Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biopolymers and Applications

2.1. Polymer Materials

2.2. Biopolymer Materials

2.3. Commercial Polymers vs Biopolymers

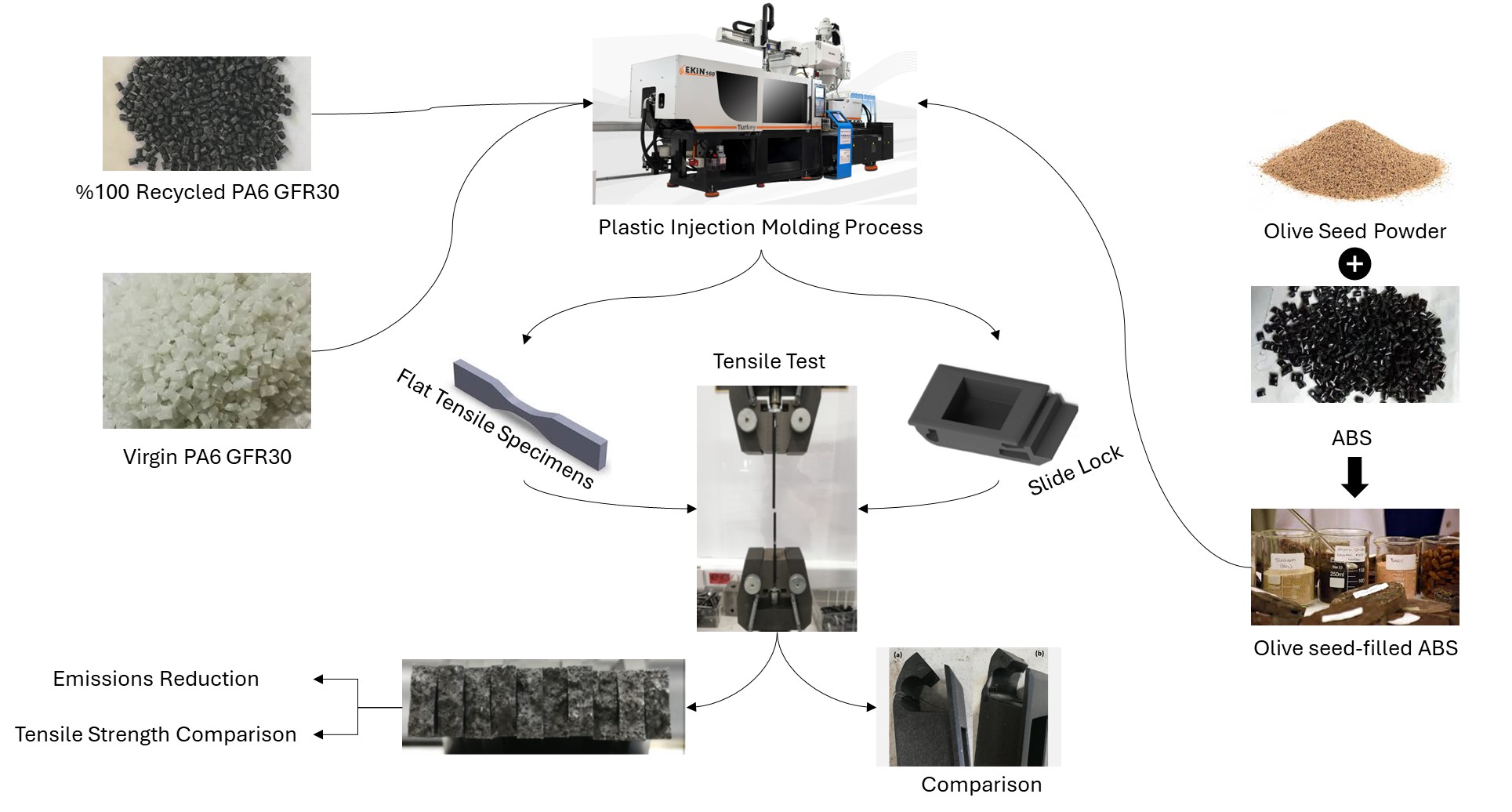

3. Experimental Studies

4. Results

- 1.

