Introduction

In Europe, for over 2 years, we have been dealing with a potential source of trauma for individuals: the war in Ukraine. Therefore, our research focused on answering the question: how do Ukrainian citizens, both those who remained in Ukraine and refugees to other countries, cope with threats resulting from the ongoing war, and also: what role do flexible resources related to subjective dispositions play in coping with these threats. Thus, with our research and theoretical approaches presented in this article (Berzonsky's model of identity styles and Senejko's function-action approach to psychological defense), we wish to contribute to the dynamic discussion on flexible coping.

Different approaches to the issue of coping flexibility

Although relatively little attention has been paid to the study of flexible coping, at least several directions of analysis of this issue can be distinguished. Thus, some researchers define coping flexibility: 1/ as the implementation of a wide range of coping strategies that facilitate adjustment (Cheng et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2022); 2/ as a well-balanced coping profile, i.e. moderate use of various strategies, without preferring any particular type of strategy (Kaluza, 2000); 3/ as an equal possibility (readiness) to use two "superstrategies", such as taking up or avoiding the fight for a favorable course of events in a difficult situation (Kaluza, 2000; Cheng et al., 2014).

Researchers emphasizing the dynamic process underlying flexible coping, cross-situational variability, consider coping effectiveness in relation to contextual features and emphasize the temporary and changing nature of coping, occurring at the interface of changing personal and situational attitudes (e.g., problem-focused coping is more helpful in some stressful situations and not in others) (Williams, 2002; Kato, 2020).

However, response variability is considered adaptive only when: responses can meet a range of specific situational demands, and therefore the management of coping strategies plays an important role here (Cheng et al., 2014; Kato, 2020). George Bonanno, for example, in his own flexibility sequence theory (FST), which relates to potentially traumatic life events PTE, characterizes the skills that secure the process of developing, moment by moment, the best response, and then engaging in this response and monitoring feedback (Bonanno, 2021; Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Cheng et al., 2014).

Tsukas Kato (2020), in his dual-process theory, emphasizes the role of two coping processes: abandonment, i.e. the ability to give up ineffective strategies and change them to more effective ones, and the higher-order meta-coping process, the main function of which is to determine whether the abandonment-coping cycle should be repeated or not (Kato, 2020; Bonanno and Burton, 2013).

The above-presented brief description of the areas of research on flexible coping, especially in situations of threat and trauma, shows that researchers pay primary attention to the variability and ability to monitor the activation of coping strategies and their diversity - included in the process of flexible coping. However, little space (too little?) is devoted to the motivational aspects of the coping process. Although, for example, Bonanno recently enriched his model with the assumption that flexible response to traumatic stress requires at least some commitment in its content, which he called a flexibility mindset, general conviction, that helps people engage in specific tasks (Bonanno, 2021). Bonanno claims that personality traits related to resilience, e.g. optimism, self-efficacy, or challenge orientation - favor this involvement, creating a motivational basis for flexible response to traumatic events (Bonanno, 2021). However, we suppose that current proposals for flexible coping focus rather on the role of lower-level regulation (Cheng et al., 2014; Bonanno, 2021; Kato, 2020), i.e. self-regulatory processes related to the course of executive functions, rather than on the system of basic, most important regulatory standards for an individual, such as basic needs, values, meanings and significances that are not limited to the current context, external or internal, in which the coping process takes place.

A number of research results confirm the important role of flexible coping with threats and traumas, assessed using different methods, in various areas of human functioning. Kato's (2015) meta-analysis showed, for example, that flexible coping reduces circulatory system reactivity (heart rate and systolic blood pressure) and reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms. It was also shown that war veterans returning from Iraq who were assessed to have higher levels of psychological flexibility established closer and more lasting social relationships and committed fewer acts of physical aggression and victimization compared to veterans who had lower levels of it (Reddy et al., 2011). Other studies have shown that veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars with high psychological flexibility and greater social support were characterized by less frequent use of avoidant coping, lower levels of PTSD and depression (Elliott et al., 2015). Researchers Bryan, Ray-Sannerud, and Heron (2015) and Dutra and Sadeh (2018) also estimated that psychological flexibility protects against the development of PTSD symptoms and externalizing behaviors among veterans exposed to trauma. The results of other studies also indicate that people who have experienced more trauma have higher levels of psychological flexibility and posttraumatic growth (PTG) (Schubert et al., 2016; Kato, 2015).

Research on flexible coping conducted within developmental psychology has also revealed certain regularities: the level of flexible coping in adolescents was lower than in students and adults (Basińska, 2015; Cheng et al., 2014), which suggests that flexible coping is a disposition that can be developed thanks to experience gained with age and the ability to think logically, plan and make decisions, and take the perspective of others (Braun-Lewensohn et al., 2010; Grzankowska & Fabjanowicz, 2023). There have also been reports of links between flexible coping and the psychological orientation resulting from the cultural way of thinking (Triandis, 2001). Several studies have found positive correlations between flexible coping and horizontal individualism, horizontal collectivism, and vertical collectivism (Kruczek et al., 2021). Thus, it is an attitude of cooperation rather than competition and individualism that may involve making some efforts to monitor one’s own behaviour, which facilitates the development of flexible coping competences.

Research

In our research, we characterize psychological flexibility in terms of the competence to change behavior in order to effectively use both one's own resources and the external context, for broadly understood development, aimed at realizing the most important standards of regulation for the individual (needs, values, meanings) (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Senejko, 2019). We assume that this competence may, to a varying extent, contribute to the characteristics of both subjective and social dispositions and be present in the individual's coping strategies for currently experienced threats.

