

However, there are still ambiguities in the application of endoscopic treatment and surgery when determining the appropriate approach for EGC. In some cases, patients undergo unnecessary surgery or endoscopic treatment, highlighting the importance of reducing this gray zone (

Figure 2). At this point, the question arises: where does the definite boundary lie within the gray zone between endoscopic treatment and surgery? This issue persisted even during the transition from absolute indication to expanded indication in the past. The goal of this article is to explore the gray zone and the factors that influence it.

2. Factors Affecting Endoscopic Treatment

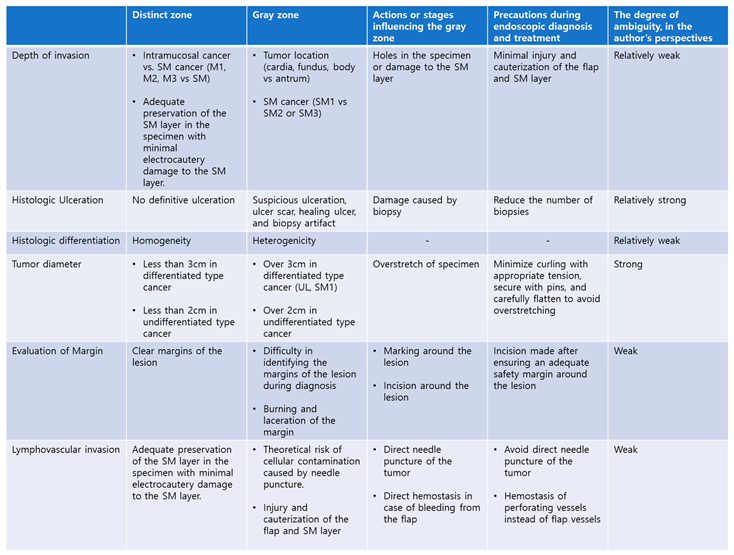

The six factors mentioned above serve as criteria for determining the feasibility of endoscopic treatment. When endoscopic treatment is performed, these factors also determine the success of the procedure or the need for additional surgery. However, it is important to consider whether the observations and measurements of these criteria can vary. Assessing the accuracy and reliability of these criteria is essential, especially considering that their interpretation may differ based on the clinical context or the stance of the endoscopist or pathologist.

2.1. Depth of Invasion

The stomach is anatomically divided into five distinct layers, each with clear histologic distinction. For example, it is usually easy to distinguish between invasion of the mucosa and submucosa, or between the submucosa and the muscularis propria.

Accurate and precise sectioning of histologic tissue is important for assessing the depth of tumor invasion. Creating dense sections of approximately 2-3 mm intervals allows for accuracy and precision. With such sectioning, it becomes clear which specific layer the tumor has invaded.

Challenges arise in more detailed assessments. In particular, it can be difficult to accurately measure and distinguish the degree of invasion in the submucosal (SM) layer, especially when determining whether the invasion is within 500 micrometers or classifying it as SM1, SM2, or SM3. The current 500-micrometer (SM1) standard is based on specimens resected through surgery, which include all five layers of the stomach. Until now, there has been no better parameter than this. However, the ESD flap comprises only the gastric mucosa and the SM layer, which is the loosest layer and can be significantly affected by handling during and after the procedure. Therefore, it is questionable whether the 500-micrometer measurement in surgical tissue is applicable to the ESD specimen. If a significant portion of the SM layer obtained through endoscopic procedures is below 500 micrometers or if there is significant damage, such as a large hole in the flap, it can create significant difficulties in accurate evaluation. Moreover, the flaps of the cardia, fundus and upper body (thinner flaps) and the flaps of the antrum (thicker flaps) have different thicknesses, but the current indication does not take this into account. These anatomical differences can further complicate the assessment, as the varying thickness of flaps between different stomach regions could influence the accuracy of depth measurement and subsequent diagnosis.

To accurately assess the depth of invasion, efforts should be made to minimize thermal injury to the SM layer during ESD treatment. To minimize damage to the flap and ensure precise treatment, careful observation of the layer during endoscopic procedures is also essential. Additionally, direct coagulation of the flap due to bleeding from the flap's vessels should be avoided to preserve the integrity of the SM layer and facilitate accurate evaluation. It is preferable to locate the perforating vessel and control the bleeding, rather than directly coagulating the bleeding site of the flap.