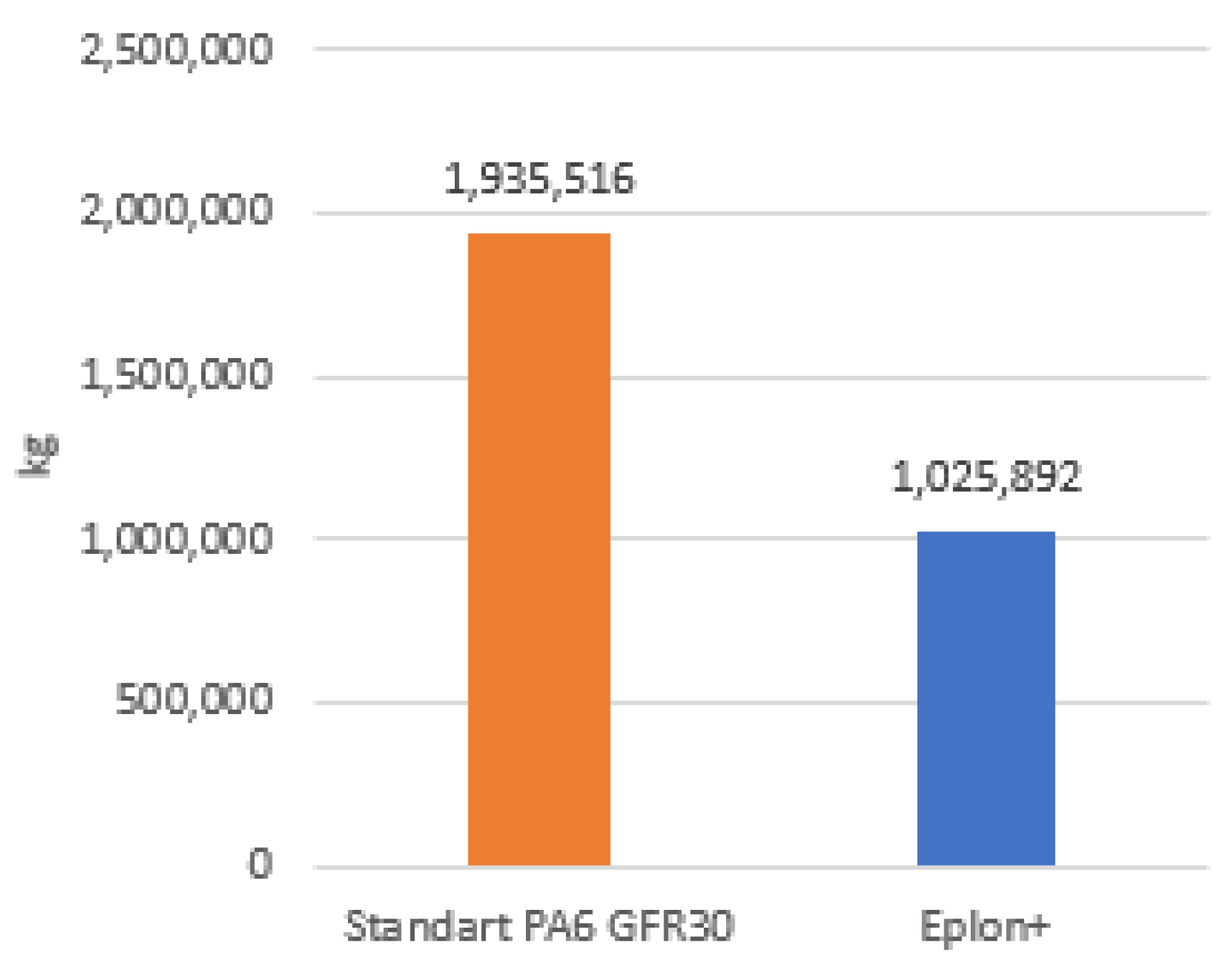

- The use of recycled polymer raw materials for the sustainable production of PA6 GFR30 has been studied. As a result:

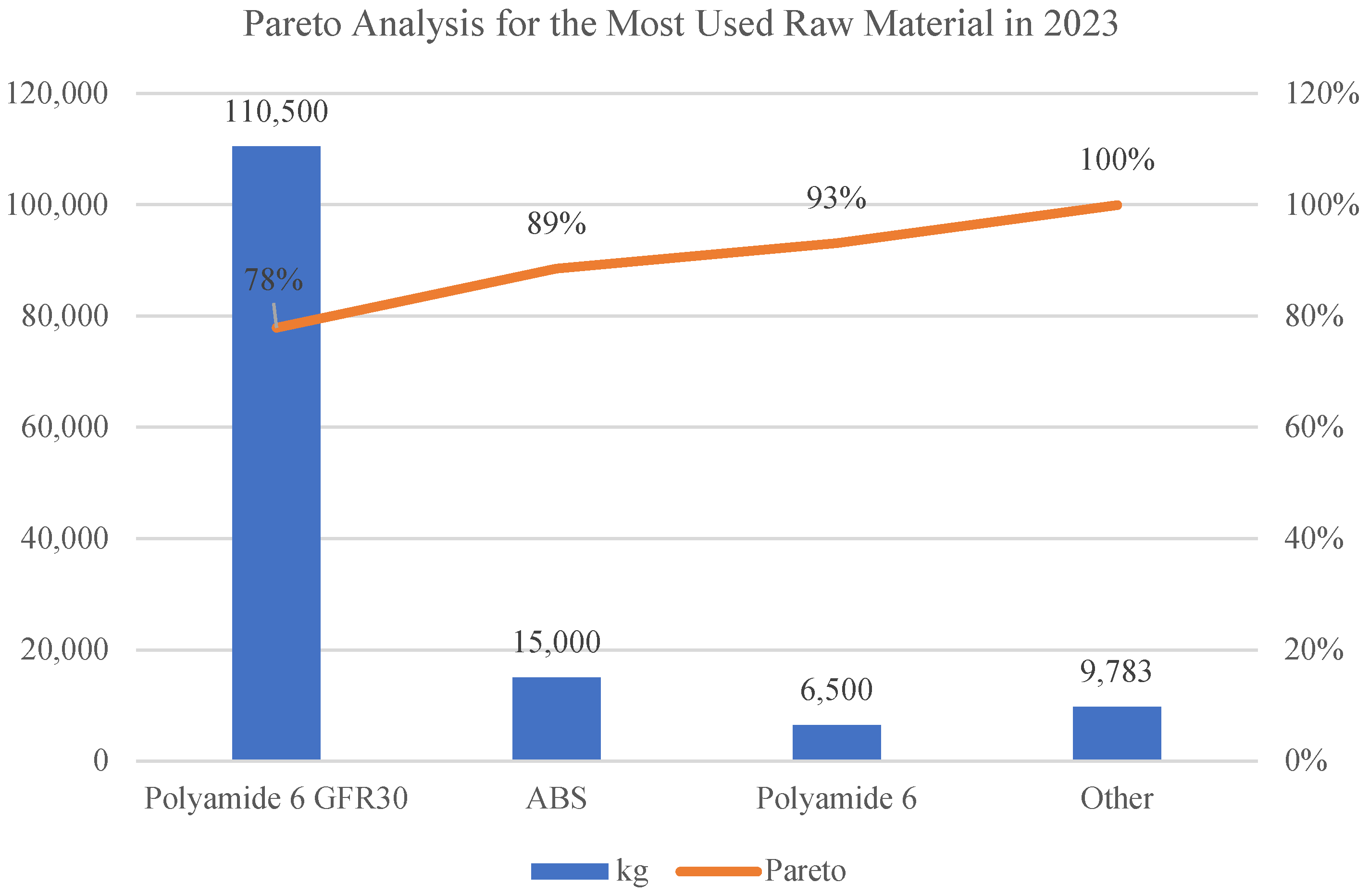

- Considering the consumption in 2023, it was observed that approximately 690 tons of carbon footprint reduction could be achieved.

- When evaluated in terms of mechanical strength, it was determined that the tensile strength of the current recipe and raw materials from the current supplier was achieved within the range of 88-99%.

- Considering the consumption in 2023, it was calculated that approximately 909 tons of water footprint reduction could be achieved.

- 2.

- In the study with 10% olive seed reinforced ABS, it was determined that the tensile strength of pure ABS was achieved at a rate of 96.45 In the study conducted with olive seed-filled (10%) ABS, it was found that the tensile strength of the pure ABS was achieved within the range of 96.45%.

- Thanks to the lower process parameters, it was predicted that energy consumption, or in other words, the carbon footprint, would be lower.