In order to obtain an answer to our research question: what role do the resources characterized by flexibility play in coping with threats related to the ongoing war in Ukraine among the surveyed Ukrainian citizens - we took into account identity styles and the developmental dimension of psychological defense, related to the two models briefly discussed below.

According to the first model, the function-action model of psychological defense MFCOP by Alicja Senejko (2005, 2010, 2019), psychological defense activated as a result of disruption of the most important standards of regulation, consists of two large groups of defenses (reactions to the experienced threat). Constructive, aimed at overcoming disruptions in the implementation of the regulatory standards (cf. task orientation, problem orientation) and non-constructive, aimed at minimizing the negative effects of their failure to implement (cf. emotion regulation orientation). According to the assumptions of MFCOP, for effective, flexible coping, the advantage of constructive defenses over non-constructive defenses is primarily important (developmental dimension of psychological defense) in order to enable the continuation of development taking place in the context of coping with the threat (Senejko, 2010, 2019). The developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD, in our opinion, corresponds to the above-mentioned concepts of flexible coping and in the presented research constitutes a resource of flexible coping.

In the second, Michael Berzonsky's model of identity styles (2005, 2011), psychological flexibility is associated with information processing processes involved in creating or changing identity. Berzonsky distinguishes 3 identity styles: informational, normative and diffuse-avoidant, characterized by varying degrees of flexible information processing. People with the informational identity style (IS) are self-reflective, open to new information and inclined, under the influence of feedback that is inconsistent with their own, to check and possibly modify aspects of their identity. In turn, individuals with the normative identity style (NS) adopt expectations, values and regulations from significant others and their main goal is to defend themselves against information that is inconsistent with their main values and beliefs. On the other hand, people with the diffuse-avoidant identity style (DS) are characterized by postponing addressing identity problems until later; their behavior will be situationally conditioned by the external context (Berzonsky & Papini, 2015).

As can be seen from the above descriptions, the most flexible resources in the area of shaping personal identity are possessed by people with an informational identity style, while the most rigid, inflexible ones are possessed by people with a normative identity style.

Let us add, however, that apart from differences related to the participation of flexible information processing in shaping individual identity styles, their bearers differ significantly in the relative participation of identity components defining their sense of identity: goals and values of a collective, social or personal nature (Berzonsky et al., 2003). Thus, the available research results show that among people with an Informational style IS, personal attributes of the Self (values, goals and beliefs assessed personally, concerning autonomy, self-development, etc.) dominate. In turn, among people with a Normative style NS, collective aspects of identity, relatively automatically adopted, dominate, which means that values such as family, religion or nationality will constitute their main motivational factors. For people with a Diffuse-avoidant style DS, however, social attributes of the Self (reputation, image, popularity) constitute the main motivational characteristics, which are, on the one hand, stable (because they invariably constitute the motive for their activity), and on the other hand, somewhat fleeting, because they depend on variable situational factors (Berzonsky & Papini, 2015).

n our research, we also take into account Posttraumatic growth PTG and Posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD, assuming that Posttraumatic growth is both a process and an effect of flexible coping, while Posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD is both a process and an effect of rigid, inflexible coping (Berzonsky & Papini, 2015; Kato, 2015; Bonanno, 2021; Senejko, 2019).

The basic research question is as follows: What is the role of Identity Styles and the Developmental dimension of psychological defense in coping with threats related to war trauma, in the form of Posttraumatic growth PTG and of Posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD?

In relation to the Developmental dimension of psychological defense, we formulated the hypothesis: H.1 In the situation of experiencing threats related to war trauma by the surveyed Ukrainian citizens, flexible coping resources in the form of the Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD mediate between the influence of Intensification of threats ITH on PTSD and PTG, reducing the level of PTSD and increasing the level of posttraumatic growth PTG.

Participants and procedure

Participants. The study included n=457 subjects; women n=350 (76.6%) and men n=107 (23.4%), aged 16 to 80 (M=24.12; SD=12.79). The study participants included Ukrainian citizens who remained in their homeland (n=189;37.7%), Ukrainian citizens who emigrated after the war broke out in February 2022 to: Germany (n=157;31.3%), Poland (n=85;17.0%) and Slovakia (n=70;14.0%). Of the 330 people who indicated their place of residence in Ukraine, 58% came from areas affected by fighting, and 42% from areas where fighting did not take place. Other characteristics of the study group are presented in

Table 1.

Procedure. The research was conducted between November 2022 and March 2024. Respondents were recruited through institutions that assisted refugees from Ukraine and through the snowball method. The response rate obtained was 75%. In Ukraine, the research was conducted online using the Forms platform.

The results presented in the article are based on a slightly smaller group of respondents, due to the fact that not all respondents completed the ISI-5 questionnaire diagnosing identity styles.

Measures

The following tools were used for the study:

The PCL-5 questionnaire (PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, PCL-5), as developed by Weathers et al. (2013), in the Polish adaptation by Ogińska-Bulik et al. (2018), was used to measure PTSD in terms of the total score (factor) and four symptoms of PTSD: intrusiveness, avoidance, symptoms of increased arousal and reactivity, and negative changes in the cognitive and/or emotional sphere. The total score is the sum of points from the respondent’s answers on a 5-point scale from 0 to 4, from all 20 items of the full PCL-5 scale. In our study Cronbach’s α for the PTSD total score was .95. We used for our study Overall post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD (total score of PTSD).