2.2. Histologic Ulceration

A gastric ulcer is defined as the destruction of the stomach lining extending beyond the muscularis mucosa [

6,

7]. In indication for endoscopic treatment, the criteria for ulceration are based on histologic rather than gross (endoscopic) ulceration [

4]. However, biopsy tissue alone cannot reliably determine ulceration, and histologic ulceration can only be fully evaluated after endoscopic treatment through a complete specimen [

4,

8]. Therefore, when determining indication for endoscopic treatment before the procedure, it is necessary to consider gross ulceration observed during endoscopy.

However, EGC has a lifecycle that includes depressed, ulcerative, and healing phases. The appearance of the lesion varies depending on the time of observation [

9]. There may be confusion due to a shallow ulceration or a healing ulcer due to ulcer medications seen endoscopically. Additionally, distinguishing true ulceration from biopsy-related artifacts can sometimes be challenging during histologic evaluation. In one study, it was found that the diagnosis of ulcers on endoscopy was overestimated in 38.7% of lesions, and they were particularly observed in the lower third of the stomach [

10].

2.3. Histologic Differentiation

Histologic differentiation in gastric cancers is determined by the quantitative predominant type of cellular differentiation, typically requiring that more than 50% of the tumor cells exhibit a specific differentiation [

11]. This criterion can lead to discrepancies between pre-treatment biopsy results and post-treatment specimen analysis after endoscopic treatment, as biopsies may not fully capture tumor heterogeneity [

12]. In a comprehensive study investigating differentiated type EGC, mixed histology was observed in 2.7% of cases, with larger tumor size, mid-third location, and moderate differentiation identified as independent risk factors for mixed histology in forceps biopsies [

13]. A meta-analysis of mixed histology and lymph node metastasis showed that both differentiated and undifferentiated type EGC demonstrated higher lymph node metastasis rates in mixed types compared to pure types [

14].

There are limitations of the pre-treatment biopsy in assessing the histologic predominance and mixed histology. As a result, fully understanding the histologic differentiation based solely on pre-treatment endoscopic appearance and biopsy results remains challenging in certain cases.

2.4. Tumor Diameter (Size)

The tumor diameter (size) is also an important factor in determining the choice between endoscopic treatment and surgical treatment for EGC. This factor is based on the final diameter (size) measured during histologic evaluation after the endoscopically resected specimen is fixed in formalin [

15]. The issue with this measurement is that there are no clear guidelines or criteria for the amount of tension to be applied when pinning and stretching the specimen. Additionally, the specimen may shrink during the formalin fixation process, further complicating the measurement. As mentioned earlier, there are anatomical differences in the thickness of the mucosa and submucosa in the different regions of the stomach.

However, there is no consideration of the differences in the deformation of the specimen depending on the location during the pinning and stretching process and after formalin fixation. The original indications for endoscopic treatment were based on surgically resected histologic specimens, so it makes sense that the final diameter (size) measured in the histologic specimen is used as the standard. Surgical specimens consist of five layers, including a strong proper muscle structure, while endoscopically resected specimens are composed only of the mucosa and submucosa, which is the loosest tissues in the stomach. It is unreasonable to expect the same changes for these two different specimen types. Furthermore, while making treatment decisions based solely on endoscopic observation, it is difficult to predict the final diameter (size) of the specimen that has been endoscopically resected and fixed in formalin.