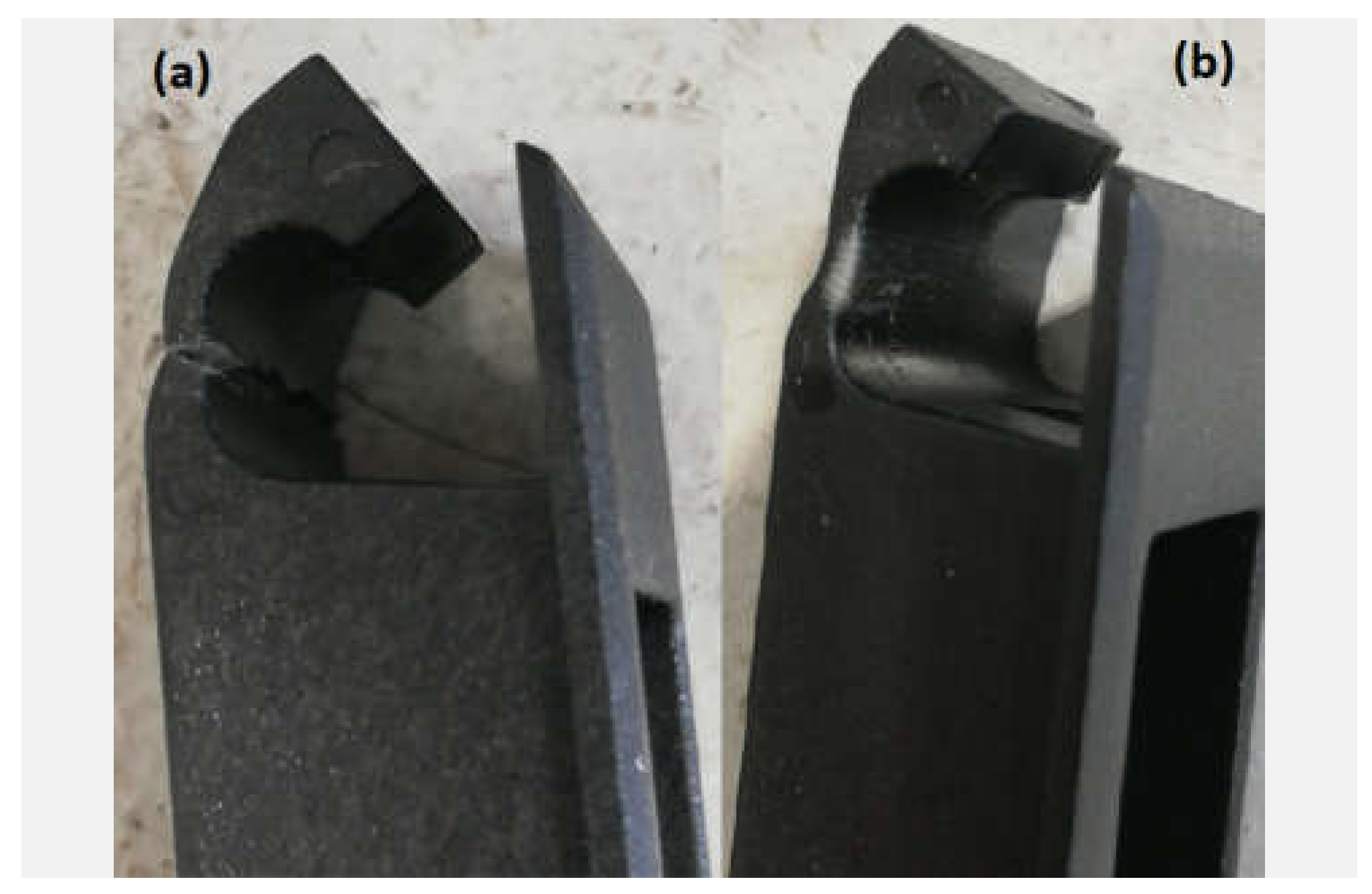

- It was determined that the olive seed additive in the products caused a decrease in tensile strength due to burning of the olive seed additive at high process temperatures. Additionally, it was observed that the products broke without deformation due to the lower elongation at break of the additive.

- It was determined that the olive seed additive in the products caused a decrease in tensile strength due to the burning of the olive seed additive at high process temperatures. Additionally, it was observed that the products broke without deformation due to the lower elongation at break of the additive.

References

- Wankhade, V. Animal-derived biopolymers in food and biomedical technology. Biopolymer-Based Formulations: Biomedical and Food Applications 2020, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, M.C.; Jony, B.; Nandy, P.K.; Chowdhury, R.A.; Halder, S.; Kumar, D.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hassan, M.; Ahsan, M.A.; Hoque, M.E.; et al. Recent Advancement of Biopolymers and Their Potential Biomedical Applications. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2022, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, J.; Barse, B.; Fais, A.; Delogu, G.L.; Kumar, A. Biopolymer: A Sustainable Material for Food and Medical Applications. Polymers 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sun, E.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, T.; Meng, S.; Ma, Z.; Shoaib, M.; Ur Rehman, H.; Cao, X.; Wang, N. Biopolymer Materials in Triboelectric Nanogenerators: A Review. Polymers 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, P.P.; Roy, R.; Pandit, P.; Chandrakar, K.; Maity, S. Marine biopolymers in textile applications. Marine Biopolymers: Processing, Functionality and Applications 2024, 805–832. [Google Scholar]

- Getahun, M.J.; Kassie, B.B.; Alemu, T.S. Recent advances in biopolymer synthesis, properties, & commercial applications: a review. Process Biochemistry 2024, 261–287. [Google Scholar]