The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996), in the Polish adaptation by Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński (2010), was used to identify positive changes in the psychosocial functioning of the respondent after the experienced trauma. The method consists of 21 items to which the respondent answers using a 6-point scale from 0 to 5. PTG is measured in the Polish adaptation of this method based on the score of the overall index and 4 aspects of PTG (rather than 5 as in the original version): changes in self-perception, changes in relationships with others, greater appreciation of life and changes in the spiritual sphere (Ogińska-Bulik & Juczyński, 2010). In our study Cronbach’s α = .91 (total score). We used for our total score of PTG.

The Psycho-Social and Psychic Defenses Questionnaire (PSPDQ1-R), developed by Senejko (2019). The PSPDQ1-R consists of 62 statements about threats and psychological defenses. The respondent provides answers on a 4-point scale, from 0 to 3. The PSPDQ1-R method diagnoses 18 categories of detailed defensive actions, grouped into 2 main categories: Constructive defenses CD(task-oriented) and Non-Constructive defenses N-CD(oriented to regulate emotions). In addition, it estimates 9 categories of threats from the respondent’s life areas. These can be grouped, by summing the scores obtained for 9 categories of threats - into 1 factor - Intensification of threats ITH. In our study, Cronbach’s α for Intensification of threats ITH = .85; for Non-Constructive defenses N-CD α = .85; for Constructive defenses CD α = .70. The PSPDQ1-R was also used to estimate the factor of Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD (by subtracting the scores obtained for nonconstructive defenses from the scores obtained for constructive ones).

ISI-5 Revised Identity Style Inventory, developed by Berzonsky et al., 2013), in the Polish adaptation by Senejko and Łoś (2015). In its full version, the method examines 3 identity styles: informational, normative, and diffuse-avoidant and commitment. It consists of 48 items. The respondent provides answers on a 5-point scale, from 1 (definitely does not apply to me) to 5 (definitely describes me). We used ISI-5/R to assess 3 identity styles. In our study, Cronbach’s for the Informational style IS, Normative style NS, and Diffuse-avoidant style DS were, respectively: α = 0.78; α = 0.77; α = 0.80.

Results

Descriptive statistics and tests of normal distribution. In the first step, we performed descriptive statistics for the estimated variables (

Table 2). Since tests checking the distribution of variables indicate that in the vast majority of cases the distribution of variables deviates from normal, we used nonparametric tests in further analyses.

Relationships between variables. The next step of statistical analysis was the analysis of relationships between variables. Spearman's rho correlation analysis (

Table 3), revealed that the Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD variable correlated positively with weak or moderate intensity, with Informational style IS, and also negatively, weakly or moderately with: intensity of Normative style NS, with Diffuse-avoidant style DS and with overall Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD. In the case of PTSD, moderate positive relationships were also noted with Non-constructive defenses N-CD, with Normative style NS, with Diffuse-avoidant style DS, and with Informational style IS. On the other hand, overall Posttraumatic growth PTG correlated weakly negatively with Informational style IS and positively, weakly or moderately with: Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD, with intensity of Normative style NS and with Diffuse-avoidant style DS. In turn, the variable Intensification of threats ITH correlated positively, weakly, or moderately with Non-constructive defences N-CD, with Constructive defences CD, with Informational style IS, and with PTSD, while ITH correlated negatively with Diffuse-avoidant style DS.

Table 3.

Correlations of indicators of psychological defenses, identity styles, posttraumatic stress, posttraumatic growth and threat intensity (N = 318 - 457).

Table 3.

Correlations of indicators of psychological defenses, identity styles, posttraumatic stress, posttraumatic growth and threat intensity (N = 318 - 457).

| |

CD |

NCD |

DDPD |

IS |

NS |

DS |

PTSD |

PTG |

| Constructive defenses CD |

-- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Constructive defenses N-CD |

0,334** |

-- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dev. dimension of psych.defense DDPD |

0,528** |

-0,567** |

-- |

|

|

|

|

|

| Informational style IS |

O,338** |

0,016 |

0,282** |

-- |

|

|

|

|

| Normative style NS |

-0,223** |

-0,096 |

-0,123* |

0,003 |

-- |

|

|

|

| Diffuse- avoidant style DS |

-0,312** |

0,012 |

-0,294** |

-0,239** |

0,523** |

-- |

|

|

| Overall Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD |

0,012 |

0,366** |

-0,311** |

0,079 |

0,321** |

0,366** |

-- |

|

| Overall Posttraumatic growth PTG |

0,073 |

-0,040 |

0,054 |

-0,149* |

0,314** |

0,253** |

0,241** |

-- |

| Intensification of threats ITH |

0,273** |

0,409** |

-0,090 |

0,152** |

-0,106 |

-0,197** |

0,117* |

-0,012 |

Main predictors of PTSD and PTG.

Regression analyses. We also checked whether the Informational style IS, Normative style NS, Diffuse- avoidant style DS, Intensification of threats ITH, Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD, Gender G and Age A could predict the Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD (

Table 5).

It turned out that Informational style IS (β = 0.20; p = 0.001) and Diffuse- avoidant style DS (β = 0.32; p < 0.001) are positive predictors of PTSD, the increase of which allows to expect an increase in the severity of the Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder. A significant negative predictor of PTSD was the Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD (β = -0.30; p < 0.001). The remaining factors were not significant predictors.

The regression model fitted the data well [F(7, 261) = 14.61; p < 0.001] and explained 26.2% of the variability.

Table 4.

Predictors Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD (N = 269).

Table 4.