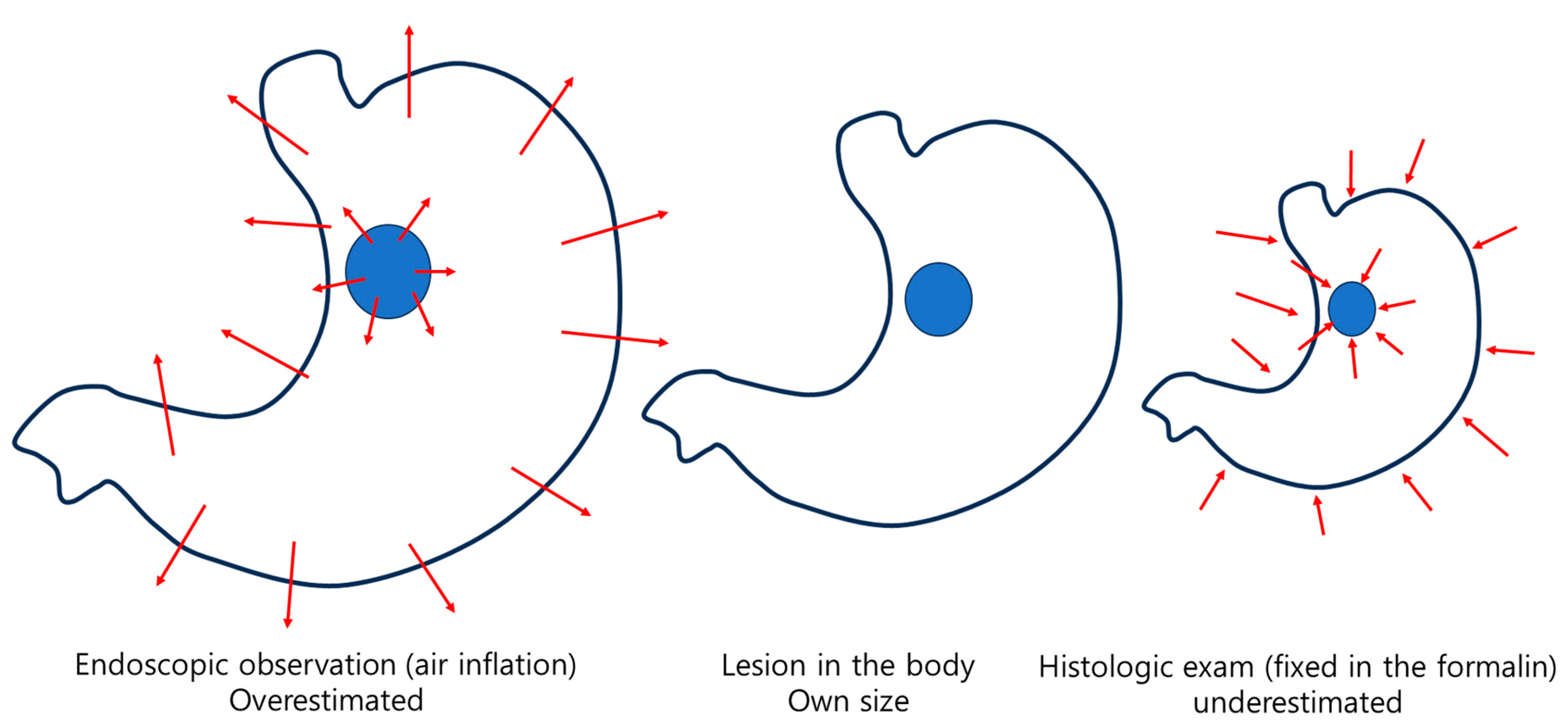

When resected tissue is fixed in formalin, it generally shrinks, although the extent varies depending on the location and composition of the tissue (

Figure 3). A study analyzing changes in the thickness and size of fresh and formalin-fixed specimens from laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy tissues showed notable differences between tissues containing full-thickness layers and those comprising only the mucosa and submucosa (mucosa/submucosa) of the fundus, corpus, and antrum [

16]. After formalin fixation, the full-thickness tissues showed a thickness increase of 4.4, 5.6, and 7.2 times and a size reduction of 21.7%, 23.2%, and 25.2% in the antrum, corpus, and fundus, respectively. Meanwhile, the mucosa/submucosa tissues showed a thickness increase of 1.8, 2.5, and 4.6 times and a size reduction of 28.0%, 32.9%, and 35.3% in the antrum, corpus, and fundus, respectively. According to this study, it can be concluded that formalin fixation causes an increase in tissue thickness and a reduction in size, with variations observed depending on the gastric location and type of specimen. A noteworthy aspect of this study is that, unlike the conventional practice of pinning and stretching the margins with multiple pins after endoscopic treatment, the tissue was fixed using only a single pin at its center. This approach was taken to compare changes in thickness and size between full-thickness tissue and mucosa/submucosa tissue.