- Amenorfe, L.P.; Agorku, E.S.; Sarpong, F.; Voegborlo, R.B. Innovative exploration of additive incorporated biopolymer-based composites. Scientific African 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobi, R.; Ravichandiran, P.; Babu, R.S.; Yoo, D.-J. Biopolymer and synthetic polymer-based nanocomposites in wound dressing applications: A review. Polymers 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patti, A.; Acierno, D. Towards the Sustainability of the Plastic Industry through Biopolymers: Properties and Potential Applications to the Textiles World. Polymers 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, L.M.; Smith, A.M. Hydrocolloids and Medicinal Chemistry Applications. Modern Biopolymer Science: Bridging the Divide between Fundamental Treatise and Industrial Application. Modern Biopolymer Science 2009, 595–618. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran, S.; Shahzaib; Iqbal, S.; Munir, B.; Hafiz, I. Introduction to biopolymers and their potential in the textile industry. Biopolymers in the Textile Industry: Opportunities and Limitations 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul, B.A.A.; Adel, M.; Karimi, P.; Abbaszadeh, M.; Kamaludeen, A.; Meera Moydeen, A. Recent advantages of biopolymer preparation and applications in bio-industry. Industrial Applications of Marine Biopolymers 2017, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B.; Melethil, K. Biopolymers: State of the Art and New Challenges. In Handbook of Biopolymers; 2023; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Umesh, M.; Shanmugam, S.; Kikas, T.; Lan Chi, N.T.; Pugazhendhi, A. Progress in bio-based biodegradable polymer as the effective replacement for the engineering applicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirpan, A.; Ainani, A.F.; Djalal, M. A Review on Biopolymer-Based Biodegradable Film for Food Packaging: Trends over the Last Decade and Future Research. Polymers 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, S.; Akyuz, S.; Ozel, A.E. The importance of polymers in medicine and their FTIR and Raman spectroscopic investigations. In Development, Properties, and Industrial Applications of 3D Printed Polymer Composites; 2023; pp. 170–187. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, V.; Brandalise, R.N.; Savaris, M. Polymeric Biomaterials. Topics in Mining, Metallurgy and Materials Engineering; 2017; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mikitaev, A.K.; Ligidov, M.K.; Zaikov, G.E. Polymers, Polymer Blends, Polymer Composites and Filled Polymers: Synthesis, Properties and Applications; 2006; pp. 1-222.

- Francis, R.; Joy, N.; Sivadas, A. Synthetic Biodegradable Polymers for Medical and Clinical Applications. Biomedical Applications of Polymeric Materials and Composites 2016, 361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Grethe, T. Biodegradable synthetic polymers in textiles – what lies beyond pla and medical applications? A review.; [Biorazgradljivi sintetični polimeri v tekstilstvu – kaj sledi pla in medicinskim načinom uporabe? Pregled.]. Tekstilec 2021, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaikov, G.E.; Jimenez, A.; Monakov, Y.B. Trends in polymer research. Trends in Polymer Research 2009, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, K. Polymer applications in drug delivery. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, V.B.; Bhatnagar, D.; Murthy, N.S. Biomedical polymers: An overview. In Biomedical Polymers; Springer Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; 2016; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstetter, F.; Assmann, J. Polymers. In Technology Guide: Principles - Applications – Trends; 2009; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- AlMaadeed, M.A.A.; Ponnamma, D.; El-Samak, A.A. Polymers to improve the world and lifestyle: physical, mechanical, and chemical needs. Polymer Science and Innovative Applications: Materials, Techniques, and Future Developments 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Sudhakara, P.; Omran, A.A.B.; Singh, J.; Ilyas, R.A. Recent trends and developments in conducting polymer nanocomposites for multifunctional applications. Polymers 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depan, D. Biodegradable Polymeric Nanocomposites: Advances in Biomedical Applications; 2015; pp. 1–252. [Google Scholar]

- Thadepalli, S. Review of multifarious applications of polymers in medical and health care textiles. Materials Today: Proceedings.