Predictors Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD (N = 269).

| |

B (SE) |

β |

| Constant value |

-16,00 (9,33) |

--- |

| Informational style IS |

0,66 (0,19) |

0,20** |

| Normative style NS |

0,33 (0,18) |

0,12 |

| Diffuse - avoidant style DS |

0,78 (0,16) |

0,32** |

| Intensification of threats ITH |

0,20 (0,12) |

0,10 |

| Dev. dimension of psychological defense DDPD |

-11,62 (2,40) |

-0,30** |

| Gender G |

-0,24 (2,07) |

-0,01 |

| Age A |

0,04 (0,08) |

0,03 |

| F |

14,61** |

|

| R2 |

0,262 |

|

An analogous multivariate regression model was calculated for the Overall level of posttraumatic growth PTG (

Table 5). It showed that statistically significant predictors in the case of PTG are: Informational style IS (β = -0.13; p = 0.046), Normative style NS (β = 0.30; p < 0.001) and Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD (β = 0.18; p = 0.006). Based on the increase in Informational style IS, a decrease in the Overall level of Post-traumatic growth PTG can be expected, while its increase can be predicted on the basis of Normative style NS of identity and Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD.

The described model met the goodness of fit criterion [F(7, 256) = 7.95; p < 0.001] and explained 15.6% of the variance in the Overall level of Post-traumatic growth PTG.

Table 5.

Predictors Overall level of Post-traumatic growth PTG (N = 264).

Table 5.

Predictors Overall level of Post-traumatic growth PTG (N = 264).