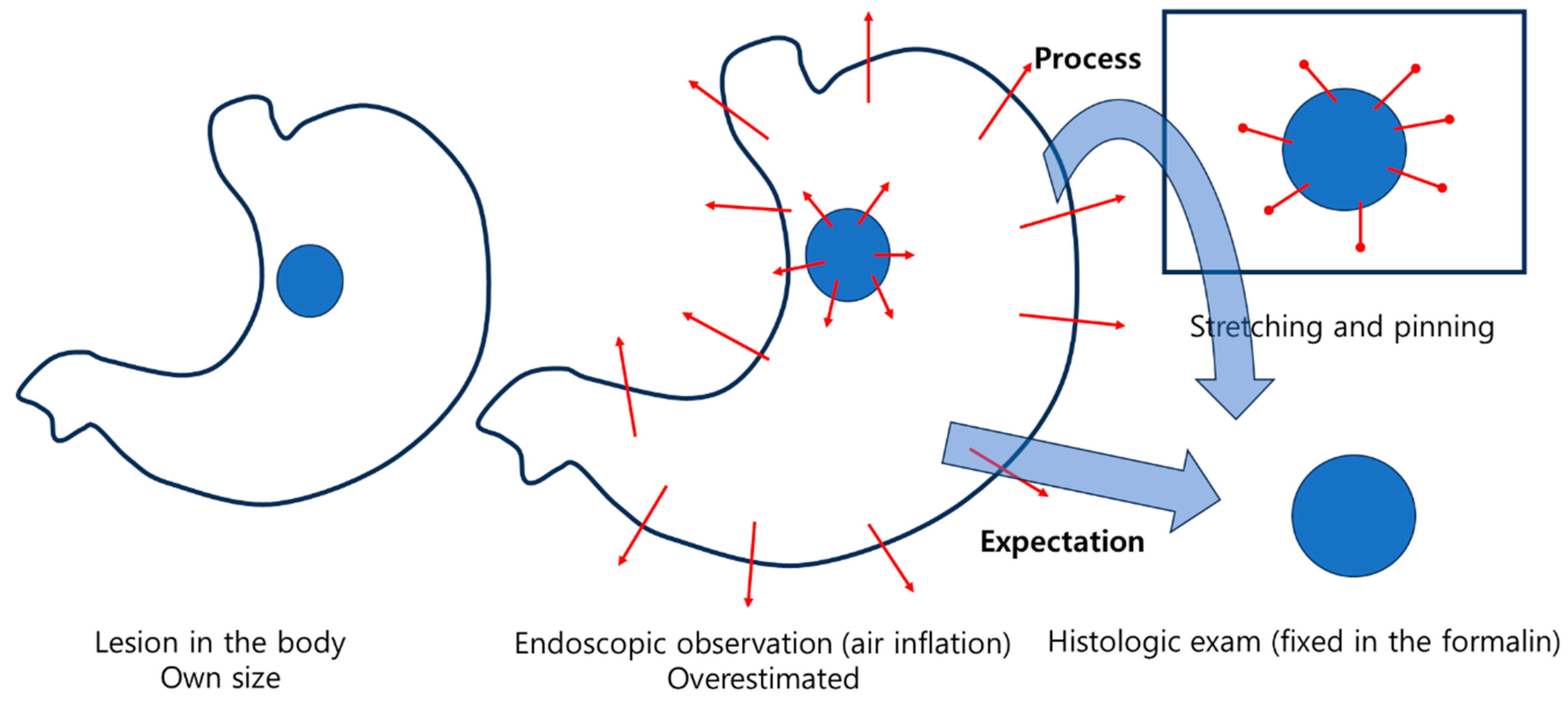

Ironically, two studies comparing the size of lesions observed during endoscopy with those in ESD specimens during histologic evaluation after formalin fixation found that the size of the lesions actually increased during histologic evaluation after fixation, contrary to the expected shrinkage during the fixation process [

17,

18]. This phenomenon may be attributed to the process of pinning and stretching the specimen after endoscopic resection, and then fixing it in formalin (