- Nogueira, G.F.; de Oliveira, R.A.; Velasco, J.I.; Fakhouri, F.M. Methods of incorporating plant-derived bioactive compounds into films made with agro-based polymers for application as food packaging: A brief review. Polymers 2020, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moohan, J.; Stewart, S.A.; Espinosa, E.; Rosal, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Larrañeta, E.; Donnelly, R.F.; Domínguez-Robles, J. Cellulose nanofibers and other biopolymers for biomedical applications. A review. Applied Sciences 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rana, N.; Kumar, M.; Sharma, A.; Katoch, P.; Rana, A.; Thakur, S.S. Biopolymer modifications using ionic liquids for industrial and environmental applications. In Modified Biopolymers: Challenges and Opportunities; 2017; pp. 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.R.; Bin Bakri, M.K.; Huda, D.; Othman, A.-K.; Kuok, K.K.; Uddin, J. Activated montmorillonite nanocarbon from aspen wood sawdust and its biocomposites. Advanced Nanocarbon Polymer Biocomposites: Sustainability Towards Zero Biowaste 2024, 551–624. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, D.K.; Phanisree, M.H.M.; Penchalaraju, M.; Babu, A.S. Edible and Biodegradable Polymeric Materials for Food Packaging or Coatings. Food Coatings and Preservation Technologies 2024, 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Nezafat, Z.; Shafiei, N.; Soleimani, F. Biodegradability properties of biopolymers. In Biopolymer-Based Metal Nanoparticle Chemistry for Sustainable Applications: Volume 1: Classification, Properties and Synthesis; 2021; pp. 231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Mistretta, M.C.; Botta, L.; Morreale, M.; Rifici, S.; Ceraulo, M.; La Mantia, F.P. Injection molding and mechanical properties of bio-based polymer nanocomposites. Materials 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, M.G.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.V.; Dar, A.H.; Kamble, M.G.; Pandey, S. Plant-Based Biopolymers in Food Industry: Sources, Extraction Methods, and Applications. Biopolymers in Pharmaceutical and Food Applications 2024, 1, 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Martau, G.A.; Mihai, M.; Vodnar, D.C. The use of chitosan, alginate, and pectin in the biomedical and food sector-biocompatibility, bioadhesiveness, and biodegradability. Polymers 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragitha, V.M.; Edison, L.K. Safety Issues, Environmental Impacts, and Health Effects of Biopolymers. In Handbook of Biopolymers; 2023; pp. 1469–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Gao, R.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Q. Applications of biodegradable materials in food packaging: A review. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, A.; Vanli, A.S. Production Performance of Wood Flour Reinforced Polymer Composites in Extrusion Process. International Advances in Applied Physics and Materials Science 2018, 134, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sarul, T.I.; Akdogan, A.; Koyun, A. Alternative Production Methods for Lignocellulosic Composite Materials. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2010, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.S.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Fernandes, E.M.; Reis, R.L. Fundamentals on biopolymers and global demand. Biopolymer Membranes and Films: Health, Food, Environment, and Energy Applications 2020, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Boopathi, S. Sustainable biopolymers: Applications and case studies in pharmaceuticals, medical, and food industries. Artificial Intelligence and Metaverse through Data Engineering 2024, 109–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Rathour, R.; Singh, R.; Sun, Y.; Pandey, A.; Gnansounou, E.; Andrew Lin, K.-Y.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Thakur, I.S. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates: Opportunities, challenges, and prospects. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedar, M.; Intisar, A.; Hussain, T.; Hussain, N.; Bilal, M. Challenges and Issues in Biopolymer Applications. In Handbook of Biopolymers; 2023; pp. 1497–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivuni, K.K.; Saha, P.; Adhikari, J.; Deshmukh, K.; Ahamed, M.B.; Cabibihan, J.-J. Recent advances in mechanical properties of biopolymer composites: a review. Polymer Composites 2020, 32–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Rashid, M.I.; Rehan, M.; Shah Eqani, S.A.M.A.; Summan, A.S.A.; Ismail, I.M.I.; Koller, M.; Ali, A.M.; Shahzad, K. Environmental evaluation of polyhydroxyalkanoates from animal slaughtering waste using Material Input Per Service Unit. New Biotechnology 2023, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