| |

B (SE) |

β |

| Constant value |

56,13 (9,60) |

---** |

| Informational style IS |

-0,39 (0,20) |

-0,13* |

| Normative style NS |

0,81 (0,18) |

0,30** |

| Diffuse-avoidant style DS |

0,32 (0,17) |

0,14 |

| Intensification of threats ITH |

0,23 (0,12) |

0,12 |

| Dev. dimension of psychological defenseDDPD |

6,89 (2,47) |

0,18** |

| Gender G |

-2,31 (2,10) |

-0,07 |

| Age A |

-0,07 (0,08) |

-0,06 |

| F |

7,95** |

|

| R2 |

0,156 |

|

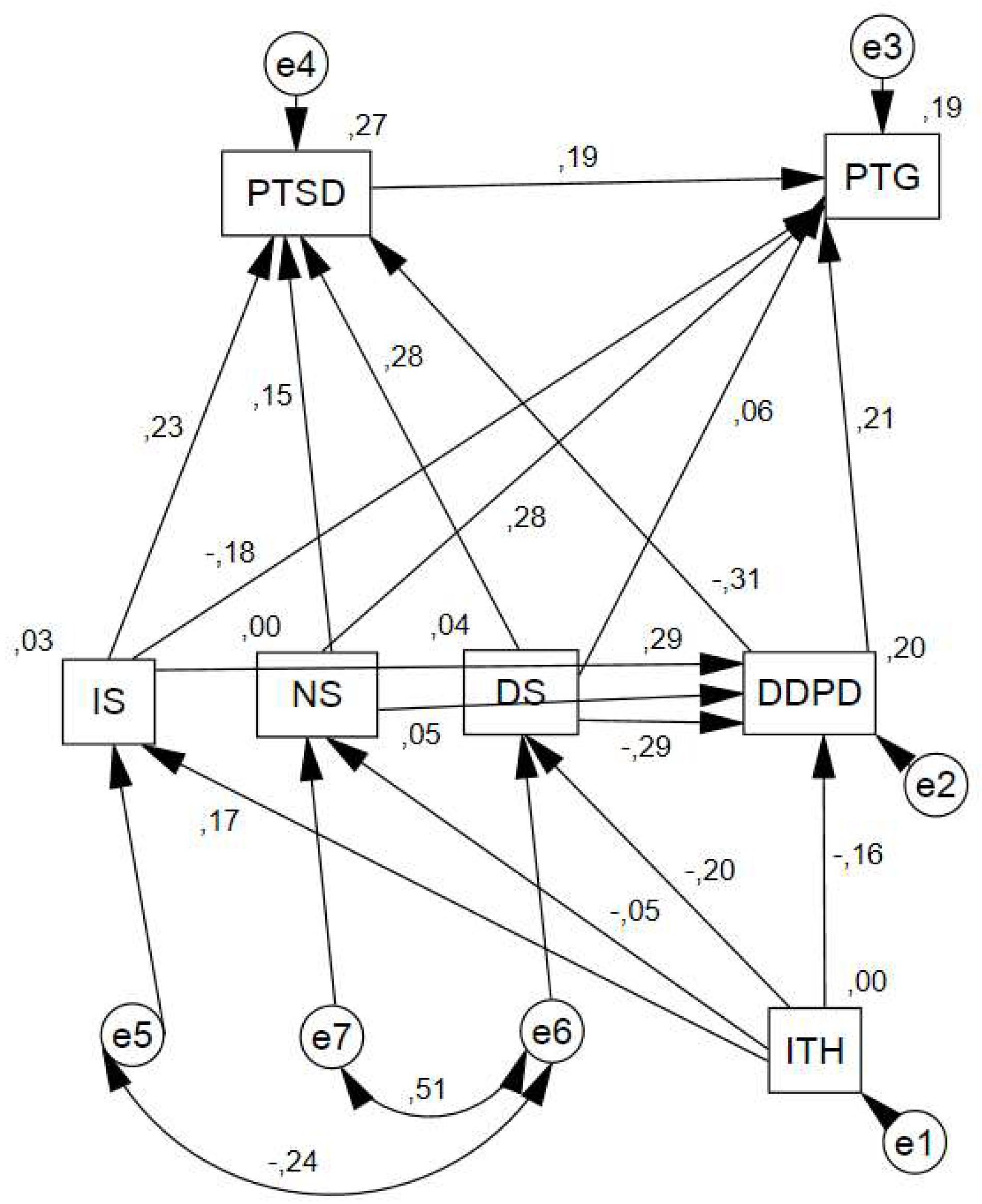

Structural modeling. We also conducted structural equation modeling (SEM) to test our hypothesis H1. The influence of Intensification of threats (ITH) on the Overall level of posttraumatic growth (PTG) and Overall level of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was considered, with the mediation of Developmental dimension of psychological defense (DDPD), Informational style (IS), Normative style (NS), Diffuse-avoidant style (DS). The analysis was performed on N = 261 cases without missing data. The algorithm based on the parametric maximum likelihood (ML) method was used to calculate and estimate the coefficients in SPSS AMOS 26.0. The model fit was assessed using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Jöreskog and Sörbom goodness of fit index GFI, the adjusted Jöreskog and Sörbom goodness of fit index AGFI, the relative fit index CFI, and the Tucker-Lewis coefficient TLI. The model fit to the data was as follows: RMSEA = 0.059 (0.000-0.132); GFI = 0.994; AGFI = 0.942; TLI = 0.936; CFI = 0.991.

The conducted SEM modeling (Table 6,

Figure 1) showed a direct effect of Intensification of threats ITH – negative in the case of Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD and Diffuse-avoidant style of identity DS, as well as a positive effect in relation to Informational style IS.

The increase in IS directly influenced the increase in Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD and Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD and the decrease in the intensity of Overall level of Post-traumatic growth PTG.

In turn, Diffuse-avoidant style DS directly and negatively influenced the Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD and positively influenced the Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD.

It was also noted that the increase in the intensity of Normative style NS influenced the increase in Overall level of Post-traumatic growth PTG and Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD.

The Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD influenced the decrease in Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD and the increase in Overall level of Post-traumatic growth PTG.

It has also been observed that an increase in PTSD affects the increase in the severity of PTG.

In terms of mediating effects, a positive effect of Intensification of threats ITH on the Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD was observed, to which the main contributors were the identity styles IS (strengthening) and DS. (weakening).

The remaining direct and indirect effects were either statistically insignificant or negligible due to very weak path coefficients.

Table 7.

Impact of Intensification of threats (ITH) on the overall level of Post-traumatic growth (PTG), with the mediating contribution of Developmental dimension of psychological defense (DDPD), Informative style (IS), Normative style (NS), Diffuse-avoidant style ( DS) and Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (N = 261).

Table 7.

Impact of Intensification of threats (ITH) on the overall level of Post-traumatic growth (PTG), with the mediating contribution of Developmental dimension of psychological defense (DDPD), Informative style (IS), Normative style (NS), Diffuse-avoidant style ( DS) and Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (N = 261).

| Path |

B |

beta |

p |

| DS<---ITH |

-0,171 |

-0,197 |

0,001 |

| NS<---ITH |

-0,038 |

-0,051 |

0,413 |

| IS<---ITH |

0,110 |

0,172 |

0,005 |

| DDPD<---ITH |

-0,008 |

-0,161 |

0,005 |

| DDPD<---IS |

0,024 |

0,292 |

0,000 |

| DDPD<---DS |

-0,018 |

-0,294 |

0,000 |

| DDPD<---NS |

0,004 |

0,054 |

0,408 |

| PTSD<---DDPD |

-12,242 |

-0,310 |

0,000 |

| PTSD<---IS |

0,761 |

0,234 |

0,000 |

| PTSD<---NS |

0,412 |

0,147 |

0,019 |

| PTSD<---DS |

0,681 |

0,283 |

0,000 |

| PTG<---DDPD |

7,816 |

0,205 |

0,002 |

| PTG<---IS |

-0,551 |

-0,176 |

0,005 |

| PTG<---DS |

0,136 |

0,059 |

0,418 |

| PTG<---NS |

0,767 |

0,284 |

0,000 |

| PTG<---PTSD |

0,184 |

0,191 |

0,004 |

| e7<-->e6 |

21,236 |

0,512 |

0,000 |

| e5<-->e6 |

-8,512 |

-0,242 |

0,000 |

| DDPD<<---ITH |

0,006 |

0,105 |

0,001 |

| PTSD<<---ITH |

-0,012 |

-0,006 |

0,830 |

| PTSD<<---IS |

-0,294 |

-0,091 |

0,001 |

| PTSD<<---NS |

-0,047 |

-0,017 |

0,450 |

| PTSD<<---DS |

0,219 |

0,091 |

0,001 |

| PTG<<---ITH |

-0,138 |

-0,069 |

0,012 |

| PTG<<---IS |

0,274 |

0,087 |

0,005 |

| PTG<<---NS |

0,097 |

0,036 |

0,036 |

| PTG<<---DS |

0,026 |

0,011 |

0,742 |

| PTG<<---DDPD |

-2,252 |

-0,059 |

0,015 |

Discussion

Our research included people experiencing threats related to the ongoing war in Ukraine, both the group of Refugees, in which women predominated, and the group of respondents remaining in Ukraine. The research questions in this work, and especially the hypothesis, are formulated intuitively, because the role of identity styles and the developmental dimension of psychological defense in coping in the form of PTG and of PTSD - have not been studied so far in a similar combination as we do.

The results regarding the answers to the first two questions show that the main positive predictors of PTSD were Informational style IS and Diffuse-avoidant style DS, the increase of which allows us to expect an increase in the severity of the Overall level of Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD. On the other hand, the Developmental dimension of psychological defense turned out to be a significant negative predictor of PTSD, the increase of which allows us to expect a decrease in the severity of PTSD. Additionally, the picture is complemented by positive correlations between PTSD and the Normative style of identity NS and Non-constructive defenses N-CD.