Figure 4). In one study [

17], Measurement discrepancies based on histologic lesion size were observed as follows: for lesion sizes of 1.0 cm or less, the measurement discrepancy mean was 0.04 cm; for lesion sizes between 1.0 and 2.0 cm, the mean was 0.14 cm; for lesion sizes between 2.0 and 3.0 cm, the mean was 0.31 cm; for lesion sizes between 3.0 and 4.0 cm, the mean was 0.68 cm; and for lesion sizes between 4.0 and 5.0 cm, the mean was 0.80 cm. In another study [

18], the overall median size of the lesions was 12.0 mm (IQR 10.0–15.0) during endoscopic observation and 12.0 mm (IQR 7.0–20.0) during histologic evaluation (P = 0.367). The overall median size discrepancy was 5.0 mm (IQR 2.0–9.0). When the tumor size exceeded 2 cm, the size observed on endoscopy was underestimated compared to the histologic measurement. Both studies showed that the size of the lesions increased during histologic evaluation compared to endoscopic observation, particularly as the lesions were larger and of undifferentiated type histology.

2.5. Evaluation of Margin

It is important to avoid challenges in assessing margins due to electrical injury during histologic evaluation. During endoscopic procedures, close attention should be taken to prevent electrocautery damage to the margins from marking dots, knives, or other instruments. After the procedure, resected specimens, which tend to curl easily, should be carefully stretched with minimal tension and pinned for proper fixation. Following these steps ensures that margin evaluation can be conducted with minimal ambiguity.

2.6. Lymphovascular Invasion

Several studies on needle-based tissue biopsy have raised concerns about cellular contamination. This issue typically arises when the needle directly punctures the tumor, as seen in procedures like liver biopsy or EUS-guided fine needle aspiration/biopsy. Although the likelihood of contamination is very low, it could result in the spread of tumor cells to surrounding tissues or errors in histologic diagnosis [

19,

20,

21]. While no documented cases of metastasis or other complications have been reported from directly puncturing a tumor using an endoscopic injector, the act of puncturing the tumor site for submucosal injection carries a theoretical risk of cellular contamination. There is also a theoretical possibility that these contaminated tumor cells could be introduced into blood vessels or lymphatic tissues. Therefore, during endoscopic procedures, it is essential to avoid directly puncturing the tumor when attempting submucosal injection.

In order to accurately assess lymphovascular invasion, electrocautery damage to the SM layer should be minimized. To minimize damage to the SM layer of the specimen, when bleeding occurs from the flap, it is preferable to locate the perforating vessel and control the bleeding rather than directly coagulating the bleeding site of the flap.

The Gray Zone Between Endoscopic Treatment and Surgical Treatment

The reason a gray zone arises is that, when deciding on the treatment for EGC, it is necessary to predict factors that can only be definitively determined after endoscopic resection (

Figure 5). These factors should be predicted solely using pre-treatment evaluations such as endoscopy, biopsy, computed tomography, and endoscopic ultrasonography. Based on these evaluations, the appropriate treatment strategy should be determined before treatment.