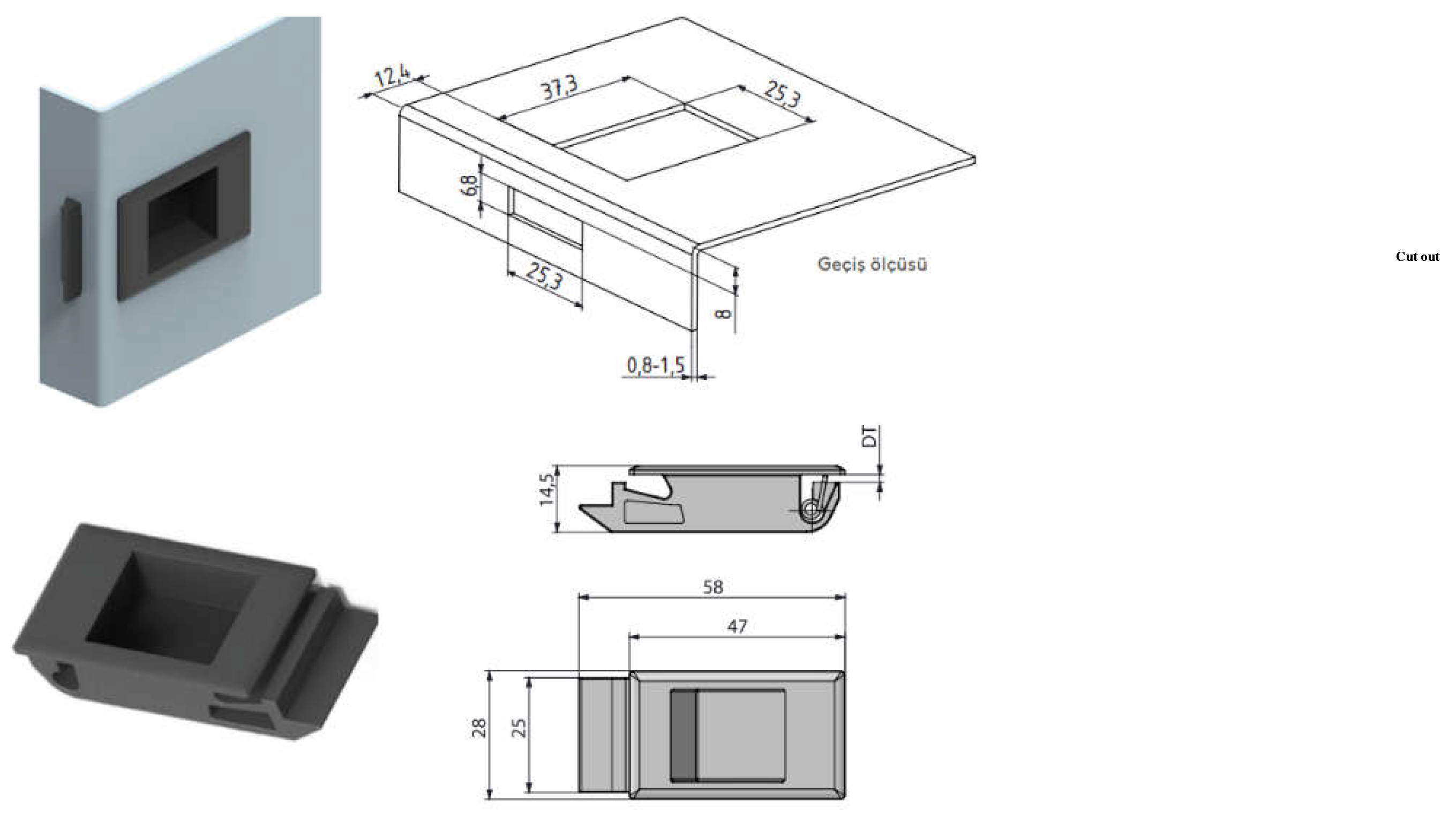

- Mesan Locks Catalogue. 2022. Available online: https://www.mesanlocks.com/en/urun/sliding-lock-1236.

| Properties | LDPE | HDPE | Polyamide (Nylon) | ABS | PLA | PHA | Starch-Based PLA | Corn Starch-Modified PP | Olive Seed-Modified ABS | Chitosan-based Polymer | Alginate-based Polymer |

| Density (g/cm³) | 0.91 - 0.94 | 0.94 - 0.97 | 1.14 | 1.04 - 1.07 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.20 | 1.30 | 1.08 | 1.30 | 1.35 |

| Melting Point (°C) | 105 - 115 | 120 - 130 | 190 - 350 | 190 - 230 | 160 - 170 | 150 - 175 | 160 | 175 | 200 | 180 | 170 |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 8 - 12 | 20 - 35 | 45 - 80 | 40 - 50 | 50 - 70 | 20 - 40 | 55 | 45 | 40 | 60 | 35 |

| Elasticity Modulus (GPa) | 0.2 - 0.5 | 0.8 - 1.5 | 2.0 - 3.0 | 1.5 - 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Impact Resistance (kJ/m²) | 5 - 7 | 20 - 30 | 30 - 50 | 10 - 15 | 10 | 5 - 10 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 15 | 10 |

| Biodegradability | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Raw Material | Petroleum-based | Petroleum-based | Petroleum-based | Petroleum-based | Corn Starch | Sugarcane | Corn Starch | Corn Starch | Olive Seed | Shellfish | Algae |