The question is, what do such different identity styles, described by Berzonsky, as Informational IS and Diffuse-avoidant DS have in common? One secures functioning in the world based on mature, verified, rational decisions, and the other rather the opposite, situational. One mainly involves rational processing (although it can also use intuitive processing!), DS mainly involves intuitive processing, with possible sporadic, situational participation of rational processing. If we also include the Normative Style in the analysis, a factor correlating with PTSD, it only engages intuitive processing (Cheek & Briggs, 1982; Berzonsky & Papini, 2015). In other words, what is common between these identity styles is the presence of intuitive processing. Intuitive processing, according to the cognitive experiential self-theory (Epstein, 1990), is a process of concrete, emotionally charged information in a relatively automatic, mentally effortless manner. Intuitive processing is relatively more efficient and economical than rational processing, but also relatively more prone to cognitive bias and subjective distortion (Epstein, 1990). It can therefore be assumed that in the circumstances of the ongoing war and the constant sense of uncertainty and threat, when it is often necessary to act quickly and without thinking, in some of the subjects the intuitive system will be activated and along with it habitual ways of coping, often originating from childhood and perhaps adaptive in childhood but not in the current situation of threats related to the ongoing war, hence the increase in PTSD.

Identity styles that trigger Intuitive processing in relation to information important for identity formation may be predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD, fixating on threats that constitute war trauma. The essence of PTSD is being stuck in the eye of the hurricane of trauma, the lack of possibility and/or ability to break free from the influence of the traumatic event (Davidson & Foa, 2015). In order to break free, one must engage a rational view of the situation, rational processing that consists of flexible coping, and not Intuitive processing with a repertoire of habitual reactions that usually contribute to rigidity of behavior (Epstein, 1990; Berzonsky & Papini, 2015). It is also not surprising that the negative predictor of PTSD in our studies was the developmental dimension of defense, i.e. a set of activities fulfilling defensive functions, with a predominance of those oriented not towards emotion regulation, but towards the problem, the task, ensuring flexible coping and occurring, one can presume, with a relatively greater share of rational processing than intuitive processing (Senejko, 2019, 2020).

In turn, the predictors of post-traumatic growth in PTG were: Informational style IS (negative predictor), Normative style NS and Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD (positive predictors). Based on the increase in Informational style IS, a decrease in the Overall level of Post-traumatic growth in PTG can be expected, while its increase can be predicted based on the Normative style of identity NS and Developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD. Additionally, the picture is complemented by positive correlations between PTG and the Diffuse-avoidant style DS and PTSD. We associate such a system of dependencies in the scope of identity styles and post-traumatic growth in PTG not with the way of processing information involved in shaping identity, as in the case of PTSD, but with the motivational characteristics constituting each of the mentioned styles: the predominance of personal motives in the case of the informational style IS and social and/or collective motives, associated with the Normative style of identity NS and Diffuse-avoidant DS.

Similarly to some researchers (Hobfoll et al., 2007; Dunkel, 2002), to explain our research results, we can take into account the Terror Management Theory (Pyszczynski et al., 1999), according to which threats related to war trauma can activate a strong fear of death. In turn, the fear of death contributes to the intensification of the need for affiliation as protection against this fear (Łukaszewski & Boguszewska, 2008). The world begins to divide in the eyes of people affected by war trauma into two groups: Us and Them. The more collective and/or social motives characterize an individual (family, nation, social acceptance, popularity, etc.), the more susceptible they may be to the activation of these mechanisms in the context of the ongoing war. In our opinion, this analysis concerns primarily people with the Normative SN identity style and (to a lesser extent) with the Diffuse-Avoidant SD. On the other hand, experiencing threats related to the circumstances of war, and with it, an uncertain, unpredictable future, may weaken even in previously very resourceful people, their sense of agency (Cieślak & Wojciszke, 2014). Therefore, perhaps people with individual motivation, focused more on autonomous goals, on self-determination and agency, such as those with the Informational SI identity style - may have more difficult access to posttraumatic development, compared to people with collective or social motivation (Kruczek et al., 2021).

But let us consider what kind of development? According to the characterization of posttraumatic growth proposed by Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004), positive posttraumatic changes are mainly in the form of changes in beliefs about relationships. And the results of some studies show, these positive changes mainly concern relationships with Our Own, and not also with Others, towards whom hostility may even intensify (cf. studies involving Palestinians and Jews: Hobfoll et al., 2007).

Structural modeling confirms the relationships described above, adding to this picture an interesting role of the developmental dimension of psychological defense DDPD and the influence of identity styles: Informational IS (strengthening) and Diffuse-avoidant DS (weakening) on DDPD. As it turned out, DDPD not only directly affects PTG and PTSD, but also indirectly affects posttraumatic growth, but by reducing the level of PTSD, which in turn strengthens PTG. Our hypothesis was therefore confirmed in half. The developmental dimension of psychological defense, with a predominance of constructive, task-oriented, problem-oriented defensive activities compared to non-constructive, avoidance-oriented ones, constitutes cognitive-behavioral resources of an individual activated all the more strongly the more a person experiences threats (positive links with ITH) (cf. Schubert et al., 2016; Yunus et al., 2019). It is a type of cognitive-behavioral mobilization of flexible resources of organisms, which, as it turns out, are able to both reduce the intensity of PTSD and participate in positive posttraumatic changes directly and indirectly (Senejko, 2019). Interestingly, these resources can be strengthened by the participation of rational behavior regulation associated with the Information style of IS identity, or weakened by the tendency to avoid solving problems, characteristic of the Diffuse-avoidant style DS. Positive associations between PTSD and PTG, which we did not expect, are also not surprising and are noted in some studies (Solomon & Dekel, 2007; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004; Janoff-Bulman, 2004). It should be emphasized, however, that they are usually not high and concern lower or medium severity of PTSD, because in the case of high severity of PTSD, mental disorganization is too high to simultaneously make positive changes in the area of beliefs and social relationships, which is the case with PTG (Joseph et al., 2004; van der Kolk, 2018).