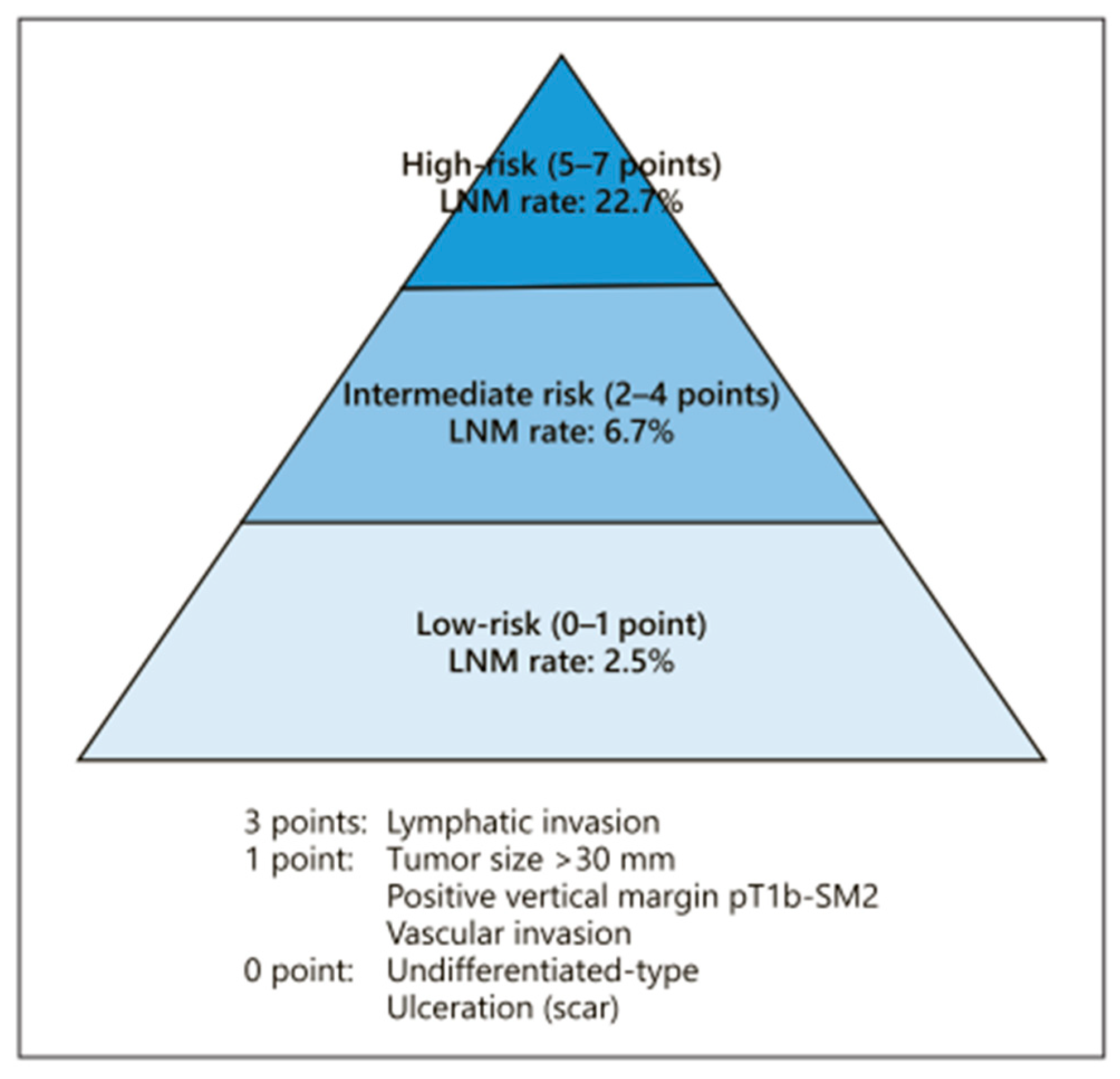

The endoscopic curability (eCura) scoring system (

Figure 6) [

22,

23,

24] may have a gray zone within the low-risk category (0–1 point). When factors such as ulceration, undifferentiated type, tumor diameter (size) over 3 cm, positive vertical margin, pT1b-SM2 invasion, or vascular invasion are present individually, the likelihood of lymph node metastasis is as low as 2.5%. Additional research and data collection are needed to clarify the prognosis when these factors are present independently

Table 2 summarizes the distinct zones and gray zones, the actions or steps that influence them, and efforts to minimize these uncertainties. Additionally, based on the authors' perspectives, the levels of understanding have been categorized into four stages: weak, relatively weak, relatively strong, and strong.

Among these factors, tumor diameter (size) is considered to be an area with high ambiguity. As previously mentioned, differences in processing methods between surgically resected specimens and endoscopically resected specimens contribute to this ambiguity. While size assessments based on surgically resected specimens may underestimate the actual size of the lesion in vivo, measurements from endoscopically resected specimens may overestimate the size due to the pinning and stretching process during specimen preparation.

In fact, studies on upper third lesions [

25] and undifferentiated type EGC larger than 2 cm [

26,

27] suggest that the current thresholds for tumor diameter (size)—3 cm for differentiated type EGC and 2 cm for undifferentiated type EGC—seem to require further revision and expansion. Of course, in cases of ulcers, submucosal invasion greater than 500 micrometers, and undifferentiated type gastric cancer, the possibility of lymph node metastasis may be higher, indicating the need for the discovery and development of other clinical and histologic factors that can complement and assess these risks.