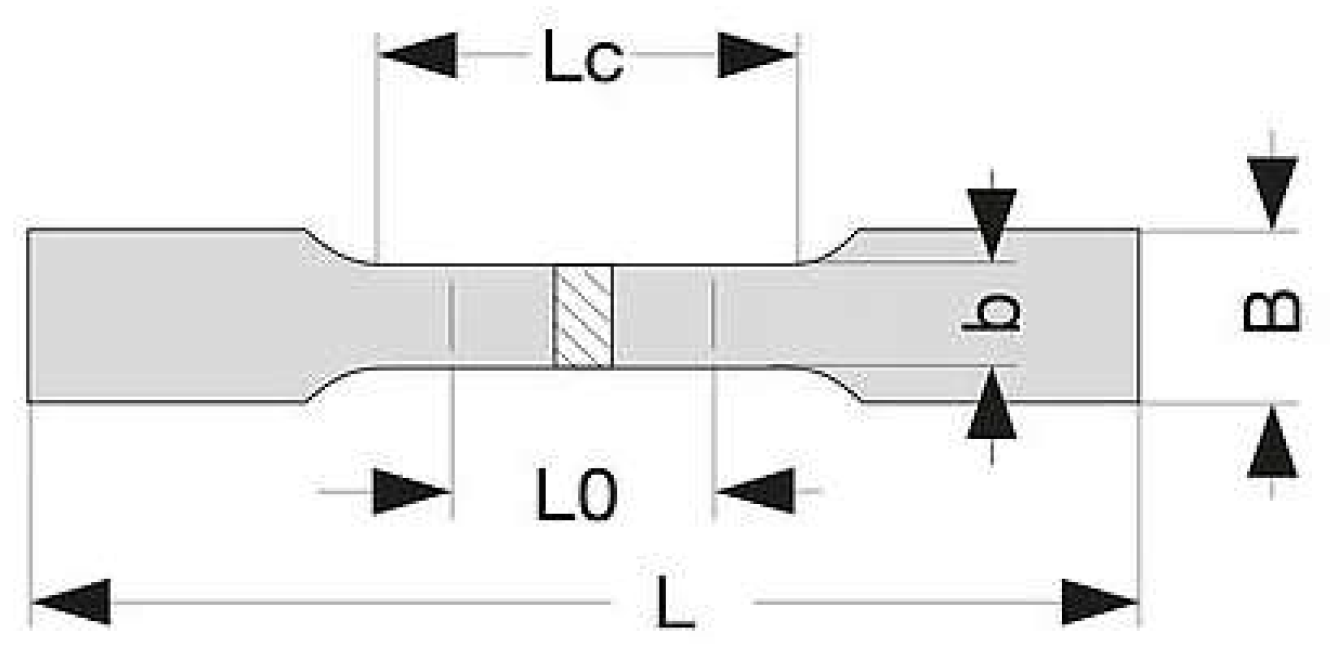

| b | L0 | B | Lc | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12,5 | 50 | 20 | 60 | 200 |

| Recipes | Tensile Force (N) | Elongation (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Eplon+ (%100) | 5.661 | 7,453 |

| Eplon+ (%70) / Recycled (%30) | 5.716 | 7,451 |

| Polyamide 6 GFR30 (%100) (A Supplier) | 6.403 | 8,011 |

| Polyamide 6 GFR30 (%100) (B Supplier) | 6.214 | 7,858 |

| Trials | Temperature - Celcius | Bar | Raw Material | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 1. Zone | 2. Zone | 3. Zone | Nozzle | Pressure | Status |

| 1. Trial | 210 | 200 | 195 | 35 | 70 | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS |

| 2. Trial | 220 | 215 | 210 | 40 | 80 | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS |

| 3. Trial | 195 | 190 | 185 | 35 | 70 | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS |

| 4. Trial | 220 | 215 | 210 | 40 | 100 | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS |

| 5. Trial | 220 | 215 | 210 | 40 | 70 | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS |

| 6. Trial | 220 | 215 | 210 | 40 | 80 | Standard ABS |

| Trial | Raw | Tensile Force (N) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Material | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Average |

| 1. | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS | 265 | 254 | 262 | 309 | 272 | 266 | 302 | 309 | 233 | 251 | 272.3 |

| 2. | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS | 267 | 262 | 246 | 272 | 231 | 286 | 256 | 248 | 243 | 222 | 253.3 |

| 3. | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS | 265 | 275 | 259 | 246 | 253 | 238 | 260 | 244 | 258 | 248 | 254.6 |

| 4. | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS | 255 | 244 | 256 | 257 | 249 | 223 | 250 | 259 | 247 | 244 | 248.4 |

| 5. | %10 Olive seed-filled ABS | 253 | 284 | 295 | 269 | 256 | 276 | 260 | 276 | 257 | 244 | 267.0 |

| 6. | Standard ABS | 278 | 273 | 275 | 303 | 269 | 303 | 302 | 242 | 253 | 317 | 281.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).