Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

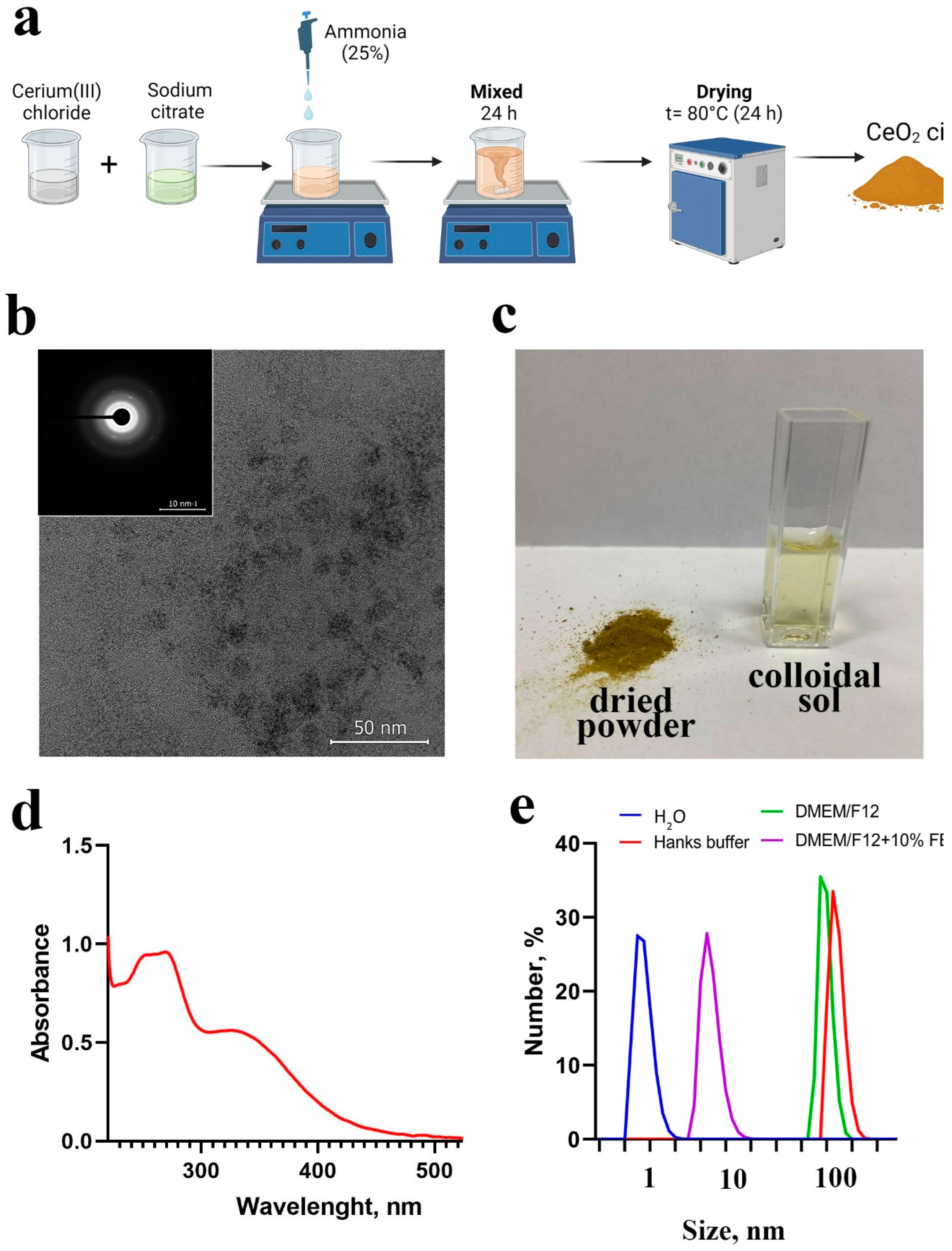

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of CeO2 NPs

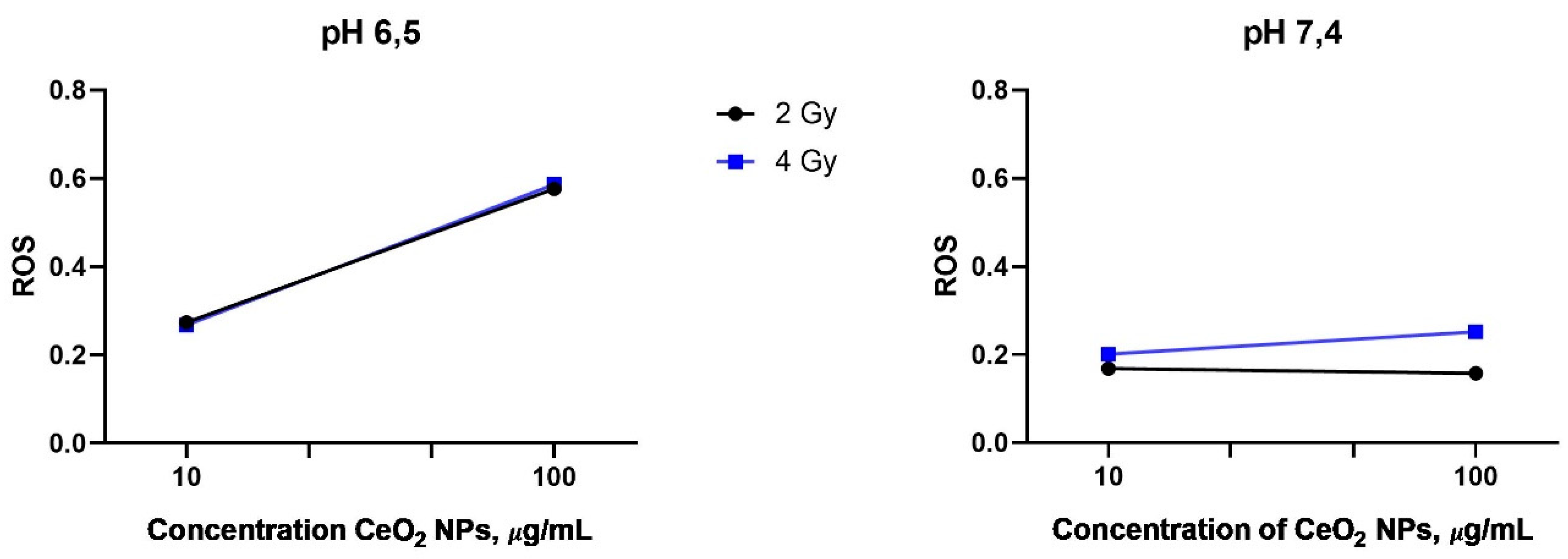

2.2. Detection of ROS Generation after X-Ray Irradiation of CeO2 NPs

2.3. Cell Culture

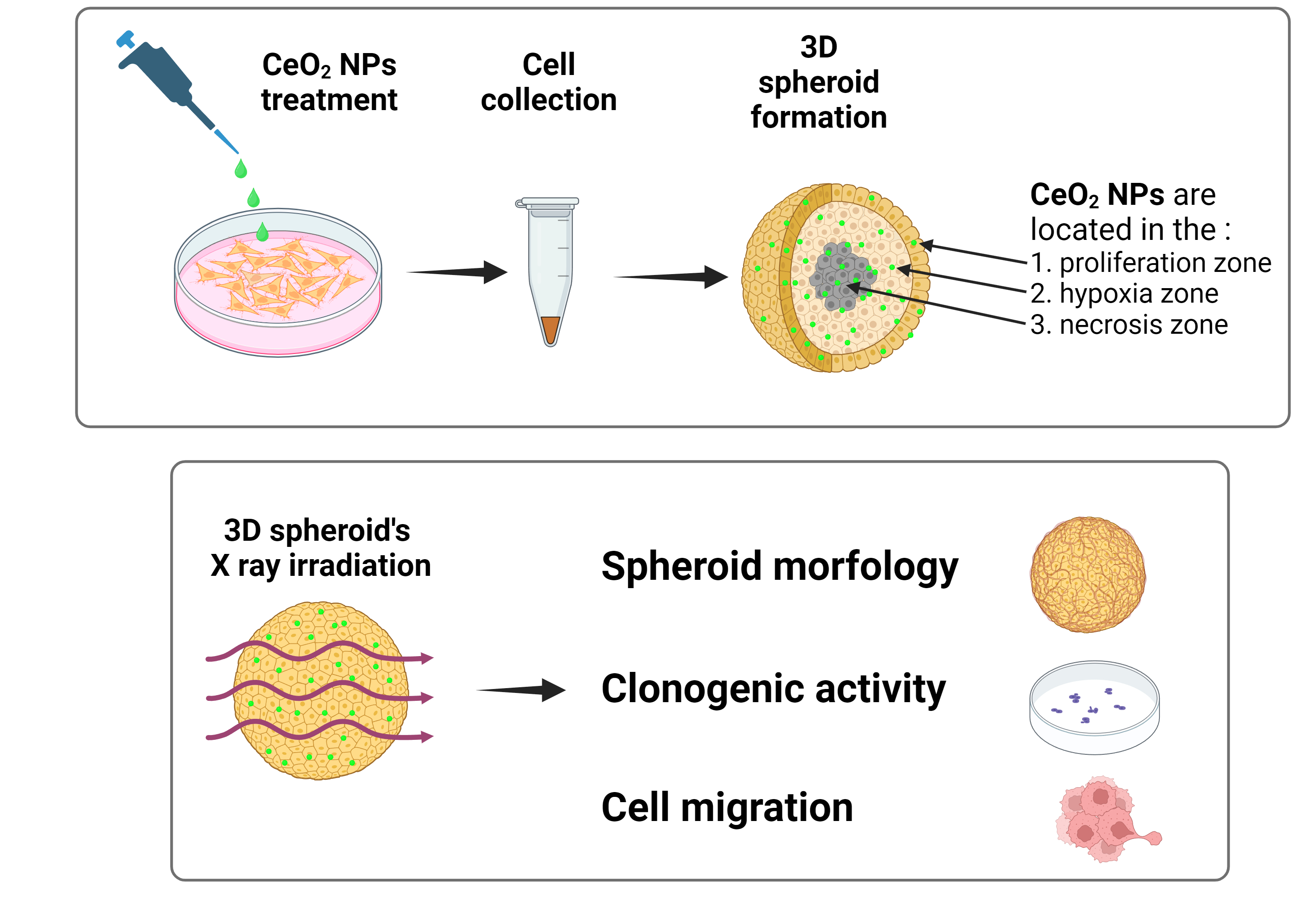

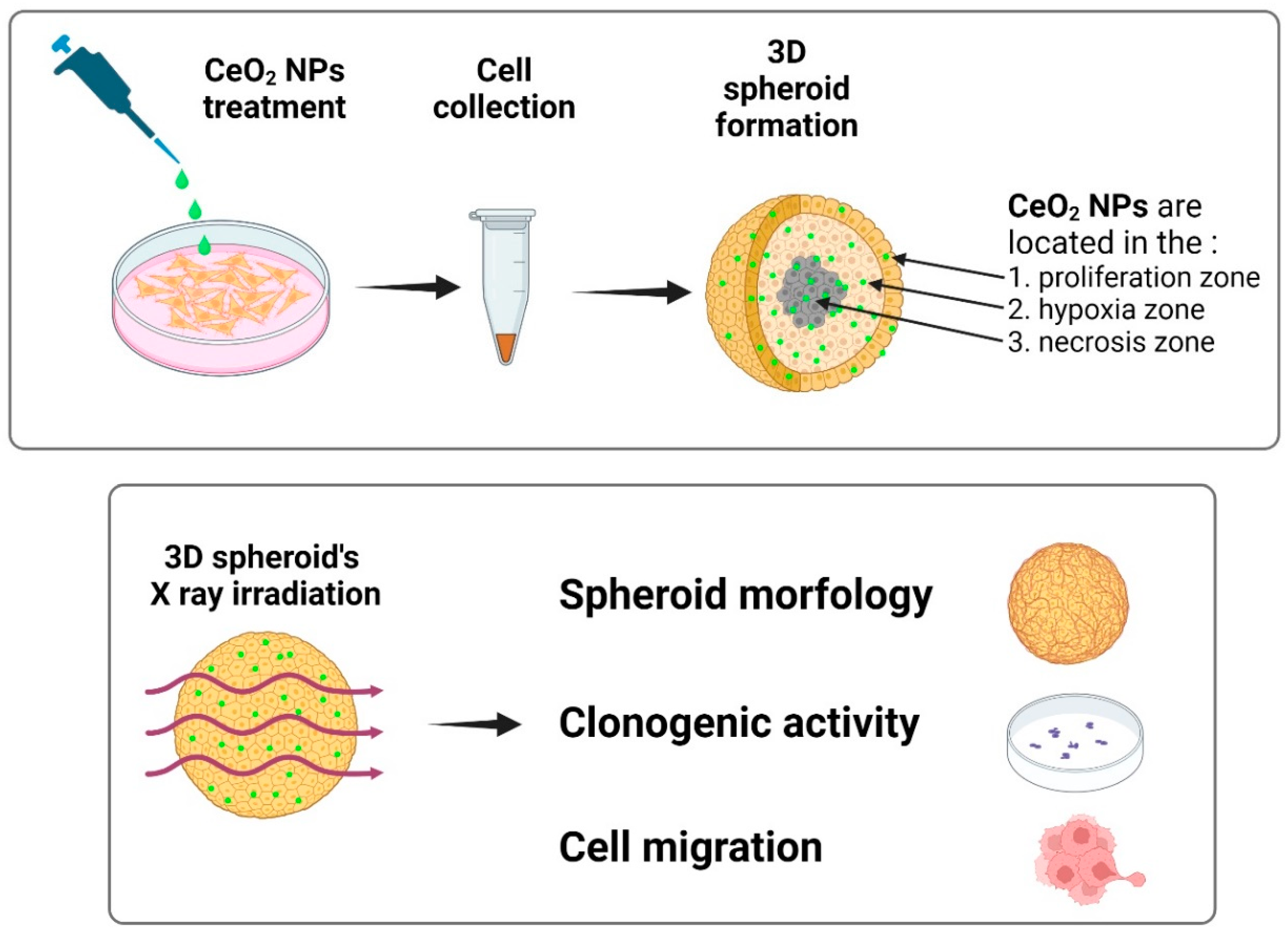

2.4. Formation of Spheroids

2.5. Irradiation of Spheroids

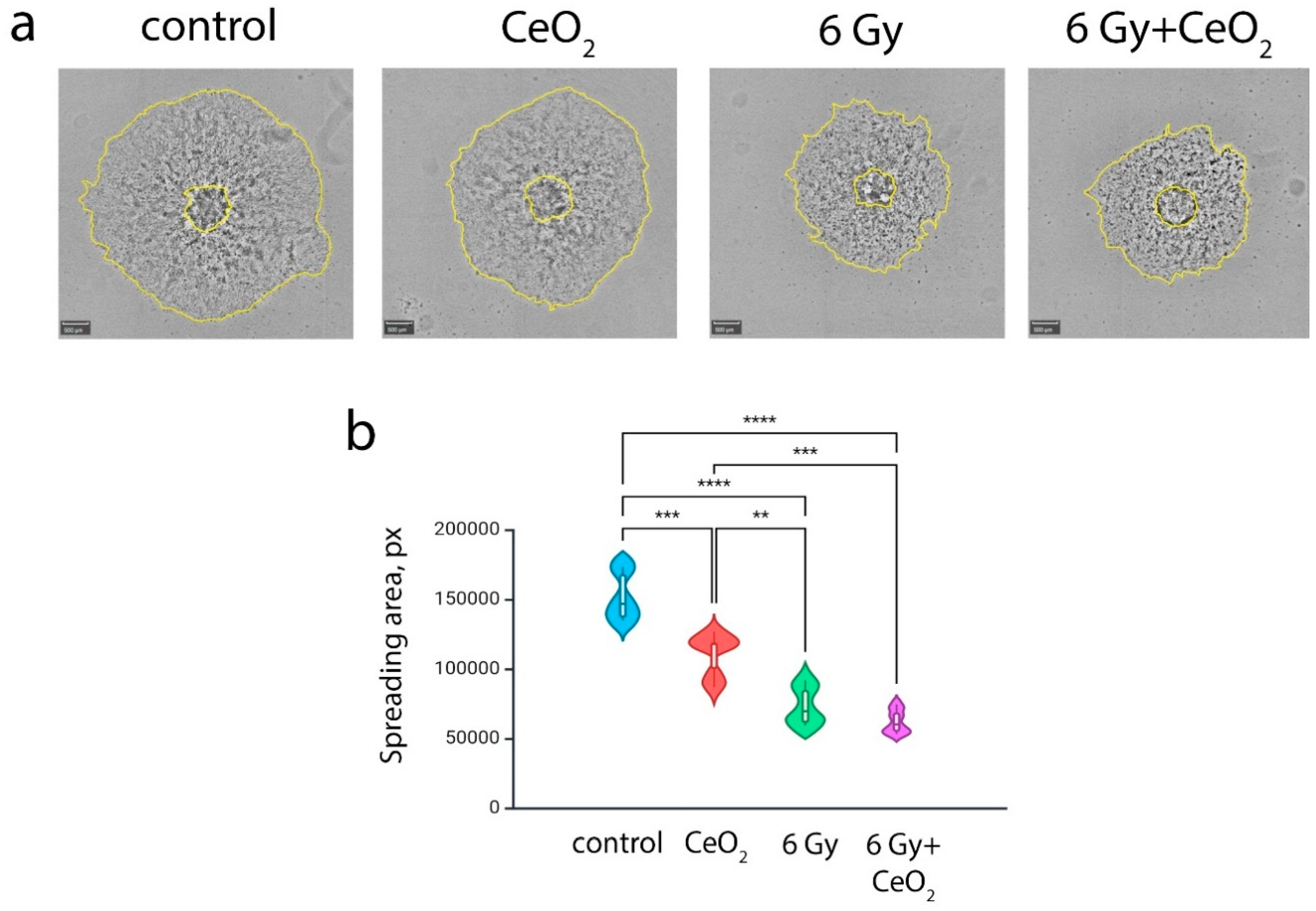

2.6. Analysis of Cell Migration from Irradiated Spheroid

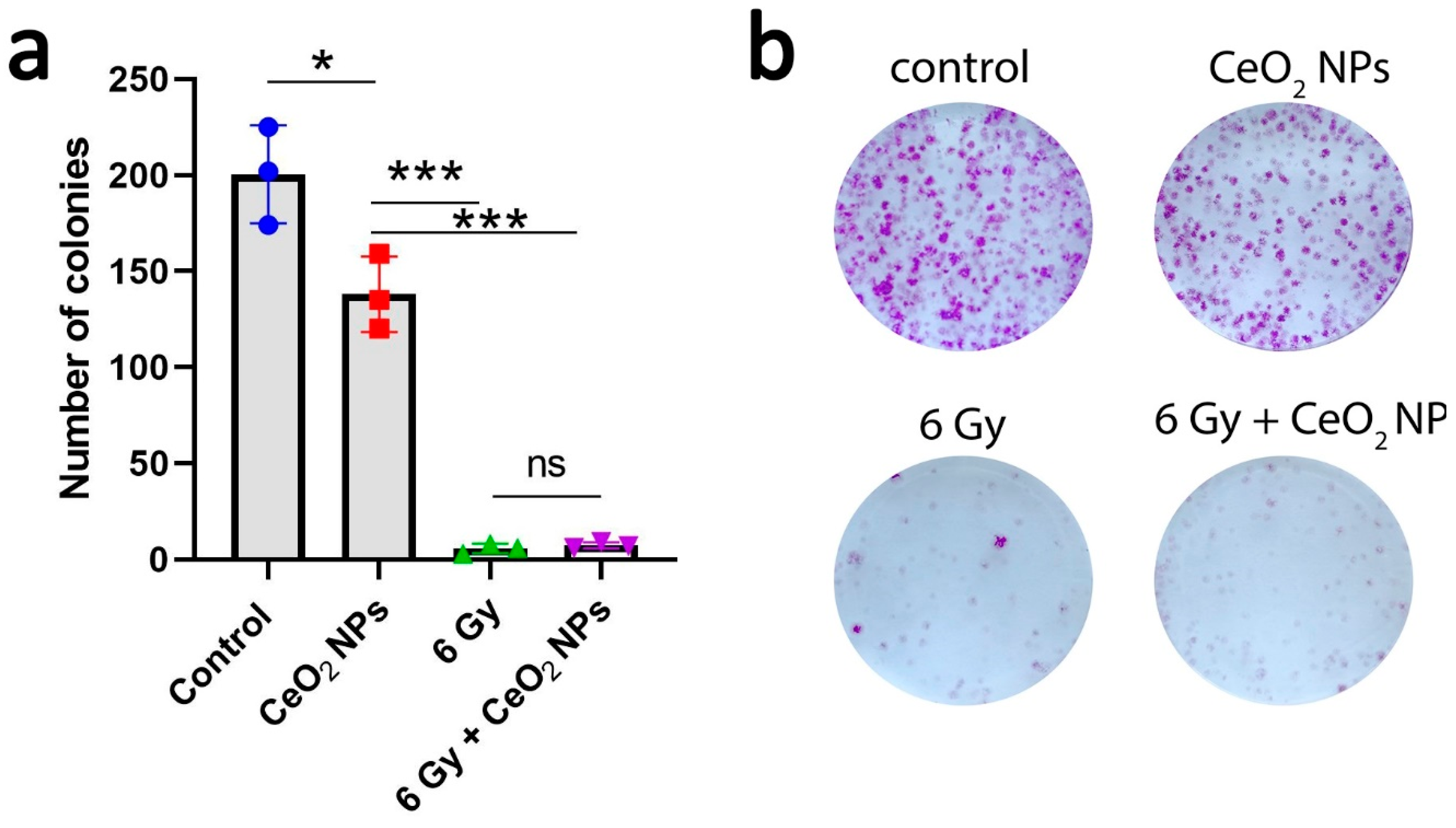

2.7. Colony Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Physico-Chemical Properties of CeO2 NPs

Discussion

Funding

Acknowledgements

References

- McNamara, K.; Tofail, S.A.M. Nanoparticles in Biomedical Applications. Adv. Phys. X 2017, 2, 54–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the Clinic: An Update. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2019, 4, e10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvalot, S.; Le Pechoux, C.; De Baere, T.; Kantor, G.; Buy, X.; Stoeckle, E.; Terrier, P.; Sargos, P.; Coindre, J.M.; Lassau, N.; et al. First-in-Human Study Testing a New Radioenhancer Using Nanoparticles (NBTXR3) Activated by Radiation Therapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, S. Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia Therapy for Malignant Brain Tumors--an Ethical Discussion. Nanomedicine Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2009, 5, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, F.; Mignot, A.; Mowat, P.; Louis, C.; Dufort, S.; Bernhard, C.; Denat, F.; Boschetti, F.; Brunet, C.; Antoine, R.; et al. Ultrasmall Rigid Particles as Multimodal Probes for Medical Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2011, 50, 12299–12303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, F.; Tran, V.L.; Thomas, E.; Dufort, S.; Rossetti, F.; Martini, M.; Truillet, C.; Doussineau, T.; Bort, G.; Denat, F.; et al. AGuIX® from Bench to Bedside-Transfer of an Ultrasmall Theranostic Gadolinium-Based Nanoparticle to Clinical Medicine. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20180365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.Y.; Park, T.J.; Kim, M.I. Recent Research Trends and Future Prospects in Nanozymes. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 756278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Cui, H.; Yan, X.; Fan, K. Nanozyme-Based Catalytic Theranostics. RSC Adv. 2019, 10, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.; Han, M.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, A.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; et al. Mn3O4 Nanozyme Loaded Thermosensitive PDLLA-PEG-PDLLA Hydrogels for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 33273–33287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Yang, F.; Yue, W. The Age of Vanadium-Based Nanozymes: Synthesis, Catalytic Mechanisms, Regulation and Biomedical Applications. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Nano-Gold as Artificial Enzymes: Hidden Talents. Adv. Mater. Deerfield Beach Fla 2014, 26, 4200–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedone, D.; Moglianetti, M.; De Luca, E.; Bardi, G.; Pompa, P.P. Platinum Nanoparticles in Nanobiomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4951–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Fan, K.; Yan, X. Iron Oxide Nanozyme: A Multifunctional Enzyme Mimetic for Biomedical Applications. Theranostics 2017, 7, 3207–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.L.; Shcherbakov, A.B.; Zholobak, N.M.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Ivanov, V.K. Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles as Third-Generation Enzymes (Nanozymes). Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 2017, 760–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wang, E. Nanomaterials with Enzyme-like Characteristics (Nanozymes): Next-Generation Artificial Enzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6060–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, A.B.; Ivanov, V.K.; Zholobak, N.M.; Ivanova, O.S.; Krysanov, E.Yu.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Spivak, N.Ya.; Tretyakov, Yu.D. Nanocrystalline Ceria Based Materials—Perspectives for Biomedical Application. Biophysics 2011, 56, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.; Shcherbakov, A.; Usatenko, A.V. Structure-Sensitive Properties and Biomedical Applications of Nanodispersed Cerium Dioxide. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2009, 78, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orera, V.M.; Merino, R.I.; Peña, F. Ce3+↔Ce4+ Conversion in Ceria-Doped Zirconia Single Crystals Induced by Oxido-Reduction Treatments. Solid State Ion. 1994, 72, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckert, E.; Karakoti, A.