There are notable differences in the factors influencing the decision-making process between endoscopic and surgical treatment in the esophagus [

28,

29] and colon [

30], where tumor diameter (size) is not considered a risk factor. Unlike other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, it is questionable whether tumor diameter (size) is a significant factor in the stomach. In fact, considering the progression from absolute to expanded indication, it seems that factors statistically significant in surgical specimens were taken into account. It is well known that as tumor diameter (size) increases, the tumor tends to be more aggressive (with deeper invasion and a higher likelihood of lymph node metastasis). However, just as we observe superficial-type cancers in the esophagus or laterally spreading tumors in the colon, we can also observe EGCs in the stomach that spread laterally. These types of EGCs can be good candidates for effective endoscopic treatment.

As endoscopists, we have already faced similar challenges during the transition from absolute indication to expanded indication for endoscopic treatment. Nevertheless, we successfully established expanded indication and accumulated valuable clinical experience. In particular, East Asia, including countries like Japan, China, and Korea, has a high incidence of gastric cancer, a significant number of EGC detections due to screening programs, and a growing emphasis on quality of life. Additionally, with an aging population, there is an increasing number of patients for whom surgery is not a feasible option. In this context, efforts to narrow the gray zone have become necessary. It seems reasonable, with appropriate caution, for treatment indications to rely more on the outcomes of endoscopic treatment rather than solely on those established from surgical treatment outcomes.

References

- Yamao, T.; Shirao, K.; Ono, H.; Kondo, H.; Saito, D.; Yamaguchi, H.; Sasako, M.; Sano, T.; Ochiai, A.; Yoshida, S. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis from intramucosal gastric carcinoma. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 1996, 77, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoda, T.; Yanagisawa, A.; Sasako, M.; Ono, H.; Nakanishi, Y.; Shimoda, T.; Kato, Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric cancer 2000, 3, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- jp, J.G.C.A.j.k.k.-m.a. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric cancer 2011, 14, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- jp, J.G.C.A.j.k.k.-m.a. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2021. Gastric Cancer 2023, 26, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelfatah, M.M.; Barakat, M.; Ahmad, D.; Ibrahim, M.; Ahmed, Y.; Kurdi, Y.; Grimm, I.S.; Othman, M.O. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery in early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology 2019, 31, 418–424. [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans, N.D.; Naesdal, J. Systematic review: ulcer definition in NSAID ulcer prevention trials. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2008, 27, 465–472. [Google Scholar]