Conclusion

Our research fits into existing reports on the response to threats experienced in the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine by Ukrainian citizens (Kang et al., 2023; Johnson et al., 2022; Levin et al., 2023; Karstoft et al., 2024) and residents of the border with Ukraine (Kaniasty et al., 2024; Szepietowska, 2023), complementing the rich repertoire of detected relationships. They also have their limitations: they include a relatively small number of respondents and difficulties in reaching respondents from Ukraine, especially men. Also, when interpreting the obtained results of our research, the profile of the respondents should be taken into account, in which there was a clear predominance of women and young people (refugees) and the extended duration of the research. Nevertheless, it was possible to show that resources securing a reflective attitude towards one's own behavior (DDPD, IS ), are associated with coping flexibility (Cheng et al., 2014; Kato, 2020; Bonanno, 2021). We also revealed, taking into account the identity styles of IS NS, DS, that the flexibility of coping with war trauma is also influenced by the motivational aspect, especially collective and social motives. We consider the distinction of these two forms of regulation: cognitive (rational/intuitive) and motivational - in coping with threats related to war trauma to be important to take into account when developing therapeutic interactions with refugees and other people struggling with strong threats. Our research is therefore another small step in the penetration of factors influencing flexible coping.

References

- Basińska, M. A. (ed.) (2015). Elastyczne radzenie sobie ze stresem w zdrowiu i w chorobie. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego.

- Berzonsky, M. D. (2005). Identity processing style and self-definition: effects of a priming manipulation. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 36(3),137-143.

- Berzonsky, M. D. (2011). A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx & V. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (Vol. 1, pp. 55–76). Springer.

- Berzonsky, M. D., Macek, P., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2003). Interrelationships among identity process, content, and structure: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18(2), 112–130. 10.1177/0743558402250344 Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., Smits, I., Papini, D. R., & Goossens, L. (2013). Development and validation of the revised Identity Style Inventory (ISI-5): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Psychological Assessment, 25(3), 893–904. [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, M. D., & Papini, D. R. (2015). Cognitive reasoning, identity components, and identity processing styles. Identity, 15(1), 74–88. [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2021). The end of trauma: How the new science of resilience is changing how we think about PTSD (1st ed.). Basic Books.

- Bonanno, G. A., & Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on psychological science, 8(6), 591–612. [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O., Sagy, S., & Roth, G. (2010). Coping strategies among adolescents: Israeli Jews and Arabs facing missile attacks. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 23(1), 35-51. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C. J., Ray-Sannerud, B., & Heron, E. A. (2015). Psychological flexibility as a dimension of resilience for posttraumatic stress, depression, and risk for suicidal ideation among Air Force personnel. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 4(4), 263–268. [CrossRef]

- Cheek, J. M., & Briggs, S. R. (1982). Self-consciousness and aspects of identity. Journal of Research in Personality, 16(4), 401–408. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., Lau, H. P. B., & Chan, M. P. S. (2014). Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1582–1607. [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, M., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Orientacja sprawcza i wspólnotowa a wybrane aspekty funkcjonowania zdrowotnego i społecznego. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

- Davidson, J. R. T., & Foa, E. B. (2015). Posttraumatic stress disorder: DSM-5 and beyond. Psychological Medicine, 45(3), 337-347.

- Dunkel C. S. (2002). Terror Management Theory and Identity: The Effect of the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks on Anxiety and Identity Change. Identity, 2(4), 287-301. [CrossRef]

- Dutra, S. J., & Sadeh, N. (2018). Psychological flexibility mitigates effects of PTSD symptoms and negative urgency on aggressive behavior in trauma-exposed veterans. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(4), 315-323. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, T. R., Hsiao, Y. Y., Kimbrel, N. A., Meyer, E. C., DeBeer, B. B., Gulliver, S. B., ... & Morissette, S. B. (2015). Resilience, traumatic brain injury, depression, and posttraumatic stress among Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans. Rehabilitation Psychology, 60(3), 263–276. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S. (1990). Cognitive-experiential theory. In L. Previn (Ed.), Handbook of personality theory and research (pp. 165–192). Guilford Press.

- Grzankowska, I. A., & Fabjanowicz,A. (2023). Personality organisation and flexibility in coping with stress in the group of alcohol-dependent individuals/Organizacja osobowości a elastyczność w radzeniu sobie ze stresem w grupie osób uzależnionych od alkoholu. Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology/Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna, 23(4), 268–279. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Hall, B. J., Canetti-Nisim, D., Johnson, R. J. & Palmieri, P. (2007). Refining our understanding of traumatic growth in the face of terrorism: Moving from meaning cognitions to doing what is meaningful. Applied Psychology, 56(3), 345-366. [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Three explanatory models. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 30–34.