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. The Role of Cerium Redox State in the SOD Mimetic Activity of Nanoceria. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2705–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirmohamed, T.; Dowding, J.M.; Singh, S.; Wasserman, B.; Heckert, E.; Karakoti, A.S.; King, J.E.S.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. Nanoceria Exhibit Redox State-Dependent Catalase Mimetic Activity. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2736–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Qi, S.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Fan, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhuo, S.; Zhu, C. Fabrication of Highly Active Phosphatase-like Fluorescent Cerium-Doped Carbon Dots for in Situ Monitoring the Hydrolysis of Phosphate Diesters. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41551–41559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippova, A.D.; Sozarukova, M.M.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Kottsov, S.Y.; Cherednichenko, K.A.; Ivanov, V.K. Peroxidase-like Activity of CeO2 Nanozymes: Particle Size and Chemical Environment Matter. Molecules 2023, 28, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ta, H.T. Different Approaches to Synthesising Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Corresponding Physical Characteristics, and ROS Scavenging and Anti-Inflammatory Capabilities. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 7291–7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seal, S.; Jeyaranjan, A.; Neal, C.J.; Kumar, U.; Sakthivel, T.S.; Sayle, D.C. Engineered Defects in Cerium Oxides: Tuning Chemical Reactivity for Biomedical, Environmental, & Energy Applications. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 6879–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jin, M.; Ma, T.; Guo, J.; Zhai, X.; Du, Y. Recent Advances on Cerium Oxide-Based Biomaterials: Toward the Next Generation of Intelligent Theranostics Platforms. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2300748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.L.Y.; Moonshi, S.S.; Ta, H.T. Nanoceria: An Innovative Strategy for Cancer Treatment. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2023, 80, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpaslan, E.; Yazici, H.; Golshan, N.H.; Ziemer, K.S.; Webster, T.J. pH-Dependent Activity of Dextran-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles on Prohibiting Osteosarcoma Cell Proliferation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, P.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, F. Near-Infrared Upconversion Mesoporous Cerium Oxide Hollow Biophotocatalyst for Concurrent pH-/H2 O2 -Responsive O2 -Evolving Synergetic Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. Deerfield Beach Fla 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Hu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Qu, J.; Liu, L. Oxygen Self-Supplied Upconversion Nanoplatform Loading Cerium Oxide for Amplified Photodynamic Therapy of Hypoxic Tumors. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 11, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Cheng, Y.; Yan, J.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Song, P.; Zhang, H. Polydopamine and Ammonium Bicarbonate Coated and Doxorubicin Loaded Hollow Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles for Synergistic Tumor Therapy. Nano Res. 2019, 12, 2947–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, M.; Alili, L.; Karaman, E.; Das, S.; Gupta, A.; Seal, S.; Brenneisen, P. Combination of Conventional Chemotherapeutics with Redox-Active Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles--a Novel Aspect in Cancer Therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 1740–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koula, G.; Yakati, V.; Rachamalla, H.K.; Bhamidipati, K.; Kathirvel, M.; Banerjee, R.; Puvvada, N. Integrin Receptor-Targeted, Doxorubicin-Loaded Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Delivery to Combat Glioblastoma. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 1389–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saranya, J.; Sreeja, B.S.; Senthil Kumar, P. Microwave Assisted Cisplatin-Loaded CeO2/GO/c-MWCNT Hybrid as Drug Delivery System in Cervical Cancer Therapy. Appl. Nanosci. 2023, 13, 4219–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.L.; Abakumov, M.A.; Savintseva, I.V.; Ermakov, A.M.; Popova, N.R.; Ivanova, O.S.; Kolmanovich, D.D.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Ivanov, V.K. Biocompatible Dextran-Coated Gadolinium-Doped Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles as MRI Contrast Agents with High T1 Relaxivity and Selective Cytotoxicity to Cancer Cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 6586–6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukavin, N.N.; Ivanov, V.K.; Popov, A.L. Calcein-Modified CeO2 for Intracellular ROS Detection: Mechanisms of Action and Cytotoxicity Analysis In Vitro. Cells 2023, 12, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryacheva, O.A.; Tsyupka, D.V.; Pigarev, S.V.; Strokin, P.D.; Kovyrshina, A.A.; Moiseev, A.A.; Popova, N.R.; Goryacheva, I.Y. Сerium Dioxide Nanoparticles for Luminescence Based Analytical Systems: Challenging Nanosensor and Effective Label. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 174, 117665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, M.; Piccinini, F.; Arienti, C.; Zamagni, A.; Santi, S.; Polico, R.; Bevilacqua, A.; Tesei, A. 3D Tumor Spheroid Models for in Vitro Therapeutic Screening: A Systematic Approach to Enhance the Biological Relevance of Data Obtained. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daunys, S.; Janonienė, A.; Januškevičienė, I.; Paškevičiūtė, M.; Petrikaitė, V. 3D Tumor Spheroid Models for In Vitro Therapeutic Screening of Nanoparticles. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1295, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambale, F.; Lavrentieva, A.; Stahl, F.; Blume, C.; Stiesch, M.; Kasper, C.; Bahnemann, D.; Scheper, T. Three Dimensional Spheroid Cell Culture for Nanoparticle Safety Testing. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 205, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakhshiteh, F.; Bagheri, Z.; Soleimani, M.; Ahvaraki, A.; Pournemat, P.; Alavi, S.E.; Madjd, Z. Heterotypic Tumor Spheroids: A Platform for Nanomedicine Evaluation. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Q.; Sun, H.; Fang, C.; Xia, F.; Liao, H.; Lee, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, A.; Ren, J.; Guo, X.; et al. Catalytic Activity Tunable Ceria Nanoparticles Prevent Chemotherapy-Induced Acute Kidney Injury without Interference with Chemotherapeutics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed-Cox, A.; Pandzic, E.; Johnston, S.T.; Heu, C.; McGhee, J.; Mansfeld, F.M.; Crampin, E.J.; Davis, T.P.; Whan, R.M.; Kavallaris, M. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Nanoparticles in Live Tumor Spheroids Impacted by Cell Origin and Density. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2022, 341, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Wang, W.; Xie, Z.; Centurion, F.; Sun, B.; Paterson, D.J.; Tsao, S.C.-H.; Chu, D.; Shen, Y.; Mao, G.; et al. Size-Dependent Penetration of Nanoparticles in Tumor Spheroids: A Multidimensional and Quantitative Study of Transcellular and Paracellular Pathways. Small Weinh. Bergstr. Ger. 2024, 20, e2304693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franken, N.A.P.; Rodermond, H.M.; Stap, J.; Haveman, J.; van Bree, C. Clonogenic Assay of Cells in Vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).