- Bereda, G. Peptic Ulcer disease: definition, pathophysiology, and treatment. Journal of Biomedical and Biological Sciences 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.S.; Kook, M.C.; Kim, B.H.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, D.W.; Gu, M.J.; Shin, O.R.; Choi, Y.; Lee, W.; Kim, H.; et al. A Standardized Pathology Report for Gastric Cancer: 2nd Edition. J Gastric Cancer 2023, 23, 107–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAKITA, T. Endoscopy in the diagnosis of early ulcer cancer. Clinics in Gastroenterology 1973, 2, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuuchi, Y.; Takizawa, K.; Kakushima, N.; Kawata, N.; Yoshida, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kishida, Y.; Ito, S.; Imai, K.; Ishiwatari, H. Discrepancy between endoscopic and pathological ulcerative findings in clinical intramucosal early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2021, 24, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- jp, J.G.C.A.j.k.k.-m.a. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric cancer 2011, 14, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Takao, M.; Kakushima, N.; Takizawa, K.; Tanaka, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Matsubayashi, H.; Kusafuka, K.; Ono, H. Discrepancies in histologic diagnoses of early gastric cancer between biopsy and endoscopic mucosal resection specimens. Gastric Cancer 2012, 15, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C.N.; Chung, H.; Park, J.C.; Lee, H.; Shin, S.K.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, Y.C. Early gastric cancer with mixed histology predominantly of differentiated type is a distinct subtype with different therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic resection. Surg Endosc 2015, 29, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gu, X.; Tao, R.; Huo, J.; Hu, Z.; Sun, F.; Ni, J.; Wang, X. Relationship between histological mixed-type early gastric cancer and lymph node metastasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one 2022, 17, e0266952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Yao, K.; Fujishiro, M.; Oda, I.; Uedo, N.; Nimura, S.; Yahagi, N.; Iishi, H.; Oka, M.; Ajioka, Y. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Digestive Endoscopy 2021, 33, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiyiltepe, H.; Ergin, A.; Somay, A.; Esen Bulut, N.; Fersahoğlu, M.M.; Köroğlu, M.; Karip, A.B.; Akyüz, Ü.; Memişoğlu, K. The effects of formalin solution on wall thickness and size in stomach resection materials. Bosphorus Medical Journal 2021, 8, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, S.G.; Im, J.P.; Kim, J.S.; Jung, H.C. Endoscopic estimation of tumor size in early gastric cancer. Digestive diseases and sciences 2013, 58, 2329–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C.N.; Song, M.K.; Kang, D.R.; Chung, H.S.; Park, J.C.; Lee, H.; Shin, S.K.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, Y.C. Size discrepancy between endoscopic size and pathologic size is not negligible in endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Surgical endoscopy 2014, 28, 2199–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maducolil, J.E.; Girgis, S.; Mustafa, M.A.; Gittens, J.; Fok, M.; Mahapatra, S.; Vimalachandran, D.; Jones, R. Risk of tumour seeding in patients with liver lesions undergoing biopsy with or without concurrent ablation: meta-analysis. BJS open 2024, 8, zrae050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.-Y.; Wu, B.-H.; Shen, X.-Y.; Peng, T.-L.; Li, D.-F.; Wei, C.; Yu, Z.-C.; Luo, M.-H.; Xiong, F.; Wang, L.-S. Overlooked risk for needle tract seeding following endoscopic ultrasound-guided minimally invasive tissue acquisition. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2020, 26, 6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, W.T.-Y.; Coyle, W.J.; Hasteh, F.; Peterson, M.R.; Savides, T.J.; Krinsky, M.L. Malignant cell contamination may lead to false-positive findings at endosonographic fine needle aspiration for tumor staging. Endoscopy 2014, 46, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, W.; Gotoda, T.; Oyama, T.; Kawata, N.; Takahashi, A.; Yoshifuku, Y.; Hoteya, S.; Nakamura, K.; Hirano, M.; Esaki, M. Is radical surgery necessary in all patients who do not meet the curative criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection in early gastric cancer? A multi-center retrospective study in Japan. Journal of gastroenterology 2017, 52, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, W.; Gotoda, T.; Oyama, T.; Kawata, N.; Takahashi, A.; Yoshifuku, Y.; Hoteya, S.; Nakagawa, M.; Hirano, M.; Esaki, M. A scoring system to stratify curability after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer:“eCura system”. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2017, 112, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, W.; Gotoda, T.; Koike, T.; Uno, K.; Asano, N.; Imatani, A.; Masamune, A. Is additional gastrectomy required for elderly patients after endoscopic submucosal dissection with endoscopic curability C-2 for early gastric cancer? Digestion 2022, 103, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Yoon, H.M.; Ryu, K.W.; Kim, Y.-W.; Kook, M.-C.; Eom, B.W. Risks and benefits of additional surgery for early gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach meeting non-curative resection criteria after endoscopic submucosal dissection. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2022, 20, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-J.; Nam, S.Y.; Min, B.-H.; Ahn, J.Y.; Jang, J.-Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, W.-S.; Lee, B.E.; Joo, M.K. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated intramucosal early gastric cancer larger than 2 cm. Gastric Cancer 2021, 24, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.Y.; Ryu, C.B.; Lee, M.S.; Dua, K.S. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for undifferentiated type early gastric cancer over 2 cm with R0 resection. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2024, 16, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermannová, R.; Alsina, M.; Cervantes, A.; Leong, T.; Lordick, F.; Nilsson, M.; van Grieken, N.; Vogel, A.; Smyth, E. Oesophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Annals of Oncology 2022, 33, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Ishihara, R.; Ishikawa, H.; Ito, Y.; Oyama, T.; Oyama, T.; Kato, K.; Kato, H.; Kawakubo, H.; Kawachi, H. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2022 edited by the Japan esophageal society: part 1. Esophagus 2023, 20, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Muro, K.; Saito, Y.; Ito, Y.; Ajioka, Y.; Hamaguchi, T.; Hasegawa, K.; Hotta, K.; Ishida, H.; Ishiguro, M. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. International journal of clinical oncology 2020, 25, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).