- Johnson, R. J., Antonaccio, O., Botchkovar, E., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2022). War trauma and PTSD in Ukraine’s civilian population: comparing urban-dwelling to internally displaced persons. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57, 1807–1816. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S., Linley, P. A., & Harris, G. J. (2004). Understanding positive change following trauma and adversity: Structural clarification. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 10(1), 83–96. [CrossRef]

- Kaluza, G. (2000). Changing unbalanced coping profiles: A prospective controlled intervention trial in worksite health promotion. Psychology & Health, 15(3), 423– 433. [CrossRef]

- Kang, T. S., Goodwin, R., Hamama-Raz, Y., Leshem, E., & Ben-Ezra, M. (2023). Disability and posttraumatic stress symptoms in the Ukrainian General Population during the 2022 Russian Invasion. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 32, e21, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, K., Baran, M., Urbańska, M., Boczkowska, M., & Hamer, K. (2024). Sense of danger, sense of country's mastery, and sense of personal mastery as concomitants of psychological distress and subjective well-being in a sample of Poles following Russia's invasion of Ukraine: Prospective analyses. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 16(3), 967-985. [CrossRef]

- Karstoft, K. I, Korchakova, N., Pedersen, A. A., Koushede, V., Power, S. A., Morton, T., Thøgersen, M. H. (2024, February 22). Displaced Ukrainians in Denmark II. Results From DARECO (The Danish Refugee Cohort). University of Copenhagen Department of Psychology. https://psychology.ku.dk/pdf/ukraine_report_ll.pdf.

- Kato, T. (2015). Frequently used coping scales: a meta-analysis. Stress & Health, 31(4),.

- 315–323. [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. (2020). Examination of the Coping Flexibility Hypothesis Using the Coping Flexibility Scale-Revised. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 561731. [CrossRef]

- Kruczek, A., Grzankowska, I., & Basińska, M. A. (2021). The role of cultural psychological orientations for flexibility in coping with stress in Polish adolescents./Znaczenie kulturowych orientacji psychologicznych dla elastyczności w radzeniu sobie ze stresem polskiej młodzieży. Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology/Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna, 21(2), 83–94. [CrossRef]

- Levin, Y., Ben-Ezra, M., Hamama-Raz, Y., Maercker, A., Goodwin, R. Leshem, E., & Bachem, R. (2023). The Ukraine–Russia War: A Symptoms Network of Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder During Continuous Traumatic Stress. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(7), 1110-1118. [CrossRef]

- Łukaszewski, W., & Boguszewska, J. (2008). Defense strategies against existential fear/Strategie obrony przed lękiem egzystencjalnym. Science/Nauka, 4, 23-34.

- Ogińska-Bulik, N., & Juczyński, Z. (2010). Posttraumatic growth – characteristic and measurement/Rozwój potraumatyczny – charakterystyka i pomiar. Psychiatria, 7(4), 129–142.

- Ogińska-Bulik, N., Juczyński, Z., Lis-Turlejska, M., & Merecz-Kot, D. (2018). Polish adaptation of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 – PCL-5. Preliminary report/Polska adaptacja PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 - PCL-5. Doniesienie wstępne. Przegląd Psychologiczny, 61, 281–285.

- Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (1999). A Dual-Process Model of Defense Against Conscious and Unconscious Death-Related Thoughts: An Extension of Terror Management Theory. Psychological Review, 106(4), 835-845.

- Reddy, M. K., Meis, L. A., Erbes, C. R., Polusny, M. A., & Compton, J. S. (2011). Associations among experiential avoidance, couple adjustment, and interpersonal aggression in returning Iraqi war veterans and their partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 515–520. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M., McGlinchey, E., Bonanno, G. A., Spikol, E. & Armour, C. (2022). A path to post-trauma resilience: a mediation model of the flexibility sequence. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2112823. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C. F., Schmidt, U., & Rosner, R. (2016). Posttraumatic growth in populations with posttraumatic stress disorder—A systematic review on growth-related psychological constructs and biological variables. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 23(6), 469–486. [CrossRef]

- Senejko, A. (2005) Psychological defense in adolescents and adults. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 3(36), 163-174.

- Senejko, A. (2010). Obrona psychologiczna jako narzędzie rozwoju. Na przykładzie adolescencji. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Senejko, A. (2019). Do we deal with trauma in stages? A perspective of the function-action model of psychological defense/Czy radzimy sobie z traumą etapowo? Perspektywa modelu funkcjonalno-czynnościowego obrony psychicznej. In A. Senejko & M. Żurko (Eds.), Prevention of trauma: Practice and research/Profilaktyka traumy: praktyka i badania, (pp. 24–46). Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls.

- Senejko A. (2020). Doświadczenie traumy: wybrane czynniki chroniące i czynniki ryzyka. In A. Senejko & A. Czapiga (Eds.). Oswojenie traumy: przegląd zagadnień, (pp. 23-58). Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls.

- Senejko, A., & Łoś, Z. (2015). The characteristics of th Polish adaptaions of Michael Berzonsky and co-authors’ Identity Style Inwentory (ISI-5)/Właściwości polskiej adaptacji Inwentarza Stylów Tożsamości (ISI-5) Michaela Berzonsky'ego i współautorów. Psychologia Rozwojowa, 4(20), 91-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.4467/20843879PR.15.024.4467.

- Solomon, Z., & Dekel, R. (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among Israeli ex-POWs. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(3), 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Szepietowska, E. M. (2023). The war in Ukraine and the dynamics of PTSD and depression in Poles aged 50+/Wojna w Ukrainie a dynamika PTSD i depresji u Polaków w wieku 50+. Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 23(3), p. 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (2018). Strach ucieleśniony Mózg, umysł i ciało w terapii traumy. Wydawnictwo Czarna Owca.

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Retrieved from National Center for PTSD.

- Williams, N. L. (2002). The cognitive interactional model of appraisal and coping: Implications for anxiety and depression. George Mason University.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9, 455–472. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G., (2004). “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. [CrossRef]

- Yunus, W. M. A., Musiat, P., & Brown, J. S. (2019). Evaluating the feasibility of an innovative self-confidence webinar intervention for depression in the workplace: a proof-of-concept study. JMIR mental health, 6(4), e11401. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).